Determinants associated with high preexposure prophylaxis use intention were preexposure prophylaxis knowledge and psychosocial factors among young men who have sex with men, and the amount of individual risk and psychosocial factors among older men who have sex with men.

Background

The uptake of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) against HIV is low among young men who have sex with men (MSM) in the Netherlands. Studying the intention to use PrEP among non-PrEP using young and older MSM can guide health authorities in developing new prevention campaigns to optimize PrEP uptake.

Methods

We investigated the sociodemographic, behavioral, and psychosocial factors associated with a high PrEP use intention in the coming 6 months among 93 young MSM (aged ≤25 years), participating in an online survey, and 290 older MSM (aged ≥26 years), participating in an open, prospective cohort in 2019 to 2020.

Results

Perceiving PrEP as an important prevention tool was associated with a high PrEP use intention among young and older MSM. Among young MSM, a high level of PrEP knowledge and believing that PrEP users take good care of themselves and others were associated with a high PrEP use intention. Among older MSM, 2 or more anal sex partners, chemsex, high HIV risk perception, and believing PrEP increases sexual pleasure were associated with a high PrEP use intention. Believing PrEP leads to adverse effects was associated with a low intention to use PrEP among older MSM.

Conclusions

To conclude, we showed that both behavioral and psychosocial factors were associated with a high PrEP use intention among young and older MSM. In addition to focusing on sexual behavior and HIV risk, future prevention campaigns and counseling on PrEP could incorporate education, endorsing positive beliefs, and disarming negative beliefs to improve the uptake of PrEP in young and older MSM.

In high-income countries, the declining HIV incidence among men who have sex with men (MSM) is likely attributable to the combined effect of condom use, frequent testing, use of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and treatment as prevention.1–4 In 2015, new Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS goals were set for the identification, treatment, and viral suppression of at least 95% of all people living with HIV by 2030.5

In recent years, approximately 15% of the new HIV diagnoses were made among young MSM (aged ≤25 years; YMSM) in the Netherlands.6 However, since the implementation of the national PrEP program started in October 2019, YMSM have accounted for less than 10% of the total uptake of PrEP at the Amsterdam Center for Sexual Health, which is the largest PrEP-providing clinic in the Netherlands.7 The lacking PrEP uptake among YMSM may indicate that a specific approach is needed for this subgroup at risk of HIV.

According to several psychological theories on health behavior, intention often precedes behavior.8,9 By studying the intention of health behavior, that is, the intention to use PrEP, we may provide input for public health interventions and PrEP-related consultations to improve the uptake of PrEP.

The intention to use PrEP has been studied before using various methods. The intention to use PrEP was high—defined as a score ≥4/7 on a scale that measured the intention to use PrEP as soon as it comes available—among 17% of non-PrEP using MSM participating in the Amsterdam Cohort Study on HIV (ACS).10 In 2020, 30% of non-PrEP using MSM visiting the Center for Sexual Health reported a high intention, measured by a positive response to the question if they intended to use PrEP in the coming month.11 In 2015, before the implementation of PrEP in Amsterdam, Bil et al.12 described psychosocial barriers for PrEP use among young and older MSM including fear of adverse effects, a perceived lack of self-efficacy, and anticipated shame of PrEP use. Qualitative studies among YMSM alone in the United States described additional barriers to PrEP use such as the perceived high burden of PrEP care, the cost of PrEP, and a perceived low risk of HIV infection.13,14 In addition, behavioral factors such as chemsex and condomless anal sex have been associated with PrEP use intention.14 Understanding of the interplay between and determining which behavioral and psychosocial factors are associated with PrEP use intention among young and older MSM may give specific input for the development of new targeted strategies to improve the uptake of PrEP among each of these groups. In this study, we assessed which sociodemographic, behavioral, and psychosocial factors are associated with high PrEP use intention among YMSM and older MSM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Population

To study PrEP use intention among YMSM, we conducted an online cross-sectional survey from March 4, 2019, to March 4, 2020. We recruited participants by offering male clients of the Center for Sexual Health a leaflet with QR code that linked to the online questionnaire. In addition, ads linking to the online questionnaire were placed on a gay dating Web site. No incentives were used for recruitment. The Amsterdam Center for Sexual Health provides free-of-charge sexually transmitted infection (STI) and HIV testing and treatment to MSM and other groups at risk of STI.15 Since October 2019, the center also provides PrEP to MSM who are eligible according to the Dutch PrEP guidelines.16 Inclusion criteria for the survey pertained to men who had sex with men in the past 6 months, were aged 16 to 25 years, were conversant in Dutch or English, and had not used PrEP in the past 6 months. On the first page of the survey, inclusion criteria were checked and those who did not meet the criteria were not able to continue the questionnaire. The Medical Ethics Committee of the Amsterdam UMC, location Academic Medical Center, the Netherlands, waived the necessity of a full review of the study protocol (decision number: W20_493 # 20.545).

To contextualize the findings among YMSM, we also assessed factors associated with high PrEP use intention among older MSM. For this reason, we included older HIV-negative MSM participating in the ACS who had a study visit between January and June 2019, were aged ≥26 years, and who had not used PrEP in the past 6 months. The ACS is an open, prospective cohort study initiated in 1984 aiming to investigate the epidemiology, natural history, and pathogenesis of HIV and to evaluate the effect of interventions.17 Participants visit the Public Health Service of Amsterdam every 6 months. At these study visits, participants are tested for HIV and other STI according to the routine of the Amsterdam Center for Sexual Health. In addition, they complete an extensive online questionnaire that includes questions on sexual behavior, PrEP use intention, and related psychosocial determinants. The ACS was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Amsterdam UMC, location Amsterdam Medical Center (decision number: MEC 07/182).

Data Collection

We collected data on sociodemographics, behavior, PrEP use intention, HIV risk perception, PrEP knowledge, and psychosocial determinants of PrEP use intention from the online survey for YMSM. Similar data were collected from the ACS questionnaires completed by older MSM.

