Graphical abstract

Keywords: COVID-19, CFD simulation, OpenFOAM, Ventilation, Aerosol, Dispersion, Particle tracking, Discrete Phase Method (DPM)

Abstract

The current COVID-19 pandemic has underlined the importance of learning more about aerosols and particles that migrate through the airways when a person sneezes, coughs and speaks. The coronavirus transmission is influenced by particle movement, which contributes to the emergence of regulations on social distance, use of masks and face shield, crowded assemblies, and daily social activity in domestic, public, and corporate areas. Understanding the transmission of aerosols under different micro-environmental conditions, closed, or ventilated, has become extremely important to regulate safe social distances. The present work attempts to simulate the airborne transmission of coronavirus-laden particles under different respiratory-related activities, i.e., coughing and speaking, using CFD modelling through OpenFOAM v8. The dispersion coupled with the Discrete Phase Method (DPM) has been simulated to develop a better understanding of virus carrier particles transmission processes and their path trailing under different ventilation scenarios. The preliminary results of this study with respect to flow fields were in close agreement with published literature, which was then extended under varied ventilation scenarios and respiratory-related activities. The study observed that improper wearing of mask leads to escape of SARS-CoV-2 containminated aerosols having a smaller aerodynamic diameter from the gap between face mask and face, infecting different surfaces in the vicinity. It was also observed that aerosol propagation infecting the area through coughing is a faster phenomenon compared to the propagation of coronavirus-laden particles during speaking. The study's findings will help decision-makers formulate common but differentiated guidelines for safe distancing under different micro-environmental conditions.

1. Introduction

The airborne transmission risk of the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first confirmed by the National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China and then by the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as the world faces a large outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (Wang and Du, 2020, Feng et al., 2020). Despite the fact that SARS-CoV-2 has a viral diameter ranging from 50 to 200 nm, it has been proved that SARS-CoV-2 transmits through inhalation or ingestion of contaminated particles. As a result, the principal causes of infection include coughing and contacting infected surfaces. The SARS-CoV-2 disease is well-known for relying on the transmission of tiny virus-containing respiratory particles that an infected person exhales when coughing or merely speaking or breathing (Guzman, 2020, Asadi et al., 2019). The outbreak is at a distinct stage in each country. To slow the spread of the COVID-19 outbreak in most nations where the virus has produced exponential outbreaks, governments have asked for social distancing and mobility restrictions, often known as lockdown (WHO, 2020a). The World Health Organization (WHO) established guidelines stating that a virus takes 5 to 6 days to incubate, with a range of up to 14 days. COVID-19 symptoms are nonspecific and vary greatly, ranging from no symptoms to severe pneumonia and mortality. Depending on the instance, fever, dry cough, weariness, nasal congestion, diarrhea, and headache are some of the symptoms of COVID-19 (Aldila et al., 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a significant loss of civilian life throughout the world, and it poses an unprecedented threat to public health, food systems, and the workplace with psychological, economic, and societal consequences over the world, in addition to death. Few of the recent literature has also predicted the COVID-19 waves and the impact of environmental conditions, surface characteristics, air pollution, etc. on the spread of the virus (Bherwani et al., 2020a, Bherwani et al., 2021a, Wathore et al., 2020, Nair et al., 2021). Some work has also suggested that air pollution and particle size play a vital role in the transmission of the SARS-COV-2, as these air particulates, especially PM2.5, act as carriers for the longer distance transmissions of the virus (Gupta et al., 2021, Bherwani et al., 2020c).

Due to lockdown, social distance, and economic crises, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to changes in the business environment and indirectly impacted gender disparity (Thakur and Jain, 2020). Distancing oneself from others is one of the most efficient ways to slow the transmission of the virus, which is conveyed by air particles. Wearing masks, washing hands often, cleaning surfaces with alcohol, and avoiding physical contact can all help prevent the spreading of the infection and thus form an integral part of COVID-19 appropriate behaviour (Qian and Jiang, 2020). However, improper disposal of masks and special PPE kits might be risky and infect the people in the surrounding (Kumar et al., 2021). Fine particles of water, air, tiny particles (having a diameter less than 1 μm), and respiratory fluid occur as a result of active breathing and coughing. These components of human reflex processes generate at varying rates and for longer periods, resulting in a variety of impacts on the environment and the human body (Vuorinen et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2015, Dudalski et al., 2020). Aerosol particles transmission is primarily determined by the size of the particles and the speed at which they propagate (Guan et al., 2014, Sun and Ji, 2007, Chen and Zhao, 2010). According to studies, particles with a larger diameter (100 to 1000 μm) fall on surfaces abruptly due to gravity. In contrast, particles with a smaller diameter (1 to 100 μm) can travel by air and remain suspended for a long period which is sufficient to carry both bacteria and viruses with SARS-CoV-2 Ribonucleic Acid (RNA) (Aliabadi et al., 2010, Gralton et al., 2011, Wei and Li, 2015, Wells, 1934, Yang et al., 2007). During 5 min of conversation, a single individual can release about 3000 germs, while coughing can release even more particles. These particles are too small to be seen with the naked eye, but they are large enough to fly through the air and spread disease (Lindsley et al., 2010, To et al., 2020, Fabian et al., 2011). A study conducted by Feng et al. investigated the impact of humidity and wind on the effect of social distance in preventing maximal airborne transmission using a numerical model (Feng et al., 2020). To simulate realistic air flows during inhalation and the distribution of air-borne particles in the room, Xu et al. used the area surrounding the human face as geometry as the infectious aerosols exist in various shapes and sizes tracking their dispersion is particularly difficult (Xu et al., 2018). The work by Hasan suggested that CFD be used to improve the ventilation system and remove infectious particles curbing the spread of the virus (Hasan, 2020). Using environmental conditions, Busco et al. statistically examined the sneezing process in a COVID-19 virus-infected asymptomatic carrier (Busco et al., 2020). Zhang et al. conducted a study to determine the size of aerosol in the room and the coughing of the patient (Zhang et al., 2019). Furthermore, the microparticles' size is an essential element influencing aerosol particle dispersion and deposition (Gao and Niu, 2007, Morawska, 2006). The transport of expelled drops can be separated into two steps, the first is linear jet transport during coughing, and the second is small particles dispersion by the airflow in the room, as the reaction speed of breathing and coughing upon escape is on average approximately 1–22 m/s (Issakhov et al., 2021a). It is vital to mimic the generation and dissemination of viruses in an artificial environment to understand better how they propagate (Löhner et al., 2020).

