Keywords: human neurophysiology, interlimb reflexes, propriospinal, spinal cord, transcutaneous spinal stimulation

Abstract

The use of transcutaneous electrical spinal stimulation (TSS) to modulate sensorimotor networks after neurological insult has garnered much attention from both researchers and clinicians in recent years. Although many different stimulation paradigms have been reported, the interlimb effects of these neuromodulation techniques have been little studied. The effects of multisite TSS on interlimb sensorimotor function are of particular interest in the context of neurorehabilitation, as these networks have been shown to be important for functional recovery after neurological insult. The present study utilized a condition-test paradigm to investigate the effects of interenlargement TSS on spinal motor excitability in both cervical and lumbosacral motor pools. Additionally, comparison was made between the conditioning effects of lumbosacral and cervical TSS and peripheral stimulation of the fibular nerve and ulnar nerve, respectively. In 16/16 supine, relaxed participants, facilitation of spinally evoked motor responses (sEMRs) in arm muscles was seen in response to lumbosacral TSS or fibular nerve stimulation, whereas facilitation of sEMRs in leg muscles was seen in response to cervical TSS or ulnar nerve stimulation. The decreased latency between TSS- and peripheral nerve-evoked conditioning implicates interlimb networks in the observed facilitation of motor output. The results demonstrate the ability of multisite TSS to engage interlimb networks, resulting in the bidirectional influence of cervical and lumbosacral motor output. The engagement of interlimb networks via TSS of the cervical and lumbosacral enlargements represents a feasible method for engaging spinal sensorimotor networks in clinical populations with compromised motor function.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Bidirectional interlimb modulation of spinal motor excitability can be evoked by transcutaneous spinal stimulation over the cervical and lumbosacral enlargements. Multisite transcutaneous spinal stimulation engages spinal sensorimotor networks thought to be important in the recovery of function after spinal cord injury.

INTRODUCTION

Neuromodulation of sensorimotor networks within the cervical and lumbosacral spinal cord via epidural (ESS) or transcutaneous (TSS) electrical spinal stimulation has been shown to have both immediate and long-term effects on motor function after spinal cord injury (SCI) in humans. Specifically, spinal stimulation can enhance neuromuscular function below the level of chronic, motor complete SCI in a task-specific manner (1–6). These effects are complementary to physiological activation of afferents, interneurons, and projecting motor neurons, resulting in an augmentative effect on resultant motor output (1, 2, 7–9). Specifically, stimulation of the lumbosacral enlargement can enable standing and stepping, as well as volitional activation of otherwise paralyzed lower limb muscles (1, 6, 10–12). Similarly, TSS of the cervical enlargement has produced improvements in upper limb motor function in individuals with tetraplegia (13, 14). However, our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the immediate and training-induced functional improvements seen in response to spinal stimulation in humans is still limited.

Several well-known studies in animal models of SCI have demonstrated that after SCI neuroplasticity within ascending and descending pathways, including the reticulospinal and propriospinal networks, mediates the recovery of motor control in initially paralyzed muscles (15–20). Whether similar mechanisms underlie functional recovery after human SCI is unclear. Evaluation of supraspinal-spinal and intraspinal sensorimotor networks may aid in quantification of neuroplastic changes associated with improved motor performance. Clinical and functional assessments of residual sensorimotor pathways can be used to characterize the extent of residual motor function after SCI (21–23). Electrophysiological assessments may complement these methods, providing information on the functional state of spinal pathways after injury (24, 25).

Although there is much evidence that cervical and lumbosacral networks influence each other during the performance of motor tasks (26–29), the interplay between the cervical and lumbosacral networks during postural and locomotor tasks is not well understood. Although often overlooked, the incorporation of arm swing during locomotor training can promote improved leg muscle activation (30, 31). Similarly, arm and leg cycling has been shown to increase walking capacity compared with leg cycling alone in individuals with SCI (31). Interestingly, the presence of interlimb modulation of spinal motor output was found to be correlated with volitional movement ability in individuals with SCI (24). Although some evidence suggests that spinal stimulation of both cervical and lumbosacral networks can improve locomotor function (7), the nature of these interactions has not been investigated.

The present study was designed to investigate interenlargement modulation of spinal motor excitability in neurologically intact individuals at rest. We hypothesized that conditioning stimulation of the lumbosacral enlargement would modulate the amplitudes of spinally evoked motor responses (sEMRs) in the arms, whereas conditioning stimulation of the cervical enlargement would potentiate the amplitudes of sEMRs in the legs, via reciprocal spinal intersegmental pathways.

METHODS

Participants

Sixteen neurologically intact adult participants (8 females, 8 males; height: 168.9 10.3 cm, weight: 74.6 12.9 kg, age: 29.7 4.4 yr) were recruited to participate in this study. Written informed consent to the experimental procedures, which were approved by the Houston Methodist Research Institute institutional review board (Study ID: Pro00019565), was obtained from each participant.

Experimental Procedures and Data Acquisition

All experiments were performed with subjects in a fully relaxed, supine position. TSS was delivered to the skin over the cervical and lumbosacral spinal enlargements with a constant-current stimulator DS8R (Digitimer Ltd., United Kingdom). Stimulation was administered with conductive self-adhesive electrodes (PALS; Axelgaard Manufacturing Co. Ltd., United States). For cervical stimulation, the cathode (diameter: 5 cm) was placed at midline between the C5 and C6 spinous processes and the anode (size: 5 cm × 9 cm) was positioned on the anterior aspect of the neck (32, 33). For lumbosacral stimulation, the cathode was placed at midline between the T11 and T12 spinous processes and two oval anodes (size: 7.5 cm × 13 cm) were placed symmetrically with respect to the sagittal plane on the skin over the abdomen.

Trigno Avanti wireless surface electromyography (EMG) electrodes (Delsys Inc., United States; common-mode rejection ratio < 80 dB, size: 27 mm × 37 mm × 13 mm, input impedance: >1,015 Ω//0.2 pF) were placed longitudinally over the left and right vastus lateralis (VL), medial hamstring (MH), soleus (SOL), and tibialis anterior (TA) muscles. EMG signals were also recorded from the biceps (BIC) and triceps (TRIC) brachii, extensor carpi radialis (ECR), and flexor carpi ulnaris (FCR) of the nondominant arm and the BIC of the dominant arm. EMG data were amplified with a Trigno Avanti amplifier (Delsys Inc.; gain: 909; bandwidth: 20–450 Hz) and recorded at a sampling frequency of 2,000 Hz with a PowerLab data acquisition system (ADInstruments, Australia).

Determination of TSS parameters.

