Abstract

Autistic masking is an emerging research area that focuses on understanding the conscious or unconscious suppression of natural autistic responses and adoption of alternatives across a range of domains. It is suggested that masking may relate to negative outcomes for autistic people, including late/missed diagnosis, mental health issues, burnout, and suicidality. This makes it essential to understand what masking is, and why it occurs. In this conceptual analysis, we suggest that masking is an unsurprising response to the deficit narrative and accompanying stigma that has developed around autism. We outline how classical social theory (i.e., social identity theory) can help us to understand how and why people mask by situating masking in the social context in which it develops. We draw upon the literature on stigma and marginalization to examine how masking might intersect with different aspects of identity (e.g., gender). We argue that although masking might contribute toward disparities in diagnosis, it is important that we do not impose gender norms and stereotypes by associating masking with a “female autism phenotype.” Finally we provide recommendations for future research, stressing the need for increased understanding of the different ways that autism may present in different people (e.g., internalizing and externalizing) and intersectionality. We suggest that masking is examined through a sociodevelopmental lens, taking into account factors that contribute toward the initial development of the mask and that drive its maintenance.

Lay summary

Why is this topic important?

Autistic masking is a complicated topic. We currently think that masking includes things such as making eye contact even if it makes you feel uncomfortable, or not talking about your interests too much for fear of being labeled “weird.” There is a lot about masking that we do not know yet, but it is important to understand masking as we think that it might have a negative effect on autistic people.

What was the purpose of this article?

The purpose of this article was to look at current explanations of masking, and try to figure out what is missing.

What do the authors conclude?

We conclude that work on masking needs to think about autistic people in a different way. Autistic people grow up in a social world and experience a lot of negative views about autism and autistic people. We argue that we need to understand how this social world and the trauma that can come from being part of it contributes toward masking. We also argue against the idea that masking is a “female” thing that occurs as a result of there being a “female-specific” subtype of autism, because this might make it harder for some people to get a diagnosis (e.g., nonbinary people, and men and women who do not fit with any of the current criteria). Instead we argue that people need to recognize that autism does not look like one “type” of person, and try to separate ideas about masking from ideas about a person not fitting a stereotype.

What do the authors recommend for future research on this topic?

Though masking is called a “social strategy,” there has not been a lot of social theory applied to masking research. We recommend that researchers use theories about how people try to fit in, and theories about how people exclude and hurt people who are different. This can help us to understand why autistic people mask. We also stress the need to understand that masking is not necessarily a choice, and that there are many unconscious aspects. We argue that researchers should try to find out when masking starts to happen (e.g., in childhood) and what makes people feel like they need to keep up the mask. We also recommend lot more research into autistic identity, and how different parts of identity (including things such as gender, race, and co-occurring conditions) might mean that someone has to mask more (or less), or in different ways.

How will this analysis help autistic adults now and in the future?

We hope that this analysis will help researchers to understand that some aspects of masking might be unique to autistic people, but some aspects might be like other kinds of “pretending to be normal” that other people who are socially excluded use to try and fit in. We hope that our suggestions can help to improve our understanding of masking, and lead to research that makes life better for autistic people.

Keywords: autism, camouflaging, masking

Introduction

Autistic masking (also referred to in the literature as camouflaging,1 compensation,2 and most recently “adaptive morphing”3) is the conscious or unconscious suppression of natural responses and adoption of alternatives across a range of domains including social interaction, sensory experience, cognition, movement, and behavior. Masking is an emerging research area, and as such there is variation in the terminology used to describe these experiences. Although some scholars draw a conceptual distinction between masking/camouflaging/compensation1,4 and which aspects constitute subcomponents of another, we use masking here holistically as an umbrella term to refer to the collection of these experiences, as it is the term that has been used by the autistic community themselves.5–7 Masking has been suggested to relate to several key issues in the lives of autistic people, such as relationships and diagnosis,8 suicidality,9 and burnout.10 Thus, gaining a precise understanding of what masking is and how it manifests in the lives of autistic people is essential. This article aims to examine the literature so far, pinpointing factors that have gone unexplored, and ideas for future research that build up a holistic picture integrative of both internal and external aspects of masking. Although autistic masking is the focus of this article, we ask the reader to stay mindful that (1) many autistic people experience neurodivergence and/or marginalization (social exclusion) on multiple axes (i.e., autistic and dyslexic) and that (2) many of these factors might have relevance to other neurodivergent and/or marginalized groups, and are not necessarily limited to autistic people.

Social Context

The historical social context in which autism and research about autistic people are situated is essential to understanding what masking is and why it occurs. Autism is a form of neurodivergence, characterized by differences to the nonautistic population in several domains, including social and cognitive style, and sensory processing.11 Since the 1940s, conceptualizations of autism12,13 have mainly derived from a medical model of disability and “otherness” in which autism (and by consequence, autistic people) has been framed as something to “fix,” “cure,” or in need of intervention14 due to perceived deficits in social communication, repetition, and restriction. The core traits associated with an autism diagnosis are traits found across the human condition15 and it is their shared presence and profile that differentiate autistic and nonautistic people, however, they are often labeled as being “extreme” manifestations.16 A diagnosis of autism is rooted in the specification that one must experience “significant impairment” to be classified as autistic. As such autistic “traits,” “behaviors,” and experiences cannot be labeled autism unless they are experienced negatively or are said to cause “impairment.” As a result, autistic people are viewed as being on the fringe of human normality both in academia, and in society in general.17–19

