Abstract

Objectives

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted healthcare systems, challenging neonatal care provision globally. Curtailed visitation policies are known to negatively affect the medical and emotional care of sick, preterm and low birth weight infants, compromising the achievement of the 2030 Development Agenda. Focusing on infant and family-centred developmental care (IFCDC), we explored parents’ experiences of the disruptions affecting newborns in need of special or intensive care during the first year of the pandemic.

Design

Cross-sectional study using an electronic, web-based questionnaire.

Setting

Multicountry online-survey.

Methods

Data were collected between August and November 2020 using a pretested online, multilingual questionnaire. The target group consisted of parents of preterm, sick or low birth weight infants born during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic and who received special/intensive care. The analysis followed a descriptive quantitative approach.

Results

In total, 1148 participants from 12 countries (Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, Poland, Sweden, Turkey and Ukraine) were eligible for analysis. We identified significant country-specific differences, showing that the application of IFCDC is less prone to disruptions in some countries than in others. For example, parental presence was affected: 27% of the total respondents indicated that no one was allowed to be present with the infant receiving special/intensive care. In Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand and Sweden, both the mother and the father (in more than 90% of cases) were allowed access to the newborn, whereas participants indicated that no one was allowed to be present in China (52%), Poland (39%), Turkey (49%) and Ukraine (32%).

Conclusions

The application of IFCDC during the COVID-19 pandemic differs between countries. There is an urgent need to reconsider separation policies and to strengthen the IFCDC approach worldwide to ensure that the 2030 Development Agenda is achieved.

Keywords: COVID-19, Public health, Neonatal intensive & critical care, NEONATOLOGY, PUBLIC HEALTH, Health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

With this survey, 1148 parents were asked about their experiences of the disruptions affecting newborns in need of special or intensive care during the first year of the pandemic.

Data were collected in 12 countries via a pretested online survey with 52 questions.

In a cross-country approach, differences in providing infant and family-centred developmental care were analysed between countries.

The pandemic situation, geographical, climatic and environmental aspects and containment strategies were considered in between-country analyses.

The online format of the study bears the risk of selection bias, and response rates could not be calculated.

Introduction

During the last decades, major achievements have been made in the field of maternal and newborn health, particularly in light of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.1 While efforts have resulted in a reduction of maternal and neonatal deaths and better health outcomes for newborns worldwide, progress, in particular, affecting preterm, sick and low birth weight infants has been slow.1 2 Pandemic-related shortages in maternal and newborn care provision have severe consequences for vulnerable infants and their families,3–5 continuing to threaten the achievement of the 2030 Development Agenda.6

Worldwide, 1 in 10 infants is born preterm every year, with increasing rates in almost all countries where reliable epidemiologic data sets are available, making it a truly global problem.7 Preterm birth is the leading cause of death under 5 years of age, and together with birth complications, it is the leading cause of neonatal death.6 8 9 The extremely fragile group of patients requires highly specialised care, which is labour and cost intense, and, thus, stark regional discrepancies in the availability of specialised care are well described.10 However, while international agreements, like the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child or the European Association for Children in Hospital, foster the right of children to be close to their parents,11 12 these rights have not yet been implemented in the majority of neonatal units across the globe where parents and their newborns have often been separated—already in prepandemic times—yet increasingly as a response to the ongoing global health crisis.13–15 Before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the globe, an increasing number of neonatal units worldwide had adopted the principles of infant and family-centred developmental care (IFCDC), such as unrestricted parental access, active parental participation and involvement and kangaroo mother care (KMC).16 17 However, IFCDC is so far still a new concept and its implementation remains to be one of the biggest challenges in neonatal care as it also requires a fundamental change in the mentality of neonatal caregivers.16–20

The COVID-19 pandemic and related restrictions have resulted in severe limitations in neonatal care provision,18 especially regarding acknowledged elements of IFCDC.15 21–27 The frequently implemented separation of parents and their newborns has negative implications for the health outcomes of newborns,28–30 interfering with acknowledged practices such as KMC, skin-to-skin contact31 and breast feeding.32 The reduction of parental presence in the neonatal intensive care units (NICU) has led to increased stress and mental health problems among parents and families, raising the risk of postnatal depression and post-traumatic stress syndrome and limited opportunities for parent–infant bonding,14 15 while staff shortages and the lack of available guidelines have led to high levels of stress and anxiety among health professionals.21 33 Few studies and reports have provided insights into parents’ experiences regarding some of the implemented restrictions.14 15 34 However, a comparative and holistic approach, emphasising the cornerstones of IFCDC, has been missing so far, which is the focus of this research.

With this study, we explored parents’ experiences of disruptions to neonatal care during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic across the globe, focusing on individual country actions. We aimed to document the challenges experienced by parents, spanning wide variations across countries and regions. The analysis and corresponding findings shall provide an incentive for policymakers, public health experts and healthcare professionals alike to learn from the different approaches and subsequent implications of the outcomes of single countries and underline the importance of parents’ involvement in the care of vulnerable newborns. It is imperative that this occurs, irrespective of the ongoing pandemic or future emergency situations.

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted a cross-sectional study using an electronic, web-based questionnaire with the aim to explore parents’ experiences during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic with regards to the core elements of IFCDC. Eligible for participation were parents of preterm, sick or low birth weight infants born during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (as of 1 December 2019) and who were receiving special or intensive care (inclusion criteria). The term ‘parent’ was broadly defined, encompassing biological and/or social parents, allowing for self-definition as ‘mother’, ‘father’ or ‘other parent’. We conducted and reported the study according to the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys.35

Participants were recruited by the European Foundation for the Care of Newborn Infants (EFCNI), and its initiative, the Global Alliance for Newborn Care (GLANCE), through social media activities, newsletters, website outreach and mailings. In addition, national parent organisations and the collaborating professional healthcare associations and their members, namely, the Council of International Neonatal Nurses (COINN), the European Society for Paediatric Research (ESPR), the Neonatal Individualised Developmental Care and Assessment Project (NIDCAP) and the Union of European Neonatal and Perinatal Societies (UENPS), supported the dissemination of the survey link by promoting the study across their networks. Participation was voluntary, data collection occurred anonymously.

Questionnaire development and pretesting

Researchers of the EFCNI scientific department developed the questionnaire in collaboration with the members of the COVID-19 Zero Separation Collaborative Group—an interdisciplinary stakeholder group including medical experts and parent/patient representatives. The survey was pretested among n=8 parents who met the target group criteria who did not request any changes of the questionnaire.

The questionnaire consisted of 52 questions with predefined answers and single or multiple response answer options (online supplemental material S9). It encompassed information about the respondent and infant, and COVID-19-related topics as well as categories of IFCDC,25 including the following elements: (1) background information, (2) COVID-19 testing and measures in the respective country/region, (3) access to perinatal care, (4) presence with the newborn receiving special/intensive care, (5) breast feeding/infant nutrition, (6) health communication and (7) mental health and support. Parent representatives from EFCNI’s international parent network supported the translations of the final version into 23 languages, which were all reviewed and approved by native medical professionals.

bmjopen-2021-056856supp001.pdf (5.3MB, pdf)

Data collection and statistical analysis

Data were collected between August and November 2020 using the SurveyMonkey online survey tool. The analysis included answers from all respondents who met the inclusion criteria, regardless of whether they completed the survey to the end. The subsequent analysis was performed as subanalysis based on a global survey with available data from 56 countries as previously described elsewhere.18 For this subanalysis, countries having a minimum of at least 30 answers per country were considered eligible for inclusion. A subsequent country selection depending on predefined criteria, such as sample size, geographical variation (continent, north/south) and COVID-19 situation,36 37 was conducted by the five main authors of this study using a consensus approach with ranking and voting. Recently published scientific articles on different countries’ COVID-19-related preparedness, responses and implemented restrictions38–42 acted as a basis for a comprehensive and diverse country selection, resulting in the following included countries: Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, Poland, Sweden, Turkey and Ukraine.

