Abstract

Nikkomycin Z was tested both in vitro and in vivo for efficacy against Histoplasma capsulatum. Twenty clinical isolates were tested for susceptibility to nikkomycin Z in comparison to amphotericin B and itraconazole. The median MIC was 8 μg/ml with a range of 4 to 64 μg/ml for nikkomycin Z, 0.56 μg/ml with a range of 0.5 to 1.0 μg/ml for amphotericin B, and ≤0.019 μg/ml for itraconazole. Primary studies were carried out by using a clinical isolate of H. capsulatum for which the MIC of nikkomycin Z was greater than or equal to 64 μg/ml. In survival experiments, mice treated with amphotericin B at 2.0 mg/kg/dose every other day (QOD) itraconazole at 75 mg/kg/dose twice daily (BID), and nikkomycin Z at 100 mg/kg/dose BID survived to day 14, while 70% of mice receiving nikkomycin Z at 20 mg/kg/dose BID and none of the mice receiving nikkomycin Z at 5 mg/kg/dose BID survived to day 14. All vehicle control mice died by day 12. Fungal burden was assessed on survivors. Mice treated with nikkomycin Z at 20 and 100 mg/kg/dose BID had significantly higher CFUs per gram of organ weight in quantitative cultures and higher levels of Histoplasma antigen in lung and spleen homogenates than mice treated with amphotericin B at 2.0 mg/kg/dose QOD or itraconazole at 75 mg/kg/dose BID. Studies also were carried out with a clinical isolate for which the MIC of nikkomycin Z was 4 μg/ml. All mice treated with amphotericin B at 2.0 mg/kg/dose QOD; itraconazole at 75 mg/kg/dose BID; and nikkomycin Z at 100, 20, and 5 mg/kg/dose BID survived until the end of the study at day 17 postinfection, while 30% of the untreated vehicle control mice survived. Fungal burden assessed on survivors showed similar levels of Histoplasma antigen in lung and spleen homogenates of mice treated with amphotericin B at 2.0 mg/kg/dose QOD; itraconazole at 75 mg/kg/dose BID; and nikkomycin Z at 100, 20, and 5 mg/kg/dose BID. The three surviving vehicle control mice had significantly higher antigen levels in lung and spleen than other groups (P < 0.05). The efficacy of nikkomycin Z at preventing mortality and reducing fungal burden correlates with in vitro susceptibility.

Nikkomycin Z is an experimental compound that has been shown to exhibit antifungal properties (1, 8, 10). The nikkomycins are nucleoside analogs of UDP–N-acetylglucosamine. They act as competitive inhibitors of the fungal enzyme chitin synthase that polymerizes N-acetyl-glucosamine to form chitin, a structural fungal cell wall component (4). Three chitin synthase isozymes have been described extensively in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, each with a different role in cell wall synthesis (4, 7, 12). The susceptibility of an organism to nikkomycin Z would depend on both the chitin content and the difference in distribution and function of each of these chitin synthases (12). Nikkomycin Z in vitro has been shown to be active against dimorphic fungi such as Coccidioides immitis and Blastomyces dermatitidis (10). It has limited to no inhibition with true yeasts such as Cryptococcus neoformans, Candida albicans, and Candida tropicalis and is inactive against filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus fumigatus (4, 10; M. Flores and R. F. Hector, Abstr. 36th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-190, 1996).

Studies of experimentally induced histoplasmosis in animals have been useful in identifying antifungal agents for trials in humans (2, 13). In this report, we describe experiments evaluating the in vitro and in vivo activity of nikkomycin Z in histoplasmosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antifungal susceptibility testing.

Isolates of Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum (yeast phase) were grown for 4 days on brain heart infusion agar containing 5% sheep blood at 37°C. Yeasts were suspended in sterile saline and were adjusted to a McFarland standard of 5 at 530 nm. Each suspension was diluted in RPMI 1640 medium and was added to the drug dilutions.

