Abstract

The number of autistic students in colleges is growing rapidly. However, their needs are not being met, and graduation rates among this population remain low. This article describes the implementation and evaluation of the Autism Mentorship Initiative (AMI) for autistic undergraduates (mentees), who received 1-on-1 support from upper-level undergraduate or graduate students (mentors) at their university. We examined changes in college adjustment (n = 16) and grade point average among mentees (n = 19) before and after participation in AMI for two or more semesters. We also examined surveys completed by both mentees (n = 16) and mentors (n = 21) evaluating their experiences in AMI. Data from the Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire showed that mentees displayed lower than average social, emotional, and academic adjustment to college compared with neurotypical norms, but participation in AMI resulted in notable gains in all facets of college adjustment. Survey data revealed that both mentors and mentees reported personal, academic, and professional benefits from participating in AMI. However, no improvements in academic achievement of the mentees were found. This study provided preliminary evidence for the benefits of an easily implemented and cost-effective peer mentorship program for autistic students in a college setting.

Lay summary

Why was this program developed?

There are a growing number of autistic students attending college. However, the percentage of autistic students who complete their degree is quite low. We believe that colleges should be offering more support services to address the unique needs of their autistic students.

What does the program do?

The Autism Mentorship Initiative (AMI) matches incoming autistic undergraduates with upper-level (third or fourth year) neurotypical undergraduates or graduate students who provide 1-on-1 mentorship. The autistic undergraduates meet regularly with their mentors to discuss personal and professional goals, discuss solutions for problems they are experiencing in college, and discuss ideas for increased integration into college campus life (e.g., joining clubs or attending social events). The neurotypical mentors receive ongoing training from program supervisors about autism and meet regularly with program supervisors to discuss progress with their mentees and troubleshoot issues they may be experiencing with their mentees.

How did the researchers evaluate the program?

We evaluated AMI by administering the Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire at multiple time points to examine whether autistic mentees reported improvements in social, emotional, and academic adjustment to college as a result of participating in AMI. In addition to tracking changes in cumulative grade point average (GPA), we also administered program evaluation surveys to determine whether AMI is meeting its core aims and to assess satisfaction with the program from the perspectives of both mentors and mentees.

What are the early findings?

While there were no changes in GPA, participation in AMI resulted in notable changes in mentees' academic, social, and emotional adjustment. Both mentors and mentees reported personal, academic, and professional benefits from their participation in AMI.

What were the weaknesses of this project?

The sample size was small, so it is questionable whether the findings generalize to a broader autistic student population. In addition, there was no control group, so we cannot be certain that improvements in college adjustment were due to participation in AMI. Moreover, this study only assessed one program at one university in Western Canada, so it is unknown whether this program could be successfully implemented at other universities or in different geographic locations.

What are the next steps?

As participation in AMI increases each year, follow-up studies will utilize larger sample sizes. We will seek to obtain control data by examining GPA and college adjustment in autistic students who do not participate in AMI. We will aim to conduct multisite trials to examine whether similar programs can be implemented at other universities.

How will this work help autistic adults now and in the future?

We hope that our research will help faculty members and staff from disability support offices to gain ideas and insights in implementing similar—or better—programs at their respective institutions. Our experience is that mentorship programs can be both cost-effective and easily implemented, while offering an invaluable support system to autistic students that may increase the likelihood of degree completion.

Keywords: college adjustment, autism, ASD, postsecondary, peer mentorship, program evaluation

Introduction

The number of autistic students in postsecondary institutions is rising,1 making it necessary for universities to provide adequate support systems to enhance students' potential for academic success and degree completion. Among the 11 most prevalent disability categories, postsecondary attendance and graduation rates of autistic students are among the lowest.2,3 Upon entering college, many autistic students may not have access to all the support systems they were accustomed to in high school, such as special education programs and classroom accommodations.4 Consequently, there is a growing trend among universities to provide services such as informal mentorship programs, tutors, or other support systems, designed to ease the transition from high school to college for autistic students. These services are in addition to the accommodations (i.e., legal entitlements) that public education institutions are required to provide for students with verified disabilities to minimize barriers to accessible education. Despite the need for better support systems for this population, there is little theoretical or empirical guidance available in the literature for interested parties to rely on when designing optimal support services for autistic students.

