Abstract

A naturally occurring AmpC β-lactamase (cephalosporinase) gene was cloned from the Hafnia alvei 1 clinical isolate and expressed in Escherichia coli. The deduced AmpC β-lactamase (ACC-2) had a pI of 8 and a relative molecular mass of 37 kDa and showed 50 and 47% amino acid identity with the chromosome-encoded AmpCs from Serratia marcescens and Providentia stuartii, respectively. It had 94% amino acid identity with the recently described plasmid-borne cephalosporinase ACC-1 from Klebsiella pneumoniae, suggesting the chromosomal origin of ACC-1. The hydrolysis constants (kcat and Km) showed that ACC-2 was a peculiar cephalosporinase, since it significantly hydrolyzed cefpirome. Once its gene was cloned and expressed in E. coli (pDEL-1), ACC-2 conferred resistance to ceftazidime and cefotaxime but also an uncommon reduced susceptibility to cefpirome. A divergently transcribed ampR gene with an overlapping promoter compared with ampC (blaACC-2) was identified in H. alvei 1, encoding an AmpR protein that shared 64% amino acid identity with the closest AmpR protein from P. stuartii. β-Lactamase induction experiments showed that the ampC gene was repressed in the absence of ampR and was activated when cefoxitin or imipenem was added as an inducer. From H. alvei 1 cultures that expressed an inducible-cephalosporinase phenotype, several ceftazidime- and cefpirome-cross-resistant H. alvei 1 mutants were obtained upon selection on cefpirome- or ceftazidime-containing plates, and H. alvei 1 DER, a ceftazidime-resistant mutant, stably overproduced cephalosporinase. Transformation of H. alvei 1 DER or E. coli JRG582 (ampDE mutant) harboring ampC and ampR from H. alvei 1 with a recombinant plasmid containing ampD from E. coli resulted in a decrease in the MIC of β-lactam and recovery of an inducible phenotype for H. alvei 1 DER. Thus, AmpR and AmpD proteins may regulate biosynthesis of the H. alvei cephalosporinase similarly to other enterobacterial cephalosporinases.

Hafnia alvei is a member of the Enterobacteriaceae family that is associated both with sporadic cases of diarrhea in humans and with hospital-acquired systemic infections (4, 21, 42). The inducible biosynthesis of a naturally occurring Bush group 1 β-lactamase (Ambler class C [2]) has been reported phenotypically for several enterobacterial species, including Citrobacter freundii, Enterobacter aerogenes, Enterobacter cloacae, Morganella morganii, Providencia stuartii, Serratia marcescens, Yersinia enterocolitica, and H. alvei (10, 40, 43, 44, 47). The presence of cephalosporinase in H. alvei may explain its natural phenotype of resistance to aminopenicillins and restricted-spectrum cephalosporins (44). As for other cephalosporinase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, H. alvei isolates may be grouped into two β-lactamase expression phenotypes, low-level inducible cephalosporinase production and oxyimino-cephalosporin sensitivity versus high-level constitutive cephalosporinase production and oxyimino-cephalosporin resistance (44). Interestingly, none of these phenotypes confer resistance to cefoxitin (44).

Both phenotypes of naturally occurring inducible and acquired high-level constitutive cephalosporinase expression have been studied in detail for C. freundii, E. cloacae, and M. morganii (5, 18, 27, 28, 40). An ampR gene (also identified in P. stuartii and Y. enterocolitica) is located upstream and reversely transcribed from ampC. The corresponding protein, a transcriptional regulator belonging to the LysR family, acts as a repressor in the basal level of AmpC biosynthesis and as an activator upon addition of several β-lactams, mostly carbapenems, clavulanate acid, and cephamycins.

The aim of this study was to characterize the cephalosporinase from an H. alvei clinical isolate and to study the regulation of its expression. Its amino acid sequence was compared to those of chromosome-borne and plasmid-mediated cephalosporinases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. H. alvei clinical isolate 1 was from biliary fluid of a patient hospitalized in 1998 at the Hôpital de Bicêtre (Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France). It was identified with the API20-E system (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH10B | araD139 Δ(ara, leu)7697 deoR endA1 galK1 galU nupG recA1 rpsL F′ mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mrcBC) φ80d lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 | Life Technologies, Eragny, France |

| E. coli MC4100 | ΔampC | 19 |

| E. coli JRG582 | ΔampDE | 19 |

| H. alvei 1 | Inducible cephalosporinase phenotype | This report |

| H. alvei 1 DER | In vitro-obtained ceftazidime-resistant mutant of H. alvei 1 | This report |

| M. morganii 5 | Ceftazidime-susceptible strain expressing an inducible cephalosporinase phenotype | 40 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBK-CMV phagemid | Cloning vector; neomycin and kanamycin resistant | Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif. |

| pACYC184 | Cloning vector; chloramphenicol and tetracycline resistant | 11 |

| pNH5 | HpaI fragment containing the ampD gene from E. coli in pBGS18; kanamycin resistant | 19 |

| pDEL-1 | Recombinant plasmid containing a 3.1-kb Sau3AI fragment from genomic DNA of H. alvei 1 in pBK-CMV | This report |

| pDEL-2 | Recombinant plasmid containing ampC and ampR genes of H. alvei 1 in pACYC184 | This report |

| pDEL-3 | Recombinant plasmid containing ampC gene of H. alvei 1 in pACYC184 | This report |

In vitro selection of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant mutants.

Frequencies of in vitro selection of antibiotic-resistant mutants were determined by counting the number of colonies that arose by plating a large inoculum (109 CFU) of H. alvei 1 or M. morganii 5 (40) on antibiotic-containing Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar plates at concentrations of 5 and 10 μg/ml for ceftazidime and 1 μg/ml for cefepime and cefpirome. One ceftazidime-resistant mutant, H. alvei 1 DER, was retained for further analysis.

Susceptibility testing.

The MICs of selected β-lactams were determined by an agar dilution technique as described before (40). The MICs of β-lactams were determined alone or in combination with a fixed concentration of either 2 μg of clavulanic acid per ml or 4 μg of tazobactam per ml for H. alvei isolates 1, H. alvei 1 DER, E. coli DH10B, E. coli MC4100, or E. coli JRG582 harboring several plasmid combinations.

Genetic techniques.

Genomic DNA from H. alvei 1 was extracted, and its Sau3AI-restricted fragments were cloned in phagemid pBK-CMV and expressed in E. coli DH10B as described before (40). Antibiotic-resistant colonies were selected on Trypticase soy (TS) agar plates containing either 50 μg of amoxicillin and 30 μg of kanamycin per ml or 100 μg of cephalothin and 30 μg of kanamycin per ml.

