Key Points

Question

In critically ill children clinically assessed to require noninvasive respiratory support following extubation, is the first-line use of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) therapy noninferior to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in terms of time to liberation from all forms of respiratory support?

Findings

In this randomized, noninferiority trial of 600 children clinically assessed to require noninvasive respiratory support following extubation, the median time to liberation was 50.5 hours for HFNC vs 42.9 hours for CPAP. The 1-sided 97.5% confidence limit for the hazard ratio was 0.70, which failed to meet the noninferiority margin of 0.75.

Meaning

Among critically ill children requiring noninvasive respiratory support following extubation, HFNC compared with CPAP following extubation failed to meet the criterion for noninferiority for time to liberation from respiratory support.

Abstract

Importance

The optimal first-line mode of noninvasive respiratory support following extubation of critically ill children is not known.

Objective

To evaluate the noninferiority of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) therapy as the first-line mode of noninvasive respiratory support following extubation, compared with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), on time to liberation from respiratory support.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a pragmatic, multicenter, randomized, noninferiority trial conducted at 22 pediatric intensive care units in the United Kingdom. Six hundred children aged 0 to 15 years clinically assessed to require noninvasive respiratory support within 72 hours of extubation were recruited between August 8, 2019, and May 18, 2020, with last follow-up completed on November 22, 2020.

Interventions

Patients were randomized 1:1 to start either HFNC at a flow rate based on patient weight (n = 299) or CPAP of 7 to 8 cm H2O (n = 301).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was time from randomization to liberation from respiratory support, defined as the start of a 48-hour period during which the child was free from all forms of respiratory support (invasive or noninvasive), assessed against a noninferiority margin of an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of 0.75. There were 6 secondary outcomes, including mortality at day 180 and reintubation within 48 hours.

Results

Of the 600 children who were randomized, 553 children (HFNC, 281; CPAP, 272) were included in the primary analysis (median age, 3 months; 241 girls [44%]). HFNC failed to meet noninferiority, with a median time to liberation of 50.5 hours (95% CI, 43.0-67.9) vs 42.9 hours (95% CI, 30.5-48.2) for CPAP (adjusted HR, 0.83; 1-sided 97.5% CI, 0.70-∞). Similar results were seen across prespecified subgroups. Of the 6 prespecified secondary outcomes, 5 showed no significant difference, including the rate of reintubation within 48 hours (13.3% for HFNC vs 11.5 % for CPAP). Mortality at day 180 was significantly higher for HFNC (5.6% vs 2.4% for CPAP; adjusted odds ratio, 3.07 [95% CI, 1.1-8.8]). The most common adverse events were abdominal distension (HFNC: 8/281 [2.8%] vs CPAP: 7/272 [2.6%]) and nasal/facial trauma (HFNC: 14/281 [5.0%] vs CPAP: 15/272 [5.5%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among critically ill children requiring noninvasive respiratory support following extubation, HFNC compared with CPAP following extubation failed to meet the criterion for noninferiority for time to liberation from respiratory support.

Trial Registration

isrctn.org Identifier: ISRCTN60048867

This clinical trial evaluates the noninferiority of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) therapy vs continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) as the first-line mode of noninvasive respiratory support following extubation on time to liberation from respiratory support.

Introduction

Between 2017 and 2019, approximately 13 000 children, representing 65% of children admitted to pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) in the UK, received invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) annually.1 Because prolonged IMV has significant risks,2 noninvasive respiratory support is commonly used following extubation until children can breathe without assistance.3 Optimizing the first-line choice of postextubation respiratory support should reduce extubation failures and the overall duration of invasive and noninvasive respiratory support.4

Postextubation respiratory support has been traditionally provided in the PICU setting using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).5 Recently, high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) therapy has become a popular alternative due to ease of use, perceived greater patient comfort, and the ability to discharge children to general wards while receiving HFNC.6 An international survey of 1031 PICU clinicians from 40 countries showed that HFNC is commonly used following extubation,7 and in observational studies, between 5% and 86% of children started treatment with HFNC following extubation.8,9 Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) in adults and premature newborns have not demonstrated the greater effectiveness of HFNC over CPAP following extubation.10,11,12 To our knowledge, there are no RCTs regarding the optimal first-line mode of postextubation respiratory support in critically ill children.13

Following a pilot RCT to confirm feasibility for the definitive trial,14 First-Line Support for Assistance in Breathing in Children (FIRST-ABC) was designed as a master protocol of 2 pragmatic RCTs (step-up and step-down), with shared infrastructure and integrated health economic evaluation, to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of HFNC vs CPAP.15 This article reports the results of the step-down RCT, which tested the hypothesis that the first-line use of HFNC was noninferior to CPAP in terms of time to liberation from respiratory support in children following extubation. A noninferiority trial was conducted in view of the greater tolerability and patient comfort associated with HFNC.

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

The FIRST-ABC step-down RCT was a pragmatic, unblinded, multicenter, parallel-group, noninferiority trial.16 The master protocol was approved by East of England–Cambridge South Research Ethics Committee and the UK Health Research Authority, and was published prior to completion of trial recruitment.15 The trial protocol and the statistical analysis plan appear in Supplement 1. Cost-effectiveness findings are not reported in this article.

Trial information leaflets and posters were available to parents or legal guardians while their child was receiving IMV. Because the decision to commence postextubation respiratory support was often made urgently, and both noninvasive respiratory support modes were already widely used, a research without prior consent model was approved: written informed consent was sought from parents or legal guardians as soon as possible and appropriate following randomization.17,18 Data collected up to refusal/withdrawal of consent were retained unless parents or legal guardians requested otherwise.

The UK National Institute for Health Research funded the trial and convened an independently chaired (and majority-independent) trial steering committee and data monitoring and ethics committee. An interim analysis was planned when 300 patients reached 60-day follow-up19; however, by this time point, due to faster than anticipated recruitment, 560 patients had already been randomized out of a target of 600 patients. Therefore, the data monitoring and ethics committee deemed the interim analysis redundant; however, safety data were reviewed. The trial was managed by the Clinical Trials Unit at the UK Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre.

Sites and Participants

The trial was conducted at 22 National Health Service (NHS) general (medical-surgical), cardiac, and mixed (general/cardiac) PICUs across England, Wales, and Scotland. Children aged from birth (>36 weeks’ corrected gestational age) up to 15 years and admitted to participating PICUs were eligible if assessed by the treating clinician to require noninvasive respiratory support within 72 hours of extubation. Main exclusion criteria were clinical decision to start a mode other than CPAP or HFNC (eg, noninvasive ventilation) and preadmission receipt of domiciliary respiratory support (eMethods in Supplement 2).

