Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the vulnerability of tourism workers, but no detailed job loss figures are available that links tourism vulnerability with income inequality. This study evaluates how reduced international tourism consumption affects tourism employment and their income loss potential for 132 countries. This analysis shows that higher proportions of female (9.6%) and youth (10.1%) experienced unemployment whilst they were paid significantly less because they worked in tourism (−5%) and if they were women (−23%). Variations in policy support and pre-existing economic condition further created significant disparities on lost-income subsidies across countries. With the unequal financial burden across groups, income and regions, the collapse of international travel exacerbates short-term income inequality within and between countries.

Keywords: COVID-19, Tourism workers, Employment vulnerability, Inequality, Women, Youth

1. Introduction

“Just as the tourism sector is affected more than others by the current COVID-19 pandemic, vulnerable groups within the sector are among the hardest hit.”

United Nations World Tourism Organization (2020)

Throughout the global economy, travel and tourism were among the most-affected sectors in the COVID-pandemic (Lenzen et al., 2020). Even two years after its first outbreak in March 2020, new virus variants and several waves of infection outbreaks have led to a slow progress in border re-openings and low consumer confidence in travel. In 2020 and 2021, international tourism flow was reduced by 74% and 72% respectively, resulting in a staggering loss of US$3.8–4.7 trillion export revenue per year (UNWTO, 2022; WTTC, 2020). The impact on the tourism sector is unprecedented as the economic losses are eight times larger than the impact during the 2008 financial crisis (UNWTO, 2020b).

On top of this substantial economic loss in the tourism industry, COVID-19 generates a profound impact on our society, namely the exacerbation of poverty and inequality within and between countries. Before the pandemic, tourism development was leveraged to create substantial benefits for the macro-level economy, including increasing foreign receipts, boosting service exports, and playing a significant role in the tourism-led growth of the domestic economy (Brida, Cortes-Jimenez, & Pulina, 2016). Most importantly, tourism is labour intensive, hence provides many jobs for skilled and unskilled labour as well as for other cohorts who have difficulty in finding employment. Among these 330 million positions that are linked to tourism directly and indirectly, 54% are offered to women (UNWTO, 2019), 10–34% are available to youth (WTTC, 2019), and many are undertaken by low-income families. By supporting these economically vulnerable groups with fair wages and decent jobs, tourism plays a significant role in reducing income inequality and absolute poverty ($1.90 a day), especially for developing and less developed countries (Li, Chen, Li, & Goh, 2016; Llorca-Rodríguez, García-Fernández, & Casas-Jurado, 2020; Medina-Muñoz, Medina-Muñoz, & Gutiérrez-Pérez, 2015; Nguyen, Schinckus, Su, & Chong, 2020). With the collapse of tourism demand during the COVID-19 period, the traditional opportunities provided to economically vulnerable groups are substantially diminishing. This likely leads to a vicious cycle of economic despair, inequality, and social unrest, as evidenced in the aftereffects experienced in SARS 2003, H1N1 2009, MERS 2012, Ebola 2014, and Zika 2016 (Sedik & Xu, 2020).

Prior work on tourism-related employment losses due to COVID-19 always reported an aggregated figure. In 2020, the World Travel and Tourism Council (2020) foresaw 174.4 million job losses among tourism sectors, their suppliers, and employee-supported economic transactions at the global level. Further, the OECD (2020) estimated that 6.6–11.7 million tourism workers are at risk in the European region. For individual countries, a reduction in tourism led to 3.3%–3.6% job losses in Australia (Pham, Dwyer, Su, & Ngo, 2021), 1.7–2.7 million jobless in Japan (Kitamura, Karkour, Ichisugi, & Itsubo, 2020) and 2.1%–6.4% losses of employment in Greece (Mariolis, Rodousakis, & Soklis, 2020), or 24% reduction of tourism jobs in Tanzania (Henseler, Maisonnave, & Maskaeva, 2022). All international agencies, including the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC), and the International Labour Organization (ILO) however have indicated that this pandemic has generated asymmetrical influences on the working population with women, youth, and the low-income group being mostly affected. Yet, no detailed job losses figures are available to profile the extent of impacts on those vulnerable groups in this unprecedented tourism crisis, which is unfolding at a global scale with a prolonged period of more than two years. The need to have a robust, comparable and detailed job risk assessment is crucial as this information advises the economic vulnerability of the various groups, regions, and sectors, and most importantly, it informs the likely income and social inequality within and between countries.

The aim of this study is to provide a comprehensive job risk assessment for tourism-related employment during the COVID-19 pandemic at the global scale and provide evidence to link international tourism and income inequality during the pandemic. Our study firstly identifies how reduced international tourism consumption affects tourism employment by gender, age and income status in 132 countries and regions. Secondly, we adopt employment vulnerability to estimate tourism income loss potential against both a country's economic status and the extent of their policy and social support. Tourism workers are expected to face high employment vulnerability if their countries already experience (1) a higher unemployment rate and income inequality and (2) weak subsidiary policies and social support. These factors are directly associated with the difficulty of finding a new position and present a significant risk of reduced incomes and increased demand for social welfare. Combining the information of tourism jobs losses, the local economic situation, and region-specific COVID policy support, we then identify the most marginalized and vulnerable communities that have been heavily impacted by the tourism decline during the pandemic. Results confirm the economic polarization within and between countries and provide us with an important foundation to formulate how international tourism may drive inequality during the pandemic. This also informs how an effective tourism recovery can better foster a socially inclusive status in the post-COVID pandemic period.

2. Employment vulnerability in the COVID-19 period

The COVID-19 pandemic has created the worst recession since the Great Depression (United Nations, 2021). Each affected job in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic represents a vulnerable worker who is subject to a deterioration of their working status either via unemployment, reduction of working hours, reduction of wages, or unpaid leave. The financial burden, however, is not equally felt across society. In this study, we used employment vulnerability, defined as “how hard it is for individuals to manage the risks or cope with the losses and costs associated with the occurrence of risky events or situations” (Bocquier, Nordman, & Vescovo, 2010, p. 1297) to proxy financial burden. In the face of any crisis, employment vulnerability is determined by unemployment and wage loss potential as well as an employee's ease of re-employment (Bazillier, Boboc, & Calavrezo, 2016). For the COVID-19 event, employment vulnerability is deemed high if a worker is subject to a higher likelihood of job loss, not able to find a new position once unemployed, or has limited access to wage subsidies and any form of income support.

