Abstract

The emergence of critical autism studies has fueled efforts to interrogate how autistic people are studied and described in academic literature. While there is a call for research that promotes better well-being for autistic people, little attention has been paid to the concept of well-being itself. Just as the medical model limits critical understandings of autism in the academic literature, so too may psychological accounts of well-being limit, rather than expand, possibilities of living a good life for autistic people. The purpose of this critical review was to identify and critique how well-being in autistic adults is constructed in research. Based on a systematic search of peer-reviewed empirical research published from 2013 to 2020, we identified 63 articles that involved direct data collection with autistic adults and focused on well-being constructs such as quality of life, life satisfaction, and happiness. We examined the articles using the techniques of critical discourse analysis to discern assumptions underlying constructions of autistic well-being, with special attention to the axiological and teleological contributions of autistic perspectives in the research and writing processes. We identified several approaches through which the literature constructed autistic well-being: (1) well-being as an objective uncontested variable, (2) well-being as personal and not fixed, (3) well-being that warrants a specific measure for the autistic population, and (4) well-being as a situated account that privileges and centers autistic people's perspectives. We subject these accounts to critical analysis, pointing to how they limit and open life possibilities for autistic people. We recommend that researchers and practitioners critically reflect on how they engage autistic adults and use their input to create works that support well-being in ways that are meaningful and ethical to autistic adults, as well as do justice to changing broader narratives of autism in research and society.

Lay summary

Why was this study done?

More autistic people and researchers have advocated to study autism in critical and positive ways. While it is important to promote better well-being for autistic people, little is known about what well-being actually means to them.

What was the purpose of this study?

The purpose of our critical review was to identify how the concept of well-being in autistic people is understood and described in academic literature. We also critiqued how well-being research considers the input and perspectives of autistic adults.

What did we do?

We systematically searched for research articles published between 2013 and 2020. We identified 63 articles that involved direct data collection with autistic adults and focused on well-being and related concepts such as quality of life, life satisfaction, and happiness. We analyzed the articles by focusing on how they used language to describe well-being in autistic adults and how they valued the data collected from these adults.

What did we find?

We identified several ways that article authors described their understanding of autistic well-being: (1) well-being as an objective and uncontested object, (2) well-being is personal and can vary in nature, (3) well-being warrants a measure that considers opinions of autistic people, and (4) well-being as very specific to autistic people's subjective perspectives. We critically analyzed how these different understandings limit or open life possibilities for autistic people's well-being.

How will this work help autistic people?

We recommend that researchers critically reflect on how they engage autistic adults and use their input in research. Promoting well-being needs to be meaningful and ethical to autistic adults. Research also needs to advocate for social justice to challenge how the majority in society understands or misunderstands autistic people.

Keywords: well-being, autism, adults, critical autism studies, discourse, construct

Introduction

Several decades of autistic scholarship and activism have helped advance our understanding of autism, but only in recent years have autism scholars begun to explore and critique how research and academic work should study autism and include autistic people.1 Guided by an emerging approach in autism research, critical autism studies (CAS), critical autism scholars interrogate the power relationships that construct autism, challenge dominant negative narratives around it, and adopt methods and theories that enable greater access for autistic people.2 Critical autism scholars have illustrated how knowledge around autism is constructed in academia, society, and various cultural spaces, having a direct impact on how neurotypical people come to understand and interact with autistic people.3–6

While there is a long history of a biomedical, deficit-oriented understanding that depicts autism as a disorder with impairments that need to be remediated,7,8 self-advocates and different stakeholder groups working with autistic people increasingly call for research and practices that respond to and promote better lives for the autistic community.9 Although everyone would agree that a good, quality, and happy life is deserved by autistic and non-autistic people alike, what such a life can and should be is highly contested. In recent decades, well-being has become the direct focus of empirical investigations, instead of the subject of abstract philosophical debates, such that scholars now use different theories and conceptualizations to understand what constitutes and promotes well-being in real life.10 A sizable body of theoretical and empirical literature studies well-being using a variety of constructs with different definitions. For instance, a positive emotions perspective aims to assess one's affective states and experience (e.g., happiness), and a life satisfaction perspective is more focused on the subjective appraisal of one's overall life or particular life domains, while the construct of quality of life also incorporates assessment of personal functioning and environmental conditions, and some definitions of psychological well-being also consider one's purpose and meaning in life.11,12 Unfortunately, to date, the empirical research that studies these and other well-being constructs in autistic people generally lacks thorough conceptualizing or robust theorizing,13 which is problematic especially considering the constructs’ insensitivity to neurodiverse personhood among autistic people.14

Just as the medical model may limit positive, complex, and critical understandings of autism in the academic literature, so too many current psychological accounts, if used without scrutinizing and questioning, may erroneously narrow our understandings and strategies to promote a good life for autistic people.15 In other words, our contemporary knowledge around autism is not value-free, but instead may contain unspoken assumptions that are, in part, mediated by the changing cultural practices of research, which, if unexamined, may inadvertently impact the lives of autistic people in ways that are not intended or expected. For this reason, we follow the critical gesture of CAS in the study of autism, and adopt a critical psychology approach in our analysis of the construct of well-being. Similar to CAS, critical psychology draws from a long tradition in critical theory to identify and critique the role of psychological institutions and discourses in the (re)production of oppression and inequity. In response to the limitations of mainstream psychology in studying human subjectivity and relationships, critical psychology has emerged to challenge the values, assumptions, and positionalities underlying the research methods and interpretations, which uphold the status quo of psychological knowledge.16,17

Our goal is not to evaluate the conceptual robustness of well-being constructs, nor do we aim to identify the best way to study well-being in autistic people. We agree with many scholars that the study of well-being can be approached from many different philosophical traditions and theoretical standpoints,12,18 the choice of which also corresponds to how well-being is defined, measured, or otherwise represented in a study.19 Furthermore, we situate this study in the critical tradition by problematizing the current knowledge around autistic well-being because we are concerned that the construct is being researched in ways that may be inappropriate or detrimental. With the rise of evidence-based practice in human services, including psychology and education, the question of what works often overshadows other equally important questions such as how and for what research and practice should work.20 Therefore, our goal is to study the purpose (teleology) and value (axiology) of research that adopts particular conceptualizations of well-being, and how these usages come together to shape the construct(ion)s of autistic people's well-being.

