Research on autism has long been focused on childhood. However, it is now widely accepted that autistic children become autistic adults and it is increasingly recognized that autistic people spend the majority of their lives as adults. This lifespan perspective has led to efforts to expand research on autism in adulthood. In tandem with recognition of the existence of autistic adults and, therefore, the need to study their lives, priorities, and needs, there have been efforts to promote respect and inclusion of autistic people in research about their lives.1,2 These efforts align with the broader disability rights movement (e.g., “nothing about us without us”3,4), and have propelled paradigm shifts that are transforming the latest generation of autism research. This journal—Autism in Adulthood—was created to provide a home for this emerging field, emphasizing research and scholarship centered on issues important to autistic adults.5 Two years after the journal's launch, this special issue on the state of the science in autism in adulthood offers an opportunity to take stock and reflect on the progress that has been made.

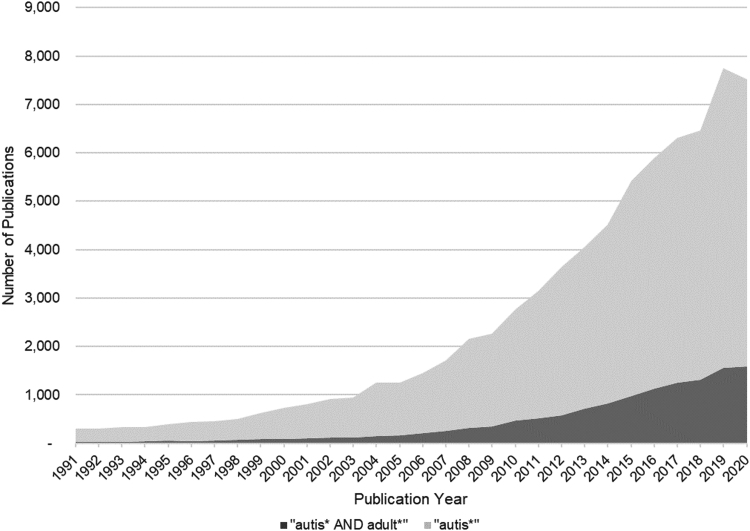

Once a nonexistent and more recently a nascent field of inquiry, research on autism in adulthood has grown tremendously over the past three decades. A topic search on Web of Science we conducted using the terms “autis* AND adult*” demonstrates this expansion: between 1991 and 2000, 544 articles were published, between 2001 and 2010, 2,252 articles were published, and between 2011 and 2020, 10,469 articles were published. While the growth of adult autism research is considerable, it has come as part of a larger wave of increased publications on autism broadly. That is, as societal attention on autistic individuals has increased,6 autism research writ large has experienced corresponding increases. However, when viewed together (Fig. 1), research on autism in adulthood has not expanded at the same rate as general autism research. Progress has been made: we see the proportion of adult-focused autism research approximately doubled over 30 years—in 1991, 10%, and in 2020, about 21% of autism publications included the “adult*” term. However, attention to autism in childhood continues to take center stage. Growth in funding opportunities related to autism in adulthood has been even more modest, and is likely a factor slowing scientific advances that can improve the lives of autistic adults.7

FIG. 1.

Thirty-year growth in number of publications on autism in adulthood (dark gray) and autism broadly (light gray).

The number of publications and funding opportunities in a field offer only a narrow perspective on progress. The quality and characteristics of this growing area of inquiry are equally as important. For example, are we making scientific advances in areas important to autistic adults? Does research pathologize autism or espouse a neurodiversity framework? Are autistic adults influencing the research trajectory? Articles in this special issue on the state of the science address critical questions in the field and focus on topics important to autistic adults. For example, quality of life and well-being are among the top priorities for autistic adults as they seek to live meaningful enriching lives.8 An article by Lam and colleagues critically examines the conceptualization of well-being in autism research and offers a path forward. Autistic adults have also identified mental health as a priority area.8,9 Special issue articles offer deep dives into the state of the science on the mental health of autistic postsecondary students and autistic masking and mental health. Autistic adults have also endorsed activities of daily living (ADLs) as an important outcome, noting that advances in this domain can improve their lives. The article by Krempley and Schmidt explores the tools available for assessing ADLs for autistic adults and makes recommendations to improve ADL assessment in ways that are meaningful to autistic adults. The understudied, yet critically important, topic of pregnancy and parenthood is examined in an article by McDonnell and DeLucia. These articles demonstrate significant progress on the state of the science in areas of importance to autistic adults, while also highlighting gaps and future directions needed for growth.

