Abstract

Stakeholder advisory boards are recognized as an essential and useful part of patient-centered research. However, such engagement can involve exchanges of diverse individual experiences, multiple opinions, and strong feelings in the face of researchers’ limitations, deadlines, and agendas. Yet, little work examines how these potential tensions occur and are resolved in actual advisory board meetings. This perspective article describes and employs a communication framework for analyzing a patient advisory council (PAC) for a comparative effectiveness study on acupuncture and pain counseling for inpatients with cancer. The framework, Action-Implicative Discourse Analysis (AIDA), is an observational method that examines challenges through recorded and transcribed, naturally occurring interaction. Our analysis focused on two short excerpts from the first PAC meeting to demonstrate members’ navigation of advice-giving and advice-receiving—one in which advice was ultimately implemented by the study team and another in which it was deemed unfeasible. Although advice is inherent to the work of all PACs, it often emerges unannounced as negotiated moments, made up of seemingly minor conversation moves. As a recurring event, advice can and should be analyzed and discussed within PACs to improve communication and team dynamics.

KEY WORDS: acupuncture, pragmatic effectiveness, pain, cancer, implementation, inpatient

Stakeholder advisory boards are recognized as an essential part of patient-centered research.1,2 Valued as a critical strategy to strengthen research relevance, stakeholder engagement is increasingly expected and mandated by some funders, such as the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Projects using advisory boards acknowledge that the advising process is a complex, time-consuming endeavor3,4 often with unmeasured5 or equivocal6 results. Communication and shared leadership,2,4 and co-learning and inclusive decision-making7 are highlighted as critical ways to improve advisory board efforts and achieve the purpose of engaging patients. However, such engagement—the actions or behaviors of patient-centered engagement8—often involves exchanges of potentially diverse individual experiences, multiple opinions, and strong feelings in the face of researchers’ limitations, deadlines, and agendas. Self-report studies acknowledge these challenges,2,4 but to our knowledge, no work has examined real-time interaction of advisory board meetings and how these tensions play out.

The goal of this perspective is to examine advice as one type of common challenge when engaging patient advisory councils (PACs). Long recognized in communication studies as potentially problematic, even conflict-inducing,4,9 advice is valued but not obligatory. Despite best intentions for open communication and inclusive decision-making, PAC members do not conduct the research, nor are researchers fully accountable to use all the received advice. However, establishing trust is still an important goal and challenge.4 To illustrate this problem and how it is managed, we analyze audio-recordings of the first PAC meeting from a PCORI-funded project that explored the effectiveness of two non-pharmacologic approaches to pain management for hospitalized cancer patients, called Pragmatic Research of Acupuncture and Counseling eXtended to Inpatient Services (PRACXIS). In this article, we explain one framework for how to interpret PAC interaction and describe advice as a negotiated process that may be useful in learning to improve PAC meetings in general.

APPROACH

The PRACXIS research team assembled the PAC in June 2018, prior to starting recruitment for the larger study. The PAC comprised ten individuals who either had cancer or was a caregiver of someone with cancer. PAC members had diverse social identities (racial/ethnic, linguistic, and economic) and were invited to elicit a range of perspectives (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Meeting Attendees (n=12)

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (sd) | 50.5 (9.4) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 11 (92%) |

| Male | 1 (8%) |

| Race/ethnicity* | |

| African American/Black | 1 (8%) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (8%) |

| Asian | 5 (42%) |

|

Caucasian/White Latinx Other |

6 (50%) 4 (33%) 2 (17%) |

| Highest level of education | |

| High school or GED | 1 (8%) |

|

Some college College graduate or more |

2 (17%) 9 (75%) |

| Languages spoken* | |

| English | 12 (100%) |

| Spanish | 4 (33%) |

| Cantonese | 1 (8%) |

| Mandarin | 1 (8%) |

| Meeting role | |

| Researcher | 3 (27%) |

| Patient/Caregiver Stakeholder | 9 (73%) |

*Note: Participants could select more than one category; percentages may total >100%

