Abstract

In this commentary, we describe how language used to communicate about autism within much of autism research can reflect and perpetuate ableist ideologies (i.e., beliefs and practices that discriminate against people with disabilities), whether or not researchers intend to have such effects. Drawing largely from autistic scholarship on this subject, along with research and theory from disability studies and discourse analysis, we define ableism and its realization in linguistic practices, provide a historical overview of ableist language used to describe autism, and review calls from autistic researchers and laypeople to adopt alternative ways of speaking and writing. Finally, we provide several specific avenues to aid autism researchers in reflecting on and adjusting their language choices.

Lay summary

Why is this topic important?

In the past, autism research has mostly been conducted by nonautistic people, and researchers have described autism as something bad that should be fixed. Describing autism in this way has negative effects on how society views and treats autistic people and may even negatively affect how autistic people view themselves. Despite recent positive changes in how researchers write and speak about autism, “ableist” language is still used. Ableist language refers to language that assumes disabled people are inferior to nondisabled people.

What is the purpose of this article?

We wrote this article to describe how ableism influences the way autism is often described in research. We also give autism researchers strategies for avoiding ableist language in their future work.

What is the perspective of the authors?

We believe that ableism is a “system of discrimination,” which means that it influences how people talk about and perceive autism whether or not they are aware of it, and regardless of whether or not they actually believe that autistic people are inferior to nonautistic people. We also believe that language choices are part of what perpetuates this system. Because of this, researchers need to take special care to determine whether their language choices reflect ableism and take steps to use language that is not ableist.

What is already known about this topic?

Autistic adults (including researchers and nonresearchers) have been writing and speaking about ableist language for several decades, but nonautistic autism researchers may not be aware of this work. We have compiled this material and summarized it for autism researchers.

What do the authors recommend?

We recommend that researchers understand what ableism is, reflect on the language they use in their written and spoken work, and use nonableist language alternatives to describe autism and autistic people. For example, many autistic people find terms such as “special interests” and “special needs” patronizing; these terms could be replaced with “focused interests” and descriptions of autistic people's specific needs. Medicalized/deficit language such as “at risk for autism” should be replaced by more neutral terms such as “increased likelihood of autism.” Finally, ways of speaking about autism that are not restricted to particular terms but still contribute to marginalization, such as discussion about the “economic burden of autism,” should be replaced with discourses that center the impacts of social arrangements on autistic people.

How will these recommendations help autistic people now or in the future?

Language is a powerful means for shaping how people view autism. If researchers take steps to avoid ableist language, researchers, service providers, and society at large may become more accepting and accommodating of autistic people.

Keywords: autism, ableism, language, ableist discourse, neurodiversity

Introduction

The purpose of this commentary is to define, describe, and offer alternatives to ableist language used in autism research. According to the Center for Disability Rights, ableism “is comprised of beliefs and practices that devalue and discriminate against people with physical, intellectual, or psychiatric disabilities and often rests on the assumption that disabled people need to be ‘fixed’ in one form or the other.”1 The effects of ableism on autistic people include, but are not limited to, underemployment, mental health conditions, and victimization.2–6 The motivation for this article stems from ongoing discussions between autism researchers and the autistic community,7–9 with noteworthy contributions from individuals who belong to both groups.10–15 We prioritize the perspectives of autistic people because they have first-hand expertise about autism and have demonstrated exceptional scientific expertise.16 Autistic adults have led advocacy against ableist language, with broad applicability across age groups. The autistic community advocates for autism research that is accessible, inclusive of autistic participation and perspectives, reflective of the priorities of the autistic community, of high quality, and written in such a way that it does not contribute to the stigmatization of autistic people.10,12,17–19 Although there has been progress on these fronts,20 some of the language used to describe autism and autistic people within published research continues to increase marginalization.15,21–24

In an effort to improve researchers' language practices, we discuss these issues in five sections. First, we discuss the relevance of ableism to autism research. Second, we discuss the ramifications of ableist language choices and give a historical overview of how such language persists in autism research. Third, we review empirical research on the language preferences of the autistic community. Fourth, we discuss recent language debates, focusing on objections made by autism researchers to some nonableist language options. Finally, we provide practical strategies for avoiding ableist language and provide suggested alternatives in Table 1, which will be discussed in detail in the Suggestions for Researchers section.

Table 1.

Potentially Ableist Terms and Discourse That Commonly Appear in Autism Research and Suggested Alternatives

| Potentially ableist term/discourse | Suggested alternatives |

|---|---|

| Patronizing language | |

| Special interests99 | Areas of interest or areas of expertise, focused, intense, or passionate interests |

| Special needs98,100,101 | Description of specific needs and disabilities |

| Challenging behavior/disruptive behavior/problem behavior7,37,102,103 | Meltdown (when uncontrollable behavior), stimming (when relevant), specific description of the behavior (e.g., self-injurious or aggressive behavior) |

| Person-first language (to refer to autism)8,17,65,72,104–107 | Identity-first language; “on the autism spectrum” |

| Medicalized/deficit-based language | |

| High/low functioning; high/low severity or support needs9,17,84,85 | Describe specific strengths and needs, and acknowledgment that the level of support needs likely varies across domains (e.g., requires substantial support to participate in unstructured recreation activities, but minimal support to complete academic work) |

| “At risk” for ASD73 | Increased likelihood/chance of autism |

| Burden of/suffering from autism108 | Impact, effect |

| Co-morbid109,110 | Co-occurring |

| Autism symptoms17 | Specific autistic characteristics, features, or traits |

| Treatment | Support, services, educational strategies (when applicable) |

| Healthy controls/normative sample111,112 | Nonautistic (if determined via screening), neurotypical (if determined via extensive screening ruling out most forms of neurodivergence), comparison group (with description of relevant group characteristics) |

| Psychopathology98 | Neurodevelopmental conditions, neuropsychiatric conditions, developmental disabilities, mental illnesses (or specific mental health condition) |

| Ableist discourses: ways of discussing autism not relegated to the use of particular terms, that reflect and/or contribute to dehumanization, oppression, or marginalization of autistic people | |

| Discussions about economic impacts of autism that situate costs in the existence of autistic people themselves, or compare the costs to those of potentially fatal diseases/conditions such as cancer or stroke.113 | Discussions about economic impacts of autism that situate costs in society's systemic failure to accommodate autistic people and that recognize the people most affected by oppression due to this failure are autistic people themselves (not “taxpayers”) |

| Interpretations of all group differences between autistic and nonautistic groups as evidence of autistic deficits20,22,29,114 | Interpretations of group differences that consider the possibility that autistic people may have relative strengths over nonautistic people or that differences between groups are value-neutral unless actively demonstrated otherwise |

| Cure/recovery/“optimal outcome” rhetoric.115,116 | Discussions focusing on quality-of-life outcomes that prioritize what autistic people want for themselves |

| Prioritizing “passing” as nonautistic (e.g., some “social skills” training) at the expense of mental health and well-being.35,117,118 | Prioritizing mental health and well-being, which can include embracing autistic identities |

| Autism as a puzzle.119,120 | Autism as part of neurodiversity |

| Autism as an epidemic.121 | Autism as increasingly recognized/diagnosed |

We bring expertise in special education, psychology, and occupational therapy and hope to express a range of concerns across these disciplines. The second author is also an autistic researcher, with expertise in neurodiversity and autism advocacy. While we do not claim to be comprehensive in our discussion of these issues, we can provide insight on a range of language practices that occur across disciplines, which may render our discussion useful for those in a variety of research traditions.

