Abstract

Objective

To estimate the prevalence of good quality child care in the first week of life in primary care services in Brazil and identify associated factors related to maternal, primary healthcare (PHC) facility and municipality characteristics.

Setting

Brazilian PHC.

Participants

6715 users of PHC facilities aged over 18 years with children under 2 years of age.

Primary outcome

The good quality child care was defined when the following health interventions were performed during postnatal check-up in the first week of life: the child was weighed and measured; the healthcare professional observed breastfeeding techniques and offered counselling on the safest sleeping position; the umbilical cord was examined and the heel prick test was performed.

Results

The prevalence of good quality care was 52.6% (95% CI 51.4% to 53.8%). Observation of breastfeeding techniques (75.9%) and counselling on the safest sleeping position (72.3%) were the activities least performed. Babies born to mothers who received a home visit from a community health worker and made a postpartum visit were twice as likely to receive good quality care (OR 1.96; 95% CI 1.70 to 2.24 and OR 1.97; 95% CI 1.74 to 2.24, respectively).

Conclusions

The information reported by the mothers related to Family Health team work processes was associated with good quality care in the first week of life. Supporting strategies that strengthen health team active search and timely screening actions could promote adequate early childhood development.

Keywords: quality in health care, primary care, community child health, epidemiology, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The results may have been affected by recall bias. However, no significant differences were found after adjusting for infant age.

The instrument of Primary Care Access and Quality-AB related to care in the first week of life did not include another specifics questions.

The use of a large nationwide sample including 73% of the country’s family health teams in 2014.

The use of multilevel analysis, through which it was possible to investigate a combination of maternal, primary healthcare facility and municipality characteristics.

Introduction

The third Sustainable Development Goal adopted by the 193 Member States of the United Nations in 2015 aims to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all, with emphasis on Target 3.8, which aims to achieve universal health coverage, including access to quality essential services.1 In health, quality assurance means compliance with the appropriate standards of the services provided to all people, at the required levels of care and when needed.2 Other authors have suggested that quality is the completeness of the specific actions set out in official documents for each health condition.3 Quality assessment entails monitoring the conditions of health services to improve outcomes and effectiveness.2 Ensuring the highest quality of care is essential for guaranteeing the right to health with equity and dignity for all.4 According to Donabedian, quality of healthcare can be assessed considering three components: (1) structure (material and human resources); (2) process (healthcare practitioner activities) and (3) outcomes (the effect of individual healthcare actions and procedures).5 However, due to the lack of a universally accepted instrument for assessing all three components, a literature review published in 2012 suggested that a combination of several models can help define quality of care, highlighting that this approach is especially important for assessing the quality of maternal and newborn healthcare.6

WHO recommendations on newborn health include ensuring the assessment of the newborn in the first hour of life and the provision of counselling and support for mothers on exclusive breastfeeding and umbilical cord care.7 Other recommendations include screening for metabolic and endocrine conditions and congenital problems and counselling for safe sleeping.8

Brazil is a country with continental geographic dimensions and a history of inequalities in socioeconomic indicators, with the North and Northeast regions that always presented the greatest disadvantages,9 and despite great advances, it continues with a Gini Index of 51.3 and a total health expenditure of 8.3%.10

In Brazil, the Ministry of Health has developed newborn monitoring and assessment programmes and policies, notably the ‘Primeira Semana de Saúde Integral’ (First Week of Comprehensive Health or PSSI in Portuguese).11 12 In Brazil’s public healthcare system, the Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS) (Unified Health System or SUS in Portuguese), newborn care is provided in primary healthcare (PHC) facilities under the Family Health Strategy (FHS).13 Family health teams use the Caderno de Atenção Básica no 33 (Primary Care Practice Guidelines no. 33) which provide guidance on care for child growth and development.14 In 2011, the government created the Programa Nacional de Melhoria do Acesso e da Qualidade da Atenção Básica (National Programme for Improving Primary Care Access and Quality or PMAQ-AB in Portuguese), which aims to improve the quality of healthcare through the transfer of financial resources to participating municipalities.15 16

The literature tends to document isolated indicators of quality of child healthcare, such as measurement of weight and length,17–19 the heel prick test,20 21 examination of the umbilical cord22–24 and counselling on correct breastfeeding positions25–27 and safe sleeping positions.28 29 However, studies assessing the quality of healthcare using multiple indicators are scarce, especially in the literature focusing on the first week of life.

The aim of this study was to estimate the prevalence of good quality child care in the first week of life under the PMAQ-AB and identify associated factors related to maternal, PHC facility and municipality characteristics.

Methods

Study design and data

The PMAQ-AB consisted of three cycles conducted in 2012, 2014 and 2018 in Brazil, each organised in four phases: (1) adherence and contractualisation; (2) development; (3) external assessment and (4) recontractualisation.16 This cross-sectional study used data from the external assessment of the second cycle (2014), conducted by a group of higher education institutions (Fundação Osvaldo Cruz (Fiocruz), Universidade Federal da Bahia, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte and Universidade Federal de Sergipe.

