Abstract

Background

The efficacy of liraglutide to treat type 2 diabetic nephropathy (T2DN) remains controversial. Thus, we conducted this meta-analysis to systematically evaluate the clinical effect of liraglutide on T2DN patients.

Methods

Eight databases (PubMed, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang database, China Science and Technology Journal Database, and China Biology Medicine Database (CBM)) were searched for published articles to evaluate the clinical efficacy of liraglutide in subjects with T2DN. The Revman 5.3 and Stata 13 software were used for analyses and plotting.

Results

A total of 18 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 1580 diabetic nephropathy patients were screened. We found that the levels of UACR, Scr, Cysc were lower in the experimental group of T2DN patients treated with liraglutide than in the control group intervened without liraglutide. Liraglutide also reduced the levels of blood glucose (including FBG, PBG, and HbA1c), body mass index (BMI), and anti-inflammatory indicators (TNF–α, IL-6). However, there was no significant difference in BUN and eGFR between the experimental group and the control group.

Conclusions

Liraglutide reduced the levels of Blood Glucose, BMI, renal outcome indicators, and serum inflammatory factors of patients with T2DN, suggesting the beneficial effects of liraglutide on renal function.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), Liraglutide (Lira), Diabetic nephropathy, Meta-analysis

Background

Although primary prevention for risk factors and early intervention in the levels of blood glucose effectively reduce the rates of incidence and renal failure caused by type 2 diabetic nephropathy (T2DN), T2DN is still one of the most serious and prevalent microvascular complications of diabetes mellitus with type 2 (T2DM) worldwide [1]. The number of adult diabetes patients in the world obtained from the report of the international diabetes federation is about 536.6 million (approximately 10.5% of the world population) by the end of 2021, which is expected to reach 783.2 million (12.2%) in 2045 [2]. Unfortunately, more than 40% of individuals with diabetes mellitus will develop kidney disease over time [3]. The morbidity of T2DM is exceedingly high, and an increasing number of T2DN cases are relatively detected. In fact, T2DN has become the major cause leading to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [4].

For a long time in the past, a wide variety of drugs such as insulin, metformin, sulfonylurea, meglitinide, and thiazolidinedione were utilized to control the level of blood glucose and reduce the risk of diabetic complications [5]. However, substantially adverse effects associated with these traditional drugs including hypoglycemia and weight gain, and drugs-resistance lead to the limitation of drug application. Fortunately, a new kind of compound glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) have been widely used in treatments of diabetes and its associated complications in recent years. Liraglutide, a common GLP1-RA, shows a good curative effect in reducing weight and controlling blood glucose. Notably, liraglutide is likely to have a considerable renoprotective effect [6, 7].

Some previous studies have shown that liraglutide can reduce urine protein and has a renal protective effect [8, 9]. But some others did not find the same results [10]. In conclusion, the efficacy of liraglutide to treat T2DN remains controversial. Thus, this meta-analysis aims to estimate the efficacy of liraglutide in the treatment of T2DN and which related indicators may be affected.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Health-related electronic databases including PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, CNKI, Wanfang Database, VIP, and CBM Database, were searched to identify eligible studies to July 2021 inclusive, using the following Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) AND/OR entry words in any field, “diabetic nephropathy”, “diabetic nephropathies”, “proteinuria”, “diabetic kidney disease”, “albuminuria”, “liraglutide”, “diabetic glomerulosclerosis”, “urinary albumin excretion”, “type 2 diabetes mellitus”. Correspondingly, the search strategy was slightly adjusted according to the range of the search results in different databases. In addition, the related research was limited to RCT published in English or Chinese language. To avoid missing other relevant articles, we also manually retrieved the references of every article and relevant reviews to investigate any additional eligible studies.

Inclusion criteria

Study inclusion criteria were as follows:

RCTs (randomized controlled trials) were used in these research;

Studies including patients with type 2 diabetes with nephropathy;

Patients who were on a strict diet and exercise regimen were included in the studies, some were prescribed with anti-hypertensive medications or other anti-hyperglycemic medications (control group), while others were prescribed with liraglutide (experimental group);

Studies that reported renal function outcomes, including estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR); urine albumin creatinine ratio (UACR); Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN); serum creatinine (Scr); serum cystatin C (CysC);

Data extraction

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, all screened studies were independently identified by two reviewers (NM and FS). Notably, any discrepancy between the two reviewers was resolved by discussion or the third reviewer (FWX). Then, the selected full-text articles were performed eligibility evaluation to determine whether they were suitable for the current meta-analysis. Furthermore, the information extracted from each study included:

the basic information, including the initial author’s name, the year of publication, the type of study, and the total number of patients, gender composition, the average age of patients in the experimental group and the control group, the therapeutic approaches, course of treatment.

the evaluation index of the outcome included: hypoglycemic related indicators (FBG, PBG, HbA1c) and BMI; renal function(UACR, Scr, CysC, BUN, eGFR); anti-inflammatory indicators (IL-6, TNF-α).