Randomization

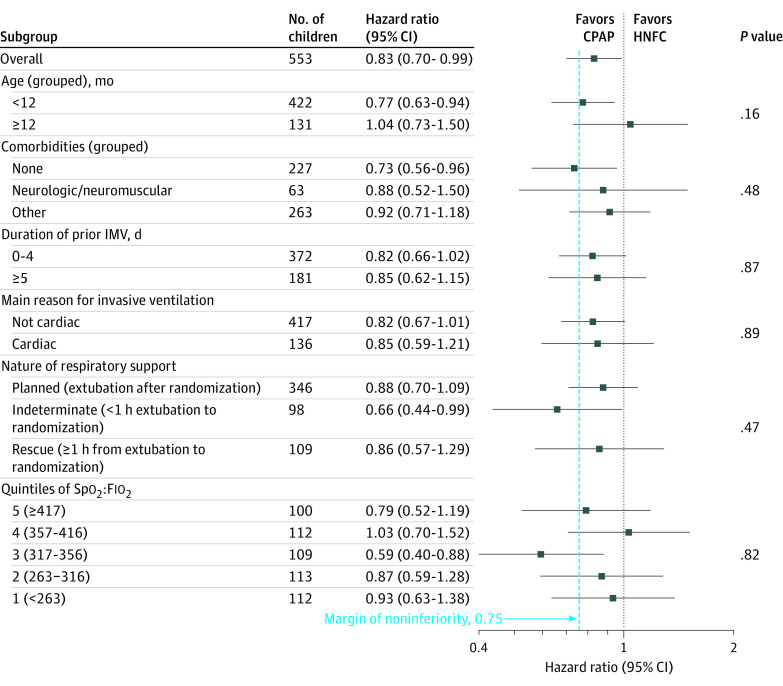

Randomization was conducted using a concealed centralized telephone/web-based system based on a computer-generated randomization sequence and was stratified by site and age (<12 months vs ≥12 months) using permuted block sizes of 2 and 4. Children were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to HFNC or CPAP as close to commencement of noninvasive respiratory support as possible (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Screening, Randomization, and Follow-up in the FIRST-ABC Step-Down Trial.

CPAP indicates continuous positive airway pressure; FIRST-ABC, First-Line Support for Assistance in Breathing in Children; HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; and NRS, noninvasive respiratory support.

aNumbers meeting individual exclusion criteria do not add to the total because some patients met more than 1 criterion.

Trial Interventions

The timing of extubation and nature of noninvasive respiratory support (planned prior to extubation or rescue after extubation) was at the clinical team’s discretion and not based on knowledge of the randomized treatment. Trial algorithms, developed following consultation with sites and finalized at a collaborators’ meeting, specified clinical criteria for the initiation, maintenance, and weaning from HFNC and CPAP (eFigures 1 and 2 in Supplement 2). Children randomized to HFNC were started at a gas flow rate based on body weight (<12 kg: 2 L/kg/min; ≥12 kg: see eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). When the child was deemed ready for weaning, the flow rate was reduced by 50%. Children randomized to CPAP were started at a pressure of 7 to 8 cm H2O. When the child was deemed ready for weaning, the pressure was reduced to 5 cm H2O. Both CPAP and HFNC were delivered through approved devices and interfaces already in use at sites. For both groups, the fraction of inspired oxygen (Fio2) was titrated to maintain peripheral oxygen saturations (Spo2) of 92% or greater.

To reflect clinical practice, and akin to previous RCTs,20,21,22 if prespecified treatment failure criteria were met (Fio2 ≥0.60, severe respiratory distress, patient discomfort, other), clinicians were permitted to switch from HFNC to CPAP (or vice versa) or escalate to other modes of noninvasive respiratory support or IMV. Because it was not possible to blind caregivers to trial interventions, bias was minimized by specifying the same number of weaning steps and weaning criteria for HFNC and CPAP, minimum twice-daily clinical evaluation to assess progression through the trial algorithm, and use of an online training package to strengthen protocol adherence. Management of patients receiving ventilation was already standardized at sites following the SandWiCH trial on protocolized IMV weaning.23

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome was time from randomization to liberation from respiratory support, defined as the start of the 48-hour period where the child was free from all respiratory support (invasive or noninvasive), excluding supplemental oxygen.

Secondary outcomes were mortality at PICU discharge, day 60, and day 180; rate of reintubation at 48 hours; duration of PICU and acute hospital stay; patient comfort, assessed using the COMFORT Behavior (COMFORT-B) scale24; sedation use during noninvasive respiratory support; and parental stress, measured using the Parental Stressor Scale: PICU (PSS:PICU) at or around time of consent.25 Adverse events were monitored and recorded up to 48 hours after liberation from respiratory support. The data collection schedule is shown in eTable 1 (Supplement 2).

Sample Size Calculation

It was estimated that 508 observed events would achieve 90% power with a 1-sided type I error rate of 2.5% to exclude the prespecified noninferiority margin of hazard ratio (HR) of 0.75. In the pilot RCT, an HR of 0.75 corresponded to approximately a median 16-hour increase in time to liberation for HFNC.14 Clinical members and the parent representative on the trial team agreed this was the maximum clinically acceptable difference between HFNC and CPAP. To account for censoring from death or transfer and refusal or withdrawal of consent and to retain sufficient power for a per-protocol analysis, the target sample size was set at 600 patients.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses of the primary and secondary outcomes were performed according to randomization group in all consented patients who commenced any respiratory support, invasive or noninvasive, following randomization (primary analysis set), and in all consented patients who met the eligibility criteria and commenced the randomized treatment (per-protocol analysis). Agreement of results from both analyses was required to conclude noninferiority.26 Analyses followed a prespecified statistical analysis plan published before trial recruitment was completed.19

The primary analysis was performed using Cox regression to calculate an HR with 1-sided 97.5% CIs, adjusted for prespecified baseline covariates: age (<12 months vs ≥12 months); Spo2:Fio2 ratio; comorbidities (none vs neurologic/neuromuscular vs other); length of prior IMV (<5 days vs ≥5 days); reason for IMV (cardiac vs other); severity of respiratory distress (severe vs mild/moderate), and site (treated as a random factor, using shared frailty). Patients were censored either at time of last known respiratory support (for those who withdrew consent or were discharged while still receiving respiratory support) or at time of death (if death occurred prior to liberation from respiratory support). The level of missingness of baseline covariates was assessed and if necessary missing values were replaced using multivariable imputation using chained equations. The assumption of proportional hazards was assessed visually and by evaluating a Cox model with a time-dependent covariate. HFNC was considered noninferior to CPAP if the bound of the 1-sided 97.5% CI for the adjusted HR was greater than 0.75 in both the primary analysis set and the per-protocol analysis.