We used data from the following components of the evaluation instrument applied in the external assessment: module I (observation of the structure of the PHC facility) and module III (interviews with PHC facility users). The evaluation instrument and logistics of the external assessment were developed by an interinstitutional working group and standardised across the country under the coordination of the Ministry of Health’s Department of Primary Care.16

The interviews were conducted by previously trained interviewers using a tablet-based questionnaire. At the end of each interview, the data were sent by internet to a central server at the Ministry of Health. Data quality control procedures included supervision of data collection, checking for response consistency and completeness of questionnaires, and documentation of interview duration. Further information of the logistics of data collection and the dataset are available at http://apssaudegovbr/ape/pmaq.30

Study population

In the second cycle of PMAQ, 73% of the all-national PHC teams were part of the voluntary adhesion phase, and a total of 114 615 PHC users were interviewed in the external assessment phase, who were waiting for an appointment who had used the facility on a regular basis over the 12 months prior to the day of the interview. Of the total PHC users, 82 935 (72%) were women aged 18 years and over who had been pregnant at least once, including 12 787 (15.4%) mothers with children under 2 years of age. Our sample consisted of 7180 mothers (56.2%) from this group who had scheduled a postnatal check-up for their baby in the first week of life. In cases where the mother had two children under 2 years of age, only the youngest child was included.

Outcome

The outcome ‘good quality care in the first week of life’ was determined based on the score of the following six questions on health interventions received during the postnatal check-up: (1) ‘Was your child weighed?’; (2) ‘Was your child measured?’; (3) ‘Did the healthcare professional observe breastfeeding technique?’; (4) ‘Was the umbilical cord examined?’; (5) ‘Did the healthcare professional offer counselling on the safest sleeping position?’; and (6) ‘Was the heel prick test performed on your child?’. Negative and affirmative answers were scored as 0 and 1, respectively. The outcome was dichotomised, with affirmative answers to all six questions indicating good quality care in the first week of life.

Independent variables

The following variables were examined:

Maternal characteristics

Age (under 20, 20–29, 30–39 and 40 years and over); skin colour (white, black, brown/mixed-race, yellow/indigenous); level of education (incomplete primary education, incomplete secondary education and higher education); Bolsa Família Programme beneficiary (yes, no); received a home visit from a community health worker (CHW) in the first week after birth (yes, no); made a postpartum visit (yes, no). All the above characteristics were self-reported by the respondents.

PHC facility characteristics

Essential equipment and facilities for postnatal care (PHC facilities with the all of the following equipment and facilities were considered adequate: baby scale, infant measuring mat, child health booklets and neonatal care room); and minimum team (teams with at least one doctor, one nurse, one nurse technician and four CHWs were considered adequate).

Municipality characteristics

Estimated population size in number of inhabitants in 2014 (up to 10 000; 10 001–30 000; 30 001–100 000; 100 001–300 000; more than 300 000); Human Development Index (HDI) (<0.555, 0.555–0.699, 0.700–0.799, 0.800–1.000); and FHS population coverage in 2014 (up to 50%, 50.1%–75.0%, 75.1%–99.9%, 100%).31

Statistical analysis

Descriptive and bivariate analysis

The maternal, PHC facility and municipality characteristics were described using frequencies and their 95% CIs.

Multilevel bivariate analysis was performed to test the association between good quality care and the independent variables, considering maternal characteristics as the first level, PHC facility characteristics as the second level, and municipality characteristics as the third level. Multilevel logistic regression was performed to obtain crude ORs and 95% CI, and significance was tested using the Wald test.

Multivariate analysis

Multivariate multilevel logistic regression was performed to assess the adjusted effect of the independent variables on the outcome including variables that obtained a p value of less than or equal to 0.20 in the Wald test. Three models were adjusted: model 1, adjusted for maternal characteristics (level 1); model 2, adjusted for PHC facility characteristics (level 2) and model 3, including essential equipment and facilities (level 2), maternal age, beneficiary of the Bolsa Família Programme, received a home visit from a CHW in the first week after birth, and made a postpartum visit (level 1). The goodness of fit of each model was assessed using the Akaike information criterion (AIC)32 and Bayesian information criterion (BIC).33 The model with the lowest AIC and BIC values is deemed to be the best at explaining the variance of the outcome based on the independent variables. The analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15., StataCorp), adopting a significance level of 0.05.

Patient and public involvement statement

The PHC users were not involved in the design, or planning of this secondary data analysis. However, it is crucial for the initial data collection process for information on perception of the PHC users about access and utilisation of the PHC facilities. The findings of this study will not be directly disseminated to study participants.

Results

Complete information was available for 6715 of the 7180 women whose babies had a postnatal check-up in the first week of life. These women visited 5717 PHC facilities located in 2485 municipalities across the country.

