Abstract

Background:

Autistic individuals face low rates of engagement in the labor force. There is evidence that job interviews pose a significant barrier to autistic people entering the workforce. In this experimental study, we investigated the impact of diagnostic disclosure on decisions concerning candidate suitability during job interviews.

Methods:

Participants (n = 357; 59% female) from the general population rated 10 second “thin slices” of simulated job interviews of one male autistic and one male non-autistic candidate. In a between-subjects design, autism diagnostic disclosure was manipulated (None, Brief, and Detailed), so that neither (“None” condition) or both (“Brief” and “Detailed” conditions) candidates were labeled as autistic before the simulated interview (with additional information provided about autism in the “Detailed” condition).

Results:

Results for 255 non-autistic raters (57.6% female) were analyzed. Participants gave more favorable ratings of first impressions, employability, and endorsement for candidates labeled as autistic, irrespective of the actual diagnostic status (i.e., autistic and non-autistic) of the individual. Participants rated non-autistic candidates more favorably on all employment measures (first impressions, employability, and endorsement), and “hired” non-autistic candidates more frequently, compared with autistic candidates. Providing additional information about autism did not result in improved ratings. However, the discrepancy between autistic and non-autistic people chosen for “hire” was reduced when more information was provided.

Conclusions:

Although we found some support for the benefits of diagnostic disclosure during a simulated interview, these benefits were not restricted to autistic candidates and may be a positive bias associated with the diagnostic label. Contrary to our predictions, providing information about autism in addition to the diagnostic label did not have an overall impact on results. More research is required to determine whether benefits outweigh any risks of disclosure for autistic job candidates, and whether training interviewers about autism might improve employment outcomes for autistic job seekers.

Lay summary

Why was this study done?

Job interviews seem to be a barrier to employment for autistic people. This is problematic, as job interviews are typically a part of the job application process.

What was the purpose of this study?

We wanted to explore how non-autistic people perceive male autistic job candidates, and how this compares with male non-autistic candidates. We also wanted investigate whether disclosing that the candidate was autistic changed the raters' judgments of candidates, and if these judgments improved if more information about autism and employment was provided.

What did the researchers do?

We showed 357 non-autistic participants short video snippets (∼10 seconds) of two “job candidates” (people who had completed a simulated job interview). Each participant was shown one video of an autistic job candidate, and one video of a non-autistic job candidate. Participants rated the candidates on two scales (employability and first impressions). After watching both videos, they chose which of the two candidates they would “hire” and gave an endorsement rating for each.

Participants were in one of three conditions. Participants in the first condition (“None”) were not given information about autism before watching the two videos. Participants in the second condition (“Brief”) were told that both of the candidates were autistic. Participants in the third condition (“Detailed”) were told that both candidates were autistic and were also provided with information about autism and the workplace. We told raters in the Brief and Detailed conditions that both the autistic and non-autistic candidate were autistic to explore if the diagnostic label influenced raters' perceptions of candidates separately to the actual diagnostic status of candidates.

What were the results of the study?

Overall, the participants rated non-autistic candidates more favorably compared with autistic candidates. Participants gave more favorable job interview ratings for candidates when they were labeled as autistic, showing the autism label made a difference to how raters perceived candidates. Participants given information about autism and employment did not rate the candidates any higher than those in other two conditions, but they did “hire” more autistic candidates than the other participants.

What do these findings add to what was already known?

The findings of this study provide some support that diagnostic disclosure may improve perceptions of autistic candidates (by non-autistic people) at job interview. Providing information about autism and the workplace in addition to disclosure may also provide some benefit, but more data are needed.

What are potential weaknesses in the study?

Our findings may not reflect real-world settings. Further studies are also needed that include people of other genders. Given the small number of stimuli videos, and the many differences between autistic people, the less favorable ratings of autistic people should be interpreted with caution.

How will these findings help autistic adults now or in the future?

The results of this study provide some evidence that there may be some benefit of disclosing an autism diagnosis during a job interview to non-autistic people. However, diagnostic disclosure is a complex and personal choice.

Keywords: disclosure, employment, first impressions, job interview, autism

Introduction

Autistic people face significant challenges accessing the job market1 reflected in low labor force engagement and high rates of unemployment or underemployment (e.g., 25%–60%).2–4 Unemployment has multidimensional impacts on autistic adults, including financial hardship, social exclusion, increased mental health challenges, and reduced quality of life and well-being.5,6 It is imperative to understand these barriers to employment, given that many autistic people have strong ambitions to work,7 and can make exceptional employees.8

The job interview

Job interviews remain the most frequent method of recruitment,9 but pose a significant barrier for autistic job seekers.10,11 Applied social skills (e.g., being able to quickly build rapport with interviewers), account for at least 75% of the evaluation of job candidates.12,13 Autistic individuals report challenges with job interviews, such as uncertainty around the level of detail required for responses to questions14 and having to practice social “niceties.”15 Moreover, autistic people are likely to be literal and honest8,16,17; thus, they may fail to downplay their weaknesses and/or amplify strengths.

