SUMMARY

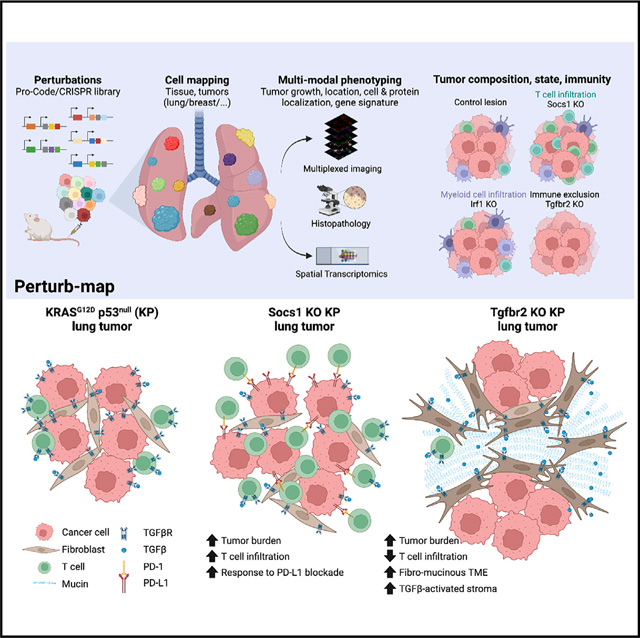

While CRISPR screens are helping uncover genes regulating many cell-intrinsic processes, existing approaches are suboptimal for identifying extracellular gene functions, particularly in the tissue context. Here, we developed an approach for spatial functional genomics called Perturb-map. We applied Perturb-map to knock out dozens of genes in parallel in a mouse model of lung cancer and simultaneously assessed how each knockout influenced tumor growth, histopathology, and immune composition. Moreover, we paired Perturb-map and spatial transcriptomics for unbiased analysis of CRISPR-edited tumors. We found that in Tgfbr2 knockout tumors, the tumor microenvironment (TME) was converted to a fibro-mucinous state, and T cells excluded, concomitant with upregulated TGFβ and TGFβ-mediated fibroblast activation, indicating that TGFβ-receptor loss on cancer cells increased TGFβ bioavailability and its immunosuppressive effects on the TME. These studies establish Perturb-map for functional genomics within the tissue at single-cell resolution with spatial architecture preserved and provide insight into how TGFβ responsiveness of cancer cells can affect the TME.

Graphical Abstract

In brief

A spatial functional genomics platform termed Perturb-map combines CRISPR pools, multiplex imaging, and spatial transcriptomics to enable the identification of genetic determinants of tumor composition, organization, and immunity.

INTRODUCTION

The cellular composition, spatial architecture, and tissue localization of a tumor have a major impact on a cancer’s progression and response to therapy. These factors are particularly relevant to tumor immunity as immune cell composition and localization within the tumor microenvironment (TME) is one of the major determinants of response to immunotherapy and patient outcome (Binnewies et al., 2018). Spatially resolved single-cell and regional sequencing has revealed that many genetically distinct subclones exist in proximity to tumors and can have different TME compositions (Lomakin et al., 2021; Mitra et al., 2020); however, how specific genes influence the TME (Galluzzi et al., 2018), or how neighboring clones influence one another is not well defined. Indeed, while some genes involved in orchestrating the TME have been identified, the potential roles of many genes in influencing the architecture and immune composition of different tumors are not established.

Identifying the genes controlling the cellular arrangement of tumors is a challenge. TME composition is complex; composed of many different immune and nonimmune cell types whose ratio, location, and movement are all interdependent factors (Binnewies et al., 2018). Many gene functions are dependent on the context of a tissue and spatial proximity to specific cell types and structures (Haigis et al., 2019). For example, T cell migration from tissues to lymph nodes is dependent on the chemokines CCL19 and CCL21 (Hauser and Legler, 2016). The functions of these genes, and their receptor CCR7, only fully emerge in the context of a discrete tissue and organ arrangement that includes lymphatics and vasculature. This is not unique to immune cells or chemokines and applies to many classes of genes. Thus, determining which of the many 100s of genes expressed in a tumor influence TME composition and arrangement ultimately requires in vivo studies.

To scale up the studies of gene functions, pooled CRISPR screens are increasingly being used (Doench, 2018; Shalem et al., 2015) Single-cell sequencing approaches, such as Perturb-seq, and high-dimensional cytometry have further advanced CRISPR screens by enabling the molecular and phenotypic changes caused by gene perturbation to be measured more comprehensively (Adamson et al., 2016; Dixit et al., 2016; Jaitin et al., 2016; Mimitou et al., 2019; Wroblewska et al., 2018). However, while pooled approaches enable scaled throughput, existing technologies have limitations for in vivo studies. One of the most significant is that tissue is dissociated for analysis. This largely restricts the biological functions that can be probed with pooled screens to cell-intrinsic processes, as the extracellular effects of a gene perturbation cannot be assessed once tissues are homogenized. This excludes using CRISPR genomics to identify genes controlling phenotypes that require spatial resolution to assess, such as immune cell localization or vascular density within a tumor. Furthermore, gene functions mediated extrinsically can potentially be compensated by adjacent cells that do not carry the same KO. Thus, with current pooled CRISPR approaches, it is not readily feasible to determine the functions of a secreted factor, such as a chemokine or interleukin, or a regulator of one of these factors, as the local effects from KO in a small fraction of cells cannot be measured or could be counteracted by cells with a normal copy of the same gene. Recently, a novel approach was described for detecting barcoded CRISPR vectors by imaging, which was shown to enable assaying of pooled screens without cell disruption (Feldman et al., 2019). This is a very powerful high-resolution technology but has not yet been used for tissue-level analysis.

Here, we describe an approach for in vivo spatial functional genomics, called Perturb-map. Perturb-map is based on a protein bar code (Pro-Code) system that utilizes triplet combinations of a small number of linear epitopes to create a higher order set of unique bar codes that can mark cells expressing different CRISPR gRNAs (Wroblewska et al., 2018). We show that 120 different Pro-Code expressing cancer cell populations can be detected within a tumor at single-cell resolution and tissue scale. We applied Perturb-map to KO 35 genes in parallel in a mouse model of lung cancer and simultaneously assessed how each gene KO influenced key parameters of tumor biology, including growth, histopathology, immune composition, and molecular state. Among our findings, we observed that KO of the TGFβ receptor 2 (Tgfbr2) gene resulted in a growth advantage and led to the conversion of the TME to a fibro-mucinous state and exclusion of T cells, while Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (Socs1) KO also provided a growth advantage but was accompanied by accumulation of T cells in the tumor. Spatial transcriptomics indicated the loss of TGFβ signaling on cancer cells led to increased TGFβ activation of tumor stroma, which likely facilitated T cell exclusion. A striking finding, revealed by our ability to assess different gene perturbations in parallel in situ, was how spatially segregated the effects of Socs1 and Tgfbr2 KO were, as T cell infiltration and exclusion were tightly confined to the Socs1 and Tgfbr2 lesions, respectively, even when the two were in adjacent proximity.

These studies establish Perturb-map for broad phenotypic analysis of dozens of genes in parallel within a tissue or tumor at cellular resolution with spatial architecture preserved and provide a scaled means for identifying the determinants of TME biology.

RESULTS

In situ detection of 120 Pro-Code populations in lung and breast tumors by multiplex imaging

In previous studies, we described a protein-based vector/cell bar-coding system, the Pro-Codes, which is composed of triplet combinations of linear epitopes (e.g., FLAG, HA, etc.) fused to a scaffold protein, dNGFR (Wroblewska et al., 2018). As the Pro-Codes are detected by antibodies, we hypothesized that they could be resolved by imaging. To test this, we generated cancer lines expressing the Pro-Codes. We transduced mouse KrasG12D p53−/− (KP) lung cancer cells (DuPage et al., 2009; Wieckowski et al., 2015) and 4T1 breast cancer cells (4T1) with a pool of lentiviral vectors (LV) encoding 84 or 120 different Pro-Codes.

We injected mice i.v. with KP cells or into the mammary fad pad for 4T1 cells. After 2 weeks (4T1) or 4 weeks (KP), the tumor-bearing tissue was collected and stained for each of the Pro-Code epitopes using a method we previously developed for high-dimensional imaging, called multiplex immunohistochemistry consecutive staining on a single slide (MICSSS) (Remark et al., 2016) (Figure S1A). Alternatively, tissue sections were imaged on a multiplex ion beam imager (MIBI) (Figures S1A and S1B). Each epitope could be efficiently detected with both techniques at subcellular resolution, as we could detect the epitopes at the cell membrane, as expected from the membrane-localizing dNGFR scaffold. We were therefore able to spatially resolve up to 120 Pro-Codes in breast (Figures 1A and 1B) and lung (Figure 1C) tumor models.

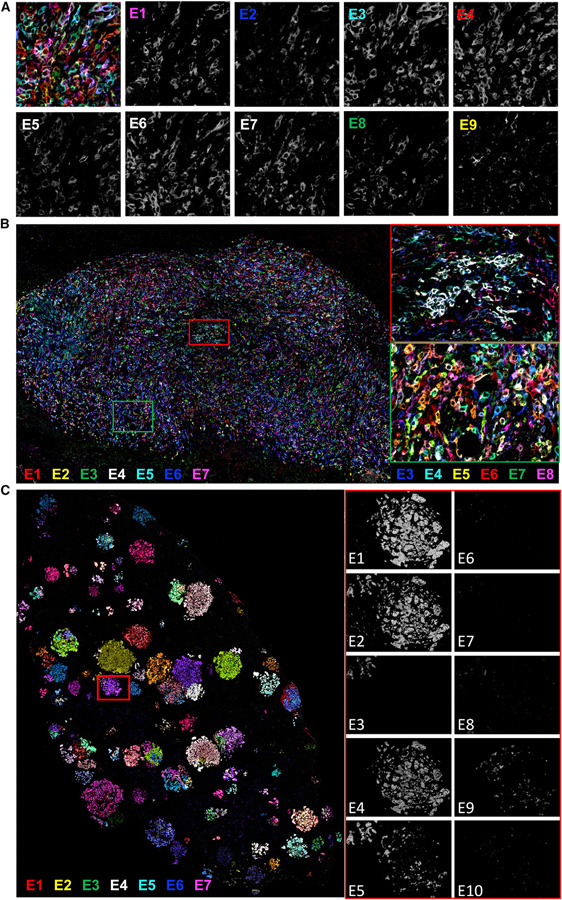

Figure 1. Multiplex imaging maps Pro-Code labeled breast and lung cancer populations in situ.

(A and B) Representative image of memPC-expressing 4T1 breast tumor (84 memPC, 9 tags). Multiplex imaging performed by MICSSS. Seven tags shown simultaneously in (B), color coded as indicated. Image representative of >10 tumors (n = 10 mice), from 2 different experiments with 84 or 120 memPC.