Accardo and Kuder used survey and interview methods to investigate the preferred support services and accommodations of autistic students in college.5 One of the themes that emerged was a call for individualized approaches to address the wide-ranging needs and challenges of this population. Roberts and Birmingham reached a similar conclusion from interviewing mentors and mentees participating in Simon Fraser University's (SFU) Autism Mentorship Initiative (AMI).6 A key theme identified by the authors was mentor flexibility in focusing on mentees' concerns and allowing mentees autonomy to identify, articulate, and advocate for their own unique challenges. These insights served as the foundation of our theoretical framework for this study, emphasizing the importance of promoting college adjustment by addressing the unique needs and challenges of any given individual.

Theoretical Framework: A Person-Centered Approach to Promote College Adjustment

Entering college for the first time comes with a variety of changes that require incoming students to quickly adjust to unfamiliar locations and people, changes in class structure and sizes, less instructor oversight, alterations to access to accommodations, increased demands on organization and scheduling, and changes in social structures outside the classroom.4 Given inherent difficulties with transitioning from high school to college, compounded by autistic difficulty in adjusting to change,7 we believe that person-centered mentorship programs such as ours should aim to promote college adjustment to ease the transition from high school to college.

College adjustment is a multifaceted construct defined as a student's success in coping with the academic, social, and emotional demands inherent to the college experience.8 College adjustment comprises four distinct components. Academic adjustment concerns factors relevant to motivation, interest in one's studies, and success in meeting academic demands. Social adjustment concerns forming new friendships and relationships, participation in social activities, and integration into campus life. Personal–Emotional Adjustment is relevant to how a student is feeling psychologically and physically, concerning elements such as stress, mood, perceptions of health, and sleep quality. And finally, Institutional Attachment refers to attitudes toward the college experience in general, and to the chosen college. Poor adjustment to college decreases the likelihood of degree completion,8,9 and elevated levels of autistic traits in the general population are associated with poorer adjustment.10 Furthermore, programs designed to ease the transition from high school to college have demonstrated gains in college adjustment in autistic students relative to autistic control groups that did not receive intervention,11,12 highlighting the practical relevance of this construct to the autism population.

A key interest of the present study was to examine whether participation in a person-centered peer mentorship program promotes college adjustment, which may increase the likelihood of degree completion. Rather than implementing AMI around a structured curriculum, AMI allows peer mentors to offer individualized (person-centered) support for their autistic mentees. This theoretical perspective is based on the highly varied strengths and weaknesses of autistic people,13 necessitating support systems that directly address the most pressing concerns of any given individual. Following the guidance of Roberts and Birmingham's6 qualitative analysis, optimal implementation of a person-centered approach entails (1) a natural progression from structured and formal meetings to informal and relaxed meetings as interpersonal comfort between the mentor and mentee increase over time; (2) the mentor's recognition of their role as a “guide, or a friend,” rather than as a “superior,” to maximize comfort and openness between mentor and mentee; (3) frequent and consistent meeting times and places, with regular check-ins via e-mail as needed so that mentees feel supported and problems can be addressed as they arise; (4) collaboration between mentors and mentees to develop personal, social, and educational goals of the mentee, with agreed upon “action plans” for achieving these goals; and (5) mentors helping to “normalize” the experiences of their mentees by sharing their own successes and struggles in coping with the many challenges that are inherent with college and young adulthood, involving changing academic demands, career exploration, relationships, and increased responsibilities and independence.

Emerging Practice: The AMI

AMI is a mentorship program offered through the Centre for Accessible Learning (CAL) at SFU that matches incoming autistic students with upper-level undergraduate and graduate students to help them navigate the many demands of college life. AMI was modeled after similar mentorship programs, such as University of British Columbia's Mentor Program for Students with ASD and York University's Autism Mentorship Program.14,15 Importantly, AMI is mutually beneficial to both the mentors and the mentees—the mentees add a valuable member to their support system, whereas mentors gain mentorship experience often relevant to their career goals. The specific goals of AMI are six-fold:

-

1.