What Does Ableism Have to Do with Autism Research?

Ableism is perpetuated by culturally shared norms and values, as well as ways of speaking and writing about disability and disabled people. These social processes culminate in, and originate from, societal expectations about the abilities required for granting individuals full social rights, agency, and even personhood.25 Ableism intersects with other systems of oppression, including racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia.26,27 This means that ableism is compounded by experiences such as racism. In addition, disabled people of color are more likely to experience the effects of ableism than white disabled people.28

Understanding the concept of ableism, and how it manifests in language choices, is critical for researchers who focus on marginalized groups such as the autistic community. Since autism was first identified by researchers, deficit discourses have pervaded descriptions of autistic research participants.29 In fact, some interpretations of research findings have tacitly or explicitly questioned the humanity of autistic people.30–32 Autistic rhetorician Melanie Yergeau offers an example from theory of mind research, which showed differences between autistic and nonautistic groups on false belief task performance. This finding was used as evidence that autistic people lack an essential element that “makes us human.”14 This type of ableist discourse can have far-reaching negative impacts on disability policy, education, therapeutic practices, and social attitudes about autistic people.25,33 When, for instance, research findings are presented as evidence that autistic people are “emotionless,”34 they may influence public perceptions about autistic people that are incorrect and negatively impact their ability to form relationships and participate in society. In this way, language choices can perpetuate stigma, increase marginalization, and contribute to negative internalized self-beliefs within autistic people.35–37 In many parts of the world, ableism is a default system of discrimination that can be reinforced through language and other symbolic modalities.38,39 Researchers who wish to counteract this system must therefore adopt an anti-ableist stance and be intentional about their language choices. We believe that such a commitment will result in less discriminatory and more accurate discussions of research findings.

The Impact and History of Language Used to Talk About Autism

Why does the language we use to talk about autism matter?

Language is not simply descriptive but is also performative.40 That is, language use is constructive of social life; through language we make a case, take a particular stance, and produce identities.41 What people say or write produces specific versions of the world, one's self, and others,42 and language conveys, shapes, and perpetuates ideologies.43 Language choices are also reflective of power structures and mirror dominant narratives and ideologies about social phenomena. From this critical perspective, ideologies are conceptualized in such a way that includes consideration of the role of power in the “positions, attitudes, beliefs, perspectives, etc. of social groups”42 (p. 9). Thus, ideologies evidenced in everyday and institutional discourse are assumed to both establish and maintain power relationships.42 Disrupting dominant discourses about autism, primarily controlled by those in positions of power, is therefore necessary to change conceptualizations about the nature of autism. Additionally, all communication involves language choices, and there are no “neutral” options independent of an ideological stance.44

The fact that representations of research participants and results are shaped by research biases, and may not accurately reflect how participants perceive themselves, has long been emphasized in qualitative methodological literature.45–47 Furthermore, social science researchers produce various versions of reality, theory, and descriptions of people and places when writing research reports.48 As such, researchers' language choices shape how people and places come to be known.

Historical reflections on language about autism

Autism arose as a clinical category in the 1940s, but descriptions of autism have varied across time and place and are shaped by complex disciplinary histories and discourses.49 The works of Leo Kanner and Hans Asperger continue to influence how autism is understood. While Kanner is typically credited with classifying autism as a diagnostic category, Eugene Bleuler first coined the term in 1911, using it to describe “psychotic patients” tendency to withdraw into fantastical worlds.50 During the 1920s and 1930s, the term “schizophrenic autism” was used to describe children who appeared to separate from reality and become affectively withdrawn.