Inhalation of coronavirus-laden air-borne particles produced from an infected person can help transmit the diseases to multiple people in the vicinity. Also, in closed areas, the restricted flow can aid the presence of the virus on numerous surfaces of the room and increase the chances of virus spread. The multiple respiratory-related activities like speaking, coughing, and breathing release micro air particles or aerosols/particulates, which can be infected, if released from an infected person. Hence, to curb the spread of the virus through airways, it will be important to understand the transmission distance of the virus under different human activities and ventilation scenarios to avoid physical contact with infected surfaces and physical contact with potentially infected persons. Given this, it will be essential to simulate particulate/aerosol transmission to develop insights into the infected surface under different real-world conditions.

OpenFOAM v8 is used in this study to model the airborne transmission of aerosol generated when breathing, speaking, and coughing in a closed setting, as well as its dispersion under various artificial ventilation conditions. Scenarios are created based on the demand for airflow in the room, allowing researchers to quantify the actual and realistic flow and dispersion of aerosol particles in a room. For a better understanding, several permutation combinations of fan and air conditioner (AC) are simulated, and comparisons of speaking and coughing scenarios with and without a mask are investigated. All the situations are created using current safe distance (1.8 m) guidelines. In all scenarios, tracking of aerosol particles on room surfaces is attempted.

2. Methodology

The behaviour and propagation of aerosol produced during speaking and coughing are modelled using an open-source CFD tool OpenFOAM. The subsequent sections discuss the mathematical model, the detailed validation, and the numerical setup used in this study.

2.1. Mathematical model

Navier-Stokes equations are the fundamental set of equations used to build a mathematical model in this study for the airflow in a room, which are numerically implemented by the OpenFOAM v8. The continuity and momentum equations used in the model are defined by Eq. (1) and Eq. (2) (Openfoam, 2014).

| (1) |

| (2) |

where, is the effective viscosity, p is the pressure in pascal, S is the external force of the body. The suffices a and b denote the b direction on a surface normal to a direction.

Using a Lagrangian approach, the discrete phase modelling (DPM), which relates to the processes of aerosol particles dispersion throughout the required computational domain, is calculated as a sequence of differential equations. For the motion of isothermal particles, the following set of ordinary differential equations was solved, which gave the kinematic relationship between the speed of the aerosol particle with the corresponding position in Eq. (3) and Eq. (4).

| (3) |

| (4) |

where, is the position of a particle, is the speed of particles, is the mass of particles and is the force acting on the particles.

Newton's second law of motion assumes that all relevant forces acting on a particle, such as drag, gravitational and buoyancy forces, and pressure forces, are taken into account, which can be represented by Eq. (5).

| (5) |

Among all the forces, drag is the most important force (about 80% of the total force), which is measured in terms of the drag coefficient . The drag force can be presented by Eq. (6).

| (6) |

where, is the fluid density, is the diameter of a particle.

The SST k-ω turbulence model was employed to perform the OpenFOAM simulations under the various boundary conditions. All the model equations used for the simulation and description have been referred from peer-reviewed publications (Spalart, 1997, Menter, 1994, Menter and Kuntz, 2003, Jones and Launder, 1972). The SST k-ω model was used owing to its ability to demonstrate a precise depiction of the indoor airflow (Stamou and Katsiris, 2006, Zhang et al., 2009, Hussain and Oosthuizen, 2012, Hussain et al., 2012, Issakhov et al., 2021b, Issakhov et al., 2020).

2.2. Validation

To validate the simulated results of the DPM model, a test case was simulated and compared with the result of Han et al. (2019) for the ventilation in a room. Further, the results were also validated with an onsite sample collection in a SARS-CoV-2 dedicated hospital performed by Dubey et al. (2021).

2.2.1. Ventilation validation setup

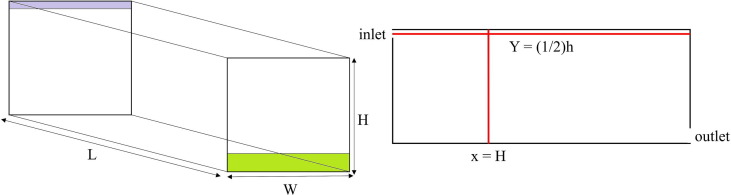

A test case was designed as per the data given by Han et al. (2019) to perform a ventilation scenario for the validation, and the data calculated by Nielsen et al. (2010) after experimenting was taken as the basis of the present study test case. A 3D model was created consisting of an enclosed room having one inlet and outlet as shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Configuration of computational domain for ventilation validation. 3D domain (left), validation configuration (right).

The detailed description of the 3D model parameters and the physical parameters used for a test case are mentioned in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Geometry configuration and material properties for validation.

| Geometry configuration | |

|---|---|

| Room dimensions | 9 m × 3 m × 3 m (L × W × H) |

| Inlet slit dimensions | 3 m × 0.168 m (a × b) |

| Outlet slit dimensions | 3 m × 0.48 m (c × d) |

| Grid size | 225 × 75 × 75 |

| Material Properties | |

| Dynamic air viscosity | 1.7894 × 10–5 kg/ms |

| Density | 1.225 kg/m3 |

| Specific heat | 1006.43 J/kg-K |

| Thermal conductivity | 0.0242 W/mk |

| Molecular weight | 28.966 kg/kmol |

| Entropy | 194,366 J/kgmol-K |

| Reference temperature | 298.15 K |

All the parameters used to simulate the test case have been given by Han et al. (2019). The reason for choosing such a type of computational grid is to improve the accuracy of the fluid flow and ease the comparison with experimental data. Air material with its conditional parametric values for a closed room with ventilation is chosen. Fig. 1 shows some cross-sectional areas (x = H and y = 1/2a) where the air velocity was calculated.

2.2.2. Particles tracking validation setup

The study has proceeded for the further and most important validation. The sample collection of aerosols containing SARS CoV-2 RNA has been performed by Dubey et al. (2021). The study was conducted in the various ward of COVID dedicated hospital. It was not possible to create geometry and simulate a model for the entire hospital ward. For the validation, an area of the “Medicine Ward” was taken containing a patient with a mask, a patient’s bed, surrounding walls, and two air conditioners and a sampler as can be seen in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 . A 3D geometry was created according to the hospital data provided by Dubey et al. (2021). For particle tracking, researchers used vacuum motor with sampler installed in it at 1.5, 16.7 and 27 LPM flow rates. To validate the results, two attempts of OpenFOAM simulation have been made with the SST k-omega model. The physical parameters and aerosol particles parameters used in this case are based on data given by Han et al., 2019, Kwon et al., 2012.

Fig. 2.

Geometry of hospital ward.

Fig. 3.

Hospital ward used for validation. Ward geometry with dimensions (left), hospital ward (right).

