Abstract

Objectives

Early diagnosis and reducing the time taken to achieve each step of lung cancer care is essential. This scoping review aimed to examine time points and intervals used to measure timeliness and to critically assess how they are defined by existing studies of the care seeking pathway for lung cancer.

Methods

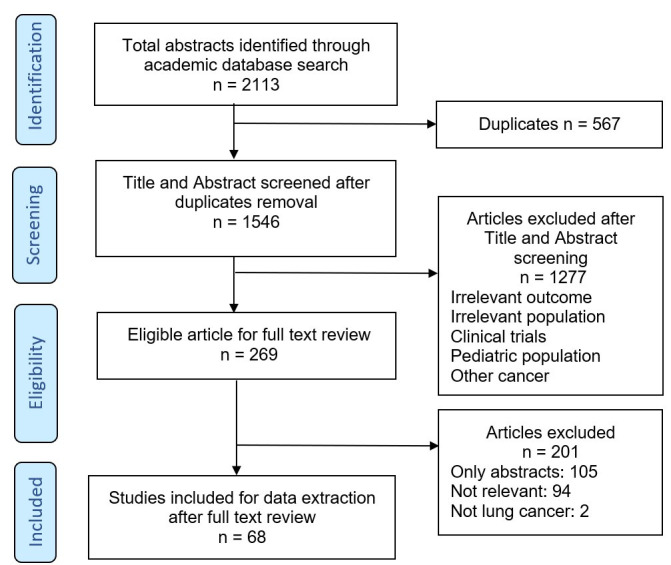

This scoping review was guided by the methodological framework for scoping reviews by Arksey and O’Malley. MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and PsycINFO electronic databases were searched for articles published between 1999 and 2019. After duplicate removal, all publications went through title and abstract screening followed by full text review and inclusion of articles in the review against the selection criteria. A narrative synthesis describes the time points, intervals and measurement guidelines used by the included articles.

Results

A total of 2113 articles were identified from the initial search. Finally, 68 articles were included for data charting process. Eight time points and 14 intervals were identified as the most common events researched by the articles. Eighteen different lung cancer care guidelines were used to benchmark intervals in the included articles; all were developed in Western countries. The British Thoracic Society guideline was the most frequently used guideline (20%). Western guidelines were used by the studies in Asian countries despite differences in the health system structure.

Conclusion

This review identified substantial variations in definitions of some of the intervals used to describe timeliness of care for lung cancer. The differences in healthcare delivery systems of Asian and Western countries, and between high-income countries and low-income-middle-income countries may suggest different sets of time points and intervals need to be developed.

Keywords: Respiratory tract tumours, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE, PRIMARY CARE, PUBLIC HEALTH, RESPIRATORY MEDICINE (see Thoracic Medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This scoping review documented the commonly studied time points in the lung cancer care pathway and the heterogeneity in naming the intervals and, guidelines adopted in the disease care pathway for lung cancer across different studies.

Arksey and O’Malley’s five-stage scoping review framework and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist was followed for this scoping review.

This study was informed by a previously published protocol which dictated a transparent and rigorous search strategy for four databases.

Quality of studies was not assessed.

Only studies published in English were included in the review, which may miss potential literature in other languages.

Background

Lung cancer is the most common cancer, with an incidence of 2.1 million globally during 2018, and is the most frequent cause of deaths in both sexes in 14 regions of the world.1 Incidence and mortality vary across countries due to differences in smoking prevalence and other risk factors, but overall survival rates are low globally (5 year survival of 10%–20% in most countries) with most patients diagnosed at an advanced stage.1

Timely diagnosis and access to effective treatment are important determinants of outcome in patients with cancer.2 Higher cancer survival rates are evident in high performing healthcare systems. For example, patients with lung cancer in Japan (33%), Israel (27%) and Korea (25%) have a much higher 5-year survival rate than their counterparts in India, Thailand, Brazil and Bulgaria (all less than 10%).3 Early diagnosis can improve survival and reduce lung cancer mortality through timely initiation of treatment.4

Numerous studies have been conducted to assess timeliness of initiation and completion of cancer treatment. However, the pathway to cancer diagnosis and treatment is complex.5 The patient journey from onset of symptoms to initiation of treatment involves multiple stages, which vary significantly across different health systems,6 with different health systems having different ‘bottlenecks’ in the patient journey.

The patient journey can be categorised into different care time points. Time points are the landmarks or events that take place in a patient journey to healthcare, for example, onset of symptom(s), contact with a healthcare provider, referral, diagnosis, initiation of treatment, and so on. Depending on the outcome of interest of a research or intervention, intervals are defined by calculating the time between two agreed time points. Timeliness can be defined as reaching different time points of care in a way that supports the best patient outcomes. It usually starts from the date of onset of symptoms and ends at the date of initiation of treatment. Guidelines can be defined as a set of agreed recommendation that aim to streamline the process in each step of the disease care pathway to set routine or standard clinical practice. In some countries, clinical guidelines have been developed to establish a maximal length requirement for the intervals between different time points to ensure optimal patient care outcomes. These have enabled measurement of delay. However, studies describing time intervals often mislabeled these intervals as ‘delays’ despite a lack of benchmarking, creating confusion among readers. There are also marked variations in the definitions of these intervals across studies, and in how the data were obtained, measured and presented.7 This ambiguity leads readers to make assumptions about the interpretation of the terms and findings. Moreover, due to differences in health systems, studies are seldom comparable across countries.6 Referral pathways vary between countries. For example, in some developing countries, all the diagnostic tests required to diagnose a cancer are completed before a patient is referred to a specialist, thus contributing to variation in the definition and length of the diagnostic segment in the care pathway between such developing countries and the developed country which was the source of the guidance.

Existing guidelines for lung cancer care vary in the benchmarks or cut-off values used to describe acceptable limits of time for each step in the disease care pathway. As a result, definitions and measures of ‘timeliness of care’ vary across countries. Furthermore, the majority of guidelines were developed in Western countries, considering country-specific resources and healthcare mechanisms, and associated with effective referral systems governed by policies.8 It is unlikely that guidelines developed for Western health systems can be fully effective in poorly resourced health systems,8 9 which require different definitions, measurements and guidelines for timely care compatible with their available resources and the strength of their health systems.10

Several models were proposed in an attempt to improve consistency in the definition, classification and measurement of timeliness of care, but the models are not devoid of limitations. These include the Andersen model of total patient delay,11 the model of pathways to treatment12 and the Aarhus statement.6 Andersen’s model can capture the decisional and behavioural processes that occur before the initiation of treatment, but is limited in its capacity to address the complex and dynamic journey into and through the healthcare system.12 The subsequently proposed ‘Model of pathways to treatment’ is a descriptive framework which can encompass the psychological theories with a focus on patient factors in the appraisal and help-seeking intervals. The most recent and widely accepted framework, ‘The Aarhus Statement,’13 proposes a universal framework to incorporate the issue of lack of consensus in definitions and methods across studies conducted on timeliness of cancer care. It defines four important time points that links different interval durations with patient outcomes to determine targets and guidelines (date of first symptom, date of first presentation to a general practitioner (GP), date of referral and date of diagnosis). It also provides guidance on how to design research with greater precision and transparency. All these models provide an overarching framework that can be adapted to different system contexts. This scoping review aimed to examine time points and intervals used to measure timeliness and to critically assess and compare how they are defined by existing studies of the care seeking pathway for lung cancer.

Methods

This scoping review followed the methodological framework for scoping reviews by Arksey and O’Malley14 which was further enhanced by Levac et al15 and the Joanna Briggs Institute.16 Stages of the scoping review framework included (1) Identifying the research question, (2) Identifying relevant studies, (3) Study selection, (4) Charting the data and (5) Collating, summarising, and reporting the results. The University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidance for undertaking reviews in health care17 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist18 were followed to ensure the comprehensiveness of the review. This scoping review categorised available definitions and terminologies relating to timeliness in the disease care pathway, without an intention of achieving consensus.

