Abstract

Background:

Communication via the internet is a regular feature of everyday interactions for most people, including autistic people. Researchers have investigated how autistic people use information and communication technology (ICT) since the early 2000s. However, no systematic review has been conducted to summarize findings.

Objective:

This study aims to review existing evidence presented by studies about how autistic people use ICT to communicate and provide a framework for understanding contributions, gaps, and opportunities for this literature.

Methods:

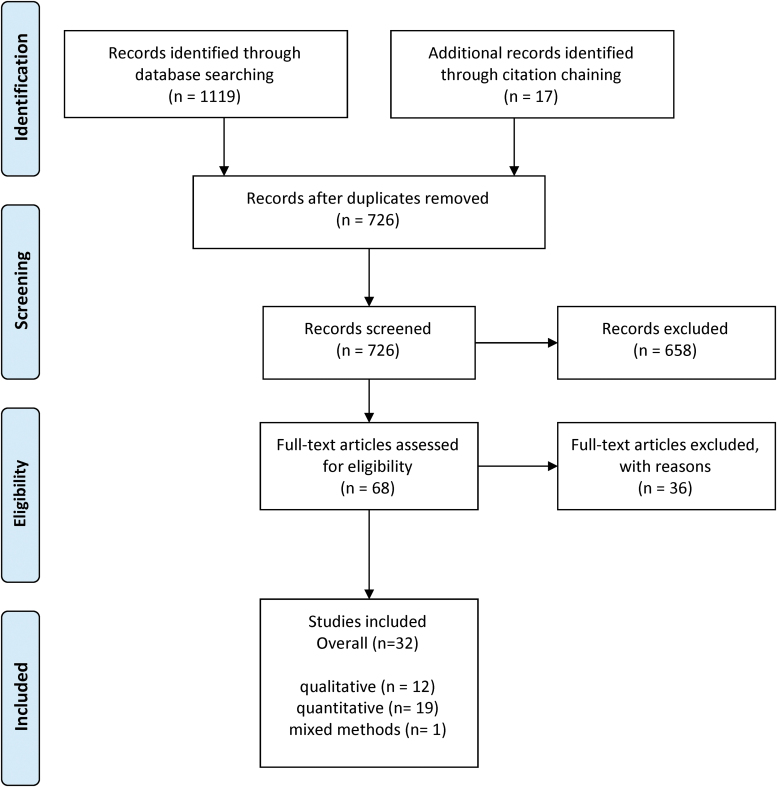

Guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses(PRISMA) statement, we conducted a comprehensive review across five databases, searching for studies investigating how autistic youth and adults use ICT to communicate. Authors reviewed the articles for inclusion and assessed methodological quality.

Results:

Thirty-two studies met the eligibility criteria, including 19 quantitative studies, 12 qualitative studies, and 1 mixed methods study, with data from 3026 autistic youth (n = 9 studies) and adults (n = 23 studies). Ratings suggest that the evidence base is emergent. Underrepresented groups in the sample included autistic women, transgendered autistic people, non-White autistic people, low income autistic people, and minimally speaking and/or autistic adults with co-occurring intellectual disability. Three main themes emerged, including variation in ICT communication use among autistic youth and adults, benefits and drawbacks experienced during ICT communication use, and the engagement of autistic youth and adults in the online autism community.

Conclusions:

Further exploration of the positive social capital that autistic people gain participating in online autism communities would allow for the development of strengths-based interventions. Additional research on how autistic people navigate sexuality and ICTs is needed to identify mechanisms for reducing vulnerability online. Additional scholarship about underrepresented groups is needed to investigate and confirm findings regarding ICT communication use for gender, racial, and socioeconomic minority groups.

Lay summary

What was the purpose of this study?

People use the internet to communicate (talk and connect) with one another. Some research has found that autistic people may prefer to communicate using the internet instead of in person. Over the past 20 years, there has been research about how autistic people use the internet. To understand what research has discovered so far, we collected published research about how autistic youth and adults use the internet to communicate.

What did the researchers do?

We used scientific best practices as described in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to collect research about how autistic people us the internet to communicate. We included research that uses words (qualitative research) and numbers (quantitative research). First, we searched several places that list research studies to find research on autistic people and the internet. Then, we removed research that did not fit what we were looking for (our criteria). Finally, we then read the full articles, collected their most important findings, and looked for patterns.

What do these findings add to what is already known?

Thirty-two studies met our criteria, including 19 studies that used closed-ended survey questions that tested relationships between variables, 12 studies that used open-ended interviews and looked for patterns and connections among participants, and 1 mixed methods study. In total, 3026 autistic youth of ages 10–17 years (number of participants = 9 studies) and adults (number of participants = 23 studies) participated in these 32 studies. We rated each of the 32 studies for quality and learned that the evidence base is preliminary, meaning that more rigorous high-quality studies are needed before we can be confident in the findings. We found three main themes: (1) differences in the ways that autistic youth and adults used the internet to communicate, (2) benefits and drawbacks experienced when using the internet to communicate, and (3) the engagement of autistic youth and adults in the online autism community. Some of the benefits of social media for autistic people include more control over how they talk and engage with others online and a greater sense of calm during interactions. However, findings suggest some drawbacks for autistic people, including continued feelings of loneliness and the desire for in-person friendships. Social media provides opportunities for autistic people to find others on the autism spectrum and form a stronger identity as part of the autism community. The study also showed that there is little research about autistic women, autistic transgender people, autistic racial/ethnic minorities, or autistic people from lower socioeconomic status (SES) groups.

What are potential weaknesses of this study?

We only included research in scientific articles, and there may be useful information on this topic in books, student research, or online.

How will these findings help young adults on the autism spectrum now or in the future?

This study can help identify gaps and opportunities for new research, support the importance of online autistic communities, and suggest possible training opportunities about how to support autistic people when they use the internet for communication.

