Abstract

Purpose

We sought to investigate the perioperative opioid prescription patterns, complication rates, and costs associated with wide-awake local anesthesia (WALA) techniques using a nationwide insurance claims-based database.

Methods

We used the PearlDiver Humana administrative claims database to identify opioid-naive adult patients who underwent a carpal tunnel release, trigger finger release, or de Quervain release between 2007 and 2015. Patients were divided into WALA and standard anesthesia groups by the presence or absence of anesthesia Current Procedural Terminology codes. We evaluated for differences in perioperative opioid prescribing patterns, rates of opioid refills, and insurance reimbursement. The incidence of surgical complications and medical complications within 30 days of surgery were determined by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes. Adjusted odds ratios were calculated with multivariable logistic regression models to identify factors associated with filling or refilling opioid prescriptions and complication rates.

Results

There were 6,285 patients in the WALA group and 28,657 in the standard anesthesia group. The WALA patients were prescribed significantly lower quantities of opioids than were standard anesthesia patients across all 3 procedures. After controlling for type of surgery, gender, and comorbidities in a multivariate model, WALA patients were less likely to fill an initial opioid prescription during the perioperative period but were equally likely to obtain a refill. The WALA patients had lower odds of developing both surgical and medical complications compared with standard anesthesia patients. Moreover, WALA was associated with significantly lower costs for all procedures.

Conclusions

Wide-awake local anesthesia technique is an increasingly common and viable option for minor hand surgery. It is a cost-effective and safe technique for simple hand surgical procedures and can be a strategy to minimize postoperative opioid use.

Type of study/level of evidence

Prognostic II.

Key words: anesthesia, hand surgery, opioids, WALANT, wide-awake

Wide-awake local anesthesia (WALA) has become increasingly popular in hand surgery. Interest in the field has grown since the early 2010s after multiple studies dispelled concerns regarding epinephrine use in digits causing finger necrosis.1 Advocates for wide-awake hand surgery claim the technique avoids the risks of intravenous and inhaled anesthetics and saves time by obviating the need for anesthetic induction and recovery periods.2 Wide-awake local anesthesia surgery has been recommended as a useful technique in a variety of hand procedures such as carpal tunnel release (CTR), trigger finger release (TFR), de Quervain release (DQR), tendon repairs and transfers, and finger fracture or arthrodesis surgeries.3 Prior studies demonstrated a cost savings with wide-awake techniques for trigger finger4 and CTR surgeries.5, 6, 7 Furthermore, Ruxasagulwong et al8 did not note a difference in complication rates between wide-awake and standard anesthesia techniques. Although current literature suggests lower costs and similar complication rates with WALA, we aimed to explore costs and complications simultaneously across multiple minor hand surgery procedures on a population level.

Existing evidence on postoperative opioid requirements after outpatient hand surgery is also sparse.9 Prescription opioid abuse is an increasingly prevalent problem in the United States (US), leading to what is known as the opioid epidemic. From 2002 to 2017, there was a 4-fold increase in the total number of deaths related to opioids in the US.10 As a result, postoperative opioid prescription patterns have come under increasing national scrutiny. Approximately 3% to 6% of surgical patients become new persistent opioid users after surgery.11,12

We sought to investigate the complication rates and postoperative opioid prescription patterns associated with WALA techniques using a nationwide insurance claims-based database. As secondary aims, we sought to quantify the change in use and costs associated with wide-awake surgery in the US from 2008 to 2015.

We hypothesized that 30-day surgical and medical complications would be comparable between wide-awake and standard groups, with similar opioid fill rates between groups. Furthermore, we predicted a trend toward increased use of wide-awake techniques from 2008 to 2015, as well as decreased payer costs relative to standard anesthesia techniques.

Materials and Methods

This analysis utilized the PearlDiver Patient Records Database (Colorado Springs, CO), a retrospective nationwide insurance billing database of over 25 million patients. Records in the PearlDiver Patient Records Database are acquired from Humana’s (Louisville, KY) claims database, deidentified, and released commercially for research purposes. Humana is a private insurance company that offers both commercial and Medicare advantage plans. Claims in the PearlDiver database are from patients enrolled in either of Humana’s commercial or Medicare advantage plans between 2007 and 2015.