All secondary outcomes were evaluated for statistical superiority using a 2-sided significance threshold of .05. Binary outcomes were reported as unadjusted absolute risk reduction and odds ratios (ORs), and as adjusted ORs calculated using multilevel logistic regression. Continuous outcomes were reported as unadjusted mean differences (with 95% bootstrapped CIs), and adjusted differences calculated using linear regression. Overall survival was illustrated using Kaplan-Meier curves to 180 days and reported as unadjusted and adjusted HRs calculated using Cox regression. All adjusted effect estimates were adjusted for the same baseline covariates as defined for the primary analysis. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory.

Prespecified subgroup analyses of the primary outcome were conducted testing interactions for age, Spo2:Fio2 ratio, comorbidities, length of prior IMV, reason for IMV, severity of respiratory distress, and nature of noninvasive respiratory support.

Planned sensitivity analyses included a repeat of the primary analysis using alternative durations: from start of respiratory support to liberation from respiratory support, from randomization to start of weaning, and from randomization to meeting weaning criteria.

Unplanned post hoc analyses were performed to assess the effect of patients who did not start any respiratory support (these were included in a sensitivity analysis of the primary end point by assigning them to a nominal 2 hours of respiratory support), and to evaluate the possibility of inferiority of one group by calculating a 2-sided confidence interval for the primary effect estimate.

Stata/MP version 16.1 (StataCorp) was used for all analyses.

Results

Trial Sites and Patients

From August 8, 2019, to May 18, 2020, 3121 extubated children were screened in the 22 participating PICUs, of whom 1051 fulfilled eligibility criteria and 600 (57%) were randomized. Participating unit characteristics are shown in eTable 2 in Supplement 2 and actual vs expected randomization numbers in eFigure 3 in Supplement 2. Of 587 children for whom consent was obtained, respiratory support was started in 553 children (HFNC, 281; CPAP, 272), comprising the primary analysis set, as shown in Figure 1. The randomized groups had similar baseline characteristics, except for a higher proportion of children receiving ventilation for cardiac reasons in the HFNC group (Table 1; eTable 3 in Supplement 2). The per-protocol population included 523 children (HFNC, 271; CPAP, 252; eFigure 4 in Supplement 2); baseline characteristics were similar to the primary analysis set (eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Primary Analysis Set.

| Characteristic | High-flow nasal cannula (n = 281) | Continuous positive airway pressure (n = 272) |

| Age, median (IQR), mo | 3 (1-10) | 3 (1-11) |

| Age, No. (%) | ||

| ≤28 d | 56 (19.9) | 37 (13.6) |

| 29-180 d | 122 (43.4) | 124 (45.6) |

| 181-364 d | 37 (13.2) | 46 (16.9) |

| 1 y | 25 (8.9) | 25 (9.2) |

| 2-4 y | 17 (6.0) | 14 (5.1) |

| 5-10 y | 17 (6.0) | 12 (4.4) |

| 11-15 y | 7 (2.5) | 14 (5.1) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Female | 111 (39.5) | 130 (47.8) |

| Male | 170 (60.5) | 142 (52.2) |

| At least 1 comorbidity, No. (%) | 171 (60.9) | 155 (57.0) |

| Main reason for invasive ventilation, No. (%) | ||

| Bronchiolitis | 97 (34.5) | 122 (44.9) |

| Cardiac | 81 (28.8) | 55 (20.2) |

| Other respiratory condition | 42 (14.9) | 34 (12.5) |

| Sepsis/infection | 12 (4.3) | 10 (3.7) |

| Upper airway problem | 9 (3.2) | 13 (4.8) |

| Neurologic | 7 (2.5) | 13 (4.8) |

| Asthma/wheeze | 1 (0.4) | 5 (1.8) |

| Other | 32 (11.4) | 20 (7.4) |

| Duration of prior invasive ventilation, median (IQR), h | 89 (56-145) | 87 (51-140) |

| Nature of postextubation noninvasive respiratory support, No. (%) | ||

| Planned (randomized before extubation) | 178 (63.3) | 168 (61.8) |

| Indeterminate (randomized within 1 h of extubation) | 49 (17.4) | 49 (18.0) |

| Rescue (randomized at least 1 h after extubation) | 54 (19.2) | 55 (20.2) |

| Clinical characteristics at randomizationa | ||

| Respiratory distress, No./total (%)b | n = 210 | n = 198 |

| None | 126 (60.0) | 112 (56.6) |

| Mild | 58 (27.6) | 52 (26.3) |

| Moderate | 22 (10.5) | 29 (14.6) |

| Severe | 4 (1.9) | 5 (2.5) |

| Respiratory rate, median (IQR) [No.], breaths/min | 35 (27-45) [277] | 36 (28-45) [269] |

| Peripheral oxygen saturation, median (IQR) [No.], % | 96 (94-98) [281] | 97 (94-99) [270] |

| Fraction of inspired oxygen, median (IQR) [No.] | 0.30 (0.24-0.35) [278] | 0.30 (0.25-0.35) [270] |

| Ratio of peripheral oxygen saturation to fraction of inspired oxygen, median (IQR) [No.] | 327 (271-400) [278] | 327 (274-396) [268] |

| Heart rate, median (IQR) [No.], beats/min | 128 (115-145) [280] | 132 (115-147) [272] |

| COMFORT-B score,c mean (SD) [No.] | 13.8 (2.7) [204] | 14.3 (3.2) [187] |

Data were recorded at or within 1 hour prior to randomization, except for COMFORT-B score, which was the last recorded value prior to randomization.

Respiratory distress was defined as mild: 1 accessory muscle used, mild indrawing of subcostal and intercostal muscles, mild tachypnea, no grunting; moderate: 2 accessory muscles used, moderate indrawing of subcostal and intercostal muscles, moderate tachypnea, occasional grunting; and severe: use of all accessory muscles, severe indrawing of subcostal and intercostal muscles, severe tachypnea, regular grunting.

COMFORT Behavior (COMFORT-B) scale scores range from 5 to 30 (most sedated to least sedated). A mean value of 14 indicates a comfortable patient who is easily arousable and is not agitated.

Clinical Management

In both groups, most children who started any respiratory support were started with the allocated treatment (HFNC: 272/281 [96.8%]; CPAP: 252/272 [92.6%]). There was good adherence to the trial protocol regarding timing of initiation, HFNC flow rate and CPAP pressure, and for switch, escalation and weaning events, as shown in eTable 5 and eFigures 5 and 6 in Supplement 2. A range of devices and interfaces was used to deliver HFNC and CPAP, shown in eTable 6 in Supplement 2. Treatment failure requiring a switch or escalation occurred in 101 of 272 children (37.1%) for HFNC and 85 of 252 children (33.7%) for CPAP (eFigure 7 in Supplement 2). Treatment failure occurred at a median of 10 hours after randomization for HFNC compared with 7.8 hours for CPAP. Reasons for treatment failure, particularly switch, were mainly related to clinical deterioration for HFNC and for patient discomfort for CPAP (eTable 7 in Supplement 2).