Assessment of quality of evidence

The quality evaluation for every selected article was independently assessed by two authors (MN and SF) using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of bias [11]. In general, the evaluation contents included the quality appraisal of the literature comprised random sequence generation (Selection Bias), allocation concealment (Selection Bias), blinding of participants and personnel (Performance Bias), blinding of outcome assessment (Detection Bias), incomplete outcome data (Attrition Bias), and selective reporting (Reporting Bias), and other sources of bias. Similarly, disagreements for the risk of bias by two investigators were resolved by discussing or the third reviewer. Markedly, articles that had clearly defined details and met or surpassed the quality criteria were defined as low-risk; if not, they were deemed high-risk. Ambiguous articles concerning quality criteria remained deemed to be of unclear risk. Notably, the quality of trials was evaluated using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for evaluating the risk of bias in randomized controlled trials; quality was not used as a standard for the selection of trials, however merely for descriptive purposes.

Data analysis

Review Manager Software 5.3.5 (RevMan 5.3.5) and Stata 13 Software were used for all data analyses and plotting. The Chi-Squared-based Q-tests and I-squared (I2) statistics were utilized to evaluate the statistical heterogeneity of the included studies [12]. The value of I2 test greater than 50% and p ≤ 0.05 were regarded as substantial heterogeneity. Then DerSimonian-Laird random-effect model [13] was performed, otherwise, a Mantel-Haenszel fixed-effect model [14] was conducted. Subsequently, the statistical significance of Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) or Weighted Mean Difference (WMD), and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were estimated by Z tests. In addition, the symmetry of funnel plots was applied to determine the publication bias of the selected studies [15]. Sub-group analyses were carried out by HbA1c and ACR due to significant heterogeneity across the included studies.

Results

Literature search and selection

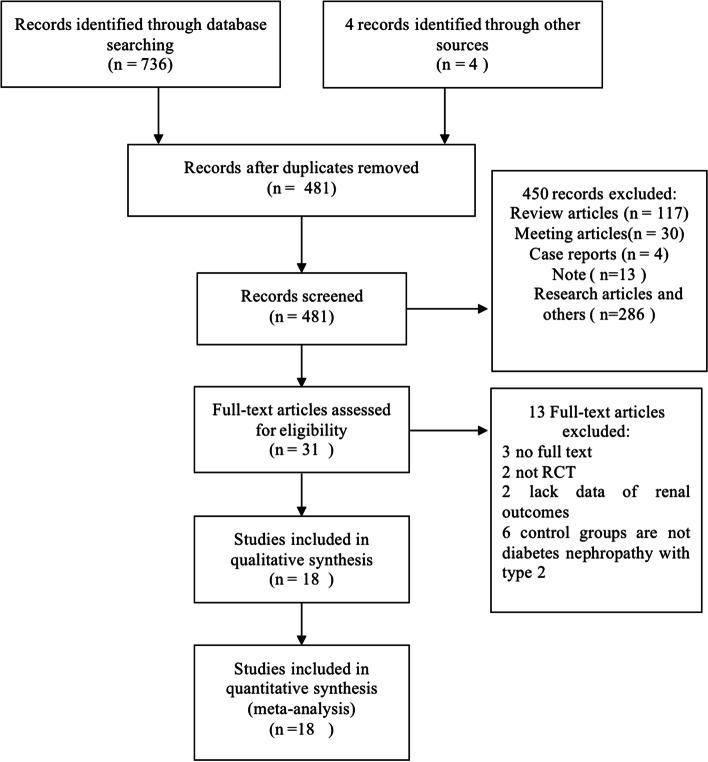

A total of 740 articles including 736 records from the electronic databases using different search strategies and 4 articles through literature tacking and reading were identified. After removing 481 duplications and 450 records unmet the inclusion criterion, 31 studies were selected to further verify through full-text reading. In the residual records, 13 full-text articles were excluded with reasons (n = 13) as follows: 2 trials are not RCT, 3 articles had no full text that could be found to extract data, 2 lack renal outcomes data, 6 control groups are not DN with type 2. Finally, 18 articles that satisfied the inclusion criteria were included in the meta-analysis. The procedure of finding articles and choosing studies was demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram of study selection

