Abstract

Background

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) continue to have the highest maternal and under-five child deaths in the world. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is amplifying the problems and overwhelming already fragile health systems. Community health workers (CHWs) are increasingly being acknowledged as crucial members of the healthcare workforce in improving maternal and child health (MCH). However, evidence is limited on multilevel determinants of an effective CHWs programme using CHWs’ perspective. The objective of this systematic review is to examine perceived barriers to and enablers of different levels of the determinants of the CHWs’ engagement to enhance MCH equity and a resilient community health system in SSA.

Methods

We systematically conducted a literature search from inception in MEDLINE complete, EMBASE, CINAHL complete and Global Health for relevant studies. Qualitative studies that presented information on perceived barriers to and facilitators of effectiveness of CHWs in SSA were eligible for inclusion. Quality appraisal was conducted according to the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative study checklist. We used a framework analysis to identify key findings.

Findings

From the database search, 1561 articles were identified. Nine articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final review. Using socio-ecological framework, we identified the determinants of CHWs’ effectiveness at 4 levels: individual/CHWs, interpersonal, community and health system logistics. Under each level, we identified themes of perceived barriers such as competency gaps, lack of collaboration, fragmentation of empowerment programmes. In terms of facilitators, we identified themes such as CHW empowerment, interpersonal effectiveness, community trust, integration of CHWs into health systems and technology.

Conclusion

Evidence from this review revealed that effectiveness of CHW/MCH programme is determined by multilevel contextual factors. The socio-ecological framework can provide a lens of understanding diverse context that impedes or enhances CHWs’ engagement and effectiveness at different levels. Hence, there is a need for health programme policy makers and practitioners to adopt a multilevel CHW/MCH programme guided by the socio-ecological framework to transform CHW programmes. The framework can help to address the barriers and scale up the facilitators to ensuring MCH equity and a resilient community health system in SSA.

Keywords: health services research, health policy, maternal health, public health

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries continue to have the highest maternal and under-five child deaths in the world.

Community health workers (CHWs) are acknowledged as crucial members of the healthcare workforce but are faced with multiple challenges in executing their responsibilities.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Multilevel barriers to CHWs’ effectiveness in SSA include fragmentation of empowerment of CHWs programmes, cultural beliefs and practices and gender prejudice.

Multilevel facilitators of CHWs’ effectiveness in SSA include mobile technology access and use, integration of CHWs into health systems and community trust in CHWs.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE AND/OR POLICY

-

The effort to transform CHWs’ effectiveness to ensure maternal and child health (MCH) equity and a resilient health system in SSA would require:

Adopting a multilevel framework-based CHW/MCH programme to ensure context-based CHWs programme to address the multilevel barriers and scaling up the enabling factors.

Enhancing CHW/MCH programmes by scaling up the enabling factors, which include sustainable CHWs empowerment, and integration of CHWs into health systems and digital technology.

Background

Although there has been increased attention to community health workers (CHWs)-led programmes over the past four decades, challenges remain in ensuring maternal and child health (MCH) equity and a resilient community health systems in low-income counties including countries in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).1–3 Despite the progress made, the SSA countries continue to have the highest child and maternal mortality occurrences in the world and there are substantial inequities in MCH services access and health outcomes within and between countries.3 In the region, health system equity and resilience are undermined when preventable and avoidable systematic conditions constrain life choices and health needs are not adequately addressed.2–4 Health equity exists when all people are able to reach their full health potential and receive high-quality care that is fair and appropriate from each person’s perspective, no matter where they live, who they are or what they have.5–7 Conversely, health inequities exist when there are preventable differences in health,3 4 6 7 which include inequities in MCH outcomes. We argue that absence of resilient community health system has magnified existing substantial inequities in MCH. There are several indices that shows the fragility of the health system in SSA.2 7 8 Some of these include chronic shortage of health workers, lack of investment in medical and diagnostic supplies, inadequate health information system, poor health infrastructure and insufficient health finance.2–4 7 8 Hence, it is crucial to ensure equitable and a resilient community health system for optimal, equities and sustainable MCH outcomes in SSA. Health system resilience has been defined as the ability of health actors, institutions and populations to demonstrate absorptive, adaptive, accessible and transformative capacities to prepare for and effectively respond to health system shocks and disturbances.2 9

SSA countries continue to have the highest maternal and under-five child deaths in the world.3 10 The coverage and utilisation of MCH-related services are lower compared with other regions of the world.3 The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is amplifying the problems and overwhelming already fragile health systems.2 A modelling study on the indirect effects of the pandemic in 118 low-income and middle-income countries estimated a reduction in maternal health service by at least 18%–52%.11 In SSA, a larger proportion of women give birth without any skilled attendants.3 12 In addition, about 80% of morbidity and death in children under the age of 5 occur before reaching the health facility and healthcare providers.11 This makes SSA the riskiest region for maternal and under-five child death occurrences in the world. Understandably, this has become a key health challenge in the region and persists as a global public health agenda, to meet the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) #3. SDG #3 aim to reduce maternal mortality to <70 per 100 000 live births.13–15

Since the Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978,1 which aimed at achieving universal health coverage by expanding primary healthcare systems, there have been multiple efforts towards building community health. These efforts have led to significant national and international action which has substantially contributed to the improvement of health outcomes including MCH, particularly in underserved areas such as SSA.1 One of the crucial cornerstones of primary healthcare provision since the Alma-Ata Declaration have been CHWs. CHWs are defined by different organisations including WHO. For this study, we used the definition of CHWs provided by the American Public Health Association.

The American Public Health Association definition states that:

“A community health worker is a frontline public health worker who is a trusted member of and/or has an unusually close understanding of the community served. This trusting relationship enables the worker to serve as a liaison/link/intermediary between health/social services and the community to facilitate access to services and improve the quality and cultural competence of service delivery”.16

The WHO noted CHWs as a key resource to providing basic health services for underserved areas because they help to fill the shortage of primary health service provider at the community level.

