Abstract

Background:

Concurrent with the opioid overdose crisis there has been an increase in hospitalizations among people with opioid use disorder (OUD), with one in ten hospitalized medical or surgical patients having comorbid opioid-related diagnoses. We sought to conduct a systematic review of hospital-based interventions, their staffing composition, and their impact on outcomes for patients with OUD hospitalized for medical or surgical conditions.

Methods:

Authors searched PubMed MEDLINE, PsychINFO, and CINAHL from January 2015 through October 2020. The authors screened 463 titles and abstracts for inclusion and reviewed 96 full-text studies. Seventeen articles met inclusion criteria. Extracted were study characteristics, outcomes, and intervention components. Methodological quality was evaluated using the Methodological Quality Rating Scale.

Results:

Ten of the 17 included studies were controlled retrospective cohort studies, five were uncontrolled retrospective studies, one was a prospective quasi-experimental evaluation, and one was a secondary analysis of a completed randomized clinical trial. Intervention components and outcomes varied across studies. Outcomes included in-hospital initiation and post-discharge connection to medication for OUD, healthcare utilization, and discharge against medical advice. Results were mixed regarding the impact of existing interventions on outcomes. Most studies focused on linkage to medication for OUD during hospitalization and connection to post-discharge OUD care.

Conclusions:

Given that many individuals with OUD require hospitalization, there is a need for OUD-related interventions for this patient population. Interventions with the best evidence of efficacy facilitated connection to post-discharge OUD care and employed an Addiction Medicine Consult model.

Keywords: Opioid treatment, hospitalization, interventions, addiction

Introduction

Concurrent with the opioid overdose crisis has been an increase in hospitalizations among people with opioid use disorder (OUD), with nearly one in ten hospitalized medical or surgical patients having comorbid opioid-related diagnoses.1–3 Hospitalized patients with OUD have higher rates of discharge against medical advice (AMA), readmission, and post-discharge mortality than those without, often because of stigma endured during hospitalization and inadequate pain and withdrawal management prompting continued substance use post-hospitalization.4–7 While the prevalence of OUD has increased substantially over the last two decades,8,9 the implementation of hospital-based interventions for these patients has only recently proliferated.

Models of care for individuals hospitalized with OUD frequently focus on initiating medications for OUD (MOUD)—such as buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone—during hospitalization. This approach is logical as MOUD is safe, effective, and lifesaving, yet severely underutilized in the community.10 Barriers to MOUD initiation include stigma, stringent federal regulations on methadone, and inadequate clinical training.10–12

Many hospital interventions for patients with OUD employ an Addiction Medicine Consult (AMC) service13,14 that at a minimum includes an addiction medicine physician15,16 and often other team members like social workers, nurses, peers with lived experience, and pain medicine specialists.17–21 Other interventions focus on services like managing in-hospital withdrawal16,22 and providing psychosocial care.23 An important outcome for many interventions is post-discharge linkage to OUD care,13,16–18,24,25 though other outcomes like readmission15,18,21,25–27 and length of stay23,27 are also of interest.

The literature lacks a comparison of the specific characteristics and outcomes of existing interventions, as well as staffing composition. The purpose of this systematic review was to document existing models of care for patients with OUD hospitalized for medical or surgical conditions and describe their staffing composition and impact on outcomes. The ultimate goal is to define essential components of such models to set a standard of hospital care.

Methods

Literature search

In October 2020, we performed a literature search of peer-reviewed articles in collaboration with a biomedical librarian. Included articles were published in English between January 2015 and October 2020 and available in full text; January 2015 was selected as the initial study inclusion date to ensure the relevance of findings and to coincide with updated federal guidelines for OUD treatment that were published in 2015.28 We searched PubMed MEDLINE, PsychINFO, and CINAHL using the following search terms: ((“Inpatients” OR “hospitalization”) AND (“addiction medicine” OR “opioid use disorder” OR “opioid-related disorders” OR “opiate addiction” OR “opioid addiction” OR “opiate abuse” OR “opioid abuse”)). We identified additional studies by searching reference lists of included literature.

Data collection

We included peer-reviewed studies that were (1) retrospective or randomized controlled trials, (2) focused on adults (age ≥ 18), and (3) described an intervention for hospitalized patients with OUD. We excluded studies solely about psychiatric or detoxification units or emergency departments as this review was focused on patients hospitalized for medical or surgical conditions. Studies that included patients already receiving treatment for OUD were eligible for inclusion. We excluded clinical trials of MOUD.

Two authors (R.F. and S.V.A.) performed a title and abstract screen of all articles. If it was unclear from the abstract whether an article met the criteria, it was retained. Next, the remaining articles were screened via a full-text review for inclusion. The two authors resolved disagreements by discussion; S.V.A identified two articles not suitable for inclusion after the full-text review that R.F. had initially included. Finally, selected data were extracted from the included articles.

Data abstraction and bias assessment

We abstracted design, dates of data collection, setting, population characteristics, sample size, intervention, outcomes, and key findings from included studies (Table 1). Extracted intervention components included staffing composition, in-hospital linkage to MOUD, type and dose of MOUD, connection to post-discharge care, and statistically significant improvements in outcomes (Table 2).

Table 1.

Overview of Study Design, Patient Population, and Results of Studies Assessing Interventions for Hospitalized Patients with OUD

| Study | Design | Data | Dates of data | Setting | Population characteristics | n (treatment) | n (control) | Intervention | Primary outcomes | Key findings | MQRS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhatraju et al. (2020)13 | Controlled retrospective cohort | Electronic health record | January 1, 2018 to June 30, 2019 | Level-1 trauma center serving a 5-state region (Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho) | Hospitalized patients with OUD aged 18+ who received and ACS and were initiated on buprenorphine | 60 (with traumatic injury) | 137 (no traumatic injury) | Addiction Medicine Consult Service and initiated on buprenorphine with plans for continuation post-discharge | Outpatient buprenorphine linkage | Patients with traumatic injury more often (63%) had an OUD visit within 30 days compared to those without traumatic injury (48%*) | 10 |

| Brar et al. (2020)32 | Uncontrolled retrospective cohort | Chart review | July 2017 to May 2018 | St. Paul's Hospital in Vancouver, BC | Hospitalized patients initiated on iOAT | 4 | n/a | iOAT during hospitalization | Leaving AMA | The four patients did not leave AMA | 5 |