(C) Representative image of memPC labeled KP tumor lesions in the lung (120 memPC, 10 tags). Imaging performed by MICSSS. Seven tags represented simultaneously; color coded as indicated. Image representative of 10 mice, from 2 different experiments with different memPC libraries.

Although we could readily detect each of the Pro-Code epitopes, membrane stains are not optimal for cell segmentation. This is because generally available imaging software for cell segmentation does not have precision accuracy in identifying cell borders (Greenwald et al., 2021), which hinders efficient debarcoding of membrane-bound Pro-Codes (memPC). Since cell nuclei are accurately identified by segmentation software, we created a new set of 165 Pro-Codes utilizing a nuclear localizing mCherry fluorescent protein (mCherry-NLS) as a scaffold. We confirmed the detection of each nuclear Pro-Code (nPC) by CyTOF (Figures S1C and S1D). Next, we transduced 4T1 and KP with a library of 120 nPC and repeated the experiments above (Figure S1A). We were able to detect each of the 120 unique nPC in both the lung and breast tumor models and found that they localized to the nucleus (Figure 2A). Importantly, Pro-Codes were not prompting immune rejection in the model, as Pro-Code expression did not significantly alter lung tumor burden (Figures S1E and S1F). We also detected each Pro-Code epitope, indicating that immune clearance of specific epitope-tag-expressing cells did not occur, similar to previous findings for memPC (Wroblewska et al., 2018).

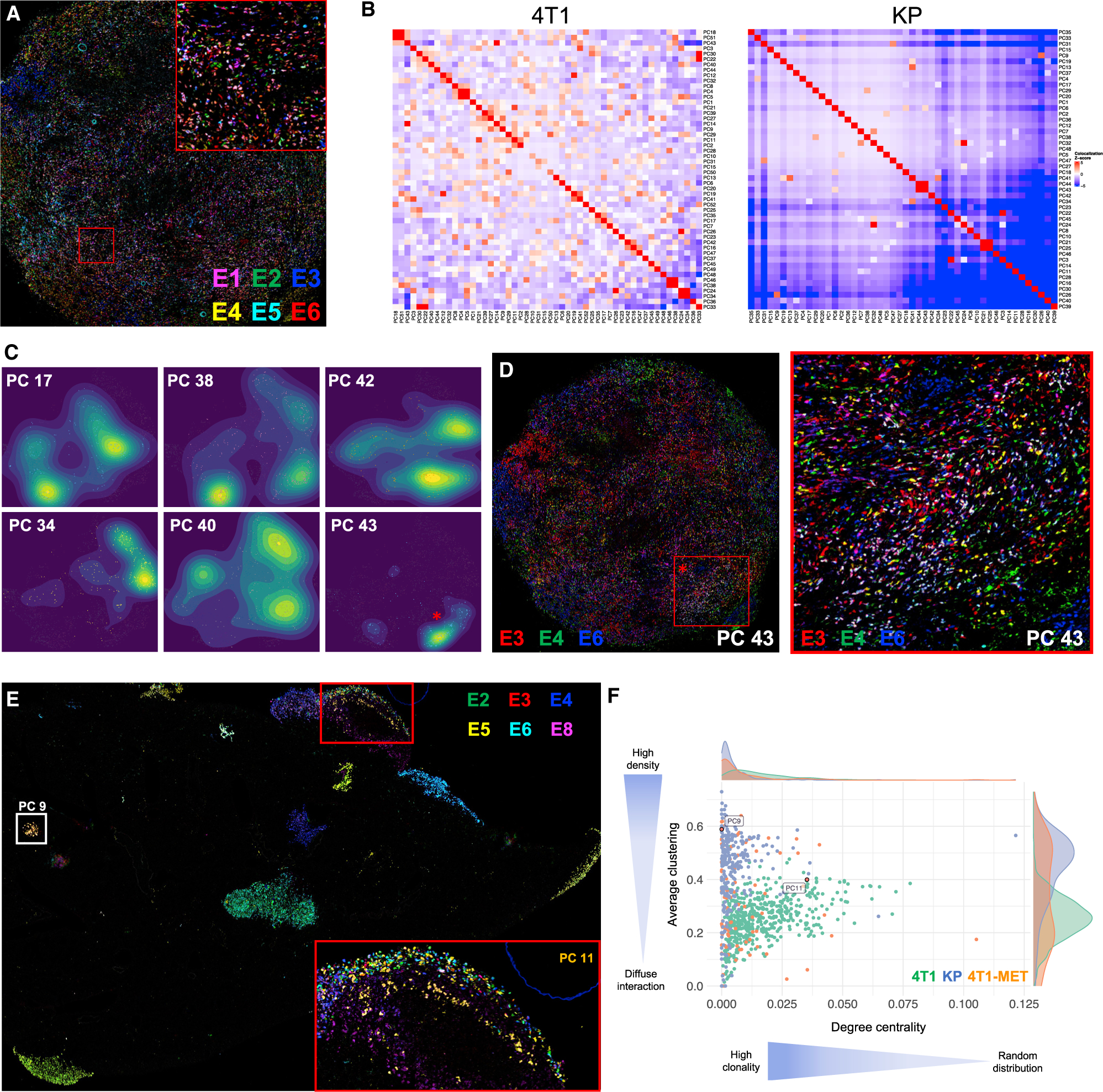

Figure 2. Analysis of tumor development by Pro-Code mapping reveals tumor clonal heterogeneity.

(A) Representative image of nPC-labeled 4T1 breast tumor (120 nPC, 10 tags). Six tags are represented. Image representative of 16 tumors, across 2 different experiments with different nPC libraries.

(B) Colocalization analysis quantifying the interactions between nPC populations in a breast tumor (left) or lung tumor lesions (right) (with 120 nPC, 10 tags). Each square represents an interaction between two nPC populations and is color coded based on the significance of the interaction relative to a permuted null distribution generated by swapping Pro-Code labels (1,000 permutations). Shown are a representative tumor from 10 tumors across 5 mice (4T1) and a representative lung lobe from 15 lobes across 3 mice (KP).

(C) Density maps of 6 randomly selected nPC populations from the 4T1 breast tumor displayed in 2D. The star corresponds to the example highlighted in Figure 2D.

(D) Overlaid image of the 3 tags corresponding to Pro-Code 43 (PC 43), color coded as indicated. Cells expressing the 3 tags (i.e., PC 43) appear white.

(E) Representative image of nPC 4T1 breast metastases in the lung (120 nPC, 10 tags), from 8 mice and 40 lung lobes. Six tags are represented. PC 9 (white square) and PC 11 (gold cells in the left square) are highlighted.

(F) Comparative clonal analysis of 4T1 primary breast tumors in the mammary fat pad (green), KP tumor lesions in the lung (blue), and 4T1 metastases in the lung (orange). Plotted are the average clustering coefficient and group degree centrality (fraction of alternate nPC neighbors) from a neighbors graph constructed on nPC+ cells (k = 10, maximum cell radius 40 μm). Each point represents one nPC on an individual tissue section. Only nPC present in >20 cells on a tissue section is displayed.

Since memPC and nPC have a distinct subcellular localization, we hypothesized that we could use them in combination in the same cells. We transduced 4T1 with a library of 56 memPC (8 tags), sorted dNGFR+ cells, and transduced again with a library of 56 nPC that had the same 8 tags. The cells were injected into mice, as above (Figure S1G). In the resulting tumors, we detected mCherry and NGFR on the same cells, and we were able to identify cells expressing a different Pro-Code in the nucleus and at the cell membrane. Although challenges in segmenting the memPC make it difficult to calculate all the Pro-Code combinations in these tumors, the potential combinations of barcoded cells are up to 3,136 with only 8 tags (Figures S1H and S1I).

Pro-Code imaging reveals KP lung and 4T1 breast tumor clonality

An immediately apparent difference revealed by imaging the Pro-Codes in the two tumor types was the highly heterogeneous distribution of Pro-Codes in 4T1 tumors compared with KP lung tumors, in which almost all of the tumor lesions were clonal, as evident by being positive for a single Pro-Code (Figures 1B, 1C, and S1B). This implied that each KP tumor lesion is initiated by a single KP cancer cell.

To further analyze the clonal dynamics, we assessed colocalization between Pro-Code populations within 4T1 primary tumors and KP tumor lesions, after cell segmentation, Pro-Code assignment, and 2D digital reconstruction (Figures S2A and S2B). For each pair of Pro-Code populations, a Z-score was calculated based on the number of observed neighbor interactions on the tissue relative to random swappings of cell labels (see methods). Z-scores confirmed that KP tumors were highly clonal, as each Pro-Code population exhibited relatively frequent homotypic interactions (Figures 2B and S2C). Although the 4T1 cells appeared to be randomly distributed, colocalization analysis also showed a certain degree of clonality, which could be seen by mapping individual Pro-Codes, as specific Pro-Code-expressing cells tended to cluster together (Figure S2D).

To understand how regional clusters were forming, we visualized the relative regional abundance of Pro-Code-positive cells using kernel density estimation (Figure 2C). This revealed that cells within the primary 4T1 lesion spread from one or several foci, with the cell density decreasing as the distance from the focal point increases. Although this phenomenon was not apparent on complex overlaid images (Figures 1B and 2A), it became apparent when we only represented a single Pro-Code (Figures 2C and 2D). This indicates a diffuse clonality characteristic of 4T1 in the primary tumor and supports a model in which 4T1 cancer cells migrate locally from a focal point of origin.

We sought to use the Pro-Codes to assess clonal heterogeneity of 4T1 metastasis. We injected nPC-4T1 into the mammary fat pad to generate breast tumors. After 4 weeks, to allow for lung metastasis, we collected the lungs and stained sections for the Pro-Codes (Figure 2E). Many of the metastases were homogeneous for a single Pro-Code, indicating they had originated from a single cell from the primary tumor. However, there were also metastatic lesions in the lung that contained a mix of Pro-Code expressing cells, suggesting either multicell seeding or that initial seeding by a clone was followed by additional metastatic cells. We compared the clonal heterogeneity of KP lung, 4T1 breast, and 4T1 metastasis in lung (Figure 2F). This confirmed distinct spatial patterning of each tumor context, with KP lung tumors having high clonality and low mixing, 4T1 primary tumors having diffuse clonality, and 4T1 metastases in the lung developing clonally but also with a bimodal pattern in the density of interactions, reflecting the presence of mixed metastases.

Perturb-Map identifies regulators of sensitivity to immunoediting and tumor architecture

CRISPR screens have helped identify some of the genes involved in cancer immunity (Lawson et al., 2020; Manguso et al., 2017; Patel et al., 2017), but as noted, current approaches are not suited to study many key aspects of tumor immunology, such as immune cell recruitment and exclusion. We set out to determine whether we could use the Pro-Codes to create a platform for resolving CRISPR screens in situ.