2.3. Model case setup

DPM modelling has been performed throughout the cases for the present study with an SST k-ω turbulence model to track the particles expelled by a person. A total of twelve cases are simulated with different ventilation and boundary conditions with and without the mask. All the cases are considered with the same room but varying ventilation conditions. The room having dimensions 5.8 m × 4 m × 3 m consists of a ventilation window, AC, fan and a window to allow air inside the room. Two human bodies are considered in the room, one was set as an active man through which particles are injected into the room and the other was set as an inactive man with no respiratory-related activities. The detailed dimensions of all the objects are discussed in Fig. 4 .

Fig. 4.

Computational domain of present study.

The ‘blockMesh’ utility of OpenFOAM is used to create a room with all required dimensions followed by another utility ‘snappyHexMesh’ which is used to recreate the block mesh. In this study, 3D CAD (Computer-Aided Design) models of human bodies, a fan, an AC, a window, and an outlet patch have been overwritten by this utility. The overlook of some objects after meshing used in this study can be seen in Fig. 5 . The grid independence for the modelling has been achieved at 145 × 100 × 75 refinements of the blockMesh.

Fig. 5.

OpenFOAM geometries after meshing.

There are a total of three scenarios (Scenario 1, 2 & 3) simulated with twelve permutation combinations of with and without mask consisting of speaking and coughing. In Scenario 1, a five minutes simulation is carried out for speaking by an active person standing on the left (in every case) and five times repeated coughing is considered by an active person in the case of coughing. The particle size distribution for the speaking has been set from 0.1 μm to 200 μm. On the other hand, in the case of coughing, the diameter is set in the range of 0.1 μm to 1000 μm (Chao et al., 2009, Duguid, 1945, Duguid, 1946, Fennelly et al., 2004, Gerone et al., 1966, Johnson and Morawska, 2009, Loudon and Roberts, 1967, Xie et al., 2009). The injection velocities of particles for speaking and coughing were set to 3.22 m/s and 20 m/s, respectively and, the speaking and coughing angle was set to 32.85° and 17.45° which are the mean velocities and cone angles of men and women (Kwon et al., 2012). So, each scenario consists of two sets of simulations with and without the mask.

In Scenario 1, a room is considered without an external air entry but with a ventilation window on a side wall as an exhaust patch. Only an active person (standing on the left) is doing activities (speaking and coughing) while the other person (standing on the right) is considered idle without any activity. The purpose of Scenario 1 is to track particle dispersion in zero ventilation conditions. In Scenario 2, the same activities have been considered as in Scenario 1 by the active person and inactive person. The configuration of the room in Scenario 2 consists of an AC installed on the sidewall in the middle of both the person with an exhaust patch. The inlet velocity of the AC patch is considered as 0.5 m/s in positive X and negative Z directions. The same set of combinations of cases are considered in Scenario 1 and in Scenario 3, the same combination of cases and activities is considered in Scenario 1 & 2. A room has a ceiling fan, air window and a ventilation window on the sidewalls are considered. The fan is assumed by a circular patch having a radius of 0.6 m at 0.2 m below the height of THE\. An air window on a sidewall is considered with dimensions 1.5 m × 1 m (l × h) for air entry in the room and a ventilation window for the outflow of air from the room of dimensions 0.5 m × 0.3 m (l × h). Fan generated a velocity field of 0.5 m/s by the fan inlet patch in negative Z-direction and an air window on a side wall generated an air inlet velocity of 0.1 m/s in positive X-direction. As there is a fan inlet patch installed on the ceiling and an air window on the sidewall of the room to allow air inside, the simulation configuration has been set the same as that of the AC room case. The type of scenarios with detailed room ventilation and respiratory activities are described in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Types of scenarios.

| Sr. No. | Scenario | Room Configuration | Respiratory activity | Sub-case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Without an air entry in the room |

|

1.A. Speaking | 1.A.1. With mask 1.A.2. Without mask |

| 1.B. Coughing | 1.B.1. With mask 1.B.2. Without mask |

|||

|

Air entry from AC | 3. AC inlet 4. Outlet |

2.A. Speaking | 2.A.1. With mask 2.A.2. Without mask |

| 2.B. Coughing | 2.B.1. With mask 2.B.2. Without mask |

|||

|

Air entry from ceiling fan and window | 4. Fan inlet 5. Window 6. Outlet |

3.A. Speaking | 3.A.1. With mask 3.A.2. Without mask |

| 3.B. Coughing | 3.B.1. With mask 3.B.2. Without mask |

2.4. Grid independence study

The grid independence test for the present study has been carried out by refinement of the study area in the direction of airflow. The test is carried out by considering a domain grid with velocity magnitudes at , . All the points for grid independence study are selected along with the wall patch of the boundaries of the inlet and outlet so that maximum fluctuation can be obtained with all the types of meshing. There is three level of meshing performed depending upon the airflow criterion of the model named as coarse, medium and fine with fine, finer and finest refinement, respectively. The domain with all the requirements selected for the grid independence study can be illustrated in Fig. 6 . The total number of elements produced in all types of meshing is discussed in Table 3 .

Fig. 6.

Domain selected for the grid independence test.

Table 3.

Grid independence study.

| Sr. No. | Mesh type | No. of elements | Average velocity (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Coarse | 126,446 | 0.481 |

| 2 | Medium | 299,686 | 0.488 |

| 3 | Fine | 513,435 | 0.489 |

According to the Richardson extrapolation theory, the refinement ratios must be greater than 1.3 (Roache, 1994).

From Fig. 7 and obtained results, it is confirmed that the convergence has been achieved with different types of mesh types which is a key criterion and basic steps to assure that the simulations performed in this study are correct.

Fig. 7.

Grid independence results for all types of meshing (a) at z = 2.6 (b) at x = 3.9.

2.5. Model assumptions and limitations

The particles produced by speaking and coughing are considered particles with real size distributions without any chemical composition and chemical interaction. Although the current study is based on a simplified and ideal case scenario, it does not consider several affecting factors such as humidity, particles evaporation, and temperature. The validation scenario of the airtight room would be eligible for another flowing pattern. It is important to understand that these are the circumstances under which the modelling and simulations have been done. With the inclusion of all the mentioned environmental and physical factors, the study can improve and the findings will be more accurate. As a result, the current study has certain limitations that may be resolved in future studies. Multiple parameters as indicated above, may be considered and interactions related to those parameters will be studied in detail.

3. Results

Simulations of coughing and speaking personnel have been performed with and without a mask by considering necessary environmental and physical parameters. All the scenarios with boundary conditions used for simulations are mentioned in Table 2. Outcomes of this work explore the fact that aerosol containing deadly SARS-CoV-2 RNA spreads over the entire room under real-life conditions having well enough ventilation and can suspend in the air for a long time. The above fact holds for all the respiratory activities such as coughing and speaking. The particle size (diameter) played an important role in dispersion and has been simulated for varied conditions.