The service users were predominantly aged 20 to 29 years (54.7%), brown/mixed skin colour (49.8%), had completed higher education (41.2%), were not beneficiaries of the Bolsa Família Programme (55.0%), had received a home visit from a CHW in the first week after birth (72.6%), and made a postpartum visit (67.0%). Almost 60.0% of the PHC facilities had all the essential equipment and facilities for postnatal care and 74.6% had at least one minimum team. With regard to municipality characteristics, 40.0% had between 10 001 and 30 000 inhabitants, 60.4% had a HDI of between 0.555 and 0.699, and 58.9% had 100% FHS coverage (table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of maternal, PHC facility and municipality characteristics. PMAQ-AB, Cycle II, 2014

| Variable | n | % | 95% CI |

| Maternal characteristics | |||

| Age (years) (6715) | |||

| Under 20 | 797 | 11.9 | 10.9 to 12.5 |

| 20–29 | 3672 | 54.7 | 53.6 to 55.9 |

| 30–39 | 2002 | 29.8 | 28.0 to 31.0 |

| 40 and over | 244 | 3.6 | 3.2 to 4.1 |

| Self-reported skin colour (6633) | |||

| White | 2154 | 32.5 | 31.2 to 33.5 |

| Black | 890 | 13.4 | 12.7 to 14.4 |

| Brown/mixed | 3305 | 49.8 | 48.7 to 51.1 |

| Yellow/indigenous | 284 | 4.3 | 3.8 to 4.7 |

| Level of education (6712) | |||

| Incomplete primary education | 1863 | 27.8 | 26.4 to 28.5 |

| Incomplete secondary education | 2086 | 31.0 | 29.9 to 32.1 |

| Higher education | 2763 | 41.2 | 40.4 to 42.8 |

| Bolsa Família Programme beneficiary (6703) | |||

| No | 3686 | 55.0 | 53.7 to 56.1 |

| Yes | 3017 | 45.0 | 43.9 to 46.3 |

| Home visit from community health worker (6628) | |||

| No | 1815 | 27.4 | 26.3 to 28.5 |

| Yes | 4813 | 72.6 | 71.5 to 73.7 |

| Postpartum visit (6588) | |||

| No | 2173 | 33.0 | 31.7 to 33.1 |

| Yes | 4415 | 67.0 | 66.0 to 68.3 |

| PHC facility characteristics | |||

| Essential equipment and facilities (5717) | |||

| No | 2375 | 41.5 | 40.3 to 42.8 |

| Yes | 3342 | 58.5 | 57.2 to 59.7 |

| Minimum team (5717) | |||

| No | 1452 | 25.4 | 24.3 to 26.5 |

| Yes | 4265 | 74.6 | 73.5 to 75.7 |

| Municipality characteristics | |||

| Population size (2485) | |||

| Up to 10 000 | 702 | 28.3 | 26.5 to 30.1 |

| 10 001–30 000 | 996 | 40.0 | 38.2 to 42.0 |

| 30 001–1 00 000 | 532 | 21.4 | 19.8 to 23.1 |

| 100 001–3 00 000 | 174 | 7.0 | 6.1 to 8.1 |

| More than 300 000 | 81 | 3.3 | 2.6 to 4.0 |

| Human Development Index (2485) | |||

| <0.555 | 158 | 6.4 | 5.5 to 7.4 |

| 0.555–0.699 | 1502 | 60.4 | 58.5 to 62.4 |

| 0.700–0.799 | 790 | 31.8 | 30.0 to 33.7 |

| 0.800–1.000 | 35 | 1.4 | 1.0 to 1.9 |

| Family health strategy coverage (%) (2485) | |||

| Up to 50 | 239 | 9.6 | 8.5 to 10.8 |

| 50.1–75.0 | 320 | 12.9 | 11.6 to 14.3 |

| 75.1–99.9 | 461 | 18.6 | 17.1 to 20.1 |

| 100 | 1465 | 58.9 | 57.0 to 60.9 |

PMAQ-AB, cycle II, 2014.

PHC, primary healthcare; PMAQ-AB, Primary Care Access and Quality-AB.

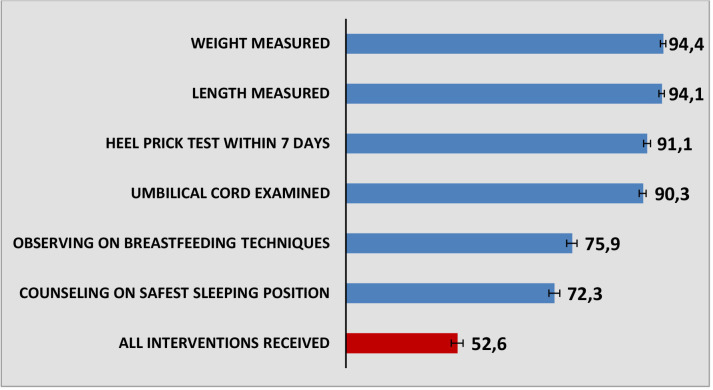

Figure 1 shows the proportion of mothers who reported having received each of the health interventions in the first week of life. The most frequently performed interventions were measurement of weight and length (94.4% and 94.1%, respectively). The least frequently performed interventions were the healthcare professional observed breastfeeding techniques and counselling on the safest sleeping position (75.9% and 72.3%, respectively). The prevalence of good quality care during the postnatal check-up in the first week of life was 52.6% (95% CI 51.4% to 53.8%).