Itraconazole (Janssen Pharmaceutica, Inc., Titusville, N.J.) was dissolved in polyethylene glycol (molecular weight of 200), nikkomycin Z (Shaman Pharmaceuticals, South San Francisco, Calif.) was diluted in 5% dextrose, and amphotericin B (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, N.J.) was diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide. Macrobroth suspensions were incubated at 37°C and read at 120 to 144 h by visual inspection. Candida parapsilosis ATCC 90018 was used as a control to ensure that the drug activity of the dilutions fell in the expected range. The MIC was defined as the dilution at which the turbidity was equal to or less than that of an 80% dilution of the no drug control for nikkomycin Z and itraconazole or the dilution which contained no observable growth for amphotericin B as recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (14).

Lethal dose determination.

Isolate 1 is a clinical isolate maintained by this laboratory for use specifically in animal models. The isolate is from an Indiana case of histoplasmosis in a pediatric cancer patient. The lethal dose for this isolate has been previously determined to be 105 in B6C3F1 mice (2). Isolate 2 was chosen for the second study based on differences in nikkomycin Z MICs for isolates 1 and 2 (>64 and 4 μg/ml, respectively). In comparison, isolate 2 is from an Indiana case of histoplasmosis in an adult AIDS patient. A lethal dose was determined for this isolate by infecting groups of mice with 1 × 105, 5 × 105, 1 × 106, or 5 × 106 yeasts and monitoring for mortality over a 19-day period.

Preparation of H. capsulatum yeast inoculum.

The yeast phase of H. capsulatum was grown in HMM medium (16) at 37°C with shaking at 150 rpm for 48 h. The yeast culture was centrifuged and washed with Hank's balanced salt solution containing 20 mM HEPES. The inoculum was adjusted by using a hemacytometer. For survival studies, isolate 1 was administered at a dose of 105 yeasts/mouse, and isolate 2 was administered at a dose of 5 × 105 yeasts/mouse.

Intratracheal mouse inoculation model.

Six-week-old B6C3F1 mice (Harlan Sprague-Dawley) were anesthetized with 4.5% halothane at an oxygen flow rate of 0.9 liters per min. A 20-gauge, 1-1/4-in. angiocath (Becton Dickinson) was passed through the mouth into the trachea, and 25 μl of the H. capsulatum inoculum was administered by stylet passed to the bifurcation of the trachea (6, 11).

Survival studies.

Mice received a lethal inoculum intratracheally. Treatment began 4 days after infection and continued for 10 days. Mice received amphotericin B (Fungizone) at 2.0 mg/kg/dose intraperitoneally every other day (QOD). Itraconazole (10 mg/ml of solution in hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin [gift of Janssen Pharmaceutica]) was given twice daily (BID) by gavage at 75 mg/kg/dose. Nikkomycin Z was diluted in 5% dextrose and given by gavage at 100, 20, and 5 mg/kg/dose BID. Control mice were treated by gavage with 5% dextrose alone. Ten mice were studied in each treatment group. Mice were held for 14 to 17 days, at which time survivors were sacrificed for fungal burden analysis.

Fungal burden assessment of survivors.

Surviving mice were sacrificed, and lungs and spleens were removed aseptically. Organs were weighed and then ground in Ten Broeck tissue grinders containing 2.0 ml of RPMI 1640 medium. Homogenates were diluted and plated on brain heart infusion agar containing 10% sheep blood. Plates were incubated for 10 to 14 days at 30°C, and colony counts were determined. Undiluted organ homogenates of 0.1 ml or 1/20 of the total organ were cultured, representing a detection limit of 20 CFU/organ. Quantitative culture data were expressed as CFU/gram by dividing the CFU/organ by the organ weights, ranging from about 0.169 to 0.503 g for lungs and 0.073 to 0.312 g for spleens for treated versus untreated mice, respectively. A detection limit of 67 CFU/gram of organ weight for the lungs and 200 CFU/gram of organ weight for the spleen can be determined by using a mean organ weight of 0.3 and 0.1 g for the lung and spleen, respectively. Any values less than the detection limit were considered to represent 0 CFU/organ in these experiments.