| Cushman et al. (2016)34 | Secondary analysis of a completed clinical trial | Subgroup analysis of only injection opiate users | August 1, 2009 to October 31, 2012 | Boston Medical Center (an urban, safety-net hospital) | Persons with injection opiate use; linkage=treatment; detoxification=control | 51 | 62 | STOP (Suboxone Transition to Opiate Program): induction, stabilization, bridge prescription, and facilitated referral to outpatient treatment | Lrequency of injection opiate use | No difference in rates of injection opiate use between STOP vs. control groups | 11 |

| Englander et al. (2019) | Controlled retrospective cohort | Oregon Medicaid claims | July 1, 2015 to September 30, 2016 | Oregon hospitals | Oregon Medicaid beneficiaries with SUD hospitalized at an Oregon hospital; IMPACT = treatment: propensity-matched controls = control | 208 | 416 | Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT): hospital-based consultation care from an interdisciplinary team of addiction medicine physicians, social workers, and peers with lived experience in recovery | Post-hospital SUD treatment engagement | IMPACT patients engaged in post-hospital SUD treatment more often (39% v. 23%*) | 10 |

| Marks et al. (201S)15 | Controlled retrospective cohort | Electronic health record | January 2016 to January 2018 | Barnes-Jewish Hospital, a 1400-bed, academic, tertiary care center in St Louis, Missouri | Hospitalized patients who received infectious disease consultation and had ICD code for opioid use disorder or injection drug use. | 38 | 87 | Addiction medicine consultation (ADC) | Clinical outcomes (receive MOUD, complete parenteral antibiotic treatment, and be discharged AMA) and readmission | ADC patients more often received MOUD (87% vs. 17%*), more often completed parenteral antibiotic treatment (79% vs. 40%*), less often were discharged AMA (16% vs. 49%*), and less often were readmitted within 90 days (hazard ratio = 0.4*) Intervention patients more often continued OAT post-discharge (42% vs. 17%); no differences in readmission | 7 |

| Nordeck et al. (201S)18 | Controlled retrospective cohort | Electronic health record | September 2012 to December 2012 | The University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC), a largely urban, tertiary care academic hospital | Hospitalized patients who received SUD consultation and were diagnosed with opioid, cocaine, and/or alcohol use disorder | 45 | 222 | University of Maryland Medical Center SUD CL service: Hospital-based SUD consultation-liaison (CL) team (including OAT initiation in the hospital for OUD patients) | Continued post-discharge opiate agonist therapy (OAT), readmission | 10 | |

| Patel et al. (2018)23 | Controlled retrospective cohort | Nationwide Inpatient Sample | Not listed | Nationwide Inpatient Sample (from approximately 1050 hospitals across the U.S.) | Inpatient admissions for patients with post-traumatic stress disorder and opioid use disorder aged 18–65 | 786 (BT) | 745 (no BT) | Behavioral therapy (BT) | Length of stay, hospital cost, and transfers to skilled nursing facilities | Patients receiving BT has longer lengths of stay by 1.27 days, greater hospital costs by $4,734*; no differences in transfers | 9 |

| Priest et al. (2020)24 | Controlled retrospective cohort | Electronic health record | 2017 | 109 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hospitals | Hospitalized in VHA hospital and aged 18+, with an OUD-related ICD-10 diagnosis within 12 months prior to or during index hospitalization | 203 | 10,766 | OAT received during hospitalization | OAT receipt during hospitalization with linkage to care post discharge | 2% of patients were initiated on OAT during hospitalization and linked to care post discharge | 11 |

| Ray et al. (2020)26 | Controlled retrospective cohort | Medical record | January 1, 2015 to March 31, 2018 | Large, community-based quaternary care hospital in Milwaukee, Wisconsin | Hospitalized adult (≥18y of age) inpatients admitted with diagnoses of both endocarditis and 1 or more opioid-related use disorders | 33 | 37 | Comprehensive intervention for inpatients with infective endocarditis and intravenous drug use. The team included behavioral health/addiction medicine, infectious disease, pain medicine, cardiothoracic surgery, pharmacy, and nursing to address the OUD while managing the infection. | Access to MOUD and readmission | Intervention patients more often initiated on MOUD (55% vs. 19%); no differences in readmission | 9 |

| Suzuki et al. (2015)22 | Uncontrolled retrospective cohort | Medical record | July 2013 and May 2014 | Academic, urban medical center in Boston, MA | Hospitalized opioid dependent patients | 47 | n/a | Initiation of buprenorphine treatment during hospitalization through psychiatry consultation service | Entry into treatment following discharge | 47% of patients successfully initiated buprenorphine treatment within 2 months of discharge | 7 |

| Suzuki (2016)33 | Uncontrolled retrospective cohort | Medical record | May 2013 and July 2015 | Academic, urban medical center in Boston, MA | Hospitalized patients with intravenous drug use related infective endocarditis | 29 | n/a | Initiation of buprenorphine treatment during hospitalization | Initiating buprenorphine during hospitalization or accepting a referral to a methadone clinic after discharge | 31% of patients initiated buprenorphine during hospitalization; 31% accepted a referral to methadone following discharge | 6 |

| Tang et al. (2020)16 | Uncontrolled retrospective cohort | Hospital pharmacy records of all patients dispensed transdermal buprenorphine | January 1, 2015 to December 29, 2016 | Academic medical center in Canada | Inpatients with opioid use disorder or opioid dependence due to chronic pain. | 23 | n/a | Initiating transdermal buprenorphine for withdrawal while bridging to sublingual therapy among hospital inpatients. | Withdrawal symptoms and treatment engagement post discharge | 65% of patients transitioned without withdrawal symptoms, while 35% experienced mild withdrawal; 83% were engaged in treatment 4 weeks post discharge | 8 |

