Abstract

Heated (20 min at 70°C) amphotericin B-desoxycholate (hAMB-DOC) was further characterized, as was another formulation obtained after centrifugation (60 min, 3000 × g), hcAMB-DOC. Conventional AMB-DOC consisted of individual micelles (approximately 4 nm in diameter) and threadlike aggregated micelles, as revealed by cryo-transmission electron microscopy. For both hAMB-DOC and hcAMB-DOC, pleiomorphic cobweb structures were observed with a mean particle size of approximately 300 nm as determined by laser diffraction. The potent antifungal activity of AMB-DOC against Candida albicans is not reduced by heating. Effective killing of C. albicans (>99.9% within 6 h) was obtained at 0.1 mg/liter with each of the AMB formulations. For AMB-DOC, hAMB-DOC, and hcAMB-DOC, cation release (86Rb+) from C. albicans of ≥50% was observed at 0.8, 0.4, and 0.4 mg/liter, respectively. After heating of AMB-DOC, toxicity was reduced 16-fold as determined by red blood cell (RBC) lysis. For AMB-DOC, hAMB-DOC, and hcAMB-DOC, hemolysis of ≥50% was observed at 6.4, 102.4, and 102.4 mg/liter, respectively. In contrast, AMB-DOC and its derivates showed similar toxicities in terms of cation release from RBC. For AMB-DOC, hAMB-DOC, and hcAMB-DOC, cation release (86Rb+) of ≥50% was observed at 1.6, 0.8, and 0.8 mg/liter, respectively. In persistently leukopenic mice with severe invasive candidiasis, higher dosages of both hAMB-DOC and hcAMB-DOC were tolerated than those of conventional AMB-DOC (3 versus 0.8 mg/kg of body weight, respectively), resulting in significantly improved therapeutic efficacy. In conclusion, this new approach of heating AMB-DOC may be of great value for further optimizing the treatment of severe fungal infections.

As the overall prognosis for immunocompromised patients with severe invasive fungal infections remains poor, there is an urgent need for therapeutic advances. Amphotericin B-desoxycholate (AMB-DOC) remains the therapy of choice for most invasive fungal infections, but its use is significantly limited by toxic side effects. Lipid formulations of AMB have been developed by the pharmaceutical industry, with the primary aim to reduce AMB's toxicity. It is now clear from a number of clinical studies that the three industrially produced AMB-lipid formulations (Abelcet, Amphocil/Amphotec, and AmBisome) are substantially less toxic than AMB-DOC (3, 10). Studies with animal models of invasive fungal infections have clearly demonstrated that often high dosages of AMB-lipid formulations are needed for treatment to be effective (5). Questions regarding the optimal dosing and duration of treatment in human patients are still unanswered for each of the AMB-lipid formulations. Therefore, and also because treatment with AMB-lipid formulations is very expensive, many patients with severe invasive fungal infections are still undergoing aggressive treatment with conventional AMB-DOC.

It was recently shown by others (1, 2, 8, 9) that when AMB-DOC is heated for 20 min at 70°C (hAMB-DOC), its toxicity is greatly reduced without any effect on its potent antifungal activity. In different models of invasive fungal infections in immunocompetent mice, viz., systemic candidiasis, cryptococcal pneumonia, and cryptococcal meningoencephalitis, higher dosages of hAMB-DOC were tolerated than those of conventional AMB-DOC, resulting in significantly improved therapeutic efficacy. Although the results of these first studies are very encouraging, there are still many questions which need to be answered.

In the present study, hAMB-DOC was further characterized. Ultrastructure and mean particle size were determined. The in vitro toxicity and influence of storage temperature on in vitro toxicity were investigated. Furthermore, studies on the in vitro antifungal activity and therapeutic efficacy in a model of severe invasive candidiasis in persistently leukopenic mice were performed. Additionally, it was investigated whether the hAMB-DOC formulation could be further improved by centrifugation (hcAMB-DOC), yielding a preparation with relatively increased numbers of AMB aggregates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was from Janssen Chimica (Tilburg, The Netherlands). 86RbCl (specific activity, 1.5 to 2.2 mCi/mg at the reference date) was from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech UK Limited (Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). Methanol and NaHCO3 were from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Cyclophosphamide and DOC were from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). Sabouraud dextrose agar was from Unipath Ltd. (Basingstoke, United Kingdom). AMB-DOC (Fungizone) and pure AMB were kindly provided by Bristol Myers-Squibb (Woerden, The Netherlands).

