Abstract

The prognosis of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (mccRCC) has changed dramatically over the years with the emergence of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) used alone, or in combination with another ICI, or with vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Although major response rates have been observed with ICI, many patients do not respond, reflecting primary resistance, and durable responses remain exceptional, reflecting secondary resistance. Factors contributing to primary and acquired resistance are manifold, including patient-intrinsic factors, tumor cell-intrinsic factors and factors associated with the tumoral microenvironment (TME). While some mechanisms of resistance are common to several tumor types, others are specific to mccRCC. Predictive biomarkers and alternative strategies are needed to overcome this resistance. This review provides an overview of the major ICI resistance mechanisms, highlights the potential of the TME to induce resistance to ICI, and discusses the predictive biomarkers available to guide therapeutic choice.

Keywords: Tumor microenvironment, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, immune checkpoint inhibitor, immune checkpoint inhibitor resistance

Introduction

Kidney cancer accounts for 3%-5% of all cancers and is the seventh and tenth most frequently diagnosed malignancy amongst men and women respectively. Each year, about 330,000 new cases are diagnosed worldwide and 120,000 die from kidney cancer[1]. According to the 2016 OMS classification of renal tumors, clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) is the most common (70%-90%), followed by papillary (10%-15%) and chromophobe RCCs (3%-5%). ccRCC is known to be insensitive to conventional chemotherapy. Until the 2000s, therapeutic options were limited and based upon high doses of the cytokines interleukin-2 (IL-2) and interferon, reflecting ccRCC sensitivity to immunotherapy. Almost 10% of patients treated with IL-2 achieved complete response but the safety profile was often limiting due to cardiac and respiratory toxic effects[2]. During the 2000s, a greater understanding of cancer biology led to increased therapeutic options. As a result, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (VEGFR-TKI) and mechanistic target of rapamycin inhibitors emerged as the new standards of care for metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (mccRCC). VEGFR-TKIs sunitinib[3] and pazopanib[4] became the standard of care for untreated mccRCC. Temsirolimus and everolimus[5] were available as first line treatment for poor-risk patients, according to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) criteria and after VEGFR-TKI failure. In recent years, the standard of care for mccRCC has changed dramatically with the emergence of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) anti-programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) or anti programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), used as monotherapy or in combination with anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) or VEGFR-TKI. Nivolumab (a monoclonal antibody targeting PD-1) has been approved as second-line treatment for mccRCC[6]. Since 2018, new treatment combinations have emerged as first-line for patients with intermediate and unfavorable risk such as the nivolumab plus ipilimumab (targeting CTLA-4) combination[7] and pembrolizumab (targeting PD-1) plus axitinib (Anti VEGFR-1, anti VEGFR-2, anti VEGFR-3 TKI) combination across all International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium (IMDC) prognostic risk groups[8]. Based on the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial, avelumab (targeting PD-L1) plus axitinib combination has also obtained the European Medicines Agency approval as first-line treatment of mccRCC across all IMDC prognostic risk groups irrespective of PD-L1 expression[9].

Accordingly, the rationale of combining ICI and anti-VEGFR TKI is now well established. By reducing VEGF release and hypoxia, the antiangiogenic therapies have immunomodulatory effects. They reduce the proliferation of regulatory T cells (Treg), improve dendritic cell maturation and CD8+ T cells proliferation. By remodeling the vasculature, they also facilitate the penetration of immune cells into the tumor[10].

With these growing therapeutic options, the question of therapeutic sequences to follow arises. To guide the clinician’s choice, predictive biomarkers are urgently required. ICI response biomarkers including tumor mutational burden and PD-L1 expression have failed to identify good responders in mccRCC. Genomic signatures are emerging as promising predictive biomarkers and could solve this major issue. Although ICI have dramatically changed the prognosis of mccRCC through major clinical response and overall response rates (42% with nivolumab-ipilimumab combination and 55% with pembrolizumab-axitinib combination respectively for untreated mccRCC, and 25% for nivolumab in second-line setting), a substantial number of patients do not respond, reflecting primary resistance to ICI. Disease progression rate approaches 100%, reflecting acquired resistance. Factors contributing to primary or acquired resistance are manifold, including patient-intrinsic factors, tumor cell-intrinsic factors and factors related to the tumoral microenvironment (TME).

We will highlight here the ICI resistance mechanisms, some of which are shared by most tumor types while others are specific to ccRCC. In particular, we will shed light on the TME potential to induce ICI resistance. We will also describe the available predictive biomarkers and discuss some recent approaches to overcome ICI resistance in mccRCC patients.

Mechanisms of primary and secondary resistance to ICI

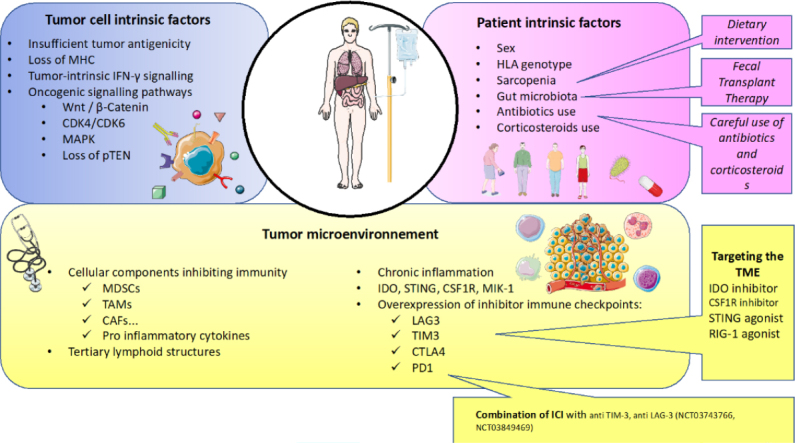

Factors contributing to primary or acquired resistance are manifold, including patient-intrinsic factors (such as sex, age, performance status, comorbidities, gut microbiota, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotype and genetic polymorphisms, use of antibiotics or steroids), tumor cell-intrinsic factors (such as tumor biology, tumor microenvironment, gene mutations or tumor mutational burden) and at the interface between the tumor and the host, the TME is undoubtedly one of the major players of immune and ICI resistance. Here, we will describe the main mechanisms of primary and secondary resistance to ICI occurring in cancer and specifically, in RCC [Figure 1]. For didactic purposes, resistance factors to ICI have been divided into those intrinsically related to the patient, the tumor and the microenvironment. In fact, all these factors interact with each other and have a final impact on anti-tumor immunity.

Figure 1.

Main mechanisms of resistance to current immunotherapy in renal cell carcinoma. The main mechanisms of resistance to current immunotherapy can be divided into three major categories: tumor cell intrinsic factors, patient intrinsic factors and factors related to the tumor microenvironment. Here, some medical interventions to counteract these resistances are described. CAF: cancer associated fibroblasts; CDK4/CDK6: cyclin dependent kinase 4/cyclin dependent kinase 6; CSF1R: colony stimulating factor 1 receptor; CTLA4: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4; CTK: cytokine; IDO: indoleamine 2 3-dioxygenase; IFN: interferon; HLA: human leukocyte antigen; ICI: immune checkpoint inhibitor; LAG3: lymphocyte-activation gene 3; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; MDSCs: myeloid derived suppressor cells; MHC: major histocompatibility complex; PD-1: programmed cell death 1; PTEN: phosphatase and TENsin homolog; RIG-1: retinoic acid-inducible gene 1; STING: stimulator of IFN genes; TAMs: tumor associated macrophages; TIM3: 1-5 T cell immunoglobulin mucin-3; TME: tumor Microenvironment

Patient-intrinsic factors

Sex

Although sex-related dimorphism in the immune response is known, few studies have focused on the effect of gender on ICI efficacy. A recent meta-analysis by Conforti et al.[11] included 11,351 patients with metastatic cancers, mostly melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer and revealed a significant difference in terms of overall survival (OS) between men and women (P = 0.0019), in favor of men[11].