Variables

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Age, sex, educational level, and monthly spendable income were assessed. To maintain the privacy of the participants of the survey among YMSM, we decided to collect data in age categories: 16 to 18, 19 to 22, and 23 to 25 years. Among older MSM, age at the included visit was calculated from date of birth and categorized in the following categories: 26 to 34, 35 to 44, 45 to 54, and 55+ years. Sex was categorized as male or other. Educational level was categorized as low (primary school, lower secondary education), medium (intermediate or higher secondary education, higher secondary vocational education), and high (college or university).

Sexual Behavior, PrEP Eligibility, and Chemsex

In the online survey, we assessed any condomless anal sex in the past 6 months dichotomously. In addition, we assessed the self-reported number of anal sex partners and condomless anal sex partners in the past 3 months. The same data were collected from the ACS questionnaire; however, the inquired period was 6 months. Therefore, we halved the reported number of sex partners extracted from the ACS questionnaire and used this value in our analyses. We also assessed the eligibility to use PrEP according to the Dutch PrEP Guideline.16 These guidelines refer to behavior reported by MSM in the past 6 months and include the following criteria: (1) engaged in condomless anal sex with a male sex partner with a detectable HIV viral load or unknown HIV status, (2) been diagnosed with anal chlamydia/gonorrhea or syphilis, or (3) used postexposure prophylaxis. We defined PrEP eligibility as meeting at least one of these criteria, based on self-reports. We defined chemsex as reporting the use around sex of a γ-hydroxybutyric-acid, methamphetamine, or mephedrone in the past 6 months.

PrEP Use Intention

We assessed PrEP use intention by one question: “Are you planning to use PrEP in the coming 6 months?” measured on a Likert-like scale from “very unlikely” to “very likely” on a 5-point scale for YMSM and 7-point scale for older MSM. A high PrEP use intention was defined as score 4 or 5 for YMSM and a score 5 to 7 for older MSM.

HIV Risk Perception and Psychosocial Determinants of PrEP Intention

The questionnaire included 13 items measuring HIV risk perception and psychosocial determinants of PrEP use intention. Two items concerned HIV risk perception, 2 concerned the participant's attitude toward PrEP, 3 concerned their beliefs and expectations about PrEP, and 4 items concerned perceived social beliefs about PrEP users by the participant (Table 1). The items concerning HIV risk perception were measured on a Likert-like scale on a 5-point scale for YMSM and 7-point scale for older MSM (Table 1). We assessed the other psychosocial determinants of PrEP use intention using statements measured on a Likert-like scale ranging from “disagree” to “strongly agree” on 5-point scale for YMSM and 7-point scale for older MSM.

TABLE 1.

An Overview of the Statements and Questions Used to Assess the Different Psychosocial Determinants of PrEP Intention Among YMSM Who Participated in an Online Survey Between March 2019 and March 2020 and Older MSM Who Participated in a Prospective Cohort Study Between January and June 2019 in the Netherlands

| Psychosocial Determinants of PrEP Intention | YMSM | Older MSM |

|---|---|---|

| Intention to use PrEP | ||

| Intention to use PrEP | ||

| Question/statement | Are you planning to use PrEP in the coming 6 mo? | Are you planning to use PrEP in the coming 6 mo? |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | Very unlikely–very likely1–5 | Very unlikely–very likely1–7 |

| Knowledge | ||

| HIV resistance | Not assessed among older MSM | |

| Question/statement | When you take PrEP while unknowingly having HIV, this can make HIV harder to treat (HIV resistance develops) | |

| Response | True/False/I do not know | |

| HIV is an STI | ||

| Question/statement | HIV is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) | |

| Response | True/False/I do not know | |

| HIV can be deadly | ||

| Question/statement | HIV is deadly if left untreated | |

| Response | True/False/I do not know | |

| HIV transmission | ||

| Question/statement | The chance of contracting HIV is larger when fucking than when giving a blowjob | |

| Response | True/False//I do not know | |

| PrEP offers nearly perfect protection against HIV | ||

| Question/statement | PrEP protects really well against HIV | |

| Response | True/False/I do not know | |

| PrEP protects against HIV only | ||

| Question/statement | PrEP not only protects against HIV, it also protects against other STIs (chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis) | |

| Response | True/False/I do not know | |

| PrEP dosing regimen | ||

| Question/statement | PrEP can be taken daily or event-driven (around sex) | |

| Response | True/False/I do not know | |

| Risk perception | ||

| HIV risk perception | ||

| Question/statement | How much risk you think you would have contracting HIV in the coming month? | How much risk you think you would have contracting HIV in the coming 6 mo? |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | A very low risk–a very high risk1–5 | A very low risk–a very high risk1–7 |

| Anticipation of regret of infected with HIV | ||

| Question/statement | How bad would you feel if you would contract HIV in the coming month? | How bad would you feel if you would contract HIV in the coming 6 mo? |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | Not at all bad–very bad1–5 | Not bad at all–very bad1–7 |

| Attitude toward PrEP | ||

| PrEP as prevention tool | ||

| Question/statement | I think PrEP use to prevent HIV is | To use PrEP to protect myself against HIV in the coming 6 mo is I think |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | Very unimportant–very important1–5 | Very unimportant–very important1–7 |

| PrEP use for condomless sex | ||

| Question/statement | I think using PrEP to have sex without a condom is | I think using PrEP to have sex without a condom in the coming 6 mo is |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | Very bad–very good1–5 | Very bad–very good1–7 |

| Beliefs and expectations | ||

| PrEP offers protection against HIV | ||

| Question/statement | If I use PrEP, I am protected against an HIV infection | The use of PrEP is effective enough to prevent HIV for myself |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | Strongly agree–strongly disagree1–5 | Strongly agree–strongly disagree1–7 |

| PrEP use increases sexual pleasure | ||

| Question/statement | If I use PrEP, my pleasure in sex will increase | The use of PrEP increases the quality of my sex life |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | Strongly agree–strongly disagree1–5 | Strongly agree–strongly disagree1–7 |

| PrEP use leads to side-effects | ||

| Question/statement | If I use PrEP, I will probably get unpleasant short-term side effects | The use of PrEP leads to many side-effects |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | Strongly agree–strongly disagree1–5 | Strongly agree–strongly disagree1–7 |