Figure 1.

Proportion of mothers who reported receiving newborn health interventions in the first week of life. PMAQ, Cycle II, 2014. PMAQ, Primary Care Access and Quality.

Babies born to mothers aged 40 years and over were 46% more likely (95% CI 1.06% to 2.02%) to receive good quality care than those born to women under 20 years of age. Bolsa Família Programme beneficiaries were 15% more likely (95% CI 1.03% to 1.28%) to receive good quality care than non-beneficiaries. Babies born to mothers who received a home visit from a CHW in the first week after birth and made a postpartum visit were twice as likely to receive good quality care than those born to mothers who did not (OR 2.15; 95% CI 1.88 to 2.46 and OR 2.12; 95% CI 1.87 to 2.40, respectively). Babies whose mothers used PHC facilities with all the essential postnatal care equipment and facilities were 10% more likely to receive good quality care than those born to mothers who used PHC facilities without essential equipment and facilities (95% CI 0.98 to 1.24; p=0.093). No significant association was found between the outcome and population size, HDI, FHS coverage, minimum team, skin colour and level of education. The latter variables were not included in the adjusted analysis because the p value was greater than 0.20 (table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate multilevel analysis of good quality newborn care in the first week of life. PMAQ-AB, Cycle II, 2014

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P value* |

| Maternal characteristics (level 1) | |||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||

| Under 20 | 1.00 | ||

| 20–29 | 1.19 | 1.00 to 1.41 | |

| 30–39 | 1.43 | 1.18 to 1.72 | |

| 40 and over | 1.46 | 1.06 to 2.02 | |

| Self-reported skin colour | 0.760 | ||

| White | 1.00 | ||

| Black | 0.92 | 0.77 to 1.09 | |

| Brown/mixed | 1.00 | 0.88 to 1.13 | |

| Yellow/indigenous | 0.94 | 0.71 to 1.24 | |

| Level of education | 0.618 | ||

| Incomplete primary education | 1.00 | ||

| Incomplete secondary education | 0.95 | 0.83 to 1.09 | |

| Higher education | 1.01 | 0.89 to 1.16 | |

| Bolsa Família Programme beneficiary | 0.015 | ||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.15 | 1.03 to 1.28 | |

| Home visit from community health worker | <0.001 | ||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 2.15 | 1.88 to 2.46 | |

| Postpartum visit | <0.001 | ||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 2.12 | 1.87 to 2.40 | |

| PHC facility characteristics (level 2) | |||

| Essential equipment and facilities | 0.093 | ||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.10 | 0.98 to 1.24 | |

| Minimum team | 0.960 | ||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.00 | 0.88 to 1.15 | |

| Municipality characteristics (level 3) | |||

| Population size | 0.664 | ||

| Up to 10 000 | 1.00 | ||

| 10 001–30 000 | 0.98 | 0.81 to 1.17 | |

| 30 001–1 00 000 | 0.92 | 0.76 to 1.12 | |

| 1 00 001–300 000 | 0.88 | 0.70 to 1.10 | |

| More than 300 000 | 0.87 | 0.69 to 1.11 | |

| Human Development Index | 0.900 | ||

| <0.555 | 1.00 | ||

| 0.555–0.699 | 1.10 | 0.82 to 1.47 | |

| 0.700–0.799 | 1.09 | 0.81 to 1.48 | |

| 0.800–1.000 | 1.17 | 0.77 to 1.77 | |

| Family health strategy coverage (%) | 0.517 | ||

| Up to 50 | 1.00 | ||

| 50.1–75,0 | 1.06 | 1.05 to 1.72 | |

| 75.1–99.9 | 1.04 | 1.07 to 1.71 | |

| 100 | 1.13 | 1.14 to 1.73 | |

PMAQ-AB, Cycle II, 2014.

*P value using the Wald test.

PHC, primary healthcare; PMAQ-AB, Primary Care Access and Quality-AB.

In the multilevel analysis adjusted for maternal characteristics (model 1), babies born to mothers who received a home visit from a CHW in the first week after birth and who made a postpartum visit were 96% and 97% more likely, respectively, to receive good quality care than those born to mothers who did not (OR 1.96; 95% CI 1.70 to 2.24 and OR 1.97 95% CI 1.74 to 2.24, respectively). The association between mother’s age and being a Bolsa Família Programme beneficiary and the outcome was not significant in this model (table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted multilevel analysis of good quality newborn care in the first week of life by maternal and PHC facility characteristics. PMAQ-AB, Cycle II, 2014

| Variable | Model 1* | Model 2† | Model 3‡ | ||||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Maternal characteristics (level 1) | |||||||||

| Age (years) | 0.076 | 0.079 | |||||||

| Under 20 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 20–29 | 1.11 | 0.93 to 1.33 | 1.11 | 0.93 to 1.33 | |||||

