Abstract

Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) is an age‐associated phenomenon characterized by clonal expansion of blood cells harboring somatic mutations in hematopoietic genes, including DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1. Clinical evidence suggests that CHIP is highly prevalent and associated with poor prognosis in solid‐tumor patients. However, whether blood cells with CHIP mutations play a causal role in promoting the development of solid tumors remained unclear. Using conditional knock‐in mice that express CHIP‐associated mutant Asxl1 (Asxl1‐MT), we showed that expression of Asxl1‐MT in T cells, but not in myeloid cells, promoted solid‐tumor progression in syngeneic transplantation models. We also demonstrated that Asxl1‐MT–expressing blood cells accelerated the development of spontaneous mammary tumors induced by MMTV‐PyMT. Intratumor analysis of the mammary tumors revealed the reduced T‐cell infiltration at tumor sites and programmed death receptor‐1 (PD‐1) upregulation in CD8+ T cells in MMTV‐PyMT/Asxl1‐MT mice. In addition, we found that Asxl1‐MT induced T‐cell dysregulation, including aberrant intrathymic T‐cell development, decreased CD4/CD8 ratio, and naïve‐memory imbalance in peripheral T cells. These results indicate that Asxl1‐MT perturbs T‐cell development and function, which contributes to creating a protumor microenvironment for solid tumors. Thus, our findings raise the possibility that ASXL1‐mutated blood cells exacerbate solid‐tumor progression in ASXL1‐CHIP carriers.

Keywords: ASXL1, CHIP, mouse solid‐tumor models, T cell, tumor immunity

ASXL1 mutations found in CHIP carriers alter T‐cell development and function, which contributes to creating a protumor environment for solid tumors.

Abbreviations

- ASXL1

additional sex combs‐like 1

- CHIP

clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential

- DNMT3A

DNA methyltransferase 3 alpha

- MMTV

mouse mammary tumor virus

- PyMT

polyomavirus middle tumor antigen

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TET2

Tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2

1. INTRODUCTION

During human aging, somatic mutations are accumulated in many types of cells. Recent whole‐genome sequencing studies revealed that clonal expansion of blood cells with acquired somatic mutations is unexpectedly common in healthy aged individuals. 1 , 2 This phenomenon is called clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP). Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential carriers are at increased risk for all‐cause mortality, blood cancers, and cardiovascular diseases. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential–associated mutations frequently occurred in genes encoding epigenetic regulators, including DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1.

Additional sex combs‐like 1 (ASXL1) is a member of the mammalian ASXL family. ASXL1 regulates gene expression and signal transduction through interactions with multiple proteins, such as BAP1, 7 EZH2, 8 BMI1, 9 BRD4, 10 AKT, 11 , 12 and NONO. 13 In addition to CHIP, ASXL1 is frequently mutated in myeloid malignancies and associated with poor prognosis. ASXL1 mutations are detected in the last exon, resulting in the translation of C‐terminally truncated ASXL1 proteins. The pathogenic ASXL1 mutants alter epigenetic modifications, 8 , 14 , 15 , 16 activate the AKT/mTOR pathway, 11 and disrupt paraspeckle formation. 13 We previously established conditional knock‐in mice carrying a C‐terminally truncated Asxl1 mutant with the floxed STOP cassette under the control of Rosa26 promoter. 17 The Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice, in which the mutant Asxl1 (Asxl1‐MT) was expressed specifically in hematopoietic cells, showed age‐related expansion of phenotypic hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in native hematopoiesis, 11 which recapitulates human ASXL1‐CHIP.

Clinical evidence suggests that CHIP is particularly prevalent in solid‐tumor patients, and its presence has an adverse impact on their overall survival. 18 The high frequency of CHIP in solid‐tumor patients is correlated with primal exposure to anticancer therapies and smoking habits. 19 Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential mutations in DNA damage repair genes, such as TP53, PPM1D, CHEK2, are frequently found in patients with prior exposure to cytotoxic chemotherapy. Smoking is strongly associated with ASXL1 mutations. 19 Whether the blood cells with CHIP‐associated mutations have causal effects in solid‐tumor progression, as they do in cardiovascular diseases, 20 , 21 has been unclear. A previous study using Tet2‐deficient mice showed that myeloid cell‐specific Tet2 deficiency inhibits melanoma progression, 22 while other studies showed that Tet2 deficiency in immune cells promotes the growth of hepatoma and lung cancer cells. 23 , 24 Thus, it appears that Tet2‐deficient immune cells create protumor or antitumor microenvironment in a tumor type–dependent manner. The role of other CHIP‐associated mutations in the development of solid tumors has not been investigated experimentally.

In this study, we assessed the role of blood cells with the ASXL1 mutation in various mouse solid‐tumor models using the Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice crossed with Vav‐Cre, LysM‐Cre, and Lck‐Cre mice. Our data indicate that Asxl1‐MT perturbs T‐cell development and function, which contributes to creating a protumor microenvironment for solid tumors.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Mice

Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice were generated as described previously 17 and were crossed with Vav‐Cre mice, 25 LysM‐Cre mice, 26 and Lck‐Cre mice. 27 LysM‐Cre mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (stock no. 004781). Lck‐Cre mice were provided by the Laboratory Animal Resource Bank, National Institutes of Biomedical Innovation, Health, and Nutrition. MMTV‐PyMT mice (FVB/N background) were also purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (stock no. 002374) and backcrossed into the C57BL/6J (CLEA Japan) background for at least 12 generations. 28 We generated Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl‐MMTV‐PyMT mice by crossing male MMTV‐PyMT mice with female Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice. Only female Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl‐MMTV‐PyMT or Asxl1‐MTfl/fl‐MMTV‐PyMT mice were used for experiments. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the approved protocol (PA20‐26) from the Laboratory Animal Research Center of the Institute of Medical Science at the University of Tokyo.

2.2. Cell lines and culture condition

C57BL/6‐derived melanoma B16F10, colon adenocarcinoma MC38, Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC), and breast cancer Py8119 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (D‐MEM, FUJIFILM, 044‐29765) containing 10% heat‐inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, F7524, Sigma) and Penicillin‐Streptomycin solution (FUJIFILM, 168‐23191). For passage, cells were dissociated using Trypsin. All cells were cultured at 37 ℃ with 5% CO2. B16F10 and LLC cells were obtained from the Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research, Institute of Development, Aging, and Cancer, Tohoku University. MC38 cells were purchased from Kerafast, and Py8119 cells were purchased from ATCC.

