Abstract

Background

The nature and indications for thyroid surgery vary and a perceived risk of haemorrhage post‐surgery is one reason why wound drains are frequently inserted. However when a significant bleed occurs, wound drains may become blocked and the drain does not obviate the need for surgery or meticulous haemostasis. The evidence in support of the use of drains post‐thyroid surgery is unclear therefore and a systematic review of the best available evidence was undertaken.

Objectives

To determine the effects of inserting a wound drain during thyroid surgery, on wound complications, respiratory complications and mortality.

Search methods

We searched the following databases: Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (issue 1, 2007); MEDLINE (2005 to February 2007); EMBASE (2005 to February 2007); CINAHL (2005 to February 2007) using relevant search strategies.

Selection criteria

Only randomised controlled trials were eligible for inclusion. Quasi randomised studies were excluded. Studies with participants undergoing any form of thyroid surgery, irrespective of indications, were eligible for inclusion in this review. Studies involving people undergoing parathyroid surgery and lateral neck dissections were excluded. At least 80% follow up (till discharge) was considered essential.

Data collection and analysis

Studies were assessed for eligibility and data were extracted by two authors independently, differences were resolved by discussion. Studies were assessed for validity including criteria on whether they used a robust method of random sequence generation and allocation concealment. Missing and unclear data were resolved by contacting the study authors.

Main results

13 eligible studies were identified (1646 participants). 11 studies compared drainage with no drainage and found no significant difference in re‐operation rates; incidence of respiratory distress and wound infections. Post‐operative wound collections needing aspiration or drainage were significantly reduced by drains (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.97), but a further analysis of the 4 high quality studies showed no significant difference (RR 1.82, 95% CI 0.51 to 6.46). Hospital stay was significantly prolonged in the drain group (WMD 1.18 days, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.63).

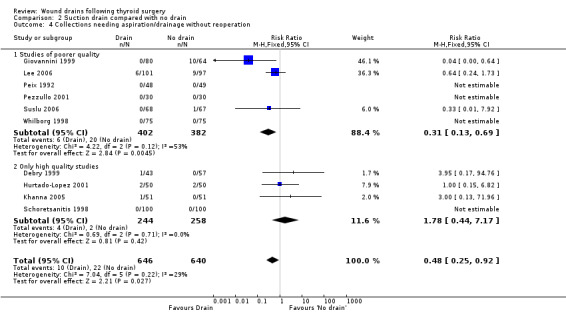

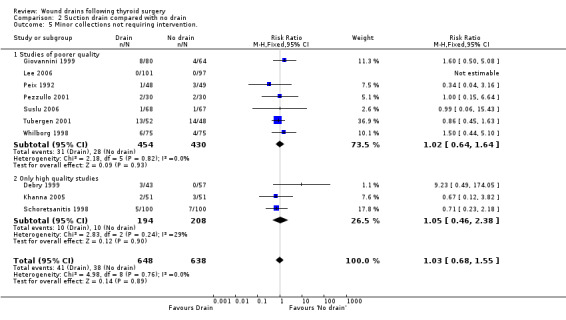

Eleven studies compared suction drain with no drainage and found no significant difference in re‐operation rates; incidence of respiratory distress and wound infection rates. The incidence of collections that required aspiration or drainage without formal re‐operation was significantly less in the drained group (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.92). However, further analysis of only high quality studies showed no significant difference (RR 1.78, 95% CI 0.44 to 7.17). Hospital stay was significantly prolonged in the drain group (WMD 1.20 days, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.63).

One study compared open drain with no drain. No participant in either group required re‐operation. No data were available regarding the incidence of respiratory distress, wound infection and pain. The incidence of collections needing aspiration or drainage without re‐operation was not significantly different between the groups and there was no significant difference in length of hospital stay. One study compared suction drainage with passive closed drainage. None of the participants in the study needed re‐operation and data regarding other outcomes were not available. Two studies (180 participants) compared open drainage with suction drainage. One study reported wound infections and minor wound collections, both were not significantly different. The other study reported wound collections requiring intervention and hospital stay; both were not significantly different. None of the participants in either study required re‐operation. Data regarding other outcomes were not available.

Authors' conclusions

There is no clear evidence that using drains in patients undergoing thyroid operations significantly improves patient outcomes and drains may be associated with an increased length of hospital stay. The existing evidence is from trials involving patients having goitres without mediastinal extension, normal coagulation indices and the operation not involving any lateral neck dissection for lymphadenectomy.

Plain language summary

Drains are often used after thyroid operations.

People who undergo thyroid surgery are thought to be at risk of respiratory distress, wound infections, excessive fluid accumulation and increased stay in hospital stay. Concerns about these complications lead surgeons to insert drains after the procedure. This review found no evidence of benefit in the use of drains for improving patient outcomes, but their use may be associated with an increased length of hospital stay.

Background

The prevalence of thyroid swellings (goitre) as measured either by palpation or ultrasound varies between 9.8% to 51.3% depending on age, sex (more common in females) and prevalence of iodine deficiency (Brander 1991; Knudsen 2000; Riehl 1995; Teng 2002). This may be due to benign conditions such as cyst, adenoma or iodine deficiency. Occasionally cancer of the thyroid can present as a goitre. A combination of clinical examination and investigations can assist in diagnosis. However removal of the goitre by surgery (thyroidectomy) is frequently used to achieve a definitive diagnosis. Goitres are also removed for cosmetic reasons. About 8,500 thyroid operations were done in England in the financial year ending 2006 (HES 2006). Benign diseases confined to one lobe such as cysts or adenoma are treated by hemi‐thyroidectomy which consists of the removal of one lobe with the adjacent isthmus (Farquharson 2005). The extent of thyroid surgery varies depending on indication and the experience of the surgeon (Affleck 2003). A sub‐total thyroidectomy is the removal of most of the anterior thyroid tissue leaving behind a posterior cuff of thyroid tissue (Shaheen 1997) and is generally undertaken for benign indications such as Grave's disease and multinodular goitre. The amount of thyroid tissue left behind varies (Affleck 2003; Scott‐Coombes 2005; Shaheen 1997). A total thyroidectomy is the complete removal of the thyroid gland, whereas in near‐total thyroidectomy about 2 to 4 gm of thyroid tissue is left behind (Affleck 2003). Near‐total and total thyroidectomy are usually recommended for malignant thyroid disease (Dackiw 2004; Scott‐Coombes 2005). However increasingly both these operations are being proposed for benign indications as well (Friguglietti 2003; Rios 2005).

Minimally Invasive Video Assisted Thyroidectomy (MIVAT) is a specialised technique which involves using special instruments to perform the thyroidectomy operation through a small incision. A video camera inserted through the incision displays the operative field on a monitor while the surgery is performed using special instruments. The main advantage is improved aesthetic appearance of the wound (Miccoli 2004). The indications and controversies are outside the scope of this review.

People undergoing thyroid surgery are regarded as being particularly at risk of haematoma formation and consequent respiratory distress however the need for re‐operation for haematoma varies between zero and 1.5% (Abbas 2001; Ardito 1999; Daou 1997; Palestini 2005Shaha 1994). Most thyroid surgeons use drains postoperatively (Willy 1998) despite the low incidence of haematoma.

There are however strong arguments against the use of wound drains after thyroid surgery; they often become blocked by clotted blood (Ernst 1997) and collections of blood or tissue fluid (seroma) can occur in spite of drains (Debry 1999; Hurtado‐Lopez 2001; Shaha 1993) In addition airway compromise can occur due to other causes such as nerve injury, laryngeal oedema (Hurtado‐Lopez 2002; Mannell 1989; Martis 1971) and inadvertent leakage of local anaesthetic onto the recurrent laryngeal nerves either by drains or during infiltration (Coress 2005). Drains inserted in the peritoneal cavity have been shown to cause microscopic irritation (Ernst 1997), and there is the potential for injury during insertion of the drain. Using drains can increase costs by prolonging hospital stay (Peix 1992; Schoretsanitis 1998; Tubergen 2001). Drains can increase the infection rate (Karayacin 1997; Tabaqchali 1999) and are associated with increased pain (Debry 1999). Drain usage has been questioned in other areas such as colorectal (Urbach 1999), plastic surgery (Collis 2005), vascular (Healy 1989) and orthopaedics (Parker 2001). The duration of drainage varies; the drain is either removed once it ceases to drain below a critical level (Ayyash 1991) or after a fixed duration (Khanna 2005). This again may prolong hospital stay.

Once post operative wound collection occurs, the options are continued observation in the hope of gradual spontaneous resolution, needle aspiration and evacuation of wound collection under local or general anaesthesia. Collections which occur in the immediate post operative period are due to continued or delayed bleeding into wound. At this stage usually surgical intervention is required unless the bleeding is minimal. Later in the post operative course, tissue fluid can collect in the operated area and give rise to seroma. This can be aspirated with a needle or observed without any intervention. It is not clear whether drains decrease the incidence of either type of collections.

The nature of the drain used varies and surgical drains may be either open or closed. An open drain is when an artificial conduit is left in the wound to allow drainage of fluids to the exterior (outside the body), (examples of these are corrugated drain, Penrose drain and Yeates drain). A drain is said to be closed when an artificial conduit is left in the wound to allow drainage of fluids into a closed container. Suction may be applied by a closed drain (e.g. the Redon drain) or a closed drain may be passive (e.g. the Robinson drain). The use of any particular drain (open or closed) is based on surgeon preference.

