Abstract

Species in the Fusarium solani species complex are fast growing, environmental saprophytic fungi. Members of this genus are filamentous fungi with a wide geographical distribution. Fusarium keratoplasticum and F. falciforme have previously been isolated from sea turtle nests and have been associated with high egg mortality rates. Skin lesions were observed in a number of stranded, post-hatchling loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) in a rehabilitation facility in South Africa. Fungal hyphae were observed in epidermal scrapes of affected turtles and were isolated. The aim of this study was to characterise the Fusarium species that were isolated from these post-hatchling loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) that washed up on beaches along the South African coastline. Three gene regions were amplified and sequenced, namely the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS), a part of the nuclear large subunit (LSU), and part of the translation elongation factor 1 α (tef1) gene region. Molecular characteristics of strains isolated during this study showed high similarity with Fusarium isolates, which have previously been associated with high egg mortality rates in loggerhead sea turtles. This is the first record of F. keratoplasticum, F. falciforme and F. crassum isolated from stranded post-hatchling loggerhead sea turtles in South Africa.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Molecular biology, Ecology

Introduction

The ascomycete genus Fusarium (Hypocreales, Nectriaceae) is widely distributed in nature and can be found in soil, plants and different organic substrates. This genus represents a diverse complex of over 60 phylogenetically distinct species1–3. Some species, specifically those forming part of the Fusarium solani species complex (FSSC)4, are known pathogenic species, and have been associated with human, plant and animal infections—in both immunocompromised and healthy individuals1,5–8. Phylogenetically, this group comprises three major clades, of which clade I forms the basal clade to the two sister clades II and III. Members of clade I and II are most often associated with plant infections and consequently have limited geographical distributions4. Members of clade III represent the highest phylogenetic and ecological diversity and are most commonly associated with human and animal infections4. Species represented in this clade are typically regarded as fast growing and produce large numbers of microconidia. This facilitates distribution within the host and its environment and promotes virulence. Clade III, further consists of three smaller clades, namely clades A, B and C. While clades A (also known as the F. falciforme clade) and C (also known as the F. keratoplasticum clade) consist predominantly of isolates from humans and animals, plant pathogens constitute most isolates represented in clade B1,7.

Fusarium spp. have been identified in infections of marine animals including (but not limited to); bonnethead sharks (Sphyrna tiburo)9, scalloped hammerhead sharks (Sphyma lewini)10, and black spotted stingray (Taeniura melanopsila)6. Strains from this genus have been reported to cause skin and systemic infections in marine turtles5,11–15, and are considered to be one of many threats to turtle populations worldwide causing egg infections and brood failure in 6 out of seven turtle species7,16. Challenge inoculation experiments provided evidence of pathogenicity for F. keratoplasticum, a causative agent of sea turtle egg fusariosis (STEF) in loggerhead sea turtle populations in Cape Verde17. Since then, Fusarium spp., or more specifically F. falciforme and F. keratoplasticum have increasingly been isolated from turtle eggs and nests. Subsequent research studies have isolated F. falciforme and F. keratoplasticum from infected eggs in turtle nests on beaches along the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans, as well as the Mediterranean and Caribbean Sea15,16,18–23. Both F. keratoplasticum and F. falciforme are pathogenic to turtle eggs and embryos, and are able to survive independent of the hosts7,17. In recent years, members from F. falciforme and F. keratoplasticum of clade III, have been described as emerging animal pathogens, causing both localised and systemic infections6,16,17,23. These infections can result in mortality rates as high as 80–90% in animal populations7,17. Cafarchia and colleagues (2019) suggested that fusariosis should be included in differential diagnosis of shell and skin lesions in sea turtles and that species level identification is required to administer appropriate treatment and infection control12.

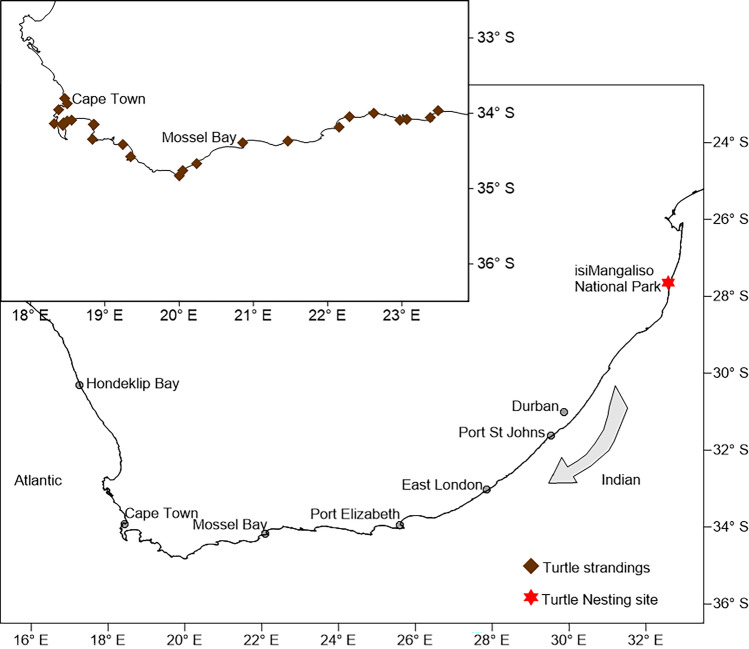

Loggerhead sea turtles nest on the beaches of Southern Africa between November and January24,25. Hatchlings that find their way into the ocean are carried south in the Aghulas current, with some turtles stranding on the South African coast, mainly between the months of March and May each year. Between 2015 and 2016, a total of 222 post-hatchling (turtles that have absorbed the yolk-sac and are feeding in open ocean but have yet to return to coastal waters to enter the juvenile stage) loggerhead sea turtles were admitted to a rehabilitation centre after stranding along the Indian and Atlantic Ocean coastline of South Africa, between Mossel Bay and False Bay (Fig. 1). During their time at the rehabilitation centre a number of these turtles developed skin lesions. Fungal dermatitis was diagnosed based on skin scrape cytology findings. Fungal strains resembling Fusarium were isolated from the affected areas.

Figure 1.

Map showing the South African coastline, indicating nesting sites and sites where post-hatchling sea turtles were found along the coastline between Mossel Bay and False Bay.

The aim of this study was to characterise the strains isolated from skin lesions of post-hatchling loggerhead Sea turtles that washed up on beaches along the South African coastline, and to determine the molecular relationships between these isolates and those strains reported from literature that pose significant conservation risks to sea turtles from other geographic localities.

