Abstract

Background:

Camouflaging involves concealing an autistic identity, for example, by adopting nonautistic behaviors in social contexts. We currently know little about the relationship between autistic identity and camouflaging. Furthermore, other variables may mediate the relationship between camouflaging and identity, and this study examined whether disclosure (being openly autistic) might mediate the relationship. We predicted that fewer camouflaging behaviors would be associated with higher autistic identity when an individual is more open about being autistic.

Methods:

One hundred eighty autistic adults (52% female, 42% male, 5% other gender identities, and 1% preferred not to say) took part in the study. They completed an online survey with measures of camouflaging, autistic identity, and disclosure of autistic status.

Results:

We found a significant mediation effect such that autistic identity had an indirect negative effect on camouflaging mediated via disclosure. In other words, higher autistic identity linked to more disclosure, which in turn linked to fewer camouflaging behaviors. However, there was evidence for competitive mediation, such that the direct effect (the relationship between identity and camouflaging ignoring disclosure) was significant, with higher autistic identity linking directly to more camouflaging.

Conclusions:

The initial hypothesis was confirmed, with higher autistic identity linked to less camouflaging via disclosure. This finding indicates that camouflaging can reduce when there is high autistic identification, and someone has openly disclosed that they are autistic to others. However, the direct effect between identity and camouflaging suggests that there may be conflicts for someone who identifies strongly with being autistic but continues to camouflage. Other variables may play a role in the relationship between identity and camouflaging, such as fear of discrimination, self-awareness, timing of diagnosis, age, ethnicity, or gender. The findings indicate the importance of safe nondiscriminatory environments where individuals can disclose and express their autistic identity, which may in turn reduce camouflaging.

Lay summary

Why was this study done?

Camouflaging involves hiding or masking being autistic or using strategies to appear as though nonautistic. Past research has found that camouflaging relates to poorer mental health. Given this, we must understand ways to reduce camouflaging. In this study, we looked at the links between camouflaging, autistic identity (a sense of affiliation with the autistic community), and disclosure (being openly autistic). We know from other research that identifying strongly with the autistic community may protect against mental health difficulties, so we wanted to explore the role autistic identity might play in camouflaging.

What was the purpose of this study?

The purpose was to understand the relationships between camouflaging, autistic identity, and disclosure. We considered disclosure because someone could have a strong sense of autistic identity but might not be open about this to others. We tested the idea that someone with a strong autistic identity might be more openly autistic, and this then has a knock-on effect that links to less camouflaging.

What did the researchers do?

One hundred and eighty autistic adults completed an online survey. They answered questions about camouflaging, autistic identity, and disclosure. They also answered questions about who they were (e.g., age, gender) and autistic characteristics. We analyzed everyone's answers using an analysis called “mediation analysis.” This analysis enables us to test how disclosure influences any association between camouflaging and identity.

What were the results of the study?

We found that higher autistic identity related to more disclosure, and this then linked to less camouflaging, that is, strong autistic identity can relate to less camouflaging when someone is more openly autistic. We also found that ignoring disclosure, autistic identity directly influenced camouflaging in the opposite way, that is, higher autistic identity contributed to more camouflaging if we do not take disclosure into account. This is known as “competitive mediation” and suggests a complex picture when it comes to identity, disclosure, and camouflaging.

What do these findings add to what was already known?

As far as we know, no one has looked at these relationships before. We therefore add to camouflaging research and show that camouflaging might be reduced if autistic people identify strongly and they are able to be openly autistic.

What are potential weaknesses in the study?

Participants were recruited online, which means the sample may be biased, and the findings will not apply to all autistic people. We measured disclosure using one question, which could be a problem because individuals might have interpreted the question in different ways. The “competitive mediation” suggests that there are other variables impacting on relationship between identity and camouflaging, which we did not capture.

How will these findings help autistic adults now or in the future?

This study indicates that strong autistic identity and being openly autistic could reduce camouflaging, which we know to have negative effects on mental health. However, to enable disclosure, these findings demonstrate the need for safe spaces where autistic people can explore their identity and be openly autistic, without fear of discrimination.

Keywords: camouflaging, autistic identity, disclosure, autism acceptance

Introduction

Camouflaging involves masking autistic characteristics and using strategies to appear nonautistic.1,2 Many autistic people report high levels of camouflaging1 and camouflaging in some situations but not in others.3 Previous research has established that camouflaging is associated with poorer mental health, with greater camouflaging associated with depression, anxiety, social anxiety, stress, and suicidal thoughts.1,3–7 Additionally, since camouflaging involves hiding autistic characteristics, it impacts on sense of self.1 For example, late-diagnosed autistic women describe how “acting neurotypical” makes them unsure of their identity.8

While camouflaging is thought to relate to personal identity (“what makes me uniquely ‘me’?”), autistic social identity (“am I like other autistic people and do I feel part of the autistic community?”9) may protect against camouflaging. For nonautistic people, research has shown that identifying with a social group or community can be beneficial for well-being.10,11 Researchers have also noted this link for autistic people, finding that identifying with the autistic community may benefit self-esteem and protect against poor mental health.12 Based on this research, the current study also focuses on autistic social identity, in terms of affiliation with the autistic community,12 and further tests its relationship to camouflaging—to examine whether autistic social identity has any protective potential when it comes to camouflaging. To the best of our knowledge, this relationship has not yet been explored quantitatively.