| 30–39 | 1.25 | 1.03 to 1.52 | 1.25 | 1.03 to 1.51 | |||||

| 40 and over | 1.32 | 0.95 to 1.85 | 1.32 | 0.95 to 1.85 | |||||

| Bolsa Família Programme beneficiary | 0.097 | 0.098 | |||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Yes | 1.10 | 0.98 to 1.23 | 1.10 | 0.98 to 1.23 | |||||

| Visit from community health worker | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Yes | 1.96 | 1.70 to 2.24 | 1.96 | 1.71 to 2.24 | |||||

| Postpartum visit | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Yes | 1.97 | 1.74 to 2.24 | 1.97 | 1.73 to 2.23 | |||||

| PHC facility characteristics (level 2) | |||||||||

| Essential equipment and facilities | 0.093 | 0.240 | |||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Yes | 1.10 | 0.98 to 1.24 | 1.07 | 0.95 to 1.21 | |||||

| Goodness of fit | |||||||||

| AIC | 8701.35 | 9264.19 | 8701.96 | ||||||

| BIC | 8762.37 | 9291.44 | 8769.76 | ||||||

Adjusted analysis run with variables with p<0.20 in the bivariate analysis.

PMAQ-AB, Cycle II, 2014.

*Adjusted for level 1 variables (Maternal characteristics: maternal age, Bolsa Familia Programme beneficiary, home visit from a CHW, postpartum visit).

†Adjusted for level 2 variable (PHC facility characteristics: essential equipment and facilities).

‡Adjusted for level 1 and 2 variables (maternal age, Bolsa Familia Programme beneficiary, home visit from a CHW, postpartum visit, essential equipment and facilities).

AIC, Akaike Information Criterion; BIC, Bayesian Information Criterion; CHW, community health worker; PHC, primary healthcare; PMAQ-AB, Primary Care Access and Quality-AB.

In model 3, babies born to mothers who received a home visit from a CHW in the first week after birth and made a postpartum visit were almost twice as likely to receive good quality care than those born to mothers who did not (OR 1.96; 95% CI 1.71 to 2.24 and OR 1.97; 95% CI 1.73 to 2,23, respectively) (table 3).

The AIC and BIC values revealed that the model that showed the best fit was model 1 (table 3).

Discussion

Our findings show that a little over half of the infants received good quality care during the postnatal check-up in the first week of life. The interventions with the lowest prevalence were the healthcare professional observed breastfeeding techniques and counselling on the safest sleeping positions. Our study identified that having received a home visit from a CHW in the first week after birth and having made a postpartum visit were associated with good quality care.

A study conducted in Mato Grosso State in Brazil using the Donabedian model showed that only 38.6% of mothers of infants under the age of 1 reported receiving good quality care for their babies.34 In 2006, a study that evaluated the performance of the FHS found that 76.2% of mothers from the South Region and 82.3% from the Northeast Region reported that child care provided in PHC facilities was good/very good.35 A study in the State of Alagoas that assessed the quality of child care using an instrument developed by the Ministry of Health to evaluate the FHS showed that 47.7% of the FHS teams were classified in the ‘advanced quality’ category.36 The lack of compliance with guidelines, protocols, and standards appears to be a systematic problem among health professionals,37 undermining the quality and comprehensiveness of care.

In this study, three-quarters of the mothers were observed by the healthcare professional on breastfeeding techniques during the postnatal check-up. Clear guidance on recommended breastfeeding techniques such as correct attachment and positioning improve the chances of breastfeeding success.14 37 38 A study evaluating the knowledge and activities of health professionals in primary care centres in Lithuania revealed that only 62% of mothers had received counselling on breastfeeding techniques.25 In Brazil, a study carried out in 2003 found that only 50% of PHC facilities in the State of Rio de Janeiro provided counselling on position and attachment,27 while a survey conducted in 2018 in the city of Rio de Janeiro reported that only 63% of mothers of infants under 6 months had received counselling on breastfeeding techniques.26 One of the obstacles to the provision of counselling on breastfeeding techniques is lack of training of healthcare professionals. In this regard, studies have shown that less than 50% of doctors in hospitals and 20% of health professionals in primary care services had received training in breastfeeding techniques.26 27 39

According to the WHO and Brazil’s Ministry of Health, in the first postnatal check-up mothers should receive counselling on sleeping their baby in the supine position.14 Our findings show that a little over 70% of mothers received this counselling. A study conducted in the State of Rio Grande do Sul in 2006 showing that only 4% of mothers reported putting their babies to sleep in the supine position and a mere 0.1% received guidance on safe sleeping positions from paediatricians.29 Another study in the same state revealed that 20% of mothers knew the safest sleeping position, with only 29% reporting having received this information from their doctor.40 A study published in 2019 showed that babies whose mothers had received counselling on safe sleeping positions from a doctor or other health professional were 43% and 49% more likely, respectively, to sleep in the supine position than those whose mothers had not received counselling.28