Outcomes

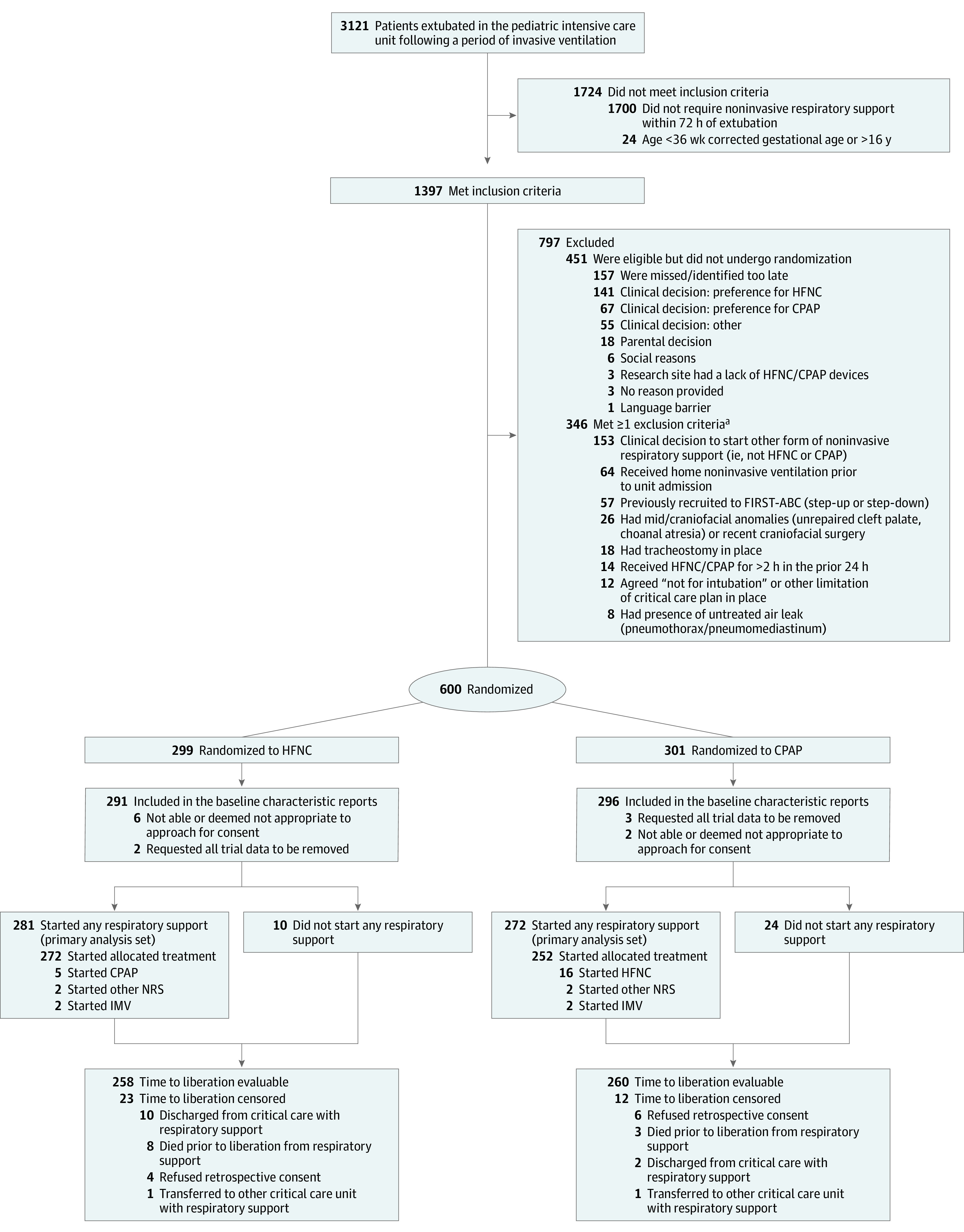

The median time from randomization to liberation from respiratory support was 50.5 hours (95% CI, 43.0-67.9) for HFNC and 42.9 hours (95% CI, 30.5-48.2) for CPAP (adjusted HR, 0.83; 1-sided 97.5% CI, 0.70-∞). The bound of the 1-sided 97.5% CI (adjusted HR, 0.70) was below the prespecified noninferiority margin (HR, 0.75). Time to liberation for HFNC and CPAP based on whether treatment failure occurred is shown in eFigure 8 in Supplement 2. A breakdown of the duration of noninvasive and invasive support received prior to liberation is shown in eTable 8 in Supplement 2.