Recombinant plasmid DNAs were studied as described before (39). The cloned DNA fragment from pDEL-1 (see Results and Discussion) was sequenced on both strands using laboratory-designed primers and an Applied Biosystems sequencer (ABI 373). The nucleotide and amino acid sequences were analyzed by using the software available over the Internet at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and at Pedro's Biomolecular Research tools (http://www.fmi.ch/biology/research_tools.html). Multiple sequence alignment of deduced peptide sequences was carried out over the Internet at the University of Cambridge at the website using the program ClustalW. The deduced AmpC and AmpR proteins were compared to those of gram-negative bacterial species possessing ampC or ampR genes.

Using the identified DNA sequence of the cloned fragment of recombinant plasmid pDEL-1 from H. alvei 1 as the template, a set of primers, primer 2 (5′-CCGAGAAATCGGTGACTC-3′) and primer 1 (5′-AAAAGGATCCTTAGTCCTTAGCC-3′) or primer 3 (5′-TCTTTTGCATGCTGATTGGC-3′) and primer 2 were used to PCR amplify the ampC-ampR and ampC genes, respectively, and we cloned the amplimers obtained into the EcoRV site of pACYC184 (30). Both constructs were resequenced in their entirety.

β-Lactamase assays.

β-Lactamase extract from cultures of H. alvei 1 and E. coli DH10B harboring pDEL-1 were obtained as described before (40). Analytical isoelectric focusing was performed with these β-lactamase extracts as reported (40). β-Lactamase extract from a culture of E. coli DH10B(pDEL-1) was further purified as follows. A culture of E. coli DH10B(pDEL-1) was grown overnight at 37°C in 4 liters of TS broth containing cephalothin (100 μg/ml). The bacterial suspension was pelleted, resuspended in 40 ml of 20 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5), disrupted by sonification (three times for 30 s each at 80 kHz; Vibra Cell 300 Phospholyser [Bioblock, Illkirch, France]), and centrifuged for 1 h at 4°C and 48,000 × g. Nucleic acids in the supernatant were precipitated by addition of 0.2 M spermin (7% [vol/vol]) (Sigma) overnight at 4°C. This suspension was ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C and filtered through a 0.45-μm Millipore filter prior to loading onto a preequilibrated Q-Sepharose column (Millipore). The resulting enzyme extract recovered in the flowthrough was then dialyzed against 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) and loaded onto a preequilibrated S-Sepharose column. The proteins were eluted with a linear NaCl gradient (0 to 1 M) in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.8). The β-lactamase was eluted at a concentration of 200 mM NaCl. The β-lactamase was subsequently dialyzed against 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The purified β-lactamase extract was immediately used for determination of relative molecular mass and for kinetic property determinations as described before (39, 40).

The β-lactamase kinetic constants were determined from a culture of E. coli DH10B(pDEL-1) by UV spectrophotometry (spectrophotometer ULTROSPEC 2000; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Orsay, France) as described before (40). Fifty percent inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) were determined for clavulanic acid, tazobactam, cloxacillin, and cefoxitin. Various concentrations of these inhibitors were preincubated with the purified enzyme for 3 min at 30°C to determine the concentrations that reduced the hydrolysis rate of 100 μM cephalothin by 50%. Results are expressed in micromolar units. The specific activity of the purified β-lactamase from E. coli DH10B(pDEL-1) was obtained as described previously with 100 μM cephalothin as the substrate (40).

β-Lactamase basal level determination and induction assays were performed as described before (40, 47) with H. alvei 1, H. alvei 1 DER, H. alvei 1 DER(pNH5), and E. coli MC4100 harboring recombinant plasmids (see Results and Discussion). Induction of β-lactamase content was performed for H. alvei cultures and E. coli cultures with imipenem (0.5 μg/ml) and cefoxitin (5 μg/ml), respectively. The specific β-lactamase activities were obtained as previously described with cephalothin as the substrate (40). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the activity which hydrolyzed 1 μmol of cephalothin per min. The total protein content was measured with the Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Villejuif, France).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper will appear in the GenBank/EMBL nucleotide database under accession no. AF 180952.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Cloning of the ampC gene from H. alvei 1 and identification of the deduced amino acid sequence.