We recognize the demand from the critical autism studies to center the perspectives of autistic people to promote ontological rigor and epistemological integrity in autism-related research.21,22 Therefore, we focused our current inquiry on analyzing how and to what extent input from autistic people guided well-being research. At the same time, we would like to clarify the social positions and intersectional identities from which we write as a team. Although none of us identifies as autistic, our research team is a combination of colleagues who are neurotypical and neurodiverse, White and non–White, men, women, and queer and non-queer people. Because of such diverse personal backgrounds, each of us brought a different lens to our use of critical paradigms. Nonetheless, we all share similar concerns over the dominance of positivistic approach in research, particularly in psychology and education, that may limit complexities of human differences. The first and second authors are psychologists who, despite having trained in mainstream psychology, came to adopt critical psychology approaches to engage the lived experiences of autistic individuals and racial minorities, respectively, in questioning the dominant psychological knowledge and advocating for more responsive approaches and policies for these intersecting groups. The third and fourth authors use poststructural and critical theories to unpack complexities and power relations in research methods and educational practices. Writing from such different positionalities enables us to analyze from various perspectives the assumptions and values laden in the common understanding of autism, which we argue do not always translate to good ethics of care for diverse autistic individuals and the disability community in general.

As researchers immersed in psychology and education, we worry that dominant research treats the concept of autistic well-being without critical examination, and threatens to do injustice and harm to autistic people's well-being. Therefore, we are using critical theory to interrogate the status quo of research about autistic well-being, recognizing that this responsibility ought not to fall solely on autistic researchers.23 Although we attempt to be allies to the autistic community, our research team may be justifiably critiqued for lacking embodied knowledge of autism. We therefore want to clarify that this study and its findings should not be seen as providing an authoritative account of autistic well-being. Nonetheless, we hope to engage autistic and non-autistic scholars alike to continue critical dialogues and perform better research, as “[b]oth autistic people and non-autistic people have a part to play in moving knowledge about autism forward.”23

Situated within the theoretical perspectives of CAS and critical psychology, the purposes of our critical review are to analyze (1) how well-being in autistic adults is constructed in empirical research, and (2) the role of autistic adults’ involvement in the constructions.

Methods

Data sources

This critical review included journal articles identified from a systematic literature search. No human research ethics approval was needed for this review study. The first author conducted a search in June 2020 on databases, including ERIC, PsychINFO,, CINAHL, Medline, ProQuest Social Science Database, and Web of Science. The search was conducted to identify articles containing the following keywords in the titles to obtain studies with an explicit and central focus on autistic well-being: (1) autis*, Asperger, pervasive developmental disorder, or ASD, and (2) well-being, wellbeing, life satisfaction, happiness, quality of life, wellness, or good life. We decided to search for peer-reviewed articles published from 2013 onward to analyze how research has evolved since the first formal publication of CAS.2 We only included empirical articles with systematic research design (including quantitative, qualitative, systematic review) that involved data collection directly with autistic adults because we were concerned with how their input was used to construct this field of study.

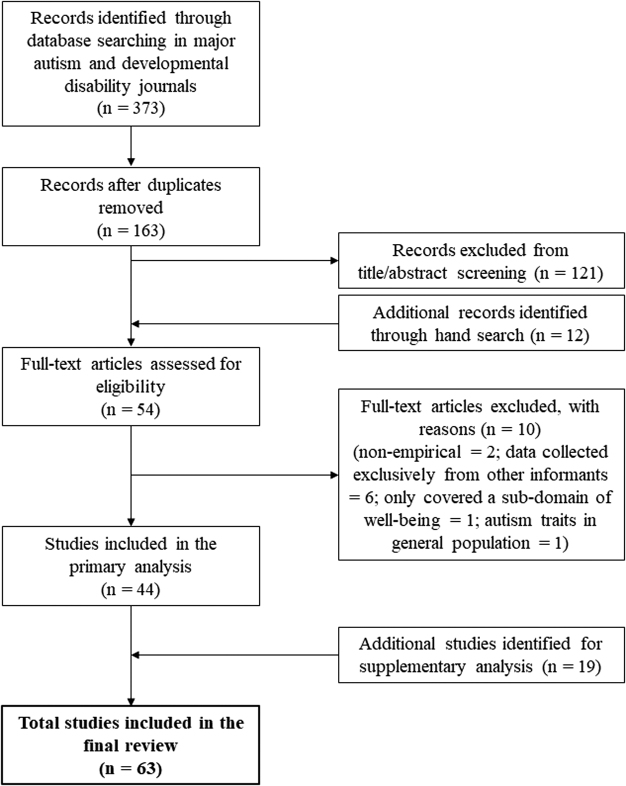

To center our analysis on the dominant field of autism research, we decided to conduct our first stage of search in journals with titles containing keywords “autism” and “developmental disabilit*,” which yielded 163 unduplicated results, 121 of which were screened out due to their focus on well-being in parents or minors of average ages below 18 years old. The first author identified 12 additional articles through hand search in autism and developmental disability journals. The first author assessed the full text of the 54 articles and further excluded 10 non-relevant articles (Fig. 1). In the first stage of analysis, we included 44 articles that were published in 7 different autism-specific journals (e.g., Autism, Autism in Adulthood, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities).24–67 To complement and check the quality of our primary analysis, we analyzed an additional 19 articles published outside of the major autism journals that met the same inclusion and exclusion criteria.68–86

FIG. 1.

PRISMA search strategies and results.

Analytical framework

We drew from Gee's techniques of critical discourse analysis (CDA)8787 to analyze the journal articles to reveal the language used to construct autism and well-being, as well as the ideologies and the social, cultural, and political contexts behind these constructions. Discourse involves “combining and integrating language, actions, interactions, ways of thinking, believing, valuing, and using various symbols, tools, and objects to enact a particular sort of socially recognizable identity.”87 Specifically, CDA reveals the relationships between (1) language used in a social context, (2) the ideologies, values, and assumptions underlying the language used, and (3) how the first two factors relate to broader social, cultural, and political contexts.88 Recognizing that power and inequalities are developed and maintained in the society by discursive practices, CDA investigates the connections between discourse and society with an aim to bring about social changes.89