Materials and methods

Gross observations and Fungal isolations

Post-hatchling turtles with skin lesions were isolated from unaffected turtles. Clinical signs observed were as follows; excessive epidermal sloughing on the limbs, head and neck, where scales on the skin lifted easily and were frequently lost. A softening and sloughing of the carapace and plastron were observed, where scutes of the carapace and plastron became crumbly, soft and were frequently shed. Turtles were diagnosed with fungal skin infection if they had clinical signs of epidermal sloughing and a positive epidermal scrape. Epidermal scrapes taken from lesions of affected turtles were examined by light microscopy (20 to 50 × objective) and deemed positive if significant numbers of hyphae were observed. For fungal isolation, samples (scrapings) were taken from affected areas of skin in a sterile manner and placed onto culture media. During 2015 and 2016, 10 fungal isolates were isolated from 10 clinically affected loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) onto marine phycomycetes isolation agar (12.0 g Agar, 1.0 g Glucose, 1.0 g Gelatin hydrolysate, 0.01 g Liver extract, 0.1 g Yeast extract, 1 000 mL Sea water) supplemented with streptomycin sulphate and penicillin [0.05% (w/ v)] to prevent bacterial growth26. Plates were incubated at 20 °C and monitored daily for fungal growth. Following 3 days of incubation, emerging hyphal tips were aseptically transferred with a sterile needle onto potato dextrose agar (PDA) and incubated. Single spore cultures were obtained by taking a needle tip full of hyphae from a 14 day old culture on PDA, mixing it with 1 mL sterile MilliQ water and spreading 80 µL onto 1.5% water agar plates. Plates were incubated overnight at room temperature. Following incubation, 8 single, germinated microconidia were transferred onto 2 PDA plates (4 microconidia on each plate). After 3 days of incubation at 26 ± 1 °C, all 8 colonies were examined. Colonies with similar colour and hyphal growth were regarded as the same isolate and one colony was selected for characterisation. When differences were observed, one of each different colony was selected for further characterisation. Based on gross observations of single spore colonies 14 distinct isolates were identified for molecular characterisation. Agar plugs (6 mm diameter) of the chosen colonies were transferred onto PDA and incubated at 26 ± 1 °C for 7 days.

DNA extractions, molecular characterisation, and phylogenetic analyses

Total genomic DNA was extracted from single spore colonies following incubation for 7 days on PDA. A heat lysis DNA extraction protocol was used27. Extracted DNA were stored at − 20 °C until needed. Molecular characterisation was performed based on 3 gene regions for 14 strains. The gene regions included internal transcribed spacer region (ITS), a part of the nuclear large subunit (LSU) and partial translation elongation factor 1-α (tef1) gene region28. PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 25 µL, containing 100–200 ng genomic DNA. Kapa ReadyMix (Kapa Biosystems; Catalog #KK1006) was used for PCR reactions. Conditions for the PCR amplification were as follows. Initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C for 45 s, 45 s annealing (see Table 1 for specific annealing temperatures) and 72 °C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. Purified PCR products were sequenced by using BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) and an ABI PRISM 310 genetic analyser. Sequencing was done in one direction. Each sequence was edited in BioEdit sequence alignment editor v7.2.5. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using the dataset from Sandoval-Denis et al. (2019) combining sequences of three loci (LSU, ITS and tef1) to identify species28–32 (Table 2 lists all the sequences included in the phylogenetic analyses). Alignments were done in ClustalX using the L-INS-I option. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using Maximum likehood (ML) analysis, with GTR + I + G. The partitioning scheme and substitution models were selected using Partitionfinder v 2.1.133. The software package PAUP was used to construct the phylogenetic trees and confidence was calculated using bootstrap analysis of 1 000 replicates. Geejayessia atrofusca was used as an outgroup. A Bayesian analysis was run using MrBayes v. 3.2.634. The analysis included four parallel runs of 500 000 generations, with a sampling frequency of 200 generations. The posterior probability values were calculated after the initial 25% of trees were discarded.

Table 1.

Primers used for amplification and sequencing.

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5′ – 3′) | Annealing temperature (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ITS 1 | TCC GTA GGT GAA CCT GCG G | 51.1 | 41 |

| ITS 4 | TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC | 41 | |

| LSU-00021 | ATT ACC CGC TGA ACT TAA GC | 63.0 | 42 |

| LSU-1170 | GCT ATC CTG AGG GAA ATT TCG G | 43 | |

| EF1 | ATG GGT AAG GAR GAC AAG AC | 53.6 | 31 |

| EF2 | GGA RGT ACC AGT SAT CAT GTT | 31 |

Table 2.

Fusarium strains included in the phylogenetic analyses.

| Species name | Strain number | Genbank accession number | Source | Origin | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | LSU | EF | |||||

| Geejayessia atrofusca (outgroup) | NRRL 22316 | AF178423 | AF178392 | AF178361 | Staphylea trifolia | USA | 28 |

| F. ambrosium | NRRL 20438 | AF178397 | DQ236357 | AF178332 | Euwallacea fornicatus on Camellia sinensis | India | 28 |

| NRRL 22346 = CBS 571.94ET | EU329669 | EU329669 | FJ240350 | Euwallacea fornicatus on Camellia sinensis | India | 28 | |

| F. bostrycoides | CBS 130391 | EU329716 | EU329716 | HM347127 | Human eye | Brazil | 28 |

| CBS144.25NT | LR583704 | LR583912 | LR583597 | Soil | Honduras | 28 | |

| NRRL 31169 | DQ094396 | DQ236438 | DQ246923 | Human oral wound | USA | 28 | |

| F. catenatum | CBS 143229 T = NRRL54993 | KC808256 | KC808256 | KC808214 | Stegostoma fasciatum multiple tissues | USA | 28 |

| NRRL 54992 | KC808255 | KC808255 | KC808213 | Stegostoma fasciatum multiple tissues | USA | 28 | |

| F. crassum | CBS 144386 T | LR583709 | LR583917 | LR583604 | Unknown | France | 28 |

| NRRL 46596 | GU170647 | GU170647 | GU170627 | Human toenail | Italy | 28 | |

| NRRL 46703 | EU329712 | EU329712 | HM347126 | Nematode egg | Spain | 28 | |

| ML16006 | OM574602 | ON237616 | ON237630 | Caretta caretta post-hatchling | South Africa | This study | |

| ML16011 | OM574607 | ON237621 | ON237635 | Caretta caretta post-hatchling | South Africa | This study | |

| ML16012 | OM574608 | ON237622 | ON237636 | Caretta caretta post-hatchling | South Africa | This study | |

| F. euwallaceae | NRRL 54722 = CBS 135854 T | JQ038014 | JQ038014 | JQ038007 | Euwallacea fornicatus on Persea americana | Israel | 28 |

| NRRL 62626 | KC691560 | KC691560 | KC691532 | Euwallacea fornicatus on Persea americana | USA | 28 | |

| F. falciforme | 033 FUS | KC573932 | KC573883 | Chelonia mydas eggshells | Ecuador | 7 | |

| 078 FUS | KC573938 | KC573884 | Caretta caretta embryo | Cape Verde | 7 | ||

| 079 FUS | KC573939 | KC573885 | Caretta caretta eggshells | Cape Verde | 7 | ||