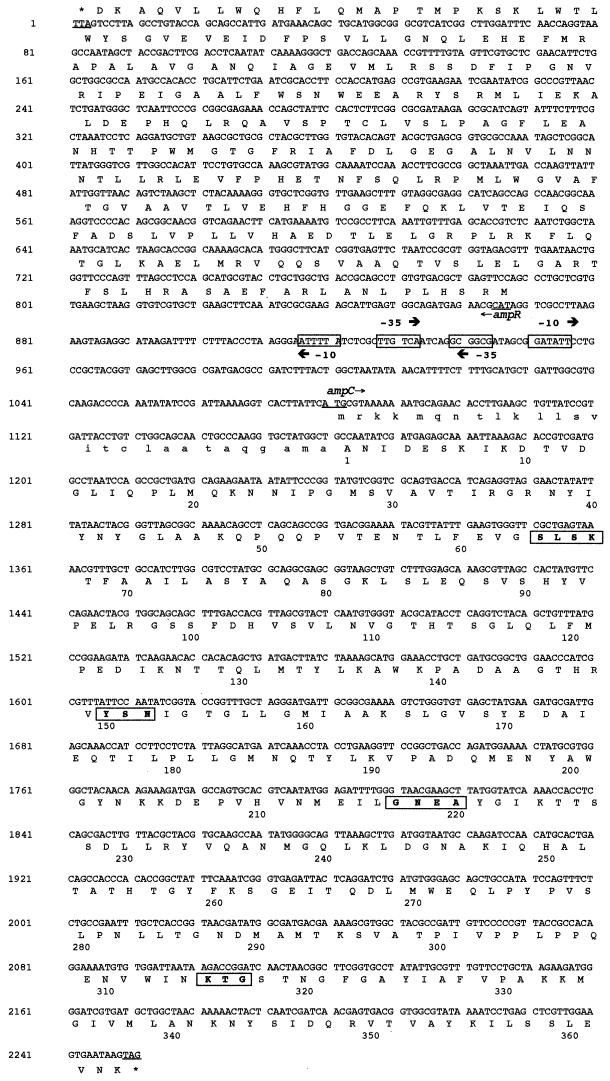

Twenty E. coli DH10B strains harboring recombinant plasmids were obtained by selection on cephalothin-containing MH agar plates, while only one recombinant plasmid was obtained after selection with amoxicillin. One of them, pDEL-1, which possessed a 3.1-kb insert was retained for further restriction digest analysis and sequencing (Fig. 1). A 1,170-bp-long open reading frame (ORF) encoding a putative protein of 390 amino acids was found (Fig. 2). The first 27 amino acids of this protein were assumed to be the signal peptide, because it ended with a typical amino acid sequence (A-X-A) known to be recognized by a signal peptidase (46) (Fig. 2). Within the deduced amino acid sequence of the mature protein, a serine-valine-phenylalanine-lysine tetrad at positions 64 to 67 was found (Fig. 2). It included the conserved serine and lysine amino acid residues characteristic of β-lactamases possessing a serine active site. Of the three structural elements also found in class C β-lactamases, two were present: YSN at positions 150 to 152 and KTG at positions 315 to 317 (31, 32). The third element, although more variable from one AmpC to another (typically DAEA or DAES) at positions 217 to 220, was the tetrad GNEA. Multiple sequence alignment revealed that this class C β-lactamase (ACC-2) shared 94% amino acid identity with ACC-1 (Table 2), a plasmid-mediated cephalosporinase from K. pneumoniae KUS from Germany (6). ACC-2 shared at most 50% identity with other chromosome-borne cephalosporinases from several gram-negative species, such as those of S. marcescens and P. stuartii (Table 2). Interestingly, ACC-2 was not more related to some other enterobacterial cephalosporinases than to those of nonenterobacterial gram-negative species (Table 2).

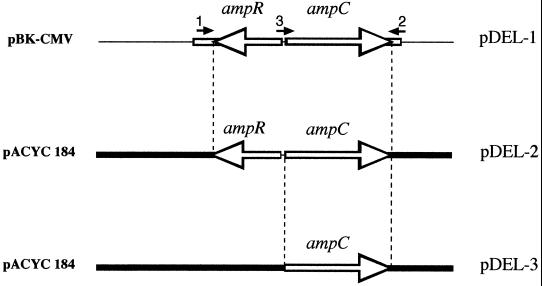

FIG. 1.

Schematic map of recombinant plasmid pDEL-1, carrying the ampR and ampC genes from H. alvei 1, and of its derivatives pDEL-2 and pDEL-3, carrying ampR plus ampC and ampC, respectively. The open lines represent the cloned inserts from H. alvei 1, thin lines indicate vector pBK-CMV, and thick lines represent vector pACYC184. Primers 1, 2, and 3, used to PCR amplify the ampC and ampR genes for the construction of pDEL-2 and pDEL-3, are shown.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence of a 2,252-bp fragment of pDEL-1 including the ampC and ampR coding regions from H. alvei 1. The deduced amino acid sequences are designated in single-letter code. The putative promoter sequences represented by −35 and −10 regions are boxed. The start and stop codons of these genes are underlined. For AmpC, the putative leader peptide is indicated in small capitals, and the numbering begins after the putative leader peptide cleavage site. Additionally, conserved residues among class C β-lactamases are in bold and boxed.

TABLE 2.

Amino acid identities of chromosome- and plasmid-encoded AmpCsa

| Cephalosporinase | % Amino acid identity

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome-encoded cephalosporinases

|

Plasmid-encoded cephalosporinases

|

|||||||||||||||||

| S. mar | P. stu | L. lac | P. imm | E. clo | C. fre | E. col | Y. ent | M. mor | A. sob | P. aer | ACC-1 | CMY-1 | CMY-2 | DHA-1 | FOX-1 | MOX-1 | MIR-1 | |

| H. alv ACC-2 | 49 | 47 | 41 | 40 | 35 | 37 | 36 | 38 | 35 | 40 | 42 | 94 | 40 | 37 | 35 | 42 | 36 | 36 |

| S. mar | 51 | 43 | 38 | 40 | 38 | 39 | 37 | 39 | 42 | 43 | 50 | 42 | 39 | 39 | 44 | 38 | 36 | |

| P. stu | 38 | 35 | 33 | 34 | 32 | 35 | 35 | 36 | 36 | 48 | 36 | 32 | 35 | 38 | 33 | 32 | ||

| L. lac | 37 | 37 | 36 | 35 | 33 | 33 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 44 | 35 | 33 | 43 | 39 | 35 | |||

| P. imm | 36 | 36 | 35 | 38 | 40 | 40 | 38 | 40 | 42 | 36 | 40 | 39 | 34 | 35 | ||||

| E. clo | 73 | 69 | 53 | 54 | 42 | 42 | 35 | 41 | 75 | 54 | 42 | 37 | 86 | |||||

| C. fre | 76 | 55 | 55 | 41 | 40 | 37 | 40 | 95 | 55 | 40 | 35 | 74 | ||||||

| E. col | 57 | 57 | 41 | 41 | 36 | 40 | 77 | 57 | 41 | 35 | 71 | |||||||

| Y. ent | 51 | 40 | 42 | 37 | 39 | 55 | 51 | 41 | 34 | 54 | ||||||||

| M. mor | 42 | 45 | 35 | 41 | 55 | 100 | 44 | 37 | 55 | |||||||||

| A. sob | 53 | 41 | 73 | 42 | 42 | 73 | 65 | 41 | ||||||||||

| P. aer | 40 | 53 | 40 | 45 | 53 | 46 | 43 | |||||||||||

| ACC-1 | 42 | 37 | 35 | 42 | 37 | 35 | ||||||||||||

| CMY-1 | 40 | 41 | 72 | 88 | 39 | |||||||||||||

| CMY-2 | 55 | 40 | 34 | 76 | ||||||||||||||

| DHA-1 | 44 | 37 | 55 | |||||||||||||||

| FOX-1 | 63 | 41 | ||||||||||||||||

| MOX-1 | 34 | |||||||||||||||||

Percent identity between amino acid sequences of chromosome-encoded AmpCs and representative plasmid-encoded cephalosporinases from gram-negative rods. The abbreviations and origins for the chromosome-borne cephalosporinases are as follows: H. alvei, H. alv AAC-2 (this study); Serratia marcescens, S. mar (36); Providentia stuartii, P. stu (Koeck et al., GenBank accession no. Y17315); Lysobacter lactamgenus, L. lac (Kimura et al., GenBank no. S54103); Psychrobacter immobilis, P. imm (12); Enterobacter cloacae, E. clo (14); Citrobacter freundii, C. fre (26); Escherichia coli, E. col (24); Yersinia enterocolitica, Y. ent (43); Morganella morganii, M. mor (40); Aeromonas sobria, A. sob (41); Pseudomonas aeruginosa, P. aer (29). The plasmid-encoded cephalosporinases are ACC-1 from K. pneumoniae KUS (6), CMY-1 from K. pneumoniae (8), CMY-2 from K. pneumoniae (7), DHA-1 from Salmonella enteritidis (3), FOX-1 from K. pneumoniae (15), MOX-1 from K. pneumoniae (20), and MIR-1 from K. pneumoniae (23).