3.1. Validation results

3.1.1. Ventilation

In ventilation validation, the velocity contour of a test case obtained is compared with the result obtained by Han et al. can be seen in Fig. 8 .

Fig. 8.

Comparison of mean velocity contour of Han et al. (2019) with present study.

Fig. 9 presents the OpenFOAM test case results of the velocity profile of this study with the simulation results obtained by Han et al. and the experimental results. The values obtained from the present study fall on a similar track of experimental results. Although the numerical findings on a few points differ from the experimental data, the derived solutions in this study are the closest to the experimental data among those obtained by other researchers. On this basis, it can be said that the room ventilation requirement is met and that the boundary condition can be utilized to simulate airflow with particles.

Fig. 9.

Comparison of velocity profile obtained by present study with Han et al., 2019, Nielsen et al., 2010.

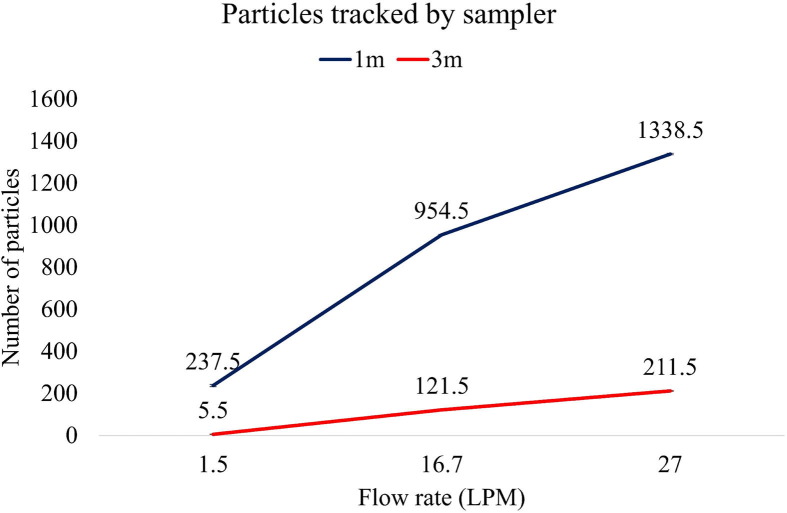

3.1.2. Particle tracking

The results obtained in the present study depicted in Fig. 10 with the spread of aerosol particle in an area is considered for the validation. Figure shows a sampler on which particles are stuck due to suction and due to the circulation of air between the surrounding wall of bed most of the particles are stuck on the walls as well and back wall of the patients. The sampler used for the particle collection was on a vacuum motor with a varying flow rate of 1.5, 16.7 and 27 LPM and was set at 1 m and 3-meter distance from the patient’s head. Due to different flow rates, the number of particles stuck on the sampler is also varying. Fig. 10 illustrates the number of particles received by the sampler with varying flow rates.

Fig. 10.

OpenFOAM results of particles tracking validation.

The particle tracked by the sampler with the corresponding flow rate is shown in Fig. 11 . The number of particles interacting with the sampler increased with the suction capacity of the sampler and it was found to be directly proportional to the volumetric flowrate of the sampler.

Fig. 11.

Graphical representation of particles tracked by sampler.

According to the hospital data, the percentage of particles tracked on a sampler with the current particle tracking sampler used in validation is 100% for all the flow rates when the sampler is kept at a 1-meter distance from the patient’s head end. While for the distance of 3 m, the percentage is found to be 0%, 17% and 50% for the flow rates of 1.5, 16.7 and 27 LPM of the sampler. The present study follows a similar ratio of a varying number of particles with the percentage of people getting an infection at 1 m and 3 m, respectively. It has been concluded that the propagation of particles within the air in a ventilated room is valid.

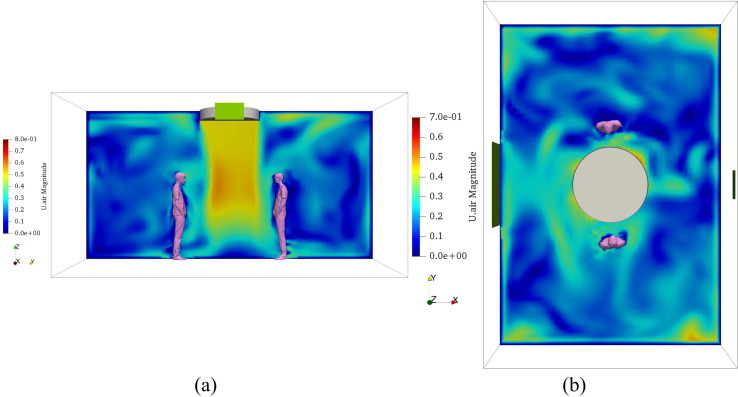

3.2. Velocity profiles

The post-processing tool examines the air velocity profiles produced by artificial thrust sources such as air conditions and fans. The purpose of analyzing air flow profiles within a room is to have a better understanding of particle flow and dispersion within the space under forced draft conditions. The airflow patterns created by an AC patch with an inlet velocity of 0.5 m/s in the positive X and negative Z directions are shown in Fig. 12 . Another airflow profile is examined as a result of the fan patch with a 0.5 m/s inlet velocity along the negative Z direction, as shown in Fig. 13 . On XZ and XY plane slices, velocity profiles are captured.

Fig. 12.

Velocity profiles generated by AC patch (a) along XZ plane (b) along XY plane.

Fig. 13.

Velocity profiles generated by fan patch (a) along YZ plane (b) along XY plane.

3.3. Scenario 1: Room without an air inlet source

Particle emitted by speaking and coughing of an active person is simulated with and without a mask by considering stagnant conditions in the room. All the forces acting on the particles are due to gravity, buoyancy and drag. As there is no air circulation inside the room, the start time of particle injection was set after 10 sec of simulation. Two cases are simulated in each scenario, one is for speaking and the other for coughing. Both the cases have been analyzed with and without putting the mask on the face of an active person. The case is considered with an active man spreading aerosols by the respiratory activities and interacting with a passive man standing over there with no activities with a safe distance of 1.8 m (WHO, 2020b).

Fig. 14 and Fig. 15 illustrated the results of speaking (1.A.) and coughing (1.B.) scenario cases, respectively. A person standing on the left is doing the mentioned respiratory activities and the person on the right is considered idle with no respiratory activity.

Fig. 14.

Speaking particles dispersion in room witout an air inlet source (a) with mask (b) without mask.

Fig. 15.

Coughing particles dispersion in room without an air inlet source (a) with mask (b) without mask.