Almost 900 mccRCC patients enrolled in the Checkmate 025 trial (evaluating nivolumab vs. everolimus in second line setting or later) were included in this meta-analysis. Focusing on mccRCC patients, the hazard ratio (HR) for death was 0.84 (0.57-1.24) for women and 0.7 (0.5-0.9) for men, which was similar to the HR observed respectively in melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer patients.

Several hypotheses could explain this difference such as behavioral or biological factors. Firstly, exposure to mutagenic causative factors such as tobacco smoke or ultraviolet light without sun-protective measures is more frequent in men than in women. These behaviors are responsible for a greater increase in tumor mutational burden in men than in women. This has been reported in male patients’ tumors of different histiotypes[11]. Secondly, a role for estrogen modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis has emerged from a few animal studies. Polanczyk et al.[12,13] demonstrated that estrogen has effects on antigen-presenting cells and CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs): estrogen could up-regulate expression of FoxP3 and potentiate the regulatory activity of Tregs through the estrogen receptor alpha. Estrogen can also modulate PD-1 expression on dendritic cells, macrophages or Tregs[12,13].

These findings need to be explored more deeply and the sex-dependent benefit of ICI must be confirmed in further prospective cohorts.

HLA genotype

In a recent study, Chowell et al.[14,15] demonstrated that the functional diversity of the highly polymorphic human-leukocyte antigen class I (HLA-I) genes underlies immunologic control of cancer. They hypothesized that an HLA-I genotype with two alleles with sequences that are more divergent enables presentation of more immunopeptidomes, which may influence treatment response to ICI. Basically, heterozygous patients with more divergent alleles may present a larger set of peptides for T cell recognition than those with less-divergent HLA-1 alleles. To test this hypothesis, they evaluated the germline HLA-I evolutionary divergence by quantifying the physiochemical sequence divergence between HLA-I alleles of each patient’s genotype. A high HLA-I evolutionary divergence was associated with a better response to ICI, both in melanoma receiving anti CTLA-4 or anti PD-(L)1, and in non-small cell lung cancer receiving anti PD-1. Median OS was significantly different between low and high HLA-I evolutionary divergence melanoma patients with almost 8 months vs. nearly 20 months (HR = 0.43, 95%CI: 0.2-0.8, P = 0.0094) respectively. Radiographic responses were also associated with mean HLA-I evolutionary divergence with 57% vs. 64% of clinical benefit in favor of high mean HLA-I evolutionary divergence [P = 0.003, odds ratio (OR) = 0.35]. Comparable results were observed in the non-small cell lung cancer cohort[14,15]. Till now, correlation between the functional diversity of HLA-I genes and immunologic control of cancer has not been specifically studied in mccRCC patients but this scientific concept can be extrapolated to other tumor types.

Sarcopenia

For a long time, sarcopenia has been known to be a negative prognostic marker in the pre-immunotherapy era[16-18]. In a recent retrospective multicenter real-life study, Cortellini et al.[19] included 1000 consecutive advanced cancer patients (including 65% of non-small cell lung cancers, 19% of melanomas and 15% of mccRCCs) treated with ICI and focused on the putative association between sarcopenia (evaluated using cross-sectional image analysis on CT-scans, at the level of the third lumbar vertebra to evaluate skeletal muscle density and the skeletal muscle index) and clinical outcomes [objective response rate (ORR), progression free survival (PFS) and OS]. With a median follow-up of 20.3 months, patients with a low skeletal muscle index had a significant shorter OS (HR = 2.2, 95%CI: 1.3-3.6, P = 0.0026). Multivariate analysis confirmed skeletal muscle index as an independent predictor for OS. It should be noted that no association between skeletal muscle index and clinical response was identified, suggesting that sarcopenia may be prognostic rather than specifically predictive of response to ICI[19].

Gut microbiota

Gut microbiota has been found to significantly impact the response to ICI in both mice and humans with epithelial tumors. Focusing on the metagenomics of stool samples from patients with lung and kidney cancers, Routy et al.[20] revealed a positive correlation between the abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila and the response to ICI in mice receiving anti-PD-1 blockade. Besides, fecal microbiota transplantation from patients who responded to ICI into germ-free or antibiotic-treated mice improved ICI efficiency; in contrast, fecal microbiota transplantation from non-responding patients failed to do so. Oral gavage with Akkermansia muciniphila though, conferred responsiveness to ICI after fecal microbiota transplantation from non-responders. Fecal microbiota transplantation from responders caused accumulation of CXCR3+ CD4+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment and up-regulation of PD-L1 in splenic T cells. This established a cause-effect relationship between the anticancer efficacy of PD-1 blockade and the dominance of distinct commensal species. The dysbiosis may be associated both with malignant disease and concomitant antibiotic use. Following these preliminary results, a high number of translational studies have been launched and results are eagerly awaited.

Antibiotics and steroids use

As discussed above, dysregulation of gut microbiota may contribute to alter the systemic immune response. Antibiotic use seems to be a major cause of dysbiosis and leads to dysregulation of important commensal bacteria. A recent review[21] summarized the currently available evidence addressing the impact of antibiotics on cancer patients receiving ICI. In 2018, Routy et al.[22] focused on patients with non-small cell lung cancer, RCC and urothelial carcinoma, showing that antibiotic use was significantly associated, both in univariate and multivariate analyses, with reduced OS[22]. Regarding renal cell carcinoma, three retrospective studies confirmed this observation. Lalani[23], Derosa et al.[24] and Tinsley et al.[25] all demonstrated a negative impact of antibiotics with a significantly PFS decrease of 5.5 months, 1.9 months and 2.7 months, respectively. Derosa and Tinsley also demonstrated a significant decrease in OS[23-25]. It should be mentioned that in these studies, multivariate analyses were adjusted for antibiotic-independent markers of poor prognosis (such as age, tumor type, recent hospitalization), suggesting that antibiotic use may be an independent prognostic factor.

Data is lacking about the consequences of antibiotic usage with regard to duration (short vs. long course), spectrum (broad spectrum combination vs. single-agent), timing (1, 2 or 3 months before ICI) and the time necessary for repopulation of the gut microbiota after discontinuation. More data is necessary to formulate guidelines for the optimal management of patients who require antibiotics before or during ICI treatment. It is interesting to note that many techniques used to modify an unfavorable gut microbiome into a favorable one are under investigation including fecal microbiota transplantation (NCT03341143), probiotics (NCT03637803, NCT03829111) and diet (NCT01716468).

Steroids are commonly used in oncology to treat routine symptoms such as dyspnea, fatigue, nausea or brain metastases. Steroid use with an equivalent prednisone dose ≥ 10 mg daily is known to induce immunosuppressive effects however, by impairing T cell activation, blocking Th1 expansion, favoring the recruitment of T regs, the expansion of M2 macrophages and altering the microbiota[26]. For these reasons, patients receiving steroids are commonly excluded from ICI clinical trials. Thus, data on ICI efficacy are lacking for these patients.

The impact of baseline steroids on ICI efficacy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer has been reported by Arbour et al.[27]. In this multicente (Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and MSKCC) retrospective analysis, baseline steroids use ≥ 10 mg daily was associated with worse outcomes with lower ORR (7% vs. 18%), lower PFS (P < 0.001) and OS (P < 0.001). In multivariate analysis of the pooled population, after adjusting for confounding factors, baseline steroid use remains significantly associated with worse outcomes. Interestingly, in the MSKCC cohort, patients who discontinued steroids 1 to 30 days before starting ICI had intermediate PFS and OS. It should be noted that on-treatment steroid use to manage immune-related adverse events does not negatively affect ICI efficacy[28-31]. Fucà et al.[32] studied the modulation of peripheral blood immune cells by early use of steroids and its association with outcomes in patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving ICI. No difference was found between patients receiving steroids at any time of the ICI course and never-exposed patients. By contrast, the early use of steroids (during the first month of treatment) was associated with low PFS (1.98 vs. 3.94 months, P = 0.0003) and OS (4.9 vs. 15.0 months, P < 0.001)[32]. To our knowledge, this issue has not been specifically studied in mccRCC patients.