Among the cohort of tourism workers, women, youth and low-income workers are more likely to endure high employment vulnerability when tourism is in a crisis. This also holds true for the COVID-19 pandemic as these groups tend to be subject to more economic hardships, with higher unemployment rates and higher income losses (Arbulú, Razumova, Rey-Maquieira, & Sastre, 2021; ILO, 2020, ILO, 2021a; Sun, Sie, Faturay, Auwalin, & Wang, 2021). Three fundamental characteristics can be used to describe their vulnerability to high-risk job contexts: exposure, risk, and coping capacity (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Factors that determine tourism employment vulnerability in COVID.

The exposure factor refers to the essential job requirement in tourism to provide face-to-face contact with customers. Front-line tourism employees, who tend to comprise a higher ratio of women and youth, face both job and health risks. Their services cannot be remotely offered via telework, while at the same time, they are being exposed to higher health risks due to direct people contacts (Belzunegui-Eraso & Erro-Garcés, 2020). In the United Kingdom, people working in leisure sectors were found to have 2 to 3 times higher rates of COVID-related death than those of the same age in the population (Office for National Statistics, 2020). Without proper protection and health measures, people in frontline tourism positions are not only more prone to COVID infections and related deaths, but they also bear higher lost income and medical expenses during hospitalization and quarantine.

The second factor contributing to tourism employment vulnerability is job insecurity (see ‘RISK’, Fig. 1). Women and youth are employed in more tourism jobs that feature low wages, a lack of formal contracts, micro and small businesses, and self-employment or entrepreneurship (Kartseva & Kuznetsova, 2020). Globally, approximately 30% of the tourism workforce is hired by businesses with 2–9 employees (ILO, 2020). When tourism demand is low, a lack of legal protection and support from labour unions renders them more likely to be laid off, compared to the same cohort working in other sectors. Unstable remuneration combined with no written working contract, which is frequently seen among many causal tourism positions, especially reflects a worker's job insecurity. This is also the leading cause of poverty (World Bank, 2001).

Whilst many female and youth tourism employees are more likely to experience layoffs, their coping capacities to locate a new position are relatively low in the pandemic. Due to COVID-related restrictions and social distancing, workers who are able to engage with telework are less economically impacted (Belzunegui-Eraso & Erro-Garcés, 2020). However, to work comfortably with technology requires workers having access to hardware and software resources which may necessitate self-finance in those situations where employers do not provide the required resources. These opportunities of working from home are disproportionally enjoyed by male, older, highly educated, and highly paid employees (Blundell, Dias, Joyce, & Xu, 2020; Bonacini, Gallo, & Scicchitano, 2020). This directly relates to the inequalities present in our society with respect to access to education and training on technology. The low-education, low-skilled nature of most tourism jobs makes it more difficult to locate new “teleworkable” positions, and therefore workers in these situations become more economically vulnerable (Shibata, 2020).

Besides demographic and position-related factors, employment vulnerability of individuals is simultaneously influenced by local economic structures and policy support with respect to the COVID-19 pandemic (see ‘COPING’, Fig. 1). Destinations that rely substantially on tourism receipts, have a simplified economic structure and face a higher unemployment rate are likely to expose tourism workers to a higher economic vulnerability (Navarro-Drazich & Lorenzo, 2021; OECD, 2020). The fact that most tourism workers possess similar and basic skill sets makes intra-group job searching competitive, especially when there is only a limited number of new positions available. The competition will be fierce if the local population is confronted with an existing high unemployment rate and a substantial income inequality.

While the economic outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic is detrimental, policy support helps to buffer economic hardships and accelerate the bounce-back effect. Lessons from prior pandemics [1968 Flu, SARS (2003), H1N1 (2009), MERS (2012), Ebola (2014), and Zika (2016)] showed that reductions in GDP and employment were less severe for countries with larger first-year responses in government spending (Ma, Rogers, & Zhou, 2020). Social protection programs such as income transfer, improving food security, and supporting employability, provide a short-term compensation for the loss of labour and non-labour income; wage subsidies, tax exemptions, or active labour market programmes also help firms and workers to keep jobs. In the longer term, the instrument of equalizing income distribution serves to cultivate human capital formation, in which governments invest in education programs to enhance and diversify the skill sets of the workforce. While many countries widely implement these policy supports, the larger governments are found to be more effective in facilitating the disaster recovery due to their existing social safety nets, generous cash subsidies, and extensive work-related training opportunities (Das, Bisai, & Ghosh, 2021; Jurzyk et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2020).

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately 100 countries have provided some form of subsidies to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and self-employed workers in the tourism sector (UNWTO, 2020a). Measures that are directly related to tourism jobs and skills are widely available in Europe (80% of total countries in this region), followed by Asia and the Pacific (60%), Middle East (57%), Africa (51%) and the Americas (28%). This indicates some level of disparity in tourism policy support across regions. As history has shown, the weak institutions among many small and developing countries tend to offer minimum income compensation for tourism workers, and are more likely to render them more economically disadvantaged during the crisis than those from the richer countries.

Tourism employment vulnerability is likely to vary by gender, age, earnings, and region, but the detailed job impacts of the pandemic are yet to be quantified. In this study, we provide global evidence of the extent of job losses and employment vulnerability across countries. We dissect the social impacts of an unprecedented tourism crisis, allowing us to understand who are most economically vulnerable, which sectors endure most job losses, and which countries experience the most unequal economic losses among tourism workers. This is vital information for understanding the complex relationship of how the COVID-pandemic has influenced tourism and income inequality.

3. Method

Tourism is not a standard sector based on an industry classification system, but rather, encompasses a diversified array of businesses. As a result, tourism employment not only refers to a proportion of employees in the hospitality sector, but it also comprises those who are in the transport, retail and recreational activities that provide a direct service to tourists. Analysing the COVID-19 impact on tourism employment requires a systematic approach that links an economy's labour profile with tourism consumption. In this study, we use three steps to map tourism expenditure reductions to the labour markets, disaggregated by sector, gender, age and income level. These procedures are consistent with the Tourism Satellite Account framework that links tourism demand and tourism supply in the economy (United Nations, 2010). Essentially, these steps estimate the ratio of tourism receipt losses to the sectoral sales and assume that a direct proportion of employees in these sectors may face unemployment as the immediate consequence of a significant and rapidly reduced demand.