Data analysis was conducted using an exploratory approach with descriptive statistics (number of answers and proportion (n (%))). Multiple-answer questions were analysed as the sum of the number of responses per answer choice (n (%)) and may exceed 100%. A 95% CI was calculated (CI for proportions) for questions related to presence with the newborn and skin-to-skin care using one answer option in order to determine statistically significant deviations between countries and the overall total. A colour coding indicated that countries whose 95% CI did not overlap and was significantly different from the proportion of all countries (country higher (blue) or country lower (green)). All analyses presented herein were carried out using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V.27–0, IBM Corp, Armonk, New York) and Microsoft Excel (V.16).

Patient and public involvement

EFCNI, as a pan-European network of parent organisations, was the initiator of this research project and responsible for all phases of the study. In addition, representatives from national parent organisations worldwide were involved in the review of the questionnaire and in manuscript writing (as part of the COVID-19 Zero Separation Collaborative Group). Additionally, they supported the translation and dissemination of the survey in their network, and will again be involved in the dissemination of the results.

Results

Background, baseline and COVID-19-related characteristics

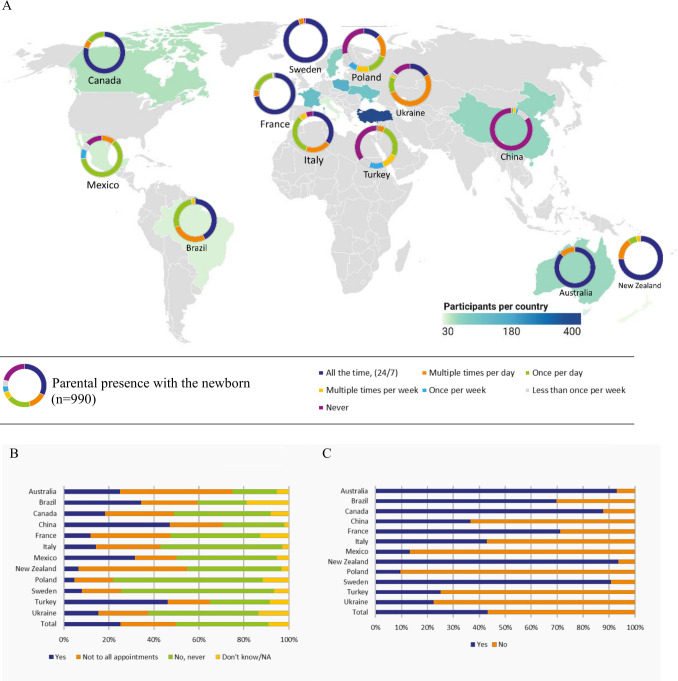

In total, 1148 participants from Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, Poland, Sweden, Turkey and Ukraine were eligible for analysis (figure 1A). Baseline characteristics of participants are shown in table 1. Nearly all answers were obtained from mothers of the infant (n=1093; 95%), and the majority of participants was between 30 and 39 years old (53%). Most infants were born very preterm (28 to <32 weeks of gestation; 35%) or moderate to late preterm infants (32 to <37 weeks of gestation; 37%) and were born through caesarean section (72%). Almost 50% of the infants required special/intensive care for over 5 weeks at the time of answering the questionnaire (table 1). Baseline characteristics of participants per country are prespecified in online supplemental table S1 and partly differed on country level.

Figure 1.

Distribution of respondents by country and parental presence with newborn per country (A), presence of support persons during pregnancy-related appointments (B) and labour companionship (C).

Table 1.

Baseline and COVID-19 characteristics of participants

| Total | |

| Age of respondent (years) | n=1146 |

| <20 | 5 (0%) |

| 20–29 | 468 (41%) |

| 30–39 | 608 (53%) |

| >40 | 65 (6%) |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | n=1107 |

| Early preterm:<28 | 270 (24%) |

| Very preterm: 28–<32 | 389 (35%) |

| Moderate to late preterm: 32–<37 | 412 (37%) |

| Term: 37–42 | 36 (3%) |

| Multiple pregnancy | n=1112 |

| Yes | 180 (16%) |

| No | 932 (84%) |

| Birth mode | n=1111 |

| Vaginal birth | 301 (27%) |

| C-section | 804 (72%) |

| Both (eg, in case of multiple pregnancy) | 6 (1%) |

| Birth weight of the baby (grams) | n=1110 |

| <1000 | 290 (26%) |

| 1000–1500 | 373 (34%) |

| >1500–2500 | 374 (34%) |

| >2500 | 71 (6%) |

| Do not know the birth weight | 2 (0%) |

| Duration of special/intensive care (weeks) (at time of data collection) | n=1112 |

| <1 | 81 (7%) |

| 1–3 | 251 (23%) |

| >3–5 | 277 (25%) |

| >5 | 503 (45%) |

| COVID-19 situation in country/region at time of baby’s birth | n=1071 |

| No major concern | 49 (5%) |

| Precautions | 137 (13%) |

| Social distancing | 325 (30%) |

| Lockdown | 438 (41%) |

| Quarantine | 122 (11%) |

| Have you tested positive for coronavirus/COVID-19? | n=1084 |

| Yes | 27 (2%) |

| No | 1057 (98%) |

| Has your partner tested positive for coronavirus/COVID-19? | n=1086 |

| Yes | 25 (2%) |

| No | 1039 (96%) |

| Do not know | 22 (2%) |

| Has your baby tested positive for coronavirus/COVID-19? | n=1087 |

| Yes | 5 (0%) |

| No | 1035 (95%) |

| Do not know | 47 (4%) |

Overall, 41% of the respondents faced lockdown measures in their country/region at the time of birth, 30% were encouraged to adhere to social distancing and 13% were located in countries/regions where precautions were advised or quarantine was implemented (11%, table 1). In total, 2% of the respondents and 2% of the respondents’ partners had tested positive for COVID-19, with the highest numbers in Mexico (12% for both options). Overall, five newborns tested positive for COVID-19 (table 1).

Online supplemental table S2 provides an overview on each countries’ demographics, including GDP (gross domestic product) per capita, the preterm birth rate, female educational attainment, maternal and under-five mortality, sanitation, COVID-19 cases as of 29 November 202037 and the average government response stringency index based on the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker43 between August and November 2020. Overall, Turkey (12%) and Brazil (11%) have the highest observed preterm birth rate, while it is lowest in Sweden (6%).9 Data from the World Bank44 and the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation45 from 2019 show that Brazil also has the highest rate of maternal mortality per 100 000 live births (60) and the highest under five mortality rate per 1000 live births, together with Mexico (14). As of 29 November 2020, cumulative COVID-19 cases per 1 million population were highest in France (33 242), followed by Brazil (29 349). Cases were lowest in China (63) and New Zealand (352). The average government response stringency index43 was highest in China (80) and lowest in New Zealand (22).

Prenatal care and birth

Significant variations regarding the presence of support persons during pregnancy-related appointments and birth could be observed (figure 1B, C). In total, 41% of all participants were not allowed to have a companion present during pregnancy-related appointments. This number was highest in Sweden and Poland (>60%) and lowest in Australia (20%). During birth, 57% of the respondents were not permitted to have another person present (figure 1C). In Mexico, 87% of the women gave birth without a supporting companion. In Poland, this applied to 90% of the respondents. In Australia, New Zealand and Sweden >90% of the women were permitted to have another person present, and in Australia, 90% of the accompanying persons could stay for the entire labour (online supplemental table S3). Likewise, in Brazil, China and New Zealand, >85% of the accompanying persons could stay during the entire labour (online supplemental table S3).

