Abstract

Two Mycobacterium leprae genes, folP1 and folP2, encoding putative dihydropteroate synthases (DHPS), were studied for enzymatic activity and for the presence of mutations associated with dapsone resistance. Each gene was cloned and expressed in a folP knockout mutant of Escherichia coli (C600ΔfolP::Kmr). Expression of M. leprae folP1 in C600ΔfolP::Kmr conferred growth on a folate-deficient medium, and bacterial lysates exhibited DHPS activity. This recombinant displayed a 256-fold-greater sensitivity to dapsone (measured by the MIC) than wild-type E. coli C600, and 50-fold less dapsone was required to block (expressed as the 50% inhibitory concentration [IC50]) the DHPS activity of this recombinant. When the folP1 genes of several dapsone-resistant M. leprae clinical isolates were sequenced, two missense mutations were identified. One mutation occurred at codon 53, substituting an isoleucine for a threonine residue (T53I) in the DHPS-1, and a second mutation occurred in codon 55, substituting an arginine for a proline residue (P55R). Transformation of the C600ΔfolP::Kmr knockout with plasmids carrying either the T53I or the P55R mutant allele did not substantially alter the DHPS activity compared to levels produced by recombinants containing wild-type M. leprae folP1. However, both mutations increased dapsone resistance, with P55R having the greatest affect on dapsone resistance by increasing the MIC 64-fold and the IC50 68-fold. These results prove that the folP1 of M. leprae encodes a functional DHPS and that mutations within this gene are associated with the development of dapsone resistance in clinical isolates of M. leprae. Transformants created with M. leprae folP2 did not confer growth on the C600ΔfolP::Kmr knockout strain, and DNA sequences of folP2 from dapsone-susceptible and -resistant M. leprae strains were identical, indicating that this gene does not encode a functional DHPS and is not involved in dapsone resistance in M. leprae.

Prior to the development and implementation of multidrug therapy (MDT) for leprosy using dapsone, rifampin, and clofazamine, most patients were treated with dapsone monotherapy. During this period dapsone-resistant strains of Mycobacterium leprae were identified and dapsone-resistant leprosy became a significant problem for leprosy control programs (15, 17, 28). Currently recommended control measures for treating leprosy with MDT should control the spread of drug-resistant strains; however, dapsone resistance continues to be reported even in areas of the world with successful implementation of MDT (1, 6).

Comprehensive estimates of drug resistance in leprosy are difficult to obtain because of the cumbersome nature of the drug screening method (30). Advances in the elucidation of molecular events responsible for drug resistance in mycobacteria have allowed the development of new tools for drug resistance screening (3, 7, 21, 35, 36). Application of these tools has revealed the presence of both monoresistant (18, 35) and multidrug-resistant strains of M. leprae (18). Recently, point mutations in the putative M. leprae gene for dihydropteroate synthase (folP) have been identified in dapsone-resistant strains of M. leprae (19, 38); however, definitive evidence linking these mutations with dapsone resistance and proof of enzymatic activity of the putative dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS) of M. leprae have not been found. A fuller understanding of the mechanism of action of dapsone and modes of resistance present in M. leprae should facilitate the development of new tools for monitoring dapsone resistance and lead to investigations into new strategies to circumvent dapsone resistance.

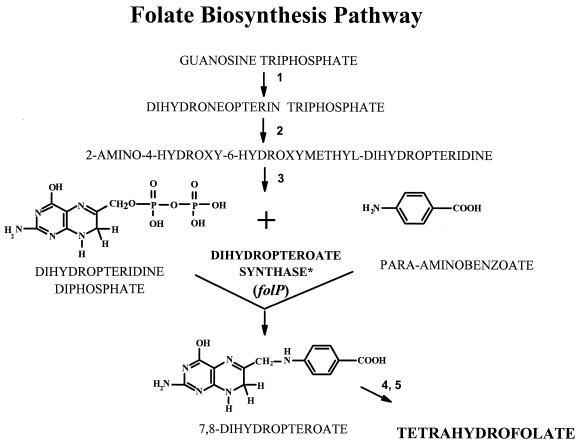

Dapsone, 4,4-diaminodiphenylsulfone, is a synthetic sulfone with effective antileprosy activity (16). Because the antibacterial activity of dapsone is inhibited by para-aminobenzoate (PABA), it is thought that dapsone has a mechanism of action similar to that of the sulfonamides, which involves inhibition of folic acid synthesis. Sulfonamides block the condensation of PABA and 7,8-dihydro-6-hydroxymethylpterin-pyrophosphate to form 7,8-dihydropteroate (Fig. 1). The key bacterial enzyme in this step is DHPS, encoded by folP (8, 13). The subsequent conversion of 7,8-dihydropteroate to tetrahydrofolate by dihydrofolate synthase and dihydrofolate reductase is critical to the formation of various cellular cofactors including thymidylate, glycine, methionine, pantothenic acid, and n-formylmethionyl-tRNA. The mechanism of dapsone resistance in M. leprae is thought to be associated with DHPS in a manner similar to the mechanism of resistance developed in other bacteria to the sulfonamides (22, 24, 29). Genome analysis of M. leprae has identified two folP homologs (folP1 and folP2), both of which contain significant sequence homology with other bacterial folP genes, as well as conserved regions found in many DHPS molecules (see Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Folate biosynthetic pathway with proposed sites for dapsone and sulfonamide inhibitory action (11). Numbers represent enzymes in the pathway: 1, guanosine triphosphate hydrolase; 2, dihydroneopterin aldolase; 3, dihydropteridine pyrophosphokinase; 4, dihydrofolate synthase; 5, dihydrofolate reductase. The asterisk indicates the step in which sulfonamides and dapsone compete with PABA in the DHPS reaction.