Thyroid operations are classified as clean operations and are associated with low infection rates (Pino 2004; Rosato 2004). Hence prophylactic antibiotic use is not recommended (SIGN 2006), though it is used frequently (Huang 2005). Postoperative infections may still occur even when antibiotics are used and the wound drain has been identified as a possible source (De Salvo 1998). Drains represent one of the risk factors in the development of nosocomial infections (Coello 1997; Soleto 2003) which are one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in developing countries (Okeke 2005)

In this review we seek to review the evidence regarding the use of drains in thyroid surgery.

Objectives

Primary objective To determine the effects of inserting a wound drain during thyroid surgery, on haematoma and seroma formation, respiratory distress, wound infection, hospital stay, pain, complications and mortality.

Secondary objective To determine the effects of different types of wound drain after thyroid surgery on the incidence of haematoma, seroma formation, respiratory distress, wound infection, hospital stay, pain and complications.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Only randomised clinical trials (RCTs) were included in this review. Quasi‐randomised trials in which there was inadequate generation of allocation sequence, for example, date of birth, hospital record number, alternation were excluded. Only studies with at least 80 percent follow up were included.

Types of participants

RCTs involving adults (greater than 18 years) undergoing any type of thyroid surgery (hemithyroidectomy, subtotal thyroidectomy, near total thyroidectomy. total thyroidectomy, MIVAT Minimally Invasive Video Assisted Thyroidectomy) irrespective of indication were included. Thyroid or parathyroid surgeries performed for parathyroid disorders were excluded since parathyroid surgery may involve varied and extensive amount of dissection depending on location of the parathyroid adenoma (Fredrickson 1998). Lateral neck dissections (for lymphadenectomy in cancers) were excluded as these are more extensive operations and drains are necessary in this situation (Gavilán 2002).

Types of interventions

Studies reporting the following comparisons were eligible:

Wound drainage compared with no wound drainage after thyroid surgery;

One type of wound drain compared with another type of wound drain after thyroid surgery.

Types of outcome measures

For the purposes of this review the following outcomes will be reported :

Primary outcome measure

Secondary outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Incidence of respiratory distress;

Rates of re‐operation for respiratory distress;

Rates of re‐operation for haematoma/ seroma;

Mortality.

Secondary outcomes

Rates of wound haematoma, seroma, however defined or treated;

Rates of wound infection, however defined. Where study authors have used the CDC criteria and classification of surgical site infection (Horan 1992), we planned to report the rates of superficial and deep infections separately;

Length of hospital stay;

Pain however defined and measured by authors;

Complications associated with the use of the drain for example, drain migration and injury to internal organs; problems with drain removal, for example, drain retention.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the following databases:

Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register (Searched 1/3/07)

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) ‐ The Cochrane Library Issue 1, 2007

Ovid MEDLINE ‐ 2005 to February Week 2 2007

Ovid EMBASE ‐ 2005 to 2007 Week 08

Ovid CINAHL ‐ 2005 to February Week 3 2007

The CENTRAL search strategy was adapted to search MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL. The Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying reports of randomized controlled trials was used in MEDLINE (Higgins 2005) and the EMBASE and CINAHL searches were combined with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) .

The following strategy was used to search CENTRAL: 1 MeSH descriptor Thyroid Gland explode all trees 2 MeSH descriptor Thyroid Neoplasms explode all trees 3 MeSH descriptor Thyroidectomy explode all trees 4 MeSH descriptor Graves Disease explode all trees 5 MeSH descriptor Goiter explode all trees 6 MeSH descriptor Hyperthyroidism explode all trees 7 (thyroid or thyroidectom* or hemithyroidectom* or hyperthyroid* or "graves disease" or goitre*):ti,ab,kw 8 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7) 9 MeSH descriptor Drainage explode all trees 10 MeSH descriptor Suction explode all trees 11 MeSH descriptor Catheterization explode all trees 12 (drain or drains or drainage or catheter$):ti,ab,kw 13 (#9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12) 14 (#8 AND #13)

Equivalent search strategies were used for other databases (Table 1). We considered all relevant studies irrespective of language and publication status for the review. References in identified studies were also searched for identifying further studies. We contacted experts in the field and major manufacturers of drains to identify any ongoing or completed trials.

1. Search Strategy.

| Database | Strategy |

| Ovid MEDLINE | 1 exp Thyroid Gland/ 2 exp Thyroid Neoplasms/ 3 exp Thyroidectomy/ 4 exp Graves Disease/ 5 exp Goiter/ 6 exp Hyperthyroidism/ 7 (thyroid or thyroidectom$ or hemithyroidectom$ or hyperthyroid$ or graves disease or goitre$).ti,ab. 8 or/1‐7 9 exp Drainage/ 10 exp Suction/ 11 exp Catheterization/ 12 (drain$1 or drainage or catheter$).ti,ab. 13 or/9‐12 14 8 and 13 15 RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL.pt. 16 CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL.pt. 17 RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS.sh. 18 RANDOM ALLOCATION.sh. 19 DOUBLE BLIND METHOD.sh. 20 SINGLE‐BLIND METHOD.sh. 21 or/15‐20 22 Animals/ 23 Humans/ 24 22 not 23 25 21 not 24 26 CLINICAL TRIAL.pt. 27 exp Clinical Trials/ 28 (clin$ adj25 trial$).ti,ab. 29 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab. 30 PLACEBOS.sh. 31 placebo$.ti,ab. 32 random$.ti,ab. 33 or/26‐32 34 33 not 24 35 25 or 34 36 14 and 35 |

| Ovid EMBASE | 1 exp Thyroid Gland/ 2 exp Thyroid Cancer/ 3 exp Thyroidectomy/ 4 exp Graves Disease/ 5 exp Goiter/ 6 exp Hyperthyroidism/ 7 (thyroid or thyroidectom$ or hemithyroidectom$ or hyperthyroid$ or graves disease or goitre$).ti,ab. 8 or/1‐7 9 exp drain/ 10 exp surgical drainage/ 11 exp catheter/ 12 (drain$1 or drainage or catheter$).ti,ab. 13 or/9‐12 14 8 and 13 15 exp Clinical trial/ 16 Randomized controlled trial/ 17 Randomization/ 18 Single blind procedure/ 19 Double blind procedure/ 20 Crossover procedure/ 21 Placebo/ 22 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. 23 RCT.tw. 24 Random allocation.tw. 25 Randomly allocated.tw. 26 Allocated randomly.tw. 27 (allocated adj2 random).tw. 28 Single blind$.tw. 29 Double blind$.tw. 30 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. 31 Placebo$.tw. 32 Prospective study/ 33 or/15‐32 34 Case study/ 35 Case report.tw. 36 Abstract report/ or letter/ 37 or/34‐36 38 33 not 37 39 animal/ 40 human/ 41 39 not 40 42 38 not 41 43 14 and 42 |

| WIS Online CENTRAL | 1 MeSH descriptor Thyroid Gland explode all trees 2 MeSH descriptor Thyroid Neoplasms explode all trees 3 MeSH descriptor Thyroidectomy explode all trees 4 MeSH descriptor Graves Disease explode all trees 5 MeSH descriptor Goiter explode all trees 6 MeSH descriptor Hyperthyroidism explode all trees 7 (thyroid or thyroidectom* or hemithyroidectom* or hyperthyroid* or “graves disease” or goitre*):ti,ab,kw 8 (1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4 OR 5 OR 6 OR 7) 9 MeSH descriptor Drainage explode all trees 10 MeSH descriptor Suction explode all trees 11 MeSH descriptor Catheterization explode all trees 12 (drain or drains or drainage or catheter$):ti,ab,kw 13 (9 OR 10 OR 11 OR 12) 14 (8 AND 13) |

| Ovid CINAHL | 1 exp Thyroid Gland/ 2 exp Thyroid Neoplasms/ 3 exp Thyroidectomy/ 4 exp Graves Disease/ 5 exp Goiter/ 6 exp Hyperthyroidism/ 7 (thyroid or thyroidectom$ or hemithyroidectom$ or hyperthyroid$ or graves disease or goitre$).ti,ab. 8 or/1‐7 9 exp Drainage/ 10 exp Suction/ 11 exp Catheterization/ 12 exp Catheters/ 13 (drain$1 or drainage or catheter$).ti,ab. 14 or/9‐13 15 8 and 14 16 exp clinical trials/ 17 Clinical trial.pt. 18 (clinic$ adj trial$1).tw. 19 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. 20 Randomi?ed control$ trial$.tw. 21 Random assignment/ 22 Random$ allocat$.tw. 23 Allocat$ random$.tw. 24 Placebos/ 25 placebo$.tw. 26 or/16‐25 27 15 and 26 |

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors independently assessed the titles and abstracts of the identified studies. We obtained full text articles for all studies which potentially satisfied the inclusion criteria and included those that met the inclusion criteria. Any differences (between authors) at this stage were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Both authors independently extracted the data described below using a custom data extraction form and independently assessed the methodological quality of each trial, without masking for study author names.

Language of publication

Country where study conducted

Ethical review

Informed consent

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Baseline characteristics of participants by group

Preoperative antibiotic use

Type of operation (unilateral, bilateral)

Inclusion of re‐operative thyroid surgery

Type of intervention (type of drain)

Details of the comparison

Co‐interventions (by group)

Mean duration of drain use

Mean volume drained

Duration of follow up

Outcomes (by group): rates of haematoma and/ or seroma; respiratory distress; infection; length of hospital stay; mortality; pain; other complications.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Assessment of primary study validity was based on guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2005; Moher 1998). Due to the risk of overestimation of intervention effects in randomised trials with inadequate methodological quality (Kjaergard 2001; Moher 1998; Schulz 1995) we looked at the influence of methodological quality of the trials, on the trial results by evaluating the reported randomisation and follow‐up procedures in each trial. If information was not available in the published study, we contacted the study authors in order to assess the trials correctly.

