Abstract

Background

Light chain (AL) amyloidosis is a plasma cell neoplasm associated with high early mortality and severe morbidity that can cause severe disability. We explored the impact of AL amyloidosis on symptoms and well-being from the perspectives of patients and health care providers who regularly care for AL patients. We intended to develop a conceptual understanding of patient-reported outcomes in AL amyloidosis to identify the context of use and concept of interest for a clinical outcome assessments tool in this disease.

Method

Twenty patients and ten professionals were interviewed. Patient interviews captured the spectrum of amyloidosis experience including time from diagnosis, type of organ involvement, and presence and type of treatment received. Interviews with professionals included physicians, advanced practice providers, registered nurse, and a patient advocate; these interviews covered similar topics.

Results

The impact of AL amyloidosis on patients’ life was multidimensional, with highly subjective perceptions of normality and meaning. Four major themes from patients and experts included diagnosis of AL amyloidosis, living with AL amyloidosis, symptom burden, and social roles. Barriers to patient-reported outcomes data collection in patients were additionally explored from experts. The themes provide a comprehensive understanding of the important experiences of symptom burden and its impact on daily life from AL amyloidosis patients’ and from the perspectives of professionals who care for patients with AL amyloidosis.

Conclusion

These findings further the conceptual understanding and identification of a preliminary model of concept of interest for development of a clinical outcome assessments tool for AL amyloidosis.

Keywords: Conceptual model, AL amyloidosis, Quality of life qualitative, Patient-reported

Introduction

Patients with light chain (AL) amyloidosis can have high symptom burden, both at the time of diagnosis as well as after surviving the initial year after diagnosis [1]. This is a rare and complex disease secondary to a plasma cell neoplasm in which patients can have multi-system organ dysfunction from insoluble fibril deposition leading to high morbidity [2]. The fibrils are derived from immunoglobulin free light chains made by the clonal plasma cells. Patients with AL amyloidosis often experience long delays in diagnosis resulting in many having advanced stage at the time of diagnosis [3]. Frontline treatment is comprised of chemotherapeutic agents including autologous stem cell transplant. Nearly 30–40% of patients die in the first year after diagnosis owing to an inability to reverse organ dysfunction with current therapies [4, 5].

Since AL amyloidosis is a heterogeneous disease, i.e. can affect different organs in a given patient, the AL patient experience and symptom burden can range widely based on the number and type of organs affected by amyloid fibrils. [1, 6] Further, treatments can also add to symptom burden. [7] Because the underlying clonal disorder is incurable, AL amyloidosis patients can experience relapses in disease requiring additional treatments even after successful initial therapy. Thus, AL amyloidosis patients can have significant symptoms and impairments for the remainder of their life.

The primary goal of this study was to better understand the experience of AL amyloidosis patients from the perspectives of patients themselves and the health care providers and other professionals who regularly care for AL patients. We also sought to develop a comprehensive conceptual model of symptoms of AL amyloidosis and impacts on health-related quality of life to guide development of a clinical outcome assessments tool in AL amyloidosis.

Material and methods

This exploratory study used qualitative methods to create an in-depth understanding of patient experience of AL amyloidosis symptom burden and health-related quality of life.

Participant

The study was conducted at the Froedtert and Medical College of Wisconsin Cancer Center. Patients with AL amyloidosis were invited to participate. Further, participants in the Amyloidosis Support Groups were informed of the study and provided with the study email if they were interested in participating. The study employed purposive sampling to ensure heterogeneity of our patient sample on important factors known to impact symptom: time of diagnosis, active treatment, and organ involvement. Patients were screened to ensure that the study captured the spectrum of amyloidosis, including patients who were newly diagnosed and those who had lived with the disease for more than a year, patients on active treatment and those who were not on active chemotherapies, and included the spectrum of amyloid organ involvement, including cardiac, renal, gastrointestinal, neuropathic, and soft tissue involvement. Of 8 patients purposively sampled and invited from the academic cancer center, 7 participated. Of 22 patients from the Amyloidosis Support Groups who responded with interest in participating, 13 were interviewed.