The significance of CHWs providing basic, essential and equitable MCH services has been evident in many countries.1 17 18 However, the literature shows that CHWs are experiencing multiple challenges in executing their responsibilities. Some barriers to CHWs’ effectiveness are not a product of the health system, but rather arise from the context in which the CHWs work. One context that crucially impacts CHWs’ performance and acceptance is the sociocultural context.19

There is an increasing body of quantitative literature on the effectiveness of CHWs programme intervention. The studies typically focus on a single level of analysis (providers or beneficiaries’ level) to measure the outputs and outcome within the context of the WHO health systems building blocks.20–23 We argue that these outputs and outcome-oriented studies do not indicate how the complex contextual, socio-ecological factors affect the engagement of CHWs in SSA.24 25 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention categorises such multilevel determinants into different socio-ecological levels.26 The levels are: (i) health workers’ individual-level knowledge, skills and attitudes; (ii) interpersonal factors, such as health personnel collaboration and supportive approach; (iii) community-level factors, such as community acceptability/recognition, trust and community tradition, value and beliefs; (iv) health system and logistics-related factors, such as health policy, programme, human resource/training, financial and material supply chain and logistic approaches. However, in the context of CHWs programme, there is limited evidence on a multilevel determinant of CHWs’ effectiveness based on the lived experience of CHWs’ perspective. The multilevel determinants include from individual (CHWs competency), to interpersonal, to community and to health system level determinants of effective CHWs programme.1 26–28

Effective and sustainable CHWs interventions require multilevel context understanding and response based on the lived experience of CHWs. Despite CHWs being the lowest unit (village level) of the public health structure of SSA, there is limited evidence of an analysis framework at the microlevel to capture the multilevel determinants of CHWs’ engagement. This is a problem as there is a lack of a context-specific health system framework that pinpoints the specific barriers to and facilitators of CHWs programme.7 18 21 In 2007, WHO introduced health systems building block framework, as a global standard, that is widely considered as a national (macro level) health system planning and monitoring framework.20 The six building blocks include service delivery, health workforce, information, medical products and technologies, financing and leadership and governance.20 While community health programmes are conceptually and operationally related to specific community settings, the framework neglects context-based community health system building.

Recently, there has been growing interest in considering factors defined at multiple levels in public health research and intervention using social-ecological framework. Social-ecological, multilevel framework is particularly appropriate for research designs where data from participants are organised at more than one level. The framework is also ideal for examining how different levels of determinant of health are interdependent.29–32 This kind of approach allows multilevel context understanding and response from individual, to interpersonal, to community and to system-level determinants of CHWs’ engagement.

To our knowledge, no systematic review has addressed the perceived barriers to and enablers of different levels of determinants of the CHWs’ effectiveness in SSA. The objective of this systematic review is thus to examine perceived barriers to and enablers of different levels of determinants of the CHWs’ engagement in ensuring MCH equity and a resilient community health system in SSA. It is expected that such organised evidence will provide a comprehensive understanding of the multilevel determinants of CHWs’ effectiveness. Also, the review findings may inform health policy actors and practitioners to adopt tailored multilevel MCH/CHWs programmes guided by a socio-ecological framework.

This systematic review was guided by the following question: What are the CHWs’ perceived barriers to and facilitators of effectiveness of CHWs to ensure MCH equity and a resilient community health system in SSA?

Methods

Registration and reporting

We registered a protocol for this review on PROSPERO (registration ID: CRD42020206874). Hence, this review is reported in accordance with the reporting guidance provided in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) statement33 (online supplemental file 1). This review was conducted following the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook of Systematic Reviews.34 Our systematic review is organised in accordance with the reporting guidance provided in the PRISMA statement33 and the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research statement.35

bmjgh-2021-008162supp001.pdf (122.9KB, pdf)

Eligibility: inclusion and exclusion criteria

This is a qualitative review based on the lived experiences of CHWs providing MCH services in SSA. As such, we included qualitative studies published in English, between January 2000 and September 2021, and in SSA. Since the launch of Millennium Development Goals in 2000, the quality of interventions targeting MCH in low-income and middle-income countries has improved starkly. This has continued with the launch of the current SDGs in 2015. Hence, 2000–2021 represents the period where substantial international resources were channelled towards alleviating the poor state of MCH in low-income and middle-income countries. Included studies were selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. The eligibility criteria were organised using the Population, Intervention, Control group, Outcome and Study design framework (table 1).

Table 1.

Study selection: inclusion and exclusion criteria

| PICOS strategy | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Population |

|

|

| Intervention |

|

|

| Comparison |

|

|

| Outcome |

|

|

| Study design |

|

|

CHWs, community health workers; MCH, maternal and child health; SSA, sub-Saharan Africa.

Information sources, searching and study selection

Electronic searches: the primary source of literature was based on a structured search of the following major electronic databases: Medline (Ovid), EMBASE, CINAHL and Global Health for relevant peer-reviewed articles published between 2000 and 2021. The search strategies were designed to access published materials in three stages. (i) A limited search of Ovid Medline to identify relevant keywords contained in the title, abstract and subject descriptors. (ii) Terms identified in this way, and the synonyms used by Ovid Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL and Global Health are used in an extensive search of the literature. (iii) We perused the reference lists of the review eligible full-text articles to identify and include more relevant articles that may have been missed by the databases (eg, not indexed). The search was designed and conducted by the review team, which includes three experienced public health researchers, in collaboration with a Health Sciences librarian. This team composition and collaboration with the information specialist helped to optimise the searching, retrieval of relevant citations, citation management, source selection and bias assessment. The search included a broad range of Medical Subject Headings terms and keywords related to MCH services, CHWs, facilitators/enablers, barriers/challenges, effectiveness, qualitative and mixed method study and SSA countries. See online supplemental file 2 for more information on the search strategy.

bmjgh-2021-008162supp002.pdf (72.2KB, pdf)

Screening and selection of studies

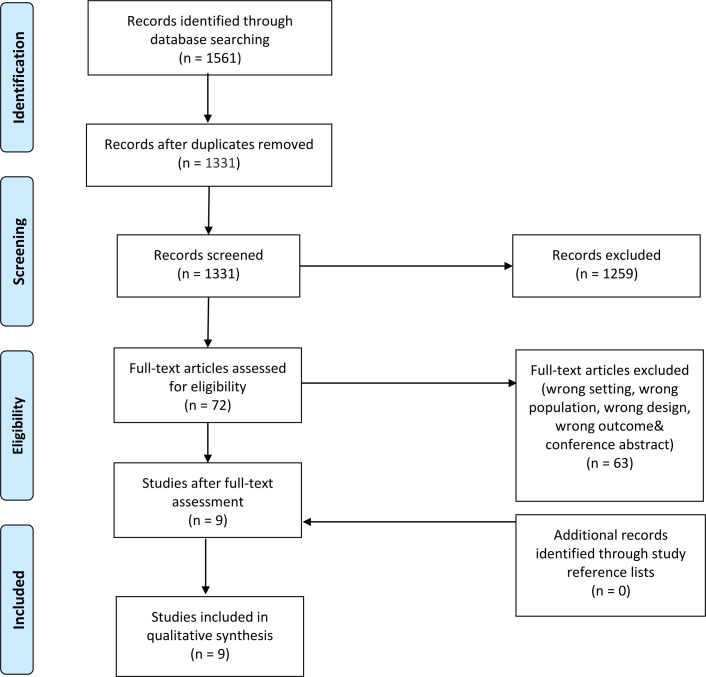

The articles retrieved from searches in each database were first uploaded into the Covidence article online management system. Then, two authors (ATG and OO) screened the articles in Covidence database for their relevance and eligibility to the review. Specifically, this included title and abstract screening, followed by full-text screening against the eligibility criteria for studies deemed potentially eligible. At both stages, disputes were resolved through discussion. The PRISMA flow chart was used to document the selection process.36