Histoplasma antigen was measured in organ homogenates by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (5). Dilutions of the organ homogenates (1:10 for spleen and 1:100 for lung) were made to fall within the working range of the assay. The EIA results are expressed as EIA units (EU) by dividing the mean value obtained for each organ homogenate by 1.5 times the mean value of the negative controls. Results of greater than or equal to 1.0 were considered positive.

Statistical analysis.

A Wilcoxon test for survival analysis was used to compare the survival times for the different treatments of each isolate. An analysis of variance was performed on the ranks of the antigen and quantitative cultures (3). Tukey's multiple comparison adjustment was used for making pair-wise comparisons among the treatment groups. An overall significance level of α = 0.05 was used to test all hypotheses.

RESULTS

Antifungal susceptibility.

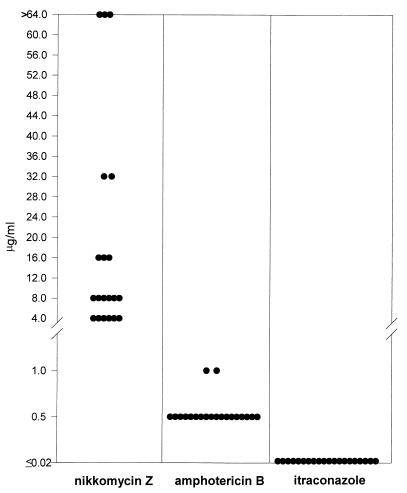

The MICs of nikkomycin Z, itraconazole, and amphotericin B were determined by testing 20 patient isolates of H. capsulatum following the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards guidelines for yeasts with modifications made in our laboratory for H. capsulatum (Fig. 1). MICs for nikkomycin Z ranged from 4 to ≥ 64 μg/ml, with a mean of 18.8 μg/ml, a median of 8 μg/ml, and a MIC at which 90% of the isolates tested are inhibited (MIC90) of ≥64 μg/ml. In comparison, amphotericin B MICs had a range of 0.5 to 1.0 μg/ml with a mean of 0.55 μg/ml, a median of 0.50 μg/ml, and a MIC90 of 0.5 μg/ml. MICs to itraconazole were ≤0.019 μg/ml for every isolate.

FIG. 1.

MICs of amphotericin B, itraconazole, and nikkomycin Z for the yeast phase organisms of 20 clinical isolates of H. capsulatum. The lowest concentrations tested for the antifungal agents were as follows: amphotericin B, 0.031 μg/ml; itraconazole, 0.019 μg/ml; and nikkomycin Z, 0.125 μg/ml.

Survival following an infection with isolate 1.

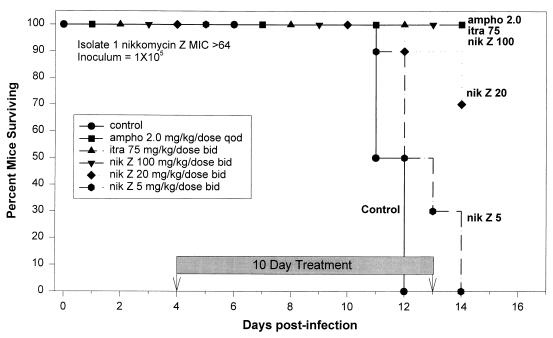

Survival studies used an inoculum of 105 yeasts (Fig. 2). All mice treated with amphotericin B at 2.0 mg/kg/dose QOD, itraconazole at 75 mg/kg/dose BID, and nikkomycin Z at 100 mg/kg/dose BID survived to day 14. Thirty percent of the mice treated with nikkomycin Z at 20 mg/kg/dose BID died between days 12 and 14, with the remaining 70% surviving to day 14. Mice treated with nikkomycin Z at 5 mg/kg/dose BID all died between days 11 and 14. All of the untreated control mice died between days 11 and 12. Log-rank test for survival analysis showed that there was a significant difference among these survival curves (P = 0.0001).

FIG. 2.

Survival following intratracheal infection with 105 H. capsulatum yeasts of isolate 1 (nikkomycin Z MIC, >64). Therapy was given from days 4 to 13. The no drug control group received gavage BID with 5% dextrose used to dilute nikkomycin Z. There were 10 animals in each group. Survivors were sacrificed at day 14.