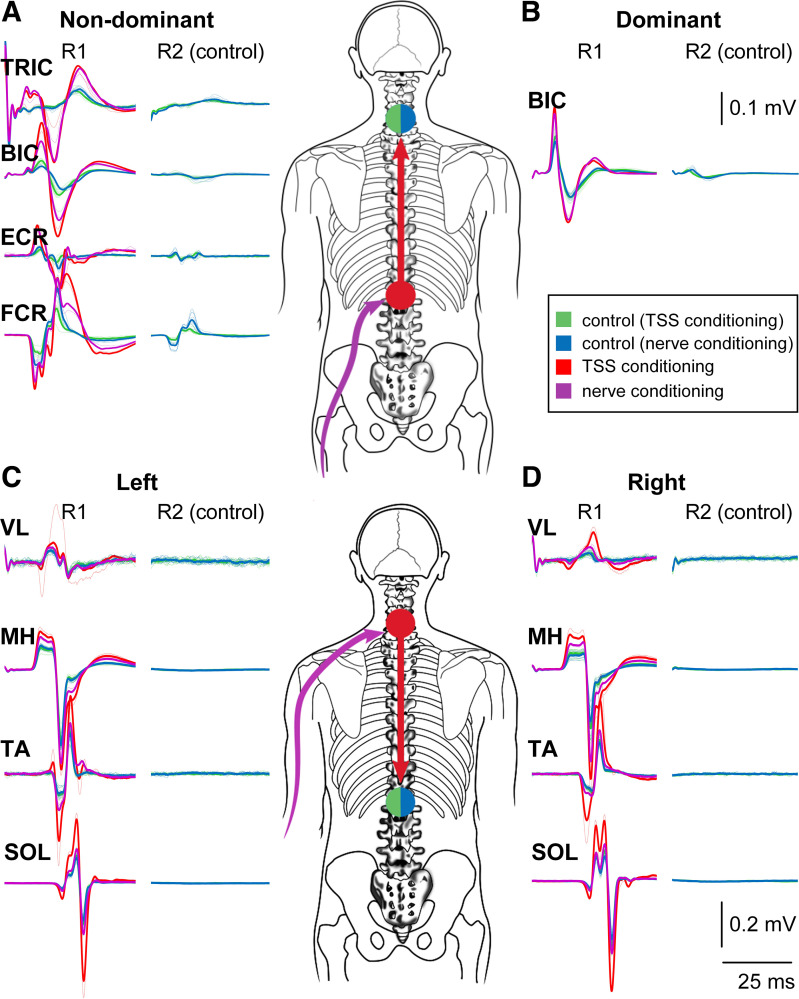

The control and conditioned sEMRs from a representative participant for both descending and ascending interlimb conditioning are shown in Fig. 1. To confirm that the stimulating electrode was optimally positioned over the tested enlargement and to identify stimulation intensities for subsequent conditioning experiments, the following procedure was performed for both cervical and lumbosacral TSS. Double-pulse stimulation consisting of two 1-ms square-wave pulses with interstimulus interval of 50 ms was delivered at a rate of one doublet every 6 s. Stimulation began at 30 mA and increased in a stepwise manner until sEMRs were observed in the muscles of interest. The location was then adjusted in a rostro-caudal direction as required to obtain sEMRs in proximal and distal limb muscles with the minimum difference in motor threshold stimulation intensity (24, 34, 35). The use of double-pulse TSS allowed confirmation of the reflex nature of the test sEMRs. Specifically, recordings were visually inspected for postactivation depression, i.e., a reduction in sEMR amplitude, which is expected in response to a second stimulation pulse delivered within ∼2,000 ms of the first pulse (36–38) [Fig. 1, R2 (control)]. This can distinguish sEMRs from a direct motor response, which results from direct activation of motor axons and thus is not susceptible to postactivation depression or other conditioning influences.

Figure 1.

Interlimb conditioning of arm and leg muscle spinally evoked motor responses (sEMRs). Top: ascending interlimb conditioning of arm muscle sEMRs [70 ms condition-test interval (CTI)] in a representative subject. A and B: the unconditioned (blue and green) and conditioned (red and purple) sEMRs recorded from nondominant (A) and dominant (B) arm muscles in response to lumbosacral transcutaneous spinal stimulation (TSS) or fibular nerve conditioning stimulation, respectively. Bottom: descending interlimb conditioning of leg muscle sEMRs (70 ms CTI) in the same subject. C and D: the unconditioned (blue and green) and conditioned (red and purple) sEMRs recorded from left (C) and right (D) leg muscles in response to cervical TSS or ulnar nerve conditioning stimulation, respectively. BIC, biceps brachii; ECR, extensor carpi radialis; FCR, flexor carpi ulnaris; MH, medial hamstrings; SOL, soleus; TA, tibialis anterior; TRIC, triceps brachii; VL, vastus lateralis.

Generation of sEMR recruitment curves.

Once the optimal stimulation location for both cervical and lumbosacral TSS was identified, sEMR recruitment curves were generated for each muscle studied with double-pulse TSS. For upper limb muscles, cervical TSS began at a subthreshold intensity, then was increased in 5-mA steps with three double pulses delivered at each intensity, and continued until the magnitudes of sEMRs in all muscles were observed to plateau or the maximum tolerated intensity was reached. The same procedure was followed for lumbosacral TSS to generate sEMR recruitment curves for the leg muscles. The recruitment curves were then used to identify stimulation intensities for conditioning experiments (24, 25). During the subsequent conditioning tests, cervical TSS intensities were selected such that the sEMR amplitudes in all arm muscles were between 40% and 70% of the maximum-amplitude sEMR whenever possible. This was done to ensure that both facilitation and inhibition of the sEMRs, should they be present, would be observable. This process was then repeated for the lumbosacral TSS and leg muscle sEMRs. Stimulation of multiple muscles via a single point of the spinal enlargement often leads to some variation in regard to each particular muscle’s threshold of activation. As such, there were instances when the responses occurred below 40% and above 70% in some muscles (24, 39) (Fig. 1, control responses).

Determination of peripheral nerve stimulation parameters.

Peripheral nerve stimulation was set up for the ulnar nerve just proximal to the elbow or the common peroneal nerve just posterior to the fibular head. Ulnar nerve stimulation was used to condition leg muscle sEMRs (descending experiments), whereas common peroneal nerve stimulation was used to condition arm muscle sEMRs (ascending experiments). In both cases, peripheral nerve stimulation was delivered via a bipolar stimulating electrode with a fixed interelectrode distance of 30 mm (MLADDF30; ADInstruments, Australia), using the DS8R stimulator. To determine motor threshold, stimulation was initially applied in single 1-ms square-wave pulses. Stimulation began at 1 mA and was increased in a stepwise manner until motor threshold was obtained, as confirmed by visible muscle contraction in the ulnar nerve distribution (the 5th digit flexion/abduction) or the common peroneal nerve distribution (ankle dorsiflexion).