Assessment of methodological quality

Methodological rigour in this review was conducted by two (ATG and OO) independent reviewers to critically appraise the methodological validity of the included studies using the appropriate Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklists. The domains of the CASP checklists was used to assess the credibility of the findings and the rigour of the studies.37 The use of these questions guided the reviewers when critically appraising the articles. The tool has 10 questions that each focuses on a different methodological aspect of a qualitative study. We used the scoring system developed by Butler et al to rate studies as high quality, moderate quality or low quality and report individual study assessments score.38 Reviewers determined the quality of the questions using three weighting categories: 1 point for each ‘yes’, 0.5 points for ‘cannot tell’ and 0 points for ‘no’. Accordingly, included studies were assigned an overall score of ‘high’ (9–10), ‘moderate’ (7.5–9) or ‘low’ (<7.5) overall quality. We did not exclude or weighted based on their quality. The results of the appraisal instead were used to inform data interpretation and help confirm the validity of review findings and conclusions. Differences in the quality assessment were first resolved through discussion between ATG and OO. In the absence of consensus, the disagreements were reviewed and resolved through discussion with the third reviewer (SY).

Data extraction and management

Following full-text screening, data were independently extracted from the retrieved eligible studies by two of the reviewers (ATG and OO). Disagreements were settled through discussion with a third reviewer (SY). The authors adapted a data collection from a standardised Cochrane library form, based on the needs of the review.39

ATG and OO extracted data, including all details specific to the review question required fulfil the requirements for a framework analysis. These details included the following information from each article: authors and publication year, study setting, study objective, data collection methods, number of CHW participants; different levels of CHWs’ perceived barriers to and facilitators of effectiveness of CHWs’ engagement in MCH programme and in building a resilient community health system.

Data synthesis

We used the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions to report the results. A PRISMA flow chart is used to present the process of study selection for both the overview and the systematic review. Evidence tables of an overall description of the included studies, including data from each paper that provided details of study characteristics like the authors and year, setting, objective, country, study type and participant characteristics/gender are used to build evidence tables for eligible studies to provide an overall description of included studies.

We used the ‘best fit’ framework method as a systematic and flexible approach in analysing the qualitative data.40–42 Framework-based synthesis using the ‘best fit’ strategy is a highly pragmatic and useful approach for a range of policy-related questions and for understanding complex context.43 44 Framework analysis is a five-stage process that includes familiarisation with the data, identifying a thematic framework, indexing (applying the framework), charting and mapping and interpretation.45 Based on multiple team discussions, we selected the socio-ecological framework,29 30 due to its unique emphasis on multilevel determinants of health intervention success or failure. The socio-ecological framework posits that factors at various levels uniquely and jointly contribute to health interventions. The socio-ecological framework was used to identify the multilevel determinants of perceived barriers to and enablers of CHWs' effectiveness in building a resilent community health system: These multilevels include: individual (CHWs competency), to interpersonal, to community and to health system-level determinants of effective CHWs programme.26 29 30 46

A reviewer coded the data into the four levels/domains of the socio-ecological framework (see online supplemental file 3), using a matrix spreadsheet to facilitate analysis; this was verified by a second reviewer. Mapping involved examining the concordant findings, disconformity data and associations between themes and subthemes. Interpretations were guided by our review objectives as well as the emerging themes. Mapping and interpretation were done through discussion with the entire review team.

bmjgh-2021-008162supp003.pdf (163.2KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

As our study is based on secondary data sources, there was no direct patient or public involvement in this research.

Confidence in the evidence

We used the Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (CERQual) tool47 to assess the confidence of the key findings of this review. We defined a key finding as the analytic output (eg, multilevel theme, facilitators and barriers) from our qualitative evidence synthesis, based on data from primary studies. CERQual evaluation is based on four criteria: the methodological limitations of the included studies that support a review finding, the relevance of the included studies to the review question, the coherence of the review findings and the adequacy of the data that contributes to a review finding.

Results

Characteristics of included articles

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow chart representing the stages of study selection, screening and inclusion process for this review. We imported 1561 references for screening in Covidence, which automatically removed 230 duplicates, leaving us with 1331 studies to screen for title and abstract screening. We assessed 72 studies for full-text eligibility, of which only 9 were included.48–56

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the included studies. Included studies were from six SSA countries: Uganda (2), South Africa (1), Tanzania (1), Ethiopia (2), Angola (1) and Rwanda (2). Most of the studies were conducted in rural health settings and most of the participants (CHWs) were female.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included articles

| Study | Objective of the study | Methods of data collection | Data analysis methods | Study country | Study setting (rural/urban) | Number of CHWs by gender |

| Musabyimana et al48 | To examine perceptions of CHWs and others regarding RapidSMS Rwanda, an mHealth system | FGD (10) and IDI (28) | Thematic content analysis | Rwanda | Rural | 36 (33 females and 3 males) |

| Okuga et al49 | To explore CHWs understanding of promoting MCH practices and factors that influence their performance | FGD (4) and IDI (34) | Thematic content analysis | Uganda | Rural and urban | 32 (both genders, not disaggregated) |

| Naidoo et al50 | To examine the training needs of CHWs working in the field of childhood disorders and disabilities to improve the future training of CHWs and service delivery | 5 FGD (5) and 4 IDI (4) | Thematic content analysis | South Africa | Urban | 28 (females) |

| Dillip et al51 | To explore barriers and enablers to increasing timely access to care by linking the three levels of healthcare provision | FGD (5) and IDI (96) | Thematic content analysis | Tanzania | Rural and urban | 45 (females) |

| Jackson and Hailemariam52 | To examine the barriers and facilitators for CHWs as they refer women to mid-level health facilities for birth | IDIs (59) | Thematic content analysis | Rural | 59 (females) | |

| Giugliani et al53 | To assess implementation process of CHWs programme in Angola | Mixed method, FGD (6) and 9 IDI (9) | Thematic content analysis | Angola | Urban/Municipal | 48 (both genders, not disaggregated) |

| Kok et al54 | To examine the relationships between CHWs, the community and health sector in order to inform policy in providing maternal health services | FGD (14) and IDI (44) | Theme content analysis | Ethiopia | Rural | 69 (females) |

| Mwendwa55 | To explore potential for mHealth technologies to support CHWs in delivering basic maternal and newborn services; examines the challenges and opportunities faced by CHWs who use a mHealth tool, RapidSMS in Rwanda | FGD (14) | Thematic network analysis | Rwanda | Rural | 98 (females) |

| Ludwick et al56 | To examine a qualitative evaluative framework and tool to assess CHW team performance in a district programme in rural Uganda | FGD (8) | Thematic content analysis | Uganda | Rural | 64 (both genders, not disaggregated) |

CHW, community health worker; FGD, focus group discussion; IDI, in-depth interviews; MCH, maternal and child health; mHealth, mobile health.