Professionals/AL amyloidosis experts were identified from professional contacts. Professionals included physicians representing a variety of specialties from a total of four institutions within the United States, advanced practice providers, and a registered nurse; all professionals worked in amyloidosis-focused practices and saw AL amyloid patients on a regular basis. Additionally, a patient advocate with long-standing experience and interactions with patients and caregivers through the Amyloidosis Support Groups was also interviewed. All professionals who were approached participated in this study.

The Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board approved the study design and methods. Participation in the study was voluntary. All participants provided verbal consent to participate in the interviews. Patients were provided with an Amazon gift card worth $100 and experts $50 for their time commitment.

Procedures

Interviews were carried out in person (N = 10) or via telephone (N = 20). All interviews were conducted by an experienced female interviewer (JM) who did not have a previous relationship with the participants and served as the Clinical Research Coordinator in the study team. The research team also comprised amyloidosis-focused clinicians (AD’Souza and ADispenzieri), health service researchers with experience in qualitative research, including a physician (RC, JP, and KF), and an amyloidosis patient advocate (MF). The semi-structured interview guide for patients included questions about symptoms, impact, health-related quality of life, and the lived experience of AL amyloidosis whereas the semi-structured interview guide for professionals included questions on symptoms, use of health-related quality of life tools to collect symptom burden in amyloidosis, and barriers to the use of these tools in clinical practice. Patient and expert question guides are included as supplementary files. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. After completion of all patient interviews and subsequent coding of the interviews, professionals were interviewed.

Data analysis

A team-based systematic content analysis approach was used [8]. The interviews with patients and experts were analyzed separately and began with patient interviews. Two members of the research team (AD and JM) read the first five patient interviews and developed an initial coding scheme, with prespecified themes based on the interview guide (e.g. symptom burden) plus open coding to capture themes that arose from the data. Each theme was further divided into subthemes rooted in patterns that emerged in symptom experience, in order to obtain more comprehensive participant accounts [9]. Patient interviews were assessed for thematic saturation, which was achieved in the first ten interviews. A similar approach was used to code expert interviews. Thematic saturation was achieved in the first four interviews. In line with Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information system (PROMIS) evaluation methodology, a second round of double coding identified facets, or attributes representative of the construct., for physical function and fatigue domains [10-12]. Facets used for coding came from previous PROMIS physical function and fatigue scoring manuals as well as previous development studies [13, 14]. Physical function had five facets (upper extremity, lower extremity, central regions, mobility, activities of daily living) and fatigue had six (fatigue frequency, fatigue duration, fatigue intensity, impact on physical, impact on mental, impact on social). The results of this coding exercise are provided in Supplementary files. Results were organized to describe the themes and subthemes; representative quotes to illustrate these were included. Symptom burden was further characterized quantitatively by number of patients or experts who mentioned a symptom (source) and the number of times it was brought up (references). Symptoms were also organized by the type of organ AL involvement and developed into a conceptual model. Symptoms that were mentioned more than twice were included in word clouds (separately for patients and experts) to allow visualization of symptom burden. All transcripts were double-coded (JM, AD and RC). Coding discrepancies were discussed and revised in an iterative process until perfect agreement was achieved.

The transcripts were managed and analyzed using NVivo 11 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia).

Results

Interviews were conducted between August 2019 and March 2020. Patients’ interviews lasted 48.4 min (range, 12–79 min) and those of the experts’ lasted 21.9 min (range, 12–34 min) on average.

Participant characteristics

Patients

The 20 patients represented men and women of diverse ages. Most (80%) had been diagnosed at least a year previously, with 40% diagnosed at least five years previously, and 25% diagnosed at least ten years previously (Table 1).

Table 1.