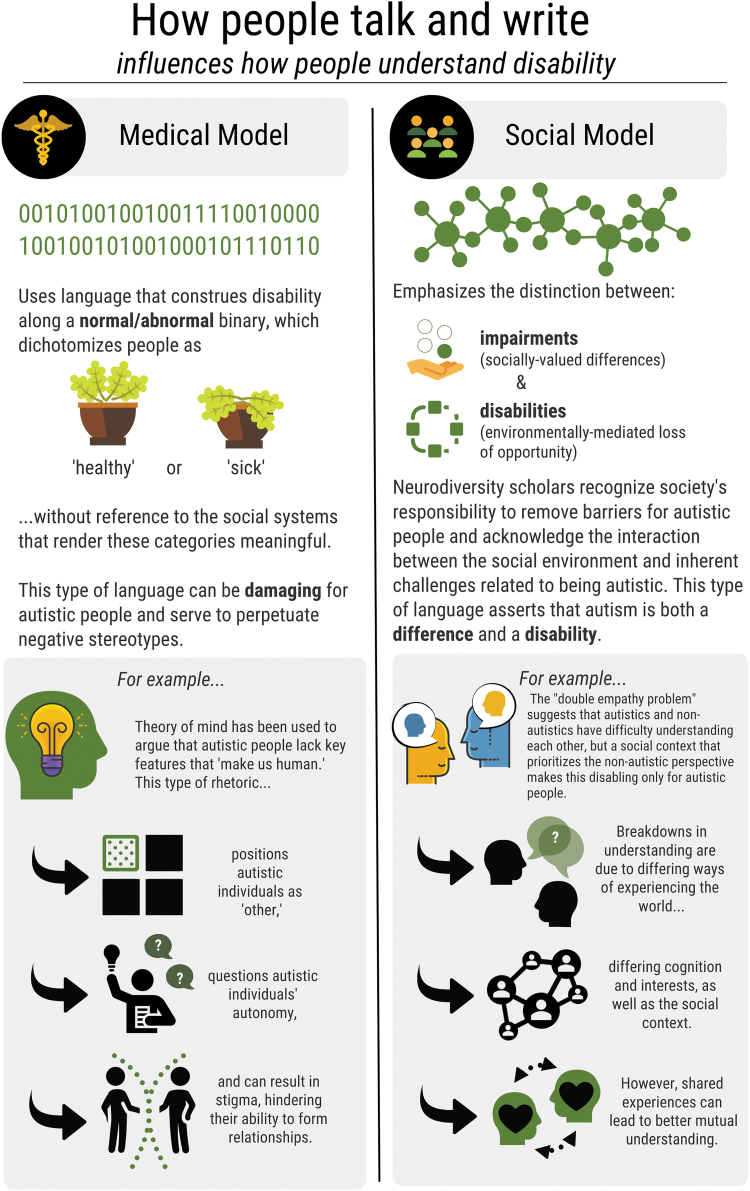

Even recently, autism is often written about using medical model frameworks, which construe all differences associated with autism to be evidence of deficits, and advocates for curing these deficits via intervention.51 In keeping with the medical model, autism has linguistically, culturally, and politically been constructed in relation to a normal/abnormal binary.52 Canguilhem53 noted that a “normal or physiological state is no longer simply a disposition which can be revealed and explained as fact, but a manifestation of an attachment to some value” (p. 57). The medical model traditionally dichotomizes people as “healthy” and “sick” or “non-disabled” and “disabled,” without reference to the social systems that render these categories meaningful, and with the assumption that disability is inherently inferior to nondisability. Treatment is administered in hopes of transforming disabled individuals into nondisabled individuals.54 The medical model, therefore, inherently relies on deficit construals of autism, even though both Kanner55 and Asperger56 noted autistic strengths.

In the medical model, autism is “essentially a narrative condition … diagnoses of autism are essentially storytelling in character, narratives that seek to explain contrasts between the normal and the abnormal, sameness and difference”57 (p. 201). Autism diagnosis, even when observational tests or interviews are administered, largely relies on subjective interpretations of behavior. Indeed, the medical model of disability centers on identifying autism by assessing behaviors and interactions with others. As such, it constructs autism as a within-person phenomenon, even though the condition is diagnosed through social behavior. These conceptualizations of autism locate the source of impairment in autistic people who may have difficulty understanding nonautistic social behavior but do not question why nonautistic people experience the same difficulty in understanding autistic social behavior (this is termed “the double empathy problem”).11,13

In contrast, the social model distinguishes between impairments, which are socially valued differences in functioning or appearance, and disabilities, which are environmentally mediated and emphasize the loss of opportunities to participate in society.58 Under this framework, autism is disabling in societies that do not make efforts to remove barriers to participation that autistic people face.59 For example, autism can be disabling when an autistic person seeks employment but is not accommodated for communication differences that impact their ability to participate in an interview.

Current conceptualizations of the social model acknowledge that social barriers do not explain all aspects of disability and recognize individual contributions in the context of a disabling society.60 Proponents of the autistic-led neurodiversity movement conceptualize autism in such a way that autism itself can be celebrated while still recognizing impairments and support needs.61 Neurodiversity scholars and activists: (1) recognize that barriers imposed by nonautistic society hinder the fulfillment of autistic people and assert that it is a societal responsibility to remove these barriers59; and (2) acknowledge the transaction between inherent weaknesses of autism and the social environment, viewing autism as both a difference and a disability.11,61–63 Therefore, they support an integrative model of disability, which values impairment as a valid form of human diversity12,64 and dovetails with the nuanced views of autism among autistic adults.16,65

Inspired by the disability rights movement, Sinclair served as the primary founder of the neurodiversity movement and its use of identity-first language.66 Sinclair's67 essay “Why I Dislike Person First Language” is a foundational text that explains why many neurodiversity advocates prefer identity-first language such as “autistic person.” This piece explains autism as inseparable from and fundamental to an individual's experience of the world. Perhaps most controversially, Sinclair critiques the need to emphasize personhood as paradoxically dehumanizing (“Saying person with autism suggests that autism is something so bad that it isn't even consistent with being a person,” para. 3). While person-first constructions were originally promoted by self-advocates with intellectual disability (ID) in the late 1960s and 1970s, becoming widespread by the 1990s as the self-advocacy movement came of age,68 many within the autistic community now reject them. Neurodiversity proponents may recognize that supporters of either language preference may share the value of upholding autistic people's dignity and worth but disagree on rhetorical means for doing so.8

The positioning of autism as an entity that can be discovered in one's genetics, neurological systems, or biochemistry49,51 “implies a lack of reflexivity about how autism is constructed through our representational practices in research, in therapy, and in popular accounts”69 (p. 20). Medicalized representations of autism rarely include consideration of the experiences and everyday practices of autistic people. Historically, disabled people have rarely been allowed to “control the referent ‘disability’” and the “terminology that has been used to linguistically represent the various human differences referred to as ‘disabilities’”70 (p. 122). This type of medical-model rhetoric has material consequences for shaping research agendas. Presently, several funding initiatives promote prevention research (with the goal of eradicating autistic people) and certain strands of intervention research that attempt to teach autistic people to pass as nonautistic. Both these avenues of research ignore aspects of disability that are socially mediated, which requires social and structural changes to how autistic people are viewed, valued, and treated in lieu of efforts to exclusively change autistic people. See Figure 1 for an infographic contrasting the medical and social models.

FIG. 1.

Infographic contrasting medical and social models of disability.

Current Research on the Language Preferences of the Autistic Community

Formal research characterizing language preferences of autistic people is emerging.71 This research highlights discrepancies in the language used by health care professionals and that which is preferred by autistic adults and other members of the autism community (e.g., family members, friends), particularly surrounding identify-first versus person-first language.17 Whereas autistic adults in the United Kingdom endorsed “autistic” and “autistic person” in greater numbers than “person with autism,” professionals endorsed “person with autism” in greater numbers than “autistic” or “autistic person.” Parents were also much less likely to endorse “autistic person” than were autistic participants.

Research on Australian samples has shown that autistic people rated the terms “autistic,” “person on the spectrum,” and “autistic person” significantly higher than “person with autism,” “person with ASD” (autism spectrum disorder), and “person with ASC” (autism spectrum condition). U.S.- and U.K.-based research has shown that self-identification as autistic and awareness of the neurodiversity movement are associated with stronger preferences for the term “autistic person” over “person with autism.”65 Data suggest that “on the autism spectrum” may be the least polarizing way to refer to autism,17,72 but even using this description is a political decision.