We built a library of nPC/CRISPR LV vectors targeting 35 genes coding for regulators of cytokine signaling pathways (including receptors for IFNα, IFNγ, TGFβ, and TNFα) and ligands and secreted factors involved in immune cell interactions (e.g., B2m, Cd47, Cd274, and Cxcl17) (Figure 3A). The genes were selected for their involvement in pathways associated with human responses to cancer immunotherapy (Keenan et al., 2019). Although these genes are known to have immune functions, their roles in lung TME biology are not fully established. As a control, we targeted the F8 gene, which is not expressed by KP cells. For each of the 35 genes, KP-Cas9 were transduced with three different LV, with each vector expressing the same nPC but a different gRNA targeting the same gene. The 35 populations of nPC/CRISPR KP were then pooled, and the frequency of each nPC/CRISPR population was confirmed to be in similar distribution by CyTOF. Phenotypic analysis by CyTOF of direct or downstream targets (PD-L1, CD24, and CD47) of specific CRISPRs in the library indicated efficient KO of the cognate genes (Figure S3A). For example, >95% of cells encoding CRISPRs targeting Cd47 and Cd274 (Pd-l1) had an undetectable expression of CD47 and PD-L1, respectively. Similarly, Jak1, Jak2, Stat1, Irf1, and a majority of Ifngr2 Pro-Code/CRISPR KP cells did not upregulate PD-L1 in response to IFNγ, whereas Socs1 Pro-Code/CRISPR KP cells upregulated PD-L1 to a greater extent. This is consistent with IFNγ as an inducer of PD-L1 expression (Gocher et al., 2021) and demonstrated efficient gene KO in library transduced cells.

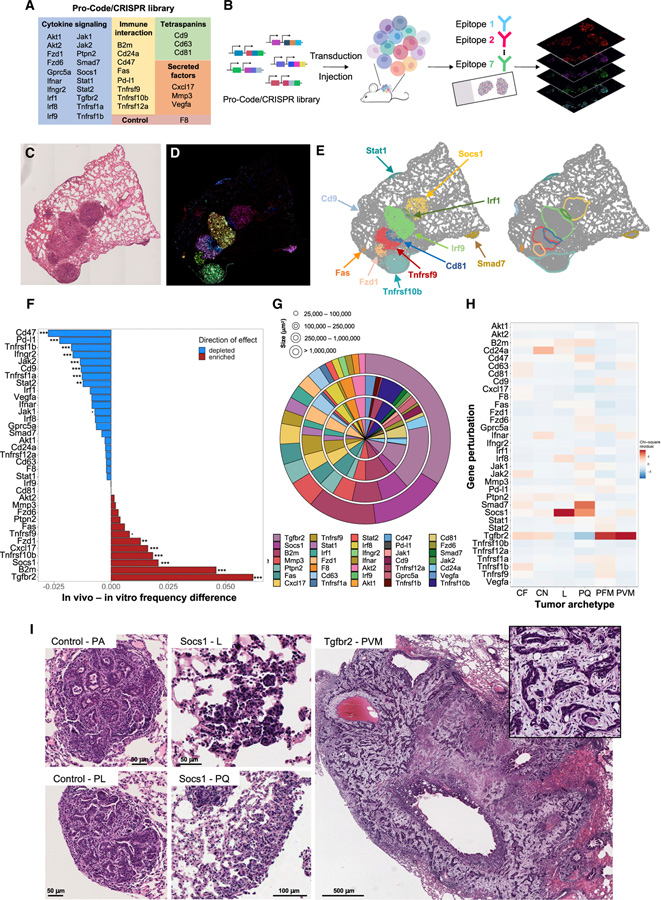

Figure 3. Perturb-map identifies genes regulating tumor development and architecture in vivo.

(A) Table of the genes targeted in the Pro-Code/CRISPR library.

(B) Perturb-map experimental pipeline. For the studies in Figures 3 and 4, KP-Cas9 were transduced with the nPC/CRISPR library in (A) and injected into 11 mice from 2 independent experiments (n = 5 and 6). Lungs were collected after 4 weeks, and Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections were prepared and stained for 7 tags to detect 35 nPC populations and for specific cell markers (see Figure 4). Sections imaged by whole slide scanning.

(C–E) Overview of the Perturb-map analysis pipeline. (C) Representative H&E section of 1 lung lobe from a mouse. (D) Overlay of pseudocolored nPC tag staining for the same tissue section as in (C). Different colored areas correspond to different nPC populations. (E) Debarcoded and reconstituted digital image of the tissue section in (D). (Left panel) Each dot represents a cell, colored based on nPC expression (nPC negative cells in gray). Gene perturbation can be annotated directly on the image based on nPC expression. (Right panel) Tumor boundaries were defined following DBSCAN clustering of nPC+ cells.

(F) Relative frequency of nPC/CRISPR KP tumors. The frequency of each nPC/CRISPR KP-Cas9 population was determined pre-injection (by CyTOF) and compared with the relative abundance of corresponding nPC/CRISPR lesions in vivo. Significant differences in tumor engraftment were determined using a one-sample two-tailed Poisson exact test comparing to F8 engraftment as the null hypothesis. Poisson rate parameters were determined by the ratio of formed tumor lesions in vivo to the number of cells in vitro pre-injection for each KO (. = p < 0.1; * = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001).

(G) Quantification of tumor lesions’ size across gene perturbations. Shown are percentages of tumors associated with each gene perturbation within discrete tumor size categories. Each ring corresponds to a tumor size range as indicated. Perturbations are organized in clockwise order from Tgfbr2, following the order represented in the figure legend.

(H) Histopathology analysis of nPC/CRISPR tumor lesions. Total of ~1,750 tumors was scored on H&E sections (with no Pro-Code staining) and tumor histopathological archetype identified. The heatmap shows the standardized residuals of a chi-squared test between gene perturbation and tumor archetype (chi-squared p value 4.43 × 10−14).

(I) Representative example of tumor archetypes associated with Socs1 and Tgfbr2 gene KO. PA, parenchymal; PL, pleural; L, lepidic; PQ, pleural plaque; PVM, perivascular mucinous tumor.

We injected the cells i.v. into Cas9-expressing mice (n = 11) to seed tumors, and after 4 weeks, we collected the lungs for tumor analysis (Figure 3B). Tissues were sectioned and stained for the Pro-Code by MICSSS. For each sample, we stained serial sections with H&E or with antibodies specific for the Pro-Code epitope tags (Figures 3C and 3D). The images were then segmented and debarcoded to identify the Pro-Codes expressed by each tumor lesion (Figure 3E, left panel). We used the density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) algorithm to subcluster Pro-Code populations into discrete lesions and inferred tumor boundaries using alpha shapes followed by manual curation (Figure 3E, right panel). We used Pro-Code identification to determine the CRISPR expressed in each tumor. From 11 mice injected with the nPC/CRISPR KP cells, we identified ~1,750 distinct Pro-Code-expressing tumors.

To determine whether any of the targeted genes impacted tumor development in vivo, we compared the proportion of tumors carrying a specific nPC/CRISPR to the relative frequency of the same nPC/CRISPR in the preinjected cell mix (as determined by CyTOF) (Figure 3F). There was no change in the relative proportion of our control, F8, as well as several other targeted genes, but there were substantial changes in the frequency of a number of nPC/CRISPR, inferring the associated genes influence tumor growth. Two of the most depleted gene targets were the immune checkpoints Cd274 (Pd-l1) and Cd47, indicating loss of these genes impaired KP growth and implying KP tumors subdue both innate and adaptive immune pathways for development. Conversely, there was a significant enrichment of B2m targeted lesions, indicating loss of MHC class I presentation facilitated tumor growth, which further signified a role for adaptive immune control.

In contrast to what has been reported in many in vitro CRISPR screens, including our own (Wroblewska et al., 2018), we observed a de-enrichment of CRISPRs targeting positive regulators of IFNγ signaling (Ifngr2, Jak1, Jak2, and Irf1), along with enrichment of CRISPR targeting Socs1, a negative regulator of IFNγ signaling (Krebs and Hilton, 2001). While this differs from in vitro and some in vivo findings, it is consistent with studies from the Minn lab which found KO of Ifngr on certain cancer cells can enhance immune control (Benci et al., 2016, 2019). Of note, Tgfbr2 targeted lesions were the most enriched in vivo indicating loss of the TGFβ receptor on KP cells enhanced tumor growth. Tgfbr2 tumors were also among the largest tumors in area, along with Socs1 and B2m (Figure 3G), which were also amid the most enriched.

In addition to being able to measure the number and area of tumor lesions associated with a gene KO, Perturb-map enabled us to assess how different genes affected tumor architecture. To do so, each lesion was scored by a pathologist (blinded to the perturbations) following a list of standard clinical criteria that included the differentiation degree of the cancer cells, the location of lesion, and the composition of the stroma (Figures S3B and S3C). Distinct tumor histological types were identified based on a combination of features, including necrosis, fibrosis, and differentiation. We performed a chi-squared test to identify significant associations between gene perturbations and histological characteristics of the lesions (Figures 3H, S3C, and S3D). Interestingly, gene perturbations of Socs1 and Tgfbr2 led to the development of markedly different KP lung tumor lesions. Loss of Socs1 correlated to the development of pleural plaques and lepidic tumors, two poorly differentiated tumor lesion types. Loss of Tgfbr2 resulted in a remodeling of the stroma and induced the development of highly fibro-mucinous tumors (Figures 3H, 3I, S3B, S3C, and S3D). This was not related to tumor size or lesion number, as both Socs1 and Tgfbr2 targeted lesions were similar in this regard but had very distinct histological states. These studies indicate loss of Tgfbr2 and Socs1 alters KP lung tumor architecture in profoundly different ways, but each confers a growth advantage.

Perturb-Map identifies genes modulating the immune composition of the TME

We next aimed to use Perturb-map to investigate how different gene perturbations impact immune cell recruitment and maintenance in and around tumor lesions. To do this, we stained lung tissue sections that were stained for the Pro-Codes with antibodies for T (CD4, CD8), B (B220), and myeloid (F4/80, CD11b, CD11c) cell markers, as well as for EpCAM, an adhesion molecule that marks epithelial cells and is expressed by KP cells. Pro-Code debarcoding identified the border and gene perturbations associated with each tumor (Figure 4A). The coordinates of each immune cell type were then used to determine their relative position to each tumor lesion and to calculate the density of immune infiltrates in the different tumors (Figures 4B and 4C). Moreover, we measured mean EpCAM intensity within the tumor borders. Tumor lesions for each gene perturbation were then compared with control lesions (F8 CRISPR) using a Wilcoxon test. We excluded from the analysis any gene perturbation that was not found in at least 20 tumor lesions in vivo. The resulting Z-scores and p-values were represented in radial plots, which indicate the relative infiltration (outside facing bars) or exclusion (inside facing bars) of each immune cell type within the indicated nPC/CRISPR tumors (Figure 4D).