The first step is to estimate how the individual sector was impacted by the collapse of international travel in 2020. Total reduced international tourism receipts in 2020 were obtained from the UNWTO (2022), providing an aggregate magnitude of how the local economy was affected by international travel regulations. This aggregated tourism loss was then allocated to four characteristic tourism sectors: transport, lodging and restaurant, retailing, and recreational service. The allocation was based on the ratios that were reported in the country's tourism satellite account or the expenditure pattern that was reported to the UNWTO for 132 countries (Lenzen et al., 2018). 1

Both tourists and non-tourists contribute to sales in these four tourism-related sectors. It is likely that businesses supported mainly by tourists will be subject to a higher operating difficulty and introduce more lay-offs. However, no information is available to systematically measure how rapidly and to what extent businesses reduce their staff when demand drops. Prior studies indicated that the employment elasticity with respect to visitor expenditure varied and can range from elastic (1.53) (Thapa-Parajuli & Paudel, 2018) to inelastic (0.103)(Sun & Wong, 2010). Here, we assume that the proportion of unemployed workforce is equal to the level of the business sales losses (elasticity = 1). For example, if the international tourism collapse results in 15% sales losses for the transport sector in country A, 15% of the total workers in transport of country A are then assumed to face lay-offs and suffer income losses. The sales loss ratio (R i) is the comparison between tourism lost receipts (TL i) in 2020 and the sectoral sales (S i) in 2019. 2

We calculate the sales loss ratio for each of the four tourism dependent sectors (United Nations, 2010): transport, lodging and restaurant, retailing, and recreational services, and then estimate their respective unemployed staff to derive the total job losses due to international tourism (Eq. (1)).

| (1) |

where Q tourism represents total tourism worker reduction; Qi is the total number of workers in sectors i = 1, …, 4 (transport, lodging and restaurant, retailing and recreational service); R i refers to the sales loss ratio due to the reduction of international travel for four sectors; TL i stands for tourism receipt losses in 2020, and S i represents the total sales of the sector in 2019.

The last step maps the employment reduction of tourism workers by demographic variables based on the International Labor Organization labour profiles. The International Labor Organization (2021b) provides the most comprehensive and complete labour data for all persons in paid employment or self-employment based on a consistent industry classification system. This helps to systematically track the workforce across four tourism dependent sectors without narrowly focusing only on hospitality. The International Labour Organization provides labour data by gender, age, and the monthly salary, allowing us to calculate the female workers' participation rate, the youth worker (age 15–24) participation rate, the sectoral pay difference between tourism and non-tourism workers, and the gender pay gap in tourism.

A harsh job market and substantial income polarization present additional challenges for the jobless to locate new positions. To reflect these economic conditions, the unemployment rate in 2020 (ILO, 2021b) and the income inequality Gini index (World Bank, 2021) were sourced. In terms of resilience, policy can mitigate employment vulnerability via income support measures. Income support data from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) is adopted to proxy the level of financial support to the affected tourism worker (Hale et al., 2021). The system records the number of days and the extent that the income-support support is provided to people who lose their jobs or cannot work. This gives an indication on how extensive and supportive the subsidies are to the unemployed. The UNDP Human Development Index (HDI) provides information of the local education system and the number of years of schooling (UNDP, 2020). This is used to proxy people's coping capacities to be re-trained and re-hired in a new position.

4. Results

4.1. Global tourism job losses

Total inbound tourism loss across 132 countries was US$ 1.58 trillion in 2020 (UNWTO, 2022), corresponding to 1.38% of global production losses. Our estimation indicates this loss places 24 million direct tourism jobs at risk. The sectoral breakdown indicates that 9.5 million position losses (40%) are in the retailing and wholesale trade, followed by 8.8 million employment losses (37%) in accommodation and restaurants, 4.5 million (19%) in transport, and 1.1 million (5%) in personal services.