First impressions

First impressions of others are formed rapidly and are resistant to change.18,19 Candidates who are perceived more favorably during the initial moments of a job interview receive higher post-interview ratings.20–23 However, experimental research suggests that autistic people are judged less favorably than non-autistic candidates, with this bias emerging early in an interaction or observation (i.e., within 10 seconds).24,25

Disclosure and knowledge

Disclosing one's diagnosis may have a positive influence on how people are perceived. Indeed, autistic people tend to be rated more favorably when they are labeled as autistic compared with when they are not,26,27 and autistic adults who have disclosed their diagnosis to their employer report higher rates of employment.28 However, although disclosure may lead to improved awareness and accommodations, it can also lead to stigma and discrimination.29 Knowledge about autism may reduce stigma,30 and has been shown to improve perceptions of autistic job candidates in a simulated context.31 There may even be interaction effects whereby diagnostic disclosure might engage positive effects of knowledge.19 To date, the impact of diagnostic disclosure of autism and potential benefits of providing information about autism within the context of a job interview has received little attention.31

The present study

In this study, we manipulated diagnostic disclosure of autism in a simulated job interview. Each participant viewed brief interview extracts from one autistic and one non-autistic actor. To experimentally isolate the label/identity, actors' actual diagnostic status (i.e., autistic and non-autistic) was manipulated across experimental conditions. Therefore, we were able to assess raters' perceptions of autistic candidates who were correctly identified as autistic, their perceptions of non-autistic actors who were incorrectly identified as being autistic, and of course both autistic and non-autistic actors in the absence of any diagnostic label. We aimed to better understand how autistic people are perceived during job interviews by non-autistic people; specifically, the impact of autism, the impact of disclosing a diagnosis, and potential benefits of providing information about autism to job interviewers.

Therefore, in this study our aims were to use a simulated job interview to (1) compare participant first impressions and employment related ratings of autistic and non-autistic male job candidates, (2) evaluate the impact of autism disclosure on these ratings (controlling for actual diagnosis), and (3) examine potential benefits of providing information about autism to raters during the diagnostic disclosure. We hypothesized that (H1) there would be a main effect for diagnosis whereby autistic candidates would be rated less favorably on all employment measures (consistent with previous research24,27), and (H2) would be less likely to be “hired” by raters than non-autistic candidates. We predicted positive main effects for autism disclosure on ratings, based on prior research.19,27,30 Specifically, we hypothesized (H3) participants would provide higher ratings on employment measures and (H4) “hire” more autistic candidates when autism was disclosed (“Brief” condition) than when no diagnostic information was provided (“None” condition), and (H5) the effect would be stronger when participants were provided with more information about autism during the disclosure (“Detailed” condition). We also hypothesized that the effect of information would be greater for autistic candidates such that (H6) there would be an interaction between diagnosis and disclosure condition, where there would be a greater improvement in ratings of autistic candidates based on the level of autism information provided relative to non-autistic candidates.

Although we predicted autistic candidates would be rated less favorably than their non-autistic counterparts (H1 and H2), this hypothesis was not a key focus of the study. Rather, we were specifically interested in the subsequent hypotheses (H3–6), namely the impact of disclosure, information, and the interactions between these factors, as well as with the actual diagnostic status (autistic and non-autistic) of the candidate. Thus, we offer a nuanced understanding of bias faced by autistic job seekers, and potential mitigation of this bias through explicit identification of diagnosis and knowledge, during the job interview. Given sex differences in previous research exploring first impressions of autistic and non-autistic job candidates,25 this study focused only on the perception of non-autistic raters on autistic and non-autistic male job candidates.

Methods

Participants

Participants were n = 357 (59% female) United Kingdom residents aged 18 years and older (Mage = 36.33 years, SDage = 12.69, range = 18–74), recruited and reimbursed through online research platform Prolific Academic.32 Inclusion criteria required participants to be age 18 or older and speak English as a first language. Recruitment experience was not a requirement to participate in the study; hence, we did not obtain each participant's recruitment experience (e.g., as an interviewer or recruiter).

Measures

Simulated interview stimuli

Four Caucasian males (two autistic, Candidates A, D; two non-autistic, Candidates B, C) were recruited to serve as “stimulus candidates” for the interview videos (six candidates were interviewed but two [one autistic, one non-autistic] were removed to ensure matching between candidates). The two autistic candidates provided their diagnostic report to the research team as evidence of autism diagnosis. Non-autistic candidates reported no autism diagnosis for themselves or first-degree family members; non-autistic status was supported by scores below the clinical cutoff (≥6) on the Autism Spectrum Quotient-10.33 No candidate reported having a clinical diagnosis of depression or anxiety. Candidates were carefully matched on the Weschler Verbal Comprehension Index34 (autistic: 102, 103; non-autistic: 105, 105), appearance (one candidate per group had dark wavy hair and was clean shaven; one candidate per group had light colored hair and facial hair of a similar shape), attire (buttoned long-sleeved shirt, tie, no jacket), and age (autistic: 25, 31 years; non-autistic: 27, 30 years).