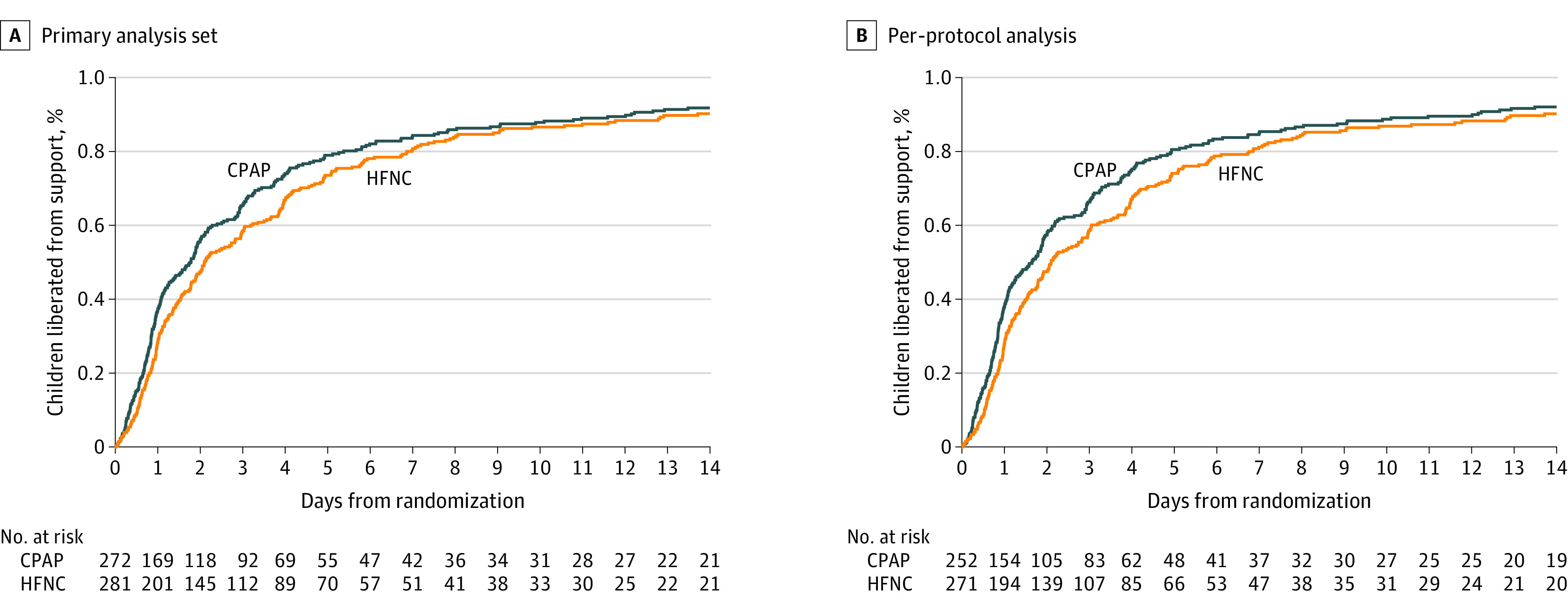

Similar results were observed in the per-protocol analysis (Table 2, Figure 2) and in prespecified subgroup analyses (Figure 3). Planned sensitivity analyses did not alter the interpretation of the primary analyses (eTable 9 in Supplement 2).

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Outcomes in the High-Flow Nasal Cannula (HFNC) Group Compared With the Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) Group.

| Outcome | Primary analysis set | Per-protocol analysis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFNC (n = 281) | CPAP (n = 272) | Difference (95% CI) | Effect estimate (95% CI) | HFNC (n = 271) | CPAP (n = 252) | Difference (95% CI) | Effect estimate (95% CI) | |||

| Unadjusteda | Adjustedb | Unadjusteda | Adjustedb | |||||||

| Primary | ||||||||||

| Time from randomization to liberation from respiratory support, median (IQR), h | 50.5 (43.0 to 67.9) | 42.9 (30.5 to 48.2) | 7.9 (– 4.4 to 20.2) | HR, 0.86 (0.72 to 1.02) | HR, 0.83 (0.70 to 0.99) | 50.5 (42.9 to 67.9) | 39.5 (28.3 to 45.8) | 10.7 (–2.2 to 23.6) | HR, 0.83 (0.69 to 0.99) | HR, 0.82 (0.68 to 0.98) |

| Secondary | ||||||||||

| Reintubation at 48 h, No./total No. (%) | 37/279 (13.3) | 31/269 (11.5) | AD, 1.7 (– 3.8 to 7.3) | OR, 1.17 (0.7 to 2.0) | OR, 1.11 (0.7 to 1.9) | 35/269 (13.0) | 29/250 (11.6) | AD, 1.4 (– 4.2 to 7.1) | OR, 1.14 (0.7 to 1.9) | OR, 1.07 (0.6 to 1.8) |

| COMFORT-B score while on randomized treatment, mean (SD) [No.] | 13.6 (2.7) [177] | 13.2 (2.2) [165] | MD, 0.4 (– 0.1 to 0.9) | MD, 0.44 (– 0.1 to 1.0) | 13.6 (2.7) [176] | 13.2 (2.2) [163] | MD, 0.4 (– 0.1 to 0.9) | MD, 0.41 (– 0.1 to 0.9) | ||

| Proportion of patients in whom sedation was used during noninvasive respiratory support, No./total No. (%) | 168/276 (60.9) | 149/264 (56.4) | AD, 4.4 (– 3.9 to 12.7) | OR, 1.20 (0.9 to 1.7) | OR, 1.14 (0.8 to 1.6) | 164/268 (61.2) | 141/246 (57.3) | 3.9 (– 4.6 to 12.4) | OR, 1.17 (0.8 to 1.7) | 1.09 (0.7 to 1.6) |

| Parental stress (PSS:PICU) score, mean (SD) [No.]c | 1.8 (0.7) [153] | 1.8 (0.8) [129] | MD, 0.0 (–0.1 to 0.2) | MD, 0.07 (–0.1 to 0.3) | 1.8 (0.7) [150] | 1.8 (0.8) [121] | MD, 0.0 (–0.2 to 0.2) | MD, 0.04 (–0.2 to 0.2) | ||

| Duration of PICU stay, mean (SD) [No.], d | 6.6 (13.4) [276] | 6.9 (16.0) [265] | MD, – 0.2 (–2.7 to 2.2) | MD, – 0.56 (– 3.0 to 1.9) | 6.6 (13.4) [266] | 6.9 (16.4) [246] | MD, – 0.3 (–2.9 to 2.3) | MD, – 0.76 (–3.3 to 1.8) | ||

| Duration of acute hospital stay, mean (SD) [No.], d | 20.6 (35.3) [275] | 20.6 (34.5) [257] | MD, 0.0 (– 5.9 to 5.8) | MD, –1.01 (– 6.9 to 4.8) | 20.3 (35.4) [265] | 20.9 (35.6) [239] | MD, –0.6 (– 6.5 to 5.4) | MD, –1.95 (– 8.0 to 4.2) | ||

| Mortality, No./total No. (%) | ||||||||||

| At PICU discharge | 5/277 (1.8) | 3/267 (1.1) | AD, 0.7 (– 1.3 to 2.7) | OR, 1.62 (0.4 to 6.8) | OR, 2.69 (0.5 to 15.4) | 5/267 (1.9) | 1/247 (0.4) | AD, 1.5 (– 0.3 to 3.3) | 4.69 (0.5 to 40.5) | 4.79 (0.5 to 44.4) |

| At day 60 | 11/270 (4.1) | 3/256 (1.2) | AD, 2.9 (0.2 to 5.6) | OR, 3.58 (1.0 to 13.0) | OR, 5.99 (1.2 to 28.7) | 11/260 (4.2) | 1/239 (0.4) | AD, 3.8 (1.2 to 6.4) | OR, 10.51 (1.3 to 82.1) | OR, 10.75 (1.3 to 86.6) |

| At day 180 | 15/268 (5.6) | 6/253 (2.4) | AD, 3.2 (–0.1 to 6.6) | OR, 2.44 (0.9 to 6.4) | OR, 3.07 (1.1 to 8.8) | 15/258 (5.8) | 4/236 (1.7) | AD, 4.1 (0.8 to 7.4) | OR, 3.58 (1.2 to 10.9) | OR, 3.71 (1.2 to 11.7) |

Abbreviations: AD, absolute difference; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula therapy; HR, hazard ratio; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; MD, mean difference; OR, odds ratio; PICU, pediatric neonatal intensive care unit.