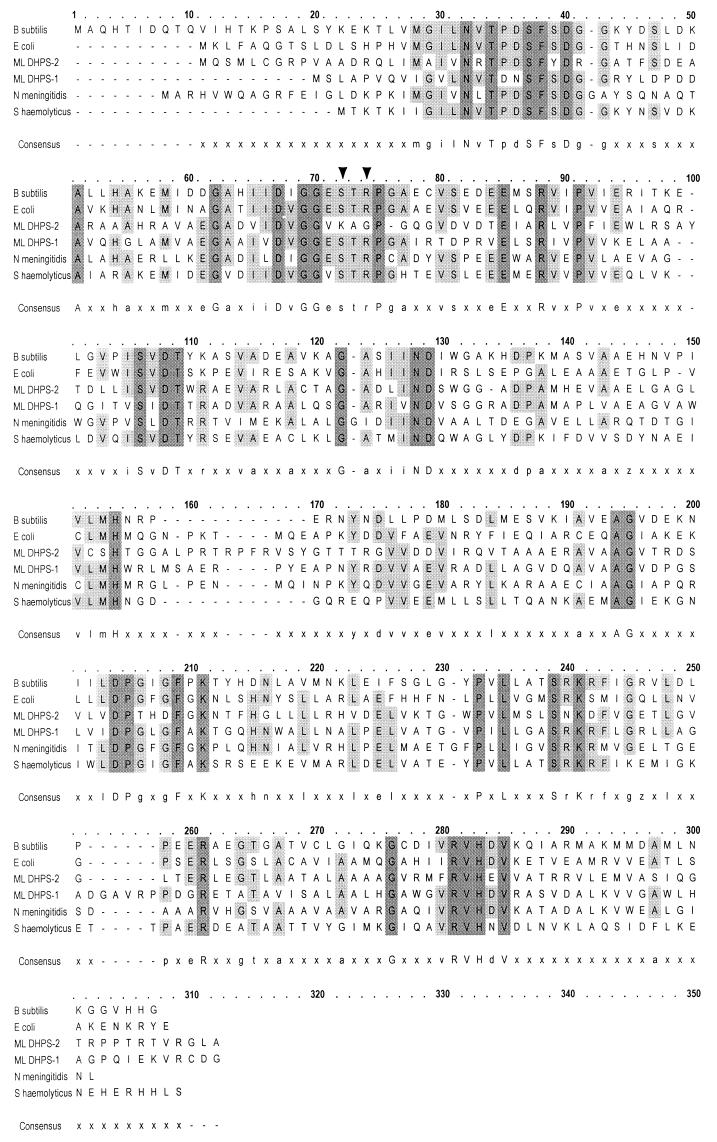

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of DHPSs from B. subtilis (31), E. coli (5), Neisseria meningitidis (8), and Staphylococcus haemolyticus (20) with those of M. leprae DHPS-1 and DHPS-2. Domains associated with DHPS enzymes were identified from the Prosite database (14) and were PS00792 (bases 28 to 41) and PS00793 (bases 65 to 77). Arrowheads mark M. leprae amino acid 53 (B. subtilis amino acid 72) and base 55 (B. subtilis base 74), associated with dapsone resistance in M. leprae. Multiple sequence alignments were done on OMIGA 2.0, Oxford Molecular Group, Inc., Campbell, Calif.

The work described in this study provides evidence that M. leprae folP1, but not folP2, encodes a functional DHPS enzyme which is effectively inhibited by low levels of dapsone. We have also identified mutations in folP1 associated with dapsone resistance. Characterization of these mutations indicated that dapsone resistance in M. leprae was related to missense mutations in folP1 which affected the inhibitory action of dapsone on DHPS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genomic annotation of folP1 and folP2.

M. leprae folP1 is found on cosmid MLCB2548 (AL023093) and is accessible through the Sanger Centre (Cambridge, England) website (www.sanger.ac.uk). M. leprae folP2 is found on cosmid B1912 (U15180) and is accessible through Genome Therapeutics Corp. (Waltham, Mass.) website (www.genomecorp.com).

Bacterial strains.

Dapsone-resistant and -susceptible strains of M. leprae were originally obtained from leprosy patients from the Anandaban Leprosy Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal, and from G. W. Long Hansen's Disease Center, Carville, La. (Table 1). Resistance to dapsone was determined in the mouse footpad system by Shepard's kinetic method (30), and dapsone-resistant strains, except SA26, were propagated thereafter in the footpads of BALB/c mice fed appropriate concentrations of dapsone ad libitum. SA26 was analyzed directly from a patient's skin biopsy specimen. Dapsone-resistant strains grew in footpads of mice receiving either 0.001 or 0.01% dapsone as a percentage of the weight of mouse chow. These dapsone concentrations are 10- and 100-fold, respectively, above the minimal effective dose (MED) for susceptible strains of M. leprae. Thai-53, a dapsone-susceptible strain of M. leprae, was the kind gift of M. Matsuoka, Leprosy Research Center, National Institute of Infectious Disease, Higashimurayama, Tokyo, Japan. The WHO DNA was purified from armadillo-grown M. leprae which originated from pooled biopsies of lepromatous leprosy patients from India and was kindly provided by M. J. Colston, National Institute for Medical Research, Mill Hill, London, United Kingdom.

TABLE 1.

M. leprae strains used in this study

| Strain | Dapsone susceptibilitya | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Thai-53 | Susceptible | Thailand |

| WHO | Susceptible | India |

| 2898 | Resistant (0.01) | United States |

| 591 | Resistant (0.01) | Nepal |

| SA26 | Resistant (0.01) | United States |

| 569 | Resistant (0.001) | Nepal |

Measured in the mouse foot pad assay. Values in parentheses represent the maximum doses of dapsone (as percentages of the weight of food) at which M. leprae grew. Susceptible strains did not grow at 0.0001% dapsone.

Bacteria were harvested from ethanol-fixed tissues following a 60-min rehydration in 10 mM Tris–1 mM EDTA buffer, pH 7.4 (TE). Rehydrated tissue was minced with scissors to a gelatinous consistency, resuspended in 0.3 ml of TE, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The specimen was thawed at 95°C, and the freeze-thaw treatment was repeated twice. The tissue was digested for 18 h at 60°C with proteinase K (2.5 mg/ml) in 100 mM Tris–150 mM NaCl–10 mM EDTA (pH 7.4) digestion buffer. Proteinase K was heat inactivated at 95°C for 10 min, and DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol as described previously (34). The precipitated DNA was resuspended in 30 μl of TE buffer.

