Introduction

Interest in prophylactic surgical intervention to decrease the rate of breast cancer related lymphedema is growing. In Boccardo et al. introduced LVB at the time of axillary lymph node dissection (ALND). Their initial results demon- strated statistically significant differences in lymphedema development in the control arm (30.43%) compared to the treatment arm (4.34%).1,2 A 4 year follow up by the same group demonstrated a 4% incidence of lymphedema after ILR.3 Subsequent reports of ILR outcomes from other institu- tions show similarly promising results. However, these stud- ies have low numbers of patients, ranging from 8 to 35, and short follow up, ranging on average from 6 to 15 months.4 The body of literature would benefit from additional publi- cations on this topic with follow up of at least one year. Our study aims to add to the limited available data regarding ILR by describing our experience with our previously reported ILR technique.5

Methods

A retrospective review was conducted on all patients who underwent unilateral ILR after ALND for treatment of breast cancer, from May 2019 to March 2020. Patient demograph- ics, details of the ALND and ILR, treatments for breast can- cer, as well as the postoperative course were recorded. Pa- tients who experienced post-operative swelling or subjec- tive lymphedema symptoms were referred to lymphedema therapy. Arm circumference measurements were taken at every 4 cm along the limb and used to calculate limb volume using the truncated cone formula. Measurements were done in both limbs. Patients who were found to have a greater than 10% volume difference compared to the contralateral arm were diagnosed with lymphedema.

ILR was performed as previously described by one of three microsurgeons (MC, JHD, BM) following completion of the ALND by the breast surgeon.5 Briefly, ALND was per- formed ether through the mastectomy incision or through a separate axillary incision. Blue dye, indocyanine green, and/or fluorescein was injected intradermally to the hand and/or upper inner arm to visualize transected lymphatic channels. In most cases, the thoracoepigastric vein was dis- sected during the ALND and preserved by the breast sur- geons. In some cases, other nearby veins were used. If mul- tiple lymphatic channels were identified, the largest chan- nel(s) were targeted first. Transected lymphatic channels were anastomosed to the vein with 9–0 or 10–0 nylon using an intussusception technique. Patency of the anastomosis was verified by flow of lymph/dye through the anastomosis into the vein (Figures 1, 2). Transected lymphatic channels not bypassed were clipped.

Figure 1.

Visualization of lymph fluid flowing from lymphatic channel into the vein with no magnification/filter. Arrow de- notes anastomosis site with the lymphatic channel to the left and the vein to the right.

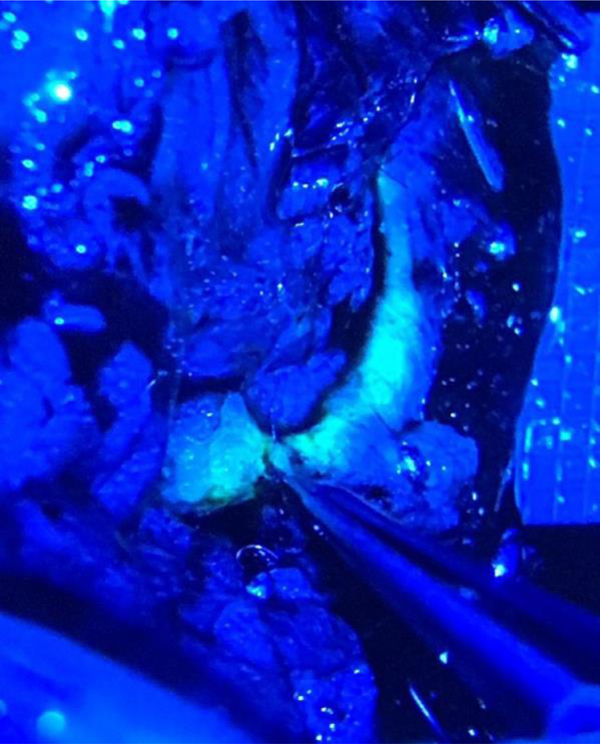

Figure 2.