Outside identifying language, there is some evidence to suggest relative consensus among stakeholder groups about other preferred language choices. For example, Kenny et al.17 found few autistic adults, family members/friends, or health care professionals endorse the use of functioning-level descriptors such as “high-functioning” autism (approximately 20% endorse) and “low-functioning” autism (<10% endorse). Additionally, most autistic adults and other stakeholders prefer the use of diversity-focused language (e.g., neurodiversity) as opposed to phrases such as disability, deficit, or disorder.17 Furthermore, evidence suggests autism community members predominantly prefer probabilistic language over danger-oriented terms. For example, the terms “infants with high autism likelihood” or “infants with higher chance of developing autism” are preferred over terms such as “at-risk” when describing infants with autistic siblings.68

It is worth noting that this work largely describes the preferences of English-speaking research participants, a disproportionate amount of whom are white. Additionally, as most studies were surveys, it is unclear the extent to which these preferences represent those of autistic people with marked impairments in written communication and/or intellectual functioning that may hinder their ability to participate in survey research. Further work is needed to understand language preferences of autistic people from diverse racial, ethnic, linguistic, and cultural backgrounds, and those with a range of communication and intellectual abilities. Finally, quantitative survey approaches should be supplemented with qualitative analyses of language-in-use, to understand how language choices are implicated in everyday experience.

Ongoing Controversies Around Language Usage

Many autism researchers may be unaware of how language forms can reflect ableist ideologies. Other researchers who are aware of the potentially ableist implications of some terms and discourses, but continue to use them in their work, may appeal to three commonly used arguments for this choice: (1) a lack of complete consensus from the autistic community on their language preferences, (2) concerns about a lack of scientific accuracy conveyed by nonableist language, and (3) misunderstandings about terms that originated from autistic and other disabled advocates. In this section, we address each of these arguments and provide a rationale for why researchers should continue to make efforts to audit their written and spoken work so as to avoid ableist language.

Lack of consensus

Even when polling is available to identify group-level language preferences, controversy remains as to the representativeness of samples of autistic people. Whether researchers should replace person-first language with identity-first language has received particular attention recently.74 An argument primarily put forward by nonautistic researchers for why autistic people's preferences should not lead to changes in their language practices is that there remain members of the autistic community who prefer person-first constructions over identity-first constructions,69 or are unable to participate in discussions about language preferences because of communication impairments.

We contend that this line of reasoning works to maintain the status quo by allowing nonautistic researchers to avoid engagement with the expressed preferences of many members of the autistic community, and discount or minimize their arguments around language choices. Complete consensus is unlikely to be gained for a set of terms for any marginalized community. Yet, it remains important to avoid using language with known stigmatizing effects (unless referring to a specific individual who has indicated their language preferences), such as many usages of person-first language.71 Stakeholders (including parents) may eventually move toward consensus on preference for identity-first language, because it is positively correlated with the growing awareness of the neurodiversity movement that also increases acceptance of and positive emotions toward autism.65 While it is the case that nonspeaking autistic people with profound communication impairment cannot have their views directly incorporated into the neurodiversity movement, nonspeaking autistic people do participate, as do those who formerly did not have an effective means to communicate, but now do.75,76 Additionally, speaking individuals in this movement consider the unique needs of communication-impaired autistic people in their advocacy surrounding language choices, such as support for augmentative and alternative communication.61–63 Likewise, many caregivers of communication-impaired autistic people align themselves with neurodiversity proponents when advocating for their children.77,78

We recommend that researchers consider the majority preferences for particular language (which could involve polling their research participants as part of standard data collection methods), the specific arguments made by autistic community members when articulating their preferences, and existing recommendations by academic and professional organizations to respect the majority language preferences of the group being referred to.79,80 We recommend that journals not require person-first language, and researchers still disinclined to adopt identity-first language may opt for the relatively neutral term “on the autism spectrum.” This may be especially important for autistic people with ID given the language disagreements between the self-advocacy and neurodiversity movements.

Concerns about accuracy

A second reason researchers may choose not to adopt nonableist language is because they believe that it inaccurately or imprecisely represents their research findings. However, as several examples illustrate, the opposite is often true. Ableist language, and the implicit assumptions that underlie it, clouds research findings in ways that are not helpful to researchers or autistic communities.31 In this section, we review several examples of this phenomenon.

Autistic people without ID are sometimes referred to as “high-functioning,” with the assumption that these individuals will function better than autistic individuals with ID (often referred to as “low functioning”). Autistic people have argued against the use of these labels both because they are stigmatizing, and because they inaccurately reflect their experience. An autistic individual's intellectual and adaptive functioning can vary significantly across domains (i.e., so-called “spiky” cognitive profiles); for example, hyperlexia can co-occur with dyscalculia.76,81 This suggests that “intellectual ability” is not uniformly distributed for any given autistic person, and blanket-level functioning labels may mask this reality. Functioning can also vary across time and context and may depend more on the adequacy of supports provided than on the presence or absence of ID.9 For example, autistic people without ID more often experience a drop-off in services following high school, whereas those with ID are more likely to transition into a supported context (e.g., supported employment, organized daytime activities).82,83

Recent empirical research supports these criticisms; measures of adaptive functioning do not correlate with measures of intellectual ability in autistic children,84 and the divergence between these two domains tends to increase with higher age and IQ scores.85 Functioning labels are therefore not only inaccurate, but they can also result in situations where autistic people labeled “high functioning” are not provided with the supports they need, while autistic people labeled “low functioning” are underestimated in regard to their actual capabilities.9 We encourage researchers to replace terms such as “high-” and “low-functioning” with descriptors of the characteristics they intend to convey (e.g., ID).

Another instance of this phenomenon is when autistic people are described as “severely” affected, without including specific information about what contributes to this classification. Researchers may mean to convey ID, structural language impairment, or substantial support needs. These characteristics often, but not always, co-occur, and researchers should specify the characteristics they are indicating when using the term.85 Other similar examples of a lack of precision in terminology include “challenging behavior” and “autistic traits.” These terms have different meanings across studies, making comparisons between research findings more difficult. “Challenging behavior,” for instance, is a value-laden phrase that does not specify what the behavior is, indicate who perceives the behavior as challenging and why, or consider the possible adaptive value the behavior has for the person employing it.7 Likewise, “autistic traits” is sometimes used by researchers as a catchall phrase for autistic characteristics that extend into the general population when present at less impactful degrees. However, autism consists of a constellation of traits that vary in presence, intensity, and function across individuals. As such, the term “autistic traits,” while not problematic in itself, should not be used for distinguishable and uncorrelated characteristics. The Autism Quotient,86 a measure purporting to quantify autistic traits, includes subscales measuring distinct autistic traits that are weakly associated, suggesting the overall score of “autistic traits” lacks coherent meaning.87 The term “autistic traits” is also rarely used to refer to autistic advantages or neutral characteristics, and therefore may offer a biased view of what constitutes “autistic traits.”