Presence with the newborn and skin-to-skin care

In total, 82% of the participants responded that the COVID-19 pandemic affected the facility policy around their ability to be present with the newborn receiving special/intensive care (table 2). Parental presence was one of the areas affected most, with 27% of the total respondents indicating that no one was allowed to be present with the newborn, with highest numbers in China (52%) and Turkey (49%).

Table 2.

Presence with the newborn and skin-to-skin care

| Total | Australia | Brazil | Canada | China | France | Italy | Mexico | New Zealand | Poland | Sweden | Turkey | Ukraine | |

| Do you know if the coronavirus/COVID-19 situation affected the facility policy around your ability to be present with the baby receiving special/intensive care? | |||||||||||||

| n=991 | n=55 | n=34 | n=49 | n=52 | n=110 | n=34 | n=37 | n=31 | n=132 | n=73 | n=288 | n=96 | |

| There were no changes | 80 (8%) | 7 (13%) | 2 (6%) | 2 (4%) | 5 (10%) | 12 (11%) | 4 (12%) | 2 (5%) | 4 (13%) | 4 (3%) | 23 (32%) | 10 (3%) | 5 (5%) |

| Restrictions were implemented | 816 (82%) | 44 (80%) | 30 (88%) | 44 (90%) | 36 (69%) | 94 (85%) | 27 (79%) | 34 (92%) | 25 (81%) | 118 (89%) | 44 (60%) | 241 (84%) | 79 (82%) |

| I do not know if there were changes | 95 (10%) | 4 (7%) | 2 (6%) | 3 (6%) | 11 (21%) | 4 (4%) | 3 (9%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) | 10 (8%) | 6 (8%) | 37 (13%) | 12 (13%) |

| Who was allowed to be present with your baby receiving special/intensive care? (multiple answers possible) | |||||||||||||

| n=991 | n=55 | n=34 | n=49 | n=52 | n=110 | n=34 | n=37 | n=31 | n=132 | n=73 | n=288 | n=96 | |

| Sum of multiple answers | 1497 (151%) | 112 (204%) |

57

(168%) |

89

(182%) |

73

(140%) |

215 (195%) |

59

(174%) |

57

(154%) |

56

(181%) |

155 (117%) | 145 (199%) | 368 (128%) | 111 (116%) |

| Mother | 680 (69%) | 52 (95%) | 30 (88%) | 44 (90%) | 18 (35%) | 101 (92%) | 30 (88%) | 25 (68%) | 28 (90%) | 84 (64%) | 60 (82%) | 142 (49%) | 66 (69%) |

| Father/partner | 501 (51%) | 54 (98%) | 24 (71%) | 42 (86%) | 15 (29%) | 106 (96%) | 27 (79%) | 23 (62%) | 26 (84%) | 19 (14%) | 68 (93%) | 84 (29%) | 13 (14%) |

| Sibling/s | 27 (3%) | 3 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (6%) | 6 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) |

| Other family members | 14 (1%) | 3 (5%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Friends | 2 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| No one | 265 (27%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 27 (52%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (6%) | 8 (22%) | 0 (0%) | 52 (39%) | 1 (1%) | 141 (49%) | 31 (32%) |

| I do not know | 8 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (13%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Could more than one person be present with the baby at the same time? | |||||||||||||

| n=990 | n=55 | n=34 | n=49 | n=52 | n=110 | n=34 | n=37 | n=31 | n=130 | n=74 | n=288 | n=96 | |

| Yes | 326 (33%) | 31 (56%) | 9 (26%) | 20 (41%) | 27 (52%) | 70 (64%) | 2 (6%) | 2 (5%) | 16 (52%) | 5 (4%) | 62 (84%) | 66 (23%) | 16 (17%) |

| No | 664 (67%) | 24 (44%) | 25 (74%) | 29 (59%) | 25 (48%) | 40 (36%) | 32 (94%) | 35 (95%) | 15 (48%) | 125 (96%) | 12 (16%) | 222 (77%) | 80 (83%) |

| How long were you allowed to see your baby per visit? | |||||||||||||

| n=989 | n=55 | n=34 | n=49 | n=52 | n=109 | n=34 | n=37 | n=31 | n=131 | n=73 | n=288 | n=96 | |

| Up to an hour | 338 (34%) | 1 (2%) | 11 (32%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (32%) | 31 (84%) | 0 (0%) | 44 (34%) | 0 (0%) | 186 (65%) | 52 (54%) |

| More than 1 hour, up to 3 hours | 41 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (8%) | 5 (5%) | 3 (9%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 22 (17%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| More than 3 hours, but not unlimited | 51 (5%) | 5 (9%) | 5 (15%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 15 (14%) | 3 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (13%) | 4 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (0%) | 9 (9%) |

| Unlimited | 360 (36%) | 47 (85%) | 16 (47%) | 47 (96%) | 0 (0%) | 88 (81%) | 15 (44%) | 1 (3%) | 27 (87%) | 27 (21%) | 70 (96%) | 2 (1%) | 20 (21%) |

| Not at all | 199 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 45 (87%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 34 (26%) | 1 (1%) | 97 (34%) | 14 (15%) |

| Do you feel that the measures that were implemented due to coronavirus/COVID-19 (eg, restrictions by hospital management) made it more difficult for you to be present with your baby? | |||||||||||||

| n=990 | n=55 | n=34 | n=48 | n=51 | n=110 | n=34 | n=37 | n=31 | n=132 | n=74 | n=288 | n=96 | |

| Yes | 726 (73%) | 33 (60%) | 18 (53%) | 37 (77%) | 39 (76%) | 61 (55%) | 19 (56%) | 35 (95%) | 20 (65%) | 112 (85%) | 14 (19%) | 263 (91%) | 75 (78%) |

| No, not more difficult | 192 (19%) | 17 (31%) | 15 (44%) | 10 (21%) | 3 (6%) | 42 (38%) | 14 (41%) | 1 (3%) | 7 (23%) | 17 (13%) | 46 (62%) | 11 (4%) | 9 (9%) |

| No, there were no restrictive measures in place | 39 (4%) | 4 (7%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (4%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (10%) | 2 (2%) | 11 (15%) | 3 (1%) | 8 (8%) |

| Do not know | 33 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (18%) | 3 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (4%) | 11 (4%) | 4 (4%) |

| Do you feel that the measures that were implemented due to coronavirus/COVID-19 (eg, restrictions by hospital management) made it more difficult for you to be interactive with your baby (eg, skin-to-skin contact or being involved in the care of your baby)? | |||||||||||||

| n=989 | n=55 | n=34 | n=49 | n=51 | n=110 | n=34 | n=37 | n=31 | n=132 | n=74 | n=286 | n=96 | |

| Yes | 634 (64%) | 13 (24%) | 15 (44%) | 27 (55%) | 38 (75%) | 41 (37%) | 21 (62%) | 36 (97%) | 9 (29%) | 106 (80%) | 9 (12%) | 266 (93%) | 53 (55%) |

| No, not more difficult | 258 (26%) | 31 (56%) | 16 (47%) | 16 (33%) | 4 (8%) | 53 (48%) | 11 (32%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (42%) | 22 (17%) | 46 (62%) | 11 (4%) | 35 (36%) |

| No, there were no restrictive measures in place | 72 (7%) | 10 (18%) | 2 (6%) | 5 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (14%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 9 (29%) | 3 (2%) | 18 (24%) | 4 (1%) | 4 (4%) |

| Do not know | 25 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 9 (18%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (2%) | 4 (4%) |

| When was skin-to-skin contact with your baby and one of the parents initiated (eg, holding the baby on the chest, kangaroo mother care)? | |||||||||||||

