Abstract

Recent high-profile reports have reignited an interest in acetate metabolism in cancer. Acetyl-CoA synthetases that catalyse the conversion of acetate to acetyl-CoA have now been implicated in the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma, glioblastoma, breast cancer and prostate cancer. In this Review, we discuss how acetate functions as a nutritional source for tumours and as a regulator of cancer cell stress, and how preventing its (re)capture by cancer cells may provide an opportunity for therapeutic intervention.

The first comprehensive studies on acetate metabolism in cancer were reported in the 1950s by Sidney Weinhouse and as part of a series of letters on lipid metabolism and metabolic changes induced in response to substrate availability in neoplastic tissues1–3. Weinhouse was a pioneer in the use of isotopic tracers to study cancer metabolism. His studies on substrate competition between glucose, fatty acids and acetate demonstrated not only that acetate can be used to fuel tumour respiration but that oxidation of acetate, unlike that of fatty acids, was refractory to increases in the glucose concentration (for example, the Crabtree effect)3. His findings hinted that acetate may be uniquely controlled, even exploited, by cancer cells and that it represents an important respiratory substrate.

Crabtree effect.

The phenomenon whereby aerobic fermentation of glucose occurs and respiration is inhibited if the glucose concentration surpasses a threshold value.

At the same time that Weinhouse was studying the metabolic nature of cancer cells, the ideas of tumour hypoxia and intratumoural heterogeneity, in terms of nutrient availability, were just beginning to come to light4. It is now appreciated that cancer cells within metabolically stressed microenvironments, herein defined as those with low oxygen and low nutrient availability, adopt many tumour-promoting characteristics, such as genomic instability, altered cellular bioenergetics and invasive behaviour5,6. In addition, these cancer cells are often intrinsically resistant to cell death and their physical isolation from the vasculature at the tumour site can compromise successful immune responses7, drug delivery and therapeutic efficiency8, thereby promoting relapse and metastasis, which ultimately translates into drastically reduced patient survival6. Therefore, there is an absolute requirement to define therapeutic targets in metabolically stressed cancer cells and to develop new delivery techniques to increase therapeutic efficacy. For instance, the particular metabolic dependence of cancer cells on alternative nutrients (such as acetate) to support energy and biomass production may offer opportunities for the development of novel targeted therapies.

In this Review, we aim to identify the sites of production and availability of acetate as a nutritional source for cancer cells and to discuss the current hypotheses concerning the intracellular fate of acetate. Furthermore, we discuss how non-invasive imaging of acetate uptake and metabolism by cancer cells may contribute to patient diagnosis and stratification as well as to monitoring cancer progression, responsiveness to therapy and drug efficacy. Altogether, we hope to enlighten the reader on how acetate may serve as an alternative lipogenic and bioenergetic source for metabolically stressed cancer cells.

Availability of acetate

Exogenous and endogenous acetate sources.

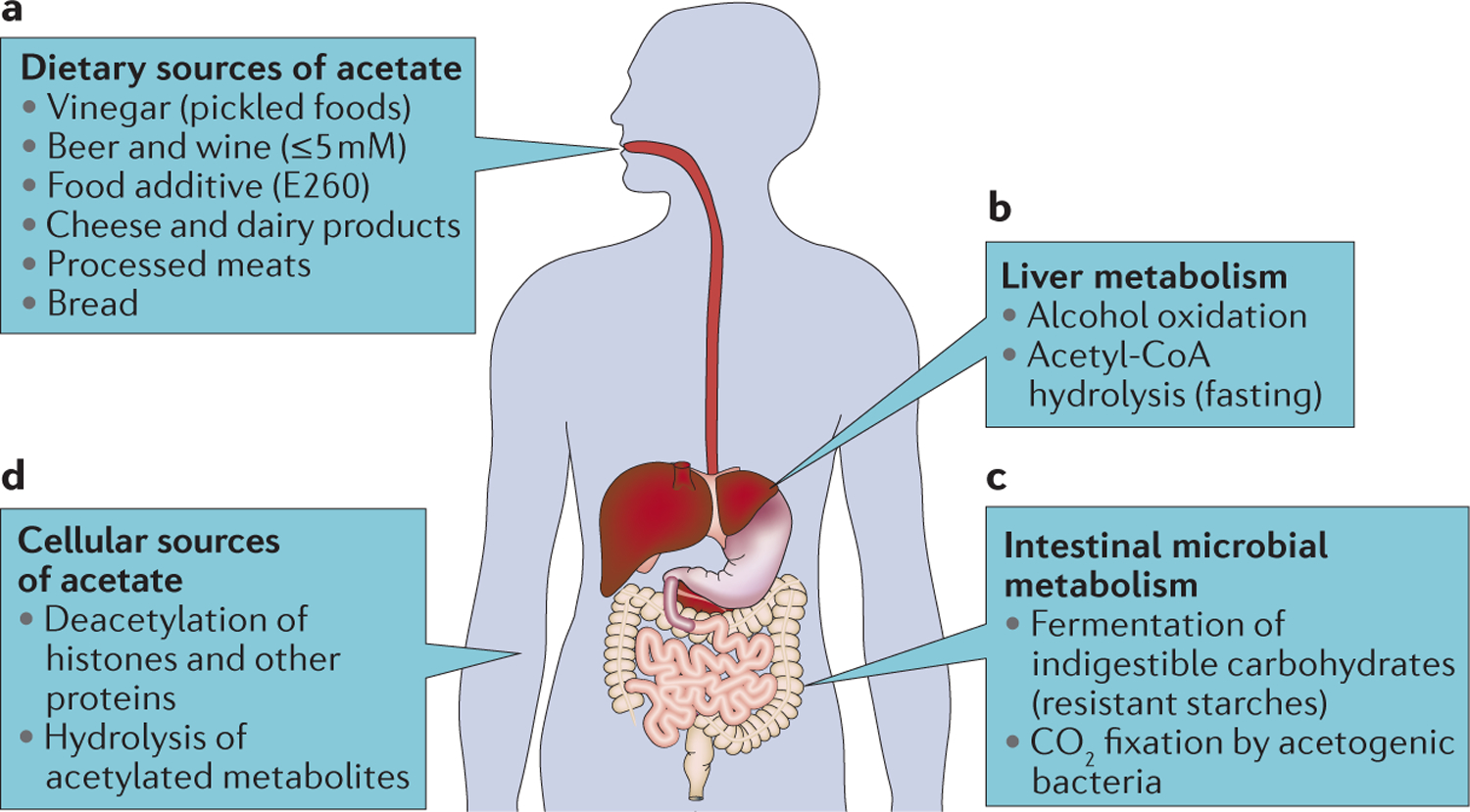

Acetate levels in different tissues of the human body are determined by both exogenous sources and endogenous production. According to the Codex General Standard for Food Additives (GSFA), the major dietary sources of acetate are acetate-containing foods (for example, cheese and other dairy products, processed meats and bread), ethanol and indigestible carbohydrates9 (FIG. 1). In addition, acetate can be liberated from acetylated metabolites within the body. For instance, during fasting, an acetyl-CoA hydrolase called acyl-CoA thioesterase 12 (ACOT12) becomes activated and generates free acetate from acetyl-CoA in the liver (FIG. 1) that can be released into the circulation and metabolized elsewhere in the body as needed10–12.

Figure 1 |. Sources and production sites of acetate in the human body.

a | The three main dietary sources of acetate are acetate-containing foods, ethanol and dietary fibres such as resistant starches, indigestible oligosaccharides and other plant-derived polysaccharides. Acetate is found in pickled foods, cheese and other dairy products, processed meats, bread, wine and beer, and is also added to some foods as an emulsifier, acidity regulator or preservative. b | The liver is the main site for alcohol detoxification and the production of acetate from acetyl-CoA during conditions of fasting. c | The commensal microbiota is the main source of acetate within the human body. Bacteria break down indigestible polysaccharides to generate large amounts of short-chain fatty acids in the gut, the most abundant of which is acetate. In addition, bacteria have the ability to fix CO2-derived carbon. d | Apart from these major production sites, there can also be more localized production of acetate through the deacetylation of histones, other proteins and metabolites.