A final example in this category is using “typically developing” or “neurotypical” to describe participants serving as a reference group. Although these terms are meant to indicate participants do not meet criteria for clinical diagnoses, this is rarely assessed. Many researchers assess the comparison group for autism and may employ some basic exclusionary criteria for large disqualifiers such as substance abuse, but most do not screen for relatively common clinical conditions such as anxiety, ADHD, and depression. Given that many people meet criteria for some clinical condition at some point during their lives,88 groups labeled “neurotypical” include individuals with clinically relevant features that go unaccounted for. This is not to suggest that researchers should always screen for the presence or history of all clinical conditions—doing so is often resource-prohibitive. Rather, we note that the term “neurotypical” is often misleading and promotes the assumption that any nonautistic person is “typical.” Researchers might instead label their comparison group “non-autistic,” if they conducted appropriate screeners. The term “comparison group” is preferred to “control group” because autism is not an experimentally manipulated assigned condition, so full “control” of all variables besides autism between groups is impossible.

Misunderstanding terms

A third controversy involves researchers using terms in ways other than how they are used by the disability community that coined them. Neurodiversity is a term that has been used and written about by several autistic scholars, but may be new to some autism researchers. The neurodiversity framework conceptualizes autism as a natural form of human variation, inseparable from individuals' identity, and not in need of a cure or normalization.61 Recently, calls for tempering the claims put forward by neurodiversity proponents have been made by nonautistic researchers.89,90 However, some of this pushback is couched in inaccurate representations of neurodiversity as both a concept and a movement. Some may purport that neurodiversity focuses on strengths without reference to disablement, which is inaccurate.65,91 Calls for temperance of the neurodiversity framework categorize specific autistic features as either “disabilities” or “differences,” but this is a false dichotomy.65 The extent to which differences constitute impairments, which can in turn be disabling, requires reference to the supports that are provided (or not) in particular environments, and the sociocultural contexts in which particular abilities are valued (or not). These misrepresentations of terms set the stage for arguments that distort and over-simplify the neurodiversity framework. This in turn reinforces the status quo and allows researchers to sidestep reflecting on the concerns raised by autistic people. Taking the time to understand terms autistic people use to describe their perspectives and experiences should be standard procedure for any researchers focusing on autism.

Suggestions for Researchers

In this section, we provide practical guidance to help researchers make language choices that reduce stigmatization, misunderstanding, and exclusion of autistic people. While our suggestions are primarily targeted to researchers, health care providers and other direct support professionals may also find them useful. We have divided our guidance into three sections. First, we briefly discuss participatory models of autism research, and the ways that they may improve discourse around autism. Second, we provide a set of questions that researchers can ask themselves about their language choices that may help them identify problematic wording. Third, we have compiled a noncomprehensive list of potentially ableist terms and discourses that regularly recur in autism research (including some of our own prior work) and provide suggested alternatives.

Participatory models of autism research

For many nonautistic autism researchers, language choices may be dictated by historical conventions and a desire to be consistent with language in the academic journals in which they publish. These conventions persist, despite autistic preferences, in part because of a failure to integrate representative numbers of autistic people and stakeholders into executive research positions. To counter this, participatory models of autism research have been developed. A hallmark of these approaches is that autistic people are included in the research process conducted by nonautistic investigators, and editorial decisions made by nonautistic publishers elevate autistic voices into roles with greater power. (See Refs.13,18,59,92,93 for descriptions and guidance on this approach). This can help break down conventional barriers and lead to research that better matches the preferences and priorities of the autistic community. We advocate for a shift in funding priorities (which traditionally favor causation and cure research94–96), so that grant money is available to compensate autistic people for their participation. For autistic nonresearchers who are interested, these funds could be used to provide training on basic research methodology that would further enable substantive contributions to research design and analysis procedures. Nonautistic researchers should also be trained on how to partner with autistic people (including those without academic backgrounds) through all phases of the research process. Procedures for remote participation (e.g., video conference or instant messaging) have been developed that will enable researchers to cast a wide net in soliciting autistic partners and communicate about research activities using accessible modalities.92,97

Additionally, hiring and promoting autistic researchers into faculty positions can ensure that autistic people play leading roles in autism research. Autistic autism researchers have already made significant contributions to our understanding of autism and have provided much of the language guidance we draw on in this article. In tandem with meaningfully involving autistic people (researchers and nonresearchers alike) in the research process, participatory research should be conducted that is rigorous and high quality.10

Researcher questions for self-reflection on language choices

Below are seven questions that may help researchers determine if they have adequately considered the impacts of their language choices on autistic communities. If the answer to question one is “no” or the answers to questions two through seven are “yes,” researchers should consider alternative ways of speaking or writing (which we provide in Table 1, explained below).

-

1.

Would I use this language if I were in a conversation with an autistic person?

-

2.

Does my language suggest that autistic people are inherently inferior to nonautistic people, or assert that they lack something fundamental to being human?

-

3.

Does my language suggest that autism is something to be fixed, cured, controlled, or avoided?

-

4.

Does my language unnecessarily medicalize autism when describing educational supports?

-

5.

Does my language suggest to lay people that the goal of my research is behavioral control and normalization, rather than granting as much autonomy and agency to autistic people as reasonably possible?

-

6.

Am I using particular words or phrases solely because it is a tradition in my field, even though autistic people have expressed that such language can be stigmatizing?

-

7.

Does my language unnecessarily “other” autistic people, by suggesting that characteristics of autism bear no relationships to characteristics of nonautistic people?

Alternatives to commonly used terms that are potentially ableist

Finally, Table 1 provides concrete examples of how researchers might replace potentially ableist terms/discourses with suggested nonableist alternatives. In generating this table, we relied on the work of autistic scholars, researchers, and advocates, as well as on research by nonautistic scholars that centers autistic perspectives. We provide references to this work so that researchers can understand the rationale behind these language suggestions and determine if it applies to their work. We acknowledge that what can be considered “ableist language” depends on the time, place, and manner in which it is used.98 Therefore, not all instances of using the terms/discourses described in the table are necessarily ableist. Likewise, not all nonableist language suggestions we offer will be appropriate or preferred for all of autistic people; in those cases, other terms may be necessary. While the autistic writers whose language suggestions appear in this table may not be representative of the entire autistic community, their suggestions may nonetheless have broad applicability. It is also likely that this table will need revising as language usage will inevitably evolve. Still, while our partial compilation will not serve as hard-and-fast rules, it offers researchers an opportunity to interrogate their language choices.