The main validity criteria were the assessment of generation of allocation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding and extent of follow‐up. Pre specified subgroup analyses of high quality studies were done. (1) Generation of the allocation sequence ·Adequate (A), if the allocation sequence was generated by a computer or random number table. Drawing of lots, tossing of a coin, shuffling of cards, or throwing dice will be considered as adequate if a person who was not otherwise involved in the recruitment of participants performed the procedure. ·Unclear (B), if the trial was described as randomised, but the method used for the allocation sequence generation was not described. (The authors were contacted and attempts were made to find out the allocation method). ·Inadequate (C), if a system involving dates, names, or admittance numbers were used for the allocation of patients. These studies are known as quasi‐randomised, will be excluded from the review.

(2) Allocation concealment ·Adequate (A), if the allocation of patients involved a central independent unit, on‐site locked computer, or sealed envelopes. ·Unclear (B), if the trial was described as randomised, but the method used to conceal the allocation was not described. ·Inadequate (C), if the allocation sequence was known to the investigators who assigned participants or if the study was quasi‐randomised.

(3) Blinding of participant ·Adequate (A), if the participant was described as blinded and the method of blinding was described. ·Unclear (B), if the participant was described as blinded, but the method of blinding was not described. ·Not performed (C), if there was no blinding at all.

(4) Blinding of care‐provider ·Adequate (A), if the care provider was described as blinded and the method of blinding was described. ·Unclear (B), if the care provider was described as blinded, but the method of blinding was not described. ·Not performed (C), if there was no blinding at all. We are well aware that it would be difficult to blind the patients as well as the surgeons and do not expect many studies with blinding.

(5) Blinding of outcome assessor ·Adequate (A), if the outcome assessor was described as blinded and the method of blinding was described. ·Unclear (B), if the outcome assessor was described as blinded, but the method of blinding was not described. ·Not performed (C), if there was no blinding at all.

(6) Follow‐up ·Adequate (A), if the numbers and reasons for dropouts and withdrawals in all intervention groups were described or if it was specified that there were no dropouts or withdrawals. ·Unclear (B), if the report gave the impression that there had been no dropouts or withdrawals, but this was not specifically stated. ·Inadequate (C), if the number or reasons for dropouts and withdrawals were not described.

(7) Intention to treat analysis (Hollis 1999) Adequate (A) if clearly mentioned in methods and analysis performed on an intention to treat basis. Unclear (B) if not mentioned but implied in the analysis Inadequate (C) if analysis was not performed on an intention to treat basis. Intent to treat means that participants were analysed in the groups to which they were originally randomised. However if the intervention was changed at the time of the thyroid operation due to surgeon preference, then this was regarded as a major protocol violation and such trials were excluded.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the study authors for any unclear or missing information. If there was any doubt whether the studies shared the same patients ‐ completely or partially (by identifying common study authors and centres), we contacted the authors of the studies to clarify whether the study had been duplicated. Differences (between authors) were resolved by discussion.

Assessment of reporting biases

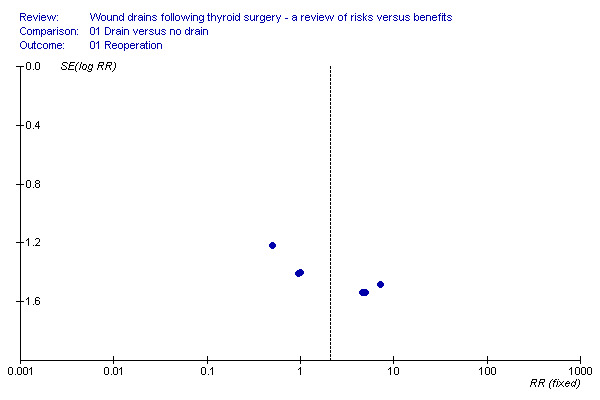

We used a funnel plot to explore publication bias (Egger 1997; Macaskill 2001).

Data synthesis

We performed the meta‐analyses according to the recommendations of The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2005). We used the software package RevMan 4.2 provided by The Cochrane Collaboration. For dichotomous variables, we calculated the relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). We used a random effects model (DerSimonian 1986) and a fixed effect model (DeMets 1987). We estimated the quantity of heterogeneity I2 (Higgins 2002). In the presence of significant heterogeneity (I2 greater than 50%), we reported the random effects model, otherwise, we reported the fixed effect model. The trials were similar enough for an overall summary to be meaningful, hence we performed meta‐analysis for all the outcomes where suitable data were available. We used an intention to treat analysis, when possible. (Hollis 1999). If trials did not report an ITT analysis we adopted 'available case analysis' (that is, use the data available from the reports/ communication with the study authors) and did not impute any missing data for any of the outcomes.

We performed pre‐specified subgroup analyses to explore the effects of aspects of methodological quality in order to compare the intervention effect in trials with adequate methodological quality to that in trials with unclear or inadequate methodological quality. Definition of a trial with adequate methodological quality was a trial which scored 'A" for all quality criteria except for blinding of participant and care provider (which would be difficult to achieve in practice). There is a possibility of bias (with respect to operating technique, surgeon and equipment used) if allocation was revealed anytime before insertion of drain hence we performed a subgroup analysis of trials where concealment of allocation was maintained right up to insertion of drain (i.e. just before closure of wound). There were insufficient studies to do a subgroup analysis of studies which included unilateral (hemithyroidectomy) operations only and those which included bilateral operations only (sub‐total, near‐total and total thyroidectomies). Another subgroup analysis, excluding trials containing re‐operative thyroid surgeries, was not feasible due to insufficient number of studies. Antibiotic usage could not be analysed separately due to lack of sufficient studies.

Results

Description of studies

42 references were identified by the search. Of these, 15 were prospective, randomised trials, 4 were duplicate references, and the rest were either clearly irrelevant or did not fulfil the criteria for a prospective randomised trial. One reference was identified by searching citations in included studies, however we were unable to obtain data from this study (Mok 1992). A total of 13 randomised trials met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review; two trials which included parathyroid operations were excluded from the review (Ayyash 1991; Kristoffersson 1986). The studies originated from several countries as follows: three from Italy, two from France, two from Germany, one from India, one from Korea, one from Greece, one from Turkey, one from Sweden and one from Mexico.

Details of participant ages was available in seven studies (De Salvo 1998; Hurtado‐Lopez 2001; Khanna 2005; Lee 2006; Schwarz 1996; Tubergen 2001; Whilborg 1998) and ranged from 8 to 88 years. Three studies (Hurtado‐Lopez 2001; Khanna 2005; Whilborg 1998) included people aged less than 18 years. Information about age was not available from the remainder (Debry 1999; Giovannini 1999; Peix 1992; Pezzullo 2001; Schoretsanitis 1998; Suslu 2006). Some of the participants were less than 18 years of age, which was outside the prespecified range for inclusion. Individual data for these participants aged less than 18 years were not available. The mean or median age of the participants was available and ranged from 34.6 (Khanna 2005) to 52 years (Schoretsanitis 1998). The number of participants younger than 18 years, was considered to be small, hence a post hoc decision was made to include the trials. Majority of participants were female ranging from 60.5% (Schoretsanitis 1998) to 87.8% (Lee 2006) of the participants. Sample sizes ranged from 60 (Pezzullo 2001) to 200 (Schoretsanitis 1998).

Eleven studies (Debry 1999; Giovannini 1999; Hurtado‐Lopez 2001; Khanna 2005; Lee 2006;Peix 1992; Pezzullo 2001; Schoretsanitis 1998; Suslu 2006; Tubergen 2001; Whilborg 1998) compared drains (different types) with no drain; two studies compared closed suction with open drain (De Salvo 1998; Hurtado‐Lopez 2001); one study compared closed suction with passive closed drain (Willy 1998). One study had three study arms, viz. no drain, passive drain (Penrose) and suction drain (Hurtado‐Lopez 2001) and hence four comparisons were possible. Antibiotics were used preoperatively in two studies. The antibiotics used were Ciprofloxacin (Willy 1998) and Sefazol Sodium (Suslu 2006). Antibiotics were not used in two studies (Debry 1999; Schoretsanitis 1998) and information was not available from the remaining studies. Duration of drain use was not available in four studies (Debry 1999; Pezzullo 2001; Suslu 2006; Whilborg 1998). In the remainder the drain was removed after 20 to 48 hours. All studies assessed presence or absence of wound collections (fluid accumulation) clinically, though there was no formal definition in any of the studies. Three studies (Khanna 2005; Tubergen 2001; Willy 1998) compared mean volume of fluid in the operated area, by assessment with ultrasound. We intended to measure seroma and haematoma rates separately, however, these data were not always clear, especially in the 'no drain' group, where confirmation was not possible. Hence we used rates of postoperative wound collection (seroma or haematoma) as a single outcome.

All studies had a mixture of unilateral and bilateral operations except for two studies, one of which included only bilateral subtotal thyroidectomies (Willy 1998) and the other only unilateral lobectomies (Peix 1992). Thyroid re‐operations were included in two studies (Debry 1999; Khanna 2005), excluded in two studies ( Peix 1992; Willy 1998) and no information available from remaining nine studies. All studies excluded patients who needed cervical neck dissection except one (Lee 2006) which included patients who underwent central neck dissection, but not requiring lateral neck dissection, in addition to thyroidectomy. All studies excluded patients with coagulation disorders except three (Schoretsanitis 1998; Tubergen 2001; Whilborg 1998) where this exclusion criteria was not specified.