| 099 FUS | KC573956 | KC573886 | Caretta caretta embryo | Cape Verde | 7 | ||

| F. falciforme (cont.) | 142 FUS | KC573987 | KC573887 | Chelonia mydas eggshells | Ecuador | 7 | |

| 181 FUS | KC573990 | KC573888 | Natator depressus eggshells | Australia | 7 | ||

| 182 FUS | KC573991 | KC573889 | Natator depressus eggshells | Australia | 7 | ||

| 209 FUS | KC574000 | KC573890 | Lepidochelys olivacea eggshells | Ecuador | 7 | ||

| 215 FUS | KC574002 | KC573891 | Lepidochelys olivacea eggshells | Ecuador | 7 | ||

| 219 FUS | KC574004 | KC573892 | Lepidochelys olivacea eggshells | Ecuador | 7 | ||

| CBS 121450 | JX435211 | JX435211 | JX435161 | Declined grape vine | Syria | 28 | |

| CBS 124627 | JX435184 | JX435184 | JX435134 | Human nail | France | 28 | |

| CBS 475.67 T | MG189935 | MG189915 | LT906669 | Human mycetoma | Puerto Rico | 28 | |

| ML16007 | OM574603 | ON237617 | ON237631 | Caretta caretta post-hatchling | South Africa | This study | |

| ML16008 | OM574604 | ON237618 | ON237632 | Caretta caretta post-hatchling | South Africa | This study | |

| ML16009 | OM574605 | ON237619 | ON237633 | Caretta caretta post-hatchling | South Africa | This study | |

| NRRL 22781 | DQ094334 | DQ236376 | DQ246849 | Human cornea | Venezuela | 28 | |

| NRRL 28562 | DQ094376 | DQ236418 | DQ246903 | Human bone | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 28563 | DQ094377 | DQ236419 | DQ246904 | Clinical isolate | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 28565 | DQ094379 | DQ236421 | Human wound | USA | 1 | ||

| NRRL 31162 | DQ094392 | DQ236434 | Human | Texas | 1 | ||

| NRRL 32307 | DQ 094405 | DQ236447 | DQ246935 | Human sputum | Unknown | 28 | |

| NRRL 32313 | EU329678 | EU329678 | DQ246941 | Human corneal ulcer | Unknown | 28 | |

| NRRL 32331 | DQ094428 | DQ236470 | DQ246959 | Human leg wound | Unknown | 28 | |

| NRRL 32339 | DQ094436 | DQ236478 | DQ246967 | Human | Unknown | 28 | |

| NRRL 32540 | DQ094471 | DQ236513 | DQ247006 | Human eye | India | 28 | |

| NRRL 32544 | DQ094475 | DQ23651 | DQ247010 | Human eye | India | 28 | |

| NRRL 32547 | EU329680 | EU329680 | DQ247012 | Human eye | India | 28 | |

| NRRL 32714 | DQ094496 | DQ236538 | DQ247034 | Human eye | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32718 | DQ094500 | DQ236542 | DQ247038 | Human eye | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32729 | DQ094510 | DQ236552 | DQ247049 | Human eye | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32738 | DQ094519 | DQ236561 | DQ247058 | Human eye | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32754 | DQ094533 | DQ236575 | DQ247072 | Turtle nare lesion | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32778 | DQ094549 | DQ236591 | DQ247088 | Equine corneal ulcer | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32798 | DQ094567 | DQ236609 | DQ247107 | Human | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 43441 | DQ790522 | DQ790522 | DQ790478 | Human cornea | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 43536 | EF453118 | EF453118 | EF452966 | Human cornea | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 43537 | DQ790550 | DQ790550 | DQ790506 | Human cornea | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 52832 | GU170651 | GU170651 | GU170631 | Human toenail | Italy | 28 | |

| NRRL 54966 | KC808233 | KC808233 | KC808193 | Equine eye | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 54983 | KC808248 | KC808248 | KC808206 | Equine eye | USA | 28 | |

| F. gamsii | CBS 143207 T | DQ094420 | DQ236462 | DQ246951 | Human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid | USA | 28 |

| NRRL 32794 | DQ094563 | DQ236605 | DQ247103 | Humidifier coolant | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 43502 | DQ790532 | DQ790532 | DQ790488 | Human cornea | USA | 28 | |

| F. keratoplasticum | 001 AFUS | FR691753 | JN939570 | Caretta caretta embryo | Cape Verde | 7 | |

| 001 CFUS | FR691754 | KC594706 | Caretta caretta embryo | Cape Verde | 7 | ||

| 009 FUS | FR691760 | KC573903 | Caretta caretta eggshells | Cape Verde | 7 | ||

| 010 FUS | FR691761 | KC573904 | Caretta caretta embryo | Cape Verde | 7 | ||

| 013 FUS | FR691764 | KC573907 | Caretta caretta eggshells | Cape Verde | 7 | ||

| 014 FUS | FR691757 | KC573908 | Caretta caretta eggshells | Cape Verde | 7 | ||

| 015 FUS | FR691759 | KC573909 | Caretta caretta eggshells | Cape Verde | 7 | ||

| F. keratoplasticum (cont.) | 016 FUS | FR691758 | KC573910 | Caretta caretta eggshells | Cape Verde | 7 | |

| 018 FUS | FR691765 | KC573911 | Caretta caretta eggshells | Cape Verde | 7 | ||

| 019 FUS | FR691766 | KC573912 | Caretta caretta eggshells | Cape Verde | 7 | ||

| 021 FUS | FR691768 | KC573913 | Caretta caretta embryo | Cape Verde | 7 | ||

| 028 FUS | KC573927 | KC573914 | Chelonia mydas eggshells | Ecuador | 7 | ||

| 029 FUS | KC573928 | KC573915 | Eretmochelys imbricata eggshells | Ecuador | 7 | ||

| 030 FUS | KC573929 | KC573916 | Eretmochelys imbricata eggshells | Ecuador | 7 | ||

| 034 FUS | KC573933 | KC573918 | Eretmochelys imbricata eggshells | Ecuador | 7 | ||

| 036 FUS | KC573935 | KC573919 | Eretmochelys imbricata eggshells | Ecuador | 7 | ||

| 223 FUS | KC574007 | KC573920 | Eretmochelys imbricata eggshells | Ascencion Island | 7 | ||

| 230 FUS | KC574010 | KC573922 | Eretmochelys imbricata eggshells | Ascencion Island | 7 | ||

| CBS 490.63 T | LR583721 | LR583929 | LT906670 | Human | Japan | 28 | |

| FMR 7989 = NRRL 46696 | EU329705 | EU329705 | AM397219 | Human eye | Brazil | 28 | |

| FMR 8482 = NRRL 46697 | EU329706 | EU329706 | AM397224 | Human tissue | Qatar | 28 | |