| PrEP is easier to use than condoms | ||

| Question/statement | PrEP is easier to use than condoms in preventing HIV | The use of PrEP is more difficult to use than condoms |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | Strongly agree–strongly disagree1–5 | Strongly agree–strongly disagree1–7 |

| Social norms | In general, other gay men perceive PrEP users as… | |

| PrEP users have a better sex life than nonusers | ||

| Question/statement | I think PrEP users have a more enjoyable sex life | …someone with a more enjoyable sex life |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | Strongly agree–strongly disagree1–5 | Strongly agree–strongly disagree1–7 |

| PrEP users take more sexual risk | ||

| Question/statement | I think PrEP users take more sexual risk | …someone who takes more sexual risk |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | Strongly agree–strongly disagree1–5 | Strongly agree–strongly disagree1–7 |

| PrEP users take care of their own and others' health | ||

| Question/statement | I think PrEP users take care of their own health and that of their sex partner(s) | …someone who takes care of their own health and that of their sex partner(s) |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | Strongly agree–strongly disagree1–5 | Strongly agree–strongly disagree1–7 |

| Self-efficacy | ||

| Acquisition of sufficient PrEP | Do you think you are able to… | |

| Question/statement | Do you think you are able to get a prescription for enough PrEP for your desired use? | …get a prescription for enough PrEP for your desired daily use? …get a prescription for enough PrEP for your desired event-driven use? |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | Not at all able–very able1–5 | Not at all able–very able1–7 |

| Taking PrEP correctly | ||

| Question/statement | Do you think you are able to take PrEP properly for an optimal HIV protection? | …to correctly use daily PrEP? …to correctly use event-driven PrEP? |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | Not at all able–very able1–5 | Not at all able–very able1–7 |

| Willingness to pay for PrEP | Not assessed among older MSM | |

| Willingness to pay €1.00 for PrEP | ||

| Question/statement | Would you be willing to pay €1.00 per PrEP tablet? | |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | Not at all willing–absolutely willing1–5 | |

| Willingness to pay €0.50 for PrEP | ||

| Question/statement | Would you be willing to pay €0.50 per PrEP tablet? | |

| Response (Likert-like scale) | Not at all willing–absolutely wiling1–5 |

PrEP Knowledge

Preexposure prophylaxis knowledge was assessed only among YMSM using 7 statements, which could be answered by “True,” “False,” or “I do not know.” We computed a sum score of the correct answers, assessing a value of 1 if the answer was correct. If the sum score was 6 or 7, we defined it as “high PrEP knowledge,” for scores 0 to 5 as “low/moderate PrEP knowledge.” Participants were not explicitly educated on PrEP before taking part in the questionnaire to prevent influencing their knowledge on PrEP. After completing the questionnaire, participants were stimulated to choose from several online resources to learn more about PrEP.

Willingness to Pay for PrEP

Among YMSM only, we assessed the willingness to pay for PrEP at 2 price levels: €1.00 per tablet (approximately the current price of PrEP at the pharmacy using a doctor's prescription) and €0.50 per tablet by measuring the willingness to pay on a 5-point Likert-like scale ranging from “very unwilling” to “very willing.” If the score was 1 to 3, we defined it as “low willingness to pay for PrEP” (at that price point), and scores 4 to 5 were defined as “high willingness to pay for PrEP.”

Statistical Analyses

Because method and period of recruitment differed widely between YMSM and older MSM, statistical comparisons would not have been able to correct for these biases. Therefore, we have refrained from comparisons in this study. The analyses were performed separately for YMSM and older MSM. In both groups, we described sociodemographics, sexual behavior, and chemsex. We described and calculated median scores and interquartile ranges of PrEP use intention, HIV risk perception, psychosocial determinants of PrEP use intention, and PrEP knowledge. The willingness to pay for PrEP was described among YMSM only. Univariable logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the association between the following determinants and high PrEP use intention: sociodemographics, sexual behavior, chemsex, psychosocial determinants of PrEP use intention, HIV risk perception, and PrEP knowledge. For the logistic regression analysis, we classified age into 4 categories and we reclassified low and middle educational level to one category to ensure adequate numbers per cell. We categorized the number of anal sex partners and number of condomless anal sex partners into quartiles, because the variables did not meet the log-linearity assumption. We dichotomized all responses on Likert-like scales to ensure sufficient numbers per cell to perform logistic regression analyses. For YMSM, we grouped values 1 to 3 as low agreement to the statement and 4 or 5 as high. For older MSM, we grouped 1 to 4 as low and 5 to 7 as high. For HIV risk perception, we grouped values 1 to 2 as low and 3 to 5 as high among YMSM, and values 1 to 3 as low and 4 to 7 as high among older MSM, because of the low numbers per category. If the questions were in reverse for older MSM as compared with YMSM, we categorized the responses by grouping 1 to 3 as high and 5 to 7 as low agreement to the statement. A separate multivariable model for young and older MSM was built in 3 steps to account for the many included variables. First, sociodemographics and behavioral factors associated with a high PrEP use intention (overall P < 0.10) in univariable analysis were included in a multivariable model. Second, psychosocial determinants, HIV risk perception, and PrEP knowledge associated with a high PrEP use intention (overall P < 0.10) in univariable analyses were included. Third, variables associated with a high PrEP use intention to use PrEP (overall P < 0.10) in 1 of the 2 multivariable models were included in a final multivariable model. We included age as confounder in all multivariable models. For all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed in STATA Intercooled 15.1 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