Quality appraisal

Overall, eight of the studies had a high methodological quality, while one had a moderate methodological quality (table 3). Studies with a moderate quality did not adequately explain the potential bias and the theme analysis process.

Table 3.

Summary of quality appraisal scores based on 10 CASP checklist questions

| CASP checklist questions | Musabyimana et al48 | Okuga et al49 | Naidoo et al50 | Dillip et al51 | Jackson and Hailemariam52 | Giugliani et al53 | Kok et al54 | Mwendwa55 | Ludwick et al56 |

| Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? Record a ‘yes’ or ‘cannot tell’ or ‘no’ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? Record a ‘yes’ or ‘cannot tell’ or ‘no’ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? Record a ‘yes’ or ‘cannot tell’ or ‘no’ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? Record a ‘yes’ or ‘cannot tell’ or ‘no’ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? Record a ‘yes’ or ‘cannot tell’ or ‘no’ |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? Record a ‘yes’ or ‘cannot tell’ or ‘no’ | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? Record a ‘yes’ or ‘cannot tell’ or ‘no’ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? Record a ‘yes’ or ‘cannot tell’ or ‘no’ | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Is there a clear statement of findings? Record a ‘yes’ or ‘cannot tell’ or ‘no’ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| How valuable is the research? Record a ‘yes’ or ‘cannot tell’ or ‘no’ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Over all score and comment | 9.5 (highly valuable) | 9 (moderately valuable) | 9.5 (highly valuable) | 10 (highly valuable) | 8.5 (moderately valuable) | 10 (highly valuable) | 10 (highly valuable) | 10 (highly valuable) | 10 (highly valuable) |

CASP, Critical Appraisal Skills Programme.

Framework analysis: multilevel perceived barriers to and facilitators of CHWs’ effectiveness

Using socio-ecological framework analysis (table 4), we identified four levels of determinants of CHWs’ effectiveness to ensure MCH: individual/CHWs, interpersonal, community and health stream and logistics. The summary of the key themes and subthemes of perceived barriers to and facilitators of multilevel determinants of CHWs are presented below (for the details, see online supplemental file 3).

Table 4.

CERQual summary of findings

| Outcome | CERQual assessment of confidence in the evidence | Explanation of CERQual assessment | Number of studies contributing to the review finding |

| Perceived barriers to and facilitators of | Moderate confidence | Majority of the studies were consistent in reporting barriers to and facilitators of CHWs’ effectiveness based on the lived experience of CHWs. Minor concerns were attributed to small sample size influences generalisability to SSA. This may be due to our review limitation. |

9 |

| Different levels of determinants of of CHWs | Low confidence | Significant concerns were raised regarding the generalisability of study findings due to methodological limitations, such as limited/ absence of multilevel analysis of determinant of CHWs’ effectiveness based on the lived experience of CHWs. Other concerns were about the research design (lack of multilevel analysis). | 9 |

CERQual, Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research; CHW, community health worker; SSA, sub-Saharan Africa.

Key findings

Our review identified four levels of determinants of effective CHWs/MCH programme in SSA. Under each level, we identified perceived barriers to and facilitators of CHWs/MCH programme effectiveness.

Multilevel perceived barriers to CHWs’ effectiveness

Our review identified four key themes and eight subthemes of perceived barriers to CHWs/MCH programme effectiveness.

Individual level

Lack of competence

The subthemes include:

(i) Knowledge and skill gap: CHWs had low satisfaction because of the limited trainings content and quality.48–52 54 55

…we call the Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs) to assist labour due to the skill gap and [low] confidence we have. …we attend the deliveries with their help.54

(ii) Lack of motivation: because of their inadequate training and competence demotivation was noted among the CHWs.48–50 54

CHWs need more motivation, motivation is dropping with time. I think this lack of motivation may increase the turnover rate.48

Interpersonal level

Lack of collaboration

The subthemes include:

(i) Weak teambuilding: there was a weak supportive team approach that hindered CHWs deliverables.49–51 56

The healthcare workers don’t support our work at all…they don’t respect us at all. They don’t think the referrals are important to them; they just throw them away and don’t even want to hear about them. They even ask patients whether they think it is the referral we give them that will treat them.56

(ii) Weak communication strategies: there was an absence of effective interpersonal communication strategies in both personal and professional settings.50 51 56

I think we have to know where exactly we must refer a person … or who we must call …50

Community level

The sociocultural influence

The subthemes include:

(i) Cultural beliefs and practices: pregnancy and newborn are surrounded by many cultural beliefs and traditional practices.49 50 52

… sometimes the mother doesn’t open the home for you…, and sometimes even if you go to the home, rocks are thrown at you.50

(ii) Gender prejudice: gender is a sociocultural construct that refers to the characteristics of women and men. Gender norms and roles affected MCH service utilisation in some cases. For instance, pregnancy and newborn are surrounded by many cultural beliefs and traditional practices.52 54 Some pregnant women prefer to give birth at the health post where the female CHWs work, but those CHWs have no training and equipment to provide delivery service.52 54

At the health post (where a female CHWs work), they can tell us their secrets like a sister—they can’t talk about these things to people they don’t know …52

Health system and logistics level

Fragile health and logistics system

The subthemes include:

(i) Fragmentation of empowerment of CHWs programme: fragmentation of empowerment of CHWs programme was due to various factors: insufficient and lack of continuity of coordination of CHWs/MCH programme; training and professional development strategy; motivation strategies; referral and supportive supervision that can directly or indirectly affect the MCH service accessibility and health outcome policy/system.48–56

Almost one year now and I do not have a referral book; sometimes I just write the referral on a piece of paper…50

(ii) Logistics and basic supply/resource challenge: CHWs experienced multiple challenges to undertake their work and their effectiveness. These challenges include lack of essential medical devices, lack of office materials for the job, limited access to ambulance service, transportation challenge and absence of health facility in the neighbourhood and the like.48 49 51–55

When you make promises and do not deliver on these promises, this begins to discredit our work. ‘Give me a mosquito net?’ ‘No, next week we’ll bring’ successively and we start to lose that confidence from our families.53

Mothers at times deliver on the way to the health centre before an ambulance comes.55

Multilevel perceived facilitators of CHWs’ effectiveness

Our review identified four key themes and eight subthemes of perceived facilitators of CHWs/MCH programme effectiveness.

