Abstract

Oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OAC) provides an ideal case study to characterize large-scale rearrangements. Using whole genome short-read sequencing of 383 cases, for which 214 had matched whole transcriptomes, we observed structural variations (SV) with a predominance of deletions, tandem duplications and inter-chromosome junctions that could be identified as LINE-1 mobile element (ME) insertions. Complex clusters of rearrangements resembling breakage-fusion-bridge cycles or extrachromosomal circular DNA accounted for 22% of complex SVs affecting known oncogenes. Counting SV events affecting known driver genes substantially increased the recurrence rates of these drivers. After excluding fragile sites, we identified 51 candidate new drivers in genomic regions disrupted by SVs, including ETV5, KAT6B and CLTC. RUNX1 was the most recurrently altered gene (24%), with many deletions inactivating the RUNT domain but preserved the reading frame, suggesting an altered protein product. These findings underscore the importance of identification of SV events in OAC with implications for targeted therapies.

Subject terms: Oesophageal cancer, Cancer genomics, Oncogenes, Tumour-suppressor proteins

Genomic structural variants (SVs) in cancer are notoriously difficult to identify, despite the impact they have on cancer progression and treatment efficacy. This study applies state-of-the-art computational methods to catalogue SVs in 383 cases of oesophageal cancer, uncovering mutational patterns and new disease drivers.

Introduction

Patterns of rearrangement can reflect the underlying mechanism generating the rearrangement, genetic instabilities or mutagen exposures, and these may in turn determine response to therapy or help explain the underlying aetiology1,2. Rearrangements in driver genes, such as deletions, amplifications, gene breakages and gene fusions, seem likely to be at least as important a source of driver mutations as single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels in many carcinomas3–5. The Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) analysed whole genome sequencing data from multiple cancer types and this revealed a remarkable heterogeneity of SVs. In some cancer types, such as breast and ovary, it was estimated that up to three times more driver genes are altered by SVs than by SNVs and indels3. Nevertheless, our ability to identify SV driver events lags far behind that of SNV and indel events. This is primarily because there is no measure of the background SV mutation rate, unlike synonymous SNV mutations, that enable the identification of driver genes disrupted by SNVs and rearrangements often involve large genomic regions6,7.

Oesophageal cancer, especially the subtype oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OAC), emerged from the PCAWG analysis (n = 100 OACs) as a cancer type with one of the highest burdens of SVs with complex rearrangements1,3. These include breakage-fusion-bridge (BFB) cycles; catastrophic chromothripsis events with oscillating copy number patterns8, deletions in the fragile-sites and the highest rate of somatic mobile element (ME) inserts of any cancer type1,9–12. MEs are mainly inserts from Long Interspersed Nuclear Element-1 (LINE-1) retrotransposons, and can consist either of LINE-1 sequence alone or LINE-1 with up to a few kb of 3′ flanking unique genomic sequence transduced11,13.

Driver alterations in SNVs and indels are well characterized in OAC, as are distinct copy number (CN) amplification of oncogenes (e.g. ERBB2, EGFR, RB1, GATA4/6, CCND1 and MDM2) and loss of tumour suppressors (e.g. TP53, CDKN2A, CDKN2B)9,10,14. Rearrangement processes such as BFB cycles and extrachromosomal circular DNA (ecDNA) have been shown to result in copy number amplification in key oncogenes15–18 while a variety of SVs can disrupt tumour suppressor genes, including LINE-1 insertions11,14. However, to date the analysis of these complex events in OAC has not been performed at the detail required to fully elucidate the spectrum and underlying mechanisms for complex SVs.

In this analysis we combine recent advances in methods for dissecting complex rearrangements and identifying driver events1,3,11,19–22 to characterize SVs in a large cohort of 383 OACs with paired whole transcriptome sequence (WTS) in a subset (n = 214). Coupled with detailed clinical annotation, this analysis has enabled us to establish the functional relevance of the driver genes affected by these rearrangements.

Results

Rearrangement patterns in OAC genomes show frequent mobile element insertions and complex SV

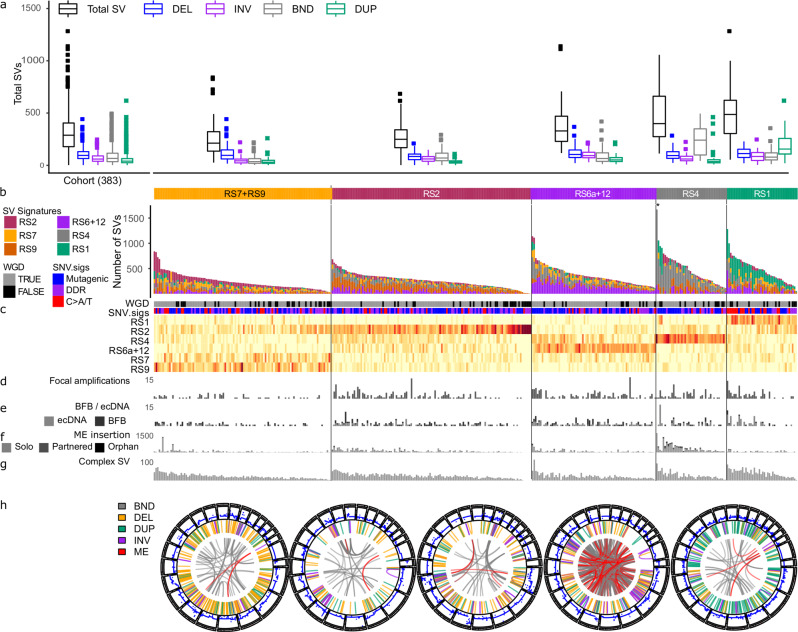

We analysed 383 OAC genomes and observed a wide variation in the numbers of structural variants (SV) between cases, with a predominance of deletions (DEL), inter-chromosome junctions (BND) and tandem duplications (DUP) (Fig. 1a). The SV were deconvoluted into rearrangement signatures (RS, Supplementary Fig. S1A) by combining the types of SVs with the size and degree of clustering2,23, mapped to known signatures (Supplementary Fig. S1B)24 and clustered to show distinct profiles of rearrangements in different groups of patients (Fig. 1b, c, Supplementary Fig. S2A, Supplementary Data 1). Six RS were identified: two with DEL sizes of 1–10 kb and 100 kb–1 Mb (signatures RS7 and RS9, respectively); a non-clustered inter-chromosomal junction (BND) (RS2) and a clustered inter-chromosomal junction signature (RS4); and a clustered SV signature with a high number of DELs, INVs, and DUPs of size 1–10 Mb, corresponding to a combination of signatures (RS6a and RS12) and a non-clustered 100 kb–1 Mb DUP signature RS124. We identified a lower burden of focal amplifications and extrachromosomal DNA (ecDNA) cycles in the RS7 + RS9 group (p = 0.0056, p = 0.0061, respectively, Wilcoxon rank sum test, Supplementary Fig S2B, C), an enrichment of mobile element (ME) insertions in the RS4 group (p = 4 × 10−11) and complex clusters of SVs in the RS1 group of patients (p = 8.2 × 10−7, Fig. 1d–g, Supplementary Fig. S2B–G).

Fig. 1. Classification of OACs according to the proportions of SV types and signatures.

Tumours are shown classified into groups according to their predominant SV signature defined by Nik-Zainal et al. (2016). a Box plot showing numbers of SVs by SV type for the entire cohort and in each group (named after the simplest rearrangement that could generate such a junction, DEL: deletion, INV: inversion, BND: ‘breakend’, i.e. an inter-chromosome junction or translocation, DUP: tandem duplication). b Bar plots of rearrangements associated to each rearrangement signatures in OAC. c Heatmap showing proportions of SVs associated to each signature and a comparison with related variables: whole genome doubling (WGD), SNV signature classification (Mutagenic, DDR and C > A/T) described by Secrier (2016), d focal amplifications, e number of BFB and ecDNA cycles, f number of mobile element insertions and g complex SV clusters. h Circos plots of representative tumours from each signature group with ME insertions highlighted in red. *Denotes tumour with >2500 SVs excluded from plot.