Conclusion

In this commentary, we have defined and described ableism, traced the historical trajectory of ableist language in autism research, and provided arguments for why researcher attempts to avoid ableist language will result in better outcomes for the autistic community as well as improved communication in research. Language choices are important, as they shape attitudes about autism and people's understanding of what it means to be an autistic person. Now more than ever, researchers are taking autistic perspectives into account in their writing, and we applaud these changes. While the views presented in this Perspective are by definition partial, we hope this commentary contributes to ongoing discussions about language use and offers avenues for researchers to adapt their language practices. Moving forward, journals that publish autism-related research should encourage researchers to interrogate and explain their language choices to ensure that they have considered autistic perspectives and the implications of their choices for autistic people.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Sue Fletcher-Watson for her commentary on an earlier version of this article.

Authorship Confirmation Statement

K.B.-B. proposed the initial outline of the article and oversaw editing of the final document. K.B.-B., S.K.K., J.N.L., N.J.S., and B.N.H. conceptualized the article, gathered literature for the review, wrote sections of the article, and contributed to editing the final document. All authors have reviewed and approved the article before submission. This article has been submitted solely to this journal and is not published, in press, or submitted elsewhere.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

The authors did not receive any funding in support of this article.

References

- 1. Smith L. #Ableism. Center for Disability Rights. n.d. http://cdrnys.org/blog/uncategorized/ableism (accessed April 26, 2020).

- 2. Botha M, Frost DM. Extending the minority stress model to understand mental health problems experienced by the autistic population. Soci Mental Health. 2020;10(1):20–34. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bottema-Beutel K, Cuda J, Kim SY, Crowley S, Scanlon D. High school experiences and support recommendations of autistic youth. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cage E, Di Monaco J, Newell V. Experiences of autism acceptance and mental health in autistic adults. J Autism Dev Disord 2018;48(2):473–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johnson TD, Joshi A. Dark clouds or silver linings? A stigma threat perspective on the implications of an autism diagnosis for workplace well-being. J Appl Psychol. 2016;101(3):430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sarrett J. Interviews, disclosures, and misperceptions: Autistic adults' perspectives on employment related challenges. Disabil Stud Q. 2017;37(2). https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/5524/4652 (accessed August 28, 2020).

- 7. Ballou EP [chavisory]. A checklist for identifying sources of aggression. We Are Like Your Child. http://wearelikeyourchild.blogspot.com/2014/05/a-checklist-for-identifying-sources-of.htm (accessed April 26, 2020).

- 8. Brown L. The significance of semantics: Person first language: Why it matters. https://www.autistichoya.com/2011/08/significance-of-semantics-person-first.html (accessed April 26, 2020).

- 9. Garnder F. The problem with functioning labels. http://www.thinkingautismguide.com/2018/03/the-problems-with-functioning-labels.html (accessed April 26, 2020).

- 10. Dawson M. What history tells us about autism research, redux. http://autismcrisis.blogspot.com/2017/11/what-history-tells-us-about-autism.html (accessed April 26, 2020).

- 11. Kapp SK. Empathizing with sensory and movement differences: Moving toward sensitive understanding of autism. Front Integr Neurosci. 2013;7:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kapp SK. Interactions between theoretical models and practical stakeholders: The basis for an integrative, collaborative approach to disabilities. In: Ashkenazy E, Latimer M, eds. Empowering Leadership: A Systems Change Guide for Autistic College Students and Those with Other Disabilities. The Autistic Press; 2013;104–113. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Milton D. On the ontological status of autism: The ‘double empathy problem’. Disabil Soc. 2012;27(6):883–887. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yergeau M. Clinically significant disturbance: On theorists who theorize theory of mind. Disabil Stud Q. 2013;33(4). https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/3876/3405 (accessed August 28, 2020).

- 15. Yergeau M. Authoring Autism: On Rhetoric and Neurological Queerness. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gillespie-Lynch K, Kapp SK, Brooks PJ, Pickens J, Schwartzman B. Whose expertise is it? Evidence for autistic adults as critical autism experts. Front Psychol. 2017;8:438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kenny L, Hattersley C, Molins B, Buckley C, Povey C, Pellicano E. Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism. 2016;20(4):442–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, Kapp SK, et al. The AASPIRE practice-based guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults in research as co-researchers and study participants. Autism. 2019;23(8):2007–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pellicano E, Dinsmore A, Charman T. What should autism research focus upon? Community views and priorities from the United Kingdom. Autism. 2014;18(7):756–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fletcher-Watson S, Happé F. Autism: A New Introduction to Psychological Theory and Current Debate. London, UK: Routledge; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Byrne P. Stigma of mental illness and ways of diminishing it. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2000;6(1):65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gernsbacher M. Stigma from psychological science: Group differences, not deficits-Introduction to stigma special section. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2010;5(6):687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McGuire A. Life without autism: A cultural logic of violence. In Runswich-Cole K, Mallet R, Timmi S, eds. Re-thinking Autism: Diagnosis, Identity and Equality. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2016;93–109. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Murray S. Representing Autism: Culture, Narrative, Fascination. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Billawala A, Wolbring G. Analyzing the discourse surrounding Autism in the New York Times using an ableism lens. Disabil Stud Q. 2014;34(1). https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/3348 (accessed August 28, 2020).

- 26. Gillborn D. Intersectionality, critical race theory, and the primacy of racism: Race, class, gender, and disability in education. Qual Inq. 2015;21(3):277–287. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lewis L. Longmore lecture: Context, clarity and grounding. https://www.talilalewis.com/blog (accessed April 26, 2020).