| Thompson et al. (2019)27 | Controlled retrospective cohort | Electronic health record | November 2017 to March, 2018 | Academic health center in Chicago | Hospitalized patients with positive scores on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test and Drug Abuse Screening Test | 161 | 612 | The Substance Use Intervention Team (SUIT): a multidisciplinary team of addiction medicine specialists from emergency medicine, psychiatry, toxicology, social work, and pharmacology, that identifies patients with SUDs who are hospitalized with acute comorbidities and offer treatment. | Initiating MOUD, length of stay, 30-day readmission | 40% of patients with opioid misuse initiated MOUD; SUIT patients had a shorter length of stay (5.9 vs. 6.7 days) and lower 30-day readmission (14% vs. 16%) | 9 |

| Trowbridge et al. (2017)19 | Uncontrolled retrospective cohort | Electronic health record | July 2015 to January 2016 | Boston Medical Center (an urban, safety-net hospital) | Hospitalized patients who received an ACS. | 337 | n/a | Addiction consult service (ACS): inpatient diagnostic, management, and discharge linkage consultations | MOUD initiation and linkage to outpatient MOUD clinic | 21% of ACS patients were initiated methadone and 12% of ACS patients were initiated buprenorphine; 76% of patients initiated on methadone linked to an outpatient clinic and 49% of patients initiated on buprenorphine linked to an outpatient clinic | 9 |

| Wakeman et al. (2017)20 | Prospective quasi-experimental evaluation | Primary data collection (baseline and follow-up) | April 1, 2015, until April 1, 2016 | Urban academic medical center | Hospitalized adults who screened as high risk for having an alcohol or drug use disorder or who were clinically identified by the primary nurse as having a substance use disorder | 256 | 143 | Addiction Consult Team (ACT) | 30-day follow-up, Addiction Severity Index (ASI) rating, and number of days of abstinence | ACT patients less often had a 30-day follow up (65% vs. 70%); ACT patients had a greater reduction in ASI rating (decreased by 0.24 vs. 0.08*) and a greater increase in the number of days of abstinence (+12.7 vs. +5.6 days*) | 10 |

| Wang et al. (2020)25 | Controlled retrospective cohort | Medical record | 1/1/2018 to 10/1/2019 (11 months prior to and after the November 27, 2018) | Community hospital in New Hampshire | Inpatients with a complication of intravenous opioid use | 76 (post protocol rollout) | 71 (pre protocol rollout) | Inpatient Medication-Assisted Therapy Protocol | MOUD usage and buprenorphine linkage, leaving AMA, and readmission | Post protocol MOUD usage increased (47% vs. 75%*) and buprenorphine linkage increased (14% vs. 32%*); rates of discharge AMA nor readmission did not decrease after protocol rollout | 8 |

| Weinstein et al. (2020)21 | Controlled retrospective cohort | Electronic health record | July 2015 to July 2016 | Boston Medical Center (an urban, safety-net hospital) | Inpatients with SUD | 436 | 3,469 | INREACH (INpatient REadmission post-Addiction Consult Help) Study: a multi-disciplinary consultation team with addiction expertise that takes advantage of the reachable moment of a hospitalization to diagnose patients with SUD, counsel them about treatment options, coach and collaborate with inpatient providers, initiate evidence-based medications for addiction and bridge patients to long-term outpatient treatment | 30-day acute care utilization (any emergency department visit or re-hospitalization within 30 days of discharge) | INREACH patients had higher rates of acute care utilization (40% vs. 36%) | 8 |

Note.

Indicates statistically significant differences.

Abbreviations. OUD: opioid use disorder; iOAT: injectable opioid agonist therapy; OAT: opioid agonist therapy; AMA: against medical advice; SUD: substance use disorder; MOUD: medications for opioid use disorder.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Interventions Targeting Patients with Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) Hospitalized for Medical and Surgical Conditions.

| Study | Name of intervention | Subpopulation focus? | Staffing composition | Facilitate linkage to MOUD during hospitalization? | MOUD type and dose | Facilitate connection to post-discharge OUD care? | Intervention yields statistically significant improvement in primary outcomes? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhatraju et al. (2020)13 | Addiction Medicine Consult Service | Patients with traumatic injury | Unclear | Yes | Buprenorphine; dose not detailed | Yes | Yes—increased OUD visits within 30 days |

| Brar et al. (2020)32 | Injectable Opioid Agonist Therapy (iOAT) Initiation | No | Unclear | Yes | iOAT with hydromorphone or diacetylmorphine; average total doses of intravenous hydromorphone were 100 mg on day 1 and 200 mg on days 2–3 | No | N/a—no control group |

| Cushman et al. (2016)34 | STOP (Suboxone Transition to Opiate Program) | No | Physician and care coordinator | Yes | Buprenorphine/naloxone; 8 mg on day 1, 12 mg on day 2, and 16 mg from day 3 until hospital discharge | Yes | No |

| Englander et al. (2019) | Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT) | No | Interdisciplinary team of addiction medicine physicians, social workers, and peers with lived experience in recovery | Yes | Buprenorphine, oral naltrexone, acamprosate (for AUD), injectable naltrexone; doses not detailed | Yes | Yes—increased post-hospital substance use disorder treatment engagement |

| Marks et al. (2018)15 | Addiction Medicine Consultation (ADC) | Patients with severe infectious complications of OUD | Addiction medicine specialist | Yes | Buprenorphine, methadone, oral naltrexone, or intramuscular naltrexone; doses not detailed | No | Yes—increased MOUD initiation in hospital and completion of antibiotics; decreased discharge AMA and 90-day readmission |

| Nordeck et al. (2018)18 | SUD Consultation-Liaison Team | No | Interdisciplinary team of a psychiatrist director, addiction-boarded psychiatrists, a licensed addiction counselor, licensed social worker, two nurses, medical and psychiatric residents, and addiction medicine fellows | Yes | Buprenorphine or methadone; doses not detailed | Yes | No |

| Patel et al. (2018) | Behavioral therapy (BT) | Post-traumatic stress disorder | Unclear | No | n/a | No | Unclear if outcomes are an improvement— longer length of stay and higher costs |

| Priest et al. (2020)24 | Opioid Agonist Therapy | No | Unclear | Yes | Buprenorphine or methadone; doses not detailed | Yes | No |

| Ray et al. (2020)26 | Comprehensive intervention for inpatients with infective endocarditis and intravenous drug use | Medical or surgical patients with infective endocarditis | Behavioral health/addiction medicine, infectious disease, pain medicine, cardiothoracic surgery, pharmacy, and nursing | Yes | Buprenorphine, buprenorphine/ naloxone (Suboxone), methadone, or naltrexone; doses not detailed | No | No |