Individual level

CHWs empowerment

The subthemes include:

(i) Continuous training and professional development strategy: continuous training and professional development empowered CHWs by raising their competency, job satisfaction and work outcomes.50 51 53 (ii) Mobile technology access and use: CHWs were very pleased to use technology to enhance their performance on MCH.48 55

Using RapidSMS ‘We can send a message in case the mother has a problem because there is a code for that’.55

(iii) Positive attitude: our review revealed CHWs love their job and willing to provide service for their community.48 50 54

…they [the clients] are our mothers as well, and we are serving our own community. Their children are our children, and the community is my community.54

Interpersonal level

Interpersonal effectiveness

The subthemes include:

(i) Interpersonal trust: CHWs are trusted by the community they serve, there is a mutual trust between CHWs and the community.49 51 52

… The kebele officials and the community give a witness about their satisfaction.54

(ii) Supportive supervision: CHWs had a positive attitude towards supportive supervision, as it provided opportunity for constructive feedback, mentoring and motivation.54 56

If the woreda (district) supervisors come and see our work, we will be happy. We need encouragement from the woreda officials. We will be encouraged by the appreciation for our good work, but our morale will be affected if our good work is ignored.54

Community level

Institutionalisation of community engagement

The subthemes include:

(i) Community participation: community ownership developed through engaging the various social structures that exist in the community.49 52 54

Sometimes the community with the kebel (village) administration gather and evaluate our performance… The kebele officials and the community give a witness about their satisfaction.54

(ii) Culturally relevant health access: CHWs capitalised on social networks to identify pregnant women who would become new clients, learn about births and child health.49 52 54

We are like family. … I learnt that they prefer us to the others at the health center. We go home to home, and we know how people live…Women feel comfortable with us…once I explained to a woman that she should go to the health center because it is a good facility. She replied that she preferred the friendly approach and not the facility.52

Health system and logistic level

Integration and technology

The subthemes include:

(i) Integration of CHWs into health systems: this describes different interconnecting levels of health system service, supply chain, data sources for better health access and outcome.49 51 52

Now the community recognizes us because in the past we were only providing service to specific program, but now we are dealing with almost every health system.51

(ii) Digital initiatives: it was an initiative that demonstrated the integration of technology into CHWs programme to enhance MCH service outcome and information access. RapidSMS is helping in achieving location, information, context and time challenges.48 55

RapidSMS has helped a lot to prevent maternal, child and neonatal death…48

Confidence in the evidence

The GRADE-CERQual confidence in findings ranged from very low to moderate (table 4). Confidence levels were downgraded due to methodological limitations, lack of multilevel design and analysis of determinants of CHWs’ effectiveness based on the lived experience of CHWs.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first review that has attempted to examine the multilevel determinants for an effective CHWs/MCH programme to enhance MCH equity and a resilent community health system in SSA. Using socio-ecological framework analysis (table 4), we identified four levels of CHWs/MCH programme determinants: individual/CHWs, interpersonal, community and health stream and logistics. Under each level, we identified perceived barriers to and facilitators of CHWs/MCH programme effectiveness. Despite the significant body of research on the topic, few studies examined multilevel determinants of CHWs based on lived experience of CHWs/MCH in SSA. There is a need to capture the CHWs’ experience and voice in order to better inform CHWs and a resilient community health system based on context.

Addressing the multilevel barriers

The perceived barriers at the individual level indicate that CHWs felt incompetent due to lack of knowledge, skill and motivation to provide MCH service effectively and confidently.48–52 54 55 This finding is mostly consistent with previous primary and secondary studies conducted in Africa and internationally.2 27 57 Despite the importance of CHWs as frontline workers in the primary health system, evidence from CHW programmes shows that these health workers often lack the knowledge necessary to safely and effectively perform their responsibilities.19 However, there is no universal standard regarding the level of training required for CHWs and their scope of service. CHWs find it difficult to adopt and use digital health solutions due to insufficient training on new digital tools, weak technical support, issues of internet connectivity and other administrative related challenges.2 58 As evidenced in this review, a high workload was reported by CHWs, and this resulted in lower motivation and ultimately lower performance.27 Hence, sustainable empowerment is crucial to address the challenge of CHWs’ empowerment. In particular, sustainable empowerment can help to provide CHWs with the resources, authority, opportunity and motivation to enhance their performance, as well as hold them accountable for their actions and improve their proficiency.

In terms of perceived barriers to the interpersonal level, our review identified poor team work, poor collaboration and insufficient communication mechanisms between health system actors and CHWs.49–51 56 Our finding is consistent with a study conducted in South Africa, where some CHWs described a good relationship between CHWs and professional health workers. Other CHWs in the study reported that their referrals were not accepted by clinic staff, and that some clinic staff lacked confidence and trust in CHWs’ ability to provide appropriate services.59 CHWs need to collaborate and communicate with other health system workers in ways that promote connectivity and enhance MCH outcomes. Also, as health brokers between the community and health systems, CHWs need effective communication skill. Building a strong collaboration among all level health workers can enhance CHWs’ inclusiveness and increases their job motivation.59 Developing shared and common goals, building effective working relationships, reducing the ambiguity of team members’ role and mutual accountability are some of the ways in which an effective team building between CHWs and other members of the health system can be achieved.27 Despite the importance of effective communication to build trust, there is a lack of specific evidence on the interpersonal skills of CHWs necessary for their interaction within the health system and collaboration with community and other stakeholders.