Characteristics of eligible studies

In our meta-analysis, all of the selected studies were published from 2014 to 2020. In detail, 18 studies [16–33] included 1580 DN patients enrolled in the study, of which 786 were in the liraglutide group and 794 were in the control group. Among these studies, 12 articles [17–21, 23, 24, 26–28, 30, 32, 33] illustrated the average age of patients with T2DN and the ratio of sex, while only 5 RCTs [17, 20, 23, 26, 32] showed the course of disease in patients with T2DM. Besides, in the liraglutide group, liraglutide was given a duration of 4 to 24 weeks with a dosage of 0.6 to 1.8 mg/day. However, kinds of drugs from different studies included trials placebo, routine treatment, Huangkui capsules, nephritis rehabilitation tablets, insulin or active comparators (metformin, glimepiride, and glargine) were used in the control group. The detailed characteristics of the included studies were listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies involved

| Research | Sample | Age/years | Sex ratio (males/females) | Course of T2DM/years | Interventions | Duration | Outcomes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T/C | T | C | T | C | T | C | T | C | |||

| Zha 2018 [16] | 30/30 | – | – | – | – | – | – | LIR(0.6 to 1.8 mg qd ih) plus Huang kui capsule | Huangkui Capsules 2.5 g tid po | 2 months | ACDF |

| Cao 2020 [17] | 30/30 | 55.21 ± 6.32 | 56.12 ± 6.92 | 17/13 | 15/15 | 4.08 ± 1.74 | 4.19 ± 1.52 | LIR(0.6 to 1.2 mg qd po) plus nephritis rehabilitation tablets | nephritis rehabilitation tablets 0.48 g/tablet, 5tablets/time, tid | 12 weeks | ABCGHIJK |

| Dong 2018 [18] | 43/43 | 53.7 ± 6.2 | 54.6 ± 8.7 | 20/23 | 23/20 | – | – | LIR(0.6 to 1.8 mg qd ih) + INS | INS | 6 months | ABCDEFGH |

| Chen 2016 [19] | 30/31 | – | – | – | – | – | – | LIR(0.6 to 1.8 mg qd ih) + RT | RT | 24 weeks | ACDEH |

| Hu Yanyun 2018 [20] | 55/55 | 59.64 ± 6.51 | 59.66 ± 6.54 | 35/20 | 37/18 | 6.28 ± 1.23 | 6.39 ± 1.14 | LIR(0.6 to 1.2 mg qd ih)plus RT | RT | 8 weeks | ABCHK |

| Ren Lijuan 2019 [21] | 15/15 | 44.8 ± 2.7 | 51.3 ± 2.9 | 7/8 | 9/6 | – | – | LIR (0.6 to 1.8 mg tid po) plus huangkui capsules | Huangkui Capsules 2.5 g tid | 6 months | ABCF |

| Ren Wei 2015 [22] | 24/24 | – | – | – | – | – | – | LIR(0.6 to 1.8 mg qd ih) + RT | RT | 6 months | ACDFH |

| Shi 2019 [23] | 30/30 | 57.32 ± 3.69 | 57.63 ± 3.12 | 17/13 | 18/12 | 7.13 ± 2.24 | 7.08 ± 1.71 | LIR (0.6 to 1.2 mg qd ih) plus Benazepril 10 mg qd | Benazepril 10 mg qd | 10 weeks | CHJKH |

| Yang 2016 [24] | 100/100 | 66.8 ± 14.7 | 67.4 ± 13.5 | 45/55 | 48/52 | – | – | LIR (0.6 to 1.2 mg qd ih) plus Telmisartan 40 mg qd | Telmisartan 40 mg qd | 10 weeks | CHJK |

| Zhao 2014 [25] | 19/26 | – | – | – | – | – | – | LIR (0.6 to 1.8 mg qd ih) plus Valsartan | Valsartan 80 mg qd | 6 months | CDI |

| Zheng 2015 [26] | 110/110 | 58 ± 4.9 | 57 ± 5.1 | 67/43 | 65/45 | 6.9 ± 2.8 | 7.1 ± 2.4 | LIR (0.6 to 1.2 mg qd ih) plus INS | INS | 4 weeks | ADGH |

| Hu Linlin 2018 [27] | 30/30 | 42.5 ± 11.6 | 41.3 ± 10.7 | 18/12 | 17/13 | – | – | LIR(0.6 to 1.8 mg tid po) plus huangkui capsules | Huangkui Capsules 2.5 g tid po | 6 months | ACDF |

| Aiyitan 2017 [28] | 89/73 | 58.1 ± 8.1 | 57.8 ± 7.9 | 49/40 | 39/34 | – | – | LIR(0.6 to 1.8 mg qd ih) plus RT | RT | 8 weeks | ABF |

| Shen 2017 [29] | 30/30 | – | – | 17/13 | 16/14 | – | – | LIR (0.6 to 1.2 mg qd ih) pluse Olmesartan 20 mg/d | Olmesartan 20 mg/d | 6 months | ACFHJK |

| Liu Rui 2016 [30] | 59/75 | 57.5 ± 7.4 | 58.2 ± 7.9 | 33/26 | 43/32 | – | – | LIR (0.6 to 1.2 mg qd ih) plus RT | RT | 8 weeks | ABF |

| Liu Chuyv 2015 [31] | 13/13 | – | – | – | – | – | – | LIR (0.6 to 1.2 mg qd ih) + Olmesartan | Olmesartan 20 mg qd + INS | 6 months | DFI |

| Li 2017 [32] | 21/21 | 48.2 ± 9.0 | 49.1 ± 8.3 | 11/10 | 13/8 | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 7.38 ± 1.5 | LIR plus RT | RT + INS | 12 weeks | ABCDEGH |

| Jian 2018 [33] | 58/58 | 56.51 ± 6.05 | 56.33 ± 8.63 | 32/26 | 29/29 | – | – | LIR (0.6 mg to 1.2 mg qd ih) plus Metformin | Metformin 1 g bid | 3 months | ABCDFHJK |