A number of studies have shown that the older the mother the better child health indicators and quality of prenatal and child care.17 28 41–43 Our findings also show a positive association between maternal age and quality of care in the first week of life. However, this association was not significant in the model adjusted for PHC facility and maternal characteristics. Our findings show that babies born to mothers who were beneficiaries of the Bolsa Família Programme were more likely to receive good quality care. Created in 2003 and targeting families living in poverty and extreme poverty, the Bolsa Família Programme is one of the world’s largest cash transfer programmes in which the family enrolled has to comply with specific education and health-related conditions, especially children younger than 7 years and pregnant and lactating women.17 44 45 An ecological study of the effect of the Programme on childhood mortality found that children under 5 years of age living in municipalities with high Bolsa Família Programme coverage (>32%) were 32% and 46% less likely, respectively, to have diarrhoeal diseases and malnutrition than those living in municipalities with low coverage (<17%).44 In addition, a study found that the prevalence of high quality healthcare among infants at 2 months was higher among those from families receiving benefit under the Programme.17 A study reported that infants from families receiving benefit under the Bolsa Família Programme were more likely to use postnatal care services, including growth monitoring and vaccination.45 The association between being a beneficiary of the Bolsa Família Programme and good quality care was not significant in the adjusted analyses.

Babies whose mothers received a home visit from a CHW in the first week after birth were twice as likely to receive good quality care. CHW Programmes play an important role in improving maternal and child healthcare and access to and quality of family planning services and in preventing and controlling infections.46 Brazil’s CHW Program, introduced in 1980,47 emerged as a strategy designed to improve access to and quality of PHC, through activities of monitoring, promotion, and guiding the families. Svitone et al found that the work of CHWs contributed to a drop in infant mortality due to diarrhoea in the State of Ceará, from 48% in 1987 to 23% in 1994,48 while Silva et al reported that home visits from CHWs and nurses during the first week of life led to a 48% increase in the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months of age.43 Despite the evidence showing the importance of the work of CHWs in PHC services, weaknesses have been identified in relation to first newborn home visits. Problems include the fact that visits are often made outside the recommended times due to difficulties in locating mothers who stay at someone else’s home after delivery and the lack of maternal monitoring close to delivery by CHWs and other members of the Family Health team.49 Effective interventions in FHS work processes, such as universal internet access and information and communication technology across services, could help facilitate permanent contact between service users and health workers, overcoming barriers to access and enabling telemonitoring of the populations. Ensuring universal access to comprehensive healthcare in the first week of life depends on guaranteeing and expanding the presence of CHWs in Family Health teams, which are threatened by the 2017 PHC Policy.3 13 In line with WHO recommendations,50 in 2018, Facchini et al developed a number of proposals to address the challenges to improving the quality of primary care, with emphasis on the professional development and continuing education of health professionals.3 Was underlined the importance of including counselling on child health-related issues and ensuring standardised transmission of information to mothers, not only in the postnatal check-up in the first week of life, but also throughout the monitoring of growth and development.

Women who made a postpartum visit were almost twice as likely to receive good quality care during the postnatal check-up in the first week of life. This may be related to closer bonds between the health team and these users, strengthening the adherence of mothers to essential postnatal care. The postpartum period is an opportune moment for health professionals to ensure early detection and develop health promotion and preventive care interventions for both mother and child.51–53

This study has some limitations. First, the results may have been affected by recall bias, as it is possible that some mothers were unable to remember all of the recommendations given by health professionals during the postnatal check-up in the first week of life, particularly those with older babies. In this regard, it may be easier to remember interventions such as measurements and examinations than verbal guidance. However, no significant differences were found in the prevalence of good quality care after adjusting for infant age, suggesting that recall bias was minimised. Another limitation is that the set of questions used to determine quality of care was limited. In this regard, the part of the instrument used to conduct the external assessment of the PMAQ-AB related to care in the first week of life did not include questions about vaccines and guidance on vaccination, exclusive breast feeding and postnatal hygiene. However, the items used to construct the indicator of good quality care used in our study are based on recommendations set out in documents and reports produced by the WHO, UNICEF and Brazil’s Ministry of Health (Caderno de Atenção Básica no 33), making them good basic indicators of the comprehensive assessment of newborns in the postnatal check-up in the first week of life.3 7 14

Study strengths include the use of a large nationwide sample including 73% of the country’s family health teams during the second cycle of the PMAQ-AB. Another strength was the use of multilevel analysis, through which it was possible to investigate a combination of maternal, PHC facility and municipality characteristics taking into account variance at each level.

Conclusion

Our findings identified the need to improve the quality of newborn care in the first week of life, considering the importance of care for early childhood development. Necessary changes largely involve health teamwork processes, such as ensuring a home visit from a CHW in the first week of life and the provision of postpartum visit. Future research should assess trends in indicators of quality of care in the first week of life across the three cycles of the PMAQ-AB. Further research is also warranted to ensure the continuity of evaluation processes aimed at improving the performance of Family Health teams and reducing health inequalities.

bmjopen-2021-049342supp001.pdf (261.1KB, pdf)

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors participated in preparing the manuscript and approving the final version for submission. MdPF-Q and ET were responsible for study conception. MdPF-Q, ET and CB were responsible for data analysis and interpretation. MdPF-Q, ET, CB, SMSD, ABZ and LF took the lead in writing the manuscript. MdPFQ is acting as guarantor.