AMB-DOC and its derivates.

Stock AMB-DOC was prepared by reconstitution of a vial of Fungizone (50 mg of AMB and 41 mg of DOC) with 10 ml of sterile water for injection. Stock hAMB-DOC was prepared as described by Gaboriau et al. (2). First, a stock of AMB-DOC was prepared as described above. Subsequently, the vial was heated for 20 min at 70°C. Stock hcAMB-DOC was prepared as follows. First, a stock of hAMB-DOC was prepared as described above. Subsequently, the total volume (10 ml) of hAMB-DOC was centrifuged (60 min at 3000 × g), after which the supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of 5% (wt/vol) dextrose in sterile water (5-DW) for injection.

The AMB concentration of the stock of either AMB-DOC, hAMB-DOC, or hcAMB-DOC was determined spectrophotometrically at 405 nm after dilution of the stock 300-, 400-, and 500-fold in DMSO-methanol (1/1, vol/vol). Calibration standards of pure AMB in DMSO-methanol (1/1, vol/vol) were used, ranging from 2 to 20 mg/liter. For each AMB formulation, complete monomerization of AMB was obtained after dilution of the stock in DMSO-methanol (1/1, vol/vol), as similar absorption spectra were obtained for AMB-DOC, hAMB-DOC, hcAMB-DOC, and pure AMB at a concentration of 10 mg/liter. After determination of the AMB concentration of the stock (approximately 5 g/liter for both AMB-DOC and hAMB-DOC and approximately 4.7 g/liter for hcAMB-DOC), further dilutions were made in aqueous solution as indicated in the descriptions of the various experiments.

Candida strain.

Candida albicans ATCC 44858 was used in all of the experiments and was stored at −80°C in Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) containing 10% (vol/vol) glycerol.

RBC.

Red blood cells (RBC) were obtained from male RP strain albino rats (specific pathogen free, 18 to 25 weeks old, 185 to 225 g; Harlan CPB, Austerlitz, The Netherlands).

Animals.

Specific-pathogen-free, 14- to 20-week-old, female BALB/c mice were obtained from Iffa Credo (L'Arbresle, France).

Characterization of AMB-DOC and its derivates.

The appearance of AMB-DOC and its derivates was examined by cryo-electron microscopy. A copper grid (700 mesh, hexagonal pattern, 3 to 4 μm thick, no support film) was dipped in the suspension of AMB-DOC or its derivates. After withdrawing the grid from the suspension, the excess liquid was blotted away with filter paper, leaving aqueous thin films spanning the 30-μm holes in the grid. By a guided drop, the specimen was vitrified in melting ethane. These preparatory steps were carried out in a fully automated preparation chamber with temperature and humidity control. After vitrification the specimens were transferred under liquid nitrogen to a Gatan cryoholder and mounted on a Philips CM12 microscope. Micrographs from the vitrified specimens were taken at −170°C using low-electron-dose conditions.

The particle size distributions of hAMB-DOC and hcAMB-DOC were determined by laser diffraction (Mastersizer; Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern, United Kingdom).

In vitro killing of C. albicans.

The in vitro activities of AMB-DOC and its derivates in terms of effective killing (>99.9%) of C. albicans at an inoculum of 1.3 × 107 CFU/liter during 6 h of incubation were determined in three separate experiments as described previously (11, 12). Briefly, a log-phase culture of C. albicans was prepared. C. albicans was exposed during 6 h of incubation on a roller to twofold-increasing concentrations of AMB-DOC or its derivates (0.025 to 1.6 mg of AMB/liter) in Antibiotic Medium No. 3 or to DOC (1.3 mg/liter) in Antibiotic Medium No. 3. During incubation the numbers of viable C. albicans organisms were determined at 2-h intervals by making plate counts of 10-fold serial dilutions of the washed specimen on Sabouraud dextrose agar.

Ion fluxes in C. albicans.