In the speaking scenario, the dispersion of particles under masked conditions is low compared to without mask (1.A.2.) conditions. The particles under masked (1.A.1) conditions are not travelled for a longer distance as there is no particle found on the front wall, which is 3.8 m apart, while on the side and back wall, few particles can be seen. Without the mask, the dispersion of all sizes of particles can be seen on every wall and ventilation window of the room.

In the coughing scenario, the particles are coming out from the gap between the mask and face having a size range of 0.1 µm to 200 µm and circulated within a room. Without the mask (1.B.2), the dispersion of all sizes of particles can be seen. As there is no air circulation within the room by external sources, very few particles are tracked on the surfaces of the room. The propagation and dispersion of particles (<200 µm) are due to the buoyancy and gravity fields.

3.4. Scenario 2: Room with an AC

Fig. 16 and Fig. 17 showcase the situation that happened in a closed room with AC as an inlet air source with out-airflow ventilation for speaking (2.A.) and coughing (2.B.) scenarios, respectively. The particle dispersion in a room is improved compared to the without ventilation conditions. The AC inlet and ventilation airflow modify the normal pattern of low-velocity particles with a smaller diameter. It accelerates the Brownian movement by increasing the flow vortices (Baron et al., 2001, Jayaweera et al., 2020, Norambuena et al., 2020). The particles of larger diameter (>200 μm) are trapped in a mask, but the particles having a lesser diameter (<200 μm) come out from the gap between the face and mask and are transmitted over the room.

Fig. 16.

Speaking particles dispersion in room with an AC (a) with mask (b) without mask.

Fig. 17.

Coughing particles dispersion in room with an AC (a) with mask (b) without mask.

As the coughing speed is larger than the speaking, the particles under masked conditions are forced to come out from the gap between the mask and face. The particles then propagate with the airfield generated by air conditioning. The particles are found on both the sidewalls, back wall, front wall and ceiling of a room at a distance of 2 m from the active person. The inactive person standing at 1.8 m from the active person is surrounded by the particles, and these particles may contain the SARS-CoV-2 RNA and the person may get infected. Being without mask results in speaking (2.A.2.) and coughing (2.B.2.) cases, it is indicated that if the mask is not worn properly, the particles expelled out from the gap of the mask or shield and face and suspended for a long time and can travel distance with SARS-CoV-2 RNA.

3.5. Scenario 3: Room with a ceiling fan and window

Fig. 18 and Fig. 19 show the results of a comparison of speaking (3.A.) and coughing (3.B.) cases with and without mask, respectively. In the speaking activity, the particles come out from the mask (3.A.1.) in a similar quantity as in Scenario 2. Due to air circulation by the fan installed on the ceiling of a room, air circulation may be equally distributed in all directions, allowing particles to travel in each corner of a room. In the without mask (3.A.2.) condition, the concentration of particles on the surfaces of the room is found to be in similar proportion to having large quantity.

Fig. 18.

Speaking particles dispersion in room with fan (a) with mask (b) without mask.

Fig. 19.

Coughing particles dispersion in room with fan (a) with mask (b) without mask.

In a coughing scenario, the dispersion of particles of all sizes can be seen with mask (3.B.1) and without mask (3.B.2.) conditions. Due to the vortex formation in the centre of both bodies, the particles having lesser diameter did not travel on the other side but dispersed in half of the room and were found on the back and sidewall and ventilation window.

4. Discussion

All scenarios considered in the present study discussed the dispersion and spreading of aerosol particles in various ventilation conditions produced by speaking and coughing. Both the scenarios of speaking and coughing are simulated with respect to with and without mask conditions.

Scenarios are considered based on the need for airflow in a closed room with varied flow conditions for the comfort level of citizens. A scenario is considered in such a way that the room did not have any external inflow in the room and maintained ventilation condition by an outflow window just to analyze the dispersion and tracking of aerosol particles without an inflow. The other scenarios (2 & 3) are considered to maintain the actual requirement of residents in a room such as a fan, window, AC, and ventilation.

The motion of particles in scenario 1 shows the dispersion even with the restricted inflow and travelled with ejection velocities of speaking and coughing within a room and settled on the surfaces quickly compared to other scenarios. However, the number of particles that are coming out from the mask of the active person is low. The ejection of particles in the air circulation environment (scenarios 2 & 3) is forced to come out from the mask due to the airfield generated within a room in addition to the existing emission velocity of speaking and coughing with large numbers as compared to the scenario 1. The particles which are coming out from the mask in the speaking case of each scenario are in the range of 0.1 μm to 20 μm, while in the case of coughing the size range is 0.1 μm to 200 μm.

Fig. 20 and Fig. 21 reveal the comparison of with and without mask conditions in which the particles are found on the room's surfaces (front wall, back wall, sidewall and ventilation window) by speaking and coughing, respectively. In speaking scenarios, the particles are found on a front wall which is 3.8 m away from the active person is higher in scenario 2 compared to scenarios 1 & 3. In the ventilation window which acted as an outflow air patch in all the cases, there is no particle tracked in scenario 1, indicating that poor ventilation conditions i.e., without AC/fan and no inflow of air, stagnant the particles in the air creating a worse scenario for COVID-19 preventions. In the case of speaking, the distribution of particles for mask conditions remained in a ratio similar to without mask conditions for both the cases of ventilation, i.e., using an AC and a fan.

Fig. 20.

Comparison of particles tracked on surfaces of the room with and without mask by speaking activity (a) on front wall (b) on back wall (c) on side walls and (d) on ventilation window.

Fig. 21.

Comparison of particles tracked on surfaces of the room with and without mask by coughing activity (a) on front wall (b) on back wall (c) on side walls and (d) on ventilation window.

In Fig. 21 (coughing scenarios), there are very few particles tracked on the front wall in all scenarios with mask condition but in without mask condition, the quantity of particles is found about 450 in scenario 2 only. Similarly, on the back wall, sidewalls and ventilation window, the particles are found in low numbers (about 2 to 9) with mask conditions in all the scenarios. From all the graphs, it is evident that without a masked person can spread many particles in the ventilated environment and can be more dangerous to the health of others during the pandemic (Bherwani et al., 2021d, Bherwani et al., 2021e, Kaur et al., 2021). Thus, it is indicated that mask conditions are much better and masks should be worn at all times while speaking or coughing. However, it has been observed that the particles coming from the gap of the a mask can also spread to a long-range using air as a medium of transport. Hence it is necessary that proper wearing of mask should inform the citizens so that the particles do not get released from the gap of the mask.

It is observed and supported by the literature that the particle’s dispersion depends on the activities performed by an individual which an active person is doing. The dispersion of particles is found to be different by speaking different words (Silwal et al., 2021). Indoor experiments and numerical simulations are performed to understand the dispersion and travelling of aerosol particles by considering case studies, and they concluded that particles having a small diameter can suspend in the air for a long time (Vuorinen et al., 2020, Shah et al., 2021).