Candidates attended an interview where they were asked 10 common job interview questions.35 Interviews were standardized by using (1) a single interviewer (L.M.D.), (2) an interview protocol, (3) professional attire, and (4) a consistent environment (i.e., room, lighting, furnishings, seating, and camera angles). All candidates were treated formally and were instructed to treat the session as a real job interview.

Pilot testing of stimuli

Based on previous research,24,25 short 10-second excerpts were selected from the interviews for pilot testing. To ensure equivalence of verbal content between candidates, we recruited Australian residents aged 18 years and above (trial one: n = 64; Mage = 29.22 years, SD = 10.42; trial two: n = 40, Mage = 39.67, SD = 10.74) and asked them to rate the extent that they endorsed the candidate (1 = Very low endorsement to 7 = Very high endorsement) after reading transcripts of the excerpts. Two trials were necessary to identify transcript excerpts that were rated similarly. A one-way repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated that transcript ratings did not differ significantly in response to the question “How would you describe yourself as a worker?” (autistic: MA = 4.15, SD = 1.31, MD = 4.43, SD = 1.30; non-autistic: MB = 4.30, SD = 1.40, MC = 4.43, SD = 1.34), F(3, 117) = 0.55, p > 0.05. We selected the videos of candidate's response to this question for the study. Final sections varied slightly in length to capture full sentences (autistic: 8, 10 seconds; non-autistic: 8, 12 seconds). Final transcripts are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Transcripts for the “Job Candidate” Videos

| Diagnostic status | Candidate | Response to interview question (time in seconds) |

|---|---|---|

| Autistic | A | “I'd like to see myself as the committed worker- like you give me the job and I'll get onto that- so that's kind of more my sort of comfort zone.” (8 seconds) |

| D | “I'm loyal… I like really like talking to people and uh, yeah I guess like, really like interacting with people and stuff like that.” (10 seconds) | |

| Non-autistic | B | “I think I'm quite creative when I need to be… And when I'm passionate I work really hard.” (8 seconds) |

| C | “I suppose my best asset as a worker is um, initiative, um, I kind of, I like to do my best at whatever I'm doing.” (12 seconds) |

Diagnostic disclosure

We created three videos that provided different levels of diagnostic disclosure of autism (Fig. 1): “None” (diagnosis not disclosed); “Brief” (candidate labeled as autistic); “Detailed” (candidate labeled as autistic, additional information about autism and employment provided). A professional with 12 years' experience assisting autistic adults into employment contributed to the development of the “Detailed” video script. All candidates were introduced as having an “excellent CV [curriculum vitae] and relevant industry experience” to explicitly indicate equivalence in terms of skills and experience.

FIG. 1.

Video scripts for the three study conditions. CV, curriculum vitae.

Candidate employability

The Candidate Employability Scale36 measures perceptions of employability along 10 dimensions (e.g., “Work motivation,” “Potential for quality ability”). Ratings range from Extremely Low (1) to Extremely High (7), with higher scores indicating greater “employability.” The scale demonstrates good psychometric properties (Herold, unpublished data, 1995),37 for this study, α = 0.90.

First impressions of candidates

The First Impression Scale for Autism24,38 comprises 10 items: Impressions (six items, e.g., “likeability”) and behavioral intent (four items, e.g., “I would hang out with this person in my free time”). Responses are reported on a 4-point scale, ranging from Strongly Agree (1) to Strongly Disagree (4). Items were coded so that higher scores for all items indicated more favorable first impressions.27 In this study, α = 0.81.

Hiring decision

We developed a dichotomous “Hiring Decision” question (“Which candidate would you be most willing to hire as a worker for any job?”), which was modeled on prior research.36,39

Endorsement Scale

Participants were asked: “If Candidate A/B was offered employment, how highly would you endorse the candidate for the position?” Responses ranged from Very low endorsement (1) to Very high endorsement (7), with higher scores indicating higher levels of endorsement.

Demographic questions

Participants were asked about their sex and gender, and whether they were autistic, had an autistic family member, autistic friend, or if they “worked often with one or more autistic individuals.”