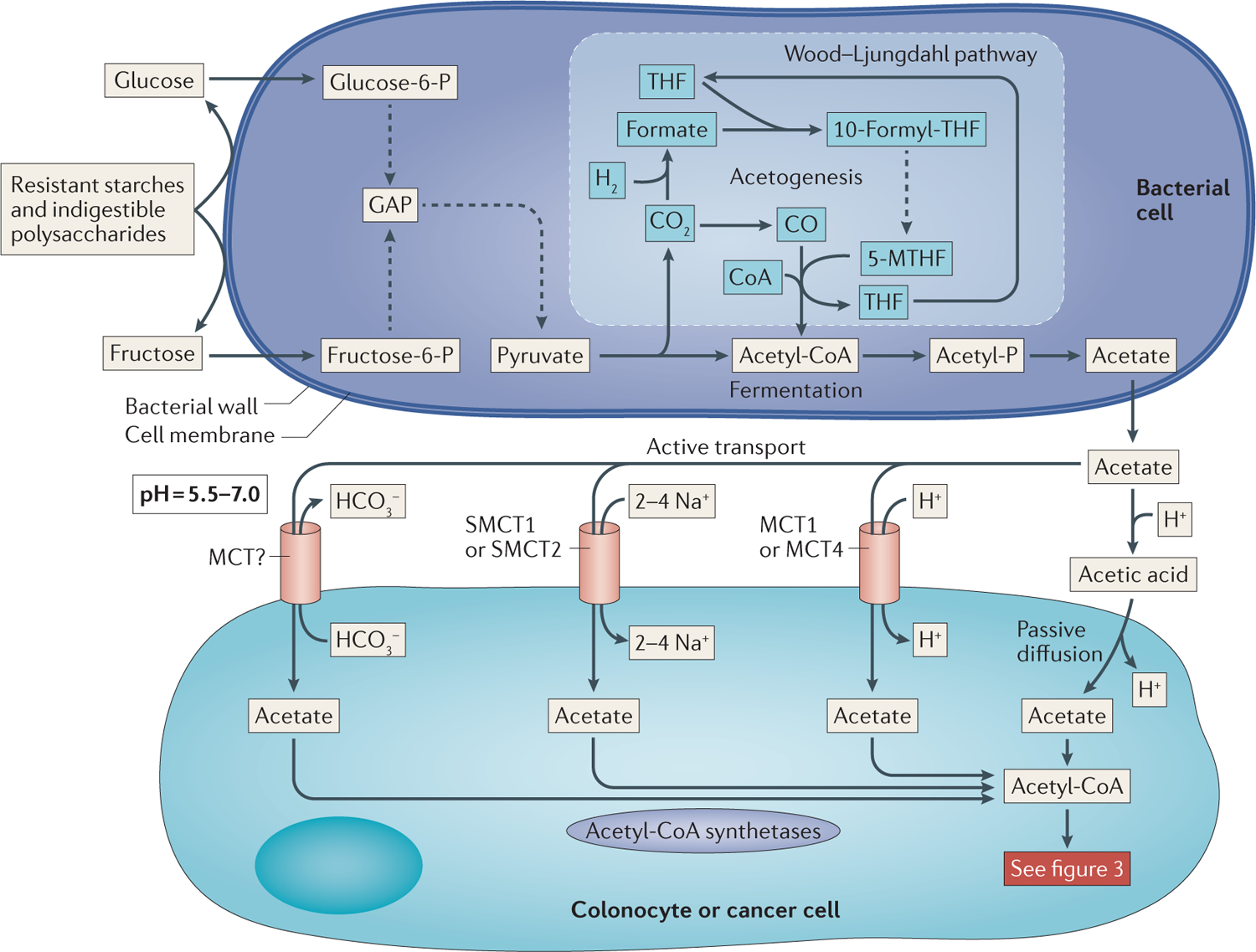

Plasma acetate in mammals is primarily generated through the breakdown of dietary fibres by the intestinal microbiota through two metabolic pathways: saccharolytic fermentation or acetogenesis (FIGS 1,2). Fermentation of complex polysaccharides by bacteria residing in the lumen and mucosal layers of the colon results in high concentrations of the short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) acetate, propionate and butyrate (with a combined concentration of 50–150 mM) that invariably remain in a 3:1:1 ratio13. The concentration of SCFAs is highest in the ascending colon and gradually decreases from the transverse to the descending colon and rectum14. However, the difficulty in obtaining samples other than faecal matter from healthy volunteers has meant that only a few reports on the acetate concentration in the different sections of the human large intestine are available. Acetate is produced by most species of intestinal bacteria through fermentation of pyruvate via acetyl-CoA (FIG. 2). In addition, acetogenic bacteria can produce acetate from CO2 and H2 via the reductive Wood–Ljungdahl pathway15 (FIG. 2). Such facultative autotrophs can produce three molecules of acetate from one molecule of glucose or fructose15,16. SCFAs are efficiently absorbed from the mammalian gut lumen and can serve as an energy source for colonocytes17, which consume the majority of the butyrate produced in the colon14. The remaining SCFAs enter the liver through the portal vein, where the relative concentration of acetate becomes enriched owing to the metabolism of the gluconeogenic precursor propionate by hepatocytes14,18. The remaining acetate is released into the bloodstream, where it is consumed and oxidized by peripheral tissues. Taken together, the vast majority of circulating acetate, the concentration of which ranges from 50 μM to 200 μM in human plasma, is directly attributable to prokaryotic metabolism in the gut (TABLE 1).

Figure 2 |. Production of acetate by the commensal microbiota and the subsequent uptake by colonic epithelial cells.

Resistant starches and other indigestible polysaccharides are broken down on the surface of bacterial cells by carbohydrate-degrading enzymes (top panel). These hexoses enter the cell and are converted, through glycolysis, into pyruvate. Pyruvate in turn is converted into acetyl-CoA and CO2. Phosphotransacetylases exchange a phosphate for CoA to form acetyl-phosphate (acetyl-P). Acetate kinase catalyses the transfer of the phosphate from acetyl-P to ADP, which generates ATP and acetate. Alternatively, the CO2 released from pyruvate decarboxylation can enter the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway, which uses reductive acetogenesis to form acetyl-CoA from CO and 5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF). Once formed, acetate can be exported from the bacterial cell into the lumen of the gut, where it is absorbed by one of two methods by the colonic epithelium (bottom panel). The first mechanism is passive diffusion of the protonated form of acetate, acetic acid, which is facilitated by the extremely high concentrations of acetate and the relatively low pH in the proximal colon and caecum. The second route of entry is through the active transport of acetate by monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs), in which acetate is co-transported with Na+ or H+ or exchanged for HCO3−. Dashed lines represent multistep reactions. 10-formyl-THF, 10-formyl-tetrahydrofolate; GAP, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; glucose-6-P, glucose-6-phosphate; fructose-6-P, fructose-6-P; SMCT, sodium-coupled MCT; THF, tetrahydrofolate.

Table 1 |.

Acetate concentrations in human tissues

| Tissue | [Acetate] (mM)* | Range (mM)‡ | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portal vein | 0.219 ± 0.123 | 0.128–0.375 | 14,18,106,107 |

| Arterial plasma | 0.140 ± 0.052 | 0.056–0.212 | 108–113 |

| Venous plasma | 0.074 ± 0.035 | 0.035–0.140 | 12,14,106,107,112, 114–118 and Z.T.S., L Zheng and E.G., unpublished observations |

| Plasma (post-alcohol)§ | 0.621 ± 0.101 | 0.520–0.760 | 20,21,115,119 |

| Plasma (post-fibre)║ | 0.193 ± 0.068 | 0.114–0.295 | 12,109,111,112,120 |

Plasma acetate concentrations are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. of the values reported in the cited references. Participants in these studies were typically fasted overnight before analyses. In all cases, efforts were made to ensure values are representative of normal, healthy individuals, with the exception of the alcohol studies, which did include some alcoholic patients.

The range represents the lowest and highest mean acetate concentration reported for each particular tissue.

For alcohol studies, volunteers were administered ethanol and plasma acetate concentrations were monitored at various time points for up to 8 hours.

For the fibre studies, subjects were typically fasted overnight and then placed on a starch diet (30–60 g) or administered lactulose (10–20 g).

Short-chain fatty acids.

(SCFAs). Fatty acids with an aliphatic tail of two to six carbon atoms. The SCFAs acetate, propionate and butyrate are abundantly produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary carbohydrates in the colon.

Facultative autotrophs.

Organisms that can grow using organic carbon but are also able to assimilate organic carbon from inorganic carbon sources such as CO2.

