Abstract

Background:

This study investigated whether neurotypical individuals' judgments that they dislike a person are more common when viewing autistic individuals than when viewing neurotypical individuals.

Methods:

Videos of autistic and neurotypical targets were presented to a group of perceivers (neurotypical adults) who were asked whether or not they liked each target and why.

Results:

It was more common for perceivers to “like” neurotypical than autistic targets. The number of “likes” each target received correlated highly with perceiver ratings of target social favorability. Perceivers cited perceived awkwardness and lack of empathy as being reasons for deciding they disliked targets.

Conclusions:

The findings shed light on how neurotypical people (mis)perceive autistic people. Such perceptions may act as a barrier to social integration for autistic people.

Lay summary

Why was this study done?

Previous research has found that nonautistic people tend to form less positive first impressions of autistic people than they do of other nonautistic people. These studies have tended to present questions such as “How trustworthy is this person?” or “How attractive is this person?” along with ratings scales. However, although it is known that nonautistic people tend to give lower ratings on these scales, we do not know whether this amounts to a dislike for autistic people or just lower levels of liking.

What was the purpose of this study?

This study aimed to find out whether nonautistic people are less likely to say they like (and more likely to say they dislike) autistic people than other nonautistic people.

What did the researchers do?

The researchers presented videos of autistic and nonautistic people to other nonautistic adults. The people watching the videos were not told that some of the people in the videos were autistic. They were asked to decide whether they liked or disliked the person in each video and to say why they had made their decision by choosing from a range of options.

What were the results of the study?

Nonautistic people were more likely to say they disliked the person in the video if they were autistic, even though they did not know the diagnosis. The most common reasons for disliking a person was that they appeared awkward, and that they appeared to lack empathy.

What do these findings add to what was already known?

It was already known that nonautistic people tend to rate autistic people less positively on ratings scales. This study suggests that when making judgments—of either liking or disliking—they will sometimes go so far as to say they dislike autistic people.

What are potential weaknesses in the study?

All of the people in the video clips were male, while those watching the videos were mainly female. Therefore, we do not know whether the same observations would be made for perceptions of autistic females. The number of participants watching the videos was relatively small: a larger sample would give more reliable findings.

How will these findings help autistic adults now or in the future?

The findings add to previous research showing nonautistic people's misperceptions of autistic people could be a barrier to social integration for autistic people. They highlight the need for interventions at the societal level aimed at reducing misunderstanding and promoting tolerance.

Keywords: autism, social favorability, mind reading, social interaction, person perception

Introduction

How autistic people integrate into society depends not just on their proclivity or ability to engage with others but also on the degree to which they are welcomed and accepted by other (mostly neurotypical) members of society. Whether or not neurotypical individuals are accepting of an autistic person will depend on how they perceive the individual: are they someone who is favored and indeed liked by those in society? This is a pertinent question in light of recent evidence that suggests neurotypical individuals perceive autistic individuals less favorably than other neurotypical people, especially when their diagnosis is not known.1–3

Key research has measured the expressed willingness of neurotypical people to interact with autistic individuals after seeing them in brief video clips.2 Participants (targets) were videoed during a short mock audition. Half were autistic and half were neurotypical. Subsequently, another group of neurotypical participants (perceivers) watched the videos and rated the targets on 10 dimensions of social favorability. Even though perceivers were not aware that some targets were autistic, they rated neurotypical targets more favorably, and indicated a stronger willingness to interact with them. The tendency for neurotypical perceivers to rate autistic targets less favorably is robust across perceivers experiencing different kinds of briefing,3 different samples of target behavior,4 different rating scales, and different question wordings.1 These social favorability ratings of autistic people are largely accounted for by stigma-related beliefs on the part of neurotypical observers,5 as opposed to social skills (or other characteristics) of autistic people themselves.6

Although it has been shown that autistic people are evaluated less favorably by neurotypical people, it does not necessarily follow that perceivers dislike autistic targets, as it is possible to feel positive about all targets but rate them slightly more or less positively by a matter of degree. Yet being actually disliked by others could have very different—and more negative—consequences than being viewed positively but less favorably than others. Previous research has suggested that liking and disliking have differential effects on observed behavior,7 hence asking participants to make a fixed choice between liking and disliking could yield different information than using a scaled evaluation of liking alone. In this study, we, therefore, aimed to determine for the first time whether, when asked to make a fixed choice evaluation, neurotypical perceivers are more likely to judge that they dislike autistic targets. We also asked perceivers which social favorability factors they believed contributed to their judgment that they liked/disliked the target.