Data extraction and analysis

In the first stage of analysis, all the authors extracted the 44 articles using a pro- forma6 that summarized features of the publications, including the study purposes, methodologies, sample characteristics, findings, and limitations. We closely read the text of the articles to identify statements that signify the presence and absence of certain characteristics that establish the boundaries of the construct of well-being (e.g., What is well-being versus what is not?). We also paid attention to how well-being was constructed in relation to different conceptualizations of autism (e.g., What is considered or described as autism?). To identify the roles of autistic adults’ involvement in the studies and how their perspectives were being treated, we focused our analysis on the data collected directly from autistic individuals instead of any proxies’ reports to delineate the research axiology and teleology (e.g., What are the purposes and values of the autistic participants’ data? What perspective is being centered versus marginalized?). At least two authors read and extracted 14 (32%) of the articles to ensure consistency in data extraction and interpretation. All authors met weekly over a 3-month period to compare our extraction and reconcile differences. Drawing from Gee's building tasks of language and discourse analysis tools,90 we analyzed what the articles made as important and how they achieved that discursively (“significance building tool”). We employed the “identities building tool” to note what and how the articles enact and position social identities. We also used the “politics building tool” to identify what and how the articles count “things like having ourselves, our behaviors, or our possessions [being] treated as ‘normal,’ ‘appropriate,’ ‘correct,’ ‘natural,’ ‘worthy,’ or ‘good.’”90 These tools assisted us with the open coding process through which we critically analyzed and questioned the textual data extracted from the articles. We compared all the articles and grouped them based on the repeated codes identified through the pro- forma. Each of the categories contained coherent codes and themes that reveal broader patterns and phenomena characterizing different discourses around well-being in autism in the literature.

For the second stage of complementary analysis, the first author read through and extracted the full text of the additional 19 articles. Since no extra themes were identified, all authors agreed that our analysis had achieved data saturation. The additional articles were then sorted into the existing categories and integrated with the primary analysis. The final review discussed below represented represents our analysis of a total of 63 articles. No human research ethics approval was needed for this review study.

Results

Our analysis yielded two broad categories of articles that presented two major ways of understanding of well-being in autistic adults. Articles in Category 1 presented research that treated autistic adults and their well-being as objects produced by science. Assessing autistic adults’ well-being predominantly by measuring it with methods similar to the general population, these articles either treated well-being as an objective, uncontested construct (Subcategory 1A), or as a more personal concept that can be better assessed with an improved measure (Subcategory 1B). In Category 2, autistic adults’ active involvement was central to the conceptualizations of well-being in these articles. While some focused on adapting autism-specific measures based on the opinions of autistic adults (Subcategory 2A), others presented a variety of ways in which autistic adults expressed their subjective views of well-being (Subcategory 2B). Below we describe the themes in each category and subcategory, and illustrate the findings by using direct quotes from the original texts.

Category 1: autistic adults’ well-being manifested as object of science

Articles in Category 1 centered on assessing or manipulating the well-being construct per se.24–54,68–82 Their overarching goals were to discover and establish theoretical relationships between well-being in autistic adults with other “predictors” and “associated/related factors.” The authors of these articles constructed well-being as a stable ontological construct whose properties hold relatively constant across time, space, and individuals, and which therefore can be measured with a reliable psychometric tool. As such, input from autistic adults seemed unnecessary, as their involvement was almost exclusively limited to giving data about their well-being by filling out questionnaires. Using various measures of well-being, these studies sought to describe functioning and compare across subgroups of autistic adults,28,34,36 evaluate changes following interventions,38,49,70,77 use well-being as a criterion index to validate other tools,35,37 and use self-report to complement caregivers’ report.27,51

Deficit-focused and medically oriented descriptions of autism were prevalent. These articles commonly introduced autism by citing the definition of “autism spectrum disorder” using the diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,91 followed by numerous examples of “impairments,” “symptoms,” “comorbid disorders,” “problems,” and “poor outcomes.”31,34,35,37,49,53,74,81 Autism was also compared against “healthy” people,29,33,41,73 described as a “burden” for the individual and society,40 and easily “more vulnerable.”37

Subcategory 1A: well-being as an objective, uncontested construct that is readily measurable

This subcategory of articles framed well-being as a straightforwardstraight-forward concept whose meaning, at both conceptual and measurement levels, was settled and in little need of further debate.24–42,68–75 While there are different ways to define and conceptualize well-being, the authors did not deliberate on the conceptual underpinnings or provide theoretical justifications for choosing one definition or measure over another in their studies. Many of these articles studied the same construct quality of life QOL, but with different definitions and measurement domains. For example, while some30,73 used the World Health Organization's definition and their instruments, WHOQOL (World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment) and the abbreviated version, WHOQOL-BREF,92 that were claimed to be applicable cross-culturally, others31,70 adopted definitions that were argued to be tailored to individuals with developmental or intellectual disabilities, although not specifically for autism. Others differentiated between objective QOL (e.g., academic success, living conditions) and subjective QOL (e.g., manageability, meaningfulness, life satisfaction).32,33 Inconsistent or mismatched definitions were also noted across some of the articles. For example, “well-being” was measured by life satisfaction, self-esteem, and absence of psychopathology,34 while “subjective well-being” was operationalized as autonomy, relatedness, and competence,35 and “psychological well-being” as positive emotions, functioning, and social relationships.30,36

Authors in this subcategory presented their operationalizations of well-being as a matter-of-fact, unaccompanied by any discussions that might complicate its nature. In other words, well-being was presented as if it were an uncontested construct that can be readily measured, controlled, and manipulated. This was reflected in a number of studies that borrowed the scales to measure well-being to establish the value of the central constructs or interventions under study, without discussing how they conceptualized well-being and its relationships with other constructs.35,36,38 However, the lack of precise correspondence between a stated well-being construct and its choice of measurement may have resulted in confusion in conceptual understanding of well-being. For example, one study claimed to find a significant association between “mental well-being” and “psychological QOL” that were described as two distinctively different constructs, but there were substantial overlaps of items in the two measures.30 In fact, many studies only reported their reasons for choosing a particular measure as “easy to compare,” “most frequently used tool,” and “sound psychometric properties,” 26,27,31,47 without discussing the conceptual basis of the constructs or scales, thus calling into question the clarity of well-being constructs that were represented by the chosen measures.