A total of eight quarterly meetings were attended by PAC members and three members of the research team (the PI, study director, and lead clinical research coordinator). One main purpose of the PAC during the planning phases of the study was to provide feedback on study materials used to engage patients of diverse cultural backgrounds and varying levels of health literacy specifically regarding pain counseling. Members discussed their views of the most effective pain counseling techniques and preferences for talking about pain. Sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed with permission from the PAC members as a best practice for sharing suggestions to the full research team.1

After one PAC member (a health communication researcher and cancer patient) moved onto the research team, these data were subjected to a secondary analysis using Action-Implicative Discourse Analysis (AIDA). AIDA is a qualitative, social constructionist method that involves developing arguments grounded in the close examination of naturally occurring talk-in-interaction.10–12 Its goal is to provide insight into similar communication situations so practitioners can start (or maintain) a critical dialogue about wiser and ideal communication practices.

AIDA is a methodology that focuses not just on what people say, but also on how they accomplish activities through talk. In this sense, analysis typically describes communication in terms of practice, activity people do not just enact but also rehearse and critically consider. Thus, AIDA guides researchers to frame interaction as something to think about, debate over, and improve upon.13–15 AIDA can be used to describe situation-specific discourse practices to uncover as-yet unseen interactional challenges,16–19 or to analyze already-known challenges and describe practices communicators employ to manage them.18,20–22 Along with examining numerous practices such as negotiation,23 deliberation,19,21,24 reporting,25 and classroom discussion,26,27 AIDA has been applied to health care contexts17,28,29 and meeting contexts.22,30

Interpretations and descriptions from the AIDA perspective require transcription showing not just talk’s content but also levels of detail such as intonation, pauses, overlapping speech, false starts, non-fluencies, and vocal particles (e.g., “uh,” “mm”).31 Supporting arguments about talk’s accomplishments require pointing to specific moments in the transcription. AIDA’s challenge-orientation guides researchers to moments when interaction becomes difficult, becomes awkward, or needs management. Although advice-giving occurred throughout the dataset, these moments were especially concentrated in the first meeting as researchers introduced the study design, and the group established the tone for advice-giving and advice-receiving. Also at this time, researchers were interested in soliciting feedback from the PAC on certain implementation factors not yet solidified.

AIDA INSIGHTS

To illustrate how AIDA works, we present two contrasting interactions in giving/receiving advice—one in which implementation of advice was possible (albeit difficult) and one in which it was impossible. Examination demonstrates advice as a two-way negotiation process under both circumstances. Pseudonyms are used for confidentiality.