LIR liraglutide, RT routine treatment, INS insulin

A. FBG

B. PBG

C. HbA1c

D. BMI

E. eGFR

F. UACR

G. BUN

H. Scr

I. Cysc

J. IL-6

K. TNF-α

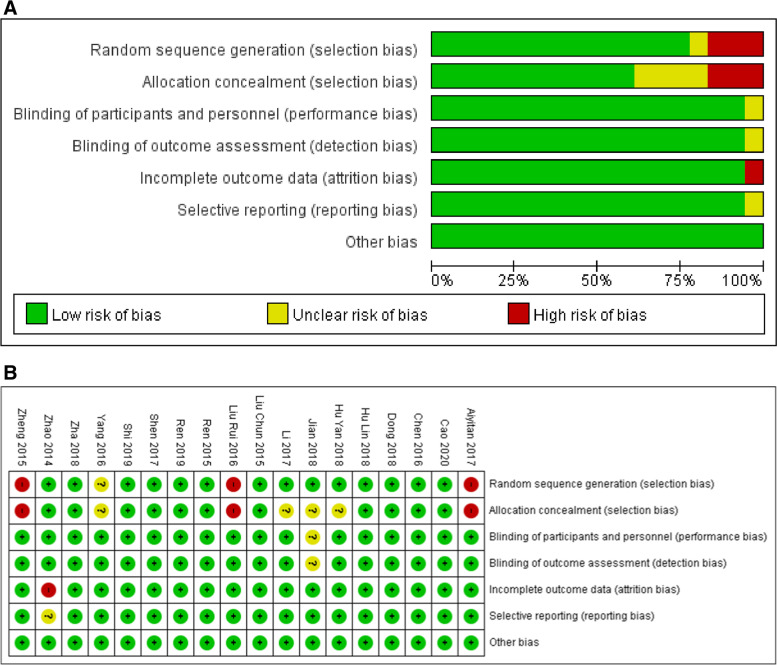

Risk of bias

The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool was used to evaluate the quality of the individual studies based on the randomization, allocation hiding, blinding, publication bias, etc. Among 18 studies, 14 of them were described as randomized trials (5 of which were random number table method), 1 study was grouped according to the patient’s wishes, 2 studies were grouped according to the patient’s original treatment, and the last one article has not mentioned the method of grouping. For allocation concealment, 4 studies were not mentioned, and 3 studies may have higher allocation hidden risk. In addition, one trial was a single-blind experiment, and the others were not indicated the method of blinding. Unfavorably, one article had incomplete primary outcome indicators and selective-publication possibility. Notably, no other bias factor was found in all articles. The specific quality evaluation chart was shown in Fig. 2A-B.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias graphs and summaries in several categories through all of the studies involved. A Risk of bias graph; B risk of bias summary

Effect of interventions

Relationship of liraglutide with renal function

To estimate the effect of liraglutide on renal function in patients with T2DN, the statistic differences of eGFR, BUN, Scr, UACR, and CysC between the liraglutide group and the control group were calculated and visualized by forest maps. The results of our meta-analysis suggested that there were significant differences between the liraglutide group and the control group in the levels of Scr (SMD = -0.81, 95% CI: [− 1.22,-0.4], p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3A, Table 2), UACR (SMD = -2.34, 95% CI: [− 3.65, − 1.03], p = 0.0005) (Fig. 3B, Table 2) and CysC (WMD or MD = -0.70, 95% CI: [− 1.01, − 0.39], p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3C, Table 2) after treatment. However, no differences between the liraglutide group and the control group were detected in the levels of BUN (WMD = -1.06, 95% CI: [− 2.22,0.10], p = 0.07) (Fig. 3D, Table 2) and eGFR(WMD = -0.81, 95% CI: [− 1.22, − 0.40], p = 0.21) (Fig. 3E, Table 2). In summary, liraglutide greatly reduced the levels of UACR, Scr, and Cysc compared with treatment without liraglutide.

Fig. 3.

Forest plots for the effects on renal function of liraglutide in patients diabetic nephropathy. A Scr; B UACR; C CysC; D BUN; E eGFR. SMD, standard mean difference; WMD, weight mean difference; CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; df, degrees of freedom; green squares, an effect size of each study; the size of green squares, the weight of each study; Black diamonds, test for overall effect; horizontal lines, confidence intervals

Table 2.