To determine the contributions of ME insertions in generating SVs in OAC, we used the TraFic algorithm11,13, which identified a median of 60 (IQR 3–117) ME inserts per tumour (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Data 2). The majority of inserts (81%, 37,475) were of LINE-1 sequence alone (‘solo’), while 19% (8517) included transduced 3′ flanking sequence. Of these 7% (3195) retained LINE1 sequence, while 12% (5322) were ‘orphan’ transductions, i.e. transduced sequence alone (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Data 2). Since transduced sequence reveals the origin of the LINE-1 in the genome, we could assign 13% (6109) to germline elements and, remarkably, 5% (2408) to novel, somatically acquired elements. In the tumours with the highest numbers of inserts, the active germline LINE-1s were generally those described by Rodriguez-Martin et al. as ‘Plinian’, i.e., rarely present but with high activity when activated. This is in contrast to the ‘Strombolian’ germline LINE-1 elements, which are frequently active in cancer and tend to be active in tumours with fewer inserts3,11. We also identified ME insertions among our conventional SV calls and as most are inter-chromosomal, most resemble translocations. Hence, there were 13,189 inter-chromosomal junctions that had at least one breakpoint overlapping with a ME called by TraFic in the sample (Supplementary Data 2).

Rearrangement signatures in OAC correspond to processes leading to ME insertions, DNA damage repair and complex rearrangements

To identify the features of biological processes associated with each RS, we carried out a logistic regression based on the presence of each RS in each tumour and orthogonal features including the number of ME insertions; chromothripsis events, complex SV clusters, SNV signatures subtypes10, BFB or ecDNA events numbers and in known driver genes (Supplementary Data 3).

RS4, a signature of unknown aetiology consisting of clustered inter-chromosomal junctions (affecting 74% of cases), was strongly associated with the number of ME insertion events (log odds: 6.13, p = 3.21 × 10−9, Supplementary Data 4). We further determined if each inter-chromosomal junction cluster overlapped with nearby ME insertions or source elements and found 59% (1622/2751) of RS4 clusters overlapped with ME insertions—41% called by TraFic, while the remaining 18% of RS4 clusters overlapped with regions with previous evidence of transductions by MEs11,13 (Supplementary Data 5). We also identified an association with the number of ecDNA amplicons (log-odds = 0.46, p = 0.009, Supplementary Data 4) and increased KRAS expression (log odds 0.54, p = 5.47 × 10−4, logistic regression, p = 0.026, Wilcoxon rank sum test) in tumours with RS4, driven by tumours (15/19) with both ME insertions and KRAS amplification (Supplementary Fig. S2H, Supplementary Data 6). In addition, RS4 was associated with a lower expression of Leucine Rich Repeat Kinase 2 (LRRK2), a gene with interactions with ATM and roles regulating MDM2 and TP53 in DNA repair pathways25 that was previously identified14 (log odds = −0.99, p = 4.91 × 10−4, Supplementary Data 4). In addition, we observed that tumours with RS4 had an increased frequency of SVs in genomic regions containing MDM2, H3F3B, PTPRB and GRM3 compared to tumours devoid of RS4 (Supplementary Fig. S2I).

Signature RS2 (87%) was associated with a lower number of ecDNA amplicons involving ERBB2 (log odds −0.89, p = 0.033, FDR = 0.051, Supplementary Data 4). Tumours with a high proportion of SVs assigned to RS2 have a low burden of SV events (p = 0.0181, Wilcoxon rank sum test, Supplementary Fig. S2A) and are genomically stable compared to other tumours.

The deletion signature, RS7 (69%) was associated with an absence of ME insertions (log odds = −1.53, p = 2.85 × 10−8) and a higher burden of the SNV signature SBS17a (log odds = 0.55, p = 3.33 × 10-6). RS9 (68%) was associated the presence of the DNA damage response (DDR) phenotype based on SNV signatures described by Secrier et al. 10 (log odds 1.41, p = 1.71 × 10−4) and a lower number of ecDNA cycles affecting the cell cycle regulator Cyclin E1 (CCNE1, log odds = −1.14, p = 0.025, Supplementary Data 4).

Signature RS1 (47%) was associated with ecDNA events encompassing (log odds 3.28, p-value = 0.004, logistic regression, Supplementary Data 4) and increased expression of CCNE1 compared to other tumours (log odds 0.88, p-value = 1.55 × 10−4, logistic regression, Supplementary Data 4, p = 7.5 × 10-7, Wilcoxon rank sum test, Supplementary Fig. S2J). Tumours with RS1 were associated with an absence of ecDNA spanning CDK6 (log odds −1.18 p = 0.008) and low ME insertions (−1.14, p = 2.55 × 10-4, Supplementary Data 4). RS1 corresponded to the tandem duplication phenotype signature, associated with high CCNE1 expression (p = 3.6 × 10−6, Wilcoxon rank sum test, Supplementary Fig. S2J) and replication stress, previously reported in breast, ovarian, stomach and liver cancer2,26–28

The ‘clustered’ signature RS6a + RS12 (69%) was associated with complex SV including a higher number of ecDNA and BFB cycles (log odds = 0.47, p = 0.003, log odds = 0.69, p = 9.19 × 10−5, respectively). Complex rearrangements consisting of clustered inversions and foldback inversions made up 20% of SV clusters associated with RS6a + RS12, and many additional clusters containing larger complex events (Fig. 1e, g).

Five example tumours are shown, respectively, with a high proportion of predominant deletions (RS7 + RS9); non-clustered SVs (RS2); densely clustered SV inversions (RS6 + 12); inter-chromosomal junctions overlapping LINE-1 ME insertions (RS4) and clusters of tandem duplications (RS1) (Fig. 1h).

Complex SVs involving known oncogenes in OAC can be explained by ecDNA amplicons

Complex clusters of rearrangements are thus a prominent feature in OAC and we sought to identify clusters which are likely due to the formation of BFB cycles consisting of foldback inversions and circular ecDNA events that alter known oncogenes. We identified ecDNA events by applying the Amplicon Architect tool15, that starts from regions estimated by CNVKit29 to have an absolute copy number > 4.5 and segment size > 50 kbp and searches for additional regions in the genome that are joined to form an amplicon. As ecDNA events can arise from BFB events and Amplicon Architect identifies BFB, BFB-linked cyclic amplicons and cyclic amplicons, we grouped these events as BFB or ecDNA amplicons. We identified 507 BFB or ecDNA amplicons, of which 58.2% (295) encompassed oncogenes known to be drivers in OAC, accounting for 22% of complex SV clusters overlapping a known oncogene (Supplementary Data 5). Among these ecDNA or BFB events, at least 13 showed inclusion of regions with H3K27Ac marks (p = 0.0002, regioneR30, permutation test) identified in OAC cell lines and tumours31 and devoid of genes—most notably, 4 enhancer elements on chromosome 17 amplified and part of amplicons involving CDK12, ERBB2, RNF43 and CLTC (Supplementary Data 7, Supplementary Fig. S3).