Keywords: autism community, internet communication, social media, autism spectrum disorders, social interactions

Introduction

The proliferation of information and communication technologies (ICTs), particularly 21st-century social media, throughout modern society has changed how people communicate and engage with information.1,2 Academic researchers in numerous fields have been seeking to understand how these changes have impacted specific populations, including people on the autism spectrum. Anecdotally and in popular culture, ICTs seem to have had a tremendous impact on autistic people and autism communities. This may be because of the way ICTs mediate communication. Autism is characterized by differences in face-to-face social communication, however, ICTs may serve as buffers for autistic people, allowing communication that does not require face-to-face interactions. People on the autism spectrum also have restricted repetitive patterns of interests or behavior, and ICTs may allow them to make connections and find outlets for their interests that are unbounded by their geographic location. Internet forums also provide opportunities to further develop focal interests. Currently, the topic of internet communication technologies has increased in importance, due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, presenting new challenges and perhaps stronger opportunities for ICT engagement by autistic people.

Emerging research suggests that autistic people have a greater preference for using social media than nonautistic people.3 Burke et al3 explored how ICT can be challenging and beneficial specifically for social support among autistic people. Findings suggest that many autistic people seek social connections in their lives and use ICT as part of their successful supportive relationships. Brownlow et al.4 suggest that social networking sites, when adapted to the needs of autistic people, can create “safe spaces”5 where autistic people can establish and maintain friendships. In particular, autistic people found ICT useful for initiating contact with new people. However, Burke et al.3 do not regard ICT as a social panacea for autistic people. Several participants preferred in-person contact for certain social interactions even while describing in-person contact as requiring greater effort and strain, and they did not feel as connected with other people when communicating through text-based modalities alone. Autistic participants in this study also reported that online friendships feel less secure, as they can end abruptly and without explanation. In addition, ICT may intensify issues of trust, disclosure, and inflexible thinking in autistic people, making it difficult for some to maintain relationships. Based on this, ICTs represent both benefits and downsides that people on the autism spectrum must navigate to access these ubiquitous platforms for connection.

To better engage and support autistic people in their communication at any stage of life, researchers and service providers can work to better understand how autistic people are using ICTs for communication. This article presents a systematic review of the research on how autistic youth and adults use ICTs for communication. This review is meant to systematically review this body of literature and identify areas where further research is needed.

Methods

An initial foray into the literature at the intersection of ICTs and autism showed a diverse body of work, suggesting that a systematic review may be useful. Systematic literature reviews address specific questions by collecting secondary data, critically assessing research studies and synthesizing qualitative or quantitative findings. We performed a systematic review using the framework outlined by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (see online supplemental material for Supplement Table S2 PRISMA checklist)6, which involves a comprehensive checklist. The following question guided our inquiry: “How do youth and adults on the autism spectrum use the internet to communicate with others?” Principally, we sought to understand and lend coherence to the research that has already been done in this area, but we also aimed to identify avenues for further research at the intersection of ICTs and autism.

Information sources and article management

Three authors and a research assistant from the study team searched six electronic databases (CINAHL, ACM, PsycINFO, Pubmed, Web of Science, Ovid) for the terms internet or social media or computer-mediated communication and autism or Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or pervasive developmental disorder, with the search syntax: [(autis* OR “pervasive developmental disorder” OR pdd OR asd) AND (internet OR “social media” OR “computer-mediated communication” OR ICT OR ict)] on May 2, 2020 (Fig. 1). The study team retrieved a total of 1119 studies. After retrieving relevant articles, the research assistant conducted citation chaining. This involved using Google Scholar to trace articles citing and cited in the articles previously retrieved. Citation chaining proceeded iteratively (n = 17 studies).

FIG. 1.

Study flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Screening and selection process

The study team removed combined and duplicated studies and 726 studies remained after the removal of duplicated studies. Next, the study team screened studies for eligibility and excluded 658 studies. The study team then assessed a total of 68 full-text articles for eligibility and excluded 36 articles with reasons. Three authors and the research assistant extracted and coded data from the final 32 studies for patterns. The authors resolved disagreements in assignment or description of codes through discussion and final consensus.

Included study characteristics

Authors assessed eligibility for inclusion based on certain criteria. Included studies met the following criteria: the study primarily focused on use of the internet by youth and adults on the spectrum, at the level of the individual or group (rather than, e.g., brain imaging); the study focused on autistic people themselves (rather than, e.g., their caretakers); the study reported primary research in qualitative or quantitative methodology. Excluded studies included studies written in languages other than English; study methodologies where the internet was part of, but not the object of the study (e.g., internet-based trials); studies where the internet served as a forum for content analysis rather than the object of study (e.g., looking at internet forums as an approach to a different topic, such as vaccines); studies that focused on autistic children [rather than adolescents (14+) or adults (18+)]; and studies that examined general media use or psychological development. When raters disagreed, they discussed eligibility, agreeing on the inclusion of 32 articles, with 12 qualitative studies, 19 quantitative studies, and 1 mixed methods study. Data included findings from 3026 autistic youth (n = 9 studies) and adults (n = 23 studies).

Data extraction and article coding

Data extraction was conducted by authors using a data extraction form designed by the full team. Data included lead author, year of publication, study inclusion criteria, sample size, participant characteristics (e.g., how authors described autism diagnostic information for sample), age range, gender, SES if reported, race/ethnicity, country, research design and sources of data, purpose, and key findings. Extracted data are described and synthesized below.

Authors constructed themes and subthemes of ICT engagements through consensus. Authors resolved disagreements in assignment or description of codes using discussion and final consensus. The constant comparative method7 involving constructing themes by examining commonalities and distinguishing characteristics of codes was used to identify themes and subthemes reported in the results.

Evidence ratings

For all articles, two authors independently rated level of evidence on a scale outlined in Harbour and Miller8, from 1++ (highest quality, e.g., systematic reviews of RCTs) to 4 (expert opinion). Ratings of studies included in this review ranged from 2+ (well-conducted case–control study) to 3 (nonanalytic studies, e.g., case reports). (See also Appendix Table 1 for extracted data by study and Supplement Table S1 for an extended table in the online supplementary documents).