| FRC-S 2477 T | NR130690 | JN235282 | JN235712 | Indoor plumbing | USA | 28 | |

| ML16001 | OM574597 | ON237611 | ON237625 | Caretta caretta post-hatchling | South Africa | This study | |

| ML16002 | OM574598 | ON237612 | ON237626 | Caretta caretta post-hatchling | South Africa | This study | |

| ML16003 | OM574599 | ON237613 | ON237627 | Caretta caretta post-hatchling | South Africa | This study | |

| ML16004 | OM574600 | ON237614 | ON237628 | Caretta caretta post-hatchling | South Africa | This study | |

| ML16005 | OM574601 | ON237615 | ON237629 | Caretta caretta post-hatchling | South Africa | This study | |

| ML16010 | OM574606 | ON237620 | ON237634 | Caretta caretta post-hatchling | South Africa | This study | |

| ML16013 | OM574609 | ON237623 | ON237637 | Caretta caretta post-hatchling | South Africa | This study | |

| ML16019 | OM574610 | ON237624 | ON237638 | Caretta caretta post hatchling | South Africa | This study | |

| NRRL 22640 | DQ094327 | DQ236369 | DQ246842 | Human cornea | Argentina | 28 | |

| NRRL 22791 | DQ094337 | DQ236379 | DQ246853 | Iguana tail | Unknown | 28 | |

| NRRL 28014 | DQ094354 | DQ236396 | DQ246872 | Human | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 28561 | DQ094375 | DQ236417 | DQ246902 | Human wound | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32707 | DQ094490 | DQ236532 | DQ247027 | Human eye | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32710 | DQ094492 | DQ236534 | DQ247030 | Human eye | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32780 | DQ094551 | DQ236593 | DQ247090 | Sea turtle | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32838 | EU329681 | EU329681 | DQ247144 | Sea turtle | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32959 | DQ094632 | DQ236674 | DQ247178 | Manatee skin | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 43443 | EF453082 | EF453082 | EF453082 | Human | Italy | 44 | |

| NRRL 43490 | DQ790529 | DQ790529 | DQ790485 | Human eye | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 43649 | EF453132 | EF453132 | EF452980 | Human eye | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 46437 | GU170643 | GU170643 | GU170623 | Human toenail | Italy | 28 | |

| NRRL 46438 | GU170644 | GU170644 | GU170624 | Human toenail | Italy | 28 | |

| NRRL 46443 | GU170646 | GU170646 | Human foot | Italy | 45 | ||

| NRRL 52704 | JF740908 | JF740908 | JF740786 | Tetranychus urticae | USA | 28 | |

| F. lichenicola | CBS 279.34 T | LR583725 | LR583933 | LR583615 | Human | Somalia | 28 |

| CBS 483.96 | LR583728 | LR583936 | LR583618 | Air Brazil | Brazil | 28 | |

| CBS 623.92ET | LR583730 | LR583938 | LR583620 | Human necrotic wound | Germany | 28 | |

| NRRL 28030 | DQ094355 | DQ236397 | DQ246877 | Human | Thailand | 28 | |

| NRRL 34123 | DQ094645 | DQ236687 | DQ247192 | Human eye | India | 28 | |

| F. metavorans | CBS 135789 T | LR583738 | LR583946 | LR583627 | Human pleural effusion | Greece | 28 |

| NRRL 28018 | LR583740 | FJ240360 | DQ246875 | Human | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 28019 | LR583741 | FJ240361 | DQ246876 | Human | USA | 28 | |

| F. parceramosum | CBS 115695 T | JX435199 | JX435199 | JX435149 | Soil | South Africa | 28 |

| NRRL 31158 | DQ094389 | DQ236431 | DQ246916 | Human wound | USA | 28 | |

| F. petroliphilum | NRRL 32304 | DQ094402 | DQ236444 | DQ246932 | Human nail | USA | 28 |

| NRRL 32315 | DQ094412 | DQ236454 | DQ246943 | Human groin ulcer | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 43812 | EF453205 | EF453205 | EF453054 | Contact lens solution | Unknown | 28 | |

| F. pseudensiforme | CBS 241.93 | JX435198 | JX435198 | JX435148 | Human mycetoma | Suriname | 28 |

| FRC-S 1834 = CBS 125729 T | KC691584 | KC691584 | DQ247512 | Dead tree | Sri Lanka | 28 | |

| F. pseudotonkinense | CBS 143038 | LR583758 | LR583962 | LR583640 | Human cornea | Netherlands | 28 |

| F. quercicola | NRRL 22611 | DQ094326 | DQ236368 | DQ246841 | Human cornea | USA | 28 |

| NRRL 22652 T | LR583760 | LR583964 | DQ247634 | Quercus cerris | Italy | 28 | |

| NRRL 32736 | DQ094517 | DQ236559 | DQ247056 | Human eye | USA | 28 | |

| N. solani | CBS 112101 | LR583772 | LR583977 | LR583653 | Human vocal prosthesis | Belgium | 28 |

| CBS 124893 | JX435191 | JX435191 | JX435141 | Human nail | France | 28 | |

| GJS 09-1466 T | KT313633 | KT313633 | KT313611 | Solanum tuberosum | Slovenia | 28 | |

| NRRL 22779 | DQ094333 | DQ236375 | DQ246848 | Human toenail | New Zealand | 28 | |

| NRRL 31168 | DQ094395 | DQ236437 | DQ246922 | Human toe | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32492 | EU329679 | EU329679 | DQ246990 | Human | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32737 | DQ094518 | DQ236560 | DQ247057 | Human eye | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32791 | DQ094560 | DQ236602 | DQ247100 | Unknown | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32810 | DQ094577 | DQ236619 | DQ247118 | Human corneal ulcer | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 43468 | EF453093 | EF453093 | EF452941 | Human eye | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 43474 | EF453097 | EF453097 | EF452945 | Human eye | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 44896 | GU170639 | GU170639 | GU170619 | Human toenail | Italy | 28 | |

| NRRL 46598 | GU170648 | GU170648 | GU170628 | Human toenail | Italy | 28 | |

| F. stericola | CBS 142481 T | LR583779 | LR583984 | LR583658 | Compost yard debris | Germany | 28 |

| CBS 144388 | LR583780 | LR583985 | LR583659 | Greenhouse humic soil | Belgium | 28 | |

| CBS 260.54 | LR583776 | LR583981 | LR583657 | Unknown | Unknown | 28 | |

| NRRL 22239 | LR583777 | LR583982 | DQ247562 | Nematode egg | Germany | 28 | |

| F. suttonianum | CBS 124892 | JX435189 | JX435189 | JX435139 | Human nail | Gabon | 28 |

| CBS 143214 T | DQ094617 | DQ236659 | DQ247163 | Human wound | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 28000 | DQ094348 | DQ236390 | DQ246866 | Human | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32316 | DQ094413 | DQ236455 | DQ246944 | Human cornea | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 54972 | MG189940 | MG189925 | KC808197 | Equine eye | USA | 28 | |