We used Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes (Table 1) to identify opioid-naive patients aged 18 years or older, who had CTR, TFR, or DQR surgeries and were enrolled in the database for a minimum of 90 days after surgery. Patients undergoing any other same-day musculoskeletal procedure were excluded. Patients were divided into WALA and standard anesthesia (sedation or general anesthesia) groups based on the presence or absence of same-day anesthesia CPT codes (Table 2). Surgical encounters without an associated anesthesia CPT code were considered to have been performed with local anesthesia. To capture patients who may have received a preoperative prescription leading up to surgery, we defined opioid-naive patients as those without an opioid prescription from 2 months before surgery up to the week before surgery.

Table 1.

CPT and ICD-9 Codes for Diagnoses and Hand Surgeries in This Study

| Procedure | ICD-9 Code | CPT Code |

|---|---|---|

| TFR | 72703 | 26055 |

| DQR | 72704 | 25000 |

| CTR | 3540 | 64721 |

Table 2.

Current Procedural Terminology Codes for Standard Anesthesia in This Study

| Procedure | CPT Code |

|---|---|

| Monitored anesthesia care | 00100–01999 |

| Anesthesia for procedures of forearm, wrist, and hand | 01810–01860 |

| Moderate (conscious) sedation performed by primary provider | 99143–99145 |

| Moderate (conscious) sedation performed by second provider | 99148–99150 |

The 2 groups were evaluated for differences in type of surgery (CTR, TFR, and DQR), demographic factors, and baseline comorbidities. Comorbidities were quantified using the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI).13 We determined the incidence of acute surgical complications and medical complications within 30 days of surgery for the 2 groups based on the presence of corresponding ICD-9 codes (Table 3).14

Table 3.

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision Codes for 30-d Surgical and Medical Complications

| Complication | ICD-9 Codes |

|---|---|

| Surgical complications | |

| Hematoma | 998.11, 998.12 |

| Seroma | 998.13 |

| Infection/cellulitis | 998.5, 998.51, 998.59, 682.9 |

| Wound dehiscence | 998.30, 998.31, 998.32, 998.33 |

| Medical complications | |

| Sepsis | 995.91, 995.92 |

| Septic shock | 785.52 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 415.11, 415.12, 415.13, 415.19 |

| Ventilator (> 24 h) | V46.11 |

| Unplanned intubation (nonsurgical intubation and irrigation) | 96 |

| Acute renal failure (unspecified) | 584.5–584.9 |

| Cardiac arrest | 427.5 |

| Myocardial infarction (acute myocardial infarction) | 410.00–410.92 |

| Stroke (cerebral artery occlusion, unspecified with cerebral infarction) | 434.91 |

| Coma (> 24 h) (general coma not specifically > 24 h) | 780.01 |

| Pneumonia | 480–486 |

| Urinary tract infection (site not specified) | 599 |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 453.4 |

| Transfusion | 9904, V58.2 |

| Cardiopulmonary complications | 997.1 |

We also compared groups for differences in the fill rate of initial perioperative opioid prescriptions associated with each type of surgery. Hydrocodone–acetaminophen, oxycodone–acetaminophen, acetaminophen–codeine, and oxycodone represent greater than 95% of Food and Drug Administration–approved oral opioid prescriptions and were included in the analysis (Table 4).15 The database was queried to determine prescription fill rates for individual medications. To allow for comparisons across multiple opioid medications, all opioid prescription quantities were multiplied by an appropriate scaling factor to convert them to oral morphine equivalents (OMEs).9,16 The initial perioperative prescription period was defined as the week before surgery through 2 days after surgery. A refill was defined as any second opioid prescription filled within the 30-day postoperative period, and the opioid refill rate was compared between groups.

Table 4.