With a pathologized status comes the experience of stigma, dehumanization, and marginalization.20 Stigma refers to the possession of an attribute that marks persons as disgraced or “discreditable,”21 marking their identity as “spoiled.” Stigmatized persons may attempt to conceal these spoiled aspects of their identity from others, attempting to “pass” as normal.21 Investigation of “passing” and “concealment” has been explored in depth in other stigmatized populations22; however, the application of stigma in autism research is a relatively new endeavor.22,23 Stigma impacts both on how an individual is viewed and treated by others and how that treatment is internalized and interacts with one's identity.20,24

Research has shown that dehumanizing attitudes toward autistic people are still highly prevalent25 despite years of campaigning for awareness and acceptance, and 80% of the stereotypical traits associated with autism are rated negatively by nonautistic people.26 These findings are consistent with the study of Goffman on “stigma,”21 suggesting that familiarity with the stigmatized does not reduce negative attitudes toward them. Rose27 explains: “We move, communicate and think in ways that those who do not move, communicate and think in those ways struggle to empathise with, or understand, so they ‘Other’ us, pathologize us and exclude us for it.” This stigma can manifest in negative social judgments toward autistic people28 who are more likely to report negative life experiences29 including bullying30 and victimization.29 Thus acknowledging the social context in which autistic ways of being are stigmatized and derided14,20,31 is essential for understanding reasons that masking may occur, and what can be done to reduce the pressure to mask and associated impact.

Masking and Social Identity

As a marginalized group, autistic people are consistently presented with the message that their way of being in the world is abnormal, defunct, or impaired.6,20,31 The social norms of autistic people differ to those of the dominant social group, and “passing as normal” or attempting to pass as normal might relieve external consequences (such as bullying) while increasing internal consequences (such as exhaustion and burnout).32 However, the application of social theory to understanding masking is so far sparse. Goffman described the process of concealment at length in “stigma,”21 the impact that conscious and unconscious norms and societal expectations place upon stigmatized persons and the lengths they might go to conceal their otherness. Although masking has been referred to as “social camouflage,” there has been minimal focus33,34 on the role that the social sphere plays in the development and maintenance of masking. A person's identity is shaped by myriad factors, not least the social environment that they inhabit.31 Here we discuss ways in which social theory can be applied to providing a meaningful understanding of masking.

The development of the social self is argued, in part, to arise through the process of reflection of how we are perceived by others.35 Self-perception theory36 suggests that who we perceive ourselves to be is influenced by multiple factors, such as point in the lifespan, or the aspects of our life we are asked to consider (e.g., family and work). This begins to develop in childhood, where we explore different roles through engagement with caregivers and play, and begin to examine ourselves through the lens of the “generalized other”37 (the theoretical outsider through whom we imagine what others might think of who we are). We consider which parts of ourselves we want the world to see, which parts are acceptable.38 Over time, the generalized other is replaced partially through interaction with conspecifics, although we still imagine how they might respond to us through the generalized lens. This is in essence a mentalizing process. Working out what someone might think of us by attempting to adopt their mindset. Goffman described this process in “The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life”39 as one that allows us to manage and control how others perceive us, a form of impression management. In this regard, monitoring how we appear in different social situations is a part of the broader human social experience and not limited to concealing “spoiled” traits. Here the concept of masking is incompatible with the idea of autistic mindblindness.40 To mask one must be aware of how others might potentially view them and suppress aspects of their identity accordingly. The idea that an autistic person might suppress aspects of themselves to “fit in” is also at odds with theories that suggest that autistic people are uninterested in social affiliation.41,42 This assumption, however, might account for the lack of discourse around how social identity theories intersect with autistic masking. The fluctuation of human identity across different social contexts has been well explored in the psychological literature,43 and it is acknowledged that our individual and collective selves may differ. This is yet to be explored in any detail among autistic people.

Social Identity Theory44 argues that our self-perception is dependent upon temporal (i.e., point in the lifespan) and situational (i.e., what is going on at the time) factors, with our identity on a continuum between our personal perception of how we see ourselves as an individual and how we see ourselves as members of a particular group or collective. Our personal and group identities comprise many factors, including our gender, race/ethnicity, sexuality, interests, and personality traits. We may place emphasis on different aspects as we move through different contexts and environments, minimizing aspects of our identity based on their perceived relevance to the current situation and/or group we are in. These contextual shifts may form part of the impression management strategies described by Goffman21 and are impacted by stigma. Goffman described how a “discreditable” person may attempt to avoid stigma or identification by carefully monitoring how they appear to others, whereas a “discredited” (already identified) person may perform the same monitoring to avoid further stigma. The identities of autistic people are often stigmatized at both the individual level (i.e., being labeled by others as “odd” or “weird,”)32 and at the group level (i.e., harmful stereotypes about autistic people26,32) in a way that intersects with other aspects of their identity, leading to what Milton describes as psychoemotional disablement (of autistic identity).23 This stigma occurs for both autistic people who disclose (the discredited) and those who do not (the discreditable), relating to what Botha et al.32 have referred to as a “double bind.”

It is possible that autistic people experience the same contextual identity shifts as nonautistic people in certain aspects of identity (i.e., between interacting with colleagues/friends, e.g.; there is currently very little empirical examination of this), but experience psychological stress specifically from the masking of their autistic self because contextual shifts do not involve the hiding of one's “true self.”1 Rather, emphasis is simply placed on a different aspect of identity as opposed to concealing it. An alternative possibility is that aspects of identity that nonautistic people commonly view as more easily contextualized are for autistic people inherently related to their experiences as an autistic person. For example, experiencing a passionate singular focus on a favorite topic may make a shift away from that aspect of one's identity more difficult, blurring the line between contextual identity shifts and masking. A recent investigation by Schneid and Raz33 found that general impression management and masking were interlinked for autistic people and could not be divorced from one another.