Procedure

Ethics approval was received from the university Human Research Ethics Committee and consent was obtained from all participants, who completed the study on Qualtrics.40

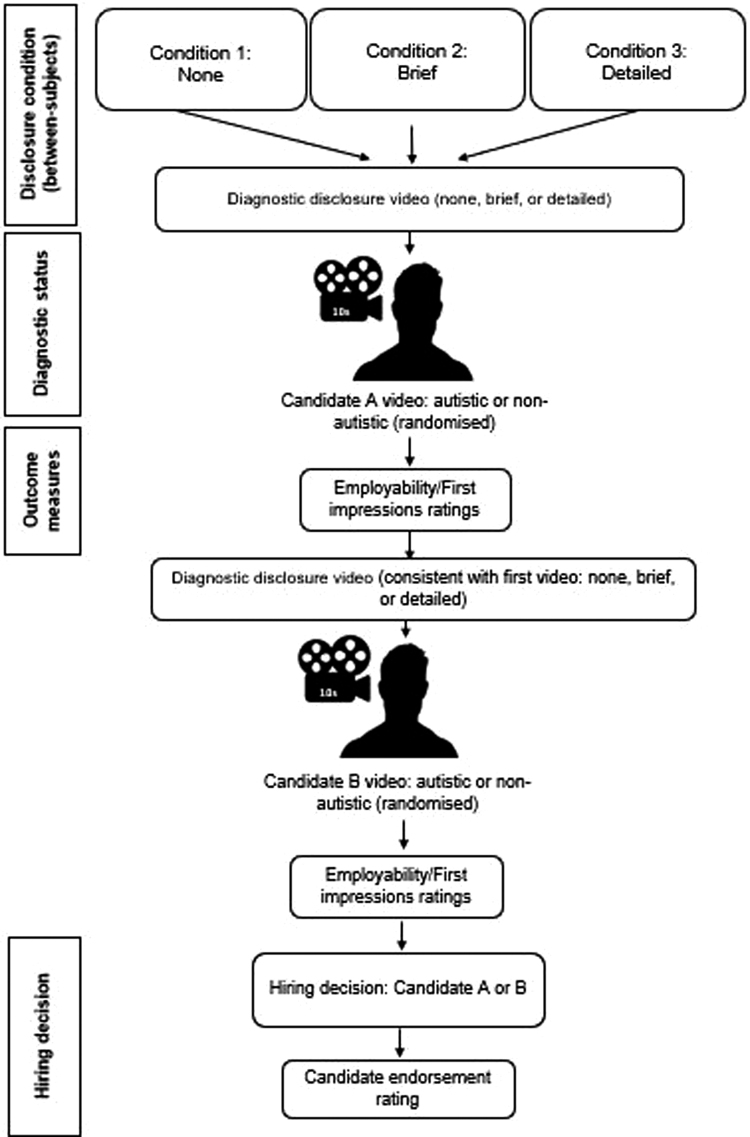

We employed a within-between subjects design (Fig. 2). Participants were randomly allocated into one of three conditions: “None,” “Brief,” or “Detailed.” Each participant viewed the interview segment video for one autistic and one non-autistic candidate (candidate presentation order counterbalanced). The condition allocation influenced the information participants were given before each candidate video (Fig. 1). In the “None” condition, neither the autistic nor the non-autistic candidate were labeled as autistic. In the “Brief” condition, both the autistic and non-autistic candidate were labeled as autistic. Finally, in the “Detailed” condition, both the autistic and non-autistic candidate were labeled as autistic, and participants were provided additional information about autism and employment (Fig. 1).

FIG. 2.

Study flow.

Participants completed an audio check to ensure the volume was at an appropriate level, before being provided the relevant disclosure information about the job candidate (introduction/disclosure video), and then the first candidate video. The participant then rated the candidate on employability and first impressions. This procedure was then repeated with the second candidate, with the same disclosure information provided as the first candidate. After viewing and providing ratings for both candidates, participants were asked to choose which of the two candidates they would “hire,” and then provide an endorsement rating for each.

To check whether participants attended to the videos, we placed attention checks after both the introduction/disclosure video and candidate video. After the introduction/disclosure video, participants in the Brief and Detailed groups were required to identify which condition was mentioned from three options: “Schizophrenia,” “Autism spectrum disorder,” and “Don't know.” After each candidate video, participants identified a shape (triangle, rectangle, circle, don't know) displayed for 3 seconds after the candidate.

Analysis

Participants who reported being autistic or having an autistic family member (n = 86) were excluded from analyses as per previous studies,19,27 given the possible impact of high autism knowledge on results. Exclusion from the sample was justified, as although the pattern of results was similar with these groups included, the level of autism information made more of a difference to the employability and hiring decision outcome. Participants were excluded for failing an attention check (n = 12), and when time taken to complete the survey fell outside three standard deviations of the mean (M = 9.82, SD = 4.45 minutes), leaving a sample of n = 255 non-autistic raters for analysis (57.6% female, Mage = 35.91, SD = 12.19). Of these, n = 48 (18.8%) reported having an autistic friend, and n = 36 (14.0%) reporting working often with one or more autistic individuals. These data are reported to characterize the sample. Owing to sample size restrictions, analyses were not conducted separately for those with some level of reported autism familiarity.