Escherichia coli strain C600, the folP knockout C600ΔfolP::Kmr (obtained from G. Swedberg, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden [9]), and C600ΔfolP::Kmr recombinants were propagated in either 2× Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, Mo.) or Mueller-Hinton medium (Difco, Detroit, Mich.). E. coli XL-1 Blue cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) were grown in standard-concentration LB medium.

Cloning of folP homologs and complementation of folP knockout mutants.

The folP1 and folP2 genes were amplified from Thai-53 by PCR with primers folP1-7 and -8 and folP2-1 and -2 (Table 2), respectively. These primers incorporated BamHI tails on the 5′ ends, and EcoRI tails on the 3′ ends, of the PCR fragments. The resultant PCR fragments were digested with BamHI and EcoRI and cloned into the multiple cloning site of pUC18 to create in-frame lacZ translational fusions with folP1 (pML101) and folP2 (pML201). E. coli XL-1 Blue cells were transformed with these plasmids, and recombinant clones were selected on LB agar containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml. Clones containing M. leprae folP1 or folP2 were identified by PCR amplification of the respective gene from crude cell lysates of selected bacterial colonies using folP1-7 and -8 and folP2-1 and -2. The resultant PCR fragments were purified and concentrated using a QIAQuick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, Calif.), and DNA sequences were obtained by automated sequencing on a PE BioSystems 377 automated DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer, Gaithersburg, Md.). Plasmids from appropriate clones were purified using a QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (QIAGEN), and competent E. coli C600ΔfolP::Kmr cells were transformed. Recombinants were selected on 2× LB agar containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml, 50 μg of kanamycin/ml, and 1 mM isopropylthiogalactoside (IPTG). The presence of M. leprae folP1 or folP2 in recombinant clones was confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing as described above. Several clones from each transformation were then streaked on Mueller-Hinton agar containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml, 50 μg of kanamycin/ml, and 1 mM IPTG to select for growth complementation. Mueller-Hinton medium is a PABA- and thymine/thymidine-deficient medium, which will not support the growth of E. coli C600ΔfolP::Kmr. The presence of an inactivated chromosomal copy of E. coli folP in E. coli C600ΔfolP::Kmr recombinant clones was verified using PCR with EC2 and EC3 primers (Table 2) to ensure that growth was a result of the cloned folP gene (8).

TABLE 2.

Primers used to study M. leprae folP1 and folP2

| Primer | Sequencea | Location (bp) | Application(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| folP1-1 | 5′ TGATGCTGCTTCTCGTGC 3′ | 28–45 upstream of GTG start | PCR, sequencing of folP1 |

| folP1-2 | 5′ AAGTCTTGTCCGTTGGCG 3′ | 61–78 downstream of TAG stop | |

| folP1-9 | 5′ AGGCCGTGCTGGACAGC 3′ | 91–108 | Sequencing of folP1 |

| folP1-20 | 5′ CGTCAACGATGTGTCT 3′ | 308–323 | |

| folP1-7 | 5′ CCGGAATTCCGTGAGTTTGGCG 3′ | 1–12 + EcoRI site | PCR, RT-PCR, cloning of folP1 |

| folP1-8 | 5′ GCGGGATCCGTCAGCCATCACATC 3′ | 842–856 + BamHI site | |

| folP1-21 | 5′ CCGGTGCCATTAGGACCGA 3′ | 164–182 | Site-directed mutagenesis of folP1 (T53I) |

| folP1-22 | 5′ GCCGGATCGATTCGCCACCG 3′ | 147–163 | |

| folP1-23 | 5′ CGACCCCGGCGCGGTGCCAT 3′ | 155–173 | Site-directed mutagenesis of folP1 (P55R) |

| folP1-24 | 5′ ATTCGCCACCGACGTCGA 3′ | 137–154 | |

| folP2-1 | 5′ CCGGAATTCCGTGCAGTCAAT 3′ | 1–11 + EcoRI site | PCR, RT-PCR, cloning of folP2 |

| folP2-2 | 5′ GCGGGATCCGTCATGCGAGT 3′ | 866–878 + BamHI site | |

| folP2-3 | 5′ GATGTGATTCGCCAGG 3′ | 492–507 | Sequencing of folP2 |

| folP2-4 | 5′ CGAATCACATCGTCCACCAC 3′ | 483–502 | |

| EC2 | 5′ TGGAATTCTTATCAATTCATACCAGGG 3′ | 35–9 upstream of ATG start | PCR of E. coli folP |

| EC3 | 5′ GGAGATCTACACGACCACGAATCCCATC 3′ | 20–47 downstream of TAA stop |

Mutated nucleotides are underlined.

DNA sequencing of dapsone-resistant and -susceptible strains of M. leprae.

The entire folP1 and folP2 genes were amplified separately by PCR from DNA preparations of dapsone-susceptible and -resistant strains of M. leprae using primer set folP1-1 and -2 or folP2-1 and -2, respectively (Table 2). PCR fragments were purified, and the DNA sequence of folP1 was obtained using primers folP1-1, folP1-2, folP1-9, and folP1-20. The folP2 sequence was obtained using primers folP2-1, folP2-2, folP2-3, and folP2-4. The folP1 and folP2 sequences from each strain were compared to those of dapsone-susceptible M. leprae strains found in the Sanger Centre and Genome Therapeutics M. leprae genome databases.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Mutant sequences found in folP1 of M. leprae dapsone-resistant strains were substituted for wild-type sequences in the folP1 contained on pML101 by PCR site-directed mutagenesis (37) using either folP1-21 and folP1-22 or folP1-23 and folP1-24 (Table 2). The resultant plasmids, pML102 (containing the folP1 T53I mutant allele) and pML103 (containing the folP1 P55R mutant allele), were transformed separately into E. coli XL-1 Blue. Recombinant clones were selected on 2× LB medium containing kanamycin and ampicillin. Plasmid DNA was purified from selected clones, and C600ΔfolP::Kmr cells were transformed with either pML102 and pML103. Recombinants were selected on 2× LB medium containing kanamycin and ampicillin, and mutations were identified by DNA sequencing as described above. The entire folP1 gene was sequenced from recombinant clones found to contain the desired mutant alleles.