Results

The literature on how autistic youth and adults use ICTs for communication revolves around three main topics: (1) variation in the use of ICT by autistic people for communication, (2) benefits and drawbacks for autistic people when using ICT for communication, and (3) the role of ICT in the formation and engagement of autistic people in the online autism community. A synthesis of the findings regarding these three topics is presented in the sections below. All studies are cited in the reference section of this article and the Appendix Table 1 and Supplement Table S1 in the supplement provide summary tables with identifying citation numbers.

Table 1.

Patterns of Use of Information and Communication Technologies among Autistic People

| Variation in Use of ICTs among People on the Autism Spectrum | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Subcategory | Findings | References |

| Demographics | |||

| Age | Older Youth | Odds of no e-mail or chat were significantly lower for older youths | 11 |

| Gender | Boys | Two-thirds of autistic boys had access to computer or home video game console, tablet, or smart phone // Autistic boys less likely to have smart phone than other boys // Autistic boys more likely to play video games by themselves than controls (vs. with friends or in multi-player) //Autistic boys showed less ICT use than controls, and 21% did not use ICT at all despite access (100% of controls did) | 33 |

| Girls | Autistic girls were more likely than males to engage in Internet browsing, email, or chat | 45,11 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | African American | African American autistic people /other non-White racial/ethnic minority groups less likely to use email or chat rooms | 11 |

| Hispanic/ Latinx | Hispanic autistic youth more likely to engage in Internet browsing, email, chat vs. non-Hispanic youth | 11 | |

| SES | SES Comparison | Low SES w/o internet access could be left out; people from low SES backgrounds had less computer use vs. those from higher SES backgrounds | 45 |

| Autistic spectrum variation | |||

| Cognitive Level | Asperger's/ “High Functioning” | Adolescents with Asperger's used social media less than NT/ID control // HF adults spend more time on computer mediated communication than control // HF adults more positive about computer mediated communication than control // odds of no e-mail or chat were significantly lower for youth with higher functional cognitive skills //Internet browsing, e-mail, or chat was more likely in higher cognitive skills | 11,25,10 |

| ICT Preferences | |||

| Communication Interfaces | Video calling | Video calling causes stress for autistic adults | 9 |

| Devices | Prefer personal computers to mobile phones // use tablets/computers/mobiles similarly to NT/ID others | 10 | |

| Asynchronous written communication | Prefer anonymous media (e.g. discussion boards) // reduced need for nonverbal communication skills // people expressed multiple different preferences (syncs vs. asynchronous) with various benefits/drawbacks for each format. | 22,11,12 | |

| Synchronous written communication | Odds of no e-mail or chat were significantly lower for youths with a computer in the home //Used email and chat far less than other media and compared to control groups (except MR) //Internet browsing, e-mail, or chat was more likely in computer in home | 11 | |

| Social Media Use | Almost half of Facebook use by autistic community specified geographic location of members (43%) // most participants used identity first language //over half of Facebook use by autistic community was for family and parents (57%), 23% for autistic people and 10% for women // Facebook use by autistic community included support (60%), social companionship (16%), advocacy (15.8%), treatments (5%), sales (1%) fundraising (.8%), | 13 | |

| Media use | Spend more time using non-social media than for media for social purposes | 11 | |

| Social Networking Sites | Preference for social networking sites | 35 | |

| Other types of engagement | Video Games | Autistic adults spend more time playing video games, higher % of free time playing video games | 54 |

| Sexuality and ICT Use | |||

| Sexual Engagement | online dating profiles | Online dating profiles of autistic males combine desirable and undesirable characteristics (Shy geek, likes music technology and gaming) // online dating profiles of autistic males use characteristics that are stereotypically considered negative - gamer, geek// online dating profiles identified ideal match attributes they did not want- negative tone // online dating profiles self-identified as autistic and included a description of what autism is for them in the about me section | 16 |

| Types of Sexual Engagement | Online sexual activity (information seeking/chatting and solitary arousal and partner arousal) of autistic adults common (2/3 of sample engaged in at least one of 3 types) but infrequent // camera sex | 15 | |

| Age | Online sexual information seeking/chatting of autistic adults common among people in their 20s | 15 | |

| Gender | Online sexual activity (information seeking/chatting and solitary arousal) of autistic men more frequent and more prevalent than women | 15 | |

| Sexual minority identification | LGBTQ //online sexual partner arousal more common among sexual -minority individuals | 15 | |

| Parental regulation | Devices/access taken away for practices like sexting or sexual webcam use | 51 | |

ICTs, information and communication technologies.

Patterns of use of ICTs of autistic people

It is well established that autistic people use multiple types of ICTs to communicate, include social media, email, texting, and other digital forms of communication. Several researchers have found ICTs to be well suited to the communicative needs and preferences of autistic people. Four overarching themes emerged: (1) demographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, and SES); (2) autistic spectrum variation (Asperger's and cognitive functioning); (3) ICT preferences (communication interfaces, social media uses, and video game engagement); and (4) sexual engagement (seeking sexual partners and engaging in sexual participation). Below we have highlighted the main points that surfaced in the codes; see Table 1 for full breakdown of subthemes.

While underrepresented groups in the sample included autistic women, transgendered autistic people, non-White autistic people, low-income autistic people, and minimally speaking and/or autistic adults with co-occurring intellectual disability (ID) (Appendix Table A1), preliminary findings from the few articles that included such groups suggest variation across gender, race/ethnicity, and SES, supporting a call for further research to understanding underlying inequalities in access to ICTs for communication.

Results suggested that autistic people had different ICT preferences.9-12 Some studies indicated preference for certain interfaces over others (i.e., personal computers as compared with mobile phones), while other studies suggested mixed preferences (i.e., synchronous vs. asynchronous technologies). Important dimensions to participation in social media use by autistic people included geographic location and support.13

Sexual fulfillment and romantic connection have always been large drivers of internet use, so it is not surprising that research on autistic people's internet-based communication would include sexuality and relationships.14,15 Autistic people use the internet for obtaining information about sexuality, for sexual chatting and arousal, for accessing lesbian, gay, bisexual, pansexual, transgender, genderqueer, queer, intersexed, agender, asexual, and ally community (LGBTQIA+), and for seeking in-person sexual and romantic connections through dating apps.16 Using the internet as a tool for sexual and romantic fulfillment may be especially important for autistic people, many of whom may not have access to effective sexuality education or services17-20 or who may find it easier to find partners online through venues organized around shared interests in the relative comfort and security of home.21

Benefits and drawbacks for ICT engagement of autistic people

Autistic youth and adults experienced both benefits and drawbacks when engaging in ICTs for communication. Two overarching themes emerged: (1) Benefits Gained thru Social Interactions on ICT (social skills development, positive social capital, create and maintain social connections, and mental health) and (2) Drawbacks Experienced thru Social Interactions on ICT (negative social capital, behavioral regulation, and mental health). Below we have highlighted the main points that surfaced in the codes; see Table 2 for full breakdown of subthemes.

