Abstract

To investigate interactions between the multidrug resistance protein (MRP) and antimicrobial agents, we examined the effects of 12 agents on vincristine sensitivity and efflux of the calcein acetoxy-methyl ester (calcein-AM) of a MRP substrate in MRP-overexpressing cells. Only ofloxacin and erythromycin enhanced sensitivity with increased intracellular vincristine accumulation and inhibited the calcein-AM efflux. Our findings suggest that the two agents are possible MRP substrates and may competitively inhibit MRP function as a drug efflux pump.

Novel transporter proteins of the ATP-binding cassette superfamily have been identified, and their substrate specificities and tissue distributions have been investigated (10, 11). Several proteins of the superfamily, such as P-glycoprotein (Pgp) encoded by the MDR1/mdr1 gene, interact directly or indirectly with various drugs and transport drugs in an ATP energy-dependent manner out of cells (6, 12). This leads to the resistance of cancer cells against multiple anticancer drugs, a phenomenon known as multidrug resistance. The multidrug resistance protein (MRP [also called MRP1]), a member of the superfamily, also functions as a drug efflux pump (12). MRP is broadly distributed in normal human tissues, and the highest levels are found in the testes, skeletal muscle, heart, kidney, and lung (3, 12). In vitro studies using membrane vesicles of cells have shown that MRP appears to transport a broad spectrum of anionic substrates, such as glutathione disulfide, 17β-estradiol 17-(β-d-glucuronide), and bile salt derivatives (12). Several agents, including calcium channel blockers and immunosuppressants, reverse Pgp- and MRP-mediated multidrug resistance probably by the competitive inhibition of Pgp and MRP functions (1, 12). Probenecid and the leukotriene receptor antagonist MK571 are relatively specific reversal agents for MRP rather than for Pgp (12). With regard to antimicrobial agents, erythromycin and difloxacin reverse Pgp- and MRP-mediated multidrug resistance in vitro, respectively (5, 7). Thus, interactions between antimicrobial agents and MRP are of great interest, because MRP is probably involved in biliary and renal excretion of drugs and protection of the physiological blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (12, 17).

In this study, to investigate interactions between antimicrobial agents and MRP, we examined the effects of 12 antimicrobial agents on vincristine sensitivity and efflux of the calcein acetoxy-methyl ester (calcein-AM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) of a MRP substrate in MRP-overexpressing human leukemia HL60R cells. Multidrug-resistant HL60R cells were selected from HL60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells by doxorubicin and expressed high levels of MRP mRNA but no MDR1 mRNA (15). HL60R cells are 12 times as resistant as parental HL60 cells to vincristine (15). The cells were cultured at 37°C under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in complete RPMI 1640 medium. The 12 antimicrobial agents tested were as follows: ofloxacin (Daiichi Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan), ciprofloxacin (Bayer Yakuhin, Osaka, Japan), tosufloxacin, erythromycin, piperacillin (all from Toyama Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan), enoxacin (Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co., Osaka, Japan), clarithromycin (Taisho Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan), aspoxicillin (Tanabe Seiyaku Co., Tokyo, Japan), cefotiam (Takeda Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan), ceftazidime (Glaxo Co., Tokyo, Japan), kanamycin (Meiji Seika Kaisha, Tokyo, Japan), and gentamicin (Schering-Plough, Tokyo, Japan).