In terms of perceived barriers to the community-level determinants of CHWs’ effectiveness, sociocultural context was identified as key influencer of MCH service utilisation.49 49 50 50 52 52 Some barriers to CHWs’ effectiveness are not a product of the health system itself, but rather arise from the context in which the CHWs work. Sociocultural context can affect CHWs’ performance and acceptance.19 27 57 According to a study conducted in Ethiopia, a number of women in the community preferred to give birth at home assisted by traditional birth attendants (TBAs), rather than soliciting the support of CHWs during labour or birth,52 TBAs were more culturally accepted. In addition, gender prejudice is another impediment to access MCH. Our findings show that pregnant women expressed preference for female CHWs to attend to their health needs and had low interest to be seen by male health workers at the health centre.52 60 From the health service supply perspective, addressing the community-level barriers requires a strong state-society synergy to focus on a resilient community health system building and to focus beyond specific short-term CHWs programme outcomes. In addition, from the health service demand perspective, such problems also need to be addressed in the framework of social determinants of MCH.61

At the structural level, fragmentation of empowerment strategies relating to CHW/MCH programmes was identified as a key barrier of CHWs programme effectiveness in this review.48–56 Previous studies have identified those manifestation as a lack of empowerment and cause of underperformance of CHWs.9 18 20 25 57 62 63 However, we argue that it is not the lack of empowerment, but rather the fragmentation of empowerment strategies that undermines the efforts and performance of CHWs and MCH outcomes. Thus, the fragmentation of empowerment strategies relating to CHW/MCH programmes is one of the major causes of the fragile health and logistics system in SSA. Fragility is the insufficient capacity of the state, system and/or communities to manage, absorb or mitigate risks.2

The fragmentation of CHWs empowerment strategies is linked with the lack of health system level thinking and insufficient budget allocation by countries in SSA and international donors. Therefore, there is a need for countries in SSA and international health initiatives to streamline their funding to build a resilient health system and ensure that CHWs programmes are well funded. There is also a need for actors in the CHWs programme to implement a strong context-based CHWs programme planning and monitoring system to ensure the creation of a more resilient community health system.

Enhancing the multilevel facilitators

Scaling up the success factor of CHWs programme is a path to transforming CHWs programmes while ensuring MCH equity in the era of SDG and beyond. At the individual level, CHWs need sustainable empowerment to enhance their professional capability and to deliver improved MCH services through continuous professional development strategy, and digitally supported approach.48 50 51 53 55 This review showed that effectiveness of CHWs’ engagement is associated with discrete incentives and intrinsic motivation that corresponds with their job demands, complexity, number of hours worked, training and the roles they undertake.17 27 64 65

The perceived facilitator of CHWs’ effectiveness regarding the interpersonal level including interpersonal trust, peer support and supervision were positively related to CHWs’ performance.49 51 52 54 56 CHWs are enthusiastic about providing related services, and pregnant women and their families are willing to listen to the CHWs and to respond to referral. CHWs are a trusted members of the communities they serve.66 67 In the literature, mutual trust between CHWs and patients has proven to facilitate smooth delivery of CHWs’ work, and to lead to better satisfaction.27 67 Hence, CHWs have the potential to serve as catalyst to improve health service utilisation. Some community members do not trust the CHWs for the reason that they are not adequately trained to handle some health-related confidentiality.68 In a multisite study based in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Kenya, Malawi and Mozambique, the authors found that the lack of trust led to lower CHW motivation and performance. Supportive on-site visits, mentoring and feedback can enhance the motivation and performance of CHWs. In South Africa, supervisors raised communication skill of CHWs through mentoring and feedback.59

In terms of perceived facilitators at the community level, the review highlights the importance of institutionalisation of community engagement for better CHW/MCH programme effectiveness.49 52 54 CHWs have an intermediate position, bridging the community and the health system, and act as cultural brokers and social change agent.64 Institutionalisation of community engagement is key to enhancing community participation while planning, promoting and monitoring community-based health systems. In several studies, embedment of CHWs in community was found to improve the health system performance and outcome performance and credibility.27 69 Such engagement could help the realisation of social accountability, culturally relevant health access and overcoming some of the sociocultural barriers identified by this review.52 54 For example, CHWs in Uganda felt that they needed increased support from community leaders in order to alleviate community stigma towards family planning.19 However, there is insufficient evidence on institutionalisation of community engagement, in the context of a strong state-society relations to scale up the success lessons and address the failure at local community health system.

Regarding structural level of determinants of CHWs, our review identified integration of CHWs programme into health systems and digital technology initiatives as a perceived facilitator of CHWs’ effectiveness in improving MCH access.49 51 52 Integration of CHWs into the health system is among the key factors of a successful CHW programme.70 Increasingly, health systems are shifting tasks formerly performed by clinic staff to CHWs as a strategy to resolve human resources shortages.19 On the other hand, effective integration of CHWs into the health system requires working with multisectoral stakeholders. For example in Tanzania, integration has not been optimal because of inadequate planning, logistic and technical resource constraints.71 More evidence are needed on integration of CHWs into the health system for evidence-based policy and scaling up the good practices.72 In addition, our review highlights empowering CHWs with technology solutions is showing a promising result; mobile health has considerable potential to reach many individuals, even in settings with limited infrastructure and human resources.48 55 Our finding is consistent with other findings.58 73 Digitally supported CHW programmes have been shown to increase CHW performance across a range of geographical locations and contexts. For example, escalating mobile-based reminders resulted in 86% reduction in the number of days a CHW’s routine visits were overdue.74 75

Overall, the socio-ecological framework provided a lens for understanding the diverse context that impedes or enhance CHWs’ engagement and effectiveness at different levels.

Limitation and strengths

This study has multiple limitations that can create publication bias. First, we excluded CHWs studies not reported in the English language, which can result in the exclusion of valuable data from research based on other languages, such as French, Swahili or Arabic. We have no studies from West African countries. The second limitation is that data for the study were only retrieved from four online databases, including MEDLINE, Global Health, Web of Science and EMBASE. Despite using a rigorous search strategy, our review resulted in few qualitative studies based on the lived experiences of CHWs.

Nevertheless, our systematic review has identified multilevel perceived barriers to and facilitators of CHWs’ effectiveness to ensure MCH equity and a resilent community health system in SSA. One of the strengths of this review is that the process undertaken was systematically documented, enabling the audience to assess for bias and credibility. The iterative step-by-step process adhered to when conducting this study, as stipulated in the ‘Methods’ section of this review, enabled the minimisation of possible bias at the various stages involved. Such an evidence base has the potential to provide an opportunity to better plan and implement and improve MCH. Hence, this review would be of value to decision makers, policy makers, practitioners and members of the community with interest in supporting the MCH equity and a resilient community health. Additionally, this review would contribute to the campaign for transformation of CHWs through tailored multilevel intervention and sustainable CHWs empowerment strategies to address the barriers and enhance the facilitators of MCH equity and a resilient community health system.