| n=1044 | n=56 | n=33 | n=49 | n=52 | n=117 | n=35 | n=38 | n=31 | n=146 | n=75 | n=308 | n=104 | |

| Immediately after birth | 65 (6%) | 7 (13%) | 1 (3%) | 8 (16%) | 2 (4%) | 13 (11%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (16%) | 7 (5%) | 11 (15%) | 4 (1%) | 6 (6%) |

| On the first day | 99 (9%) | 14 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 43 (37%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (16%) | 4 (3%) | 19 (25%) | 4 (1%) | 2 (2%) |

| After the first day but during the first week | 236 (23%) | 23 (41%) | 8 (24%) | 21 (43%) | 0 (0%) | 45 (38%) | 8 (23%) | 3 (8%) | 14 (45%) | 36 (25%) | 35 (47%) | 17 (6%) | 26 (25%) |

| After the first week | 244 (23%) | 11 (20%) | 21 (64%) | 13 (27%) | 4 (8%) | 14 (12%) | 18 (51%) | 13 (34%) | 7 (23%) | 32 (22%) | 10 (13%) | 60 (19%) | 41 (39%) |

| Not so far (If still in hospital) | 156 (15%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 44 (85%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 19 (13%) | 0 (0%) | 72 (23%) | 13 (13%) |

| Not during the time in the hospital if discharged | 244 (23%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (1%) | 7 (20%) | 18 (47%) | 0 (0%) | 48 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 151 (49%) | 16 (15%) |

| How often were you permitted to have skin-to-skin contact (kangaroo mother care) with your baby? | |||||||||||||

| n=1043 | n=56 | n=32 | n=49 | n=52 | n=118 | n=34 | n=38 | n=31 | n=146 | n=75 | n=308 | n=104 | |

| As often as I wanted | 302 (29%) | 18 (32%) | 14 (44%) | 25 (51%) | 0 (0%) | 99 (84%) | 8 (24%) | 0 (0%) | 16 (52%) | 12 (8%) | 63 (84%) | 11 (4%) | 36 (35%) |

| At least once per day | 227 (22%) | 31 (55%) | 11 (34%) | 21 (43%) | 2 (4%) | 15 (13%) | 13 (38%) | 12 (32%) | 12 (39%) | 31 (21%) | 9 (12%) | 43 (14%) | 27 (26%) |

| At least once per week | 64 (6%) | 6 (11%) | 3 (9%) | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (9%) | 4 (11%) | 3 (10%) | 17 (12%) | 3 (4%) | 18 (6%) | 3 (3%) |

| Less than once per week | 77 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (12%) | 7 (18%) | 0 (0%) | 24 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 29 (9%) | 8 (8%) |

| Not so far | 373 (36%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 48 (92%) | 1 (1%) | 6 (18%) | 15 (39%) | 0 (0%) | 62 (42%) | 0 (0%) | 207 (67%) | 30 (29%) |

| Did medical/nursing staff involve you in the care of your baby (eg, nappy changing, feeding, temperature taking)? | |||||||||||||

| n=989 | n=55 | n=34 | n=49 | n=51 | n=110 | n=34 | n=37 | n=31 | n=131 | n=74 | n=287 | n=96 | |

| Yes, to a high degree | 438 (44%) | 44 (80%) | 15 (44%) | 34 (69%) | 4 (8%) | 102 (93%) | 22 (65%) | 6 (16%) | 27 (87%) | 48 (37%) | 67 (91%) | 22 (8%) | 47 (49%) |

| Yes, to some degree | 180 (18%) | 10 (18%) | 10 (29%) | 15 (31%) | 3 (6%) | 7 (6%) | 10 (29%) | 11 (30%) | 4 (13%) | 29 (22%) | 7 (9%) | 53 (18%) | 21 (22%) |

| No, not at all | 364 (37%) | 1 (2%) | 9 (26%) | 0 (0%) | 40 (78%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (6%) | 20 (54%) | 0 (0%) | 53 (40%) | 0 (0%) | 211 (74%) | 27 (28%) |

| Do not know | 7 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 1 (1%) |

| Did medical/nursing staff involve your partner in the care of your baby? | |||||||||||||

| n=990 | n=55 | n=34 | n=49 | n=51 | n=110 | n=34 | n=37 | n=31 | n=131 | n=74 | n=288 | n=96 | |

| Yes, to a high degree | 274 (28%) | 35 (64%) | 4 (12%) | 29 (59%) | 3 (6%) | 87 (79%) | 19 (56%) | 5 (14%) | 18 (58%) | 2 (2%) | 63 (85%) | 4 (1%) | 5 (5%) |

| Yes, to some degree | 121 (12%) | 18 (33%) | 9 (26%) | 14 (29%) | 4 (8%) | 15 (14%) | 8 (24%) | 6 (16%) | 6 (19%) | 10 (8%) | 7 (9%) | 18 (6%) | 6 (6%) |

| No, not at all | 567 (57%) | 1 (2%) | 19 (56%) | 6 (12%) | 39 (76%) | 6 (5%) | 6 (18%) | 24 (65%) | 5 (16%) | 114 (87%) | 3 (4%) | 263 (91%) | 81 (84%) |

| Do not know | 17 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 3 (3%) |

| I do not have a partner | 11 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

Blue: 95% CI: significantly higher than total (for detailed results, see online supplemental table S5.

Green: 95% CI: significantly lower than total (for detailed results, see online supplemental table S5.

Analysis showed country-specific differences regarding access of family members to the hospitalised infant: between 80% and more than 90% of participants from Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand and Sweden answered that both parents were allowed access. Lower proportions were observed for the remaining countries, with the lowest numbers in China, where 35% of the mothers and 29% of the fathers were permitted to be present with the newborn (table 2). More than half of the participants in Australia, China, France, New Zealand and Sweden indicated that more than one person was allowed to be present with the newborn at the same time (table 2).

Overall, 32% of the respondents could see their newborn all the time (24/7), and 13% multiple times per day (figure 1A). More than 20% were not allowed to see their newborn at any time, which was particularly observed in China (85%) and also reported by respondents from Mexico (14%), Poland (28%), Turkey (36%) and Ukraine (15%, figure 1A). While more than half of the respondents from Poland were provided with either photos, livestream options or recorded videos as alternative tools to being present, parents from Mexico (78%), Turkey (55%) and Ukraine (81%) were mostly not offered any alternatives (online supplemental table S4).

While in Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand and Sweden, more than 80% of the respondents had unlimited access to their newborn, other countries implemented duration restrictions (table 2). Significantly high proportions of being ‘not at all’ allowed to be present with the infant were noted in China (87%) and Turkey (34%) (online supplemental table S5). In Mexico, Turkey and Ukraine, more than half of the respondents indicated that they were allowed to see their baby for up to 1 hour. More than 70% of the respondents from Canada, China, Mexico, Poland, Turkey and Ukraine felt that the measures implemented due to COVID-19 made it more difficult for them to be present, and more than 70% from China, Mexico, Poland and Turkey to be interactive with their newborn, for example, regarding skin-to-skin contact (table 2).

The possibilities to have skin-to-skin contact with the infant differed between countries, with significantly high proportions of respondents in Mexico (47%) and Turkey (49%), indicating that skin-to-skin care was not initiated during the time in the hospital (online supplemental table S5). In China, most respondents (85%) answered that skin-to-skin care had not yet been initiated (if still in the hospital). In the remaining countries, skin-to-skin care was mainly initiated after the first day but during the first week with few exceptions having high answer rates with regards to an early initiation (immediately after birth or on the first day) such as France. In Sweden and France, >80% of the mothers were permitted to have skin-to-skin contact with their newborn as often as they wanted. While >95% of the respondents from Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, New Zealand and Sweden could touch their newborn in the incubator or bed as often as they wanted or at least once per day, 92% of the participants in China and 60% in Turkey were not permitted to do so (table 2).