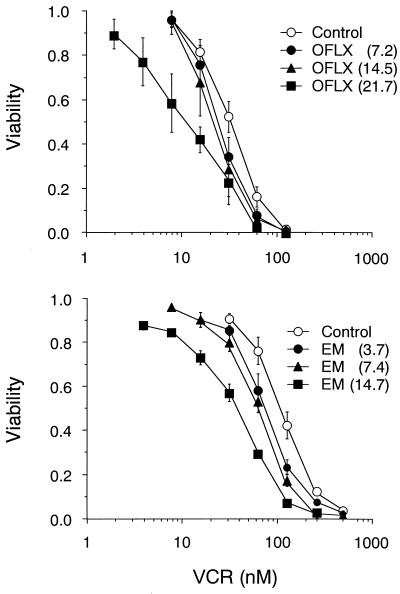

The sensitivity to vincristine (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, Mo.) of a good substrate for MRP was determined by using the tetrazolium dye assay (13), as reported previously (15). HL60R cells (1,500 cells/well) were seeded onto 96-well plates with various concentrations of vincristine in the presence or absence of an antimicrobial agent. In preliminary experiments, we measured the cytotoxicity of each agent in HL60R cells and determined the concentration of the agent to ensure that the cytotoxicity was less than 5%. The IC50 was defined as the concentration of vincristine that reduced the absorbance in each test by 50%. The reversal effect was expressed as the ratio of the IC50 in the presence and absence (control) of each agent. Each study was repeated three times. For comparison, peak levels of vincristine in plasma are approximately 0.4 μM in humans following the infusion of a conventional dose of 1.4 mg/m2 (19). The maximum noncytotoxic concentration (in milligrams per liter) of each agent tested here was as follows: ofloxacin, 21.7; ciprofloxacin, 1.2; tosufloxacin, 11.9; enoxacin, 20.8; piperacillin, 307; aspoxicillin, 1,248; cefotiam, 12.0; ceftazidime, 82.8; kanamycin, 40.8; gentamicin, 630; clarithromycin, 11.2; and erythromycin, 14.7. These concentrations were used in the present study. The IC50s of vincristine were 41.2 ± 4.20 nM in the control, 13.1 ± 3.22 nM with ofloxacin, and 16.7 ± 1.74 nM with erythromycin. Among the 12 agents tested, only these two agents significantly enhanced the vincristine sensitivity of HL60R cells (P < 0.01 versus the control by the Dunnet test). The reversal effects were 3.08 ± 0.36 and 2.46 ± 0.06, respectively. We then examined the dose-dependent effects of ofloxacin and erythromycin on the vincristine sensitivity of HL60R cells (Fig. 1). High concentrations of ofloxacin and erythromycin resulted in significant decreases in vincristine IC50 (P = 0.025 in ofloxacin and P = 0.045 in erythromycin by Spearman's correlation method).

FIG. 1.

Reversal effects of ofloxacin and erythromycin on the vincristine sensitivity of HL60R cells. The vincristine sensitivity of HL60R cells was examined in the presence and absence (control) of ofloxacin and erythromycin. Data represent the means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments. OFLX, ofloxacin (in milligrams per liter); EM, erythromycin (in milligrams per liter); VCR, vincristine (in nanomolar units).

To investigate the above modulatory mechanism of ofloxacin and erythromycin, we measured intracellular [3H]vincristine accumulation in HL60R cells. HL60R cells (5,000 cells/well) were seeded onto 12-well plates, cultured for 72 h prior to the assay, and incubated for 60 min at 37°C with 30 nM [3H]vincristine (Amersham Co., Tokyo) in the presence or absence (control) of each agent. Aliquots (0.5 ml) of cells were removed and ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was added to stop accumulation. After two washes with ice-cold PBS, cells were lysed with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and the cell-associated radioactivity was determined using a liquid scintillation system. Each study was performed in triplicate. The cell-associated radioactivities were 1,945 ± 89.9 dpm in the control, 2,512 ± 71.1 dpm with ofloxacin, and 2,259 ± 128 dpm with erythromycin (P < 0.001 in ofloxacin and P < 0.05 in erythromycin versus control by Student's t test). Compared to the accumulation in control, ofloxacin and erythromycin resulted in 29 and 16% rises in the mean value of intracellular [3H]vincristine, respectively.