Susceptibility analysis and biochemical properties.

Analysis of the contribution of the cephalosporinase to the overall resistance to β-lactams in H. alvei 1 and E. coli DH10B(pDEL-1) showed that H. alvei 1 was resistant at a low level to amoxicillin and cephalothin, showed decreased susceptibility to ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, and cefpirome, and remained susceptible to cefoxitin, cefepime, imipenem, and aztreonam (Table 3). Expression of β-lactam resistance appeared to be inducible in H. alvei 1, as evidenced by the increased MICs of ceftazidime and cefpirome when clavulanic acid or tazobactam was added, the latest β-lactam inhibitor usually known as a weak inducer of expression of enterobacterial cephalosporinase (1) (Table 3). Expression of ACC-2 in the E. coli host was associated with a significant decrease in susceptibility to amoxicillin, cephalothin, ticarcillin, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, and, uncommonly, to cefpirome, but not significantly to ureidopenicillins, cefoxitin, cefepime, aztreonam, and imipenem (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

MICs of β-lactams for H. alvei 1 clinical isolate, in vitro-obtained ceftazidime-resistant mutant H. alvei 1 DER, E. coli DH10B harboring recombinant plasmid pDEL-1, and the E. coli DH10B reference strain

| β-Lactam(s)a | MIC (μg/ml)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. alvei 1 | H. alvei 1 DER | E. coli DH10B(pDEL-1)b | E. coli DH10B | |

| Amoxicillin | 256 | 512 | 128 | 2 |

| Amoxicillin + CLA | 128 | 512 | 128 | 2 |

| Amoxicillin + TZB | 128 | 512 | 128 | 2 |

| Ticarcillin | 4 | 128 | 8 | 2 |

| Piperacillin | 4 | 128 | 8 | 1 |

| Cephalothin | >512 | >512 | >512 | 4 |

| Cephalothin + CLA | >512 | >512 | >512 | 2 |

| Cephalothin + TZB | >512 | >512 | >512 | 2 |

| Cefamandole | 64 | >512 | 128 | 1 |

| Cefoxitin | 8 | 64 | 8 | 8 |

| Cefotaxime | 0.25 | 128 | 2 | 0.06 |

| Ceftriaxone | 1 | 64 | 4 | <0.06 |

| Ceftazidime | 2 | >512 | 32 | 0.12 |

| Ceftazidime + CLA | 8 | >512 | 32 | 0.12 |

| Ceftazidime + TZB | 8 | >512 | 32 | 0.12 |

| Cefepime | 0.12 | 4 | 0.12 | 0.03 |

| Cefpirome | 0.5 | 16 | 2 | 0.03 |

| Cefpirome + CLA | 2 | 16 | 2 | 0.03 |

| Cefpirome + TZB | 4 | 16 | 2 | 0.03 |

| Imipenem | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| Aztreonam | 1 | 16 | 0.5 | 0.12 |

CLA, clavulanic acid at a fixed concentration of 2 μg/ml; TZB, tazobactam at a fixed concentration of 4 μg/ml.

E. coli DH10B(pDEL-1) expressed cephalosporinase ACC-2 from H. alvei 1.

The specific activity of the purified β-lactamase was 0.75 μmol min−1 (mg of protein)−1. Its overall recovery was 8%, with a 21-fold purification. Kinetic analysis of ACC-2 revealed its strong activity against restricted-spectrum cephalosporins (cephalothin), as known for other cephalosporinases (Table 4) (10). Interestingly, its hydrolysis activity was also noticeable against extended-spectrum cephalosporins, mostly against cefpirome (Table 4). Similar activity is not known for any chromosome- or plasmid-borne cephalosporinases (1, 10, 38, 47), and cefpirome hydrolysis activity had not been tested for ACC-1 (6). This result contrasts with the well-accepted knowledge of resistance of cefpirome to hydrolysis by class C enzymes even when they are overproduced (9). ACC-2 activity was weakly inhibited by clavulanic acid and tazobactam but strongly inhibited by cloxacillin and cefoxitin. The IC50s were 290, 0.008, and 0.0024 μM for tazobactam, cloxacillin, and cefoxitin, respectively (10% inhibition for 300 μM clavulanic acid). The cloxacillin-inhibitory property is well known for cephalosporinases (9), and the cefoxitin-inhibitory property has been reported at least for the chromosome-borne cephalosporinases of C. freundii and P. stuartii (13). This inhibitory property of cefoxitin may explain why (i) E. coli DH10B (pDEL-1) remained susceptible to cefoxitin and (ii) ACC-1 has been reported as being unable to hydrolyze cefoxitin (6).

TABLE 4.

Kinetic parameters of several β-lactam antibiotics for the purified AmpC β-lactamase (ACC-2) of H. alvei 1 from a culture of E. coli DH10B(pDEL-1)a

| Substrate | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (nM−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzylpenicillin | 8.1 | 10 | 816 |

| Amoxicillin | 0.2 | <1 | >0.2 |

| Ticarcillin | <0.05 | — | — |

| Piperacillin | 7.7 | 14 | 550 |

| Cephalothin | 300 | 13 | 23,100 |

| Cefoxitin | <0.01 | — | — |

| Ceftazidime | 0.03 | 5.2 | 7 |

| Cefotaxime | 0.02 | 19 | 1 |

| Cefepime | 3.6 | 147 | 24 |

| Cefpirome | 1.2 | 5.2 | 240 |

| Imipenem | <0.01 | — | — |

| Aztreonam | <0.05 | — | — |

Values are means of three independent measures. —, not determinable (the initial rate of hydrolysis was lower than 1 nM−1 s−1).