DHPS assay.

DHPS activity was measured by incorporation of radioactivity from 14C-labeled PABA into dihydropteroate as described previously (9). Briefly, E. coli C600, C600ΔfolP::Kmr, and recombinant strains of C600ΔfolP::Kmr were grown in 2× LB medium containing 1 mM IPTG, 100 μg of ampicillin/ml, and 50 μg of kanamycin/ml until cultures reached an optical density at 660 nm (OD660) of 1.0. Cells were collected by centrifugation and washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.6. Cells were resuspended in sonication buffer (2), disrupted by sonication at 4°C, and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h, and the protein concentration of the supernatant fraction (cell lysate) was determined (26). One hundred microliters of cell lysate (100 μg of protein) was combined with 14C-labeled PABA, diphosphoric acid, and mono[(2-amino1,4,7,8-tetrahydro-4-oxo-6-pteridinyl)-methyl]ester (a gift from M. Nasr, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Rockville, Md.) in Tris buffer, pH 8.3, containing dithiothreitol and MgCl2 in a 200-μl reaction volume, and the mixture was held at 37°C for 15 min. One hundred microliters of each reaction volume was spotted onto 3MM paper (Whatman International, Ltd., Maidstone, England), and ascending chromatography was performed in 0.01 M phosphate buffer. Under these conditions, free substrate (14C-labeled PABA) migrates with the solvent front and radiolabeled product (14C-labeled dihydropteroate) remains at the origin. The chromatogram was dried, the area (1 cm2) representing the origin was placed into scintillation fluid, and radioactivity was measured using an LS 6000IC Liquid Scintillation System (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, Calif.). Results were expressed as the mean and standard deviation of triplicate samples in picomoles of product formed per milligram of total protein. Buffer and medium (2× LB) were substituted in the assay for cell lysate and served as negative controls.

Dapsone inhibition studies.

The effect of dapsone on DHPS activity was determined using the DHPS assay as described above. Briefly, increasing concentrations of dapsone (0.002 to 20 μg) were added to cell lysates (100 μg of protein) and DHPS activity assay reagents in a final volume of 200 μl and were incubated at 37°C for 15 min. One hundred microliters of each reaction volume was spotted onto Whatman 3 MM paper, ascending chromatography was performed, and radioactivity measurements were determined. Results were expressed as the concentration of dapsone which inhibited product formation by 50% (IC50) compared to that in untreated cell lysates. All values were corrected by subtracting background counts observed with negative controls containing DHPS assay reagents with either 5% ethanol or 2× LB medium with 5% ethanol. Ethanol was included in the controls to mimic solvent concentrations used for dapsone-containing samples.

Dapsone susceptibility testing.

The MICs for E. coli 600 and E. coli C600ΔfolP::Kmr recombinant clones were determined by culture on Mueller-Hinton agar plates containing twofold serial dilutions of dapsone (0.025 to 256 μg/ml) and 1 mM IPTG. The MIC for each strain was defined as the lowest concentration of dapsone needed to inhibit bacterial growth.

Purification of RNA.

RNA was isolated from 1010 M. leprae bacteria which were propagated in and purified from the hind footpads of athymic nude mice (Hsd:athymic Nude-nu; Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Indianapolis, Ind.). The bacteria were resuspended in LETS buffer (200 mM LiCl, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.8], 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate), frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C. Bacteria were thawed on ice, and total RNA was purified as previously described (27). Chromosomal DNA was removed from RNA extracts by adding 1 U of RNase-free DNase I (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) in 0.025 M Tris, pH 7.5, containing 0.025 M MgCl2 and incubating the mixture at 25°C for 15 min. DNase I was inactivated by adding 5 μl of 0.2 M EDTA and incubating the mixture at 65°C for 10 min. RNA was quantified using a GeneQuant RNA/DNA Calculator Spectrophotometer (Pharmacia Biotech, Cambridge, England), and RNA samples were stored at −70°C in 500-ng/μl aliquots.

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

cDNA was prepared by adding 1 μl of RNA, 11.5 μl of RNAse-free water, and 1 μl of primer (20 pmol), either folP1-7 or folP2-1, in a sterile 0.5-ml PCR tube and heating for 2 min at 70°C in a thermal cycler. The reactants were quenched rapidly on ice; then 6.5 μl of PCR Master Mix (Advantage RT for PCR kit; Clontech) containing 4.0 μl of 5× reaction buffer, 1.0 μl of a deoxynucleoside triphosphate mixture (10 mM each), 0.5 μl of recombinant RNase inhibitor, and 1.0 μl of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase was added. The reactants were incubated at 42°C for 60 min, then at 94°C for 5 min, and were cooled to 25°C, and 80 μl of RNase-free water was added. The contents of the tube were mixed using a vortex mixer and centrifuged briefly in a microcentrifuge. The purified cDNA samples were stored at −70°C. M. leprae folP1 and folP2 were amplified by PCR using 5 μl of cDNA and primer pairs folP1-7–folP1-8 and folP2-1–folP2-2, respectively (Table 2).

RESULTS

M. leprae folP homologs.

Deduced amino acid sequence alignments of putative DHPS enzymes from M. leprae (DHPS-1 and -2) and four representative bacterial species showed that both homologs of M. leprae were similar in size and contained consensus patterns associated with this class of enzyme (Fig. 2). A total-sequence comparison of M. leprae DHPS-1 with DHPS-2 showed only 45% identity. Comparison of the two M. leprae polypeptides through the first highly homologous region, PS00792 of Bacillus subtilis (bases 28 to 41) (Fig. 2), showed a relatively low degree of relatedness, with only 5 of 14 amino acids shared. In contrast, comparisons between DHPS-1 or -2 and the consensus sequence of this region showed a higher percentage of identity (64%). The second region of homology, PS00793, which is located between residues 65 and 77 of B. subtilis (Fig. 2), showed strong homology (92.3%) between M. leprae DHPS-1 and the consensus sequence, based on the other bacterial DHPS proteins in the alignment. The only change in the M. leprae DHPS-1 sequence was at residue 66, where valine was found in place of either leucine or isoleucine in at least one other bacterium. In contrast, M. leprae DHPS-2 shared only 6 of 13 (46.2%) residues in this region, with major differences in amino acids from residue 71 to 77. The latter amino acid residues encompass the region where mutations in dapsone-resistant M. leprae were identified and linked to dapsone resistance in this study.