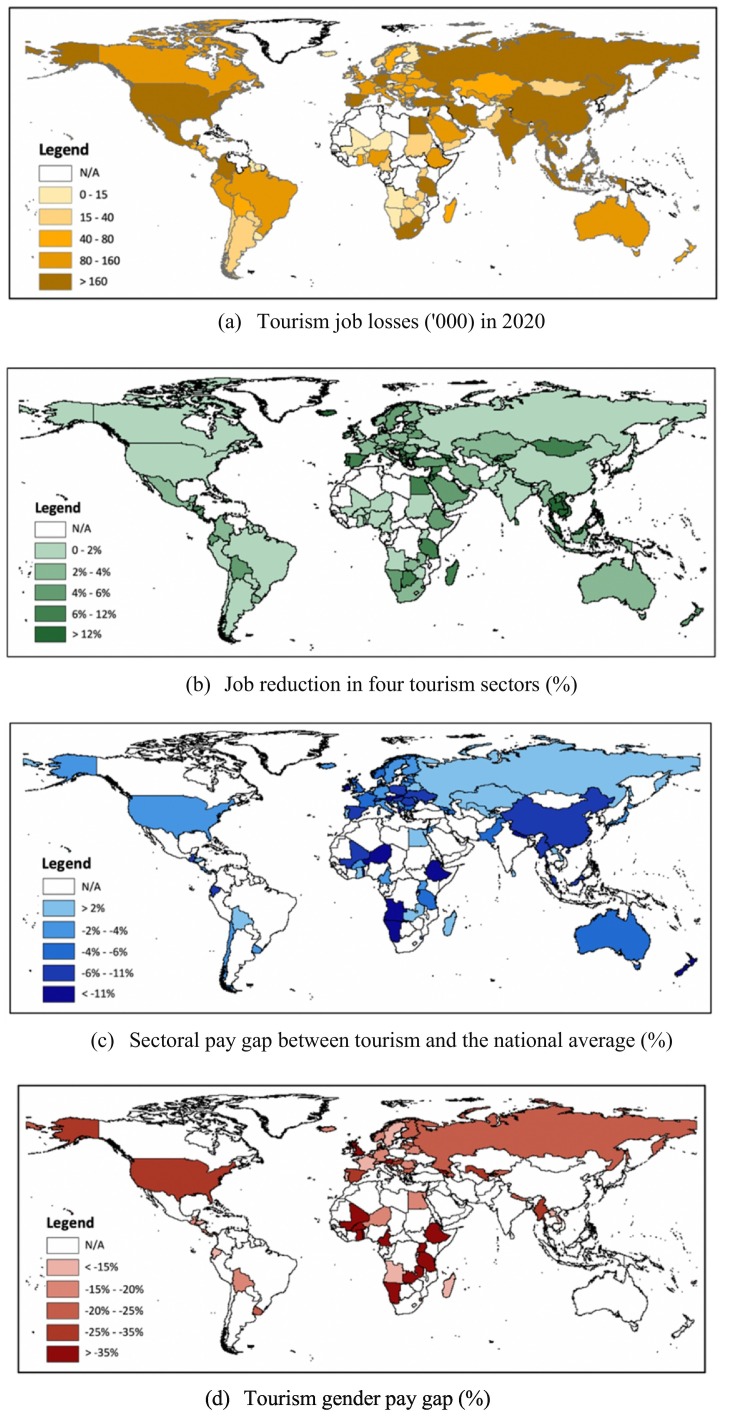

In terms of destination ranking, China bears the highest employment loss potential (4.5 million FTE), followed by Thailand (2.3 million), Indonesia (1.7 million), Vietnam (1.2 million) and India (1.0 million) (part a in Fig. 2 and Table 1 ). Jobs losses at the individual country level reflect not only total tourism revenue that was forgone during the pandemic but also the inherent differences in labour intensity across countries. Due to different uptakes of technology and labour cost, the labour intensity per unit service varies. Indonesia and Vietnam, for example, support four times more workers per million US dollar sales than those in China, in the hospitality sector. The labour-intensive nature of specific countries and the significant size of their inbound tourism market expose a larger number of tourism workers to economic risks.

Fig. 2.

Tourism employment losses, job losses ratio, sectoral pay gap and gender pay gap.

Table 1.

Countries that were mostly impacted by the inbound tourism losses and their job characteristics, 2020

| Tourism job losses (000) | Female unemployed rate across four tourism sectors | Youth unemployment rate across four tourism sectors | Pay difference between tourism and the national average1 | Pay difference between male and female tourism workers2 | Pay difference between female tourism workers and female non-tourism workers3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 4487 | Maldives | 87% | Maldives | 84% | Haiti | −42% | Ghana | −69% | Uganda | −70% |

| Thailand | 2299 | Montenegro | 41% | Croatia | 46% | Angola | −30% | Mali | −60% | Togo | −63% |

| Indonesia | 1703 | Cambodia | 41% | Montenegro | 43% | Togo | −30% | Togo | −58% | Namibia | −49% |

| Viet Nam | 1232 | Croatia | 39% | Vanuatu | 41% | Austria | −23% | Uganda | −50% | Angola | −39% |

| India | 1016 | Fiji | 38% | Fiji | 40% | Ireland | −18% | Cameroon | −50% | Comoros | −25% |

| Philippines | 869 | Georgia | 37% | Cambodia | 38% | Albania | −18% | Vanuatu | −50% | Nepal | −25% |

| Cambodia | 756 | Vanuatu | 36% | Georgia | 37% | Namibia | −18% | Ethiopia | −44% | Mali | −24% |

| Malaysia | 705 | Cyprus | 34% | Cyprus | 36% | Jamaica | −16% | Burkina Faso | −42% | Austria | −24% |

| United States | 665 | Gambia | 32% | Iceland | 29% | Nepal | −15% | Tanzania | −41% | Ethiopia | −22% |

| Egypt | 582 | Belize | 31% | Albania | 28% | Slovakia | −14% | Namibia | −41% | Rwanda | −20% |

| Average across the sample | 10% | 10% | −5% | −23% | −12% | ||||||

Note. 1The negative value indicates that the average salary across four tourism sectors is lower than the national average salary. 2The negative value indicates that the average salary of female tourism workers is lower than that of the male tourism workers. 3The negative value indicates that the average salary of female tourism workers is lower than that of the female non-tourism workers.

In contrast, the highest job reduction ratio is found among small island and developing countries with a relatively simplified economy and that rely heavily on international tourism. The tourism job loss ratio of these tourism-related sectors goes as high as 86% for Maldives, 43% for Montenegro, and 37% for Fiji, Cambodia and Croatia, (part B in Fig. 2 and Table 1). In other words, one in every three tourism workers are likely to be laid off in these hotspots.

Referencing countries with a detailed job profile allows the employment losses to be further assessed by gender, age and monthly salary (n = 105). Considering international travel losses, 9.6% of total female workers were likely to be unemployed in four tourism sectors 3; in contrast, the job reduction rate for male workers was 8.9%. Job reduction was also higher for youth (age 15–24) (10.1%) while their counterpart cohorts, young adults (age 25–30) and adults (age 30+), experienced 9.6% and 9.3% job losses, respectively. 4

The composition of tourism workers before COVID provides a good basis for predicting the likely job losses pattern. Both developed and developing countries have a high female participation rate and youth participation rate in tourism. In particular, sixteen countries have a female employment ratio in tourism at least 10% higher than the economy-wide average (Togo 76%, Latvia 65%, Ghana 63%, Bolivia 62%, and Estonia 58%), demonstrating strong female-supported tourism businesses. Similarly, the dominance of youth employment before COVID is prevailing in some of the richest and poorest destinations in the world, such as the Netherlands (38% of the workforce across four tourism-related sectors), Denmark (34%), and Vanuatu (32%), Angola (31%) and Ethiopia (30%). This supports the notion that both developed and developing countries are all likely to lose significant female and youth tourism jobs in the COVID pandemic. 5

On top of the financial burden on women and youth workers, people in the tourism sectors tend to work at the lower end of the pay scale. Across 90 destinations, 69 countries (77%) offer a lower pay, having a 9% difference in tourism salary compared to the national average. The biggest wage difference between tourism and non-tourism workers is reported in Haiti (−42%), Angola (−30%), Togo (−30%), Austria (−23%) and Ireland (−18%) (part c in Fig. 2). For the other 21 countries, there is a silver lining, as tourism's salary is 7% higher than the economy's average (Lao 32%; Ghana 22%; Egypt 21%, Kyrgyzstan 10% and Madagascar 9%). However, the low pay issue persists. Globally tourism workers are paid 5% below the national average salary.