Opioid Prescription Type by Anesthesia Type

| Drug | Standard |

WALA |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | % | Patients | % | |

| Hydrocodone–acetaminophen | 14,848 | 72.3 | 2,622 | 75.7 |

| Oxycodone–acetaminophen | 3,198 | 15.6 | 336 | 9.70 |

| Acetaminophen–codeine 3 | 1,245 | 6.06 | 386 | 11.2 |

| Oxycodone–HCl | 407 | 1.98 | 66 | 1.90 |

| All others | 833 | 4.06 | 52 | 1.50 |

| Total | 20,531 | 100 | 3,462 | 100 |

Finally, we evaluated for differences in physician reimbursement and overall reimbursement associated with the surgical encounter (including facility fee, physician reimbursement, prescriptions, etc) between the groups of patients. Reimbursements were stratified by type of surgery (CTR, TFR, and DQR). For the standard anesthesia group, anesthesia reimbursements were analyzed separately. To account for the effects of inflation on this analysis, all dollar values were converted into 2015 US dollars using the consumer price index.17

We used multivariate regression models to identify factors associated with increased odds of surgical and medical complications. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) were calculated in another multivariable logistic regression model to identify factors associated with filling or refilling opioid prescriptions. Differences in average surgeon reimbursement and overall reimbursement between WALA and standard anesthesia were analyzed. We performed data management using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). All statistical analyses were performed using R software (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

Results

We identified 6,285 patients in the WALA group and 28,657 in the standard anesthesia group. The WALA patients were less likely to undergo CTR and DQR and more likely to undergo TFR compared with standard anesthesia patients. Moreover, WALA patients were more likely to be male than were standard anesthesia patients (41.0% vs 38.7%; P < .001) (Table 5). The WALA patients tended to be older; 75% were aged older than 65 years, compared with 70.8% of standard anesthesia patients (P < .001) (Table 5). In addition, WALA patients receiving CTR and TFR had fewer comorbidities than did standard anesthesia patients (ECI 7.29 vs 7.82, P < .001; and 6.83 vs 7.5, P < .001, respectively) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Characteristics of Study Cohort by Anesthesia Type

| Characteristic | Standard | WALA | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients (%) | 28,657 (100) | 6,285 (100) | |

| CTR | 22,721 (68.4) | 3,255 (51.8) | < .001 |

| TFR | 8,996 (27.1) | 2,824 (45.0) | < .001 |

| DQR | 1,458 (4.4) | 206 (3.2) | < .001 |

| Gender (%) | |||

| Female | 17,565 (61.3) | 3,737 (59.0) | < .001 |

| Male | 11,092 (38.7) | 2,548 (41.0) | < .001 |

| Age, y (%) | |||

| 20–34 | 284 (1.0) | 27 (0.4) | <.001 |

| 35–44 | 921 (3.1) | 123 (1.9) | <.001 |

| 45–54 | 2,743 (9.4) | 460 (7.3) | <.001 |

| 55–64 | 4,570 (15.7) | 982 (15.5) | 0.69 |

| ≥ 65 | 20,625 (70.8) | 4,748 (75.0) | <.001 |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (mean [SD]) | |||

| CTR | 7.82 (4.62) | 7.29 (4.56) | <.001 |

| TFR | 7.5 (4.57) | 6.83 (4.45) | <.001 |

| DQR | 6.7 (4.58) | 6.03 (4.63) | .053 |

From 2008 to 2015, WALA use increased from 18% to 21% for all procedures, whereas standard anesthesia use decreased from 82% to 79% (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Use of WALA and standard anesthesia for CTR, DQR, and TFR from 2008 to 2015.

After controlling for type of surgery, gender, and comorbidities, multivariate logistic regression demonstrated that compared with standard anesthesia, patients in the WALA group had a lower odds of developing both surgical (OR = 0.51; confidence interval [CI], 0.38–0.66) (Table 6) and medical (OR = 0.89; CI, 0.8–0.99 (Table 6) complications within 30 days of surgery. The most common acute surgical complications were surgical site infections; the most common medical complications were urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and acute renal failure (Table 7).