However, the aerosol particles used in this study are artificial solid particles devoid of chemical composition and reaction (inert) that are sized and weighed according to standard ranges. Some environmental conditions, such as temperature and humidity, may influence the particles in real-life situations, which are not considered in our modelling exercise. The current research focuses on particle dispersion and movement inside the room, as well as the effects of various air input sources on particle motion. The findings of this study can dispel any worries about the right usage of a mask and safe distancing. From the findings of this paper, it can be said that the dispersion and spreading of aerosol particles depend upon the ventilation conditions where the active person is standing and doing respiratory activities. This study shows the spread of aerosol particles beyond the current government and WHO guidelines (1.8 m) and can also spread not only along the ejection direction (in straight) but also at a certain height of ceilings and ventilation windows. Many particles have reached the ventilation window (2 m); thereafter they can spread in the outer environment causing dilution. The findings of the study indicate that the safe distancing norms are to be created based on ventilation conditions and cannot be generalized to 1.8 m which is the crux of the study; however, in the present context we have not simulated various scenarios which can tell what safe distances are to be followed and at what conditions and detail study may be required in that case. As a result, the dispersion of particles varied with the air inflow and outflow conditions which may further vary in transport, supermarkets, cinema theatres, etc., where people are used to gathering in a large quantities.

5. Conclusion

The present work used CFD modelling to investigate the transport and scattering of particles of various sizes (0.1 to 200 μm and 0.1 to 1000 μm) that occur when a person speaks and coughs. The process of injecting particles into the indoor environment by an active person was used to simulate a realistic process of speaking and coughing with velocities of 3.22 m/s and 20 m/s, respectively. Validation is carried out to satisfy the room ventilation condition with an inlet airflow over the room and is found in a good manner with the experimental data and simulation results. Hence the modelling setup can be considered useful for generating other scenarios. Another validation on particles tracking with airflow conditions according to distance mentioned in the literature has been performed to make sure that dispersion and propagation of particles with air considered for the simulation of the present study fall in the correct manner.

Computational studies of the transport and distribution of particles have been performed during speaking and coughing in a closed room with various ventilation conditions. In without mask scenarios of all the ventilation conditions, it is noted that the particles having larger size fell on a body and transported over short distances and the particles having smaller size propagated over long distances. It should also be noted that the person speaking only for 5 min without the mask is enough to spread the large number of particles containing deadly SARS Co-V-2 RNA. By considering active and inactive persons with masks, the spread of particles without ventilation conditions (no external airflow in a room) is quite enough to spread the infection, but it is not possible to have zero ventilation in a closed room with the presence of humans. In an AC room with a ventilation window, the dispersion of the particles is found in the entire room even after wearing a mask. Spreads of small size particles (0.1–20 μm for speaking and 0.1–200 μm for coughing) have occurred in all directions and are detected on the walls and the ceiling of the room. In the case of a room with a fan, window for inlet airflow, and ventilation window for outflow of air, the particles' dispersion quantity is in similar quantity as that of an AC room, but the area confined by the particles is approximately half. Due to the maximum vortices formed with a fan inlet patch and an air window, the low size particles are restricted to travel over an area where an active person is standing.

One of the primary problems due to the prevalence of COVID-19 in most regions of the world is the correlation between environmental parameters such as rising air temperatures and the rapid spread of coronavirus. The studies stated that the maximum relative humidity, maximum temperature, and wind speed could be responsible for the spreading of the coronavirus, while some of the studies also stated that with increasing temperature, the spreading of coronavirus disease has decreased. A WHO article also mentioned that the low pH, sunlight, and heat make it easier to kill the coronavirus. Although there is no direct relation between the environmental factors that one can say increasing temperature results in an increase in positive cases, there may be an impact of environmental factors on the spreading of the virus. Outdoor and microclimatic modelling with environmental factors has been carried out in several studies (Bherwani et al., 2021b, Mirza et al., 2021, Bherwani et al., 2021c) by creating correlation between outdoor environmental factors and indoor ventilation conditions, which are used in the existing study can establish the better platform to understand the spreading of coronavirus (Bherwani et al., 2020b). However, we have not considered discussed interaction in our study, which becomes a part of future studies.

Based on various assumptions considered for the study, the recommended safe distance of 6 feet (2 m) may not be reliable at all times. Exploratory analysis suggests that even 3.8 m of physical distancing may not avoid virus load completely under generic indoor conditions. The outcomes should be useful for the development of better physical distancing norms and ventilation guidelines for different indoor environments. The observed findings show that the recommended distances should be amended based on significant characteristics, including masks, location, air inlet sources, and environmental conditions. It is suggested that the outcomes of this study can be used to simulate aerosol dispersion in transport (car, bus, train, flight, etc.), offices, stores, theatres and malls with the maximum capacity of the people gathering and modification should be done on COVID-19 guidelines. A separate guideline should be implemented depending on the number of people for the places. However, according to WHO rules, this distance is between 1 and 2 m.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shahid Mirza: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software. Amol Niwalkar: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Visualization. Ankit Gupta: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft. Sneha Gautam: Visualization, Writing – original draft. Avneesh Anshul: Visualization, Validation. Hemant Bherwani: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Project Administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Rajesh Biniwale: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Rakesh Kumar: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Aldila D., Khoshnaw S.H., Safitri E., Anwar Y.R., Bakry A.R., Samiadji B.M., Anugerah D.A., Gh M.F.A., Ayulani I.D., Salim S.N. A mathematical study on the spread of COVID-19 considering social distancing and rapid assessment: The case of Jakarta, Indonesia. Chaos, Solit. Fract. 2020;139:110042. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliabadi A.A., Rogak S.N., Green S.I., Bartlett K.H. January. CFD simulation of human coughs and sneezes: a study in particles dispersion, heat, and mass transfer. In ASME Inter. Mech. Engi. Cong. Expo. 2010;44441:1051–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Asadi S., Wexler A.S., Cappa C.D., Barreda S., Bouvier N.M., Ristenpart W.D. Aerosol emission and superemission during human speech increase with voice loudness. Scient. Rep. 2019;9(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-38808-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron P.A., Sorensen C.M., Brockmann J.E. Nonspherical particle measurements: shape factors, fractals, and fibers. Aerosol. Measure.: Principles, Tech. Appl. 2001:705–749. [Google Scholar]