The involvement in the care was perceived differently by parents across countries. While participants from Australia, France, New Zealand and Sweden felt that they were highly involved in the care by medical and nursing staff (>80%), more than 70% of participants in China, Poland, Turkey and Ukraine felt that staff did neither include them nor their partner in the care. In addition, while the majority of participants from Sweden (85%) responded that also their partner was highly involved by medical and nursing staff, this was not the case for participants in Turkey.

Nutrition and breast feeding

In total, 89% of the respondents answered that their newborns were fed with breastmilk (breast feeding or pumped milk), 22% received donor human milk and 34% were fed with infant formula (multiple response question; online supplemental table S6). Initiation of breast feeding was highly (50%) or somewhat (26%) encouraged by medical/nursing staff in most countries (online supplemental table S6). Overall, 18% indicated that breast feeding was not encouraged at all. This lack of encouragement was especially noted in Italy (32%), Poland and Turkey (>25%). However, newborns in Italy and Turkey were in over 90% of cases still exclusively or partly breastfed or provided with mother’s own pumped/expressed breastmilk in the first weeks after birth (online supplemental table S6).

Also, the initiation of breastfeeding differed across countries. In Canada, first breast feeding or provision of mother’s own pumped/expressed breastmilk took place on the first day (57%) or after the first day but during the first week (37%). Likewise, in Australia, France and New Zealand, >50% of the respondents indicated that breast feeding was initiated on the first day. In Mexico, 50% of the babies received first breastmilk after the first week. In Brazil, France, Italy and Ukraine, more than 20% of the babies were first breastfed after the first week (online supplemental table S6).

In most countries, the respondents were allowed to bring expressed milk from home to the unit (76%). In Brazil, the milk had to be expressed at the hospital (71%). In New Zealand, Poland, Sweden and Ukraine, more than 10% of the respondents indicated that they were not allowed to bring expressed milk from home to the unit.

Health information and communication

Almost 90% of the respondents felt that they had received adequate general health information about their newborn during the hospital stay either to a high or some degree (online supplemental table S7). Parents from Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Italy, New Zealand and Sweden indicated to a high degree of having received general health information (>50%). While 84% of the respondents from China indicated that they received general health information to a high or to some degree, 10% answered that they did not receive any information.

Almost 80% of the respondents received information about their newborn multiple times per day or once per day (online supplemental table S7). General health information was mostly communicated to the parents in face-to-face meetings with medical/nursing staff (76%) or via phone calls (50%).

Overall, more than 60% of the respondents from Italy felt to a high degree that they had received adequate information about how to protect themselves and their newborn from a COVID-19 transmission. In China, 50% felt that they knew how to prevent transmission. A similar result could be observed at discharge from the hospital: in Italy and China, where about 40% of the respondents indicated that they received adequate information about COVID-19 to a high degree. In Poland, almost 40% of the respondents felt that they had not received any information about COVID-19 when being discharged from the hospital (online supplemental table S7).

Parents’ mental health and support

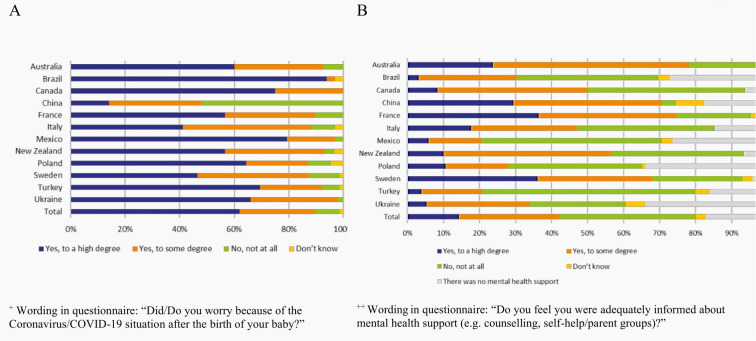

More than three-quarters of the respondents indicated being worried about the COVID-19 situation during pregnancy. For 9% of the respondents, COVID-19 was not an issue, and 10% did not worry about the virus at all. While most respondents from Mexico worried about COVID-19 during pregnancy to a high degree (71%), this was only the case for 18% of the respondents from China (figure 2A). After birth, 90% of the total respondents worried about the COVID-19 situation to a high or to some degree. Parents from Brazil worried to a high degree (94%), while more than half of the parents from China were not at all concerned (figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Country-specific proportions on (A) the concern about the COVID-19 situation and (B) mental health support.

Overall, 42% of the respondents felt that they were adequately informed about mental health support to a high or some degree (figure 2B). However, 38% felt that they were not at all informed, and in 17% of the cases, there was no mental health support. The results show that proportions of having received adequate information were highest in Australia and lowest in Turkey and Mexico. The absence of mental health support was highest in Ukraine and Poland (34%). If support was offered, most parents received psychological counselling (29%) and help from a social worker (19%). In total, 48% of the respondents answered that no support was offered (online supplemental table S8).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted healthcare systems and further challenged the already inadequate application of an IFCDC approach in many countries worldwide. Measures to stem virus transmission have resulted in (additional) restrictions affecting preterm, sick and low birth weight infants, one of the most vulnerable groups of patients.18 22 Highlighting the importance of IFCDC and by taking a patient/parent-centred approach, this study has identified parents’ perceptions to different policy measures across 12 countries, with severe implications for both IFCDC as well as the health outcomes of vulnerable infants born during the pandemic.28–30 In what follows, we will reflect on the key findings that emerged from our multicountry research, covering data from Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, Poland, Sweden, Turkey and Ukraine.

Perinatal care was impacted by the pandemic and respective restrictions, in particular, with regards to having support persons present during both pregnancy-related appointments and birth. Our findings have shown that while some countries have hardly restricted the presence of accompanying persons during birth (such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada and Sweden), in many other countries, it was not permitted to have a support person present (as, eg, in >60% in China, Ukraine, Turkey and >85% in Poland and Mexico). This restriction finally leaves the person giving birth without any emotional, informational and practical support from a person of trust. In contrast with such pandemic-related restrictions, previous research showed that having a support person present fulfilling these tasks facilitates non-pharmacological pain relief as well as bonding and improves maternal well-being,29 30 46 47 which clearly highlights the benefits as well as the importance of labour companionship. In its recommendations on ‘Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience’, the WHO advocates for a companion of choice for all women throughout labour and childbirth48 also during the pandemic.49 Thus, global health agendas do no longer exclusively focus on the reduction of birth complications, yet they have expanded their scope and have started to emphasise the importance of maternal and newborn health and well-being and that mother and child should also thrive and enjoy their full potential of health.33 Partners should, therefore, be allowed access to enable a respectful childbirth experience, yet this opportunity is too often being withheld as our research showed.