Fungal burden analysis of survivors of infection with isolate 1.

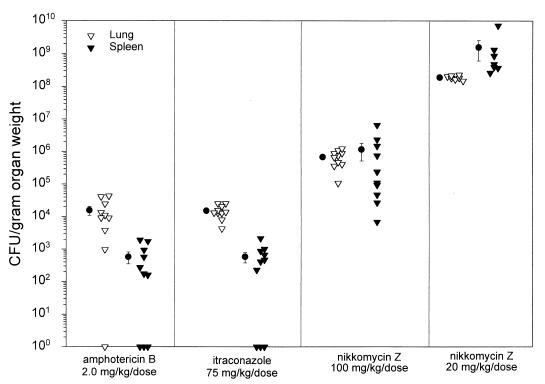

Mice that survived the infection were sacrificed on day 17. Fungal burden was determined by comparing quantitative cultures from spleen and lung homogenates (Fig. 3). Treatment of mice infected with an inoculum of 105 yeasts with nikkomycin Z at 100 and 20 mg/kg/dose BID was unable to reduce the fungal burden in the lungs and spleen as effectively as treatment with amphotericin B at 2.0 mg/kg/dose QOD or itraconazole at 75 mg/kg/dose BID, P < 0.05 (Table 1). There are no data for untreated animals since all died by day 12.

FIG. 3.

Quantitative culture results of lung and spleen tissue from mice surviving to day 14 following infection with 105 H. capsulatum yeasts of isolate 1 (nikkomycin Z MIC, >64). Each triangle represents one animal, and the circles represent the means of each group. There were 7 to 10 mice in each study group. None of the nikkomycin Z 5-mg/kg/dose-BID mice survived to day 14. The minimum detection limit was 20 CFU/organ, representing 67 to 200 CFU/g of tissue. Individual platings for the nikkomycin Z 20-mg/kg/dose-BID group were too numerous to count. Animals from this group were assigned a colony count of 400 per plate, based on the highest number of colonies which were individually counted per plate. After conversion to CFU per gram of organ weight, results were used for graphing and statistical analysis.

TABLE 1.

Fungal burden in the lungs and spleen of mice that survived to day 14 after infection with 105 CFU of H. capsulatum (isolate 1; nikkomycin Z MIC, ≥64 μg/ml)

| Drug and dose (mg/kg) | n | Antigen (EU) median (range)

|

Quantitative culture median (CFU/g of organ weight)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | Spleen | Lung | Spleen | ||

| Amphotericin B (2.0) | 10 | 10.6 (6.6–16.1) | 7.6b (5.1–21.1) | 1.0 × 104 | 2.2 × 102 |

| Itraconazole (75) | 10 | 8.7 (6.6–9.6) | 3.8a (3.5–14.8) | 1.3 × 104 | 4.3 × 102 |

| Nikkomycin Z (100) | 10 | 14.5b (12.1–19.0) | 14.1ab (12.0–20.1) | 6.8 × 105a,b | 1.7 × 105a,b |

| Nikkomycin Z (20) | 7 | 17.3ab (14.9–19.2) | 16.8ab (13.8–21.2) | 1.8 × 108a,b | 4.7 × 108a,b |

P ≤ 0.05 in comparison to mice treated with amphotericin B.

P ≤ 0.05 in comparison to mice treated with itraconazole.

Antigen testing was performed on organ homogenates for surviving mice and produced results comparable to the culture data. In summary, antigen levels were higher in the nikkomycin Z 100- and 20-mg/kg/dose-BID-treated groups than in the amphotericin B and itraconazole 75-mg/kg/dose-BID-treated group, P < 0.05 for lung and spleen homogenates (Table 1).

Survival following an infection with isolate 2.

In preparation to assess the effectiveness of nikkomycin Z for an isolate for which the agent had lower MIC (4 μg/ml), a series of inocula were tested to define the lethal dose. Survival was monitored over a 19-day period in mice infected with an inoculum of 1 × 105, 5 × 105, 1 × 106, or 5 × 106 yeasts. All mice survived until day 10, when 90% of mice receiving the highest inoculum died. Mice receiving 5 × 105 yeasts died between days 11 and 13. Mice receiving 106 yeasts died between days 10 and 13, while mice receiving the lowest dose of 105 yeasts died between days 13 and 17. There was a significant difference between survival curves for the four inocula (P = 0.00070).