Mutations associated with dapsone resistance.

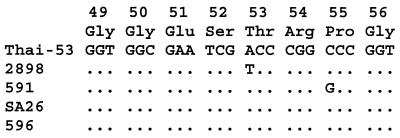

Full-length DNA sequencing of folP1 and folP2 from four dapsone-resistant strains of M. leprae was carried out (Table 1). All dapsone-resistant strains produced folP2 DNA sequences identical to those of the folP2 from the dapsone-susceptible M. leprae strain Thai-53 (data not shown). Two strains (2898 and 591) revealed missense mutations associated with folP1 when compared to the folP1 of M. leprae Thai-53 (Fig. 3). A single-base mutation (ACC→ATC) was found in codon 53 (M. leprae numbering) (Fig. 2) of strain 2898 substituting an isoleucine residue for a threonine (T53I) in DHPS (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Alignment of folP1 DNA from five strains of M. leprae corresponding to deduced amino acids 49 through 56 of DHPS. Dots indicate nucleotide bases identical with the dapsone-susceptible strain, Thai-53, sequence, and missense mutations are identified by appropriate letters.

A separate and distinct folP1 mutation (CCC→CGC) was found in codon 55 (M. leprae numbering) (Fig. 2) of another high-level (0.01%) dapsone-resistant strain, M. leprae 591 (Fig. 3). The missense mutation in M. leprae 591 substituted an arginine for proline (P55R) in DHPS-1. Each of the above two mutations was created in M. leprae folP1 by site-directed mutagenesis, and the mutant sequences were cloned into C600ΔfolP::Kmr for subsequent expression and characterization of mutant enzymes. Mutation T53I was in pML102, and mutation P55R was in pML103 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Growth, DHPS activity, and dapsone inhibition of E. coli C600 and recombinant strains

| E. coli strain | Growtha | DHPS activity (pmol/mg)b | Dapsone IC50c (μg/ml) | Dapsone MICd (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C600 | + | 370 ± 16.6 | 3.0 | >256 |

| C600ΔfolP::Kmr | − | 9.8 ± 1.2 | ND | ND |

| C600ΔfolP::Kmr(pUC18) | − | 10.3 ± 0.8 | ND | ND |

| C600ΔfolP::Kmr(pML101) | + | 48.7 ± 4.2 | 0.06 | 1 |

| C600ΔfolP::Kmr(pML201) | − | 5.5 ± 0.3 | ND | ND |

| C600ΔfolP::Kmr(pML102) | + | 62.1 ± 1.4 | 0.11 | 10 |

| C600ΔfolP::Kmr(pML103) | + | 60.9 ± 5.4 | 4.1 | 64 |

Bacterial growth on Mueller-Hinton agar. +, growth; −, no growth.

Values are means ± standard deviations.

Dapsone concentration inhibiting 50% of DHPS activity. ND, not determined.

On Mueller-Hinton agar.

No mutations in folP1 were observed in two dapsone-susceptible strains of M. leprae with MEDs of 0.0001% dapsone (Table 1). In addition, no mutations in folP1 were seen in two dapsone-resistant strains of M. leprae (SA26, resistant at 0.01% dapsone, and 569, resistant at 0.001% dapsone), suggesting that there are other mechanisms of resistance to dapsone in M. leprae not associated with mutations in folP1.

Growth complementation and DHPS activity in crude bacterial lysates.

Having shown the similarity between potential DHPS proteins of M. leprae and those of other bacteria, we cloned the two putative M. leprae DHPS genes into plasmids and transformed them into an E. coli folP knockout mutant for further characterization. To ensure that enzymatic activity was a function of cloned M. leprae folP genes, all recombinants were tested by PCR and showed the predicted 1.8-kb amplification product corresponding to the kanamycin-disrupted E. coli folP gene (data not shown) (8).

Bacterial lysates prepared from each strain were normalized for protein content (100 μg) and tested for DHPS activity. E. coli C600 produced the highest enzymatic activity at 370 pmol/mg; inactivation of the native folP by insertional mutagenesis (C600ΔfolP::Kmr) reduced this activity approximately 38-fold, to 9.8 mol/mg, and was a lethal mutation when bacteria were plated on Mueller-Hinton agar (Table 3). Transformation of C600ΔfolP::Kmr with pUC18 did not confer growth competence on the knockout strain on Mueller-Hinton agar, nor did it change the level of DHPS activity significantly. Transformation of the E. coli folP knockout with pML101 (containing wild-type M. leprae folP1) did confer growth competence on Mueller-Hinton agar, and lysates from this strain produced 48.7 pmol of DHPS activity/mg. Recombinants carrying mutations in M. leprae folP1 (pML102 and pML103) conferred growth competence on the knockout strain and produced levels of DHPS activity similar to that of the pML101 strain (Table 3). In contrast to M. leprae folP1 transformants, transformants carrying M. leprae folP2 were unable to complement growth on Mueller-Hinton agar and lysates produced low levels of DHPS activity similar to that of the knockout strain, even though DNA sequencing confirmed in-frame cloning of folP2 (Table 3).

Inhibition of DHPS activity and of growth of bacteria by dapsone.