Table 6.

Adjusted Odds of Developing Surgical or Medical Complication Within 30 d, by Patient Characteristics, Type of Surgery, and Type of Anesthesia

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio of Developing Surgical Complication | P Value | Odds Ratio of Developing Medical Complication | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of anesthesia | ||||

| Standard anesthesia | 1 | 1 | ||

| WALA | 0.51 (0.38–0.66) | < .001 | 0.89 (0.80–0.99) | .042 |

| Type of surgery | ||||

| TFR | 1 | 1 | ||

| DQR | 0.38 (0.20–0.66) | .001 | 0.98 (0.80–1.19) | .89 |

| CTR | 1.29 (1.11–1.49) | < .001 | 1.17 (1.08–1.25) | < .001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | ||

| Male | 1.17 (1.04–1.33) | < .01 | 0.58 (0.54–0.62) | < .001 |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index | 1.09 (1.07–1.11) | < .001 | 1.15 (1.14–1.17) | < .001 |

| Age, y | ||||

| < 50 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 50–60 | 0.83 (0.67–1.03) | .09 | 1.55 (1.33–1.81) | < .001 |

| 65–80 | 0.55 (0.45–0.68) | < .001 | 1.62 (1.41–1.87) | < .001 |

| > 80 | 0.44 (0.34–0.56) | < .001 | 1.94 (1.67–2.25) | < .001 |

Table 7.

Thirty-Day Medical and Surgical Complications by Code∗

| Complication | WALA | % | Standard | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical complications | ||||

| Sepsis | < 10 | 20 | 0.06 | |

| Septic shock | < 10 | < 10 | ||

| Pulmonary embolism | < 10 | 49 | 0.15 | |

| Ventilator > 24 h | < 10 | < 10 | ||

| Acute renal failure | 18 | 0.27 | 106 | 0.34 |

| Cardiac arrest | < 10 | < 10 | ||

| Myocardial infarction | < 10 | 39 | 0.12 | |

| Stroke | 14 | 0.21 | 61 | 0.19 |

| Coma | < 10 | < 10 | ||

| Pneumonia | 27 | 0.41 | 121 | 0.39 |

| Urinary tract infection | 88 | 1.33 | 545 | 1.75 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | < 10 | 61 | 0.19 | |

| Transfusion | < 10 | < 10 | ||

| Cardiac nonspecified | < 10 | < 10 | ||

| Total events | 147 | 2.33 | 1002 | 3.49 |

| Total patients | 170 | 2.70 | 926 | 3.23 |

| Surgical complications | ||||

| Cellulitis | < 10 | 87 | 0.28 | |

| Disruption of external operation | < 10 | 55 | 0.17 | |

| Other postoperative infection | 21 | 0.31 | 121 | 0.39 |

| Total events | < 40 | < 0.6 | 263 | 0.85 |

| Total patients | 30 | 0.46 | 248 | 0.88 |

Groups of fewer than 10 patients were not reported to protect patient privacy.

In univariate analysis, there were no differences in the rate of filling perioperative opioid prescriptions for TFR or DQR patients, whereas there was a minimal but statistically significant difference for CTR: WALA patients were less likely than standard anesthesia patients to fill a perioperative opioid prescription after CTR (53.3% vs 56.7%; P < .001). In the WALA group, CTR and DQR patients were less likely to obtain a refill in the postoperative period (Table 8). Of all patients who filled an initial opioid prescription, WALA patients were prescribed significantly lower quantities of opioids overall than were standard anesthesia patients (289 vs 342 OME; P < .001). This was a statistically significant finding across all 3 surgical procedures (Table 8).

Table 8.