Identifying the research question

To address the aim of assessing definitions describing timeliness of seeking and receiving care in patients with lung cancer in published articles, the following research questions were posed:

What are the time points and intervals commonly identified in the care pathway for lung cancer in the existing literature?

How is timeliness of seeking and receiving care for lung cancer described and related to guidelines in the existing literature?

Are there differences in definitions, measurements and benchmarking of timeliness used in Western and Asian countries?

Identifying relevant studies

The study population of included literature was patients with diagnosed lung cancer, irrespective of histological type and disease stage. Studies were identified through the keywords that were used to describe timeliness of seeking care, time points in seeking care and intervals between time points in the disease care pathway. Studies were excluded if timeliness of care or time points and intervals in the care pathway were ambiguous, were not specific for lung cancer, if the primary focus of the article was not timeliness of care, if the articles were not published in English, or if studies were published only as abstracts. This scoping review included all studies, irrespective of study methodology, quality and publication type to gain a better understanding of how researchers have operationalised and measured timeliness of seeking and receiving care for lung cancer in various study settings between May 1999 and May 2019.

The text contained in the titles and abstracts of the papers from the initial search and the keywords used to describe those articles were used to formulate the search strategies specific to the selected databases. MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and CINAHL were searched for published articles. An academic health sciences librarian was consulted on selecting the appropriate keywords and the most appropriate MeSH terms and filters to maximise inclusion of articles within the search, and how to modify them for selected bibliographic databases (full search strategy in online supplemental file 1). Reference lists were screened for relevant articles. Search results were imported into EndNote (V.X9) to organise search results specific to each database and later used to generate the reference list for the review. References were imported to Covidence, which was used for documenting the process including duplicate identification and removal, title and abstract screening, and full-text review for included articles. Detailed keywords mapping and database specific search strategies were published in the protocol of this scoping review.19

bmjopen-2021-056895supp001.pdf (34.1KB, pdf)

Study selection

Selection of publications involved two stages. First, title and abstract were screened against the inclusion criteria, and second, the potentially relevant papers went through full-text review. To increase the reliability of the decision process all selected papers were independently assessed by at least two researchers. Due to the exploratory nature of this scoping review, a detailed methodological quality assessment was not required.20 One author (AA) performed a search of the electronic database for literature. Two authors (AA and AR) independently reviewed and screened the abstracts of the searched articles for inclusion. The other two authors (VL and CFM) reviewed the disagreements and resolved by discussion with all the authors.

Data charting, collating and summarising

A data extraction chart was used to capture the data from selected articles (online supplemental file 2), which was recorded on Microsoft Excel 365. Data were extracted by AA independently and examined by authors (VL, CL, CFM and AR).

bmjopen-2021-056895supp002.pdf (341.6KB, pdf)

Initially a coding tree was constructed which had three levels: time points as the first level, time intervals (with starting and ending time point) as the second level, and timeliness (with a definition or benchmarking) as the third level. The initial coding tree was further expanded and divided when new categories emerged from data. An exhaustive list of time points related to seeking or receiving care on the patient care journey was extracted through comparing and merging similar terminologies. The sequence of the time points was determined as follows, (1) patient recalled onset of symptoms, (2) first contact with a healthcare provider, (3) diagnosis, (4) referral to a specialist, (5) first visit to a specialist/hospital admission, (6) patient informed about diagnosis, (7) pre-initiation of treatment, and (8) initiation of treatment. Afterwards, we summarised and charted the type of intervals examined in the included studies. Intervals in the lung cancer patient care pathway considered the duration between one time point and another time point. Relevant definitions or measurements in relation to the three level coding themes (time points, intervals and timeliness) were also extracted with or without further verification from the cited guidelines. The data on definition of interval or delay were extracted when an article explicitly mentioned the guiding principle (cancer care guideline or self-definition) which included researcher/study constructed definitions as well. Comparisons between Asian and Western countries were based on the similarities or differences in using time points, intervals and measurement of timelines for intervals.

Results

A total of 2113 articles were identified from the initial search. After duplicates removal, 1546 articles were screened for eligibility and 269 articles were selected for full-text review. Two hundred and one articles were excluded because they were not relevant, only published as abstract or not related to lung cancer. Finally, 68 articles were included for the data charting process (figure 1). Characteristics of the included articles are given in table 1 (review articles were excluded).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included articles

| N=68 | Characteristics of included articles | N (%) |

| Year of publication | 2001–2010 2011–2018 |

25 (37) 43 (63) |

| Study setting* | North America (USA, Canada) | 21 (30.88) |

| UK (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) | 15 (22.06) | |

| Europe (Denmark, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Italy, Sweden, France, Poland, Finland) | 13 (19.12) | |

| Asia (Turkey, India, Mainland China, Taiwan, Nepal) | 9 (13.24) | |

| Australia and New Zealand | 8 (11.76) | |

| Study design | Cross-sectional Other study designs Cohort Case control Systematic review Scoping review |

41 (60.83) 13 (19.1) 9 (13.2) 3 (4.4) 1 (1.5) 1 (1.5) |

| Sample size | Range All studies total |

12–1 71 208 280 591 |

*Review papers not counted in study settings and sample size.

Time points

Based on the selected articles, time points were classified and the sequence was determined into eight categories (table 2). Commonly mentioned time points included onset of symptom(s), first contact with healthcare provider, diagnosis/first suspicious investigation result, referral/receipt of referral by a specialist (at secondary care), first visit to a specialist/hospital admission, patient informed of lung cancer diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

Table 2.

Time points in the lung cancer care pathway

| Time points | Articles | Definition of time point | Settings |

| Onset of symptoms | Baughan et al UK80 | Date patient first noticed symptoms | UK |

| Corner et al UK94 | The date, week, or month when a symptom or health change was recalled, and actions taken as a result by the patient were recorded as well as a description of the health change or symptom | ||

| Dobson et al UK95 | The date of symptom onset was defined as the first symptom reported | ||

| Melling et al UK84 | First symptom reported by the patients to their GPs | ||

| Neal et al UK96 | Onset of first symptom | ||

| Smith et al Scotland97 | The date participant defined first symptom | ||

| Salomaa et al Finland21 | The dates of onset of symptoms | Europe | |

| Yang et al Mainland China98 | First symptom | Asia | |

| Yilmaz et al Turkey27 | Date of initial symptoms | ||

| Özlü et al Turkey69 | Onset of symptoms | ||

| First contact with healthcare provider | Baughan et al UK80 | Date patient of first presentation with a GP | UK |

| Corner et al UK94 | Timing of first visit to the GP | ||

| Dobson et al UK95 | Date on which person consulted a GP about their symptoms. | ||

| Smith et al Scotland97 | Date of presentation to a medical practitioner | ||

| Melling et al UK84 | Presentation of the first cancer symptom to the GP | ||

| Neal et al UK96 | First presentation (Face-to-face consultations, nurse consultations, telephone consultations) to primary care | ||

| Vidaver et al USA68 | First visit to primary healthcare provider | North America | |

| Helsper et al 2017 Netherlands30 | First contact (physical or telephone) with the GP for suspected cancer-related signs or symptoms | Europe | |

| Salomaa et al Finland21 | First visit to a doctor, who was in general, a GP | ||

| Rankin et al Australia32 | First consultation with primary healthcare provider | Australia and New Zealand | |

| Largey et al Australia99 | Dates of first presentation as the time point the clinician started investigation or referral for possible investigation | ||

| Yang et al Mainland China98 | First contact with local doctor | Asia | |

| Yilmaz et al Turkey27 | Date of first doctor visit | ||

| Özlü et al Turkey69 | First presentation to a physician | ||

| Diagnosis/first suspicious investigation result | Corner et al UK94 | Date of diagnosis (the investigation procedure was not specified) | UK |

| Neal et al UK96 | Date of diagnosis (CT/PET scan, a tissue diagnosis) | ||

| Melling et al UK84 | Date of Diagnosis (bronchoscopy, mediastionsocopy, CT scan, bone scan, plural cytology) | ||

| Vidaver et al USA68 | First imaging result with a lung abnormality | North America | |