2.3. Genotyping

Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice carry the 3xFLAG‐Asxl1‐MT‐flox/flox‐IRES‐EGFP cDNA. Therefore, we used GFP expression as a marker of Asxl1‐MT expression. We collected peripheral blood from the mice’s tails and assessed GFP expression in blood cells by flow cytometry. Asxl1‐MT heterozygous (fl/wt) and Asxl1‐MT homozygous (fl/fl) mice were genotyped by genomic PCR. LysM‐Cre, Lck‐Cre, and MMTV‐PyMT mice were also genotyped by genomic PCR. DNA was extracted from the mice’s tails by the NaOH method. Primers used for the genotyping are provided in Table S1.

2.4. Syngeneic mouse transplantation model

A total of 4 × 105 B16F10, LLC, MC38, or Py8119 cells suspended in PBS were subcutaneously injected into the flank of mice per site (two sites in each mouse), under general anesthesia with isoflurane (3% × 2 ml/h for induction and 2% × 1.5 ml/h for maintenance). The hair of the flank area of the mice was removed before injection. The long axis (L) and short axis (S) of the tumors were measured every 2 days starting from day 6 or day 7 to 14–16 days (B16F10 and LLC) or 21–26 days (MC38 and Py8119) until the tumor volume grew over 800 mm3. The tumor volume (mm3) was calculated by the formula V = L 2 × S × (π/6). Tumor weights were measured at the endpoint day. The mice used for the experiments were 8–14 weeks old. All tumor volume measurements were performed in a blind manner.

2.5. Spontaneous mammary tumor model

Vav‐Cre; MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl and MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice were palpated weekly from the age of 12 weeks, and the time of the tumor onset was recorded. Note that C57BL/6 MMTV‐PyMT mice develop tumors slower than the commonly used FVB background. 29 At the endpoint, mammary tumors/glands were collected. The numbers of developed tumors (visible and palpable) in the cervical, thoracic, and abdominal‐inguinal mammary gland were counted, extirpated, and weighed to measure the whole‐body tumor weights. The samples were then fixed and preserved in formalin for H&E staining. Blood was collected at the endpoint day and was used to measure complete blood count. The tumor‐infiltrated immune cells were examined by flow cytometry.

2.6. Tumor dissociation

Tumor tissues were removed from the skin lesions of the tumor‐bearing mice at the endpoint day and kept in cold FACS buffer (PBS contains 3% FBS). Enzyme mix (Tumor Dissociation Kit, mouse [#130‐096‐730]) was prepared at the time of use. A 2.5‐ml enzyme mix was used for dissociation of tumors that weighed <500 mg, and a 5‐ml mix was used for those that weighed over 500 mg. Tumor samples were cut into 2–3 mm pieces with scissors inside the gentle MACS™ C Tubes (#130‐093‐237) containing the enzyme mix. Dissociation was performed using the gentle MACS Octo Dissociator with Heaters. The 37C_m_TDK_2 program was used for MMTV‐PyMT–derived tumors. A total of 10 ml FACS buffer was added to the dissociated tissues, and the reaction liquid was filtered through a 40‐μm cell strainer (#542040, Greiner Bio‐one). After red blood cell lysis, we counted the numbers of dissociated samples and analyzed them by the flow cytometry analysis (see Section 2.7).

2.7. Flow cytometry

For T‐cell analysis, the spleen and thymus were isolated from the mice and were crushed above the 100‐μm cell strainer (Greiner Bio‐One, # 54200) with the head of the sterilized 2.5‐ml syringe plunger. For the analysis of tumor‐infiltrated blood cells, tumors were dissociated (see Section 2.6), collected, and put into FACS buffer. Red blood cells were lysed with 1×RBC Lysis Buffer. A total of 1 × 106 cells per sample were stained with antibodies listed in Table S2. For analyzing the intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in T cells, 1 × 106 splenocytes isolated from mice were first stained with surface marker antibodies (PerCP‐Cy5.5‐CD3, BV421‐CD4, and PE‐Cy7‐CD8) and then incubated for 30 min at 37℃ with 5 μM CellROX Deep Red (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #C10422). For analyzing the mitochondrial membrane potential, 1 × 106 splenocytes were first stained with the surface marker as described in ROS analysis and then incubated with 100 μM MitoTracker Red (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #M22425). After staining, all cells were washed twice in the FACS buffer and analyzed by FACS AriaIII.

2.8. Histological tumor examination

The murine mammary gland containing adenocarcinomas or lumps from control (MMTV‐PyMT‐ Asxl1‐MTfl/fl) and Asxl1‐MT (Vav‐Cre; MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl) mice were fixed and stocked in 10% formalin‐PBS solution. The tissues were embedded in paraffin and processed for sectioning and H&E staining by the Pathology Core Laboratory of the IMSUT.

2.9. T‐cell bulk RNA‐seq

Murine splenocytes from 12‐week‐old Vav‐Cre (−) and Vav‐Cre (+) Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice were collected and stained with biotinylated antibodies (CD19, TCRγδ, CD49b, CD11c, B220, Gr1, CD11b, Ter119) for T‐cell negative selection after red blood cell lysis. Then, 2–2.5 × 106 CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were sorted by AriaIII. Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). mRNA was purified from total RNA using poly‐T oligo‐attached magnetic beads. Pair‐end sequencing FASTQ files were aligned to the mouse reference genome (mm10) using HISAT2 30 on Galaxy platform (https://usegalaxy.org ). Raw gene counts were obtained from read alignments by Rsubread 31 (v2.4.3) and further transferred into count per million (CPM) by edgeR 32 (v3.32.1). After filtering out low‐expression genes with CPM lower than 1, all CPM values were log2 transformed for generating unsupervised clustering dendrograms and heatmaps. Differential expression was analyzed with the linear model using limma 33 (v3.46.0). Genes with false discovery rate (FDR)<0.05 adjusted by the Benjamini‐Hochberg method were considered significant differentially expressing genes (DEGs), which were further enrolled in gene ontology analysis using clusterProfiler 34 (v3.18.1). For MSigDB gene pathway overlap analysis, DEGs with FDR <0.05 were investigated on http://www.gsea‐msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/annotate.jsp.

2.10. Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 9 was used to perform statistical analyses. Two‐tailed unpaired t test or multiple t test was used for pairwise comparisons, and one‐way ANOVA was used for multiple comparisons of significance. The log‐rank test (Mantel‐Cox test) was used for the tumor‐free survival curve. FlowJo was used for FCM data analysis. The statistical significance (p‐value) was indicated in the figures and figure legends. The p‐value (<0.05, <0.01, <0.001) is displayed as one to three asterisks (*, **, ***). p‐values higher than 0.05 were considered not significant (ns).