| F. tonkinense | CBS 115.40 T | MG189941 | MG189926 | LT906672 | Musa sapientum | Vietnam | 28 |

| CBS 222.49 | LR583783 | LR583988 | LR583661 | Euphorbia fulgens | Netherlands | 28 | |

| NRRL 43811 | EF453204 | EF453204 | EF453053 | Human cornea | USA | 28 | |

| F. vasinfecta | CBS 101957 | LR583797 | LR584002 | LR583676 | Human blood, sputum and wound | Germany | 28 |

| CBS 446.93 T | LR583791 | LR583996 | LR583670 | Soil | Japan | 28 | |

| NRRL 43467 | EF453092 | EF453092 | EF452940 | Human eye | USA | 28 | |

| Fusarium sp. (AF1) | NRRL 22231 | KC691570 | KC691570 | KC691542 | Beetle on Hevea brasiliensis | Malaysia | 28 |

| NRRL 46518 | KC691571 | KC691571 | KC691543 | Beetle on Hevea brasiliensis | Malaysia | 28 | |

| NRRL 46519 | KC691572 | KC69157 | KC691544 | Beetle on Hevea brasiliensis | Malaysia | 28 | |

| Fusarium sp. (AF6) | NRRL 62590 | KC691574 | KC691574 | KC691546 | Euwallacea fornicatus on Persea americana | USA | 28 |

| NRRL 62591 | KC691573 | KC691573 | KC691545 | Euwallacea fornicatus on Persea americana | USA | 28 | |

| Fusarium sp. (AF7) | NRRL 62610 | KC691575 | KC691575 | KC691547 | Euwallacea sp. on Persea ameri- cana | Australia | 28 |

| NRRL 62611 | KC691576 | KC691576 | KC691548 | Euwallacea sp. on Persea ameri- cana | Australia | 28 | |

| Fusarium sp. (AF8) | NRRL 62585 | KC691582 | KC691582 | KC691554 | Euwallacea fornicatus on Persea americana | USA | 28 |

| NRRL62584 | KC691577 | KC691577 | KC691549 | Euwallacea fornicatus on Persea americana | USA | 28 | |

| Fusarium sp. (FSSC 12) | NRRL 22642 | DQ094329 | DQ236371 | DQ246844 | Penaceous japonicus gill | Japan | 28 |

| NRRL 25392 | EU329672 | EU329672 | DQ246861 | American lobster | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32309 | DQ094407 | DQ236449 | DQ246937 | Sea turtle | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32317 | DQ094414 | DQ236456 | DQ246945 | Treefish | USA | 28 | |

| NRRL 32821 | DQ094587 | DQ236629 | DQ247128 | Turtle egg | USA | 28 | |

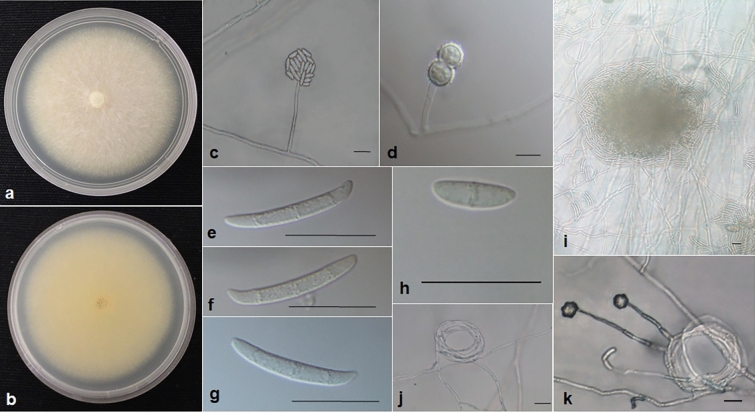

Morphological observation

Agar plugs (6 mm diameter) of the selected isolates were transferred onto fresh PDA and Carnation leaf agar (CLA) plates and incubated at 26 °C ± 1 °C for 7 and 21 days, respectively for further morphological characterisation. Morphological characterisation was based on the taxonomic keys of Leslie and Summerell, 200635. Gross macro-morphology of all isolates was examined on PDA after 7 days, this comprised (i) colony colour on top of the plate, (ii) colony colour on the reverse side (iii) colony size and (iv) texture of the hyphal growth. With a primary focus on 3 strains namely ML16006, ML16011 and ML16012.

Micro-morphological evaluation of the respective isolates was achieved by examining CLA plates in situ under the 20X or 40X objective, using a Nikon eclipse Ni compound microscope. The following characteristics were noted: (i) microconidia; shape, size, number of septa and their arrangement on phialide cells (ii) macroconidia; shape, size, number of septa and the shape of the apical and basal cells (iii) sporodachia; when present colour was noted and (iv) chlamydospores; texture of cell walls, position on hyphae and the arrangements. The length and the width of 30 micro- and macroconidia were measured for each isolate (Online Resource 1). The oval shape of the microconidia was measured by drawing a straight line from top to the bottom for the length and the width was measured across the septa or when no septa was observed, at the widest part of the cell. The length of the macroconidia was measured by drawing a straight line from the apical side of the cell to the basal side of the cell. The width was measured at the apical side of the middle septa. Conidia and chlamydospores were mounted on glass slides using water as mounting medium from fungal structures grown on carnation leaf agar36 and photographed.

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All experimental protocols were approved by a named institutional and/or licensing committee.