Acetate can be produced in the liver by oxidative catabolism of alcohol. The NAD+-dependent breakdown of ethanol to acetaldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenases occurs mainly in the cytosol of hepatocytes. Subsequently, acetaldehyde diffuses into the mitochondrial matrix and is converted into acetate in another NAD+-dependent reaction catalysed by aldehyde dehydrogenases19. Alcohol consumption induces sustained elevation of plasma acetate levels (>0.5 mM) for at least 3 hours after an ethanol intake equivalent to 2.5 pints of beer with an alcohol-by-volume percentage of 5% by a 75 kg individual20,21 (FIG. 1; TABLE 1). Alcohol produces even higher levels of plasma acetate (>0.8 mM) in chronic drinkers than in controls, which is probably due to an enhanced ability of chronic drinkers to oxidize ethanol20. A causal link between increased cancer risk and alcohol consumption is widely accepted, and many of the effects of alcohol abuse are attributed to the carcinogenicity of acetaldehyde (reviewed in REF. 22). The effects of acetaldehyde are further compounded by the production of reactive oxygen species by cytochrome p450 2E1 (CYP2E1) during ethanol catabolism and the re-oxidation of the large amounts of NADH produced by the alcohol dehydrogenases and aldehyde dehydrogenases during ethanol oxidation22. Furthermore, increases in liver acetate levels may enhance hepatic inflammation by promoting histone acetylation at specific residues associated with pro-inflammatory gene transcription and cytokine synthesis23. Unfortunately, most studies on alcoholism and cancer fail to examine the effects of ethanol-derived acetate on tumour formation and growth. A large increase in circulating acetate levels may benefit some types of cancer (for example, breast, ovarian and lung cancer)24,25 that have increased expression of acetate-metabolizing enzymes such as acetyl-CoA synthetases.

Acetate transport.

The transporters involved in the uptake of acetate are still debated and, at least in cancer cells, remain largely unexplored. The plasma membrane is impermeable to acetate anions (CH3COO−) but is permeable to the non-ionic form called acetic acid (CH3COOH). However, given that acetic acid is a relatively weak acid (pKa = 4.75) and that the pH in the large intestine is between 5.5 and 7, only a small fraction of total acetate uptake into colonocytes occurs via passive diffusion, and this implies that the majority of the colonic acetate pool must be actively transported26 (FIG. 2). There is now also ample evidence for active uptake of acetate and other SCFAs by plasma membrane transporters, and three main mechanisms have been described thus far.

The first mechanism couples the import of SCFAs to the export of bicarbonate (HCO3−) (FIG. 2). Despite monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) being implicated as HCO3−–acetate antiporters, the identity of the transporter remains elusive26, and biochemical studies suggest that the function of HCO3− export is to aid in buffering the pH of the colonic lumen27,28.

The second mechanism for acetate uptake is mediated by sodium-coupled MCTs (SMCTs; part of the SLC family) (FIG. 2). Functional characterization of SMCT1 (also known as SLC5A8) demonstrated a Na+-dependent acetate transfer29,30. However, it is important to note that the uptake rate of butyrate by SMCT1 is nearly twofold higher than that of acetate29. In fact, many of the anti-cancer effects associated with high-fibre diets are directly attributable to the properties of butyrate, such as the inhibition of histone deacetylation that promotes differentiation and apoptosis13. Thus, one could envision that preventing substantial uptake of butyrate would be beneficial to a cancer cell. In line with this, it was found that SMCT1 is frequently silenced in colorectal cancer owing to promoter methylation31 and that its expression in cell lines that previously lacked expression inhibited colony formation31. Thus, it seems that SCFA transporter activity, when coupled to butyrate uptake, may help to prevent the development of cancer, but this protective effect may be specific to colonocytes because of their unique exposure to the high concentrations of butyrate produced in the gut. Indeed, it was shown that SMCT1 expression was significantly higher in prostate cancer than in matched non-neoplastic prostate tissue, suggesting that SMCT1 may have alternative cancer-promoting properties outside the colon, where butyrate concentrations are extremely low relative to acetate concentrations32. In this situation, it is tempting to speculate that SMCT1-mediated uptake of acetate by prostate cancer cells might support tumour growth or initiation.

The third mechanism involves the co-transport of a SCFA and H+. This uptake is mediated by a different class of the MCTs and is most likely to be dictated by MCT1 (also known as SLC16A1) and hypoxia-induced MCT4 (also known as SLC16A3), which are the predominant family members expressed in the colon and many types of cancers33–36 (FIG. 2). The Km values of the MCTs for acetate follow the order of MCT1 < MCT2 (also known as SLC16A7) < MCT4 (REFS 37,38). MCT inhibitors are currently being tested in clinical trials against advanced cancers39, and their upregulation in many cancer types is causally linked to adoption of aerobic glycolysis and the necessity to export the lactate produced by this process40. However, it would also be interesting to examine how intratumoural lactate concentrations or pharmacological targeting of MCTs affects acetate metabolism in vivo.

Overall, it seems that butyrate and acetate have distinct roles in relation to tumour growth and that this may in part depend on the expression of plasma membrane transporters, individual substrate affinities and competition between the SCFAs.

Metabolic fate of acetate

Acetyl-CoA synthetases.

After cellular uptake, there are only two enzymes that have proved to be capable of using acetate as a substrate: mitochondria-localized acetyl-CoA synthetase 1 (ACSS1)41 and nucleocytosol-localized ACSS2 (REF. 42). A third family member, ACSS3, has been proposed based on sequence homology to ACSS1 and ACSS2 (REF. 43). However, the classification of ACSS3 as an acetyl-CoA synthetase remains speculative, as there have been no reports on its enzymatic function and RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated silencing of ACSS3 in HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells had little to no effect on acetate-dependent labelling of lipids or histones25. However, ACSS3 is predicted to be mitochondrial and may be more relevant to the production of tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates. Future studies on its localization and tissue expression patterns may help to shed light on its physiological function.

