Background:

Prolonged opioid use after surgery has been a contributing factor to the ongoing opioid epidemic. The purpose of this systematic review is to analyze the definitions of prolonged opioid use in prior literature and propose appropriate criteria to define postoperative prolonged opioid use in hand surgery.

Methods:

Using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines 130 studies were included for review. The primary outcome was the timepoint used to define prolonged opioid use following surgery. The proportion of patients with prolonged use and risk factors for prolonged use were also collected for each study. Included studies were categorized based on their surgical specialty.

Results:

The most common timepoint used to define prolonged opioid use was 3 months (n = 86, 67.2% of eligible definitions), ranging from 1 to 24 months. Although 11 of 12 specialties had a mean timepoint between 2.5 and 4.17 months, Spine surgery was the only outlier with a mean of 6.90 months. No correlation was found between the definition’s timepoint and the rates of prolonged opioid use.

Conclusions:

Although a vast majority of the literature reports similar timepoints to define prolonged postoperative opioid use, these studies often do not account for the type of procedures being performed. We propose that the definitions of postoperative prolonged opioid use should be tailored to the level and duration of pain for specific procedures. We present criteria to define prolonged opioid use in hand surgery.

Takeaways

Question: Which definitions are used to define prolonged postoperative opioid use in surgical research?

Findings: While many surgical specialties maintain similar definitions of prolonged opioid use in research studies, these do not seem to take into account the intensity and duration of pain after various surgical procedures. Therefore, these definitions may not correspond to what is considered prolonged use in clinical care. We propose definitions to be used during the postoperative use of opioids following hand surgery.

Meaning: Consensus on what constitutes prolonged postoperative opioid use may help physicians and researchers to determine its prevalence among patients that undergo hand surgery.

INTRODUCTION

The increase in the consumption of opioids has contributed to a subsequent increase in opioid use disorder and the complications thereof, both with prescribed medical use as well as illicit use.1–3 Therefore, adequately managing postoperative pain with the judicious use of opioids has become an area of active research.4,5 Numerous studies have assessed the prevalence and risk factors of opioid use for extended periods of time (often termed “prolonged opioid use”).6

Opioid prescriptions around surgical intervention present an opportunity for opioid dependency to develop or worsen. For example, patients who already filled opioid prescriptions before surgical intervention are at increased risk for additional prescription requests after surgery.7 Similarly, Katzman et al8 reported that patients with intermittent opioid use before surgery were more likely to have persistent opioid use postoperatively. These findings are concerning considering the clear association between longer-term opioid use and the development of tolerance and addiction.9

Currently, there is no clear consensus in the literature as to what constitutes prolonged opioid use in surgical patients, and current attempts at defining prolonged opioid use are flawed. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines long-term opioid therapy as “use of opioids on most days for >3 months.”10 This definition does not account for patient populations naive to opioid therapy, or those undergoing minor procedures with minimal postoperative pain.

Although hand surgeons often perform minor surgical procedures, prolonged opioid use and over-prescription of opioids continue to be a problem.11 For example, one recent study found that over 75% of patients undergoing carpal or cubital tunnel release fill a perioperative opioid prescription, and 13% of these patients continued to fill prescriptions 90–180 days after surgery.12 Despite the overuse and over-prescription of opioids in hand surgery, only one study has evaluated the rates and risk factors of prolonged use in postoperative hand surgical patients, and no study has attempted to define and standardize appropriate timeframes for prolonged postoperative opioid use by procedure.

To ensure that definitions of prolonged opioid use are practically useful in a hand surgical practice, this study has three aims: (1) to analyze and compare the definitions of prolonged opioid use among surgical specialties; (2) to investigate the relationship between the definition and prevalence of prolonged opioid use; and (3) to address shortcomings of current definitions by providing new criteria for prolonged opioid use following hand surgical procedures.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.13 A literature search was performed for all published clinical studies on opioid use after surgery within the Embase, Web of Science, and PubMed databases on June 10, 2020. Our search strategy included all English articles published in the years 1990 through 2020 (see table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which details search strategy in PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/B984). Since this systematic review does not involve interactions with human subjects, it is exempt from IRB review.

Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria required studies to have at least one explicit definition of prolonged opioid use, to include patients undergoing surgery, and to include patients receiving opioids postoperatively. We included all studies using terms related to prolonged opioid use including “chronic,” “long-term,” “sustained,” “persistent,” and others. We excluded all animal studies, studies that only evaluated preoperative opioids, and studies with secondary surgery within the opioid use evaluation time if the second procedure was unaccounted for.

Study Selection and Data Collection

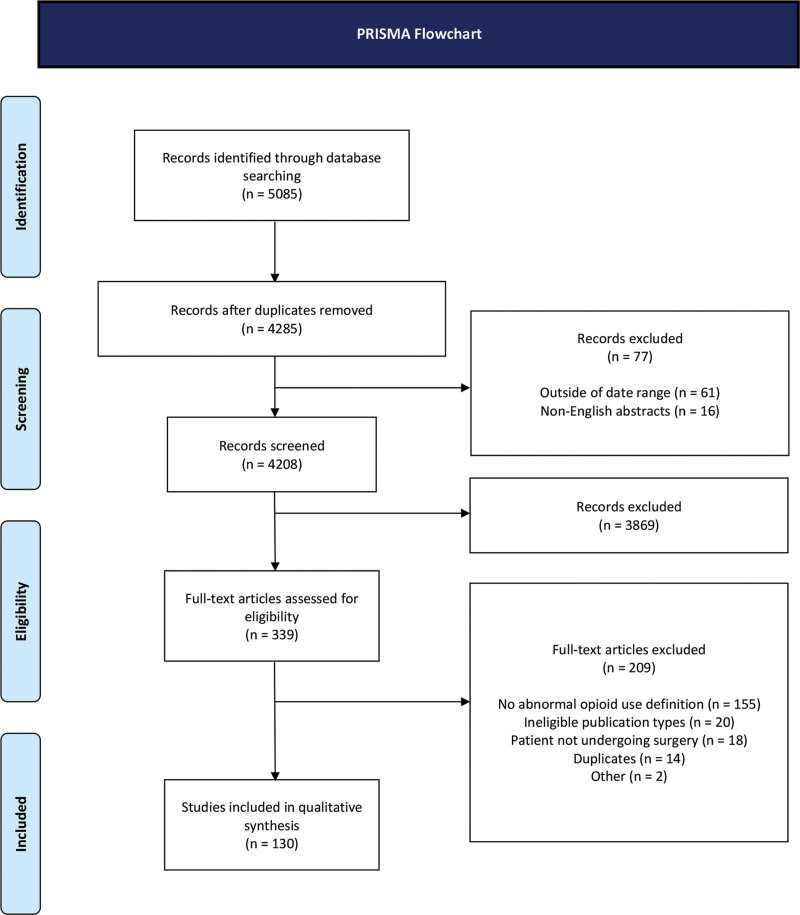

The review process was conducted independently by two authors (S.N. and S.M.), whereas a third author (Y.H.) mediated discrepancies. The initial search returned 5085 clinical studies on postoperative opioid use. Eight hundred duplicates, 16 non-English articles, and 61 articles outside the date range were removed. All remaining 4208 titles and abstracts were manually screened to determine eligibility. After the initial screening, 339 articles met the preliminary eligibility criteria. Of these, 209 articles were excluded during full-text analysis, leaving a total of 130 eligible for data collection. The data was manually analyzed and extracted in a standardized fashion (Fig. 1). The references of the included studies were cross-checked for additional studies but none met the inclusion criteria. No formal assessment of the potential bias among the included studies was performed.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the definition of prolonged opioid use. These definitions were categorized based on the timeframe used in each study to distinguish between “regular” and “prolonged” (or any equivalent term) durations of opioid use; no other factors were used in categorization to avoid overspecification. Other collected variables included the prevalence of prolonged opioid use (as a percentage of the population at-risk) and mean or median patient age (depending on what was used by the study). Although multiple tools for synthesis of means and medians into an overall mean have been published, all of these have their limitations and, therefore, we decided not to use them.14,15 We treated age as a descriptive rather than an explanatory variable and categorized the means and medians into decades ranging from “less than 20 years” to “80 years or more.” We collected risk factors for prolonged opioid use and determined whether or not oral morphine equivalents (OMEs) were reported.