Tumor cell-intrinsic factors

Tumor biology

The Cancer-Immunity Cycle described by Chen and Mellman in 2013 summarizes the seven major steps of cancer immunity from antigen release to cancer cell destruction. The major steps are: (1) release of cancer cell antigens through cancer cell death; (2) cancer antigen presentation via antigen presenting cells; (3) priming and activation of antigen presenting cells and T cells; (4) trafficking of T cells to tumors; (5) infiltration of T cells into tumors; (6) recognition of cancer cells by T cells; and (7) cancer cell destruction. As described above, resistance can occur at each step of the Cancer-Immunity Cycle[33]. Consequently, the anti-tumor immune response results from interactions between tumor cells and their microenvironment.

Insufficient tumor antigenicity

The first reason why a tumor will not respond to ICI is the lack of recognition by T cells due to the absence of tumor neoantigens[34]. This is illustrated by the positive correlation between tumor mutational burden and ICI response across malignancies[35]. Another example is the high ICI response rate of patients harboring microsatellite instability due to mismatch repair defects. Special attention should be given to mRCC because no positive correlation between tumor mutational burden and ICI response was observed in this tumor type. In a small cohort of 34 patients, Labriola et al.[36] showed that neither tumor mutational burden nor PD-L1 expression was correlated with patient outcomes or with ICI response[36]. Interestingly, Turajlic et al.[37] showed that ccRCC tumors harbour the highest rate of insertion-deletion (indels) DNA alterations, leading to one of the highest neoantigenicity potential. This may be a strong rationale to explain ICI response among mccRCC patients[37]. Voss et al.[38] showed that in two cohorts of mccRCC treated with anti-PD-1, a high frameshift count was associated with better OS (HR = 0.85; P = 0.006)[38]. Interestingly, in patients treated with TKI, this association was not significant (P = 0.07) and mutation as well as neoantigen burden did not have an impact on OS in patients treated with anti-PD-1 (HR = 1.02; P = 0.6; HR = 1.01; P = 0.69, respectively).

Tumor-intrinsic interferon gamma-signaling

An efficient T cell response against a tumor antigen depends on activation of the intrinsic interferon gamma (IFNγ) pathway within the microenvironment. As a result, Janus Kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) is activated, leading to PD-L1 expression, through the activation of interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1). This adaptive expression of PD-L1 on the surface of tumor cells negatively regulates the anti-tumor T cell response. A genetic deficiency in IFNγ signaling pathways is associated with ICI inefficacy[39]. It should also be noted that IFNγ signaling enhances class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigen presentation. In MHC deficient tumor-cells, pretreatment with IFNγ is required to express the antigen processing machinery and the class I MHC complex[40]. The IFNγ pathway also enables the recruitment of immune cells and has direct anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects on tumor cells[41]. Zaretsky et al.[42] revealed resistance-associated loss-of-function mutations in the genes encoding interferon-receptor-associated JAK1 or JAK2, concurrent with deletion of the wild-type allele. JAK1 and JAK2 truncating mutations resulted in a lack of response to IFNγ, including lack of response to its anti-proliferative effects on cancer cells[42].

Pro-inflammatory cytokines

The RCC TME is associated with pro-inflammatory conditions. This is due to tissue damage that induces the release of pro-inflammatory molecules and cytokines such as adenosine triphosphate, IL-8, macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) or IFNγ. These cytokines recruit circulating leukocytes and have a pro-tumorigenic effect via the promotion of genomic instability, survival, cellular growth, angiogenesis and epithelial to mesenchymal transition. They also promote immunosuppression[43]. IFNγ induces increased expression of PD-1 on T cells and immune cells. The sustained expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 is responsible for T cell exhaustion, via the [Src homology 2 (SH2) domain-containing phosphatase 2] SHP2 recruitment. Transcriptional factors such as (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) STAT-3 and (interferon regulatory factor 1) IRF1, induced by pro-inflammatory conditions, also modulate the expression of PDL1 and PDL2. IL-1, IL-6, IL-11, IL-17 and TNF alpha promote Treg expansion and increase T cell exhaustion[44,45].

Regulation by oncogenic signaling.

Several signaling pathways have recently been identified as potential ICI resistance mechanisms. Here, we highlight three major oncogenic pathways among the most documented.

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is involved in many biological processes from hematopoietic stem cell development, embryogenesis, and cell differentiation to immune regulation[46]. In most cancers, Wnt/β-catenin is overexpressed. Using human metastatic melanoma, Spranger et al.[46] first demonstrated a correlation between activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and absence of T cell gene expression signatures. Using mouse melanoma models, they also demonstrated that overexpression of Wnt/β-catenin is associated with T cell exclusion (resulting in “immune-desert” tumors) and resistance to anti-PD(L)-1 and anti CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody therapies[46]. This observation was confirmed in other tumor types including ovarian carcinoma, head and neck cancer, adenoid cystic carcinoma and urothelial carcinoma[47-49]. Wnt/β-catenin is also involved in the regulation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) and the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma receptor), both inducing immunosuppressive effects[50]. A role in tumor stemness and dedifferentiation is also well-described[51].

The mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) pathway results mainly in VEGF, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-10 production and has known inhibitory effects on T cell recruitment and function. The MAPK pathway is also responsible for negative regulation of antigen presentation, MHC expression and reduced sensitivity to the anti-proliferative effects of IFNγ and TNFα[39,52].

The comprehensive molecular characterization of ccRCC, led by The Cancer Genome Atlas Program, has identified the PI3K (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase)/AKT (Protein Kinase B) pathway as one of the most currently altered pathways. The loss of Phosphatase and TENsin homolog (PTEN) is also a frequent molecular alteration[53]. The pathways activated after PTEN loss are responsible for poor T cell recruitment via activation of the autophagosome, and for a reduced type I interferon response to pathogen associated molecular patterns[54].

Cyclin dependent kinase 4 and 6 (CDK4/6) and their co-factor D-type cyclins promote progression of the cell cycle from the G1 to S phase. In the last few years, four studies have underlined the impact of CDK4/6 inhibition on immune response. It was shown that the CDK4/6 inhibitor abemaciclib, in combination with anti-PD-L1 ICI, has a greater efficacy in mouse breast cancer models than either agent alone[55,56]. The positive effect of CDK4/6 inhibitors on antitumor immunity was attributed to their impact on T cells. Greater IL-2 production and increased T cell tumor infiltration were observed[57].

Loss of MHC

The loss of class I and II MHC molecules can occur via multiple genetic and epigenetic mechanisms[58], leading to the absence of recognition by cytotoxic T cells, resulting in immune-escape. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms may potentially affect all the genes involved in the antigen processing and presenting machinery, particularly the gene of the B2-microglobulin (B2M) and thereby, MHC class I. Ribas’ team showed by whole-exome sequencing that a truncating mutation in the gene encoding for B2M led to loss of surface expression of MHC class I, which in turn resulted in loss of response to ICI in melanoma patients[42]. Sade-Feldman et al.[59] also demonstrated that the loss of heterozygosity at the B2M locus was associated with lower OS in melanoma patients receiving ICI[59].

At the tumor-host interface: the tumor microenvironment as a major player of immune and ICI resistance

The bulk of the tumor is not limited to the tumor cells per se but include many other cells interacting with them within a cellular niche called the tumor microenvironment (TME), which sustains the growth of the tumor. The main cellular components of the TME are immune cells (including but not limited to natural killer (NK), T and B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, etc.) and stromal cells (endothelial cells and fibroblasts). All these protagonists play an essential role in the development, progression and relapse of tumors. By combining these factors, the TME regulates the response to ICI and is a major target to overcome both primary and secondary ICI resistance. The composition and functional properties of the TME can be analyzed in order to find predicting profiles of ICI efficacy.