Self-reported characteristics of participants

| Patients | |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | N = 20 |

| Median age (range) at interview | 63 (45–84) |

| Sex: male/female | 9 (40%)/11 (60%) |

| Race | |

| White | 18 (90%) |

| African American | 1 (5%) |

| Asian | 1 (5%) |

| Time since diagnosis, years | 2.7 (0.2–12.8) |

| Cardiac involvement | 10 (50%) |

| Renal involvement | 10 (50%) |

| Neuromuscular involvement | 5 (25%) |

| Gastrointestinal/hepatic involvement | 5 (25%) |

| Prior stem cell transplant | 9 (40%) |

| On active chemotherapy | 7 (35%) |

| Experts | |

| Characteristics | N = 10 |

| Years in practice, mean (range) | 10 (3–22) |

| Sex: Male/Female | 4 (40%)/6 (60%) |

| Race | |

| White | 7 (70%) |

| African American | 2 (20%) |

| Asian | 1 (10%) |

| AL amyloidosis patients managed each month, mean (range)* | 22 (2–60) |

| Expert | |

| Physician# | 6 (60%) |

| Advanced practice provider | 2 (20%) |

| Nurse | 1 (10%) |

| Patient advocate | 1 (10%) |

This variable excludes the patient advocate

Physicians included 4 hematologist/oncologists, of who 3 were also stem cell transplant specialists, 1 cardiologist, and 1 nephrologist

Professionals

The ten professionals represented men and women, with different expertise, varying length of years in practice and geographic locations of practice.

The major themes identified in the interviews included the following: Diagnosis of AL amyloidosis, Living with AL amyloidosis, Symptom burden, Social Roles, and Barriers to collecting PROs in clinical practice. The overarching themes with subthemes along with representative quotes are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Themes and subthemes from patients and experts

| Theme and subthemes | Representative quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient | Expert | |

| The diagnosis | ||

| Delays in diagnosis | “There was a whole line of things that it looked like I had but I didn’t. … I still didn’t have any answers. No answers, no answers, no answers…. [for] almost a year and a half.” “it was two years of going from doctor to doctor, each one saying, ‘Yeah. You’ve got a, problem.’.." Patient 6 | “..they are complex patients. Usually, I meet them after they’ve already met with lots of other physicians. And it’s been a delay in figuring out the diagnosis…” Expert 8 |

| Relief at having a diagnosis | “.. there were times in the diagnosis process that I thought, "Something’s wrong, but I can’t figure it out. And neither can my doctors. And I’ve got great doctors and if they can’t figure it out, what is it?" So I was relieved when they told me what it was.” Patient 6 | “… sometimes having a diagnosis is more of a relief than having symptoms that aren’t able to be attributed to anything. I think at least they have that comfort that they know they’re being taken care of by someone who has experience in this and they can–I think that’s a little bit more relieving, hopefully.” Expert 6 |

| Fears and worry | “At times it is [scary]. It can be that way for these patients because we don’t always know how well their organs are going to fully recover. Some have full recovery of all their affected organs, and some do not.” Expert 5 | |

| Living with al amyloidosis | ||

| Healthcare visits | “It requires a lot of time and effort since people have to spend that time at the hospital or clinics or various appointments. I think that it’s really hard, and a lot of our patients are older.” Expert 9 | |

| Time to improve | “.. [AL amyloidosis] wiped me out pretty bad. And I stayed out of work for four months. Initially, it was going to be three, and I said, "I’m going to take another month," And slowly regain your energy and all that stuff back. But it probably took– I know it took several years to get it back.” Patient 4 | “Some of the symptoms will get better. But some of them kind of stick around regardless, even if.. their disease is in remission, it’s hard. They’ll still have the enlarged tongue or it’s hard to repair the damage that’s already been done. So usually,..the symptoms tend to affect people for long, long term.” Expert 4 |

| Uncertainties about the disease | “But we don’t know much about [the future]…we’re in chartered territory so let’s figure it out. Well, two years later, I’m still there.” Patient 7 | |

| Ability to care for oneself | “I had to get help with..going to the treatment. I had to get help around the house. I had to get help with everything I needed, but other than taking my own shower and getting dressed, I had to have help with everything else, meals and everything. But I had a daughter living with me.” Patient 10 | “..they may not be able to carry on with their activities of daily living. They may not be able to work. They may have to have a person to help them with daily activities as well as self care.” Expert 1 |

| Symptom burden | ||

| Symptoms from type of organ involved and stage of disease | “..it depends on the organ involvement. If there is involvement of their GI tract.. a big symptom.. is chronic constipation or chronic diarrhea. Nerve involvement is another common organ seen. They’re having chronic neuropathy, that is numbness, tingling in their fingers or toes which could be pretty bad that they are disabled with it. In some patients, it can involve the tongue, so they are having trouble eating…” Expert 7 | |