- Bherwani H., Anjum S., Gupta A., Singh A., Kumar R. Establishing influence of morphological aspects on microclimatic conditions through GIS-assisted mathematical modeling and field observations. Environ., Dev. Sustain. 2021:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bherwani H., Anjum S., Kumar S., Gautam S., Gupta A., Kumbhare H., Anshul A., Kumar R. Understanding COVID-19 transmission through Bayesian probabilistic modeling and GIS-based Voronoi approach: a policy perspective. Env., Develop. Sust. 2021;23(4):5846–5864. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00849-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bherwani H., Gautam S., Gupta A. Qualitative and quantitative analyses of impact of COVID-19 on sustainable development goals (SDGs) in Indian subcontinent with a focus on air quality. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021;18(4):1019–1028. doi: 10.1007/s13762-020-03122-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bherwani H., Gupta A., Anjum S., Anshul A., Kumar R. Exploring dependence of COVID-19 on environmental factors and spread prediction in India. NPJ Clim. Atm. Sci. 2020;3(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bherwani H., Indorkar T., Sangamnere R., Gupta A., Anshul A., Nair M.M., Singh A., Kumar R. Investigation of Adoption and Cognizance of Urban Green Spaces in India: Post COVID-19 Scenarios. Current Res. Environ. Sustain. 2021;3:100088. [Google Scholar]

- Bherwani H., Kumar S., Musugu K., Nair M., Gautam S., Gupta A., Ho C.H., Anshul A., Kumar R. Assessment and valuation of health impacts of fine particulate matter during COVID-19 lockdown: a comprehensive study of tropical and sub tropical countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021;28(32):44522–44537. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-13813-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bherwani H., Nair M., Musugu K., Gautam S., Gupta A., Kapley A., Kumar R. Valuation of air pollution externalities: comparative assessment of economic damage and emission reduction under COVID-19 lockdown. Air Qual. Atmos. Health. 2020;13(6):683–694. doi: 10.1007/s11869-020-00845-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bherwani H., Singh A., Kumar R. Assessment methods of urban microclimate and its parameters: A critical review to take the research from lab to land. Urban Clim. 2020;34:100690. [Google Scholar]

- Busco G., Yang S.R., Seo J., Hassan Y.A. Sneezing and asymptomatic virus transmission. Phys. Fluids. 2020;32(7):073309. doi: 10.1063/5.0019090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao C.Y.H., Wan M.P., Morawska L., Johnson G.R., Ristovski Z.D., Hargreaves M., Mengersen K., Corbett S., Li Y., Xie X., Katoshevski D. Characterization of expiration air jets and particles size distributions immediately at the mouth opening. J. Aero. Sci. 2009;40(2):122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jaerosci.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Zhao B. Some questions on dispersion of human exhaled particles in ventilation room: answers from numerical investigation. Indoor Air. 2010;20(2):95–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2009.00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey A., Kotnala G., Mandal T.K., Sonkar S.C., Singh V.K., Guru S.A., Bansal A., Irungbam M., Husain F., Goswami B., Kotnala R.K. Evidence of the presence of SARS-CoV-2 virus in atmospheric air and surfaces of a dedicated COVID hospital. J. Med. Viro. 2021 doi: 10.1002/jmv.27029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudalski N., Mohamed A., Mubareka S., Bi R., Zhang C., Savory E. Experimental investigation of far-field human cough airflows from healthy and influenza-infected subjects. Indoor Air. 2020;30(5):966–977. doi: 10.1111/ina.12680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duguid J.P. The numbers and sites of origin of the particles expelled during expiratory activities. Edinb. Med. J. 1945;52:385–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duguid J.P. The size and the duration of aircarriage of respiratory particles and particles-nuclei. J. Hyg. 1946;44:471–479. doi: 10.1017/S0022172400019288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian P., Milton D., Angel M., Perez D., McDevitt J. Influenza virus aerosols in human exhaled breath: Particle size, culturability, and effect of surgical masks. Epidemiology. 2011;22(1):S51. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Marchal T., Sperry T., Yi H. Influence of wind and relative humidity on the social distancing effectiveness to prevent COVID-19 airborne transmission: A numerical study. J. Aero. Sci. 2020;147:105585. doi: 10.1016/j.jaerosci.2020.105585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennelly K.P., Martyny J.W., Fulton K.E., Orme I.M., Cave D.M., Heifets L.B. Cough-generated aerosols of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a new method to study infectiousness. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004;169:604–609. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1101OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao N.P., Niu J.L. Modeling particle dispersion and deposition in indoor environments. Atmo. Enviro. 2007;41(18):3862–3876. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerone P.J., Couch R.B., Keefer G.V., Douglas R.G., Derrenba E.B., Knight V. Assessment of experimental and natural viral aerosols. Bacteriol. Rev. 1966;30:576–588. doi: 10.1128/br.30.3.576-588.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gralton J., Tovey E., McLaws M.L., Rawlinson W.D. The role of particle size in aerosolised pathogen transmission: a review. J. Infec. 2011;62(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y., Ramesh A., Memarzadeh F. The effects of patient movement on particles dispersed by coughing in an indoor environment. App. Bio. 2014;19(4):172–183. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta Ankit, Bherwani Hemant, Gautam Sneha, Anjum Saima, Musugu Kavya, Kumar Narendra, Anshul Avneesh, Kumar Rakesh. Air pollution aggravating COVID-19 lethality? Exploration in Asian cities using statistical models. Enviro., Devel. Sust. 2021;23(4):6408–6417. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00878-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, M.I., 2020. Bioaerosol size effect in COVID-19 transmission.

- Han M., Ooka R., Kikumoto H. Lattice Boltzmann method-based large-eddy simulation of indoor isothermal airflow. Inter. Jour. Heat Mass Tran. 2019;130:700–709. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan A. Tracking the flu virus in a room mechanical ventilation using CFD tools and effective disinfection of an HVAC system. Inter. Jour. Air-Conditi. Refri. 2020;28(02):2050019. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S., Oosthuizen P.H. Validation of numerical modeling of conditions in an atrium space with a hybrid ventilation system. Build. Envi. 2012;52:152–161. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S., Oosthuizen P.H., Kalendar A. Evaluation of various turbulence models for the prediction of the airflow and temperature distributions in atria. Ene. Build. 2012;48:18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Issakhov A., Alimbek A., Issakhov A. A numerical study for the assessment of air pollutant dispersion with chemical reactions from a thermal power plant. Eng. Appl. Compu. Fluid Mech. 2020;14(1):1035–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Issakhov A., Alimbek A., Zhandaulet Y. The assessment of water pollution by chemical reaction products from the activities of industrial facilities: Numerical study. Jou. Clean. Prod. 2021;282:125239. [Google Scholar]