Dapsone was tested for its ability to inhibit the DHPS activity of bacterial lysates from each strain. In addition, E. coli C600 and each recombinant strain were tested for growth on Mueller-Hinton agar containing various concentrations of dapsone. The IC50 of dapsone in a DHPS activity assay for E. coli C600 was 3.0 μg/ml. In contrast, for the recombinant strain carrying M. leprae folP1 (pML101), dapsone showed an IC50 of 0.06 μg/ml and a MIC of 1 μg/ml. This represents approximately a 50-fold-greater sensitivity to dapsone of M. leprae DHPS compared to E. coli DHPS; when measured by the MIC, the difference in sensitivity was even greater (>256-fold for M. leprae DHPS compared to E. coli DHPS). Growth of E. coli C600 was not inhibited at 256 μg of dapsone/ml, which was the highest concentration that could be tested due to the solubility properties of dapsone at concentrations above this level (Table 3).

folP1 mutants (pML102 and pML103), encoding single-amino-acid changes in DHPS-1, affected both the IC50 of dapsone in the DHPS assay and the respective dapsone MICs (Table 3) compared to those for E. coli carrying the M. leprae folP1 (pML101). For example, for recombinant strain C600ΔfolP::Kmr (pML102) carrying the T53I mutation, the dapsone MIC showed a 10-fold increase and the IC50 showed almost a 2-fold increase. The P55R mutation in C600ΔfolP::Kmr (pML103) had a much greater effect on sensitivity to dapsone, as measured by the IC50 and MIC (Table 3). The IC50 for this mutant was increased 68-fold over that for the wild type, and the MIC for the mutant was 64 μg/ml compared to 1 μg/ml observed with the recombinant strain expressing the wild-type M. leprae folP1. Taken together, these findings provide evidence that M. leprae folP1 mutations P55R and T53I affect the inhibitory action of dapsone on M. leprae, thereby accounting for the resistance to dapsone observed in M. leprae strains 591 and 2898, respectively.

Expression of folP homologs in M. leprae.

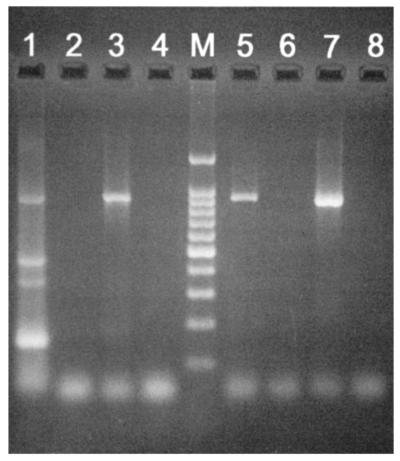

RT-PCR analysis of purified M. leprae RNA was performed to determine whether folP1 and folP2 were transcribed in M. leprae. Analysis of cDNA showed that an 863-bp fragment, corresponding to the correct length for M. leprae folP2 mRNA, was obtained when amplification was carried out with M. leprae folP2-specific primers (Fig. 4, lane 1). Similarly, an 856-bp fragment, corresponding to M. leprae folP1 mRNA, was obtained with M. leprae folP1-specific primers (Fig. 4, lane 5). PCR analysis of DNase-treated RNA using either set of primers yielded no amplification products, indicating that no detectable chromosomal DNA was present in the total-RNA preparation (Fig. 4, lanes 2 and 6).

FIG. 4.

Analysis of folP1 and folP2 RNA transcripts by RT-PCR and agarose gel electrophoresis. Size analysis of PCR amplicons showed that an 863-bp fragment, corresponding to the correct size for M. leprae folP2 mRNA, was obtained when amplification was carried out with M. leprae folP2-specific primers (lane 1). Similarly, an 856-bp fragment, corresponding to M. leprae folP1 mRNA, was obtained with M. leprae folP1-specific primers (lane 5). No PCR products were produced when DNase-treated RNA (prior to cDNA conversion) was tested using either folP1- or folP2-specific primers (lanes 2 and 6, respectively). Lanes 3 and 7 contained folP2 and folP1 amplicons from purified DNA of M. leprae, respectively. Lanes 4 and 8 contained negative buffer controls. Lane M, 100-bp DNA ladder (Promega, Madison, Wis.).

DISCUSSION

Seminal work by Kulkarni and Seydel showed that dapsone inhibited folate synthesis in cell extracts of M. leprae (22). Their work suggested that the heightened sensitivity of M. leprae DHPS was due to the high affinity of the enzyme for dapsone. Much of this work focused on analysis of extracts from Mycobacterium lufu, a mycobacterium known to exhibit dapsone susceptibility similar to that of M. leprae. M. lufu provided a surrogate for M. leprae in which studies could be performed on dapsone's effect on folate biosynthesis and dapsone analogs could be screened for new, more effective sulfones.

Recent developments in the M. leprae genome project have fostered a more direct approach to studying the biochemical and genetic basis of metabolism and cellular physiology of M. leprae. Newly annotated open reading frames have provided insight into the genetic potential of M. leprae, facilitating studies on the modes of action of antimycobacterial drugs and mechanisms of drug resistance. We utilized genomic information to identify potential folP homologs of M. leprae with the idea of studying both the effect of dapsone on DHPS activity and the nature of resistance to dapsone in M. leprae.

Annotation of the M. leprae genome identified two folP homologs, folP1 and folP2, which appeared to encode DHPS enzymes with conserved regions found in DHPS enzymes of other microorganisms (31, 33). Within cosmid MLCB2548, folP1 is located in what appears to be an operon containing other genes encoding enzymes related to folate biosynthesis, including folK, folB, and folE. folP2 is located within cosmid B1912 with two small, undefined open reading frames upstream of folP2, which apparently are not involved in folate biosynthesis. Streptococcus pneumoniae and B. subtilis provide examples of bacteria where folP is located in a folate operon (23, 31), whereas E. coli folP gives an example of the non-operon-associated genomic configuration (4). It is interesting that Mycobacterium tuberculosis displays an organization similar to that seen in M. leprae. For example, the M. tuberculosis homolog of M. leprae folP1 (MT 3712; 80% amino acid identity) is found in association with other folate genes, while a second M. tuberculosis folP homolog (MT1245; 86% amino acid homology to M. leprae folP2) is not.