The determined relative molecular mass of ACC-2 of 37 kDa corresponded to that calculated by computer for the mature protein. The isoelectric point (pI) value of 8 for ACC-2 determined either from cultures of H. alvei 1 or cultures of E. coli DH10B(pDEL-1) was similar to that found for ACC-1 (6). This pI value was within the range of basic pI values of cephalosporinases (10).

Analysis of the amino acid sequence of ACC-2 did not evidence any specific positions that might explain either its expanded hydrolysis profile for cefpirome or its strong inhibition by cefoxitin. Among the conserved residues of cephalosporinases, only the GNEA motif at positions 217 to 220 was peculiar (31). However, a glycine residue at position 217 is also found in the AmpC of P. stuartii and Y. enterocolitica, and the glutamic acid and alanine residues at positions 219 and 220, respectively, are also found in the chromosome-borne cephalosporinases of E. coli, C. freundii, P. immobilis, Aeromonas sobria, and P. stuartii and in several plasmid-mediated cephalosporinases such as MOX-1, FOX-1, MIR-1, and CMY-2 (data not shown). The extended hydrolysis profile of ACC-2 could not be explained by any amino acid substitutions or additions, as found in several enterobacterial cephalosporinases, such as the amino acid duplication at positions 208 to 213 in E. cloacae and C. freundii and the valine-to-glutamic acid change at position 298 in E. cloacae (17, 31, 34, 37, 45).

In vitro selection of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant mutants.

Since ACC-2 had the peculiar ability to hydrolyze cefpirome, experiments were performed to compare the selection frequency of β-lactam-resistant mutants with several extended cephalosporins with H. alvei 1 and M. morganii 5, the latest strain reported to produce an inducible cephalosporinase that does not significantly hydrolyze cefpirome (40). At a low concentration of ceftazidime (5 μg/ml), the selection frequency of ceftazidime-resistant mutants with H. alvei 1 was similar to that obtained with M. morganii 5 cultures (3.3 × 10−6 to 6.3 × 10−7). However, at a ceftazidime concentration of 10 μg/ml, the selection frequency of ceftazidime-resistant H. alvei 1 mutants was 2.1 × 10−6 ± 0.9 × 10−6, and no ceftazidime-resistant M. morganii 5 mutants were obtained (<2 × 10−8). This results may be partially related to a difference in the MICs of ceftazidime for H. alvei 1 and M. morganii 5, the MICs being 2 and 0.06 μg/ml, respectively. Susceptibility and β-lactamase quantification of one of ceftazidime-resistant H. alvei 1 mutant, H. alvei 1 DER, showed constitutive overproduction of its cephalosporinase and cross resistance to cefpirome (Tables 3 and 5). Resistance to cefpirome in this cephalosporinase-overproducing mutant contrasted with the susceptibility to cefpirome reported for several other enterobacterial species that overproduce their cephalosporinases (9). Although cefepime-resistant H. alvei 1 and M. morganii 5 mutants were not obtained, only cefpirome-resistant H. alvei 1 mutants were obtained at a frequency of 1.4 × 10−7 ± 0.3 × 10−7, with a cefpirome selection of 1 μg/ml. Again, a difference in the MICs of cefpirome for H. alvei 1 and M. morganii 5 (2 and 0.06 μg/ml, respectively) may account for this result. The clinical significance of these experiments would be that (i) it is possible to select ceftazidime-resistant and cefpirome-resistant H. alvei strains in vivo with a therapy that includes either a ceftazidime- or cefpirome-containing treatment and (ii) cefpirome would not always be efficient for treating infections due to either H. alvei isolates overexpressing their cephalosporinases or enterobacterial isolates that produced AAC-2-like plasmid-mediated cephalosporinases such as AAC-1.

TABLE 5.

MICs of several β-lactams and β-lactamase activities for E. coli and H. alvei strains with different genotypes

| Strain | Relevant genotype | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

β-Lactamase activityb (mU/mg of protein)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMX | PIP | CAZ | CTX | CPO | Basal | Induced | ||

| E. coli | ||||||||

| MC4100 | ampD+ ampE+ ampC | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | >0.06 | 0.06 | NDc | ND |

| MC4100(pDEL-2)d | ampD+ ampE+ ampC+ ampR+ | 16 | 8 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 170 | 29,000 |

| MC4100(pDEL-3)d | ampD+ ampE+ ampC+ ampR | 512 | 256 | 512 | 32 | 16 | 5,860 | 7,040 |

| JRG582 | Δ(ampDE) | 1 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.06 | <0.06 | ND | ND |

| JRG582(pDEL-2) | Δ(ampDE) ampC+ ampR+ | 512 | 32 | 64 | 16 | 4 | ND | ND |

| JRG582(pDEL-2, pNH5) | Δ(ampDE) ampC+ ampR+ ampD+ | 128 | 8 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ND | ND |

| H. alvei | ||||||||

| 1 | 256 | 4 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 46 | 4,425 | |

| 1 DERe | 512 | 128 | >512 | 128 | 16 | 6,000 | 4,500 | |

| 1 DER(pNH5)e | ampD+ | 256 | 8 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 23 | 2,500 |

Abbreviations; AMX, amoxicillin; PIP, piperacillin; CAZ, ceftazidime; CTX, cefotaxime; CPO, cefpirome.

β-Lactamase activities are the geometric mean determinations for three independent cultures. The standard deviations were within 10%.

ND, not done.

Cefoxitin (5 μg/ml) was used as the inducer.

Imipenem (0.5 μg/ml) was used as the inducer.

ampR gene from H. alvei 1.