Table 2.

Benefits and Drawbacks for Information and Communication Technology Engagement of Autistic People

| Types of Benefits |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Subcategories | Findings | References |

| Benefits Gained thru Social Interactions on ICT | |||

| Social Skills Development | Learning about building relationships | Learn about relationships // learn about explicit rules and moderation for groups // can 'lurk' and learn about group dynamics, choose level of engagement // help develop social skills // learn to communicate more correctly online than face to face | 37,45,12 |

| Positive Social capital | Expertise sharing | Enjoy sharing expertise | 36 |

| Social media | Facebook sites provide social networking opportunities for autistic people // social media use by autistic adults in moderation (Facebook most frequently used) was associated with happiness | 26,51 | |

| Social Support | More social support | 51 | |

| Social Satisfaction | HF adults report higher levels of online social life satisfaction than control // sense of belonging | 37,25 | |

| Support for work tasks | Using messenger to prepare for school or work | 51 | |

| Create and Maintain Social Connections | Helpful technical aspects of ICT to sustain interactions | Reduction of stimuli // increased distance // greater sense of objectivity // greater sense of control, safety // less small talk // increased comprehension or control of interactions // choose level of engagement // avoid “superficial, negative, or prejudiced perceptions of others” | 41,22,24,36,37,46 |

| Family relationships | Stay in touch with loved ones | 51 | |

| Friendship | More positive friendships // greater friendship security with those whom they communicate with online // expand social network/make friends // people who used social networking sites more likely to have close friends // people who used social networking sites for social engagement more likely to have closer friendship relationships | 44,51,37,46,45,56,35 | |

| Mental Health | Anxiety | Reduce anxiety/stress | 22,24,37,56 |

| Loneliness | Decrease loneliness | 22,51,37 | |

| Drawbacks Experienced thru Social Interactions on ICT | |||

| Negative Social capital | Disinformation | More susceptible to deceptive online behavior, may over-disclose and increase vulnerability | 22 |

| Social satisfaction | CMC use negatively related to life satisfaction | 25 | |

| Friendship | May inhibit 'real life' friendships, opportunities to practice face-to-face social skills // it may not always be a substitute for in-person friendships | 24 | |

| Behavioral Regulation | Addiction | 38% of participants scored as having problematic internet use, and 5% internet addiction // The prevalence of internet addiction among autistic adolescents alone, with ADHD alone and with comorbid ASD and ADHD were 10.8, 12.5, and 20.0%, respectively // autistic college students were not more at risk for internet addiction // Mean daily VG play time higher in autistic boys than controls, higher average rates of gaming disorder symptoms | 54,30,54,55, 32, 33, 34 |

| Excessive use | May fail to regulate online behavior, liberating effect, excessive time online // Pattern of tweeting with fixative characteristics, greater proportion of late night/early morning tweets | 22, 31 | |

| Financial risk | Internet risks for overspending | 31 | |

| Mental Health | Loneliness | It may not dispel feelings of loneliness // social networking sites did not decrease loneliness | 51,35 |

| Cyberbullying | “Dark” aspects of CMC, including cyberbullying, trolling and deception, may be more severe for autistic people // among autistic middle schoolers, cyberbullying victimization was positively associated with peer rejection, anxiety and depression, peer rejection moderated relationship between cyberbullying and depression // no differences in cyber bullying between Asperger group and NT/ID group | 51,52,10,38 | |

| Depression/anxiety | Problematic internet use among teens associated with higher depression/anxiety symptoms // controlling for anxiety, duration of internet use in years, and degree of parent control, only depression (and hours of daily internet use) predicted problematic internet use // higher rate of tweets with terms related to anxiety, | 32,31 | |

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ASD, Autism spectrum disorder; CMC, computer mediate communication; VG, video game.

Some of the benefits of social media for autistic people include increased control over social situations through increased distance, reduction of stimuli, and greater sense of objectivity.3,22-25 Moderate use of social media was associated with happiness.26 However, findings suggest some drawbacks for autistic people, including preliminary evidence that social media does not dispel feelings of loneliness and does not necessarily substitute for in-person friendships for all people on the autism spectrum.25,27 Relatedly, online friendships may be perceived by autistic people as less valuable than in-person friendships due to the possibility of sudden rupture,3 though this may be rooted in an antiquated conceptualization of friendship.28 Additionally, the “dark” aspects of social media, including cyberbullying, trolling and deception, may be more severe for people on the spectrum.27,29 Problematic internet use was associated with anxiety and depression and was higher among autistic youth with ADHD.30-34 However, for youth, parent monitoring was negatively associated with cyber bullying, acting as a protective factor.29

In an earlier study, Müller et al.24 reported on interviews about the social challenges and supports for autistic people. Their study did not focus on ICTs specifically but found that autistic people perceived internet-based communication as a way to reduce the stress of conversing, for example, by eliminating the possibly ambiguous factor of tone. Soon after, Benford and Standen22 explored how internet-based communication can address the communicative needs of autistic people. They conducted a grounded theory study based on interviews conducted chiefly via email. They found that ICTs held many benefits for autistic people, including delimited stimuli, flexible timing, improved clarity, expanding networks, and more explicit structure.