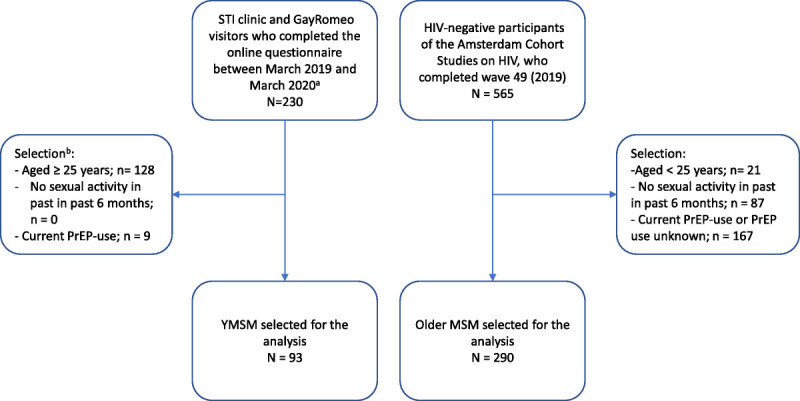

Of the 368 who visited the Web site, 230 YMSM completed the online survey on PrEP use intention, of whom 93 were not on PrEP and eligible for inclusion (Fig. 1). In addition, the data from 290 ACS participants 26 years or older were included. Most YMSM were between 23 and 25 years old (62.4%). The most frequently reported age group among older MSM was 45 to 54 years old (31.3%). Except for one, everyone in the YMSM group self-identified as male. A high educational level was reported by 74.2% of YMSM and 82.2% of older MSM (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of selection procedure of YMSM and older MSM. A, 138 YMSM did not complete the questionnaire after starting it. B, MSM who did not meet the inclusion criteria were not allowed to complete the questionnaire beyond the first page, and consequently, no data were saved. MSM, men who have sex with men; YMSM, young MSM.

TABLE 2.

Sociodemographics, Behavior, and Psychosocial Determinants of PrEP Use Intention of HIV-Negative Young Men Who Have Sex With Men (YMSM; Aged ≤25 Years; n = 93) Participating in an Online Survey Between March 2019 and March 2020, and Older HIV-Negative MSM (Aged ≥26 Years; n = 290) Who Participated in a Prospective Cohort Study Between January and June 2019 in the Netherlands

| YMSM (n = 93) | Older MSM (n = 290) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % |

| Age, y | ||||

| 16–18 | 4 | 4.3 | N/A | |

| 19–22 | 31 | 33.3 | N/A | |

| 23–25 | 58 | 62.4 | N/A | |

| 26–34 | N/A | 77 | 26.6 | |

| 35–44 | N/A | 86 | 29.7 | |

| 45–54 | N/A | 90 | 31.0 | |

| 55+ | N/A | 37 | 12.8 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 93 | 100 | 290 | 100 |

| Other | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Education* | ||||

| Low | 5 | 5.4 | 3/285 | 1.1 |

| Middle | 19 | 20.4 | 48/285 | 16.8 |

| High | 69 | 74.2 | 235/285 | 82.1 |

| Median number of anal sex partners in the past 3 mo† (IQR) | 3 | (2–6) | 1 | (1–3) |

| Condomless anal sex in the past 3 mo | 66 | 71.0 | 219 | 75.3 |

| No | 27 | 29.0 | 71 | 24.5 |

| Yes | 66 | 71.0 | 219 | 75.5 |

| Median number of condomless anal sex partners in the past 3 mo†‡ (IQR) | 2 | (1–3) | 1 | (1-1) |

| Chemsex in the past 6 mo | ||||

| No | 68 | 73.1 | 257 | 88.6 |

| Yes | 25 | 26.9 | 33 | 11.4 |

| GHB use if participant engaged in chemsex in the past 6 mo | ||||

| No | 0/25 | 0 | 2/33 | 6.1 |

| Yes | 25/25 | 100 | 31/33 | 93.9 |

| Mephedrone use if participant engaged in chemsex in the past 6 mo | ||||

| No | 19/25 | 76.0 | 29/33 | 87.9 |

| Yes | 6/25 | 24.0 | 4/33 | 12.1 |

| Methamphetamine use if participants engaged in chemsex in the past 6 mo | ||||

| No | 20/25 | 80.0 | 30/33 | 90.9 |

| Yes | 5/25 | 20.0 | 3/33 | 9.1 |

| PrEP eligibility§ | ||||

| No | 23 | 24.7 | 65 | 22.4 |

| Yes | 70 | 75.3 | 225 | 77.6 |

| Intention to use PrEP (Likert-scale)¶ | ||||

| 1 (very unlikely) | 13 | 14.0 | 77 | 26.6 |

| 2 | 13 | 14.0 | 67 | 23.1 |

| 3 | 21 | 22.6 | 23 | 7.9 |

| 4 | 17 | 18.3 | 36 | 12.4 |

| 5 (max for YMSM) | 29 | 31.2 | 45 | 15.5 |

| 6 | N/A | 22 | 7.6 | |

| 7 (very likely) | N/A | 20 | 6.9 | |

| Intention to use PrEP (binary) | ||||

| Low intention to us PrEP | 47 | 50.5 | 203 | 70.0 |

| High Intention to use PrEP | 46 | 49.5 | 87 | 30.0 |

| Median scores on psychosocial determinants of PrEP use intention (IQR)¶∥ | ||||

| Median willingness to pay €1.00 per tablet for PrEP | 4 | (3–5) | N/A | |

| Median willingness to pay €0.50 per tablet for PrEP | 5 | (4–5) | N/A | |

| Sum of PrEP knowledge (only YMSM), median score | 6 | (5–6) | N/A | |

| HIV risk | 2 | (1–2) | 2 | (2–3) |

| Anticipation of regret if infected with HIV | 5 | (4–5) | 7 | (7–7) |

| Importance of PrEP as HIV prevention tool | 4 | (4–5) | 4 | (3–6) |

| Positive attitude toward PrEP for condomless sex | 3 | (2–3) | 4 | (2–5) |

| Belief PrEP offers protection against HIV | 4 | (4–5) | 5 | (4–6) |

| Belief PrEP increases sexual pleasure** | 3 | (2–4) | 5 | (4–6) |

| Belief PrEP leads to side effects | 3 | (2–3) | 4 | (3–5) |

| Belief PrEP is easier to use than condoms to prevent HIV | 3 | (2–4) | 5 | (4–6) |

| Social belief PrEP users have a better sex life | 3 | (3–4) | 4 | (3–5) |

| Social belief PrEP users take more sexual risk | 4 | (3–4) | 5 | (4–6) |

| Social belief PrEP users take care of their own or other's health | 4 | (3–4) | 5 | (4–6) |

| Self-efficacy to acquire sufficient PrEP for their needs | 4 | (3–5) | 5 | (4–6) |

| Self-efficacy to adhere to PrEP correctly | 5 | (4–5) | 6 | (5–7) |

*Totals may not add up in columns because of missings.