3. RESULTS

3.1. T cells expressing Asxl1‐MT promote solid‐tumor progression in syngeneic transplantation models

We first investigated the influence of blood cells with the ASXL1 mutation on the growth of solid tumors using the syngeneic mouse tumor models. We crossed Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice with Vav‐Cre, LysM‐Cre, or Lck‐Cre mice to generate the mice expressing Asxl1‐MT in all blood cells, myeloid cells, or T cells, respectively. Homozygous (fl/fl) Asxl1‐MT mice were identified using PCR and used for experiments (Figure S1A). Expression of GFP (Asxl1‐MT) in the myeloid or lymphoid fraction in LysM‐Cre or Lck‐Cre mice, respectively, was confirmed by FACS (Figure S1B–E).

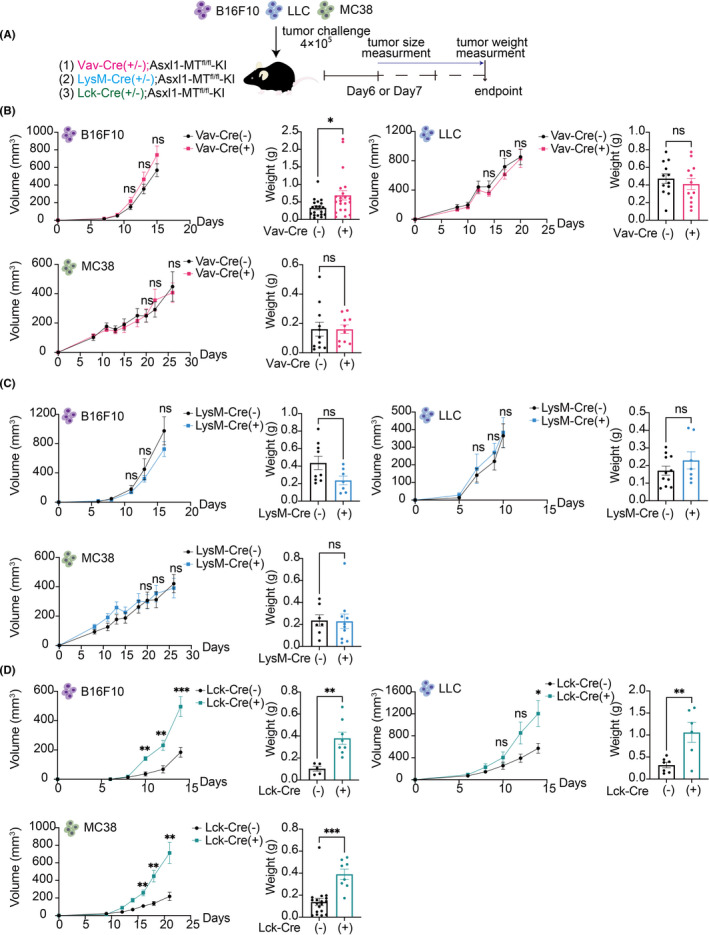

Next, we subcutaneously injected the C57BL/6 mouse‐derived solid‐tumor cell lines (B16F10 melanoma cells, LLC cells, and MC38 colon cancer cells) into these mice. The tumor size was measured every other day, and the tumor weight was measured at the endpoint day (Figure 1A). We did not observe substantial changes in the growth of all these tumor cells between control and Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice, except a slight increase of melanoma weight in Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice (Figure 1B). All the tumor cells grew similarly in LysM‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl and control mice (Figure 1C). In contrast, the growth of B16F10, LLC, and MC38 cells were all accelerated in Lck‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice (Figure 1D). These data suggest that T‐cell–specific expression of Asxl1‐MT promotes solid‐tumor progression, while expression of Asxl1‐MT in other types of blood cells does not.

FIGURE 1.

Increased growth of multiple solid tumors in Lck‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice. A, Schematic diagram of the syngeneic mouse models. Cre(−) and Cre(+) indicate Cre(−/−) and Cre(+/−), respectively. B, The growth curves of tumor volumes (mm3) and endpoint weights (g) of B16F10 [Vav‐Cre(−): n = 33, Vav‐Cre(+): n = 26], LLC [Vav‐Cre(−): n = 12, Vav‐Cre(+): n = 12), and MC38 [Vav‐Cre(−): n = 12, Vav‐Cre(+): n = 10] in control and Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice. C, The growth curves of tumor volumes and endpoint weights of B16F10 [LysM‐Cre(−): n = 10, LysM‐Cre(+): n = 6], LLC [LysM‐Cre(−): n = 16, LysM‐Cre(+): n = 8], and MC38 [LysM‐Cre(−): n = 7, LysM‐Cre(+): n = 11) in control and LysM‐Cre‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice. D, The growth curves of tumor volumes and endpoint weights of B16F10 [Lck‐Cre(−): n = 5, Lck‐Cre(+): n = 8], LLC (Lck‐Cre(−): n = 7, Lck‐Cre(+): n = 6), and MC38 (Lck‐Cre(−): n = 22, Lck‐Cre(+): n = 8) in control and Lck‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice. All data are shown as mean ± SEM. Multiple unpaired t test with Welch correction was used for the tumor volumes. Unpaired t test was used for the comparison of the endpoint weights. Two or three independent experiments using littermate mice were performed in a blind manner