| Singh et al USA65 | Earliest date that a diagnostic clue could have been recognised by a care provider | ||

| Li et al Canada100 | Date of diagnosis | ||

| Maiga et al USA42 | Date of pathology diagnosis | ||

| Schultz et al USA70 | Date when a pathologic diagnosis of lung cancer was confirmed | ||

| Grunfeld et al Canada83 | Date of confirmed diagnosis (date of the pathology or radiology report) | ||

| Helsper et al Netherlands30 | Date of the histological confirmation of the primary tumour | Europe | |

| Rankin et al Australia32 | Time of the formal cancer diagnosis being made | Australia and New Zealand | |

| Largey et al Australia99 | Date of histological diagnosis | ||

| Malalasekera et al 2018 Australia33 | First suspicious investigation report (the investigation procedure was not specified) | ||

| Özlü et al Turkey69 | Date of histopathological diagnosis | Asia | |

| Yang et al Mainland China22 | Date of diagnosis (CT scan and biopsy) | ||

| Yilmaz et al Turkey27 | Date of diagnosis | ||

| Referral to a specialist/receipt of referral by a specialist or thoracic department | Baughan et al UK80 | Date of decision to refer by primary care | UK |

| Melling et al UK84 | Date of referral to secondary care | ||

| Neal et al UK96 | Date of GP referral to specialist or admission to hospital | ||

| Grunfeld et al Canada83 | Referral for diagnostic assessment was received by the consultant | North America | |

| Vidaver et al USA68 | Date of referral to a specialist | ||

| Helsper et al Netherlands30 | The time point when the responsibility for the patient was transferred from a GP to secondary care | Europe | |

| Salomaa et al Finland21 | The date of the writing of the referral requesting consultation from a specialist | ||

| Stokstad et al Norway87 | A referral letter for suspected lung cancer was received by the Department of Thoracic Medicine | ||

| Largey et al Australia99 | Date of referral by primary healthcare provider | Australia and New Zealand | |

| Malalasekera et al Australia33 | Date of first referral to secondary care | ||

| Yang et al Mainland China22 | Date of referral to hospital from primary physician | Asia | |

| First visit to a specialist/ Hospital admission | Baughan et al UK80 | Date patient first seen by specialist | UK |

| Vidaver et al USA68 | First visit to a specialist | North America | |

| Salomaa et al Finland21 | The first appointment with the specialist | Europe | |

| Largey et al Australia99 | First specialist visit | Australia and New Zealand | |

| Malalasekera et al 2018 Australia33 | First specialist visit | ||

| Alexander et al 2016 Australia76 | Date of first medical oncology or haematology review for patients with an urgent presentation | ||

| Yilmaz et al 2008 Turkey27 | Date of admission to pneumology department | Asia | |

| Patient informed of the cancer diagnosis | Baughan et al 2009 UK80 | Date patient told the diagnosis | UK |

| Grunfeld et al 2009 Canada83 | Date patient informed of diagnosis | North America | |

| Vidaver et al 2016 USA68 | Date patient informed of the biopsy result | ||

| Pre-initiation of treatment | Maiga et al USA42 |

|

North America |

| Initiation of treatment | Melling et al UK84 | Date treatment started (surgery, radical radiotherapy with chemotherapy). | UK |

| Li et al Canada100 | Date of first treatment, surgery and adjuvant treatment | North America | |

| Shugarman et al USA66 | First date recorded for treatment (surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy) | ||

| Vidaver et al USA68 | First treatment date | ||

| Grunfeld et al Canada83 | Date of initiation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgery if no preoperative treatment was required, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or a decision not to treat. | ||

| Maiga et al USA42 | Time of resection. | ||

| Stokstad et al Norway87 | The time for treatment decision as the date when such a decision was documented in the Electronic Medical Record | Europe | |

| Helsper et al Netherlands30 | Date of start of therapy as registered in the Network of Cancer Registries | ||

| Iachina et al Denmark85 | First day of treatment is defined as the date of initiation of surgical, oncological, or radiological treatment, whichever comes first | ||

| Alexander et al Australia76 | Time to chemotherapy should be measured from the date that chemotherapy treatment was decided. For adjuvant chemotherapy, time to chemotherapy should be measured from the date of surgery. | Australia and New Zealand | |

| Evans et al Australia77 | Date of initial definitive management | ||

| Malalasekera et al Australia33 | Treatment start date | ||

| Rankin et al Australia32 | Start of treatment | ||

| Özlü et al Turkey69 | Start of treatment | Asia | |

| Yang et al Mainland China22 | Initiation of treatment date | ||

| Yilmaz et al Turkey27 | Date of thoracotomy |

GP, general practitioner.

Intervals

Fourteen different intervals, from onset of symptom(s) to initiation of treatment were identified in this scoping review (table 3): (1) From onset of symptoms to first contact with healthcare provider, (2) From first contact with general healthcare provider to first contact with specialist healthcare provider, (3) From first contact with secondary/tertiary healthcare provider to diagnosis, (4) From first contact with healthcare provider to diagnosis, (5) From diagnosis to contact with secondary/tertiary healthcare provider, (6) From onset of symptoms to contact with secondary/tertiary healthcare provider, (7) From contact with secondary/tertiary healthcare provider to initiation of treatment, (8) From onset of symptom(s) to referral to a specialist/ receipt of referral by a specialist or thoracic department, (9) From referral to a specialist/ receipt of referral by a specialist or thoracic department to diagnosis, (10) From onset of symptom to diagnosis, (11) From referral to a specialist/ receipt of referral by a specialist or thoracic department to treatment, (12) From first contact with healthcare provider to treatment, (13) From diagnosis to initiation of treatment and (14) From onset of symptom to Initiation of treatment. Intervals were not measured as completion of treatment or death.

Table 3.

Intervals in the lung cancer care pathway

| Intervals | Articles | Study setting |

| From onset of symptoms To First contact with healthcare provider |

Baughan et al UK80 | UK |

| Corner et al UK94 | ||

| Neal et al UK96 | ||

| Smith et al Scotland97 | ||

| Brocken et al Netherlands23 | Europe | |

| Helsper et al Netherlands30 | ||

| Koyi et al Sweden24 | ||

| Salomaa et al Finland21 | ||

| Sawicki et al Poland101 | ||

| Rolke et al Norway25 | ||

| Ezer et al Canada81 | North America | |

| Ellis and Vandermeer Canada43 | ||

| Verma et al Australia102 | Australia and New Zealand | |

| Thapa et al Nepal26 | Asia | |

| Yang et al Mainland China 41 | ||

| Yilmaz et al Turkey27 | ||

| Özlü et al Turkey69 | ||

| Sulu et al Turkey28 | ||

| From first contact with general healthcare provider To First contact with specialist healthcare provider |

Forrest et al UK78 | UK |

| Baughan et al UK80 | ||

| Barrett and Hamilton 2008 UK103 | ||

| Devbhandari et al UK71 | ||

| Melling et al UK84 | ||

| Girolamo et al UK79 | ||

| Rolke et al Norway25 | Europe | |

| Hueto Pérez De Heredia et al Spain72 | ||

| Koyi et al Sweden24 | ||

| Helsper et al Netherlands30 | ||

| Salomaa et al Finland21 | ||

| Brocken et al Netherlands23 | ||

| Vidaver et al USA68 | North America | |

| Olsson et al USA104 | ||

| Ellis and Vandermeer Canada43 | ||

| Grunfeld et al Canada83 | ||

| Verma et al Australia102 | Australia and New Zealand | |

| Emery et al Australia29 | ||

| Sood et al New Zealand73 | ||

| Yilmaz et al Turkey27 | Asia | |

| Thapa et al Nepal26 | ||

| Sulu et al Turkey28 | ||

| From first contact with secondary/tertiary healthcare provider To diagnosis |

Salomaa et al Finland21 | Europe |

| Rolke et al Norway25 | ||

| Koyi et al Sweden24 | ||

| Gozalez et al Spain31 | ||

| Ellis and Vandermeer Canada43 | North America | |

| Emery et al Australia29 | Australia and New Zealand | |

| Sulu et al Turkey28 | Asia | |

| Özlü et al Turkey69 | ||

| From first contact with healthcare provider To diagnosis |

Barrett and Hamilton UK103 | UK |

| Corner et al UK94 | ||

| Devbhandari et al UK71 | ||

| Forrest et al UK78 | ||

| Neal et al UK96 | ||

| Helsper et al Netherlands30 | Europe | |

| Ezer et al Canada81 | North America | |

| Vidaver et al USA68 | ||

| Emery et al Australia29 | Australia and New Zealand | |

| Rankin et al Australia32 | ||

| Özlü et al Turkey69 | Asia | |

| Hsieh et al Taiwan34 | ||

| From diagnosis to contact with secondary/tertiary healthcare provider |

Kanarek et al USA35 | North America |

| Wai et al Canada105 | ||

| Winget et al Canada106 | ||

| Zullig et al USA107 | ||

| From onset of symptoms To contact with secondary/tertiary healthcare provider |