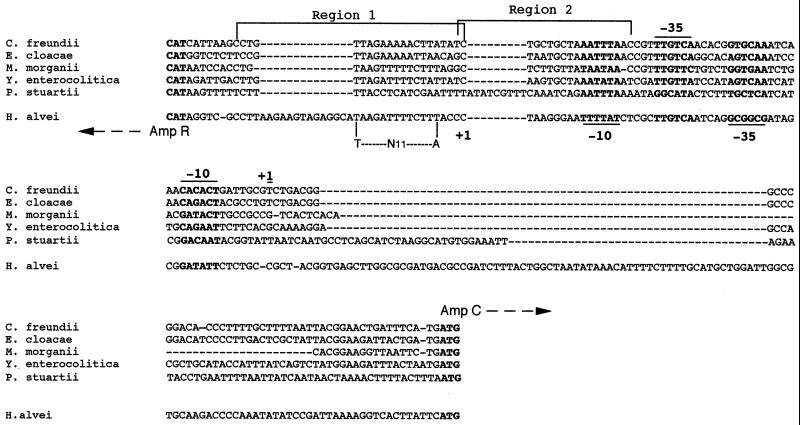

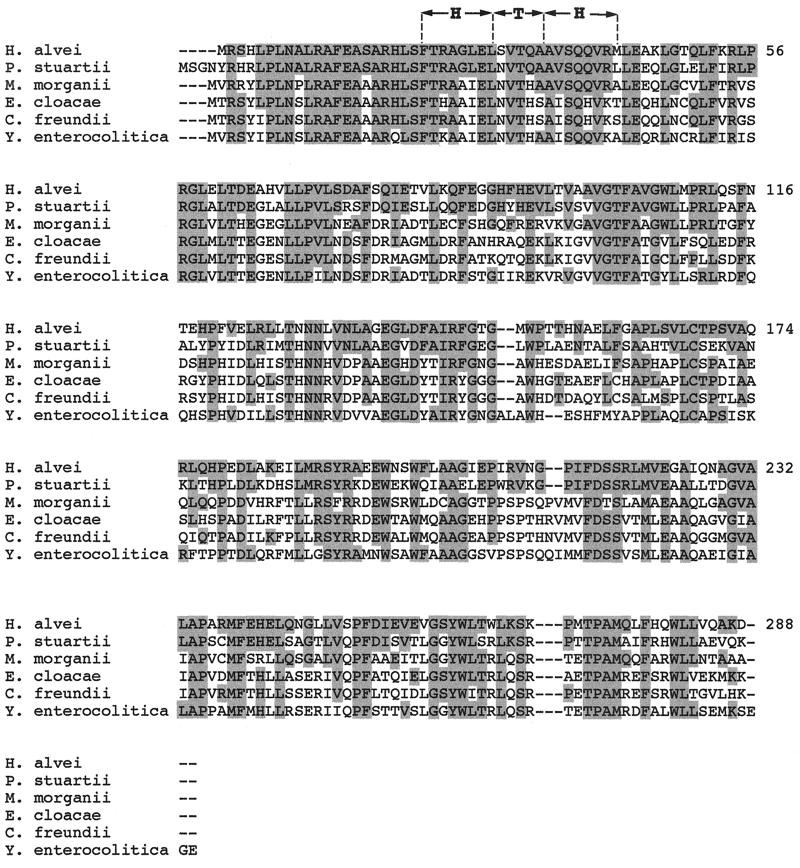

Sequencing of the entire insert of recombinant plasmid pDEL-1 revealed an ampR-like gene upstream and divergently transcribed from the ampC gene (Fig. 2). This gene had an overlapping and divergently oriented promoter, as known for the ampC-ampR cistrons from C. freundii, E. cloacae, M. morganii, P. stuartii, and Y. enterocolitica (Fig. 2). The putative binding sites of AmpR for the regulation of its own expression and of AmpC expression that were identified for C. freundii (29) were also found in H. alvei 1 (Fig. 3). However, just upstream of the region 1 binding site, a 14-bp addition with unknown significance was found as well as additional 39-bp segment upstream from the ATG site of the ampC gene (Fig. 3). The deduced AmpR protein of H. alvei 1 shared significant amino acid identity with AmpR of other enterobacterial species, 64, 51, 48, 47, and 46% for AmpR from P. stuartii, M. morganii, E. cloacae, C. freundii, and Y. enterocolitica, respectively. This identity was mainly within the N-terminal part that contained the helix-turn-helix motif required for binding to the ampR-ampC intercistronic region in C. freundii (28) (Fig. 4). The percentage of identity among enterobacterial AmpR proteins was higher than that among enterobacterial AmpCs. The percentage of amino acid identity among AmpR proteins did not parallel that found for AmpC proteins, although AmpR and AmpC from P. stuartii shared the highest homology with AmpR and AmpC from H. alvei 1. For the 301 bp upstream from the ampR gene of H. alvei 1, no homology was found. However, a further 339 bp upstream, part of an identified ORF shared 74% identity with the glutathione reductase of E. coli (data not shown) (16). Therefore, the location of ampR-ampC in H. alvei may be different from that found in the other enterobacterial species such as M. morganii, in which it is located downstream of an hybF-like gene, and in E. cloacae and C. freundii, in which it is located downstream of the fumarate operon frdABCD (40). Further work may investigate the location of the ampR-ampC cistron in other H. alvei isolates.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the intercistronic regions of ampC-ampR from C. freundii, E. cloacae, M. morganii, P. stuartii, Y. enterocolitica, and H. alvei. The start codons and the −35 and −10 regions of the promoters are shown below the DNA sequences for ampR and above for ampC. The +1 sign indicates the putative mRNA transcription start site. The sequences marked region 1 and region 2 are the two components of the putative AmpR binding site. Only region 1 contains a LysR binding motif (T-N11-A). Dashes indicate gaps introduced in the DNA sequence to optimize the alignment.

FIG. 4.

Multiple amino acid sequence alignment of the known AmpRs from various members of the Enterobacteriaceae. The sequences are for AmpR from C. freundii OS60, E. cloacae MHN-1, M. morganii 1, P. stuartii VDG96, Y. enterocolitica IP97, and H. alvei 1. The predicted helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding motif of the LysR family is shown. Amino acids that are identical to those found in H. alvei are shaded.

Regulation of H. alvei cephalosporinase expression.

Expression of ampC was studied after it was cloned into a plasmid of relatively low copy number (20 to 30 copies), pACYC184. Recombinant plasmids pDEL-2 and pDEL-3 were obtained by cloning the PCR-amplified ampC and ampR genes and the ampC gene, respectively (Fig. 1). E. coli MC4100(pDEL-2) had an inducible cephalosporinase phenotype in the presence of cefoxitin (170-fold increase), while E. coli MC4100(pDEL-3), which lacks the ampR gene, showed an increase in basal cephalosporinase expression (34-fold) along with a loss of inducibility (Table 5). Similarly, the MICs of β-lactams were higher for E. coli MC4100(pDEL-3) than for E. coli MC4100(pDEL-2), most noticeably for ceftazidime and cefpirome (Table 5). Similar results were obtained with C. freundii, E. cloacae, and M. morganii cephalosporinases, for which ampR deletion resulted in an increase in β-lactamase expression and a loss of inducibility (5, 18, 19, 40). Thus, AmpR acted in H. alvei as a negative regulator of cephalosporinase expression in the absence of a β-lactam inducer and as an activator in its presence.