Conditioning experiments.

Conditioning experiments were performed on both the leg and arm muscle sEMRs, the order of which was selected randomly for each participant. These experiments consisted of interenlargement conditioning experiments as well as peripheral nerve conditioning experiments.

For interenlargement conditioning experiments, the same stimulation intensities identified for evoking the test stimuli as described in Generation of sEMR recruitment curves were used for both ascending (Fig. 1, top) and descending (Fig. 1, bottom) experiments. Thus, the same stimulation intensity was used at a given enlargement whether the stimulus was the test or the conditioning stimuli. In each case, the test stimulation was applied to the enlargement being tested (i.e., cervical stimulation for ascending experiments and lumbosacral stimulation for descending experiments) and consisted of double-pulse TSS at a rate of one doublet every 6 s. Only responses from the first pulse were utilized for analysis of the conditioning effects. The conditioning stimulation was applied at the opposite enlargement, as a train consisting of three 1-ms square-wave pulses with interstimulus interval of 3 ms at a rate of one train every 6 s (24).

For peripheral nerve stimulation conditioning experiments, the same test stimulation was used at the lumbosacral and cervical enlargements as described above for the interenlargement conditioning experiments. Peripheral nerve stimulation intensity was set at motor threshold and was applied as a train consisting of three 1-ms square-wave pulses with interstimulus interval of 3 ms at a rate of one train every 6 s (24).

For each conditioning experiment, the first, middle, and last 10 stimulation pulses to the enlargement being tested were presented without conditioning and then used as control sEMRs to be compared with conditioned sEMRs. After recording of the unconditioned responses, conditioning stimuli were presented at the opposite enlargement, before the test stimulation at one of the following condition-test intervals (CTIs): 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 110 ms (24, 25). The CTIs were used in pseudorandom order until each CTI had been presented a total of 10 times. Thus, each conditioning experiment comprised a total of ∼130 test stimuli with ∼100 conditioning stimuli and lasted ∼13 min.

Data Processing and Analysis

With the software package LabChart (ADInstruments), EMG peak-to-peak amplitude was measured for each response and muscle within the time window of 10–50 ms following the first stimulation pulse. Then the amplitude was scaled using the participant’s maximum response found during the recruitment curve process for that muscle. The maximum response was determined by calculating the mean of the three largest responses.

Statistical analysis.

For each muscle where EMG data were recorded (13 muscles), two stimulation conditions were included (L1 or fibular stimulation for arm muscles and C4 or ulnar stimulation for leg muscles). Within each of the resulting 26 conditions, there were 10 CTIs (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 110 ms) (Table 1). The calculated value for each CTI was an average of 10 identical stimulations, unless outliers (exceeding 2.5 standard deviations from the mean) were excluded (total 2.7%). Data from each CTI were compared to the average of 10 unconditioned responses from the corresponding muscle and stimulation condition. For each comparison, we performed Wilcoxon signed-rank test. In Table 1, we report all the P values from all the paired comparisons that were performed. Bonferroni correction was used to protect against inflated risk of familywise type I error, resulting in a significance threshold of P ≤ 0.005 and a trend-level range of 0.005 < P ≤ 0.010 (based on 10 CTIs).

Table 1.

Summary of statistical analysis

| CTI, ms |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 110 | |

| L VL | ||||||||||

| C4 | 0.163 | 1.000 | 0.910 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| Ulnar | 0.109 | 0.470 | 0.925 | 0.730 | 0.730 | 0.041 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| R VL | ||||||||||

| C4 | 0.756 | 0.047 | 0.496 | 0.061 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| Ulnar | 0.470 | 0.470 | 0.433 | 0.272 | 0.638 | 0.272 | 0.008 | 0.056 | 0.006 | 0.009 |

| L MH | ||||||||||

| C4 | 0.148 | 0.027 | 0.955 | 0.691 | 0.011 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.007 |

| Ulnar | 0.158 | 0.638 | 0.638 | 0.433 | 0.510 | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| R MH | ||||||||||

| C4 | 0.134 | 0.047 | 0.955 | 0.363 | 0.134 | 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| Ulnar | 0.084 | 0.245 | 0.064 | 0.683 | 0.730 | 0.041 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.002 |

| L TA | ||||||||||

| C4 | 0.438 | 0.570 | 0.427 | 0.011 | 0.039 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.006 |

| Ulnar | 0.140 | 0.638 | 0.638 | 0.510 | 0.397 | 0.026 | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| R TA | ||||||||||

| C4 | 0.098 | 0.733 | 0.691 | 0.307 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Ulnar | 0.470 | 0.925 | 0.198 | 0.510 | 0.683 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.011 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| L SOL | ||||||||||

| C4 | 0.049 | 0.910 | 0.650 | 0.061 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.034 |

| Ulnar | 0.140 | 0.875 | 0.683 | 0.331 | 0.510 | 0.074 | 0.004 | 0.016 | 0.005 | 0.000 |

| R SOL | ||||||||||

| C4 | 0.918 | 0.363 | 0.650 | 0.173 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| Ulnar | 0.331 | 0.594 | 0.158 | 0.096 | 0.363 | 0.096 | 0.002 | 0.019 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| ND Biceps | ||||||||||

| L1 | 0.278 | 0.255 | 0.959 | 0.017 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| Fibular | 0.245 | 0.331 | 0.496 | 0.256 | 0.650 | 0.191 | 0.047 | 0.027 | 0.009 | 0.011 |

| ND Triceps | ||||||||||

| L1 | 0.004 | 0.438 | 0.379 | 0.569 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.003 |

| Fibular | 0.826 | 0.191 | 0.334 | 0.532 | 0.156 | 0.256 | 0.053 | 0.023 | 0.036 | 0.008 |

| ND ECR | ||||||||||

| L1 | 0.148 | 0.756 | 0.044 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Fibular | 0.917 | 0.609 | 0.865 | 0.776 | 0.650 | 0.078 | 0.027 | 0.015 | 0.031 | 0.005 |

| ND FCR | ||||||||||

| L1 | 0.196 | 0.148 | 0.836 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Fibular | 0.600 | 0.363 | 0.776 | 0.211 | 0.650 | 0.027 | 0.078 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.012 |

| D Biceps | ||||||||||

| L1 | 0.326 | 0.959 | 0.098 | 0.469 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.004 |

| Fibular | 0.152 | 0.233 | 0.009 | 0.363 | 0.910 | 0.125 | 0.460 | 0.041 | 0.053 | 0.027 |

CTI, condition-test interval, D, dominant; ECR, extensor carpi radialis; FCR, flexor carpi ulnaris; L, left; MH, medial hamstrings; ND, nondominant; R, right; SOL, soleus; TA, tibialis anterior; VL, vastus lateralis. Bold font indicates significance (P ≤ 0.005), and italicized font indicates trend-level range of 0.005 < P ≤ 0.010 (based on 10 CTIs).

