Abstract

Background:

Although previous studies have measured attitudes about autism to understand ways to ameliorate stigmatized beliefs, nonautistic individuals' acceptance of autism is still not well understood. This study aimed to develop and pilot test the Autism Attitude Acceptance Scale (AAAS), a self-report instrument that measures nonautistic adults' autism acceptance based on the neurodiversity framework, and examine the associations between autism acceptance and purported variables (disability-related experience/awareness variables and demographic characteristics).

Methods:

The author piloted the AAAS with 122 nonautistic adults. Principal component analysis and reliability analysis were used to examine the factor structure and psychometric properties of the AAAS. The associations between the AAAS and autism knowledge, the quantity and quality of previous contact, neurodiversity awareness, and demographic variables were examined using Pearson's r correlations, t-tests, and analyses of variance.

Results:

The author constructed two subscales of the AAAS, General Acceptance (GA) and Attitudes toward Treating Autistic Behaviors (ATAB). The GA measures the acceptance of autism as a unique way of being, willingness to provide support to autistic individuals, and feeling comfortable while interacting with them. The ATAB measures how strongly a person believes that receiving treatments to reduce autistic symptoms will or will not benefit autistic individuals. The GA was associated with autism knowledge, quality and quantity of previous contact with autistic individuals, neurodiversity awareness, gender, ethnicity, and education level of participants. The ATAB was significantly associated with autism knowledge and quality and quantity of previous contact; the ATAB did not have any significant associations with neurodiversity awareness and demographic variables.

Conclusions:

The AAAS, which validly and reliably measures nonautistic individuals' autism acceptance, identified the subgroups with low autism acceptance. This study calls for further examination of the underlying mechanism of autism acceptance and neurodiversity framework to restructure nonautistic individuals' attitudes about autism.

Lay summary

Why was this study done?

There are many studies that measure how nonautistic individuals think about autism. These studies tried to identify subgroups of people with particularly negative attitudes toward autism and improve those attitudes. Autistic advocates are increasingly noting the importance of autism acceptance, which asks people to accept autistic individuals for who they are as they are. Autism acceptance draws from the neurodiversity framework, which considers autism as a part of natural diversity and rejects the idea that autistic needs to be fixed. However, there is currently no tool that measures nonautistic individuals' autism acceptance.

What was the purpose of this study?

The purpose of this study is to develop the Autism Attitude Acceptance Scale (AAAS), which measures nonautistic adults' acceptance of autistic individuals.

What did the researchers do?

The author developed an autism acceptance survey that draws on a neurodiversity framework, and 122 nonautistic adults completed the instrument in an online survey along with the existing attitude scales. A series of statistical analyses were conducted to examine if the AAAS can be used to measure autism acceptance.

What were the results of the study?

The AAAS consists of two subscales: General Acceptance (GA), which measures how much a person accepts autism as a unique way of beings and feels more comfortable to provide support to and have a personal relationship with an autistic person, and Attitudes toward Treating Autistic Behavior (ATAB), which measures how much a person agrees that receiving treatments to reduce autistic symptoms will benefit autistic individuals. Accurate knowledge about autism, high quality of previous contact, and more frequent contact were significantly associated with higher scores in both GA and ATAB subscales. Being white, female, and aware of the neurodiversity framework and having a higher level of education were positively associated only with the GA, but not with ATAB.

What do these findings add to what was already known?

This is the first study to conceptualize and measure autism acceptance of nonautistic individuals as a distinct construct. How much a nonautistic person thinks favorably of autistic individuals is different from how he/she thinks about receiving treatments to reduce autistic symptoms. Increasing the quality and quantity of contact with autistic individuals and knowledge about autism may be helpful in promoting autism acceptance. Demographic variables may account for only specific types of attitudes about autism.

What are potential weaknesses in the study?

As a pilot study, this study included a small number of participants, and participants who participated were those could be reached or contacted easily. Also, participants may act differently in real life than how they responded on the survey.

How will these findings help autistic adults now or in the future?

The AAAS can be used with existing tools to inform ways to promote autism attitudes and find ways to appreciate autistic differences.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, attitudes, acceptance, scale development, neurodiversity

Introduction

The difficulties experienced by autistic individuals can be conceptualized through the social-relational model of disability, which posits that inherent personal factors and imposed social and cultural barriers together contribute to disabilities.1 That is, the attitudes of nonautistic individuals in the social environment need to be considered and adjusted to better support autistic individuals,2,3 rather than focusing on eliminating their autistic symptoms. While previous studies have examined nonautistic individuals' openness to,4,5 stigmatization of,6,7 and awareness of6 autism, this study proposes autism acceptance as a new attitude construct to be studied and measured.

Autistic advocates increasingly emphasize the difference between awareness and acceptance. While acceptance acknowledges that autistic individuals do not need to be fixed or cured but accepted for who they are as they are,8,9 awareness seeks to identify autistic differences. Acceptance is also closely aligned with the neurodiversity movement, which conceptualizes autism as a part of natural diversity and challenges prejudice against autism.8,10 Previous studies have shown that the perception of being accepted by others benefits autistic individuals. For instance, Cage et al. reported that feeling accepted by society, family, and friends significantly predicted autistic individuals' depression and stress levels.11 However, currently, there is no instrument that measures nonautistic individuals' autism acceptance. Therefore, this study aimed to construct and test an instrument to measure this phenomenon and use the instrument to identify subgroups of individuals with low autism acceptance.

There have been previous attempts to validate instruments measuring attitudes about autisms, but they were only indirectly related with acceptance. For instance, the Openness Scale measures how much a person likes to be around an autistic peer or how much a person thinks an autistic peer is different from him/her.5 Other researchers have examined stigma associated with autism, a construct likely to be inversely related to acceptance, using the Autism Stigma and Knowledge Questionnaire (ASK-Q)7 or the Social Distance Scale.6 These attitude scales have enabled research on factors that are potentially associated with attitudes toward autism such as previous contact experience, autism knowledge, awareness of neurodiversity framework, and various demographic characteristics.