Study findings summary

| Outcome | Number of studies | Sample | Heterogeneity | Analysis model | Statistical method | WMD/SMD (95% CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test/Control | χ2 | I2 | P | ||||||

| FBG | 14 | 624/625 | 141.13 | 91% | < 0.00001 | Random-effects | Inverse Variance | −0.66[− 1.04,-0.27] | 0.0009 |

| PBG | 8 | 370/370 | 12.94 | 46% | 0.07 | Fixed-effects | Inverse Variance | −1.51[− 1.68,-1.34] | < 0.00001 |

| HbA1c | 14 | 515/523 | 217.29 | 94% | < 0.00001 | Random-effects | Inverse Variance | −0.61[− 0.95,-0.27] | 0.0004 |

| BMI | 10 | 378/386 | 98.99 | 91% | < 0.00001 | Random-effects | Inverse Variance | −2.27[−2.98,-1.56] | < 0.00001 |

| eGFR | 3 | 94/95 | 15.20 | 87% | 0.0005 | Random-effects | Inverse Variance | 6.46[−3.69,16.61] | 0.21 |

| UACR | 10 | 391/397 | 366.83 | 98% | < 0.00001 | Random-effects | Inverse Variance | −2.34[−3.65,-1.03] | 0.0005 |

| BUN | 4 | 204/204 | 48.46 | 94% | < 0.00001 | Random-effects | Inverse Variance | −1.06[−2.22,0.10] | 0.07 |

| Scr | 11 | 531/532 | 94.16 | 89% | < 0.00001 | Random-effects | Inverse Variance | −0.81[−1.22,-0.4] | < 0.0001 |

| CysC | 2 | 32/39 | 0.44 | 0% | 0.5 | Fixed-effects | Inverse Variance | −0.7[−1.01,-0.39] | < 0.0001 |

| IL-6 | 5 | 248/248 | 130.43 | 97% | < 0.00001 | Random-effects | Inverse Variance | −2.03[−3.30,-0.77] | 0.002 |

| TNF-α | 6 | 303/303 | 38.24 | 87% | < 0.00001 | Random-effects | Inverse Variance | −1.16[−1.66,-0.66] | < 0.00001 |

Relationship of liraglutide with hypoglycemic related indicators and BMI

For validating the influence of liraglutide on hypoglycemic-related indicators and BMI in patients with T2DN, the statistical differences of FBG, PBG, HbA1c, and BMI between the liraglutide group and the control group were estimated. As shown in the Fig. 4A and Table 2, the patients in the liraglutide group measured lower levels of FBG (WMD = -0.66, 95% CI: [− 1.04,-0.27], p = 0.0009) (Fig. 4A, Table 2), PBG (WMD = -1.51, 95% CI: [− 1.68,-1.34], p < 0.00001) (Fig. 4B, Table 2), HbA1c (WMD = -0.61, 95% CI: [− 0.95,-0.27], p = 0.0004) (Fig. 4C, Table 2) and BMI (WMD = -2.27, 95% CI:[− 2.98,-1.56], p < 0.00001) (Fig. 4D, Table 2) than patients in the control group, suggesting the excellent performance in controlling blood sugar and weight loss of liraglutide.

Fig. 4.

Forest plots for the effects of liraglutide on hypoglycemic-related indicators and BMI of patients with diabetic nephropathy. A FBG; B PBG; C HbA1c; D BMI. WMD, weight mean difference; CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; df, degrees of freedom; green squares, an effect size of each study; the size of green squares, the weight of each study; Black diamonds, test for overall effect; horizontal lines, confidence intervals

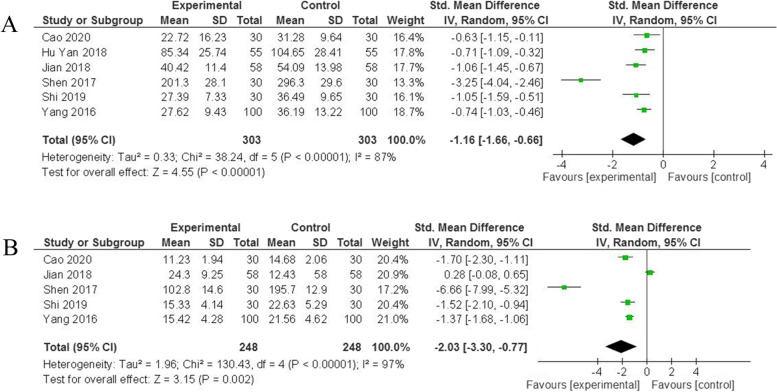

Relationship of liraglutide with anti-inflammatory indicators

To further confirm whether the liraglutide could reduce inflammatory reaction and thus prevent renal fibrosis, we compared the levels of IL-6 and TNF-α between the liraglutide group and the control group after drug intervention. Notably, liraglutide was demonstrated to delay the process of renal fibrosis by anti-inflammatory in our analysis. Obviously, the liraglutide group had lower level of TNF-α (SMD = -1.16, 95% CI: [− 1.66,-0.66], p < 0.00001) (Fig. 5A, Table 2) and IL-6 (SMD = -2.03, 95% CI: [− 3.30,-0.77], p = 0.002) (Fig. 5B, Table 2) than control group.