Funding: This study received support from the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), Funding Code 001. Application number MS 25000.119660/2013-17.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. https://aps.saude.gov.br/

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Federal University of Goiás Research Ethics Committee (code No. 487055, 12/02/2013). All respondents signed an informed consent form stating that they had been fully informed as to the nature of study and confirming they understood that any information provided would remain confidential and they could withdraw freely at any stage of the study.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) . Indicator and monitoring framework for the global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health (2016-2030), 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO), National Health Systems and Policies Unit . Quality assessment and assurance in primary health care: programme statement. Geneva, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Facchini LA, Tomasi E, Dilélio AS. Qualidade da Atenção Primária Saúde no Brasil: avanços, desafios e perspectivas. Saúde Debate 2018;42:208–23. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) . 2018 progress report: reaching every newborn national 2020 milestones, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA 1988;260:1743–8. 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raven JH, Tolhurst RJ, Tang S, et al. What is quality in maternal and neonatal health care? Midwifery 2012;28:e676–83. 10.1016/j.midw.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization (WHO) . WHO recommendations on newborn health: guidelines approved by the WHO Guidelines Review Committee. Geneva, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haran C, van Driel M, Mitchell BL, et al. Clinical guidelines for postpartum women and infants in primary care–a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:1. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nunes A, Santos JRS, Barata RB. Medindo as Desigualdades em Saúde no Brasil - uma proposta de monitoramento. Brasília: Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde - OPAS/OMS; Instituto de Pesquisa Aplicada e Econômica (IPEA), 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castro MC, Massuda A, Almeida G, et al. Brazil’s unified health system: the first 30 years and prospects for the future. Lancet 2019;394:345–56. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31243-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde . Agenda de compromissos para a saúde integral dA criança E redução dA mortalidade infantil. Brasília, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde . Política Nacional de Atenção Integral À Saúde da Criança - Orientações para implementação. Brasília – DF, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde . Política Nacional de Atenção Básica. Brasília - DF: Ministério da Saúde, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde . Cadernos de Atenção Básica N° 33 Saúde dA Criança: Crescimento E Desenvolvimento. Brasília – DF, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giovanella L, In de Almeida PF, dos Santos AM, et al. Atenção Primária Saúde na coordenação do cuidado em regiões de saúde. Salvador, Brasil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção Saúde, Departamento de Atenção Básica . Programa Nacional de Melhoria do Acesso E dA Qualidade dA Atenção Básica (PMAQ): manual instrutivo. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santos ASD, Duro SMS, Cade NV, et al. Quality of infant care in primary health services in Southern and Northeastern Brazil. Rev Saude Publica 2018;52:11. 10.11606/S1518-8787.2018052000186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lima GGT, MFOC S, Costa TNA. Registros do enfermeiro no acompanhamento do crescimento E desenvolvimento: enfoque Na consulta de puericultura. Revista da Rede de Enfermagem do Nordeste 2009;10:117–24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linhares AO, Gigante DP, Bender E, et al. Avaliação DOS registros E opinião das mães sobre a caderneta de saúde dA criança em unidades básicas de saúde, Pelotas, RS. Rev AMRIGS 2012;56:245–50. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reis EFS, Partelli ANM. Teste do Pezinho: conhecimento E atitude DOS profissionais de enfermagem. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa em Saúde/Brazilian J Health Res 2014;16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.JGd O, Sandrini D, DCd C, et al. Triagem neonatal ou teste do pezinho: conhecimento, orientações E importância para a saúde do recém-nascido. Cuidarte, Enferm 2008;2:71–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linhares EF, da Silva LWS. O cuidado do coto umbilical do recém-nascido sob a ótica DOS seus cuidadores: saberes culturais. Revista Eletrônica Gestão e Saúde 2012;3:690–707. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walsh S, Norr K, Sankar G, et al. Newborn cord care practices in Haiti. Glob Public Health 2015;10:1107–17. 10.1080/17441692.2015.1012094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silva LR, Arantes LAC, Villar ASE, et al. Enfermagem no puerpério: detectando O conhecimento das puérperas para O autocuidado E cuidado com O recém-nascido. Revista de Pesquisa: Cuidado é Fundamental online 2012;4:2327–37. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leviniene G, Petrauskiene A, Tamuleviciene E, et al. The evaluation of knowledge and activities of primary health care professionals in promoting breast-feeding. Medicina 2009;45:238–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.JdS A, MICd O, RVVF R. Orientações sobre amamentação Na atenção básica de saúde E associação com O aleitamento materno exclusivo. Ciencia & Saúde Coletiva 2018;23:1077–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Oliveira MIC, Camacho LAB, Tedstone AE. A method for the evaluation of primary health care units' practice in the promotion, protection, and support of breastfeeding: results from the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Hum Lact 2003;19:365–73. 10.1177/0890334403258138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.da Silva BGC, da Silveira MF, de Oliveira PD, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of supine sleep position in 3-month-old infants: findings from the 2015 Pelotas (Brazil) birth cohort. BMC Pediatr 2019;19:165. 10.1186/s12887-019-1534-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geib LTC, Nunes ML. [Sleeping habits related to sudden infant death syndrome: a population-based study]. Cad Saude Publica 2006;22:415–23. 10.1590/s0102-311x2006000200019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Data from: Secretaria de Atenção Primária Saúde . Programa Nacional de Melhoria do Acesso E dA Qualidade dA Atenção Básica (PMAQ). Brasília, 2019. http://aps.saude.gov.br/ape/pmaq [Google Scholar]