The level of cephalosporinase from H. alvei 1 indicated a low level and inducible biosynthesis (Table 5). An in vitro-selected ceftazidime-resistant mutant, H. alvei 1 DER, produced a high level and constitutive expression of this cephalosporinase (Table 5). The susceptibility of H. alvei 1 DER to all β-lactams was decreased, especially to cefpirome, compared with the parental H. alvei 1 (Table 3). According to the results obtained with the regulatory systems of other enterobacterial cephalosporinases, H. alvei 1 DER might possess mutations either in the promoter of an ampD-like gene or within its structural gene. To test this hypothesis, H. alvei 1 DER was transformed with plasmid pNH5 containing an ampD gene from E. coli. A decrease in β-lactam MICs and cephalosporinase was obtained together with the recovery of an inducible phenotype (Table 5). Similarly, E. coli JRG582 (ΔampDE) harboring the ampC and ampR genes from H. alvei 1 with or without the same ampD gene showed lower β-lactam MICs in the presence of ampD (Table 5) and an inducible cephalosporinase expression phenotype (data not shown). These results indicated that AmpD from E. coli may act in trans as a regulatory protein for expression of H. alvei cephalosporinase in a similar manner as for the cephalosporinase of E. cloacae (18). Such complementation with an ampD gene from another enterobacterial species is known for cephalosporinase regulation in C. freundii, E. cloacae, and M. morganii (5, 18, 40). Thus, regulation of the cephalosporinase of H. alvei may be similar to that extensively described for E. cloacae (22). In the absence of a β-lactam as an inducer, the AmpR regulator is maintained in an inactive form by a peptidoglycan precursor, uridine pyrophosphoryl-N-acetyl muramyl-l-alanyl-d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid-d-alanyl-d-alanine (UDP-MurNac-pentapeptide) and binds to its operator site between the ampC and ampR structural genes, leading to repression of ampC expression. This inactivation of AmpR can be relieved by either a knockout mutation in the ampD gene or the presence of a β-lactam. Inactivation of ampD by mutations in its promoter or in its structural gene, which encodes a cytosolic amidase specific for the recycling of muropeptides, results in an accumulation of its substrate, the 1,6-anhydro-N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanyl-d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid (anhMurNac-tripeptide). The increased concentration of this muropeptide inside the cell displaces the UDP-MurNac-pentapeptide from its AmpR binding site, thereby reactivating AmpR. The ampD mutants are therefore highly resistant to β-lactams as a result of constitutive hyperproduction of the AmpC β-lactamase in the absence of β-lactams (22).

Conclusion.