†Self-reported number of anal sex partners in the past 3 months. The number of anal sex partners has been halved for older MSM to correct for the difference in recall period (3 vs. 6 months).

‡Among participants who reported to have engaged in condomless anal sex in the past 3 months.

§Based on self-reported condomless anal sex, PEP, or anal STI or syphilis in the past 6 months.

¶For YMSM, the scale measuring agreement to the psychosocial determinants ranged from 1 to 5; and for older MSM, from 1 to 7.

∥For presentation purposes, we present the median of the scores on the Likert scales of the respective variable.

**Sexual pleasure has been measured using the following statements: “If I use PrEP, my pleasure in sex will increase” among YMSM and “The use of PrEP increases the quality of my sex life” among older MSM.

ACS, Amsterdam Cohort Studies; GHB, γ-hydroxybutyric acid; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; MSM, men who have sex with men; N, number; N/A, not applicable; PEP, postexposure prophylaxis against HIV; %, percentage; PrEP, preexposure prophylaxis against HIV; STI, sexually transmitted infection; YMSM, young MSM.

Young MSM reported a median of 3 (interquartile range [IQR], 2–6) and older MSM a median of 1 (IQR, 1–3) anal sex partners in the past 3 months. The median numbers of condomless anal sex partners were 2 (IQR, 1–3) and 1 (IQR,1–1) among YMSM and older MSM, respectively. Chemsex in the past 6 months was reported by 25 YMSM (26.9%) and 33 (11.3%) older MSM. γ-Hydroxybutyric-acid use was reported by 100.0% and 93.9%, mephedrone by 24.0% and 12.1%, and methamphetamine by 20.0% and 9.1% of YMSM and older MSM who engaged in chemsex. Preexposure prophylaxis eligibility was high among both YMSM (75.3%) and older MSM (77.3%).

PrEP Use Intention and Psychosocial Determinants of PrEP Use Intention

Forty-six (50.5%) YMSM reported a high intention to use PrEP, whereas 87 (30.0%) older MSM did so (Table 2).

Among YMSM, the anticipation of regret if infected with HIV was very strong (median, 5; IQR, 4–5), and PrEP was perceived as an important HIV prevention tool. Perceived HIV risk was low (median, 2; IQR, 1–2). Young MSM were neutral with regard to the attitude to use PrEP for condomless sex, and the beliefs that PrEP increases sexual pleasure, leads to adverse effects, and is easier to use than condoms. Young MSM perceived moderately strong social beliefs about PrEP users that they take more sexual risk and take care of their own and other's health (both: median, 4; IQR, 3–4). They perceived to be self-efficacious to acquire sufficient PrEP for their needs and to adhere to PrEP correctly (median, 5; IQR, 4–5).

Among older MSM, the anticipation of regret if infected with HIV was very strong (median, 7; IQR, 7–7), but they were neutral toward PrEP as an important HIV prevention tool. Perceived HIV risk was low (median, 2; IQR, 2–3). Older MSM were neutral with regard to the attitude to use PrEP for condomless sex, and the beliefs that PrEP increases sexual pleasure (median 5; IQR, 4–6), leads to adverse effects (median 4; IQR, 3–6), and is easier to use than condoms (median, 5; IQR, 4–6). They were neutral in their social beliefs about PrEP users that they take more sexual risk and take care of their own and other's health. They perceived to be self-efficacious to adhere to PrEP correctly (median, 6; IQR, 5–7) but had a neutral perception of their self-efficacy to acquire sufficient PrEP to meet their needs (median, 5: IQR,4–6).

Logistic Regression Analyses

Among YMSM, univariable logistic regression analyses showed that having 5 or more anal sex partners, a high willingness to pay €1.00 and €0.50 per tablet for PrEP, perceiving PrEP as an important HIV prevention tool, the belief that PrEP increases sexual pleasure, the social belief about PrEP users that they take care of their own or other's health, and self-efficacy to acquire sufficient PrEP and to adhere to PrEP correctly were significantly associated with a high PrEP use intention. The social belief about PrEP users that they take more sexual risk was associated with a low PrEP use intention (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Logistic Regression Analyses of the Association of Sociodemographic, Behavioral, and Psychosocial Factors With a High PrEP Use Intention Among YMSM Who Participated in an Online Survey Between March 2019 and March 2020 and Older MSM Who Participated in the Prospective Amsterdam Cohort Study Between January and June 2019

| YMSM (n = 93) | Older MSM (n = 290) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N* | % | OR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | n/N† | % | OR | 95% CI | aOR | (95% CI) | ||||

| Age, y∥ | |||||||||||||||

| 16–22 | 15/35 | 42.9 | 1 | - | - | ||||||||||

| 23–25 | 31/58 | 53.5 | 0.66–3.56 | 1.56 | 0.59–4.15 | - | - | ||||||||

| 26–44 | - | - | 48/163 | 29.5 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 45+ | - | - | 39/127 | 30.7 | 1.06 | 0.64–1.76 | 1.55 | 0.77–3.14 | |||||||

| Sex | |||||||||||||||

| Male | 45/92 | 48.9 | N/A | 87/290 | 30.0 | N/A | |||||||||

| Other | 1/1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Education | |||||||||||||||

| Low/middle | 14/24 | 58.3 | 1 | 15/51 | 29.4 | 1 | |||||||||

| High | 32/69 | 46.4 | 0.62 | (0.24–1.58) | 70/234 | 29.9 | 1.02 | (0.53–1.99) | |||||||

| No. anal sex partners** | |||||||||||||||

| 1 anal sex partner | 7/19 | 36.8 | 1 | 32/166 | 19.3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2 anal sex partners | 9/19 | 47.4 | 1.54 | 0.42–5.64 | 21/48 | 43.8 | 3.26†† | 1.64–6.48 | 3.32 | 1.31–8.42 | |||||

| 3–4 anal sex partners | 7/23 | 30.4 | 0.75 | 0.21–2.72 | 16/41 | 39.0 | 2.68†† | 1.28–5.60 | 4.01 | 1.45–11.07 | |||||

| 5 or more anal sex partners | 23/32 | 71.9 | 4.38†† | 1.31–14.68 | 18/35 | 51.4 | 4.43†† | 2.06–9.54 | 3.70 | 1.39–9.86 | |||||