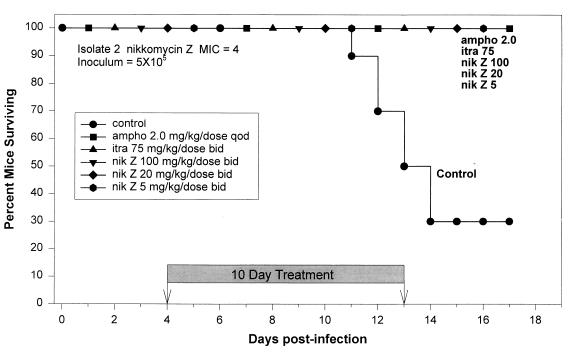

An inoculum of 5 × 105 was chosen to evaluate antifungal therapy of mice infected with isolate 2. All mice that received amphotericin B at 2.0 mg/kg/dose QOD; itraconazole at 75 mg/kg/dose BID; or nikkomycin Z at 100, 20, or 5 mg/kg/dose BID survived until the end of the study at day 17 postinfection (Fig. 4). However, the mice in the nikkomycin Z 5-mg/kg/dose-BID group had lost weight, appeared dehydrated, groomed poorly, and were presumed to be near death. Most untreated control mice died between days 11 and 14, but 30% survived to the completion of the study. Survival was significantly better in the treated mice than in the control mice (P = 0.0001).

FIG. 4.

Survival following intratracheal infection with 5 × 105 H. capsulatum yeasts of isolate 2 (nikkomycin Z MIC, 4). Therapy was given from days 4 to 13. The no drug control group received gavage BID with 5% dextrose used to dilute nikkomycin Z. There were 10 animals in each group. Survivors were sacrificed at day 17.

Fungal burden analysis of survivors of infection with isolate 2.

Fungal burden was determined on mice that survived to day 17 of infection. Three untreated control animals survived to day 17 and appeared to be recovering from the infection. Thus, they were sacrificed for fungal burden determination (Fig. 4). Based on the results with isolate 1, higher CFU were anticipated for this study. Due to restrictions on the number of dilutions which can be done for quantitative culture, we chose dilutions of 1/103, 1/104, 1/105, and 1/106 for the untreated controls. The results of the 1/103 dilution were negative for the spleen; this dilution would have required a CFU of greater than or equal to 8.6 × 104/g of organ weight to yield a positive result. Lung tissue of the three surviving control mice contained a median of 9.0 × 105 CFU/g of organ weight. Culture data was fully evaluated for the amphotericin B 2.0-mg/kg/dose-QOD and itraconazole 75-mg/kg/dose-BID treatment groups (Table 1). Bacterial contamination of culture plates prevented evaluation of all organ homogenates for the nikkomycin Z 100- and 20-mg/kg/dose-BID treatment groups. Two mice were evaluable for lung homogenates and four mice were evaluable for the spleen homogenates of the nikkomycin Z 20-mg/kg/dose-BID treatment group. Five mice that were evaluable in the nikkomycin Z 100-mg/kg/dose-BID treatment group had median quantitative cultures of 0 CFU/g in the spleen (Table 2). The results of the 1/10 dilution for the lung homogenates were negative. To yield a positive result, this dilution would have required a minimum CFU of greater than or equal to 1.2 × 103/g. The nikkomycin Z 5-mg/kg/dose-BID treatment group was not evaluated due to overdilution of the homogenates. The results of the 1/102 dilution for lung and spleen were negative. At this dilution, a minimum CFU of greater than or equal to 9.1 × 103/g for the lung and greater than or equal to 1.9 × 104/g for the spleen would have been required to yield a positive result. Reduction in fungal burden was not as effective in the itraconazole 75-mg/kg/dose-BID and nikkomycin Z 20-mg/kg/dose-BID treatment groups as in the group treated with amphotericin B at 2.0 mg/kg/dose QOD (P < 0.05).