Risk of bias in included studies

The way in which the random sequences were generated was unclear in 7 studies (De Salvo 1998; Giovannini 1999; Peix 1992; Pezzullo 2001; Suslu 2006; Tubergen 2001; Whilborg 1998) and adequate in six. Two studies used computer generated randomisation sequence (Khanna 2005; Schoretsanitis 1998) and four reported the use of random number tables (Debry 1999; Hurtado‐Lopez 2001; Lee 2006; Willy 1998).

The extent of allocation concealment was unclear in 5 studies (De Salvo 1998; Giovannini 1999; Lee 2006; Suslu 2006; Whilborg 1998), inadequate in one (Willy 1998) and adequate in 7 studies (Debry 1999; Hurtado‐Lopez 2001; Khanna 2005; Peix 1992; Pezzullo 2001; Schoretsanitis 1998; Tubergen 2001).

None of the studies reported blinding of either care provider or study participants. Assessor blinding was conducted in only one study (Peix 1992). Follow up was adequate in all studies, with data available for all patients up to discharge. There were no dropouts or people crossed over to the alternative intervention in any of the trials. All studies did an intention to treat analysis, though it was not specifically stated. None of the studies reported sample size calculations.

There were four high quality studies (Debry 1999; Hurtado‐Lopez 2001; Khanna 2005; Schoretsanitis 1998) which met the criteria in that they scored 'A' for all quality criteria except for blinding of participant and care provider (which would be difficult to achieve in practice).

Effects of interventions

None of the studies reported any mortality. The following comparisons were made.

1. Drain compared with no drain (11 studies, 1436 participants)

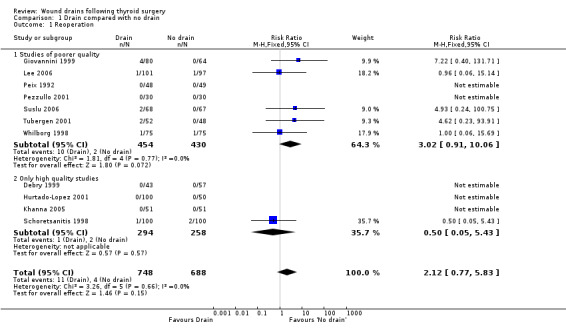

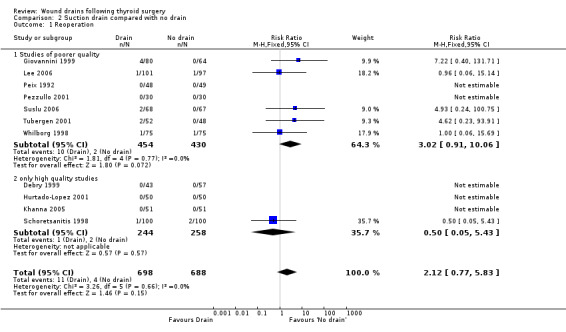

Rates of reoperation: The rate of reoperation was low (11/748 in drain group and 4/688 in 'no drain' group). The need for re‐operation was not significantly different between the two groups (11 studies, 1436 participants; relative risk (RR) 2.12, 95% CI 0.77 to 5.83; I2 =0%)(Analysis 01, outcome 01). Further subgroup analysis of only high quality studies (Debry 1999; Hurtado‐Lopez 2001; Khanna 2005; Schoretsanitis 1998), showed no significant difference between the groups (RR 0.5, 95%CI 0.05 to 5.43).

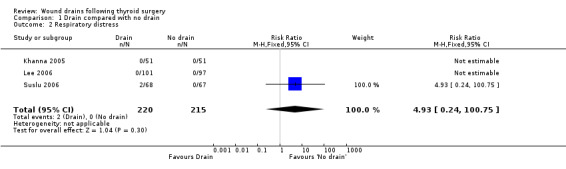

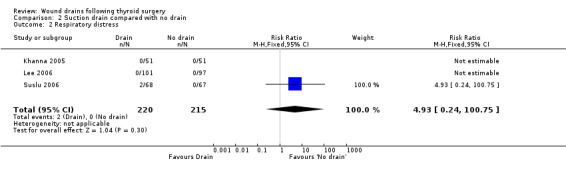

Rates of respiratory distress: The occurrence of respiratory distress was low (2/220 in 'drain group' and none amongst 215 in 'no drain' group). The incidence of respiratory distress was not significantly different between the two groups (435 participants from three studies, RR 4.93, 95% CI 0.24 to 100.75, I2 not applicable) )(Analysis 01, outcome 02). There was only one high quality study (Khanna 2005) and no‐one developed respiratory distress in this trial.

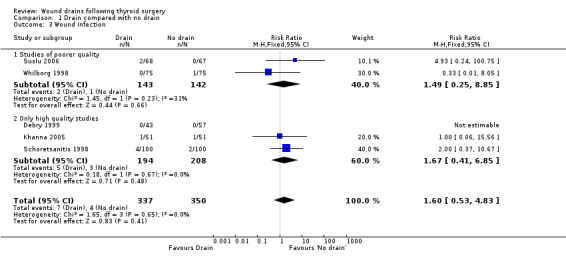

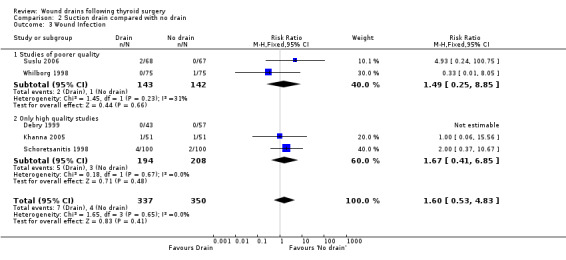

Rates of wound infection: There was no significant difference in the incidence of wound infection between the drained and undrained groups (687 participants from five studies, RR 1.60, 95% CI 0.53 to 4.83; I2 =0%)(Analysis 01, outcome 03). Further analysis of data from high quality trials (Debry 1999; Khanna 2005; Schoretsanitis 1998) showed no significant difference (RR 1.67, 95% CI 0.41 to 6.85; I2 = 0%).

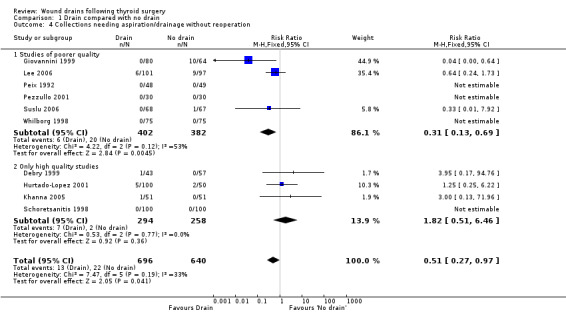

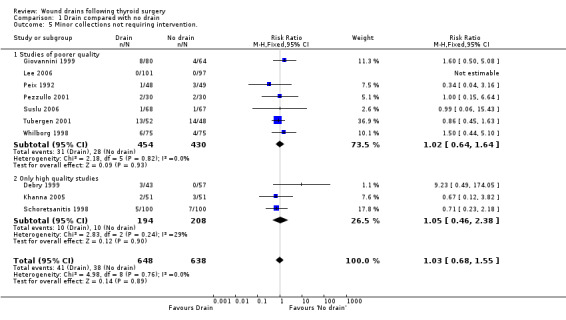

Wound collections (fluid accumulation): The incidence of collections that required aspiration or drainage without formal re‐operation was significantly lower (p=0.04) in the drained group (ten studies with 1336 participants RR (fixed) 0.51, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.97; I2 =33.1%)(Analysis 01, outcome 04). However a further subgroup analysis of only high quality studies (Debry 1999; Hurtado‐Lopez 2001; Khanna 2005; Schoretsanitis 1998) showed no significant difference (RR 1.82, 95% CI 0.51 to 6.46; I2= 0%). There was no significant difference in the rate of minor collections not needing any intervention (ten studies with 1286 participants; RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.55; I2 = 0%)(Analysis 01, outcome 05). A further subgroup analysis of only high quality studies (Debry 1999; Khanna 2005; Schoretsanitis 1998) showed no significant difference between the groups (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.46 to 2.38; I2 = 29.3%).

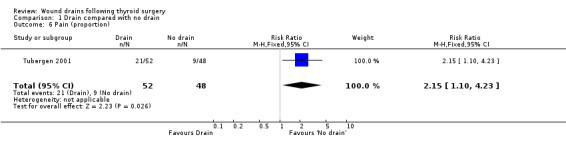

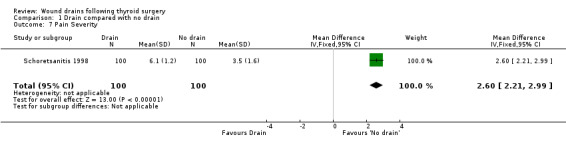

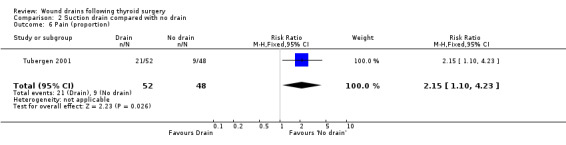

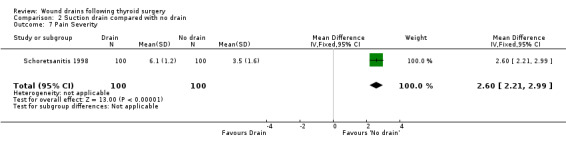

Pain: One study (Tubergen 2001) with 100 participants, assessed the proportion of patients complaining of pain in the operated area. Pain severity was measured using visual analogue scale ranging from zero to ten and there were significantly more patients with pain in the drained group (RR 2.15, 95% CI 1.10 to 4.23)(Analysis 01, outcome 06). In a high quality study with 200 participants, Schoretsanitis 1998 reported significantly more intensity of pain in the drain group (WMD 2.60, 95% CI 2.21 to 2.99)(Analysis 01, outcome 07). Due to differences in assessment and reporting these two studies could not be combined.