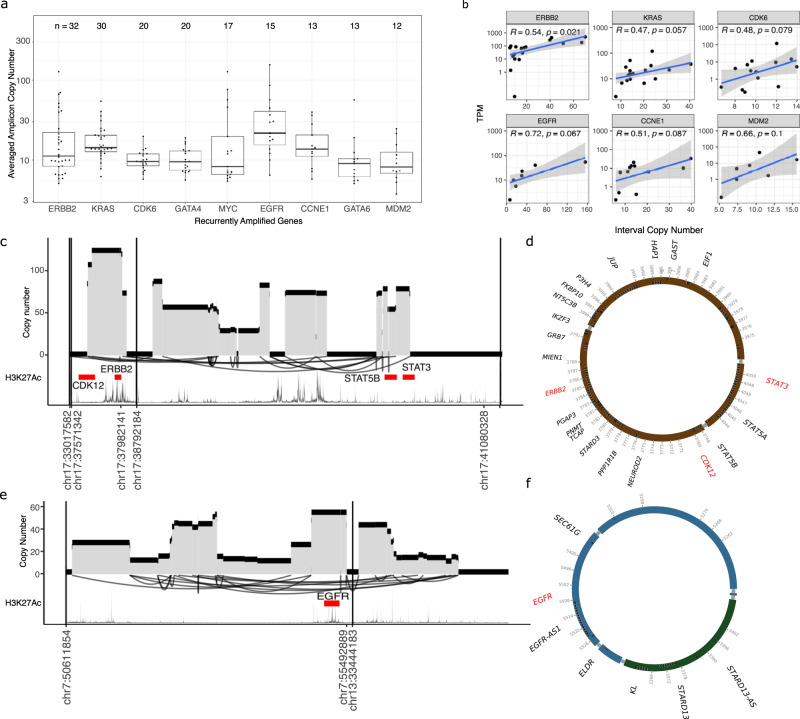

Known driver genes in OAC were recurrently amplified through BFB or ecDNA amplicons, with 35.5% (136) patients having one or more amplicons encompassing ERBB2, KRAS, CDK6, GATA4, MYC, EGFR, CCNE1, GATA6 or MDM2 (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Data 8). Amplicons showed a wide variation of copy number (median CN = 12, IQR 7.9–19.1) and positive correlation (Pearson’s correlation = 0.42, p = 2.993 × 10−5) with high gene expression (Fig. 2b). In addition, several likely driver genes were co-amplified in large complex amplicons, notably CCR7, and/or RARAco-amplified with ERBB2 (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. S3); and AKAP9 and/or GATAD1 with CDK6 (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Fig. 2. Complex SVs leading to amplification of oncogenes.

a Recurrent amplicons detected by Amplicon Architect associated with known OAC oncogenes. The number of tumours with detected amplicon is shown above. Y-axis showing copy number of segments spanning each gene, averaged along the length of segment. b Correlation of gene expression (TPM) and copy number of amplicons. c Example of an amplified region spanning CDK12, ERBB2, STAT3 and STAT5B, resembling ecDNA and d Reconstructed amplicon as an extrachromosomal circle containing ERBB2 and a CDK12-STAT5B fusion. e An amplified region spanning EGFR and joining chromosomes 7 and 13, forming an ecDNA and reconstructed as a circle (f).

It is instructive to consider individual cases. For example, in a tumour with 28 SV breakpoints in two clusters around the highly amplified CDK12-ERBB2 (copy number = 115) and STAT5B-STAT3 (copy number = 72) loci, reconstruction suggested there were multiple ecDNA circles or segments carrying either ERBB2 or STAT5B alone, plus some carrying both amplicons (copy number = 25). The combined structure was consistent with a circular ecDNA structure (Fig. 2c, d) that included two clusters of enhancers (hg19/chr17:37773759-37939651, chr17:39768677-39852129). The enhancers were identified in publicly available OAC tumours and OAC cell lines data31 and the ecDNA encoded a CDK12-STAT5B fusion, that was confirmed using RNA sequencing. Similarly, an EGFR-SEC61G fusion previously predicted from DNA sequencing in a PCAWG study22, proved to be in an EGFR amplification that was part of a cyclical ecDNA with enhancer marks on both chromosome segments (chr13:33846776-33860433, chr7:55132499-55154521, Fig. 2e, f).

Identifying SVs in OAC driver events

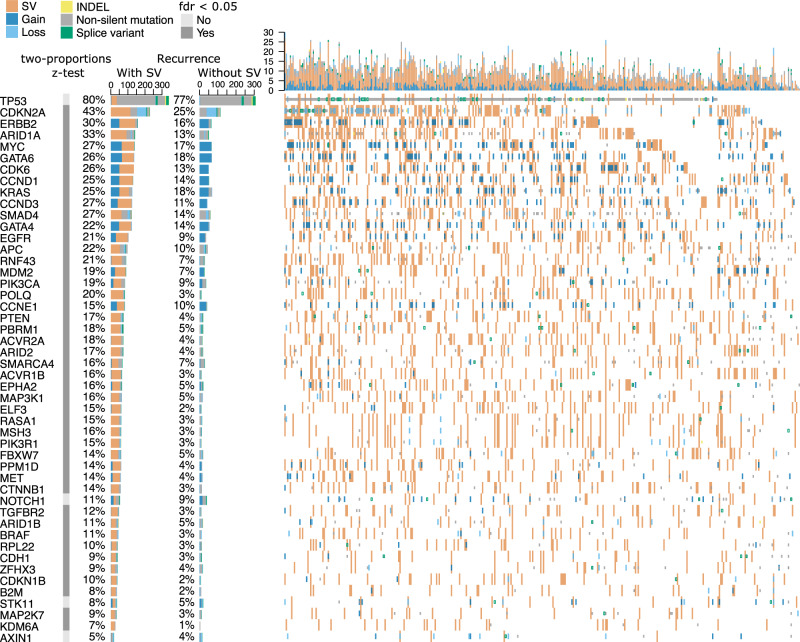

To assess the contribution of SVs to driver events we first considered genes that we had previously identified to be targets of SNV, indel, amplification and deletion driver events3,14. We identified likely additional driver events due to SVs where the interval between two breakpoints overlapped an exon or exons of known driver gene. Adding these SV events substantially increased the recurrence rates of known drivers. For example, among major tumour suppressors, recurrence CDKN2A increased from 25% to 43% and SMAD4 from 14% to 27%, PTEN from 4% to 17% and APC to from 10% to 22% while TP53 showed a predominance of SNV alterations (Fig. 3, Supplementary Data 9).

Fig. 3. Estimates of recurrence in known driver alterations with and without SVs.

Oncoplot showing recurrence of known OAC driver gene mutations (taken from Frankell et al., 2019 and Campbell et al., 2020) with and without SV. Estimates of recurrence without SVs includes copy number gains and losses, INDELs and SNVs. Recurrence with SVs are counted when the interval between two breakpoints overlaps with exon or exons of the gene. Two-proportions z-test with multiple hypothesis testing (FDR) used to test if recurrence is significantly higher with SVs included.

We carried out a two-proportionsz-test to compare the recurrence of all 48 canonical drivers (p-value = 2.2 × 10−16) and in each individual gene, with and without considering SVs. Aside from four genes (TP53, AXIN1, NOTCH1, STK11) known to be affected by SNVs, 44 out of 48 genes show a significantly higher recurrence when SVs are considered (Supplementary Data 9).