Main factors and their role in resistance to antitumor immune response

T cells

RCC is one of the most T cell-enriched tumors. Compared to other tumor types, the high densities of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) is associated with a poor prognosis[60,61]. Many hypotheses underlie this contra-intuitive prognosis on the impact of CD8 in ccRCC: amongst them, it was demonstrated that CD8 TILs in ccRCC are mostly exhausted with frequent co-expression of PD-1 and lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3), due to a lack of antigen presentation by dysfunctional/immature dendritic cells[62]. Until recently, the poor prognostic feature of CD8 TIL in ccRCC was controversial. Choueiri et al.[5] reported exploratory data on CD8 infiltration from the randomized phase III trial JAVELIN RENAL 101, comparing avelumab (anti-PD-L1)-axitinib vs. sunitinib. High CD8 infiltration was associated with poor PFS for patients treated with sunitinib but not for patients treated with the avelumab-axitinib combination, suggesting that CD8 infiltration has prognostic value in ccRCC but loses it in patients treated with ICI. These data seem to be discordant with those coming from the NIVOREN-GETUG AFU 26 ancillary phase II study, where the highest CD8 infiltration in the invasive margin (scored 3 vs. 0-2) was associated with worse PFS (HR = 3.96, P < 0.0001) and OS (HR = 2.43, P = 0.04) for 324 patients treated with nivolumab. Nevertheless, only 7 of 324 patients were implicated and when comparing CD8 infiltrates between 0-1 and 2-3, no association was found with survival outcomes[63]. Moreover, CD8 density in the core of the tumor was not associated with outcomes (all P < 0.05 for PFS and OS). Interestingly, Voss et al.[38] did not find any association between CD8 density and clinical benefit of ICI in two cohorts of mccRCC patients (P = 0.22)[38].

In 2017, Giraldo et al.[64] studied 40 primary ccRCCs. Resected tumors could be divided into three dominant immune profiles: (1) immune-regulated, characterized by polyclonal/poorly cytotoxic CD8+PD-1+ T cell immunoglobulin and Mucin-Domain Containing protein 3 (Tim-3)+ Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (Lag-3)+ TILs and CD4+ Inducible Co-Stimulator (ICOS)+ cells with a Treg phenotype (CD25+CD127-Fox+3+/Helios+GITR+), that developed in inflamed tumors with prominent infiltration by dysfunctional dendritic cells highly expressing PD-L1; (2) immune-activated, enriched in oligoclonal/cytotoxic CD8+PD-1+Tim-3+TILs, that represented 22% of the tumors; and (3) immune-silent, enriched in TILs exhibiting RIL-like phenotype, that represented 56% patients of the cohort. Immune-regulated and immune activated tumors have a phenotypic signature that displayed aggressive histologic features associated with a high risk of disease progression, supporting the belief that they could benefit from ICI in combination with TME-modulating adjuvant treatment and closer clinical follow-up[64].

Moreover, analysis of immune infiltration in RCC from the Cancer Genome Atlas showed a higher proportion of regulatory T cells in patients with a worse outcome (HR = 1.59, 95%CI: 1.23-0.06; P < 0.01). Mutated genes in this RCC cohort such as BIRC6, BAP1 and PIK3CA were associated with a higher fold-change in Tregs[65].

Tumor associated macrophage

In 2011, a negative correlation between the anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype (M2)(CD163+) and survival outcomes in RCC was identified[66]. In response to inflammatory stimuli, macrophages undergo M1 (classical) or M2 (alternative) activation. The M1 type produces high levels of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12, IL-23 and IL-6. M2 macrophages can be subdivided into subsets called M2a, M2b, M2c and M2d[67,68]. The M2a phenotype is obtained by Th2 cytokine stimulation (IL-4, IL-13); activation of Toll-like receptors and immune complexes induce M2b; and IL-10 polarizes the M2c subtype. Tumor cells are able to switch the potential phenotype of macrophages into tumor-associated macrophages, which are characterized as the M2d subtype[67], through the production of colony stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) for example. They express multiple receptors or ligands of inhibitory receptors such as PD-L1, PD-L2, B7-1. The presence of extensive tumor-associated macrophage infiltration into the RCC microenvironment contributes to cancer progression and metastasis by stimulating angiogenesis, tumor growth, cellular migration and invasion, as well as recruitment of Tregs to the tumor site by secreting CCL20 or CCL22. Therapeutic strategies have been suggested to suppress tumor-associated macrophage recruitment, to switch them back to the antitumor M1 phenotype[69].

Surprisingly, Voss et al.[38] recently reported that M2 macrophages, which were the most abundant infiltrating cell type, were associated with durable clinical benefit from anti-PD-1 therapy (P < 0.001). This association was not found in patients treated with TKI (P = 0.15)[38]. In the NIVOREN ancillary cohort, CD163 (M2 macrophages) with higher densities in the invasive margin was associated with better PFS (HR = 0.69, P = 0.016) but not OS (P = 0.5) in patients treated with nivolumab[70].

B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures

The major role of B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) in cancer biology has recently emerged. Five years ago, B cells with a regulatory role (also known as Bregs) were characterized as immunosuppressive cells secreting the immunosuppressive mediators IL-10 and transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ), which regulate Treg differentiation[71].

A second population of more “classical” B cells has also been characterized within the tumor and in the stroma of metastases, defined by a strong memory response against tumor associated antigens[72]. Analysis from transcriptomic data of tumor samples, the Microenvironment Cells Populations-counter (MCP-counter), shows higher B cell related genes in a responder’s tumor as compared to non-responders in melanoma and ccRCC[73]. In sarcoma for example, patient clusters (SIC E) expressing high plasma cell signatures demonstrate an improved prognosis with anti PD-1 treatment[74]. TLS are lymph-node-like structures with a T cell zone with mature dendritic cells covering a follicular zone rich in proliferating and differentiating B cells as a germinal center. These structures are acting against tumor immunity and are associated with a good prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung, colorectal, breast, head and neck, pancreatic, and gastric cancers, RCC or melanoma. Depending on the maturation state and the cancer type (hepatocellular carcinoma), TLS can constitute a niche that favors the emergence of transformed cells and the development of activated Tregs[75,76].

Hypoxia

RCC is one of the most hypervascular tumors composed of disorganized vessels. As such, nutrient and oxygen intake are insufficient, leading to hypoxia and a lower pH, both of which contribute to tumor progression[77]. Hypoxia induces the up-regulation of different genes involved in glucose metabolism, cell angiogenesis, cell proliferation, polarization of macrophages into Tumor Associated Macrophages, Treg recruitment and infiltration of myeloid derived suppressor cells leading to the inhibition of CD3+ T cells and the cytotoxic functions of CD8+ T cells[78,79]. Consequently, hypoxia-induced factor 1a and 2a release (HIF-1a and HIF-2a) induces increased expression of PD-L1 in tumor cells[80,81]. Hypoxia also enhances Treg abundance and NK-mediated antitumor immunity (synergized with B7-1) in vitro as well as in vivo[82].

This high level of HIF-1 and HIF-2 mediates the generation VEGF[82], which acts as an immune escape pathway by increasing the expression of the immune checkpoints CTLA4, TIM3, LAG3 on T cells and PD-L1 on dendritic cells[79]. Hypoxic tissues are enriched in adenosine deposits generated by CD39-CD37, which contribute to immune escape by suppressing the effect of T cells[83].

Protein polybromo-1 expression and other immune checkpoints

Protein polybromo-1 (PBRM-1) is a major component of the polybromo-associated BAF (PBAF) form of the SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable (SWI/SNF) chromatin remodeling complex. Inactivating mutations in this complex are common in a variety of cancers[84]. Using a clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) associated protein 9 (Cas9) screen, Pan et al.[84] demonstrated that inactivation of PBRM1 sensitizes mouse melanoma cells to T cell killing. PBAF-deficient tumor cells produce more chemokines in response to IFNγ, promoting cytotoxic T cell functions[84]. Mutations in PBRM1 occur in 40% of ccRCC patients[85]. Using whole exome sequencing, Miao et al.[86] demonstrated that the loss-of-function mutation in the PBRM1 gene was associated with clinical benefit in 35 mccRCC patients receiving ICI anti PD-1. PBRM-1 loss-of-function was enriched in tumors from patients experiencing a clinical benefit (P = 0.012). This was confirmed in an independent validation cohort[86] and in a recent post-hoc analysis of archival tumor tissue from 382 patients enrolled in the Checkmate 025 phase III trial. PBRM1 mutations were associated with an improved PFS and OS in patients receiving nivolumab[87]. Vano et al.[70] recently reported results on PBRM-1 protein status in 324 patients treated with nivolumab within the NIVOREN phase II trial (mentioned above). Better OS was found for patients with PBRM-1 loss with 12-month survival rates of 83.7% vs. 74% (P = 0.05). PBRM-1 loss was also associated with higher PD-1 and LAG-3 expression, and higher macrophage and CD8 T cell densities. Conversely, LAG-3 expression tended to be associated with a lower OS[70]. Nonetheless, inconsistent results have been observed. In the IMmotion 150 phase II study, PBRM-1 mutations were associated with improved PFS in the sunitinib group (HR = 0.38, 95%CI: 0.2-0.7). Atezolizumab monotherapy was associated with worse PFS compared to sunitinib in the PBRM1 mutant subgroup[88].