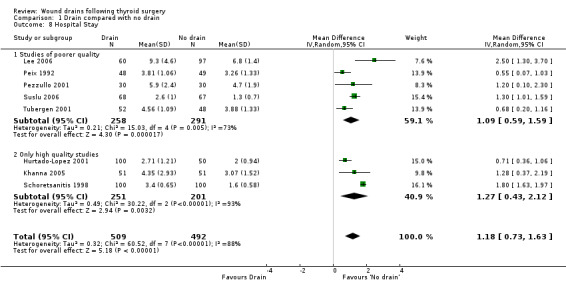

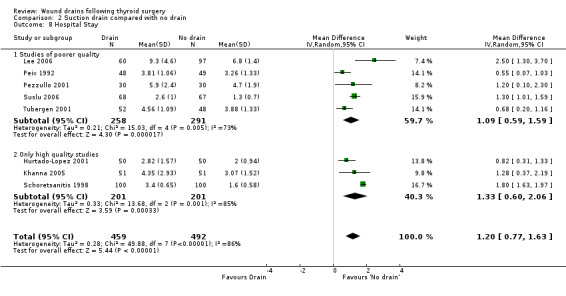

Length of Hospital stay : As heterogeneity was greater than 50%, data were analysed using a random effects model, which showed significantly prolonged hospital stay in the drained group (eight studies with 1001 participants, WMD 1.18 days, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.63; I2=88.4%)(Analysis 01, outcome 8). A further subgroup analysis of only high quality studies (Hurtado‐Lopez 2001; Khanna 2005; Schoretsanitis 1998) confirmed significantly shortened hospital stay (P < .003) for patients without drain (RR 1.27, 95% CI 0.43 to 2.12, I2 = 93.4 %) with random effects model.

2. Suction drain compared with no drain (11 studies, 1386 participants)

Rates of re‐operation: The rates of reoperation were low (11/698 in suction drain group and 4/688 in 'no drain' group). There was no significant difference in re‐operation rates between 'suction drain' and 'no drain' groups (1386 participants from 11 studies, RR 2.12, 95% CI 0.77 to 5.83; I2 = 0%)(Analysis 02, outcome 01). A subgroup analysis of high quality trials (Debry 1999; Hurtado‐Lopez 2001; Khanna 2005; Schoretsanitis 1998) showed no significant difference between the groups (RR 0.5, 95% CI 0.05 to 5.43; I2 = not applicable).

Rates of respiratory distress: The occurrence of respiratory distress was low (2/220 and none amongst 215) and there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (three studies with 435 participants, RR 4.93, 95% CI 0.24 to 100.75; I2 = not applicable)(Analysis 02, outcome 02). One high quality trial (Khanna 2005) reported that no people in this trial had respiratory distress.

Rates of wound infection: Rates of wound infection were not significantly different between the groups (687 participants from five studies, RR 1.60, 95% CI 0.53 to 4.83; I2 =0)(Analysis 02, outcome 03). Subgroup analysis of high quality studies (Debry 1999; Khanna 2005; Schoretsanitis 1998) confirmed the same findings (RR 1.67, 95% CI 0.41 to 6.85; I2 = 0).

Wound collections (fluid accumulation): The incidence of collections that required aspiration or drainage without formal reoperation was significantly less in the drained group (ten studies involving 1286 participants, RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.92; I2 = 29%)(Analysis 02, outcome 04). A further subgroup analysis of only high quality studies (Debry 1999; Hurtado‐Lopez 2001; Khanna 2005; Schoretsanitis 1998) showed no significant difference (RR 1.78, 95% CI 0.44 to 7.17; I2 = 0%). Minor collections not requiring intervention showed no significant differences between the groups (ten studies with 1286 participants, RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.55; I2 = 0%)(Analysis 02, outcome 05). A subgroup analysis of high quality trials (Debry 1999; Hurtado‐Lopez 2001; Khanna 2005; Schoretsanitis 1998) showed no significant difference (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.46 to 2.38; I2= 29.3%).

Pain: One study (Tubergen 2001) reported proportion of patients, with pain at operated site at discharge. The study found more patients with pain in the drain group (RR 2.15 95% CI 1.10 to 4.23) (Analysis 02, outcome 06). Another study (Schoretsanitis 1998) reported pain intensity using visual analogue scale ranging from zero to ten. Pain score was significantly higher for patients in the drain group in this high quality trial (100 participants, 95% CI 1.10 to 4.23)(Analysis 02, outcome 07). The assessment and reporting of pain was different in these two studies and could not be combined.

Length of Hospital stay: Data showed significant heterogeneity, and analysis using a random effects model showed significantly prolonged hospital stay when a drain was used (eight studies with 951 participants, WMD 1.20, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.63; I2 = 86%)(Analysis 02, outcome 08). A subgroup analysis of high quality trials (Hurtado‐Lopez 2001; Khanna 2005; Schoretsanitis 1998) again showed significantly prolonged hospital stay when a drain was used (WMD 1.33, 95% CI 0.60 to 2.06; I2 = 85.4%).

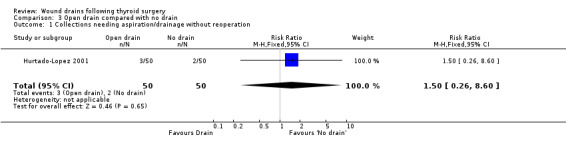

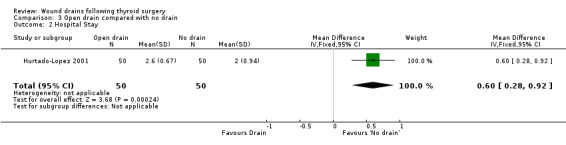

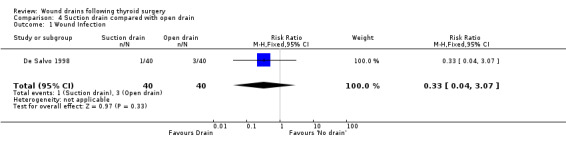

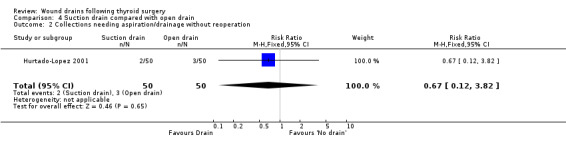

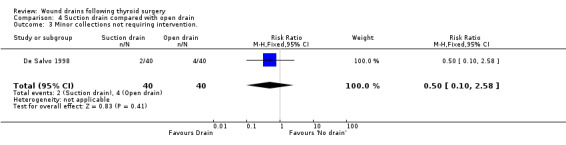

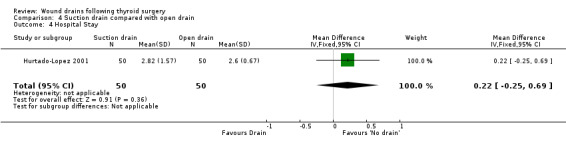

3. Open drain compared with no drain One study was found (Hurtado‐Lopez 2001) which had three comparison arms. For this comparison data reported for the open drain (Penrose drain) was compared with data reported for the no drain group (50 participants in each group). No patient in either group required reoperation and no data were available regarding the incidence of respiratory distress, wound infection and pain. The incidence of collections needing aspiration or drainage without re‐operation was not significantly different between the groups (RR 1.5, 95% CI 0.26 to 8.60)(Analysis 03, outcome 01). There was no data on the incidence of minor collections not needing any intervention. There was a significant difference in length of hospital stay with the group having a drain inserted staying longer in hospital (WMD 0.6 days, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.92)(Analysis 03, outcome 02). 4. Suction drain compared with passive closed drain One study with 80 participants was found (Willy 1998). No patient required reoperation in either group. There was no significant difference in the median volume of the residual fluid in the wound, between using suction drain (median volume 5.3 ml, range 0.6‐24.9 ml) and passive closed drain (median 4.4 ml, range 0‐21.7 ml). The volumes were assessed by ultrasound. No data were specifically available for incidence of respiratory distress, wound infection, pain, wound collections (as assessed clinically) and hospital stay. 5. Suction drain compared with open drain Two studies (De Salvo 1998; Hurtado‐Lopez 2001) with 180 participants compared suction drainage with open drainage. One study (De Salvo 1998) reported wound infections (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.04 to 3.07; Analysis 04, outcome 01) and minor wound collections (RR 0.5, 95%CI 0.10 to 2.58; Analysis 04, outcome 03). Both were not significantly different. The other study (Hurtado‐Lopez 2001) reported wound collections requiring intervention (RR 0.67, 95%CI 0.12 to 3.82; Analysis 04, outcome 02) and hospital stay (WMD 0.22 days 95%CI ‐0.25 to 0.69; Analysis 04, outcome 04); both were not significantly different. Due to different reported outcomes, the two studies could not be combined. None of the patients in either study required reoperation. Data regarding other outcomes were not available.

There was minimal asymmetry in funnel plot of study size against treatment effect, suggesting lack of publication bias (Figure 1). However the trials are small and few in number.