Cation fluxes in yeast cells were measured in three separate experiments as described by Juliano et al. (4), with minor adaptations. C. albicans was loaded with 86Rb+ (86RbCl) by incubating 3.5 × 107 CFU of C. albicans/ml with 10 μCi of 86Rb+/ml in buffer solution (0.02% [wt/vol] NaHCO3 in 5-DW) for 24 h at 37°C on a roller. C. albicans cells were washed in buffer solution to remove unincorporated 86Rb+. For efflux experiments C. albicans (3.5 × 106 CFU/ml) was incubated for 90 min on a roller at 37°C in buffer solution alone (control), in DOC in buffer solution (84 mg/liter), or in twofold-increasing concentrations of AMB-DOC or its derivates in buffer solution (0.05 to 102.4 mg of AMB/liter). C. albicans was pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernatant was recovered by careful aspiration. Radioactivity counts of 86Rb+ in the pellet and supernatant were determined using a gamma counter (Minaxi gamma 5000 series; Packard Instrument Co., Inc., Downers Grove, Ill.). The efflux (E) of 86Rb+ was determined according to the following formula: cpmsup/(cpmsup + cpmpellet), where cpm is counts per minute and sup is supernatant. The percentage of 86Rb+ release was calculated according to the following formula: (Eexp − Econtrol)/(Emax − Econtrol) × 100, where Eexp is the efflux of 86Rb+ from C. albicans after exposure to AMB-DOC or its derivates and Emax is maximum efflux.

Ion fluxes in RBC.

Cation fluxes in RBC were measured in three separate experiments as described by Juliano et al. (4), with minor adaptations. Fresh, washed RBC were loaded with 86Rb+ by incubating 100% (vol/vol) RBC with 100 μCi of 86Rb+/ml in buffer solution for 3 h at 37°C on a roller. RBC were washed in buffer solution to remove unincorporated 86Rb+. For efflux experiments, RBC (2%, vol/vol) were incubated for 60 min on a roller at 20°C in buffer solution alone (control), in DOC in buffer solution (84 mg/liter), or in twofold-increasing concentrations of AMB-DOC or its derivates in buffer solution (0.05 to 102.4 mg of AMB/liter). RBC were pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernatant was recovered by careful aspiration. Radioactivity counts of 86Rb+ in the pellet and supernatant and the 86Rb+ release were determined as described above.

Hemolysis from RBC.

Hemolysis from RBC was measured in three separate experiments as described by Mehta et al. (7), with minor adaptations. Washed RBC (2%, vol/vol) were incubated for 6 h on a roller with twofold-increasing concentrations of AMB-DOC or its derivates in buffer solution (12.8 to 102.4 mg of AMB/liter), in DOC in buffer solution (84 mg/liter), in buffer solution alone (control), or in deionized water for 100% lysis. RBC were pelleted by centrifugation, and released hemoglobin in the supernatant was determined by its absorbance at 580 nm. The percentage of hemolysis was calculated according to the following formula: (Aexp − Acontrol)/(A100% − Acontrol) × 100, in which A is the absorbance at 580 nm. For both hAMB-DOC and hcAMB-DOC, hemolysis experiments were performed immediately after preparation (time zero) and after 24 h, 48 h, or 8 days of storage at +4 and −80°C, respectively.

Determination of MTD in uninfected mice.

Toxicity of AMB-DOC or its derivates was measured in uninfected mice as described previously (12). Briefly, mice (10 per group) were treated intravenously (i.v.) with a single dose of AMB-DOC or its derivates. AMB dosages ranged from 0.1 to 1.0 mg/kg of body weight in steps of 0.1 mg/kg and from 1 to 9 mg/kg in steps of 1 mg/kg. Mortality was assessed immediately following injection of the preparation. Blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine, as parameters for renal toxicity, and aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase, as parameters for liver toxicity, were determined by established methods in serum samples of mice sacrificed 24 h or 14 days after termination of treatment. The maximum tolerated dosage (MTD) was defined as the maximum dosage that did not result in death or a >3-fold increase in the indices for renal and liver function compared to indices of untreated mice.

Efficacies of AMB-DOC and its derivates in leukopenic mice infected with C. albicans.