In an analysis of CheckMate-010 phase II trial, CD8+PD-1+TIM-3-LAG-3- tumor infiltrating cells were associated with a high level of T cell activation, a longer median immune related PFS and a higher immune related ORR to nivolumab[89]. PRBM-1 loss, TIM-3 and LAG-3 expression were all found in more aggressive mccRCC and could be therapeutic targets for ICI.

Innovative approaches to overcome ICI resistances in mccRCC: ongoing trials and predictive tools

Targeting the microenvironment

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 inhibitors

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO-1) upregulation is a key driver of T cell nutrient deprivation and can be targeted therapeutically. A short study on 15 mccRCC patients published in 2018 showed that IDO-1 overexpression (> 10%) in tumor endothelial cells was more frequent in case of response to nivolumab and associated with a better PFS. This would suggest that IDO could be used as a biomarker[90].

At the ASCO 2018, Mitchell et al.[91] reported the result of combination treatment with the oral IDO-1 enzyme inhibitor epacadostat and PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab. Activity in advanced solid tumors mainly concerned melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer and mccRCC, and was observed in the phase I/II ECHO-202/KEYNOTE 037 trial. An objective response occurred in 25 (40%) of 62 patients including 8 with complete responses and 13 with stable disease. Responses were observed for 2 patients with mccRCC out of 11[91]. These results lead to the phase III study, ECHO-301/KEYNOTE-252[92], comparing epacadostat plus pembrolizumab vs. placebo in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma. In this trial, epacadostat failed to improve PFS or OS. The development of IDO-1 inhibitors was stopped after these negative results.

Colony stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibitor

As previously described, M2 macrophages promote tumor growth, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis as well as treatment resistance. Colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) expression allows the switching of type 1 macrophages into type 2 tumor-associated macrophages[93]. Combinations of CSF1R inhibitor and ICI are under investigation in phase I trials (NCT02718911, NCT02526017).

Stimulator of interferon genes and retinoic acid-inducible gene I agonists

Stimulator of interferon genes (STING) and retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-1) are key mediators of nucleic acid sensing and thus, agonists targeting this two pathways are in early clinical development[94]. The STING pathway promotes IκB kinase and activates nuclear factor-kappa B and interferon regulatory factor 3, thus increasing production in pro-inflammatory cytokines[95]. RIG-1 contributes to the production and stimulation of immune cells, such as NK and CD8+ T cells[96].

Two phase I trials are currently assessing STING agonist and RIG-1 agonist as monotherapy or in combination with ICI respectively in patients with metastatic solid tumors including mccRCC (NCT03010176 and NCT03739138).

Targeting other immune checkpoints

TIM-3

As discussed above, TIM-3 and PD-1 co-expression on CD8 T cells is associated with worse outcomes including higher TNM stage, larger tumor size and lower PFS[97]. These findings argue for a therapeutic strategy targeting Tim-3 alone, or in combination with anti-PD-1/PD-L1. In 2018, there were four ongoing phase I trials assessing anti-TIM 3 antibodies: three in metastatic solid tumors and one in hematologic malignancies[98]. In 2019, another clinical trial assessing anti-TIM3 and anti-PD1 in combination has been open to patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme (NCT03961971). There has not been a clinical trial focusing on mccRCC to this day.

LAG-3

LAG-3 (also known as CD223) is another checkpoint identified on exhausted CD8 T cells[64]. Many clinical trials targeting PD-1 and/or LAG-3 in metastatic solid tumors including mRCC patients are ongoing[99]. In mRCC, a phase I clinical trial evaluating the safety of IMP321, a soluble LAG-3 Immunoglobuline fusion protein agonist, showed promising activity and acceptable toxicity[100]. Relatlimab, an anti-LAG3 antibody is under investigation, in combination with nivolumab in an ongoing phase II trial (NCT02996110). XmAb22841, a bispecific antibody targeting CTLA-4 and LAG-3, used alone or in combination with pembrolizumab, is evaluated in a phase 1 clinical trial for patients with select advanced solid tumors, including mccRCC (NCT03849469) [Tables 1-3].

Table 1.

Major tumor cell intrinsic factors involved in ICI resistance mechanisms in ccRCC

| Tumor cell intrinsic factor | Status | Consequences | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interferon gamma-signaling | Activation | JAK-STAT pathway activation and PD-L1 overexpression | [38] |

| Enhancement of class I MHC complex | [39] | ||

| Recruitment of immune cells | [40] | ||

| Pro-inflammatory cytokines | High release | Genomic instability, promotion of tumor cells survival, angiogenesis | [44] |

| mesenchymal to epithelial transition. Immunosuppression | |||

| Wnt/β-catenin pathway | Over-expression | T cell exclusion, iregulation of IDO1 and PPARγ | [47,51] |

| PTEN | Loss of function | Inhibition of T cell recruitment | [55] |

| CDK4/6 | Over-expression IL-2 production, increased T cells tumor infiltration | Tumor progression | [58] |

| MAPK pathway | Over-expression | Inhibition of T cell recruitment, negative regulation of antigen presentation | [38,53] |

ICI: immune checkpoint inhibitors; ccRCC: clear cell renal cell carcinoma; JAK-STAT: Janus Kinase - signal transducers and activators of transcription; PD-L1: programmed cell death ligand 1; MHC: major histocompatibility complex; IDO1: indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1; PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; PTEN: phosphatase and TENsin homolog

Table 2.

Major tumor micro environment components involved in ICI resistance mechanisms in ccRCC

| TME components | Status | Prognosis in RCC | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD8+ T cells | High density | Poor | [61,63] |

| Regulatory CD4+ T cells | High density | Poor | [61] |

| Tumor associated Macrophages | High density | Poor | [61,67] |

| B cells | High density | Good | [61] |

| Tertiary Lymphoid Structure | High density | Good | [61,74] |

| Immune checkpoints and molecules of interest | |||

| PBRM1 | Loss of function | Good for pts receiving anti PD-1 nivolumab | [86,89] |

| LAG3 | Overexpression | Poor | [89] |

| TIM3 | Overexpression | Poor | [89] |

| PD-1 | Overexpression | Poor | [89] |

| PD-L1 | Overexpression | Poor | [89] |

TME: tumor micro environment; ICI: immune checkpoint inhibitors; ccRCC: clear cell renal cell carcinoma; PBRM1: protein polybromo-1; PD1: programmed cell death 1; PD-L1: programmed cell death ligand 1; LAG3: lymphocyte-activation gene 3; TIM3: 1-5 T cell immunoglobulin mucin-3

Table 3.