To provide support in a safe, caring, respectful environment;

-

2.

To share knowledge, experiences, and resources to enhance the mentees' engagement in college;

-

3.

To enhance academic success and mentee retention;

-

4.

To provide opportunities for personal growth and independence for mentees and mentors;

-

5.

To promote inclusivity within the college community;

-

6.

To conduct research to inform best practices.

Efforts are made to recruit mentors who have experience working with autistic people. Both mentees and mentors are interviewed, which assists CAL in the matching process to form optimal mentor–mentee pairs based on overlapping personal interests, degree similarity, and gender preferences wherever possible. Before being matched with mentees, all new mentors are required to attend a day-long orientation delivered by program directors including faculty members from Psychology and Education departments, and the director of CAL. This orientation provides mentors with current best practices and information about autism, the specific challenges many autistic students face in postsecondary settings, the format of AMI, and guidance on mentorship (e.g., building the mentoring relationship, appropriate places to meet, preparing agenda items). As part of the orientation, experienced mentors from previous years share advice based on their experiences in the program. Mentors are also given a program manual describing expectations of the mentors, resources available to them and their mentees, information about appropriate codes of conduct, and various worksheets/protocols regarding goal setting and attainment that can be used for record-keeping. The orientation aims to be as participatory as possible—for example, mentors are presented with vignette scenarios depicting challenges their mentees may experience (e.g., conflict with a teaching assistant) for which ideas are brainstormed in small groups, then discussed as a whole group.

After mentor–mentee pairs are formed, CAL helps to coordinate their first meeting. In this initial meeting, the pairs read and sign a mentor–mentee contract, which describes appropriate ways for mentees to contact their mentor, how often and where they plan to meet, and the specific roles and limitations of the mentors. It is emphasized that mentors are not tutors (e.g., for assisting with assignments) or mental health care providers. Rather, they are there to help mentees gain access to services they may need, share advice based on their own experiences, help mentees with planning and organization, to promote involvement in social activities (e.g., recreational sports or clubs), and simply to enjoy time together. Mentees are encouraged to formulate personal, social, academic, and/or professional goals. A portion of mentor–mentee meetings is often dedicated to discussing strategies and creating “action plans” for achieving these goals.

Many mentees express interest in increasing their social networks and developing social and communication skills. In addition to private meetings with their mentors, AMI hosts several social events per year to provide a safe and friendly environment for mentees to meet new people and informally practice social skills. AMI also offers seminars from invited expert speakers. For example, a clinical psychologist with expertise in autism gave a workshop on managing anxiety, and a representative from a government-sponsored employment service gave a workshop describing the assistance their program offers to autistic adults entering the workforce.

Three times per semester, all mentors convene with AMI supervisors in a “supervision meeting” lasting 1.5–2 hours to facilitate program and skill development. At these meetings, mentors and AMI supervisors discuss ongoing issues, share ideas, and check in on how the mentor–mentee relationships are developing. Mentees must have provided signed consent permitting their mentors to share relevant information about them. During these confidential meetings, each mentor gives an update on how often they are meeting with their mentees and discusses any notable challenges their mentee is facing. As a group, everyone provides feedback and suggestions for how to optimally support the mentee. Often, a relevant “pre-reading” (e.g., a research article or chapter describing research on supporting autistic university students) is assigned before the meeting, as a focus for group discussion. In addition to supervision meetings, mentors are invited to schedule private meetings with the AMI program coordinator when they need additional support or feel uncomfortable discussing certain issues in a group setting.

Mentors are expected to write “progress notes” after each meeting with their mentee to keep track of their mentee's goals, the strategies suggested and used to meet those goals, and whether those goals are being attained. Mentors also have access to a library of books about supporting autistic adults and to a private online Canvas module that includes helpful links related to various topics such as mental and physical wellness, studying and time management, and services at SFU.