1.

Discussion

Drains are used widely in thyroid surgery, in spite of the lack of clear benefit. In our meta‐analysis we could find no evidence of a benefit associated with using drains as measured by outcomes such as reoperation rates, incidence of respiratory distress and wound collections. The event rates for the important outcomes such as re‐operation rates and incidence of respiratory distress are low, consistent with previous large series (Ardito 1999). The number of participants in individual trials are low. None of the studies reported the statistical power of the study to detect such small differences. It is hence possible that even after meta analysis, a small benefit or harm is being missed. Previous meta analyses have found no difference in complications rates (Corsten 2005; Sanabria 2007; Pothier 2005).

All the studies excluded patients with lateral neck dissections and patients with coagulation disorders. Some of the studies excluded patients with Grave's disease, large goitres and substernal goitres and therefore we emphasise that the results of this review do not necessarily apply to such patient groups. However for patients undergoing thyroid surgery where there is no mediastinal involvement or additional lateral neck dissection, there is no evidence of benefit from drains, and it would seem safe not to drain these wounds. However the excluded categories need to be examined in future trials.

There are obviously concerns that whilst a policy of not draining is safe, it may lead to more wound collections due to blood or tissue fluids. However we found that the incidence of wound collections was not significantly different between the groups. Assessment of post operative wound collections is variable. Some studies (Tubergen 2001) using ultrasound, show a high frequency of fluid accumulation, attesting to the sensitivity of ultrasound. Apart from being operator dependent, there are no standards for defining normal from abnormal collections in terms of quantity. Very few of these are clinically significant, as on follow up most disappear. On the other hand clinical assessment is subject to bias. Even if assessor blinding is used, it is difficult to conceal the group allocation in case of drain insertion. It is also not clear as to the effect of post operative collections. While not necessarily needing intervention, they may still affect patient comfort and wound healing. Hence reporting of patient's satisfaction using validated scores would be more useful.

While most studies reported complications, respiratory distress as a specific complication was reported only in some of the trials. This is important as this is one of the main reasons for drain insertion. However there are other causes for respiratory distress such as nerve injury and vocal cord oedema. This could affect reporting of this outcome, as the presence of drains can give a false sense of security and hence affect surgeon's opinion as to cause of respiratory distress. Future trials need to specifically report all cases of respiratory distress irrespective of the cause.

Hospital stay was found to be significantly prolonged in patients who had drains. However the weighted mean difference was only 1.18 days (95% CI 0.74 to 1.63). It is not clear from this meta‐analysis as to whether drains affect wound infection rates as there was no evidence of a significant difference between drainage and non drainage groups in terms of infection. As thyroid surgery is a clean operation, wound infection rates are low. There are no patient satisfaction scores reported in any of the study. Hence it is not clear whether drains, especially, when they exit at a separate site, have any adverse effect on the final cosmetic appearance.

We are unable to say what is the optimum drain, in cases where a drain is considered necessary by the surgeon. The number of trials in the other comparisons such as 'suction drain compared with passive closed drain', 'open drain compared with no drain' and 'suction drain compared with open drain' were between one and two, and hence no conclusions could be drawn.

Similar outcomes are obtained whether wound drains are provided or not during thyroid surgery. However hospital stay was significantly prolonged when patients received wound drains.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is no obvious significant advantage associated with using wound drains after common thyroid operations (unilateral and bilateral), in patients where no lateral neck dissection is performed, with no extension of the thyroid into sub‐sternal space and normal coagulation indices. Drains prolong hospital stay and absence of drains may facilitate the rapid discharge of patients after thyroidectomy.

Implications for research.

There remains a great deal of uncertainty around the estimates of the effects of wound drainage after thyroid surgery. Further larger trials are required in patients undergoing resections for large goitres and those with sub‐sternal extensions, comparing drains versus no drains. Larger trials reporting patient indices such as pain and satisfaction with wound appearance are required. Validated clinical measures for outcomes such as postoperative excessive wound collections should be used, rather than ultrasound, as ultrasound detects a large number of clinically insignificant collections. All occurrences of respiratory distress should be specifically reported along with the underlying cause. Trials should be conducted and reported according to CONSORT guidelines. Primary outcome should still be respiratory distress and re‐operation rates, as these are still the major complications following a thyroid operation. However with more centres discharging patients earlier, readmission rates and re intervention rates should be reported in future trials.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 8 August 2008 | Amended | Contact details updated |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2006 Review first published: Issue 4, 2007

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 12 July 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

To the Cochrane Wounds Group for their support and guidance. Northampton General Hospital ‐ Library Staff. Stoke Mandeville Hospital ‐ Library Staff. The peer referees (Adrian Barbul, Simon Gates, Lois Orton, Amy Zelmer) and Wounds Group Editors (Nicky Cullum, Mieke Flour, Andrea Nelson and Gill Worthy). The Cochrane Copy Editor, Elizabeth Royle.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Drain compared with no drain.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Reoperation | 11 | 1436 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.12 [0.77, 5.83] |

| 1.1 Studies of poorer quality | 7 | 884 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.02 [0.91, 10.06] |

| 1.2 Only high quality studies | 4 | 552 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.05, 5.43] |

| 2 Respiratory distress | 3 | 435 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.93 [0.24, 100.75] |

| 3 Wound Infection | 5 | 687 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.60 [0.53, 4.83] |

| 3.1 Studies of poorer quality | 2 | 285 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.49 [0.25, 8.85] |

| 3.2 Only high quality studies | 3 | 402 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.41, 6.85] |

| 4 Collections needing aspiration/drainage without reoperation | 10 | 1336 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.27, 0.97] |

| 4.1 Studies of poorer quality | 6 | 784 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.13, 0.69] |

| 4.2 Only high quality studies | 4 | 552 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.82 [0.51, 6.46] |

| 5 Minor collections not requiring intervention. | 10 | 1286 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.68, 1.55] |

| 5.1 Studies of poorer quality | 7 | 884 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.64, 1.64] |

| 5.2 Only high quality studies | 3 | 402 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.46, 2.38] |

| 6 Pain (proportion) | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.15 [1.10, 4.23] |

| 7 Pain Severity | 1 | 200 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.60 [2.21, 2.99] |

| 8 Hospital Stay | 8 | 1001 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.73, 1.63] |

| 8.1 Studies of poorer quality | 5 | 549 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.59, 1.59] |

| 8.2 Only high quality studies | 3 | 452 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.43, 2.12] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drain compared with no drain, Outcome 1 Reoperation.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drain compared with no drain, Outcome 2 Respiratory distress.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drain compared with no drain, Outcome 3 Wound Infection.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drain compared with no drain, Outcome 4 Collections needing aspiration/drainage without reoperation.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drain compared with no drain, Outcome 5 Minor collections not requiring intervention..

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drain compared with no drain, Outcome 6 Pain (proportion).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drain compared with no drain, Outcome 7 Pain Severity.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drain compared with no drain, Outcome 8 Hospital Stay.

Comparison 2. Suction drain compared with no drain.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Reoperation | 11 | 1386 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.12 [0.77, 5.83] |

| 1.1 Studies of poorer quality | 7 | 884 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.02 [0.91, 10.06] |

| 1.2 only high quality studies | 4 | 502 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.05, 5.43] |

| 2 Respiratory distress | 3 | 435 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.93 [0.24, 100.75] |

| 3 Wound Infection | 5 | 687 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.60 [0.53, 4.83] |

| 3.1 Studies of poorer quality | 2 | 285 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.49 [0.25, 8.85] |

| 3.2 Only high quality studies | 3 | 402 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.41, 6.85] |

| 4 Collections needing aspiration/drainage without reoperation | 10 | 1286 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.25, 0.92] |

| 4.1 Studies of poorer quality | 6 | 784 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.13, 0.69] |

| 4.2 Only high quality studies | 4 | 502 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.78 [0.44, 7.17] |

| 5 Minor collections not requiring intervention. | 10 | 1286 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.68, 1.55] |

| 5.1 Studies of poorer quality | 7 | 884 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.64, 1.64] |

| 5.2 Only high quality studies | 3 | 402 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.46, 2.38] |

| 6 Pain (proportion) | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.15 [1.10, 4.23] |

| 7 Pain Severity | 1 | 200 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.60 [2.21, 2.99] |

| 8 Hospital Stay | 8 | 951 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.77, 1.63] |

| 8.1 Studies of poorer quality | 5 | 549 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.59, 1.59] |

| 8.2 Only high quality studies | 3 | 402 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.60, 2.06] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Suction drain compared with no drain, Outcome 1 Reoperation.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Suction drain compared with no drain, Outcome 2 Respiratory distress.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Suction drain compared with no drain, Outcome 3 Wound Infection.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Suction drain compared with no drain, Outcome 4 Collections needing aspiration/drainage without reoperation.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Suction drain compared with no drain, Outcome 5 Minor collections not requiring intervention..

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Suction drain compared with no drain, Outcome 6 Pain (proportion).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Suction drain compared with no drain, Outcome 7 Pain Severity.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Suction drain compared with no drain, Outcome 8 Hospital Stay.

Comparison 3. Open drain compared with no drain.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Collections needing aspiration/drainage without reoperation | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.5 [0.26, 8.60] |

| 2 Hospital Stay | 1 | 100 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.28, 0.92] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Open drain compared with no drain, Outcome 1 Collections needing aspiration/drainage without reoperation.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Open drain compared with no drain, Outcome 2 Hospital Stay.