Leukopenic mice were infected by C. albicans as previously described (11, 12). AMB-DOC or its derivates were each administered i.v. as a single dose either 6 or 16 h after C. albicans inoculation at dosages corresponding to their MTDs. hAMB-DOC and hcAMB-DOC were also administered at a dosage equivalent to the MTD of AMB-DOC. Controls were treated with 5-DW. Just before treatment and 7 days after C. albicans inoculation, the surviving mice were sacrificed. In the present study, only the number of viable C. albicans organisms in the kidney was determined, as it was previously shown (11) that in this animal model the kidney is the most severely infected organ. Survival rates of mice and reduction in the numbers of viable C. albicans organisms in the kidneys were used as parameters to assess the efficacy of treatment (10 mice per group).

Statistical analysis.

Results of cation fluxes and hemolysis were expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD); sigmoidal fits (r2 > 0.99) of the dose response curves were applied. Statistical evaluation of differences in the survival rates (Kaplan-Meier plot) for mice with invasive candidiasis was performed by the log rank test. This test examines the decrease in survival rates over time as well as the final percentage of survival. Results of quantitative cultures in invasive candidiasis were expressed as the geometric means ± SD. Differences in viable C. albicans counts between the various treatment groups were analyzed by using the Mann-Whitney test. P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant in these analyses.

RESULTS

Characterization of AMB-DOC and its derivates.

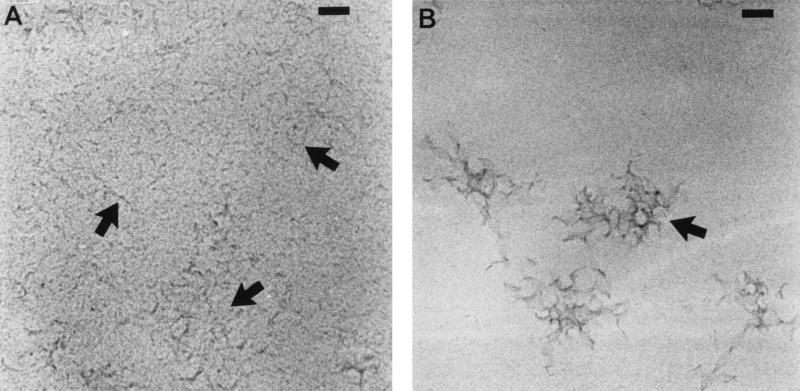

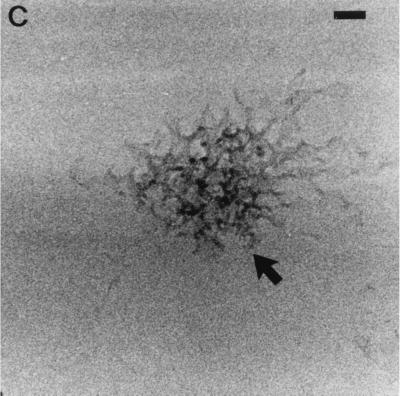

AMB-DOC consisted of individual micelles (approximately 4 nm in diameter) and threadlike, aggregated micelles, as revealed by cryo-transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 1A). For both hAMB-DOC and hcAMB-DOC, pleiomorphic cobweb structures were observed (Fig. 1B and C, respectively), with a mean particle size of approximately 300 nm as determined by laser diffraction. The micellar (sub)structures were largely absent.

FIG. 1.

Cryo-transmission electron micrographs of small threadlike micelles of AMB-DOC (arrows) (A), pleiomorphic cobweb structures of hAMB-DOC (arrow) (B), and hcAMB-DOC, which has an appearance similar to that of hAMB-DOC (arrow) (C). Regions of higher density near hole edges indicate thicker ice. Bars = 50 nm (A and C) and 60 nm (B).

In vitro killing of C. albicans.

For AMB-DOC and its derivates, the minimal AMB concentrations required for killing >99.9% of the initial C. albicans inoculum within 6 h of incubation were determined. Both hAMB-DOC and hcAMB-DOC were as effective as AMB-DOC, with effective killing obtained at 0.1 mg/liter.

Ion fluxes in C. albicans.