One possible area for exploration in understanding the relationship between contextual identity shifts and masking is the relationship between monotropism35,45 and identity. Monotropism is a theory of autistic cognition grounded in an understanding of attention as interest driven and more singular in focus.45 It states that with limited attentional resources, autistic focus cannot be split between “performing a task well” and “losing awareness of information relevant to all other tasks.”45 The shifting of identity across contexts draws upon attentional resources as we weigh up restrictions, internal (how we feel) and external (what is going on around us) input, and hierarchy (what aspects of our identity that we value). Currently, we know very little about the fluctuation of autistic identity with context. An important factor in this weighing up process is likely to be how safe persons feel in revealing aspects of their identity, particularly if their identity is stigmatized. Cage and Troxell-Whitman's34 findings suggest that masking can fluctuate across contexts, but to develop a more meaningful understanding of this we might also want to ask which aspects of contextual fluctuation are not harmful to autistic people.

Many autistic people experience marginalization on several fronts,46 in ways that intersect with other aspects of their identity. The impact of marginalized status on identity has long been explored by Black scholars.47,48 Du Bois47 wrote of the “double consciousness” of being Black in America: “It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others.” The nature of masking, of having to suppress aspects of one's identity, means having to see oneself through the lens of another. Du Bois stated the difficulty reconciling two competing ideals or aspects of the self, an idea that is drawn upon in the theory of cognitive dissonance.49 Cognitive dissonance occurs when there is a discrepancy between two competing ideals held by an individual, that is, two contradictory beliefs or actions. This discrepancy causes stress, which an individual can attempt to resolve by changing or justifying one of the ideals. To survive as a marginalized person, the suppression of stigmatized aspects of identity may allow someone to walk in two (or more) worlds. However, continuing this suppression in the face of the cognitive dissonance can draw upon significant psychological resources. Cage and Troxell-Whitman34 considered the intersection between stigmatized aspects of identity and masking, using Disconnect Theory50 to examine costs and contexts of masking. They found that autistic adults reported masking across multiple contexts (i.e., at work, with romantic partners), for both conventional and relational reasons. Those who reported higher levels of masking or switching between masking/not masking also reported higher levels of stress, which is consistent with the idea that disconnection from one's identity causes psychological distress. This process of disconnection might be essential in understanding burnout, which has been described as the result of “chronic life stress and a mismatch of expectations and abilities without adequate supports.”10

A potential relationship between masking and negative outcomes such as autistic burnout10 and suicidality9 means that it is important that we acknowledge masking as a self-protective mechanism rather than a necessarily conscious choice. Although masking has been defined as including both conscious and unconscious aspects, much of the research so far has focused on the conscious aspects (i.e., strategies that are externally visible to others). It is possible that the significant energy it takes to mask means that it is only sustainable for a period. To sustain masking long term, the person must find a way to resolve the cognitive dissonance and resulting distress. It stands to reason that the unconscious aspects of masking may be an attempt to resolve this dissonance, by distancing oneself from the process and minimizing the cognitive resources being dedicated toward maintenance. This process might also be compounded by the presence of alexithymia and interoceptive disconnection. Here we outline the potential relationship between these factors, and how they might lead to eventual burnout and exhaustion.

Alexithymia is defined as difficulty identifying one's own emotional states and distinguishing them from bodily states, and has a prevalence of around 50% in the autistic population.51 Difficulty identifying one's own emotions can make it difficult to self-regulate, that is, not realizing that stress is increasing until you are at a breaking point. In addition, autistic people have reported that the energy put into masking can further detract from the already impacted ability to self-regulate,52 placing strain on an already depleted system. This can be related back to Du Bois'47 theory of double consciousness, whereby one aspect of identity is attempting to suppress and control the emotions experienced by the other to maintain safety. The further suppression of internal states and associated coping mechanisms (i.e., stimming53) alongside an already present difficulty identifying one's own emotions could potentially be disastrous, leading to further long-term difficulties in mental health and well-being (i.e., burnout and suicidality).

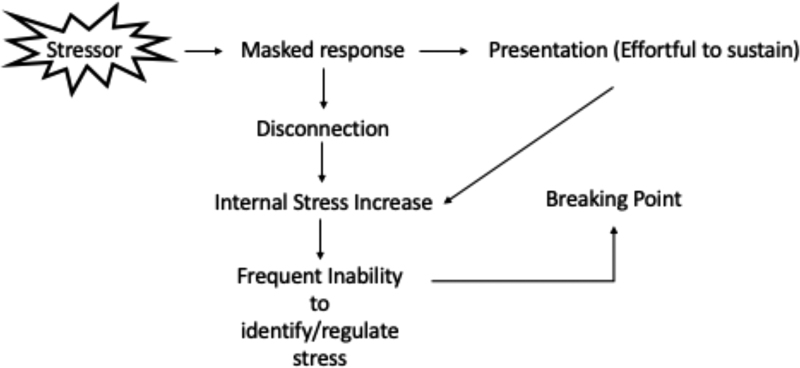

We draw upon Hochschild's54 theory of Emotional Labor as a useful framework for considering the emotionally suppressive side of masking, taking into account the cognitive, bodily, and expressive factors involved and what this might look like for an individual. Future investigation into the more unconscious and dissociative aspects of masking might draw upon Hochschild's theory of Emotional Labor to understand the pathway from masking to burnout, to provide a deeper understanding of how to support people in recovering from mental health issues. Figure 1 outlines the pathway that we are suggesting here; however, this should be considered alongside mediating factors, such as whether sensory needs are being identified and met, and the occurrence/frequency of shorter episodes of fatigue and burnout.