| Suzuki et al. (2015)22 | Initiation of buprenorphine | No | Psychiatry consultation service provides support to the medical/ surgical and nursing staffs | Yes | Buprenorphine; initial dose was 4 mg and if needed for pain or withdrawal, the dose was repeated every 2–4 h | Yes | N/a—no control group |

| Suzuki (2016)33 | Medication- Assisted Treatment | Patients with intravenous drug use related infective endocarditis | Addiction psychiatry consultation service provides support to the medical/surgical team | Yes | Buprenorphine or methadone; average maximal dose of buprenorphine was 15.1 mg/day (SD 4.8, range of 8–24) | Yes | N/a—no control group |

| Tang et al. (2020)16 | Addiction Medicine Consultation Service | No | Addiction medicine physician | Yes | Transdermal buprenorphine patch; mean dose at discharge was 11.9 mg | Yes | N/a—no control group |

| Thompson et al. (2019)27 | Substance Use Intervention Team (SUIT) | No | Multidisciplinary team of addiction medicine specialists, psychiatry, toxicology, social work, and pharmacology | Yes | Unclear, but minimally buprenorphine; dose not detailed | No | No |

| Trowbridge et al. (2017)19 | Addiction Consult Service (ACS) | No | Multidisciplinary team a board-certified addiction medicine physician and a nurse with addiction expertise | Yes | Buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone; doses not detailed | Yes | N/a—no control group |

| Wakeman et al. (2017)20 | Addiction Consult Team (ACT) | No | Multidisciplinary team of a psychiatrist, internists with addiction expertise, advanced practice nurses, three clinical social workers, a clinical pharmacist, recovery coach, and resource specialist | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes—reduction in Addiction Severity Index rating and increased number of days of abstinence |

| Wang et al. (2020)25 | Inpatient Medication-Assisted Therapy Protocol | No | Addiction medicine consultation group (membership unclear) | Yes | Buprenorphine/naloxone; default dose was 2/0.5 mg every 2 h as needed for a Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale score of >12, up to 8 mg in the first 24 h | Yes | Yes—increased MOUD usage and buprenorphine linkage |

| Weinstein et al. (2020)21 | INREACH (INpatient REadmission post-Addiction Consult Help) | No | Multidisciplinary team of physicians and one nurse | Yes | Buprenorphine, methadone, naltrexone, acamprosate (for AUD), disulfiram (for AUD), or topiramate (for AUD); doses not detailed | Yes | No |

Abbreviations. OUD: opioid use disorder; AMA: against medical advice; SUD: substance use disorder; MOUD: medications for opioid use disorder; AUD: alcohol use disorder.

Two authors (R.F. and S.V.A.) independently applied the Methodological Quality Rating Scale (MQRS). The MQRS assesses 13 methodological domains and has been used in previous systematic reviews about substance use disorder treatment.29–31 MQRS scores can range from 0 (low quality) to 16 (high quality). Out of the 221 opportunities (17 articles across 13 rating categories) for disagreement on MQRS scoring, ten ratings warranted discussion and resolution by consensus. Detailed notes about discrepancies were kept. Given the variation in measured outcomes, a meta-analysis was not attempted.