Some authors assumed certain objective standards that can and should be applied universally to well-being in all autistic people. For example, objective QOL was defined as “de facto psychosocial life situation, that is, living situation, occupation, relationships, and so on,” which the authors equated a high QOL with having a full-time job, living independently, and having social friendships.33 It was argued, “Adulthood is a life stage when it is normative for individuals to be autonomous and independent from their parents in life choices and preferences. Yet many adults with ASD continue to depend on their family for support,” implying that autistic people are good insofar they achieve what is defined as normal by the majority.27 Using a similar logic, it was reasoned that “The large difference in QoL between people with and without autism warrants that much work needs to be done to help people with autism reach a higher level of QoL,”26 again assuming certain normative wellness standards and the universal applicability of the chosen measure. Autism symptoms were described to create “mental health burden,” “physical burden,” comorbid mental health conditions, and lower motor functioning, which were ultimately linked to “financial burden” in society: “The total (direct and indirect) lifetime per capita societal cost of autism is $3.2 million, with lost productivity and adult care being the main cost drivers.”40

Subcategory 1B: well-being as an a non-fixed construct that needs better measurements

Under the broad Category 1, articles in Subcategory 1B shared similar goals to gather data from autistic adults and study their well-being as a scientific object.43–54,76–82 Nonetheless, studies in this Subcategory directly critiqued the various ways in which well-being has been conceptualized, thus framing the non-essentialist nature of the construct, subjected to different interpretations depending on the chosen definitions, perspectives, and time contexts.43 Some authors argued that although well-being in autism was generally found to be lower, the findings can vary according to the specific measures and methodologies used.44 Some articles presented a more “complex,” “nonlinear”45 definition of well-being that emphasizes “person-environment fit.”46

Articles in this Category advocated the use of autistic self-report instead of reports by proxy or other informants such as caregivers or clinicians,47,48,78,82 which was argued as a “novel” approach that “represents an essential shift toward valuing the views of adults with ASD as experts on their own lives.”49 Such shift of focus to their perspectives further highlights the goals, values, and things that they expressed as important in their lives.50–52 Considering autistic people's needs and wants led to the questioning of applying normative standards to their well-being:44,46 “It is important to move beyond these normative outcomes [e.g., living independently, finding employment, developing friendships] to understand how other aspects of quality of life may play a role in the lives of autistic adults, including wellbeing and satisfaction with life.”43

Notwithstanding the efforts to introduce early in the writing the needs for an autism-specific account of well-being, articles in this Subcategory proceeded to measure their well-being using scales that were developed for the general population.49,50 Despite describing the chosen measures as “valid,” some authors arbitrarily inserted additional items without explanations,48 or omitted certain items (e.g., sexual life) as if they were not important to autistic well-being.50 Most authors only questioned the relevance of the chosen measures in autistic people at the very end of the articles, as if such critiques were a posteriori thoughts when in fact these should be a priori considerations. They questioned whether autistic individuals have the ability to complete questionnaires,44 interpret the items differently,44,53 and value things not covered in the measures.45,52,77,79 They further argued for the need to develop alternative methods to more fully elicit autistic people's first-person perspectives.44,51,76,81

While constructing well-being as a variable construct, some articles in Subcategory 1B used descriptions that avoided deficit-laden language to open up the construction of autism as more complex than a fixed disorder. Even from a medical point of view, the border between those who received and maintained an autism diagnosis and those without such label was not completely clear.51 Autism can also be understood as an “identity” that one does not want to conceal54 and with “special interests” that can “have a positive impact on QOL and wellbeing for autistic individuals.”43 Their positive and exceptional aspects were also highlighted: “striking heterogeneity of this population … with variable levels of positive outcome,”46 and “significant untapped potential that has been underappreciated.”49

Category 2: autistic adults express what well-being is to them

Contrary to Category 1 that treated autistic adults as passive producers of their relatively stable and objective well-being, Category 2 presented research with more active involvement of autistic adults’ perspectives and their participation.55–67,83–86 These articles centered their arguments on critiquing the dominant narratives in academic literature that have led to inaccurate portrayals and understanding of autistic well-being. For example, some authors55–58,62,83 clearly argued in the introduction that the trend of lower well-being in autistic population described in the literature did not actually reflect they have poorer lives, but may be due to the fact that autistic people interpret the measures differently and value things not captured in traditional scales or typical indicators that were developed for a neurotypical population.58,83,85 While acknowledging the differences in autistic people and the difficulties they face in life, these researchers challenged the primarily negative narratives around autism that were at least partially mediated by the failure of past research to engage autistic people.62,64,67 It is not possible to make sense of the big picture findings without understanding what experiences or activities are valued more or less by autistic people.55,56,60,83 Responding to this problem, autistic people were invited to assert themselves against the dominant understanding of their well-being. This was achieved through two different approaches (2A and 2B) of engaging autistic people in research.

Subcategory 2A: well-being measures considering autistic adults’ opinions.55–60

This subset of articles aimed to better understand well-being in autistic adults by “measur[ing] it in a meaningful way”55 using a valid and reliable measure developed based on the opinions collected through “active involvement of autistic people to define QOL.”55–60 These studies involved autistic adults as “consultants” to review an existing QOL measure, WHOQOL-BREF,92 and suggest modifications or new items.57,58 Nonetheless, some authors argued that the validity of the resultant autism-specific scale was still “questionable” due to their top-down research approach, such as discarding suggested items with insufficient votes57 and analyzing participants’ themes deductively.58 The values of autistic adults’ input were placed on quantitative measures over qualitative descriptions: Even when first-person narratives with themes that were considered unique to autistic people were collected,58 these quotes were only to “augment” quantitative data and “to elaborate on relationships between variables and generate new hypotheses.”59 For those who had difficulties filling out the measures, caregivers were invited to either complete on their behalf56 or provide clarification or assistance.59 The psychometric properties of the measures were of central importance,56,57 as the stated purposes of such tools were to “reach consensus regarding what constitutes ‘good’ QOL for autistic individuals,”56 make generalizable claims that “exact cross-cultural standards” and are “internationally valid,”58 and be able to compare among autistic people as well as against other disabled or neurotypical populations.57

Subcategory 2B: centering autistic adults’ subjective perspectives on the nature of well-being.61–67,83–86

This subcategory of articles assumed a position that centered on autistic adults’ personal, subjective, unique experiences through inquiring about what things matter to their well-being and why.61–67,83–86 Their central purposes were to “privilege the autistic participants’ worldviews and to facilitate their meaningful contributions,”62 based on the vision that “a personalised objective for wellbeing should be developed with and for each individual.”61 Even though people, autistic or neurotypical, may share similar desires or needs, individuals’ goals, values, and prioritization of these well-being indicators may vary.61,64,65,85 Focusing on the nuances and insights of one's ideas and conceptualizations about well-being, including what might have been misrepresented or missed previously, was prioritized over, although not dismissive of, objective measures of QOL and their usages in group-based comparison.65,66,83,86