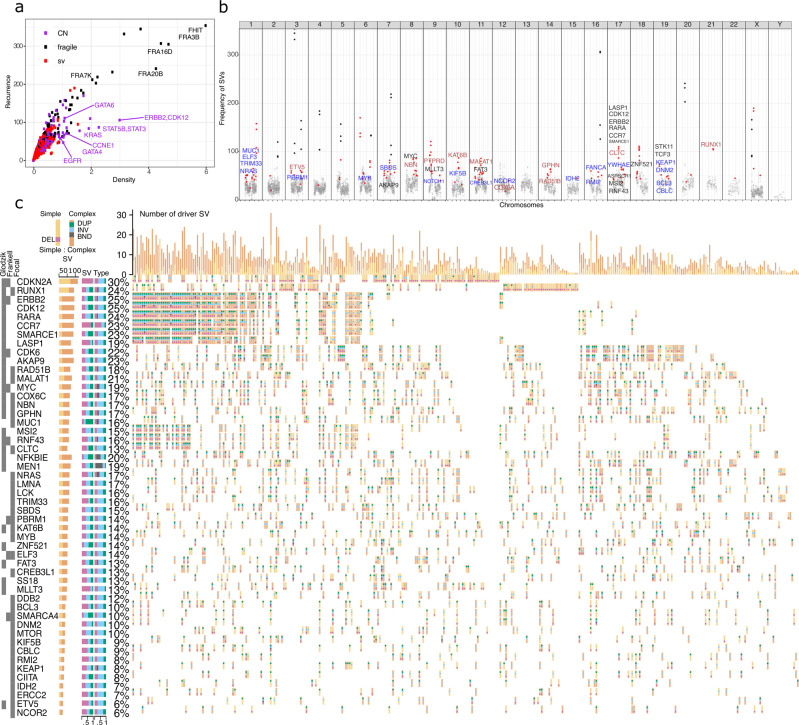

Next, we attempted to identify OAC driver genes affected by SVs, or “hotspots”, characterized by more frequent breaks per unit of genome (1 Mb bins, 500 kb overlapping), after removing known fragile sites, and regions flanking amplicons and deletions. By comparing the recurrence and density of SVs in each hotspot, we identified that fragile sites and copy number altered hotspots obscured driver genes affected by SVs and selected a method that adjusts for CN alterations and other genomic context (Fig. 4a). We identified hotspots in two steps, the first using a previously published method that accounts for genomic context32. Secondly to find focal SVs, we used a consensus approach where bins had to be identified in at least two of the following methods: (1) background distribution modelling of SVs in a whole-genome, (2) per-chromosome context and (3) rank-sumk-means clustering (see the “Methods” section). We further required that the genes to be listed as cancer-relevant by the CGC/COSMIC database.

Fig. 4. Recurrence and density of SVs in 1 Mb genomic bins.

a Scatter plot showing recurrence, the number of patients with an SV break in each 1 Mb bin (y-axis) and density, the average number of SV breaks in the bin over all tumours (x-axis). Bins are labelled with genes or fragile sites that they overlap: black, fragile sites; purple, intervals of amplification and deletion; red, putative genes under selection. b Manhattan plot showing 1MB bins containing putative drivers (red) and fragile sites (black) and genes coloured by methods discovered: Glodzik model adjusting for genomic context (Black), Focal (F, blue) and both methods (brown: FG). c Oncoplot showing candidate driver genes identified using focal and Glodzik methods and annotated if each gene was found in Frankell et al. (2019). Horizontal bar plots show total number of simple (light orange) and complex (dark orange) SVs found in the given gene; proportions of SVs classified as simple that are of the various SV types; and similarly for SVs classified as complex. Each oncoplot cell shows if each patient has a simple or complex SV and the combination of SV types.

A total of 108 regions (1 Mb bins, or groups of adjacent bins) with frequent breaks were identified in either the genomic-context dependent model or focal approach and 41 regions contained known COSMIC genes (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Data 10). These included bins containing RUNX1, MALAT1, RAD51B, COX6C, GPHN, NBN, KAT6B, CLTC, ETV5 and PTPRD that were identified by both approaches (Fig. 4b, c, Supplementary Data 10, 11). We noted that PTPRD and GPHN were identified as genes in possible fragile sites33,34 and excluded them from further analyses. As the COSMIC genes present in hotspots might not be directly affected by SVs, we narrowed down driver gene candidates using the criteria of the SV spanning or overlapping the gene by intersecting the genomic region between the start and end position for intra-chromosomal SVs and between the start and end of both breakpoints in an inter-chromosomal breakend (defined by MANTA) with exons of a gene. Sixty-one candidate genes were identified with RUNX1 as the most recurrent deleted as many of the SVs in the regions overlapped the gene (Fig. 4b, c), and this is discussed in detail below.

Aside from RUNX1, CDKN2A, BCL3 and MYB were identified, with predominant focal deletions affecting CDKN2A and duplications affecting BCL3 and MYB (Supplementary Fig. S4). The MYB proto-oncogene, originally found as the retroviral oncogene myeoloblastosis B, is a driver not previously identified in OACs through SNV and CN analyses. Duplications overlapping MYB span the gene and the evidence of ecDNA events in four patients (CN = 5–45) support its role as an oncogene as identified in other cancer types.

Of the candidate genes identified, 10 were already known as OAC drivers, leaving 51 candidate SV OAC drivers (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Data 11). We classified each rearrangement using ClusterSV1 as simple (a single rearrangement not belonging to a cluster) or complex (multiple rearrangements forming a cluster) and the type of alteration. To accurately estimate the prevalence of rearrangement overlapping with each gene, we identified intra-chromosomal regions spanning each pair of breakpoints and the genes lying within each region. This was done to capture oncogenes which are generally comprised within breakpoints in SVs that lead to amplification (i.e, DUPs, INVs or BNDs) or deletion (mainly DELs). A clear pattern emerged where simple alterations affected tumour suppressors genes including CDKN2A, ARID1A, SMAD4 and RUNX1, while complex clusters tended to affect oncogenes (ERBB2, CDK6, GATA4, GATA6) often involving amplifications (Fig. 4c). In addition, breaks within known tumour suppressor genes CDK12, ZNF21 and RNF43 were observed (Figs. 2c, 4c) and have been shown to result in loss in function (Supplementary Fig S4).

We curated genomic regions identified in our SV driver analysis without COSMIC genes and identified an additional 15 genomic bins containing 31 putative driver genes. These genes overlap with several OAC specific driver genes (GATA6, MUC6) previously identified14. In addition, drivers reported in other cancer types (PVT1, THADA and YES1) and ion channel genes (CACNG1, CACNG4, CACNG5, KCNB1, KCNS2, KCNK6) were identified to be preferentially affected by SVs (Supplementary Data 12).

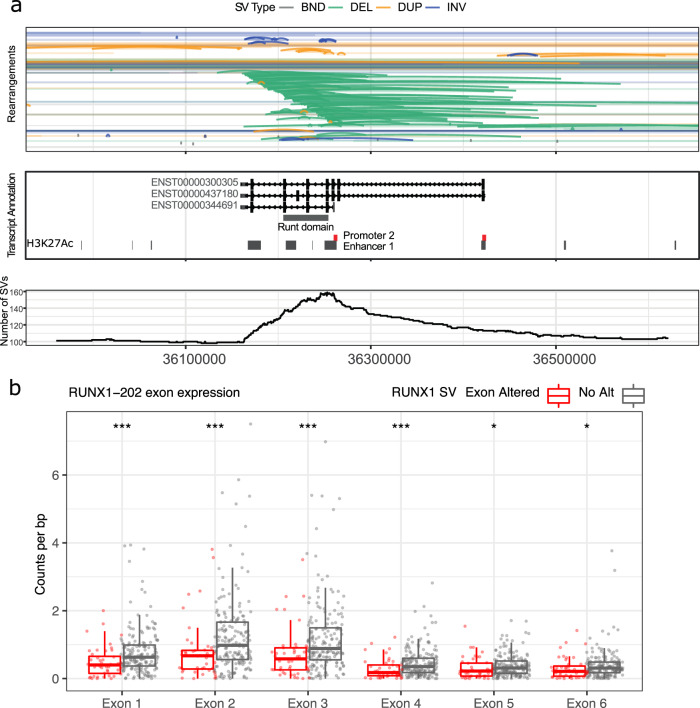

RUNX1 is frequently disrupted by internal deletion of exons

RUNX1 was a candidate for a recurrent OAC driver (24% of patient samples, 92/383), uniquely affected by SVs, a known target of inter-chromosomal translocations in leukaemias, that has been shown to play a role either as an oncogene or TSG in a variety of cancer types35–37. It was previously reported as commonly deleted in OAC10,38, with a likely role as a tumour suppressor39,40.