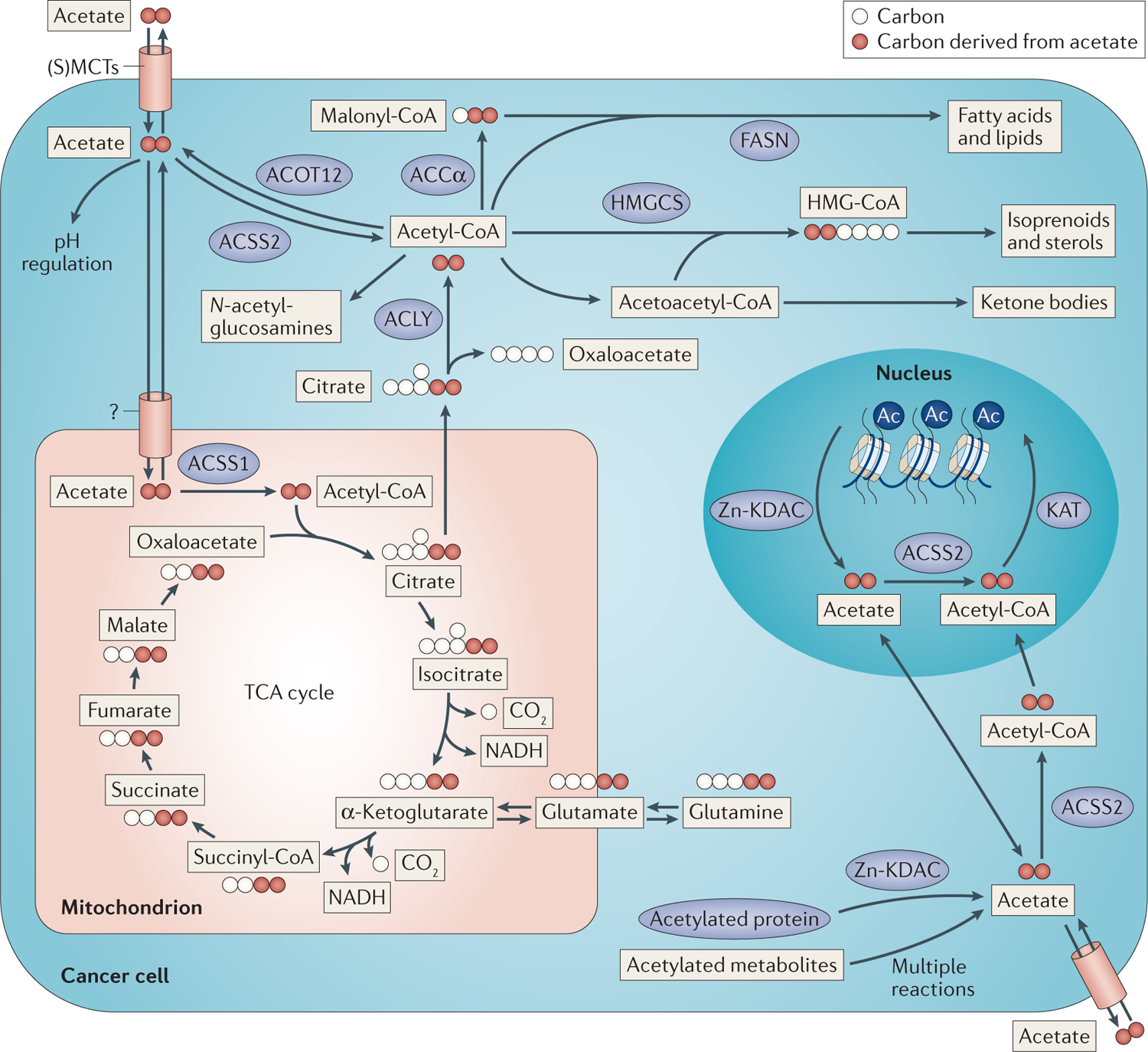

Acetyl-CoA synthetases by definition catalyse the ATP-dependent ligation of acetate and CoA to produce acetyl-CoA, which is a central metabolite at the nexus between glycolysis and the TCA cycle but also an important substrate for multiple other biochemical reactions and pathways such as the synthesis of sterols, hexosamines and ketones (FIG. 3). Data suggest that the rate-limiting step in acetate metabolism is the conversion of acetate to acetyl-CoA by acetyl-CoA synthetases42,44. To date, investigation of acetate metabolism in cancer has focused on three metabolic pathways: fatty acid biosynthesis, the TCA cycle and histone acetylation.

Figure 3 |. Intracellular acetate metabolism and the flow of acetate carbons.

Acetate is taken up by the cell through the mechanisms described in FIG. 2. Intracellular acetate is quickly converted into acetyl-CoA by acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 (ACSS2; nucleocytosolic) or ACSS1 (mitochondrial). Cytosolic acetyl-CoA can be used in various biosynthetic pathways, including those that produce fatty acids, isoprenoids and sterols, ketones and N-acetyl-glucosamines (top). Alternatively, acetyl-CoA can be used by lysine acetyltransferases (KATs) to acetylate metabolites and proteins, including histones (bottom right). Conversely, histones, as well as other proteins, and metabolites can be deacetylated by specific lysine deacetylases (KDACs), such as Zn2+-containing KDACs (Zn-KDACs), or metabolite deacetylases to regenerate acetate. Mitochondrial acetyl-CoA enters the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and condenses with oxaloacetate to form citrate (bottom left). Citrate can be further oxidized through the TCA cycle, generating reducing equivalents for ATP production, or citrate can be exported to the cytosol and cleaved back into acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate. Ac, acetylation; ACCα, acetyl-CoA carboxylase-α; ACLY, ATP citrate lyase; ACOT12, acyl-CoA thioesterase 12; FASN, fatty acid synthase; HMG-CoA, hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA; HMGCS, hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase; (S)MCT, (sodium-coupled) monocarboxylate transporter.

Acetate contribution to fatty acid synthesis.

The incorporation of acetate into fatty acids involves three enzymatic steps: ligation of acetate with CoA to produce acetyl-CoA by ACSS2, carboxylation of acetyl-CoA by acetyl-CoA carboxylase-α (ACCα; also known as ACC1 and encoded by ACACA), and the condensation of acetyl-CoA and/or malonyl-CoA by fatty acid synthase (FASN) (FIG. 3). This enzymatic cascade occurs in the cytosol and, as such, relies on cytosolic acetyl-CoA as the substrate. A second intracellular pool of acetyl-CoA is contained within mitochondria and cannot contribute to lipogenesis without first being converted into citrate. Unlike acetyl-CoA, citrate can be transported to the cytosol and cleaved by ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) to regenerate oxaloacetate and acetyl-CoA (FIG. 3). Depletion of ACLY inhibits the growth of tumour xenografts originating from highly glycolytic cancer cell lines but not of those from cells with low rates of glycolysis, suggesting that there are alternative pathways for acetyl-CoA production in some cell types45. It was subsequently shown that ACSS2 is upregulated after ACLY depletion and is critical for the survival of cancer cells lacking ACLY46.

Under nutrient-replete conditions, ACLY is predicted to generate the bulk of the cytosolic acetyl-CoA pool in most tissues, including tumours45,47,48. However, metabolic stresses, such as fasting or hypoxia, induce phosphorylation of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) by pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases (PDKs) and inhibit the oxidation of pyruvate in the TCA cycle49,50. This directly impairs the production of citrate (the substrate for ACLY)49, so to maintain nucleocytosolic acetyl-CoA levels alternative sources must be engaged. Indeed, analysis of the fatty acid pools in cancer cells under metabolic stress revealed a lipogenic substrate gap that could not be accounted for by carbon contributions from either glucose or glutamine24,51. It was shown that physiologically relevant concentrations of acetate are able to provide as much as half of the necessary substrate to support fatty acid synthesis under hypoxic conditions24,51, whereas the remaining lipogenic acetyl-CoA is most likely derived from a combination of sources, including glucose, glutamine, ketone bodies and branched chain amino acids.

Lipogenic substrate gap.

Alternative carbon sources that contribute to de novo fatty acid synthesis, as a large proportion (20–40%) of carbons in fatty acids in hypoxic cancer cells cannot be attributed to glucose or glutamine.

ACSS2 was identified in an unbiased functional genomic screen as a critical enzyme for the growth and survival of breast and prostate cancer cells cultured in hypoxia and low serum24. Acetate also becomes a major carbon source for fatty acid and phospholipid synthesis during metabolic stress, particularly in cancer cell lines harbouring DNA copy number gains at the ACSS2 locus24. Furthermore, depletion of ACSS2 in tumour xenografts inhibits growth, suggesting that the conversion of acetate to acetyl-CoA is crucial for sustaining tumour growth24,25. Similar results were obtained in two genetically engineered mouse models of HCC that showed a decreased tumour burden and an increased percentage of well-differentiated tumours in an Acss2−/− background compared with those in a wild-type background25. Indeed, high expression of ACSS2 is frequently found in invasive ductal carcinomas of the breast, triple-negative breast cancer, glioblastoma, ovarian cancer and lung cancer, and often directly correlates with higher-grade tumours and poorer survival compared with tumours that have low ACSS2 expression24,25,52. Similarly to ACSS2, FASN is also upregulated in breast cancer, and this upregulation correlates with markedly poorer prognosis compared with patients whose tumours have low levels of FASN expression53. In addition, both ACSS2 and FASN are transcriptionally co-regulated in a hypoxia-inducible factor 1β (HIF1β; also known as aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT))-dependent and sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 2 (SREBF2)-dependent manner under metabolically stressed conditions24, suggesting that upregulation of an acetate-dependent lipogenesis programme may be characteristic of more aggressive types of breast cancer.

Surprisingly, there have been no reported phenotypic differences in Acss2−/− versus wild-type mice25,54, and only a single study reports on the ability of Acss2−/− mice to handle stress54. In this latter study, the authors showed that acetate supplementation augments stress erythropoiesis in response to hypoxia or anaemia in a HIF2α (also known as EPAS1)- and ACSS2-dependent manner54. Their result suggests that, although ACSS2 is dispensable for normal development, certain pathophysiological situations may require metabolism of acetate by ACSS2. The lack of any distinguishable phenotype in the Acss2−/− mice also implies that compensatory pathways must exist for acetyl-CoA production or that acetate-derived acetyl-CoA is of only minor importance in healthy tissues. Despite the inability to directly generate cytosolic acetyl-CoA from acetate, ACSS2-deficient cells would still be able to capture acetate in the mitochondria through ACSS1 and this acetate-derived carbon would contribute to cytosolic acetyl-CoA pools through the activity of ACLY (FIG. 3). This may be sufficient for normal tissue homeostasis, but the data from mouse tumour models imply that ACSS1 compensatory pathways are insufficient to support tumorigenesis24,25. The interplay between ACSS1, ACSS2 and ACLY in the control of acetyl-CoA metabolism should be an exciting area for future research.

Acetate contribution to the TCA cycle.