However, any relationship between autistic identity and camouflaging may depend on other variables. In particular, after developing affiliation with the autistic community, some may still decide not to share or disclose that they are autistic—for example, if they believe society is unaccepting5 or if they have experienced discrimination when openly autistic.3 Therefore, disclosure (being openly autistic) may mediate any relationship between autistic identity and camouflaging. Past research in the disability literature has shown that greater disability disclosure relates to higher life satisfaction, less fear, anxiety, and self-doubt.13–17 Theoretically, it is possible that regardless of identification, without disclosure, camouflaging may persist. Given the effects of camouflaging on mental health,4 it is important we understand conditions wherein camouflaging might lessen, and if disclosure is one variable that may mediate any relationship between autistic identity and camouflaging.

The current study therefore aimed to understand the relationships between camouflaging, autistic identity, and disclosure. Based on the literature discussed, we hypothesized that higher autistic identity would relate to more disclosure, which would subsequently relate to less camouflaging.

Methods

Participants

The sample contained 180 autistic adults (see Table 1 for full demographic information, including self-reported diagnosis, gender, age, ethnicity, education, and country). The sample was mostly White, Western, and educated to degree level. All participants, including those who self-identified, scored above the Ritvo Autism and Asperger's Diagnostic Scale-14 (RAADS-14)18 cutoff score of 14 (mean = 32.11 [standard deviation {SD} = 6.34]).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Sample Characteristics (n = 180)

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Diagnosisa | |

| Autism spectrum condition | 54.4% |

| Asperger's syndrome | 60.6% |

| PDD-NOS | 1.7% |

| Seeking diagnosis | 12.2% |

| Gender | |

| Female | 51.7% |

| Male | 42.2% |

| Other gender identities | 5.0% |

| Preferred not to disclose | 1.1% |

| Mean age, years | 33.89 (SD = 11.21) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White—British | 58.9% |

| White—Other background | 26.7% |

| Mixed or multiethnic | 8.3% |

| Asian or British Asian | 3.3% |

| Other ethnicities | 1.7% |

| Preferred not to disclose | 1.1% |

| Education | |

| Undergraduate degree | 32.8% |

| Postgraduate degree | 23.9% |

| High school qualifications | 23.4% |

| Other qualifications | 10.0% |

| No qualifications | 6.1% |

| Preferred not to disclose | 3.9% |

| Country | |

| United Kingdom | 51.1% |

| North America | 29.4% |

| Other European countries | 12.0% |

| Australia | 3.9% |

| Hong Kong | 0.6% |

| South Africa | 0.6% |

| Preferred not to disclose | 2.8% |

Percentages total over 100% as participants could select multiple options, due to changes in the diagnosis of autism spectrum conditions. Historic diagnoses of Asperger's syndrome reported.

PDD-NOS, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified; SD, standard deviation.

We recruited participants through social media (e.g., Facebook groups, Twitter, Reddit), autism charities and organizations, and contacts via the university Disability Service, using adverts and e-mails including a link to the online survey. Participants had the option to participate in a prize draw as thanks for their time. After reading the information sheet, all participants provided informed consent, with ethical approval obtained from Royal Holloway. We collected the data between November 2017 and February 2018.

Materials

The survey was initially reviewed by two autistic people who offered feedback on the questions and validity of the topic for the autistic community. Camouflaging was measured using the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CATQ, Cronbach's α = 0.89),4 which includes 25 items rated on a 7-point scale (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”; e.g., “In social situations, I feel like I'm ‘performing’ rather than being myself”) giving a total summed score between 25 and 175, with higher scores indicating greater camouflaging. For autistic identity, participants rated five items adapted from the Disability Identification Scale13 (which measures social identification with a group9) on the same 7-point scale (e.g., “Being a member of the autism community is central to my identity,” α = 0.88), giving a total possible score between 5 and 35, with higher scores indicating more identification with the autistic community. Disclosure was measured with one item adapted from the disability literature14,15: “I am generally open about acknowledging and discussing my status as an autistic person,” rated on a 5-point scale (“does not describe me” to “describes me extremely well”), giving a total possible score between 1 and 5, with higher scores indicating greater disclosure.