3.2. Blood cells expressing Asxl1‐MT promote the development of spontaneous mammary tumors

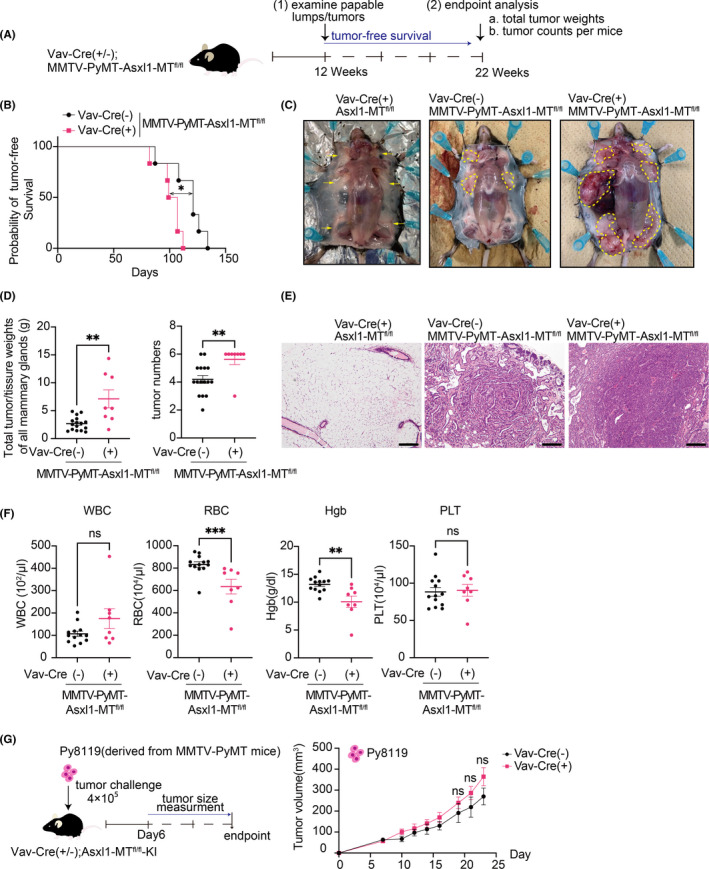

In the syngeneic tumor models, tumors are generated by subcutaneous implantation of established tumor cell lines. Therefore, the models used above do not reflect tumor progression in relevant organ‐specific environments. To assess the role of Asxl1‐MT–expressing blood cells in tumor development in the correct microenvironment, we next used the spontaneous mouse breast cancer model induced by the polyoma middle T antigen (PyMT) driven by the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter. We crossed Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice with MMTV‐PyMT mice to generate Vav‐Cre; MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice, in which PyMT and Asxl1‐MT were expressed in the mammary gland and blood cells, respectively (Figure S2A–C). Tumor‐free survival was assessed by palpation of the mammary glands from the age of 12 weeks. The numbers and weight of the tumors were assessed at the average age of 22 weeks (Figure 2A and Figure S2D). We observed earlier onset of tumors and increased tumor numbers and weights at the endpoint in Asxl1‐MT (Vav‐Cre; MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl) mice compared with control (MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl) mice (Figure 2B–E). Thus, these data suggest that the expression of Asxl1‐MT in blood cells creates a protumor microenvironment in the spontaneous breast cancer model. Interestingly, we also found that Asxl1‐MT mice developed modest anemia at the endpoint (Figure 2F). This anemia is likely associated with the advanced stage of mammary tumors 35 that developed in Asxl1‐MT mice. Importantly, we did not observe the increased tumor growth in Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice subcutaneously implanted with MMTV‐PyMT‐derived Py8119 cells (Figure 2G). Thus, Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice provide favorable tumor microenvironment only in the spontaneous breast cancer model.

FIGURE 2.

Development of spontaneous mammary tumors was promoted in Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice. A, Schematic diagram of the spontaneous mammary tumor model. B, Tumor‐free survival curves of MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl (n = 6) and Vav‐Cre; MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl (n = 6) mice. Log‐rank (Mantel‐Cox) test was used for comparison. C, Representative pictures of the mammary glands. Left: Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice. Middle: MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice. Right: Vav‐Cre; MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice. Yellow arrows indicate mammary glands, and the tumors were circled with yellow dotted lines. D, Left: total tumor/tissue weights of all mammary glands per mouse (MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl: n = 16, Vav‐Cre; MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl: n = 10). Right: numbers of tumors per mouse (MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl: n = 16, Vav‐Cre; MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl: n = 8). E, Representative pictures of H&E staining of the mammary glands in Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl (left), MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl (middle), and Vav‐Cre; MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl (right) mice at day 148. The scale bar is 200 μm F, Complete blood count (CBC) of peripheral blood collected from the mice at their endpoint (MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl: n = 13, Vav‐Cre; MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl: n = 8). Hgb, hemoglobin; PLT, platelet; RBC, red blood cells; WBC, white blood cells.. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Mann Whitney t test was used for the comparison. G, Schematic diagram of the syngeneic mouse models (left). Mice were sacrificed at day 24. The growth curves of tumor volumes (mm3) of Py8119 [Vav‐Cre(−): n = 9, Vav‐Cre(+): n = 10] in control and Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice (Right). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Multiple unpaired t test with Welch correction was used for the tumor volumes

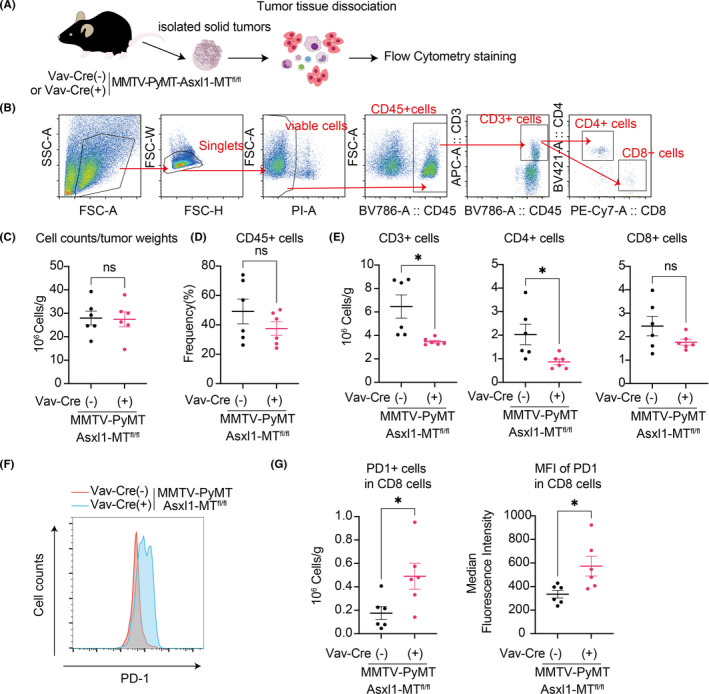

Next, we examined the infiltrated immune cells inside the tumors using flow cytometry (Figure 3A). The numbers of whole cells per gram in the tumor and the frequency of the infiltrated CD45+ hematopoietic cells did not change between the groups (Figure 3B–D). Importantly, we observed a significant reduction of infiltrated CD3+ and CD4+ T cells in mammary tumors of Asxl1‐MT mice (Figure 3E). Although the number of CD8+ T cells was not significantly reduced in tumors of Asxl1‐MT mice (Figure 3E), the expression of an exhaustion marker PD‐1 was upregulated in them (Figure 3F,G). These data indicate that Asxl1‐MT–expressing T cells have an exhausted phenotype and impaired ability to infiltrate the tumor site.