Acetate oxidation in the TCA cycle provides reducing equivalents for energy production by oxidative phosphorylation (FIG. 3). The labelling of citrate from [13C]acetate confirmed that intra-mitochondrial acetyl-CoA can be generated from acetate in cancer cells24. However, the mechanism of acetate import into mitochondria remains unknown. ACSS1 has been proposed to be the mitochondrial equivalent of ACSS2 and catalyses intra-mitochondrial conversion of acetate to acetyl-CoA. Similar to the lipogenic substrate gap observed in breast and prostate cancer cell lines24,51, a recent report identified a bioenergetic substrate gap in which a large fraction of the acetyl-CoA pool had not been derived from glucose or glutamine55. Follow-up studies on glioblastomas and brain metastases from patients that had been infused with [13C]acetate during tumour resection indicated that acetate may provide this missing link52. Nearly one-half of the intra-mitochondrial acetyl-CoA pool in patient tumours was found to be derived from blood-borne acetate, as indicated by the production of 13C-labelled glutamate52. These data were further verified in patient-derived xenograft (PDX) brain tumour models in mice that had been co-infused with [13C]glucose and [13C]acetate to directly compare substrate utilization52. Strikingly, the PDX models displayed nearly identical labelling patterns to in situ human brain tumours, and perhaps even more astounding was the finding that multiple different brain metastases, regardless of the tissue of origin, exhibited very similar patterns as well. Unfortunately, the more relevant role of ACSS1 in supplying acetyl-CoA to the TCA cycle in these models was not explored. Rather, the authors showed that RNAi-mediated silencing of ACSS2 expression in primary glioblastoma cultures severely inhibited neurosphere growth52, suggesting that, in addition to being a mitochondrial bioenergetics substrate, acetate may be important for other metabolic pathways in glioblastoma (for example, lipogenesis or acetylation)52. A more recent report that compared gene expression profiles of HCC tissue with adjacent normal liver tissue found ACSS1 to be significantly upregulated and positively correlated with cell proliferation markers, suggesting that mitochondrial capture of acetate may be more important in some cancer types56. Altogether, these metabolic fates of acetate indicate that when mitochondrial glucose oxidation is compromised (under conditions of hypoxia or low glucose) or availability of exogenous lipids is limited owing to disorganized vascularization, acetate can be used to generate acetyl-CoA for energy production via the TCA cycle and/or to generate biomass.

Bioenergetic substrate gap.

Alternative sources of carbon that contribute to tumour bioenergetics, as less than 50% of acetyl-CoA in human brain tumours is derived from blood-borne glucose.

In addition, it seems that the ability to metabolize acetate can be induced by the microenvironment. In support of this hypothesis, when mouse primary astrocytes were cultured ex vivo, the expression of ACSS2 significantly decreased at early passages52. This suggests that acetate utilization is highly influenced and regulated by the specific conditions to which cells are exposed. A recent report has highlighted that cancer cell metabolism can undergo profound changes in tissue culture57,58. However, the potential of other indirect causes of ACSS2 downregulation created by culturing cells for multiple passages in vitro cannot be excluded. Future studies are needed to elucidate why acetate metabolism may be favoured under in vivo over in vitro culture conditions.

Acetate contribution to histone acetylation.

The versatility of acetate-derived acetyl-CoA extends beyond being a bioenergetic substrate and a lipogenic precursor to include acetylation of proteins and metabolites. Lysine acetyltransferases (KATs) catalyse the transfer of the acetyl group from acetyl-CoA to the terminal amine on lysine side chains. Conversely, lysine deacetylases (KDACs) that contain Zn2+ (herein referred to as Zn-KDACs) catalyse the hydrolysis of the amide linkage to release free acetate. Acetate released by such KDACs can be either exported59 or potentially recaptured by acetyl-CoA synthetases (FIG. 3).

The role of acetyl-CoA synthetases in the regulation of histone acetylation was first identified in yeast; loss of acetyl-CoA synthetase expression drastically reduced histone acetylation and caused global transcriptional repression owing to a reduction in the nucleocytosolic acetyl-CoA pool60. Ablation of Acss2 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts or RNAi-mediated silencing of ACSS2 in cancer cell lines also markedly inhibits acetylation of histones by acetate25. Conversely, supplementation of acetate alone increases histone acetylation in a dose-dependent manner and rescues histone deacetylation caused by ACLY inhibition in an ACSS2-dependent manner47. More recently, it was shown that acetate supplementation to cancer cell lines cultured in hypoxia predominately activated the expression of lipogenic genes (that is, ACACA and FASN) by acetylation of specific lysine residues on histone H3 and that expression of ACSS1 and ACSS2 in tissues derived from patients with HCC positively correlated with histone acetylation and FASN expression61. Adding a further layer of complexity, a recent report identified that histone crotonylation is partly controlled by the expression of ACSS2, suggesting that the substrate specificity of ACSS2 may not be solely limited to acetate56. Interestingly, some recent studies suggest that the activation of HIF2 by acetylation during metabolic stress is dependent on the generation of nuclear acetyl-CoA by ACSS2 (REFS 54,62).

Crotonylation.

A post-translational modification of histone lysine residues that has been shown to stimulate transcription and is, at least partially, dependent on acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 (ACSS2)-catalysed production of crotonyl-CoA from the short-chain fatty acid crotonate.

Furthermore, the differences in the Km of the various KATs (for example, GCN5 (also known as KAT2A), P/CAF (also known as KAT2B) and p300 (also known as EP300)) for acetyl-CoA predict that fluctuations within the physiological range of acetyl-CoA concentrations could selectively affect their individual activities63,64. However, the extent to which acetate availability can influence specific epigenetic marks, global acetylation levels or the activity of KATs remains to be determined. Nevertheless, acetate may become a substantial source for cellular acetyl-CoA when other carbon sources (for example, glucose and glutamine) are limited, and acetate utilization will depend on its availability, efficiency of uptake and the expression of acetate-capturing enzymes (for example, ACSS1 and ACSS2).

Acetate (re)capture

As discussed above, some types of cancer (particularly colorectal cancer) may be exposed to high, locally produced, concentrations of acetate. Although it is tempting to speculate on a potential bioenergetic or lipogenic role of acetate in such tumours, no supporting published data are available to date. Also, it is still unclear to what extent colorectal cancer cells utilize luminal or mucosal metabolites compared with nutrients that are delivered by the vasculature. As the concentration of acetate in human plasma is in the range of ~50–200 μM (TABLE 1), it begs the questions: to what extent can acetate support biomass or energy production in peripheral tumours, and what effect does its capture have on tumour growth? The answer most likely involves a combination of two processes: the capture, or recapture, of free acetate generated intracellularly and enhanced acetate uptake from the extracellular milieu.

Zn-KDACs have been shown to be overexpressed in various cancers65, and with an estimated 1 × 109 potential histone acetylation sites per mammalian cell66, acetylated residues on histones collectively represent a substantial carbon source in cancer cells that could be quickly mobilized. However, if large-scale histone deacetylation proceeded in the absence of a mechanism to salvage the acetate (for example, low ACSS2 expression), then cells would be unable to exploit this nutritional source and the accumulation of intracellular free acetate would become toxic (causing acidosis) if not excreted. Indeed, it has been noted that acetate is excreted from some cancer cells cultured in low glucose62,67. The release of acetate anions during histone deacetylation has been shown to be involved in the regulation of intracellular pH by providing a buffering capacity for cancer cells in response to pH changes in the often acidic tumour environment59. In this scenario, the liberated acetate facilitates the export of protons through the MCTs to alleviate acidosis. In cancer cells with high expression of acetyl-CoA synthetases, the acetate generated by histone deacetylation may provide short-term relief during metabolic stress. This respite may be sufficiently long to support growth and survival under metabolic stress and to allow other means of acetyl-CoA biosynthesis to become activated (for example, glucose oxidation, fatty acid oxidation and/or branched chain amino acid degradation).

Altogether, the ability to capture and recycle free acetate would be advantageous to a cell, particularly a cancer cell that is under selective pressure to increase its growth rate, and hence would favour metabolic flux distributions that produce essential biomass precursors at high rates. The observed upregulation of ACSS2 during hypoxia would aid in capturing acetate from the tumour microenvironment when other nutrients are scarce or perhaps in recapturing intracellularly generated free acetate to prevent its loss. One could surmise that if most normal tissues and well-vascularized regions of tumours are amply supplied with other nutritional sources and are additionally inept at capturing acetate (for example, owing to low ACSS2 expression), then unadulterated acetate may be able to penetrate into poorly vascularized regions of tumours, which is similar to what has been described for lactate68.