Results

Search results

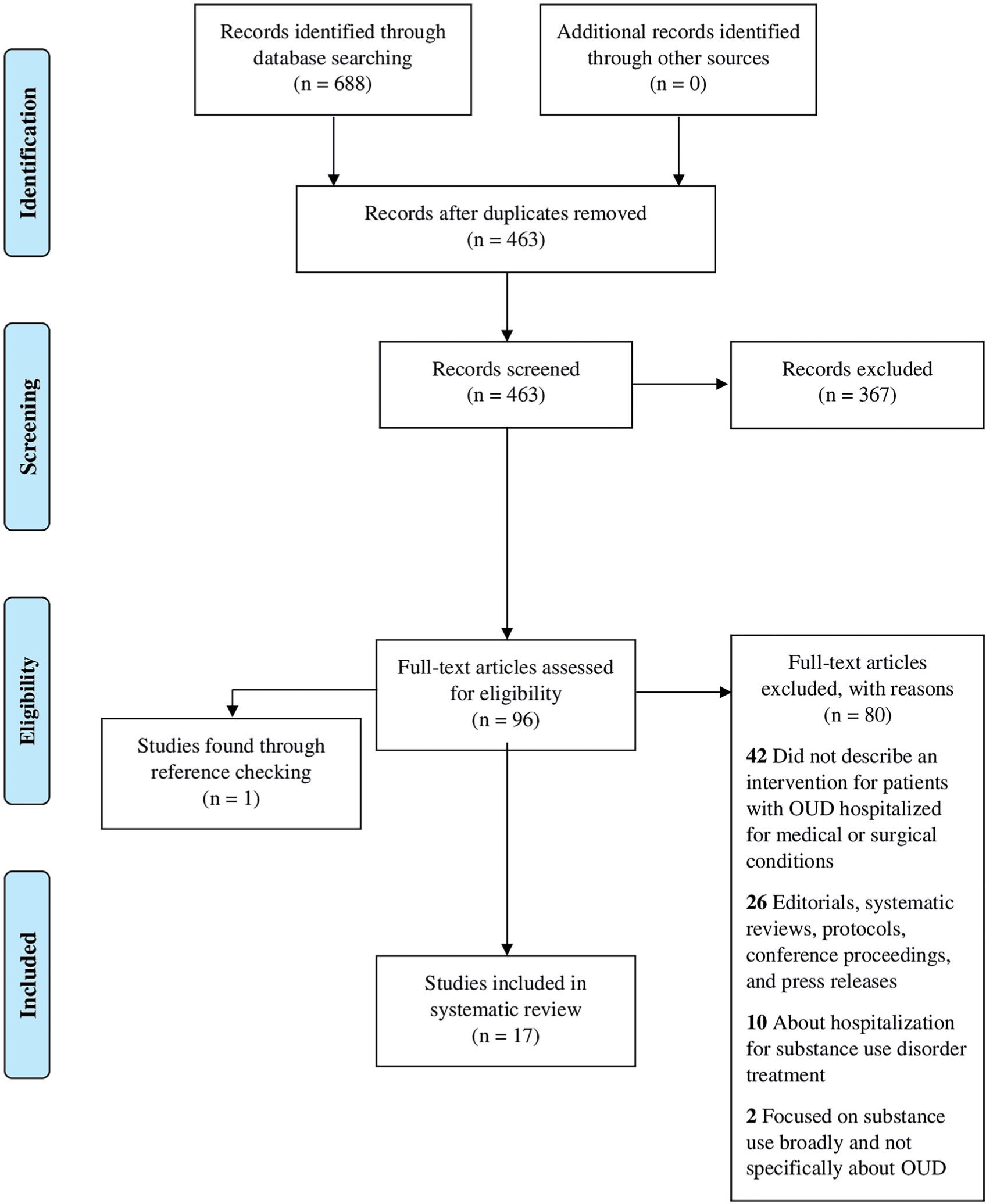

Our search yielded 688 articles. After removing duplicates, 463 articles remained. We identified 96 articles for full-text review after screening titles and abstracts. We identified 17 studies for inclusion (Figure 1). Sixteen studies were identified through the primary search; one was identified through reviewing references.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Study designs and outcomes

Table 1 provides an overview of the 17 included studies. Ten were controlled retrospective cohort studies, five were uncontrolled (pre-post) retrospective studies,16,19,22,32,33 one was a prospective quasi-experimental evaluation,20 and one was a secondary analysis of a completed randomized clinical trial.34 Sample sizes varied from four patients in a study employing chart review32 to 10,969 patients in a study using electronic health records in the Veterans Health Administration.24

Among included studies, the most commonly evaluated outcomes were post-discharge linkage to care (11 studies),13,16–20,22,24–26,33 readmission (6 studies),15,18,21,25–27 and in-hospital MOUD initiation (6 studies).15,19,24,25,27,33 Regarding outcome measures for the 12 studies with a control group, most studies identified outcomes through chart review13,15,18,25,27 or diagnosis codes,17,21,23,24,26 while others used research staff20 including through timeline followback.34 Wang and colleagues defined linkage to care as when a provider discharged a patient with a buprenorphine prescription and a scheduled outpatient buprenorphine appointment,25 while others defined it as post-hospital OUD treatment engagement18,24,34 within 30,13,20 34,17 or 90 days.20 Readmission was defined as 30-,18,21,25,27 60-,18 90-,15,18,25,26 and 180-day all-cause readmission,18 90-day readmission for endocarditis,26 and 30- and 90-day opioid-related readmission.25 MOUD initiation was classified as receiving buprenorphine,15,19,24,25,27,33 methadone,15,19,24,25,33 or naltrexone15,19 during hospitalization. One study without a control group addressed managing withdrawal as an outcome.16

Intervention characteristics

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of interventions. Key components included subpopulation focus, staffing composition, linkage to MOUD during hospitalization, connection to post-discharge OUD care, and statistically significant improvement in primary outcomes. Three studies focused on patients with infectious diseases like endocarditis,15,26,33 one on those with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),23 and on those with a traumatic injury.13 Ray and colleagues focused only on patients admitted to cardiovascular surgery for treatment of endocarditis.26

Regarding staff composition, six interventions employed interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary teams that variously included peers with lived experience, addiction counselors, social workers, clinical pharmacists, registered nurses, advanced practice nurses, psychiatrists, and internal medicine as well as addiction medicine physicians. Other studies used physicians and care coordinators;34 various behavioral health, addiction, and medical specialists;26 addiction medicine physicians;15,16 an addiction medicine consultation group;25 and a psychiatry consultation service.22,33 Four studies did not detail the staff utilized.

Intervention components generally included linkage to MOUD during hospitalization and connection to post-discharge OUD care. Twelve studies focused on in-hospital initiation of as well as post-discharge linkage to OUD care, while four studies focused only on in-hospital initiation of MOUD.15,26,27,32 Patel et al.’s study offering behavioral therapy to hospitalized patients with OUD and co-occurring PTSD was the only one to not offer on in-hospital or post-discharge linkage to MOUD.23 Of the studies that focused on linkage to MOUD, all except two23,32 focused on initiating buprenorphine; four studies also offered methadone or naltrexone.

The 12 studies with a control group utilized various intervention approaches (Table 1), with most (5/12) employing an AMC service14 that leveraged a multi- or inter-disciplinary team;13,17,18,20,21 one study that used an AMC service only used an addiction medicine specialist.15 Three other studies employed teams to provide comprehensive resources related to addiction, behavioral health, and pain.26,27,34 The remaining three studies’ interventions focused on initiating MOUD during hospitalization24,25 or behavioral therapy.23

Outcomes

Of the 12 studies with a control group, six did not find statistically significant improvements in selected outcomes. Three studies failed to find a significant reduction in rates of readmission18,26,27 and Thompson and colleagues found no statistically significant difference in length of stay.27 Ray and colleagues found no statistically significant difference in the rate of in-hospital initiation of MOUD,26 Nordeck and colleagues found no significant improvement in post-discharge connection to OUD treatment,18 and Cushman et al. found no difference in rates of injection opioid use.34 Weinstein and colleagues found higher rates of acute care utilization (40% vs. 36%)21 in patients who received the intervention, and Priest and colleagues found that only 2% of patients were initiated on MOUD during hospitalization and linked to care post-discharge.

Five of the 12 studies with a control group found significant improvements in designated outcomes. Marks and colleagues found increased completion rates of antibiotics for endocarditis (79% vs. 40%) and decreased rates of AMA discharge (16% vs. 49%) and 90-day readmission (hazard ratio = 0.4).15 Wakeman and colleagues found a reduction in Addiction Severity Index rating (decreased by 0.24 vs. 0.08) and increased number of days of abstinence (+12.7 vs. +5.6 days), but also less frequent 30-day follow-up care for OUD (65% vs. 70%).20 Three studies found increased rates of post-discharge connection to OUD care and two studies found increased rates of MOUD initiation during hospitalization.15,25 The five studies without control groups focused on reducing discharge AMA, initiating19,22,33 and sustaining16,19 MOUD, and minimizing withdrawal symptoms and had positive findings. Another study found longer lengths of stay and higher costs among patients receiving the intervention.23

Methodological quality

The methodological quality of each included study was assessed using the MQRS (scores in Table 1; methodological details in Table 3). Most studies were quasi-experimental (64.7%) and conducted at a single site (82.4%). All studies’ procedures were described in sufficient detail. Dosage was scored as a 1 if all aspects of the intervention were enumerated and discussed. Appendix A shows the appraisal for each study. The MQRS scores ranged from 5 to 1118,24,34 (mean = 8.8; SD = 1.7).