RUNX1 was most commonly affected by simple SVs (60 patients) while 32 patients had complex SVs. The simple SVs comprised deletions (n = 53 events), duplications (n = 14) and inversions (n = 1) (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Data 11). To understand the biological effects of the RUNX1 deletions, we used data obtained from GTEX and RUNX1 isoform expression in our cohort (Supplementary Fig. 5A) to identify the most expressed transcript (ENST00000344691) for the RUNX1 locus and showed that the most frequently deleted regions encompassed one or more of three features: an enhancer element (chr21:36250083-36262951, 65 patients), three exons (ENSE00002454902, ENSE00003519701 and ENSE00001380483, 61 patients) that code for the Runt DNA binding domain, and the promoter 2 sequence (58 patients) (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Data 13). The loss of expression of the deleted exons 1–4 were observed significantly in transcriptomic sequencing compared to unmutated tumours (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. S5B). In addition, we observed that patients with promoter 2 loss have RUNX1 expression abolished while patients with exon deletions do not show significant difference in expression compared to unmutated tumours (Supplementary Fig S5B, C).

Fig. 5. Deletions and duplications in RUNX1 affecting RUNT domain exons.

a Genomic regions with SVs at the RUNX1 locus (arcs) with cumulative numbers of SV intervals at each position (bottom). RUNX1 is transcribed from the negative strand. RUNT domain and enhancers, from H3K27Ac data, in grey, and promoters in red. b Exon expression of RUNX1-202 (ENST00000344691) for with tumours with alterations in RUNX1 (red) and no alterations (grey). Read counts were normalized to length of exons. *, *** denotes p ≤ 0.05 and p ≤ 0.001 respectively. Gene structure for RUNX1-202 shown as it was determined to be highest expressed transcript by GTEx and in the cohort of 214 tumours. No transcription from promoter 1 was detected.

We investigated the consequences of SVs for RUNX1, using PCR to confirm the genomic junctions, in 69 sequenced tumours as well as in two OAC cell lines, FLO-1 and OE3341. DNA was available for 17 tumours with a total of 22 RUNX1 SVs, and 20/22 (91%) were verified by PCR and Sanger sequencing, as were 3 SVs in the two cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S5D, Supplementary Data 14).

Strikingly, many of the verified SVs were predicted to preserve the reading frame of RUNX1, and encode a protein with absent or modified Runt domain. Most of the individual verified SV calls, 18 of 23 (including 2 of 3 SVs in cell-lines), were internal deletions or duplications that removed or duplicated exons; at least 17 of these 18 were predicted to preserve reading frame; and 15 would encode a protein with absent or modified Runt domain.

Discussion

In this study, we identified rearrangement signatures and processes that shape the mutational and structural landscape of OAC. These encompass known DNA damage related processes including replication stress, complex rearrangements and a signature of unknown aetiology, associated with ME insertions. We estimated the contributions of ME insertions to the signature as multiple processes can result in clustered inter-chromosomal junctions. By assigning the clusters of inter-chromosomal junctions back to RS4, we found that 59% of clusters had evidence of ME insertions within the cluster. The reactivation of ME has been observed in multiple cancer types and previously been shown to associated with amplifications and deletions, most notably in CDKN2A11 and BFB events. We found that ME activity in our cohort was mainly of the Plinian type leading to a large number of retrotranspositions. Recently, expression of transposable elements has been associated to DNA damage and immune response in cancer42 with possible implications for targeted therapies in OAC.

Complex rearrangements were shown to be prominent in OAC in previous studies3,9,10 and we estimated the contributions of ME insertions and ecDNA amplicons in generating complex rearrangement clusters. The evidence of BFB cycles and ecDNA accounting for 22% of complex clusters overlapping oncogenes suggest that it is a frequent process resulting in amplifications in OACs that can undergo selection. The high copy number and expression of these amplicons, observation of enhancer hijacking and the co-amplification of multiple cancer associated genes point to a potent mechanism of tumorigenesis, often with well-known oncogenes affected17,43–45. Recently, mechanistic studies have shown that of telomere loss and chromosome bridge formation, generates BFB and micronuclei in in vitro systems46. We speculate that ecDNA can arise from multiple mechanisms in OAC including chromosome bridge formation and via the episomal model that explains the wide variety of BFB-linked and non-BFB linked ecDNA we observed in this study18.

In addition to SV-driven CN gains or losses, we identified the contribution of SVs to the mutational burden of known OAC drivers that would be recurrently affected by rearrangements, compared to SNVs and INDELs14. We adopted conventions from TCGA and ICGC to annotate SV-affecting exons in canonical transcripts of each driver gene for a conservative estimate. Notably, a substantial number of SVs encompass exons, however more work is needed to identify alterations that have strong functional effects such as a loss of protein function seen in RUNX1. The large overlap of candidate driver events with CN gains and losses provides a reliable way to identify patients with driver gene alterations, but poses challenges in the clinical interpretation of copy neutral variants due to inversions and translocations.

Our results suggest that, for heavily rearranged tumours, current approaches based on targeted gene panels may miss a substantial number of driver gene alterations despite inclusions of large deletions and amplifications and more work is required to identify events that are clinically relevant. For the driver genes affected by SVs, we observe that 37% are affected by gains, 33.3% losses and 4.9% have fusions involving a driver gene in either fusion partner. In addition, fusions are more likely to be associated with copy number gains (3.8%), compared to copy neutral fusions (0.4%) and losses (0.7%), The increased frequency of fusions associated with gains is likely influenced by the rearrangement process generating the SV, such as the formation of ecDNA. Overall, our findings are in keeping with the literature which suggest that fusions in OAC are rare events and few are targetable or clinically relevant.

It remains the case that there are substantial challenges for identifying and prioritizing driver genes within SVs including: (1) gene dosage effects are hard to estimate as complex CN changes such as whole genome doubling are present in the majority of tumours; (2) complex SVs affecting driver genes can encompass large regions with multiple passenger genes implicated; and (3) downstream effects of SV events are hard to determine and need to be validated experimentally. In our analysis we focused on driver genes in OAC and other cancers, as these genes often coincide with the recurrence of SVs within a large genomic region. We used additional evidence such as the patterns of SVs, focal deletions and duplications spanning the gene to identify the driver gene affected by SVs.

We have further identified regions in the genome with a high recurrence or density of SVs that were likely to undergo selection. The analysis recapitulated driver genes identified previously in OAC and pan-cancer studies1,4,14. Several drivers including AKAP9, CDK12, RARA, CCR7 were associated in co-amplification of regions that were part of BFB and ecDNA while MYB was identified in breast and OAC to be affected by amplification in coding regions. BCL3 has been previously identified as a transcriptional activator in leukaemias and has recently been shown to activate an array of pathways including WNT and NFKB47. RUNX1 was mainly affected by CN loss and rearrangements.

Our analysis of RUNX1 rearrangements suggests that the most frequent events in OAC either result in promoter loss or remove or duplicate internal exons, so that a RUNX1 protein would still be encoded but with the RUNT domain disabled—the domain that mediates DNA binding and heterodimerisation with other transcription factors35. Although RUNX1 mutations and rearrangements have been described in OAC39,48,49 and other carcinomas35,50,51 to our knowledge this consequence of mutation has not been noted before, except in a single example of an in-frame deletion of genomic exon 6 in the breast cancer cell line HCC193750. Our data suggest that mutations of RUNX1 in OAC, and perhaps in other carcinomas, are change-of-function, rather than simple gain or loss-of-function. There are, however, tumours that appear to have simply lost RUNX1 activity, so RUNX1 may be altered in a variety of ways, reflecting RUNX1’s role as a master regulator of cell fate, with ability to interact with various other transcription factors and chromatin modifiers35,36.