Potentially Associated Factors

Previous contact, autism knowledge, and neurodiversity awareness

Previous studies reported that positive attitudes about autism were associated with (1) accurate autism knowledge12,13 and (2) higher quality and quantity of previous contact with autistic individuals.4,6,14 With regard to the latter, Gardiner and Iarocci4 also reported that among participants who reported having had at least one direct contact with autistic individuals, only quality of contact was a significant predictor or positive attitudes about autism. In regard to neurodiversity awareness, Kapp et al.8 found that both nonautistic and autistic individuals who were aware of the neurodiversity movement had more positive emotions about autism and did not endorse attempting to cure autistic symptoms compared with those who were not aware of the neurodiversity movement.

Demographic variables

Although findings are inconsistent, there is growing evidence indicating that females have more positive attitudes toward autistic individuals.6,15–17 In relation to education level, Kapp et al.8 found that a higher education status was linked with higher neurodiversity awareness, perhaps because individuals with a higher education level have more accurate knowledge about autism and may reject false and stereotyped beliefs about autism. Lastly, ethnicity may be connected to attitudes about autism because cultural values and societal expectations about autism may differ depending on one's ethnic background. For instance, Gillespie-Lynch et al.12 reported that Lebanese college students were more likely than US students to stigmatize autism. However, Gillespie-Lynch et al.12 also found that after accounting for other variables measuring personal characteristics and experiences such as quality of previous contact and autism knowledge, the effect of country of origin was not significant.

The Current Study

The first purpose of this pilot study is to provide an initial validation of a self-report instrument measuring nonautistic adults' acceptance of autistic individuals; it is named the Autism Attitude Acceptance Scale (AAAS), hereafter. The author hypothesized that the AAAS would accurately define and measure an autism acceptance construct that has characteristics distinct from existing attitude scales.

The second purpose of this study is to utilize the AAAS to address the following two research questions:

(RQ1) How is autism acceptance, as measured by the AAAS, associated with each of the following variables that measure disability-related experience or awareness: autism knowledge, quality and quantity of previous contact with autistic individuals, and awareness of the neurodiversity framework?

(RQ2) How is autism acceptance, as measured by the AAAS, associated with each of the following demographic variables: age, gender, ethnicity, and education level?

Because this is the first study to conceptualize and assess nonautistic individuals' autism acceptance, the author did not make any hypothesis a priori; rather, she adopted an exploratory approach to examine the two research questions.

Method

Construction of the AAAS items

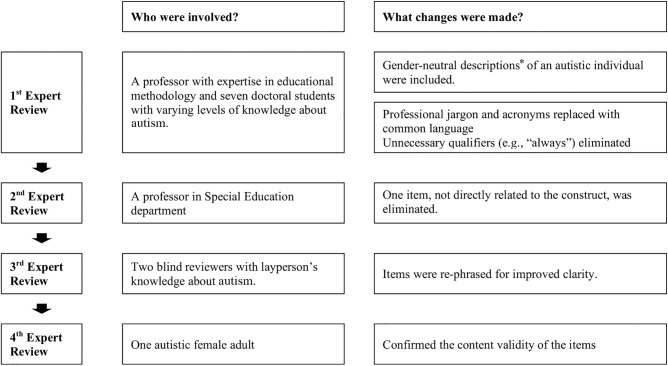

Table 1 illustrates the search methods used to retrieve relevant literature and establish a theoretical foundation of the AAAS. The author collaborated with three graduate students with varying levels of expertise in special education to extract salient and frequently occurring themes among the identified literature. Informed by the literature review, the author drafted 22 new survey items, reflecting values emerged from (1) existing literature about attitudes toward autism (i.e., how a person likes to be or feels comfortable around autistic individuals), (2) deaf literature (i.e., how much a person values differences), and (3) neurodiversity movement (i.e., how much a person is willing to provide appropriate accommodations, and how much a person believes that autistic individuals have to follow nonautistic social norms). Furthermore, the author adapted the affect, behavior, and cognition (ABC) model22,23 to capture different domains of attitudes. Consequently, a professor in the educational methodology department, seven doctoral students with varying levels of knowledge about autism, a professor in the special education department, two blind reviewers, who had a layperson knowledge about autism and did not know who created the survey, and one autistic female adult conducted several rounds of peer review to finalize pilot items (Fig. 1). After the expert review, 21 items with 7 items in each of the behavioral, affective, and cognitive attitude domains remained.

Table 1.

Search Methods Used to Retrieve Relevant Literature

| Type of literature | References examined | Rationale for examining particular types of literature | Extracted components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Existing literature on attitudes about autism | The Openness Scale,5 the ASK-Q,7 the AAS,18 the MAS,16,17 the Social Distance Scale,6 and the SATA19 | Existing surveys about attitudes about autism include items that measure the perceptions toward autism. | • Preferences (like/dislike) • Degree of comfort • Willingness to engage with an autistic person |

| Meaning of acceptance in the deaf communities | Cambra et al.20 and Friedner and Block21 | • Articles on the acceptance of autism were scarce. • The autistic culture of acceptance was considered similar to the acceptance in the deaf culture.20,21 |

• There are different ways to be in the world • Such differences should be valued |

| Literature on neurodiversity | Several blog posts uploaded on the ASAN | ASAN provides a forum for their voices to be heard and seeks to promote a culture of inclusion and neurodiversity. | • Willingness to provide appropriate accommodations • Challenging the assumptions that autistic individuals should follow nonautistic social norms |

| ABC model of attitude | Antonak and Livneh22 | Attitudes can be nuanced or ambivalent in that a person can simultaneously possess negative feelings and beliefs and show contradictory behaviors.23 | • Affective: emotions concerning autistic individuals • Behavioral: typical behavioral tendencies in the presence of autistic individuals • Cognitive: beliefs about autism |

AAS, Autism Awareness Survey; ABC, affect, behavior, and cognition; ASAN, Autistic Self Advocacy Network; ASK-Q, Autism Stigma and Knowledge Questionnaire; MAS, Multidimensional Attitudes Scale Toward Persons With Disabilities; SATA, Societal Attitudes Toward Autism Scale.