| Having engaged in condomless anal sex in the past 3 mo | |||||||||||||||

| No | 11/27 | 40.7 | 1 | 20/71 | 28.2 | 1 | |||||||||

| Yes | 35/63 | 53.0 | 1.64 | 0.66–4.07 | 67/219 | 30.6 | 1.12 | 0.62–2.03 | |||||||

| No. condomless anal sex partners**†† | |||||||||||||||

| No condomless anal sex partners | 11/27 | 40.7 | 1 | 25/90 | 27.8 | 1 | |||||||||

| 1 condomless anal sex partner | 12/24 | 50.0 | 1.45 | 0.48–4.41 | 42/160 | 26.3 | 0.93 | 0.52–1.65 | |||||||

| 2 condomless anal sex partners | 6/15 | 40.0 | 0.97 | 0.27–3.51 | 9/22 | 40.9 | 1.80 | 0.68–4.73 | |||||||

| 3 or more condomless anal sex partners | 17/27 | 63.0 | 2.47§ | 0.83–7.39 | 11/18 | 61.1 | 4.09§ | 1.42–11.24 | |||||||

| Chemsex in the past 6 mo | |||||||||||||||

| No | 30/68 | 44.1 | 1 | 67/257 | 26.1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Yes | 16/25 | 64.0 | 2.25§ | 0.87–5.80 | 20/33 | 60.6 | 4.36¶ | 2.06–9.25 | 3.33 | 1.18–9.35 | |||||

| PrEP eligibility‡‡ | |||||||||||||||

| No | 10/23 | 43.5 | 1 | 18/65 | 27.7 | 1 | |||||||||

| Yes | 36/70 | 51.4 | 1.38 | 0.53–3.55 | 69/225 | 30.7 | 1.15 | 0.63–2.13 | |||||||

| PrEP knowledge | |||||||||||||||

| Low/moderate PrEP knowledge | 5/17 | 29.4 | 1 | 1 | N/A | ||||||||||

| High PrEP knowledge | 41/76 | 54.0 | 2.81 | 0.9–8.76§ | 4.10 | 1.53–11.01 | N/A | ||||||||

| Willingness to pay for PrEP | |||||||||||||||

| Low willingness to pay €1.00 per tablet for PrEP | 15/40 | 37.5 | 1 | N/A | |||||||||||

| High willingness to pay €1.00 per tablet for PrEP | 31/53 | 58.5 | 2.35¶ | 1.01–5.45 | N/A | ||||||||||

| Low willingness to pay €0.50 per tablet for PrEP | 3/14 | 21.4 | 1 | N/A | |||||||||||

| High willingness to pay €0.50 per tablet for PrEP | 43/79 | 54.4 | 4.38¶ | 1.13–16.91 | N/A | ||||||||||

| A strong perception of§§ | |||||||||||||||

| HIV risk | 12/20 | 60.0 | 1.72 | 0.63–4.70 | 16/29 | 55.2 | 3.29¶ | 1.51–7.19 | 4.23 | 1.40–12.76 | |||||

| Anticipation of regret if infected with HIV | 38/80 | 47.5 | 0.57 | 0.17–1.88 | 85/278 | 30.6 | 2.20§ | 0.47–10.27 | |||||||

| Importance of PrEP as HIV prevention tool | 43/73 | 58.9 | 8.12¶ | 2.19–30.19 | 7.61 | 1.84–31.41 | 81/144 | 56.3 | 30.0¶ | 12.43–72.39 | 23.19 | 8.80–61.09 | |||

| Positive attitude toward PrEP for condomless sex | 13/21 | 61.9 | 1.92 | 0.71–5.20 | 61/111 | 55.0 | 7.18¶ | 4.10–12.56 | |||||||

| Belief PrEP offers protection against HIV | 40/77 | 52.0 | 1.80 | 0.60–5.45 | 70/201 | 34.8 | 2.26¶ | 1.24–4.14 | |||||||

| Belief PrEP increases sexual pleasure¶¶ | 27/44 | 61.4 | 2.51¶ | 1.09–5.78 | 70/161 | 43.5 | 5.07¶ | 2.79–9.21 | 2.76 | 1.25–6.08 | |||||

| Belief PrEP leads to side-effects | 9/16 | 56.3 | 1.39 | 0.47–4.11 | 16/73 | 21.9 | 0.58§ | 0.31–1.08 | 0.34 | 0.15–0.78 | |||||

| Belief PrEP is easier than condom use to prevent HIV | 19/36 | 52.8 | 1.24 | 0.54–2.86 | 59/167 | 35.3 | 1.85¶ | 1.09–3.14 | |||||||

| Social belief PrEP users have a better sex life | 23/40 | 57.5 | 1.76 | 0.77–4.04 | 40/108 | 37.0 | 1.69§ | 1.01–2.82 | |||||||

| Social belief PrEP users take more sexual risk | 25/64 | 39.1 | 0.24¶ | 0.09–0.64 | 52/183 | 28.4 | 0.82 | 0.49–1.37 | |||||||

| Social belief PrEP users take care of their own or other's health | 30/47 | 63.8 | 3.31¶ | 1.41–7.74 | 3.34 | 1.26–8.85 | 68/203 | 33.5 | 1.80¶ | 1.00–3.24 | |||||

| Self-efficacy to acquire sufficient PrEP for their needs | 36/62 | 58.1 | 2.91¶ | 1.17–7.20 | 38/128 | 29.7 | 0.97 | 0.58–1.63 | |||||||

| Self-efficacy to adhere to PrEP correctly | 43/78 | 55.1 | 4.91¶ | 1.28–18.80 | 46/158 | 29.1 | 0.91 | 0.54–1.52 | |||||||

*Proportion of YMSM with high PrEP use intention of all YMSM with the variable of interest.

†Proportion of older MSM with high PrEP intention of all older MSM with the variable of interest.

‡We assessed the responses to a question on PrEP use intention, to define high PrEP use intention. For YMSM, high PrEP use intention was defined as the response to the question of 4 to 5 on a Likert-like scale; for older MSM, a response of 5 to 7 was defined as high PrEP use intention.