Mazurek35 reported on a quantitative online survey of social media use in autistic adults. Mazurek's results indicated that social media made it easier for autistic people to create and maintain friendships, partly because of the narrower range of online social cues possible online compared with in-person communication, echoing the findings of Müller et al.24 and Benford and Standen.22

The question arises of whether and how the use of ICT for communication by autistic people differs from others. Two studies of ICT have compared autistic people with nonautistic people. Gillespie-Lynch et al.36 broached this question through an online survey, finding that these groups (autistic vs. not) use and perceive ICT in different ways. Autistic people enjoyed using the internet to meet others more than nonautistic people, and to keep up with family and friends less than nonautistic people. Autistic participants spent less time in offline social activities than nonautistic participants. Autistic people perceived the benefits of ICT as increasing comprehension and control over communication and gaining access to similar others and opportunities to express their true selves.

Similarly, van der Aa et al.25 reported on a survey study comparing ICT use in autistic people versus not on the spectrum. Their findings largely corroborate those of Gillespie-Lynch et al.36 According to van der Aa et al., the features of ICT attract people on the spectrum to get online, make friends, and many report satisfactory online social lives. They found that people on the spectrum use ICT more and have more online contacts than nonautistic participants. Still, the autistic participants expressed more satisfied with their online social lives than with their offline lives.

To summarize, autistic people use ICT, possibly with a higher preference than those without ASD. This may be because of benefits that ICT offers to autistic people. Some of the benefits of ICT for autistic people include social satisfaction37 and increased control over social situations through increased distance, reduction of stimuli, and greater sense of objectivity.22,24,25,36,37 However, ICT also has drawbacks for autistic people. It may not dispel feelings of loneliness, and it may not always be a substitute for in-person friendships.25 Relatedly, online friendships may be perceived by people on the spectrum as less valuable than in-person friendships, not least because of their possibility for sudden rupture3 though this may be rooted in an antiquated conceptualization of friendship.4 In addition, the “dark” aspects of ICT, including cyberbullying, trolling, and deception, may be more severe for autistic people.29,38

ICT and the autism community

Social media provides opportunities for autistic people to find others on the autism spectrum and form a stronger identity as part of the autism community.39-43 Autistic culture, particularly as constructed online, advocates for difference, not deficit through the online construction of different “forms of life” sketched in more detail.39 One overarching theme emerged: Community dynamics (positive social capital and positive identity formation). Below we have highlighted the main points that surfaced in the codes; see Table 3 for full breakdown of the two subthemes.

Table 3.

Autism Community and Information and Communication Technology Engagement of Autistic People

| Engagement in Online Communities for Autistic People |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Subcategories | Findings | References |

| Community Dynamics on ICT | |||

| Positive Social capital | Sharing Experiences | Age groups/life stage groups: adolescents, transition, adults | 45,44,14,46 |

| Autism culture | Forming supportive “Autistic culture” // Advocating for difference, not deficit // Autism-only spaces // community discourses supported a shift from biomedical to cultural perspective // group norms that discourage “Neurotypical bashing” (#9) | ||

| Social Support | Get peer support online // Learning how to tolerate dissent | ||

| Positive Identity Formation | Belonging | Finding others with ASD and forming a strong identity as the autism community // access to similar others/those with common interests, “like-minded people” // “reclaiming symptoms” by “embracing an Aspy self” (#9) // ‘selfing’ vs. othering (#9) | 36,41,44,22, 51 |

Finding others on the autism spectrum and forming a strong identity in the autism community act as a form of positive social capital for autistic people.4,44-46 Davidson39 suggests that we understand autistic culture, particularly as constructed online, in terms of Wittgenstein's family resemblances and multiple forms of life. He advocates for the representation of autism as a difference rather than a deficit. Parsloe44 found that the autism internet community she observed allowed participants opportunities to “reclaim symptoms” by “embracing an Aspy self”44 (p.351). Instead of labeling their personal attributes as negative symptoms of autism, the internet community she observed encouraged participants to frame their differences as positive traits. Key norms established by the online forum supported “selfing”44 (p.351), and identify formation process that encouraged the internal development of a nonbinary sense of self, where autistic people no longer define themselves at not typical, but rather, as a “hybrid” identity.44 Parsloe explains that “othering is an extroverted process of disidentification”44 (p.351), whereas “selfing,” following Gulerce, emphasized the formation of a new unique whole identity.47

The internet also provides a forum for autistic people to respond to policy decisions that affect their lives. For example, Giles40 writes that when diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM5) removed “Asperger's” as a diagnosis, forum threads by people with Asperger's on the topic showed a robust community conversation, with some autistic people in support of the change and some against the change.40 Social media provides autistic people a voice and chance to form community and possibly challenge scientific classifications and methods. Jones and Meldal41 present a grounded theory study suggesting that people with Asperger's considered internet communication among people with Asperger's a key social resource. Themes of firsthand accounts presented in this article include awareness of difficulties in communication, attempts to fit in, awareness of other people with Asperger's as part of a community where they can belong, and awareness of the benefits of internet for social relationships.

Discussion

Three main themes emerged, including variation in ICT communication, benefits and drawbacks for ICT engagement, and autism community engagement by autistic people. As with many areas of research, this review showed that certain marginalized groups have been a lower priority in this research area and deserve more attention. Underrepresented groups included autistic women, transgendered autistic people, non-White autistic people, low-income autistic people, and minimally speaking and/or autistic adults with co-occurring ID (See Appendix Table 1 and Supplement Table S1). Only half of articles reported on the race/ethnicity of participants and those reporting race/ethnicities included mostly White participants. Only three articles reported engagement in ICTs for lower SES participants. Close to a third (38%) of articles reported on the ICT engagement of people with Asperger's syndrome who do not have co-occurring ID, potentially due to the untested assumption that people with ID do not use ICTs. Autistic women participated in 53% of studies as a smaller minority of participants, with the exception of one study about sexuality. No studies reported participation of gender minority or transgendered autistic people, and one-third of studies did not report on the gender of participants at all. Despite this, these few studies revealed gender differences. Autistic boys had greater access to ICTs. Autistic girls and Hispanic youth engaged more often in browsing, email, or chat functions. African American and non-White racial/ethnic minority groups were less likely to engage in email or chat rooms, and autistic people from lower SES backgrounds had less access to computers and means to engage in ICTs.