A significant gender pay inequality among global tourism workers further exacerbates the job precarity. Female tourism workers on average earned 23% less than their male tourism colleagues, and 11% lower than other female employees in non-tourism sectors (part d in Fig. 2 and Table 1). In contrast, tourism sectors were able to offer male workers a similar salary (1% less) to those employed by other sectors. Some of the largest tourism gender pay gaps are observed in the poorest regions, such as Ghana (men earned 69% more than women), Togo (60%), Mali (58%), and developed countries, including United Kingdom (39%) and Austria (38%). Clearly, the economic status of a country does not determine or correlate with the tourism gender pay gap (p-value of the Pearson correlation = 0.796). This differs from the global pattern in which middle-income countries tend to have the smallest gender pay gap when all sectors are considered (Olivetti & Petrongolo, 2008). It is important to acknowledge that the gender pay gap can be a result of multiple factors, including differences between average hourly earnings of men and women, total hours worked and whether they are full-time or part-time. While the gender pay gap is an indication of inequality of economic earnings, it may not ascertain discrimination.

4.2. Inter-country vulnerability

We compare inter-country variability in the profile of tourism workers, macro-level economic performance, policy support, and tourism economic shock during the COVID pandemic across four income categories: high income, upper middle income, lower middle income and low income. As indicated earlier, destinations tend to have a similar tourism job profile with more positions offered to women and youth and pay differently by gender. Destinations however face significant disparity in tourism demand shock, pre-existing local economic conditions and COVID-related policy support by economic status (see ANOVA results in Table 2 ). These factors moderate employment vulnerability at the destination level and reveal the most vulnerable communities that have been heavily impacted by the tourism decline during the pandemic.

Table 2.

Tourism job characteristics, economic shock, and macro factors by four economic statuses, 2020.

| Income category | Tourism job characteristics |

Macro economy |

Policy support |

Economic shock |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female tourism workers (%) | Youth tourism workers (%) | Sectoral pay gap (%) | Gender pay gap (%) | Unemployment rate 2020 (%) | GINI index1 | OxCGRT Economic support index2 | The Human Development Index3 | Tourism job reduction (%) | Tourism female job reduction (%) | Tourism youth job reduction (%) | |

| High income | 44% | 16% | −7% | −18% | 6.6% | 32.0 | 1.26 | 0.87 | 8.0% | 8.4% | 9.0% |

| Upper middle income | 44% | 15% | −6% | −20% | 10.1% | 42.1 | 0.58 | 0.76 | 15.0% | 15.3% | 16.5% |

| Lower middle income | 42% | 18% | 0% | −19% | 5.8% | 39.2 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 7.6% | 7.7% | 8.2% |

| Low income | 45% | 18% | −10% | −26% | 6.3% | 37.9 | 0.36 | 0.49 | 4.2% | 5.1% | 4.6% |

| p-value of ANOVA test | 0.91 | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.76 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

Note: 1The Gini index is a measure of the distribution of income across a population. It has a range of 0 to 1 where a higher Gini index indicates greater inequality. 2 The OxCGRT tracked whether the government is providing direct cash payments to people who lose their jobs or cannot work, from May to Dec 2020. The result is recorded in three ways: 0 – no income support; 1 – government is replacing less than 50% of lost salary; 2 – government is replacing 50% or more of lost salary. The larger number indicates that stronger support is provided. 3 The Human Development Index (HDI) proxies the access to education. It has a range of 0 to 1 where 1 represents longer years of schooling.

Across four income categories, we found that destinations in the upper-middle income category suffer the largest employment shock with an average of 15% reduction in the tourism workforce (Table 2). These include some very important tourism-dependent small island economies, for example, Maldives, Montenegro, Fiji, and St Lucia. Around one in every six workers across four tourism sectors is likely to suffer job losses in 2020 due to the collapse of international travel—twice the impact at other destinations. In addition, these countries face a pre-existing high unemployment rate (10%) and experience the most unequal income distribution to household (proxied through the GINI index). These factors compound the difficulty for the existing unemployed tourism workers to make up their lost income with a good-quality new position. Even though their governments have provided income support to people who have lost work, these measures are estimated to be half of those that are available in high-income countries in terms of the amount of subsides provided and the length of time the measures last (Hale et al., 2021). These factors are likely to cause tourism workers in upper-middle-income destinations to suffer the biggest income losses compared to the same cohorts at other destinations.

For disadvantaged groups, female tourism workers in low-income countries are expected to face the biggest income loss potential. In countries such as Togo, Ethiopia and Gambia, tourism is a major job provider for many women, recording at least a 10% higher female participation rate than other sectors, but at the same time, providing a substantially lower wage due to sectoral-pay differences (−10%) and gender pay gap (−26%) (Table 2). This alludes to potential entry barriers for women to be employed in other sectors due to skill and opportunity shortage, which will likely result in difficulty for them to replace their income with a new position. It is also of no surprise that only very small social assistance is being made available. Globally, the social assistance (mainly cash transfer) ranges from $525 per capita in high income countries to $6 in low income countries with an average duration of 3.3 months during the pandemic (Gentilini, Almenfi, Orton, & Dale, 2020). The unemployment benefit replacement rates are therefore expected to be low. The combination of gender pay gap and weak policy support renders female workers in low-income countries more economically vulnerable than female workers at other destinations.

5. Discussion

Drawing from the global evidence in the previous section, we identify three major factors in causing the asymmetrical income losses across cohorts among the tourism workforce in the pandemic: tourism job characteristics, economic factors and policy support (Fig. 3 ). These factors explain how income has been redistributed within and across countries, providing a basis to predict welfare and social inequality at the macro level.

Fig. 3.

Drivers of income losses protentional among tourism workforce and income inequality.