Some sirtuin (SIRT) family members are NAD+-dependent KDACs (NAD+-SIRTs), and their expression is controlled by many nutrient-sensing transcription factors (for example, forkhead box O (FOXO) proteins, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein (CHREBP))69. However, unlike Zn-KDACs, NAD+-SIRTs do not release free acetate but rather produce acetyl-ADP-ribose. During instances of fasting or caloric restriction, these SIRTs become activated owing to an increased NAD+:NADH ratio70. Interestingly, ACSS1 and ACSS2 are reversibly acetylated at a highly conserved lysine residue within their active site and their deacetylation by SIRT3 and SIRT1, respectively, induces acetyl-CoA synthetase activity71–73. Thus, a major metabolic response to accumulation of NAD+ and bioenergetic stress is the activation of acetyl-CoA synthetases and acetate metabolism.

Caloric restriction.

Caloric restriction without malnutrition is a dietary strategy that has been studied extensively as a way to slow ageing and extend lifespan.

Acetate as a signalling molecule

The physiological function of acetate extends beyond being a nutritional source. Acetate also acts as a ligand for a small family of broadly expressed G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) called free fatty acid receptors (FFARs)74. Two FFARs (FFAR2 and FFAR3) have been shown to be activated by SCFAs, whereas FFAR1 binds long-chain fatty acids74. FFAR2 was more sensitive to acetate than FFAR3 and activates GPCR signalling via the G proteins Gαq/11 and Gαi/o to induce intracellular Ca2+ release74. FFAR2 signalling has been implicated in diabetes and insulin secretion75,76, the stimulation of adipogenesis77,78 and the regulation of many different immune cells79–82. However, the role of FFARs in cancer has been explored in only a handful of studies, some of which have reported conflicting results. A screen to identify transforming genes from a surgically resected gall bladder cancer suggested that FFAR2 may be oncogenic83. The authors showed that FFAR2 over-expression in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts induced transformation and enhanced viral RAS (v-RAS)-induced tumour growth in immunocompromised mice83. However, a separate report showed that FFAR2 signalling inhibited colorectal cancer proliferation and promoted cell death, suggesting a tumour-suppressive role84. Last, FFAR2 activation can also help to manage cellular stress through p38 MAPK activation in MCF7 breast cancer cells85. Overall, given the low circulating levels of acetate, the cell signalling function of acetate may yet prove to be a more critical determinant for cancer growth and progression than its nutritional value to the tumour and will most likely be influenced by the tissue of origin and FFAR expression.

Acetate biotracers in PET imaging

[18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG) is the most prolific biotracer used in clinical positron emission tomography (PET) imaging today. The uptake of [18F]FDG fundamentally provides a readout of metabolic activity and has proved to be an excellent probe for identifying highly proliferative tumours that possess a high rate of glucose uptake86,87. However, many tumours do not have high rates of glucose consumption, and others have limited access to glucose owing to aberrant vasculature88. In addition, some tumours reside in healthy tissues that naturally consume high amounts of glucose (for example, brain tissue), which prevents resolution of cancer tissue from normal tissue89,90. Therefore, it is paramount that novel cancer-specific biotracers be developed to address this unmet need in cancer detection.

[11C]acetate has shown excellent potential in providing such an alternative (reviewed in REF. 91), and thus far it has been predominantly used in prostate cancer92–98 but has also been successfully applied in patients with renal cell cancer99, HCC25,100, lung cancer101, glioma89,102 or multiple myeloma103. Indeed, emerging data suggest that [11C]acetate outperforms [18F]FDG in detection and staging of gliomas and multiple myelomas89,103 and in visualization of bone metastases in patients with advanced prostate cancer104. A recent report highlighting substantial intratumoural metabolic heterogeneity in patients with lung cancer105 suggests that the use of [18F]FDG and [11C]acetate together as a dual modality might offer a more effective diagnostic tool58. The application of [11C]acetate extends beyond the clinic and can be used as a valuable in vivo metabolism research tool. For instance, it was recently shown that late PET imaging with [11C]acetate produces better contrast and, as the tracer accumulates in the lipid fraction, can offer information about acetate-dependent lipogenesis101.

Future research directions

It has now become apparent that acetate metabolism plays a major part in many different types of cancer. Some tumours mainly use it for energy production, others for lipid production and still others as a means to regulate histone acetylation and, by extension, gene transcription. However, these individual metabolic fates of acetate need not be mutually exclusive. Exploring why tissues handle acetate in such diverse manners will aid in understanding how it is capable of supporting tumour growth, and elucidating the factors that control acetate capture, metabolism and recycling can reveal new drug targets for cancer therapy.

The expression of ACSS2 is emerging as one of the key factors in the regulation of acetate metabolism. ACSS2 expression endows cancer cells with the ability to maximally utilize acetate as a nutritional source. It is this kind of metabolic plasticity — the ability to exploit and survive on a variety of nutritional sources — that confers resistance to many of the current cancer metabolism drugs as monotherapies. Interestingly, ACSS2 is highly expressed in many cancer tissues, and its upregulation by hypoxia and low nutrient availability indicates that it is an important enzyme for coping with the typical stresses within the tumour microenvironment and, as such, a potential Achilles heel. Moreover, highly stressed regions of tumours have been shown to select for apoptotic resistance and promote aggressive behaviour, treatment resistance and relapse. In this way, the combination of ACSS2 inhibitors with a therapy that specifically targets well-oxygenated regions of tumours (for example, radiotherapy) could prove to be an effective regimen.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare competing interests: see Web version for details.

References

- 1.Medes G, Friedmann B & Weinhouse S Fatty acid metabolism. VIII. Acetate metabolism in vitro during hepatocarcinogenesis by p-dimethylaminoazobenzene. Cancer Res. 16, 57–62 (1956). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medes G & Weinhouse S Metabolism of neoplastic tissue. XIII. Substrate competition in fatty acid oxidation in ascites tumor cells. Cancer Res. 18, 352–359 (1958). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medes G, Paden G & Weinhouse S Metabolism of neoplastic tissues. XI. Absorption and oxidation of dietary fatty acids by implanted tumors. Cancer Res. 17, 127–133 (1957). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomlinson RH & Gray LH The histological structure of some human lung cancers and the possible implications for radiotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 9, 539–549 (1955). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nath A & Chan C Genetic alterations in fatty acid transport and metabolism genes are associated with metastatic progression and poor prognosis of human cancers. Sci. Rep 6, 18669 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaugg K et al. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1C promotes cell survival and tumor growth under conditions of metabolic stress. Genes Dev. 25, 1041–1051 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gajewski TF, Schreiber H & Fu YX Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Immunol 14, 1014–1022 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azzi S, Hebda JK & Gavard J Vascular permeability and drug delivery in cancers. Front. Oncol 3, 211 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joint FAO/WHO Codex Alimentarius Commission. Codex general standard for food additives http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/download/standards/4/CXS_192_2015e.pdf (Joint FAO/WHO Codex Alimentarius Commission, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suematsu N & Isohashi F Molecular cloning and functional expression of human cytosolic acetyl-CoA hydrolase. Acta Biochim. Pol 53, 553–561 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horibata Y, Ando H, Itoh M & Sugimoto H Enzymatic and transcriptional regulation of the cytoplasmic acetyl-CoA hydrolase ACOT12. J. Lipid Res 54, 2049–2059 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheppach W, Pomare EW, Elia M & Cummings JH The contribution of the large intestine to blood acetate in man. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 80, 177–182 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louis P, Hold GL & Flint HJ The gut microbiota, bacterial metabolites and colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 12, 661–672 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cummings JH, Pomare EW, Branch WJ, Naylor CP & Macfarlane GT Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut 28, 1221–1227 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuchmann K & Muller V Autotrophy at the thermodynamic limit of life: a model for energy conservation in acetogenic bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 12, 809–821 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rey FE et al. Dissecting the in vivo metabolic potential of two human gut acetogens. J. Biol. Chem 285, 22082–22090 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donohoe DR et al. The microbiome and butyrate regulate energy metabolism and autophagy in the mammalian colon. Cell Metab. 13, 517–526 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bloemen JG et al. Short chain fatty acids exchange across the gut and liver in humans measured at surgery. Clin. Nutr 28, 657–661 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rocco A, Compare D, Angrisani D, Sanduzzi Zamparelli M & Nardone G Alcoholic disease: liver and beyond. World J. Gastroenterol 20, 14652–14659 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nuutinen H, Lindros K, Hekali P & Salaspuro M Elevated blood acetate as indicator of fast ethanol elimination in chronic alcoholics. Alcohol 2, 623–626 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundquist F, Tygstrup N, Winkler K, Mellemgaard K & Munck-Petersen S Ethanol metabolism and production of free acetate in the human liver. J. Clin. Invest 41, 955–961 (1962). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seitz HK & Stickel F Molecular mechanisms of alcohol-mediated carcinogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 599–612 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kendrick SF et al. Acetate, the key modulator of inflammatory responses in acute alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 51, 1988–1997 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schug ZT et al. Acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 promotes acetate utilization and maintains cancer cell growth under metabolic stress. Cancer Cell 27, 57–71 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study identified ACSS2 as a key enzyme for cancer cell growth under ‘tumour-like’ conditions of low lipid availability and hypoxia. It also showed that ACSS2 was highly upregulated under these same conditions and that depletion of ACSS2 inhibited tumour growth.