Comparison 4. Suction drain compared with open drain.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Wound Infection | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.04, 3.07] |

| 2 Collections needing aspiration/drainage without reoperation | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.12, 3.82] |

| 3 Minor collections not requiring intervention. | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.10, 2.58] |

| 4 Hospital Stay | 1 | 100 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.22 [‐0.25, 0.69] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Suction drain compared with open drain, Outcome 1 Wound Infection.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Suction drain compared with open drain, Outcome 2 Collections needing aspiration/drainage without reoperation.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Suction drain compared with open drain, Outcome 3 Minor collections not requiring intervention..

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Suction drain compared with open drain, Outcome 4 Hospital Stay.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

De Salvo 1998.

| Methods | Randomisation ‐ unclear Allocation concealment ‐unclear Blinding of care provider ‐ unclear Blinding of assessor ‐ unclear Follow up ‐ Adequate | |

| Participants | Country‐ Italy All thyroid operations (sub total thyroidectomy) except those with mediastinal extension and Basedow's disease Age range 19‐75 Number of females 62 Sample = 80 | |

| Interventions | Open drain compared with closed (suction) | |

| Outcomes | Haematoma, Seroma Wound infection Number of dressing changes | |

| Notes | Drain usage fixed ‐ 24 hrs | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Debry 1999.

| Methods | Randomisation ‐ by random number table. Allocation concealment ‐ sealed envelopes Blinding of care provider ‐ unclear Blinding of assessor ‐ unclear Follow up ‐ adequate | |

| Participants | Country ‐France All thyroid surgeries except those requiring cervical neck dissection Sample 100 Mean Age 46.5 Females 86 Age range n/a | |

| Interventions | Suction drain compared with no drain | |

| Outcomes | Infection/ haematoma Ultrasound in doubtful cases Hospital stay | |

| Notes | Includes some patients with grave's disease | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Giovannini 1999.

| Methods | Randomisation‐ unclear Allocation concealment ‐ unclear Blinding of care provider ‐ unclear Blinding of assessor ‐ unclear Follow up‐ adequate | |

| Participants | Country‐ Italy Thyroid operations (44 Hemithyroidectomies and 100 thyroidectomies) Excluded: Malignant thyroid operations involving total thyroidectomy with neck dissection , coagulation disorders, Basedow,s disease and Basedow's Goitre Sample 144 Number of females 114 Age range n/a | |

| Interventions | Suction drain versus no drain | |

| Outcomes | Seroma / haematoma | |

| Notes | Drain usage fixed (2 days) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Hurtado‐Lopez 2001.

| Methods | randomisation‐ random number table Allocation concealment ‐ sealed envelopes Blinding of care provider ‐ unclear Blinding of assessor‐ unclear Follow up ‐ adequate | |

| Participants | All thyroid surgeries Total 150, 50 in each group Age range 15‐ 72 | |

| Interventions | Three groups: No drain, Penrose drain and suction drain | |

| Outcomes | Haematoma/ seroma Reoperation Hospital Stay | |

| Notes | Authors contacted and further data obtained. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Khanna 2005.

| Methods | Randomisation ‐ by computer generated random number table Allocation concealment ‐ sealed envelopes Blinding of care provider ‐ unclear Blinding of assessor ‐ unclear Follow up ‐ adequate | |

| Participants | 94 patients undergoing 104 thyroid surgeries Re‐operative thyroids included Exclusion: those requiring cervical neck dissection Mean age 34.5 Age range 8‐60 | |

| Interventions | Suction drain compared with no drain | |

| Outcomes | Ultrasound on day 1 and day 8 for collection Respiratory distress Wound collection Infection Tetany Tingling | |

| Notes | Drain usage fixed‐ 48 hrs | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Lee 2006.

| Methods | Randomisation ‐ computer generated Allocation concealment‐ unclear Blinding of care provider ‐ unclear Blinding of assessor ‐ unclear Follow up ‐ adequate | |

| Participants | Participants: all thyroidectomies Excluded: Lateral cervical dissection and excision of surrounding soft tissues for large goitres, substernal goitres, Grave's disease Total number 198 Number of females 174 Mean age 47.6 Age range n/a | |

| Interventions | Suction drain compared with no drain | |

| Outcomes | Seroma / haematoma | |

| Notes | Drain usage not fixed. Removed if less than 20 ml/24 hrs | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Peix 1992.

| Methods | Randomisation ‐ unclear Allocation concealment ‐sealed envelopes Blinding of participant ‐ unclear Blinding of care provider ‐ unclear Outcome assessors blinding‐ adequate Follow up‐adequate Power calculation done‐ power estimated to be 50% to detect a RR of 3 for complications, but at end of study. No sample size calculation before starting trial. | |

| Participants | Country ‐ France sample 97 Mean age 43 Females 85 age less than 75 no previous neck surgery clinically and bischemically euthyroid thyroid surgery for excision of cold nodule Only unilateral lobectomies weighing less than 250 gms same surgeon Age range n/a | |

| Interventions | Suction drain compared with no drain | |

| Outcomes | Haematoma Hospital Stay | |

| Notes | Drain removed 24‐ 48 hrs | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Pezzullo 2001.

| Methods | Randomisation unclear. Allocation concealment ‐sealed envelopes Blinding of care provider ‐ unclear Outcome assessors blinding‐ unclear Follow up ‐adequate | |

| Participants | 60 patients Country: Italy Mean Age: 45.7 Age range n/a Females 52 9 different surgeons ( 2 senior and 7 junior) Exclusion: Previous neck irradiation or surgery Both unilateral and bilateral operations | |

| Interventions | Drain (Blake's) compared with no drain | |

| Outcomes | Haemorrhage Seroma Hospital stay | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Schoretsanitis 1998.

| Methods | Randomisation ‐ by computer Allocation concealment‐adequate, third party Blinding of care provider ‐ unclear Blinding of assessor‐ unclear Follow up‐ adequate | |

| Participants | Country ‐ Greece All thyroid operations Sample 200 Median age 52 Age range n/a Number of females 121 | |

| Interventions | Suction drain compared with no drain | |

| Outcomes | Pain at 24 hrs by visual analogue scale 0 to 10. 24 hr analgesic requirement Reoperation Wound collection Wound infection | |

| Notes | Drain usage 24‐48 hrs No prophylactic antibiotics Lymphatic discharge in 2 patients | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Schwarz 1996.

| Methods | Same as Willy 1998 | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Suslu 2006.

| Methods | Randomisation ‐ unclear Allocation concealment ‐ unclear Blinding of care provider ‐ unclear Blinding of assessor ‐ unclear Follow up adequate | |

| Participants | Age range n/a All thyroid surgeries, including recurrent surgery, Graves disease included. Sample 135 Age 34‐60 Exclusions: Neck dissections and mediastinal extensions | |

| Interventions | Suction drain compared with no drain | |

| Outcomes | Haematoma seroma Reoperation Hospital Stay Wound infection | |

| Notes | Antibiotics used pre op | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Teboul 1992.

| Methods | Same as Peix 1992 | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Tubergen 2001.

| Methods | Randomisation ‐ unclear Allocation concealment ‐ sealed envelopes Blinding of care provider ‐ unclear Blinding of assessor ‐ unclear Follow up ‐ adequate | |

| Participants | Patients with thyroid nodule, clinically and biochemically euthyroid Sample 100 Age range 20‐82 | |

| Interventions | Suction drain compared with no suction | |

| Outcomes | Wound collection as measured clinically Ultrasound on 3rd postop day and after discharge Reoperation for bleed Pain Hospital stay | |

| Notes | Drain usage ‐ fixed (48 hrs) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Whilborg 1998.

| Methods | Randomisation ‐ unclear Blinding of care provider ‐ unclear Blinding of assessor ‐ unclear Follow up ‐ adequate | |

| Participants | Age range 10‐77 Median age 48 Sample 150 | |

| Interventions | Suction drain compared with no drain | |

| Outcomes | Reoperation for haematoma Wound Infection Hospital stay | |

| Notes | Surgeon forgot to randomise 3 patients 3 had sternotomy 2 had extensive cervical dissection 1 lymphatic leak settled after 18 days. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Willy 1998.

| Methods | Randomisation ‐ random number table. Allocation concealment‐ inadequate. Surgeon was aware of allocation before starting surgery (as envelopes were opened at start of operation). Blinding of care provider ‐ unclear Blinding of assessor ‐ unclear Follow up ‐ adequate | |

| Participants | All bilateral operations (subtotal thyroidectomies) Total number 80 Number of females 51 Age range 20‐79 Exclusions: unilateral operations, coagulation disorders, previous neck operations | |

| Interventions | High vacuum (Redon) compared with passive (Robinson) drain | |

| Outcomes | Collection volume after removal of drains measured by ultrasound Hospital stay Reoperation/ aspiration of haematomas Total volume drained by either drains | |

| Notes | Ciprofloxacin pre op Surgeon aware of group allocation before starting surgery | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Ayyash 1991 | Includes parathyroid operations |

| Kristoffersson 1986 | Includes parathyroid operations |

Contributions of authors

K Samraj wrote the review and is the guarantor of the review. He identified the studies, independently assessed them and extracted data. K Gurusamy, co author, helped in writing the protocol and critically reviewed the final review. He independently scrutinised the search results, identified the potentially eligible studies and extracted data.