| Symptoms due to disease or treatment | “The daily life has substantially changed. I find myself being restricted by the fact that I have to take diuretics. So during the time when diuretics start effective, I couldn’t go far from the restroom. Also, due to both the amyloidosis and the heart medications, I generally need to take my blood pressure, take my pills, and that’s a three times a day. Some of the pills are supposed to be taken with meals, some that aren’t supposed to be taken with dairy products. Some of them are supposed to be taken at night. So, basically, the medications.…have taken over my daily schedule. In terms of physical abilities, or lack of them, I’ve never been unable to dress myself, go to the bathroom, and just survive in the house.” Patient 19 | “I think the symptoms are–you know, are there. And the treatment also has its effects. Not only chemotherapy and things, but even the diuretics, just having to be more aware of the dietary modifications, avoiding salt, avoiding fluid, not being able to go out to eat at restaurants. … And I think that’s been kind of not reported limitation of the experience with this based on the treatment from it.” Expert 6 |

| Lack of symptom resolution | “..if you really look back on it there are lots of changes that you say this is my new normal and the next step isn’t always a step forward. More and more it’s a step backward and you just start accepting those backward steps..thinking of that as normal.” Patient 1

“I’m still in a wheelchair. I cannot stand and I can’t lift my arms above my head, but I’m now able to talk, obviously. I have better breathing. I’m able to cook if it’s not too heavy.” Patient 8 |

|

| Social roles | ||

| Support system | “You find out sometimes who your friends are as far as helping you–being there during the bad times. But then again you also realize that some people don’t know how to react to– early on, especially.” Patient 4 “I have three sons that are very understanding and supportive. And various relatives that I have and friends have all been there and said if I need anything, don’t hesitate to give them a call or whatever.” Patient 7 “You really do need a caregiver. Somebody that you know wants you to live.” Patient 16 “I feel like I’m doing pretty good. I have a huge support team, both at the hospital and at home, and I feel I’m doing okay.” Patient 17 |

“I think people have a hard time understanding exactly, especially with amyloidosis, it’s such a rare disease that a lot of people don’t know [much about it]. It requires a lot of time and effort since people have to spend that time at the hospital or clinics or various appointments. … and a lot of our patients are older. So finding somebody consistent even if they don’t have a spouse or significant other to get them to appointments and manage their outside life from the hospital as well [can be really hard].” Expert 9 |

| Change in relationships | “My son has been treating me like I’m going to break if the wind blows. That’s been a little frustrating that if I’m trying to help do some things around the house, he gets all upset because he thinks I’m pushing.” Patient 17 “..at the end of the day, I’m still a mom, so the things that I used to do with [my kids], I still want to do with them, so I’m kind of disappointed that this is my situation.” Patient 18 “Our son and [his family] live about 1,000 miles away. So I haven’t been able to visit them.” Patient 19 “I saw somebody in the grocery store that I knew very well […] and I could tell that he was uncomfortable when he saw me because I’m almost 40 lb less than what I was…you start to get treated a little differently by people once they know you’re tainted or your life is at stake.” Patient 11 |

“I think the most common is just that they’re kind of antsy to get out. They see their caregiver and maybe some close family but a lot of times the patients aren’t able to see their grandkids because the grandkids are sick. And then a lot of times people aren’t able to go–a lot of people, if they’re religious, can’t go to church and that can be really tough after the transplant.” Expert 4 |

| Social isolation | “And so [amyloidosis] goes beyond, I mean, the discomfort and the pain, but maybe limiting social interactions and activities.” Expert 2 “I don’t see [amyloidosis] impacting their social activities or relationships with family and friends? In fact, if any, they’ll become more social. Because they know that they have something which is serious.” Expert 10 |

|

| Work, productivity, and finances | “I had chemo in seven months over an eight month period before the stem cell transplant. But I continued to work full-time. It definitely affect[ed] me. It was not easy. I mean, of course, it was very tiring and the side effects were not so nice. I [had] one nice benefit in that the job I have I could work from home sometimes so I could sleep in more and stay in my pajamas and do my job from home instead of driving into the office.” Patient 5 “..I had to quit working because it was hard to put one foot in front of the other. …because of my level of immunosuppression, associated with medication to prevent heart rejection as well as the chemotherapy I received. I can no longer work as a veterinarian. So that is frustrating to get out because that was my life’s work. I had to sell my practice at a huge loss.” Patient 9 |