Bjerager et al Denmark108 | Europe |

| Ampil et al USA36 | North America | |

| Thapa et al Nepal26 | Asia | |

| From contact with secondary/tertiary healthcare provider To initiation of treatment |

Devbhandari et al UK86 | UK |

| Girolamo et al UK79 | ||

| Gozalez et al Spain31 | Europe | |

| Rolke et al Norway25 | ||

| Hueto Pérez De Heredia et al Spain72 | ||

| Hubert et al Canada109 | North America | |

| Kanarek et al USA35 | ||

| Winget et al Canada106 | ||

| Vidaver et al USA68 | ||

| Ellis and Vandermeer Canada43 | ||

| Ampil et al USA36 | ||

| Olsson et al USA104 | ||

| Wai et al Canada105 | ||

| Verma et al Australia102 | Australia and New Zealand | |

| From onset of symptoms to referral to specialist/ receipt of referral by a specialist or thoracic department |

Lee et al UK74 | UK |

| Gozalez et al Spain31 | Europe | |

| Buccheri and Ferrigno Italy37 | ||

| From referral to a specialist/ receipt of referral by a specialist or thoracic department to diagnosis |

Barrett and Hamilton UK103 | UK |

| Smith et al Scotland97 | ||

| Helsper et al Netherlands30 | Europe | |

| Grunfeld et al Canada83 | North America | |

| Evans et al Australia77 | Australia and New Zealand | |

| Largey et al Australia67 | ||

| Sood et al New Zealand73 | ||

| From onset of symptoms to diagnosis |

Corner et al UK94 | UK |

| Lee et al UK74 | ||

| Walter et al UK38 | ||

| Koyi et al Sweden24 | Europe | |

| Wai et al Canada105 | North America | |

| Emery et al Australia29 | Australia and New Zealand | |

| Sachdeva et al India88 | Asia | |

| Chandra et al India41 | ||

| Dubey et al India89 | ||

| From referral to a specialist/ receipt of referral by a specialist or thoracic department to treatment |

Devbhandari et al UK71 | UK |

| Smith et al Scotland97 | ||

| Forrest et al UK78 | ||

| Bozcuk and Martin UK39 | ||

| Iachina et al Denmark85 | Europe | |

| Olsson et al USA104 | North America | |

| Grunfeld et al Canada83 | ||

| Ampil et al USA36 | ||

| Evans et al Australia77 | Australia and New Zealand | |

| Largey et al Australia67 | ||

| Sood et al New Zealand73 | ||

| Yang et al Mainland China22 | Asia | |

| From first contact with healthcare provider to treatment |

Melling et al UK84 | UK |

| Helsper et al Netherlands30 | Europe | |

| Sawicki et al Poland101 | ||

| Vidaver et al USA68 | North America | |

| Ezer et al Canada81 | ||

| Yang et al Mainland China22 | Asia | |

| Yilmaz et al Turkey27 | ||

| Özlü et al Turkey69 | ||

| Sulu et al Turkey28 | ||

| From diagnosis to initiation of treatment |

Forrest et al. 2014 UK78 | UK |

| Brocken et al Netherlands23 | Europe | |

| Gozalez et al Spain31 | ||

| Salomaa et al Finland21 | ||

| Helsper et al Netherlands30 | ||

| Iachina et al Denmark85 | ||

| Schultz et al USA70 | North America | |

| Kanarek et al USA35 | ||

| Grunfeld et al Canada83 | ||

| Borrayo et al USA110 | ||

| Kim et al Canada40 | ||

| Olsson et al USA104 | ||

| Ost et al USA75 | ||

| Yorio et al USA111 | ||

| Zullig et al USA107 | ||

| Li et al Canada100 | ||

| Maiga et al USA42 | ||

| Vidaver et al USA68 | ||

| Winget et al Canada106 | ||

| Largey et al Australia67 | Australia and New Zealand | |

| Malalasekera et al Australia33 | ||

| Evans et al Australia77 | ||

| Rankin et al Australia32 | ||

| Özlü et al Turkey69 | Asia | |

| Yang et al Mainland China22 | ||

| Yilmaz et al Turkey27 | ||

| Sulu et al Turkey28 | ||

| Chandra et al 2009 India41 | ||

| From onset of symptoms to initiation of treatment |

Salomaa et al Finland21 | Europe |

| Koyi et al Sweden24 | ||

| Rolke et al Norway25 | ||

| Sawicki et al Poland101 | ||

| Ellis and Vandermeer Canada43 | North America | |

| Olsson et al USA104 | ||

| Verma et al Australia102 | Australia and New Zealand | |

| Yilmaz et al Turkey27 | Asia | |

| Özlü et al Turkey69 | ||

| Sulu et al Turkey28 | ||

| Chandra et al India41 |

Some articles used different terminologies to label the same intervals; and similarly, the same terminology was used to label different intervals in different articles.

From onset of symptoms to first contact with healthcare provider interval: patient delay21–26 and patient’s application interval.27 28

Duration from first contact with healthcare provider to first contact with specialist at secondary care or next level: GP delay,21 23–25 GP interval,29 primary care interval,30 referral delay21 23 25 and referral interval.27 28

From first contact with secondary or tertiary healthcare provider to diagnosis interval: specialist interval,29 specialist’s delay (second doctor’s delay),21 24 25 diagnosis delay31 and diagnosis interval.28

From first contact with healthcare provider to diagnosis: diagnostic interval29 30 32 33 and delay in diagnosis.34

From diagnosis to contact with secondary/tertiary healthcare provider: referral interval in one study.35

Interval between onset of symptom to contact with secondary/tertiary healthcare provider: patient delay.36

Interval between contact with secondary/tertiary healthcare provider and initiation of treatment: hospital delay25 31 and treatment interval.35

From onset of symptoms to referral to a specialist thoracic department: referral delay,37 specialist delay.31

From referral to a specialist or receipt of referral by a specialist or thoracic department to diagnosis: referral interval.30

Interval between onset of symptom to diagnosis: total diagnostic delay29 and time to diagnosis.38

From referral to a specialist/receipt of referral by a specialist or thoracic department to treatment interval: time to treatment (hospital delay)39 and delay in secondary healthcare.22

Interval between first contact with healthcare provider to treatment: healthcare interval,30 system delay22 and doctor’s interval.27 28

From diagnosis to initiation of treatment: therapeutic delay,23 treatment delay,22 31 treatment interval,30 33 system interval,40 pretreatment interval,32 diagnosis-to-treatment delay41 and diagnosis-to-treatment interval.42

From onset of symptom(s) to initiation of treatment: global delay,43 total delay25 and symptom to treatment delay.41

Table 4 presents the time intervals commonly studied in the included articles. The most frequently studied interval was ‘diagnosis to initiation of treatment’, followed by ‘first contact with healthcare provider to specialist’ and ‘symptom onset to first contact’. Both ‘diagnosis to specialist’ and ‘specialist to diagnosis’ paths were studied. Very few studies have researched onset of symptom to referral and specialist consultation. The time point ‘patient informed of diagnosis’ and intervals involving this time point were rarely studied.