RESULTS

In all muscles studied, facilitation of sEMR amplitudes was observed after conditioning stimulation of either the peripheral nerve or over the spinal cord. Figure 1 provides an example of the conditioning effect in a representative subject for both ascending (Fig. 1, top) and descending (Fig. 1, bottom) interlimb conditioning of sEMRs.

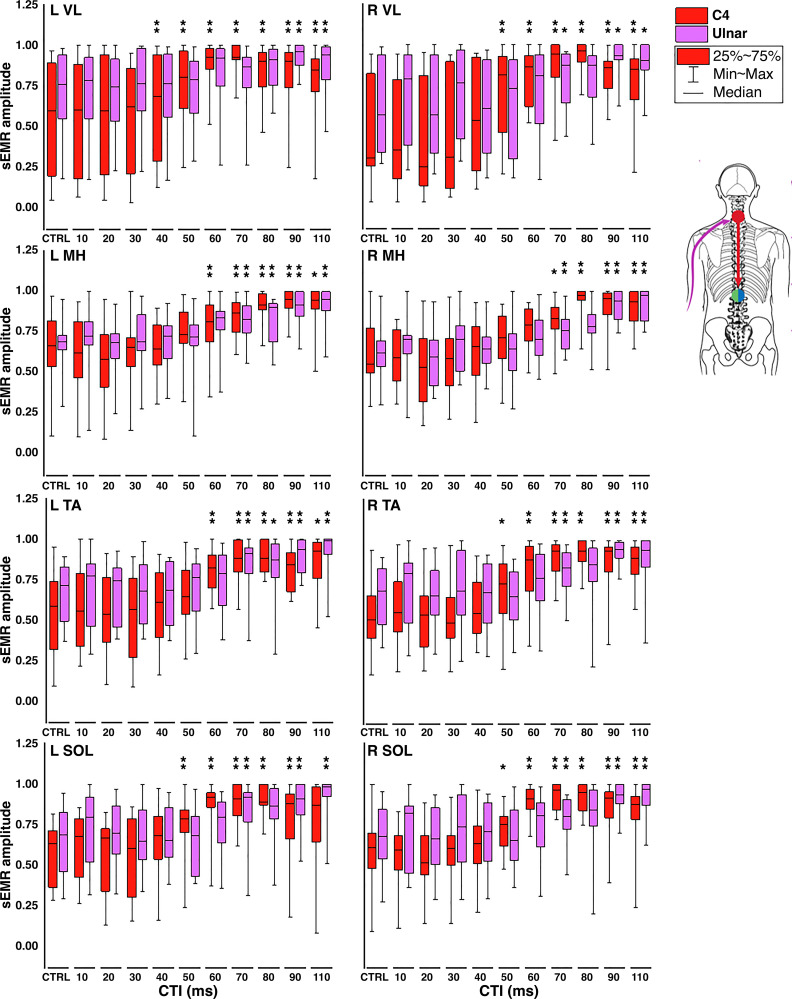

The facilitation of sEMRs in response to TSS (red bar graphs) or peripheral nerve stimulation (purple bar graphs) is shown in Figs. 2 and 3. In leg muscles, facilitation of sEMR amplitudes was observed in all muscles after conditioning stimulation of either the ulnar nerve or the cervical spinal cord. When the conditioning stimulus originated in the cervical spinal cord, facilitation of sEMRs for left VL, MH, TA, and SOL first reached statistical significance at 40, 60, 60, and 50 ms CTIs (P ≤ 0.005), respectively, whereas for right VL, MH, TA, and SOL significance was reached at the 50, 80, 60, and 60 ms CTIs (P ≤ 0.005), respectively (Fig. 2). When the conditioning stimulus originated at the ulnar nerve, facilitation of sEMRs was again observed in all muscles. For the left leg, significant facilitation was reached at the 90, 70, 70, and 70 ms CTIs in the VL, MH, TA, and SOL, respectively. In the right leg, significant facilitation was observed in the MH, TA, and SOL, beginning at the 70 ms CTI in each case. Facilitation in the right VL trended toward significance beginning at the 70 ms CTI (P = 0.008).In arm muscles, when the conditioning stimulus originated in the lumbosacral spinal cord, facilitation of sEMRs for nondominant BIC, ECR, FCR, and dominant BIC reached significance (P ≤ 0.005) at the 60, 40, 50, and 50 ms CTIs, respectively (Fig. 3). For nondominant TRI, significant facilitation was found at the 10 ms CTI and then seen again at the 50 ms CTI; although we have no physiological explanation for the former facilitation, the latter is consistent with the results in other muscles. When the conditioning stimulus originated at the fibular nerve, facilitation was again seen in all muscles; however, only facilitation in the nondominant ECR reached the level of significance, seen at the 110 ms CTI. Facilitation in nondominant BIC, TRI, FCR, and dominant BIC all approached statistical significance, at CTIs of 90, 110, 80, and 30 ms, respectively (P = 0.006–0.009).

Figure 2.

Facilitation of spinally evoked motor response (sEMR) amplitudes in leg muscles: grouped data (n = 16; 8 females, 8 males) detailing the magnitude of interlimb conditioning by muscle and condition-test interval (CTI; given in milliseconds) in response to cervical transcutaneous spinal stimulation (TSS) (red) or ulnar nerve conditioning stimulation (purple). The amplitude of the average peak-to-peak (PTP) amplitude for each control (CTRL) as well as each CTI was normalized to the maximum PTP amplitude (as defined in the text) obtained in the same muscle during collection of recruitment curves. Significant differences between sEMR amplitude at each CTI compared with control responses are indicated at top of bar graphs: *0.005 < P ≤ 0.010, **P ≤ 0.005. L, left; MH, medial hamstrings; R, right; SOL, soleus; TA, tibialis anterior; VL, vastus lateralis.

Figure 3.