The effects of AMB-DOC and its derivates on ion fluxes in C. albicans are shown in Fig. 2A. Release of 86Rb+ after incubation in DOC alone never exceeded that of the controls (data not shown). For AMB-DOC, hAMB-DOC, and hcAMB-DOC, 86Rb+ release of ≥50% was observed at 0.8, 0.4, and 0.4 mg/liter, respectively.

FIG. 2.

(A) Effects of AMB-DOC and its derivates on ion fluxes in yeast cells (C. albicans). The release of 86Rb+ caused by various concentrations of AMB-DOC (●), hAMB-DOC (▴), and hcAMB-DOC (▾) was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Data points are means of triplicate determinations. (B) Effects of AMB-DOC and its derivates on ion fluxes (closed symbols) and hemolysis (open symbols) of erythrocytes. The release of 86Rb+ and the hemolysis induced by various concentrations of AMB-DOC (● and ○), hAMB-DOC (▴ and ▵), and hcAMB-DOC (▾ and ▿) were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Data points are means of triplicate determinations.

Ion fluxes in RBC.

The effects of AMB-DOC and its derivates on ion fluxes in RBC are shown in Fig. 2B. Release of 86Rb+ after incubation in DOC alone never exceeded that of the controls (data not shown). For AMB-DOC, hAMB-DOC, and hcAMB-DOC, 86Rb+ release of ≥50% was observed at 1.6, 0.8, and 0.8 mg/liter, respectively.

Hemolysis of RBC.

The effects of AMB-DOC and its derivates on hemolysis of RBC are shown in Fig. 2B. Hemolysis after incubation in DOC alone never exceeded that of the controls (data not shown). After heating of AMB-DOC, toxicity was reduced 16-fold. For AMB-DOC, hAMB-DOC, and hcAMB-DOC, hemolysis of ≥50% was observed at 6.4, 102.4, and 102.4 mg/liter, respectively.

Toxicity in terms of hemolysis of RBC remained low for hAMB-DOC when stored at −80°C for up to 8 days. In contrast, toxicity of hAMB-DOC slowly increased during 8 days of storage at 4°C, indicating that hAMB-DOC is unstable at 4°C. hcAMB-DOC remained stable for 8 days at either 4 or −80°C.

MTD in uninfected mice.

The MTDs of AMB-DOC and derivates that were determined 24 h after single-dose treatment are presented in Table 1. Similar results were observed 14 days after treatment (data not shown). For AMB-DOC the MTD was 0.8 mg/kg, restricted by mortality after further increase of the dose. For both hAMB-DOC and hcAMB-DOC the MTD was 3 mg/kg; further increase of the dose resulted in impaired liver function, whereas mortality of mice was observed at dosages above 7 mg/kg.

TABLE 1.

MTDs of AMB-DOC, hAMB-DOC, and hcAMB-DOC in uninfected micea

| Parameter for toxicityb | MTD (mg of AMB/kg)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| AMB-DOC | hAMB-DOC | hcAMB-DOC | |

| Death after treatment | 0.8 | 7 | 7 |

| Impaired renal function | >0.8 | 5 | 5 |

| Impaired liver function | >0.8 | 3 | 3 |

Mice were treated i.v. with a single dose. AMB dosages ranged from 0.1 to 1.0 mg/kg in steps of 0.1 mg/kg and from 1 to 9 mg/kg in steps of 1 mg/kg.

Toxicity was determined as causing death after treatment or >3-fold increases in the indices for renal function (blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine) and liver function (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase) compared with those for untreated mice determined 24 h after treatment.

Efficacies of AMB-DOC and its derivates in leukopenic mice infected with C. albicans.