This study also revealed shortcomings regarding presence and involvement of family members while the newborn needed special/intensive care, which confirms results of similar studies.14 22 24 33 50 As we have learnt from our findings,18 restrictions were implemented and, besides some exceptions (eg, in Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand and Sweden), in 7 out of 12 countries, partly only the mother was allowed to be present with the newborn. The other parent, however, was less likely to have access with strict access restrictions, for example, in Poland and Ukraine, and siblings as well as other family members were hardly ever allowed in the NICU in any country. Most importantly, our results showed that there are countries (eg, Turkey and China) where nobody (not even father or mother) was allowed to be with the hospitalised infant. Thus, extremely strict access measures following a severe separation policy between parents and their vulnerable infant were implemented. Parental-infant bonding, however, can only take place if the parents are present and given the opportunity to care for their newborn.34 51–53 Not including parents in caring, planning and participation in decision-making processes pertaining to their newborn will less likely establish feelings of competency and a healthy parent–child relationship.51 Research shows that if the parents feel empowered to care for the child, maternal stress and anxiety can be reduced and hospital stays may be shorter.54 55 Despite this, involving parents and seeing them as primary caregivers also depend on the mind set of healthcare professionals.16

Separating family members, and, in particular, parents from their newborns has severe consequences for the care provision and health outcomes of the vulnerable infant, for example, due to limited possibilities for skin-to-skin care and KMC.22 53 For almost one quarter of the total respondents, skin-to-skin contact with the newborn was not initiated during the time in the hospital, with particular strict measures in Mexico and Turkey, even though the benefits of practices such as KMC are undisputed.16 17 56–59 The positive influence on developmental outcomes far outweighs the potential risk of death due to COVID-19 as research highlights.31 Survival benefits of immediate KMC seem to be higher compared with those of conventional care in an incubator or a radiant warmer, as a recent randomised control trial conducted in low-resource hospital shows,59 making further research also in well-resourced settings necessary. These findings highlight that newborns should not be separated from their parents; our study unfortunately shows that the separation of parents and their newborn is (still) common practice as a minimum during the pandemic.

Even though a large majority of parents felt adequately informed about their newborn, almost 40% of the total respondents were not involved at all in the care of their baby (eg, nappy changing, feeding, temperature taking) and almost 60% indicated that their partner was not involved in caring for the newborn, leaving them without any practice when the infant was discharged. Strong country-specific differences show that the involvement of the parents was encouraged more in Australia, Canada, France, Italy, New Zealand and Sweden in comparison to China, Poland, Turkey and Ukraine. Moreover, the implemented measures during COVID-19 made parental presence and interaction with the baby more difficult for parents in Mexico, Poland and Turkey than in Australia, France, New Zealand and Sweden. Although we could observe considerable country-specific differences on specific elements of IFCDC, overall, some countries such as New Zealand and Sweden performed uniformly well, while other countries fell behind. These differences could be partly explained by the government response stringency indexes between August and November 2020 (lowest in New Zealand; highest in China; online supplemental table S2).43 The differences can also be interpreted as a prioritisation of a holistic IFCDC approach in some countries, which might have already put a greater focus on this care approach in the prepandemic phase compared with others, for example, China.20 However, comprehensive data on the national and international implementation of the different aspects of IFCDC are lacking60 and, thus, the results need to be interpreted with caution.

In contrast to parental presence and skin-to-skin contact, breast feeding does not seem to have been impacted to the same degree. Despite various implemented restrictions, our data did not suggest that the ability to breastfeed or breast feeding in general was discouraged by nursing staff across the 12 countries. Although about 30% of the parents from Italy and Mexico indicated that breast feeding was not encouraged at all by nursing staff—against the current WHO recommendation61—this did not influence the number of infants being breastfed or provided with mother’s own pumped or expressed breastmilk at least in the first weeks after birth (>90%). It has been outlined that globally, breast feeding has not been prioritised and encouraged during the pandemic, for example, due to early discharge and limited lactation support, with possible negative implications for its initiation.32 62 63 Our data, however, imply that breast feeding, as one element of IFCDC, was somewhat less affected by the restrictions, at least in the hospital. However, this study does not show the long-term trend and potential continuation of breast feeding, for example, also in case of early discharge, which frequently occurred during the pandemic.21

Having a newborn requiring special/intensive care is in itself a stressful situation for parents, and even more so during a pandemic. Preterm birth can be associated with a number of adverse maternal psychological outcomes, among others, anxiety and psychological distress.64 65 The COVID-19 pandemic, as an additional contributing factor to emotional distress and with an increased risk for psychiatric illness66 and postnatal depression,67 makes parents of a preterm, sick or low birth weight infant increasingly vulnerable to developing mental health issues. Our results show that the COVID-19 situation was especially worrisome for parents in Brazil, Canada and Mexico after the birth of their baby. These results do not seem to be related to the cumulative COVID-19 cases or the government response stringency index in the respective countries (online supplemental table S2). At the same time, parents from Brazil, Canada and Mexico, together with those from Turkey, did not feel well informed about mental health and support. Early intervention is, however, important, and mental health support should be offered as early as possible and already during the hospital stay.64 In an emergency situation, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the focus on health and early supportive measures should be even more pronounced.

This study has several strengths that merit attention, and contextual factors that need to be outlined. The cross-country approach, data collection in 12 countries and extensive outreach allowed us to acquire valuable and in-depth insights into parents’ perspectives and experiences regarding IFCDC during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Pretesting of the questionnaire reduced methodological inaccuracies and ensured that data were collected in a sensitive way. The findings comprehensively reflect the parent perspective across multiple countries giving insights into country-specific differences, which are worthwhile to derive suggestions for improvements on the global and country-specific policy level.

The study has limitations that need to be acknowledged. Due to limited access and outreach possibilities in our network, we were not able to collect a representative set of data in particularly African and Southeast-Asian countries. In many countries in these regions, parent representative organisations do either not exist or do not have a strong lobby, which is in itself an important finding and worthwhile to investigate further. Setting up the study in an online format furthermore bears the risk of selection bias,68 and response rates could not be calculated as information on non-responders, in particular, during the pandemic state is not available. Due to missing demographics on neonates receiving special/intensive care in the different countries, we were unable to assess the representativeness of the sample. We, furthermore, acknowledge the high c-section rate in the sample, which, however, must be put in context as we study a high-risk population requiring admission of the infant to the NICU or special care unit (inclusion criteria). We are aware that participants completed the survey at different care stages (ie, during/after hospitalisation) with a potential impact on the parents’ perceived experiences. It also needs to be acknowledged that different countries, cultures, settings, income levels, political and healthcare systems as well as the individual countries’ contribution to the full sample comprise a potential risk of confounding bias. The reported overall percentages are influenced by the number of responses per country (countries with more responses influence the total more) and could not be weighed in another meaningful way. Thereby, country comparison with overall percentages needs to be interpreted with caution. Moreover, the calculation of confidence intervals has limitations as only one answer option per question was selected for further analysis to aid readability.

The study reflects a point in time and we are unable to compare our findings to prepandemic contexts. We acknowledge that strong variation has already existed between and within countries in the field of newborn care, in particular, regarding IFCDC implementation,60 which is not exclusively related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the respective pandemic situation, geographical, climatic and environmental aspects as well as containment strategies vary between (and sometimes even within) countries and might have influenced on the one hand, the COVID-19-related policy approach and on the other hand, the results in the respective countries.43 69 This has to be acknowledged when comparing results between countries and interpreting potential implications of the COVID-19 incidence on IFCDC on a country level.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first multicountry comparison of parents’ experiences regarding special/intensive care for newborns during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic on a country level. The pandemic has challenged healthcare systems, leading to disruptions in the care of the most vulnerable groups of patients, namely, preterm, sick and low birth weight infants. Pandemic-related restrictions are certainly necessary to prevent and reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2. However, restrictions in parental presence and the missing possibility for skin-to-skin contact, together with lacking mental health support, are global health drawbacks, threatening newborn survival, quality of life of survivors and their families and hinder the achievement of the 2030 Development Agenda. This study provides unique opportunities for public health experts, policymakers and healthcare professionals alike to learn from country-specific differences and in-depth insights and consequences from different approaches. It is essential to listen to and acknowledge parents’ voices and experiences. Immediate action is necessary, including the reconsideration of implemented restrictions to strengthen an IFCDC approach, both during and in the absence of a global crisis.70 71 This action requires a set of measures, including a safe and supportive care environment during and after pregnancy, labour and birth and the implementation of a zero separation and family-inclusive policy in hospitals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all study respondents and very much appreciate their time and invaluable commitment. We also thank all representatives of national parent organisations and experts, who have supported translation and dissemination of the survey.