FIG. 1.

Potential model for considering the relationship between masking and autistic burnout. The figure displays a linear relationship from stressor to masking response to presentation (which is effortful for a person to sustain). The masking response feeds separately into disconnection from internal cues, which then leads to an internal stress increase and difficulty regulating associated stress. In addition, the effortful presentation feeds directly into internal stress increase. Together, these flow into what we term “breaking point.” This includes a textual description of the image for those who are using screen-readers.

Masking and Gender

Limited conceptualizations (i.e., a stereotypical idea of a White, male, and nonspeaking child32) of what autism “looks like” have led to underdiagnosis in certain populations, notably people of color55 and women.56 The current diagnostic gap between men and women sits at around 4:1.57 Attempts to remedy underdiagnosis in these populations have led to growth in understanding autistic heterogeneity42 and how autistic characteristics might differ from person to person. However, the view of autism as a manifestation of “extremes” of the human condition has pervaded professional knowledge, leading to debate over whether diagnosis has become “diluted” through the inclusion of those who would not traditionally meet criteria specified in diagnostic measures.58 This view sits in opposition to the acknowledgment that diagnostic criteria and understanding have been based upon external observations of limited samples of (i.e., mostly male) autistic people31,59 .These external observations exclude the impact of other intersectional factors,48 such as identified and unidentified co-occurring conditions, gender, race, sexuality, and cultural background: all of the factors that shape our identity.

Gender disparity in autism diagnosis is historically grounded in diagnostic criteria being based on observations of male children.60 However, it has been strengthened by explanations such as the “extreme male brain” (EMB) theory of autism,61 which posits that autism is a manifestation of cognitive traits associated with males (i.e., “systemizing,” logic), rather than those of females (i.e., empathizing). EMB proposes that fetal androgens may be responsible for the masculine cognitive profile in autistic people, and explain why men are more likely to receive a diagnosis.61 An alternative explanation is the “female protective effect”62 that posits that women are less likely to exhibit the same degree of behavioral autistic characteristics compared with male counterparts, and requires heightened genetic and environmental “risk” to do so. It is worth acknowledging here that there is very little evidence to support the idea of sexually dimorphic neurology in humans.63

More recently, the disjoint between acknowledging limiting diagnostic criteria (and importantly, the interpretations of those criteria), while also acknowledging population-based underdiagnosis, has led to the proposal of the “Female Autism Phenotype,”56 which posits that autistic women display a “female-specific” presentation of autism, of which masking may be a core aspect. Although much of the current research into masking does not state that masking is limited to females,9,34,64 others do suggest that females may be more likely to mask.65,66 Although it is important to recognize the different ways in which autism might present in intersection with other aspects of a person's identity and socialization, the labeling of this as “female autism” is likely to lead to more confusion in the future, which has a tangible impact outside of academia where these narratives might be perpetuated further. The idea of a female autism phenotype also fails to recognize the large number of autistic people who are outside of the gender binary,67–69 potentially creating further barriers to diagnosis and support and the perpetuation of a stigmatizing narrative.

The idea of masking as a core trait of autistic women mostly comes from what Hull et al.56 describe as a discrepancy approach to masking. Studies taking a discrepancy approach examine the difference between the self-reported internal characteristics of an autistic person and how they appear externally using behavioral assessments such as the autistic diagnostic observation schedule (ADOS).70 Studies using this method have shown that autistic females tend to show a greater difference between self-reported autistic traits and observer reports than autistic males.65,71 However, the discrepancy here may not lie with the person, but with how they are conceptualized and operationalized using the tools of measurement. In the introduction to this article, we briefly discussed the development of diagnostic tools that rely on the visibility of external behaviors and that, in turn, draw upon historical autistic stereotypes. Deconstruction of these tools from an autistic perspective72 suggests that criteria used to measure how autistic a person appears is based on nonautistic ideas of appropriate social behavior. We can consider this issue through the lens of the double empathy problem.73 Double empathy theory73 explains communication differences between autistic and nonautistic people as a “mismatch of salience”; both groups draw upon different experiential knowledge, which may lead to bidirectional breakdowns in interpreting one another. Thus judging “how autistic” a person appears based on how well they are able to perform nonautistic behavior makes little sense. The presence (or lack of presence) of a decontextualized subjectively coded behavior is not necessarily an indicator of masking. In short, it is important to recognize that a discrepancy between self-reported “autistic traits” using clinical tools and how a person appears outwardly does not necessarily relate to masking. A reliance on stereotypical (nonautistic) expectations of what an autistic person might “look like” to an observer means that a person not fitting this stereotype may be coded as masking, as opposed to a recognition that autistic people vary in their behavioral expression as much as the nonautistic population.