FIG. 1.

Expert review process. *Consisting of basic information about the person such as job, positive personality attributes (i.e., being diligent), and behavioral characteristics.

Additional scales

The survey included the Multidimensional Attitudes Scale Toward Persons with Disabilities (MAS) and the Openness Scale to support the validity of the AAAS. The author used the MAS as the validity scale because it consists of cognitive, affective, and behavioral subscales, matching the structure of the AAAS. The survey also included the Level of Contact Report,24 the Quality of Contact Scale,25 the Autism Awareness Survey (AAS),18 a question concerning neurodiversity awareness,8 and a demographic questionnaire to collect data on variables that might be conceptually and operationally related to autism acceptance. Table 2 provides detailed descriptions of the additional scales.

Table 2.

Surveys Used to Establish Validity and Examine Relationships with Potentially Related Variables

| Survey | Description |

|---|---|

| MAS16,17 | The original MAS consists of 34 self-report items on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). The MAS targets attitudes toward individuals with physical disabilities, with high scores indicating negative attitudes toward people with disabilities. The MAS has recently been adapted to target adults' attitudes toward autistic individuals. The adapted version also reported high internal consistency (α = 0.88 for cognitive domain, 0.88 for behavior, and 0.61 and 0.74 for affect). |

| Openness Scale5 | The Openness Scale measures undergraduate students' attitudes toward an autistic peer. Participants first read a vignette describing a college student, who presents autism-like behavioral characteristics and then rate seven statements on a 5-point Likert scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The responses are added to produce a total score, and higher total scores indicate more openness, positive attitude to a peer with autism-like characteristics. The internal consistency was acceptable with an alpha value of 0.77. |

| Level of Contact Report24 | The original Level of Contact Report measures the level of exposure to a person with mental illness, and Gardiner and Iarocci4 revised the wording of the items to measure the intimacy level of the previous contact with autistic individuals. Participants indicate their level of contact and intimacy by responding “yes” or “no” to 12 statements, and each statement describes a different level of intimacy of contact with an autistic individual. A higher score thus represents a more intimate level of exposure. |

| Quality of contact25 | The original five-item Quality of contact subscale from the contact measure of Islam and Hewstone25 measures attitudes toward different religious groups, and Mahoney13 adapted the scale by changing the referent for the items from the religious groups to “individual with autism.” The participants were asked to rate the extent to which they had experienced previous contact with someone with autism as equal, cooperative, pleasant, voluntary, and intimate on a scale from one to seven, with lower score representing a lower quality interpersonal contact. Mahoney13 reported moderate internal consistency (α = 0.68) of the adapted version of the scale. |

| AAS18,26 | The AAS assesses nonautistic individuals' knowledge about autism. Originally developed by Stone,21 the scale has been adapted and revised by Tipton and Blacher20 to measure health care professional and undergraduate students' knowledge of autism, respectively. Tipton and Blacher's20 version of the scale was used in the current study. Participants responded to the 14 true or false statements about autism on a 5-point correctness scale (0 = definitely disagree, 4 = definitely agree). Higher total score indicates more accurate knowledge about autism. Internal consistency within the current data set was 0.76. |

| Questions related to neurodiversity | Participants answered a question from Kapp et al.8 as to whether they were aware of neurodiversity, and if so, how they became aware. Response options were “No, I am not aware of it,” “Yes, I heard of it online,” “Yes, I read about it in a book or magazine,” “Yes, I heard of it in person,” “Yes, I heard about it at a conference,” “Yes, I heard about it at a support group,” and “Yes, but none of the above (and write the responses).” |

| Demographic questions | Demographic information (gender, age, race, age, presence of diagnosis of other neurodevelopmental disabilities, and highest level of education). |

AAS, Autism Awareness Survey; MAS, Multidimensional Attitudes Scale Toward Persons with Disabilities.

Procedures

Participants completed the items online via Qualtrics survey software. Faculty members at a Jesuit university in the Northeastern United States shared the link to the survey and a brief description of the study with their students. Also, the author posted the link on her social networking system (e.g., author's Twitter, public Facebook profile, and listserv of graduate housing at universities in Boston, and websites for Korean students and families living in Boston areas) to elicit responses from a varied participant pool. The author determined that the minimum number of participants needed was 100, based on Gorsuch's27 recommendations for conducting principal component analysis (PCA).

The Boston College IRB office approved the study procedure, including informed consent (IRB#: 18.095.01). After giving their consent by clicking the “Consent Given” button at the bottom of the online consent form, all participants read a brief description of autism. Then they completed the AAAS with items presented in random order. Subsequently, they completed the Openness Scale, the MAS, and previous contact measures in random order, with items presented in random order. Finally, participants answered if they were aware of the neurodiversity framework and completed a demographic questionnaire.

Statistical analyses

Development of the AAAS

The author identified and flagged potential outliers by calculating the means and variances of each item, and then used PCA with oblimin rotation in SPSS v.23 to optimize and assess the structural and psychometric properties of the AAAS. The process followed Hair et al.'s28 and Chan and Idris'29 guidelines for survey development* and substantive criteria (i.e., whether an item aligns with the conceptual framework of acceptance) to optimize the item structure. The adequacy of Cronbach's alphas was determined based on Nunally and Bernstein's criteria,30 which consider values above 0.6 acceptable in exploratory research. Finally, the author calculated Cronbach's alphas for the final set of items to confirm the internal consistency. Pearson's r correlations were computed to examine the associations between the AAAS and the MAS and the Openness Scale to determine the convergent and divergent validity of the AAAS.