§Overall: 0.05 ≥ P < 0.10 in univariable analysis.

¶Overall P < 0.05 in univariable analysis.

∥The variable was included as a confounder in the multivariable logistic regression analyses.

**Self-reported number of anal sex partners in the past 3 months. The number of anal sex partners has been halved for older MSM to correct for the difference in recall period (3 vs. 6 months).

††Among participants who reported to have engaged in condomless anal sex in the past 3 months.

‡‡Based on self-reported condomless anal sex, PEP, or anal STI or syphilis in the past 6 months.

§§For YMSM, the scale measuring agreement to the psychosocial determinants ranged from 1 to 5; and for older MSM, from 1 to 7. Scores of 3 to 5 were grouped as high agreement to the determinant among YMSM, and scores 4 to 7 as high among older MSM.

¶¶Sexual pleasure has been measured using the following statements: “If I use PrEP, my pleasure in sex will increase” among YMSM and “The use of PrEP increases the quality of my sex life” among older MSM.

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence ratio; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; MSM, men who have sex with men; n, number; N/A, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; %, row percentage; PrEP, preexposure prophylaxis against HIV; YMSM, young MSM.

Among older MSM, 2 or more anal sex partners, 3 or more condomless anal sex partners, chemsex, high HIV risk perception, perceiving that PrEP is an important HIV prevention tool, perceiving the beliefs that PrEP offers protection against HIV and is easier to use than condoms, and the social belief about PrEP users that they take care of their own and other's health were significantly associated with a high PrEP use intention (Table 3).

In the final multivariable logistic regression model, having a high level of PrEP-related knowledge (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 4.10; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.53–11.01), perceiving that PrEP is an important HIV prevention tool (aOR, 5.95; 95% CI, 1.51–23.39), and the social belief about PrEP users that they take good care of their own and other's health (aOR, 3.34; 95% CI, 1.26–8.85) were significantly associated with a high PrEP use intention among YMSM (Table 3).

Among older MSM, the final multivariable model shows that having 2 or more anal sex partners (chemsex [aOR, 3.33; 95% CI, 1.18–9.35]), a high HIV risk perception (aOR, 4.23; 95% CI, 1.40–12.76), perceiving that PrEP is an important HIV prevention tool (aOR, 23.19; 95% CI, 8.80–61.09), and perceiving the belief that PrEP increases sexual pleasure (aOR, 2.76; 95% CI, 1.25–6.08) were significantly associated with a high PrEP use intention. A strongly perceived belief that PrEP leads to adverse effects (aOR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.15–0.78) was associated with a lower intention to use PrEP among older MSM (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study found that a high PrEP use intention was associated with positive social beliefs, a positive attitude toward PrEP, and high PrEP knowledge among YMSM, whereas among older MSM, it was associated with individual behavioral risk factors, anticipation of regret if infected with HIV, and both positive and negative side effects of PrEP.

Previous studies like that of Bil et al.12 showed that low fear of adverse effects and self-efficacy were associated with PrEP use intention both young and older MSM. Similarly, we found that positive social beliefs were associated with a high PrEP use intention among YMSM and fear of adverse effects was associated with lower PrEP use intention among older MSM. In contrast to other studies among YMSM, we did not find that cost of PrEP was a barrier to PrEP use intention.13,14 This might be due to limited statistical power in our sample. The cost of PrEP has decreased extensively in recent years in the Netherlands to approximately €1.00 per tablet, which might have removed the cost barrier, especially among those with a moderately high income.18

Perceiving PrEP users to take good care of their own and other's health was associated with a high PrEP use intention among YMSM, whereas among older MSM, perceived beliefs that PrEP increases sexual pleasure and leads to adverse effects influence the intention to use PrEP. These differences might be generational: fear of HIV in the older generation that lived through a period when HIV was a deadly diagnosis and associated with treatments with many side-effects, as opposed to the more positive association of YMSM who grew up in a time that HIV is a relatively easily treatable, chronic disease.19 Thus, for older MSM, PrEP holds the promise of release of HIV fears, whereas for YMSM, this might not be so much an issue. These differences in fear of HIV have been associated with changes in sexual behavior and HIV risk perception.17,20,21 Another explanation might be that older MSM have comorbidities or belief to be at a higher risk of developing adverse effects that could affect their general health. Health care providers can use these age-specific differences in consultation with patients to increase PrEP use intention.22

Our study has some limitations. First, our modest sample size of 93 YMSM limits the representativeness of our study to the general population of YMSM (in the Netherlands). Young MSM are usually hard to reach for research,23,24 yet methods like snowball sampling or the use of social media influencers for recruitment might have led to more inclusions.23,25,26 Also, because of the sample size, we had limited power for statistical analyses. A post hoc power analysis showed that we had 80% power to detect an OR of 3.65 or larger among YMSM (Power Calculation for logistic regression with binary covariable(s); Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH).27 Second, because method and period of recruitment differed widely between YMSM and older MSM, statistical comparisons would not have been able to correct for these biases. Therefore, we have refrained from comparisons in this study. The information provided by the separate analyses can be informative for health care workers to tailor interventions to the specific age groups. Third, the inclusion period of YMSM overlaps the start of the national PrEP program at the Center for Sexual Health of Amsterdam in October 2019. As PrEP became increasingly accessible since then, the reported intention to use PrEP, belief in self-efficacy to acquire PrEP, and high knowledge of PrEP may have increased among YMSM. Because the date of survey completion was not registered because it was considered to be traceable to individuals and thus conflicting privacy regulations, we were not able to correct for this effect in the analyses.

To conclude, we showed that both behavioral and psychosocial factors were associated with PrEP use intention among young and older MSM. In addition to focusing on sexual behavior and HIV risk, future prevention campaigns and PrEP counseling could incorporate education, endorsing positive beliefs, and disarming negative beliefs to improve the uptake of PrEP in both young and older MSM.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments: The authors thank all participants and the study nurses and data managers of the Amsterdam Cohort Study (ACS). The ACS is a collaboration between the Public Health Service of Amsterdam (GGD Amsterdam) and the Amsterdam University Medical Centers (Academic Medical Centre site), Amsterdam, the Netherlands. The ACS is financially supported by the Centre for Infectious Disease Control Netherlands of the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (Centrum voor Infectieziektenbestrijding-Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu, RIVM-CIb).