Table 3.

Methodological Quality Characteristics of Studies Based on the Methodological Quality Rating Scale (MQRS) (n = 17).

| Methodology attributes (points) | n (%) | IRR |

|---|---|---|

| A. Study design | 1.00 | |

| Single group pretest posttest (1) | 5 (29.4) | |

| Quasi-experimental (nonequivalent control) (2) | 11 (64.7) | |

| Randomization with control group (3) | 1 (5.9) | |

| B. Replicability | 1.00 | |

| Procedures contain insufficient detail (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Procedures contain sufficient detail (1) | 17 (100) | |

| C. Baseline | 0.94 | |

| No baseline scores, characteristics, or measures reported (0) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Baseline scores, characteristics, or measures reported (1) | 16 (94.1) | |

| D. Quality control | 1.00 | |

| No standardization specified (0) | 3 (17.6) | |

| Intervention standardization by manual, procedures, specific training, etc. (1) | 14 (82.4) | |

| E. Follow-up length | 0.94 | |

| Less than 6 months (0) | 14 (82.4) | |

| 6–11 months (1) | 3 (17.6) | |

| 12 months or longer (2) | 0 (0) | |

| F. Dosage No discussion of dosage or % of treatment received (0) | 5 (29.4) | 1.00 |

| Dosage, % treatment enumerated and accounted for (1) | 12 (70.6) | |

| G. Collaterals | 1.00 | |

| No collateral verification (0) | 17 (100) | |

| Collaterals interviewed (1) | 0 (0) | |

| H. Objective verification | 1.00 | |

| No objective verification (0) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Verification of records (paper records, blood, materials, etc.) (1) | 16 (94.1) | |

| I. Dropouts / attrition | 0.94 | |

| Dropouts neither discussed nor accounted for (0) | 6 (35.3) | |

| Dropouts enumerated and discussed (1) | 11 (64.7) | |

| J. Statistical power | 0.82 | |

| Inadequate power due to sample size/dropouts (0) | 6 (35.3) | |

| Adequate power with adequate sample size (1) | 11 (64.7) | |

| K. Independent | 0.88 | |

| Follow-up nonblind, unspecified (0) | 17 (100) | |

| Follow-up of interventions treatment-blind (1) | 0 (0) | |

| L. Analyses | 0.88 | |

| No statistical analyses or clearly inappropriate analyses (0) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Appropriate statistical analyses (group differences, characteristics comparable) (1) | 16 (94.1) | |

| M. Multisite | 1.00 | |

| Single site (0) | 14 (82.4) | |

| Parallel replications at two or more sites (1) | 3 (17.6) |

Note:

Dosage was scored as a “1” if all aspects of the intervention were enumerated and discussed.

Abbreviation. IRR: interrater reliability.

Discussion

This review assessed published evaluations of interventions for patients with OUD hospitalized for medical or surgical conditions, as well as common components of these approaches and the impact of these interventions on outcomes. We found that most interventions (14/17) were delivered within a single healthcare system and that these interventions consistently focused on initiating MOUD during hospitalization (except one focused on behavioral therapy23) though such initiation was inconsistently evaluated as an outcome. Many interventions (12/17) also connected patients to post-discharge OUD care. Some studies (5/17) focused on subpopulations of patients with OUD, including those with infectious diseases, PTSD, and traumatic injury. While this review included articles published between January 2015 and October 2020, seven of the 17 included studies were published in 2020 revealing the recent proliferation of research interest in hospital care for this population, likely rooted in the ongoing yet urgent need for effective interventions.

The most commonly evaluated outcome across included studies was post-discharge linkage to care.13,16–20,22,24–26,33 Readmission15,18,21,25–27 and in-hospital MOUD initiation15,19,24,25,27,33 were also commonly evaluated outcomes. Given the focus of interventions on providing evidence-based OUD care like MOUD,11 examining in-hospital and post-discharge linkage to OUD treatment as outcomes seems appropriate. Readmission as an outcome seems less responsive to interventions, which may explain the mixed readmission findings.

Of the five studies that detected significant improvements in outcomes (i.e., post-discharge connection to OUD treatment, initiation of MOUD, readmission, antibiotic completion, AMA discharges,), four employed an AMC service13,15,17,20 and one used an addiction medicine consultation group to assist with a buprenorphine protocol rollout,25 suggesting the importance of this model in improving the outcomes of hospitalized patients with OUD. Despite the positive impact on outcomes, consistent with existing evidence,14 we found variability in the components of AMC services. For example, one included study classified consultation with an addiction medicine physician as constituting an AMC service15 while another included study’s AMC service included consultation from a multidisciplinary team of psychiatrists, internists, advanced practice nurses, social workers, pharmacists, recovery coaches, and resource specialists.20

Our findings suggest that successful interventions may include physicians with addiction medicine expertise, social workers, peers in recovery, psychiatrists, advanced practice nurses, pharmacists, recovery coaches, and resource specialists. The only staff in all four of the studies that found statistically significant improvements in outcomes and delineated their staffing model, however, were physicians with addiction medicine expertise,15,17,20,25 highlighting the importance of these providers in improving outcomes for patients with OUD. The only study that leveraged the expertise of peers in recovery found a significant increase in post-hospital treatment engagement, suggesting the importance of this personnel.17 Weinstein and colleagues found that patients in the intervention group had higher rates of acute care utilization (40% vs. 36%).21 This is the only included study that employed an AMC service but did not find definitively improved outcomes, even though the service consisted of a multi-disciplinary consultation team with addiction expertise.21 While greater utilization of acute care is not generally regarded as an improved outcome, engagement with any healthcare service may be a positive outcome for some individuals with OUD as 40% of people who use drugs avoid healthcare due to anticipated mistreatment.35 Primary and preventative care settings should feel accessible to all people with OUD so that care can most often be delivered in such settings, but until this is a reality, we must reevaluate what are “desirable” outcomes for these patients. Having a positive acute care experience may make people with OUD more likely to engage in post-discharge treatment for OUD. These findings highlight the care that must be taken to ensure that models are improving outcomes relevant to patients with OUD.