Although the chromosome-encoded AmpC enzymes from H. alvei are not related to any known chromosome-encoded cephalosporinase, it is related to the recently described plasmid-encoded cephalosporinase ACC-1 from K. pneumoniae KUS. This is the fourth example of a plasmid-encoded cephalosporinase highly related to the chromosome-encoded cephalosporinases of C. freundii (CMY-2, CMY-3, LAT-1, LAT-2, LAT-3, and LAT-4), E. cloacae (MIR-1 and ACT-1), and M. morganii (DHA-1), showing that members of the Enterobacteriaceae are a reservoir for plasmid-encoded cephalosporinases. The mechanism by which chromosome-encoded cephalosporinases became plasmid encoded has not yet been discovered. Interestingly, comparison of the upstream region of blaACC-1 with that of blaACC-2 revealed 93% identity among the 66 bp just upstream of the blaACC-2 ATG site. Further upstream, the homology was interrupted. A careful analysis of this region upstream from the blaACC-1 sequence in K. pneumoniae KUS revealed sequence identities with a putative insertion sequence, ISEcp1, and, further upstream, IS26 (25, 33; P. D. Stapleton, unpublished data [GenBank no. AJ242809]). The IS26 outwards-reading promoter is directed in the same orientation as blaACC-1 indicating that this insertion sequence may drive β-lactamase expression in K. pneumoniae KUS, as shown, for example, for blaSHV-2a in a P. aeruginosa isolate (35). Insertion sequences and transposons are known to capture genes and to transpose them, being major players in the genetic plasticity of bacteria. It would be interesting to investigate further the plasmid carrying blaACC-1 to see whether a composite IS26 transposon is responsible for its plasmid location.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was funded by a grant from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale et de la Recherche, Université Paris XI, Faculté de Médecine Paris Sud (grant UPRES, JE-2227).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akova M, Yang Y, Livermore D M. Interactions of tazobactam and clavulanate with inducibly- and constitutively-expressed class I β-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;25:199–208. doi: 10.1093/jac/25.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambler R P. The structure of β-lactamases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1980;289:321–331. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1980.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnaud G, Arlet G, Verdet C, Gaillot O, Lagrange P H, Philippon A. Salmonella enteritidis: AmpC plasmid-mediated inducible β-lactamase (DHA-1) with an ampR gene from Morganella morganii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2352–2358. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.9.2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry J W, Dominguez E A, Boken D J, Preheim L C. Hafnia alvei infection after liver transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1263–1264. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.6.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartowsky E, Normark S. Interactions of wild-type and mutant AmpR of Citrobacter freundii with target DNA. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:555–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauernfeind A, Schneider I, Jungwirth R, Sahly H, Ullmann U. A novel type of AmpC β-lactamase, ACC-1, produced by a Klebsiella pneumoniae strain causing nosocomial pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1924–1931. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.8.1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauernfeind A, Stemplinger I, Jungwirth R, Giamarellou H. Characterization of the plasmidic β-lactamase CMY-2, which is responsible for cephamycin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:221–224. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.1.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauernfeind A, Stemplinger I, Jungwirth R, Wilhelm R, Chong Y. Comparative characterization of the cephamycinase blaCMY-1 gene and its relationship with other β-lactamase genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1926–1930. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonfiglio G, Stefani S, Nicoletti G. In vitro activity of cefpirome against beta-lactamase-inducible and stably derepressed Enterobacteriaceae. Chemotherapy. 1994;40:311–316. doi: 10.1159/000239212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bush K, Jacoby G A, Medeiros A A. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1211–1233. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang A C, Cohen S N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feller G, Zekhini Z, Lamotte-Brasseur J, Gerday C. Enzymes from cold-adapted microorganisms. The class C beta-lactamase from the Antartic psychrophile Psychrobacter immobilis A5. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244:186–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu K P, Neu H C. The comparative beta-lactamase resistance and inhibitory activity of 1-oxa cephalosporin, cefoxitin and cefotaxime. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1979;32:909–914. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.32.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galleni M, Lindberg F, Normark S, Cole S, Honoré N, Joris B, Frère J-M. Sequence and comparative analysis of three Enterobacter cloacae ampC β-lactamase genes and their products. Biochem J. 1988;250:753–760. doi: 10.1042/bj2500753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez Leiza M, Perez-Diaz J C, Ayala J, Casellas J M, Martinez-Beltran J, Bush K, Baquero F. Gene sequence and biochemical characterization of FOX-1 from Klebsiella pneumoniae, a new AmpC-type plasmid-mediated β-lactamase with two molecular variants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2150–2157. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greer S, Perham R N. Glutathione reductase from Escherichia coli: cloning and sequence analysis of the gene and relationship to other flavoprotein disulfide oxidoreductases. Biochemistry. 1986;25:2736–2742. doi: 10.1021/bi00357a069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haruta S, Nukaga M, Taniguchi K, Sawai T. Resistance to oxyimino β-lactams due to a mutation of chromosomal β-lactamase in Citrobacter freundii. Microbiol Immunol. 1998;42:165–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1998.tb02267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honoré N, Nicolas M H, Cole S T. Inducible cephalosporinase production in clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae is controlled by a regulatory gene that has been deleted from Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1986;5:3709–3714. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honoré N, Nicolas M H, Cole S T. Regulation of enterobacterial cephalosporinase production: the role of a membrane-bound sensory transducer. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1121–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horii T, Arakawa Y, Ohta M, Sugiyama T, Wacharotayankun R, Ito H, Kato N. Characterization of a plasmid-borne and constitutively expressed blaMOX-1 gene encoding AmpC-type β-lactamase. Gene. 1994;139:93–98. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90529-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ismaili A, Bourke B, De Azavedo J C, Ratnam S, Karmali M A, Sherman P M. Heterogeneity in phenotypic and genotypic characteristics among strains of Hafnia alvei. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2973–2979. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.2973-2979.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs C, Frère J M, Normark S. Cytosolic intermediates for cell wall biosynthesis and degradation control inducible β-lactam resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Cell. 1997;88:823–832. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81928-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacoby G A, Tran J. Sequence of the MIR-1 beta-lactamase gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1759–1760. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.7.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaurin B, Grunström T. ampC cephalosporinase of Escherichia coli K-12 has a different evolutionary origin from that of β-lactamases of the penicillinase type. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:4897–4901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee K Y, Hopkins J D, Syvanen M. Direct involvement of IS26 in an antibiotic resistance operon. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3229–3236. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3229-3236.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindberg F, Normark S. Sequence of the Citrobacter freundii OS60 chromosomal ampC beta-lactamase gene. Eur J Biochem. 1986;156:441–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindberg F, Westman L, Normark S. Regulatory components in Citrobacter freundii ampC β-lactamase induction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4620–4624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.14.4620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindquist S, Lindberg F, Normark S. Binding of the Citrobacter freundii AmpR regulator to a single DNA site provides both autoregulation and activation of the inducible ampC β-lactamase gene. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3746–3753. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3746-3753.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lodge J M, Minchin S D, Piddock L J, Busby J W. Cloning, sequencing and analysis of the structural gene and regulatory region of Pseudomonas aeruginosa chromosomal AmpC-β-lactamase. Biochem J. 1990;272:627–631. doi: 10.1042/bj2720627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsumura N, Minami S, Mitsuhashi S. Sequences of homologous β-lactamases from clinical isolates of Serratia marcescens with different substrate specificities. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:176–179. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.1.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medeiros A A. Evolution and dissemination of β-lactamases accelerated by generations of β-lactam antibiotics. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:S19–S45. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_1.s19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mollet B, Iida S, Shepherd J, Arber W. Nucleotide sequence of IS26, a new prokaryotic mobile genetic element. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:6319–6330. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.18.6319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morosini M I, Negri M C, Shoichet B, Baquero M R, Baquero F, Blazquez J. An extended-spectrum AmpC-type β-lactamase obtained by in vitro antibiotic selection. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;165:85–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naas T, Philippon L, Poirel L, Ronco E, Nordmann P. An SHV-derived extended-spectrum beta-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1281–1284. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nomura K, Yoshida T. Nucleotide sequence of the Serratia marcescens SR50 chromosomal ampC beta-lactamase gene. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;58:295–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb13992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nukaga M, Haruta S, Tanimoto K, Kogure K, Taniguchi K, Tamaki M, Sawai T. Molecular evolution of a class C β-lactamase extending its substrate specificity. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5729–5735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.5729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phelps D J, Carlton D D, Farrell C A, Kessler R E. Affinity of cephalosporins for β-lactamases as a factor in antibacterial efficacy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;29:845–848. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.5.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Philippon L N, Naas T, Bouthors A T, Barakett V, Nordmann P. OXA-18, a class D clavulanic acid-inhibited extended-spectrum β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2188–2195. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poirel L, Guibert M, Girlich D, Naas T, Nordmann P. Cloning, sequence analyses, expression, and distribution of ampC-ampR from Morganella morganii clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:769–776. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.4.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rasmussen B A, Keeney D, Yang Y, Bush K. Cloning and expression of a cloxacillin-hydrolyzing enzyme and a cephalosporinase from Aeromonas sobria AER 14M in Escherichia coli: requirement for an E. coli chromosomal mutation for efficient expression of the class D enzyme. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2078–2085. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ridell J, Siitonen A, Paulin L, Mattila L, Korkeala H, Albert M J. Hafnia alvei in stool specimens from patients with diarrhea and healthy controls. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2335–2337. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.9.2335-2337.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seoane A, Francia M V, Garcia-Lobo J M. Nucleotide sequence of the ampC-ampR region from the chromosome of Yersinia enterocolitica. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1049–1052. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.5.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomson K S, Sanders C C, Washington J A., II Ceftazidime resistance in Hafnia alvei. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1375–1376. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.6.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsukamoto K, Ohno R, Sawai T. Extension of the substrate spectrum by an amino acid substitution at residue 219 in the Citrobacter freundii cephalosporinase. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4348–4351. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4348-4351.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.von Heijne G. Signal sequences: the limits of variation. J Mol Biol. 1985;184:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang Y, Livermore D M, Williams R J. Chromosomal β-lactamase expression and antibiotic resistance in Enterobacter cloacae. J Med Microbiol. 1988;25:227–233. doi: 10.1099/00222615-25-3-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]