Fig. 5.

Forest plots for the effects of liraglutide on anti-inflammatory indicators of patients with diabetic nephropathy. A TNF-α; B IL-6. SMD, standard mean difference; CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; df, degrees of freedom; green squares, the effect size of each study; the size of green squares, the weight of each study; Black diamonds, test for overall effect; horizontal lines, confidence intervals

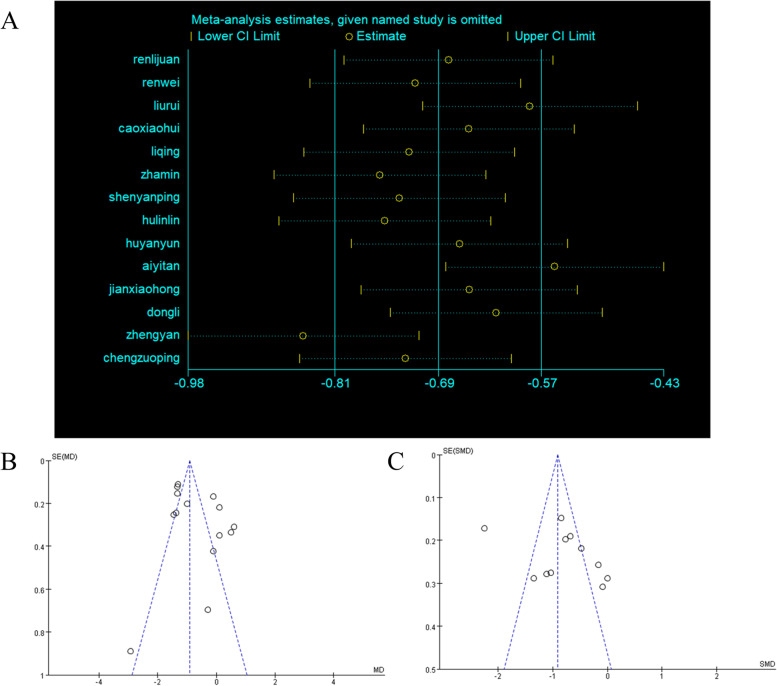

Sensitivity analysis and evaluation of publication bias

To verify the sources of heterogeneity, sensitivity analysis by removing each study gradually was performed using Stata 13 software. The result showed that when removing the studies of Zhengyan [25] and Aiyitan [27], obvious changes of pooled WMD were found (Fig. 6A). Therefore, we considered the heterogeneity coming from these two studies. Moreover, funnel plots drawn with Revman software were used to show publication bias. Asymmetry was detected in Fig. 6B-C, suggesting that there may be publication bias, and the results that are not statistically significant may not be published.

Fig. 6.

Sensitivity analysis and funnel plots for assessment of publication bias. A Sensitivity analysis based on FBG; B funnel plots based on FBG; C funnel plots based on Scr. MD, mean difference; SE(MD), Standard Error (mean difference); SE(SMD), Standard Error (standard mean difference)

Discussion

Diabetic Nephropathy(DN) is one of the main complications of Diabetes Mellitus. DN is caused by a number of causes, including metabolic and hemodynamic disorders [34]. Some studies have shown that GLP-1RA can reduce proteinuria and improve renal function. The mechanism may be that GLP-1RA induce NHE3 (Na+ /H+ exchanger 3-) phosphorylated and activated, which can result in the reabsorption of filtered Na + increase in the proximal tubule [35, 36], which may improve renal hemodynamics in diabetes-associated glomerular hyperfiltration through overlapping and separate mechanisms, then helps to reduce albuminuria. Liraglutide also alleviated the accumulation of glomerular extracellular matrix (ECM) and renal injury in DN by improving the signaling of Wnt/β-catenin. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is involved in mesangial cell production of ECM (MCs). Treatment with liraglutide significantly reduced high glucose (HG)-stimulated production of fibronectin (FN), collagen IV (Col IV), and alpha-smooth muscle actin (alpha-SMA) in cultured human mesangial cells (HMCs) and significantly attenuated the liraglutide effects with XAV-939, a selective Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibitor [37]. In addition, Our results have shown that liraglutide can reduce urinary protein indicators of UACR and renal function indicators including Scr and Cysc, which also confirm these points. But GLP-1RA has no clinically important effect on SUN and eGFR, which may be due to the insufficient number of RCT included.

About blood glucose and BMI, liraglutide decreased BMI and blood glucose levels in the current meta-analysis [38]. The hypoglycemic mechanism of liraglutide relies on it can increase insulin secretion and alpha beta-cell action to inhibit glucagon release, which leads to decreased plasma glucose in diabetes patients, and the role of central nervous receptors to increase satiety delayed gastric emptying [39]. Our results also show that liraglutide can decrease the level of blood glucose, BMI.