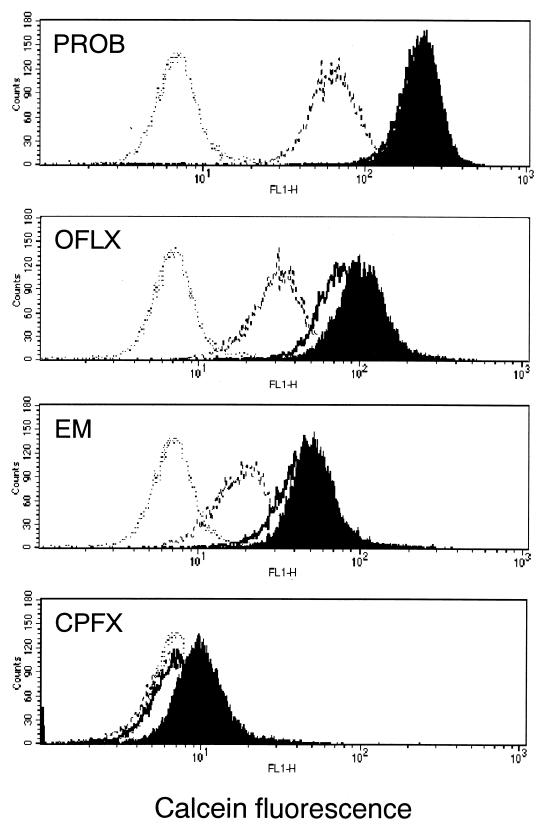

We investigated whether ofloxacin and erythromycin inhibit MRP function as an efflux pump, using calcein-AM accumulation and efflux assays (2). Calcein-AM, a highly lipophilic and nonfluorescent compound, rapidly penetrates the plasma cell membrane and is transformed into calcein of the intensively fluorescent organic anion by intracellular esterase (8). MRP actively pumps out calcein-AM and fluorescent calcein from the cytoplasm; loading of MRP-expressing cells with calcein-AM reduces accumulation of intracellular calcein (2). Briefly, the efflux action of MRP in the cells was evaluated by measuring the intracellular fluorescence of calcein with a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Medical System, Sharon, Mass.) equipped with an argon laser. A suspension of log-phase cells was incubated in 0.25 μM calcein-AM for 30 min (accumulation phase), washed twice with cold PBS, and then resuspended in fluorescent dye-free medium for 60 min (efflux phase). Both accumulation and efflux assays were performed in the presence and absence (control) of each antimicrobial agent (Fig. 2). Probenecid and ciprofloxacin were used as positive and negative controls of MRP inhibition, respectively. In the accumulation phase, the mean fluorescence values of intracellular calcein were 223 with probenecid, 106 with ofloxacin, 53.7 with erythromycin, 10.6 with ciprofloxacin, and 7.58 without agents (control). In the efflux phase with each of the above agents, the value was 214 with probenecid, 82.4 with ofloxacin, 46.2 with erythromycin, and 8.02 with ciprofloxacin. The values without agents (control) in the efflux phase were 67.6 for probenecid, 33.3 for ofloxacin, 20.6 for erythromycin, and 7.36 for ciprofloxacin. Compared to the respective control of each phase, ofloxacin and erythromycin increased by approximately 14 and 7 times the accumulation of calcein-AM, respectively, and reduced by approximately half its efflux from the cells. In the accumulation phase, we observed a synergistic effect of ofloxacin and erythromycin (data not shown). Ciprofloxacin at 20 mg/liter showed no effect (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Effects of ofloxacin and erythromycin on intracellular accumulation and efflux of calcein-AM in HL60R cells. Fluorescence of intracellular calcein was analyzed by flow cytometry. The accumulation phase was examined in the presence (shaded) and absence (dotted line) of agents. The efflux phase was also examined in the presence (bold line) and absence (dashed line) of agents. PROB, probenecid (2 mM); OFLX, ofloxacin (21.7 mg/liter); EM, erythromycin (14.7 mg/liter); CPFX, ciprofloxacin (1.2 mg/liter).

The present study demonstrated that only ofloxacin and erythromycin significantly enhanced the vincristine sensitivity of HL60R cells, although the reversal effects were modest. In addition, the two agents significantly increased intracellular accumulation of vincristine and calcein-AM and inhibited the efflux of the latter from the cells. These results suggest that ofloxacin and erythromycin are possible substrates for MRP and, like other reversal agents for MRP, may competitively inhibit MRP function as a drug efflux pump. Drug transporter proteins play a critical role in eliminating drugs from cells and the human body. In fact, pharmacological studies with mdr1a gene knockout mice have shown reduced renal clearance of substrate drugs (9). Similarly, it is expected that concomitant use of multiple substrate drugs for a certain transporter protein might delay elimination of the drug and/or enhance its cytotoxicity, as shown in the present study. In particular, because MRP as well as Pgp are ubiquitously distributed in various tissues, understanding the interaction between MRP and various agents is clinically important.

In the present study, only one of four quinolones (ofloxacin) modulated MRP. Considered with the substrate specificity of MRP (12), this difference among quinolones may be due to differences in the hydrophobic and/or anionic structural characteristics. With respect to ofloxacin, Okano et al. (16) suggested the interaction between ofloxacin and cationic transport system in rat renal brush-border membranes in vitro, but Foote and Halstenson (4) reported the involvement of both cationic and anionic systems in rat renal clearance in vivo. These findings suggest that ofloxacin is possibly eliminated by both cationic and anionic transport systems; however, biochemical analysis using membrane vesicles overexpressing each transporter protein should be performed to confirm this hypothesis.

We also demonstrated that erythromycin is a possible substrate for MRP. To date, the metabolism of most macrolides has been explained by cytochrome P450 enzymes (14, 18, 24), and only a few studies have described the involvement of drug transporter proteins (20–23). The latter studies showed that erythromycin was a likely substrate for Pgp and reversed Pgp-mediated multidrug resistance (7, 20, 21). Thus, erythromycin seems to be a substrate for both MRP and Pgp. On the other hand, Wakasugi et al. (23) demonstrated that clarithromycin inhibited the efflux of digoxin as a substrate for Pgp and increased its intracellular accumulation in vitro. Considering this observation together with the present results, clarithromycin may be at least a substrate for Pgp but not MRP. Thus, it is likely that different transporter proteins are involved in the elimination of each macrolide.