5.1. Intra-country income inequality

The demographic composition of workers and their earnings determines the distribution of a country's income across the workforce, before and after the pandemic. Destinations that employ disproportionally more women and youth workers in their tourism businesses are expected to see more job losses during the pandemics because a higher proportion of these two cohorts work in frontlines, in part-time positions, and without the protection of formal contracts. This has been confirmed in the Pacific Small Island Developing States (Connell, 2021), Portugal (Almeida & Santos, 2020), Spain (Arbulú et al., 2021), Indonesia (Sun et al., 2021) and South Africa (Chipumuro, Mihailescu, & Rinaldi, 2021). The average salary of these cohorts further determines whether they are low-income workers and proxies if they have sufficient savings to navigate the economic hardship. Therefore, countries that report a higher proportion of female and youth workers, a lower pay rate in the tourism sector, and a significant gender pay gap are expected to experience substantial income reduction for female and youth workers in the lower earning quantile during the COVID-19 pandemic. This presents a context in which a society sees many lower-income tourism workers lose earnings while high-income non-tourism workers continue to work, earn and save. As a result, this will shift the labour earning distribution of a country toward the high-earning quantiles and shrink the share received by the low-income earners. Subsequently, this widens the income inequality within a country.

Overall, three quarters of global destinations experienced a sectoral-pay gap with tourism workers receiving less payment, and almost every country reporting a significant gender-pay gap with female tourism workers being mostly disadvantaged. Our analysis shows the distortion of income distribution through tourism is not just a challenge for the poor, small or tourism-dependent states but also for some of the most developed economies in the world, such as the Netherlands (a high ratio of youth tourism labour) and the United Kingdom (a significant tourism gender pay gap). This implies that the rapid collapse of international tourism consistently increases the short-term income inequality between men/women, youth/adult, and rich/poor for most destinations globally.

5.2. Cross-country income inequality

While tourism workers are mostly vulnerable during the pandemic, the impact of income re-distribution can be moderated by macro-level economic factors and policy support. Significant disparities in these two dimensions however are found across regions. It is of no surprise that high-income countries provide relatively sufficient policy support, and at the same time, their economy is healthier, more diversified, and well digitalized. In contrast, middle-income and low-income countries struggle with an insufficient social safety net, a higher unemployment rate or a lack of government spending on mitigating the impacts of the pandemic. The same countries have also been assailed by high disparity in income distribution. This challenge becomes more pronounced given that these regions are not supported with a strong domestic tourism demand and with a higher spending power among their residents (Phuc & Su, 2020; WTTC, 2021). The opportunity to leverage domestic tourism to substitute inbound tourism remains slim. Ultimately, an unemployed female youth tourism worker in the Netherlands will experience better welfare than an unemployed female youth tourism worker in Ethiopia during this pandemic.

If we rank all workers globally on their earnings, an uneven income distribution already existed before the pandemic. A worker from the top-earning 10% quantile, on average, received US$7475 per month, and a worker in the bottom 10% earned just US$22 in 2017 (ILO, 2019). With the collapse of international tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic, we expect that heterogeneous macro-economic factors and different levels of policy support will buffer tourism workers in high income countries, but not in the others. For example, discretionary fiscal policy from the European Commission well cushioned COVID's impacts on households, allowing income losses to be similar to those experienced in the 2008–2009 financial crisis (Almeida et al., 2021). On the contrary, households in low income countries not only face income losses, but also are challenged by food insecurity, access to medicine and staple foods, and substantial reduction of education hours (Josephson, Kilic, & Michler, 2021). As a result, tourism workers from high income countries who are likely to sit in the middle or higher end of the global income distribution curve are less affected than low-income tourism workers in poor countries. Inevitably, income losses after subsidy then result in a further difference in labour income among tourism workers across countries, and widens income inequality between destinations.

6. Conclusions

International travel is a luxury good and is income elastic (Falk & Lin, 2018; Smeral, 2010). It allows international receipts to flow from the wealthier population (tourists) to many small and medium enterprises, then to workers who receive a relatively lower salary in destination countries. Exporting tourism thus enables an extensive redistribution of income among stakeholders across countries, and this sets it apart from many natural resource exports (e.g., precious metals and oil) where the wealth tends to centre on a selected few elite (Smith, 2004). When no international tourism is allowed in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, polarized income changes are expected. On one hand, the rich get richer. The unspent international travel budget of the wealthier household becomes another influx of investment for capital goods, such as stocks or real estates. Increased opportunity for capital income earners during the pandemic is one of the key factors in driving inequality (Das et al., 2021). On the other hand, tourism vulnerable workers become poorer compared to non-tourism workers within and across countries.

Our study provides the global empirical evidence to explain this challenge by reflecting the combination of tourism's inherent job characteristics, the pay differences, the local economic structure, and the unequal policy support. Our analysis has shown that there are significant disparities in terms of economic vulnerability and job insecurity between income classes and genders. The unequal fiscal policies and inherent economic structures further create a new geographical distribution of wealth and poverty in the aftermath of crisis.

Overall, the observation of global tourism job losses speaks directly about the social challenge of inequality. Even when the borders begin to reopen, the short-term impact on the tourism industry may have long-term implications for inequalities. This circumstance manifests itself in many possible individual tourism workers' fates: professionals who have been out of their jobs for too long to secure re-employment and avoid retraining; low-skilled employees who were nevertheless a family breadwinner, plunging entire families into assistance dependence; older employees who have not been offered retraining opportunities are forced to work in illegal wildlife poaching or much lower-skilled jobs (the well-known accounts of grounded airline pilots driving taxis); and last but not least, women and young people whose skills and motivation are wasted when traditional systems give priority to less productive older men (Aditya, Goswami, Mendis, & Roopa, 2021; Almeida & Santos, 2020; Chipumuro et al., 2021; Connell, 2021).

‘Flying blind’ into a crisis such as this pandemic, in terms of information on economic vulnerability and job insecurity has meant that economic woes have inevitably followed, often exacerbated beyond the support that would have been required had one acted with foresight and precaution at the outset. Decision makers would have benefitted from having had access to such information by the time the Coronavirus pandemic started in earnest. This is because economic modelling for the tourism sector could have included age, gender and income dimensions, which is currently lacking among most assessments. Integrating a detailed employment profile into tourism's operation allows the heterogeneity of tourism employees to be analysed. Equipped with this comprehensive information, foresight and precaution could have taken the edge off the most extreme of such vulnerabilities. This is especially true for countries that are dependent on tourism income receipts, and that have few other income sources, such as small island nations.