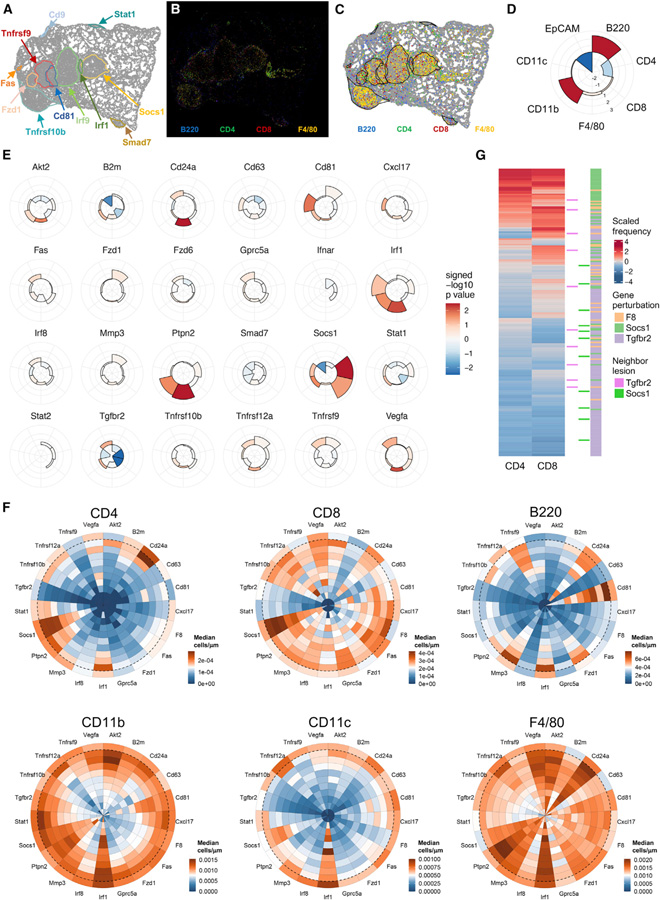

Figure 4. Perturb-map analysis of immune composition in gene KO tumor lesions.

(A–D) Perturb-map analysis pipeline for the quantification of immune infiltration and EpCAM expression. Analysis was performed on lung tissue collected from mice described in Figure 3 (n = 11 mice, 2 separate experiments, 41 lung lobes, 2 images/lobe, for a total of 8,442,439 cells analyzed). (A) Representative example of an in silico reconstituted image displaying tumor boundaries (the same section as Figures 3C–3E, digital image shown is from the right panel of Figure 3D for perspective). (B) Representative image of immune infiltration in KP lung tumor lesions. Lung tissue sections stained for Pro-Code and B220, CD4, CD8, CD11b, CD11c, F4/80, and EpCAM using MICSSS. Color coded as indicated. (C) Cells positive for each immune markers are displayed in the in silico Pro-Code tumor map and quantified within each tumor lesion. (D) Schematic of a radial plot used to visualize the immune landscape associated with each gene perturbation. Each fraction corresponds to immune cell density, or mean intensity of EpCAM staining, within the tumor border. Bar height represents the Z-score of the difference in medians between control tumors (n = 55) and tumors carrying gene perturbations. Color indicates the −log10 adjusted p value of a Wilcoxon rank-sum test of the same comparison.

(E) Analysis of immune infiltration and exclusion in Pro-Code/CRISPR lung tumors. Shown are radial plots indicating immune density (and EpCAM expression) of tumors with the indicated gene perturbation. Radial plots are organized as in (D). Gene perturbations with fewer than 20 lesions were excluded from the analysis.

(F) Analysis of the immune cell distribution within tumor lesions. Each slice represents lesions with a specific gene perturbation. The median cell density was calculated in 10% window increments from the tumor border (dashed line) to the tumor core, and in the 10% window expanding outward. Only tumors >100,000 μm2 were used for the median calculation.

(G) Examination of T cell density in F8, Socs1, or Tgfbr2 tumors related to their proximity to Socs1 or Tgfbr2 tumors. The heatmap represents the Z-score of log-transformed CD4+ and CD8+ T cell density (censored at the 95th percentile) in control (F8), Socs1, and Tgfbr2 tumors. Tumors neighbored by a Socs1 or Tgfbr2 lesion (boundary distance less than 75 μm) are identified.

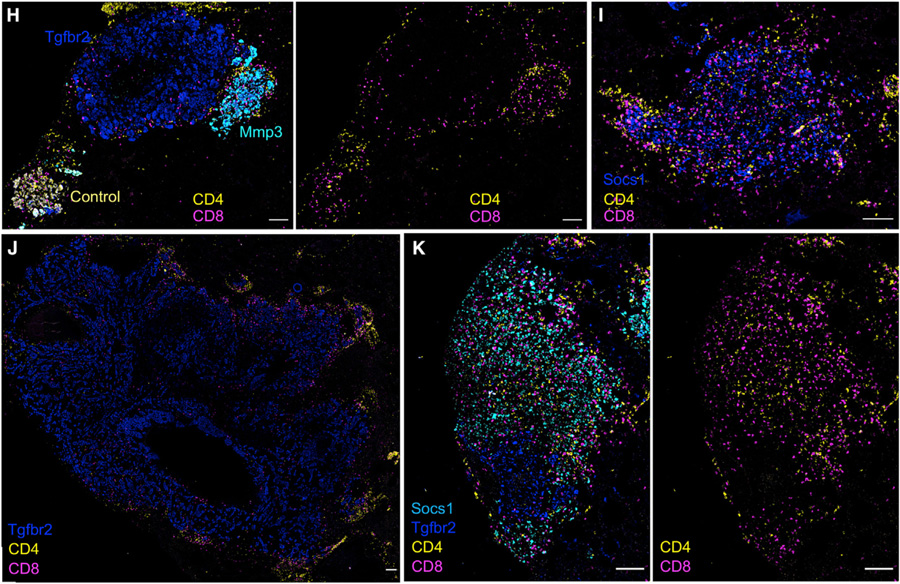

(H–K) Representative examples of CD4+ (yellow) and CD8+ (purple) T cell infiltration within indicated tumor lesions. Annotated gene perturbations were identified based on Pro-Code expression.

Specific patterns of immune infiltration were found in lesions with different gene perturbations (Figure 4E). For example, in tumors in which the CRISPR targeted B2m, which is required for antigen-dependent interactions with CD8+ T cells, there was a specific reduction in CD8+ T cells, supporting the need for TCR/pMHC interactions to maintain T cells in the TME. Loss of Irf1 and Ptpn2 both led to increased infiltration of myeloid cells (F4/80+ and CD11b+) and to a lesser extent CD4+ T cells. Although Irf1 KO tumors had an enrichment in CD11c+ cells, potentially indicating an enrichment in DCs, which did not occur in Ptpn2 KO lesions. Tgfbr2 KO and Socs1 KO lesions, which were both enriched in vivo, displayed inverted patterns of immune composition. Tgfbr2 lesions were markedly excluded of immune cells, especially CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Figures 4E–4J and 4K), whereas Socs1 lesions were highly infiltrated by T cells (Figures 4E–4G, 4I, and 4K). Socs1 tumors also had lower levels of EpCAM expression. This is suggestive of altered differentiation, consistent with the histopathology of Socs1 KO tumors that were predominately found to be moderate to poorly differentiated (Figures S3C and S3D).

In addition to quantitating immune infiltration, we could also assess the spatial distribution of immune cells within each tumor lesion (Figure 4F). In general, immune cells were more concentrated in the outer area of tumors, particularly CD4+ and CD11c+ cells. However, there were notable differences in specific KO lesions. For example, in Irf1 lesions, CD11c+ cells were enriched throughout the tumor, and in the Socs1 lesions enrichment of CD4+ and CD8+ cells penetrated the tumor core (Figures 4F, 4I, and 4K). Since Socs1 KO led to higher PD-L1 on KP cells (Figure S3A), we hypothesized that local T cell dysfunction might reconcile the observed enrichment of Socs1 KO tumors despite their increased T cell infiltration. To test this, we separately injected mice with a 1:1 mix of KP-Cas9-F8-gRNA and KP-Cas9-Socs1-gRNA cells and treated with anti-PD-L1 or isotype control antibody (Figure S4A). PD-L1 blockade decreased overall tumor burden (Figure S4B), consistent with the de-enrichment of Pd-l1 KO tumors in vivo (Figure 3F). The mice treated with the control antibody had a higher number of Socs1 KO tumors compared with F8 tumors (median of 32.5% F8 and 67.5% Socs1), but when we treated the mice with anti-PD-L1, the ratio flipped, and the Socs1 tumors were more depleted (median of 79% F8 and 21% Socs1), indicating that Socs1 KO made the tumors more responsive to PD-L1 blockade (Figure S4C).

Metastatic lesions can evolve divergent molecular states and even within a single tumor mass genetic subclones can form spatially distinct regions with different TME compositions (Mitra et al., 2020); however, how adjacent, genetically heterogeneous regions might influence each other is not well explored. We sought to use Perturb-map to investigate whether neighboring tumors influenced the immune infiltration of one another. We identified control (F8), Socs1, and Tgfbr2 tumors that were in contact with a neighboring Tgfbr2 or Socs1 tumor and clustered them based on T cell infiltration. Socs1 tumors were dominant in lesions highly infiltrated by T cells, whereas Tgfbr2 tumors were mainly excluded in T cells (Figures 4G–4J), as observed from our previous analysis (Figures 4E and 4F). Notably, tumor lesions with an adjacent Socs1 KO tumor did not tend to display higher T cell infiltration, while tumor lesions neighbored by Tgfbr2 KO tumors were not more excluded in T cells (Figure 4G). Even when Tgfbr2 KO lesions were directly adjacent to a highly infiltrated Socs1 KO lesion, the Tgfbr2 KO lesion remained immune excluded (Figure 4K). This suggests, at least in the case of SOCS1 and TGFβ pathway alterations, that in lung tumor lesions in close contact with each other, the composition and spatial arrangement of immune cells is shaped very locally. Although this is likely dependent on the specific molecular alterations, as some gene expression changes may have more distal effects, Perturb-map can provide a scaled means to assess how specific genetic alterations influence local, proximal, and distal TME states.