FIGURE 3.

Intratumor analysis in the MMTV‐PyMT mice. A, Schematic diagram of intratumor analysis using flow cytometry. B, The gating strategy of intratumor T cells. Mammary tumors were collected from the MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl [Vav‐Cre(−)] mice and Vav‐Cre; MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl [Vav‐Cre(+)] mice. C–E, Total cell numbers per gram of tumors (C); the frequency of infiltrated CD45+ cells (D); and numbers of tumor‐infiltrated CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells per gram of tumors (E). F, Representative FACS plots of PD‐1+ in tumor‐infiltrated CD8+ T cells. G, Numbers of PD1+ cells in tumor‐infiltrated CD8+ T cells per gram of tumors (left) and the median fluorescence intensity (right) are shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Unpaired t test was used for the comparison

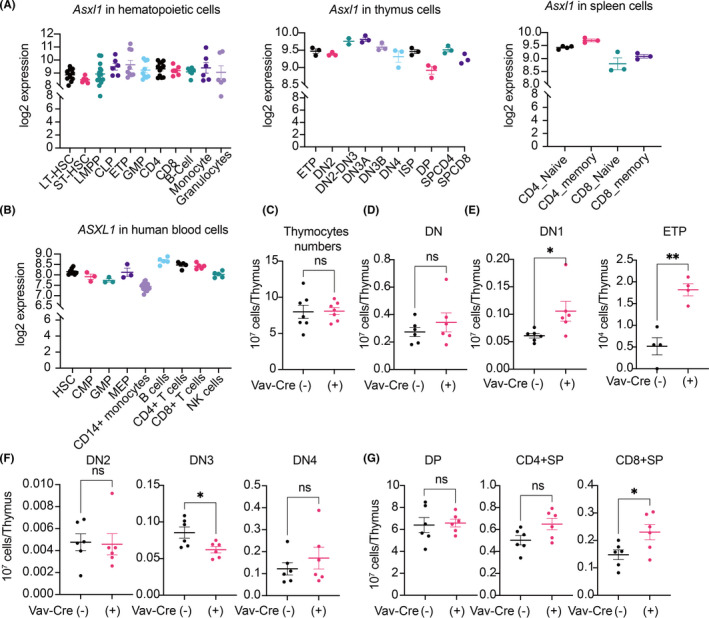

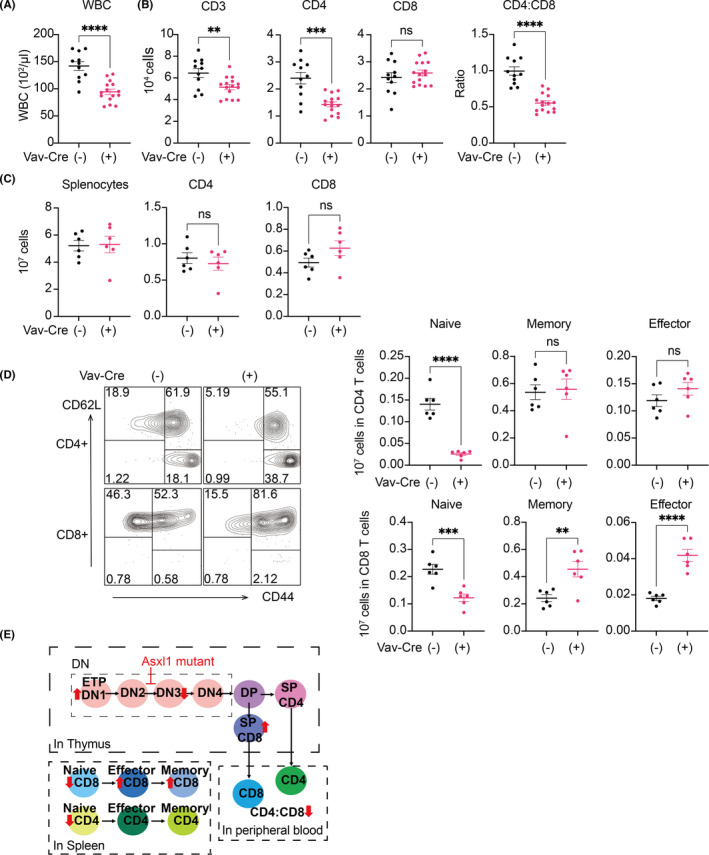

3.3. Asxl1‐MT perturbs T‐cell development and naïve T‐cell maintenance

The results described above indicate that Asxl1‐MT promotes solid‐tumor progression through T‐cell dysregulation. In fact, ASXL1 is highly expressed in mouse and human T cells (Figure 4A,B). To address the effect of Asxl1‐MT in T‐cell development, we first analyzed the number and subset distribution of thymocytes in control and Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice. Expression of Asxl1‐MT did not change the absolute numbers of thymocytes and the CD4−CD8− double‐negative (DN) fraction (Figure 4C,D). However, the proportion of DN1 cells, especially lineage−c‐Kit+ early T‐cell precursor (ETP) population, was significantly increased in Asxl1‐MT–expressing thymi (Figure 4E). In contrast, CD44−CD25+ DN3 cells were decreased in Asxl1‐MT–expressing thymi, indicating a developmental defect from DN1 to later stages (Figure 4F). We also found that the CD8+ single‐positive (SP) cells were increased, while the CD4+CD8+ double‐positive (DP) cells and CD4+ SP cells remained unchanged (Figure 4G). Thus, the expression of Asxl1‐MT alters the intrathymic differentiation of immature T cells.

FIGURE 4.