Our analysis provide evidence for the processes leading to heavily rearranged genomes which are a hallmark of OAC. In addition, these rearrangements confer varying degrees of selective advantage and different evolutionary trajectories. By understanding the mechanisms underlying the formation of SVs, it is hoped that in the future we can identify patients that have a better prognosis and develop therapy regimes that exploit the same tumorigenic processes.

Methods

Study design, cohort selection and sequencing

Endoscopic biopsies and resection specimens were collected prospectively from 383 oesophageal adenocarcinoma patients, including 83 cases previously included in the ICGC pan-cancer (PCAWG) studies3. Patients were predominantly male (n = 329, 86%), with a median age at diagnosis of 66.8 years (IQR: 59–73.6), and presented at an advanced stage (T3N2 = 56.15%, T3N1 = 47.12%). All cases had an estimated tumour purity of >70%, following expert pathological review and underwent whole genome sequencing by Illumina using 100-150 bp paired end reads with 50-fold coverage for the tumour and 30-fold coverage for the matched germline control. Reads were mapped to the GRCh37/hg19 reference assembly using BWA-mem52 (v0.7.17). Paired end RNA-Seq with 75-bp read length was performed for a subset of 214 tumours that had sufficient material14. The RNA-Seq data were aligned using STAR53 (v2.6.1d) and reads mapped to each gene was counted using the GenomicAlignments54 (v1.20.1) R package using Ensembl release 87 annotation. Transcript per million values (TPM) were calculated and used in logistic regression modelling. Transcript isoform and exon expression quantification were carried using Kallisto55 (0.46.1) and subread56 (v 2.0.3) and normalized using the lengths of transcript and exon, respectively.

Structural variation calling and validation

SVs were called, after alignment with bwa-mem to GRCh37/hg19 (1000 Genomes Project human_g1k_v37 with decoy sequences hs37d5), using MANTA v0.2757, as junctions that resembled deletions (DEL), inter-chromosomal junctions (BND), duplications (DUP), or inversions (INV). We discarded SVs that had any supporting reads in the matched normal; SVs found in a pool of 50 unmatched normals from peripheral blood and 15 samples from distant oesophageal mucosa.

The filtered Manta SV calls were compared to calls made by the ICGC Pan cancer project1,3 which used four other pipelines: dRanger and Snowman (Broad Institute), DELLY (DKFZ), and BRASS (Wellcome Sanger Institute), for the 100 of our oesophageal adenocarcinomas included in the PCAWG project. We identified equivalent calls with mergevcf allowing a 300 base pair difference in coordinates, and each individual pipeline was compared to a consensus sets which included variants called by at least two of the ICGC pipelines. Our Manta pipeline gave a median precision of 0.92, a median sensitivity of 0.89, and a median similarity of 0.82. Alternative sets of equivalent calls were also identified allowing base pair differences of 100 and 500; the F1 score for our Manta pipeline was the highest of all of the five pipelines at all three base pair windows sizes.

We also selected a representative tumour sample and PCR verified 73/91 (80%) randomly selected SVs identified by our pipeline (Supplementary Data 15). Additionally, we verified the breakpoints in the coding sequence of two recurrently rearranged genes and confirmed the rearrangement in 79% (15/19) and 74% (20/27) of the cases respectively (Supplementary Data 15). For an overview of the analyses and software, see Supplementary Fig. S6.

Mobile element calling

To identify mobile element (ME) insertions independently of SV calling we used TraFiC-mem v1.1.0 (https://gitlab.com/mobilegenomes/TraFiC)11,13 with the MEIBA (https://github.com/brguez/MEIBA/tree/master/src/python) module to give base-pair resolution, and discarding inserts that lacked the expected poly-A tail. These inserts were used to annotate BNDs as ME insertions if either breakend directly overlapped with insert regions. In addition, breakpoints in sequences known to be transduced by LINE-1 mobile elements12,13 were marked as likely mobile element insertions.

Classification of SV footprints and rearrangement signature analysis

We classified SVs into footprints by identifying clusters as described1 using the ClusterSV R package (https://github.com/cancerit/ClusterSV). In addition, clusters of ME transductions were defined as clusters containing BNDs with at one breakpoint overlapping with ME insertions. We then set aside with ME footprints and classified the remaining SVs as simple or complex rearrangements after excluding centromere and telomere regions.

Rearrangement signatures (RS) were extracted using the Palimpsest 1.0.0 R package23, Palimpsest was run for 1000 iterations for from 2 to 10 signatures, and six signatures were selected based on cophenetic and silhouette scores. We matched the extracted signatures to reference rearrangement signatures24 from Signal (https://signal.mutationalsignatures.com/, Supplementary Fig S1A, B). We clustered patients based on the exposures of the extracted SV signatures using the ConsensusClusterPlus58 (v1.46.0) R package. The final number of clusters (K) was chosen using the calcICI function with the K = 6 selected, based on the highest mean consensus score.

Chromothripsis, extrachromosomal amplicons and break–fusion-bridge events

Chromothripsis was identified as complex SV events with oscillating copy number changes, using ShatterSeek v0.421, and classified as high confidence (≥7 segments with oscillating copy number) or low confidence (4–6 segments) as recommended.

Regions resembling extrachromosomal amplifications or breakage–fusion-bridge cycles were identified using AmpliconArchitect v1.215: amplifications of size 50 kb, copy number > 4.5 were reconstructed using CNVKit29 v0.9.8 called copy number segments. Amplified segments were refined with the amplified_intervals.py script. AmpliconArchitect was run using the clustered mode to identify extrachromosomal regions with driver gene amplifications and fold-back events associated with breakage–fusion-bridge cycles.

Rearrangement signature features and regression

To identify features associated to each RS, we carried out logistic regression using the glm function in R (stats R package) based on the presence of each RS as response and predictors including: number of ME insertions, chromothripsis events, complex SV clusters, mutations attributed to SNV signatures extracted using SigProfilerExtractor v1.1.059 listed by the COSMIC database60, mutational signature subtypes10, total BFB or ecDNA events and gene expression of known driver genes (Supplementary Data 3).

We log transformed and scaled the counts from the predictors. For each RS, predictors from the univariate analysis with p < 0.05 were used to build a multivariate model, refined with stepAIC (MASS R package, version 7.3-51.1) and FDR correction was done on the final model. In addition, we carried out a hold-out validation of 10 replicates each using 80–20, 60–40 and 40–60 split of the cases with each signature and observed that positive associations between RS4-ME events, RS9-DDR subtype, RS6 + 12-BFB, RS7−SBS17a and negative associations between RS1-ec_CDK6, RS7-ME events were robust throughout each hold-out validation (Supplementary Data 16). A separate logistic regression model was built using the RNA-Seq gene expression profiles in SV driver genes (Supplementary Data 4, 11).

In addition, we carried out a correlation matrix analysis on the response and predictors using the rcorr function (Hmisc R package, version 4.2-0) and carried out FDR correction on the final p-values. All associations except for RS9-DDR, RS9-Mutagenic, RS9-CCNE1 and RS2-KIF5B were validated using the correlation matrix analysis (Supplementary Data 4).