Table 4.

Time intervals commonly studied—dark blue >10 (most commonly), light blue >7 (commonly), lighter blue >3 (occasionally), white=none

| Starting point | Ending point | |||||

| First contact with healthcare provider | Referral | Specialist consultation | Diagnosis | Patient informed of diagnosis | Initiation of treatment | |

| Onset of symptom | 18 | 3 | 3 | 9 | - | 11 |

| First contact with healthcare provider | X | - | 22 | 12 | - | 9 |

| Referral | X | - | 7 | - | 12 | |

| Specialist consultation | X | 7 | - | 14 | ||

| Diagnosis | 4 | X | 3 | 28 | ||

| Patient informed of diagnosis | X | 3 | ||||

Timeliness measures

The review identified 30 articles which conceptualised delay in the care pathway by adapting benchmarks from established guidelines to set cut-off values. The benchmarks were guided by British Thoracic Society (BTS) recommendations on organising the care of patients with lung cancer,44 National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline,45 46 UK National Cancer Plan (UKNCP),47 UK National Health Service (UKNHS) guideline,48 49 UK Department of Health guideline,50 Research and Development (RAND) Corporation guideline,51 Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control,52 Canadian guidelines,53 Standing Medical Advisory Committee (SMAC),54 Cancer Council Australia and Cancer Australia,55 Danish Lung Cancer Group and Registry,56 Swedish Lung Cancer Group57 and Scottish Executive Health Department (SEHD),58 59 Institute of Medicine,60 Dutch Association of Physicians for Pulmonary Disease and Tuberculosis,61 Joint Council for Clinical Radiology,62 American College of Chest Physicians,63 and Norwegian National Guidelines.64

Six articles referenced cut-off values from other articles to compare timeliness24 35 41 65–67 and one article proposed a benchmark cut-off value based on their findings.68 Fifteen articles used single guidelines and fifteen articles used more than one guideline to conceptualise timeliness measures. Out of 30 articles, BTS was adopted by 14 articles,23 25 27 28 33 41 65 69–75 UKNHS was used seven times,33 67 72 76–79 NICE guideline by four articles,71 73 80 81 RAND corporation guideline by four articles33 70 75 82 and Canadian guidelines by four articles,27 28 41 83 SEHD guidelines by three articles,33 80 84 Danish Lung Cancer Group guidelines by three articles,33 67 85 UKNCP guidelines by two articles,71 86 SMAC guideline by two articles,33 84 Norwegian National Guidelines by two articles25 87 and Swedish Lung Cancer Group guidelines by two articles.28 33 Online supplemental file 3 describes the ‘measures of timeliness’/’benchmark for intervals’ with cut-off values adopted from different guidelines. Table 5 presents the timeliness measures according to study settings.

Table 5.

Most frequently cited guidelines used to measure timeliness across settings

| Guidelines | Articles included | Settings | |

| 1. | British Thoracic Society | Lee et al UK74 Forrest et al UK78 |

UK |

| Singh et al USA65Schultz et al USA70 Olsson et al USA104 Ost et al USA75 |

North America | ||

| Brocken et al Netherlands23Rolke et al Norway25 | Europe | ||

| Malalasekera et al Australia33Sood et al New Zealand73 | Australia and New Zealand | ||

| Özlü et al Turkey69Yilmaz et al Turkey27 Sulu et al Turkey28 Chandra et al Indian41 |

Asia | ||

| 2. | UK National Health Service | Barrett and Hamilton 2008 UK103 | UK |

| Hueto Pérez De Heredia et al Spain72 | Europe | ||

| Malalasekera et al Australia33Alexander et al Australia76 Evans et al Australia77 Sood et al New Zealand73 Largey et al Australia67 |

Australia and New Zealand | ||

| 3. | National Institute for Clinical Excellence guideline | Baughan et al UK80 Forrest et al UK78 |

UK |

| Olsson et al USA104 | North America | ||

| Verma et al Australia102 | Australia and New Zealand | ||

| 4. | RAND corporation | Schultz et al USA70 Ost et al USA75 Bullard et al USA82 |

North America |

| Malalasekera et al Australia33 | Australia and New Zealand | ||

| 5. | Canadian guidelines | Grunfeld et alet al. 2009 Canada83 | North America |

| Yilmaz et al Turkey27Sulu et al Turkey28 Chandra et al India41 |

Asia | ||

| 6. | Scottish Executive Health Department | Baughan et al UK80 Melling et al UK84 |

UK |

| Malalasekera et al Australia33 | Australia and New Zealand | ||

| 7. | Danish Lung Cancer Group | Iachina et al Denmark85 | Europe |

| Malalasekera et al Australia33Largey et al Australia67 | Australia and New Zealand | ||

| 8. | UK National Cancer Plan | Forrest et al UK78 Devbhandari et al UK86 |

UK |

| 9. | Standing Medical Advisory Committee | Melling et al UK84 | UK |

| Malalasekera et al Australia33 | Australia and New Zealand | ||

| 10. | Norwegian National Guidelines | Stokstad et al Norway87 Rolke et al Norway25 |

Europe |

| 11. | Swedish Lung Cancer Group | Malalasekera et al Australia33 | Australia and New Zealand |

| Sulu et al Turkey28 | Asia | ||

| 12. | Cut-off values referenced from other articles | Singh et al USA65 Shugarman et al USA66 Kanarek et al USA35 |

North America |

| Koyi et al\ Sweden24 | Europe | ||

| Largey et al Australia67 | Australia and New Zealand | ||

| Chandra et al India41 | Asia |

RAND, Research and Development.

bmjopen-2021-056895supp003.pdf (52.6KB, pdf)

BTS guidelines were those most frequently cited in the included studies (20%). Studies guided by the BTS guidelines adapted the definition of intervals and measurement of timeliness depending on the interval of interest. Common timeliness measures adapted from BTS included the length of time that should elapse from initial GP referral of suspected lung cancer to evaluation/respiratory assessment (≤1 week), primary care referral to receiving diagnostic tests (bronchoscopy/histology/cytology) (≤2 weeks), presentation of symptom to diagnosis (≤8 weeks), diagnosis to initiation of treatment (≤6 weeks), GP referral to specialist consultation (≤1 week), GP referral and initiation of any type of treatment (≤62 days), specialist consultation and surgery (thoracotomy) (≤8 weeks), surgical waiting list and thoracotomy (4 weeks), referral to surgeons (≤4 weeks), oncology referral to commencement of radiotherapy or chemotherapy (≤2 weeks), decision-to-treat to initiation of treatment (31 days).

Table 6 presents the frequently used intervals and guidelines to measure timeliness in the included articles.

Table 6.

Guidelines and interval benchmarks referenced in included articles

| BTS | NICE | UKNCP | UKNHS | UKDoH | RAND | CSCC | SMAC | SEHD | SIGN | NOLCP | CCA | SLCG | DLCG | DAPPDT | NNG | ACCP | IOM | |

| Onset of symptoms to first doctor visit | █ | |||||||||||||||||

| First clinical presentation to first suspicious investigation | █ | |||||||||||||||||

| First abnormal investigation (Chest X-Ray) to confirmation of diagnosis/ specialist visit | █ | █ | ||||||||||||||||

| GP to Specialist | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | ||||

| Primary care to initiation of treatment | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | ||||||||||

| Referral to secondary care to diagnosis | █ | █ | █ | █ | ||||||||||||||

| First referral to secondary care to treatment start | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | |||||||||||

| First clinical presentation to Diagnosis | █ | █ | ||||||||||||||||

| First investigation to treatment | █ | |||||||||||||||||

| Diagnostic investigation to patient informed of diagnosis | █ | |||||||||||||||||

| Diagnosis to Treatment start | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | █ | ||||||||||