TABLE 2.

Fungal burden in the lungs and spleen of mice that survived to day 17 after infection with 5 × 105 CFU of H. capsulatum (isolate 2; nikkomycin Z MIC, 4 μg/ml)

| Drug and dose (mg/kg) | n | Antigen (EU) median (range)

|

Quantitative culture median (CFU/g of organ weight)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | Spleen | Lung | Spleen | ||

| Amphotericin B (2.0) | 10 | 2.9a (2.5–6.4) | 1.2a (0.9–5.1) | 0a | 0 |

| Itraconazole (75) | 10 | 4.2a (1.7–5.9) | 1.7a (0.8–2.0) | 3.3 × 102a,b,c | 7.5 × 102b,c |

| Nikkomycin Z (100) | 7 | 3.2a (1.7–3.4) | 1.2a (0.9–1.8) | NEf | 0d |

| Nikkomycin Z (20) | 8 | 2.9a (2.5–5.0) | 1.4a (1.0–2.8) | 1.1 × 103b,e | 6.4 × 102b,e |

| Nikkomycin Z (5) | 8 | 3.8 (3.4–4.4) | 2.5b (2.0–5.9) | NE | NE |

| Control | 3 | 13.6 (12.4–14.1) | 13.4 (11.8–14.0) | 9.0 × 105b | NE |

P < 0.05 in comparison to untreated controls.

P < 0.05 in comparison to mice treated with amphotericin B.

Eight of ten mice evaluable for lung homogenates; 9 of 10 mice evaluable for spleen homogenates.

Five of seven mice evaluable for spleen homogenates.

Two of eight mice evaluable for lung homogenates; 4 of 8 mice evaluable for spleen homogenates.

NE, nonevaluable due to either overdilution of homogenates or bacterial contamination of plates.

Antigen levels were determined for all treatment groups (Table 2). Untreated controls had a median antigen level of 13.6 EU in the lung and 13.4 EU in the spleen. Similar results were seen with the itraconazole 75-mg/kg/dose-BID and nikkomycin Z 100- and 20-mg/kg/dose-BID treatment groups. Antigen levels in the nikkomycin Z 5-mg/kg/dose-BID treatment group were not significantly different than untreated controls with median antigen levels in the lung and spleen of 3.8 and 2.5 EU, respectively. Fungal burden studies showed that nikkomycin Z at 100 and 20 mg/kg/dose BID and amphotericin B at 2.0 mg/kg/dose QD significantly reduced fungal burden in lung and spleen tissues as measured by Histoplasma antigen levels in comparison to untreated controls (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

By intratracheally infecting mice, this model imitates the infectious process seen in humans after inhalation of H. capsulatum conidia. This route of inoculation results in diffuse pulmonary infiltrates and subsequent dissemination to the liver and spleen (6). The severity of infection in this model is related to inoculum size and the immune status of the host (C. Schnizlein-Bick, M. Durkin, P. Connolly, S. Kohler, and J. Wheat, Program Abstr. 34th Ann. Meet. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 1996, abstr. 207, p. 74, 1996). H. capsulatum causes a self-limited infection in immunocompetent animals exposed to a lesser inoculum but a progressive fatal infection in mice administered higher inocula or in those that are immunosuppressed (6, 9). Similar features are seen in humans with histoplasmosis (15).

Nikkomycin Z was less active in vitro than amphotericin B or itraconazole against H. capsulatum, with MICs ranging from 4 to ≥ 64 μg/ml. When studies were performed with isolate 1 (MIC, ≥ 64 μg/ml), nikkomycin Z at 100 mg/kg/dose BID was as effective at preventing death as amphotericin B at 2.0 mg/kg/dose QOD and itraconazole at 75 mg/kg/dose BID with 100% survival at day 14. However, nikkomycin Z at 100 mg/kg/dose BID was less effective at reducing fungal burden in the lungs and spleen than either amphotericin B or itraconazole (Table 3). Lower doses of nikkomycin Z were less effective at preventing death or reducing fungal burden.

TABLE 3.