The shift of focus from traditional measurement approaches to autistic individuals’ subjective perspectives opens up the conceptualizations of well-being as situated and nonuniversal. While no one factor contributed to well-being in isolation, the focus of these studies showed how various factors played out in real-world environments, which may include one's personal judgments and meanings manifesting in specific contexts, such as in college, a supported living program, a psychiatric unit, and a music therapy singing group.65–67,84 Autistic well-being can also be captured like a process or an experience: A “journey” to demonstrate “learning” to achieve personally meaningful goals,67 a “pursuit of wellbeing” and “search for personally meaningful experience,”62 which needs “time to process” through “day-to-day discussions about well-being with the young person.”61 This positionality was to contrast the traditional approach that aimed at demonstrating quantifiable improvements in discrete skills or behaviors, subjecting autistic individuals to a set of predetermined categorical standards of success, and making normative assumptions based on the neurotypical worldview.62,67,83,85 It is important to note that, “The purpose, meaning and importance of happiness vary for each person, but young people with autism need support to ensure they do not carry the expectation of happiness as a burden.”61

To prioritize what things autistic adults considered as meaningful and valuable, these studies used a wide variety of methods to inquire and understand why such experiences contribute to their well-being. There is no “one- size- fits- all,”61 as no single method can be considered most effective or accurate to get at their first-person perspectives. Many authors directly asked autistic participants to respond in qualitative interview.61–63,83,84 They also flexibly adopted additional data collection strategies to elicit multiple perspectives from autistic people, such as taking photos in daily life,62,67 using their self-defined goals in measures,67 analyzing existing magazine entries written by self-advocates,85 allowing multiple modalities to express their perspectives in interviews,65,84 and inquiring their preferences for data collection methods.61 Furthermore, some authors acknowledged the relationship aspects in research, emphasizing in some cases, existing relationships with the autistic participants could facilitate how they expressed their ideas of well-being.61–63,86 These studies valued respectful and collaborative relationships with autistic participants, demonstrated by assessing their beliefs and preferences which “gives an unbiased understanding of their agency and volition.”64,67 Some autistic participants or researchers also assumed central roles in deciding research questions, collecting and analyzing data, and co-authoring articles.62,85

Discussion

In this critical review, we analyzed how empirical articles in peer-reviewed journals constructed the concept of well-being in autistic adults. We identified two categories of articles that described two major approaches of how they treated autistic people's input and how that painted a different understanding of well-being. The first category used autistic people as data-giver to assess by measuring their well-being to discover the relationship between variables and constructs. While across articles there were various ways to define such a complex construct and to specify the dimensions or contributing factors under study, they either did not explain their chosen well-being conceptualization or stated a mere definition without much deliberation on the theoretical underpinnings. The missing purposes or rationales rendered the underlying assumptions of such method unexamined. These pitfalls have been critiqued as “a rush to measurement”93 that evades the complex theorizing and philosophizing around the very nature of well-being. When such knowledge about autism is inscribed with minimal meaningful input and representations by autistic people, their personhood and agency are being erased, giving rise to readily consumable and commodifiable products that can be easily circulated in research and science.5

Another critique of this dominant measurement-focused approach to understanding well-being is the reinforcement of a normative ideal. When researchers use a measure with preset items that are supposed to represent well-being, and compare “how much” well-being a person or a group has over another, the implicit assumption is that the domains covered in the measure are equally valued by everyone.94 For measures that were developed for the general population, interindividual variability between autistic and neurotypical people is ignored (e.g., whether autistic people value the same things as nonautistic people). Even for those measures that involved consultation and validation with autistic people, as evidenced in Subcategory 2A, individual variations among the autistic population were not centered (e.g., whether each autistic person weighs certain items similarly or differently), thus assuming an assimilationist mindset. Even though the various measures can be argued to contain overlapping dimensions of baseline wellness,19 the commonalities among different well-being measures suggest a normative understanding of well-being, which may be at odds with the worldviews and lived experiences of autistic people.14 Researchers operating from this vantage point cannot escape the teleological effects of normalization, which legitimize their professionals’ authority to manipulate interventions and control treatments to disabled people.95 In such case, well-being still fails to divert itself from the biomedical desire to turn the “less-than-optimal” autistic individuals into close approximations of the normative archetype with ideals determined by the dominant neurotypical world. We argue that such big data approaches that use autistic people as passive data suppliers will continue to pathologize and marginalize diverse autistic personhood.96

The second category of articles distinguishes itself from traditional measurement approaches by centering on autistic subjective experiences and personal perspectives. This discursive move opens up new pathways to understand and represent well-being. Positioning well-being as unfixed, situated, or nonuniversal means it is not just something that can be measured, but instead something that must be understood through the combination of quantitative and qualitative methods. While qualitative methodology such as interviews is commonly considered an avenue to highlight participants’ voices, we, however, problematize such a claim as we observed that reliance on the use of interview methods privileged speaking as a means through which one's voice is heard. When researchers only attend to voice in speech, which is prized as the “normative conceptions of performance, participation and independence,”97 they overlook that which is not or cannot be expressed in utterances and exclude the perspectives of nonspeaking autistic people, thus essentially reinforcing another form of exclusionary normativity. Similarly, measurement studies commonly included only those who are able to complete written surveys either independently or with caregivers’ assistance. Some studies98 excluded from the current review because of no direct data collection from autistic adults were focused on autistic individuals who have diverse communication needs, whose perspectives of well-being were supposedly appropriated by proxies such as caregivers and clinicians.

In response to the critiques identified above, scholars in the field of autism advocated several ways research can be conducted to advance well-being while maintaining criticality and accessibility to the autistic community. As pointed out by critical scholars, well-being is not only by its conceptual nature experiential and dynamic, its experiences are intrinsically grounded in real life and actual community, where the resources and opportunities available for wellness are a function of social justice and fairness allowed for by the social structures.11 The highest level of personal thriving is promoted by optimal conditions in the community, where everyone has equitable access to resources to meet their diverse individual needs as well as to live an engaged life.99 Applying such a critical and community-oriented approach to autism research provides insight into how researchers should conduct research to produce knowledges knowledge that promote promotes justice as an inherent condition of wellness. For instance, although participatory methods can increase the engagement of autistic people to improve their lives,23,62,97,100 researchers need to critically analyze and scrutinize the notion of “participation.” Instead of referring merely to a researcher's inclusion of autistic participants’ “voices,” the question of what counts as participation should recognize the limitations of researchers as an “unreliable narrator” of autistic subjectivities.101 Breaking down the power hierarchy between the researchers and the researched is necessary to meaningfully facilitate agency of autistic people by creating space and opportunities to express their own ideas. For example, bioethicists recommended using well-being measures as a reciprocal process of inquiry between the inquirer and the person giving their well-being information, the knowledge gained from which is contingent upon their mutual constructions of critical reflections and sensitive interpretations.94 Autistic scholars have also suggested diversifying research methods and data sources as well as attending to disjuncture and inconsistency in data interpretation to facilitate meaningful expression of diverse autistic personhood.102