Footnotes

Collaborators: COVID-19 Zero Separation Collaborative Group (in alphabetical order): Mandy Daly (NIDCAP, USA and Irish Neonatal Health Alliance, Ireland), Camilla Gizzi (UENPS, Department of Pediatrics—Sandro Pertini Hospital, Rome, Italy), Agnes van den Hoogen (ESPR, Geneva, Switzerland, COINN, Utrecht University and UMC Utrecht, The Netherlands), Gigi Khonyongwa-Fernandez (NICU Parent Network (NPN), USA), Mary Kinney (University of the Western Cape, South Africa), Kerstin Mondry (European Foundation for the Care of Newborn Infants (EFCNI), Munich, Germany), Corrado Moretti (UENPS, Emeritus Consultant in Paediatrics, Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy), Ilknur Okay (El Bebek Gül Bebek Derneği, Turkey), Kylie Pussell (Miracle Babies Foundation, Australia), Charles C. Roehr (ESPR, Geneva, Switzerland, and National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, UK), Eleni Vavouraki (Ilitominon, Greece), Karen Walker (COINN, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, University of Sydney, Australia).

Contributors: The EFCNI scientific team conceptualised the study and set up the online survey under the lead of JK and with critical feedback by LJIZ, SM and the members of the COVID-19 Zero Separation Collaborative Group. The COVID-19 Zero Separation Collaborative Group substantially supported the recruitment of respondents. CvR-P and JH were responsible for the statistical analysis, with feedback by JK, AW and LJIZ. JK, CvR-P and JH drafted the manuscript, which was shared with and continuously reviewed by AW, SM and LJIZ. JK, JH, CvR-P, AW, LJIZ and SM interpreted and had full access to the data. All authors critically revised and have read and approved the final manuscript. JK acts as the guarantor for this study.

Funding: During the conduct of this project, EFCNI was supported by Novartis Pharma AG with an earmarked donation for this study (grant award number: not applicable/ NA). The research was independently conducted by the authors of this paper. The donor had no role in any step of the research project.

Map disclaimer: The inclusion of any map (including the depiction of any boundaries therein), or of any geographic or locational reference, does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. Any such expression remains solely that of the relevant source and is not endorsed by BMJ. Maps are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: The authors report an earmarked donation from Novartis Pharma AG during the conduct of the study.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

the COVID-19 Zero Separation Collaborative Group:

Agnes vanden Hoogen, Camilla Gizzi, Charles C Roehr, Corrado Moretti, Eleni Vavouraki, Gigi Khonyongwa-Fernandez, Ilknur Okay, Karen Walker, Kerstin Mondry, Kylie Pussell, Mandy Daly, and Mary Kinney

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Deidentified participant data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request (S.MaderOffice@efcni.org).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Data collection, processing and storage conformed to the General Data Protection Regulation and the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was given by ticking a confirmation box. For those who declined to participate, the web interface was terminated. Respondents were informed that some of the questions might cause distressing reactions in view of their personal experiences, and they had the opportunity to stop participation at any time. No financial or other incentives were offered to the participants. The Ethics Committee of Maastricht UMC+, the Netherlands, has waived the need for ethical approval for this study (MECT 2020–1336).

References

- 1. United Nations Statistics Division . Goal 3: ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages, 2021. Available: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2017/goal-03/

- 2. Coll-Seck A, Clark H, Bahl R, et al. Framing an agenda for children thriving in the SDG era: a WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission on child health and wellbeing. The Lancet 2019;393:109–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32821-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Semaan A, Audet C, Huysmans E, et al. Voices from the frontline: findings from a thematic analysis of a rapid online global survey of maternal and newborn health professionals facing the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002967. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shapira G, Ahmed T, Drouard SHP, et al. Disruptions in maternal and child health service utilization during COVID-19: analysis from eight sub-Saharan African countries. Health Policy Plan 2021;36:1140–51. 10.1093/heapol/czab064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shapira G, de Walque D, Friedman J. How many infants may have died in low-income and middle-income countries in 2020 due to the economic contraction accompanying the COVID-19 pandemic? mortality projections based on forecasted declines in economic growth. BMJ Open 2021;11:e050551. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the sustainable development goals. The Lancet 2016;388:3027–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31593-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Althabe F, Howson CP, et al. , World Health Organization . Born too soon: the global action report on preterm birth, 2012. Available: http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/news/2012/201204%5Fborntoosoon-report.pdf

- 8. WHO . Causes of newborn mortality and morbidity in the European region. Available: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/Life-stages/maternal-and-newborn-health/causes-of-newborn-mortality-and-morbidity-in-the-european-region

- 9. Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller A-B, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e37–46. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30451-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lehtonen L, Gimeno A, Parra-Llorca A, et al. Early neonatal death: a challenge worldwide. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2017;22:153–60. 10.1016/j.siny.2017.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Each European association for children in hospital. The each charter with annotations. EACH 2016. www.each-for-sick-children.org [Google Scholar]

- 12. UN Commission on Human Rights . Convention on the rights of the child, E/CN.4/RES/1990/74 General Assembly; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 13. McAdams RM. Family separation during COVID-19. Pediatr Res 2021;89:1317–8. 10.1038/s41390-020-1066-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bembich S, Tripani A, Mastromarino S. Parents experiencing NICU visit restrictions due to COVID‐19 pandemic. Acta Paediatr 2020;15620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Muniraman H, Ali M, Cawley P, et al. Parental perceptions of the impact of neonatal unit visitation policies during COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Paediatr Open 2020;4:e000899. 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oude Maatman SM, Bohlin K, Lilliesköld S, et al. Factors influencing implementation of Family-Centered care in a neonatal intensive care unit. Front Pediatr 2020;8:222. 10.3389/fped.2020.00222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ding X, Zhu L, Zhang R, et al. Effects of family-centred care interventions on preterm infants and parents in neonatal intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Aust Crit Care 2019;32:63–75. 10.1016/j.aucc.2018.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kostenzer J, Hoffmann J, von Rosenstiel-Pulver C, et al. Neonatal care during the COVID-19 pandemic - a global survey of parents' experiences regarding infant and family-centred developmental care. EClinicalMedicine 2021;39:101056. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stefani G, Skopec M, Battersby C, et al. Why is kangaroo mother care not yet scaled in the UK? A systematic review and realist synthesis of a frugal innovation for newborn care. BMJ Innov 2021:bmjinnov-2021-000828. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yue J, Liu J, Williams S, et al. Barriers and facilitators of kangaroo mother care adoption in five Chinese hospitals: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1234. 10.1186/s12889-020-09337-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rao SPN, Minckas N, Medvedev MM, et al. Small and sick newborn care during the COVID-19 pandemic: global survey and thematic analysis of healthcare providers' voices and experiences. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e004347. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Litmanovitz I, Silberstein D, Butler S, et al. Care of hospitalized infants and their families during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international survey. J Perinatol 2021;41:981–7. 10.1038/s41372-021-00960-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harding C, Aloysius A, Bell N, et al. Reflections on COVID -19 and the potential impact on preterm infant feeding and speech, language and communication development. Journal of Neonatal Nursing 2021;27:220–2. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Green J, Staff L, Bromley P, et al. The implications of face masks for babies and families during the COVID-19 pandemic: a discussion paper. J Neonatal Nurs 2021;27:21–5. 10.1016/j.jnn.2020.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bergman NJ, Westrup B, Westrup B, European Foundation for the Care of Newborn Infants . European standards of care for newborn health: project report. EFCNI 2018. www.efcni.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/2018_11_16_ESCNH_Report_final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mushtaq A, Kazi F. Family-centred care in the NICU. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 2019;3:295–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Damhuis G, König K, Westrup B, et al. European standards of care for newborn health: Infant- and family-centred developmental care. European foundation for the care of newborn infants (EFCNI), 2018. Available: https://newborn-health-standards.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/TEG_IFCDC_complete.pdf