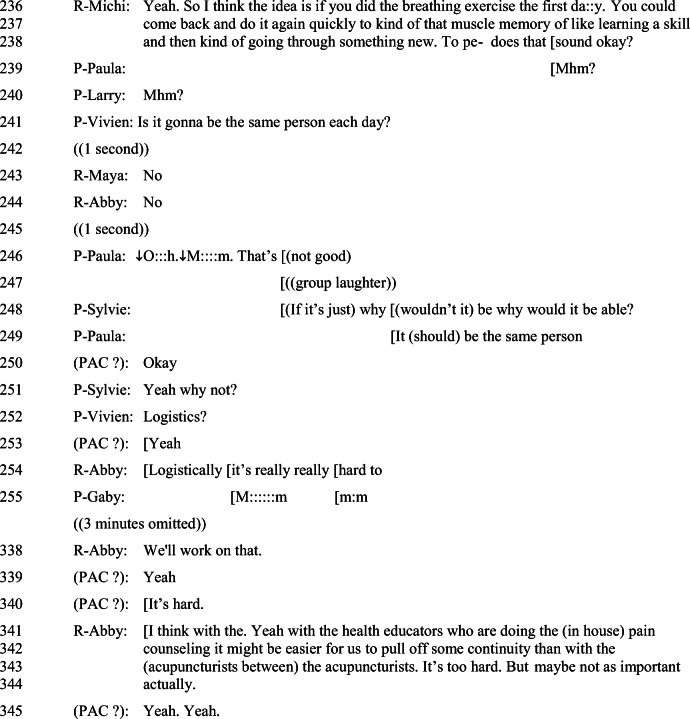

Prior to the first moment of possible advice, one of the researchers, Michi, has just explained details of the pain counseling sessions that would be offered as four 60-min sessions with a counselor over 4 days. A challenge with advice arises after PAC member, Vivien, asks if patients will see the same counselor each session (Fig. 1, line 241). A 1-s pause prefaces researchers, Michi and Abby’s answer, “No,” which reveals that the question may have been unexpected because it addresses arrangement of counselors, not the detailed information Michi presented regarding session content. In PAC member Paula’s response (line 246, “↓O:::h ↓ M:::m”), the transcription symbol “↓” indicates a downward intonation, and several colons indicate elongation of “Oh” and “Mm.” These symbols show Paula not just contemplating but also expressing disappointment in the inconsistent counselor arrangement. Disappointment becomes disapproval with, “that’s not good” and “It should be the same person” (line 249) while the group pursues the decision by questioning why (lines 248, 251).

Figure 1.

All names are pseudonyms. PAC members are identified with “P-” in front of their name; Researchers are identified with “R-” in front of their name. Stacked bracketed words ( “ [ ” ) indicate overlapping talk. Underlines indicate emphasis. An upward arrow ( “↑”)indicates rising intonation. A downward arrow ( “↓” ) indicates falling intonation. Colons (“ :::: ”) indicate elongated speech. ((Words in double parentheses indicate transcriber comment or description.)) (Words in single parentheses indicate transcribers best guess at speech.). A question mark (“?”) indicates a question sounding speech/rising ending. An equals sign (“ = ”) indicates continuation of one speaker over two lines of transcript

During this exchange, group laughter (line 247) tempers and manages advice as a complex endeavor. The laughter highlights the contrast between Michi’s detailed explanation of session content and her (and Abby’s) short response of “No” (lines 243, 244) regarding counselor arrangement, followed by Paula’s response. Additionally, the jocular sounds of PAC laughter contrast with Paula’s disappointment/disapproval. These contrasts, taken as humorous ironies, suggest that PAC members including Paula are unsure whether they are allowed to express such clear disapproval, despite the group’s extended discussion of the suggestion (elaborated in omitted three minutes). Abby’s acknowledgment of the problem as something to work on (see line 338) and rethinking aloud its challenges and possibilities (lines 341–344) contribute to understanding the acceptability of advice. Later, with some effort, the researchers did implement consistency of counselors, which is a reminder that advice-receiving may be a longer-term process.