Methods

Participants (perceivers)

Thirty neurotypical perceivers (five males) took part, aged between 18 and 27 years (M = 19.57, SD = 2.42). They were recruited through the “participant recruitment system” and advertisements at the University of [retracted for review purposes]. Perceivers took part in exchange for course credit.

Materials

The researcher presented 40 videos (taken from a previous study8) of male targets, 20 autistic and 20 neurotypical, aged between 13 and 21 (M = 15.4 years) with the two groups matched for age.

In previous research, we had filmed target participants as they reacted naturally to the researcher's behavior in one of four greeting scenarios (told a joke, kept waiting, paid compliments, or told a story about the researcher's bad day), determined at random, but with equal number of targets in each scenario. Videos were 7.22 seconds long on average, and length did not differ across scenarios or target groups. We have previously described procedures, including details of how the researcher edited the videos.1,8

Procedures

The procedure was approved by the School of Psychology Ethics Committee, University of [retracted for review purposes] (Ethics Approval Number: S964). The researcher presented all 40 target videos to each perceiver using Qualtrics survey software, in random order. Each perceiver (tested individually) viewed each video played on a loop until the perceiver had finished responding. Perceivers rated each target on a likeability question “Do you like/dislike this person?” by clicking one of two options (like or dislike), then rated each target on nine social favorability dimensions on a scale from 1 (low) to 6 (high), which appeared in fixed order.1,2 These were “How much would you like to talk to this person? How awkward is this person? How attractive is this person? How trustworthy is this person? How dominant is this person? How likable is this person? How intelligent is this person? How good is this person's self-esteem? How empathic is this person?” We asked perceivers to indicate on the same screen which of the nine items were most important in deciding whether they liked/disliked the person. Participants could check as many boxes as they felt appropriate and we did not ask them to give any indication of the relative importance of the items they checked.

Data handling

The researcher analyzed the data using SPSS version 26. All perceivers made judgments about all targets and there were no missing values. To determine the degree to which neurotypical individuals like autistic people, we counted likes (out of 30) that each target received from the 30 perceivers. Number of likes was then subjected to a 2 × 4 analysis of variance, with within-participants factors of target group (autistic or neurotypical) and greeting scenario (compliment, joke, story, or waiting). These were followed up by Bonferroni corrected pairwise comparisons and post hoc t-tests (with Bonferroni corrected alpha level of 0.0125, to allow for multiple comparisons). The social favorability index was the average rating across the nine social favorability scales for each target, as rated by the 30 perceivers (previous research has established that the nine scales are underpinned by a single factor.1) We used correlations to examine the relationship between number of likes and social favorability. We also calculated frequency counts for perceivers endorsing each of the social favorability items as justifications for liking/disliking targets.

Results

Figure 1 shows mean number of likes (out of 30) that targets received from perceivers. There was a main effect of target group, F(1,29) = 38.88, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.57, with autistic targets (M = 15.37, SD = 1.35) receiving fewer likes than neurotypical targets (M = 21.68, SD = 0.97). A main effect of scenario was also found, F(3,87) = 110.04, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.79. This was driven by targets in the waiting scenario receiving fewer likes than those in all other scenarios, p < 0.001. There was also a significant interaction between group and scenario, F(3,87) = 27.38, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.49. Autistic targets received fewer likes from perceivers than neurotypical targets in the compliment scenario, t(29) = −5.63, p < 0.001, d = 1.03; joke scenario t(29) = −8.93, p < 0.001, d = 1.63; story scenario t(29) = −5.96, p < 0.001, d = 1.09; but there was no group difference in number of likes received in the waiting scenario, t(29) = 2.48, p = 0.02, d = 0.45.

FIG. 1.

Mean number of “likes” (out of 30) received by autistic and neurotypical targets. Each target participated in four scenarios. The error bars represent one standard error of the mean.