The effects of early or delayed treatment with AMB-DOC and its derivates on the survival of leukopenic mice and growth of C. albicans in the kidney are presented in Fig. 3 and Table 2. By increasing the delay between C. albicans inoculation and the time of treatment, the efficacy of treatment in relation to the severity of infection could be investigated. This was reflected in the number of C. albicans CFU in the kidney at the time of treatment (Table 2). Placebo-treated mice die within 3 days of C. albicans inoculation. AMB-DOC administered i.v. as a single dose of the MTD, 0.8 mg/kg, 6 h after C. albicans inoculation was only partially effective; all mice survived up to 7 days after fungal inoculation (P ≤ 0.001 versus controls) (Fig. 3A). However, numbers of viable C. albicans organisms in the kidney were higher than at the time of treatment (Table 2). Similar results were obtained after treatment with either hAMB-DOC or hcAMB-DOC at 0.8 mg/kg (Fig. 3A and Table 2). Both hAMB-DOC and hcAMB-DOC were more effective than AMB-DOC at 3 mg/kg: 100% survival (P ≤ 0.001 versus controls) and significant reduction (P ≤ 0.001) of the numbers of viable C. albicans organisms in the kidney 7 days after inoculation, compared to the time of treatment. Three of 10 mice even had culture-negative kidneys after hAMB-DOC treatment (Fig. 3A and Table 2). When treatment was delayed to 16 h after inoculation, AMB-DOC at 0.1 mg/kg, being the MTD in these severely infected mice, resulted in only a slight increase in survival rates (P ≤ 0.05) compared to the controls (Fig. 3B). A sixfold higher dose of hAMB-DOC or hcAMB-DOC (0.6 mg/kg) was tolerated by these infected mice. At this dose, treatment with either hAMB-DOC or hcAMB-DOC resulted in significantly prolonged survival of mice compared to controls (P ≤ 0.001) and compared to AMB-DOC treatment at 0.1 mg/kg (P ≤ 0.001). Survival after hAMB-DOC treatment was more prolonged than after hcAMB-DOC treatment (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 3B). For both derivates, numbers of viable C. albicans organisms in the kidney were higher than at the time of treatment (Table 2).

FIG. 3.

Effect of early (A) or delayed (B) treatment with AMB-DOC or its derivates on survival rates of persistently leukopenic mice with severe invasive candidiasis (Kaplan-Meier plot). Leukopenic mice were inoculated i.v. at time zero with 3 × 104 CFU of C. albicans. (A) Groups of 10 animals each were treated i.v. 6 h after C. albicans inoculation with a single dose of AMB-DOC (●), hAMB-DOC (▴), or hcAMB-DOC (▾) at 0.8 mg of AMB/kg. (B) Mice were treated 16 h after C. albicans inoculation with a single dose of AMB-DOC (●) at 0.1 mg of AMB/kg or with hAMB-DOC (▴) or hcAMB-DOC (▾), each at 0.6 mg of AMB/kg. Controls were treated with placebo (5-DW) (■). #, P ≤ 0.05 versus placebo-treated mice; ∗, P ≤ 0.001 versus placebo-treated mice.

TABLE 2.

Effects of early or delayed treatment with AMB-DOC or its derivates on survival of leukopenic micea and growth of C. albicans in the kidney

| Time of treatment | Drug usedb | Dose (mg of AMB/kg) | Log10 CFU/kidneyc at time of treatment | Day 7 after inoculation

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival rate (%) | Log10 CFU/kidneyc in surviving mice | No. of mice with sterile kidneys/no. of surviving mice | ||||

| 6 h | None (untreated) | 3.3 ± 0.2 | ||||

| Placebo (5-DW) | 0 | |||||

| AMB-DOC | 0.8 | 100 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 0/10 | ||

| hAMB-DOC | 0.8 | 100 | 5.0 ± 0.6 | 0/10 | ||

| hAMB-DOC | 3 | 100 | 1.0 ± 0.8d | 3/10 | ||

| hcAMB-DOC | 0.8 | 100 | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 0/10 | ||

| hcAMB-DOC | 3 | 100 | 1.3 ± 0.5d | 0/10 | ||

| 16 h | None (untreated) | 4.2 ± 0.1 | ||||

| Placebo (5-DW) | 0 | |||||

| AMB-DOC | 0.1 | 0 | ||||

| hAMB-DOC | 0.6 | 100 | 5.1 ± 0.7 | 0/10 | ||

| hcAMB-DOC | 0.6 | 60 | 5.8 ± 0.8 | 0/6 | ||

Leukopenic mice were inoculated i.v. at time zero with 3 × 104 CFU of C. albicans; untreated mice died within 3 days after C. albicans inoculation.