Asxl1‐MT perturbs T‐cell development in the thymus. A, B, Log2 expression of murine Asxl1 in normal hematopoietic cells, thymocytes, and splenocytes (A) and that of ASXL1 in human normal hematopoietic cells (B). Data were exported from the bloodspot website (https://servers.binf.ku.dk/bloodspot/). C–G, Total numbers of thymocytes (C); numbers of CD4−CD8− double‐negative (DN) cells (D); numbers of CD4−CD8−CD44+CD25− DN1 cells and Lineage−CD4−CD8−CD44+ ckit+ CD25− ETP cells (E); numbers of CD4−CD8−CD44+CD25+ DN2, CD4−CD8−CD44−CD25+ DN3, and CD4−CD8−CD44−CD25− DN4 cells (F); and numbers of CD4+CD8+ DP, CD4+CD8− SP, and CD4−CD8+ SP cells (G) in thymus of Asxl1‐MTfl/fl [Vav‐Cre(−)] and Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl [Vav‐Cre(+)] mice are shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Unpaired t test was used for the comparison

Next, we assessed T‐cell phenotypes in the peripheral organs. Expression of Asxl1‐MT resulted in the decrease of CD3+ and CD4+ cells and the CD4/CD8 ratio in peripheral blood of Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice (Figure 5A,B). Intriguingly, we also found a dramatic reduction of naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and an increase of memory and effector CD8+ T cells in the spleen of Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice (Figure 5C,D). The reduction of peripheral naïve T cells and a relative increase of memory/effector T cells are typical immunosenescent features that are observed in aged T cells. 36 , 37 , 38 The T‐cell phenotypes were also confirmed in Asxl1‐MT mice inoculated with the Py8119 breast cancer cells (Figure S3A). Interestingly, we observed the tendency of PD‐1 upregulation in peripheral CD8+ T cells of Asxl1‐MT mice with Py8119 cells (Figure S3B), indicating that tumor cells may promote the exhaustion of Asxl1‐MT T cells. However, this possibility should be examined in spontaneous tumor modes in future.

FIGURE 5.

Asxl1‐MT perturbs peripheral T‐cell development and naïve T‐cell maintenance. A, Complete blood count of white blood cells (WBC) in peripheral blood collected from Asxl1‐MTfl/fl [Vav‐Cre(−)] and Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl [Vav‐Cre(+)] mice. B, Cell counts of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells and CD4/CD8 ratio in peripheral blood. C, Cells counts of the whole splenocytes and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in spleen. D, Cell counts of naïve (CD62L+ CD44−), effector (CD62L−CD44+), and memory (CD62L+CD44+) fractions in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in spleen. Representative FACS plots (left) and their quantification (right) are shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Unpaired t test was used for the comparison. E, The scheme of the effect of Asxl1‐MT in thymic and peripheral T‐cell development

Taken together, these data suggest that mutant Asxl1 perturbs T‐cell development in the thymus and induces naïve‐memory imbalance in peripheral organs (Figure 5E).

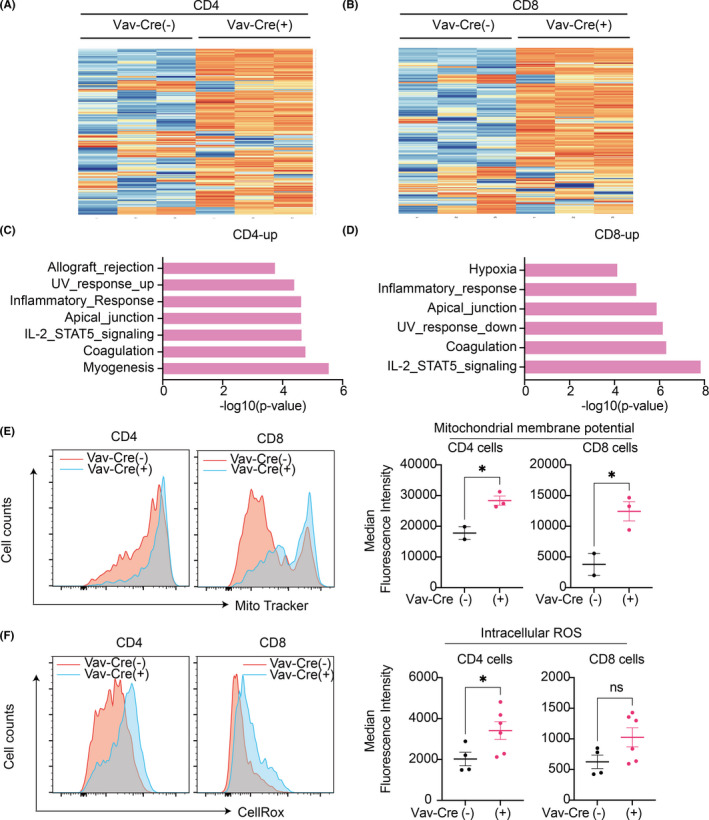

3.4. Asxl1‐MT induces inflammation and mitochondrial dysregulation in T cells

To examine the molecular changes in T cells expressing Asxl1‐MT, we performed RNA‐seq using splenocytes from control (Asxl1‐MTfl/fl) and Asxl1‐MT (Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl) mice. Hierarchical clustering revealed a clear separation between control and Asxl1‐MT–expressing T cells (Figure 6A,B). MSigDB gene pathway overlap analysis revealed that Asxl1‐MT upregulated genes related to IL‐2‐STAT5 signaling and inflammatory responses in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Figure 6C,D). Activation of the IL‐2‐STAT5 pathway and upregulation of the proinflammatory genes indicate the chronic‐activation and the exhaustion phenotype of Asxl1‐MT–expressing T cells.

FIGURE 6.

Mutant ASXL1 induces inflammation and mitochondrial dysregulation in T cells. A, B, Hierarchical clustering of the RNA‐Seq data of CD4+ (A) and CD8+(B) T cells. Top 200 most viable genes and comparison of control [Vav‐Cre(−)] and Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl [Vav‐Cre(+)] mice are shown (n = 3 per group). C, D, Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) for upregulated genes in CD4+ (C) and CD8+ T (D) cells using the MSigDB. The x‐axis shows the p‐value (−log10). E, Mitochondrial membrane potential in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of Asxl1‐MTfl/fl [Vav‐Cre(−)] (n = 2) and Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl [Vav‐Cre(+)] (n = 3). Representative histograms (left panel) and median fluorescence intensities (right panel) are shown. F, Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of Asxl1‐MTfl/fl [Vav‐Cre(−)] (n = 4) and Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl [Vav‐Cre(+)] (n = 6) mice. Representative histograms (left panel) and median fluorescence intensities (right panel) are shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Unpaired t test was used for the comparison