There are several limitations in our review. Several of the excluded articles did not meet the traditional criteria of empirical research, including commentary, report, and perspective article, but they presented a broader vision of well-being and highlighted the need to involve autistic individuals. For example, a workshop conducted with autistic people and various stakeholder groups stressed the need for research to center on autistic people's priorities and perspectives to design novel ways to better understand and enhance their personal well-being.103 Some articles also did not set out to focus on the concept of well-being, but the findings ended up having important contribution to this field of knowledge. In a roundtable discussion about strengths-based approaches, expert autism researchers pointed out the close connection between these approaches and participatory research methods, which both inherently lead to improvement in autistic people's lives.104

These observations pointed out important implications for future autism research. We observed that these non-empirical articles are often more progressive in expanding our understanding of well-being by piloting more flexible research strategies and creative writing styles that open up possibilities for autistic people instead of limit, foreclose, or marginalize certain forms of autistic engagement and expressions. If researchers were to apply these methods to future research to produce empirical knowledge and evidence that can be regarded as legitimate, what kind of research should be conducted? As autism experts and advocates reminded us, “[N]onspeaking folks with autism read poetry, write their own poetry, and produce chapbooks. Now we might not think of this as research per se [original emphasis].”104 Also, there is an extant body of non-academic literature or creative writings, much of which is produced by autistic authors, that offers important insights about diverse ways of being and autistic personhood.105,106 Only by diversifying our methods of inquiry and flexibly using different tools to answer different kinds of research questions can researchers broaden our knowledge base. Researchers should adopt paradigms and methodologies that are considered more responsive and inclusive of autistic participation, such as ethnography, participatory action research, narrative inquiry, and art-based research.107 More importantly, the knowledges knowledge created by the autistic lived experiences and of their worldviews will help expand the status quo of autism research to better understand how to promote well-being among the autistic community.

Authorship Confirmation Statement

G.Y.H.L. conceptualized the study and led the research and writing processes. All authors (G.Y.H.L., S.S., M.M.V., and J.R.W.) were involved in data extraction, analysis, and discussion. All authors contributed to the final article and approved of it before submission. This article has been submitted only to this journal and is not published elsewhere.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

The authors did not receive any funding for this study.