Declarations of interest

None known

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

De Salvo 1998 {published data only}

- Salvo L, Razzetta F, Tassone U, Arezzo A, Mattioli FP. [The role of drainage and antibiotic prophylaxis in thyroid surgery]. Minerva Chirurgica 1998;53(11):895‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Debry 1999 {published data only}

- Debry C, Renou G, Fingerhut A. Drainage after thyroid surgery: a prospective randomized study. The Journal of Laryngology and Otology 1999;113(1):49‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Giovannini 1999 {published data only}

- Giovannini C, Milito R, Pronio A, Santella S, Montesani C. Use of drainage in thyroid surgery. Chirurgia 1999;12(6):419‐21. [Google Scholar]

Hurtado‐Lopez 2001 {published data only}

- Hurtado‐Lopez LM, Lopez‐Romero S, Rizzo‐Fuentes C, Zaldivar‐Ramirez FR, Cervantes‐Sanchez C. Selective use of drains in thyroid surgery. Head and Neck 2001;23(3):189‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Khanna 2005 {published data only}

- Khanna J, Mohil RS, Chintamani, Bhatnagar D, Mittal MK, Sahoo M, et al. Is the routine drainage after surgery for thyroid necessary? A prospective randomized clinical study [ISRCTN63623153]. BMC Surgery 2005;5(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lee 2006 {published data only}

- Lee SW, Choi EC, Lee YM, Lee JY, Kim SC, Koh YW. Is lack of placement of drains after thyroidectomy with central neck dissection safe? A prospective, randomized study. Laryngoscope 2006;116(9):1632‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Peix 1992 {published data only}

- Peix JL, Teboul F, Feldman H, Massard JL. Drainage after thyroidectomy: a randomized clinical trial. International Surgery 1992;77(2):122‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pezzullo 2001 {published data only}

- Pezzullo L, Chiofalo MG, Caraco C, Marone U, Celentano E, Mozzillo N. Drainage in thyroid surgery: a prospective randomised clinical study. Chirurgia Italiana 2001;53(3):345‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schoretsanitis 1998 {published data only}

- Schoretsanitis G, Melissas J, Sanidas E, Christodoulakis M, Vlachonikolis JG, Tsiftsis DD. Does draining the neck affect morbidity following thyroid surgery?. American Surgeon 1998;64(8):778‐80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schwarz 1996 {published data only}

- Schwarz W, Willy C, Ndjee C. [Gravity or suction drainage in thyroid surgery? Control of efficacy with ultrasound determination of residual hematoma]. Langenbecks Archiv fur Chirurgie 1996;381(6):337‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Suslu 2006 {published data only}

- Suslu N, Vural S, Oncel M, Demirca B, Gezen FC, Tuzun B, et al. Is the insertion of drains after uncomplicated thyroid surgery always necessary?. Surgery Today 2006;36(3):215‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Teboul 1992 {published data only}

- Teboul F, Peix JL, Guibaud L, Massard JL, Ecochard R. [Prophylactic drainage after thyroidectomy: a randomized trial]. Annales de Chirurgie 1992;46(10):902‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tubergen 2001 {published data only}

- Tubergen D, Moning E, Richter A, Lorenz D. [Assessment of drain insertion in thyroid surgery?]. Zentralblatt fur Chirurgie 2001;126(12):960‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Whilborg 1998 {published data only}

- Wihlborg O, Bergljung L, Martensson H. To drain or not to drain in thyroid surgery. A controlled clinical study. Archives of Surgery 1988;123(1):40‐1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Willy 1998 {published data only}

- Willy C, Steinbronn S, Sterk J, Gerngross H, Schwarz W. Drainage systems in thyroid surgery: a randomised trial of passive and suction drainage. European Journal of Surgery 1998;164(12):935‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Ayyash 1991 {published data only}

- Ayyash K, Khammash M, Tibblin S. Drain vs. no drain in primary thyroid and parathyroid surgery. European Journal of Surgery 1991;157(2):113‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kristoffersson 1986 {published data only}

- Kristoffersson A, Sandzen B, Jarhult J. Drainage in uncomplicated thyroid and parathyroid surgery. British Journal of Surgery 1986;73(2):121‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Mok 1992 {published data only}

- Mok CO, King WWK, Paterson‐Brown S, Mitchell RD, Li AKC. Suction drainage after thyroidectomy – is it necessary?. Third International Conference on Head and Neck Cancer, San Francisco. San Francisco, 1992.

Additional references

Abbas 2001

- Abbas G, Dubner S, Heller KS. Re‐operation for bleeding after thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy. Head and Neck 2001;23(7):544‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Affleck 2003

- Affleck BD, Swartz K, Brennan J. Surgical considerations and controversies in thyroid and parathyroid surgery. Otolaryngology Clinics of North America 2003;36(1):159‐87. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ardito 1999

- Ardito G, Revelli L, Guidi ML, Murazio M, Lucci C, Modugno P, et al. [Drainage in thyroid surgery]. Annali Italiani di Chirurgia 1999;70(4):511‐6; discussion 516‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brander 1991

- Brander A, Viikinkoski P, Nickels J, Kivisaari L. Thyroid gland: US screening in a random adult population. Radiology 1991;181(3):683‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Coello 1997

- Coello R, Glynn JR, Gaspar C, Picazo JJ, Fereres J. Risk factors for developing clinical infection with methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) amongst hospital patients initially only colonized with MRSA. The Journal of Hospital Infection 1997;37(1):39‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collis 2005

- Collis N, McGuiness CM, Batchelor AG. Drainage in breast reduction surgery: a prospective randomised intra‐patient trail. British Journal of Plastic Surgery 2005;58(3):286‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Coress 2005

- Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland. He was speechless.... Confidential reporting systems in surgery (CORESS) December 2005. [Ref 013]

Corsten 2005

- Corsten M, Johnson S, Alherabi A. Is suction drainage an effective means of preventing hematoma in thyroid surgery? A meta‐analysis. Journal of Otolaryngology 2005;34(6):415‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dackiw 2004

- Dackiw AP, Zeiger M. Extent of surgery for differentiated thyroid cancer. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2004;84(3):817‐32. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Daou 1997

- Daou R. [Thyroidectomy without drainage]. Chirurgie, memoires de l'Academie de chirurgie 1997;122(7):408‐10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

DeMets 1987

- DeMets DL. Methods for combining randomized clinical trials: strengths and limitations. Statistics in Medicine 1987;6(3):341‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

DerSimonian 1986

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials 1986;7(3):177‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egger 1997

- Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. British Medical Journal 1997;315(7109):629‐34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ernst 1997

- Ernst R, Wiemer C, Rembs E, Friemann J, Theile A, Schafer K, et al. Local effects and changes in wound drainage in the free peritoneal cavity. Langenbecks Archiv fur Chirurgie 1997;382(6):380‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Farquharson 2005

- Farquharson M, Moran B. Surgery of the neck. In: Farquharson M, Moran B editor(s). Farquharson's Textbook of Operative General Surgery. 9. London: Hodder Arnold Publication, 2005:165‐7. [ISBN‐13:9780340814963] [Google Scholar]

Fredrickson 1998

- Fredrickson JM. Surgical Management of parathyroid disorder. In: Summers GW, Cummings CW, Fredrickson J M, Harker LA, Krause CJ, Richardson MA, et al. editor(s). Otolaryngology‐Head and Neck Surgery. 3. Vol. 3, Philadelphia: Mosby Year Book, Inc, 1998:2524‐5. [Google Scholar]

Friguglietti 2003

- Friguglietti CU, Lin CS, Kulcsar MA. Total thyroidectomy for benign thyroid disease.. Laryngoscope 2003;113(10):1820‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gavilán 2002

- Gavilán J, Herranz J, Desanto LW, Gavilán C. Surgical Technique. In: Gavilán J, Herranz J, Desanto LW, Gavilán C editor(s). Functional and Selective Neck Dissection. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, 2002:104‐5. [Google Scholar]

Healy 1989

- Healy DA, Keyser J, 3rd, Holcomb GW, 3rd, Dean RH, Smith BM. Prophylactic closed suction drainage of femoral wounds in patients undergoing vascular reconstruction. Journal of Vascular Surgery 1989;10(2):166‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

HES 2006

- Department of Health. Hospital Episode Statistics. http://www.hesonline.nhs.uk/Ease/servlet/ContentServer?siteID=1937&categoryID=215 Accessed 11 December 2006.

Higgins 2002

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Statistics in Medicine 2002;21(11):1539‐58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2005

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews for Interventions 4.2.4 [updated March 2005]. http://www.cochrane.org/resources/handbook/hbook.htm (accessed 2005).

Hollis 1999

- Hollis S, Campbell F. What is meant by intention to treat analysis? Survey of published randomised controlled trials. British Medical Journal 1999;319(7211):670‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Horan 1992

- Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 1992;13(10):606‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Huang 2005

- Huang SM, Lee CH, Chou FF, Liaw KY, Wu TC. Characteristics of thyroidectomy in Taiwan. Journal of Formosan Medical Association = Taiwan yi zhi 2005;104(1):6‐11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hurtado‐Lopez 2002

- Hurtado‐Lopez LM, Zaldivar‐Ramirez FR, Basurto Kuba E, Pulido Cejudo A, Garza Flores JH, Munoz Solis O, et al. Causes for early reintervention after thyroidectomy. Medicine Science Monitor 2002;8(4):CR247‐50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Karayacin 1997

- Karayacin K, Besim H, Ercan F, Hamamci O, Korkmaz A. Thyroidectomy with and without drains. East African Medical Journal 1997;74(7):431‐2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kjaergard 2001

- Kjaergard LL, Villumsen J, Gluud C. Reported methodologic quality and discrepancies between large and small randomized trials in meta‐analyses. Annals of Internal Medicine 2001;135(11):982‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Knudsen 2000