Associations between the AAAS and purported variables

To address the first research question, the author examined the associations between the AAAS and (1) autism knowledge, (2) the quality and quantity of contact with autistic individuals, and (3) neurodiversity awareness using Pearson's r for the AAAS subscales and continuous variables (i.e., autism knowledge and the quality and quantity of previous contact) and independent t-tests for the discrete and dichotomous variables (i.e., acceptance levels and neurodiversity awareness, respectively).†

To address the second research question, the author examined the association between the AAAS and demographic variables and computed Pearson's r correlation between age and the subscales of the AAAS. The author also conducted an independent t-test to examine differences in acceptance levels based on participants' gender (female vs. male) and a set of one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) to examine differences in acceptance levels based on ethnicity and education level. The ethnicity variable was categorized into Asian,‡ white, and other, given that Asian and white represented the majority of the sample. The education level was categorized into bachelor's degree, master's or professional degree, and PhD degree. Participants with an associate degree or without a degree were not included in the analysis due to their small number (n = 5). Finally, the author computed post hoc Tukey HSD comparisons for variables found to be significant in the ANOVA.

Results

Participant sample

The initial pilot sample consisted of 129 adults. The author eliminated five participants who completed less than 80% of the entire survey from the analysis. List-wise deletion was used because the data were missing at random, and all variables included in the analyses had less than 10% missing data.31 The author also excluded two individuals, who reported on the Level of Contact measure that they had a diagnosis of autism, from the analysis. The final sample included 122 participants. Table 3 reports their demographic characteristics.

Table 3.

Participant Demographic Characteristics

| Demographic variable | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 41 (33.6) |

| Female | 81 (66.4) |

| Race | |

| Asiana | 59 (48.4) |

| Whiteb | 57 (46.7) |

| African Americanc | 20 (16.4) |

| Others | 4 (3.3) |

| History of other developmental disabilitiesd | 3 (2.5) |

| Highest degree of educationa | |

| Some college, no degree | 5 (4.1) |

| Bachelor's degree | 40 (32.8) |

| Master's or professional degree | 60 (49.2) |

| Doctorate |

11 (9.0) |

| |

Mean (SD) |

| Age (years) | 33.21 (10.30), range 19–67 |

n = 122. Race categories are not mutually exclusive.

Defined as a person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam.

A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa.

A person having origins in any of the African racial groups.

Three participants self-identified as having different types of developmental disability that is not autism. These participants were included in the analysis because the purpose of the study was to create a scale measuring autism acceptance of nonautistic individuals. Also, a sensitivity test showed that disability status was not a significant predictor of the scores of AAAS in the current data.

AAAS, Autism Attitude Acceptance Scale.

Basic description of the data

Table 4 shows the mean and variance of each item and the initial factor loadings from the rotated pattern matrix. The mean of the 21 items was 3.24 (variance = 1.41). C4 was flagged for its relatively high variance.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics of 21 Items by Cognitive, Behavioral, and Affective Domains

| Label | Item | Mean (variance) | Percentage of agreed (%)a | Factor patternb |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| C1 | Autism is a unique way of being that should be appreciated. | 3.81 (1.32) | 67.5 | 0.77 | ||

| C2 | People need to learn more about autism to support individuals with autism better. | 3.16 (1.31) | 80 | 0.71 | ||

| C3 | When individuals with autism flap their hands, it's no different from people without autism tapping their feet in terms of their appropriateness. | 3.13 (1.35) | 33.4 | 0.63 | ||

| C4 | Individuals with autism represent a minority group just like LGBTQ or racial minority groups. | 3.26 (2.05) | 50 | 0.56 | ||

| C5 | It is important for researchers and doctors to devote resources to genetic and biological research to find a cure for autism.c | 1.98 (1.24) | 74.2 | 0.82 | ||

| C6 | Eliminating individuals' autistic symptoms can support a better quality of life for them.c | 2.17 (1.18) | 67.5 | 0.73 | ||

| C7 | It is important for an individual with autism to get interventions about how to pick up on social cues to make friends.c | 2.00 (0.76) | 67.5 | 0.66 | ||

| B1 | I start conversation with Andy. | 3.88 (1.31) | 58.4 | 0.87 | ||

| B2 | If I am Andy's colleague, I personally work with Andy to help him/her find a work environment that works best for Andy. | 3.33 (1.45) | 70 | 0.76 | ||

| B3 | I consciously try to include Andy in social events. | 3.62 (1.46) | 61.9 | 0.79 | ||

| B4 | If I am Andy's colleague, I work with management on ways to inform the employees of the department to be knowledgeable about autism. | 3.85 (1.37) | 73.3 | 0.81 | ||

| B5 | I avoid Andy if I can.c | 3.85 (1.56) | 16.6 | 0.80 | ||

| B6 | I try to change the environment as much as possible to accommodate Andy's needs. | 3.74 (1.13) | 69.2 | 0.74 | ||

| B7 | I try to get to know Andy on a personal level. | 3.68 (1.33) | 58.4 | 0.76 | ||

| A1 | I enjoy having a coffee break with Andy. | 3.48 (1.38) | 51.7 | 0.72 | ||

| A2 | I prefer not to work on the same project with Andy.c | 3.12 (1.75) | 39.1 | 0.76 | ||

| A3 | I feel comfortable hanging out with Andy. | 3.24 (1.41) | 45 | 0.76 | ||

| A4 | I feel comfortable sitting next to Andy. | 3.57 (1.61) | 53.3 | 0.73 | ||

| A5 | I am embarrassed if Andy repeats the same phrases in front of the clients.c | 3.00 (1.49) | 40 | 0.59 | ||

| A6 | Making a conscious effort to accommodate Andy is stressful for me.c | 3.12 (1.42) | 40 | 0.45 | 0.69 | |

| A7 | I am annoyed if Andy keeps asking me to repeat what I just said.c | 3.18 (1.56) | 46.6 | 0.51 | 0.58 | |

| Total | 3.24 (1.41) | 1.41 | ||||

Percentage of participants who reported agreed or strongly agreed.