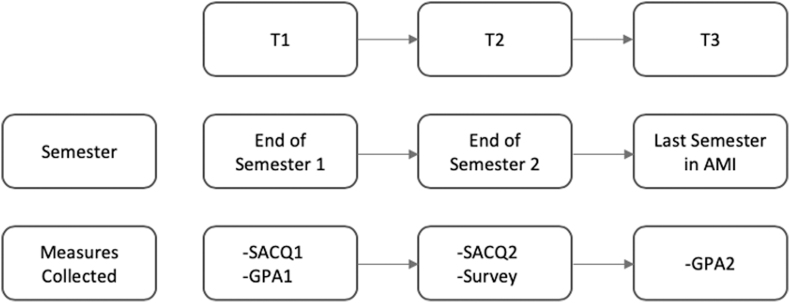

Evaluation Methods

We examined whether AMI met its core aims in promoting social, academic, and emotional adjustment to college. As part of an ongoing longitudinal study that examined data between 2013 and 2018, we examined gains on a standardized questionnaire that measures college adjustment, a program evaluation survey specific to AMI, and grade point average (GPA) from academic transcripts. Thus, although program implementation was delivered at the individual level (to address individual needs), analysis of program benefits was examined at the group level (to examine group-level changes in college adjustment and GPA). College adjustment was first assessed at the end of mentees' first semester in AMI (T1). It was necessary for this measure to be administered at the end of the first semester because measuring college adjustment requires participants to reflect on their college experiences, and if it is measured too early, then there is not sufficient experience to reflect upon.8 The second assessment of college adjustment was administered at the end of mentees' second semester of involvement in AMI (T2). As all mentors and mentees participated in AMI for at least two semesters, this ensured that spacing between T1 and T2 was consistent for all participants (Fig. 1). Program evaluation surveys were completed at T2. Because we had ongoing access to the mentees' academic transcripts, we recorded GPA at T1, and during their last semester in AMI (T3), as the length of involvement in AMI varied by individual. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of our institutional research committee (Research Ethics Board, 2013s0378) and with the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of data collection. AMI, Autism Mentorship Initiative; GPA, grade point average; SACQ, Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire.

Participants

Mentees

Mentees (N = 19) were undergraduates at SFU with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder or Asperger's syndrome (sex: 14 males, 5 females). There were 26 mentees who participated in AMI during 2013–2018. One did not consent to research, and six did not respond to requests to complete questionnaires after consenting to research. While we did not assess level of functioning, all mentees in AMI were accepted into SFU on their own merit, suggesting average to above average cognitive ability. Mentees were required to provide documentation or proof of diagnosis from a qualified clinician to participate in AMI. Mentees typically become involved with AMI through registration with CAL, or referrals from the Health and Counseling Services at SFU, advertisements of the program (emails, flyers, student bulletins), and information on CALs webpage. All participants included in the present study participated in AMI for at least two consecutive semesters between September 2013 and Summer 2018 (range = 2 to 14 semesters, M = 4.05, SD = 3.59), or roughly 1 to 5 years. At the time of first data collection, participant age ranged from 17.5 to 25.75 years (M = 20.34, SD = 2.40). Most mentees entered AMI during their first year in college, although a small subset joined later after realizing they were struggling to adjust. Because most mentees were in their first year, the majority were undeclared.

Mentors

All mentors (N = 21) were undergraduate or graduate students at SFU, in Psychology (n = 7), Education (n = 2), Linguistics (n = 2), Health Sciences (n = 3), other humanities (n = 3), or other science (n = 4) programs (sex: 5 males, 16 females). No other demographic information about the mentors was collected for the purposes of this study.

Standardized Measures and Surveys

College adjustment

College adjustment was measured using the Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire (SACQ),8 a 67-item self-report measure with items rated on a 9-point scale ranging from “applies very closely to me” to “doesn't apply to me at all.” The SACQ encompasses four subscales including academic adjustment (e.g., “I am enjoying my academic work at college”), social adjustment (e.g., “I am very involved with social activities in college”), personal–emotional adjustment (e.g., “I have been getting angry too easily lately”), and institutional attachment (e.g., “I am pleased now about my decision to attend this college in particular”). All facets of the SACQ correlate with each other.8,9 Extensive ecological validity of the SACQ has been established—social adjustment is positively associated with more participation in campus social activities, academic adjustment is positively associated with academic performance, increased personal–emotional adjustment is associated with lower use of mental health services, and increased attachment is associated with a lower likelihood of attrition.8,16 The SACQ has also been validated based on correlations with academic motivation, loneliness, and depression in the expected directions.17 Although there have been criticisms about the validity of the SACQ's internal factor structure,18,19 individuals subscales exhibit strong internal consistency reliabilities (α = 0.80–0.87).10