Estimating the contributions of SV in known drivers

To estimate the contributions of SV in recurrent drivers, we defined regions between two SV breakpoint called by MANTA and identified SVs with regions that overlapped exons in known driver genes from Frankell 2019 and Campbell 2020. To identify gene isoforms that are likely affected, we used annotations (vcf2maf tool, isoform_overrides_uniprot) from TCGA to select for overlaps in exons present in canonical transcripts of each gene. The predominant isoforms for RUNX1 were obtained from the GTEx database using the oesophagus mucosa and stomach tissue types.

In addition, GISTIC 2.061 was used to identify gains, amplifications, loss or deep deletions in genes in addition to SNVs, INDELS and SV.

Identifying regions of frequent SVs

We divided the genome into 1 Mb bins with 500 kb overlap and calculated breakpoint recurrence, i.e. the number of patients with at least one breakpoint in the bin, and breakpoint density, the average number of breakpoints in each bin across all samples (Fig. 3a).

To estimate the background SV rate19,32, we modelled breakpoint recurrence in each bin as a negative binomial linear regression, adjusted for the genomic context of each bin: fragile sites, copy number aberrations, GC content, replication timing62, histone methylation marks (H3K36me3 and H3K27ac), DNAseq hypersensitivity, and ALU sequences19. Bins were identified as being significantly recurrently altered if the residuals were ≥2 standard deviations from the mean (Supplementary Data 10).

In order to further characterize bins that may reflect hotspots for SV activity we filtered bins that reflect known fragile sites and high-density regions (434/5597 bins). We then apply three methods to identify focal hotspots and select bins found by at least two methods: (1) model the per-bin SV counts genome-wide under a negative binomial distribution identifying the residual outliers as significant bins, (2) model the per-bin SV counts per-chromosome to account for chromosomal context, and (3) a rank-sum approach where counts are ranked per-patient and summed across each bin and significant bins identified via k-means clustering.

To identify driver genes enriched in tumours with RS4 compared to tumours devoid of MEs (RS7 enriched tumours), we calculated the frequency of tumours with SVs in 1 Mb bins in RS4 and RS7 tumours (93 and 76, respectively) and identified those with a frequency difference of ≥15% between groups. We excluded fragile sites for this analysis.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical tests were carried out using R 3.5.3, with the wilcox.test function for the Wilcoxon rank sum test to associate biological features and each RS (n = RS9:261, RS1:180, RS7:266, RS4:283, RS2:335, RS6a + 12:264) and between RS patient groups (n = RS2:119, RS7 + 9:106, RS6a + 12:74, RS4:42, RS1:42). All reported Wilcoxon rank sum tests p-values are two tailed.

Permutation tests for the enrichment of H3K27AC enhancer elements in ecDNA regions were carried out using the regioneR30 package and overlapPermTest function with 5000 permutations. Two proportions z-test to compare recurrence of driver genes (n = 383) was carried out using the prop.test function with the alternative = ‘greater’ parameter, followed by multiple testing correction using p.adjust(method = ‘fdr’).

Reporting summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Jens Luebeck and Vineet Bafna (UCSD) on their help with Amplicon Architect and suggestions on the ecDNA analysis. We sincerely thank Sonia Zumalave and Jose Tubio (USC) on their kind help to run the TraFic workflow and comments on the manuscript. We thank the Human Research Tissue Bank, which is supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, from Addenbrooke’s Hospital. This research was supported by the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC-1215-20014). The laboratory of R.C.F. is funded by a Core Programme Grant from the Medical Research Council (RG84369). OCCAMS was funded by a Programme Grant from Cancer Research UK (RG66287). OCCAMS2 was funded by a Programme Grant from Cancer Research UK (RG81771/84119).

Author contributions

R.C.F., P.A.W.E. and G.C. conceived of the study. A.W.T.N., G.C., S.K., G.D. and J.S. carried out the analyses of the genomic data and statistical analyses. G.C., P.A.W.E., R.H. and S.A. designed and carried out the validation experiments. R.C.F., P.A.W.E. and S.T. supervised the research. G.D., J.M.J.W. and M.D.E. developed and maintained the genomics pipelines processing the WGS and RNA-seq data. A.M.R. coordinated the data collection. R.C.F. and S.T. obtained funding. R.C.F., A.W.T.N., P.A.W.E. and G.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Ruping Sun and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Brooke LaFlamme.

Data availability

The sequencing data included in this study have been submitted to European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA; https://ega-archive.org/) under the accession numbers EGAD00001007808 (WGS) and EGAD00001007809 (RNAseq), respectively.

Code availability

R scripts used in the analyses are available on GitHub (https://github.com/fitzgerald-lab/Rearrangements-in-OAC).

Competing interests

R.C.F. has devised an early detection technology called Cytosponge, this device technology and the associated TFF3 biomarker are licensed to Covidien GI solutions (now owned by Medtronic) by the Medical Research Council. R.C.F. and M.O. are named inventors on patents pertaining to the Cytosponge and associated technology. R.C.F. is a shareholder of Cyted Ltd., a company working on early detection technology. R.C.F. has received consulting and/or speaker fees from Medtronic, Roche and Bristol Myers Squibb. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Alvin Wei Tian Ng, Gianmarco Contino.

A list of authors and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

Contributor Information

Rebecca C. Fitzgerald, Email: rcf29@cam.ac.uk

Oesophageal Cancer Clinical and Molecular Stratification (OCCAMS) Consortium:

Nicola Grehan, Barbara Nutzinger, Elwira Fidziukiewicz, Adam Freeman, Elizabeth C. Smyth, Maria O’Donovan, Ahmad Miremadi, Shalini Malhotra, Monika Tripathi, Calvin Cheah, Hannah Coles, Connor Flint, Matthew Eldridge, Maria Secrier, Sriganesh Jammula, Jim Davies, Charles Crichton, Nick Carroll, Richard H. Hardwick, Peter Safranek, Andrew Hindmarsh, Vijayendran Sujendran, Stephen J. Hayes, Yeng Ang, Andrew Sharrocks, Shaun R. Preston, Izhar Bagwan, Vicki Save, Richard J. E. Skipworth, Ted R. Hupp, J. Robert O’Neill, Olga Tucker, Andrew Beggs, Philippe Taniere, Sonia Puig, Timothy J. Underwood, Robert C. Walker, Ben L. Grace, Jesper Lagergren, James Gossage, Andrew Davies, Fuju Chang, Ula Mahadeva, Vicky Goh, Francesca D. Ciccarelli, Grant Sanders, Richard Berrisford, David Chan, Ed Cheong, Bhaskar Kumar, L. Sreedharan, Simon L. Parsons, Irshad Soomro, Philip Kaye, John Saunders, Laurence Lovat, Rehan Haidry, Michael Scott, Sharmila Sothi, Suzy Lishman, George B. Hanna, Christopher J. Peters, Krishna Moorthy, Anna Grabowska, Richard Turkington, Damian McManus, Helen Coleman, Russell D. Petty, and Freddie Bartlett

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-022-03238-7.

References

- 1.Li, Y. et al. Patterns of somatic structural variation in human cancer genomes. Nature10.1038/s41586-019-1913-9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Nik-Zainal S, et al. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature. 2016;534:47–54. doi: 10.1038/nature17676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell PJ, et al. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature. 2020;578:82–93. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1969-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabarinathan, R. et al. The whole-genome panorama of cancer drivers. Preprint at bioRxiv10.1101/190330 (2017).