Opioid Prescription Quantity, Fill Rates, and Refill Rates by Anesthesia Type

| Characteristic | Standard | WALA | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 28,657 | 6,285 | |

| Filled perioperative prescription (%) | |||

| Overall | 17,631 (61.5) | 3,175 (50.5) | < .001 |

| CTR | 12,876 (56.7) | 1,834 (53.3) | .001 |

| TFR | 4,041 (45.0) | 1,233 (43.7) | .23 |

| DQR | 714 (49.0) | 108 (52.4) | .36 |

| Filled second prescription (%) | |||

| Overall | 3,907 (22.1) | 612 (19.3) | < .001 |

| CTR | 3,060 (23.8) | 387 (21.1) | .01 |

| TFR | 691 (17.1) | 214 (17.4) | .81 |

| DQR | 156 (21.8) | 11 (10.2) | .005 |

| Oral morphine equivalents per patient (mean [SD]) | |||

| Overall | 342.6 (316.8) | 289.2 (211.1) | < .001 |

| CTR | 349.1 (321.1) | 292.5 (218.9) | < .001 |

| TFR | 304.9 (267.9) | 267.1 (200.6) | < .001 |

| DQR | 329.2 (251.9) | 183.9 (122.6) | < .001 |

After controlling for type of surgery in the multivariate model, type of anesthesia was found to be an independent predictor for perioperative opioid prescriptions. A lower proportion of WALA patients filled an initial opioid prescription during the perioperative period than did standard anesthesia patients (OR = 0.71; 95% CI, 0.69–0.74), but type of anesthesia did not affect the odds of obtaining a refill in multivariate analysis. Factors associated with increased odds of obtaining a refill included younger age, higher ECI score, and undergoing CTR or DQR (Table 9).

Table 9.

Adjusted Odds of Filling Perioperative Opioid Prescriptions, by Patient Characteristics, Type of Surgery, and Type of Anesthesia∗

| Characteristic | Odds of Filling Perioperative Prescription | P Value | Odds of Obtaining Refill | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of anesthesia | ||||

| Standard | 1 | 1 | ||

| WALA | 0.71 (0.69–0.74) | < .001 | 0.60 (0.54–0.66) | .19 |

| Type of surgery | ||||

| TFR | 1 | 1 | ||

| CTR | 1.26 (1.23–1.29) | < .001 | 1.77 (1.65–1.89) | < .001 |

| DQR | 1.10 (1.03–1.18) | .007 | 1.19 (1.02–1.38) | .025 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | ||

| Male | 0.96 (0.94–0.99) | .002 | 0.96 (0.89–1.04) | .097 |

| Age, y | ||||

| < 50 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 50–65 | 0.82 (0.79–0.87) | < .001 | 0.94 (0.86–1.03) | .20 |

| 65–80 | 0.63 (0.60–0.66) | < .001 | 0.35 (0.32–0.38) | < .001 |

| > 80 | 0.46 (0.44–0.48) | < .001 | 0.22 (0.32–1.11) | < .001 |

| ECI score | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | < .001 | 1.10 (0.19–0.24) | < .001 |

Data are shown as ORs and 95% confidence intervals.

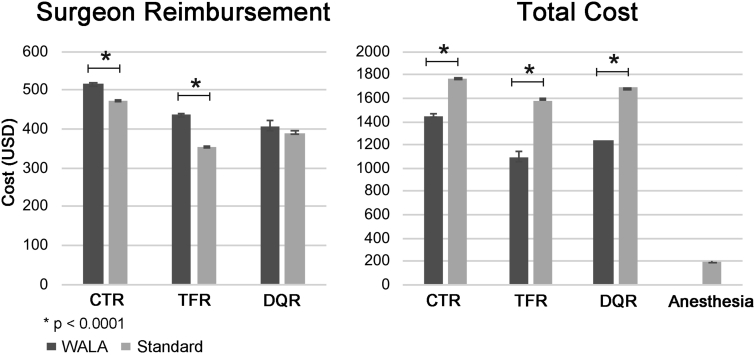

Moreover, WALA was associated with significantly lower overall costs (including physician reimbursement and facility fees) compared with standard anesthesia for all 3 types of surgery. Average surgeon reimbursement was significantly higher with WALA for CTR and TFR but not DQR (Fig. 2, Table 10). Overall average anesthesia reimbursement was $195.53 for the standard anesthesia group.

Figure 2.