Conclusion

In SSA, the transformation of CHWs programmes should be a priority to ensure MCH equity and a resilient health system in the era of SDG and beyond through adopting tailored multilevel MCH/CHW programme guided by the socio-ecological framework. Our study has revealed that the effectiveness of CHWs is determined beyond a particular WHO health system building blocks; multilevel reinforcing and interdependent contextual factors determine the effectiveness of CHWs. Effective CHWs programmes require an understanding of the multilevel socio-ecological context of the CHWs to address the system-wide contextual barriers and to scale up the facilitators. The findings from this review have several implications for future policy and research on CHWs/MCH programme planning, empowering and monitoring. However, from a socio-ecological perspective and what can be inferred from the studies included in this review, future research should focus on multilevel interventions, impact of fragmentation of empowerment on CHW/MCH programme, trust building, culturally relevant MCH access and improving poor referral systems to enhance MCH equity and a resilient community health system.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Stephanie M Topp

Contributors: ATG conceived the paper, conducted the study and drafted the manuscript. ATG developed the search strategies in collaboration with a librarian. ATG and OO conducted the screening, extraction and quality appraisal of studies. SY and OO supervised the study and guided the writing of the manuscript. OO and SY critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. SY, the corresponding author, attest that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. All authors read, reviewed and approved the final manuscript. SY had final responsibility to submit for publication.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

The data reported and supporting this paper was sourced from the existing literature, therefore are available through the detailed reference list.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Perry HB, Hodgins S. Health for the people: past, current, and future contributions of national community health worker programs to achieving global health goals. Glob Health Sci Pract 2021;9:1–9. 10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gebremeskel AT, Otu A, Abimbola S, et al. Building resilient health systems in Africa beyond the COVID-19 pandemic response. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e006108. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yaya S, Ghose B. Global inequality in maternal health care service utilization: implications for sustainable development goals. Health Equity 2019;3:145–54. 10.1089/heq.2018.0082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . countdownreportpages11-21.pdf [Internet]. Available: https://www.who.int/pmnch/topics/child/countdownreportpages11-21.pdf [Accessed 01 Oct 2020].

- 5.Health Quality Ontario . Insights into quality improvement, health equity in the 2016/17 quality improvement plans: 16. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinney MV, Kerber KJ, Black RE, et al. Sub-Saharan Africa’s Mothers, Newborns, and Children: Where and Why Do They Die? PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000294. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . Com L. closing the health equity gap, 2013: 62. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . Everybody’s Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes : WHO’s Frmaework for Action. World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kruk ME, Myers M, Varpilah ST, et al. What is a resilient health system? lessons from Ebola. The Lancet 2015;385:1910–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60755-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ronsmans C, Graham WJ, Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group . Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet 2006;368:1189–200. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69380-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberton T, Carter ED, Chou VB, et al. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e901–8. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30229-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United Nations . Mdg 2015 Rev (July 1).pdf. Available: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf [Accessed 07 Mar 2021].

- 13.International Development Research Center . Innovating for Maternal and Child Health in Africa | IDRC - International Development Research Centre. Available: https://www.idrc.ca/en/initiative/innovating-maternal-and-child-health-africa [Accessed 03 Jul 2021].

- 14.Maternal Health Task Force . The sustainable development goals and maternal mortality. maternal health Task force, 2017. Available: https://www.mhtf.org/topics/the-sustainable-development-goals-and-maternal-mortality/ [Accessed 17 Sep 2020].

- 15.Chopra M, Sharkey A, Dalmiya N, et al. Strategies to improve health coverage and narrow the equity gap in child survival, health, and nutrition. The Lancet 2012;380:1331–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61423-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Public Health Association . Community health workers, 2000. Available: https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/communityhealthworkers [Accessed 04 Apr 2021].

- 17.Perry HB, Chowdhury M, Were M, et al. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 11. CHWs leading the way to "Health for All". Health Res Policy Syst 2021;19:111. 10.1186/s12961-021-00755-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puett C, Alderman H, Sadler K, et al. 'Sometimes they fail to keep their faith in US': community health worker perceptions of structural barriers to quality of care and community utilisation of services in Bangladesh. Matern Child Nutr 2015;11:1011–22. 10.1111/mcn.12072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.United States Agency for International Development (USAID) . Barriers-to-CHW-Svc-Provision-Lit-Review-June2015.pdf. Available: https://healthcommcapacity.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Barriers-to-CHW-Svc-Provision-Lit-Review-June2015.pdf [Accessed 01 Nov 2021].

- 20.World Health Organization . Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a Handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. World Health Organization, 2010. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/258734 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanchard AK, Prost A, Houweling TAJ. Effects of community health worker interventions on socioeconomic inequities in maternal and newborn health in low-income and middle-income countries: a mixed-methods systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001308. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott K, Beckham SW, Gross M, et al. What do we know about community-based health worker programs? A systematic review of existing reviews on community health workers. Hum Resour Health 2018;16:39. 10.1186/s12960-018-0304-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ballard M, Montgomery P. Systematic review of interventions for improving the performance of community health workers in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014216. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lassi ZS, Bhutta ZA. Community‐based intervention packages for reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and improving neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD007754. 10.1002/14651858.CD007754.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kane K, Ormel O, et al. Limits and opportunities to community health worker empowerment: a multi-country comparative study | Elsevier enhanced reader 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Center for Disease Control . The Social-Ecological model: a framework for prevention |Violence Prevention|Injury Center|CDC, 2020. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/publichealthissue/social-ecologicalmodel.html [Accessed 13 Nov 2020].

- 27.Kok MC, Dieleman M, Taegtmeyer M, et al. Which intervention design factors influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? A systematic review. Health Policy Plan 2015;30:1207–27. 10.1093/heapol/czu126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization . Research on community-based health workers is needed to achieve the sustainable development goals. Available: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/94/11/16-185918/en/ [Accessed 04 Apr 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Diez Roux AV. Next steps in understanding the multilevel determinants of health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:957–9. 10.1136/jech.2007.064311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wold B, Mittelmark MB. Health-promotion research over three decades: the social-ecological model and challenges in implementation of interventions. Scand J Public Health 2018;46:20–6. 10.1177/1403494817743893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The World Health Organization . Core principles of the ecological model | models and mechanisms of public health, 2018. Available: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-buffalo-environmentalhealth/chapter/core-principles-of-the-ecological-model/ [Accessed 02 Nov 2021].

- 32.Ostrom E. Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems. Am Econ Rev 2010;100:641–72. 10.1257/aer.100.3.641 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Julian H, Sally G. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 2008.

- 35.Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:181. 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Panic N, Leoncini E, de Belvis G, et al. Evaluation of the endorsement of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement on the quality of published systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS One 2013;8:e83138. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme . CASP Checklists. CASP - Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Available: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ [Accessed 20 Sep 2020].

- 38.Butler A, Hall H, Copnell B. A guide to writing a qualitative systematic review protocol to enhance evidence-based practice in nursing and health care. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2016;13:241–9. 10.1111/wvn.12134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cochrane data extraction forms. Available: /data-extraction-forms [Accessed 27 Sep 2020].