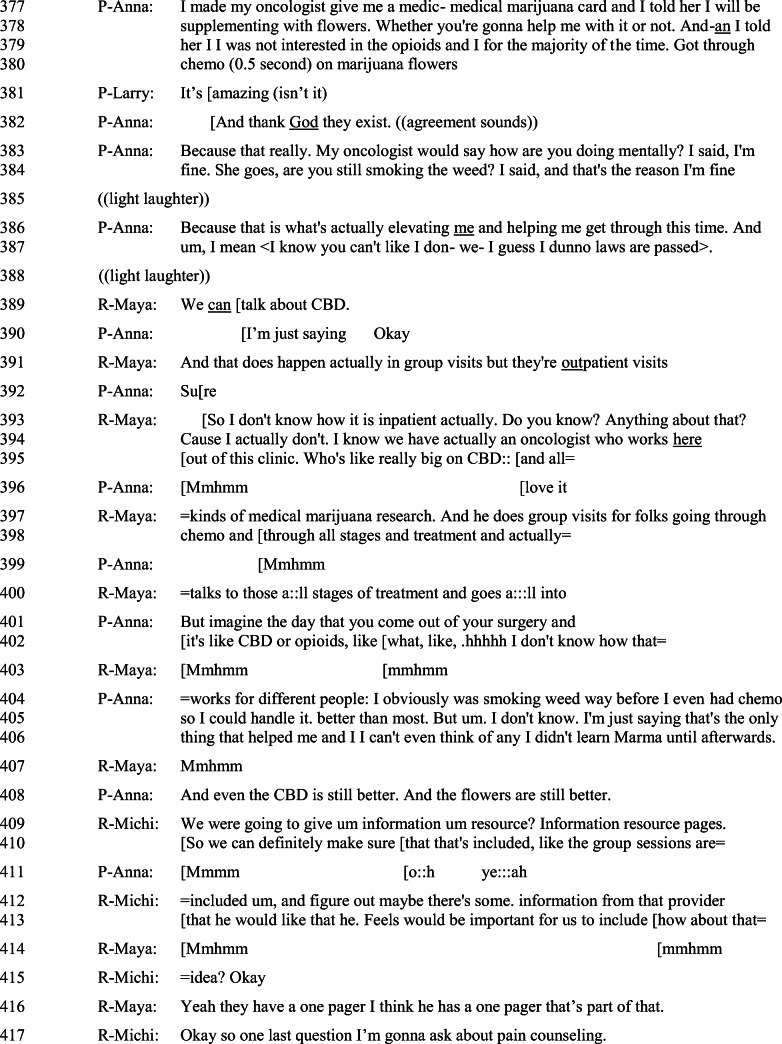

Another challenging advisory moment arises when a suggestion is impossible to implement because it stands outside the parameters of the study. However, the group still processes the suggestion and negotiates its relevance. The challenge begins with PAC member, Anna, asking researchers “when do you introduce the usage of [cannabidiol] CBD,” followed by an explanation of how it helped her through chemotherapy (Fig. 2, lines 377–380). Other members support her testimony with “mhm’s,” “it’s amazing isn’t it,” and their own stories. PRACXIS is designed and funded only to study acupuncture and pain counseling, but Anna’s question of “when” presumes CBD is or should be a part of the study. Researcher, Maya’s response, “we can talk about CBD,” with emphasis on “can,” reframes Anna’s question into a topic of relevance (“whether we can talk about CBD”). This response sidesteps Anna’s presumption without outright denying it. She also engages but distances her team’s research from CBD by confirming its importance though not for this team, and deferring to an oncologist who does CBD research (see lines 394–395). Her less-than technical description of CBD research as something that “happens” (line 391), not knowing “how it is inpatient” (line 393), and setting its interest “out of this clinic” (line 395) further distances the team from the CBD issue.

Figure 2.

All names are pseudonyms. PAC members are identified with “P-” in front of their name; Researchers are identified with “R-” in front of their name. Stacked bracketed words ( “ [ ” ) indicate overlapping talk. Underlines indicate emphasis. An upward arrow ( “↑”)indicates rising intonation. A downward arrow ( “↓” ) indicates falling intonation. Colons (“ :::: ”) indicate elongated speech. ((Words in double parentheses indicate transcriber comment or description.)) (Words in single parentheses indicate transcribers best guess at speech.). A question mark (“?”) indicates a question sounding speech/rising ending. An equals sign (“ = ”) indicates continuation of one speaker over two lines of transcript

Because PRACXIS is interested in “non-pharmacologic options for pain,” it makes sense that Anna would share stories of preferred non-pharmacologic options, and the researchers have emphasized how important PAC feedback is to the study. Therefore, Anna’s continued expression of interest in CBD research through verbal affirmations (lines 396–411) and future orientation, “imagine the day” (line 401), holds out hope for the legitimacy of CBD in health care. Nevertheless, the meeting must carry on without taking Anna’s advice. While Maya’s “Mmhmm’s” (lines 403, 407) allow Anna to continue the thread, researcher, Michi’s suggestion to include CBD in an information page functions as a compromise that neither accepts nor rejects. Anna’s affirmation (“o::h yea:::ah” line 411) allows the researchers to move on to the next question. The team, advisors and researchers together, interactionally manage CBD as rejected but not inappropriate advice.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE APPLICATIONS