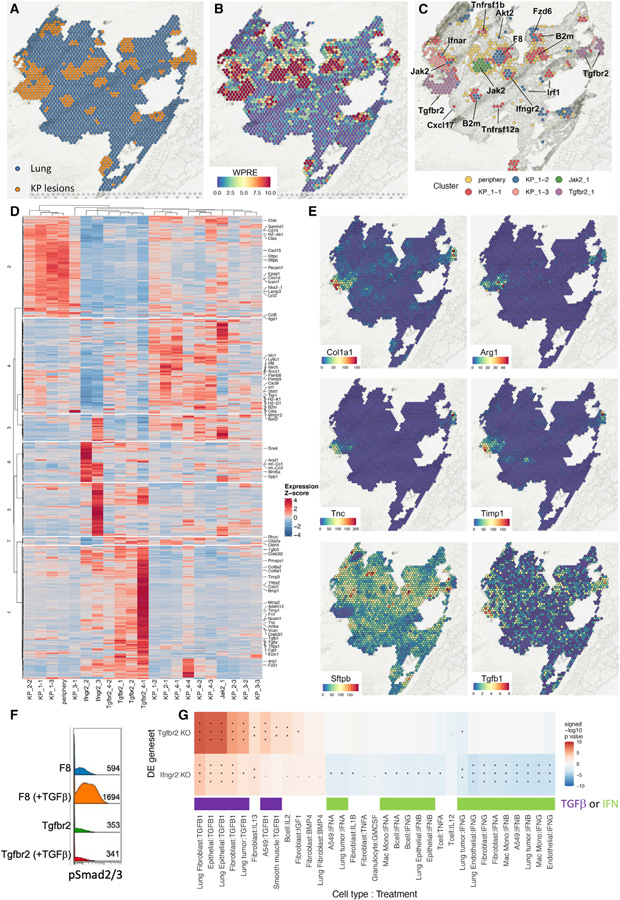

Perturb-Map spatial transcriptomics identifies perturbation-associated molecular signatures

To further determine the influence of different gene perturbations on tumor state, we paired spatial transcriptomics with Perturb-map. We applied the 10× Visium technology on four sections of mouse lungs seeded with KP tumors expressing the nPC/CRISPR library. Differential expression of k-means derived clusters distinguished a specific gene signature in spatial domains corresponding to tumor lesions (Figures 5A and S5A). In contrast to healthy surrounding lung tissue, tumor lesions highly expressed specific keratins and epithelial markers (e.g., Krt8, Krt18, and Epcam) (Figure S5B). We also found an IFNγ signature in KP lesions, including upregulation of the antigen presentation pathway (e.g., Nlrc5, Tap1, Psmb8, and Psmb9), IFNγ signaling pathway (e.g., Stat1, Irf1, and Socs1), and IFNγ-induced chemokines (e.g., Cxcl9 and Cxcl10) (Figure S5B). Of note, Pro-Code transcripts were captured distinctly and specifically localized within tumor cluster regions (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Perturb-map with spatial transcriptomics identifies perturbation-specific gene signatures.

(A) K-means clustering of KP lesions and noninvolved lung from a representative tissue section profiled by spatial transcriptomics (10× Visium).

(B) Unique molecular identifier (UMI) counts of reads mapping to the WPRE region of the Pro-Code transcript in each Visium spot.

(C) Leiden clustering of Pro-Code+ spots. Gene perturbations were annotated based on imaging mass cytometry. Additional clusters include spots corresponding to the tumor periphery (periphery) or KP lesions not specific to a particular gene KO (labeled KP followed by tissue section ID and an arbitrary cluster number).

(D) Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Ifngr2 and Tgfbr2 spot clusters. Genes and spot cluster mean profiles were hierarchically clustered using Pearson correlation distance and average agglomeration. Color corresponds to the row Z-score of log SCTransform corrected counts.

(E) UMI counts for indicated transcripts.

(F) KP-Cas9 expressing F8 or Tgfbr2 gRNAs were treated for 16 h with TGFβ (20 ng/mL), stained for phosphorylated Smad2 and Smad3 (pSmad2/3), and analyzed by flow cytometry. Numbers indicate the median fluorescence intensity.

(G) GSEA using CytoSig derived gene sets for different cell types and treatment conditions. Average log2 fold-change of DEGs (Bonferroni-adjusted p value < 0.01) in the listed signature were used as input. p value sign indicates direction of enrichment (. = p < 0.1; * = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001).

Graph-based clustering of tumor spots defined by Pro-Code transcripts revealed distinct and repeated tumor gene expression signatures across lung sections (Figures 5C and S5C). Consistent with the clonal development of KP tumors, spatial domains corresponding to a given lesion often clustered together, but there were also specific lesions that clustered distinctly from the rest. To identify the gene perturbations in each lesion, we imaged a serial section of lung tissue stained with metal-conjugated antibodies to each Pro-Code epitope tag by imaging mass cytometry (Figure S5D). The identification of nPC/CRISPRs within the tissue allowed us to annotate each gene signature with the corresponding gene perturbation and revealed that many tumors carrying CRISPRs targeting Tgfbr2 or Ifngr2 presented a distinct gene signature compared with other KP tumors (Figures 5C and S5C), as indicated by unbiased clustering. There were also clusters that corresponded to KP lesions but were not specific to any gene KO, and thus we labeled them as different KP clusters (e.g., KP_1-2, KP_1-3, etc.). It should be noted that since relatively few lesions of each perturbation were sampled by Visium, this likely affected the ability to resolve distinct clusters for each KO.

Gene expression was averaged for tumor clusters on each Visium section, which contained tumor-bearing lung tissues from separately injected mice and then hierarchically clustered to reveal consistent gene signatures across sections associated with particular tissue regions or perturbations (Figure 5D). Spatial domains located at the periphery of tumor lesions were characterized by the upregulation of Cxcl15, a neutrophil attractant, Lyz2 and Lamp3, markers of myeloid cells, and high levels of the MHC Class II machinery, including H2-Ab1 and Cd74. This was consistent with the increased density of immune cells around the tumor boundary observed in our imaging data (Figure 4F). Ifngr2 KO tumors exhibited significantly reduced expression of IFNγ-stimulated genes (ISG), including Irf1 and Cxcl9, as well as many genes involved in antigen presentation, such as H2-k1, H2-d1, Ciita, Nlrc5, Tap1, Psmb8, and Psmb9.

In Tgfbr2 KO tumors, many of the same ISGs were also downregulated, likely due to the T cell excluded state of the tumors, and there was an increase of various collagen-coding genes, including Col1a1, Col6a1, and Col6a2 (Figures 5D and 5E), consistent with the presence of a fibro-mucinous stroma (Figures 3H and 3I). Unexpectedly, many of the genes upregulated in the Tgfbr2-targeted tumors indicated increased TGFβ signaling, including Tnc, Timp1, and Arg1, which are induced by TGFβ (Calon et al., 2012; Kwak et al., 2006; Mondanelli et al., 2017; Yoon et al., 2021) (Figure 5E), as well as Cald1 (Figure 5D), which is a TGFβ-induced gene expressed by cancer-associated fibroblasts (Tauriello et al., 2018). Elastin (Eln), a gene that is very highly and specifically upregulated by TGFβ in lung fibroblasts (Figures S5E and S5F), was also upregulated in Tgfbr2 KO tumors (Figure S5G). Sftpb, which is negatively regulated by TGFβ (Wesselkamper et al., 2005), was downregulated. Notably, Tgfb1 and Tgfb3, ligands of the TGFβ Receptor, were also upregulated in the Tgfbr2 lesions (Figures 5D and 5E).

The induction of TGFβ-induced genes in Tgfbr2 tumors prompted us to test the reactivity of the KP/Tgfbr2 CRISPR cells to TGFβ. This confirmed that they did not activate TGFβ signaling (measured by phosphorylation of SMAD2/3) in response to TGFβ, and that TGFBR2 was indeed functionally knocked out in these cells (Figure 5F). We thus sought to understand which other cell types in the Tgfbr2 KO TME might be responding to TGFβ. Although Visium does not yet provide single-cell resolution, transcriptomic data from purified populations can be used to infer cell-type responses. To make this inference, we utilized the CytoSig database (Jiang et al., 2021). Representative gene sets were created between relevant treatment and cell-type pairs, and then a gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was carried out to identify these specific cytokine signatures in different tumor clusters.

The most enriched gene signature in Tgfbr2 KO lesions corresponded to TGFβ-activated lung fibroblasts (Figure 5G). Although lung tumor cell TGFβ signatures were also enriched, the induced genes largely overlapped with those in fibroblasts. Since Tgfbr2 KO KP cancer cells did not respond to TGFβ (Figure 5F), and several of the upregulated genes are specific to TGFβ-activated fibroblasts including Cald1 and Eln (Figure S5G), this makes it highly likely that the TGFβ signature is originating from fibroblasts in the Tgfbr2 KO tumors.

These findings demonstrate that a consequence of Tgfbr2 loss on KP lung cancer cells is increased TGFβ expression in the tumor along with TGFβ pathway activation in the TME. This suggests a potential mechanism for the stroma remodeling and immune exclusion we observed in the Tgfbr2 KO lesions is TGFβ activation of cancer-associated fibroblasts (Derynck et al., 2021). They also demonstrate that spatial transcriptomics can be incorporated into Perturb-map to provide unbiased molecular analysis of different gene perturbations in a spatially resolved manner.

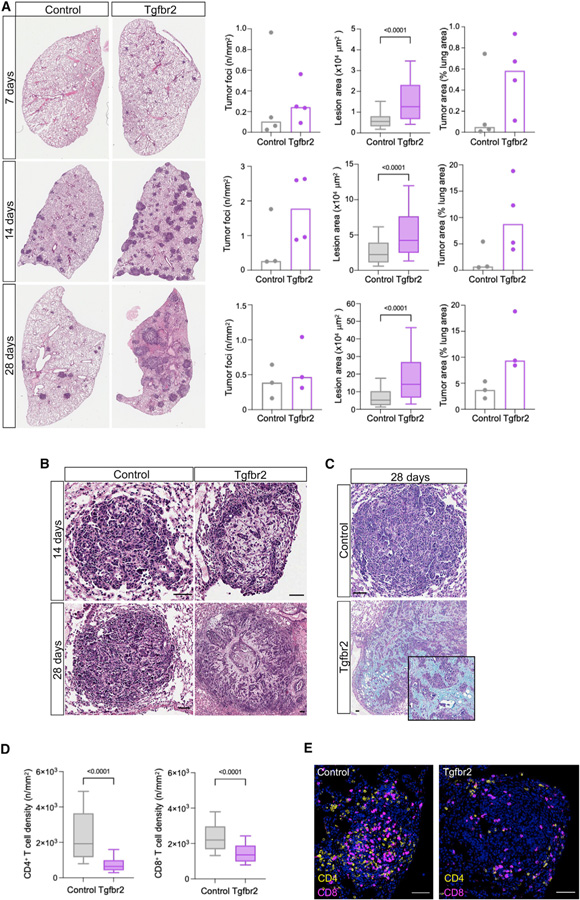

Validation that loss of Tgfbr2 results in more aggressive and T cell-excluded KP lung tumors

We sought to confirm the Perturb-map phenotype associated with Tgfbr2 KO tumors. To do this, we transduced KP-Cas9 cells with LV encoding gRNAs targeting F8 (control) or Tgfbr2 and injected the cells i.v. into Cas9 mice. We harvested lungs at 7, 14, and 28 days after injection and examined tumor burden. Within 7 days of injection, there was already evidence of larger and more abundant Tgfbr2 KO tumors compared with control. This was even more apparent at later times in which individual Tgfbr2 KO tumor lesions were >2-fold bigger than control lesions, resulting in ~10% of the lung area being covered by Tgfbr2 KO tumors compared with ~4% for the control (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. Kinetics of Tgfbr2 KO and control KP lung tumor development.