The most promising and innovative approaches to overcome such resistance

| Targeted molecule | therapeutic combination | Results | Trial |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDO | Epacadostat (IDO1 enzyme inhibitor) + Pembrolizumab | 40% objective response (62 total patient) | ECHO-202/KEYNOTE 037 |

| Epacadostat + Pembrolizumab or Placebo | Failed to improve OS or PFS | ECHO-301/KEYNITE-252 | |

| CSF1R | CSF1R inhibitors + ICI | Ongoing | NCT02718911/NCT02526017 |

| STING | Inhibitor + Pembrolizumab | Ongoing | NCT03010176 |

| RIG-1 | Inhibitor + Pembrolizumab | Ongoing | NCT03739138 |

| TIM3 | No clinical trials focusing on mccRCC | ||

| LAG3 | Anti-LAG-3 antibody + ICI | Ongoing | NCT02996110 |

| Relatlimab (Anti-LAG-3) + Nivolumab | Ongoing | NCT02996110 | |

| LAG3 and CTLA4 | XmAb22841 (bispecific) + Pembrolizumab or alone | Ongoing | NCT03849469 |

IDO: indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; CSF1R: colony stimulating factor 1 receptor; STING: stimulator of IFN genes; RIG-1: retinoic acid-inducible gene 1; TIM3: 1-5 T cell immunoglobulin mucin-3; LAG3: lymphocyte-activation gene 3; CTLA4: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4; ICI: immune checkpoint inhibitors; PFS: progression free survival; OS: overall survival; mccRCC: metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma

Predictive tools to guide therapeutic choices

In most tumor types, PD-L1 expression status alone is insufficient to determine which patients would benefit from ICI therapy[101]. Focusing on RCC, none of the ICIs need PD-L1 expression to be prescribed[6-9]. Current clinical, biological and histological markers such as the International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium (IMDC) score, Fuhrman grade, necrosis, vascular emboli or performance status are also imperfect in guiding our therapeutic decisions. Molecular signatures using next generation sequencing or cluster analysis are emerging as new, promising theragnostic assessments for immunotherapy in RCC. We will discuss here the main genomic signatures available in ccRCC.

Exploratory analyses were performed on the immune signatures assessed in the IMmotion 151 phase III trial comparing atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sunitinib for mccRCC patients in the first line setting. A high angiogenesis signature was associated with an improved PFS with sunitinib. PFS was not improved by the combination of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in the high angiogenesis signature group, whereas a significant benefit was observed in the low angiogenesis signature group. In the high T effector genes signature, PFS was improved by the combination of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab[102]. Choueiri et al.[103] reported, at the 2019 ASCO congress, outcomes from biomarker analysis on tumor samples from the JAVELIN RENAL 101 Study (a phase III study assessing avelumab plus axitinib treatment for mccRCC patients in the first line setting). They assessed somatic mutations and analyzed relevant gene expression signatures (GES): effector T cells, angiogenesis, T cell-inflamed, and a novel immune-related signature incorporating pathway indicators for T and NK cell activation and IFNγ signaling, among others. PD-L1 expression (≥ 1% immune cells) was associated with the longest PFS in the avelumab plus axitinib arm, and the shortest in the sunitinib arm. Significant arm-specific treatment differences in PFS were observed relative to wildtype when mutations in genes such as CD1631L, PTEN or DNMT1 were present. Tumor mutational burden did not distinguish patients with respect to PFS and updated data will be presented[103].

Ccrcc1-4 classification emerged in 2007 with the Tumor Identity Card program (“Carte d’Identité des Tumeurs” or CIT) for molecular characterization in solid tumors. Four molecular groups (ccrcc1 to 4) were identified: ccrcc1 = “c-myc-up,” ccrcc2 = “classical,” ccrcc3 = “normal-like” and ccrcc4 = “c-myc-up and immune-up”. Ccrcc4 subtype included frequent sarcomatoïd differentiation and high expression of markers of inflammation, such as members of the TNF and IRF families. Cytokine analyses revealed a strong expression of myeloid and T cell homing factors with their corresponding receptors and Th-1-related factors such as IFNγ and IL12. The immune suppressive IL10 and inhibitory receptors LAG3, PD-1, PD-L1 and PD-L2 were also highly expressed. In conclusion, the immune microenvironment in Ccrcc4 tumors is strongly inflammatory, Th1-oriented but immunologically suppressed. Rare mutations in VHL (Von Hippel Lindau) and PBRM1 were found in ccrcc4 tumors, but were frequent in ccrcc1 and ccrcc2 tumors without an effect on sunitinib response. The ccrcc1/ccrcc4 tumors represented 76% of Fuhrman grade 4 compared with 56% in ccrcc2/ccrcc3 tumors, suggesting a less differentiated stem-cell phenotype. The ccrcc2 subtype was not characterized by specific pathways and showed an intermediate expression signature between ccrcc3 and ccrcc1/ccrcc4-related profiles[104].

BIONIKK is an ongoing multicentric molecular-driven randomized phase 2 trial (NCT02960906). This is the first trial studying the personalization of treatment according to tumor molecular characteristics in mccRCC. Using a 35-gene expression mRNA signature, patients were divided into four molecular groups (1 to 4). Patients in groups 1 and 4 were randomized to receive nivolumab alone (arms 1A and 4A) or nivolumab plus ipilimumab for four injections followed by nivolumab alone (arms 1B and 4B). Patients in groups 2 and 3 were randomized to receive nivolumab plus ipilimumab followed by nivolumab alone (arms 2B and 3B) or a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (sunitinib or pazopanib at the investigator’s choice (arms 2C and 3C)[105]. The main objective is to evaluate the response rate by treatment and molecular group.

Conclusion

The prognosis of mccRCC patients has changed dramatically over the past few years. Impressive response rates including complete responses have been observed with ICI, used either as monotherapy or in combination with other ICIs or anti-angiogenic therapies. Many patients do not respond however, reflecting primary resistance and durable treatment response remains rare with resistance rates approaching 100%. ICI resistance mechanisms are manifold including patient-intrinsic factors, tumor cell-intrinsic factors and factors associated with the TME. Many innovative approaches to overcome ICI resistance are under investigation in phase I clinical trials on mccRCC. Due to the emergence of new study methods, the TME composition and its role in promoting tumor and therapy resistance is increasingly better understood. The TME molecules such as IDO-1, CSF1R, STING, RIG-1 and the immune checkpoints TIM-3 and LAG-3 are possible areas for future research. Besides these new therapeutic combinations, genomic signatures are emerging as exciting predictive biomarkers to guide treatment choice and overcome primary resistance. Results of the ongoing phase II clinical trial BIONIKK are awaited to, hopefully, bring new insights on this challenging field.

Declarations

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to the conception and writing of the review: Moreira M, Pobel C, Epaillard N, Simonaggio A, Oudard S, Vano YA

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Moreira M, Pobel C, Epaillard N, Simonaggio A declared that there are no conflicts of interest; Oudard S declared honoraria for advisory board from Pfizer, Bayer, MSD, Novartis, Ipsen, Merck; Vano YA declared honoraria for advisory board from BMS, MSD, Pfizer, Novartis, Merck, Roche, Ipsen.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2020.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenblatt J, McDermott DF. Immunotherapy for renal cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2011;25:793–812. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, et al. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3584–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sternberg CN, Hawkins RE, Wagstaff J, Salman P, Mardiak J, et al. A randomised, double-blind phase III study of pazopanib in patients with advanced and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final overall survival results and safety update. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1287–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choueiri TK, Escudier B, Powles T, Tannir NM, Mainwaring PN, et al. METEOR investigators Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma (METEOR): final results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:917–27. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, George S, Hammers HJ, et al. CheckMate 025 Investigators Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1803–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motzer RJ, Rini BI, McDermott DF, Arén Frontera O, Hammers HJ, et al. CheckMate 214 investigators Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in first-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma: extended follow-up of efficacy and safety results from a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1370–85. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30413-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rini BI, Plimack ER, Stus V, Gafanov R, Hawkins R, et al. KEYNOTE-426 investigators Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1116–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motzer RJ, Penkov K, Haanen J, Rini B, Albiges L, et al. Avelumab plus Axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1103–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan KA, Kerbel RS. Improving immunotherapy outcomes with anti-angiogenic treatments and vice versa. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:310–24. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conforti F, Pala L, Bagnardi V, De Pas T, Martinetti M, et al. Cancer immunotherapy efficacy and patients’ sex: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:737–46. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polanczyk MJ, Hopke C, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. Estrogen-mediated immunomodulation involves reduced activation of effector T cells, potentiation of Treg cells, and enhanced expression of the PD-1 costimulatory pathway. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84:370–8. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polanczyk MJ, Hopke C, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. Treg suppressive activity involves estrogen-dependent expression of programmed death-1 (PD-1). Int Immunol. 2007;19:337–43. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chowell D, Krishna C, Pierini F, Makarov V, Rizvi NA, et al. Evolutionary divergence of HLA class I genotype impacts efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2019;25:1715–20. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0639-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chowell D, Morris LGT, Grigg CM, Weber JK, Samstein RM, et al. Patient HLA class I genotype influences cancer response to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Science. 2018;359:582–7. doi: 10.1126/science.aao4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jouinot A, Vazeille C, Goldwasser F. Resting energy metabolism and anticancer treatments. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2018;21:145–51. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soldati L, Di Renzo L, Jirillo E, Ascierto PA, Marincola FM, et al. The influence of diet on anti-cancer immune responsiveness. J Transl Med. 2018;16:75. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1448-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid D, Leitzmann MF. Association between physical activity and mortality among breast cancer and colorectal cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2014;25:1293–311. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cortellini A, Bozzetti F, Palumbo P, Brocco D, Di Marino P, et al. Weighing the role of skeletal muscle mass and muscle density in cancer patients receiving PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors: a multicenter real-life study. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1456. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58498-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, Duong CPM, Alou MT, et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018;359:91–7. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elkrief A, Derosa L, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L, Routy B. The negative impact of antibiotics on outcomes in cancer patients treated with immunotherapy: a new independent prognostic factor? Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1572–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Routy B, Gopalakrishnan V, Daillère R, Zitvogel L, Wargo JA, et al. The gut microbiota influences anticancer immunosurveillance and general health. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:382–96. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lalani AK. ASCO GU 2018: antibiotic use and outcomes with systemic therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). Available from: https://www.urotoday.com/conference-highlights/asco-gu-2018/asco-gu-2018-renal-cancer/102013-asco-gu-2018-antibiotic-use-and-outcomes-with-systemic-therapy-in-metastatic-renal-cell-carcinoma-mrcc.html. [Last accessed on 13 Feb 2020]