Genetic and biochemical studies were done in E. coli because direct manipulation of M. leprae's enzymes and genes is encumbered primarily by our inability to cultivate the organism in vitro. To provide evidence that one or both M. leprae folP homologs produced a functional DHPS, each gene was cloned into the folP knockout mutant of E. coli. Only folP1 complemented the mutant for growth on Mueller-Hinton medium, indicating that folP1, and not folP2, encoded a functional DHPS enzyme. DNA sequencing of the recombinant plasmid pML201 (containing folP2 of M. leprae Thai-53) confirmed that folP2 was in the proper orientation and frame for expression as a lacZ fusion protein in E. coli (data not shown). It is important to remember that based on sequence similarity, M. leprae folP2 was a putative folP homolog (10). In addition, we provided evidence that folP2 was expressed in M. leprae based on RT-PCR of RNA extracts from viable organisms. Unfortunately, annotation built on generic similarities of various proteins is not always as sophisticated as intended, reminding us that laboratory confirmation of such hypotheses is imperative.

Analysis of DHPS activity from recombinants supported the findings of the growth complementation studies, showing that bacterial lysates from recombinants carrying pML101, and not pML201, contained a functional enzyme. DHPS activity levels for all growth-competent recombinants were approximately 15% of that seen with E. coli C600, possibly reflecting a difference in the functional efficiency of M. leprae's DHPS-1 expressed in E. coli. Enzyme kinetic studies on purified DHPS-1 from M. leprae should help define functional efficiencies of the wild-type and mutant forms of folP and better define the growth potential of M. leprae.

Resistance to dapsone in M. leprae is thought to be associated with DHPS in a manner similar to that of resistance developed in other bacteria to the sulfonamides (22, 29). Sulfonamide resistance in various bacterial species has been shown to be associated with mutations in folP (5, 9, 12, 25, 32). Some resistant mutants occur as a result of spontaneous mutations within the chromosomal copy of folP, while others appear to result from translocation events (8). In most cases, resistant organisms produce altered DHPS enzymes which continue to catalyze the condensation reaction to form dihydropteroate but are refractory to inhibition by sulfonamides.

Our sequencing results for folP1 from four dapsone-resistant strains of M. leprae identified two separate mutations associated with the mutant phenotype. The two mutations were localized to a highly conserved region of folP where mutations have been shown to affect susceptibility to sulfonamides in other bacteria (8, 12). The missense mutations were found only in two of the three high-level-resistant strains, 2898 and 591. The latter two strains were characterized for resistance in the mouse footpad assay and then propagated in mice under dapsone selection prior to DNA sequencing. The other high-level-resistant strain (SA26) was analyzed directly from a biopsy specimen taken from a patient who tested positive for dapsone resistance at the 0.01% level. Since strain SA26 and the low-level-resistant strain 569 showed the wild-type folP genotype, it is possible that other mechanisms may be responsible for dapsone resistance. In the case of SA26, an alternative explanation could be considered. Since SA26 originated from a patient's biopsy, the specimen may have contained a mixed culture of dapsone-resistant and dapsone-susceptible bacteria. If that was the case, then sequencing the mixed culture following PCR amplification of folP would produce the dominant species of DNA, which in this case would represent the wild-type, dapsone-susceptible folP gene.

Supportive evidence that the two missense mutations were responsible for dapsone resistance was acquired through site-directed mutagenesis of wild-type folP1. Recombinant mutants were constructed with either the T53I or P55R mutation. In both cases DHPS activity was slightly increased compared to that of M. leprae wild-type DHPS-1; however, significant changes were observed in the susceptibility of the mutated DHPS-1 enzymes to dapsone as measured by the IC50. Moreover, significant increases in dapsone resistance were observed when MICs obtained with strains carrying either plasmid pML101, pML102, or pML103 and wild-type E. coli C600 were compared.

Recently, Kai et al. (19) identified mutations within codons 53 and 55 of folP1 in six dapsone-resistant M. leprae strains. Three of these mutants contained a threonine-to-isoleucine mutation, and one strain showed a threonine-to-alanine mutation, at codon 53. The other three strains contained mutations at codon 55, with a proline-to-leucine mutation in folP1. Combining these results with ours shows that 8 of 10 (80%) dapsone-resistant clinical strains analyzed contained missense mutations within either codon 53 or 55 of folP1. Taken together, these results strongly suggest that mutations in this region (designated the sulfone resistance-determining region [SRDR]) of folP1 are responsible for the majority of the dapsone resistance found in M. leprae. Furthermore, should future studies confirm the association of these mutations as markers for dapsone resistance, a simple and rapid test could be developed that would detect the susceptible or resistant genotype. This test could be implemented as a leprosy control tool to survey populations thought to harbor dapsone-resistant strains and, thereby, to tailor treatment regimens appropriately.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Norman E. Morrison for helpful discussions and encouragement for pursuing this work. We also thank K. D. Neupane and S. Failbus for technical assistance.

The Anandaban Leprosy Hospital is supported by The Leprosy Mission International.