Conflict of Interest and Sources of Funding: None declared.

Informed Consent and Ethics Statement: Written informed consent was obtained from all participants of the ACS cohort study. Digital informed consent was obtained from participants of the online survey aimed at young men who have sex with men.

The Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam Medical Ethics Committee has waived the necessity of ethical approval for the online survey among young men who have sex with men (decision number: W20_493 # 20.545.

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam for the ACS cohort study. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki (decision number: MEC 07/182).

Author Contributions: S.H.H., H.M.L.Z., A.A.M., and H.J.C.d.V. contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, and data collection and analysis were performed by S.H.H. and F.d.l.C. The first draft of the manuscript was written by S.H.H. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Sebastiaan H. Hulstein, Email: bas.hulstein@gmail.com.

Hanne M.L. Zimmermann, Email: hzimmermann@ggd.amsterdam.nl.

Feline de la Court, Email: fdlcourt@ggd.amsterdam.nl.

Amy A. Matser, Email: amatser@ggd.amsterdam.nl.

Maarten F. Schim van der Loeff, Email: mschim@ggd.amsterdam.nl.

Elske Hoornenborg, Email: ehoornenborg@ggd.amsterdam.nl.

Udi Davidovich, Email: udavidovich@ggd.amsterdam.nl.

Maria Prins, Email: mprins@ggd.amsterdam.nl.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grulich AE Guy R Amin J, et al. Population-level effectiveness of rapid, targeted, high-coverage roll-out of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in men who have sex with men: The EPIC-NSW prospective cohort study. Lancet HIV 2018; 5:e629–e637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ECDC . HIV/AIDS Surveillance in Europe 2020. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/hivaids-surveillance-europe-2020-2019-data. Accessed February 8, 2021.

- 3.Rodger AJ Cambiano V Bruun T, et al. Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in serodifferent gay couples with the HIV-positive PARTNER taking suppressive antiretroviral therapy (PARTNER): Final results of a multicentre, prospective, observational study. Lancet 2019; 393:2428–2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith DK Herbst JH Zhang X, et al. Condom effectiveness for HIV prevention by consistency of use among men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 68:337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNAIDS . Fast-track: Ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030. Available at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/JC2686_WAD2014report. Accessed February 8, 2021.

- 6.van Sighem AW F Boyd A Smit C, et al. HIV Monitoring Report 2019. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Stichting HIV Monitoring (SHM), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soapoli GGD. Amsterdam. Jaarcijfers 2020. Available at: https://www.ggd.amsterdam.nl/publish/pages/473215/jv_soapoli_2020_v2.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2021.

- 8.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 1991; 50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rimer BK. The health belief model and theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coyer L van Bilsen W Bil J, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in the Amsterdam cohort studies: Use, eligibility, and intention to use. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0205663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hulstein SH Matser A van der Loeff MFS, et al. Eligibility for HIV preexposure prophylaxis, intention to use preexposure prophylaxis, and informal use of preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Sex Transm Dis 2021; 48:86–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bil JP Davidovich U van der Veldt WM, et al. What do Dutch MSM think of preexposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV-infection? A cross-sectional study. AIDS 2015; 29:955–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hess KM Crawford J Eanes A, et al. Reasons why young men who have sex with men report not using HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: Perceptions of burden, need, and safety. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2019; 33:449–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yi S Tuot S Mwai GW, et al. Awareness and willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc 2017; 20:21580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heijman TL Van der Bij AK De Vries HJ, et al. Effectiveness of a risk-based visitor-prioritizing system at a sexually transmitted infection outpatient clinic. Sex Transm Dis 2007; 34:508–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nederlandse Vereniging van HIV behandelaren . HIV Pre-expositie profylaxe (PrEP) richtlijn Nederland. Available at: http://nvhb.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/PrEP-richtlijn-Nederland-versie-2-dd-15-april-2019.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2021.

- 17.van Bilsen WPH Boyd A van der Loeff MFS, et al. Diverging trends in incidence of HIV versus other sexually transmitted infections in HIV-negative MSM in Amsterdam. AIDS 2020; 34:301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Dijk M de Wit JBF Guadamuz TE, et al. Slow uptake of PrEP: Behavioral predictors and the influence of price on PrEP uptake among MSM with a high interest in PrEP. AIDS Behav 2021; 25:2382–2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Bilsen WPH Zimmermann HML Boyd A, et al. , HIV Transmission Elimination Amsterdam Initiative . Burden of living with HIV among men who have sex with men: A mixed-methods study. Lancet HIV 2020; 7:e835–e843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basten M den Daas C Heijne JCM, et al. The rhythm of risk: Sexual behaviour, PrEP use and HIV risk perception between 1999 and 2018 among men who have sex with men in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. AIDS Behav 2021; 25:1800–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacKellar DA Hou SI Whalen CC, et al. HIV/AIDS complacency and HIV infection among young men who have sex with men, and the race-specific influence of underlying HAART beliefs. Sex Transm Dis 2011; 38:755–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsons JT Rendina HJ Lassiter JM, et al. Uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a national cohort of gay and bisexual men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; 74:285–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muhib FB Lin LS Stueve A, et al. A venue-based method for sampling hard-to-reach populations. Public Health Rep 2001; 116(Suppl 1):216–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gama A, Martins MO, Dias S. HIV research with men who have sex with men (MSM): Advantages and challenges of different methods for most appropriately targeting a key population. AIMS Public Health 2017; 4:221–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao A Stahlman S Hargreaves J, et al. Sampling key populations for HIV surveillance: Results from eight cross-sectional studies using respondent-driven sampling and venue-based snowball sampling. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2017; 3:e72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu D Tang W Lu H, et al. Leading by example: Web-based sexual health influencers among men who have sex with men have higher HIV and syphilis testing rates in China. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21:e10171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demidenko E. Power/Sample Size Calculation for Logistic Regression with Binary Covariate(s). Available at: https://www.dartmouth.edu/~eugened/power-samplesize.php. Accessed April 21, 2021.