References

- 1. O'Dell L, Bertilsdotter Rosqvist H, Ortega F, Brownlow C, Orsini M. Critical autism studies: Exploring epistemic dialogues and intersections, challenging dominant understandings of autism. Disabil Soc. 2016;31(2):166–179. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Davidson J, Orsini M. Critical autism studies: Notes on an emerging field. In: Davidson J, Orsini M, eds. Worlds of Autism: Across the Spectrum of Neurological Difference. Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press; 2013;1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bagatell N. Orchestrating voices: Autism, identity and the power of discourse. Disabil Soc. 2007;22(4):413–426. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nadesan MH. Constructing Autism: Unravelling the ‘Truth’ and Understanding the Social. New York: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mallett R, Runswick-Cole K. Commodifying autism: The cultural contexts of ‘disability’ in the academy. In: Goodley D, Hughes B, Davis L, eds. Disability and Social Theory. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmilan; 2012;33–51. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wolgemuth JR, Agosto V, Lam GYH, Riley MW, Jones R, Hicks T. Storying transition-to-work for/and youth on the autism spectrum in the united states: A critical construct synthesis of academic literature. Disabil Soc. 2016;31(6):777–797. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brantlinger E. Using ideology: Cases of nonrecognition of the politics of research and practice in special education. Rev Educ Res. 1997;67(4):425–459. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oliver M. Understanding Disability: From Theory to Practice. Basingstoke: Macmillan; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Robertson SM. Neurodiversity, quality of life, and autistic adults: Shifting research and professional focuses onto real-life challenges. Disabil Stud Q. 2009;30(1). DOI: 10.18061/dsq.v30i1.1069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alexandrova A. Well-being as an object of science. Phil Sci. 2012;79(5):678–689. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arcidiacono C, Di Martino S. A critical analysis of happiness and well-being. Where we stand now, where we need to go. Comm Psychol Glob Perspect. 2016;2(1):6–35. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wren-Lewis S. Towards a widely acceptable framework for the study of personal well-being. In: Søraker JH, van der Rijt JW, de Boer J, Wong PH, eds. Well-Being in Contemporary Society. New York: Springer; 2015;17–38. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robeyns I. Conceptualising well-being for autistic persons. J Med Ethics. 2016;42(6). DOI: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rodogno R, Krause-Jensen K, Ashcroft RE. ‘Autism and the good life’: A new approach to the study of well-being. J Med Ethics. 2016;42(6):401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bölte S, Richman KA. Hard talk: Does autism need philosophy? Autism. 2019;23(1):3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Parker I, ed. Handbook of Critical Psychology. New York: Routledge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fox D, Prilleltensky I, Austin S, eds. Critical Psychology: An Introduction. 2nd ed. London: SAGE; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chung MC, Killingworth A, Nolan P. A critique of the concept of quality of life. Int J Health Care Qual Assurance. 1997;10(2):80–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Holmes S. Assessing the quality of life—Reality or impossible dream?: A discussion paper. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42(4):493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Biesta GJ. Why ‘what works’ still won't work: From evidence-based education to value-based education. Stud Philos Educ. 2010;29(5):491–503. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Woods R, Milton D, Arnold L, Graby S. Redefining critical autism studies: A more inclusive interpretation. Disabil Soc. 2018;33(6):974–979. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fletcher-Watson S, Adams J, Brook K, et al. Making the future together: Shaping autism research through meaningful participation. Autism. 2019;23(4):943–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guest E. Autism from different points of view: Two sides of the same coin. Disabil Soc. 2020;35(1):156–162. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Smith DaWalt L, Greenberg JS, Mailick MR. Participation in recreational activities buffers the impact of perceived stress on quality of life in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2017;10(5):973–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Mazefsky CA, Eack SM. The combined impact of social support and perceived stress on quality of life in adults with autism spectrum disorder and without intellectual disability. Autism. 2018;22(6):703–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van Heijst BF, Geurts HM. Quality of life in autism across the lifespan: A meta-analysis. Autism. 2015;19(2):158–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hong J, Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Smith L, Greenberg J, Mailick M. Factors associated with subjective quality of life of adults with autism spectrum disorder: Self-report versus maternal reports. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(4):1368–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smith IC, Ollendick TH, White SW. Anxiety moderates the influence of ASD severity on quality of life in adults with ASD. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2019;62:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chiang H, Wineman I. Factors associated with quality of life in individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A review of literature. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2014;8(8):974–986. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lawson LP, Richdale AL, Haschek A, et al. Cross-sectional and longitudinal predictors of quality of life in autistic individuals from adolescence to adulthood: The role of mental health and sleep quality. Autism. 2020;24(4):954–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. García-Villamisar D, Dattilo J, Matson JL. Quality of life as a mediator between behavioral challenges and autistic traits for adults with intellectual disabilities. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2013;7(5):624–629. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Deserno MK, Borsboom D, Begeer S, Agelink Van Rentergem, Joost A., Mataw K, Geurts HM.. Sleep determines quality of life in autistic adults: A longitudinal study. Autism Res. 2019;12(5):794–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Helles A, Gillberg IC, Gillberg C, Billstedt E. Asperger syndrome in males over two decades: Quality of life in relation to diagnostic stability and psychiatric comorbidity. Autism. 2017;21(4):458–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mazurek MO. Loneliness, friendship, and well-being in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2014;18(3):223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kaneko S, Kato TA, Makinodan M, et al. The self-construal scale: A potential tool for predicting subjective well-being of individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2020;13(6):947–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cai RY, Richdale AL, Dissanayake C, Uljarević M. How does emotion regulation strategy use and psychological wellbeing predict mood in adults with and without autism spectrum disorder? A naturalistic assessment. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;50(5). DOI: 10.1007/s10803-019-03934-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Griffiths S, Allison C, Kenny R, Holt R, Smith P, Baron-Cohen S. The vulnerability experiences quotient (VEQ): A study of vulnerability, mental health and life satisfaction in autistic adults. Autism Res. 2019;12(10):1516–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Connor A, Sung C, Strain A, Zeng S, Fabrizi S. Building skills, confidence, and wellness: Psychosocial effects of soft skills training for young adults with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(6):2064–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Knüppel A, Telléus GK, Jakobsen H, Lauritsen MB. Quality of life in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder: Results from a nationwide Danish survey using self-reports and parental proxy-reports. Res Dev Disabil. 2018;83:247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Khanna R, Jariwala-Parikh K, West-Strum D, Mahabaleshwarkar R. Health-related quality of life and its determinants among adults with autism. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2014;8(3):157–167. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kamio Y, Inada N, Koyama T. A nationwide survey on quality of life and associated factors of adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2013;17(1):15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Casagrande K, Frost KM, Bailey KM, Ingersoll BR. Positive predictors of life satisfaction for autistic college students and their neurotypical peers. Autism Adulthood. 2020;2(2):163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grove R, Hoekstra RA, Wierda M, Begeer S. Special interests and subjective wellbeing in autistic adults. Autism Res. 2018;11(5):766–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moss P, Mandy W, Howlin P. Child and adult factors related to quality of life in adults with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(6):1830–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hedley D, Uljarević M, Bury SM, Dissanayake C. Predictors of mental health and well-being in employed adults with autism spectrum disorder at 12-month follow-up. Autism Res. 2019;12(3):482–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Deserno MK, Borsboom D, Begeer S, Geurts HM. Multicausal systems ask for multicausal approaches: A network perspective on subjective well-being in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2017;21(8):960–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mason D, Mcconachie H, Garland D, Petrou A, Rodgers J, Parr JR. Predictors of quality of life for autistic adults. Autism Res. 2018;11(8):1138–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dijkhuis RR, Ziermans TB, Van Rijn S, Staal WG, Swaab H. Self-regulation and quality of life in high-functioning young adults with autism. Autism. 2017;21(7):896–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nadig A, Flanagan T, White K, Bhatnagar S. Results of a RCT on a transition support program for adults with ASD: Effects on self-determination and quality of life. Autism Res. 2018;11(12):1712–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kojima M. Subjective well-being of people with ASD in Japan. Adv Autism. 2020;6(2):129–139. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lord C, McCauley JB, Pepa LA, Huerta M, Pickles A. Work, living, and the pursuit of happiness: Vocational and psychosocial outcomes for young adults with autism. Autism. 2020;24(7):1691–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. White K, Flanagan T, Nadig A. Examining the relationship between self-determination and quality of life in young adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2018;30(6):735–754. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Park SH, Song YJC, Demetriou EA, et al. Disability, functioning, and quality of life among treatment-seeking young autistic adults and its relation to depression, anxiety, and stress. Autism. 