Unadjusted effect estimate is not separately reported for some rows, because it is the mean difference as reported in the difference column.

Adjusted for prebaseline factors of age (<12 months vs ≥ 12 months), oxygen saturation to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio, comorbidities (none vs neurologic/neuromuscular vs other), length of prior IMV (<5 days vs ≥ 5 days), reason for IMV (cardiac vs other), and site (using shared frailty). We did not adjust for severity of respiratory distress (severe vs mild/moderate), as originally planned, due to low numbers in the severe group.

Parental Stressor Scale: PICU (PSS:PICU) scores range from 1 to 5 (not stressful to extremely stressful). A mean value of 1.8 indicates a low level of parental stress at the time of completing the questionnaire.

Figure 2. Time to Liberation From Respiratory Support in the Primary Analysis Set and Per-Protocol Analysis.

The median observation time was 49.4 hours (IQR, 22.9-118.7) for high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) and 40.1 hours (IQR, 18.0-96.7) for continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in the primary analysis set and 49.4 hours (IQR, 22.9-118.5) for HFNC and 37.5 hours (IQR, 17.8-95.0) for CPAP in the per-protocol analysis.

Figure 3. Subgroup Analyses of the Primary Outcome in the Primary Analysis Set.

P values test for an interaction between the subgroup categories and the effect of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) vs high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) in the adjusted Cox regression model. IMV indicates invasive mechanical ventilation and Spo2:Fio2, oxygen saturation to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio.

Secondary outcomes are shown in Table 2 and eTable 10 in Supplement 2. Mortality by day 180 was significantly higher in the HFNC group (5.6% vs CPAP, 2.4%; adjusted OR, 3.07 [95% CI, 1.1-8.8]; eTable 11 in Supplement 2). The rate of reintubation within 48 hours was not significantly different between the groups (HFNC, 13.3%; CPAP, 11.5%; adjusted OR, 1.17 [95% CI, 0.7-2.0]). Time to reintubation was a median of 25 hours (IQR, 8-79) after randomization for HFNC compared with 11 hours (IQR, 2.5-49) for CPAP (eTable 12 in Supplement 2). Overall, compared with children not reintubated, reintubated children had a significantly longer time to liberation from respiratory support (median, 242 hours [IQR, 187-310] vs 33 hours [IQR, 28-40]). eFigures 9 and 10 in Supplement 2 show Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the primary analysis set and the per-protocol analysis.

A post hoc analysis assigning patients who did not start any respiratory support a nominal time to liberation of 2 hours also failed to demonstrate the noninferiority of HFNC (eTable 13 and eFigure 11 in Supplement 2). The upper 95% CI for the primary effect estimate was 0.99, indicating the inferiority of HFNC compared with CPAP.

Adverse Events

The number of children with 1 or more adverse events was low in both groups, occurring in 25 of 281 children (8.9%) in the HFNC group and 28 of 272 (10.3%) in the CPAP group (eTable 14 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

In this multicenter, pragmatic, randomized trial, first-line use of HFNC compared with CPAP following extubation of critically ill children failed to meet the noninferiority criterion for time from randomization to liberation from respiratory support.

To our knowledge, the FIRST-ABC step-down RCT is the first clinical trial to compare 2 commonly used modes of noninvasive respiratory support for postextubation support in critically ill children. The master protocol efficiently allowed the comparison of HFNC and CPAP in 2 distinct patient populations (acute respiratory failure and postextubation) within the same trial infrastructure. FIRST-ABC was designed as a noninferiority trial, similar to previous RCTs of HFNC,20,27,28 rather than a superiority trial, because clinicians indicated willingness to tolerate some additional time to liberation in return for greater patient comfort and ease of use for HFNC.15 The trial findings were consistent across the primary, subgroup, and sensitivity analyses and clearly showed that HFNC failed to meet noninferiority.

There are no agreed core outcome sets for pediatric respiratory support trials. Treatment failure has been used as the primary outcome in RCTs of HFNC in preterm newborns and bronchiolitis. However, its definition varies between trials; and, in real-world practice, because patients are frequently rescued after treatment failure, it does not usually translate to changes in patient-centered outcomes.29,30,31 Although RCTs in adults have focused on reintubation, fewer than 1 in 8 extubated children required reintubation in this trial, and those not reintubated also spent a long time receiving noninvasive respiratory support before achieving unassisted breathing. Parents of children with severe infection have previously highlighted length of time receiving treatments or mechanical support as an important outcome32; similarly, prior to this trial, parents indicated that being free of any breathing machine was a key priority. Therefore, time to liberation from all forms of respiratory support was chosen as a sensitive measure that considered both reintubation (because reintubated children had a longer time to liberation) and prolonged use of noninvasive respiratory support in those children not reintubated. Time to liberation was used as the primary outcome in a trial of protocolized respiratory support after extubation of critically ill adults (BREATHE)33 and is consistent with the core outcome of time to liberation from ventilation for adult critical care ventilation trials.34

Despite a strong clinical preference to start HFNC following extubation, it was associated with significantly longer time to liberation from respiratory support in our trial, including in prespecified subgroups. This difference was evident in children who had unsuccessful first-line HFNC as well as those who did not. Among those with treatment failure, HFNC did not appear to provide sufficient respiratory support, resulting in clinical deterioration and a switch to CPAP and/or further escalation. Time to first switch or escalation and time to reintubation were both longer for patients receiving HFNC, indicating a delay in escalation, previously highlighted in adults.35 Among children who did not experience treatment failure with HFNC, the comfort of HFNC may have prolonged weaning duration, although COMFORT-B scores were comparable between groups (only 10% of children were switched from CPAP to HFNC for discomfort reasons). Even though the median difference in time to liberation of nearly 8 hours may not seem clinically important, especially considering the ability to discharge children to general wards on HFNC, it represented nearly 20% of the overall time to liberation, and the observed lower bound of the HR of 0.70 corresponded to an additional 18 hours in time to liberation for HFNC. There was no difference in the length of hospital stay or complication rate (including pneumothorax and nasal or facial trauma), possibly due to the short duration of respiratory support. A high proportion of children received postextubation noninvasive respiratory support in our trial (45%), suggesting potential overuse highlighting the need for an RCT of protocolized postextubation noninvasive respiratory support. The higher adjusted mortality for HFNC at 180 days is unexplained and should be interpreted with caution pending further research.