Findings should be considered preliminary, as ratings8 also suggest that the evidence base is emergent, with no RCT level studies yet conducted to control for bias and negate confounding factors. Given potential benefits of ICTs for autistic people, more rigorous research is urgently required to further investigate demographic variation, and to inform systems level changes that can overcome institutional inequalities that perpetrate racism and hamper outcomes for autistic people from minority or lower resource backgrounds.

Based on these findings, more research is needed on sexuality and ICTs to understand how people on the spectrum navigate the many benefits and risks of online life. These findings suggest it is important for autistic people to know applicable rules and social norms about internet-based sexual communication (e.g., age of consent, legal vs. illegal pornography).48 In addition to avoiding common internet scams, it is important that autistic people know how to determine whether sexual chatting is wanted versus unwanted (for both they and their partner(s)) so that they can disengage from unwanted conversations. Currently, there are few resources for autistic people to learn how to pursue sexual fulfillment lawfully and ethically on the internet that address the unique learning needs of this population.18 Research indicates that parents struggle to talk about sexuality and sexual victimization with autistic youth,49 and many parents, professionals, and educators may not realize that it is important to talk about appropriate online sexual behavior or know how to do so effectively. Resources are needed, and research partnering with autistic people to learn about challenges they face in this area and how to support them is required for the creation of effective resources. Furthermore, clinical anecdotes and published case studies suggest that online sexual victimization and inappropriate or law-breaking behavior can be problems for the autistic community, yet there is no rigorous research presenting the prevalence of such issues. Knowing the scope of the issue and whether it differs by gender, race/ethnicity, SES, and intellectual functioning would help inform the extent to which education about these topics should be proactive and widespread. Autistic people have the right to seek sexual fulfillment in consensual ways, and access to privacy to fulfill their sexual and romantic needs should be considered critical to their health and well-being.50

Findings also suggest how the COVID-19 pandemic might present new barriers and possible opportunities for autistic engagement in ICTs. Much personal and work communication has shifted to videoconferences, which could create additional stress for autistic adults.9 However, opportunities for asynchronous participation have also increased, which some research indicated as a preferred method of participation.11,12,22 The societal shift to online communication due to the COVID-19 pandemic might also increase participation and communication through social media platforms for autistic people, such as Facebook, Reddit, or Twitter. Such increased engagement can create more opportunities for shared experiences, social support, and participation in autism culture,4,44-46 as well as positive identity formation experiences due to increased access to similar others and people with shared interests.22,36,41,44,51 However, risks also could increase due to the COVID-19 pandemic, including exposure to disinformation,22 cyberbullying,10,38,51,52 mental health challenges,30 and potential excessive use,22,30,53-55 especially for autistic youth.

Limitations

Possible limitations include our narrow focus on qualitative and quantitative articles. The review does not include potentially useful research that has been published about this topic using other methodologies, such as humanistic essays, or other formats than articles, such as books, book chapters, and dissertations.

Conclusions

Strength-based approaches to build on the positive social capital that autistic people gain when participating in online autism communities require further exploration. Previous research suggests that many autistic adults use social media for the purpose of social connection, and that it is associated with better friendship quality56 and even happiness26—yet some suggest it is offline friendships rather than social media use that are associated with decreased loneliness.35 Additional research on how autistic people navigate sexuality and ICTs could identify mechanisms for reducing vulnerability online. Additional scholarship about underrepresented groups could investigate and confirm findings regarding ICT communication use for gender, racial, and socioeconomic minority groups. Further research is needed to investigate the vulnerability of autistic adults and/or co-occurring ID to abuse and exploitation online. Preliminary research suggests that socialization toward compliance, lack of access to knowledge (e.g., about sexuality), and yearning for meaningful relationships may contribute to vulnerability,57 however, more research is required to inform protective interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the research assistant, Timothy Gorichanaz, who provided important support for this publication.

Appendix

Appendix Table 1.

Summary of Articles Reviewed (Listed Alphabetically by Method with Reference Citation #)

| Author (Year) | Gender* | Race/ Ethnicity** | SES | Stated Platform*** | Level of Evidence Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Studies (N = 12) | |||||

| Abel et al. (2019)13 | NA | NA | NA | FB | 3 |

| Benford & Standen (2009)22 | NA | NA | NA | INT | 3 |

| Bertilsdotter et al. 2013)46 | NA | NA | NA | MAG, DISC | 3 |

| Brownlow & O'Dell (2006)14 | NA | NA | NA | ONLINE GRP | 3 |

| Gallup et al. (2017)55 | NA | W 100% | NA | MMO RPG | 3 |

| Gavin et al. (2019)16 | 52 M | NA | NA | DP | 3 |

| Jones & Meldal (2001)41 | NA | NA | NA | TW | 3 |

| Müller et al. (2008)24 | NA | NA | NA | INT | 3 |

| Parsloe (2015)44 | 5 F, 13 M | NA | NA | INT | 3 |

| Stendal & Balandin (2015)37 | 6 F, 4 M | W 100% | NA | FORUM | 3 |

| Zolyomi et al. (2019)9 | 1 M | NA | NA | SL | 3 |

| Hswen et al. (2019)31 | 9 F, 13 M | NA | NA | VC | 3 |

| Mixed Methods Studies (N = 1 ) | |||||

| Sallafranque-St-Louis & Normand (2017)51 | 1 F, 2 M | NA | NA | INT | 3 |

| Quantitative Methods Studies (N = 19) | |||||

| Iglesia et al. (2019)10 | 190 F, 141 M | W 90% | NA | INT | 2+ |

| Byers & Nichols (2019)15 | 8 F, 52 M | NA | NA | INT | 2+ |

| Coskun et al. (2019)30 | 16 F | W 85% | NA | VG | 2- |

| Engelhardt et al. (2017)54 | 195 F, 96 M | W 81.4% | NA | INT | 2- |

| Gillespie-Lynch et al. (2014)36 | 8 F, 23 M | NA | NA | INT, SM | 2- |

| Kawabe et al. (2019)32 | 13 F, 42 M | NA | NA | INT | 2- |

| Kowalski & Fedina (2011)52 | 18 F, 24 M | W 73% | NA | INT | 2- |

| Kuo et al. (2014)45 | 17 F, 74 M | W 98% | M$85,000 | NA | 2+ |

| Mazurek et al. (2012)11 | 142 F, 778 M | W 65.2%; AA 22.6%; O 12.2%; H 11.0% | NA | SM | 2+ |