We previously showed that Asxl1‐MT activates mitochondrial dysregulation as well as overproduction of ROS in HSCs. 11 Consistent with the phenotypes of Asxl1‐MT–expressing HSCs, we observed increased mitochondrial membrane potential in CD4+ and CD8+ Asxl1‐MT–expressing T cells (Figure 6E). Asxl1‐MT also increased the intracellular ROS level in CD4+ T cells and tended to increase it in CD8+ T cells (Figure 6F). Collectively, these data suggest that Asxl1‐MT provokes inflammation and mitochondrial dysregulation in T cells, thereby accelerating T‐cell aging.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that T‐cell–specific expression of Asxl1‐MT promoted the growth of melanoma, lung cancer, and colon cancer cells in syngeneic models. Interestingly, this protumor effect was not observed when Asxl1‐MT was expressed in all hematopoietic lineage in Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice. These results suggest that myeloid cells or other immune cells with Asxl1‐MT have antitumor functions that can diminish the protumor effect of ASXL1‐mutated T cells. Indeed, we found that Asxl1‐MT promotes a proinflammatory phenotype in monocytes and macrophages (N. Sato et al., in submission), which are known to inhibit tumor progression. Thus, it is likely that Asxl1‐MT–expressing immune cells have either pro‐ or antitumorigenic roles depending on the context and cell types. In addition to ASXL1, CHIP‐associated TET2 mutations in immune cells were shown to modulate cancer progression. Previous studies have shown that TET2 depletion in myeloid cells alters T‐cell recruitment 22 , 23 and tumor angiogenesis. 24 Interestingly, TET2 is also involved in the maturation and activation of B cells, T cells, and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, 39 , 40 , 41 indicating the potential role of TET2‐mutated lymphocytes in cancer development. Furthermore, both TET2 and DNMT3A mutations were shown to increase expression of chemokines and inflammatory cytokines 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 such as IL‐6 in myeloid cells, which could contribute to the creation of the inflammatory tumor microenvironment. Further investigation will be required to determine the diverse roles of CHIP‐associated mutations in immune cells and their impacts on solid‐tumor progression.

Importantly, Asxl1‐MT promoted the development of spontaneous MMTV‐PyMT–induced mammary tumors even in the Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice. The correct microenvironment and longer latency period for tumor development in the MMTV‐PyMT model may reveal the protumor effect of the ASXL1 mutation in whole blood cells, which was not evident in the syngeneic transplantation models. The protumor microenvironment was likely to be created by the reduction of infiltrated T cells and the exhaustion of CD8+ T cells, but this should be confirmed experimentally using Lck‐Cre; MMTV‐PyMT‐Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice in future studies. Because the Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice mimic many features of human CHIP, these results indicate that somatic ASXL1 mutations in blood cells play a causal role in solid‐tumor progression probably through T‐cell dysregulation. However, it should be noted that all blood cells express Asxl1‐MT in the Vav‐Cre; Asxl1‐MTfl/fl mice, while only a small fraction of blood cells have ASXL1 mutations in human CHIP carriers. Given that variant allele frequencies (VAFs) of most CHIP‐associated mutations, including ASXL1 mutations, were higher in myeloid cells compared with lymphoid cells, 46 whether the small numbers of T cells with ASXL1 mutations increase the risk of cancer in the long human life span remains unknown. The real contribution of CHIP clones in solid‐tumor development needs to be verified using spontaneous tumor models with small numbers of CHIP cells.

As ASXL1 is frequently mutated in myeloid malignancies, diverse roles of Asxl1‐MT in HSCs and myeloid cells have been rigorously investigated for the past few years. 15 , 47 However, little was known about the role of Asxl1‐MT in T cells. Our study revealed the unexpected effect of the ASXL1 mutation in the regulation of T‐cell development and function. In particular, Asxl1‐MT decreased naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T‐cell numbers, which is one of the hallmarks of aged T cells. 38 Asxl1‐MT also induces upregulation of proinflammatory genes, mitochondrial dysregulation, and overproduction of the intracellular ROS in T cells. Because these phenotypes are often seen in aged T cells, Asxl1‐MT may induce premature aging of T cells, as it does in HSCs. 11 It is also tempting to speculate that the altered T‐cell function may contribute to the evolution of ASXL1‐CHIP and the development of myeloid neoplasms driven by ASXL1 mutations. How ASXL1 mutations affect T‐cell development is still obscure and warrants further investigation.

In summary, we showed that CHIP‐associated Asxl1‐MT induces T‐cell dysregulation and promotes tumor progression in multiple solid‐tumor models. Our findings raise the possibility that blood cells with ASXL1 mutations exacerbate solid‐tumor progression in ASXL1‐CHIP carriers.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Fig S1

Fig S2

Fig S3

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We sincerely thank Shiori Shikata for her expert technical assistance. We sincerely thank the Flow Cytometry Core and the Mouse Core at IMSUT for their technical help. We also thank Dr. Takuma Shibata and Dr. Kensuke Miyake for letting us use the gentle MACS Octo Dissociator with Heaters. This work was supported by a Grant‐in‐Aid for Challenging Research (Exploratory) (19K22554, SG), a Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (B) (19H03685, SG), and a grant from the Koyanagi Foundation (SG).

Liu X, Sato N, Shimosato Y, et al. CHIP‐associated mutant ASXL1 in blood cells promotes solid tumor progression. Cancer Sci. 2022;113:1182–1194. doi: 10.1111/cas.15294