Procedure

We used “Qualtrics” to display the survey online. Participants completed questions regarding autistic identity first, then disclosure and CATQ. Finally, they reported diagnoses and completed the RAADS-14 and demographic questions.

Design and data analysis

This study had a cross-sectional design, using an online survey to reach participants and enable initial examination of the hypothesis. We used the PROCESS (version 3.4) add-on for SPSS19 for mediation analysis, with the bootstrapping method for 1000 samples.20 All assumptions for the model were met, including normal distribution of the data and no significant outliers.

Results

The mean camouflaging score was 116.12 (SD = 20.48), the mean autistic identity score was 23.01 (SD = 7.41), and the mean disclosure score was 2.84 (SD = 1.26).

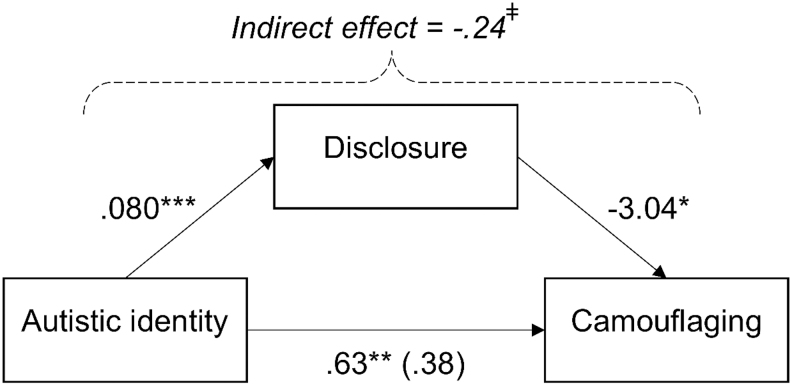

The path between identity and disclosure was significant [b = 0.080, t(178) = 7.11, p < 0.001], as was the path between disclosure and camouflaging [b = −3.04, t(177) = −2.34, p = 0.026]. The direct effect (the unmediated effect of identity on camouflaging, with disclosure held constant) was significant [b = 0.63, t(177) = 2.73, p = 0.007]. The total effect (the sum of all direct and indirect effects) was not significant [b = 0.38, t(178) = 1.87, p = 0.063]. There was a significant negative indirect effect (a × b = −0.24), with a 95% confidence interval not including zero (−0.47 to −0.060): autistic identity had an indirect negative effect on camouflaging through greater disclosure (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Mediation diagram between autistic identity, disclosure, and camouflaging. ***p < 0.001, **p = 0.007, *p = 0.026. ǂSignificant indirect effect indicated as the 95% confidence intervals does not cross zero (−0.47 to −0.060).

Discussion

Our hypothesis was met: higher autistic identity linked to fewer camouflaging behaviors via being openly autistic. However, there was competitive and partial mediation,21 with a positive direct relationship (ignoring disclosure) between autistic identity and camouflaging, with higher identity linked to more camouflaging. This competitive mediation suggests that other variables likely affect the relationship between identity and camouflaging.21

These findings may indicate that camouflaging could reduce via autistic identification leading to greater disclosure. The decision to disclose involves evaluating who, what, when, and how much to disclose.17 If nondisclosure is the safest option, camouflaging persists, maintaining a nonautistic social presence (even if disclosure could be beneficial22). The competitive mediation may stem from fear of stigma, despite autistic identification.3,23 Trapped in an internal conflict between high autistic identity and fear of discrimination, autistic people may feel resigned to camouflaging. These findings highlight the difficult process for autistic people in terms of weighing up the costs and benefits of disclosing or camouflaging in different contexts.24

Past research discusses the impact of camouflaging on personal identity.1,8 This study adds to the literature by highlighting the complex relationship between autistic identity, disclosure, and camouflaging. Our findings suggest that supporting autistic identity and disclosure may be one means of reducing camouflaging. These findings imply the importance of a diversity-valuing society,5 which supports autistic identity exploration25 while ensuring safe spaces exist to do so. Future researchers must test the development of safe spaces,26 and policymakers should ensure that there is funding for these spaces, as well as examining other ways to best support autistic people who find camouflaging to be detrimental to their well-being.

There are several limitations: the competitive mediation suggests that other unmeasured variables may be influencing the relationships in the model.21 Potential variables could include self-awareness (including of autistic characteristics), social anxiety, timing of diagnosis, or culture. We did not measure these, but future research could add further insight by considering these variables. The sample is biased since it is self-selected, recruited online, relies on self-report, and may consist of individuals with strong autistic identities or who identified as being “camouflagers.” Furthermore, we measured disclosure with one item, which may lack nuance. The model also did not include demographic variables such as gender, age, education level, or ethnicity. These variables could influence the relationships in the model—for example, there may be gender differences in camouflaging27 and it is likely that disclosure decisions could also be influenced by gender. For example, autistic women may have to make decisions (in terms of identity, disclosure, and camouflaging), which include reflecting on one's positionality specifically as an autistic woman within different contexts.3,8 Accordingly, research should consider how the intersection of different identities (not limited to gender, but also including, for example, ethnicity or culture) may relate to camouflaging, autistic identity, and disclosure. Future research should endeavor to examine these different variables with large sample sizes as well as recruiting more diverse offline samples.