| Mazurek (2013)35 | 51 F, 57 M | W 88% | NA | SM | 2+ |

| Paulus et al. (2020)33 | 62 M | NA | NA | CMC | 2- |

| Shane-Simpson et al. (2016)53 | 17 F, 21 F | W 67%; AA 9%, A 9%; H 6% | NA | INT | 2- |

| So (2017)34 | 39 F, 69 M | NA | NA | INT | 2- |

| van der Aa et al. (2016)25 | 12 F, 31 M | NA | NA | SM | 2- |

| Watabe & Suzuki (2015)12 | 49 F, 62 M | NA | NA | CMC | 2- |

| Ward et al. (2018)26 | 29 M | NA | NA | INT | 2- |

| Wright (2017)29 | 64 M | NA | NA | SM | 2- |

| Wright & Wachs (2019)38 | 14 F, 114 M | W86%; AA3%; H1%; A10% | NA | INT | 2+ |

| van Schalkwyk et al. (2017)56 | 14 F, 114 M | W86%; AA3%; H1%; A10% | NA | INT | 2- |

Gender M = Male, F = Female; **Race/Ethnicity W = White, AA = African American, H = Hispanic, A = Asian, O = Other; *** = Stated Platform FB = Facebook, INT = Internet, MAG = Empowerment magazine, DISC = Online Discussion Groups, ONLINE GRP = Online Group, MMO RPG = massively multiplayer online role playing game, DP = Dating Profiles, TW = Twitter, FORUM = Online Forum, SL = Second Life, VC = Video Calling, SM = Social Media, CMC = Computer mediated communication

Authors' Contributions

E.M.H. and C.S. conceptualized, designed, and conducted the review, according to systematic review procedures, and drafted the initial article with findings. L.G.H. and J.W. collected and coded data and participated in data analysis. C.S. oversaw the research assistant, Timothy Gorichanaz, who participated in data collection. L.G.H. assisted in drafting and revising the article. K.C. provided expertise about information and communication technologies. J.W. conducted further literature reviews, configured tables, conducted analysis, and prepared references. E.M.H. drafted this article with input on revisions from C.S., L.G.H., J.W., and K.C. All coauthors have reviewed and approved of the article before submission. The article has been submitted solely to this journal and is not published, in press, or submitted elsewhere.

Disclaimer

The information, content, and/or conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. government.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This project was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under UJ2MC31073: Autism Transitions Research Project.

Supplementary Materials

References

- 1. Khoo D. How has the internet changed consumers over the past 10 years and how can marketers best adapt. Brandba se. 2014;25:2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Given LM, Winkler DC, Wilson R, Davidson C, Danby S, Thorpe K. Watching young children “play” with information technology: Everyday life information seeking in the home. Library Inform Sci Res. 2016;38(4):344–352. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burke M, Kraut R, Williams D.. Social Use of Computer-Mediated Communication by Adults on the Autism Spectrum. CSCW’10 Proceedings of the 2010 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work. 2010:425–434. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brownlow C, O'Dell L. Constructing an autistic identity: AS voices online. Mental Retardation. 2006;44(5):315-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ryan S, Räisänen U. “It's like you are just a spectator in this thing”: Experiencing social life the ‘aspie’way. Emot Space Soci. 2008;1(2):135–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kelly SE, Moher D, Clifford TJ. DEFINING RAPID REVIEWS: A MODIFIED DELPHI CONSENSUS APPROACH. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2016;32(4):265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Glaser BG. Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. London: Wiedenfeld and Nicholson; 1967/1978;81:86. .

- 8. Harbour R, Miller J. A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines. Bmj. 2001;323(7308):334-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zolyomi A, Begel A, Waldern JF, et al. Managing Stress: The Needs of Autistic Adults in Video Calling. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction. 2019;3(CSCW):1-29.34322658 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iglesias OB, Gómez Sánchez LE, Alcedo Rodríguez MÁ. Do young people with asperger syndrome or intellectual disability use social media and are they cyberbullied or cyberbullies in the same way as their peers. las personas jóvenes con síndrome de asperger o discapacidad intelectual utilizan las redes sociales y son ciberacosados o ciberacosadores como sus padres? Psicothema. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mazurek MO, Shattuck PT, Wagner M, Cooper BP. Prevalence and correlates of screen-based media use among youths with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(8):1757-1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Watabe T, Suzuki K. Internet communication of outpatients with A sperger's disorder or schizophrenia in J apan. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. 2015;7(1):27-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abel S, Machin T, Brownlow C. Support, socialise and advocate: An exploration of the stated purposes of Facebook autism groups. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2019;61:10–21. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cooper K, Smith LG, Russell AJ. Gender Identity in autism: Sex differences in social affiliation with gender groups. J Autism Dev Dis. 2018;48(12):3995–4006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Byers ES, Nichols S. Prevalence and Frequency of Online Sexual Activity by Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2019;34(3):163-172. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gavin J, Rees-Evans D, Brosnan M. Shy Geek, Likes Music, Technology, and Gaming: An Examination of Autistic Males' Online Dating Profiles. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2019;22(5):344-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levine P, Marder C, Wagner M.. Services and Supports for Secondary School Students with Disabilities: A Special Topic Report of Findings from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2). National Center for Special Education Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sala G, Hooley M, Attwood T, Mesibov GB, Stokes MA. Autism and intellectual disability: A systematic review of sexuality and relationship education. Sex Disabil. 2019;37(3):353–382. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hannah LA, Stagg SD. Experiences of sex education and sexual awareness in young adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(12):3678–3687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Curtiss SL, Ebata AT. Building capacity to deliver sex education to individuals with autism. Sex Disabil. 2016;34(1):27–47 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roth ME, Gillis JM. “Convenience with the click of a mouse”: A survey of adults with autism spectrum disorder on online dating. Sex Disabil. 2015;33(1):133–150. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Benford P, Standen P. The internet: a comfortable communication medium for people with Asperger syndrome (AS) and high functioning autism (HFA)? J Assist Technol. 2009;3(2):44–53. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gillespie-Lynch K, Brooks PJ, Someki F, et al. Changing college students' conceptions of autism: An online training to increase knowledge and decrease stigma. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(8):2553–2566.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Müller E, Schuler A, Yates GB. Social challenges and supports from the perspective of individuals with Asperger syndrome and other autism spectrum disabilities. Autism. 2008;12(2):173-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van der Aa C, Pollmann MMH, Plaat A, van der Gaag RJ. Computer-mediated communication in adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders and controls. Res Autism Spectrum Disord. 2016;23:15–27. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ward DM, Dill-Shackleford KE, Mazurek MO. Social media use and happiness in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2018;21(3):205-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Byrne J. Autism and Social Media: An Exploration of the Use of Computer Mediated Communications by Individuals on the Autism Spectrum. Glasgow, UK: University of Glasgow; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brownlow C, O'Dell L. Autism as a form of biological citizenship. In: Davidson J, Orsini M, eds. Worlds of Autism: Across the Spectrum of Neurological Difference. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 2013:97–114. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wright MF. Parental mediation, cyber victimization, adjustment difficulties, and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace. 2017;11(1). [Google Scholar]