In conclusion, our results suggested that ofloxacin and erythromycin are possible substrates for MRP, indicating possible interactions between ofloxacin and erythromycin and between them and other substrate drugs for MRP, such as vincristine. The concentrations of ofloxacin and erythromycin used here were similar to those achieved clinically. Accordingly, the above interactions should be taken into consideration when these agents are used clinically and in pharmacological studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambudkar S V, Dey S, Hrycyna C A, Ramachandra M, Pastan I, Gottesman M M. Biochemical, cellular, and pharmacological aspects of the multidrug transporter. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1999;39:361–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feller N, Kuiper C M, Lankelma J, Ruhdai J K, Scheper R J, Pinedo H M, Broxterman H J. Functional detection of MDR1/p170 and MRP/p190-mediated multidrug resistance in tumour cells by flow cytometry. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:543–549. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flens M J, Zaman G J, Valk P, Izquierdo M A, Schroeijers A B, Scheffer G L, Groep P, Hass M, Meijer C J, Scheper R J. Tissue distribution of the multidrug resistance protein. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:1237–1247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foote E F, Halstenson C E. Effects of probenecid and cimetidine on renal disposition of ofloxacin in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:456–458. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gollapudi S, Thadepalli F, Kim C H, Gupta S. Difloxacin reverses multidrug resistance in HL-60/AR cells that overexpress the multidrug resistance-related (MRP) gene. Oncol Res. 1995;7:213–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottesman M M, Pastan I. Biochemistry of multidrug resistance mediated by the multidrug transporter. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:385–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofsli E, Nissen-Meyer J. Reversal of drug resistance by erythromycin: erythromycin increases the accumulation of actinomycin D and doxorubicin in multidrug-resistant cells. Int J Cancer. 1989;44:149–154. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910440126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollo Z, Homolya L, Dabis C W, Sarkadi B. Calcein accumulation as a fluorometric functional assay of the multidrug transporter. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1191:384–388. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim R B, Fromm M F, Wandel C, Leake B, Wood A J, Roden D M, Wilkinson G R. The drug transporter P-glycoprotein limits oral absorption and brain entry of HIV-1 protease inhibitors. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:289–294. doi: 10.1172/JCI1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kool M, Dehaas M, Scheffer G L, Scheper R J, van Eijk M J T, Juijn J A, Baas F, Boast P. Analysis of expression of cMOAT (MRP2), MRP3, MRP4, and MRP5, homologues of the multidrug resistance-associated protein gene (MRP1), in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3537–3547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kool M, van der Linden M, de Haas M, Baas F, Borst P. Expression of human MRP6, a homologue of the multidrug resistance protein gene MRP1, in tissues and cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loe D W, Deeley R G, Cole S P. Biology of the multidrug resistance-associated protein, MRP. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:945–957. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray M. Drug-mediated inactivation of cytochrome P450. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1997;24:465–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1997.tb01228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narasaki F, Matsuo I, Ikuno N, Fukuda M, Soda H, Oka M. Multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) gene expression in human lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:2079–2082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okano T, Maegawa H, Inui K, Hori R. Interaction of ofloxacin with organic cation transport system in rat renal brush-border membranes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;255:1033–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao V V, Dahlheimer J L, Bardgett M E, Snyder A Z, Finch R A, Sartorelli A C, Piwnica-Worms D. Choroid plexus epithelial expression of MDR1 P glycoprotein and multidrug resistance-associated protein contribute to the blood-cerebrospinal-fluid drug-permeability barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3900–3905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodrigues A D, Roberts E M, Mulford D J, Yao Y, Ouellet D. Oxidative metabolism of clarithromycin in the presence of human liver microsomes: major role for the cytochrome P4503A (CYP3A) subfamily. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:623–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowinsky E K, Donehower R C. The clinical pharmacology and use of antimicrotubule agents in cancer chemotherapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 1991;52:35–84. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(91)90086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuetz E G, Yasuda K, Arimori K, Schuetz J D. Human MDR1 and mouse mdr1a P-glycoprotein alter the cellular retention and disposition of erythromycin, but not of retinoic acid or benzo(a)pyrene. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;350:340–347. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takano M, Hasegawa R, Fukuda T, Yumoto R, Nagai J, Murakami T. Interaction with P-glycoprotein and transport of erythromycin, midazolam and ketoconazole in Caco-2 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;358:289–294. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00607-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vazifeh D, Abdelghaffar H, Labro M T. Cellular accumulation of the new ketolide RU 64004 by human neutrophils: comparison with that of azithromycin and roxithromycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2099–2107. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakasugi H, Yano I, Ito T, Hashida T, Futami T, Nohara R, Sasayama S, Inui K. Effect of clarithromycin on renal excretion of digoxin: interaction with P-glycoprotein. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:123–128. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkinson G R. Cytochrome P4503A (CYP3A) metabolism: prediction of in vivo activity in humans. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1996;24:475–490. doi: 10.1007/BF02353475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]