Oblimin rotated factor pattern.

Reverse coded. Five-point response Likert scale of “1” strongly disagree to 5 “strongly agree.”

LGBTQ, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer or questioning.

Optimization

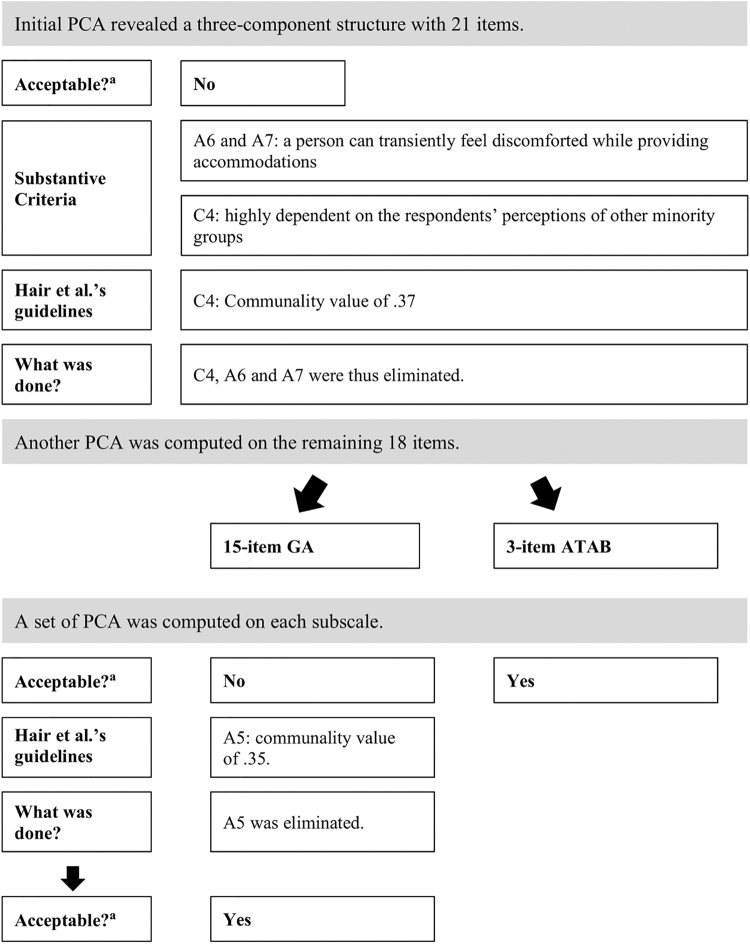

The initial PCA revealed a three-component structure with 21 items loading onto three factors with eigenvalues of one or higher, together explaining 52.89% of the variance (Table 1). Sixteen items cleanly loaded on factor 1. Items C5, C7, and C8 loaded onto factor 2, and A6 and A7 loaded both on factors 1 and 3. The emergent three-factor structure did not meet Hair et al.'s guidelines28 for survey development.§

The author conducted the optimization based on the emergent factor structure, substantive standards, reviewing the wording and content of the items, and statistical criteria.28,29 Items C4, A6, and A7 were eliminated because they did not meet the expected substantive and statistical criteria,28,29 and a detailed rationale is presented in Figure 2. Another PCA computed on the remaining 18 items resulted in the items cleanly loading onto two factors with eigenvalues of 1 or higher, explaining 57.21% of the variance. Because the data structure that emerged did not correspond to the ABC model as hypothesized, the rest of the optimization process aimed to create two subscales: General Acceptance (GA) and Attitudes toward Treating Autistic Behaviors (ATAB).

FIG. 2.

Optimization process. aAcceptable indicates that the scale met Hair et al.'s and Chan and Idris's guidelines for survey development and substantive standards. PCA, principal component analysis.

Attitudes toward Treating Autistic Behaviors

The three-item ATAB subscale also loaded onto one factor using PCA, explaining 60.60% of the variance in the PCA. Including the KMO value of 0.68, which indicated mediocre adequacy of the sampling to summarize the information, the ATAB met all statistical criteria outlined by Hair et al.28

General Acceptance

The author conducted an additional PCA on the remaining 15 items. To fulfill the statistical standard established by Hair et al.,28 A5 was eliminated due to its low communality value, 0.35. The resulting 14 items comprise the final AAAS. This scale met all Hair et al.'s assumptions28 and loaded onto one factor explaining 58.68% of variance. The item component factor loadings ranged from 0.62 to 0.88, which is optimal.

Reliability analysis

The Cronbach's alpha of the GA subscale was 0.92, suggesting good internal consistency.30 The ATAB subscale had a Cronbach's alpha of 0.67, which Nunally and Bernstein30 consider acceptable. A series of Cronbach's alphas with one item deleted from each scale revealed that the removal of any item would not have increased the internal consistency of the GA and ATAB.

Final items

The final version of the AAAS consists of two subscales, scored on a 5-point scale (5, agree; 4, somewhat agree; 3, neutral; 2, somewhat disagree; 1, disagree). Table 5 presents the factor loading of final items of the AAAS. The mean of the ATAB was 2.05 (SD = 0.8). The mean of the GA was 3.63 (SD = 0.91). See Supplementary Data for the final items of the AAAS.

Table 5.

Pattern Matrix and Factor Loading of Final Items of Autism Attitude Acceptance Scale

| Item | Factor patterna |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| B1 | 0.87 | |

| B4 | 0.82 | |

| B5 | 0.81 | |

| C1 | 0.79 | |

| B7 | 0.78 | |

| B2 | 0.78 | |

| B6 | 0.77 | |

| A3 | 0.74 | |

| C2 | 0.74 | |

| A1 | 0.73 | |

| A2 | 0.73 | |

| A4 | 0.72 | |

| C3 | 0.60 | |

| C5 | 0.84 | |

| C6 | 0.76 | |

| C7 | 0.69 | |

Extracted with principal component analysis; oblimin rotated.