Facilitation of spinally evoked motor response (sEMR) amplitudes in arm muscles: grouped data (n = 16; 8 females, 8 males) detailing the magnitude of interlimb conditioning by muscle and condition-test interval (CTI; given in milliseconds) in response to lumbosacral transcutaneous spinal stimulation (TSS) (red) or fibular nerve conditioning stimulation (purple). The amplitude of the average peak-to-peak (PTP) amplitude of control sEMRs (CTRL) as well as sEMRs recorded during each CTI was normalized to the maximum PTP amplitude (as defined in the text) obtained in the same muscle during collection of recruitment curves. Significant differences between the sEMR amplitude at each CTI compared with control responses are indicated at top of bar graphs: *0.005 < P ≤ 0.010, **P ≤ 0.005. BIC, biceps brachii; D, dominant; ECR, extensor carpi radialis; FCR, flexor carpi radialis; ND, nondominant; TRI, triceps brachii.

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated the interenlargement modulation of spinal motor excitability in response to conditioning stimuli delivered at the opposite spinal enlargement or peripheral nerve stimulation in neurologically intact individuals at rest. Both forms of conditioning stimulation resulted in multisegmental facilitation of sEMRs in both ascending (arm sEMR facilitation) and descending (leg sEMR facilitation) experiments. The similar nature, timing, and magnitude of the ascending and descending interenlargement modulation of motor excitability while descending influence was minimized suggests reciprocal interlimb connections.

Ascending and descending interlimb connections have previously been observed through analysis of stimulation-induced changes in ongoing EMG recorded from muscles of interest, as well as H-reflex conditioning and, more recently, sEMR conditioning methodologies. In ongoing EMG recordings of relaxed muscles during superficial peroneal nerve stimulation, interlimb reflexes were observed in only a fraction of participants (40, 41). However, similar studies have found that interlimb reflexes could be evoked in all noninjured participants when voluntary contraction was maintained during the conditioning stimulation (42–44). Recently, we have observed descending interlimb modulation of sEMRs in relaxed knee and ankle muscles bilaterally in all noninjured participants (24). The present study is the first to demonstrate the bidirectional modulation of sEMRs through stimulation at both spinal enlargements.

Although different methodologies make comparison of interlimb reflex studies difficult, there are some commonalities. For instance, all studies report interlimb effects beginning at a latency of 40–60 ms for both ascending and descending interlimb modulation. These latencies are consistent with the idea of an intraspinal network, as several studies have suggested that these latencies likely represent spinal reflex activity, whereas latencies around 110 ms probably include both spinal and supraspinal reflex pathways (43–46). Nielsen et al. (47) measured the time from stimulation of cutaneous afferents to the appearance of a somatosensory evoked potential (SSEP) and added to this the latency of a TMS-evoked motor evoked potential (MEP) in the TA muscle to determine the minimum necessary time for a transcortical relay to occur. Although they did not perform this calculation for upper to lower limb or lower to upper limb reflexes, for which different reflex mechanisms may be responsible, we can approximate the interlimb latency similarly based on published average values for SSEPs and MEPs. For example, peroneal nerve stimulation-evoked SSEP results in a latency of ∼32 ms. Once the conduction time from the site of stimulation to the T12 vertebra is subtracted, this results in an afferent conduction time of ∼19.4 ms (48). The average latency of an MEP recorded in FCR is ∼18 ms (49). If one includes a 10-ms central processing time as suggested by Nielsen et al. (47), this would result in a total conduction time for a transcortical reflex from the ankle to the FCR of ∼47 ms. In the present study, statistically significant facilitation of the FCR sEMR following conditioning stimulation (lumbar TSS) was first observed at the 40 ms CTI. It can be suggested that although the facilitation seen at longer CTIs in this and similar studies may involve supraspinal reflexes, these pathways alone may be insufficient to explain the short-latency interlimb pathways we observed. At the same time, because supraspinal loops do not necessarily include the cortex but could include shorter pathways as well (50), it is not possible to completely rule out supraspinally mediated effects.

In the present study, TSS and peripheral nerve stimulation both resulted in facilitation of sEMRs in all muscles, in both the ascending and descending experiments. However, the conditioning effects of TSS and peripheral nerve stimulation did differ with respect to the timing of the effects. The onset of sEMR facilitation during TSS occurred at earlier latencies compared with peripheral nerve stimulation in all muscles studied. For descending experiments, sEMR facilitation response to TSS was significant in all muscles by the 40–60 ms CTIs, whereas similar sEMR facilitation was evoked by the ulnar nerve by the 70 ms CTI (Fig. 2). For ascending experiments, TSS produced significant sEMR conditioning at CTIs of 40–50 ms, whereas fibular nerve stimulation produced essentially the same effect at CTIs of 60–80 ms (Fig. 3). This difference of 20–30 ms is likely attributable to the added conduction time from the periphery to the spinal cord that is required for peripheral nerve stimulation.

In considering both forms of stimulation, the use of TSS may be advantageous for multiple reasons. First, stimulation directly over the enlargement allows targeting of posterior nerve roots, such that direct motor responses, and the antidromic volleys they produce, can be avoided (51–54). Second, conditioning studies involving movement of the arms and/or legs present difficulty in maintaining a stable level of peripheral nerve stimulation, since the skin, muscle, and nerve are all moving underneath the stimulating electrode. Third, sEMRs can be evoked in muscles like the medial hamstrings (i.e., semimembranosus) whose peripheral innervation cannot be easily accessed. Finally, conditioning TSS at the midline of the spine would provide a compelling opportunity to compare the symmetry of the sEMR, which can be impacted by SCI or another neurological condition (24, 55).

Clinical Implications

Although propriospinal networks have been shown to mediate functional recovery in animal models of SCI (16–18), more recent studies suggest that they are important for motor function after human SCI as well. We previously observed descending interlimb modulation of leg sEMRs in individuals with SCI of all severities, with the notable exception of motor and sensory complete SCI in the thoracic segments. The presence and magnitude of interlimb facilitation was greatest in participants with the least severe injuries, suggesting that the function of interlimb networks may play an important role in motor function after SCI (24). Furthermore, others have shown that although interlimb networks can be disrupted by SCI they can also be retrained via arm and leg cycling, resulting in improved functional gait outcomes (56). This agrees with earlier studies showing that the inclusion of arm swing during gait improves performance in individuals with SCI (31). Interestingly, the addition of cervical and lumbar TSS to arm and leg cycling appears to increase corticospinal transmission to at least some limb muscles (57), suggesting that interlimb networks may be important to voluntary motor function seen during TSS in paralyzed muscles after SCI.

The use of combined cervical and lumbosacral TSS allowed observation of descending and ascending interlimb modulation of motor excitability in the absence of voluntary muscle activity, demonstrating the potential to assess interlimb pathways after SCI of all severities, as well as during other functional motor tasks. Although arm and leg cycling appear to be effective means of assessing interlimb coupling specifically, identifying interenlargement modulation in persons not able to actively cycle with the arms and legs would not be possible.