| First clinical presentation to treatment start | █ | █ | █ | |||||||||||||||

| Decision to treatment to initiation of treatment | █ | █ | █ | |||||||||||||||

| Surgery to chemotherapy (Adjuvant chemotherapy) | █ | |||||||||||||||||

| Referral receipt to specialist consultation | █ | █ | █ | |||||||||||||||

| Oncology referral to radiotherapy/ chemotherapy | █ | █ | ||||||||||||||||

| Specialist consultation to surgery | █ | █ | ||||||||||||||||

| Surgeon consultation/ Surgical waiting list to surgery | █ | █ | █ | |||||||||||||||

| Onset of symptoms to treatment | █ | █ | ||||||||||||||||

| Primary care referral to first diagnostic evaluation of symptom | █ | |||||||||||||||||

| Primary care referral to completion of evaluation at referral centre | █ |

ACCP, American College of Chest Physicians; BTS, British Thoracic Society; CCA, Cancer Council Australia; CSCC, Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control; DAPPDT, Dutch Association of Physicians for Pulmonary Disease and Tuberculosis; DLCG, Danish Lung Cancer Group; GP, general practitioner; IOM, Institute of Medicine; NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NNG, Norwegian National Guidelines; NOLCP, National Optimal Lung Cancer Pathway; RAND, Research and Development USA; SEHD, Scottish Executive Health Department; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network; SLCG, Swedish Lung Cancer Group; SMAC, Standing Medical Advisory Committee; UKDoH, UK Department of Health; UKNCP, UK National Cancer Plan; UKNHS, UK National Health Service.

Differences between Asian and Western countries

There were nine studies from five Asian countries/territories included in the scoping review. There were no differences in the terminology for labelling time points and intervals in the lung cancer care pathway between studies from Asian and Western countries. Studies from Asian countries/territories adapted timeline for intervals from Western guidelines in many instances. One study from India41 and several Turkish27 28 69 studies measured timeliness by adapting guidelines from the BTS, Canada and Sweden. The reporting of timeliness was not described as being guided by any specific guideline in studies from mainland China,41 Nepal,26 Taiwan34 and two other studies from India.88 89

Discussion

The lung cancer care journey is not linier. Eight time points found to be most frequently used time points in the included studies, which leads to variations in selection of time points and measurements of intervals (determined by the context) in different studies. Which introduces challenges in assessing timeliness due to lack of appropriate benchmarking, in particular in Asian countries. Moreover, different time points and intervals were defined, and different guidelines were used depending on the interest of the study objectives. This also makes comparisons across studies difficult.

Time points

Different time points were studied depending on the objective of the research in the included studies. ‘Onset of symptoms’, ‘first contact with a healthcare provider, ‘specialist consultation’, ‘diagnosis’ and ‘initiation of treatment’ were the most frequently studied time points. The first event in any health-seeking behaviour relates to the first health changes or the onset of symptom(s). It is difficult to capture the exact time point of onset of symptom(s) except by asking respondents directly. It may also be difficult to establish a link between onset of symptoms and health-seeking behaviour relating to the diagnosis of lung cancer as similar symptoms are shared by other respiratory diseases. Included studies obtained data from a variety of sources including cancer registries, longitudinal surveillance data, insurance claims data, and hospital records. Not all the studies included the time point ‘onset of symptoms’ because of the differences in the interval of interest or objective of the study. The relevance and importance of the first time point to understanding the overall patient care pathway is likely to vary across countries with different health systems and resources. In contrast, clinical processes post diagnosis are highly standardised. As a result, research about timeliness in healthcare is focused primarily on the time points prior to diagnosis.

After onset of symptom(s) the next time point in the care seeking pathway is first contact with any healthcare provider. The studies included in this review reported only contact with formal healthcare providers. This may have been because of the difficulty involved in capturing reliable information on seeking healthcare from informal healthcare providers in the absence of any specific record management system and because of the potential for recall bias associated with self-report. Nonetheless, informal healthcare providers (including provision of over-the-counter medicines from unregulated pharmacies, village doctors and traditional or herbal remedies) are predominant in developing countries where, sometimes, informal healthcare is the only available healthcare option accessible.90 It was evident from the included studies that patients’ movement across different tiers of the health system is dynamic and complex. These different tiers within the systems are often not interlinked and using different medical record systems. However, the studies do not necessarily interpret or present this information in a way that makes it easy to understand why the time points are not consistently recorded.

After first contact with any healthcare provider the next time point in the lung cancer care pathway is diagnosis or referral to the next level of healthcare for evaluation of the disease. The way this occurs will depend on the characteristics of the healthcare system and patient behaviour. In some settings, there may be multiple contacts with different providers and the diagnosis could be made at any point, not just as an ‘endpoint’ before hospital admission. Furthermore, the way patients move across different sectors and services will vary across health systems but may not be described clearly in studies. Patients do not necessarily move through time points in sequential order. In some systems, patients may bypass certain time points. Most included studies were conducted in countries with a ‘gate keeper’ system consisting of GPs as the first point of contact for healthcare. However, this pathway is not common to all healthcare systems, and was generally not seen in studies from Asian countries. In these countries, confirmatory investigation requisition can be initiated before the referral to a specialist. For instance, a request for a CT and fine needle aspiration cytology can be initiated by a primary care physician and hence, a patient can be diagnosed with lung cancer by a GP before referral to secondary healthcare. Some of the studies included a time point reflecting hospital admission or first specialist visit date. Inclusion of referral time and hospital admission time or first specialist consultation time helped to measure the time elapsed from date of referral to consultation with a specialist or hospital admission. The date when a patient was informed of his/her diagnosis was mentioned by three studies. The last time point in the disease care pathway is the date of initiation of any oncological treatment.

Intervals

Studies have segmented the lung cancer care pathway into different intervals depending on the objectives of those studies and sources of data. ‘Onset of symptom’ to ‘first contact with any healthcare provider’, ‘first contact with any healthcare provider to ‘specialist consultation’, ‘first contact with any healthcare provider to ‘diagnosis’ and ‘diagnosis’ to ‘initiation of treatment’ were the most commonly used intervals in the included articles. However, there were marked differences in how the intervals were named and this heterogeneity in typologies can be misleading as the same name is used for different intervals. For instance, the ‘patient’s application interval’ and ‘the time between onset of symptoms to first contact with primary healthcare provider’ were descriptions of the same interval in two studies27 28 while the term ‘patient delay’ was used to measure both ‘onset of symptom to primary healthcare provider’21–26 and ‘onset of symptom to secondary healthcare provider’36 intervals. ‘Patient delay’ may not be entirely related to patient factors as lack of health resources can influence the time lapse from onset of symptom to contact with a healthcare provider.

Similarly, the interval ‘first contact with a primary healthcare provider to secondary healthcare provider’ was measured to reflect ‘referral delay’21 23 25 in some studies35 and ‘diagnosis to secondary/tertiary healthcare provider’ and ‘referral or receipt of referral by a specialist to diagnosis’30in others. There were also differences in defining diagnostic intervals including ‘from first contact with the secondary healthcare provider to diagnosis’,28 31 ‘from first contact with primary healthcare provider to diagnosis’,29 30 32–34 and ‘from onset of symptom to diagnosis’.29 38 The interval between ‘first contact with primary healthcare provider’ and ‘treatment initiation’ was labelled as ‘system delay’22 and ‘system interval’ and was also described as the ‘diagnosis to initiation of treatment’ interval.40 ‘Treatment delay’ was measured using the intervals ‘diagnosis to initiation of treatment’,22 and ‘onset of symptoms to initiation of treatment’.41 Use of different terminology for the same intervals and use of the same terminology to label different intervals is confusing and can lead to difficulties in interpretating results. Standardised typology would be helpful in order to streamline consistency and enable comparability across studies.

Timeliness

The terms ‘delay’ and ‘interval’ were both used in studies to describe timeliness. The term ‘delay’ conveys a negative connotation, despite most articles using the term in the absence of benchmarking. It would seem more appropriate to use the term ‘time interval’ rather than ‘delay’ as this may imply, inaccurately, that the patient has not sought help promptly. Therefore, several articles suggested using the term ‘time interval’ as a neutral alternative to ‘delay’.11 12 91 In contrast, other researchers have argued that the term ‘time interval’ should not be replaced by ‘delay’ unless the results are compared with others or against benchmarks.