- 40.Carroll, Booth, Leaviss and Rick . “Best fit” framework synthesis: refining the method | BMC Medical Research Methodology | Full Text. Available: https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2288-13-37 [Accessed 02 Nov 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Booth A, Carroll C. How to build up the actionable knowledge base: the role of 'best fit' framework synthesis for studies of improvement in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:700–8. 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dixon-Woods M. Using framework-based synthesis for conducting reviews of qualitative studies. BMC Med 2011;9:39. 10.1186/1741-7015-9-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flemming K, Booth A, Garside R, et al. Qualitative evidence synthesis for complex interventions and guideline development: clarification of the purpose, designs and relevant methods. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e000882. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Analyzing qualitative data. Routledge, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paskett E, Thompson B, Ammerman AS, et al. Multilevel interventions to address health disparities show promise in improving population health. Health Aff 2016;35:1429–34. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implement Sci 2018;13:2. 10.1186/s13012-017-0688-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Musabyimana A, Ruton H, Gaju E, et al. Assessing the perspectives of users and beneficiaries of a community health worker mHealth tracking system for mothers and children in Rwanda. PLoS One 2018;13:e0198725. 10.1371/journal.pone.0198725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okuga M, Kemigisa M, Namutamba S, et al. Engaging community health workers in maternal and newborn care in eastern Uganda. Glob Health Action 2015;8:23968. 10.3402/gha.v8.23968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naidoo S, Naidoo D, Govender P. Community healthcare worker response to childhood disorders: inadequacies and needs. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2019;11:e1–10. 10.4102/phcfm.v11i1.1871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dillip A, Kimatta S, Embrey M, et al. Can formalizing links among community health workers, accredited drug dispensing outlet dispensers, and health facility staff increase their collaboration to improve prompt access to maternal and child care? A qualitative study in Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:416. 10.1186/s12913-017-2382-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jackson R, Hailemariam A. The role of health extension workers in linking pregnant women with health facilities for delivery in rural and Pastoralist areas of Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 2016;26:471–8. 10.4314/ejhs.v26i5.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giugliani C, Duncan BB, Harzheim E, et al. Community health workers programme in Luanda, Angola: an evaluation of the implementation process. Hum Resour Health 2014;12:68. 10.1186/1478-4491-12-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kok MC, Broerse JEW, Theobald S, et al. Performance of community health workers: situating their intermediary position within complex adaptive health systems. Hum Resour Health 2017;15:59. 10.1186/s12960-017-0234-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mwendwa P. Assessing the fit of RapidSMS for maternal and new-born health: perspectives of community health workers in rural Rwanda. Dev Pract 2016;26:38–51. 10.1080/09614524.2016.1112769 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ludwick T, Turyakira E, Kyomuhangi T, et al. Supportive supervision and constructive relationships with healthcare workers support CHW performance: use of a qualitative framework to evaluate CHW programming in Uganda. Hum Resour Health 2018;16:11. 10.1186/s12960-018-0272-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Long H, Huang W, Zheng P, et al. Barriers and facilitators of engaging community health workers in non-communicable disease (Ncd) prevention and control in China: a systematic review (2006–2016). Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:2378. 10.3390/ijerph15112378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feroz AS, Khoja A, Saleem S. Equipping community health workers with digital tools for pandemic response in LMICs. Arch Public Health 2021;79:1. 10.1186/s13690-020-00513-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tseng Y-hwei, Griffiths F, de Kadt J, et al. Integrating community health workers into the formal health system to improve performance: a qualitative study on the role of on-site supervision in the South African programme. BMJ Open 2019;9:e022186. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kok MC, Kea AZ, Datiko DG, et al. A qualitative assessment of health extension workers' relationships with the community and health sector in Ethiopia: opportunities for enhancing maternal health performance. Hum Resour Health 2015;13:80. 10.1186/s12960-015-0077-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hamal M, Dieleman M, De Brouwere V, et al. Social determinants of maternal health: a scoping review of factors influencing maternal mortality and maternal health service use in India. Public Health Rev 2020;41:13. 10.1186/s40985-020-00125-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chandani Y, Noel M, Pomeroy A, et al. Factors affecting availability of essential medicines among community health workers in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Rwanda: solving the last mile puzzle. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012;87:120–6. 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Atuoye KN, Dixon J, Rishworth A, et al. Can she make it? Transportation barriers to accessing maternal and child health care services in rural Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:333. 10.1186/s12913-015-1005-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schaaf M, Warthin C, Freedman L, et al. The community health worker as service extender, cultural broker and social change agent: a critical interpretive synthesis of roles, intent and accountability. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002296. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Colvin CJ, Hodgins S, Perry HB. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 8. incentives and remuneration. Health Res Policy Syst 2021;19:106. 10.1186/s12961-021-00750-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Enguita-Fernàndez C, Alonso Y, Lusengi W, et al. Trust, community health workers and delivery of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy: a comparative qualitative analysis of four sub-Saharan countries. Glob Public Health 2021;16:1889-1903. 10.1080/17441692.2020.1851742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Singh D, Cumming R, Negin J. Acceptability and trust of community health workers offering maternal and newborn health education in rural Uganda. Health Educ Res 2015;30:947–58. 10.1093/her/cyv045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grant M, Wilford A, Haskins L, et al. Trust of community health workers influences the acceptance of community-based maternal and child health services. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2017;9:1281. 10.4102/phcfm.v9i1.1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Perry HB, Zulliger R, Rogers MM. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: an overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu Rev Public Health 2014;35:399–421. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lehmann U, Twum-Danso NAY, Nyoni J. Towards universal health coverage: what are the system requirements for effective large-scale community health worker programmes? BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001046. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mgawe P, Maluka SO. Integration of community health workers into the health system in Tanzania: examining the process and contextual factors. Int J Health Plann Manage 2021;36:703–14. 10.1002/hpm.3114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cometto G, Ford N, Pfaffman-Zambruni J, et al. Health policy and system support to optimise community health worker programmes: an abridged who guideline. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e1397–404. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30482-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Buehler B, Ruggiero R, Mehta K. Empowering community health workers with technology solutions. IEEE Technol Soc Mag 2013;32:44–52. 10.1109/MTS.2013.2241831 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Feroz AS, Khoja A, Saleem S. Using digital health to support community health worker programs. CHWI, 2021. Available: https://chwi.jnj.com/news-insights/using-digital-health-to-support-community-health-worker-programs [Accessed 02 Nov 2021].

- 75.DeRenzi B, Findlater L, Payne J. Improving community health worker performance through automated SMS. Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development. ICTD ’12. Association for Computing Machinery, 2012:25–34. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2021-008162supp001.pdf (122.9KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2021-008162supp002.pdf (72.2KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2021-008162supp003.pdf (163.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

The data reported and supporting this paper was sourced from the existing literature, therefore are available through the detailed reference list.