- 28. Blanchett WJ, Klingner JK, Harry B. The intersection of race, culture, language, and disability: Implications for urban education. Urban Educ. 2009;44(4):389–409. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gernsbacher MA, Dawson M, Mottron L. Autism: Common, heritable, but not harmful. Behav Brain Sci. 2006;29(4):413–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gernsbacher MA. On not being human. APS Observer. 2007;20(2):5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jaswal VK, Akhtar N. Being versus appearing socially uninterested: Challenging assumptions about social motivation in autism. Behav Brain Sci. 2019;42:e82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kapp SK. How social deficit models exacerbate the medical model: Autism as case in point. Autism Policy Pract. 2019;2(1):3–28. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Woods R. Exploring how the social model of disability can be re-invigorated for autism: In response to Jonathan Levitt. Disabil Soc. 2017;32(7):1090–1095. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mundy P. Lessons learned from autism: An information processing model of joint attention and social cognition. In: Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology: Meeting the Challenge of Translational Research in Child Psychology, vol. 35. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons; 2009;59–113. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bottema-Beutel K, Park H, Kim SY. Commentary on social skills training curricula for individuals with ASD: Social interaction, authenticity, and stigma. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(3):953–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Crane L, Adams F, Harper G, Welch J, Pellicano E. ‘Something needs to change’: Mental health experiences of young autistic adults in England. Autism. 2019;23(2):477–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim SY, Bottema-Beutel K. Negotiation of individual and collective identities in the online discourse of autistic adults. Autism Adulthood. 2019;1(1):69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cherney JL. The rhetoric of ableism. Disabil Stud Q. 2011;31(3). [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wolbring G. The politics of ableism. Development. 2008;51(2):252–258. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sacks H. Lectures on Conversation. Oxford: Blackwell; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Potter J. Discourse analysis and discursive psychology. In: Cooper H, ed. APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological, vol. 2. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012;111–130. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Potter J, Wetherell M. Discourse and Social Psychology. London: Sage; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fairclough N. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wittgenstein L. Philosophical Investigations, 2nd ed. (G. E. M. Anscombe, Trans.). Oxford: Blackwell; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kuntz AM. Representing representation. Int J Qual Stud Educ. 2010;23(4):423–433. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Noblit GW, Flores SY, Murillo EG, eds. Postcritical Ethnography: Reinscribing Critique. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rallis SF. ‘That is NOT what's happening at Horizon!’: Ethics and misrepresenting knowledge in text. Int J Qual Stud Educ. 2010;23(4):435–448. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Edwards D. Discourse and Cognition. London: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nadesan MH. Constructing autism: A brief genealogy. In: Osteen M, eds. Autism and Representation. New York: Routledge; 2008;78–95. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Alexander FG, Selesnick ST. The History of Psychiatry: An Evaluation of Psychiatric Thought and Practice from Prehistoric Times to the Present. New York: Harper & Row; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Broderick AA, Ne'eman A. Autism as metaphor: Narrative and counter narrative. Int J Inclusive Educ. 2008;12(5–6):459–476. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ashby CE. The trouble with normal: The struggle for meaningful access for middle school students with developmental disability lab. Disabil Soc. 2010;23(3):345–358. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Canguilhem G. The Normal and the Pathological. Brooklyn, NY: Zone Books; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brickman P, Rabinowitz VC, Karuza J, Coates D, Cohn E, Kidder L. Models of helping and coping. Am Psychol. 1982;37(4):368–384. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child. 1943;2(3):217–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Asperger H. Die “Autistischen Psychopathen” im Kindesalter. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci. 1944;117(1):76–136. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Duffy J, Dorner R. The pathos of “mindblindness”: Autism, science, and sadness in “Theory of Mind” narratives. J Literary Cult Disabil Stud. 2011;5(2):201–215. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Oliver M. Defining impairment and disability: Issues at stake. In: Barnes C, Mercer G, eds. Exploring the Divide. Leeds, UK: The Disability Press; 1996;29–54. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chown N, Robinson J, Beardon L, et al. Improving research about us, with us: A draft framework for inclusive autism research. Disabil Soc. 2017;32(5):720–734. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Oliver M. The social model of disability: Thirty years on. Disabil Soc. 2017;28(7):1024–1026. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kapp SK, ed. Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline. Singapore: Palgrave MacMillan; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bailin A. Misconceptions about neurodiversity. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/clearing-up-some-misconceptions-about-neurodiversity (accessed June 6, 2019).

- 63. Ballou EP. What the neurodiversity movement does- and doesn't offer. http://www.thinkingautismguide.com/2018/02/what-neurodiversity-movement-doesand.html (accessed February 6, 2018).

- 64. Swain J, French S. Towards an affirmation model of disability. Disabil Soc. 2000;15(4):569–582. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kapp SK, Gillespie-Lynch K, Sherman LE, Hutman T. Deficit, difference, or both? Autism and neurodiversity. Dev Psychol. 2013;49(1):59–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Waltz Mitzi. Autism: A Social and Medical History. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sinclair J. Why I dislike person first language. Autonomy 2013;1(2). http://www.larry-arnold.net/Autonomy/index.php/autonomy/article/view/OP1/html_1 (accessed August 28, 2020).

- 68. Wehmeyer M, Bersani H, Gagne R. Riding the third wave: Self-determination and self-advocacy in the 21st century. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabil. 2000;15(2):106–115. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Nadesan MH. Constructing autism: A brief genealogy. In: Osteen M, ed. Autism and Representation. New York: Routledge; 2008;78–95. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Mutua K, Smith RM. Disrupting normalcy and the practical concerns of classroom teachers. In: Danforth S, Gabel SL, eds. Vital Questions Facing Disability Studies in Education. New York, NY: Peter Lang; 2006;121–132. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Shakes P, Cashin A. Identifying language for people on the autism spectrum: A scoping review. Issues Mental Health Nurs. 2019;40(4):317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Bury SM, Jellett R, Spoor JR, Hedley D. “It defines who I am” or “It's something I have”: What language do [autistic] Australian adults [on the autism spectrum] prefer? J Autism Dev Disord. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1007/s10803-020-04425-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Fletcher-Watson S, Apicella F, Auyeung B, et al. Attitudes of the autism community to early autism research. Autism. 2017;21(1):61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Furfaro H. Tensions ride high despite reshuffle at autism science meeting. https://www.spectrumnews.org/news/tensions-ride-high-despite-reshuffle-autism-science-meeting (accessed April 29, 2019).

- 75. Savarese ET. What we have to tell you: A roundtable with self-advocates from AutCom. Disabil Stud Q. 2009;30(1). https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/1073/1239 (accessed August 28, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sequenzia A, Grace EJ, eds. Typed Words, Loud Voices. Fort Worth, TX: Autonomous Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Cevik K. #AutisticWhileBlack: Diezel Braxton and becoming indistinguishable from one's peers. http://theautismwars.blogspot.com/2018/07/autisticwhileblack-diezel-braxton-and_24.html (accessed July 24, 2018).

- 78. Greenburg C, Des Roches Rosa S. Two winding parent paths to neurodiversity advocacy. In: Kapp SK, ed. Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline. Singapore: Palgrave MacMillan; 2020;155–166. [Google Scholar]

- 79. American Psychological Association. Publication Manual, 6th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 80. National Center on Disability and Journalism. Disability Language Style Guide. http://ncdj.org/style-guide 2018 (accessed August 28, 2020).