Program evaluation survey

Mentees and mentors complete a survey evaluating their experiences in the program (see the Supplementary Data to view survey items) at T2. Questions were both quantitative and open-ended in response format, but only quantitative items were analyzed for this study. Because the number of response options (e.g., range of the scales) differed across questions, we grouped responses into three categories: “agreement,” “neutral,” or “disagreement,” for ease in summarizing data (Tables 2–6). The survey requested information about practical details such as how often the pairs met, and what goals were predominantly worked on, but mainly assessed self-reported benefits of the program. The mentors and mentees completed different versions of the survey. The mentors were asked to report personal and professional benefits they experienced from participation in the program. The mentees were asked to report the personal and educational benefits they experienced regarding perceptions of how AMI supported their academics, adjustment to college life, and progress related to their personal goals.

Table 2.

Mentee Satisfaction with Their Mentor and Autism Mentorship Initiative

| Question | % Disagreement | % Neutral | % Agreement | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied with mentor–mentee relationship | 0 | 37.5 | 62.5 | 8 |

| Mentor was supportive | 12.5 | 25 | 62.5 | 8 |

| Mentor and I work well together | 0 | 0 | 100 | 8 |

| Having an upper-level undergraduate mentor from SFU has made my own experiences more relatable | 0 | 0 | 100 | 8 |

| Likelihood of continuing on with AMI | 12.5 | 0 | 87.5 | 16 |

| Satisfied with overall experience in AMI | 0 | 0 | 100 | 8 |

AMI, Autism Mentorship Initiative; SFU, Simon Fraser University.

Table 6.

Topics That Mentor–Mentee Pairs Worked on Together

| Question | % Working on topic | Sample size |

|---|---|---|

| Meeting people and socializing | 52.38 | 21 |

| Communication skills | 52.38 | 21 |

| Managing anxiety | 57.14 | 21 |

| Organization, planning, and time management | 66.67 | 21 |

| Wellness and self-care | 42.86 | 21 |

| Career/job/volunteering/internship exploration | 66.67 | 21 |

Grade point average

Finally, GPA of mentees was compared between their first and last semester in AMI to evaluate whether AMI was effective in boosting academic achievement.

Lessons Learned

Peer mentorship promotes college adjustment in autistic students

Mentees exhibited gains in all facets of college adjustment relevant to academics, social life, emotional well-being, and attachment. The SACQ manual presents normative data for semesters 1 and 2 for incoming first-year students,8 showing that the mean scores of their standardization samples stay roughly the same from the first to second semester depending on the subscale. The percentile scores from our sample presented in Table 1 are based on comparisons with respective semesters 1 and 2 norms reported in the SACQ test manual,8 where a percentile of 50 means average adjustment, and lower percentiles represent poorer adjustment.

Table 1.

T1–T2 Gains in College Adjustment

| |

T1 raw scores and percentiles |

T2 raw scores and percentiles |

Percentile gain | t-Value | p-Value | Sample size | Cohen's d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw mean (range) | Percentile mean | Raw mean (range) | Percentile mean | ||||||

| SACQ subscales | |||||||||

| Academic adjustment | 134 (99–165) | 27 | 141 (97–168 | 42 | 15 | 1.86 | 0.085 | 16 | 0.32 |

| Emotional adjustment | 77 (39–117) | 16 | 85 (34–129) | 31 | 15 | 4.13 | <0.001 | 16 | 0.36 |

| Social adjustment | 103 (68–129) | 18 | 115 (82–160) | 31 | 13 | 3.29 | 0.005 | 16 | 0.59 |

| Institutional attachment | 96 (66–114) | 31 | 103 (86–124) | 54 | 23 | 2.70 | 0.017 | 16 | 0.51 |

| College adjustment (full scale) | 373 (265–444) | 18 | 402 (288–493) | 34 | 16 | 4.25 | <0.001 | 16 | 0.49 |

t-values, p-values, and Cohen's d were calculated using paired samples t-tests with the raw SACQ scores from semesters 1 (T1) and 2 (T2).