Some interventions may not detect significant improvements in outcomes due to the focus on statistical significance. For example, Ray and colleagues found that patients with infective endocarditis and intravenous drug use receiving care from a multidisciplinary team were more often initiated on MOUD (55% vs. 19%), though this finding was not statistically significant.26 Additionally, variation in outcome definition and measurement may explain some inconsistent findings. Nordeck et al. conducted a chart review to identify if patients kept their post-discharge OUD treatment appointment and found no significant improvement in post-discharge linkage,18 while Englander et al. identified two or more claims for OUD care and found increased engagement in post-discharge care.17

Most included studies utilized a retrospective cohort design providing important but limited observational information about the efficacy of the interventions introduced. Clearly, the utilization of prospective experimental designs would provide stronger evidence for causal efficacy. The definition of a control group in such experimental evaluations, however, would need to be carefully considered as treatment-as-usual typically represents no treatment, which brings ethical implications. Treating OUD in the acute care setting may be particularly suitable for more pragmatic clinical trial research designs, reflecting comparative effectiveness research approaches which minimize control over the clinical environment in which interventions are delivered to maximize external validity. Further, qualitative research approaches examining patient perspectives and experiences are important to design interventions that are feasible and acceptable to people with OUD.

Compared to Theissen-Toupal and colleagues’ review, we found few studies evaluating interventions beyond initiating and sustaining MOUD, such as managing withdrawal, employing psychosocial interventions, and utilizing harm-reduction strategies,36 avenues that hold promise and warrant further investigation. Only three studies addressed discharge AMA, an outcome of particular relevance for hospitalized patients with OUD given their high rates of self-discharge.7,37 These patients may discharge AMA because of untreated pain, unmanaged withdrawal, or stigma,7 and these unfortunate occurrences may be less likely if patients receive OUD-specific care. One study found that the four patients included in the chart review who received injectable opioid agonist therapy did not leave AMA, another found that patients with severe infectious complications of OUD who received infectious disease consultations were significantly less likely to leave AMA (16% vs. 49%; P-value <0.001),15 while a third study found that rates of AMA discharge did not improve among hospitalized patients with complications of intravenous opioid use after the rollout of an intervention.25

To our knowledge, this review is the first to systematically document components, staffing models, and outcomes of existing interventions—a crucial step in defining a standard of hospital care of patients with OUD. Several limitations are noted. While the focus of the study was medical and surgical hospital settings, one study did not specify the setting but met inclusion and exclusion criteria.23 Additionally, we were unable to perform a meta-analysis given the variation in the outcomes of included studies. While the interventions discussed in this study offer solutions to a complex problem, not all interventions may be feasible or may be limited by hospital policies. For example, a Canadian study uses the injectable opioid receptor agonist hydromorphone,32 but providing this medication in the United States would be challenging given current policies prohibiting its first-line use.38

While not an explicit part of this review, we noticed that none of the reviewed studies addressed the importance of OUD interventions in reducing racial disparities. This question is important given that the number of OUD-related deaths is increasing rapidly among Black Americans39 and that Black individuals seeking hospital care following an opioid overdose are half as likely to be linked to post-discharge OUD care.40 Any intervention, and especially interventions targeted at a population where known disparities exist,41 must actively seek to mitigate inequities. Future work should examine how racially equitable the use and efficacy of hospital interventions for patients with OUD is, findings that may prompt the refinement of such interventions before or once they are implemented in clinical settings.

Conclusions

This review of 17 studies is the first to systematically document the components and outcomes of existing interventions for hospitalized patients with OUD. There is a clear need for interventions targeted at this population, though we found mixed results regarding the impact of existing interventions on outcomes. Interventions with the best evidence of efficacy often employed an AMC service that facilitated connection to post-discharge OUD care and included addiction medicine physicians15,17,20,25 as part of a team. Implementation strategies may represent an untapped lever for scaling models of care for these patients while ensuring that interventions actively mitigate existing racial disparities in access to care. Findings from this review inform the definition of essential components of interventions to set a standard for the hospital care of patients with OUD.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Richard James, a biomedical librarian at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, for his expertise in conducting the literature search for this review.

Disclosure statement

None of the authors have any disclosures to report. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Funding

Dr. French’s predoctoral fellowship was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research under Grant [T32NR007104]. Dr. Aronowitz is supported the National Clinician Scholars Program. Dr. Brooks Carthon is supported by the National Institute of Minority Health & Health Disparities under Grant [R01MD011518]. Dr. Schmidt is supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse under Grants [R01DA037897] and [R21DA045792]. Dr. Compton is supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research under Grant [R21NR019047]; and by the National Institute on Drug Abuse under Grant [R21DA046346].

Appendix A

Table A1.

Appraisal of the Methodological Quality of Included Studies using the Methodological Quality Rating Scale (MQRS) following Consensus.

| Study | A. Study design | B. Replicability | C. Baseline | D. Quality control | E. Follow-up length | F. Dosage | G. Collaterals | H. Objective verification | I. Dropouts/attrition | J. Statistical power | K. Independent | L. Analyses | M. Multisite | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bhatraju et al. (2020)13 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Brar et al. (2020)32 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Cushman et al. (2016)34 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Englander et al. (2019)17 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Marks et al. (2019)15 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Nordeck et al. (2018)18 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Patel et al. (2018)23 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Priest et al. (2020)24 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Suzuki (2016)33 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Suzuki et al. (2015)22 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Tang et al. (2020)16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Thompson et al. (2019)27 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Trowbridge et al. (2017)19 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Wang et al. (2020)25 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Weinstein et al. (2020)21 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Ray et al. (2020)26 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Wakeman et al. (2017)20 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||

References

- [1].Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, Barrett ML, et al. Opioid-related inpatient stays and emergency department visits by state, 2009–2014: statistical brief# 219. 2017.