- Issakhov A., Zhandaulet Y., Omarova P., Alimbek A., Borsikbayeva A., Mustafayeva A. A numerical assessment of social distancing of preventing airborne transmission of COVID-19 during different breathing and coughing processes. Scient. Rep. 2021;11(1):1–39. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88645-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaweera M., Perera H., Gunawardana B., Manatunge J. Transmission of COVID-19 virus by particles and aerosols: A critical review on the unresolved dichotomy. Environ. Res. 2020;188:109819. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G.R., Morawska L. The mechanism of breath aerosol formation. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 2009;22:229–237. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2008.0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones W.P., Launder B.E. The prediction of laminarization with a two-equation model of turbulence. Intern. Jou. Heat Mass Trans. 1972;15(2):301–314. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S., Bherwani H., Gulia S., Vijay R., Kumar R. Understanding COVID-19 transmission, health impacts and mitigation: timely social distancing is the key. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021;23(5):6681–6697. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00884-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H., Azad A., Gupta A., Sharma J., Bherwani H., Labhsetwar N.K., Kumar R. COVID-19 Creating another problem? Sustainable solution for PPE disposal through LCA approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021;23(6):9418–9432. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-01033-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon S.B., Park J., Jang J., Cho Y., Park D.S., Kim C., Bae G.N., Jang A. Study on the initial velocity distribution of exhaled air from coughing and speaking. Chemosphere. 2012;87(11):1260–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley W.G., Blachere F.M., Thewlis R.E., Vishnu A., Davis K.A., Cao G., Palmer J.E., Clark K.E., Fisher M.A., Khakoo R., Beezhold D.H. Measurements of airborne influenza virus in aerosol particles from human coughs. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11):e15100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löhner R., Antil H., Idelsohn S., Oñate E. Detailed simulation of viral propagation in the built environment. Compu. Mech. 2020;66(5):1093–1107. doi: 10.1007/s00466-020-01881-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loudon R.G., Roberts R.M. Particles expulsion from respiratory tract. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1967;95:435–442. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1967.95.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menter, F.R., Kuntz, M., 2003. Development and Application of a Zonal DES Turbulence Model for CFX-5. CFX-Validation Report, CFX-VAL, 17, p. 0503.

- Menter F.R. Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA J. 1994;32(8):1598–1605. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, S., Niwalkar, A., Anjum, S., Bherwani, H., Singh, A., Kumar, R., 2021. Integrated Assessment of Urban Microclimate Parameters Using Open Foam. Vidyabharati International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (Special Issue 2021), ISSN 2319-4979.

- Morawska L. Particles fate in indoor environments, or can we prevent the spread of infection? Indoor Air. 2006;16(5):335–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2006.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair M., Bherwani H., Mirza S., Anjum S., Kumar R. Valuing burden of premature mortality attributable to air pollution in major million-plus non-attainment cities of India. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02232-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, P.V., Rong, L., Cortes, I.O., 2010. The iea annex 20 two-dimensional benchmark test for cfd predictions. In: Clima 2010: 10th Rehva World Congress: Sustainable Energy Use in Buildings. Clima 2010: 10th Rehva World Congress.

- Norambuena A., Valencia F.J., Guzmán-Lastra F. Understanding contagion dynamics through microscopic processes in active Brownian particles. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77860-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Openfoam, 2014, https://openfoam.org/release/2-3-0/dpm/ (assessed on 05 August 2021).

- Qian M., Jiang J. COVID-19 and social distancing. Jour. Pub. Hea. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s10389-020-01321-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roache, P.J., 1994. Perspective: a method for uniform reporting of grid refinement studies.

- Shah Y., Kurelek J.W., Peterson S.D., Yarusevych S. Experimental investigation of indoor aerosol dispersion and accumulation in the context of COVID-19: Effects of masks and ventilation. Phys. Fluids. 2021;33(7):073315. doi: 10.1063/5.0057100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silwal L., Bhatt S.P., Raghav V. Experimental characterization of speech aerosol dispersion dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83298-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalart, P.R., 1997. Comments on the feasibility of LES for wings, and on hybrid RANS/LES approach, advances in DNS/LES. In Proceedings of 1st AFOSR Inter. Confer. on DNS/LES.

- Stamou A., Katsiris I. Verification of a CFD model for indoor airflow and heat transfer. Build. Envir. 2006;41(9):1171–1181. [Google Scholar]

- Sun W., Ji J. Transport of particles expelled by coughing in ventilated rooms. Indoor Built. Envi. 2007;16(6):493–504. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur V., Jain A. COVID 2019-suicides: A global psychological pandemic. Brain, Behavior, Immune. 2020;88:952. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- To K.K.W., Tsang O.T.Y., Leung W.S., Tam A.R., Wu T.C., Lung D.C., Yip C.C.Y., Cai J.P., Chan J.M.C., Chik T.S.H., Lau D.P.L. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2020;20(5):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuorinen V., Aarnio M., Alava M., Alopaeus V., Atanasova N., Auvinen M., Balasubramanian N., Bordbar H., Erästö P., Grande R., Hayward N. Modelling aerosol transport and virus exposure with numerical simulations in relation to SARS-CoV-2 transmission by inhalation indoors. Safety Sci. 2020;130:104866. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Du G. COVID-19 may transmit through aerosol. Irish J. Med. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11845-020-02218-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wathore R., Gupta A., Bherwani H., Labhasetwar N. Understanding air and water borne transmission and survival of coronavirus: Insights and way forward for SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Total Envir. 2020;749:141486. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J., Li Y. Enhanced spread of expiratory particles by turbulence in a cough jet. Build. Envi. 2015;93:86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wells W.F. On air-borne infection. Study II. Particles and particles nuclei. Am. Jour. Hygi. 1934;20:611–618. [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2020a. Report of the who-China joint mission on coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19). Tech. Rep., World Health Organization.

- WHO, W., 2020b. COVID-19 strategy update. Geneve, Schweiz.

- Xie X., Li Y., Sun H., Liu L. Exhaled particles due to talking and coughing. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2009;6:S703–S714. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0388.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Shang Y., Tian L., Weng W., Tu J. A numerical study on firefighter nasal airway dosimetry of smoke particles from a realistic composite deck fire. Jour. Aero. Sci. 2018;123:91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Yang S., Lee G.W.M., Chen C.-M., Wu C.-C., Yu K.-P. The size and concentration of particles generated by coughing in human subjects. J. Aerosol. Med. 2007;20:484–494. doi: 10.1089/jam.2007.0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Li D., Xie L., Xiao Y. Documentary research of human respiratory particles characteristics. Proc. Engi. 2015;121:1365–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Lee K., Chen Q. A simplified approach to describe complex diffusers in displacement ventilation for CFD simulations. Indoor Air. 2009;19(3):255–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2009.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Feng G., Bi Y., Cai Y., Zhang Z., Cao G. Distribution of particles aerosols generated by mouth coughing and nose breathing in an air-conditioned room. Sustai. Cities Soc. 2019;51:101721. [Google Scholar]