SACQ, Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire.

Mentees in AMI displayed mean increases for all subscales ranging from 13 to 23 percentile gains. When comparing raw SACQ scores between semesters 1 and 2 using paired samples t-tests, all gains were statistically significant (ps < 0.05), except for academic adjustment, which showed improvements that approached significance (p = 0.085). Having no control group prevented us from definitively concluding that observed gains in college adjustment were due to participation in AMI. However, as there are no meaningful changes in college adjustment between semesters 1 and 2 in the neurotypical normative data, gains in adjustment in our AMI sample are indirectly suggestive of AMIs benefits. It is important to emphasize that most percentile scores of our participants remained below 50 at semester 2 even after improvements from semester 1, indicating that many mentees were still struggling to adjust to the college environment.

Peer mentorship is beneficial for both mentors and mentees

Tables 2–6 summarize data from the program evaluation surveys. Some questions were open-ended and qualitative in nature. These items were not analyzed in Tables 2–6, but selected quotes of answers from the open-ended questions can be found in the Supplementary Data.

After year 2 of AMI program implementation, the survey was modified. Thus, some of the items in Tables 2–3 were completed by only 8 mentees (those who completed the survey after year 2), whereas survey items that were retained in both versions of the survey were completed by 16 mentees. Similarly, the number of mentors who completed survey items in Tables 4–6 ranged from 10 to 21.

Table 3.

Mentee Educational and Personal Benefits from Autism Mentorship Initiative

| Question | % Disagreement | % Neutral | % Agreement | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMI helped improve my social skills | 6.25 | 43.75 | 50 | 16 |

| AMI was important for adjusting to college | 18.75 | 12.5 | 68.75 | 16 |

| Mentor helped me improve my study skills | 25 | 43.75 | 31.25 | 16 |

| AMI has helped me improve my time management skills | 0 | 12.5 | 87.5 | 8 |

| AMI has helped me manage anxiety | 12.5 | 50 | 37.5 | 8 |

| AMI has provided me opportunities for personal growth and increased independence | 12.5 | 0 | 87.5 | 8 |

| Mentor was helpful in achieving personal goals | 12.5 | 12.5 | 75 | 8 |

| Mentor was helpful in navigating school better | 25 | 25 | 50 | 8 |

Table 4.

Mentor Satisfaction with Autism Mentorship Initiative

| Question | % Disagreement | % Neutral | % Agreement | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied with training on autism and mentorship | 19.05 | 4.76 | 76.19 | 21 |

| Satisfied with canvas materials | 28.57 | 14.29 | 57.14 | 21 |

| Satisfied with AMI library | 19.05 | 19.05 | 61.90 | 21 |

| Satisfied with supervision meetings | 0 | 19.05 | 80.95 | 21 |

| Satisfied with assigned readings | 28.57 | 23.81 | 47.62 | 21 |

| Desire to continue with program | 9.52 | 28.57 | 61.90 | 21 |

Table 5.

Mentor Personal and Professional Benefits

| Question | % Disagreement | % Neutral | % Agreement | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learned more about autism and mentorship | 9.09 | 0 | 90.91 | 11 |

| Benefitted professionally | 20 | 20 | 60 | 10 |

| Benefitted personally and enjoyed involvement in AMI | 9.52 | 0 | 90.48 | 21 |

Mentees generally indicated that they were happy with their decision to join AMI and that it helped them meet their personal and educational goals. For example, 87.5% of mentees expressed likelihood of continuing with AMI for another year, 68.75% agreed that AMI helped them adjust to college, and 87.5% agreed that AMI helped provide personal growth and increased independence. There was less agreement for items related to gains in specific areas—only 50% expressed agreement that AMI helped with socialization and meeting other students, whereas only 37.5% said AMI helped with anxiety management. However, this may reflect that the goal areas mentees chose to work on were highly varied. One hundred percent of the mentees were satisfied with their decision to join AMI, suggesting all respondents experienced some positive benefit relevant to personal or educational goal attainment.