“.. People mention their loss of work… their inability to work, and the fear of loss of insurance. And then, also, just the cost of all the appointments and treatments and just transportation. Sometimes it starts with just like how expensive parking is every time they come to visit, or how far they need to travel because usually amyloid centers are few and far between. And also they often can’t come all by themselves, so their family members–I’ve had patients who’ve had to leave their jobs or were patients who’ve lost their jobs, and are struggling to get Medicare or disability so that they can continue to get care so that it doesn’t get worse. It’s very costly, especially early on, while figuring it out and getting early therapy.” Expert 8 |

Theme I. Diagnosis of AL amyloidosis

Patients identified the difficulty in getting a diagnosis. Many patient symptoms were non-specific, such as slowing down or fatigue, and were initially attributed by patients or their doctors as related to aging. For some patients this process took over a year of specialists, tests, and misdiagnosis to arrive at their AL diagnosis. Some patients expressed a sense of relief upon receiving a diagnosis.

Professionals also highlighted the arduous path to diagnosis that patients often face as well as relief after obtaining the diagnosis. Some also endorsed the initial worry and fears for patients after the diagnosis of amyloidosis.

Theme II. Living with AL amyloidosis

Patients recognized the long delay after starting treatment before they noticed improvement. This period sometimes took years to achieve. Patients also acknowledged that owing to the severity of the disease they were not able to do activities of daily living or needed assistance to care for themselves. Patients with AL amyloidosis described that the disease itself had many uncertainties on what could be expected after the initial treatment phase.

Professionals brought up multiple perspectives centered on the complexity of healthcare for patients that could result in several unique issues patients with AL amyloidosis face. For example, given the complex and multisystemic nature of the disease, patients would need to have multiple health care visits which added to the burden of living with the disease. Professionals expressed that the ability to care for oneself can be challenging for patients with AL amyloidosis and thus the need for dependence on others, particularly during the initial stage of the disease. Like patients, experts discussed the long time it may take for patients to feel improved even after the underlying disease may be well controlled, consistent with the pathophysiology of the disease and its treatment.

Theme III. Symptom burden of AL amyloidosis

The symptom experience of patients with AL amyloidosis was extensive and variable. Patients recognized symptoms but sometimes had difficulty identifying the source, not sure whether to attribute symptoms to amyloidosis, aging/chronic conditions, or treatment of AL amyloidosis. Patients talked about life adjustments owing to AL disease and its treatment even years after diagnosis. In specific, patients perceived that symptoms of AL amyloidosis may never resolve and that this prevented them from being able to do what they were previously able to do. Patients described that in addition to the disease itself, they also developed new symptoms from the treatment. Professionals caring for AL amyloidosis patients also described numerous and severe symptomatology of AL amyloidosis. Specifically, they noted that symptoms of AL amyloidosis can depend on the organs involved with fibril deposition and the stage of the disease. AL experts also recognized that some symptoms arise from treatment of the disease.