2019;23(7):1675–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kim SY, Bottema-Beutel K. A meta regression analysis of quality of life correlates in adults with ASD. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2019;63:23–33. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Graham Holmes L, Zampella CJ, Clements C, et al. A lifespan approach to patient-reported outcomes and quality of life for people on the autism spectrum. Autism Res. 2020;13(6):970–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ayres M, Parr JR, Rodgers J, Mason D, Avery L, Flynn D. A systematic review of quality of life of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism. 2018;22(7):774–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. McConachie H, Mason D, Parr J, Garland D, Wilson C, Rodgers J. Enhancing the validity of a quality of life measure for autistic people. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(5):1596–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. McConachie H, Wilson C, Mason D, et al. What is important in measuring quality of life? Reflections by autistic adults in four countries. Autism Adulthood. 2020;2(1):4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mason D, Mackintosh J, Mcconachie H, Rodgers J, Finch T, Parr JR. Quality of life for older autistic people: The impact of mental health difficulties. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2019;63:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tobin MC, Drager KD, Richardson LF. A systematic review of social participation for adults with autism spectrum disorders: Support, social functioning, and quality of life. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2014;8(3):214–229. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Murray C. Consulting young people with autism within a specialist further education college on their personal happiness. Good Autism Pract. 2017;18(2):32–44. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lam GYH, Holden E, Fitzpatrick M, Raffaele Mendez L, Berkman K. “Different but connected”: Participatory action research using photovoice to explore well-being in autistic young adults. Autism. 2020;24(5):1246–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pfeiffer B, Piller A, Giazzoni-Fialko T, Chainani A. Meaningful outcomes for enhancing quality of life for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2017;42(1):90–100. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kim SY. The experiences of adults with autism spectrum disorder: Self-determination and quality of life. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2019;60:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bailey KM, Frost KM, Casagrande K, Ingersoll B. The relationship between social experience and subjective well-being in autistic college students: A mixed methods study. Autism. 2020;24(5):1081–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Murphy D, Mullens H. Examining the experiences and quality of life of patients with an autism spectrum disorder detained in high secure psychiatric care. Adv Autism. 2017;3(1):3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bernhardt JB, Lam GYH, Thomas T, et al. Meaning in measurement: Evaluating young autistic adults’ active engagement and expressed interest in quality-of-life goals. Autism in Adulthood. 2020;2(2). DOI: 10.1089/aut.2019.0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Asztély K, Kopp S, Gillberg C, Waern M, Bergman S. Chronic pain and health-related quality of life in women with autism and/or ADHD: A prospective longitudinal study. J Pain Res. 2019;12:2925–2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hamm J, Yun J. Influence of physical activity on the health-related quality of life of young adults with and without autism spectrum disorder. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(7):763–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Garcia-Villamisar D, Dattilo J, Muela C. Effects of B-Active2 on balance, gait, stress, and well-being of adults with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability: A controlled trial. Adapt Phys Activ Q. 2017;34(2):125–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kronenberg LM, Goossens PJJ, van Etten DM, van Achterberg T, van den Brink W. Need for care and life satisfaction in adult substance use disorder patients with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2015;51(1):4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lin L, Huang P. Quality of life and its related factors for adults with autism spectrum disorder. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;41(8):896–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lin L. Quality of life of Taiwanese adults with autism spectrum disorder. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Barneveld PS, Swaab H, Fagel S, van Engeland H, de Sonneville, Leo M. J. Quality of life: A case-controlled long-term follow-up study, comparing young high-functioning adults with autism spectrum disorders with adults with other psychiatric disorders diagnosed in childhood. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(2):302–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Cai RY, Richdale AL, Dissanayake C, Uljarević M. Resting heart rate variability, emotion regulation, psychological wellbeing and autism symptomatology in adults with and without autism. Int J Psychophysiol. 2019;137:54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Samson AC, Antonelli Y. Humor as character strength and its relation to life satisfaction and happiness in autism spectrum disorders. Humor. 2013;26(3):477–491. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Gal E, Selanikyo E, Erez AB, Katz N. Integration in the vocational world: How does it affect quality of life and subjective well-being of young adults with ASD. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(9):10820–10832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Schmidt L, Kirchner J, Strunz S, et al. Psychosocial functioning and life satisfaction in adults with autism spectrum disorder without intellectual impairment: Psychosocial functioning in autism. J Clin Psychol. 2015;71(12):1259–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Deserno MK, Borsboom D, Begeer S, Geurts HM. Relating ASD symptoms to well-being: Moving across different construct levels. Psychol Med. 2018;48(7):1179–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Pearlman-Avnion S, Cohen N, Eldan A. Sexual well-being and quality of life among high-functioning adults with autism. Sex Disabil. 2017;35(3):279–293. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Feldhaus C, Koglin U, Devermann J, Logemann H, Lorenz A. Students with autism spectrum disorders and their neuro-typical peers – differences and influences of loneliness, stress and self-efficacy on life satisfaction. Univ J Educ Res. 2015;3(6):375–381. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Nilsson M, Handest P, Carlsson J, et al. Well-being and self-disorders in schizotypal disorder and asperger syndrome/autism spectrum disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208(5):418–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Parsons S. ‘Why are we an ignored group?’ Mainstream educational experiences and current life satisfaction of adults on the autism spectrum from an online survey. Int J Incl Educ. 2015;19(4):397–421. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Young L. Finding our voices, singing our truths: Examining how quality of life domains manifested in a singing group for autistic adults. Voices World Forum Music Ther. 2020;20(2):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 85. Milton D, Sims T. How is a sense of well-being and belonging constructed in the accounts of autistic adults? Disabil Soc. 2016;31(4):520–534. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Smith SJ, Powell JE, Summers N, Roulstone S. Thinking differently? Autism and quality of life. Tizard Learn Disabil Rev. 2019;24(2):66–76. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Gee JP. An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. 4th ed. New York: Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Fairclough N. Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Wodak R, Fairclough N. Critical discourse analysis. In: van Dijk TA, ed. Discourse as Social Interaction. London: Sage; 1997;258–284. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Gee JP. How to Do Discourse Analysis: A Toolkit. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 91. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 92. World Health Organization. World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:1403–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Hunt SM. The problem of quality of life. Q Life Res. 1997;6(3):205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. McClimans L. Towards self-determination in quality of life research: A dialogic approach. Med Health Care Philos. 2010;13(1):67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Chappell AL. Towards a sociological critique of the normalisation principle. Disabil Handicap Soc. 1992;7(1):35–51. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Runswick-Cole K, Curran T, Liddiard K, eds. The Palgrave Handbook of Disabled Children's Childhood Studies. London: Macmillan; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ashby CE. Whose” voice” is it anyway?: Giving voice and qualitative research involving individuals that type to communicate. Disabil Stud Q. 2011;31(4). DOI: 10.18061/dsq.v31i4.1723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Biggs EE, Carter EW. Quality of life for transition-age youth with autism or intellectual disability. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(1):190–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Prilleltensky I. Critical psychology foundations for the promotion of mental health. Ann Rev Crit Psychol. 1999;1(1):100–118. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Cusack J. Participation and the gradual path to a better life for autistic people. Autism. 2017;12(2):131–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Chadderton C. Not capturing voices? In: Czerniawski G, Kidd W, eds. The Student Voice Handbook: Bridging the Academic/Practitioner Divide. Bingley: Emerald; 2011;73–85. [Google Scholar]

- 102. Milton D. Autistic development, trauma and personhood: Beyond the frame of the neoliberal individual. In: Runswick-Cole K, Curran T, Liddiard K, eds. The Palgrave Handbook of Disabled Children's Childhood Studies. London: Macmillan; 2018;461–476. [Google Scholar]

- 103. Warner G, Parr JR, Cusack J. Workshop report: Establishing priority research areas to improve the physical health and well-being of autistic adults and older people. Autism Adulthood. 2019;1(1):2–26. [Google Scholar]

- 104. Urbanowicz A, Nicolaidis C, den Houting J, et al. An expert discussion on strengths-based approaches in autism. Autism Adulthood. 2019;1(2):82–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Gratton FV. Supporting Transgender Autistic Youth and Adults: A Guide for Professionals and Families. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 106. Walker N. Somatics and autistic embodiment. In: Johnson DH, ed. Diverse Bodies, Diverse Practices: Towards an Inclusive Somatics. California: North Atlantic Books; 2018;89–120. [Google Scholar]

- 107. Douglas P, Rice C, Runswick-Cole A, et al. Re-storying autism: A body becoming disability studies in education approach. Int J Incl Educ. 2019:1–18. DOI: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1563835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]