This trial has several strengths. First, to our knowledge, it is the largest and only RCT comparing 2 commonly used modes of postextubation noninvasive respiratory support, with the potential to inform practice. Second, a representative sample of 22 of the 28 UK PICUs participated. Third, adherence to trial algorithms was good. Fourth, results of several sensitivity and post hoc analyses were consistent with the main findings.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the inability to blind clinicians to the allocated treatment may have influenced clinicians’ thresholds to switch, escalate, and wean treatment. Second, the pragmatic inclusion criteria resulted in a heterogeneous population of critically ill children enrolled; however, several prespecified subgroup analyses based on factors such as age, diagnosis, and duration of prior IMV are reported. Many recruited participants were infants younger than 1 year, limiting the generalizability of trial findings to other age groups. Third, children treated with respiratory support modes other than HFNC and CPAP postextubation were excluded. Fourth, a number of eligible patients were not recruited owing to clinical preference, and some patients were not treated with any respiratory support after randomization, which may have biased the trial population.36 Fifth, ventilation data, such as mean airway pressure at randomization, were not collected, which might have indicated why clinicians chose to start noninvasive respiratory support in some patients. Sixth, despite randomization, there were more newborns and cardiac patients in the HFNC group, potentially with associated chronic respiratory failure, which may have prolonged the time to liberation. Seventh, because data related to feeding was not collected as part of the trial, it was not possible to assess the effect of feeding on patient comfort.

Conclusions

Among critically ill children requiring noninvasive respiratory support following extubation, HFNC compared with CPAP following extubation failed to meet the criterion for noninferiority for time to liberation from respiratory support.

Section Editor: Christopher Seymour, MD, Associate Editor, JAMA (christopher.seymour@jamanetwork.org).

Trial Protocol

eMethods

eFigure 1. Trial Algorithm for the Delivery of High Flow Nasal Cannula (HFNC)

eFigure 2. Trial Algorithm for the Delivery of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP)

eFigure 3. Actual Versus Expected Patient Randomisation

eFigure 4. Screening, Randomisation and Follow-up in the Per-Protocol Population

eFigure 5. HFNC Flow Rates During the First Six Hours of Treatment

eFigure 6. CPAP Pressures During the First Six Hours of Treatment

eFigure 7. Clinical Management of Trial Patients

eFigure 8. Breakdown of the Time to Liberation From Respiratory Support by Occurrence of Treatment Failure in Children Who Started the Allocated Treatment

eFigure 9. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve in the Primary Analysis Set

eFigure 10. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve in the Per-Protocol Analysis

eFigure 11. Time to Liberation From Respiratory Support – Post-Hoc Sensitivity Analysis in All Randomized Children Including Those Who Were Not Started on Respiratory Support

eTable 1. Patient Data Collection Schedule

eTable 2. Characteristics of Participating UK National Health Service PICUs

eTable 3. Additional Baseline Characteristics, Including Physiological Variables Split by Child On/Not On IMV at Randomization in the Primary Analysis Set

eTable 4. Baseline Characteristics in the Per-Protocol Population

eTable 5. Adherence With Trial Algorithms in Children Who Started the Allocated Treatment

eTable 6. Devices and Interfaces Used in Children Who Started the Allocated Treatment

eTable 7. Timing and Reasons for Treatment Failure (Switch/Escalation Events) in Children Who Started the Allocated Treatment

eTable 8. Breakdown of the Duration of Invasive and Non-invasive Respiratory Support Prior to Liberation in the Primary Analysis Set

eTable 9. Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 10. Comfort-B Score - While on HFNC or CPAP

eTable 11. Characteristics of Children Who Died Within Six Months of Randomization in the Primary Analysis Set

eTable 12. Time to Reintubation in the Primary Analysis Set

eTable 13. Baseline Characteristics in All Randomized and Consented Children Irrespective of Whether Respiratory Support Was Started or Not

eTable 14. Summary of Adverse Events and Serious Adverse Events

eReferences

Nonauthor Collaborators

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership . Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network annual report 2020. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.picanet.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/25/2021/02/PICANet2020_AnnualReportSummary_v1.0.pdf