Reflective approaches in contrast examine masking as a set of behaviors and strategies that individuals can implement, which leads to variation in the presentation of their autistic characteristics.56 Studies using this approach have mostly found no difference between self-reported masking in males and females,1,9,34 which reinforces our previous point about stereotype and expectation. Although this reflective approach is more aligned with the idea that autistic people are the experts in their own experience, there are some issues here to take into consideration. To reflect on masking, people must be aware that they are doing it that may make it difficult to measure both the conscious and unconscious aspects. Researchers might attempt to examine this by comparing the masking experiences of people who have received earlier diagnoses with those diagnosed more recently, as well as whether community involvement impacts on how people experience masking.22

Instead of using knowledge of atypical presentation of autism to acknowledge that autistic people are likely to present in a number of different ways, we risk simply shifting the goalposts to a different set of limiting criteria. This could potentially lead to further difficulties in recognizing men/nonbinary people who present a profile that is more aligned with what is labeled “female” autism, or excluding women/nonbinary people who do not fit the “female autism” profile.74 The creation of subtypes and the language around them can also lead to additional forms of stigma manifesting.75,76 Diagnosing women with “female autism” and men with “autism” proper lends credence to the suggestion that women are not really autistic, and do not experience or understand the challenges that real autistic people (i.e., men) experience. Similar discussion can be seen with regard to the former autism/Asperger syndrome differential diagnoses, and the harmful stereotypes that are associated (i.e., those with a diagnosis of Asperger syndrome being assumed to be simply “eccentric” and having low support needs vs. the idea of someone with a diagnosis of autism lacking capacity77). Research has suggested that autistic women and girls may have a different set of challenges with regard to their social experiences,78 but that these differences are most likely driven by social environment and gendered socialization rather than diagnosis, as Rose27 points out “Autistic Women and girls don't experience different Autism, they experience different prejudice.” It is essential that we recognize the role that gender expectations and other intersectional aspects play in child development and how that impacts the development of one's sense of identity alongside the development of the mask. Again, we stress the need for the application of social theory to understanding the different ways in which an individual's autistic characteristics may present. Understanding gender prejudice, gender expectations, and gender norms experienced by an individual helps us to avoid victim blaming (i.e., shifting the spotlight away from the reliance on gendered stereotypes for diagnosis, and suggesting that those who do not fit with normative expectations have been missed because they are “better at hiding their autism”). We need to be clear when we examine masking that we are not conflating masking, and a person simply not fitting with a stereotyped idea of what autism should “look like.”

Beyond Gender: Future Directions in Masking Research

One possible consideration that might provide a more meaningful understanding of how autistic characteristics manifest across individuals is that of internalizing versus externalizing. Internalizing is characterized by the process of directing emotional experiences inward, that is, ruminating. Whereas externalizing is associated with the process of directing emotional experiences outward, that is, impulsivity. A person might display both internalizing and externalizing over the course of development, and across different contexts. Autistic people who are more prone to externalizing might appear to be easier to identify because of externally visible indicators, whereas autistic people who are more prone to internalizing might be more likely to “fly under the radar” for longer, or be diagnosed with things such as anxiety.56 It is important to recognize how individual characteristics may impact on the perceived visibility of autism across different people, and not conflate this with masking.

It is also possible that internalized ableism and difficulty in identifying one's own autistic traits could impact on the ability to recognize and discuss one's own masking. Internalized ableism is the absorption of negative beliefs about a particular disability and an attempt to distance oneself from that “spoiled identity.”79,80 Self-knowledge and reflection are essential for explicit discussions around masking, which leads to an unfortunate pitfall of masking research: we can only really learn about masking from the people who are aware they are doing it, when perhaps we stand to learn a lot more from those who are unaware. There are anecdotal reports from autistic people of those who, through self-acceptance, deep reflection, and working through trauma, have learnt to recognize some of the subconscious layers of masking. The impact of receiving a diagnosis later in life, in particular, can lead to the experience of reprocessing one's life history in the context of new information.81 This can make it difficult to disentangle which parts of a person's identity are truly “them,” and which parts might be a result of masking. The term “unmasking” is common in community discussions, because it is the literal representation of autistic persons taking control of their mask and being more authentically themselves. This occurs by choice, after a long process of learning about themselves introspectively, spending time among other autistic people and learning from sharing relatable experiences through outrospection and therapizing themselves in various ways.82 Botha22 examined the importance of autistic community connectedness (ACC) in providing a buffer against the effects of minority stress. They found that ACC related to an improved sense of well-being, however, aspects of ACC impacted people in different ways. Political connectedness, for example, can help to reframe the way in which someone views themselves and reduces internalized stigma by showing individuals that they are not “alone.” Further work into how ACC impacts on “unmasking” is needed to expand our understanding of how autistic community involvement and support can help to mitigate the negative effects of masking and help people to minimize and move past internalized ableism.

It is also important that we are able to define what constitutes masking and related concepts clearly, particularly given the impact this could have on the diagnostic process as it currently stands. Diagnosis is still enshrined in the idea of being able to identify clinically defined autistic behavior during the diagnostic process. It is important to recognize that autistic persons expressing autistic characteristics in a way that intersects with their individual identity are not necessarily masking just because it does not fit with a stereotyped idea of what autism looks like to an external observer. This does not mean that they are expressing a different kind of autism, or that they are “hiding” their autistic traits under seemingly “normal” interests. Likewise, masking can impact on how a person might appear to observers, and differentiating these presentations is no easy job. Thus, clinicians need to be aware that (a) autism does not “look” like one thing and (b) that some people might mask during the diagnostic process, but also that (c) b is not always the cause of a. This is not an easy problem to solve (i.e., coming up with a standardized notion of masking that one might examine using a psychometric measure during the diagnostic process), but can be mitigated to some degree by ensuring that clinicians are aware of these issues and receive adequate training and continued professional development around autism from those who understand these concepts.