Mentors were also mostly enthusiastic about their experiences, 90.48% agreeing that they benefitted personally and enjoyed their involvement in AMI, and 90.48% agreeing they learned more about autism and mentorship. 80.95% agreed that supervision meetings were beneficial, and 76.19% agreed that they were satisfied with the information about autism provided to them as part of the program. Only 47.62% were satisfied with the assigned readings—anecdotally, many mentors expressed that the assigned readings were a burden on their already busy schedules and that there was a lack of available instructional literature on optimal practices for providing peer mentorship. 61.9% expressed desire to continue being mentors in subsequent years, and most of those who did not were graduating or needed to pursue other experiences for career development.

Peer mentorship does not improve academic performance

Results of a paired samples t-test revealed that there were no significant differences in GPA between T1 (M = 2.96, SD = 1.04) and T3 (M = 2.94, SD = 0.97) GPA collected from transcripts, t(18) = −0.13, p = 0.896. This finding suggests that autistic students who are struggling academically may need additional support systems to foster academic success in college.

Discussion

This article described and evaluated SFUs peer mentorship program for autistic undergraduates. Our findings suggest that compared with neurotypical normative data, autistic undergraduates have a much harder time adjusting to the many demands of college life as measured by the SACQ. However, participating in AMI for two or more semesters resulted in meaningful improvements in social, emotional, and academic adjustment, and attachment to college. These findings are potentially important because college adjustment is associated with higher retention rates,9 suggesting the possibility that peer mentorship programs such as AMI may help reduce attrition rates of autistic college students.3 Observed improvements in college adjustment also speak to the usefulness of AMIs “person-centered” approach, wherein mentorship is individualized based on the unique needs and challenges of each mentee, rather than following a structured curriculum. Although the specific personal, educational, and professional goals that mentor–mentee pairs worked on together were highly varied, gains were observed in all aspects of college adjustment as measured by the SACQ when aggregating group means.

We also administered surveys to both mentees and mentors that assessed participants' perceptions about the effectiveness of AMI and their self-perceived personal, educational, and professional benefits obtained from involvement in this program. Data from both mentors and mentees were generally positive. Although the specific topics that mentors and mentees worked on together varied widely—ranging from socializing, communication skills, managing anxiety, managing course loads, and career exploration—most mentees agreed that they were happy with their decision to join AMI and that it helped them meet the specific goals they were working on. Most mentors felt that having mentorship experience was an important addition to their resumes. They also reported personal benefits, believing that they had made a positive impact on their mentees' lives.

Finally, we examined mentee's official academic transcripts from the time they enrolled in AMI until their last semester in AMI. Results did not show meaningful changes in GPA. These findings are not particularly surprising given that AMI does not specifically target academic achievement, instead focusing on promoting adjustment and smoother transitions from high school to university. Future research is needed to determine effective methods for supporting the academic needs of autistic students—a challenging task given the highly variable cognitive strengths and weaknesses observed in autistic students.

Limitations and Conclusion

This study did not have a comparison group. Future research is needed to conduct multisite studies that compare the effectiveness of mentorship with other interventions for autistic undergraduates. Such research should use preplanned assessment criteria to examine the degree to which various outcomes are achieved as a result of different interventions and to determine the methodological factors related to program implementation that may lead to differing outcomes. This design would offer important advantages as it would encourage collaboration among different universities and increase sample size—another important limitation of the present study. The sample size in this study was smaller than what is ideal for analysis of quantitative surveys. Furthermore, while the SACQ has been used on autistic students in previous research,11,12 it has not been specifically validated for use in this population, which is a necessity for future studies. We also had unequal gender distributions between the mentors and mentees, requiring male mentees to be matched with female mentors on many occasions. Although we did not have sufficient sample size to examine this, future research should explore whether gender matching in mentor–mentee pairs plays any role in the success of the mentor relationship.