Results

Molecular characterisation and Phylogenetic analyses

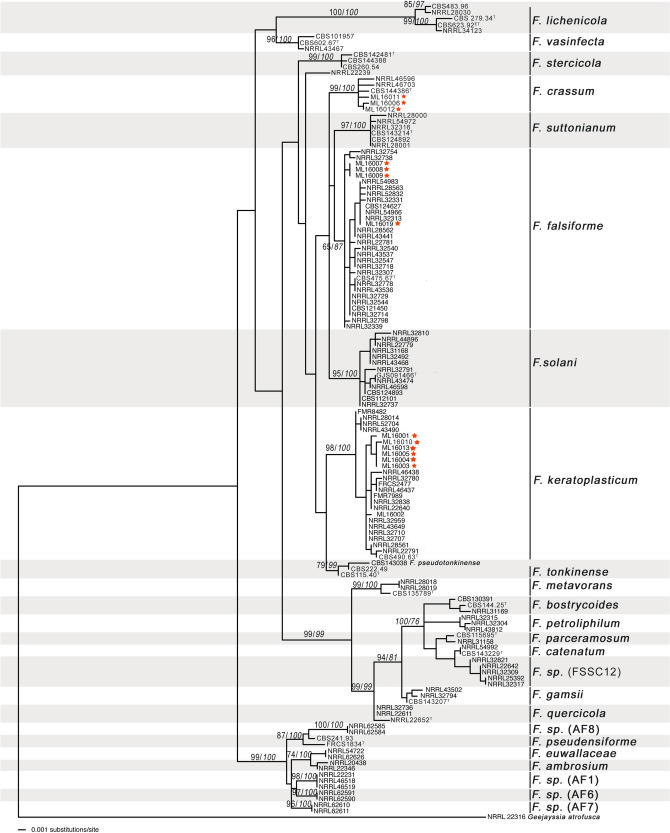

Phylogenetic analyses (Figs. 2 and 3) showed 3 (F. falciforme, F. keratoplasticum and F. crassum) distinct species. A phylogenetic tree generated from the combined dataset of LSU, ITS and tef1 gene regions, represented 3 lineages within the Fusarium solani species complex (FSSC). The maximum likelihood (ML) analysis included 135 taxa (including the outgroup). In the analyses, 14 strains isolated during this study, aligned with three species within Fusarium. Seven strains (ML16001; ML16013; ML16005; ML16004; ML16003; ML16002; ML16010) grouped with the F. keratoplasticum clade with a strong bootstrap support. Four strains (ML16007; ML16008; ML16009; ML16019) grouped within the more diverse F. falciforme clade. Another three strains (ML16006; ML16011; ML16012) grouped with F. crassum. Secondary phylogenetic analysis of the ITS and LSU gene regions, included 118 taxa (including the outgroup). These analyses confirmed the findings of primary phylogenetic analyses and showed that isolates from this study aligned with isolates that were previously associated with turtles and turtle eggs.

Figure 2.

Maximum likelihood analysis of Fusarium species isolates based on three loci, translation elongation factor 1 α (tef1), large subunit (LSU) and internal transcribed standard (ITS). Numbers within the tree represent the bootstrap values of 1 000 replicates, followed by the posterior probability (italics). Strains isolated during this study are marked with a red asterisk (*).

Figure 3.

Maximum likelihood analysis of Fusarium species isolates from other marine animals based on two loci, large subunit (LSU) and internal transcribed standard (ITS). Numbers within the tree represent the bootstrap values of 1 000 replicates, followed by the posterior probability (italics). Strains isolated during this study are marked with a red asterisk (*).

Morphological observation

Three strains expressed significant different morphological characteristics compared to other strains isolated during this study. These three strains were relatively fast growing on PDA, reaching a colony size of 70–75 mm diameter after 7 days of incubation at 26 ± 1 °C. White, flat floccose mycelium with light peach to yellow centre. White to pale light yellow on the reverse side. On CLA, incubated at 26 ± 1 °C, reaching a colony size of 80–90 mm diameter in 7 days. Microconidia were oval, ellipsoidal to sub-cylindrical in shape, with 0–1 septum, smooth and thin walled arranged in false heads at the tip of long monophialides. Average aseptate microconidia measured as follows for the three strains (n = 30 per strain); 11.5 µm (± 1.25) × 4.00 µm (± 0.5), 12.0 µm (± 1.0) × 4.0 µm (± 0.5) and 11.5 µm (± 2.0) × 4.25 µm (± 0.4). Microconidia with one septa measured as follows (n = 30 per strain); 15.0 µm (± 2.0) × 4.25 µm (± 0.5), 15.0 µm (± 1.5) × 4.0 µm (± 0.5) and 15.5 µm (± 5.0) × 4.5 µm (± 0.5). Macroconidia were fusiform in shape with the dorsal sides more curved than the ventral sides, blunt apical cells and barely notched foot cells. Macroconidia consisted of 3–4 septa and measured as follows (n = 30 per strain); 31.5 µm (± 3.0) × 5.0 µm (± 0.5), 32.0 µm (± 2.0) × 5.0 µm (± 0.5) and 30.0 µm (± 1.0) × 5.0 µm (± 0.5). Sporodochia ranged from clear to beige in colour. Chlamydospores were first observed after 14 days of incubation on CLA plates, and were globose in shape with rough walls, positioned terminally, sometimes single but mostly in pairs. Distinct hyphal coils were observed in all three strains (Fig. 4). The morphology is consistent with that described for N. crassum28 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Fusarium crassum, (a) Colony on PDA and (b) reverse side after 7 days incubation at 26 ± 1 °C. (c) areal mycelia presenting microconidia in false heads in situ, (d) Chlamydospores with rough walls in situ, (e–g) macroconidia, (h) microconidia with one septa, (i) macroconidia in situ on carnation leaf agar after 21 days incubation at 26 ± 1 °C, (j–k) hyphal coils observed in situ on carnation leaf agar. All scale bars = 20 µm.

Discussion

Fusarium infections, specifically F. keratoplasticum and F. falciforme have been reported from infected eggs and embryos of turtle species, including endangered species, at major nesting sites along the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans, as well as the Mediterranean and Caribbean Sea15,16,18,20,21,37. Management strategies to mitigate emerging fungal diseases, like Fusarium infections in turtle eggs, are influenced by identifying whether a pathogen is novel or endemic and the understanding of its ecology and distribution. A novel pathogen gains access to and infects naïve hosts as a result of migration of the pathogen or the development of novel pathogenic genotypes, in contrast endemic pathogens occur naturally in the host’s environment, but shifts in environmental conditions and/or host susceptibility influence pathogenicity37. Thus, effective management strategies to mitigate novel pathogens should aim at preventing pathogen introduction and expansion, while disease caused by endemic pathogens relies on an understanding of environmental and host factors that influence disease emergence and severity37. Phylogenetic analysis provides important information to assist in understanding the ecology, introduction and distribution of infectious agents37,38. The first aim of this study was to use multigene phylogenetic analyses to identify Fusarium strains isolated from the carapace, flippers, head, and neck area of post-hatchling loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) with fungal skin infections that stranded along the South African coastline and kept at a rehabilitation centre. The genus Fusarium was recently revised, with an attempt to standardise the taxonomy and nomenclature after a lack of formal species descriptions, Latin names and nomenclatural type specimens were identified39. Strains from this study grouped with three Fusarium species of which two species, F. keratoplasticum and F. falciforme, were previously reported to occur on animal hosts, including turtles. The third species, F. crassum is rather surprising as this species is only known from a human toenail and nematode eggs, while the origin of the type strain is unknown. Three strains (ML16011, ML16012 and ML16006) grouped with two F. crassum strains. Strain identifications were confirmed with the morphological characteristics that agreed with species descriptions published in 201928, with the one exception of chlamydospore wall texture for F. crassum. Chlamydospore walls in this study for all three F. crassum strains were smooth, while previously it has been documented with a rough texture.