- 5.Ciriello G, et al. Emerging landscape of oncogenic signatures across human cancers. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1127–1133. doi: 10.1038/ng.2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawrence MS, et al. Discovery and saturation analysis of cancer genes across 21 tumour types. Nature. 2014;505:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature12912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martincorena, I. et al. Universal patterns of selection in cancer and somatic tissues. Cell10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.042 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Korbel JO, Campbell PJ. Criteria for inference of chromothripsis in cancer genomes. Cell. 2013;152:1226–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nones K, et al. Genomic catastrophes frequently arise in esophageal adenocarcinoma and drive tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:1–9. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Secrier M, et al. Mutational signatures in esophageal adenocarcinoma define etiologically distinct subgroups with therapeutic relevance. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1131–1141. doi: 10.1038/ng.3659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez-Martin B, et al. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes identifies driver rearrangements promoted by LINE-1 retrotransposition. Nat. Genet. 2020;52:306–319. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0562-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paterson AL, et al. Mobile element insertions are frequent in oesophageal adenocarcinomas and can mislead paired-end sequencing analysis. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1685-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tubio, J. M. C. et al. Extensive transduction of nonrepetitive DNA mediated by L1 retrotransposition in cancer genomes. Science345, 1251343 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Frankell AM, et al. The landscape of selection in 551 esophageal adenocarcinomas defines genomic biomarkers for the clinic. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:506–516. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0331-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deshpande, V. et al. Exploring the landscape of focal amplifications in cancer using AmpliconArchitect. Nat. Commun. 10, 392 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Kim, H. et al. Frequent extrachromosomal oncogene amplification drives aggressive tumors. Preprint at bioRxiv10.1101/859306 (2019)

- 17.Turner KM, et al. Extrachromosomal oncogene amplification drives tumour evolution and genetic heterogeneity. Nature. 2017;543:122–125. doi: 10.1038/nature21356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Storlazzi CT, et al. Gene amplification as doubleminutes or homogeneously staining regions in solid tumors: origin and structure. Genome Res. 2010;20:1198–1206. doi: 10.1101/gr.106252.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Głodzik D, et al. Mutational mechanisms of amplifications revealed by analysis of clustered rearrangements in breast cancers. Ann. Oncol. 2018;29:2223–2231. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadi K, et al. Distinct classes of complex structural variation uncovered across thousands of cancer genome graphs. Cell. 2020;183:197–210.e32. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cortés-Ciriano I, et al. Comprehensive analysis of chromothripsis in 2,658 human cancers using whole-genome sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2020;52:331–341. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0576-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wala, J. A. et al. Selective and mechanistic sources of recurrent rearrangements across the cancer genome. Preprint at bioRxiv10.1101/187609 (2017).

- 23.Shinde, J. et al. Palimpsest: an R package for studying mutational and structural variant signatures along clonal evolution in cancer. Bioinformatics10.1093/bioinformatics/bty388 (2018) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Degasperi A, et al. A practical framework and online tool for mutational signature analyses show intertissue variation and driver dependencies. Nat. Cancer. 2020;1:249–263. doi: 10.1038/s43018-020-0027-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Z, et al. LRRK2 interacts with ATM and regulates Mdm2-p53 cell proliferation axis in response to genotoxic stress. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017;26:4494–4505. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bayard, Q. et al. Cyclin A2/E1 activation defines a hepatocellular carcinoma subclass with a rearrangement signature of replication stress. Nat. Commun. 9, 5235 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Menghi F, et al. The tandem duplicator phenotype is a prevalent genome-wide cancer configuration driven by distinct gene mutations. Cancer Cell. 2018;34:197–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xing R, et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals novel tandem-duplication hotspots and a prognostic mutational signature in gastric cancer. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2037. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09644-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talevich E, Shain AH, Botton T, Bastian BC. CNVkit: genome-wide copy number detection and visualization from targeted DNA sequencing. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016;12:1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gel B, et al. regioneR: an R/Bioconductor package for the association analysis of genomic regions based on permutation tests. Bioinformatics. 2015;32:289–291. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen, L. et al. Master transcription factors form interconnected circuitry and orchestrate transcriptional networks in oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Gut 1–11 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318325 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Glodzik D, et al. A somatic-mutational process recurrently duplicates germline susceptibility loci and tissue-specific super-enhancers in breast cancers. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:341–348. doi: 10.1038/ng.3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bignell, G. R. et al. Signatures of mutation and selection in the cancer genome. Nature10.1038/nature08768 (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Priestley, P. et al. Pan-cancer whole-genome analyses of metastatic solid tumours. Nature10.1038/s41586-019-1689-y (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Ito Y, Bae SC, Chuang LSH. The RUNX family: developmental regulators in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15:81–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blyth K, Cameron ER, Neil JC. The RUNX genes: gain or loss of function in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:376–387. doi: 10.1038/nrc1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mangan JK, Speck NA. RUNX1 mutations in clonal myeloid disorders: From conventional cytogenetics to next generation sequencing, A story 40 years in the making. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 2011;16:77–91. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v16.i1-2.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim, J. et al. Integrated genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature10.1038/nature20805 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Dulak, A. M. et al. Exome and whole-genome sequencing of esophageal adenocarcinoma identifies recurrent driver events and mutational complexity. Nat. Genet. 45, 478-86 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Rheinbay E, et al. Analyses of non-coding somatic drivers in 2,658 cancer whole genomes. Nature. 2020;578:102–111. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1965-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Contino G, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of nine esophageal adenocarcinoma cell lines [version 1; referees: 3 approved] F1000Research. 2016;5:1–12. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7033.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kong Y, et al. Transposable element expression in tumors is associated with immune infiltration and increased antigenicity. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:5228. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13035-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim H, et al. Extrachromosomal DNA is associated with oncogene amplification and poor outcome across multiple cancers. Nat. Genet. 2020;52:891–897. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0678-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Northcott PA, et al. Enhancer hijacking activates GFI1 family oncogenes in medulloblastoma. Nature. 2014;511:428–434. doi: 10.1038/nature13379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Helmsauer K, et al. Enhancer hijacking determines extrachromosomal circular MYCN amplicon architecture in neuroblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5823. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19452-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Umbreit, N. T. et al. Mechanisms generating cancer genome complexity from a single cell division error. Science368, eaba0712 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Legge DN, et al. The role of B-Cell Lymphoma-3 (BCL-3) in enabling the hallmarks of cancer: implications for the treatment of colorectal carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2020;41:249–256. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgaa003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boonstra JJ, et al. Mapping of homozygous deletions in verified esophageal adenocarcinoma cell lines and xenografts. Genes Chromosom. Cancer. 2012;51:272–282. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gu J, et al. Genome-wide catalogue of chromosomal aberrations in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: a high-density single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis. Cancer Prev. Res. 2010;3:1176–1186. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stephens PJ, et al. Complex landscapes of somatic rearrangement in human breast cancer genomes. Nature. 2009;462:1005–1010. doi: 10.1038/nature08645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Banerji S, et al. Sequence analysis of mutations and translocations across breast cancer subtypes. Nature. 2012;486:405–409. doi: 10.1038/nature11154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Dobin A, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2012;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lawrence M, et al. Software for computing and annotating genomic ranges. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013;9:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bray NL, Pimentel H, Melsted P, Pachter L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:525–527. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. The R package Rsubread is easier, faster, cheaper and better for alignment and quantification of RNA sequencing reads. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen X, et al. Manta: rapid detection of structural variants and indels for germline and cancer sequencing applications. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:1220–1222. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilkerson MD, Hayes DN. ConsensusClusterPlus: a class discovery tool with confidence assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1572–1573. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alexandrov LB, et al. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature. 2020;578:94–101. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1943-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tate JG, et al. COSMIC: the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D941–D947. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mermel CH, et al. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R41. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li H. Toward better understanding of artifacts in variant calling from high-coverage samples. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2843–2851. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The sequencing data included in this study have been submitted to European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA; https://ega-archive.org/) under the accession numbers EGAD00001007808 (WGS) and EGAD00001007809 (RNAseq), respectively.

R scripts used in the analyses are available on GitHub (https://github.com/fitzgerald-lab/Rearrangements-in-OAC).