The analysis presented in this study could also serve to inform the work of global tourism organisations and committees, such as the Global Tourism Crisis Committee (UNWTO, 2020c) convened by the UNWTO, which aims to provide recommendations for a harmonized approach to restarting tourism post-COVID-19 pandemic, and to ‘build-back-better’. The work of the committee clearly highlights the role of timely healthcare responses (e.g., administration of vaccines) for the future of tourism, the role of workers, and the importance of supporting tourism jobs and companies. As the UNWTO unites with Tourism Ministers around the world to #RestartTourism (UNWTO, 2021), there is an urgent need to consider economic vulnerabilities through better understanding the underlying tourism- inherent job characteristics, the pay difference, the local economic structure, and the unequal policy support for the rebuilding process. This study especially supports the inclusive recovery for women by highlighting hotspots where most female job losses are likely to occur. This helps to facilitate the channelling of international resources to gender-responsive policies and to develop education programs for women to upgrade their IT skills, soft skills, and networking capability. These short- and mid-term policy supports ensure women who are proportionally more affected in this pandemic will be best helped across all areas and all levels with a coordinated international assistance.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Video abstract

Biographies

Ya-Yen Sun addresses tourism sustainability, focusing on economic impacts and environmental footprinting.

Mengyu Li studies 1) using input-output-based disaster models to assess economic, environmental and social impacts of disasters; 2) low-carbon energy system modelling and sector coupling strategies.

Manfred Lenzen works on the link between environmental/resource impacts and international trade.

Arunima Malik undertakes big-data modelling to quantify sustainability impacts at local, national and global scales.

Francesco Pomponi utilities interdisciplinary approach to address societally just transitions to develop sustainably.

Editor: Li Gang

Footnotes

The UNWTO reported tourism receipt loss for 185 countries. However, the unavailability of tourism satellite accounts or the expenditure of some countries prevents the aggregated receipt loss to be allocated to four sectors.

Under the framework of Tourism Satellite Account (United Nations, 2010), tourism employment is in a direct ratio to tourism sales. This means if the sales are reduced by 10%, employment will decrease by 10%. This assumption may not reflect the way business operates (Sun & Wong, 2010); however, it provides an approximation on how the labour market is adjusted based on external demand shock.

Reducing inbound tourism was found to place more male tourism workers (14.3 million) at risk than females (6.2 million). This in part reflects that global employment is predominantly experienced by men (61%), especially in the transport sector. The associated income losses for male and female tourism workers are US $4.8 billion and US$2.8 billion, respectively.

The age breakdown on job losses also revealed that adult workers endure most of the job losses (9.2 million FTE, age 30+), followed by youth workers (2.00 million FTE, age 15–24), and young adult workers (1.73 million FTE, age 24–30).

The Pearson correlation between female participation rate in tourism and GDP per capita is insignificant (p value = 0.966). This same result is observed for the youth participation in tourism and GDP (p value = 0.114).

References

- Aditya V., Goswami R., Mendis A., Roopa R. Scale of the issue: Mapping the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on pangolin trade across India. Biological Conservation. 2021;257 doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida F., Santos J.D. The effects of COVID-19 on job security and unemployment in Portugal. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. 2020;40(9/10):995–1003. doi: 10.1108/ijssp-07-2020-0291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida V., Barrios S., Christl M., De Poli S., Tumino A., Van Der Wielen W. The impact of COVID-19 on households´ income in the EU. The Journal of Economic Inequality. 2021;19(3):413–431. doi: 10.1007/s10888-021-09485-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbulú I., Razumova M., Rey-Maquieira J., Sastre F. Measuring risks and vulnerability of tourism to the COVID-19 crisis in the context of extreme uncertainty: The case of the Balearic Islands. Tourism Management Perspectives. 2021;39 doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazillier R., Boboc C., Calavrezo O. Measuring employment vulnerability in Europe. International Labour Review. 2016;155(2):265–280. [Google Scholar]

- Belzunegui-Eraso A., Erro-Garcés A. Teleworking in the context of the Covid-19 crisis. Sustainability. 2020;12(9) doi: 10.3390/su12093662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blundell R., Dias M.C., Joyce R., Xu X. COVID-19 and inequalities. Fiscal Studies. 2020;41(2):291–319. doi: 10.1111/1475-5890.12232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocquier P., Nordman C.J., Vescovo A. Employment vulnerability and earnings in urban West Africa. World Development. 2010;38(9):1297–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonacini L., Gallo G., Scicchitano S. Working from home and income inequality: Risks of a “new normal” with COVID-19. Journal of Population Economics. 2020, Sep 12:1–58. doi: 10.1007/s00148-020-00800-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brida J.G., Cortes-Jimenez I., Pulina M. Has the tourism-led growth hypothesis been validated? A literature review. Current Issues in Tourism. 2016;19(5):394–430. [Google Scholar]

- Chipumuro J., Mihailescu R., Rinaldi A. Emerald Publishing Limited; 2021. Gender disparities in employability in the tourism sector post-COVID-19 pandemic: Case of South Africa; pp. 173–184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connell J. COVID-19 and tourism in Pacific SIDS: Lessons from Fiji, Vanuatu and Samoa? The Round Table. 2021;110(1):149–158. doi: 10.1080/00358533.2021.1875721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das P., Bisai S., Ghosh S. Impact of pandemics on income inequality: Lessons from the past. International Review of Applied Economics. 2021:1–19. doi: 10.1080/02692171.2021.1921712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Falk M., Lin X. Income elasticity of overnight stays over seven decades. Tourism Economics. 2018;24(8):1015–1028. doi: 10.1177/1354816618803781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilini U., Almenfi M., Orton I., Dale P. World Bank; 2020. Social protection and jobs responses to COVID-19: A real-time review of country measures. [Google Scholar]

- Hale T., Angrist N., Goldszmidt R., Kira B., Petherick A., Phillips T.…Tatlow H. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 government response tracker) Nature Human Behaviour. 2021;5(4):529–538. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henseler M., Maisonnave H., Maskaeva A. Economic impacts of COVID-19 on the tourism sector in Tanzania. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights. 2022;3(1) doi: 10.1016/j.annale.2022.100042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ILO . International Labour Organization; 2019. The global labour income share and distribution - key findings. [Google Scholar]

- ILO . International Labour Organization; 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on the tourism sector. [Google Scholar]

- ILO . 7th ed. International Labour Organization; 2021. COVID-19 and the world of work. [Google Scholar]