- 2.Kneyber MC, Zhang H, Slutsky AS. Ventilator-induced lung injury: similarity and differences between children and adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(3):258-265. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201401-0168CP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krasinkiewicz JM, Friedman ML, Slaven JE, Tori AJ, Lutfi R, Abu-Sultaneh S. Progression of respiratory support following pediatric extubation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020;21(12):e1069-e1075. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munshi L, Ferguson ND. Weaning from mechanical ventilation: what should be done when a patient’s spontaneous breathing trial fails? JAMA. 2018;320(18):1865-1867. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayordomo-Colunga J, Medina A, Rey C, et al. Non invasive ventilation after extubation in paediatric patients: a preliminary study. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-10-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramnarayan P, Schibler A. Glass half empty or half full? the story of high-flow nasal cannula therapy in critically ill children. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(2):246-249. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4663-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawaguchi A, Garros D, Joffe A, et al. Variation in practice related to the use of high flow nasal cannula in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020;21(5):e228-e235. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris JV, Kapetanstrataki M, Parslow RC, Davis PJ, Ramnarayan P. Patterns of use of heated humidified high-flow nasal cannula therapy in PICUs in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20(3):223-232. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coletti KD, Bagdure DN, Walker LK, Remy KE, Custer JW. High-flow nasal cannula utilization in pediatric critical care. Respir Care. 2017;62(8):1023-1029. doi: 10.4187/respcare.05153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granton D, Chaudhuri D, Wang D, et al. High-flow nasal cannula compared with conventional oxygen therapy or noninvasive ventilation immediately postextubation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(11):e1129-e1136. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson KN, Roberts CT, Manley BJ, Davis PG. Interventions to improve rates of successful extubation in preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(2):165-174. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernando SM, Tran A, Sadeghirad B, et al. Noninvasive respiratory support following extubation in critically ill adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48(2):137-147. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06581-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kneyber MCJ, de Luca D, Calderini E, et al. ; section Respiratory Failure of the European Society for Paediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care . Recommendations for mechanical ventilation of critically ill children from the Paediatric Mechanical Ventilation Consensus Conference (PEMVECC). Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(12):1764-1780. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4920-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramnarayan P, Lister P, Dominguez T, et al. ; United Kingdom Paediatric Intensive Care Society Study Group (PICS-SG) . FIRST-line support for Assistance in Breathing in Children (FIRST-ABC): a multicentre pilot randomised controlled trial of high-flow nasal cannula therapy versus continuous positive airway pressure in paediatric critical care. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):144. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2080-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richards-Belle A, Davis P, Drikite L, et al. FIRST-line support for assistance in breathing in children (FIRST-ABC): a master protocol of two randomised trials to evaluate the non-inferiority of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) versus continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for non-invasive respiratory support in paediatric critical care. BMJ Open. 2020;10(8):e038002. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.PRECIS-2 . FIRST-line support for Assistance in Breathing in Children (FIRST-ABC): a master protocol of two randomised trials to evaluate the non-inferiority of high flow nasal cannula (HFNC) versus continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for non-invasive respiratory support in paediatric critical care. Accessed November 12, 2021. https://www.precis-2.org/Trials/Details/10688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Harron K, Woolfall K, Dwan K, et al. Deferred consent for randomized controlled trials in emergency care settings. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1316-e1322. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woolfall K, Frith L, Gamble C, Gilbert R, Mok Q, Young B; CONNECT advisory group . How parents and practitioners experience research without prior consent (deferred consent) for emergency research involving children with life threatening conditions: a mixed method study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(9):e008522. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orzechowska I, Sadique MZ, Thomas K, et al. First-line support for assistance in breathing in children: statistical and health economic analysis plan for the FIRST-ABC trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):903. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04818-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manley BJ, Owen LS, Davis PG. High-flow nasal cannulae in very preterm infants after extubation. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(4):385-386. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1314238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts CT, Owen LS, Manley BJ, et al. ; HIPSTER Trial Investigators . Nasal high-flow therapy for primary respiratory support in preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(12):1142-1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milési C, Essouri S, Pouyau R, et al. ; Groupe Francophone de Réanimation et d’Urgences Pédiatriques (GFRUP) . High flow nasal cannula (HFNC) versus nasal continuous positive airway pressure (nCPAP) for the initial respiratory management of acute viral bronchiolitis in young infants: a multicenter randomized controlled trial (TRAMONTANE study). Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(2):209-216. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4617-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blackwood B, Tume LN, Morris KP, et al. ; SANDWICH Collaborators . Effect of a sedation and ventilator liberation protocol vs usual care on duration of invasive mechanical ventilation in pediatric intensive care units: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326(5):401-410. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.10296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Dijk M, Peters JWB, van Deventer P, Tibboel D. The COMFORT Behavior Scale: a tool for assessing pain and sedation in infants. Am J Nurs. 2005;105(1):33-36. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200501000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carter MC, Miles MS. The Parental Stressor Scale: pediatric intensive care unit. Matern Child Nurs J. 1989;18(3):187-198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaji AH, Lewis RJ. Noninferiority trials: is a new treatment almost as effective as another? JAMA. 2015;313(23):2371-2372. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernández G, Vaquero C, Colinas L, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs noninvasive ventilation on reintubation and postextubation respiratory failure in high-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(15):1565-1574. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.14194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stéphan F, Barrucand B, Petit P, et al. ; BiPOP Study Group . High-flow nasal oxygen vs noninvasive positive airway pressure in hypoxemic patients after cardiothoracic surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(23):2331-2339. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.5213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong H, Li XX, Li J, Zhang ZQ. High-flow nasal cannula versus nasal continuous positive airway pressure for respiratory support in preterm infants: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;34(2):259-266. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2019.1606193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cunningham S, Fernandes RM. High-flow oxygen therapy in acute bronchiolitis. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):886-887. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30192-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franklin D, Babl FE, Schlapbach LJ, et al. A randomized trial of high-flow oxygen therapy in infants with bronchiolitis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1121-1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woolfall K, O’Hara C, Deja E, et al. ; PERUKI (Paediatric Emergency Research in the UK and Ireland) and PICS (Paediatric Intensive Care Society) . Parents’ prioritised outcomes for trials investigating treatments for paediatric severe infection: a qualitative synthesis. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104(11):1077-1082. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2019-316807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perkins GD, Mistry D, Gates S, et al. ; Breathe Collaborators . Effect of protocolized weaning with early extubation to noninvasive ventilation vs invasive weaning on time to liberation from mechanical ventilation among patients with respiratory failure: the Breathe Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;320(18):1881-1888. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blackwood B, Ringrow S, Clarke M, et al. A core outcome set for critical care ventilation trials. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(10):1324-1331. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang BJ, Koh Y, Lim CM, et al. Failure of high-flow nasal cannula therapy may delay intubation and increase mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(4):623-632. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3693-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arabi YM, Cook DJ, Zhou Q, et al. ; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group . Characteristics and outcomes of eligible nonenrolled patients in a mechanical ventilation trial of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(11):1306-1313. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201501-0172OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eMethods

eFigure 1. Trial Algorithm for the Delivery of High Flow Nasal Cannula (HFNC)

eFigure 2. Trial Algorithm for the Delivery of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP)

eFigure 3. Actual Versus Expected Patient Randomisation

eFigure 4. Screening, Randomisation and Follow-up in the Per-Protocol Population

eFigure 5. HFNC Flow Rates During the First Six Hours of Treatment

eFigure 6. CPAP Pressures During the First Six Hours of Treatment

eFigure 7. Clinical Management of Trial Patients

eFigure 8. Breakdown of the Time to Liberation From Respiratory Support by Occurrence of Treatment Failure in Children Who Started the Allocated Treatment

eFigure 9. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve in the Primary Analysis Set

eFigure 10. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve in the Per-Protocol Analysis

eFigure 11. Time to Liberation From Respiratory Support – Post-Hoc Sensitivity Analysis in All Randomized Children Including Those Who Were Not Started on Respiratory Support

eTable 1. Patient Data Collection Schedule

eTable 2. Characteristics of Participating UK National Health Service PICUs

eTable 3. Additional Baseline Characteristics, Including Physiological Variables Split by Child On/Not On IMV at Randomization in the Primary Analysis Set

eTable 4. Baseline Characteristics in the Per-Protocol Population

eTable 5. Adherence With Trial Algorithms in Children Who Started the Allocated Treatment

eTable 6. Devices and Interfaces Used in Children Who Started the Allocated Treatment

eTable 7. Timing and Reasons for Treatment Failure (Switch/Escalation Events) in Children Who Started the Allocated Treatment

eTable 8. Breakdown of the Duration of Invasive and Non-invasive Respiratory Support Prior to Liberation in the Primary Analysis Set

eTable 9. Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 10. Comfort-B Score - While on HFNC or CPAP

eTable 11. Characteristics of Children Who Died Within Six Months of Randomization in the Primary Analysis Set

eTable 12. Time to Reintubation in the Primary Analysis Set

eTable 13. Baseline Characteristics in All Randomized and Consented Children Irrespective of Whether Respiratory Support Was Started or Not

eTable 14. Summary of Adverse Events and Serious Adverse Events

eReferences

Nonauthor Collaborators

Data Sharing Statement