Social desirability was assessed to ensure responses were not due to participants responding in a socially desirable manner. To rule out social desirability as a possible reason for varied ratings between disclosure conditions, Pearson's product-moment correlations were calculated to determine relationships between social desirability41 and employability, first impressions, and endorsement scales. Correlations were found to be nonsignificant (all p's > 0.07). A one-way between subjects ANOVA showed no differences in social desirability between disclosure conditions, F(2, 254) = 0.24, p > 0.05; hence, social desirability was not considered further.

Using a criterion of z = ±3.29, two outliers identified for first impressions scores were reassigned the next most extreme value ± one unit.42 Response data were normally distributed.

Results

Diagnosis and disclosure effects on employment ratings

We conducted a series of 2 (Diagnosis: Autistic and Non-autistic) × 3 (Disclosure: None, Brief, and Detailed) mixed-model ANOVAs to examine main effects and interactions for the employability, first impression, and endorsement scales. Means (SDs) by diagnostic group (autistic and non-autistic) are provided in Table 2. Effect sizes for ηp2 were interpreted using Cohen's (1969)43 guidelines for small (0.009), medium (0.059), and large (0.138), considered appropriate for partial eta-squared.44 Effect sizes for d were interpreted using Cohen's45 guidelines for small (0.2), medium (0.5), and large (0.8).

Table 2.

Employability, First Impressions, and Endorsement Ratings for Autistic and Non-Autistic Candidates Across Disclosure Conditions

| Scale | Disclosure condition | n | Autistic |

Non-autistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Candidate Employability Scale | None | 86 | 43.77 (9.65) | 49.85 (8.68) |

| Brief | 82 | 47.09 (9.48) | 51.76 (8.45) | |

| Detailed | 87 | 47.82 (9.05) | 50.54 (8.09) | |

| First Impressions Scale for Autism | None | 86 | 25.58 (3.48) | 27.41 (3.12) |

| Brief | 82 | 26.94 (3.40) | 28.46 (3.46) | |

| Detailed | 87 | 27.55 (3.77) | 28.60 (3.25) | |

| None | 86 | 4.09 (1.41) | 4.97 (1.14) | |

| Endorsement Scale | Brief | 82 | 4.63 (1.42) | 5.38 (1.12) |

| Detailed | 87 | 4.78 (1.18) | 5.15 (1.01) |

Scores for the Candidate Employability Scale could range between 10 and 70. Scores for the First Impressions Scale could range between 10 and 40. Endorsement ratings could range between 0 and 7.

Employability

There was a large significant main effect for diagnosis on employability, F(1, 252) = 46.39, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.155, where participants rated autistic candidates lower on the Candidate Employability Scale than non-autistic candidates (Table 2). There was a small but statistically significant main effect for disclosure, F(2, 252) = 3.43, p = 0.034, ηp2 = 0.027; however, Bonferroni corrected pairwise comparisons failed to reveal significant differences between conditions (all p > 0.05). The Diagnosis × Disclosure interaction was not significant, F(2, 252) = 2.22, p = 0.111, ηp2 = 0.017.

First impressions

There was a medium to large significant main effect for diagnosis on first impressions, F(1, 252) = 37.34, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.129, where participants rated autistic candidates lower on the First Impression Scale for Autism than non-autistic candidates. There was a small to medium significant main effect for disclosure, F(2, 252) = 7.05, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.053, with ratings differing between disclosure conditions. The Diagnosis × Disclosure interaction was not significant, F(2, 252) = 0.91, p = 0.403, ηp2 = 0.007. Follow-up Bonferroni corrected pairwise comparisons indicated significant differences in first impressions ratings between None and Brief (p = 0.019, d = 0.36), and None and Detailed (p = 0.001, d = 0.46) conditions, with small to medium effect sizes. The difference between Brief and Detailed conditions was not significant (p > 0.05, d = 0.10).

Endorsement

There was a medium to large significant main effect for diagnosis on endorsement, F(1, 252) = 39.25, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.135, where participants rated autistic candidates lower on the Endorsement Scale than non-autistic candidates. There was a small to medium significant main effect for disclosure on endorsement ratings, F(2, 252) = 7.66, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.057, with endorsement ratings differing between disclosure conditions. The Diagnosis × Disclosure interaction was not significant, F(2, 252) = 2.09, p = 0.126, ηp2 = 0.016. Bonferroni corrected pairwise comparisons showed significant differences in endorsement ratings between None and Brief conditions (p = 0.002, d = 0.35), and None and Detailed conditions (p = 0.004, d = 0.37), with small to medium effect sizes. The difference between Brief and Detailed conditions was not significant (p > 0.05, d = 0.03).