- 25.Comerford SA et al. Acetate dependence of tumors. Cell 159, 1591–1602 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This was the first paper to study Acss2−/− mice in two different mouse models of liver cancer and showed that loss of ACSS2 decreased tumour burden.

- 26.Fleming SE, Choi SY & Fitch MD Absorption of short-chain fatty acids from the rat cecum in vivo. J. Nutr 121, 1787–1797 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reynolds DA, Rajendran VM & Binder HJ Bicarbonate-stimulated [14C]butyrate uptake in basolateral membrane vesicles of rat distal colon. Gastroenterology 105, 725–732 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu S & Montrose MH Extracellular pH regulation in microdomains of colonic crypts: effects of short-chain fatty acids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 3303–3307 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyauchi S, Gopal E, Fei YJ & Ganapathy V Functional identification of SLC5A8, a tumor suppressor down-regulated in colon cancer, as a Na+-coupled transporter for short-chain fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem 279, 13293–13296 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coady MJ et al. The human tumour suppressor gene SLC5A8 expresses a Na+-monocarboxylate cotransporter. J. Physiol 557, 719–731 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H et al. SLC5A8, a sodium transporter, is a tumor suppressor gene silenced by methylation in human colon aberrant crypt foci and cancers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 8412–8417 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin HY et al. Protein expressions and genetic variations of SLC5A8 in prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness. Urology 78, 971.e1–971.e9 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ullah MS, Davies AJ & Halestrap AP The plasma membrane lactate transporter MCT4, but not MCT1, is upregulated by hypoxia through a HIF-1α-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem 281, 9030–9037 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parks SK, Chiche J & Pouyssegur J Disrupting proton dynamics and energy metabolism for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 611–623 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirat D & Kato S Monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) mediates transport of short-chain fatty acids in bovine caecum. Exp. Physiol 91, 835–844 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinheiro C et al. Increased expression of monocarboxylate transporters 1, 2, and 4 in colorectal carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 452, 139–146 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moschen I, Broer A, Galic S, Lang F & Broer S Significance of short chain fatty acid transport by members of the monocarboxylate transporter family (MCT). Neurochem. Res 37, 2562–2568 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackson VN & Halestrap AP The kinetics, substrate, and inhibitor specificity of the monocarboxylate (lactate) transporter of rat liver cells determined using the fluorescent intracellular pH indicator, 2′,7′-bis(carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein. J. Biol. Chem 271, 861–868 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olivares O, Dabritz JH, King A, Gottlieb E & Halsey C Research into cancer metabolomics: towards a clinical metamorphosis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 43, 52–64 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bola BM et al. Inhibition of monocarboxylate transporter-1 (MCT1) by AZD3965 enhances radiosensitivity by reducing lactate transport. Mol. Cancer Ther 13, 2805–2816 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fujino T, Kondo J, Ishikawa M, Morikawa K & Yamamoto TT Acetyl-CoA synthetase 2, a mitochondrial matrix enzyme involved in the oxidation of acetate. J. Biol. Chem 276, 11420–11426 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luong A, Hannah VC, Brown MS & Goldstein JL Molecular characterization of human acetyl-CoA synthetase, an enzyme regulated by sterol regulatory element-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem 275, 26458–26466 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a seminal paper describing the molecular characterization of transcriptional regulation of ACSS2.

- 43.Watkins PA, Maiguel D, Jia Z & Pevsner J Evidence for 26 distinct acyl-coenzyme A synthetase genes in the human genome. J. Lipid Res 48, 2736–2750 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tucek S Subcellular distribution of acetyl-CoA synthetase, ATP citrate lyase, citrate synthase, choline acetyltransferase, fumarate hydratase and lactate dehydrogenase in mammalian brain tissue. J. Neurochem 14, 531–545 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hatzivassiliou G et al. ATP citrate lyase inhibition can suppress tumor cell growth. Cancer Cell 8, 311–321 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zaidi N, Royaux I, Swinnen JV & Smans K ATP citrate lyase knockdown induces growth arrest and apoptosis through different cell- and environment-dependent mechanisms. Mol. Cancer Ther 11, 1925–1935 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wellen KE et al. ATP-citrate lyase links cellular metabolism to histone acetylation. Science 324, 1076–1080 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bauer DE, Hatzivassiliou G, Zhao F, Andreadis C & Thompson CB ATP citrate lyase is an important component of cell growth and transformation. Oncogene 24, 6314–6322 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim JW, Tchernyshyov I, Semenza GL & Dang CV HIF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab. 3, 177–185 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spriet LL et al. Pyruvate dehydrogenase activation and kinase expression in human skeletal muscle during fasting. J. Appl. Physiol 96, 2082–2087 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kamphorst JJ, Chung MK, Fan J & Rabinowitz JD Quantitative analysis of acetyl-CoA production in hypoxic cancer cells reveals substantial contribution from acetate. Cancer Metab. 2, 23 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper provides the first description of the lipogenic substrate gap that occurs particularly under hypoxic conditions. It identified acetate as the additional source of lipogenic acetyl-CoA.

- 52.Mashimo T et al. Acetate is a bioenergetic substrate for human glioblastoma and brain metastases. Cell 159, 1603–1614 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a landmark paper describing the tissue-specific enhancement of acetate oxidation by glioblastomas and brain metastases (regardless of their tissue of origin).

- 53.Kuhajda FP et al. Fatty acid synthesis: a potential selective target for antineoplastic therapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 6379–6383 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu M et al. An acetate switch regulates stress erythropoiesis. Nat. Med 20, 1018–1026 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maher EA et al. Metabolism of [U-13 C]glucose in human brain tumors in vivo. NMR Biomed. 25, 1234–1244 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This was the original paper describing how the infusion of patients with stable isotope tracers revealed the bioenergetic substrate gap in brain tumours.

- 56.Bjornson E et al. Stratification of hepatocellular carcinoma patients based on acetate utilization. Cell Rep. 13, 2014–2026 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schug ZT, Vande Voorde J & Gottlieb E The nurture of tumors can drive their metabolic phenotype. Cell Metab. 23, 391–392 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davidson SM et al. Environment impacts the metabolic dependencies of Ras-driven non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Metab. 23, 517–528 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McBrian MA et al. Histone acetylation regulates intracellular pH. Mol. Cell 49, 310–321 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takahashi H, McCaffery JM, Irizarry RA & Boeke JD Nucleocytosolic acetyl-coenzyme a synthetase is required for histone acetylation and global transcription. Mol. Cell 23, 207–217 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The role of acetyl-CoA synthetases in the regulation of histone acetylation was first identified in yeast.

- 61.Gao X et al. Acetate functions as an epigenetic metabolite to promote lipid synthesis under hypoxia. Nat. Commun 7, 11960 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen R et al. The acetate/ACSS2 switch regulates HIF-2 stress signaling in the tumor cell microenvironment. PLoS ONE 10, e0116515 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fan J, Krautkramer KA, Feldman JL & Denu JM Metabolic regulation of histone post-translational modifications. ACS Chem. Biol 10, 95–108 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee JV et al. Akt-dependent metabolic reprogramming regulates tumor cell histone acetylation. Cell Metab. 20, 306–319 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rajendran P, Williams DE, Ho E & Dashwood RH Metabolism as a key to histone deacetylase inhibition. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol 46, 181–199 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martinez-Pastor B, Cosentino C & Mostoslavsky R A tale of metabolites: the cross-talk between chromatin and energy metabolism. Cancer Discov. 3, 497–501 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yoshii Y et al. Cytosolic acetyl-CoA synthetase affected tumor cell survival under hypoxia: the possible function in tumor acetyl-CoA/acetate metabolism. Cancer Sci. 100, 821–827 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sonveaux P et al. Targeting lactate-fueled respiration selectively kills hypoxic tumor cells in mice. J. Clin. Invest 118, 3930–3942 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E & Auwerx J Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 13, 225–238 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen R, Dioum EM, Hogg RT, Gerard RD & Garcia JA Hypoxia increases sirtuin 1 expression in a hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem 286, 13869–13878 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Starai VJ, Celic I, Cole RN, Boeke JD & Escalante-Semerena JC Sir2-dependent activation of acetyl-CoA synthetase by deacetylation of active lysine. Science 298, 2390–2392 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schwer B, Bunkenborg J, Verdin RO, Andersen JS & Verdin E Reversible lysine acetylation controls the activity of the mitochondrial enzyme acetyl-CoA synthetase 2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 10224–10229 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hallows WC, Lee S & Denu JM Sirtuins deacetylate and activate mammalian acetyl-CoA synthetases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 10230–10235 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; References 72 and 73 were the first reports of the regulation of ACSS1 and ACSS2 by reversible acetylation, in part controlled by SIRTs.