(A) Comparison of lung tumor burden between mice bearing control or Tgfbr2 KO KP tumors (n = 3–4 mice/group/time point). Whole lung sections were stained with H&E. A representative lung lobe is shown for each condition. Density of tumor lesion (left graph), lesion size (middle graph), and total tumor area (right graph) were quantified. Lesion area across samples was analyzed using a Mann-Whitney test.

(B) Representative examples of control or Tgfbr2 KO tumor lesions stained with H&E. Scale bars, 50 mm.

(C) Representative examples of control or Tgfbr2 KO tumor lesions stained with Alcian blue and PAS. Scale bars, 50 mm.

(D) Quantification of CD4+ (left) and CD8+ (right) densities in tumor lesions across all samples at 14 day. Statistical significance was determined using a Mann-Whitney test.

(E) Representative image of T cell infiltration in a control or Tgfbr2 KO tumor lesion. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Similar to what we observed with Perturb-map, many of the Tgfbr2 tumors had a fibro-mucinous stroma (apparent in some lesions by the 2-week time point), which was not observed with control tumors (Figure 6B). This was validated by Alcian blue staining, which binds acidic mucins (Steedman, 1950) and marked regions of the Tgfbr2 KO tumors (Figure 6C). Furthermore, as we had observed in the Perturb-map screen, there was a significant decrease in CD4+ and CD8+ T cell infiltration within Tgfbr2 tumors (Figures 6D and 6E). This confirms that the loss of Tgfbr2 remodels the TME of KrasG12D p53null lung tumors.

DISCUSSION

These studies establish an approach for functional genomics that enables pooled CRISPR screens to be resolved within the tissue by multiplex imaging and spatial transcriptomics. A key advance of Perturb-map is that it broadens the types of genes and gene functions that can be investigated in functional genomics screens. Most sequencing-based pooled screening approaches require dissociation of cells or tissues for analysis, and this results in loss of information about how a perturbation might affect a cell’s local environment. As noted above, this has largely restricted CRISPR genomics to screening for cell-intrinsic gene functions, often related to how a gene influences cell fitness under a selective pressure or expression of a specific phenotypic marker (Doench, 2018; Shalem et al., 2015). By imaging the Pro-Codes in tissue, Perturb-map enabled us to assess how different gene perturbations not only altered tumor fitness for seeding and growth but also tumor morphology and immune cell recruitment.

Our initial application of Perturb-map focused on a small set of immune cell types for analysis, but any cell type or protein that can be detected by antibody staining could be included for study. As there are multiplex imaging techniques and instruments that can detect as many as 60 proteins on a single tissue section, more extensive detection of cell types and cell states is possible (Goltsev et al., 2018; Jackson et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2018). It is worth noting that Perturb-map, as presented here using MICSSS, does not require any special instrumentation or reagents and should therefore be feasible for most labs to carry out (Akturk et al., 2020).

Beyond examining tumor morphology and immune cell recruitment, the ability to readout CRISPR screens by imaging can enable scaled studies to identify genes that control many other processes important to tumor biology, such as protein localization in a cell, tumor organization, cell migration and invasion, and cell-cell interactions. Moreover, because Perturb-map is compatible with tissue analysis, it can be applied to study genes dependent on factors only available in vivo. For example, a cell receptor may have little function in vitro because its ligands are not present in the culture media but will mediate signaling in a tissue in which stromal cells express its ligand. The coupling of spatial transcriptomics with Perturb-map provided an unbiased means to determine how specific gene perturbations altered the molecular state of a tumor. This expands the possible applications of Perturb-map for discovering gene functions and can help provide mechanistic insights into phenotypic observations, as we found in Tgfbr2 KO lesions.

We used Perturb-map to screen the contributions of specific genes on lung cancer biology. The de-enrichment of Pd-l1 KO tumors supported the utility of the approach for investigating tumor immunity. Cd47-targeted tumors were also significantly deenriched, suggesting that KP tumors protect themselves from macrophage clearance with the CD47 “don’t eat me signal” (Feng et al., 2019). We recently reported that tissue-resident macrophages provide a supportive niche during early lung tumor growth (Casanova-Acebes et al., 2021), and it may be that CD47 is needed to keep this beneficial relationship from becoming carnivorous.

We also found that suppression of IFNγ signaling impaired KP tumor growth. This was somewhat unexpected as there is good evidence that IFNγ is important for tumor immunity, and mutations in JAK/STAT have been associated with resistance to checkpoint blockade (Gao et al., 2016; Zaretsky et al., 2016). However, a more complicated view of IFNγ’s role has emerged, which indicates that it can have both pro and antitumor effects (Benci et al., 2016, 2019; Gocher et al., 2021). The opposing effects are related to IFNγ’s activity in inducing both antigen presentation pathways and checkpoint ligands and other immunosuppressive molecules, in cancer cells, as well as IFNγ’s different effects on cancer and immune cells (Benci et al., 2019). Interestingly, though KO of Ifngr2 and Jak1 reduced tumor burden, Stat1 KO did not. This was not due to KO efficiency, as Stat1 was efficiently deleted (Figure S3A). A possibility is a compensation from STAT3- or STAT1-independent mechanisms of IFNγ signaling (Gil et al., 2001) in KP lung tumors. Our results also indicated enhancement of IFNγ signaling specifically in cancer cells, through Socs1 KO, facilitated tumor growth. Notably, increased growth occurred despite increased T cell infiltration in the Socs1 KO lesions. Recruitment of T cells was likely facilitated by increased release of IFNγ-induced T cell attractants, such as CXCL9. While protection from killing appeared to be due, at least in part, to Socs1 loss resulting in increased PD-L1, as treatment with anti-PD-L1 led to a significant reduction in Socs1 KO tumor burden. Socs1 could be a good therapeutic target to pair with PD1/PDL1 blockade, as SOCS1 inhibition may enhance T cell infiltration while the effects of upregulated PD-L1 can be blunted.

Perturb-map analysis found that Tgfbr2 KO tumors were more abundant, larger, and mucinous than control tumors and had excluded T cells, which we confirmed occurred even at early stages. While TGFBR2 mutations are not prevalent in lung cancer, several studies have shown that TGFBR2 mRNA and protein are markedly downregulated in human lung tumors, and downregulation correlates with poor survival (Borczuk et al., 2005; Malkoski et al., 2012). Different functions of TGFBR2 on lung cancer cells likely contribute to this outcome, including control of cell cytostasis and apoptosis (Batlle and Massagué, 2019), but our data suggest that immune exclusion may play a role. TGFβ has been shown to promote immune exclusion (Derynck et al., 2021; Mariathasan et al., 2018; Tauriello et al., 2018). Thus, it was counter-intuitive that loss of the receptor resulted in cold tumor lesions. However, spatial transcriptomics seemed to reconcile these findings by indicating that TGFβ and TGFβ signaling was upregulated in the TGFβ KO lesions and acting on the stroma. Hence, despite the cancer cells not being responsive to TGFβ, the immune and stroma cells were still TGFβ sensitive and subject to its suppressive and remodeling effects. The enrichment in TGFβ transcripts may derive from the Tgfbr2 KO cancer cells or from activated fibroblasts in the lesions. In addition to TGFβ being upregulated, loss of the TGFβ receptor on the dominant cell type in the lesion, the cancer cells, may have had the effect of increasing the bioavailable TGFβ in the lesion, which would increase TGFβ’s relative concentration on the immune and stroma compartments. Changes in the extracellular state of Tgfbr2 KO tumors may also have increased TGFβ retention and bioavailability (Derynck et al., 2021). Thus, one of the consequences of downregulation of TGFBR2 in patient lung tumors (Borczuk et al., 2005; Malkoski et al., 2012) may be increased TGFβ-mediated immune suppression in the TME. Interestingly, a recent examination of outcome data found that lung cancer patients with mutations in TGFBR2 responded more poorly to immune checkpoint inhibitors (Li et al., 2021).

Beyond investigating specific gene functions, Perturb-map also enabled us to examine how specific gene perturbations and associated phenotypes influenced neighboring tumor regions. This is a relatively underexplored area of tumor biology, but as more high-resolution studies report heterogeneity in the TME and associations with tumor genetics (Lomakin et al., 2021; Mitra et al., 2020), Perturb-map can provide a valuable means for causal studies to determine how particular genes influence local and distal regions of a tumor.

Limitations of the study

It is important to note that the size of the CRISPR libraries that can be used for Perturb-map is smaller than that of traditional CRISPR screens, especially those carried out in vitro, which can be as large as genome wide. This is not so much a limitation of the number of Pro-Codes available but more a constraint of the model systems. The number of distinct tumor lesions is unlikely to be more than 100s in a single mouse, which would make it difficult to evaluate 1000s of CRISPRs in parallel, since many CRISPRs will not be sampled. A tumor with highly heterogeneous clonality such as the 4T1 is more feasible for large CRISPR libraries but are not optimal for investigating extracellular gene functions for the reasons mentioned above. Even in models like 4T1, there may be stochastic bottle necks in seeding and growth that could affect genome-wide screens that may be underappreciated, and thus we believe that imaging analysis of clonality in any tumor model is a useful prerequisite for CRISPR screens.

STAR★METHODS

Detailed methods are provided in the online version of this paper and include the following:

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Brian D. Brown (brian.brown@mssm.edu).

Materials availability

The plasmids generated or used in this study have been deposited to Addgene. The memPC library is available as Kit # 1000000177 (https://www.addgene.org/kits/brown-pro-code/). The nPC library will also be available in 2022 (Plasmid # 178209-178283).

All other vector constructs used in the manuscript are available by request to the Lead Contact.

Data and code availability

The imaging datasets generated in this study are available from the corresponding author on request. Segmented image data, along with cell annotations and tumor boundaries, can be accessed at the BioImage Archive (www.ebi.ac.uk/bioimage-archive) under accession ID S-BIAD267. Visium spatial transcriptomics data is available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) webserver under accession ID GSE193460.

All original code used in the analysis of Perturb-map imaging data can be found at https://github.com/srose89/PERTURB-map. This includes debarcoding, tumor identification and immune composition analysis procedures as well as code to replicate Visium specific analyses.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECTS DETAILS

Mice

Female BALB/cJ (stock number 000651), male C57BL/6J (stock number 000664) and male Cas9 (stock number 027650) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. At the time of experimentation, mice were 8–12 weeks of age. All mice were hosted in a specific pathogen-free facility. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai reviewed and approved all animal protocols used in the present study.