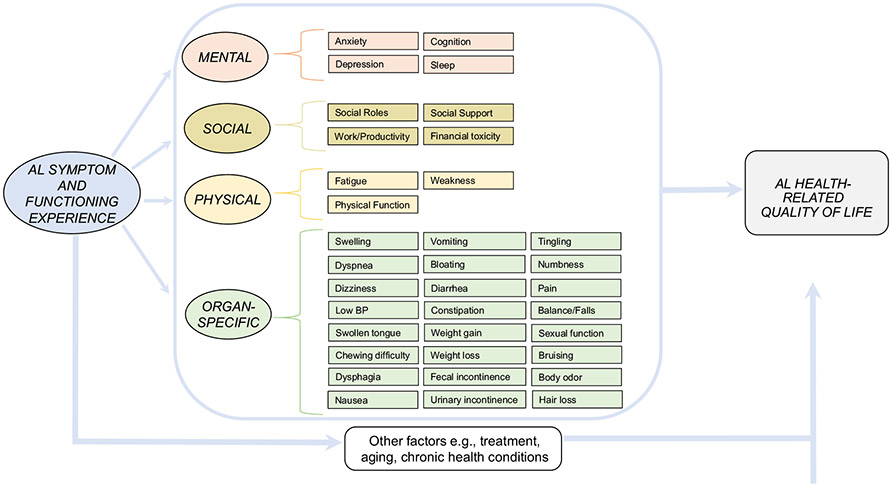

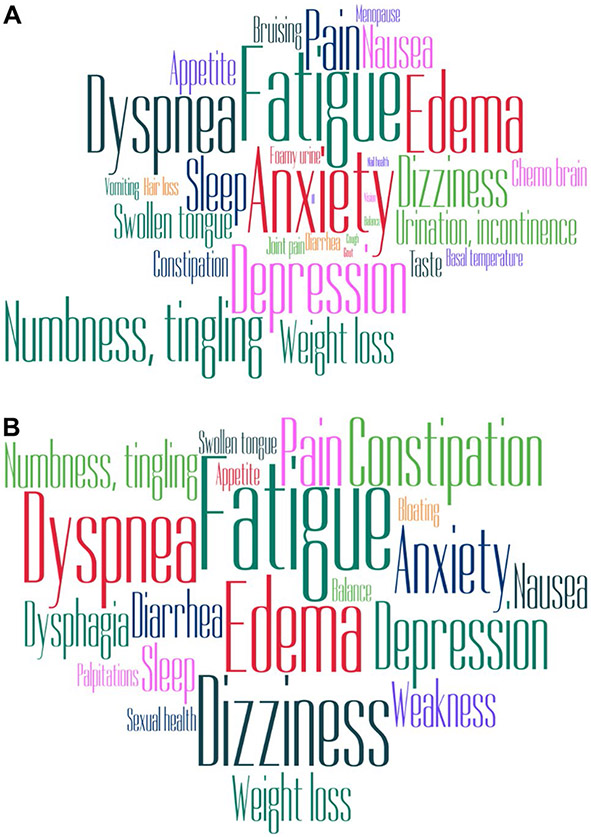

Based on the reported AL amyloidosis symptoms, we created a conceptual model of the symptom experience of AL amyloidosis (Fig. 1). Figure 2 shows a representation of symptoms that were endorsed more than twice as word clouds by patients (A) and experts (B).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of symptoms and impact of AL amyloidosis

Fig. 2.

Word clouds demonstrating symptom burden elicitation. A Patient symptom experience B Expert symptom elicitation

Theme IV. Social roles

Patient participants expressed the need for a support system of family, friends, and the healthcare team that helped them manage the disease. They noted changes in relationships with family and friends in life owing to AL amyloidosis. Multiple patients were frustrated by the inability to maintain their work schedule and remain productive.

AL professionals also reiterated several changes in social roles faced by patients. They recognized the large and important role that caregivers add to quality of life for AL amyloidosis patients. Some experts felt that AL amyloidosis may contribute to social isolation, subsequently impacting quality of life, but others felt that having AL amyloidosis may result in patients spending more time with family and friends. Experts also expressed the financial burden and challenges for patients and caregivers, both from healthcare costs and loss of income.

Barriers to QOL collection in clinic

One of our pre-specified themes of interest included perspectives from AL experts regarding the value of health-related quality of life survey tools and collection of PROs from AL amyloidosis patients in the clinic. Multiple AL experts recognized the value of collecting PROs in clinic, specifically to have these aid patients to bring up issues they may forget to mention or feel embarrassed to bring up, or questions about functional status that may not come to the forefront during a clinic visit. Participants recognized that the uniform administration of surveys can be cumbersome, whether these were done in the clinic electronically or on paper, additional resources that needed to be set up, and the ease of administration. They noted the added burden of completing surveys frequently may be frustrating for patients in addition to specific limitations faced by AL patients, e.g. neuropathy. Some experts recognized the need for clinicians to have guidance to interpret the results and explanations or algorithms on what to do with the responses. Finally, AL experts also identified that responses may be biased toward patients who are able to navigate the healthcare system better or skewed to those who have more symptoms.