- 24.Derosa L, Hellmann MD, Spaziano M, Halpenny D, Fidelle M, et al. Negative association of antibiotics on clinical activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced renal cell and non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1437–44. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tinsley N, Zhou C, Villa S, Tan G, Lorigan P, et al. Cumulative antibiotic use and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:3010. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahata B, Zhang X, Kolodziejczyk AA, Proserpio V, Haim-Vilmovsky L, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals T helper cells synthesizing steroids de novo to contribute to immune homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1130–42. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arbour KC, Mezquita L, Long N, Rizvi H, Auclin E, et al. Impact of baseline steroids on efficacy of programmed cell death-1 and programmed death-ligand 1 blockade in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2872–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.79.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santini FC, Rizvi H, Wilkins O, van Voorthuysen M, Panora E, et al. Safety of retreatment with immunotherapy after immune-related toxicity in patients with lung cancers treated with anti-PD(L)-1 therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:9012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horvat TZ, Adel NG, Dang TO, Momtaz P, Postow MA, et al. Immune-related adverse events, need for systemic immunosuppression, and effects on survival and time to treatment failure in patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab at memorial sloan kettering cancer center. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3193–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weber JS, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, Topalian SL, Schadendorf D, et al. Safety profile of nivolumab monotherapy: a pooled analysis of patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:785–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wakuda K, Miyawaki T, Miyawaki E, Mamesaya N, Kawamura T, et al. The impact of steroid use on efficacy of immunotherapy among patients with lung cancer who have developed immune-related adverse events. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:e20583. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.e20583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fucà G, Galli G, Poggi M, Lo Russo G, Proto C, et al. Modulation of peripheral blood immune cells by early use of steroids and its association with clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. ESMO Open. 2019;4:e000457. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2018-000457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gubin MM, Zhang X, Schuster H, Caron E, Ward JP, et al. Checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy targets tumour-specific mutant antigens. Nature. 2014;515:577–81. doi: 10.1038/nature13988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1 inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2500–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1713444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Labriola M, Zhu J, Gupta R, McCall S, Jackson J, et al. Characterization of tumor mutational burden (TMB), PD-L1, and DNA repair genes to assess correlation with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) response in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:589. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.7_suppl.589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turajlic S, Litchfield K, Xu H, Rosenthal R, McGranahan N, et al. Insertion-and-deletion-derived tumour-specific neoantigens and the immunogenic phenotype: a pan-cancer analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1009–21. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30516-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voss MH, Novik JB, Hellmann MD, Ball M, Hakimi AA, et al. Correlation of degree of tumor immune infiltration and insertion-and-deletion (indel) burden with outcome on programmed death 1 (PD1) therapy in advanced renal cell cancer (RCC). J Clin Oncol. 2018 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.4518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalbasi A, Ribas A. Tumour-intrinsic resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:25–39. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0218-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Restifo NP, Esquivel F, Kawakami Y, Yewdell JW, Mulé JJ, et al. Identification of human cancers deficient in antigen processing. J Exp Med. 1993;177:265–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Platanias LC. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:375–86. doi: 10.1038/nri1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zaretsky JM, Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, Escuin-Ordinas H, Hugo W, et al. Mutations associated with acquired resistance to PD-1 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:819–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1604958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, Moreno BH, Saco J, Escuin-Ordinas H, et al. Interferon receptor signaling pathways regulating PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression. Cell Rep. 2017;19:1189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bui JD, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunosurveillance, immunoediting and inflammation: independent or interdependent processes? Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:203–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic β-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2015;523:231–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sweis RF, Spranger S, Bao R, Paner GP, Stadler WM, et al. Molecular drivers of the non-T-cell-inflamed tumor microenvironment in urothelial bladder cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:563–8. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seiwert TY, Zuo Z, Keck MK, Khattri A, Pedamallu CS, et al. Integrative and comparative genomic analysis of HPV-positive and HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:632–41. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jiménez-Sánchez A, Memon D, Pourpe S, Veeraraghavan H, Li Y, et al. Heterogeneous tumor-immune microenvironments among differentially growing metastases in an ovarian cancer patient. Cell. 2017;170:927–38.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao F, Xiao C, Evans KS, Theivanthiran T, DeVito N, et al. Paracrine Wnt5a-β-catenin signaling triggers a metabolic program that drives dendritic cell tolerization. Immunity. 2018;48:147–60.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhan T, Rindtorff N, Boutros M. Wnt signaling in cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36:1461–73. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boni A, Cogdill AP, Dang P, Udayakumar D, Njauw C, et al. Selective BRAFV600E inhibition enhances T-cell recognition of melanoma without affecting lymphocyte function. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5213–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ricketts CJ, De Cubas AA, Fan H, Smith CC, Lang M, et al. The cancer genome atlas comprehensive molecular characterization of renal cell carcinoma. Cell Rep. 2018;23:313–26.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peng W, Chen JQ, Liu C, Malu S, Creasy C, et al. Loss of PTEN promotes resistance to T cell-mediated immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:202–16. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goel S, DeCristo MJ, Watt AC, BrinJones H, Sceneay J, et al. CDK4/6 inhibition triggers anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2017;548:471–5. doi: 10.1038/nature23465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jerby-Arnon L, Shah P, Cuoco MS, Rodman C, Su MJ, et al. A cancer cell program promotes T cell exclusion and resistance to checkpoint blockade. Cell. 2018;175:984–97.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deng J, Wang ES, Jenkins RW, Li S, Dries R, et al. CDK4/6 inhibition augments antitumor immunity by enhancing T-cell activation. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:216–33. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang X, Zhang H, Chen X. Drug resistance and combating drug resistance in cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2019;2:141–60. doi: 10.20517/cdr.2019.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sade-Feldman M, Jiao YJ, Chen JH, Rooney MS, Barzily-Rokni M, et al. Resistance to checkpoint blockade therapy through inactivation of antigen presentation. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1136. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01062-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fridman WH, Pagès F, Sautès-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nrc3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Becht E, Giraldo NA, Lacroix L, Buttard B, Elarouci N, et al. Estimating the population abundance of tissue-infiltrating immune and stromal cell populations using gene expression. Genome Biol. 2016;17:218. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1070-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Giraldo NA, Becht E, Pagès F, Skliris G, Verkarre V, et al. Orchestration and prognostic significance of immune checkpoints in the microenvironment of primary and metastatic renal cell cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3031–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vano Y, Rioux-Leclercq N, Dalban C, Sautès-Fridman C, Bougoüin A, Chaput N, et al. 909PDNIVOREN GETUG-AFU 26 translational study: CD8 infiltration and PD-L1 expression are associated with outcome in patients (pts) with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (mccRCC) treated with nivolumab (N). Ann Oncol [Internet]. 2019 Oct 1 [cited 2019 Nov 2];30(mdz249.008). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz249.008 [Last accessed on 29 Feb 2020]