Cell culture

293T cells (embryonic kidney; human) and KP cells (lung adenocarcinoma; C57BL/6 mice) were grown in IMDM with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (GIBCO), 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (GIBCO) and 2 mM L-Glutamin. The KP cells (KP1.9) were generated by the Zippelius lab (Wieckowski et al., 2015) by Adenovirus-Cre mediated induction of lung tumors in KrasLSL-G12D, p53fl/fl mice (DuPage et al., 2009). 4T1 cells (mammary carcinoma; BALB/c mice) were grown in RPMI with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (GIBCO), 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (GIBCO) and 2 mM L-Glutamin. Each passage, cells were washed with PBS, detached from the plate with 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (GIBCO) and replated. Cells were discarded after 12 passages. 293T and 4T1 were purchased from ATCC. KP cells stably expressing Cas9 (KP-Cas9) were engineered by transduction with Cas9 lentivirus as previously described (Wroblewska et al., 2018).

METHOD DETAILS

Vector construction

The nuclear Pro-Codes (nPC) vectors were cloned following the same structure as the NGFR Pro-Codes (Wroblewska et al., 2018). The NLS from hnRNPK (21-KRPAEDMEEEQAFKRSR-37) (Matunis et al., 1992) was fused to the 3’ end of the coding sequence for mCherry by PCR. The mCherry-NLS was cloned downstream of the EF1a promoter into a lentiviral vector that contained a U6 gRNA expression cassette. The linear epitope combination sequences were cloned at the 5’ end of the mCherry sequence using BamHI and SphI restriction sites. To clone gRNA sequences, Pro-Code vectors were digested with BbsI, purified using PCR purification kit (QIAGEN) and ligated with pairs of annealed oligo sequences as described previously (Wroblewska et al., 2018). gRNA sequences were obtained from the Brie CRISPR library (Doench et al., 2016). TOP10 competent cells were used for all subsequent plasmid preparations. All plasmids were purified using ZR Plasmid Miniprep Classic kit (Zymo Research) or EndoFree Plasmid Midi Kit (QIAGEN).

Pro-Code/CRISPR libraries

The following genes were targeted in the Pro-Code/CRISPR library used in Figures 2–4: Akt1, Akt2, B2m, Cd24a, Cd47, Cd63, Cd81, Cd9, Cxcl17, F8, Fas, Fzd1, Fzd6, Gprc5a, Ifnar, Ifngr2, Irf1, Irf8, Irf9, Jak1, Jak2, Mmp3, Pd-l1, Ptpn2, Smad7, Socs1, Stat1, Stat2, Tgfbr2, Tnfrsf10b, Tnfrsf12a, Tnfrsf1a, Tnfrsf1b, Tnfrsf9, Vegfa. For each targeted gene, 3 plasmids were generated, corresponding to 3 different gRNA cloned into the same Pro-Code backbone.

Lentiviral vector production and titration

Lentiviral vectors were produced as previously described in detail (Mullokandov et al., 2012). For Pro-Code/CRISPR libraries, lentiviral vectors production was arrayed in 6-well plates. 293T cells were seeded at 500,000 cells per well 24 hours before calcium phosphate transfection with third-generation VSV-pseudotyped packaging plasmids and the transfer plasmids. Each well received 3 transfer plasmids in equimolar amount, encoding 3 different gRNAs targeting the same gene and coupled to the same Pro-Code. Supernatants were collected 48 hours post-transfection, strained through a 0.22-μm PVDF disc filter and stored at −80°C.

Vector transduction

4T1 and KP cells were transduced as previously described (Wroblewska et al., 2018). Briefly, cells were seeded 24 hours prior to transduction at a density of 50,000 cells per well in 6-well plates and transduced with lentiviral vectors in the presence of 5 μg/ml polybrene (Millipore). When cells were transduced with a Pro-Code library, cells were transduced at a low MOI to ensure that a majority of cells received only one vector (< 10% Pro-Code positive cells). Alternatively, KP-Cas9 cells were transduced in array with each Pro-Code/CRISPR lentiviral vector mix (3 plasmids, each coding for a gRNA targeting the same gene) and transduced to achieve 60–70% Pro-Code positive cells which were subsequently sorted to >99% purity (below).

Flow and mass cytometry

Adherent cells were detached with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA and resuspended in PBS. For analysis of transduction efficiency and sorting of Pro-Code-positive cells, cells were stained with anti-human CD271 PE or Alexa Fluor 647 (BD Biosciences) and flow sorted on NGFR or mCherry. KP-Cas9 cells transduced with Pro-Code/CRISPR lentiviral vectors and used in Figures 2–4 were sorted into the same tube (1×104 cells/Pro-Code).

Processing and analysis of cell suspension by CyTOF was performed as described previously (Wroblewska et al., 2018). Briefly, cell suspensions were stained for viability with Cell-ID Intercalator-103 Rh for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were subsequently stained for surface markers in flow buffer supplemented with anti-mouse CD16/CD32 antibody (eBioscience) for 30 min on ice. Next, cells were fixed and permeabilized using either BD Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences) or the eBiosciences Intracellular Fixation & Permeabilization kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and stained with epitope-tag specific antibodies for 30 min on ice. Cells were then washed and incubated in 125 nM Ir intercalator (Fluidigm) diluted in PBS containing 2.4% formaldehyde for 30 min at RT, washed and stored in PBS at 4°C until acquisition. The samples were acquired on either a CyTOF2 or Helios (both Fluidigm) at an event rate of < 500 events/second. The following antibodies were used for CyTOF staining: anti-HA tag-147Sm (clone 6E2, Cell Signaling), anti-V5 tag-152 Sm (Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-DYKDDDDK (FLAG) tag-175Lu (Clone L5, Biolegend), anti-VSVg tag-158 Gd (rabbit pAb, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-E tag-154Sm (clone 10B11, Abcam), anti-NWSHPQFEK (NWS) tag-159Tb (clone 5A9F9, Genscript), anti-AU1-162Dy (clone AU1, BioLegend), anti-AU5-169Tm (clone AU5, BioLegend), anti-Ollas tag-153Eu (clone L2, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-HSV tag-172Yb (rabbit polyclonal, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-S tag-165Ho (clone SBSTAGa, Abcam), anti-Protein C tag-171Yb (clone HPC4, Genscript), anti-mCherry-142Nd (Abcam), anti-mouse CD274-151Eu (clone MIH5, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-mouse CD47-168Er (clone miap301, BioLegend), anti-mouse CD24-141Pr (clone M1/69, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Antibodies were purchased purified and conjugated in-house using MaxPar X8 Polymer Kits (Fluidigm) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

TGFβ signaling was quantified by measuring phosphorylation of Smad2/3. Cells were incubated with 20 ng/ml of TGFβ (Peprotech) for 16 hours, incubated with LIVE/DEAD Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain Dye (Invitrogen) for 10 min on ice and fixed in 1.5% PFA for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were spun down and permeabilized with ice-cold methanol on ice for 10 min, then stained with an anti-Smad2(pS465/pS467)/Smad3(pS423/pS425) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 (Clone O72-670, BD Biosciences) for 30 min at room temperature.

Tumor models

4T1 murine mammary gland carcinoma cells were injected (5×104 cells) in the mammary fat pad of 8–12 week old BALB/c WT mice. Mice were sacrificed 12 days post-inoculation and the primary tumor was excised. Alternatively, mice were sacrificed after 28 days and the lungs were collected. KP cells were injected (1×106 cells) intravenously (i.v.) in the tail vein of C57BL/6 mice or Cas9 mice (to avoid immune rejection of Cas9 expressing KP cells). Mice were sacrificed 28 days later, and the lungs were collected. All the collected samples were either fresh-frozen in OCT or fixed overnight in PLP buffer (0.075 M lysine, 0.37 M sodium phosphate, 2% formaldehyde and 0.01 M NaIO4, at pH 7.2) and paraffin-embedded.

Pathological assessment of tumor lesions

Paraffin-embedded lung sections were stained with hematoxylin/eosin and scanned using a Aperio AT2 slide scanner (Leica). The gRNA present in each tumor lesion was identified based on the Pro-Code expression. Each tumor lesion was delimited in QuPath and evaluated by a pathologist (blinded to the tumor identification). The assessed criteria were tumor location, degree of differentiation and stromal composition. Specific patterns of tumor development were also characterized.

Imaging mass cytometry

Sections from fresh frozen tissue were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes on ice, blocked with 5% normal goat serum in TBS 2% Tween 20 (TBS-T) at RT for 15 min and incubated overnight at 4°C with metal-conjugated antibodies. Sections were then washed with TBS-T and fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde for 5 minutes. Following 3 washes in Tris buffer (pH 8.5) and deionized water, sections were dehydrated in ascending series of 50%, 75%, 95% and 100% ethanol for 1 minute each. Slides were then dried at RT and stored into a vacuum chamber until acquisition. The following antibodies were used: anti-HA tag-147Sm (clone 6E2, Cell Signaling), anti-V5 tag-152 Sm (Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-DYKDDDDK (FLAG) tag-175Lu (Clone L5, Biolegend), anti-VSVg tag-158 Gd (rabbit pAb, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-E tag-154Sm (clone 10B11, Abcam), anti-NWSHPQFEK (NWS) tag-159Tb (clone 5A9F9, Genscript), anti-AU1-162Dy (clone AU1, BioLegend), anti-AU5-169Tm (clone AU5, BioLegend), anti-Ollas tag-153Eu (clone L2, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-HSV tag-172Yb (rabbit polyclonal, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-S tag-165Ho (clone SBSTAGa, Abcam), anti-Protein C tag-171Yb (clone HPC4, Genscript), anti-mCherry-142Nd (Abcam). Samples were acquired with the Hyperion Imaging System (Fluidigm) or a MIBIscope System (Ionpath). Data related to Figure 1 (and associated supplementary figures) was acquired on a MIBIscope system (Ionpath). Tissue sections were cut onto a gold-plated slide (Ionpath). Fields of view of 500 um2 were acquired using the optimal resolution setting with a 1024 × 1024 pixel image resulting in a 488 nm resolution. The ion beam dwell time for each field of view was 3 ms per pixel with 4 repeat scans for a total dwell time of 12 ms per pixel. Images were then processed using the IONpath MIBI/O software to generate TIFF images which were further cleaned for isobaric correction and filtered to substract background noise signal. Images related to Figure 5 (and associated supplementary figure) were acquired on the Hyperion Imaging System (Fluidigm). Region of interests for laser ablation were selected based on the location of Pro-Code positive tumors identified on a serial section by spatial transcriptomics (Visium, 10× Genomics). All ablations were performed with a laser frequency of 200 Hz. The raw MCD files were exported for analysis on the MCD Viewer Software (Fluidigm).