Discussion

This qualitative study focused on AL amyloidosis and integrated patient and expert perspectives on symptom burden and well-being. Our findings provide a multidimensional conceptual outline of the symptom experience of AL amyloidosis comprising physical, emotional, psychological, social, and AL organ-specific facets of well-being. Though our primary goal was concept elicitation of symptoms of AL amyloidosis in order to develop a conceptual model, we also wanted to understand other perspectives particularly around diagnosis as well as perspectives from patients living with amyloidosis beyond the initial year after diagnosis.

This study identifies delayed diagnosis, one of the greatest challenges in AL amyloidosis, [3] as a significant facet of the AL experience. Multiple barriers exist that impede diagnosis of AL amyloidosis, including symptoms that are mistaken for normal aging given the non-specific nature of some symptoms such as fatigue and slowing in activities of daily living. [15] Further, patients also identified that lack of familiarity with the disease among physicians also extended the time to diagnosis. Another aspect of diagnosis of AL amyloidosis identified by both patients and professionals was relief after the diagnosis was made. In a prior study of self-reported distress in patients with AL amyloidosis, patients with cardiac involvement and advanced disease were found to have lower self-reported distress, led researchers to hypothesize relief occurred when diagnosed with a condition after having symptoms for a prolonged period of time. [16] Our qualitative study confirms this association.

The patient experience of AL amyloidosis is wide with a range of symptoms, the nature and frequency of which are related to time to diagnosis, type of organ involvement, and treatment. Both patients and professionals identified symptoms due to disease but also new symptoms or existing symptoms being affected by treatment of the disease. Significant emotional toll of the disease related to frustration, fear about the future, anxiety, and depression are consistent with known studies describing health-related quality of life in AL amyloidosis. [17-19].

Ultimately, the greatest impact of the disease was manifest in a change in social roles. Multiple prior studies have shown that this aspect of quality of life is the most impaired in AL amyloidosis patients. [15, 19] Many aspects of daily functioning, including dependence on others, assistance with health care needs, family life and relationships, and work/productivity were affected.

Though AL amyloidosis professionals identified the importance of incorporating patient-reported outcomes into clinical care of patients, they also identified several barriers in using such information in routine practice. These barriers highlight the challenges that exist toward the uniform use of patient-reported outcomes within the complex healthcare structure and need for creative ways to incorporate these important health data into routine clinical care [20].

Our study has some limitations, including the small sample size. Many of the patient respondents were recruited through patient advocacy groups. To help ensure the generalizability of the findings, we also included some patients recruited directly from a clinic. Though disease diagnosis was not verified for patients recruited from support groups, study participants had long-standing relationships with AL amyloidosis patient advocacy groups and AL-specific treatment, so it is expected that they were patients with confirmed diagnosis. To obtain a diverse set of experiences from AL patients, we were deliberate about enrolling patients who had lived longer than a year. However, surviving patients may have had less severe initial symptoms, and the different weight given by experts versus patients to some symptoms may, in part, reflect this selection bias.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive understanding of the important experiences of symptom burden and health-related quality of life from AL amyloidosis patients’ and from the perspectives of professionals who care for patients with AL amyloidosis. Overall, these results highlight the substantial burden of AL amyloidosis on patients and their caregivers. These data help with the identification of a preliminary model of concepts of interest for development of a clinical outcome assessment tool for AL amyloidosis. Ultimately, the purpose of this work is to ensure that patient-reported outcomes are consistently considered and utilized in the design of drug trials as well as clinical care in AL amyloidosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Ms. Claire Piehowski’s contribution toward data management and coding assistance. Financial support for this study was provided by a K23 HL141445 Mentored Career Development Award. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02943-w.