- 64.Giraldo NA, Becht E, Vano Y, Petitprez F, Lacroix L, et al. Tumor-infiltrating and peripheral blood T-cell immunophenotypes predict early relapse in localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:4416–28. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang S, Zhang E, Long J, Hu Z, Peng J, et al. Immune infiltration in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:1564–72. doi: 10.1111/cas.13996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Komohara Y, Hasita H, Ohnishi K, Fujiwara Y, Suzu S, et al. Macrophage infiltration and its prognostic relevance in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1424–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chanmee T, Ontong P, Konno K, Itano N. Tumor-associated macrophages as major players in the tumor microenvironment. Cancers. 2014;6:1670–90. doi: 10.3390/cancers6031670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mier JW. The tumor microenvironment in renal cell cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2019;31:194–9. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Santoni M, Massari F, Amantini C, Nabissi M, Maines F, et al. Emerging role of tumor-associated macrophages as therapeutic targets in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62:1757–68. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1487-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vano YA, Rioux-Leclercq N, Dalban C, Sautes-Fridman C, Bougoüin A, et al. NIVOREN GETUG-AFU 26 translational study: association of PD-1, AXL, and PBRM-1 with outcomes in patients (pts) with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (mccRCC) treated with nivolumab (N). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:618. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.6_suppl.618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sarvaria A, Madrigal JA, Saudemont A. B cell regulation in cancer and anti-tumor immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017;14:662–74. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rosser EC, Mauri C. Regulatory B cells: origin, phenotype, and function. Immunity. 2015;42:607–12. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Helmink BA, Reddy SM, Gao J, Zhang S, Basar R, et al. B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures promote immunotherapy response. Nature. 2020;577:549–55. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1922-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Petitprez F, de Reyniès A, Keung EZ, Chen TWW, Sun CM, et al. B cells are associated with survival and immunotherapy response in sarcoma. Nature. 2020;577:556–60. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1906-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fridman WH, Zitvogel L, Sautès-Fridman C, Kroemer G. The immune contexture in cancer prognosis and treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:717–34. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Finkin S, Yuan D, Stein I, Taniguchi K, Weber A, et al. Ectopic lymphoid structures function as microniches for tumor progenitor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:1235–44. doi: 10.1038/ni.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stubbs M, McSheehy PM, Griffiths JR, Bashford CL. Causes and consequences of tumour acidity and implications for treatment. Mol Med Today. 2000;6:15–9. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(99)01615-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sormendi S, Wielockx B. Hypoxia pathway proteins as central mediators of metabolism in the tumor cells and their microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2018;9:40. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Khan KA, Kerbel RS. Improving immunotherapy outcomes with anti-angiogenic treatments and vice versa. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:310–24. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Garcia-Lora A, Algarra I, Garrido F. MHC class I antigens, immune surveillance, and tumor immune escape. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195:346–55. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tatli Dogan H, Kiran M, Bilgin B, Kiliçarslan A, Sendur MAN, et al. Prognostic significance of the programmed death ligand 1 expression in clear cell renal cell carcinoma and correlation with the tumor microenvironment and hypoxia-inducible factor expression. Diagn Pathol. 2018;13:60. doi: 10.1186/s13000-018-0742-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang J, Shi Z, Xu X, Yu Z, Mi J. The influence of microenvironment on tumor immunotherapy. FEBS J. 2019;286:4160–75. doi: 10.1111/febs.15028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Romero-Garcia S, Moreno-Altamirano MMB, Prado-Garcia H, Sánchez-García FJ. Lactate contribution to the tumor microenvironment: mechanisms, effects on immune cells and therapeutic relevance. Front Immunol. 2016;7:52. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pan D, Kobayashi A, Jiang P, Ferrari de Andrade L, Tay RE, et al. A major chromatin regulator determines resistance of tumor cells to T cell-mediated killing. Science. 2018;359:770–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aao1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Varela I, Tarpey P, Raine K, Huang D, Ong CK, et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of the SWI/SNF complex gene PBRM1 in renal carcinoma. Nature. 2011;469:539–42. doi: 10.1038/nature09639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Miao D, Margolis CA, Gao W, Voss MH, Li W, et al. Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint therapies in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Science. 2018;359:801–6. doi: 10.1126/science.aan5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Braun DA, Ishii Y, Walsh AM, Van Allen EM, Wu CJ, et al. Clinical validation of PBRM1 alterations as a marker of immune checkpoint inhibitor response in renal cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:1631–3. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McDermott DF, Huseni MA, Atkins MB, Motzer RJ, Rini BI, et al. Clinical activity and molecular correlates of response to atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab versus sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Nat Med. 2018;24:749–57. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0053-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pignon JC, Jegede O, Shukla SA, Braun DA, Horak CE, et al. irRECIST for the evaluation of candidate biomarkers of response to nivolumab in metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: analysis of a phase II prospective clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:2174–84. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Seeber A, Klinglmair G, Fritz J, Steinkohl F, Zimmer KC, et al. High IDO-1 expression in tumor endothelial cells is associated with response to immunotherapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:1583–91. doi: 10.1111/cas.13560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mitchell TC, Hamid O, Smith DC, Bauer TM, Wasser JS, et al. Epacadostat plus pembrolizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors: phase I results from a multicenter, open-label phase I/II trial (ECHO-202/KEYNOTE-037). J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:3223–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.9602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Long GV, Dummer R, Hamid O, Gajewski TF, Caglevic C, et al. Epacadostat plus pembrolizumab versus placebo plus pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma (ECHO-301/KEYNOTE-252): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1083–97. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cannarile MA, Weisser M, Jacob W, Jegg AM, Ries CH, et al. Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:53. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0257-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Heidegger I, Pircher A, Pichler R. Targeting the tumor microenvironment in renal cell cancer biology and therapy. Front Oncol. 2019;9 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Corrales L, Glickman LH, McWhirter SM, Kanne DB, Sivick KE, et al. Direct activation of STING in the tumor microenvironment leads to potent and systemic tumor regression and immunity. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1018–30. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Poeck H, Besch R, Maihoefer C, Renn M, Tormo D, et al. 5’-Triphosphate-siRNA: turning gene silencing and Rig-I activation against melanoma. Nat Med. 2008;14:1256–63. doi: 10.1038/nm.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Granier C, Dariane C, Combe P, Verkarre V, Urien S, et al. Tim-3 expression on tumor-infiltrating PD-1+CD8+ T cells correlates with poor clinical outcome in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2017;77:1075–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.He Y, Cao J, Zhao C, Li X, Zhou C, et al. TIM-3, a promising target for cancer immunotherapy. OncoTargets Ther. 2018;11:7005–9. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S170385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Long L, Zhang X, Chen F, Pan Q, Phiphatwatchara P, et al. The promising immune checkpoint LAG-3: from tumor microenvironment to cancer immunotherapy. Genes Cancer. 2018;9:176–89. doi: 10.18632/genesandcancer.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Brignone C, Escudier B, Grygar C, Marcu M, Triebel F. A phase I pharmacokinetic and biological correlative study of IMP321, a novel MHC class II agonist, in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6225–31. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shen X, Zhao B. Efficacy of PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors and PD-L1 expression status in cancer: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;362:k3529. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rini BI, Powles T, Atkins MB, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. IMmotion151 Study Group Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sunitinib in patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma (IMmotion151): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2019;393:2404–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30723-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]