AMB-DOC, its derivates, and placebo were administered i.v.

Each value is the geometric mean ± SD.

Significant decrease (P ≤ 0.001) from number of CFU at the time of treatment.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, hAMB-DOC was prepared by heating (20 min, 70°C) a stock of conventional AMB-DOC (5 g/liter), suspended in the original vial according to the manufacturer's instructions. In a previous study on hAMB-DOC (2), the stock AMB-DOC was first diluted to 92 mg/liter (10−4 M) before heating. In the present study, spectroscopic measurements were performed for both conventional AMB-DOC and hAMB-DOC after dilution of the stock in aqueous solution (5-DW) to a concentration of 10 mg/liter. Absorption spectra were similar to those described previously by Gaboriau et al. (2), showing an absorption maximum at 327 nm for conventional AMB-DOC and at 322 nm for hAMB-DOC (data not shown). Therefore, it was concluded that hAMB-DOC could be adequately prepared by heating the original vial with stock AMB-DOC.

With respect to the particle size measurements of hAMB-DOC, it should be noted that because of the cobweb-like structure of the aggregates, the particle size could not be determined exactly. All of the methods for particle size measurements that are presently available are very accurate for perfectly round spheres, such as latex beads. Therefore, the results that were obtained in the present study should be interpreted with caution. It was clearly shown in the present study that hAMB-DOC consists of a homogenous suspension of aggregates with a mean particle size of about 300 nm. Only a very small fraction of the suspension (less than 5%) consists of much larger aggregates (particle sizes of 10 to 30 μm). For hcAMB-DOC a similar particle size distribution was observed, except that the particle size of the large aggregates ranged from 10 to 100 μm.

In the present study, it was demonstrated by measuring both cation release and viability of C. albicans that the potent antifungal activity of AMB-DOC is not reduced by heating, thereby confirming previous results (2) for which a different experimental method was used. With respect to the toxicity in vitro, it was shown that after heating of AMB-DOC, toxicity is greatly reduced as determined by RBC lysis, which is in accordance with previous results (2). In contrast, AMB-DOC and its derivates showed similar toxicity in terms of cation release from RBC. Gaboriau et al. (2) reported only a slight decrease (threefold) in permeabilizing activity (K+ release from RBC) after heating of AMB-DOC. As also discussed by Gaboriau et al. (2), these two distinct mechanisms of action of AMB (permeabilizing effects and lytic effects) are yet not clearly elucidated; therefore, the results cannot readily be explained. In our opinion, the in vitro toxicity of hAMB-DOC needs to be further investigated, focusing on other cell types and cell functions.

With respect to the in vivo toxicity, there is a striking difference between conventional AMB-DOC and its derivates. For conventional AMB-DOC, death was the dose-limiting event. At dosages above the MTD (0.8 mg/kg), immediate death of mice was observed, whereas no liver or renal toxicity was observed at the MTD. For both hAMB-DOC and hcAMB-DOC, immediate death was observed at dosages almost 10-fold higher (>7 mg/kg). However, liver toxicity was observed at much lower dosages (>3 mg/kg). Apparently, if treated with hAMB-DOC or hcAMB-DOC, mice are protected from the acute toxic effects seen with conventional AMB-DOC. The observed liver toxicity might be the result of increased AMB concentrations in the liver after administration of hAMB-DOC or hcAMB-DOC. The biodistribution in mice of AMB after administration of hAMB-DOC or AMB-DOC is presently under investigation. Next to organ distribution, it is important to further determine the cellular distribution of AMB, e.g., in the liver. It is assumed that the particles in hAMB-DOC will be primarily cleared from the circulation by the cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system in liver and spleen. It is important to investigate whether this might result in toxicity towards liver macrophages in terms of impaired phagocytic functions (13). It is also conceivable that during circulation in the blood, AMB is transferred from hAMB-DOC to lipoproteins (14), by which specific transport of AMB to hepatocytes might occur.