Validity analysis

Table 6 reports the correlation matrix between other autism attitude scales and the subscales of the AAAS. There were no significant correlations between the ATAB and the three subscales of the MAS and the Openness Scale, establishing divergent validity from the existing scales. The GA was positively and significantly correlated with the cognitive, behavioral, and affective subscales of the MAS and the Openness Scale, suggesting concurrent validity.

Table 6.

Associations Between Autism Attitude Acceptance Scale Subscales and (1) Validity Scales, and (2) Autism Knowledge and Previous Contact Measures, and (3) Demographic Variables

| GA | ATAB | |

|---|---|---|

| Validity analysis | ||

| Pearson's r correlations | ||

| MAS affective | 0.30* | 0.031 |

| MAS behavioral | 0.50** | 0.073 |

| MAS cognitive | 0.51** | 0.014 |

| Openness measure | 0.79** | 0.002 |

| Relationships with potentially related variables | ||

| Pearson's r correlations | ||

| Autism knowledge | 0.71** | 0.19* |

| Quality of previous contact | 0.47** | 0.25** |

| Quantity of previous contact | 0.58** | 0.29** |

| Age | −0.168 | −0.079 |

| F-value from ANOVA | ||

| Education | 7.87** | 1.05 |

| Ethnicity | 14.30** | 2.04 |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

ANOVA, analyses of variance; ATAB, Attitudes toward Treating Autistic Behaviors; GA, General Acceptance.

Relationship with previous contact variable and purported variables

Previous contact, knowledge, and neurodiversity awareness

Both subscales were positively and significantly correlated with the quality and quantity of previous contact and autism knowledge (Table 6). Subsequently, an independent sample t-test showed a significant difference in GA scores (p = 0.005) between the participants who were aware of the neurodiversity framework (mean = 4.1, SD = 0.90) and who were not aware of the neurodiversity framework (mean = 3.49, SD = 0.87). No difference showed in ATAB scores between these two groups (p = 0.61).

Demographic variables

There was no significant correlation between age and the two subscales. For the GA, female participants (mean = 3.79, SD = 0.87) showed significantly higher scores (p = 0.005) than male participants (mean = 3.33, SD = 0.91). There was a significant effect of ethnicity and education level in GA scores (p = 0.004 and p < 0.001, respectively). Table 7 presents results of the post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test. There were no associations between gender, education, and ethnicity and the ATAB (all ps > 0.05).

Table 7.

Post hoc Comparisons of Ethnicity and Education in the General Acceptance

| Variable | Pair (means) | Mean | Paired differences | Standard error | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | White vs. Asian** | 4.00 vs. 3.49 | 0.51 | 0.17 | 0.005 |

| Asian vs. other** | 3.49 vs. 2.42 | 1.07 | 0.32 | 0.002 | |

| Other vs. white** | 2.42 vs. 4.00 | 1.58 | 0.32 | <0.001 | |

| Education | Bachelor's vs. master's vs. professional** | 3.09 vs. 3.88 | −0.79 | 0.17 | <0.001 |

| Master's or professional vs. PhD | 3.88 vs. 3.95 | −0.07 | 0.28 | 0.99 | |

| Bachelor's vs. PhD* | 3.09 vs. 3.95 | −0.86 | 0.30 | 0.02 |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

Discussion

This study sought to pilot a new instrument that measures nonautistic individuals' acceptance of autism, which is distinct from currently existing measures of autism awareness or autism knowledge. The AAAS elicits nonautistic people's cognitive, behavioral, and affective beliefs about accepting and accommodating autistic individuals without trying to change them, based on the neurodiversity framework. Specifically, a higher GA score indicates that an individual is more accepting of autism as a unique way of being, is more willing to provide support to an autistic person, and feels more comfortable having personal interaction with an autistic person compared with lower scores. A high score in the ATAB suggests endorsement of the notion that autistic behaviors are characteristic of each individual and belief that receiving treatments to reduce autistic symptoms will not benefit autistic individuals. The AAAS can be a useful tool to assess autism acceptance, identify subgroups of people with lower autism acceptance, and evaluate interventions aiming to increase autism acceptance among nonautistic individuals.

The final scale includes the ATAB despite it consisting of only three items because it suggests important nuances in understanding autism acceptance. Subsequent versions of the ATAB should be strengthened with more items in the domain to construct a unitary and valid measure. Because the ATAB and the GA measure different constructs, to gain a more nuanced understanding of nonautistic individuals' autism acceptance, the author recommends not adding their scores to calculate a composite score but rather interpreting the scores of the two subscales separately.

Previous contact, autism knowledge, and awareness of the neurodiversity movement

Both GA and ATAB subscales were significantly associated with autism knowledge, mirroring the associations between knowledge and attitudes about autism repeatedly shown in previous studies.12,13 Also, both quality and quantity of contact were correlated with both subscales of the AAAS. Gardiner and Iarocci4 explained that the decreased anxiety and increased comfort that come from positive and frequent interactions with autistic individuals might mediate the association between social contact and openness. This study supports the importance of social contact in increasing autism acceptance and, ultimately, promoting community conceptions of autism.

Participants' responses to the neurodiversity awareness question was associated only with the GA, suggesting that neurodiversity awareness is not enough to influence individuals' attitudes toward administering treatments to reduce autistic symptoms. A person may need to understand and agree with the neurodiversity movement to score high on the ATAB rather than just be aware of this movement.

Demographic variables

General Acceptance

In keeping with some previous studies,6,15–17 female participants had higher acceptance scores on the GA subscale than males. Findler et al.16 explain that female participants' positive behavioral attitudes toward individuals with disabilities could be due to social constructions of women as caregivers, which may make them feel more obliged to act in a positive manner that fulfills their expected social role. However, female participants may have also provided more socially desirable responses than male participants instead of providing responses that reflect their actual thoughts and feelings.32 Dalton and Ortegren's findings, which showed females tended to report more ethical judgments to appear socially desirable,32 provide evidence that social desirability bias may be one of the driving forces of the significant gender differences. Meanwhile, because males and females had unequal representation in the sample, the effects of gender on different types of domains of autism acceptance need to be investigated with a more balanced number of female and male participants in future studies.