Analysis of these two short excerpts begins to show advising—the main work of a PAC—as more complex than simply giving and receiving advice. Advice is negotiated, and its results are co-constructed by both PAC members and researchers together. Previous research acknowledges the value of PACs for providing patient and caregiver voices to a research process that often ignores these stakeholders or presumes to know what is best for them.2 The stated purpose of most PACs is that members offer their assessment and advice, often regarding patient-facing materials.1 Suggestions for best practices exist for PACs such as educating PAC members on clinical research,1 but there is little direction for how to provide advice and virtually no direction for how to take advice when it is difficult or impossible to implement.

AIDA exposes communication practices for the sake of inviting critique and asking questions for discussion to cultivate wise practices for groups themselves. How, for instance, should a PAC member emphasize advice when it is particularly important without appearing pushy? How can a researcher stand firm but not diminish trust or the value of the PAC? Deliberating on answers to questions like these may be useful for developing and maintaining reciprocal relationships and co-learning.7 Open discussions about process give voice to all members as they reflect on how researchers and stakeholders should interact. Creating a universal list of best practices may be helpful, but it may be more useful for practitioners to treat best practices as a situated and dynamic goal, created and evolving as practitioners themselves talk about them. Thus, PACs should set time aside to specifically discuss advice-giving and advice-receiving, noting that sometimes the advice can be managed in the moment and other times may require longer-term consideration.

These examples, while limited in scope, suggest some routine communication practices that can be found in other PACs. Future research that utilizes PACs can benefit from recording PAC interaction. Not only can audio-recordings assist teams remembering previously discussed topics1 but also contribute to a repertoire of successful ways to manage advice and give researchers newly instituting PACs a realistic view of what to anticipate in PAC meetings.

PAC research has been critiqued for not engaging in more systematic and rigorous measures of advisory board outcomes.6 AIDA is an observational method for assessing the value of group interaction. While most teams may not be able to conduct a full AIDA analysis, any re-listening of recordings allows group members to develop awareness of their communication and add to a repertoire of practices that they agree are beneficial. Future PAC research could follow other observational medical studies (e.g., clinician-patient interaction) to formally examine the interaction practices that occur in PAC discussions. Doing so may uncover other communication challenges such as those that come from the identity differences between PAC members and researchers. Too often dismissed merely as the positive fodder that leads to better outcomes, we suggest turning the investigative gaze toward the actual talk itself. Not only does this analysis reveal challenges in the advising process, but it also points out the numerous positive ways participants work them out on their own.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was partially funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (CER-1609-36220). Additional support was provided by the Helen Diller Family Foundation and a UCSF/Genentech Mid-Career Award (MTC). All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the PCORI, its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Anderson A, Benger J, Getz K. Using patient advisory boards to solicit input into clinical trial design and execution. Clin Ther. 2019;41(8):1408–13. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma AE, Willard-Grace R, Willis A, Zieve O, Dubé K, Parker C, et al. "How can we talk about patient-centered care without patients at the table?" Lessons learned from patient advisory councils. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(6):775–84. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.06.150380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Concannon TW, Fuster M, Saunders T, Patel K, Wong JB, Leslie LK, et al. A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(12):1692–701. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2878-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forsythe LP, Ellis LE, Edmundson L, Sabharwal R, Rein A, Konopka K, et al. Patient and stakeholder engagement in the PCORI pilot projects: Description and lessons learned. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):13–21. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3450-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esmail L, Moore E, Rein A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: moving from theory to practice. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(2):133–45. doi: 10.2217/cer.14.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oldfield BJ, Harrison MA, Genao I, Greene AT, Pappas ME, Glover JG, et al. Patient, family, and community advisory councils in health care and research: A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1292–303. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4565-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheridan S, Schrandt S, Forsythe L, Hilliard TS, Paez KA. The PCORI Engagement Rubric: Promising practices for partnering in research. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(2):165–70. doi: 10.1370/afm.2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank L, Forsythe L, Ellis L, Schrandt S, Sheridan S, Gerson J, et al. Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(5):1033–41. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0893-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldsmith DJ, Fitch K. The normative context of advice as social support. Hum Commun Res. 1997;23(4):454–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.1997.tb00406.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tracy K. Action-implicative discourse analysis. J Lang Soc Psychol. 1995;14(1-2):195-215. doi:10.1177/0261927x95141011

- 11.Tracy K. Reconstructing communicative practices. In: Fitch K, Sanders R, editors. Handbook of language and social interaction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2005. p. 301-19.