In addition to understanding how masking might look, the role of alexithymia should be considered in the discussion of how masking feels. What may appear to be an “if X then Y” statement (i.e., X happened, so I started to do Y as a response) might frame a trauma response3 as a deliberate cognitive strategy due to difficulty in integrating the emotional aspect of experiences that led up to that point. Lawson3 recently stressed the consideration of social threat in masking, and potential ways to investigate this without framing masking as a deceitful or deliberate process. This also highlights the importance of including autistic people at all stages of autism research. Differing tacit interpretations of a statement due to positionality (i.e., drawing on different experiential knowledge, which could lead to differing interpretations to an original intended meaning) may be impacted by the double empathy problem31,73 and might be mitigated by including autistic people within a research team, particularly when working with qualitative data.

Future research may want to examine the relationship between masking, identification of one's own “autistic traits,” and alexithymia to understand how complex interactions between the three might impact on how masking manifests. It is also important to explore trauma that can arise from lifelong stigma experienced by autistic people, and how this can contribute to the development of masking across the lifespan from childhood through to adulthood in relation to additional intersecting factors (e.g., co-occurring identified and unidentified disabilities/neurodivergence, race, and socioeconomic status), which produce and interact with the stigma that they have experienced.

We might also want to consider the developmental aspects of masking in greater detail, particularly in relation to the internalized ableism and stigma previously discussed. Researchers have started to examine masking in adolescents,83,84 adding to our understanding of masking across the lifespan. We may also want to consider the experiences of parents. Many parents of autistic children only realize that they are themselves autistic once their child has gone through the diagnostic process.31,85,86 It is possible that masking in these families might also constitute a learned behavior, passed from parent to child. Researchers may want to examine whether parents of autistic children report engaging in masking (or similar identity management behavior), and what the motivations behind this might be.

Finally, researchers may want to examine whether there are aspects of masking that autistic people feel are beneficial or have an overall positive impact on their well-being. Although we have mostly focused on the negative side of masking in this article, it is possible that many people view masking as part of a viable social strategy.

Conclusion

We suggest that future research considers masking as a multidimensional fully interactive construct. To start, masking research needs to be fully grounded in social theory that acknowledges the role that the social environment and collective norms have upon the autistic person. Applying a social lens acknowledges that autistic people are social beings that do not develop in a vacuum. Moreover, masking should be considered in terms of its process; we might think of masking like the process of rock formation. What we see is the rock face, akin to the externally visible strategies that one might use to mask, for example, making eye contact and mimicking facial expressions. But these strategies have been molded over time, transformed by pressure, building up layer upon layer to create what is seen by the observer. Future research should consider the role of environment and context in masking, the outside pressures that led to the initial development, and the impact that this has had upon the individual. It should also take into account the developmental trajectory of masking, and the role that time and trauma play in the development of the mask, as well as the intersection between autism and other aspects of a person's identity (such as gender or race/ethnicity). The interaction between these processes and outcomes is likely to be an essential factor in understanding what can be done to provide better support for those whose mental health is negatively impacted by masking.

Authorship Confirmation Statement

A.P. and K.R. conceptualized and wrote this article. Both authors have reviewed and approved this article submission. The article has been submitted solely to Autism in Adulthood.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

The authors did not receive any funding for this study.

References

- 1. Hull L, Petrides KV, Allison C, et al. “Putting on my best normal”: Social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(8):2519–2534. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Livingston LA, Happé F. Conceptualising compensation in neurodevelopmental disorders: Reflections from autism spectrum disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;80:729–742. DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lawson WB. Adaptive morphing and coping with social threat in autism: An autistic perspective. J Intellectual Disability Treat Diagnosis and Treatment. 2020;8(8):519–526. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Livingston LA, Shah P, Milner V, Happé F. Quantifying compensatory strategies in adults with and without diagnosed autism. Mol Autism. 2020;11(15). DOI: 10.1186/s13229-019-0308-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Milton D, Sims T. How is a sense of well-being and belonging constructed in the accounts of autistic adults? Disability Soc. 2016;31(4):520–534. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rose K. Masking: I am not OK. 2018. https://theautisticadvocate.com/2018/07/masking-i-am-not-ok/ (accessed June 28, 2020).

- 7. Willey LH. Pretending to Be Normal: Living with Asperger's Syndrome (Autism Spectrum Disorder) Expanded Edition. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bargiela S, Steward R, Mandy W. The experiences of late-diagnosed women with autism spectrum conditions: An investigation of the female autism phenotype. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(10):3281–3294. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-016-2872-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cassidy SA, Gould K, Townsend E, Pelton M, Robertson AE, Rodgers J. Is camouflaging autistic traits associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviours? Expanding the interpersonal psychological theory of suicide in an undergraduate student sample. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;50(10):3638–3648. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-019-04323-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Raymaker DM, Teo AR, Steckler NA, et al. “Having all of your internal resources exhausted beyond measure and being left with no clean-up crew”: Defining autistic burnout. Autism Adulthood. 2020;2(2):132–143. DOI: 10.1089/aut.2019.0079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kapp SK, Gillespie-Lynch K, Sherman LE, Hutman T. Deficit, difference, or both? Autism and neurodiversity. Dev Psychol. 2013;49(1):59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Asperger H. Autistic psychopathy in children. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankenheiten. 1944;117:76–136. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kanner L. Early infantile autism. J Pediatr. 1944;25(3):211–217. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-3476(44)80156-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kapp S. How social deficit models exacerbate the medical model: Autism as case in point. Autism Policy Pract. 2019;2(1):3–28. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chown N, Leatherland J. Can a person be ‘a bit autistic’? A response to Francesca Happé and Uta Frith. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-020-04541-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mandy W, Pellicano L, St Pourcain B, Skuse D, Heron J. The development of autistic social traits across childhood and adolescence in males and females. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(11):1143–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rose K, Vivian S. Regarding the use of dehumanising rhetoric. 2020. https://theautisticadvocate.com/2020/02/regarding-the-use-of-dehumanising-rhetoric/ (accessed June 28, 2020).