Improving our understanding of the presence and nature of residual and/or reorganized sensorimotor networks after neurological injury is requisite to elucidating the mechanisms underlying functional recovery in these individuals. Although such recovery almost certainly involves plasticity in supraspinal sensorimotor networks, the spinal motor pools represent the final common pathway in the production of movement, and thus provide a functionally relevant opportunity for assessing changes in descending or interlimb influence across time and/or in response to specific intervention.

The present study extends our previous work in examining interlimb modulation, providing a basis for evaluating both ascending and descending interenlargement modulation, even in individuals with complete paralysis. Removing the requirement for voluntary drive to the muscles of interest further simplifies interpretation of the results of such evaluations, and the use of TSS to evoke sEMRs multisegmentally allows for observation of interenlargement influence on the cervical and lumbosacral networks rather than an individual motor pool. Taken in the context of neurological injury, this study adds to the growing evidence in support of the idea that incorporation of upper limb movement and bidirectional engagement of interlimb pathways may be important in rehabilitation, as it represents a potential mechanism to modulate spinal sensorimotor network excitability in the absence of descending input from supraspinal centers.

Limitations

Although the methods described here were designed to allow inclusion of completely paralyzed participants, the supine and relaxed position does not allow direct functional assessment of interlimb coordination, as may be accomplished with cycling or stepping. As we were particularly interested in the short-latency responses reported in several recent studies (24, 40, 56, 57), no attempt was made to measure the whole interval of the observed effects—indeed, we recently observed that descending interlimb facilitation of sEMRs can occur at latencies as least as long as 250 ms (24). Additionally, we utilized a single stimulation location and intensity to interrogate multiple motor pools residing at different segmental levels, resulting in differing relative levels of activation across motor pools. Specifically, although we attempted to maintain test sEMRs at amplitudes between 40% and 70% of their maximum, we were not always able to achieve this, in particular in the upper limb muscle sEMRs (Figs. 2 and 3). In addition, although we checked for postactivation depression to confirm the reflex nature of the test sEMRs we conditioned (Fig. 1), it is likely that the peripheral nerve conditioning stimulation involved both motor and sensory nerve fibers. We choose the intensities for peripheral nerve conditioning on the basis of prior studies, to make comparison of the results more straightforward (24, 42, 50, 58, 59). Although TSS appears to have several advantages over H-reflex methodology in the examination of spinal pathways, both are limited in their clinical application because of the difficulty in approximation of the stimulating electrode and the target neural structure in larger individuals.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates the presence of reciprocal interenlargement modulation of cervical and lumbosacral network excitability and demonstrates the use of TSS to interrogate the multisegmental effects of these connections. These methods are suitable for individuals with severe neurological impairment, such as SCI, stroke, or multiple sclerosis, and may be useful both in evaluation of residual function and in the assessment of neuroplasticity underlying functional improvements seen in the presence of spinal stimulation and/or in response to rehabilitation. Understanding how these different conditions impact spinal sensorimotor network function is important for the continued development and refinement of multimodal neurorehabilitation strategies.

GRANTS

This work was in part supported by philanthropic funding from Paula and Rusty Walter and the Walter Oil & Gas Corporation. Sources of funding for the work reported here also include National Institutes of Health Grants R01 NS119587-01A and 1R01 NS102920-01A1, the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation (733278), and the Wings for Life Foundation (227).

DISCLOSURES

Y.P.G. holds a shareholder interest in NeuroRecovery Technologies and Cosyma. He holds certain inventorship rights on intellectual property licensed by the regents of the University of California to NeuroRecovery Technologies and its subsidiaries. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