REFERENCES

- 1. Genovese G, Kähler AK, Handsaker RE, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood‐cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2477‐2487. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Xie M, Lu C, Wang J, et al. Age‐related mutations associated with clonal hematopoietic expansion and malignancies. Nat Med. 2014;20(12):1472‐1478. doi: 10.1038/nm.3733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaner J, Desai P, Mencia‐Trinchant N, Guzman ML, Roboz GJ, Hassane DC. Clonal hematopoiesis and premalignant diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2020;10(4):a035675. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a035675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Asada S, Kitamura T. Clonal hematopoiesis and associated diseases: a review of recent findings. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(10):3962‐3971. doi: 10.1111/cas.15094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Veiga CB, Lawrence EM, Murphy AJ, Herold MJ, Dragoljevic D. Myelodysplasia syndrome, clonal hematopoiesis and cardiovascular disease. Cancers. 2021;13(8):1968. doi: 10.3390/cancers13081968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jaiswal S, Libby P. Clonal haematopoiesis: connecting ageing and inflammation in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(3):137‐144. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0247-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Asada S, Goyama S, Inoue D, et al. Mutant ASXL1 cooperates with BAP1 to promote myeloid leukaemogenesis. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2733. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05085-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Inoue D, Kitaura J, Togami K, et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes are induced by histone methylation–altering ASXL1 mutations. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(11):4627‐4640. doi: 10.1172/JCI70739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Uni M, Masamoto Y, Sato T, et al. Modeling ASXL1 mutation revealed impaired hematopoiesis caused by derepression of p16Ink4a through aberrant PRC1‐mediated histone modification. Leukemia. 2019;33(1):191‐204. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0198-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yang H, Kurtenbach S, Guo Y, et al. Gain of function of ASXL1 truncating protein in the pathogenesis of myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2018;131(3):328‐341. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-06-789669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fujino T, Goyama S, Sugiura Y, et al. Mutant ASXL1 induces age‐related expansion of phenotypic hematopoietic stem cells through activation of Akt/mTOR pathway. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1826. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22053-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Youn HS, Kim TY, Park UH, et al. Asxl1 deficiency in embryonic fibroblasts leads to cellular senescence via impairment of the AKT‐E2F pathway and Ezh2 inactivation. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):5198. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05564-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yamamoto K, Goyama S, Asada S, et al. A histone modifier, ASXL1, interacts with NONO and is involved in paraspeckle formation in hematopoietic cells. Cell Rep. 2021;36(8):109576. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abdel‐Wahab O, Gao J, Adli M, et al. Deletion of Asxl1 results in myelodysplasia and severe developmental defects in vivo. J Exp Med. 2013;210(12):2641‐2659. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Asada S, Fujino T, Goyama S, Kitamura T. The role of ASXL1 in hematopoiesis and myeloid malignancies. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76(13):2511‐2523. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03084-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saika M, Inoue D, Nagase R, et al. ASXL1 and SETBP1 mutations promote leukaemogenesis by repressing TGFβ pathway genes through histone deacetylation. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):15873. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33881-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nagase R, Inoue D, Pastore A, et al. Expression of mutant Asxl1 perturbs hematopoiesis and promotes susceptibility to leukemic transformation. J Exp Med. 2018;215(6):1729‐1747. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Coombs CC, Zehir A, Devlin SM, et al. Therapy‐related clonal hematopoiesis in patients with non‐hematologic cancers is common and associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21(3):374‐382.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bolton KL, Ptashkin RN, Gao T, et al. Cancer therapy shapes the fitness landscape of clonal hematopoiesis. Nat Genet. 2020;52(11):1219‐1226. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-00710-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jaiswal S, Ebert BL. Clonal hematopoiesis in human aging and disease. Science. 2019;366(6465):eaan4673. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jaiswal S, Natarajan P, Silver AJ, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(2):111‐121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pan W, Zhu S, Qu K, et al. The DNA methylcytosine dioxygenase Tet2 sustains immunosuppressive function of tumor‐infiltrating myeloid cells to promote melanoma progression. Immunity. 2017;47(2):284‐297.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li S, Feng J, Wu F, et al. tet 2 promotes anti‐tumor immunity by governing G‐ mdsc s and cd 8 + T‐cell numbers. EMBO Rep. 2020;21(10):e49425. doi: 10.15252/embr.201949425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nguyen YTM, Fujisawa M, Nguyen TB, et al. Tet2 deficiency in immune cells exacerbates tumor progression by increasing angiogenesis in a lung cancer model. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:4931‐4943. Published online October 28, 2021:cas.15165. doi: 10.1111/cas.15165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. de Boer J, Williams A, Skavdis G, et al. Transgenic mice with hematopoietic and lymphoid specific expression of Cre. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33(2):314‐325. doi: 10.1002/immu.200310005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Clausen BE, Burkhardt C, Reith W, Renkawitz R, Förster I. Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using LysMcre mice. Transgenic Res. 1999;8(4):265‐277. doi: 10.1023/a:1008942828960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Takahama Y, Ohishi K, Tokoro Y, et al. Functional competence of T cells in the absence of glycosylphosphatidylinositol‐anchored proteins caused by T cell‐specific disruption of the Pig‐agene. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2159‐2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fantozzi A, Christofori G. Mouse models of breast cancer metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(4):212. doi: 10.1186/bcr1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Davie SA, Maglione JE, Manner CK, et al. Effects of FVB/NJ and C57Bl/6J strain backgrounds on mammary tumor phenotype in inducible nitric oxide synthase deficient mice. Transgenic Res. 2007;16(2):193‐201. doi: 10.1007/s11248-006-9056-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12(4):357‐360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. The R package Rsubread is easier, faster, cheaper and better for alignment and quantification of RNA sequencing reads. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(8):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139‐140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA‐sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16(5):284‐287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhao L, He R, Long H, et al. Late‐stage tumors induce anemia and immunosuppressive extramedullary erythroid progenitor cells. Nat Med. 2018;24(10):1536‐1544. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0205-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lanzer KG, Johnson LL, Woodland DL, Blackman MA. Impact of ageing on the response and repertoire of influenza virus‐specific CD4 T cells. Immun Ageing. 2014;11(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-11-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aiello A, Farzaneh F, Candore G, et al. Immunosenescence and its hallmarks: how to oppose aging strategically? A review of potential options for therapeutic intervention. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2247. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mittelbrunn M, Kroemer G. Hallmarks of T cell aging. Nat Immunol. 2021;22(6):687‐698. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-00927-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li J, Li L, Sun X, et al. Role of Tet2 in regulating adaptive and innate immunity. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:665897. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.665897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jiang S. Tet2 at the interface between cancer and immunity. Commun Biol. 2020;3(1):667. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-01391-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fraietta JA, Nobles CL, Sammons MA, et al. Disruption of TET2 promotes the therapeutic efficacy of CD19‐targeted T cells. Nature. 2018;558(7709):307‐312. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0178-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cull AH, Snetsinger B, Buckstein R, Wells RA, Rauh MJ. Tet2 restrains inflammatory gene expression in macrophages. Exp Hematol. 2017;55:56‐70.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fuster JJ, MacLauchlan S, Zuriaga MA, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis associated with TET2 deficiency accelerates atherosclerosis development in mice. Science. 2017;355(6327):842‐847. doi: 10.1126/science.aag1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cook EK, Izukawa T, Young S, et al. Comorbid and inflammatory characteristics of genetic subtypes of clonal hematopoiesis. Blood Adv. 2019;3(16):2482‐2486. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sano S, Oshima K, Wang Y, Katanasaka Y, Sano M, Walsh K. CRISPR‐mediated gene editing to assess the roles of Tet2 and Dnmt3a in clonal hematopoiesis and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2018;123(3):335‐341. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Arends CM, Galan‐Sousa J, Hoyer K, et al. Hematopoietic lineage distribution and evolutionary dynamics of clonal hematopoiesis. Leukemia. 2018;32(9):1908‐1919. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0047-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fujino T, Kitamura T. ASXL1 mutation in clonal hematopoiesis. Exp Hematol. 2020;83:74‐84. 10.1016/j.exphem.2020.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1

Fig S2

Fig S3

Supplementary Material