Diagnosis and disclosure effects on hiring decision

We conducted a chi-square test of independence to compare how frequently participants chose to “hire” the autistic candidate compared with the non-autistic candidate within each disclosure condition. The chi-square test of independence showed a significant association between diagnosis and hiring selections for None, χ2 (1) = 10.47, p = 0.001, Brief, χ2 (1) = 17.61, p < 0.001, and Detailed, χ2 (1) = 5.07, p = 0.024 conditions (Fig. 3). Across conditions, participants were more likely to select non-autistic candidates than autistic candidates, with odds ratios (OR) of46: None, OR = 4.29, p < 0.001, 95% confidence interval (CI) [2.27–8.12]; Brief, OR = 7.44, p < 0.001, 95% CI [3.73–14.84]; Detailed, OR = 2.68, p = 0.002, 95% CI [1.45–4.94]. Overall, participants were over four times more likely to select non-autistic candidates than autistic candidates, OR = 4.29, p < 0.001, 95% CI [2.96–6.22].

FIG. 3.

Percentage of autistic and non-autistic candidates “hired” in each of the three conditions. Error bars represent standard error.

Endorsement ratings by hiring decision

Endorsement rating was examined separately for selected (i.e., “hired”) and unselected candidates using one-way ANOVAs. There was no significant difference in participant endorsement ratings of the autistic (M = 5.47, SD = 0.94) and non-autistic (M = 5.52 SD = 0.86) selected candidates F(1, 253) = 0.20, p = 0.652, ηp2 < 0.001. By contrast, there was a significant difference in participant endorsement ratings of autistic (M = 4.03, SD = 1.29) and non-autistic (M = 4.41 SD = 1.17) unselected candidates, F(1, 253) = 5.00, p = 0.026, ηp2 = 0.019 with a small effect size, where participants provided lower endorsement ratings of unselected autistic candidates than non-autistic candidates.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the impact of the disclosure of an autism diagnosis on the perceptions of job interview performance of male autistic and non-autistic job candidates. We found that participants gave autistic candidates less favorable ratings across all employment measures compared with non-autistic candidates, and that when the diagnostic label was provided, participants gave candidates (both autistic and non-autistic) more favorable ratings.

Across all conditions (“None,” “Brief,” and “Detailed”) autistic job candidates were rated less favorably and were less likely to be “hired” by participants, compared with their non-autistic counterparts. Unfavorable perceptions of autistic people by non-autistic raters have been consistently reported in various contexts24,25,27 and were, therefore, anticipated (H1 and H2). Although interesting, given the small number of stimuli videos, and the heterogeneity of autism, this finding should be interpreted with caution.

Participants gave more favorable ratings of candidates when an autism diagnostic label was provided (supporting H3), and this finding held regardless of actual diagnostic status (i.e., ratings were higher in the “Brief” label condition for both autistic and non-autistic candidates than in the “None” condition). This finding of a positive impact of a diagnostic label is consistent with Sasson and Morrison,27 and our results extend this finding to the job interview context. Sasson and Morrison posit that provision of the diagnostic label may improve perceptions of autistic people by non-autistic people by way of providing an explanation for “atypical” or different behavior. In contrast, the apparent advantage of non-autistic over the autistic candidates who were “hired” was unaffected when a diagnosis was disclosed (thus, there was no support for H4). Indeed, we found that the discrepancy increased in favor of non-autistic candidates.

Given greater autism knowledge has been associated with improved ratings of autistic people,27,31 we examined whether ratings of autistic candidates would improve if we provided additional information about autism and employment (i.e., “Detailed” condition). We predicted that this effect would be stronger than diagnostic disclosure alone (H5). Although employment ratings (employability, first impressions, and endorsement) were more favorable when more information about autism was provided compared with when there was no diagnostic disclosure, this effect was no stronger than in the disclosure without information condition. Notably, however, we observed a slightly lower preference for “hiring” the non-autistic candidate in this condition compared with the other two conditions—Although participants were over four times more likely to hire the non-autistic than the autistic candidate in the no disclosure and disclosure only conditions, this rate was reduced by approximately one third when participants were provided with additional information about autism and the workplace.

Autistic job seekers are likely to undertake careful risk-benefit analyses when they consider whether or not to inform prospective employers that they are autistic, and those who refrain from disclosing are often concerned mostly about negative perceptions from others.47 Taken together, the findings of this study provide some support for diagnostic disclosure as improving perceptions of autistic candidates at job interview. Nevertheless, as our findings relate to a contrived environment, these findings may not translate to a “real-world” setting and caution is recommended when considering disclosure during a job interview. Every situation must be assessed on its own merits as there remains a risk that disclosure may disadvantage applicants. Although our findings were not overwhelmingly in support of advantages when providing information about autism, we do recommend that workplaces and recruiters be informed about autism, and particularly the often simple ways in which autistic employees can be supported in the workplace thereby enabling them to excel. It is likely, however, that targeted training is required to change people's behavior with respect to how autistic people are perceived, understood, and supported in the workplace.