- 30. Coskun M, Hajdini A, Alnak A, Karayagmurlu A. Internet Use Habits, Parental Control and Psychiatric Comorbidity in Young Subjects with Asperger Syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(1):171-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hswen Y, Gopaluni A, Brownstein JS, Hawkins JB. Using Twitter to detect psychological characteristics of self-identified persons with autism spectrum disorder: a feasibility study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2019;7(2):e12264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kawabe K, Horiuchi F, Miyama T, et al. Internet addiction and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2019;89:22-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Paulus FW, Sander CS, Nitze M, Kramatschek-Pfahler A-R, Voran A, von Gontard A. Gaming Disorder and Computer-Mediated Communication in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Zeitschrift für Kinder-und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. So R, Makino K, Fujiwara M, et al. The prevalence of internet addiction among a Japanese adolescent psychiatric clinic sample with autism spectrum disorder and/or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a cross-sectional study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(7):2217-2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mazurek MO. Social media use among adults with autism spectrum disorders. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(4):1709-1714. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gillespie-Lynch K, Kapp SK, Shane-Simpson C, Smith DS, Hutman T. Intersections Between the Autism Spectrum and the Internet: Perceived Benefits and Preferred Functions of Computer-Mediated Communication. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2014;52(6):456-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stendal K, Balandin S. Virtual worlds for people with autism spectrum disorder: a case study in Second Life. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(17):1591-1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wright MF, Wachs S. Does peer rejection moderate the associations among cyberbullying victimization, depression, and anxiety among adolescents with autism spectrum disorder? Children. 2019;6(3):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Davidson J. Autistic culture online: Virtual communication and cultural expression on the spectrum. Soc Cult Geogr Soc Cult Geogr. 2008;9(7):791–806. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Giles DC. “DSM-V is taking away our identity”: The reaction of the online community to the proposed changes in the diagnosis of Asperger's disorder. Health (London). 2014;18(2):179–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jones RSP, Meldal TO. Social Relationships and Asperger's Syndrome A Qualitative Analysis of First-Hand Accounts. J Intellect Disab. 2001;5(1):35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ringland KE, Wolf CT, Faucett H, Dombrowski L, Hayes GR. “Will I always be not social?”: Re-Conceptualizing Sociality in the Context of a Minecraft Community for Autism. CHI’16 Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 2016:1256–1269. April, 2016. San Jose, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pinchevski A, Peters JD. Autism and new media: Disability between technology and society. New Med Soc. 2016;18(11):2507–2523. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Parsloe SM. Discourses of disability, narratives of community: Reclaiming an autistic identity online. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2015;43(3):336-356. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kuo MH, Orsmond GI, Coster WJ, Cohn ES. Media use among adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2014;18(8):914-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bertilsdotter Rosqvist H, Brownlow C, O'Dell L. Mapping the social geographies of autism – online and off-line narratives of neuro-shared and separate spaces. Disability & Society. 2013;28(3):367-379. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gülerce A. Selfing as, with, and without othering: Dialogical (im) possibilities with dialogical self theory. Cult Psychol. 2014;20(2):244–255. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Allely CS, Kennedy S, Warren I. A legal analysis of Australian criminal cases involving defendants with autism spectrum disorder charged with online sexual offending. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2019;66:101456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kenny MC, Crocco C, Long H.. Parents' Plans to Communicate About Sexuality and Child Sexual Abuse with Their Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Sex Disabil. 2020:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shah S. “Disabled People Are sexual citizens too”: supporting sexual identity, Well-being, and safety for Disabled Young People.. Paper presented at: Frontiers in Education. 2017.

- 51. Sallafranque-St-Louis F, Normand CL. From solitude to solicitation: How people with intellectual disability or autism spectrum disorder use the internet. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace. 2017;11(1). [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kowalski RM, Fedina C. Cyber bullying in ADHD and Asperger Syndrome populations. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5(3):1201-1208. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shane-Simpson C, Brooks PJ, Obeid R, Denton E-g, Gillespie-Lynch K. Associations between compulsive internet use and the autism spectrum. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2016;23:152-165. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Engelhardt CR, Mazurek MO, Hilgard J. Pathological game use in adults with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gallup J, Little ME, Serianni B, Kocaoz O. The potential of virtual environments to support soft-skill acquisition for individuals with autism. The Qualitative Report. 2017;22(9):2509-2532. [Google Scholar]

- 56. van Schalkwyk GI, Marin CE, Ortiz M, et al. Social media use, friendship quality, and the moderating role of anxiety in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47:2805-2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Normand CL, Sallafranque-St-Louis F. Cybervictimization of young people with an intellectual or developmental disability: Risks specific to sexual solicitation. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2016;29:99-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.