- 18. Gernsbacher MA. On not being human. APS Obs. 2007;20(2):5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cowen T. Autism as academic paradigm. The chronicle of higher education. 2009. https://www.chronicle.com/article/autism-as-academic-paradigm/ (accessed September 1, 2020).

- 20. Botha M, Frost DM. Extending the minority stress model to understand mental health problems experienced by the autistic population. Soc Ment Health. 2020;10(1):20–34. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. London: Penguin Books; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Botha M. Autistic community connectedness as a buffer against the effects of minority stress. [Doctoral Thesis]. Surrey, United Kingdom. University of Surrey. 2020. http://epubs.surrey.ac.uk/854098/7/Autistic Community Connectedness as a Buffer Against Minority Stress - M Botha.pdf

- 23. Milton D, Moon L. The normalisation agenda and the psycho-emotional disablement of autistic people. Autonomy Crit J Interdiscip Autism Stud. 2012;1(1). [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rose K. An autistic invalidation. 2018. https://theautisticadvocate.com/2018/09/an-autistic-invalidation/ (accessed June 28, 2020).

- 25. Cage E, Di Monaco J, Newell V. Understanding, attitudes and dehumanisation towards autistic people. Autism. 2019;23(6):1373–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wood C, Freeth M. Students' stereotypes of autism. J Educ Issues. 2016;2(2):131–140. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rose K. How to hide your autism. In: Star Institute for Sensory Processing. STAR Institute; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sasson NJ, Faso DJ, Nugent J, Lovell S, Kennedy DP, Grossman RB. Neurotypical peers are less willing to interact with those with autism based on thin slice judgments. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):40700. DOI: 10.1038/srep40700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Griffiths S, Allison C, Kenny R, Holt R, Smith P, Baron-Cohen S. The vulnerability experiences quotient (VEQ): A study of vulnerability, mental health and life satisfaction in autistic adults. Autism Res. 2019;12(10):1516–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lung F-W, Shu B-C, Chiang T-L, Lin S-J. Prevalence of bullying and perceived happiness in adolescents with learning disability, intellectual disability, ADHD, and autism spectrum disorder: In the Taiwan Birth Cohort Pilot Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(6):e14483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Milton D. A Mismatch of Salience: Explorations of the Nature of Autism from Theory to Practice. Hove, United Kingdom: Pavilion Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Botha M, Dibb B, Frost DM. “Autism is me”: An investigation of how autistic individuals make sense of autism and stigma. 2020. DOI: 10.31219/osf.io/gv2mw. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schneid I, Raz AE. The mask of autism: Social camouflaging and impression management as coping/normalization from the perspectives of autistic adults. Soc Sci Med. 2020;248:112826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cage E, Troxell-Whitman Z. Understanding the reasons, contexts and costs of camouflaging for autistic adults. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(5):1899–1911. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-018-03878-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Blumer H. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. California: University of California Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bem DJ. Self-perception theory. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 1972;6(1):1–62. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mead GH. Taking the role of the other. In: Morris C.W, ed. Mind, Self, and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1934;253–257. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Higgins ET. Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychol Rev. 1987;94(3):319–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Goffman E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. 1959. Garden City; Doubleday & Company, NY; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Baron-Cohen S. Mindblindness: An Essay on Autism and Theory of Mind. London. MIT press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chevallier C, Kohls G, Troiani V, Brodkin ES, Schultz RT. The social motivation theory of autism. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16(4):231–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Livingston LA, Shah P, Happé F. Compensation in autism is not consistent with social motivation theory. Behav Brain Sci. 2019;42. DOI: 10.1017/s0140525x18002388 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Scheepers D, Ellemers N. Social identity theory BT. In: Sassenberg K, Vliek MLW, eds. Social Psychology in Action: Evidence-Based Interventions from Theory to Practice. Springer International Publishing; 2019;129–143. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tajfel H, Turner JC, Austin WG, Worchel S. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Hatch MJ, Schultz M, eds. Organizational Identity: A Reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1979;56–65. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Murray D, Lesser M, Lawson W. Attention, monotropism and the diagnostic criteria for autism. Autism. 2005;9(2):139–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Milton DEM. Disposable dispositions: Reflections upon the work of Iris Marion Young in relation to the social oppression of autistic people. Disability Soc. 2016;31(10):1403–1407. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Du Bois WEB. Strivings of the negro people. The Atlantic. 1897. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1897/08/strivings-of-the-negro-people/305446/ (accessed July 13, 2020).