There are some differences in the recommended timeframes for each interval between the guidelines. There were similarities in timeliness measures between the BTS guidelines and most of the European guidelines, with some differences compared with the North American guidelines.

More than half of the included studies (38) did not quantify upper limits for intervals based on existing guidelines. Studies which did not compare their results to any guideline generally compared their results with other timeliness of lung cancer treatment related studies and among the subgroups of patients within the study. Studies also have used different time intervals with different time points. As a result, they were not always comparable between studies. The comparison and interpretation of the results were difficult and created confusion when the studies were not from similar context and health system strength.

Asian and Western country differences

There were no differences between Asian and Western countries in the way they defined timeliness of care. Among 68 studies included in this review, nine studies were from Asian countries and/or territories.22 26–28 34 41 69 88 89 Four of nine Asian studies used Western lung cancer guidelines to measure timeliness27 28 41 69 and the other five studies did not use a guideline. It remains unclear how effective and relevant Western guidelines are for Asian countries, especially those with low and middle income. The lack of qualified providers, low availability of surgery and radiotherapy services, and poor access to and affordability of up-to-date treatments remain a prevailing concern for lung cancer care in low-income and middleincome countries (LMICs) compared with high-income countries (HICs).8 9 Moreover, universal healthcare and health insurance mechanisms are still in the development phase in many Asian countries and LMICs. Western guidelines were developed in a context where such health system factors contribute to the effectiveness of guidelines. Using a guideline meant for highly resourced health systems in a resource-constrained country may not accurately reflect expectations and goals for timeliness of lung cancer care; culturally sensitive and resource-sensitive guidelines are likely required.8 As most of the existing guidelines do not account for diversity in health resources, economic disparities or healthcare infrastructure, their applicability could be limited.92 93 The articles included from Asian countries/territories did not discuss the compatibility of Western guidelines in terms of relevance and appropriateness of recommended time limits for intervals in the disease care pathway in their context. Although the use of Western guidelines for LMICs with different health systems may not be appropriate, there is currently no guideline for lung cancer care which dictates standard time limits that considers the limitations of weaker health systems. The Asian Oncology Summit 2009 proposed a resource-stratified management guideline for non-small cell lung cancer treatment; however, it does not provide benchmarking for intervals in the care pathway, which need to be developed by respective countries adapting this guideline.10 Informal healthcare is a unique feature of the diverse healthcare system in Asian countries and LMICs, whereas Western guidelines do not have to consider the inclusion of informal healthcare in the care pathway for lung cancer. Considering inclusion of a time point related to informal healthcare seeking and a measure of the number of times patients sought care from informal healthcare providers could be useful for Asian countries and LMIC settings.

This scoping review is not devoid of limitations. The broad search strategy enabled inclusion of different study designs. This scoping review used a robust and established method guided by a published protocol. Independent screening and assessment of articles against inclusion and exclusion criteria by authors ensured minimisation of selection bias. As this review followed a scoping review methodology, it did not assess the quality of the included articles. Excluding Arksey and O’Malley’s optional stage of conducting stakeholder consultation might have limited this scoping review from reaching a consensus, however, the authors intended to undertake stakeholder consultation in the next phase of the research project based on the availability of funding. The majority of the included studies were from HICs, thus limiting the generalisability for low-income countries. Only studies published in English were included in the review, which could have missed potentially relevant literature in other languages. The search strategy used the most widely used databases; however, articles which were not identified through those databases could have been missed. Although we used common search terms for our search, missing a pertinent term could have limited the search results. Other potential limitations were limiting the search and inclusion of articles published in the last 20 years.

Conclusion

Although this review identified similarities in most of the time points and intervals of the included studies, there were substantial variations in selection and interpretation of the meaning of intervals. This lack of consistency creates a challenge for researchers who are trying to undertake research about timeliness of care for lung cancer. As timeliness of care studies are mostly carried out in Western countries and guidelines appear unsuited to weaker healthcare delivery systems, there is a need to revisit existing definitions to conduct timeliness of care related studies and a unified set of definitions needs to be set which can accommodate different structures and characteristics of health systems. The differences in healthcare delivery systems of Asian and Western countries, and between HICs and LMICs may suggest different sets of time points and intervals that reflect resources and feasibility need to be developed. The lack of data capture points in weaker resource-poor health systems and the presence of unregulated and untrained healthcare providers in LMICs make it difficult to conduct research on timeliness of lung cancer care. Differences in the structure and strength of health systems create challenges when comparing results of health service research in lung cancer between HICs and LMICs. Existing frameworks for understanding healthcare pathways such as The Aarhus Statement and Andersen’s model of health service utilisation could support synthesis of research but would need to be revisited and modified to be applicable to LMIC-specific contexts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Saima Sultana, Lauren Zarb and Bijaya Pokharel for their collaboration and assistance with article screening for this review. We would like to thank the La Trobe University library for giving the access to the database for search.

Footnotes

Contributors: AA is the guarantor and conceived the study, developed the protocol and search strategy, conducted the data charting, interpretation and manuscript development. AR and VL contributed to screening the articles, CL, CFM, AR and VL contributed to analysis, interpretation and critical feedback in manuscript finalisation. All authors provided critical comments and input to revisions to the paper and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval is not needed as this scoping review reviewed already published articles.

References

- 1.Wild CP, Weiderpass E, Stewart BW, eds. World Cancer Report: Cancer Research for Cancer Prevention. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, WHO, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold M, Rutherford MJ, Bardot A, et al. Progress in cancer survival, mortality, and incidence in seven high-income countries 1995-2014 (ICBP SURVMARK-2): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:1493–505. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30456-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet 2018;391:1023–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33326-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schabath MB, Cote ML. And priorities: lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019;28:1563–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher DA, Zullig LL, Grambow SC, et al. Determinants of medical system delay in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer within the veteran Affairs health system. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:1434–41. 10.1007/s10620-010-1174-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weller D, Vedsted P, Rubin G, et al. The Aarhus statement: improving design and reporting of studies on early cancer diagnosis. Br J Cancer 2012;106:1262–7. 10.1038/bjc.2012.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vinas F, Ben Hassen I, Jabot L, et al. Delays for diagnosis and treatment of lung cancers: a systematic review. Clin Respir J 2016;10:267–71. 10.1111/crj.12217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson BO. Evidence-Based methods to address disparities in global cancer control: the development of guidelines in Asia. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:1154–5. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70496-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edelman Saul E, Guerra RB, Edelman Saul M, et al. The challenges of implementing low-dose computed tomography for lung cancer screening in low- and middle-income countries. Nat Cancer 2020;1:1140–52. 10.1038/s43018-020-00142-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soo RA, Anderson BO, Cho BC, et al. First-Line systemic treatment of advanced stage non-small-cell lung cancer in Asia: consensus statement from the Asian oncology Summit 2009. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:1102–10. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70238-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walter F, Webster A, Scott S, et al. The Andersen model of total patient delay: a systematic review of its application in cancer diagnosis. J Health Serv Res Policy 2012;17:110–8. 10.1258/jhsrp.2011.010113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott SE, Walter FM, Webster A, et al. The model of pathways to treatment: conceptualization and integration with existing theory. Br J Health Psychol 2013;18:45–65. 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02077.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coxon D, Campbell C, Walter FM, et al. The Aarhus statement on cancer diagnostic research: turning recommendations into new survey instruments. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:677. 10.1186/s12913-018-3476-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In: Aromataris E ZM, ed. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York . Systematic Reviews CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care York YO31 7ZQ: University of York, 2009. Available: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf [Accessed 2 Nov 2020].