Turtle egg fusariosis (STEF) is a disease that has increasingly been reported over the last decade and is considered a potential conservation threat to six out of seven species of marine turtles16,37. Skin disease and systemic infections caused by Fusarium species has been reported in adult and subadult turtles and in captive reared hatchlings5,11–15,19, but has not been reported in post-hatchling loggerhead sea turtles (C. caretta) undergoing rehabilitation. Clinical signs reported in juvenile, subadult and adult loggerhead sea turtles (C. caretta) with Fusarium infections were localised and generalised lesions of the skin and carapace, consisting of areas of discolouration and loss of shell12. Clinical signs observed in post-hatchling loggerhead sea turtles (C. caretta) in this study were similar, but generalised sloughing of scales on the limbs and head, and a soft, crumbly carapace and plastron were more common than focal lesions. Histopathology was not performed in this study to confirm the association of fungal hyphae with pathological changes in the skin, and, therefore, the role of the Fusarium isolates in the skin lesions cannot definitively be identified (as isolation of fungus could be from normal skin flora or the environment), however, fungal hyphae, often in dense mats, were seen in epidermal scrapes from affected turtles (Online Resource 2). Although Fusarium isolates (and other fungi) have been identified in the skin of healthy adult C. caretta12, a finding of numerous hyphae (hyphal mats) in skin scrapings would not be considered a normal finding in healthy turtle skin and thus it is considered likely that the fungal elements observed, and therefore the isolates identified, were associated with the observed pathology. The epidemiology of turtle pathogenic isolates F. keratoplasticum and F. falciforme in sea turtle nesting sites are not fully understood37, however, it has been suggested that tank substrates and/or biofilms forming in the water supply infrastructure or filtering systems may act as a source of infection, to traumatised and immunocompromised sea turtles11,12,40.

Investigations into the source of infection were not undertaken in this study, so it is not clear if the fungal isolates originated in the rehabilitation environment or were present in the skin on admission. Cafarchia and colleagues (2019) found increased length of stay to be a risk factor for fungal colonisation, where turtles staying in a rehabilitation centre for over 20 days were more frequently colonised with Fusarium12. Loggerhead sea turtles (C. caretta) in this study exhibited clinical signs around 20–30 days after admission and it is likely that most individuals experienced some degree of immunocompromise in the initial stages of rehabilitation. This, combined with physical skin trauma that may be present on admission may have provided a suitable environment for fungal colonisation. The second aim of study was to establish the phylogenetic relationship between F. keratoplasticum and F. falciforme strains isolated during this study and strains that were previously associated with brood failure and high mortality rates17,18. Combined sequence data of the ITS and LSU regions revealed that seven of the strains formed part of the monophyletic F. keratoplasticum clade. Strains isolated during this study showed a close phylogenetic relation with other species in this clade, consisting of species that were previously isolated from Hawksbill (E. imbricata) and green sea turtle (C. mydas) eggs shells from nesting beaches along the Pacific Ocean in Ecuador7,16. Furthermore, phylogenetic analyses of the F. falciforme group showed close resemblance to strains that were previously isolated from olive ridley sea turtle (L. olivacea), green sea turtle (C. mydas), flatback sea turtle (N. depressus) and loggerhead sea turtle (C. caretta) egg shells and C. caretta embryos on nesting beaches in Australia, Cape Verde and Ecuador, Turkey, along the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Ocean7,15–17,20,21. In addition, these strains showed a close resemblance to a strain that was previously isolated from a lesion in an adult turtle nare from the USA29. Based on the ITS and LSU gene regions, a genetic relationship exists between Fusarium species associated with turtle egg infections (also known as STEF) and Fusarium species isolated from post-hatchling loggerhead sea turtles (C. caretta) that stranded on beaches in South Africa along the Indian ocean.

Infections caused by members of this genus have been reported in numerous other aquatic animals in the past6,9,10, but for many of these, identification has been limited and mostly based on morphological characteristics. Many reports based on morphology only identified causative agents as Fusarium (F. solani), lacking further identification. Accurate identification of pathogenic Fusarium members is essential for epidemiological purposes and for assisting in management programs, however, more research is required to complete the puzzle and fully understand the ecology and distribution of these pathogens, especially amongst reptiles and aquatic animals. This is the first confirmed record of F. keratoplasticum and F. falciforme strains isolated from post-hatchling loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) from the South African coastline that were not associated with nesting sites. This is also the first record of F. crassum to be associated with loggerhead sea turtles.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Authors of this study would like to acknowledge Andre du Randt for compiling the map and the Two Oceans aquarium, South Africa for providing the samples, their co-assistance and funding.

Author contributions

MR.G.-L. – First Author, conducted all laboratory work and wrote manuscript. K.J. – Responsible for phylogeny and assisted in writing of the manuscript.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in Table 2, where the LSU and EF GenBank accession numbers for the species ‘F. crissum’, ‘F. falciforme’ and ‘F. keratoplasticum’ were omitted. Full information may be found in the correction of this Article.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

5/27/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-022-12820-2

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-06840-1.