Despite these limitations, we hope that this study will offer guidance to faculty members and staff from disability support offices to design and implement similar programs at their institutions, and even improve upon the strategies described in this emerging practice article. Our experience is that mentorship programs can be both cost-effective and easily implemented, while offering an invaluable support system to autistic students that improves their college experience. Longitudinal research is needed to examine whether AMI and other similar programs can improve the likelihood of degree completion of autistic students.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Centre for Accessible Learning (CAL) at Simon Fraser University for the financial support and resources they provided for the Autism Mentorship Initiative (AMI). We also appreciate the time the mentors and mentees devoted to filling out surveys and questionnaires for the purposes of this study. Most importantly, we are grateful for the dedication provided by our volunteer mentors in aiming to make a positive impact on the lives of their autistic peers.

Authorship Confirmation Statement

Authors S.L., G.I., and E.B. designed and implemented the peer mentorship program evaluated in this article. Author D.A.T. worked as the research coordinator for the mentorship program. D.A.T. collected and analyzed the data and wrote the bulk of the article. Authors S.L., G.I., and E.B. provided feedback on drafts of the article. All co-authors have reviewed and approved the article before submission. The article has been submitted solely to this journal and is not published, in press, or submitted elsewhere.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This research was not financially supported by any funding agencies.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. White SW, Ollendick TH, Bray BC. College students on the autism spectrum: Prevalence and associated problems. Autism. 2011;15(6):683–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wei X, Jennifer WY, Shattuck P, McCracken M, Blackorby J. Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) participation among college students with an autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(7):1539–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Newman L, Wagner M, Knokey A-M, et al. The Post-High School Outcomes of Young Adults with Disabilities up to 8 Years after High School: A Report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2). NCSER 2011-3005. Washington DC: National Center for Special Education Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adreon D, Durocher JS. Evaluating the college transition needs of individuals with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Interv Sch Clin. 2007;42(5):271–279. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Accardo AL, Kuder SJ, Woodruff J. Accommodations and support services preferred by college students with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2019;23(3):574–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roberts N, Birmingham E. Mentoring university students with ASD: A mentee-centered approach. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(4):1038–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baker RW, Siryk B. Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire: Manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gerdes H, Mallinckrodt B. Emotional, social, and academic adjustment of college students: A longitudinal study of retention. J Couns Dev. 1994;72(3):281–288. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trevisan DA, Birmingham E. Examining the relationship between autistic traits and college adjustment. Autism. 2016;20(6):719–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. White SW, Richey JA, Gracanin D, et al. Psychosocial and computer-assisted intervention for college students with autism spectrum disorder: Preliminary support for feasibility. Educ Train Autism Dev Disabil. 2016;51(3):307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. White SW, Smith IC, Miyazaki Y, Conner CM, Elias R, Capriola-Hall NN. Improving transition to adulthood for students with autism: A randomized controlled trial of STEPS. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2019. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1080/15374416.2019.1669157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Narzisi A, Muratori F, Calderoni S, Fabbro F, Urgesi C. Neuropsychological profile in high functioning autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(8):1895–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ames ME, McMorris CA, Alli LN, Bebko JM. Overview and evaluation of a mentorship program for university students with ASD. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl. 2016;31(1):27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ncube BL, Shaikh KT, Ames ME, McMorris CA, Bebko JM. Social support in postsecondary students with autism spectrum disorder. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2019;17(3):573–584. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Credé M, Niehorster S. Adjustment to college as measured by the student adaptation to college questionnaire: A quantitative review of its structure and relationships with correlates and consequences. Educ Psychol Rev. 2012;24(1):133–165. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beyers W, Goossens L. Concurrent and predictive validity of the Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire in a sample of European freshman students. Educ Psychol Meas. 2002;62(3):527–538. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Feldt RC, Graham M, Dew D. Measuring adjustment to college: Construct validity of the student adaptation to college questionnaire. Meas Eval Couns Dev. 2011;44(2):92–104. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taylor MA, Pastor DA. A confirmatory factor analysis of the Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire. Educ Psychol Meas. 2007;67(6):1002–1018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.