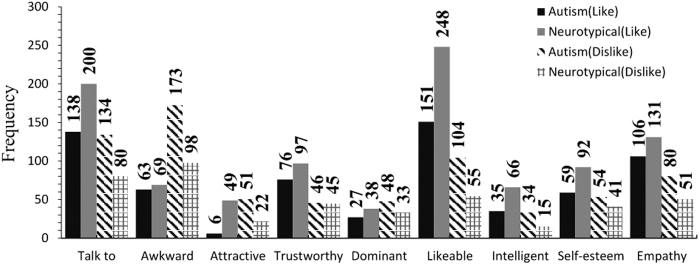

There was a very high correlation between social favorability and number of likes, r = 0.94, p < 0.001. Hence, targets who receive lower graded social favorability ratings also tend to be disliked. Figure 2 shows the frequency count for the social favorability items classified according to target group (autistic or neurotypical) and whether the perceiver judged that they liked or disliked the target. The maximum possible frequency count would be 600 (20 targets × 30 perceivers), although this count could only occur if all perceivers had judged that they either liked or disliked all targets from a particular group. The most common reasons selected by neurotypical perceivers when judging they disliked autistic targets were (1) the perceived awkwardness of the target, (2) a desire not to talk to the target, (3) target appearing unlikeable, and (4) the target's perceived ability (or lack of ability) to empathize. These justifications also appear as the top four when target groups and positive/negative judgments are combined.

FIG. 2.

The frequency count of social favorability items selected by perceivers when justifying their judgment that they liked or disliked autistic and neurotypical targets.

Discussion

Neurotypical people were more liable to judge that they dislike autistic individuals than other neurotypical individuals. This was true across scenarios aside from targets who were kept waiting, for whom both groups had a high tendency to be disliked, perhaps because they made overtly disagreeable reactions in this context. There was also a strong association between being rated less socially favorable and being disliked by neurotypical perceivers. These findings are noteworthy for two reasons. First, they suggest that a single likeability question may be sufficient to measure neurotypical people's first impressions of autistic and nonautistic targets. Second, they show that in some cases, neurotypical adults' judgments of lower social favorability are tantamount to judging that they dislike the person. This is important in that negative consequences (e.g., social exclusion, peer rejection, or bullying) may be particularly likely where an individual is actually disliked.

When perceivers were asked which elements of social favorability they felt had informed their judgment that they liked/disliked the target, many selected likeability, which is arguably merely a tautology. Perceivers also often selected a desire not to talk with the target. However, conceptually this is more likely to be a consequence of disliking the target as opposed to a reason for disliking them. In addition, though, many perceivers also selected “awkwardness” and “(lack of) ability to empathize.”

This raises the question why these particular traits are considered to be so important when making decisions about liking/disliking a person. Indeed, it is rather striking that whether or not a person was awkward was deemed to be more important than whether the person was trustworthy, when arguably liking an untrustworthy person could lead to far more serious negative consequences than someone who is awkward. Future research could further explore why neurotypical individuals find (social) awkwardness aversive, and whether autistic people believe that awkwardness is less important when making likeability judgments. Previous research has found that although autistic people rate other autistic people more negatively than neurotypical individuals on various traits (including as more awkward), they expressed greater interest in making social connections with them.9 This suggests that perceiving someone as awkward might not have the same social consequences for autistic people. Heasman and Milton10 argue that awkwardness may actually be viewed positively by some autistic people (himself included), emphasizing the relativistic nature of these impressions. This is consistent with the double empathy framework of autism,11 which proposes that apparent social disability in autism arises from mutual failures in reciprocity and intersubjectivity between autistic and nonautistic people (who each have differing minds, perceptions, and experiences) as opposed to a “deficit” within autistic people.

The finding that “ability to empathize” was also deemed important to liking judgments appears consistent with the long-held view that autistic people lack empathy.12,13 However, this is a harmful misconception arising from limitations in the methodology and terminology used in previous research.14,15 While the current research does not shed any light on this matter, it does suggest that autistic people are perceived as lacking empathy and that this is associated with their being less liked. Notably, “attractiveness” was rarely cited as a reason for disliking targets, including autistic targets, perhaps suggesting that perceivers do not believe they took physical appearance into consideration when making their judgments, although it is not possible to know whether perceivers interpreted this item as referring to physical attractiveness only.

A key limitation of the study is that all targets were male while the perceivers were mainly female, so it is not clear whether the findings extend to other permutations of targets and perceivers. Moreover, the total sample size for perceivers was relatively small, although not dissimilar from some previous studies on similar topics,1 and a replication with a larger sample would be useful. Also, no autistic perceivers were included. While previous studies have found autistic perceivers do not rate autistic targets more favorably,9,16 they still might be less inclined to judge they actually dislike autistic others. Finally, no social desirability measure was included, making it possible that perceivers may have exaggerated their liking of the targets—although this could not explain the difference in likes received by autistic and nonautistic targets.