Limitations

In this study, we explored the perception non-autistic raters had of autistic and non-autistic male job candidates. Although we recognize that the job interview is a likely barrier for autistic people of all genders, we wanted to control for as much variability as possible in the experimental stimuli for this initial pilot study as possible. We recognize that there is a need for more research including autistic cisgender and transgender women and gender nonconforming participants. Males were chosen as the focus for this initial study, given recent research reporting that male autistic job candidates received poorer ratings in a simulated job interview than autistic females.25 It was also beyond the scope of this study to include recruiters as participants. Although first impressions have been found to be similar for experienced versus inexperienced recruiters,48 it would be of interest to know whether results might be different if all raters were people with recruitment experience. Similarly, examining the influence of rater familiarity with autism on ratings is an important future avenue for research. Training for job interviewers (e.g., that includes presentations from autistic people), or by including autistic people, or people familiar with autism on interview panels, may be beneficial for improving employment outcomes for autistic people.

Implications and conclusion

Diagnostic disclosure seems to have largely positive impacts on the ratings by non-autistic people of autistic (and non-autistic) job candidates, at least under experimental conditions. Providing additional autism information did not seem to improve these ratings further, but did have a positive impact on the hiring decision by reducing the gap (OR) between autistic and non-autistic selections. Importantly, our findings suggest both explicit and implicit bias (i.e., when diagnosis was provided and when it was concealed) on the part of non-autistic raters will likely need active intervention and education to mitigate. Given the primary differences in the way that autistic individuals communicate, close examination of hiring processes, and particularly the job interview is warranted to improve equity of access to employment for autistic people.

Acknowledgments

We thank the actors who appeared in the stimulus videos, and the participants in this study. We also thank Kat Denney for her assistance in formatting the article.

Authorship Confirmation Statement

R.L.F. and D.H. conceived and designed the study. L.M.D. conducted the study and collected the data under the supervision of R.L.F. and D.H. L.M.D. and R.L.F. analyzed the data. R.L.F., L.M.D., and D.H. wrote the article, R.L.F. formatted and led the revision of the article, and all authors approved the final version.

We confirm that the study described here has not been published previously, that it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, that its publication is approved by all authors and by the responsible authorities where the study was carried out, and that, if accepted, it will not be published elsewhere in the same form, in English or in any other language, including electronically, without the written consent of the copyright holder.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

At the time of the study, Darren Hedley was supported by funding from DXC Technology, the Australian Government Department of Defence, and the ANZ Bank. During a period of time while the article was being prepared, Rebecca Flower's position was supported by the Cooperative Research Centre for Living with Autism (Autism CRC), established and supported under the Australian Government's Cooperative Research Centres Program. Darren Hedley is currently supported by a Suicide Prevention Australia National Suicide Prevention Research Fellowship. The authors declare no further conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Hedley D, Uljarević M, Cameron L, Halder S, Richdale A, Dissanayake C. Employment programs and interventions targeting adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Autism. 2017;21(8):929–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, 2018. Cat No. 4430.0. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roux AM, Shattuck PT, Rast JE, Rava JA, Anderson KA. National autism indicators report: Transition into young adulthood. April 15, 2015. https://drexel.edu/autismoutcomes/publications-and-reports/publications/National-Autism-Indicators-Report-Transition-to-Adulthood (last accessed June 8, 2020).