Multiplexed immunohistochemical consecutive staining on single slide (MICSSS)

Iterative cycles of immunostaining on 4-mm thick FFPE tissue sections were performed as described previously in detail (Akturk et al., 2020). Briefly, slides were baked overnight at 60°C, then de-paraffinized in xylene and rehydrated in descending series of 100%, 90%, 70% and 50% ethanol. Slides were incubated at 95°C for 30 minutes in Antigen Retrieval Solution (pH 9) (Dako), cooled down at RT and rinsed in TBS. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by a 15-minute incubation in 3% H2O2. Slides were incubated in Protein Block Serum-Free (Agilent) for 30 minutes at RT, then incubated with the primary antibody diluted in Background reducing Antibody Diluent (Agilent). The primary antibody solution was washed by incubating the slides in TBS 0.04% Tween 20 and the sections were incubated with the HRP conjugated secondary antibody for 30 minutes at RT. Antigen detection was performed using the AEC Peroxidase Substrate Kit (Vector laboratories), and slides were counterstained with the Hematoxylin Solution, Harris Modified (Sigma-Aldrich). The slides were then mounted in Glycergel Mounting Media (Agilent) and imaged on a Aperio AT2 slide scanner (Leica), at a 20X magnification. To perform the subsequent staining, the coverslip was removed from the slide by incubating the slides in 60°C water, and AEC and Hematoxylin were washed away in ascending series of 50%, 70% (with 1% HCl 12N) and 100% ethanol. Sections were then re-hydrated. From that point, the staining progresses as described previously, with a shortened antigen retrieval step (10 minutes at 95°C). If two primary antibodies used consecutively were raised in the same species, an extra blocking step is performed with AffiniPure Fab Fragment Donkey anti-mouse IgG, anti-rabbit IgG or anti-rat IgG (Jackson Immuno Research), depending on the species. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-CD11b (clone EPR1344, Abcam), anti-CD4 (clone EPR19514, Abcam), anti-CD11c (clone D1V9Y, Cell Signaling), anti-CD8a (clone 4SM15, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-EpCAM (clone EPR20533-266, Abcam), anti-B220 (clone RA3-6B2, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-F4/80 (clone D2S9R, Cell Signaling), anti-AU1 tag (clone AU1, BioLegend), anti-AU5 tag (clone AU5, BioLegend), anti-Protein C tag (clone HPC4, Genscript), anti-E tag (rabbit pAb, Abcam), anti-DYKDDDDK (FLAG) tag (clone L5, BioLegend), anti-HA tag (clone 6E2, Cell Signaling), anti-HSV tag (rabbit pAb, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-NWSHPQFEK (NWS) tag (clone 5A9F9, Genscript), anti-Ollas tag (clone L2, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-S tag (clone D2K2V, Cell Signaling), anti-V5 tag (clone R960-25, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-VSVg tag (rabbit pAb, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The following secondary antibodies were used: EnVision+ System-HRP Labelled Polymer Anti-mouse (Agilent), EnVision+ System-HRP Labelled Polymer Anti-rabbit (Agilent), ImmPRESS HRP anti-rat IgG, Mouse adsorbed (Peroxidase) Polymer Detection Kit (vector Laboratories).

Spatial transcriptomics

Fresh frozen samples embedded in OCT were cryosectioned and 10 μm-thick sections were placed on the Visium Tissue Optimization Slides and Visium Spatial Gene Expression Slides (10× Genomics). Tissue sections were fixed in methanol and processed using the Visium Spatial Gene Expression Kit (10× Genomics), following manufacturer’s instructions. Based on the tissue optimization time course experiment, the lung tissue sections were permeabilized for 6 minutes to maximize RNA recovery. A serial section was used for Hyperion detection of the Pro-Code epitopes (see above).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Visualization and analysis of CyTOF data

CyTOF data was analyzed as described previously in detail (Wroblewska et al., 2018). Briefly, manual gating was performed on Cytobank (Kotecha et al., 2010) and Pro-Code positive cells (based on NGFR or mCherry expression) were debarcoded using Single Cell Debarcoder (Zunder et al., 2015). To visualize debarcoding, marker intensity heatmaps were generated by taking the median of arcsine transformed intensity values, first divided by a scaling factor of 5, for each epitope tag in each debarcoded population. Transformed intensity values for each epitope tag were then rescaled from 0 to 1.

Image processing and visualization

MICSSS data was registered and segmented using ImageJ and QuPath, following a detailed protocol described previously (Akturk et al., 2020). Briefly, consecutive images were aligned using ImageJ registration tool (Linear Stack Alignment with SIFT). Alternatively, image registration was performed using a custom analysis pipeline (Chen et al, manuscript in revision). Briefly, the raw red-green-blue (RGB) 1.25× resolution image was used to generate a tissue mask. The images across all markers were then rigidly registered using the SimpleElastix package for Python. Finally, the high resolution images (20×) were spliced into 2 mm2 tiles. Each set of tiles was deconvoluted to extract the hematoxylin channel, which was then registered with an affine registration (accounting for shear, scale, rotation and translational dislocation) and a bspline elastic warping (accounting for any local tissue warping or tissue damage). The vector field transformation matrix was then applied to the RGB tiles, which were concatenated to produce one final registered RGF image per marker. For each image, the signal associated with hematoxylin and the marker staining were deconvoluted in ImageJ, using the default Hematoxylin/AEC color vector. The resulting hematoxylin images from each staining were aligned to verify registration accuracy. Then, up to 10 AEC images (each corresponding to one stain) and 1 hematoxylin image were stacked, pseudocolored and overlayed to visualize the combinatorial expression of each marker.

Cell segmentation was performed in QuPath (v. 0.2.3) on the overlayed images. Nuclear cell segmentation identified nuclei based on the hematoxylin stain, with parameters optimized for each tissue. The same segmentation parameters were used for all images of the same experiment. The cell boundaries were extrapolated by expanding the nucleus boundaries by 3 pixels (approximately 1.5 μm) in all directions. The resulting segmentation data was exported and analyzed in R and python.

Pro-Code debarcoding

Pro-Codes were assigned to cells using an algorithm adapted from Zunder et al. (Zunder et al., 2015) diagrammed in Figure S6A. The mean pixel intensity for each epitope tag in nuclear regions of each segmented cell was rescaled from 0 to 1 within each tissue section. Next, epitope tags were sorted in order of normalized intensity for each cell and the difference between the 3rd and 4th most intense tags was calculated, deemed the delta value. Segmented cells were then assigned a Pro-Code corresponding to the three highest intensity tags if their delta value was greater than 0.2. Pro-Code assignments were then referenced against the vector library design to assign gRNA target genes and remove any inconsistent Pro-Code combinations.

To benchmark the debarcoding and assess the rate of false positive assignments at 0.2 delta threshold, an experiment was performed with a library that encoded 31 of the same 35 Pro-Code/CRISPR vectors that were used in the Figures 3–5 experiment. The 4 vectors that were removed included Pro-Codes that spanned all 7 epitope tags. KP cells were transduced with the 31 Pro-Code/CRISPR library and injected i.v. into mice. We collected the lungs and performed imaging and analysis as described above. Across 4 sections of mouse lung from 2 separate mice a total of 9 out of 24,109 debarcoded cells were positive for one of the removed Pro-Codes. This equates to a false positivity rate of 0.037%, at a delta threshold of 0.2 (Figure S6B).

To assess the distribution of the delta value in relation to our debarcoding cutoff, we generated histograms of delta values across 40 tissue sections and 8,442,439 segmented cells that were stained for the Pro-Code epitopes. Common histogram patterns were observed across Pro-Codes, including a peak close to 0 followed by a dip and plateau pertaining to barcoded cells (Figure S6C). The positive cell plateau occurred close to our delta threshold of 0.2. To further validate our cutoff, we plotted the delta value for the epitope tag combinations corresponding to the 4 absent Pro-Codes in the experiment described in Figure S6B. The delta values of the cells with putative signal for these Pro-Codes was beneath the 0.2 cutoff, with very few cells above compared to a population within this library (HA.Ollas.S) (Figure S6D). These analyses supported the 0.2 delta cutoff used in our analysis.

Clonality assessment

For clonality and co-localization analyses, segmented cell coordinates for Pro-code positive cells were loaded into squidpy v1.0.0 (Palla et al., 2022). On each tissue section a k nearest-neighbors (kNN) graph was constructed using only Pro-Code positive cells with interactions defined by the 10 nearest neighbors of each cell at a maximum radius of 40 μm. Enrichment Z-scores of interactions between Pro-Code labeled populations on each tissue section were calculated using the nhood_enrichment function in squidpy. In this method, Z-scores are calculated as: (observed interactions − expected interactions) / interaction standard deviation. The expected interactions and standard deviation are derived from the mean and standard deviation of interactions between Pro-Code populations from 1,000 Pro-Code label swapping permutations on the constructed kNN graph for that tissue section. Only Pro-Code positive cells were permuted in our analysis to ease computational requirements and focus on clonal dynamics between Pro-Code positive cells.

Group degree centrality and average local clustering coefficient graph metrics were calculated for cells positive for each Pro-Code on each tissue section using the centrality_scores function in squidpy on the kNN graph mentioned previously. Graph metrics were only calculated for Pro-Codes with greater than 20 assigned cells on a tissue section. Group degree centrality was defined as the fraction of non-group neighbor cells out of all non-group cells on the graph. The average local clustering coefficient was calculated using only homotypic interactions and was defined as the average fraction of possible triangles that exist through each cell on the kNN graph in each Pro-Code population. Kernel densities for abundant Pro-Code populations in 4T1 primary tumors were estimated using the kde2d function from the MASS (Venables and Ripley, 2002) package in R that used a bivariate normal kernel with normal distribution approximation to determine bandwidth.

Clustering and tumor lesion definition

To sub-cluster Pro-Code marked KP cells into clonal lesions and remove stray outlier cells we used the density based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) (Hahsler et al., 2019) algorithm separately for each Pro-Code within each tissue section that was assigned to at least 10 cells. For DBSCAN, an epsilon neighborhood size of 200 μm and minimum number of cells in the epsilon region set to 10 were used. Boundaries were drawn around clonal lesions using alphahull, a derivative of the convex hull algorithm that allows for concave boundaries, using the ashape function of the alphahull package (Pateiro-López and Rodríoguez-Casal, 2010). The alpha value, a tuning parameter where the higher the value the closer approximation to the convex hull, was initialized at 80 for each clonal lesion and borders were drawn iteratively increasing this value by 10 if a closed loop was not formed. Defined lesions were then exported to QuPath and subjected to manual curation based on image inspection to ensure quality and remove spurious associations. Lesion size was calculated by the coordinate area of the resulting boundary polygons. Only tumors greater than 25,000 μm2 were kept for subsequent analysis. We performed edge comparisons between serial sections to gauge if individual sections were representative in size and space of the tumor. For each lung lobe analyzed, we imaged three serial sections (one for H&E, one for Pro-Codes+myeloid markers, and one for Pro-Codes+lymphoid markers). Of the 1,778 borders for curated lesions that closely aligned across myeloid and lymphoid serial sections, only 195 lesions had a greater than 50% size difference relative to the smaller of the boundaries (data not shown). This indicated representative and consistent tumor slices across sections which were not at a distal edge of the tumor.

Tumor immune cell composition