REFERENCES

- 1.Butlin C R, Neupane K D, Failbus S S, Morgan A, Britton W J. Drug resistance in Nepali leprosy patients. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1996;64:136–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chio L-C, Bolyard L A, Nasr M, Queener S F. Identification of a class of sulfonamides highly active against dihydropteroate synthase from Toxoplasma gondii, Pneumocystis carinii, and Mycobacterium avium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:727–733. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.3.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cockrill F R, III, Uhl J R, Temesgen Z, Zhang Y, Stockman L, Roberts G D, Williams D L, Kline B C. Rapid identification of a point mutation of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis catalase-peroxidase (katG) gene associated with isoniazid resistance. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:240–245. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dallas W S, Dev I K, Ray P H. The dihydropteroate synthase gene, folP, is near the leucine tRNA gene, leuU, on the Escherichia coli chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7743–7744. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.23.7743-7744.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dallas W S, Gowen J E, Ray P H, Cox M J, Dev I K. Cloning, sequencing, and enhanced expression of the dihydropteroate synthase gene of Escherichia coli MC4100. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5961–5970. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.18.5961-5970.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.dela Cruz E, Cellona R V, Balagon M V, Villahermosa L G, Fajardo T T, Jr, Abalos R M, Tan E V, Walsh G P. Primary dapsone resistance in Cebu, The Philippines: cause for concern. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1996;64:264–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delgado M B, Telenti A. Detection of fluoroquinolone resistance mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In: Persing D H, editor. PCR protocols for emerging infectious diseases. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fermer C, Kristiansen B-E, Skold O, Swedberg G. Sulfonamide resistance in Neisseria meningitidis as defined by site-directed mutagenesis could have its origin in other species. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4669–4675. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4669-4675.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fermer C, Swedberg G. Adaptation to sulfonamide resistance in Neisseria meningitidis may have required compensatory changes to retain enzyme function: kinetic analysis of dihydropteroate synthases from N. meningitidis expressed in a knockout mutant of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:831–837. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.831-837.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillis T P, Williams D L. Dapsone resistance is not associated with a mutation in the dihydropteroate synthase-2 gene of Mycobacterium leprae. Indian J Lepr. 1999;71:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grossman A. Folate and pterines. In: Michal G, editor. Biochemical pathways: an atlas of biochemistry and molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1999. p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hampele I C, D'Arcy A, Dale G E, Kostrewa D, Nielsen J, Oefner C, Page M G, Schonfeld H, Stuber D, Then R L. Structure and function of the dihydropteroate synthase from Staphylococcus aureus. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:21–30. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hitchings G H, Burchall J J. Inhibition of folate biosynthesis and function as a basis for chemotherapy. Adv Enzymol. 1965;27:417–422. doi: 10.1002/9780470122723.ch9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmann K, Bucher P, Falquet L, Bairoch A. The PROSITE database: its status in 1999. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:215–219. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobson R R, Hastings R C. Primary sulfone resistant leprosy. Int J Leprosy Other Mycobact Dis. 1978;46:116. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson R R. Treatment. In: Hastings R C, editor. Leprosy. New York, N.Y: Churchill Livingstone, Inc.; 1994. pp. 317–349. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji B. Drug resistance in leprosy—a review. Lepr Rev. 1985;56:262–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ji B, Jamet P, Soe S, Perani E G, Traore I, Grosset J H. High relapse rate among lepromatous leprosy patients treated with rifampin plus ofloxacin daily for 4 weeks. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1953–1956. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kai M, Matsuoka M, Nakata N, Maeda S, Gidoh M, Maeda Y, Hashimoto K, Kobayashi K, Kashiwabara Y. Diaminodiphenylsulfone resistance of Mycobacterium leprae due to mutations in the dihydropteroate synthase gene. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;177:231–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kellam P, Dallas W S, Ballantine S P, Delves C J. Functional cloning of the dihydropteroate synthase gene of Staphylococcus haemolyticus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;134:165–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirschner P, Bottger E C. Detection of mycobacterial resistance to streptomycin and clarithromycin. In: Persing D H, editor. PCR protocols for emerging infectious diseases. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulkarni V M, Seydel J K. Inhibitory activity and mode of action of diaminodiphenylsulphone in cell-free folate synthesizing systems prepared from Mycobacterium lufu and Mycobacterium leprae. Chemotherapy. 1983;29:58–67. doi: 10.1159/000238174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lacks S A, Greenberg B, Lopez P. A cluster of four genes encoding enzymes for five steps in the folate biosynthetic pathway of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:66–74. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.66-74.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy L. Activity of derivatives and analogs of dapsone against Mycobacterium leprae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978;14:791–793. doi: 10.1128/aac.14.5.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez P, Espinosa M, Greenberg B, Sacks S A. Sulfonamide resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae: DNA sequence of the gene encoding dihydropteroate synthase and characterization of the enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4320–4326. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.9.4320-4326.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manganelli R, Dubnau E, Tyagi S, Kramer F, Smith I. Differential expression of 10 sigma factor genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:715–724. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearson J M, Haile G S, Barnetson R S, Rees R J. Dapsone-resistant leprosy in Ethiopia. Lepr Rev. 1979;50:183–199. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19790024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seydel J K, Richter M, Wempe E. Mechanism of action of the folate blocker diaminodiphenylsulfone (dapsone, DDS) studied in E. coli cell-free extracts in comparison to sulfonamides (SA) Int J Lepr. 1980;48:18–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shepard C C. A kinetic method for the study of activity of drugs against Mycobacterium leprae in mice. Int J Lepr. 1967;35:429–435. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slock J, Stahly D P, Han C-Y, Six E W, Crawford I P. An apparent Bacillus subtilis folic acid biosynthesis operon containing pab, an amphibolic trpG gene, a third gene required for synthesis of para-aminobenzoic acid, and the dihydropteroate synthase gene. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:7211–7226. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.7211-7226.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swedberg G, Ringertz S, Skold O. Sulfonamide resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes is associated with differences in the amino acid sequence of its chromosomal dihydropteroate synthase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1062–1067. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.5.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Volpe F, Dyer M, Scaife J G, Darby G, Stammers D K, Delves C J. The multifunctional folic acid synthesis fas gene of Pneumocystis carinii appears to encode dihydropteroate synthase and hydroxymethyldihydropterin pyrophosphokinase. Gene. 1992;112:213–218. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams D L, Gillis T P, Fiallo P, Job C K, Gelber R H, Hill C, Izumi S. Detection of Mycobacterium leprae and the potential for monitoring of antileprosy drug therapy directly from skin biopsies by PCR. Mol Cell Probes. 1992;6:401–410. doi: 10.1016/0890-8508(92)90034-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams D L, Waguespack C, Eisenach K, Crawford J T, Portaels F, Salfinger M, Nolan C M, Abe C, Sticht-Groh V, Gillis T P. Characterization of rifampin resistance in pathogenic mycobacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2380–2386. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.10.2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams D L, Limbers C, Spring L, Jayachandra S, Gillis T P. PCR-heteroduplex detection of rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In: Persing D H, editor. PCR protocols for emerging infectious diseases. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1997. pp. 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams D L, Spring L, Collins L, Miller L P, Heifets L B, Gangadharam P R, Gillis T P. Contribution of rpoB mutations to development of rifamycin cross-resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1853–1857. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams D L, et al. The dihydropteroate synthase of Mycobacterium leprae and dapsone resistance. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1999;67:493–495. . (Abstract.) [Google Scholar]