- 28. Scala M, Marchman VA, Brignoni-Pérez E. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on developmental care practices for infants born preterm. Pediatrics 2020. http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Darcey-Mahoney A, White RD, Velasquez A. Impact of restrictions on parental presence in neonatal intensive care units related to COVID-19. Pediatrics 2020. http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Salvatore CM, Han J-Y, Acker KP, et al. Neonatal management and outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: an observation cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020;4:721–7. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30235-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Minckas N, Medvedev MM, Adejuyigbe EA, et al. Preterm care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparative risk analysis of neonatal deaths averted by kangaroo mother care versus mortality due to SARS-CoV-2 infection. EClinicalMedicine 2021;33:100733. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brown A, Shenker N. Experiences of breastfeeding during COVID‐19: lessons for future practical and emotional support. Matern Child Nutr 2021;17 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van Veenendaal NR, Deierl A, Bacchini F. The International Steering Committee for family integrated care. supporting parents as essential care partners in neonatal units during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. Acta Paediatrica 2021;15857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. BLISS for babies born premature or sick . Locked out: the impact of COVID-19 on neonatal care, 2021. Available: https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/files.bliss.org.uk/images/Locked-out-the-impact-of-COVID-19-on-neonatal-care-final.pdf?mtime=20210519184749&focal=none

- 35. Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of Internet E-Surveys (cherries). J Med Internet Res 2004;6:e34. 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. World Health Organization . WHO COVID-19 Dashboard. Geneva, 2020. Available: https://covid19.who.int

- 37. World Health Organization . COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update - 29 November 2020. WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-1-december-2020 [Accessed cited 2021 Jun 28].

- 38. Yan B, Zhang X, Wu L, et al. Why do countries respond differently to COVID-19? A comparative study of Sweden, China, France, and Japan. The American Review of Public Administration 2020;50:762–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Claeson M, Hanson S. COVID-19 and the Swedish enigma. Lancet 2021;397:259–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32750-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Baral S, Chandler R, Prieto RG, et al. Leveraging epidemiological principles to evaluate Sweden's COVID-19 response. Ann Epidemiol 2021;54:21–6. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Amer F, Hammoud S, Farran B, et al. Assessment of Countries’ Preparedness and Lockdown Effectiveness in Fighting COVID-19. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2021;15:e15–22. 10.1017/dmp.2020.217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Garcia PJ, Alarcón A, Bayer A, et al. COVID-19 response in Latin America. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2020;103:1765–72. 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hale T, Angrist N, Goldszmidt R, et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 government response Tracker). Nat Hum Behav 2021;5:529–38. 10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. World Health Organization . Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: estimates by who, UNICEF, UNFPA, world bank group and the United nations population division. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/327595 [Google Scholar]

- 45. UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation . Most recent stillbirth, child and adolescent mortality estimates, 2019. Available: https://childmortality.org/ [Accessed 26 Nov 2021].

- 46. ed Bohren MA, Berger BO, Munthe-Kaas H, Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group . Perceptions and experiences of labour companionship: a qualitative evidence synthesis.. In: Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 2019. http://doi.wiley.com/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shakibazadeh E, Namadian M, Bohren M, et al. Respectful care during childbirth in health facilities globally: a qualitative evidence synthesis. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy 2018;125:932–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. WHO . WHO recommendations Intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience - Transforming care of women and babies for improved health and well-being. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): pregnancy and childbirth, 2020. Available: www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-pregnancy-and-childbirth [Accessed 02 Aug 2021].

- 50. Cena L, Biban P, Janos J, et al. The collateral impact of COVID-19 emergency on neonatal intensive care units and Family-Centered care: challenges and opportunities. Front Psychol 2021;12:630594. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.630594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Boronat N, Escarti A, Vento M. We want our families in the NICU! Pediatr Res 2020;88:354–5. 10.1038/s41390-020-1000-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gooding JS, Cooper LG, Blaine AI, et al. Family support and family-centered care in the neonatal intensive care unit: origins, advances, impact. Semin Perinatol 2011;35:20–8. 10.1053/j.semperi.2010.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bergman NJ. Birth practices: Maternal-neonate separation as a source of toxic stress. Birth Defects Res 2019;111:1087–109. 10.1002/bdr2.1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sáenz P, Cerdá M, Díaz JL, et al. Psychological stress of parents of preterm infants enrolled in an early discharge programme from the neonatal intensive care unit: a prospective randomised trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2009;94:F98–104. 10.1136/adc.2007.135921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ortenstrand A, Westrup B, Broström EB, et al. The Stockholm neonatal family centered care study: effects on length of stay and infant morbidity. Pediatrics 2010;125:e278–85. 10.1542/peds.2009-1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lv B, Gao X-R, Sun J, et al. Family-Centered care improves clinical outcomes of very-low-birth-weight infants: a quasi-experimental study. Front Pediatr 2019;7:138. 10.3389/fped.2019.00138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Bahl R, et al. Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? Lancet 2014;384:347–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60792-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mazumder S, Taneja S, Dube B, et al. Effect of community-initiated kangaroo mother care on survival of infants with low birthweight: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019;394:1724–36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32223-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. WHO Immediate KMC Study Group, Arya S, Naburi H, et al. Immediate "Kangaroo Mother Care" and Survival of Infants with Low Birth Weight. N Engl J Med 2021;384:2028–38. 10.1056/NEJMoa2026486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Al-Motlaq MA, Carter B, Neill S, et al. Toward developing consensus on family-centred care: an international descriptive study and discussion. J Child Health Care 2019;23:458–67. 10.1177/1367493518795341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. WHO . Breastfeeding and COVID-19, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Breastfeeding-2020.1 [Accessed 09 Jun 2021].

- 62. Spatz DL, Davanzo R, Müller JA, et al. Promoting and protecting human milk and breastfeeding in a COVID-19 world. Front Pediatr 2020;8:633700. 10.3389/fped.2020.633700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rollins N, Minckas N, Jehan F, et al. A public health approach for deciding policy on infant feeding and mother-infant contact in the context of COVID-19. Lancet Glob Health 2021;9:e552–7. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30538-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Misund AR, Nerdrum P, Diseth TH. Mental health in women experiencing preterm birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:263. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Simon S, Moreyra A, Wharton E, et al. Prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder in mothers of preterm infants using trauma-focused group therapy: manual development and evaluation. Early Hum Dev 2021;154:105282. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020;383:510–2. 10.1056/NEJMp2008017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Townsend R, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2021;9:e759–72. 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00079-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Blumenberg C, Barros AJD. Response rate differences between web and alternative data collection methods for public health research: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Public Health 2018;63:765–73. 10.1007/s00038-018-1108-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Murgante B, Borruso G, Balletto G, et al. Why Italy first? health, geographical and planning aspects of the COVID-19 outbreak. Sustainability 2020;12:5064. [Google Scholar]

- 70. EFCNI KJ, von Rosenstiel-Pulver C, Hoffmann J, et al. Zero separation. Together for better care! Infant and family-centred developmental care in times of COVID-19 – A global survey of parents’ experiences Project Report. EFCNI 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kostenzer J, Zimmermann LJI, Mader S, et al. Zero separation: infant and family-centred developmental care in times of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2022;6:7–8. 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00340-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-056856supp001.pdf (5.3MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Deidentified participant data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request (S.MaderOffice@efcni.org).