- 4. Taylor JL, Seltzer MM. Employment and post-secondary educational activities for young adults with autism spectrum disorders during the transition to adulthood. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(5):566–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Howlin P. Social disadvantage and exclusion: Adults with autism lag far behind in employment prospects. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(9):897–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M. Adult outcome for children with autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):212–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baldwin S, Costley D, Warren A. Employment activities and experiences of adults with high-functioning autism and Asperger's disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(10):2440–2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hillier A, Campbell H, Mastriani K, et al. Two-year evaluation of a vocational support program for adults on the autism spectrum. Career Dev Transit Except Individ. 2007;30(1):35–47. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ryan AM, Ployhart RE. A century of selection. Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65:693–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Higgins K, Koch LC, Boughfman EM, Vierstra CV. School-to-work transition and Asperger syndrome. Work. 2008;31(3):291–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Strickland DC, Coles CD, Southern LB. JobTIPS: A transition to employment program for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(10):2472–2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huffcutt A, Conway J, Roth PL, Stone NJ. Identification and meta-analytic assessment of psychological constructs measured in employment interviews. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(5):897–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salgado JF, Moscoso S. Comprehensive meta-analysis of the construct validity of the employment interview. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2002;11(3):299–324. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Müller E, Schuler A, Burton BA, Yates GB. Meeting the vocational support needs of individuals with Asperger syndrome and other autism spectrum disabilities. J Vocat Rehabil. 2003;18(3):163–175. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hurlbutt K, Chalmers L. Employment and adults with Asperger syndrome. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabil. 2004;19(4):215–222. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kalandadze T, Norbury C, Nærland T, Næss KB. Figurative language comprehension in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analytic review. Autism. 2018;22(2):99–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zalla T, Amsellem F, Chaste P, Ervas F, Leboyer M, Champagne-Lavau M. Individuals with autism spectrum disorders do not use social stereotypes in irony comprehension. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ambady N, Bernieri FJ, Richeson JA. Toward a histology of social behavior: Judgmental accuracy from thin slices of the behavioral stream. In Zanna MP, ed. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. Vol. 32. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000;201–271. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morrison KE, Debrabander KM, Faso DJ, Sasson NJ. Variability in first impressions of autistic adults made by neurotypical raters is driven more by characteristics of the rater than by characteristics of autistic adults. Autism. 2019;23(7):1817–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barrick MR.Swider BW, Stewart, GL. Initial evaluations in the interview: Relationships with subsequent interviewer evaluations and employment offers. J Appl Psychol. 2010;95(6):1163–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dougherty TW, Turban DB, Callender JC. Confirming first impressions in the employment interview: A field study of interviewer behavior. J Appl Psychol. 1994;79(5):659–665. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Macan TH, Dipboye RL. The effects of interviewers' initial impressions on effects gathering. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1988;42:364–387. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Swider BW, Barrick MR, Harris TB. Initial impressions: What they are, what they are not, and how they influence structured interview outcomes. J Appl Psychol. 2016;101(5):625–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sasson NJ, Faso DJ, Nugent J, Lovell S, Kennedy DP, Grossman RB. Neurotypical peers are less willing to interact with those with autism based on thin slice judgments. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cage E, Burton H. Gender differences in the first impressions of autistic adults. Autism Res. 2019;12(10):1495–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Butler RC, Gillis JM. The impact of labels and behaviors on the stigmatization of adults with Asperger's disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(6):741–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sasson NJ, Morrison KE. First impressions of adults with autism improve with diagnostic disclosure and increased autism knowledge of peers. Autism. 2019;23(1):50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ohl A, Grice Sheff M, Small S, Nguyen J, Paskor K, Zanjirian A. Predictors of employment status among adults with autism spectrum disorder. Work. 2017;56(2):345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lindsay S, Osten V, Rezai M, Bui S. Disclosure and workplace accommodations for people with autism: A systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;7:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gillespie-Lynch K, Brooks PJ, Someki F, et al. Changing college students' conceptions of autism: An online training to increase knowledge and decrease stigma. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(8):2553–2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McMahon C M, Henry S, Linthicum M. Employability in autism spectrum disorder (ASD): Job candidate's diagnostic disclosure and ASD characteristics and employer's ASD knowledge and social desirability. J Exp Psychol Appl. 2021;27(1):142–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Palan S, Schitter C. Prolific.ac—A subject pool for online research. J Behav Exp Finance. 2018;17:22–27. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Allison C, Auyeung B, Baron-Cohen S. Toward brief “red flags” for autism screening: The short autism spectrum quotient and the short quantitative checklist for autism in toddlers in 1,000 cases and 3,000 controls. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(2):202–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wechsler D. WASI: Wechsler Abbreviated Scales of Intelligence. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bolles R. What Color Is Your Parachute? A Practical Manual for Job-Hunters and Career-Changers. 2016 ed. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Krefting LA, Brief AP. The impact of applicant disability on evaluative judgments in the selection process. Acad Manag J. 1976;19(4):675–680. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dalgin RS, Bellini J. Invisible disability disclosure in an employment interview: Impact on employers' hiring decisions and views of employability. Rehab Couns Bull. 2008;52(1):6–15. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morrison KE, DeBrabander KM, Jones DR, Faso DJ, Ackerman RA, Sasson NJ. Outcomes of real-world social interaction for autistic adults paired with autistic compared to typically developing partners. Autism. 2020;24(5):1067–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roberts LL, Macan TH. Disability disclosure effects on employment interview ratings of applicants with nonvisible disabilities. Rehabil Psychol. 2006;51(3):239–246. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Qualtrics [computer program]. Version 2.16. Provo, UT: Qualtrics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stöber J. The social desirability scale-17 (SDS-17): Convergent validity, discriminant validity, and relationship with age. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2001;17(3):222–232. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 6th ed. New York: Pearson; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Richardson JT. Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educ Res Rev. 2011;6(2):135–147. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Field A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. 5th ed. London, UK: SAGE Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Romualdez M, Heasman B, Walker Z, Davies J, Remington A. “People might understand me better”: Diagnostic disclosure experiences of autistic individuals in the workplace. Autism Adulthood. 2021;3(2):157–167. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Derous E, Buijsrogge A, Roulin N, Duyck W. Why your stigma isn't hired: A dual-process framework of interview bias. Hum Resour Manage Rev. 2016;26(2):90–111. [Google Scholar]