- 74.Brown AJ et al. The orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J. Biol. Chem 278, 11312–11319 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a seminal paper that initially identified and characterized the acetate receptors.

- 75.Priyadarshini M et al. An acetate-specific GPCR, FFAR2, regulates insulin secretion. Mol. Endocrinol 29, 1055–1066 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tang C et al. Loss of FFA2 and FFA3 increases insulin secretion and improves glucose tolerance in type 2 diabetes. Nat. Med 21, 173–177 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ge H et al. Activation of G protein-coupled receptor 43 in adipocytes leads to inhibition of lipolysis and suppression of plasma free fatty acids. Endocrinology 149, 4519–4526 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hong YH et al. Acetate and propionate short chain fatty acids stimulate adipogenesis via GPCR43. Endocrinology 146, 5092–5099 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Peck B et al. Inhibition of fatty acid desaturation is detrimental to cancer cell survival in metabolically compromised environments. Cancer Metab. 4, 6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smith PM et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science 341, 569–573 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Erny D et al. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat. Neurosci 18, 965–977 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Correa-Oliveira R, Fachi JL, Vieira A, Sato FT & Vinolo MA Regulation of immune cell function by short-chain fatty acids. Clin. Transl Immunol 5, e73 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hatanaka H et al. Identification of transforming activity of free fatty acid receptor 2 by retroviral expression screening. Cancer Sci. 101, 54–59 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tang Y, Chen Y, Jiang H, Robbins GT & Nie D G-Protein-coupled receptor for short-chain fatty acids suppresses colon cancer. Int. J. Cancer 128, 847–856 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yonezawa T, Kobayashi Y & Obara Y Short-chain fatty acids induce acute phosphorylation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase/heat shock protein 27 pathway via GPR43 in the MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line. Cell. Signal 19, 185–193 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shou Y, Lu J, Chen T, Ma D & Tong L Correlation of fluorodeoxyglucose uptake and tumor-proliferating antigen Ki-67 in lymphomas. J. Cancer Res. Ther 8, 96–102 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Riedl CC et al. 18F-FDG PET scanning correlates with tissue markers of poor prognosis and predicts mortality for patients after liver resection for colorectal metastases. J. Nucl. Med 48, 771–775 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gillies RJ, Schornack PA, Secomb TW & Raghunand N Causes and effects of heterogeneous perfusion in tumors. Neoplasia 1, 197–207 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yamamoto Y et al. 11C-acetate PET in the evaluation of brain glioma: comparison with 11C-methionine and 18F-FDG-PET. Mol. Imaging Biol 10, 281–287 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wong TZ, van der Westhuizen GJ & Coleman RE Positron emission tomography imaging of brain tumors. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am 12, 615–626 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yoshii Y, Furukawa T, Saga T & Fujibayashi Y Acetate/acetyl-CoA metabolism associated with cancer fatty acid synthesis: overview and application. Cancer Lett. 356, 211–216 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vavere AL, Kridel SJ, Wheeler FB & Lewis JS 1-11C-acetate as a PET radiopharmaceutical for imaging fatty acid synthase expression in prostate cancer. J. Nucl. Med 49, 327–334 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Oyama N et al. 11C-acetate PET imaging of prostate cancer. J. Nucl. Med 43, 181–186 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ponde DE et al. 18F-fluoroacetate: a potential acetate analog for prostate tumor imaging—in vivo evaluation of 18F-fluoroacetate versus 11C-acetate. J. Nucl. Med 48, 420–428 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jadvar H Prostate cancer: PET with 18F-FDG, 18F- or 11C-acetate, and 18F- or 11C-choline. J. Nucl. Med 52, 81–89 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brogsitter C, Zophel K & Kotzerke J 18F-Choline, 11C-choline and 11C-acetate PET/CT: comparative analysis for imaging prostate cancer patients. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 40 (Suppl. 1), S18–S27 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schiepers C et al. 1-11C-acetate kinetics of prostate cancer. J. Nucl. Med 49, 206–215 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mena E et al. 11C-Acetate PET/CT in localized prostate cancer: a study with MRI and histopathologic correlation. J. Nucl. Med 53, 538–545 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Oyama N et al. 11C-Acetate PET imaging for renal cell carcinoma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 36, 422–427 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Park JW et al. A prospective evaluation of 18F-FDG and 11C-acetate PET/CT for detection of primary and metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Nucl. Med 49, 1912–1921 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lewis DY et al. Late imaging with [1-11C]acetate improves detection of tumor fatty acid synthesis with PET. J. Nucl. Med 55, 1144–1149 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tsuchida T, Takeuchi H, Okazawa H, Tsujikawa T & Fujibayashi Y Grading of brain glioma with 1-11C-acetate PET: comparison with 18F-FDG PET. Nucl. Med. Biol 35, 171–176 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ho CL et al. 11C-acetate PET/CT for metabolic characterization of multiple myeloma: a comparative study with 18F-FDG PET/CT. J. Nucl. Med 55, 749–752 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Seltzer MA et al. Radiation dose estimates in humans for 11C-acetate whole-body PET. J. Nucl. Med 45, 1233–1236 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hensley CT et al. Metabolic heterogeneity in human lung tumors. Cell 164, 681–694 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Peters SG, Pomare EW & Fisher CA Portal and peripheral blood short chain fatty acid concentrations after caecal lactulose instillation at surgery. Gut 33, 1249–1252 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dankert J, Zijlstra JB & Wolthers BG Volatile fatty acids in human peripheral and portal blood: quantitative determination vacuum distillation and gas chromatography. Clin. Chim. Acta 110, 301–307 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gregory JF 3rd et al. Metabolomic analysis reveals extended metabolic consequences of marginal vitamin B-6 deficiency in healthy human subjects. PLoS ONE 8, e63544 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pouteau E et al. Production rate of acetate during colonic fermentation of lactulose: a stable-isotope study in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 68, 1276–1283 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pouteau E, Meirim I, Metairon S & Fay LB Acetate, propionate and butyrate in plasma: determination of the concentration and isotopic enrichment by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry with positive chemical ionization. J. Mass Spectrom 36, 798–805 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Robertson MD, Bickerton AS, Dennis AL, Vidal H & Frayn KN Insulin-sensitizing effects of dietary resistant starch and effects on skeletal muscle and adipose tissue metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 82, 559–567 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pomare EW, Branch WJ & Cummings JH Carbohydrate fermentation in the human colon and its relation to acetate concentrations in venous blood. J. Clin. Invest 75, 1448–1454 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Akanji AO, Humphreys S, Thursfield V & Hockaday TD The relationship of plasma acetate with glucose and other blood intermediary metabolites in non-diabetic and diabetic subjects. Clin. Chim. Acta 185, 25–34 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Akanji AO, Ng L & Humphreys S Plasma acetate levels in response to intravenous fat or glucose/insulin infusions in diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Clin. Chim. Acta 178, 85–94 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Crouse JR, Gerson CD, DeCarli LM & Lieber CS Role of acetate in the reduction of plasma free fatty acids produced by ethanol in man. J. Lipid Res 9, 509–512 (1968). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Fernandes J, Vogt J & Wolever TM Inulin increases short-term markers for colonic fermentation similarly in healthy and hyperinsulinaemic humans. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr 65, 1279–1286 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Simoneau C et al. Measurement of whole body acetate turnover in healthy subjects with stable isotopes. Biol. Mass Spectrom 23, 430–433 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tollinger CD, Vreman HJ & Weiner MW Measurement of acetate in human blood by gas chromatography: effects of sample preparation, feeding, and various diseases. Clin. Chem 25, 1787–1790 (1979). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Pownall HJ et al. Effect of moderate alcohol consumption on hypertriglyceridemia: a study in the fasting state. Arch. Intern. Med 159, 981–987 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Muir JG et al. Resistant starch in the diet increases breath hydrogen and serum acetate in human subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 61, 792–799 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]