- [2].Holt SR, Ramos J, Harma MA, et al. Prevalence of unhealthy substance use on teaching and hospitalist medical services: implications for education. Am J Addict. 2012;21(2):111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].McNeely J, Gourevitch MN, Paone D, et al. Estimating the prevalence of illicit opioid use in New York City using multiple data sources. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Blanchard J, Weiss AJ, Barrett ML, et al. Readmissions following inpatient treatment for opioid-related conditions. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54(3):473–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dewan KC, Dewan KS, Idrees JJ, et al. Trends and outcomes of cardiovascular surgery in patients with opioid use disorders. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(3):232–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, et al. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(3):137–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Simon R, Snow R, Wakeman S. Understanding why patients with substance use disorders leave the hospital against medical advice: a qualitative study. Subst Abus. 2020;41(4):519–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Strang J, Volkow ND, Degenhardt L, et al. Opioid use disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Volkow ND. Medications for opioid use disorder: bridging the gap in care. The Lancet. 2018;391(10118):285–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Allen B, Nolan ML, Paone D. Underutilization of medications to treat opioid use disorder: what role does stigma play? Subst Abus. 2019;40(4):459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Madras BK, Ahmad NJ, Wen J, Sharfstein J. Improving access to evidence-based medical treatment for opioid use disorder: strategies to address key barriers within the treatment system. NAM Perspectives. 2020. 10.31478/202004b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Goedel WC, Shapiro A, Cerdá M, et al. Association of racial/ethnic segregation with treatment capacity for opioid use disorder in counties in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e203711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bhatraju EP, Ludwig-Barron N, Takagi-Stewart J, et al. Successful engagement in buprenorphine treatment among hospitalized patients with opioid use disorder and trauma. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;215:108253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Priest KC, McCarty D. The role of the hospital in the 21st century opioid overdose epidemic: the Addiction Medicine Consult Service. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Marks LR, Munigala S, Warren DK, et al. Addiction medicine consultations reduce readmission rates for patients with serious infections from opioid use disorder. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(11):1935–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tang VM, Lam-Shang-Leen J, Brothers TD, et al. Case series: limited opioid withdrawal with use of transdermal buprenorphine to bridge to sublingual buprenorphine in hospitalized patients. Am J Addict. 2020;29(1):73–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Englander H, Dobbertin K, Lind BK, et al. Inpatient addiction medicine consultation and post-hospital substance use disorder treatment engagement: a propensity-matched analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(12):2796–2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nordeck CD, Welsh C, Schwartz RP, et al. Rehospitalization and substance use disorder (SUD) treatment entry among patients seen by a hospital SUD consultation-liaison service. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;186:23–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Trowbridge P, Weinstein ZM, Kerensky T, et al. Addiction consultation services – Linking hospitalized patients to outpatient addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;79:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wakeman SE, Metlay JP, Chang Y, Herman GE, Rigotti NA. Inpatient addiction consultation for hospitalized patients increases post-discharge abstinence and reduces addiction severity. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(8):909–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Weinstein ZM, Cheng DM, D’Amico MJ, et al. Inpatient addiction consultation and post-discharge 30-day acute care utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;213:108081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Suzuki J, DeVido J, Kalra I, et al. Initiating buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized patients with opioid dependence: a case series. Am J Addict. 2015;24(1):10–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Patel RS, Manikkara G, Patel P, Talukdar J, Mansuri Z. Importance of behavioral therapy in patients hospitalized for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with opioid use disorder. Behav Sci. 2018;8(8):73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Priest KC, Lovejoy TI, Englander H, Shull S, McCarty D. Opioid agonist therapy during hospitalization within the veterans health administration: a pragmatic retrospective cohort analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(8):2365–2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wang SJ, Wade E, Towle J, et al. Effect of inpatient medication-assisted therapy on against-medical-advice discharge and readmission rates. Am J Med. 2020;133(11):1343–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ray V, Waite MR, Spexarth FC, et al. Addiction management in hospitalized patients with intravenous drug use-associated infective endocarditis. Psychosomatics. 2020;61(6):678–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Thompson HM, Hill K, Jadhav R, et al. The substance use intervention team: a preliminary analysis of a population-level strategy to address the opioid crisis at an academic health center. J Addict Med. 2019;13(6):460–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration. Federal guidelines for opioid treatment programs. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Apodaca TR, Miller WR. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of bibliotherapy for alcohol problems. J Clin Psychol. 2003;59(3):289–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Vaughn MG, Howard MO. Adolescent substance abuse treatment: a synthesis of controlled evaluations. Res Social Work Pract. 2004;14(5):325–335. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Li W, Howard MO, Garland EL, McGovern P, Lazar M. Mindfulness treatment for substance misuse: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;75:62–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Brar R, Fairbairn N, Colizza K, Ryan A, Nolan S. Hospital initiated injectable opioid agonist therapy for the treatment of severe opioid use disorder: a case series. J Addict Med. 2021;15(2):163–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Suzuki J. Medication-assisted treatment for hospitalized patients with intravenous-drug-use related infective endocarditis. Am J Addict. 2016;25(3):191–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Cushman PA, Liebschutz JM, Anderson BJ, Moreau MR, Stein MD. Buprenorphine initiation and linkage to outpatient buprenorphine do not reduce frequency of injection opiate use following hospitalization. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;68:68–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Meyerson BE, Russell DM, Kichler M, et al. I don’t even want to go to the doctor when I get sick now: healthcare experiences and discrimination reported by people who use drugs, Arizona 2019. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;93:103112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Theisen-Toupal J, Ronan MV, Moore A, Rosenthal ES. Inpatient management of opioid use disorder: a review for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(5):369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Suzuki J, Robinson D, Mosquera M, et al. Impact of medications for opioid use disorder on discharge against medical advice among people who inject drugs hospitalized for infective endocarditis. Am J Addict. 2020;29(2):155–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hospira. Important drug information. Hospira Web site. https://www.fda.gov/media/115316/download. Published August 2018. Accessed June 7, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2017. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 2019;67(51–52):1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kilaru AS, Xiong A, Lowenstein M, et al. Incidence of treatment for opioid use disorder following nonfatal overdose in commercially insured patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e205852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Krawczyk N, Feder KA, Fingerhood MI, Saloner B. Racial and ethnic differences in opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder in a US national sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;178:512–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]