- 48. Crenshaw KW. On Intersectionality: Essential Writings. New York. The New Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Festinger L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Vol 2. Stanford. Stanford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ragins BR. Disclosure disconnects: Antecedents and consequences of disclosing invisible stigmas across life domains. Acad Manag Rev. 2008;33(1):194–215. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kinnaird E, Stewart C, Tchanturia K. Investigating alexithymia in autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;55:80–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fulton R, Reardon E, Kate R, Jones R. Sensory Trauma: Autism, Sensory Difference and the Daily Experience of Fear. Autism Wellbeing CIC, South-west Wales; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kapp SK, Steward R, Crane L, et al. ‘People should be allowed to do what they like’: Autistic adults' views and experiences of stimming. Autism. 2019;23(7):1782–1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hochschild AR. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. California: University of California Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Samuel T, Verity C, Eli G, et al. Autism identification across ethnic groups: A narrative review. Adv Autism. 2020. DOI: 10.1108/AIA-03-2020-0017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hull L, Petrides KV, Mandy W. The female autism phenotype and camouflaging: A narrative review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2020. DOI: 10.1007/s40489-020-00197-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lord C, Brugha TS, Charman T, et al. Autism spectrum disorder. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2020;6(1):1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mottron L, Bzdok D. Autism spectrum heterogeneity: Fact or artifact? Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:3178–3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Williams D. Autism—An Inside-Out Approach: An Innovative Look at the Mechanics of ’Autism'and Its Developmental ’Cousins'. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gould J. Towards understanding the under-recognition of girls and women on the autism spectrum. Autism. 2017;21(6):703–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Baron-Cohen S. The extreme male brain theory of autism. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002;6(6):248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Robinson EB, Lichtenstein P, Anckarsäter H, Happé F, Ronald A. Examining and interpreting the female protective effect against autistic behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(13):5258–5262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hodgetts S, Hausmann M. Sex/gender differences in the human brain. In: Koob GF, Salla SD, eds. Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology. Elsevier Science; 2020;1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hull L, Lai M-C, Baron-Cohen S, et al. Gender differences in self-reported camouflaging in autistic and non-autistic adults. Autism. 2020;24(2):352–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lai M-C, Lombardo MV, Ruigrok AN, et al. Quantifying and exploring camouflaging in men and women with autism. Autism. 2017;21(6):690–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tubío-Fungueiriño M, Cruz S, Sampaio A, Carracedo A, Fernández-Prieto M. Social camouflaging in females with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020. 10.1007/s10803-020-04695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cooper K, Smith LGE, Russell AJ. Gender identity in autism: Sex differences in social affiliation with gender groups. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(12):3995–4006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Dewinter J, De Graaf H, Begeer S. Sexual orientation, gender identity, and romantic relationships in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(9):2927–2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hillier A, Gallop N, Mendes E, et al. LGBTQ+ and autism spectrum disorder: Experiences and challenges. Int J Transgender Health. 2020;21(1):98–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore P, Risi S, Gotham K, Bishop S. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, (ADOS-2) Modules 1–4. 2012.

- 71. Lai M-C, Lombardo MV, Chakrabarti B, et al. Neural self-representation in autistic women and association with ‘compensatory camouflaging.’ Autism. 2019;23(5):1210–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Timimi S, Milton D, Bovell V, Kapp S, Russell G. Deconstructing diagnosis: Four commentaries on a diagnostic tool to assess individuals for autism spectrum disorders. Autonomy (Birm). 2019;1(6):AR26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Milton DEM. On the ontological status of autism: The ‘double empathy problem.’ Disability Soc. 2012;27(6):883–887. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Strang JF, van der Miesen AIR, Caplan R, Hughes C, daVanport S, Lai M-C. Both sex- and gender-related factors should be considered in autism research and clinical practice. Autism. 2020;24(3):539–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Botha M, Hanlon J, Williams G. Does language matter? Identity-first versus person-first language use in autism research: A response to Vivanti. 2020. 10.31219/osf.io/75n83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bottema-Beutel K, Kapp SK, Lester JN, Sasson NJ, Hand BN. Avoiding ableist language: Suggestions for autism researchers. Autism Adulthood. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77. Kenny L, Hattersley C, Molins B, Buckley C, Povey C, Pellicano E. Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism. 2016;20(4):442–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sedgewick F, Hill V, Pellicano E. ‘It's different for girls’: Gender differences in the friendships and conflict of autistic and neurotypical adolescents. Autism. 2018;23(5):1119–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Woods R. Exploring how the social model of disability can be re-invigorated for autism: In response to Jonathan Levitt. Disability Soc. 2017;32(7):1090–1095. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Campbell FK. Internalised ableism: The tyranny within BT. In: Campbell FK, ed. Contours of Ableism: The Production of Disability and Abledness. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan; 2009:16–29. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Leedham A, Thompson AR, Smith R, Freeth M. ‘I was exhausted trying to figure it out’: The experiences of females receiving an autism diagnosis in middle to late adulthood. Autism. 2020;24(1):135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Rose K. An autistic identity. 2019. https://theautisticadvocate.com/2019/03/an-autistic-identity/ (accessed June 28, 2020.)

- 83. Wood-Downie H, Wong B, Kovshoff H, Mandy W, Hull L, Hadwin JA. Sex/gender differences in camouflaging in children and adolescents with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020. [Epub ahead of Print]. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04615-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Jorgenson C, Lewis T, Rose C, Kanne S. Social camouflaging in autistic and neurotypical adolescents: A pilot study of differences by sex and diagnosis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(12):4344–4355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Montague A. How my son's autism diagnosis led to my own. 2018. https://www.scarymommy.com/how-my-sons-autism-diagnosis-led-to-my-own/ (accessed October 14, 2020).

- 86. Siegler A. My son's diagnosis lead to my own. 2019. https://www.fierceautie.com/2019/02/my-sons-diagnosis-lead-to-my-own.html?m=1 (accessed October 16, 2020).