The findings contribute to a growing literature supporting the possibility that neurotypical people's (mis)perception of autistic individuals creates a barrier to autistic people being accepted in a society dominated by neurotypical people. In view of this, steps could be taken to enlighten the neurotypical majority about autism with the aim of reducing misperception, thus promoting tolerance and understanding. Indeed, the double empathy account11,17 places responsibility at least partly on the neurotypical majority to adjust to the autistic minority.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted as part of Rabi Samil Alkhaldi's doctoral research, which is funded by a Saudi Government Scholarship from the Saudi Arabian Cultural Bureau (SACB).

Authors' Contributions

R.S.A. conceived the research, designed the experiment, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the article. E.S. conceived the research, designed the experiment, and wrote the article. E.B. conceived the research, designed the experiment, and wrote the article. P.M. conceived the research, designed the experiment, and wrote the article. All coauthors have reviewed and approved the article.

Disclaimer

The article has been solely submitted to Autism in Adulthood and is not published, in press, or submitted elsewhere.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

These studies form part of the doctoral research of Rabi Samil Alkhaldi, funded by a Saudi Government Scholarship from the Saudi Arabian Cultural Bureau (SACB).

References

- 1. Alkhaldi RS, Sheppard E, Mitchell P. Is there a link between autistic people being perceived unfavorably and having a mind that is difficult to read? J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(10):3973–3982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sasson NJ, Faso DJ, Nugent J, Lovell S, Kennedy DP, Grossman RB. Neurotypical peers are less willing to interact with those with autism based on thin slice judgments. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sasson N, Morrison KE. First impressions of adults with autism improve with diagnostic disclosure and increased autism knowledge of peers. Autism. 2019;23(1):50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morrison KE, DeBrabander KM, Jones DR, Faso DJ, Ackerman RA, Sasson NJ. Outcomes of real-world social interaction for autistic adults paired with autistic compared to typically developing partners. Autism. 2020;24(5):1067–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morrison KE, DeBrabander KM, Faso DJ, Sasson NJ. Variability in first impressions of autistic adults made by neurotypical raters is driven more by characteristics of the rater than by characteristics of autistic adults. Autism. 2019;23(7):1817–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morrison KE, DeBrabander KM, Jones DR, Ackerman RA, Sasson NJ. Social cognition, social skill, and social motivation minimally predict social interaction outcomes for autistic and non-autistic adults. Front Psychol. 2020;11:3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jordan N. The “asymmetry” of “liking” and “disliking”: A phenomenon meriting further reflection and research. Public Opin Quart. 1965;29(2):315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sheppard E, Pillai D, Wong GTL, Ropar D, Mitchell P. How easy is it to read the minds of people with autism spectrum disorder? J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(4):1247–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. DeBrabander KM, Morrison KE, Jones DR, Faso DJ, Chmielewski M, Sasson NJ. Do first impressions of autistic adults differ between autistic and nonautistic observers? Autism Adulthood. 2019;1(4):250–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heasman B, Milton DE. Double Empathy Podcast Ep 2. Part 1. [podcast] London, Youtube; October 11, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eU9qIL2DlVg&feature=emb_logo (last accessed January 6, 2021).

- 11. Milton DE. On the ontological status of autism: The “double empathy problem.” Disab Soc. 2012;27(6):883–887. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S. The empathy quotient: An investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. J Autism Dev Disord. 2004;34(2):163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jones AP, Happé FG, Gilbert F, Burnett S, Viding E. Feeling, caring, knowing: Different types of empathy deficit in boys with psychopathic tendencies and autism spectrum disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(11):1188–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fletcher-Watson S, Bird G. Autism and empathy: What are the real links? Autism. 2020;24(1):3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nicolaidis C, Milton D, Sasson NJ, Sheppard E, Yergeau M. An expert discussion on autism and empathy. Autism Adulthood. 2018;1(1):4–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grossman RB, Mertens J, Zane E. Perceptions of self and other: Social judgments and gaze patterns to videos of adolescents with and without autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2019;23(4):846–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mitchell P, Sheppard E, Cassidy S. Autism and the double empathy problem: Implications for development and mental health. Br J Dev Psychol. 2021;39(1):1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]