Therapeutic efficacy of AMB-DOC and its derivates was determined in a model of severe invasive candidiasis in persistently leukopenic mice. Previously, improved therapeutic efficacy of hAMB-DOC was demonstrated, compared to efficacy of conventional AMB-DOC, in a model of invasive candidiasis in immunocompetent mice (8). In that previous study, efficacy of treatment was investigated in terms of survival of mice only; quantitative cultures of viable C. albicans in the infected organs were not presented. In the present study, the experimental setup was deliberately chosen, as we wanted to investigate the potential of hAMB-DOC or hcAMB-DOC under very severe circumstances. It was clearly demonstrated that for both hAMB-DOC and hcAMB-DOC, higher dosages were tolerated than those for conventional AMB-DOC, resulting in significantly improved therapeutic efficacy. Furthermore, it became evident that the hAMB-DOC formulation is not further improved by centrifugation.

In our opinion this new approach of heating AMB-DOC may be of great value for further optimizing the treatment of severe fungal infections. At present, the therapeutic efficacy of hAMB-DOC is compared with that of conventional AMB-DOC in another clinically relevant model of severe invasive fungal infection, viz., pulmonary aspergillosis in persistently leukopenic rats (6).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Paul Bomans of the University of Maastricht for performing the cryo-transmission electron microscopy studies. We also thank Gabrie Meesters and Henk Merkus of the Delft University of Technology for sharing their expertise on particle technology and for performing the particle size measurements.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gaboriau F, Chéron M, Leroy L, Bolard J. Physicochemical properties of the heat induced ‘super’ aggregates of amphotericin B. Biophys Chem. 1997;66:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(96)02241-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaboriau F, Chéron M, Petit C, Bolard J. Heat-induced superaggregation of amphotericin B reduces its in vitro toxicity: a new way to improve its therapeutic index. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2345–2351. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hiemenz J W, Walsh T J. Lipid formulations of amphotericin B: recent progress and future directions. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22(Suppl. 2):S133–S144. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.supplement_2.s133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juliano R L, Grant C W M, Barber K R, Kalp M A. Mechanism of the selective toxicity of amphotericin B incorporated into liposomes. Mol Pharmacol. 1987;31:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leenders A C, de Marie S. The use of lipid formulations of amphotericin B for systemic fungal infections. Leukemia. 1996;10:1570–1575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leenders A C, de Marie S, ten Kate M T, Bakker-Woudenberg I A, Verbrugh H A. Liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) reduces dissemination of infection as compared to amphotericin B deoxycholate (Fungizone) in a rat model of pulmonary aspergillosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38:215–225. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehta R, Lopez-Berestein G, Hopfer R, Mills K, Juliano R L. Liposomal amphotericin B is toxic to fungal cells but not to mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;770:230–234. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(84)90135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petit C, Chéron M, Joly V, Rodrigues J M, Bolard J, Gaboriau F. In vivo therapeutic efficacy in experimental murine mycoses of a new formulation of desoxycholate-amphotericin B obtained by mild heating. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:779–785. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.6.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petit C, Yardley V, Gaboriau F, Bolard J, Croft S L. Activity of a heat-induced reformulation of amphotericin B deoxycholate (Fungizone) against Leishmania donovani. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:390–392. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson R F, Nahata M C. A comparative review of conventional and lipid formulations of amphotericin B. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1999;24:249–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.1999.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Etten E W M, van den Heuvel-de Groot C, Bakker-Woudenberg I A J M. Efficacies of amphotericin B-desoxycholate (Fungizone), liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) and fluconazole in the treatment of systemic candidosis in immunocompetent and leucopenic mice. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;32:723–739. doi: 10.1093/jac/32.5.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Etten E W M, ten Kate M T, Stearne L E T, Bakker-Woudenberg I A J M. Amphotericin B liposomes with prolonged circulation in blood: in vitro antifungal activity, toxicity, and efficacy in systemic candidiasis in leukopenic mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1954–1958. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.9.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Etten E W M, ten Kate M T, Snijders S V, Bakker-Woudenberg I A J M. Administration of liposomal agents and blood clearance capacity of the mononuclear phagocyte system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1677–1681. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wasan K M, Cassidy S M. Role of plasma lipoproteins in modifying the biological activity of hydrophobic drugs. J Pharm Sci. 1998;87:411–424. doi: 10.1021/js970407a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]