Visualization of fluorescein dye flowing from lym- phatic channel into the vein under microscope magnification and low fluorescence filter. Forceps pointing to anastomosis site. Lymphatic channel to the left, vein to the right.

Results

A total of 30 patients underwent ILR after ALND during the study time period. Average age was 49.9 (±10.6), average BMI was 26.3 (±6.4). Most patients received post-operative radiation to the chest wall (n 28, 93%) and many received regional lymph node radiation (n 15, 50%), neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n 17, 57%), and adjuvant chemotherapy (n 16, 53%).

This study is limited by its retrospective nature, small sample size, and lack of base-line arm measurements. Fur- ther, documentation of current compression therapy was variable and lacking. This area of innovation would greatly benefit from an appropriately powered, randomized con- trolled trial with baseline measurements and a longer-term follow up (>2 years). We are currently enrolling patients to such a trial at our institution. Results are pending trial com- pletion.

There were 1.9 (1.0) lymphovenous bypasses per- formed per patient after ALND. One patient’s surgical drain fell out on post-operative day 2 and subsequently developed a seroma. This was aspirated in clinic. No other complica- tions were noted.

Four patients were excluded from final analysis. One patient had baseline lymphedema with metastatic disease and passed away at 14 months post-operation. One patient passed away from metastatic disease at 5 months post- operation. One patient suffered a catheter related upper extremity DVT. One patient followed-up with outside phys- ical therapy and therefore measurements could not be ob- tained. Average length of follow-up the remaining 26 pa- tients was 17.4 (3.9) months. Two patients had developed lymphedema (7.7%) at most recent follow-up. The institu- tional rate of lymphedema at 18-months follow-up after ALND during a similar time frame was 17.6% (95% CI 12.4 – 24.5%).6

Discussion

This report adds to the body of literature showing promising results of ILR in decreasing the incidence of lymphedema. With an average follow up time of a year and a half, only two patients (7.7%) developed lymphedema. Published lit- erature regarding ILR is promising but limited. A system- atic review by Jorgensen et al. in 2018 identified 12 studies reporting outcomes of ILR and just 4 of these studies in- cluded a control group.4 All studies including in the system- atic review were limited by small sample sizes and lack of long-term follow up. However, they did find patients treated with ILR had a significant reduction in lymphedema inci- dence (RR: 0.33, 95%CI: 0.19 to 0.56) compared to patients receiving no prophylactic treatment (p<0.001).

Conclusions

ILR is a safe and effective procedure for reducing rates of lymphedema following ALND. Additional well-designed stud- ies are needed to confirm the benefit of ILR.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Can- cer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748, which supports Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s research infras- tructure.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure Statement

Joseph H. Dayan, M.D. is a paid consultant for the Stryker Corporation.

Ethical Approval

This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

References

- 1.Boccardo FM, Casabona F, Friedman D, et al. Surgical prevention of arm lymphedema after breast cancer treatment. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18(9):2500–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boccardo F, Casabona F, De Cian F, et al. Lymphedema microsur- gical preventive healing approach: a new technique for primary prevention of arm lymphedema after mastectomy. Ann Surg On- col 2009;16(3):703–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boccardo F, Casabona F, De Cian F, et al. Lymphatic microsur- gical preventing healing approach (LYMPHA) for primary surgical prevention of breast cancer-related lymphedema: over 4 years follow-up. Microsurgery 2014;34(6):421–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jørgensen MG, Toyserkani NM, Sørensen JA. The effect of prophylactic lymphovenous anastomosis and shunts for preventing cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Microsurgery 2018;38(5):576–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coriddi M, Mehrara B, Skoracki R, Singhal D, Dayan JH. Im- mediate lymphatic reconstruction: technical points and lit- erature review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2021;9(2): e3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, Montagna G, Sevilimedu V, Abbate KT, Charyn J, Mehrara B, BarrioA Morrow Mm. Longitudinal prospective eval- uation of quality of life after axillary lymph node dissection. Soc Surg Oncol Annu Meet 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]