P values of pair-wise comparison of fungal burden data for isolate 1 (nikkomycin MIC, ≥64 μg/ml)

| Agents compared (mg/kg/dose) | Antigen

|

Quantitative culture

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | Spleen | Lung | Spleen | |

| Amphotericin B (2.0) to itraconazole (75) | NSa | 0.0124 | NS | NS |

| Amphotericin B (2.0) to nikkomycin Z (100) | NS | 0.0244 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Amphotericin B (2.0) to nikkomycin Z (20) | <0.0001 | 0.0014 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Itraconazole (75) to nikkomycin Z (100) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Itraconazole (75) to nikkomycin Z (20) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Nikkomycin Z (100) to nikkomycin Z (20) | 0.0373 | NS | 0.0052 | <0.0001 |

NS, not significant; P > 0.05

Studies with a second isolate which was more susceptible (nikkomycin Z MIC, 4 μg/ml) showed nikkomycin Z at all doses to be as effective as amphotericin B and itraconazole at preventing mortality (Table 4). Antigens in tissues of mice infected with isolate 2 showed a statistically significant reduction in fungal burden for amphotericin B and nikkomycin Z at 100 and 20 mg/kg/dose BID as compared to the untreated controls, supporting the increased efficacy of nikkomycin Z for this isolate (Table 2). Culture data could not be fully evaluated for all treatment groups due to either overdilution of organ homogenates or bacterial contamination of culture plates. Culture data showed that nikkomycin Z at 100 mg/kg/dose BID in the spleen was as effective as amphotericin B at reducing fungal burden. No culture data was available for the nikkomycin Z 5-mg/kg/dose-BID treatment group. In earlier studies, we have shown that antigen detection yields results which approximate those obtained by culture, supporting the validity of the data obtained in this experiment (2).

TABLE 4.

P values of pair-wise comparison of fungal burden data for isolate 2 (nikkomycin Z MIC, 4 μg/ml)

| Agents compared (mg/kg/dose) | Antigen

|

Quantitative cultureb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | Spleen | Lung | Spleen | |

| Control to amphotericin B (2.0) | 0.0026 | 0.0010 | <0.0001 | |

| Control to itraconazole (75) | NSa | 0.0369 | <0.0001 | |

| Control to nikkomycin Z (100) | 0.0041 | 0.0004 | ||

| Control to nikkomycin Z (20) | 0.0015 | 0.0038 | NS | |

| Control to nikkomycin Z (5) | NS | NS | ||

| Amphotericin B (2.0) to itraconazole (75) | NS | NS | <0.0001 | 0.0002 |

| Amphotericin B (2.0) to nikkomycin Z (100) | NS | NS | NS | |

| Amphotericin B (2.0) to nikkomycin Z (20) | NS | NS | <0.0001 | 0.0088 |

| Amphotericin B (2.0) to nikkomycin Z (5) | NS | 0.0013 | ||

| Itraconazole (75) to nikkomycin Z (100) | NS | NS | 0.0006 | |

| Itraconazole (75) to nikkomycin Z (20) | 0.0305 | NS | 0.0078 | NS |

| Itraconazole (75) to nikkomycin Z (5) | NS | NS | ||

| Nikkomycin Z (100) to nikkomycin Z (20) | NS | NS | 0.0149 | |

| Nikkomycin Z (100) to nikkomycin Z (5) | NS | 0.0005 | ||

| Nikkomycin Z (20) to nikkomycin Z (5) | NS | 0.0089 | ||

NS, not significant (P > 0.05).

Blank cells indicate that no comparison was made due to an insufficient number of evaluable samples in the control or nikkomycin Z groups.