- 81. Jones CR, Happé F, Golden H, et al. Reading and arithmetic in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: Peaks and dips in attainment. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(6):718–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Shattuck PT, Wagner M, Narendorf S, Sterzing P, Hensley M. Post-high school service use among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(2):141–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Taylor JL, Seltzer MM. Employment and post-secondary educational activities for young adults with autism spectrum disorders during the transition to adulthood. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(5):566–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Alvares GA, Bebbington K, Cleary D, et al. The misnomer of ‘high functioning autism’: Intelligence is an imprecise predictor of functional abilities at diagnosis. Autism. 2020;24:221–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kapp S, Ne'eman A. ASD in DSM-5: What the research shows and recommendations for change. 2012. https://autisticadvocacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/ASAN_DSM-5_2_final.pdf (accessed August 28, 2020).

- 86. Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R, Martin J, Clubley E. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31(1):5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. English MCW, Gignac GE, Visser TAW, Whitehouse AJO, Maybery MA. A comprehensive psychometric analysis of autism-spectrum quotient factor models using two large samples: Model recommendations and the influence of divergent traits on total-scale scores. Autism Res. 2020;13:45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Baron-Cohen S. The Concept of Neurodiversity Is Dividing the Autism Community. Scientific American Blog Network. 2019. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/the-concept-of-neurodiversity-is-dividing-the-autism-community Last accessed April 30, 2020.

- 90. Jaarsma P, Welin S. Autism as a natural human variation: Reflections on the claims of the neurodiversity movement. Health Care Anal. 2012;20(1):20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. den Houting J. Neurodiversity: An insider's perspective. Autism. 2019;23(2):271–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Nicolaidis C. What can physicians learn from the neurodiversity movement?. AMA J Ethics. 2012;14(6):503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Fletcher-Watson S, Adams J, Brook K, et al. Making the future together: Shaping autism research through meaningful participation. Autism. 2019;23(4):943–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Pellicano E, Dinsmore A, Charman T. What should autism research focus upon? Community views and priorities from the United Kingdom. Autism. 2014;18(7):756–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Singh J, Illes J, Lazzeroni L, Hallmayer J. Trends in US autism research funding. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(5):788–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Den Houting J, Pellicano E. A portfolio analysis of autism research funding in Australia, 2008–2017. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(11):4400–4408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Gillespie-Lynch K, Kapp S, Shane-Simpson C, Smith D, Hutman T. Intersections between the autism spectrum and the internet: Perceived benefits and preferred functions of computer-mediated communication. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2014;52(6):456–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Brown L. Ableism/Language. Autistichoya.com. 2018. https://www.autistichoya.com/p/ableist-words-and-terms-to-avoid.html (accessed April 30, 2020).

- 99. Cynthia K. What's so special about a special interest?. Musings of an Aspie. 2012. https://musingsofanaspie.com/2012/11/07/whats-so-special-about-a-special-interest (accessed April 30, 2020).

- 100. Gernsbacher M, Raimond A, Balinghasay M, Boston J. “Special needs” is an ineffective euphemism. Cogn Res Princ Implic. 2016;1(1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Kailes J. Language Is More Than A Trivial Concern! 10Th Edition. Center for Disability and Health Policy. 2010. https://www.resourcesforintegratedcare.com/sites/default/files/Language%20Is%20More%20Than%20A%20Trivial%20Concern.pdf (accessed April 30, 2020).

- 102. Kapp S, Steward R, Crane L, et al. ‘People should be allowed to do what they like’: Autistic adults' views and experiences of stimming. Autism. 2019;23(7):1782–1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Schaber A. Ask an autistic #15 - what are autistic meltdowns?. YouTube. 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FhUDyarzqXE&t=1s (accessed April 30, 2020).

- 104. Boue S. The sound of stigma: A journey across the rope bridge. #autismacceptance. The Other Side. 2017. https://soniaboue.wordpress.com/?s=rope+bridge (accessed April 30, 2020).

- 105. Gernsbacher M. Editorial Perspective: The use of person-first language in scholarly writing may accentuate stigma. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2017;58(7):859–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Lynch C. Person-first language: What it is, and when not to use it. Neuroclastic. 2019. https://theaspergian.com/2019/04/19/person-first (accessed April 30, 2020).

- 107. Robison J. Talking about autism—thoughts for researchers. Autism Res. 2019;12(7):1004–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Jones S. Disability day of mourning: We are not burdens—Rooted in rights. Rooted in Rights. 2017. https://rootedinrights.org/disability-day-of-mourning-we-are-not-burdens (accessed April 30, 2020).

- 109. Kaplan B, Dewey D, Crawford S, Wilson B. The term comorbidity is of questionable value in reference to developmental disorders. J Learn Disabil. 2001;34(6):555–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Griffin E, Pollak D. Student experiences of neurodiversity in higher education: Insights from the BRAINHE project. Dyslexia. 2009;15(1):23–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Henderson H, Ono K, McMahon C, Schwartz C, Usher L, Mundy P. The costs and benefits of self-monitoring for higher functioning children and adolescents with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(2):548–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Walker N. Neurodiversity: Some basic terms and definitions. Neurocosmopoloitanism. 2014. http://neurocosmopolitanism.com/neurodiversity-some-basic-terms-definitions (accessed April 30, 2020).

- 113. Pitney J. “Lifetime Social Cost.” Autism Politics and Policy. 2020. http://www.autismpolicyblog.com/2020/02/lifetime-social-cost.html (accessed April 30, 2020).

- 114. Oolong. Autism when it's not a disability. 2019. https://medium.com/@Oolong/autism-when-its-not-a-disability-a3dcafa732a (accessed April 30, 2020).

- 115. Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN). ASAN Statement on Fein Study on Autism and “Recovery.” ASAN. 2013. https://autisticadvocacy.org/2013/01/asan-statement-on-fein-study-on-autism-and-recovery (accessed April 30, 2020).

- 116. Kapp S. A critical response to “The kids who beat autism.” Thinking Person's Guide to Autism. 2014. http://www.thinkingautismguide.com/2014/08/a-critical-response-to-kids-who-beat.html (accessed April 30, 2020).

- 117. Hull L, Petrides K, Allison C, et al. “Putting on My Best Normal”: Social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(8):2519–2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Rose K. Masking: I am not okay. The Autistic Advocate. 2018. https://theautisticadvocate.com/2018/07/masking-i-am-not-ok.html (accessed April 30, 2020).

- 119. Gernsbacher M, Raimond A, Stevenson J, Boston J, Harp B. Do puzzle pieces and autism puzzle piece logos evoke negative associations?. Autism. 2018;22(2):118–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Pellicano L, Mandy W, Bölte S, Stahmer A, Lounds Taylor J, Mandell D. A new era for autism research, and for our journal. Autism. 2018;22(2):82–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Gernsbacher M, Dawson M, Hill Goldsmith H. Three reasons not to believe in an autism epidemic. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2005;14(2):55–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]