- 31.Facchini LA. In Reich, MR, Takemi K. Governing health system: for nations and communities around the world. Massachusetts: EUA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akaike H, Parzen E, Tanabe K, et al. Selected papers of Hirotugu Akaike. New York: Springer, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Statist 1978;6:461–4. 10.1214/aos/1176344136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.PSSdA M, Gaiva MAM. Satisfação das usuárias quanto atenção prestada criança pela rede básica de saúde. Escola Anna Nery 2013;17:455–65. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Facchini LA, Piccini RX, Tomasi E, et al. Desempenho do PSF no Sul E no Nordeste do Brasil: avaliação institucional E epidemiológica dA Atenção Básica à Saúde. Ciênc. saúde coletiva 2006;11:669–81. 10.1590/S1413-81232006000300015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MLdH S, Ponnet L, Campos CEA. Quality of child health care in the family health strategy. J Human Growth Develop 2013;23:151–6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.MdFMd A, Otto AFN, BdAS S. Primeira avaliação do cumprimento DOS Dez Passos para O Sucesso do Aleitamento Materno NOS Hospitais Amigos dA Criança do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Saúde Materno Infantil 2003;3:411–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção Saúde, Departamento de Atenção Básica . Saúde dA criança: nutrição infantil: aleitamento materno E alimentação complementar. Caderno de Atenção Básica N° 23. Brasília, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopes SdaS, Laignier MR, Primo CC, et al. Baby-friendly hospital initiative: evaluation of the ten steps to successful breastfeeding. Rev Paul Pediatr 2013;31:488–93. 10.1590/S0103-05822013000400011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cesar JA, Cunha CF, Sutil AT, et al. Opinião das mães sobre a posição do bebê dormir após campanha nacional: estudo de base populacional no extremo sul do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Saúde Materno Infantil 2013;13:329–33. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomasi E, Fernandes PAA, Fischer T, et al. [Quality of prenatal services in primary healthcare in Brazil: indicators and social inequalities]. Cad Saude Publica 2017;33:e00195815. 10.1590/0102-311X00195815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viellas EF, Domingues RMSM, Dias MAB, et al. Assistência pré-natal no Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 2014;30:S85–100. 10.1590/0102-311X00126013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaal S, Caminha MFC, Silva SL. Maternal breastfeeding: indicators and factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in a subnormal urban cluster assisted by the family health strategy. J Pediatr 2019;95:298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rasella D, Aquino R, Santos CAT, et al. Effect of a conditional cash transfer programme on childhood mortality: a nationwide analysis of Brazilian municipalities. Lancet 2013;382:57–64. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60715-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shei A, Costa F, Reis MG, et al. The impact of Brazil’s Bolsa Família conditional cash transfer program on children’s health care utilization and health outcomes. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2014;14:10. 10.1186/1472-698X-14-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu A, Sullivan S, Khan M, et al. Community health workers in global health: scale and scalability. Mt Sinai J Med 2011;78:419–35. 10.1002/msj.20260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.RSd B, NEMS F, DLAd S. Atividades DOS Agentes Comunitários de Saúde no âmbito dA Estratégia Saúde dA Família: revisão integrativa dA literatura. Saúde Transform. Soc 2014;5:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Svitone CE, Garfield R, Vasconcelos MI, et al. Primary health care lessons from the Northeast of Brazil: the Agentes de Saúde program. Rer Panam Salud Publica 2000;7:293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lucena DBA, Guedes ATA, TMAV C. Primeira semana saúde integral do recém-nascido:ações de enfermeiros da Estratégia Saúde da Família. Rer Gaúcha Enferm 2018;39:e2017–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.World Health Organization (WHO) . Standards for improving the quality of care for children and young adolescents in health facilities. Geneva, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andrade RD, Santos JS, Maia MAC. Fatores relacionados saúde dA mulher no puerpério E repercussões Na saúde dA criança. Escola Anna Nery 2015;19:181–6. [Google Scholar]

- 52.dos Santos F, Brito R, Mazzo M. Puerpério E revisão pós-parto: significados atribuídos pela puérpera. REME - Rev Min Enferm 2013;17:854–8. [Google Scholar]

- 53.BHdB A, de Brito RS. Consulta puerperal: O que leva as mulheres a buscarem essa assistência? Revista da Rede de Enfermagem do Nordeste 2012;13:1163–70. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-049342supp001.pdf (261.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. https://aps.saude.gov.br/