- 12.Tracy K, Craig RT. Studying interaction in order to cultivate communicative practices. In: Streeck J, editor. New adventures in language and interaction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2010. p. 145-65.

- 13.Craig RT. Communication as practice. In: Shepherd GJ, St. John J, Striphas T, editors. Communication as…: Perspectives on theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. p. 38-47.

- 14.Craig RT. For a practical discipline. J Commun. 2018;68(2):289–97. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqx013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craig RT, Tracy KK. Grounded practical theory: Investigating communication problems. San Diego, CA: Cognella; 2021.

- 16.Agne RR. Self-assessment as a dilemmatic communicative practice: Talk among psychics in training. South Commun J. 2010;75(4):306-27. doi:10.1080/1041794x.2010.504438

- 17.Denvir P. Saving face during routine lifestyle history taking: How patients report and remediate potentially problematic conduct. Commun Med. 2014;11:263-74. doi:10.1558/cam.v11i3.17876

- 18.Robles JS. Troubles with assessments in gifting occasions. Discourse Stud. 2012;14(6):753-77. doi:10.1177/1461445612457490

- 19.Tracy K, Anderson DL. Relational positioning strategies in police calls: A dilemma. Discourse Stud. 1999;1(2):201-25. doi:10.1177/1461445699001002004

- 20.Agne RR, Muller HL. Discourse strategies that co-construct relational identities in STEM peer tutoring. Commun Educ. 2019;68(3):265-86. doi:10.1080/03634523.2019.1606433

- 21.Dimock A. Styles of rejection in local public argument on Iraq. Argumentation. 2010;24(4):423–52. doi: 10.1007/s10503-009-9175-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sprain L, Ivancic S. Communicating openness in deliberation. Commun Monogr. 2017;84(2):241-57. doi:10.1080/03637751.2016.1257141

- 23.Agne RR. Reframing practices in moral conflict: interaction problems in the negotiation standoff at Waco. Discourse Soc. 2007;18(5):549-78. doi:10.1177/0957926507079634

- 24.Tracy K. Challenges of ordinary democracy: A case study in deliberation and dissent. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press; 2010.

- 25.Castor T, Bartesaghi M. Metacommunication during disaster response: “Reporting” and the constitution of problems in hurricane Katrina teleconferences. Manag Commun Q. 2016;30(4):472-502. doi:10.1177/0893318916646454

- 26.Craig RT, Tracy K. “The issue” in argumentation practice and theory. In: Eemeren FHv, Houtlosser P, editors. The practice of argumentation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 2005. p. 11-28.

- 27.Muller HL. A Grounded Practical Theory reconstruction of the communication practice of instructor-facilitated collegiate classroom discussion. J Appl Commun Res. 2014;42(3):325-42. doi:10.1080/00909882.2014.911941

- 28.Mirivel JC. Managing poor surgical candidacy: communication problems for plastic surgeons. Discourse Commun. 2007;1(3):309-36. doi:10.1177/1750481307079203

- 29.Mirivel JC. The physical examination in cosmetic surgery: communication strategies to promote the desirability of surgery. Health Commun. 2008;23(2):153-70. doi:10.1080/10410230801968203 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Mirivel JC, Tracy K. Premeeting talk: An organizationally crucial form of talk. Res Lang Soc Interact. 2005;38(1):1-34. doi:10.1207/s15327973rlsi3801_1

- 31.Fitch K, Sanders RE, editors. Handbook of language and social interaction Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005.