We hope the current findings stimulate further research into these variables, with a goal of supporting autistic people to “take the mask off.”26 Overall, the findings suggest that autistic people need discrimination-free spaces and societal change to disclose and explore autistic identity: doing so may help to reduce camouflaging.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the autistic people who kindly reviewed the original proposal for this work. Thank you to all the participants for their time.

Authorship Confirmation Statement

E.C. and Z.T.-W. designed the study together. Z.T.-W. oversaw data collection. E.C. carried out the data analyses. Both authors contributed toward the article draft. Both authors have reviewed and approved the article before submission. This article has been submitted solely to this journal and is not published, in press, or submitted elsewhere.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. Hull L, Petrides KV, Allison C, et al. “Putting on my best normal”: Social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(8):2519–2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Livingston LA, Shah P, Milner V, Happé F. Quantifying compensatory strategies in adults with and without diagnosed autism. Mol Autism. 2020;11(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cage E, Troxell-Whitman Z. Understanding the reasons, contexts and costs of camouflaging for autistic adults. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(5):1899–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hull L, Mandy W, Lai MC, et al. Development and validation of the camouflaging autistic traits questionnaire (CAT-Q). J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(3):819–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cage E, Di Monaco J, Newell V. Experiences of autism acceptance and mental health in autistic adults. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(2):473–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cassidy SA, Gould K, Townsend E, Pelton M, Robertson AE, Rodgers J. Is camouflaging autistic traits associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviours? Expanding the interpersonal psychological theory of suicide in an undergraduate student sample. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;9:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beck JS, Lundwall RA, Gabrielsen T, Cox JC, South M. Looking good but feeling bad:“Camouflaging” behaviors and mental health in women with autistic traits. Autism. 2020;24(4):809–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bargiela S, Steward R, Mandy W. The experiences of late-diagnosed women with autism spectrum conditions: An investigation of the female autism phenotype. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(10):3281–3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hogg MA, Abrams D. Social Identifications: A Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations and Group Processes. London: Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stets JE, Burke PJ. Identity theory and social identity theory. Soc Psychol Q. 2000;63:224–237. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jetten J, Haslam C, Haslam SA, Dingle G, Jones JM. How groups affect our health and well-being: The path from theory to policy. Soc Issues Policy Rev. 2014;8(1):103–130. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cooper K, Smith LG, Russell A. Social identity, self-esteem, and mental health in autism. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2017;47(7):844–854. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nario-Redmond MR, Oleson KC. disability group identification and disability-rights advocacy: Contingencies among emerging and other adults. Emerg Adulthood. 2016;4(3):207–218. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Troxell-Whitman Z. Motivated Disclosure Patterns: Disability Identity Management in the Higher Education Environment. [Dissertation]. Portland, OR: Reed College; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chaudoir SR, Fisher JD. The disclosure processes model: Understanding disclosure decision making and postdisclosure outcomes among people living with a concealable stigmatized identity. Psychol Bull. 2010;136(2):236–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chaudoir SR, Quinn DM. Revealing concealable stigmatized identities: The impact of disclosure motivations and positive first-disclosure experiences on fear of disclosure and well-being. J Soc Issues. 2010;66(3):570–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trammell J. Red-shirting college students with disabilities. Learn Assist Rev. 2009;14(2):21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eriksson JM, Andersen LM, Bejerot S. RAADS-14 Screen: Validity of a screening tool for autism spectrum disorder in an adult psychiatric population. Mol Autism. 2013;4(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (2nd Edition). New York: Guilford Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(4):422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhao X, Lynch JG Jr., Chen Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J Consum Res. 2010;37(2):197–206. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sasson NJ, Morrison KE. First impressions of adults with autism improve with diagnostic disclosure and increased autism knowledge of peers. Autism. 2019;23(1):50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. London, United Kingdom: Penguin Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schneid I, Raz AE. The mask of autism: Social camouflaging and impression management as coping/normalization from the perspectives of autistic adults. Soc Sci Med. 2020;248:112826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cresswell L, Cage E. ‘Who am I?’: An exploratory study of the relationships between identity, acculturation and mental health in autistic adolescents. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(7):2901–2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mandy W. Social camouflaging in autism: Is it time to lose the mask? Autism. 2019;23(8):1879–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hull L, Lai MC, Baron-Cohen S, et al. Gender differences in self-reported camouflaging in autistic and non-autistic adults. Autism. 2020;24(2):352–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]