Average physician reimbursement and overall reimbursement by type of surgery and anesthesia.

Table 10.

Average Physician Reimbursement and Overall Reimbursement by Type of Surgery and Anesthesia∗

| Procedure | Overall Reimbursement |

Surgeon Reimbursement |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WALA | Standard | P Value | WALA | Standard | P Value | |

| CTR | $1,452.50 | $1,774.48 | < .001 | $514.66 | $472.38 | < .001 |

| TFR | $1,098.60 | $1,579.26 | < .001 | $436.69 | $352.43 | < .001 |

| DQR | $1,235.77 | $1,692.64 | < .001 | $406.96 | $390.81 | .26 |

| Anesthesia | $195.53 | |||||

All dollar values are presented in 2015 US dollars.

Discussion

From 2008 to 2015, use of WALA for CTR, DQR, and TFR increased from 18% to 21%.

Contrary to our hypothesis, WALA surgery was an independent predictor of lower 30-day medical and surgical complication rates in CTR, DQR, and TFR procedures on a population level. Although the WALA group had a lower baseline comorbidity index (ECI) compared with the standard group in this study, the difference in complication rates persisted after controlling for comorbidity index and type of surgery. A possible explanation for this finding may be that surgeons performed more rigorous patient selection before offering WALA surgery. Although the multivariate analysis controlled for comorbidities, other selection factors may not have been adequately captured in the analysis.

Another potential factor contributing to lower complications in WALA surgery, as popularized by Lalonde and Martin,3 is the use of lidocaine with epinephrine, which obviates the need for a tourniquet. Tourniquets have a low but significant complication rate.18 Tourniquet use is associated with a risk for postoperative hematoma, particularly if closure is performed under tourniquet control.19,20 The PearlDiver database does not permit analysis of tourniquet use during procedures; therefore, we are unable to comment on its relation to our findings of lower infection and dehiscence rates in the wide-awake group.

Differences in perioperative antibiotic use may also account for differential surgical complication rates. We did not include antibiotic administration data in the analysis. However, recent literature supports performing minor hand surgery without perioperative antibiotics, because its use has not been associated with lower infection rates.21 Therefore, this is unlikely to be a major confounding factor on the differential surgical complication rates.

The significantly lower medical complication rate after WALA surgery is consistent with prior studies14 and can be attributed to avoiding medical risks for complications from sedation and general anesthesia. Although we controlled for underlying risk factors using ECI, the data suggested a slight selection bias toward healthier patients undergoing WALA surgery. It is possible that a subtle difference in patient selection not adequately controlled for by ECI may have contributed to a difference in complications rates. In addition, although medical complications are rare after minor hand surgery, they certainly occur, as demonstrated in previous literature on the topic.14 Given the large numbers of patients who undergo minor hand procedures annually, a small relative difference may affect a large number of patients.

Regarding opioid prescriptions, WALA patients were less likely to fill an initial prescription, but both groups had equivalent opioid refill rates on multivariate analysis. Moreover, patients in the WALA group were initially prescribed significantly lower quantities of opioids (OMEs) when directly compared with the standard anesthesia group. Although the absolute difference between groups was small (3.4% after CTR) on univariate analysis and may not have a large clinical significance, multivariate analysis showed a clinically significant difference (OR = 0.71; 95% CI, 0.69–0.74). Despite lower initial fill rates, the equivalent refill rates suggest that WALA patients had a lower overall opioid need in the perioperative period. Furthermore, the overall difference in oral morphine equivalents (289 vs 342 OME; P < .001) equated to a difference of 7 fewer tabs of oxycodone 5 mg/patient, and thus significantly fewer opioid pills went into circulation after WALA procedures.

Although these findings may indicate lower postoperative opioid requirements after wide-awake surgery, this may also be related to surgeons’ prescribing practice. Surgeons who routinely use WALA techniques may be more judicious with the amount of opioids and the number of patients to whom they prescribe. Another possible factor is the use of tourniquet, which has been associated with increased intraoperative22 and postoperative pain.23,24 The PearlDiver database does not permit analysis of tourniquet use; nevertheless, there has been a trend to perform WALA procedures without the use of a tourniquet.3 This may contribute to decreased pain and opioid use immediately after surgery.