Two previous murine studies evaluating nikkomycin Z for treatment of histoplasmosis yielded somewhat different results than those obtained in our study (8, 10). In contrast to our model, these studies utilized an intravenous infection route, different laboratory isolates of H. capsulatum, and a treatment protocol beginning on day-2 postinfection. Hector et al. showed that 5 mg/kg/dose of nikkomycin Z increased survival rates after infection with 5 × 106 yeasts (MICs were not reported). Fungal burden studies showed that nikkomycin Z at 20 mg/kg/dose reduced CFU per gram in liver or spleen to levels similar to those seen after treatment with fluconazole (10). However, in unpublished studies in our laboratory, fluconazole was less active than amphotericin B or itraconazole at reducing fungal burden. A second study by Graybill et al, using an isolate for which the MIC of nikkomycin Z was 0.5 μg/ml, showed a significant increase in survival with nikkomycin Z administered at greater than 2.5 mg/kg/dose BID as compared to untreated controls (8). Fungal burden studies showed nikkomycin Z at 2.5 mg/kg/dose BID to significantly reduce quantitative counts in liver and spleen tissue. These findings are consistent with our observations using the more sensitive isolate.

In conclusion, nikkomycin Z at higher doses was as effective as amphotericin B or itraconazole for the treatment of mice infected with more-susceptible strains of H. capsulatum. Susceptibility to nikkomycin Z, however, was highly variable, with MICs for the agent of 16 μg/ml and higher in 40% of the isolates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clemons K V, Stevens D A. Efficacy of nikkomycin Z against experimental pulmonary blastomycosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2026–2028. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connolly P, Wheat J, Schnizlein-Bick C, Durkin M, Kohler S, Smedema M, Goldberg J, Brizendine E, Loebenberg D. Comparison of a new triazole antifungal agent, Schering 56592, with itraconazole and amphotericin B for treatment of histoplasmosis in immunocompetent mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:322–328. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conover W J, Iman R L. Rank transformations as a bridge between parametric and nonparametric statistics. Am Statistician. 1981;35:124–129. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debono M, Gordee R S. Antibiotics that inhibit fungal cell wall development. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:471–497. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.002351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durkin M M, Connolly P A, Wheat L J. Comparison of radioimmunoassay and enzyme-linked immunoassay methods for detection of Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2252–2255. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2252-2255.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fojtasek M F, Sherman M R, Garringer T, Blair R, Wheat L J, Schnizlein-Bick C T. Local immunity in lung-associated lymph nodes in a murine model of pulmonary histoplasmosis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4607–4614. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4607-4614.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaughran J, Lai M, Kirsch D, Silverman S. Nikkomycin Z is a specific inhibitor of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chitin synthase isozyme Chs3 in vitro and in vivo. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5857–5860. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5857-5860.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graybill J R, Najvar L K, Bocanegra R, Hector R F, Luther M F. Efficacy of nikkomycin Z in the treatment of murine histoplasmosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2371–2374. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.9.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graybill J R, Patino M M, Gomez A M, Ahrens J. Detection of histoplasmal antigens in mice undergoing experimental pulmonary histoplasmosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132:752–756. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.132.4.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hector R F, Zimmer B L, Pappagianis D. Evaluation of nikkomycins X and Z in murine models of coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, and blastomycosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:587–593. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.4.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohler S, Blair R, Schnizlein-Bick C, Fojtasek M, Connolly-Stringfield P, Wheat J. Clearance of Histoplasma capsulatum variety capsulatum antigen is useful for monitoring treatment of experimental histoplasmosis. J Clin Lab Anal. 1994;8:1–3. doi: 10.1002/jcla.1860080102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurtz M B. New antifungal drug targets: a vision for the future. ASM News. 1998;64:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pappagianis D, Zimmer B L, Theodoropoulos G, Plempel M, Hector R F. Therapeutic effect of the triazole bay R 3783 in mouse models of coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, and histoplasmosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1132–1138. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waitz J A, Bartlett M S, Ghannoum M A, Espinel-Ingroff A, Lancaster M V, Odds F C, Pfaller M A, Rex J H, Rinaldi M G, Walsh T J, Galgiani J N. Reference method of broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; approved standard. 1997. pp. 1–29. . Report M27-A. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wheat J. Histoplasmosis: experience during outbreaks in Indianapolis and review of the literature. Medicine. 1997;76:339–354. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199709000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Worsham P L, Goldman W E. Quantitative plating of Histoplasma capsulatum without addition of conditioned medium or siderophores. J Med Vet Mycol. 1988;26:137–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]