Similar to Kapp et al.'s8 findings, which showed that educational attainment was positively correlated with neurodiversity awareness, participants in this study with higher levels of education had more positive scores on the GA. These findings potentially warrant increasing opportunities for individuals with relatively low educational backgrounds to have high-quality contact with autistic individuals and dispel inaccurate stereotypes about autism.

Finally, while the effect of ethnicity on attitudes has not been well studied, this study showed that white participants had higher scores on the GA than either the Asian group or the mixed group of “other” participants. One explanation is that the appreciation and celebration of autistic differences are more widely recognized in Western cultures compared with Asian cultures, while stigmatization of and discrimination against autism are more prevalent in Asian cultures.33,34 It is also noteworthy that the majority of participants labeled as other were African American. African American children are more likely to be diagnosed with behavioral problems than autistim,35 potentially resulting in difficulties in access to the proper health care system and exacerbation of behavioral symptoms. Also, previous studies have documented that African American families tend to interpret some autistic symptoms of their children as more negative and severe than white families do.36 Together, these factors may have contributed to the low acceptance level of other participants.

Attitudes toward Treating Autistic Behaviors

There were no significant effects of age, gender, education, or ethnicity on the ATAB subscale, indicating that commonly considered demographic variables have little or no bearing on attitudes toward administering treatments that reduce autistic symptoms. This outcome warrants further research to identify underlying mechanisms of the construct captured by the ATAB and unexplored contextual factors.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it uses an unstratified convenience sample from the author's personal social networks. Second, due to the limitations of demographic data collected, many analyses were not possible. For instance, the demographic category of “Asian” and “other” likely does not adequately capture the heterogeneity of these groups. Third, the neurodiversity item was dichotomized and did not differentiate between people who had merely heard of the term and those who, for example, strongly identified as part of the neurodiversity movement; this may have contributed to the insignificant differences of the ATAB scores based on participants' awareness of the neurodiversity framework. Finally, the survey was not designed to assess whether or not participants were providing socially desirable responses (e.g., with Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale37).

Implications for Future Research

Despite these limitations, the findings from the current study have several implications for future studies. First, future researchers should identify the mechanisms and dimensionality underlying acceptance attitudes. Additional research, perhaps using qualitative methods, could ascertain whether the items elicit the intended constructs in various contexts (e.g., different degrees of autism severity, work vs. social contexts) and may aid in further understanding autism acceptance.

Moreover, C7, “It is important for an individual with autism to get interventions about how to pick up on social cues to make friends” attempted to assess whether a participant believes that it is necessary for autistic individuals to follow nonautistic social expectations to make friends, which is consistent with neurodiversity movement. However, some neurodiversity advocates who believe social cues are adaptive skills that can ameliorate autistic symptoms may have agreed to C7. This potential discrepancy may also have led to the insignificant association between awareness of the neurodiversity framework and the ATAB. Future studies need to examine attitudes toward specific types of treatment and autism acceptance to fully operationalize acceptance.

Item C4, “Individuals with autism represent a minority group just like LGBTQ or ethnic minority groups,” was dropped in the process of optimization to meet predetermined criteria and to avoid the influence on participants' positive or negative attitudes toward LGBTQ or ethnic minority groups on their response to the item. However, Walker links neurodiversity to gender, ethnicity and culture by noting that there is no one “right” style of neurocognitive functioning just as there is no one “right” gender, ethnicity, and culture.38 The item, therefore, captures constructs that may be associated with the neurodiversity framework. Rather than dismissing the item as irrelevant, future studies should investigate how attitudes toward ethnic and gender minority groups are associated with attitudes about autism to identify ways to utilize the items such as C4 to accurately assess autism acceptance.

Conclusion

Highlighting the importance of helping nonautistic individuals to recognize the bidirectional nature of social difficulties experienced by autistic individuals, this study presents the development and validation of the AAAS, a new instrument that measures nonautistic individuals' autism acceptance. The AAAS may serve as a screener to identify the subgroups with particularly negative attitudes about autism and as an outcome measure to assess the effectiveness of these interventions. The findings urge the need to identify the underlying mechanism and moderating factors of autism acceptance and neurodiversity framework to develop effective psychoeducation interventions that promote nonautistic individuals' autism acceptance.

Supplementary Material

Authorship Confirmation Statement

The author (S.Y.K.) developed the items, administered the survey, conducted the analysis, and drafted the article. The article has been submitted solely to this journal and is not published, in press, or submitted elsewhere.

Acknowledgments

The survey development process largely followed the instructions given in the Survey Method class, Fall 2017. The author thanks Dr. Laura O'Dwyer for the instructive class that made the study possible and for the critical feedback on items and the earlier versions of the article. The author also thanks Dr. Kristen Bottema-Beutel for insightful feedback and critique on this work, everyone who was involved in the expert review process and the study group, and many participants who agreed to participate in the study.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received.

Supplementary Material

A scale was considered to have met the assumptions of the guidelines when the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was ≥0.6, the size of the determinant was >0, Bartlett's test of sphericity rejected the null hypothesis, and all items had communalities >0.5.28 In the factor analysis, factors were extracted based on eigenvalues >1, and items with factor loading values of less than 0.40 were excluded.29

Because there were too few responses in each response category that described the source of information about the neurodiversity framework, no additional analysis of the source was conducted.

A person having origins in any of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent.

The KMO was 0.91, and the determinant was <0; Bartlett's test of sphericity rejected the null hypothesis. However, several items had communality values lower than 0.5 such as C4, and A5, which had communality values of 0.37, and 0.41, respectively.