- ILO ILO data explorer. 2021. https://www.ilo.org/shinyapps/bulkexplorer13/?lang=en&segment=indicator&id=POP_XWAP_SEX_MTS_NB_A

- Josephson A., Kilic T., Michler J.D. Socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 in low-income countries. Nature Human Behaviour. 2021;5(5):557–565. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurzyk E., Nair M.M., Pouokam N., Sedik T.S., Tan A., Yakadina I. COVID-19 and inequality in Asia: Breakingt eh vicious cycle. International Monetary Found. 2020;Working Paper No. 2020/217 [Google Scholar]

- Kartseva M.A., Kuznetsova P.O. The economic consequences of the coronavirus pandemic: Which groups will suffer more in terms of loss of employment and income? Population and Economics. 2020;4(2):26–33. doi: 10.3897/popecon.4.e53194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura Y., Karkour S., Ichisugi Y., Itsubo N. Evaluation of the economic, environmental, and social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Japanese tourism industry. Sustainability. 2020;12(24) doi: 10.3390/su122410302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen M., Li M., Malik A., Pomponi F., Sun Y.Y., Wiedmann T.…Yousefzadeh M. Global socio-economic losses and environmental gains from the coronavirus pandemic. PLoS One. 2020;15(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen M., Sun Y.-Y., Faturay F., Ting Y.-P., Geschke A., Malik A. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nature Climate Change. 2018;8(6):522–528. [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Chen J.L., Li G., Goh C. Tourism and regional income inequality: Evidence from China. Annals of Tourism Research. 2016;58:81–99. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2016.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Llorca-Rodríguez C.M., García-Fernández R.M., Casas-Jurado A.C. Domestic versus inbound tourism in poverty reduction: Evidence from panel data. Current Issues in Tourism. 2020;23(2):197–216. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2018.1494701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C., Rogers J.H., Zhou S. Modern pandemics: Recession and recovery. 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3565646 Available at SSRN 3565646.

- Mariolis T., Rodousakis N., Soklis G. The COVID-19 multiplier effects of tourism on the Greek economy. Tourism Economics. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1177/1354816620946547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Muñoz D.R., Medina-Muñoz R.D., Gutiérrez-Pérez F.J. The impacts of tourism on poverty alleviation: An integrated research framework. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2015;24(2):270–298. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2015.1049611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Drazich D., Lorenzo C. Sensitivity and vulnerability of international tourism by covid crisis: South America in context. Research in Globalization. 2021;3 doi: 10.1016/j.resglo.2021.100042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen C.P., Schinckus C., Su T.D., Chong F.H.L. The influence of tourism on income inequality. Journal of Travel Research. 2020;60(7):1426–1444. doi: 10.1177/0047287520954538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- OECD . OECD; 2020. Rebuilding tourism for the future COVID-19 policy response and recovery. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics . Office for National Statistics; 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by occupation, before and during lockdown. [Google Scholar]

- Olivetti C., Petrongolo B. Unequal pay or unequal employment? A cross-country analysis of gender gaps. Journal of Labor Economics. 2008;26(4):621–654. doi: 10.1086/589458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pham T.D., Dwyer L., Su J.-J., Ngo T. COVID-19 impacts of inbound tourism on Australian economy. Annals of Tourism Research. 2021;88 doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2021.103179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phuc C.N., Su T.D. Domestic tourism spending and economic vulnerability. Annals of Tourism Research. 2020;85 doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.103063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedik T.S., Xu R. A vicious cycle how pandemics Lead to economic despair. International Monetary Fund. 2020;Working Paper No. 2020/216 [Google Scholar]

- Shibata I. International Monetary Fund; 2020. The distributional impact of recessions- the global financial crisis and the pandemic recession. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeral E. Impacts of the world recession and economic crisis on tourism: Forecasts and potential risks. Journal of Travel Research. 2010;49(1):31–38. doi: 10.1177/0047287509353192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. Oil wealth and regime survival in the developing world, 1960–1999. American Journal of Political Science. 2004;48(2):232–246. doi: 10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00067.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.-Y., Sie L., Faturay F., Auwalin I., Wang J. Who are vulnerable in a tourism crisis? A tourism employment vulnerability analysis for the COVID-19 management. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. 2021;49:304–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.-Y., Wong K.-F. An important factor in job estimation: A nonlinear jobs-to-sales ratio with respect to capacity utilization. Economic Systems Research. 2010;22(4):427–446. doi: 10.1080/09535314.2010.526595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa-Parajuli R., Paudel R.C. Tourism sector employment elasticity in Nepal. The Economic Journal of Nepal. 2018;3-4:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP . United Nations Development Programme; 2020. Human development report 2020 - the next frontier human development and the Anthropocene. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . United Nations, and World Tourism Organization; 2010. Tourism satellite account recommended methodological framework. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . United Nations; 2021. World economic situation and prospects 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . 2nd ed. World Tourism Organization; 2019. Global report on women in tourism. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . World Tourism Organization; 2020. How are countries supporting tourism recovery? [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . World Tourism Organization; 2020. International tourism down 70% as travel restrictions impact all regions. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . World Tourism Organization; 2020. UNWTO convenes global tourism crisis committee.https://www.unwto.org/unwto-convenes-global-tourism-crisis-committee Retrieved Oct 25th from. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . World Tourism Organization; 2021. The World Tourism Organization unites with tourism ministers in the americas to relaunch tourism in the region.https://www.unwto.org/unwto-convenes-global-tourism-crisis-committee Retrieved Oct 25th from. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . World Tourism Organization; 2022. International tourism and COVID-19.https://www.unwto.org/international-tourism-and-covid-19 Retrieved Jan 27, 2022 from. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . Oxford University Press; 2001. World development report 2000–2001: Attacking poverty. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . World Bank; 2021, May 30. Gini index (World Bank estimate)https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI Retrieved June 1, 2021 from. [Google Scholar]

- WTTC . World Travel and Tourism Council; 2019. Travel & Tourism- generating jobs for youth. [Google Scholar]

- WTTC . The World Travel and Tourism Council; 2020. Global economic impact from COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- WTTC Domestic tourism - Importance and economic impact. 2021. https://wttcweb.on.uat.co/en-gb/Research/Economic-Impact

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video abstract