In the development of DN, NF-kB plays a central role in the inflammatory pathway [40]. Regulated nuclear factor kappa-b NF-kB activation and subsequent inflammatory response in mesangial cells are involved in the hyperglycemia-induced downregulation of GLP-1R [41]. In this meta-analysis, the results also showed that, in the liraglutide group, the down-regulated TNF-a and IL-6 levels were better than in the control group. Although the number of studies we included was small, liraglutide was shown to have an anti-inflammatory effect on the kidney in conjunction with previous studies.

The following limitations exist in this study. No blind method was used in all the studies. As a result, the quality of the included literature declined relatively, and there exists implementation bias. The inconsistency in baseline data, treatment base measures, and experimental protocols of Zhengyan’s and Aiyitan’s study led to heterogeneity according to our sensitivity analysis.

Conclusion

In patients with DN, liraglutide appears to be beneficial in lowering urine protein, strengthening renal function, improving blood sugar levels, and having anti-inflammatory effects. To further investigate the effects of GLP-1RA liraglutide on ESRD in the future, and provide evidence-based medical information to prove clinical safety and rational drug usage, RCTs from more centers and large sample randomized double-blind controlled trials are needed due to certain limitations. Thus, liraglutide therapy of patients with type 2 diabetes has beneficial effects on kidney outcomes. Such findings support the advantages of using liraglutide for clinical use.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- T2DN

Type2 diabetic nephropathy

- CNKI

Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure

- CBM

China Biology Medicine Database

- RCTs

Randomized controlled trials

- BMI

Body mass index

- Lira

Liraglutide

- ESRD

End-stage renal disease

- GLP-1RA

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists

- eGFR

Glomerular filtration rate

- UACR

Urine albumin creatinine ratio

- BUN

Blood Urea Nitrogen

- Scr

Serum creatinine

- CysC

Serum cystatin C

- SMD

Standardized Mean Difference

- WMD

Weighted Mean Difference

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- HMCs

Human mesangial cells

- FN

Fibronectin

- Col IV

Collagen IV

- NF-kB

Nuclear factor kappa-b

Authors’ contributions

N.M. and F.S. conceived the study, participated in data collection, and performed the analysis. N.M., F.S., WX. F., J.G., J. Z. and JY. M. participated in data collection and the interpretation of the results. All authors participated in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from Yunnan Health Technical Training Project of High-level Talents (Project Number: D-2018027) and Yunnan Basic Research Projects - General Program (Project Number: 2019FB092).

Availability of data and materials

There is no additional data than the contained within the present manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Niroj Mali and Feng Su contributed equally to this article, and Feng Su should be considered co-first author.

Contributor Information

Niroj Mali, Email: maliniroj@qq.com.

Feng Su, Email: 462385406@qq.com.

Jie Ge, Email: gejie2020@163.com.

Wen Xing Fan, Email: fanwx2020@163.com.

Jing Zhang, Email: 546811989@qq.com.

Jingyuan Ma, Email: Ma15087745145@163.com.

References

- 1.Cosgrove P, Engelgau M, Islam I. Cost-effective approaches to diabetes care and prevention. Diabetes Voice. 2002;47(4):13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gheith O, Farouk N, Nampoory N, Halim MA, Al-Otaibi T. Diabetic kidney disease: world wide difference of prevalence and risk factors. J Nephropharmacol. 2015;5(1):49–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anders HJ, Huber TB, Isermann B, Schiffer M. CKD in diabetes: diabetic kidney disease versus nondiabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(6):361–377. doi: 10.1038/s41581-018-0001-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le P, Chaitoff A, Misra-Hebert AD, Ye W, Herman WH, Rothberg MB. Use of Antihyperglycemic medications in U.S. adults: an analysis of the National Health and nutrition examination survey. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(6):1227–1233. doi: 10.2337/dc19-2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zinman B, Nauck MA, Bosch-Traberg H, Frimer-Larsen H, Orsted DD, Buse JB, et al. Liraglutide and Glycaemic outcomes in the LEADER trial. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9:2383–2392. doi: 10.1007/s13300-018-0524-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, Kristensen P, Mann JF, Nauck MA, et al. LEADER steering committee; LEADER trial investigators. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311–322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Von Scholten BJ, Persson F, Rosenlund S, Hovind P, Faber J, Hansen TW, et al. The effect of liraglutide on renal function: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(2):239–247. doi: 10.1111/dom.12808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mann JFE, Ørsted DD, Brown-Frandsen K, Marso SP, Poulter NR, Rasmussen S, et al. LEADER steering committee and investigators. Liraglutide and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(9):839–848. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1616011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies MJ, Bain SC, Atkin SL, Rossing P, Scott D, Shamkhalova MS, et al. Efficacy and safety of Liraglutide versus placebo as add-on to glucose-lowering therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate renal impairment (LIRA-RENAL): a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(2):222–230. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.2. The cochrane collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins J, Thompson S, Deeks J. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borenstein M, Higgins J. Meta-analysis and subgroups. Prev Sci. 2013;14:134–143. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0377-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egger M, SmithG D, Schneider M. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zha M, Zhang S, Ruan Y, Shi M, Zhou L, Huang LJ. Clinical effects of combination therapy of Huangkui capsules and liraglutide on patients with early diabetic nephropathy. Chin Trad Patent Med. 2018;40:1493–1495. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao X, Jia L, Hu Y. Effect of liraglutide combined nephritis rehabilitation tablets for type 2 diabetic nephropathy. JHMC. 2020;26(1):0059–0062. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong L, Zhao JH. Effects of liraglutide on renal function in patients with microalbuminuria of diabetic nephropathy. Lin Chang Hui Cui. 2018;33:420–423. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen ZP. Efficacy and safety analysis of Liraglutide in treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and mild to moderate renal disease. Chin Contemp Med. 2016;23:131–133. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu Y, Jia L, Cao X, Yin C. Effect of liraglutide on soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor in patients with diabetic nephropathy. JHMC. 2018;24(14):1319–1322. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liyuan R. Yellow sunflower capsule sinalutide on early diabetes analysis of clinical efficacy of patients with kidney disease. WHR. 2019;14:24–6.