References

- 1.Bayliss M, McCausland KL, Guthrie SD, & White MK (2017). The burden of amyloid light chain amyloidosis on health-related quality of life. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 12(1), 15. 10.1186/s13023-016-0564-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merlini G (2017). AL amyloidosis: from molecular mechanisms to targeted therapies. Hematology/The Education Program of the American Society of Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program, 2017(1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lousada I, Comenzo RL, Landau H, Guthrie S, & Merlini G (2015). Light chain amyloidosis: Patient experience survey from the Amyloidosis Research Consortium. Advances in Therapy, 32(10), 920–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muchtar E, Gertz MA, Kumar SK, Lacy MQ, Dingli D, Buadi FK, … & Dispenzieri A (2017). Improved outcomes for newly diagnosed AL amyloidosis between 2000 and 2014: cracking the glass ceiling of early death. Blood, 129(15), 2111–2119. 10.1182/blood-2016-11-751628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar SK, Gertz MA, Lacy MQ, Dingli D, Hayman SR, Buadi FK, et al. (2011). Recent improvements in survival in primary systemic amyloidosis and the importance of an early mortality risk score. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 86(1), 12–18. 10.4065/mcp.2010.0480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin HM, Seldin D, Hui AM, Berg D, Dietrich CN, & Flood E (2015). The patient’s perspective on the symptom and everyday life impact of AL amyloidosis. Amyloid : The International Journal of Experimental and Clinical Investigation : The Official Journal of the International Society of Amyloidosis, 22(4), 244–251. 10.3109/13506129.2015.1102131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizio AA, White MK, McCausland KL, Quock TP, Guthrie SD, Yokota M, & Bayliss MS (2018). Treatment tolerability in patients with immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis. American Health & Drug Benefits, 11(8), 430. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsieh HF, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aronson J (1995). A pragmatic view of thematic analysis. The Qualitative Report, 2(1), 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B, …PROMIS Cooperative Group. (2007) The patient-reported outcome measurement information system (PROMIS): Progress of an NIH Roadmap Cooperative Agreement during its first two years. Medical Care 45 S3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, & Stone AA (2007). Evaluation of item candidates: The PROMIS qualitative item review. Medical Care, 45(5 Suppl 1), S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riley WT, Pilkonis P, & Cella D (2011). Application of the National Institutes of Health patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS®) to mental health research. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 14(4), 201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Retrieved from http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Fatigue_Scoring_Manual.pdf. 2019.

- 14.Hays RD, Spritzer K, Amtmann D, Lai JS, DeWitt EM, & Rothrock N (2013). Upper-extremity and mobility subdomains from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) adult physical functioning item bank. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 94(11), 2291–2296. 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCausland KL, White MK, Guthrie SD, Quock T, Finkel M, Lousada I, & Bayliss MS (2018). Light chain (AL) amyloidosis: The journey to diagnosis. Patient, 11(2), 207–216. 10.1007/s40271-017-0273-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright NL, Flynn KE, Brazauskas R, Hari P, & D’Souza A (2018). Patient-reported distress is prevalent in systemic light chain (AL) amyloidosis but not determined by severity of disease. Amyloid : The International Journal of Experimental and Clinical investigation : The Official Journal of the International Society of Amyloidosis, 25(2), 129–134. 10.1080/13506129.2018.1486298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanchorawala V, McCausland KL, White MK, Bayliss MS, Guthrie SD, Lo S, & Skinner M (2017). A longitudinal evaluation of health-related quality of life in patients with AL amyloidosis: associations with health outcomes over time. British Journal of Haematology, 179(3), 461–470. 10.1111/bjh.14889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCausland KL, Quock TP, Rizio AA, Bayliss MS, White MK, Guthrie SD, & Sanchorawala V (2018). Cardiac biomarkers and health-related quality of life in patients with light chain (AL) amyloidosis. British Journal of Haematology. 10.1111/bjh.15693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Souza A, Magnus BE, Myers J, Dispenzieri A, & Flynn KE (2020). The use of PROMIS patient-reported outcomes (PROs) to inform light chain (AL) amyloid disease severity at diagnosis. Amyloid : The International Journal of Experimental and Clinical Investigation : The Official Journal of the International Society of Amyloidosis. 10.1080/13506129.2020.1713743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warsame R, & D’Souza A (2019). Patient reported outcomes have arrived: A practical overview for clinicians in using patient reported outcomes in oncology. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 94(11), 2291–2301. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.