References

- 1. Reindal SM. A social relational model of disability: A theoretical framework for special needs education? Eur J Spec Needs Educ. 2008;23(2):135–146. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sasson NJ, Morrison KE. First impressions of adults with autism improve with diagnostic disclosure and increased autism knowledge of peers. Autism. 2017;23(1):50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Slaughter V, Rosnay MD. Theory of Mind Development in Context. London: Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gardiner E, Iarocci G. Students with autism spectrum disorder in the university context: Peer acceptance predicts intention to volunteer. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;44(5):1008–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nevill REA, White SW. College students' openness toward autism spectrum disorders: Improving peer acceptance. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(12):1619–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gillespie-Lynch K, Brooks PJ, Someki F, et al. Changing college students' conceptions of autism: An online training to increase knowledge and decrease stigma. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(8):2553–2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harrison AJ, Bradshaw LP, Naqvi NC, Paff ML, Campbell JM. Development and psychometric evaluation of the autism stigma and knowledge questionnaire (ASK-Q). J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(10):3281–3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kapp SK, Gillespie-Lynch K, Sherman LE, Hutman T. Deficit, difference, or both? Autism and neurodiversity. Dev Psychol. 2013;49(1):59–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sinclair J. Why I dislike “person first” language- Jim Sinclair. Autism MythBusters RSS. https://autismmythbusters.com/general-public/autistic-vs-people-with-autism/jim-sinclair-why-i-dislike-person-first-language/. Accessed January 6, 2020.

- 10. Neeman A. The future (and the past) of autism advocacy, or why the ASA's magazine, The Advocate, wouldn't publish this piece. Disabil Stud Q. 2010;30(1). DOI: 10.18061/dsq.v30i1.1059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cage E, Monaco JD, Newell V. Experiences of autism acceptance and mental health in autistic adults. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;48(2):473–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gillespie-Lynch K, Daou N, Sanchez-Ruiz M-J, et al. Factors underlying cross-cultural differences in stigma toward autism among college students in Lebanon and the United States. Autism. 2019;23(8):1993–2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mahoney D. College students' attitudes toward individuals with autism. Diss Abstr Int. 2008;68(11-B):7672. [Google Scholar]

- 14. White D, Hillier A, Frye A, Makrez E. College students' knowledge and attitudes towards students on the autism spectrum. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(7):2699–2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kuzminski R, Netto J, Wilson J, Falkmer T, Chamberlain A, Falkmer M. Linking knowledge and attitudes: Determining neurotypical knowledge about and attitudes towards autism. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0220197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Findler L, Vilchinsky N, Werner S. The multidimensional attitudes scale toward persons with disabilities (MAS). Rehabil Couns Bull. 2007;50(3):166–176. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dachez J, Ndobo A, Ameline A. French validation of the multidimensional attitude scale toward persons with disabilities (MAS): The case of attitudes toward autism and their moderating factors. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(8):2508–2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tipton LA, Blacher J. Brief report: Autism awareness: Views from a campus community. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;44(2):477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Flood LN, Bulgrin A, Morgan BL. Piecing together the puzzle: Development of the societal attitudes towards autism (SATA) scale. J Res Spec Educ Needs. 2012;13(2):121–128. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cambra C. Acceptance of deaf students by hearing students in regular classrooms. Am Ann Deaf. 2002;147(1):38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Friedner M, Block P. Deaf studies meets autistic studies. Senses Soc. 2017;12(3):282–300. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Antonak RF, Livneh H. The Measurement of Attitudes Toward People with Disabilities: Methods, Psychometrics and Scales. Springfield, IL: Thomas; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brehm S, Kassin SM, Fein S. Social Psychology. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Holmes EP, Corrigan PW, Williams P, Canar J, Kubiak MA. Changing attitudes about schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 1999;25(3):447–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Islam MR, Hewstone M. Dimensions of contact as predictors of intergroup anxiety, perceived out-group variability, and out-group attitude: An integrative model. Pers Soc Psychol B. 1993;19(6):700–710. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stone WL. Cross-disciplinary perspectives on autism. J Pediatr Psychol. 1987;12(4):615–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gorsuch RL. Factor Analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective. Upper Saddle River, N.J.; London: Pearson Education; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chan LL, Idris N. Validity and reliability of the instrument using exploratory factor analysis and Cronbach's alpha. Int J Acad Res Bus So Sci. 2017;7(10):400–410. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Raaijmakers QA. Effectiveness of different missing data treatments in surveys with Likert-type data: Introducing the relative mean substitution approach. Educ Psychol Meas. 1999;59(5):725–748. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dalton D, Ortegren M. Gender differences in ethics research: The Importance of controlling for the social desirability response bias. J Bus Ethics. 2011;103(1):73–93. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ilias K, Liaw JHJ, Cornish K, Park MSA, Golden KJ. Wellbeing of mothers of children with “A-U-T-I-S-M” in Malaysia: An interpretative phenomenological analysis study. J Intell Dev Disabil. 2016;42:74–89. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Obeid R, Daou N, Denigris D, Shane-Simpson C, Brooks PJ, Gillespie-Lynch K. A cross-cultural comparison of knowledge and stigma associated with autism spectrum disorder among college students in Lebanon and the United States. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(11):3520–3536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mandell DS, Listerud J, Levy SE, Pinto-Marin JA. Race differences in the age of diagnosis among Medicaid eligible children with autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(13):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burkett K, Morris E, Manning-Courtney P, Anthony J, Shambley-Ebron D. African American families on autism diagnosis and treatment: The influence of culture. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45:3244–3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Andrews P, Meyer RG. Marlowe–Crowne social desirability scale and short Form C: Forensic norms. J Clin Psychol. 2003;59(4):483–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Walker N. Neurodiversity: Some Basic Terms & Definitions. NEUROCOSMOPOLITANISM. https://neurocosmopolitanism.com/neurodiversity-some-basic-terms-definitions/. Published September 27, 2014. Accessed January 7, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.