References

- 1.Zhang N, et al. Members of the Fusarium solani species complex that cause infections in both humans and plants are common in the environment. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:2186–2190. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00120-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Donnell K, et al. Molecular Phylogenetic Diversity, Multilocus Haplotype Nomenclature, and In Vitro antifungal resistance within the Fusarium solani species complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46:2477–2490. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02371-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schroers HJ, et al. Epitypification of Fusisporium (Fusarium) solani and its assignment to a common phylogenetic species in the Fusarium solani species complex. Mycologia. 2016;108:806–819. doi: 10.3852/15-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Donnell K. Molecular phylogeny of the Nectria haematococca-Fusarium solani species complex. Mycologia. 2000;92:919–938. doi: 10.1080/00275514.2000.12061237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gleason F, Allerstorfer M, Lilje O. Newly emerging diseases of marine turtles, especially sea turtle egg fusariosis (SEFT), caused by species in the Fusarium solani complex (FSSC) Mycology. 2020;11:184–194. doi: 10.1080/21501203.2019.1710303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernando N, et al. Fatal Fusarium solani species complex infections in elasmobranchs: the first case report for black spotted stingray (Taeniura melanopsila) and a literature review. Mycoses. 2015;58:422–431. doi: 10.1111/myc.12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarmiento-Ramírez JM, et al. Global distribution of two fungal pathogens threatening endangered Sea Turtles. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e85853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayayo E, Pujol I, Guarro J. Experimental pathogenicity of four opportunist Fusarium species in a murine model. J. Med. Microbiol. 1999;48:363–366. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-4-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muhvich AG, Reimschuessel R, Lipsky MM, Bennett RO. Fusarium solani isolated from newborn bonnethead sharks, Sphyrna tiburo (L.) J. Fish Dis. 1989;12:57–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.1989.tb01291.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crow GL, Brock JA, Kaiser S. Fusarium solani fungal infection of the lateral line canal system in captive scalloped hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna lewini) in Hawaii. J. Wildl. Dis. 1995;31:562–565. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-31.4.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cabañes FJ, et al. Cutaneous hyalohyphomycosis caused by Fusarium solani in a loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta L.) J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997;35:3343–3345. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3343-3345.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cafarchia C, et al. Fusarium spp. in Loggerhead Sea Turtles (Caretta caretta): From Colonization to Infection. Vet. Pathol. 2019;57:139–146. doi: 10.1177/0300985819880347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Hartmann M, Hennequin C, Catteau S, Béatini C, Blanc V. Cas groupés d’infection à Fusarium solani chez de jeunes tortues marines Caretta caretta nées en captivité. J. Mycol. Med. 2017;28:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orós J, Delgado C, Fernández L, Jensen HE. Pulmonary hyalohyphomycosis caused by Fusarium spp in a Kemp’s ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempi): An immunohistochemical study. N. Z. Vet. J. 2004;52:150–152. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2004.36420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Candan AY, Katılmış Y, Ergin Ç. First report of Fusarium species occurrence in loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) nests and hatchling success in Iztuzu Beach, Turkey. Biologia (Bratisl). 2020 doi: 10.2478/s11756-020-00553-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarmiento-Ramirez JM, van der Voort M, Raaijmakers JM, Diéguez-Uribeondo J. Unravelling the Microbiome of eggs of the endangered Sea Turtle Eretmochelys imbricata identifies bacteria with activity against the emerging pathogen Fusarium falciforme. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e95206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarmiento-Ramírez JM, et al. Fusarium solani is responsible for mass mortalities in nests of loggerhead sea turtle, Caretta caretta, in Boavista, Cape Verde. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2010;312:192–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarmiento-Ramirez JM, Sim J, Van West P, Dieguez-Uribeondo J. Isolation of fungal pathogens from eggs of the endangered sea turtle species Chelonia mydas in Ascension Island. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom. 2017;97:661–667. doi: 10.1017/S0025315416001478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoh D, Lin Y, Liu W, Sidique S, Tsai I. Nest microbiota and pathogen abundance in sea turtle hatcheries. Fungal Ecol. 2020;47:100964. doi: 10.1016/j.funeco.2020.100964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Güçlü Ö, Bıyık H, Şahiner A. Mycoflora identified from loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) egg shells and nest sand at Fethiye beach, Turkey. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2010;4:408–413. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gambino D, et al. First data on microflora of loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) nests from the coastlines of Sicily. Biol. Open. 2020;9:bio045252. doi: 10.1242/bio.045252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bailey JB, Lamb M, Walker M, Weed C, Craven KS. Detection of potential fungal pathogens Fusarium falciforme and F. keratoplasticum in unhatched loggerhead turtle eggs using a molecular approach. Endanger. Species Res. 2018;36:111–119. doi: 10.3354/esr00895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Summerbell RC, Schroers H-J. Analysis of Phylogenetic Relationship of Cylindrocarpon lichenicola and Acremonium falciforme to the Fusarium solani Species Complex and a Review of similarities in the spectrum of opportunistic infections caused by these fungi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002;40:2866–2875. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.8.2866-2875.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nel R, Punt AE, Hughes GR. Are coastal protected areas always effective in achieving population recovery for nesting sea turtles? PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e63525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Branch, G. & Branch, M. Living Shores. (Pippa Parker, 2018).

- 26.Fuller MS, Fowles BE, Mclaughlin DJ. Isolation and pure culture study of marine phycomycetes. Mycologia. 1964;56:745–756. doi: 10.1080/00275514.1964.12018163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greeff MR, Christison KW, Macey BM. Development and preliminary evaluation of a real-time PCR assay for Halioticida noduliformans in abalone tissues. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2012;99:103–117. doi: 10.3354/dao02468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandoval-Denis M, Lombard L, Crous PW. Back to the roots: a reappraisal of Neocosmospora. Persoonia Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi. 2019;43:90–185. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2019.43.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Donnell K, Cigelnik E, Nirenberg HI. Molecular systematics and phylogeography of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex. Mycologia. 1998;90:465–493. doi: 10.1080/00275514.1998.12026933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geiser DM, et al. FUSARIUM-ID v. 1. 0: A DNA sequence database for identifying Fusarium. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2004;110:473–479. doi: 10.1023/B:EJPP.0000032386.75915.a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Donnell K, et al. Phylogenetic diversity of insecticolous fusaria inferred from multilocus DNA sequence data and their molecular identification via FUSARIUM-ID and FUSARIUM MLST. Mycologia. 2012;104:427–445. doi: 10.3852/11-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chehri K, Salleh B, Zakaria L. Morphological and phylogenetic analysis of Fusarium solani species complex in Malaysia. Microb. Ecol. 2015;69:457–471. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0494-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lanfear R, Frandsen P, Wright A, Senfeld T, Calcott B. PartionFinder 2: new methods for selecting partioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ronquist F, et al. Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model selection across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leslie JF, Summerell BA. The Fusarium Laboratory manual. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fisher NL, Burgess LW, Toussoun TA, Nelson PE. Carnation leaves as a substrate and for preserving cultures of Fusarium species. Phytopathology. 1982;72:151. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-72-151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smyth CW, et al. Unraveling the ecology and epidemiology of an emerging fungal disease, sea turtle egg fusariosis (STEF) PLOS Pathog. 2019;15:e1007682. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rachowicz LJ, et al. The novel and endemic pathogen hypotheses: Competing explanations for the origin of emerging infectious diseases of wildlife. Conserv. Biol. 2005;19:1441–1448. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00255.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lombard L, Sandoval-Denis M, Cai L, Crous PW. Changing the game: resolving systematic issues in key Fusarium species complexes. Persoonia Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi. 2019;43:i–ii. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2019.43.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Short DPG, Donnell KO, Zhang N, Juba JH, Geiser DM. Widespread occurrence of diverse human pathogenic types of the fungus Fusarium detected in plumbing drains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011;49:4264–4272. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05468-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White TJ, Burns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct identification of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sinsky JJ, White TJ, editors. PCR Protocols: a guide to methods and applications. San Diego: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sekimoto S, Hatai K, Honda D. Molecular phylogeny of an unidentified Haliphthoros-like marine oomycete and Haliphthoros milfordensis inferred from nuclear-encoded small- and large-subunit rRNA genes and mitochondrial-encoded cox2 gene. Mycoscience. 2007;48:212–221. doi: 10.1007/S10267-007-0357-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petersen AB, Rosendahl SØ. Phylogeny of the Peronosporomycetes (Oomycota) based on partial sequences of the large ribosomal subunit (LSU rDNA) Mycol. Res. 2000;104:1295–1303. doi: 10.1017/S0953756200003075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Donnell K, et al. Phylogenetic diversity and microsphere array-based genotyping of human pathogenic fusaria, including isolates from the multistate contact lens-associated U.S. keratitis outbreaks of 2005 and 2006. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:2235–2248. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00533-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Migheli Q, et al. Molecular Phylogenetic diversity of dermatologic and other human pathogenic fusarial isolates from hospitals in Northern and Central Italy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:1076–1084. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01765-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.