DISCLAIMERS

The funders were not involved in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the experimental data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit this article for publication.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.A.A., Y.P.G., and D.G.S. conceived and designed research; D.A.A., A.G.S., G.A.M., and D.G.S. performed experiments; A.G.S., G.A.M., J.S., and J.O. analyzed data; D.A.A., J.S., J.O., and D.G.S. interpreted results of experiments; A.G.S., J.O., and D.G.S. prepared figures; D.A.A., A.G.S., J.S., and J.O. drafted manuscript; D.A.A., A.G.S., G.A.M., J.S., J.O., Y.P.G., and D.G.S. edited and revised manuscript; D.A.A., A.G.S., G.A.M., J.S., J.O., Y.P.G., and D.G.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angeli CA, Edgerton VR, Gerasimenko YP, Harkema SJ. Altering spinal cord excitability enables voluntary movements after chronic complete paralysis in humans. Brain 137: 1394–1409, 2014. [Erratum in Brain 138: e330, 2015]. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerasimenko Y, Gorodnichev R, Moshonkina T, Sayenko D, Gad P, Edgerton VR. Transcutaneous electrical spinal-cord stimulation in humans. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 58: 225–231, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill ML, Grahn PJ, Calvert JS, Linde MB, Lavrov IA, Strommen JA, Beck LA, Sayenko DG, Van Straaten MG, Drubach DI, Veith DD, Thoreson AR, Lopez C, Gerasimenko YP, Edgerton VR, Lee KH, Zhao KD. Neuromodulation of lumbosacral spinal networks enables independent stepping after complete paraplegia. Nat Med 24: 1677–1682, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grahn PJ, Lavrov IA, Sayenko DG, Van Straaten MG, Gill ML, Strommen JA, Calvert JS, Drubach DI, Beck LA, Linde MB, Thoreson AR, Lopez C, Mendez AA, Gad PN, Gerasimenko YP, Edgerton VR, Zhao KD, Lee KH. Enabling task-specific volitional motor functions via spinal cord neuromodulation in a human with paraplegia. Mayo Clin Proc 92: 544–554, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rath M, Vette AH, Ramasubramaniam S, Li K, Burdick J, Edgerton VR, Gerasimenko YP, Sayenko DG. Trunk stability enabled by noninvasive spinal electrical stimulation after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 35: 2540–2553, 2018. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sayenko DG, Rath M, Ferguson AR, Burdick JW, Havton LA, Edgerton VR, Gerasimenko YP. Self-assisted standing enabled by non-invasive spinal stimulation after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 36: 1435–1450, 2019. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.5956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerasimenko Y, Gad P, Sayenko D, McKinney Z, Gorodnichev R, Puhov A, Moshonkina T, Savochin A, Selionov V, Shigueva T, Tomilovskaya E, Kozlovskaya I, Edgerton VR. Integration of sensory, spinal, and volitional descending inputs in regulation of human locomotion. J Neurophysiol 116: 98–105, 2016. doi: 10.1152/jn.00146.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu DC, Edgerton VR, Modaber M, AuYong N, Morikawa E, Zdunowski S, Sarino ME, Sarrafzadeh M, Nuwer MR, Roy RR, Gerasimenko Y. Engaging cervical spinal cord networks to reenable volitional control of hand function in tetraplegic patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 30: 951–962, 2016. doi: 10.1177/1545968316644344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minassian K, Hofstoetter US, Danner SM, Mayr W, Bruce JA, McKay WB, Tansey KE. Spinal rhythm generation by step-induced feedback and transcutaneous posterior root stimulation in complete spinal cord-injured individuals. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 30: 233–243, 2016. doi: 10.1177/1545968315591706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerasimenko YP, Lu DC, Modaber M, Zdunowski S, Gad P, Sayenko DG, Morikawa E, Haakana P, Ferguson AR, Roy RR, Edgerton VR. Noninvasive reactivation of motor descending control after paralysis. J Neurotrauma 32: 1968–1980, 2015. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofstoetter US, Knikou M, Guertin PA, Minassian K. Probing the human spinal locomotor circuits by phasic step-induced feedback and by tonic electrical and pharmacological neuromodulation. Curr Pharm Des 23: 1805–1820, 2017. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666161214144655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rejc E, Angeli CA, Atkinson D, Harkema SJ. Motor recovery after activity-based training with spinal cord epidural stimulation in a chronic motor complete paraplegic. Sci Rep 7: 13476, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14003-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gad P, Lee S, Terrafranca N, Zhong H, Turner A, Gerasimenko Y, Edgerton VR. Noninvasive activation of cervical spinal networks after severe paralysis. J Neurotrauma 35: 2145–2158, 2018. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inanici F, Samejima S, Gad P, Edgerton VR, Hofstetter CP, Moritz CT. Transcutaneous electrical spinal stimulation promotes long-term recovery of upper extremity function in chronic tetraplegia. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 26: 1272–1278, 2018. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2018.2834339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asboth L, Friedli L, Beauparlant J, Martinez-Gonzalez C, Anil S, Rey E, Baud L, Pidpruzhnykova G, Anderson MA, Shkorbatova P, Batti L, Pagès S, Kreider J, Schneider BL, Barraud Q, Courtine G. Cortico-reticulo-spinal circuit reorganization enables functional recovery after severe spinal cord contusion. Nat Neurosci 21: 576–588, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bareyre FM, Kerschensteiner M, Raineteau O, Mettenleiter TC, Weinmann O, Schwab ME. The injured spinal cord spontaneously forms a new intraspinal circuit in adult rats. Nat Neurosci 7: 269–277, 2004. doi: 10.1038/nn1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Courtine G, Song B, Roy RR, Zhong H, Herrmann JE, Ao Y, Qi J, Edgerton VR, Sofroniew MV. Recovery of supraspinal control of stepping via indirect propriospinal relay connections after spinal cord injury. Nat Med 14: 69–74, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nm1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Filli L, Engmann AK, Zörner B, Weinmann O, Moraitis T, Gullo M, Kasper H, Schneider R, Schwab ME. Bridging the gap: a reticulo-propriospinal detour bypassing an incomplete spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 34: 13399–13410, 2014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0701-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harkema S, Gerasimenko Y, Hodes J, Burdick J, Angeli C, Chen Y, Ferreira C, Willhite A, Rejc E, Grossman RG, Edgerton VR. Effect of epidural stimulation of the lumbosacral spinal cord on voluntary movement, standing, and assisted stepping after motor complete paraplegia: a case study. Lancet 377: 1938–1947, 2011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60547-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van den Brand R, Heutschi J, Barraud Q, DiGiovanna J, Bartholdi K, Huerlimann M, Friedli L, Vollenweider I, Moraud EM, Duis S, Dominici N, Micera S, Musienko P, Courtine G. Restoring voluntary control of locomotion after paralyzing spinal cord injury. Science 336: 1182–1185, 2012. doi: 10.1126/science.1217416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimitrijevic MR, Dimitrijevic MM, Faganel J, Sherwood AM. Suprasegmentally induced motor unit activity in paralyzed muscles of patients with established spinal cord injury. Ann Neurol 16: 216–221, 1984. doi: 10.1002/ana.410160208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimitrijevic MR, Hsu CY, McKay WB. Neurophysiological assessment of spinal cord and head injury. J Neurotrauma 9, Suppl 1: S293–S300, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li K, Atkinson D, Boakye M, Tolfo CZ, Aslan S, Green M, McKay B, Ovechkin A, Harkema SJ. Quantitative and sensitive assessment of neurophysiological status after human spinal cord injury. J Neurosurg Spine 17: 77–86, 2012. doi: 10.3171/2012.6.AOSPINE12117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atkinson DA, Sayenko DG, D’Amico JM, Mink A, Lorenz DJ, Gerasimenko YP, Harkema S. Interlimb conditioning of lumbosacral spinally evoked motor responses after spinal cord injury. Clin Neurophysiol 131: 1519–1532, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sayenko DG, Atkinson DA, Mink AM, Gurley KM, Edgerton VR, Harkema SJ, Gerasimenko YP. Vestibulospinal and corticospinal modulation of lumbosacral network excitability in human subjects. Front Physiol 9: 1746, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dietz V, Michel J. Human bipeds use quadrupedal coordination during locomotion. Ann NY Acad Sci 1164: 97–103, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerasimenko Y, Sayenko D, Gad P, Liu CT, Tillakaratne NJ, Roy RR, Kozlovskaya I, Edgerton VR. Feed-forwardness of spinal networks in posture and locomotion. Neuroscientist 23: 441–453, 2017. doi: 10.1177/1073858416683681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zehr EP, Balter JE, Ferris DP, Hundza SR, Loadman PM, Stoloff RH. Neural regulation of rhythmic arm and leg movement is conserved across human locomotor tasks. J Physiol 582: 209–227, 2007. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.133843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zehr EP, Barss TS, Dragert K, Frigon A, Vasudevan EV, Haridas C, Hundza S, Kaupp C, Klarner T, Klimstra M, Komiyama T, Loadman PM, Mezzarane RA, Nakajima T, Pearcey GE, Sun Y. Neuromechanical interactions between the limbs during human locomotion: an evolutionary perspective with translation to rehabilitation. Exp Brain Res 234: 3059–3081, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00221-016-4715-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyns P, Bruijn SM, Duysens J. The how and why of arm swing during human walking. Gait Posture 38: 555–562, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tester NJ, Howland DR, Day KV, Suter SP, Cantrell A, Behrman AL. Device use, locomotor training and the presence of arm swing during treadmill walking after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 49: 451–456, 2011. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Freitas RM, Sasaki A, Sayenko DG, Masugi Y, Nomura T, Nakazawa K, Milosevic M. Selectivity and excitability of upper-limb muscle activation during cervical transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 131: 746–759, 2021. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00132.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milosevic M, Masugi Y, Sasaki A, Sayenko DG, Nakazawa K. On the reflex mechanisms of cervical transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation in human subjects. J Neurophysiol 121: 1672–1679, 2019. doi: 10.1152/jn.00802.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sayenko DG, Atkinson DA, Floyd TC, Gorodnichev RM, Moshonkina TR, Harkema SJ, Edgerton VR, Gerasimenko YP. Effects of paired transcutaneous electrical stimulation delivered at single and dual sites over lumbosacral spinal cord. Neurosci Lett 609: 229–234, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steele AG, Atkinson DA, Varghese B, Oh J, Markley RL, Sayenko DG. Characterization of spinal sensorimotor network using transcutaneous spinal stimulation during voluntary movement preparation and performance. J Clin Med 10: 5958, 2021. doi: 10.3390/jcm10245958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrews JC, Stein RB, Roy FD. Post-activation depression in the human soleus muscle using peripheral nerve and transcutaneous spinal stimulation. Neurosci Lett 589: 144–149, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofstoetter US, Freundl B, Binder H, Minassian K. Recovery cycles of posterior root-muscle reflexes evoked by transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation and of the H reflex in individuals with intact and injured spinal cord. PloS One 14: e0227057, 2019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roy FD, Gibson G, Stein RB. Effect of percutaneous stimulation at different spinal levels on the activation of sensory and motor roots. Exp Brain Res 223: 281–289, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s00221-012-3258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sayenko DG, Atkinson DA, Dy CJ, Gurley KM, Smith VL, Angeli C, Harkema SJ, Edgerton VR, Gerasimenko YP. Spinal segment-specific transcutaneous stimulation differentially shapes activation pattern among motor pools in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 118: 1364–1374, 2015. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01128.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Butler JE, Godfrey S, Thomas CK. Interlimb reflexes induced by electrical stimulation of cutaneous nerves after spinal cord injury. PloS One 11: e0153063, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calancie B, Lutton S, Broton JG. Central nervous system plasticity after spinal cord injury in man: interlimb reflexes and the influence of cutaneous stimulation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 101: 304–315, 1996. doi: 10.1016/0924-980x(96)95194-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alaid S, Emmer A, Kornhuber ME. Habituation of the interlimb reflex (ILR) over the biceps brachii muscle after electrical stimuli over the sural nerve. Front Neurosci 13: 1130, 2019. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frigon A, Collins DF, Zehr EP. Effect of rhythmic arm movement on reflexes in the legs: modulation of soleus H-reflexes and somatosensory conditioning. J Neurophysiol 91: 1516–1523, 2004. doi: 10.1152/jn.00695.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zehr EP, Collins DF, Chua R. Human interlimb reflexes evoked by electrical stimulation of cutaneous nerves innervating the hand and foot. Exp Brain Res 140: 495–504, 2001. doi: 10.1007/s002210100857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calancie B, Molano MR, Broton JG. Interlimb reflexes and synaptic plasticity become evident months after human spinal cord injury. Brain 125: 1150–1161, 2002. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Christensen LO, Petersen N, Andersen JB, Sinkjaer T, Nielsen JB. Evidence for transcortical reflex pathways in the lower limb of man. Prog Neurobiol 62: 251–272, 2000. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nielsen J, Petersen N, Fedirchuk B. Evidence suggesting a transcortical pathway from cutaneous foot afferents to tibialis anterior motoneurones in man. J Physiol 501: 473–484, 1997. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.473bn.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Misulis KE, Head TC. Essentials of Clinical Neurophysiology. New York: Garland Science, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sollmann N, Bulubas L, Tanigawa N, Zimmer C, Meyer B, Krieg SM. The variability of motor evoked potential latencies in neurosurgical motor mapping by preoperative navigated transcranial magnetic stimulation. BMC Neurosci 18: 5–15, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12868-016-0321-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Delwaide PJ, Schepens B. Auditory startle (audio-spinal) reaction in normal man: EMG responses and H reflex changes in antagonistic lower limb muscles. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 97: 416–423, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0924-980X(95)00136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Courtine G, Harkema SJ, Dy CJ, Gerasimenko YP, Dyhre-Poulsen P. Modulation of multisegmental monosynaptic responses in a variety of leg muscles during walking and running in humans. J Physiol 582: 1125–1139, 2007. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.128447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Danner SM, Hofstoetter US, Ladenbauer J, Rattay F, Minassian K. Can the human lumbar posterior columns be stimulated by transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation? A modeling study. Artif Organs 35: 257–262, 2011. [Erratum in Artif Organs 35: 556, 2011]. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2011.01213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ladenbauer J, Minassian K, Hofstoetter US, Dimitrijevic MR, Rattay F. Stimulation of the human lumbar spinal cord with implanted and surface electrodes: a computer simulation study. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 18: 637–645, 2010. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2010.2054112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Minassian K, Persy I, Rattay F, Dimitrijevic MR, Hofer C, Kern H. Posterior root-muscle reflexes elicited by transcutaneous stimulation of the human lumbosacral cord. Muscle Nerve 35: 327–336, 2007. doi: 10.1002/mus.20700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sayenko DG, Atkinson DA, Dy CJ, Gurley KM, Smith VL, Angeli C, Harkema SJ, Edgerton VR, Gerasimenko YP. Spinal segment-specific transcutaneous stimulation differentially shapes activation pattern among motor pools in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 118: 1364–1374, 2015. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01128.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou R, Parhizi B, Assh J, Alvarado L, Ogilvie R, Chong SL, Mushahwar VK. Effect of cervicolumbar coupling on spinal reflexes during cycling after incomplete spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol 120: 3172–3186, 2018. doi: 10.1152/jn.00509.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parhizi B, Barss TS, Mushahwar VK. Simultaneous cervical and lumbar spinal cord stimulation induces facilitation of both spinal and corticospinal circuitry in humans. Front Neurosci 15: 615103, 2021. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.615103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kagamihara Y, Hayashi A, Masakado Y, Kouno Y. Long-loop reflex from arm afferents to remote muscles in normal man. Exp Brain Res 151: 136–144, 2003. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1436-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meinck HM, Piesiur-Strehlow B. Reflexes evoked in leg muscles from arm afferents: a propriospinal pathway in man? Exp Brain Res 43: 78–86, 1981. doi: 10.1007/BF00238812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]