- 18.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ansar A, Lewis V, McDonald CF, et al. Defining timeliness in care for patients with lung cancer: protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open 2020;10:e039660. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O'Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:1291–4. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salomaa E-R, Sällinen S, Hiekkanen H, et al. Delays in the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer. Chest 2005;128:2282–8. 10.1378/chest.128.4.2282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang DW, Zhang Y, Hong QY. Determination of time to diagnosis for lung cancer patients and the role of a serum based biomarker panel in the early diagnosis for cohort of highrisk, symptomatic patients. Cancer 2015;121:3113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brocken P, Kiers BAB, Looijen-Salamon MG, et al. Timeliness of lung cancer diagnosis and treatment in a rapid outpatient diagnostic program with combined 18FDG-PET and contrast enhanced CT scanning. Lung Cancer 2012;75:336–41. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koyi H, Hillerdal G, Brandén E. Patient's and doctors' delays in the diagnosis of chest tumors. Lung Cancer 2002;35:53–7. 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00293-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rolke HB, Bakke PS, Gallefoss F. Delays in the diagnostic pathways for primary pulmonary carcinoma in southern Norway. Respir Med 2007;101:1251–7. 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thapa B, Sayami P. Low lung cancer resection rates in a tertiary level thoracic center in Nepal--where lies our problem? Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15:175–8. 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.1.175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yilmaz A, Damadoglu E, Salturk C, et al. Delays in the diagnosis and treatment of primary lung cancer: are longer delays associated with advanced pathological stage? Ups J Med Sci 2008;113:287–96. 10.3109/2000-1967-236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sulu E, Tasolar O, Berk Takir H, et al. Delays in the diagnosis and treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Tumori 2011;97:693–7. 10.1700/1018.11083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emery JD, Walter FM, Gray V, et al. Diagnosing cancer in the bush: a mixed methods study of GP and specialist diagnostic intervals in rural Western Australia. Fam Pract 2013;30:541–50. 10.1093/fampra/cmt016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Helsper CCW, van Erp NNF, Peeters PPHM, et al. Time to diagnosis and treatment for cancer patients in the Netherlands: room for improvement? Eur J Cancer 2017;87:113–21. 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzalez-Barcala FJ, Falagan JA, Garcia-Prim JM, et al. Timeliness of care and prognosis in patients with lung cancer. Ir J Med Sci 2014;183:383–90. 10.1007/s11845-013-1025-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rankin NM, York S, Stone E, et al. Pathways to lung cancer diagnosis: a qualitative study of patients and general practitioners about diagnostic and pretreatment intervals. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017;14:742–53. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201610-817OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malalasekera A, Nahm S, Blinman PL. How long is too long? A scoping review of health system delays in lung cancer. European Respiratory Review 2018;27:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsieh VC-R, Wu T-N, Liu S-H, et al. Referral-free health care and delay in diagnosis for lung cancer patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2012;42:934–9. 10.1093/jjco/hys113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanarek NF, Hooker CM, Mathieu L, et al. Survival after community diagnosis of early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Med 2014;127:443–9. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.12.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ampil FL, Caldito G. Patient-Provider delays in superior vena caval obstruction of lung cancer and outcomes. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2014;31:441–3. 10.1177/1049909113491622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buccheri G, Ferrigno D. Lung cancer: clinical presentation and specialist referral time. Eur Respir J 2004;24:898–904. 10.1183/09031936.04.00113603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walter FM, Rubin G, Bankhead C. Symptoms and other factors associated with time to diagnosis and stage of lung cancer: a prospective cohort study. British Journal of Cancer 2015;03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bozcuk H, Martin C. Does treatment delay affect survival in non-small cell lung cancer? A retrospective analysis from a single UK centre. Lung Cancer 2001;34:243–52. 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00247-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim JOA, Davis F, Butts C, et al. Waiting time intervals for non-small cell lung cancer diagnosis and treatment in Alberta: quantification of intervals and identification of risk factors associated with delays. Clin Oncol 2016;28:750–9. 10.1016/j.clon.2016.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chandra S, Mohan A, Guleria R, et al. Delays during the diagnostic evaluation and treatment of lung cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2009;10:453–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maiga AW, Deppen SA, Pinkerman R. Timeliness of care and lung cancer Tumor-Stage progression: how long can we wait? Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2017;104:1791–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ellis PM, Vandermeer R. Delays in the diagnosis of lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 2011;3:183–8. 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2011.01.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bts recommendations to respiratory physicians for organising the care of patients with lung cancer. the lung cancer Working Party of the British thoracic Society standards of care Committee. Thorax 1998;53 Suppl 1:S1–8. 10.1136/thx.53.suppl_1.s1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Referral guidelines for suspected cancer. London: NICE, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 46.NICE . Lung cancer: diagnosis and management CG121 National Institute for health care excellence 2011, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Executive N . The National cancer plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: Department of Health, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Health Service (NHS) . The operating framework for the NHS in England 2012/13. Produced by COI on behalf of the Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 49.England N . Everyone counts: planning for patients 2014/15 to 2018/19. England: NHS, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Department of Health . Referral guidelines for suspected cancer – consultation document November 1999. United Kingdom Department of Health. 1999, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Asch SM, Kerr EA, Hamilton EG. Quality of care for oncologic conditions and HIV: a review of the literature and quality indicators: Rand CORP SANTA MONICA Ca 2000.

- 52.Control. CSfC . The Canadian strategy for cancer control: a cancer plan for Canada. Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control Governing Council, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simunovic M, Gagliardi A, McCready D, et al. A snapshot of waiting times for cancer surgery provided by surgeons affiliated with regional cancer centres in Ontario. CMAJ 2001;165:421–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whitehouse, JMA . Management of lung cancer current clinical practices. London: Standing Medical Advisory Committee, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cancer Council Australia and cancer Australia (Australian government). optimal care pathway for people with lung cancer. Australia 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jakobsen E, Green A, Oesterlind K, et al. Nationwide quality improvement in lung cancer care: the role of the Danish lung cancer group and registry. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:1238–47. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182a4070f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hillerdal G. Recommendations from the Swedish lung cancer Study group: shorter waiting times are demanded for quality in diagnostic work-ups for lung care. Swedish Med J 1999;96:4691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scottish Executive Health Department . Cancer in Scotland: action for change. Edinburgh: SEHD, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scottish Executive Health Department . Scottish referral guidelines for suspected cancer. 2007. Edinburgh: SEHD, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaplan G, Lopez MH, McGinnis JM. Transforming health care scheduling and access: getting to now. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine (IOM), 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dutch Association of Physicians for Pulmonary Disease and Tuberculosis . Non-Small cell lung cancer guideline: staging and treatment, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oncology JCfC . Improving quality of cancer care: reducing delays in cancer treatment. Clinical oncology (Royal College of Radiologists 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alberts W, Bepler G, Hazelton T. American College of chest physicians. Chest 2003;123:332S–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.The Norwegian directorate of health . Norwegian national guidelines for lung cancer management, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Singh H, Hirani K, Kadiyala H, et al. Characteristics and predictors of missed opportunities in lung cancer diagnosis: an electronic health record-based study. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3307–15. 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shugarman LR, Mack K, Sorbero MES, et al. Race and sex differences in the receipt of timely and appropriate lung cancer treatment. Med Care 2009;47:774–81. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a393fe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Largey G, Ristevski E, Chambers H, et al. Lung cancer interval times from point of referral to the acute health sector to the start of first treatment. Aust Health Rev 2016;40:649–54. 10.1071/AH15220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vidaver RM, Shershneva MB, Hetzel SJ, et al. Typical time to treatment of patients with lung cancer in a multisite, US-Based study. J Oncol Pract 2016;12:e643–53. 10.1200/JOP.2015.009605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ozlü T, Bülbül Y, Oztuna F, et al. Time course from first symptom to the treatment of lung cancer in the eastern black sea region of turkey. Med Princ Pract 2004;13:211–4. 10.1159/000078318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schultz EM, Powell AA, McMillan A, et al. Hospital characteristics associated with timeliness of care in veterans with lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:595–600. 10.1164/rccm.200806-890OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Devbhandari MP, Bittar MN, Quennell P, et al. Are we achieving the current waiting time targets in lung cancer treatment? result of a prospective study from a large United Kingdom teaching hospital. J Thorac Oncol 2007;2:590–2. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318070ccf0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Evaluation of the use of a rapid diagnostic consultation of lung cancer. Arch Bronconeumol 2012;48:267–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]