A limitation of an administrative database analysis is the inability to track prescription rates by providers or to assess patients who were given a prescription but did not fill it. Importantly, we have no way to determine the actual amount of opioids consumed by patients. Nonetheless, others have used these data as a proxy to determine opioid consumption.25,26 Thus, given the current opioid epidemic and concerns regarding new persistent opioid use after surgery,11 WALA techniques are a promising tool in the surgeon’s armamentarium to minimize postoperative opioid prescriptions.

Moreover, WALA techniques were associated with significantly lower overall charges with all types of surgeries and higher surgeon reimbursement in TFR and CTR. This correlates with our hypothesis and published literature that demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of WALA techniques.4, 5, 6 Although the actual difference in insurance reimbursement per case was small, the current data describe only insurance reimbursements and do not precisely capture what individual patients paid, because we cannot account for deductibles and copays. Thus, we cannot extrapolate how much individual patients would be charged if they opted for anesthesia over wide-awake surgery, but for some patients, the sum may be substantial.

Our results demonstrated a small but statistically significant higher surgeon reimbursement with WALA techniques. However, a limitation of the database is that we were unable to identify the true reason for this. It may be because of regional differences or variations in negotiated contract rates among different surgeons and institutions. Although the authors do not advocate choosing anesthetic technique based on surgeon reimbursement, the overall cost savings of WALA techniques cannot be overlooked. Given the increased attention to value-based care and bundled payment models in the American health care system, WALA techniques may lead to cost savings on anesthesia and facility fees, especially considering the high volume of minor hand surgeries performed nationwide. This study reinforces prior findings that WALA is a cost-effective and safe technique for simple hand surgical procedures.4,7

Although a strength of this study is the vast patient population pulled from all regions of the country, there are limitations with a large administrative database. The analysis depends heavily on the accuracy of patient coding. Miscoding does occur; nevertheless, this should only represent a fraction of the current cohort.27 The database allowed access to patient data only between 2007 and 2015, and opioid prescription patterns might have changed over the past 4 years. An additional limitation of this study was its lack of data on procedure location during wide-awake surgery. Although we cannot consistently determine facility location with the PearlDiver database, many advocates for WALA techniques perform the surgeries in the clinic or office.1 This would further contribute to cost savings, but this study was unable to report specifically on office-based procedures.

This study demonstrated that WALA is a viable and increasingly prevalent option for minor hand surgery. It is a safe and cost-effective technique that may be associated with lower postoperative opioid use.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Elodie L. Jungerman for her assistance with a literature review.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests: Igor Immerman received departmental funding from the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University of California San Francisco. No benefits in any form have been received or will be received by the other authors related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

References

- 1.Lalonde D., Bell M., Benoit P., Sparkes G., Denkler K., Chang P. A multicenter prospective study of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective epinephrine use in the fingers and hand: the Dalhousie Project clinical phase. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30(5):1061–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warrender W.J., Lucasti C.J., Ilyas A.M. Wide-awake hand surgery: principles and techniques. JBJS Rev. 2018;6(5):e8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.17.00142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lalonde D., Martin A. Tumescent local anesthesia for hand surgery: improved results, cost effectiveness, and wide-awake patient satisfaction. Arch Plast Surg. 2014;41(4):312–316. doi: 10.5999/aps.2014.41.4.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Codding J.L., Bhat S.B., Ilyas A.M. An economic analysis of hand surgery performed under MAC versus WALANT: a trigger finger release surgery case study. Hand (N Y) 2017;12(4):348–351. doi: 10.1177/1558944716669693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhee P.C., Fischer M.M., Rhee L.S., McMillan H., Johnson A.E. Cost savings and patient experiences of a clinic-based, wide-awake hand surgery program at a military medical center: a critical analysis of the first 100 procedures. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42(3):e139–e147. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazmers N.H., Presson A.P., Xu Y., Howenstein A., Tyser A.R. Cost implications of varying the surgical technique, surgical setting, and anesthesia type for carpal tunnel release surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(11) doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2018.03.051. 971.e1–977.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster B.D., Sivasundaram L., Heckmann N., et al. Surgical approach and anesthetic modality for carpal tunnel release: a nationwide database study with health care cost implications. Hand (N Y) 2017;12(2):162–167. doi: 10.1177/1558944716643276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruxasagulwong S., Kraisarin J., Sananpanich K. Wide awake technique versus local anesthesia with tourniquet application for minor orthopedic hand surgery: a prospective clinical trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 2015;98(1):106–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waljee J.F., Zhong L., Hou H., Sears E., Brummett C., Chung K.C. The use of opioid analgesics following common upper extremity surgical procedures: a national, population-based study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(2):355e–364e. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000475788.52446.7b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute on Drug Abuse Overdose death rates. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates

- 11.Brummett C.M., Waljee J.F., Goesling J., et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6) doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke H., Soneji N., Ko D.T., Yun L., Wijeysundera D.N. Rates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348(3) doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1251. g1251–g1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elixhauser A., Steiner C., Harris D.R., Coffey R.M. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hustedt J.W., Chung A., Bohl D.D., Olmschied N., Edwards S.G. Comparison of postoperative complications associated with anesthetic choice for surgery of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42(1) doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.10.007. 1.e5–8.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Food and Drug Administration Extended-release and long-acting opioid analgesics shared system. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/UCM348818.pdf

- 16.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Opioid oral morphine milligram equivalent (MME) conversion factors. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Opioid-Morphine-EQ-Conversion-Factors-April-2017.pdf

- 17.US Department of Labor Consumer Price Index databases. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

- 18.Oragui E., Parsons A., White T., Longo U.G., Khan W.S. Tourniquet use in upper limb surgery. Hand (N Y) 2011;6(2):165–173. doi: 10.1007/s11552-010-9312-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wakai A., Winter D.C., Street J.T., Redmond P.H. Pneumatic tourniquets in extremity surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9(5):345–351. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200109000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fitzgibbons P.G., Digiovanni C., Hares S., Akelman E. Safe tourniquet use: a review of the evidence. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(5):310–319. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-05-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li K., Sambare T.D., Jiang S.Y., Shearer E.J., Douglass N.P., Kamal R.N. Effectiveness of preoperative antibiotics in preventing surgical site infection after common soft tissue procedures of the hand. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476(4):664–673. doi: 10.1007/s11999.0000000000000073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iqbal H.J., Doorgakant A., Rehmatullah N.N.T., Ramavath A.L., Pidikiti P., Lipscombe S. Pain and outcomes of carpal tunnel release under local anaesthetic with or without a tourniquet: a randomized controlled trial. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2018;43(8):808–812. doi: 10.1177/1753193418778999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu D., Graham D., Gillies K., Gillies R.M. Effects of tourniquet use on quadriceps function and pain in total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2014;26(4):207–213. doi: 10.5792/ksrr.2014.26.4.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunasagaran J., Sean E.S., Shivdas S., Amir S., Ahmad T.S. Perceived comfort during minor hand surgeries with wide awake local anaesthesia no tourniquet (WALANT) versus local anaesthesia (LA)/tourniquet. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2017;25(3) doi: 10.1177/2309499017739499. 2309499017739499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steiner S.R.H., Cancienne J.M., Werner B.C. Narcotics and knee arthroscopy: trends in use and factors associated with prolonged use and postoperative complications. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(6):1931–1939. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pugely A.J., Bedard N.A., Kalakoti P., et al. Opioid use following cervical spine surgery: trends and factors associated with long-term use. Spine J. 2018;18(11):1974–1981. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gologorsky Y., Knightly J.J., Lu Y., Chi J.H., Groff M.W. Improving discharge data fidelity for use in large administrative databases. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;36(6):E2. doi: 10.3171/2014.3.FOCUS1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]