- 22.Ren W, Guo JJ, Zuo GX, Li YB, Gao LL, Li X, et al. Effects of liraglutide on early diabetic nephropathy with obese. Chin Remed Clin. 2015;15:1284–1286. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiangya S. Efficacy of liraglutide combined with angiotensin conversion enzyme inhibitors for the treatment of diabetic nephritis and prognosis observation. Fujian Med J. 2019;41(6):129–31.

- 24.Yang R, Wang YF, Zhang W. Liraglutide combined with low dosage telmisartan decreases the serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and TGF-β1 in patients with early diabetic nephropathy. Med J West China. 2016;28:191–194. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao CY, Guo HT, Dai HS, Tian JR, Zhao YQ. Clinical effects of liraglutide on early diabetic nephropathy. Shandong Med. 2014;54:47–49. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng Y, Yu SD. Clinical effects of combination therapy of insulin glargine and liraglutide on type 2 diabetic patients with nephropathy. Xiandai Shi Yong Yi Xue. 2015;27:251–253. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu L. Early diabetic nephropathy using jaundice capsules combined with liraglutide treatment clinical efficacy analysis. Diabetes World. 2018;15(6):83–4.

- 28.Aiyitan A, Qing Q. Clinical effect of liraglutide in treating early diabetic nephropathies and the influence of renal function and adipocytokines. Chin J Clin Rational Drug Use. 2017;10:10–14. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen YP, Qiao Q, Lu GY. Effect of liraglutide on PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Huazhong Ke Ji Da Xue Xue Bao (Yi Xue Ban) 2017;46:466–470. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu R. Protective effect of hypoglycemic therapy by liraglutide on renal function in early diabetic nephropathy. J Hainan Med Univ. 2016;22:43–46. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu CY. Liraglutide treatment efficacy of early type 2 diabetic nephropathy and its mechanism analysis. Master thesis. Dalian Medical University; 2015.

- 32.Li Q, Cao WJ, Zhou GY, Yang LH. Effects of liraglutide on early diabetic nephropathy and its relationship with the changes of VEGF and VEGF-A. Xiangnan Xue Yuan Xue Bao (Yi Xue Ban) 2017;19:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiaohong J. Clinical study of liraglutide injections for overweight and obese type 2 diabetes with trace albuminuria. Chin J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;34(24):2803–2806. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fineberg D, Jandeleit-Dahm KA, Cooper ME. Diabetic nephropathy: diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:713–723. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schultheis PJ, Clarke LL, Meneton P, Miller ML, Soleimani M, Gawenis LR, et al. Renal and intestinal absorptive defects in mice lacking the NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger. Nat Genet. 1998;19:282–285. doi: 10.1038/969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muskiet M, Tonneijck L, Smits M, et al. GLP-1 and the kidney: from physiology to pharmacology and outcomes in diabetes. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13:605–628. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang L, Lin T, Shi M, Chen X, Wu P. Liraglutide suppresses production of extracellular matrix proteins and ameliorates renal injury of diabetic nephropathy by enhancing Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2020;319(3):F458–F468. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00128.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu W, Yu J, Tian T, Miao J, Shang W. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes accompanied by incipient nephropathy. Exp Ther Med. 2019;18(1):342–351. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baggio LL, Drucker DJ. Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(6):2131–2157. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawanami D, Matoba K, Utsunomiya K. Signaling pathways in diabetic nephropathy. Histol Histopathol. 2016;31(10):1059–1067. doi: 10.14670/HH-11-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang Z, Zeng J, Zhang T, Lin S, Gao J, Jiang C, et al. Hyperglycemia induces NF-kappa B activation and MCP-1 expression via downregulating GLP-1R expression in rat mesangial cells: inhibition by metformin. Cell Biol Int. 2019;43:940–953. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There is no additional data than the contained within the present manuscript.