Autism in Adulthood seeks to not only encourage research on topics important to autistic adults, but also to transform how that research is conceived, carried out, and shared. A goal of the journal is to cultivate anti-ableist autism research. That is, research that situates autism as part of human diversity, that sees strengths and opportunities to alter environments rather than individual-level pathologies that require “fixing,” and that enables autistic adults to have a say over science including what is funded, what is studied, and how the resulting information is used (e.g., inclusion on bodies that shape funded priorities and decide what is funded participatory research). Articles in this special issue advance these goals as well. Take, for example, Dora Raymaker's interview with Nick Walker on neurodiversity that offers an in-depth examination of its framework, history, and impact on science, as well as the perspective piece by Bottema-Beutel and colleagues on how autism researchers can embody neurodiversity and eradicate ableist language. It is also significant that many of the special issue articles, and notably all of the perspectives articles, include autistic authors—another important means through which to cultivate anti-ableist scholarship and enhance the lives of autistic adults.

Finally, Autism in Adulthood is committed to publishing research across the translational spectrum, including new evidence and ideas that can engender positive social impacts for autistic adults. Toward that end, this special issue contains articles examining the impact of community-based interventions targeted at improving the lives of autistic adults. Duerksen et al. offer an in-depth look at peer-mentoring programs used in postsecondary education settings to support autistic students' success. McGee Hassrick et al. examine the state of research on internet-mediated communication among autistic people. To enhance the field's attention to fueling knowledge to practice, we held an expert discussion on knowledge translation, which explores opportunities for adult autism research to effectively support positive changes. For the expert discussion, we gathered a panel with diverse personal and professional experiences. They offer examples of translating adult autism research in additional areas important to autistic adults, including employment and health care, and provide recommendations for ways autism in adulthood researchers can proactively encourage the translation of new knowledge to new practices and policies.

As we reflect on the state of the science on autism in adulthood, we are not surprised to find that there is still much work to do to create a robust and rigorous evidence base on topics valued by autistic adults. As we developed this special issue, we worked with authors who desired to conduct systematic reviews on high-priority topics, yet available research was often too sparse. In cases where more research was available, we further observed that the state of the evidence is still emerging in many areas. To address gaps in the state of the science, it is critical that scholars continue to advocate for increased funding on autism in adulthood and, in particular, for projects that address areas of importance to autistic stakeholders, meaningfully involve autistic stakeholders (including being led by autistic researchers), are respectful to autistic people and based upon neurodiversity principles, reflect the diversity of the autistic community, and can be translated into real-world advances. To most effectively do this, collaboration and coordination will be critical—working together across professional disciplines, stakeholder groups, and borders to foster innovation and maximally impactful research. We also need to continue to prioritize welcoming and supporting new scholars to become leaders in these efforts, including autistic scholars who can integrate their lived experiences into their scholarship.

As autism in adulthood research matures, it is important to continue to evaluate the field's progress. Taking stock through synthesizing and evaluating available research is an essential step toward building a strong evidence base that promotes change at all levels so that autistic adults flourish. Assessments of the state of the science also enable us to identify key gaps in the knowledge base. This special issue provides a window into some of the advances in the field of autism in adulthood research. Autism in Adulthood is a welcome home for new scholarship that is relevant to adulthood, responsive to community priorities, from autistic scholars and academic–community partnerships, and strives to reduce knowledge-to-practice gaps. We hope this special issue inspires further growth in meaningful advances toward translational research aimed at improving the lives of autistic adults.

References

- 1. Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, Kapp SK, et al. The AASPIRE practice-based guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults in research as co-researchers and study participants. Autism. 2019;23(8):2007–2019. DOI: 10.1177/1362361319830523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pellicano E, Dinsmore A, Charman T. What should autism research focus upon? community views and priorities from the United Kingdom. Autism. 2014;18(7):756–770. DOI: 10.1177/1362361314529627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Charlton J. Nothing About us Without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment. Berkeley, California: University of California Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shapiro J. No Pity: People with Disabilities Forging a New Civil Rights Movement. New York, New York: Three Rivers Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nicolaidis C. Autism in Adulthood: The new home for our emerging field. Autism Adulthood. 2019;1(1):1–3. DOI: 10.1089/aut.2018.28999.cjn [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grinker RR. Unstrange Minds: Remapping the World of Autism. New York, New York: Basic Books; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee. 2016–2017 Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee strategic plan for autism spectrum disorder. Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee. https://iacc.hhs.gov/publications/strategic-plan/2017/. Published 2017. Accessed January 21, 2021.

- 8. Benevides TW, Shore SM, Palmer K, et al. Listening to the autistic voice: Mental health priorities to guide research and practice in autism from a stakeholder-driven project. Autism. 2020;24(4):822–833. DOI: 10.1177/1362361320908410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Your research priorities. Autistica. https://www.autistica.org.uk/downloads/files/Autism-Top-10-Your-Priorities-for-Autism-Research.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2020.