The publications were also grouped by “surgical specialty,” placing studies into categories based on the specialty that predominantly performs the procedures studied and the scope of the journal in which the publication was published. For example, a study of patients that underwent total knee arthroplasty would be categorized as “orthopedic.” Included surgical specialties were orthopedic, spine, general, surgical oncology, urologic, gynecologic, cardiac, plastic, otolaryngology, pediatric, and mixed for studies with procedures spanning multiple specialties. Spine surgery was considered separately from other orthopedic surgical subspecialties due to the fundamental clinical differences in surgical procedures and subsequent rehabilitation.

Patient cohorts were also categorized by their preoperative opioid use, the definition of which may differ between individual studies. Cohorts could be categorized as naive (if patients used no opioids in the preoperative period), nonnaive (if patients used opioids preoperatively), combined (when both naive and nonnaive patients were included in a single study), or unknown (if a study did not specify preoperative opioid use).

The prevalence of prolonged opioid use was separately presented as means and SDs for different definitions and different surgical specialties. Furthermore, the mean number of months used to define prolonged opioid use was presented for each surgical specialty; all definitions that were not time-based were excluded from this analysis. Last, we performed a Spearman’s correlation analysis to evaluate the relationship between definition timeframes and prevalence of prolonged opioid use.

RESULTS

General Characteristics

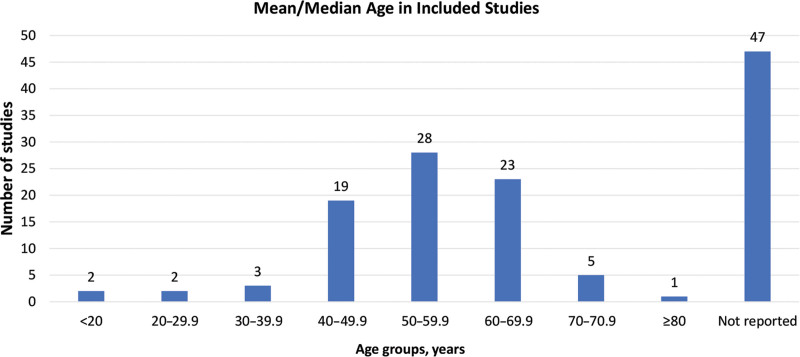

A total of 130 studies were included for data extraction (see table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which details overview of collected data, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/B985; see table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, which lists the studies that were included as part of the systematic review, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/B986). Among the 83 studies that reported a mean or median age, a cohort age between 50 and 59.9 years was the most common and found in 28 studies (33.7%). The range of age groups included patients from less than 20 (n = 2) to “80 or more” (n = 1) years old. Of the 130 included studies, 47 did not report a mean or median age (Fig. 2). Among the included studies, 56.9% reported OMEs and 43.1% did not.

Fig. 2.

Mean/median age in included studies.

Preoperative opioid use varied, but combined cohorts with both naive and nonnaive patients represented 60.0% of the included studies. An opioid-naive cohort was present in 37.7% of the included studies, 1.5% of studies did not clearly state the preoperative opioid status of their patients and only 0.8% of studies specifically assessed cohorts that were nonnaive to opioid use.

Definitions

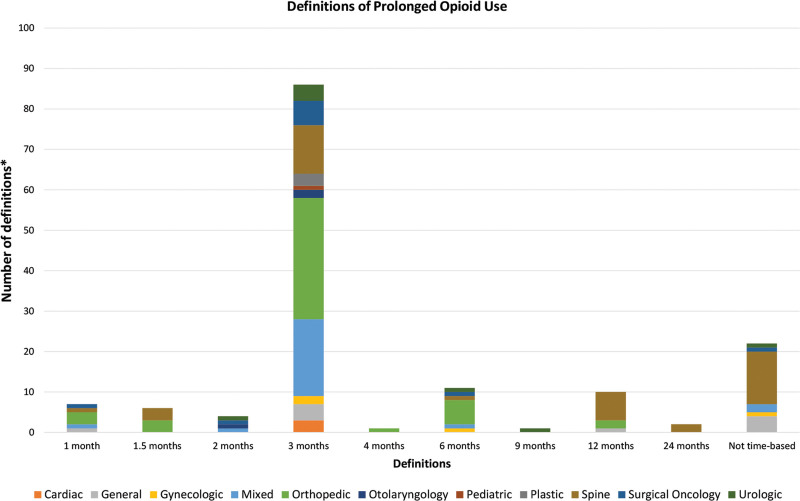

The definitions of prolonged opioid use were categorized into different timeframes, ranging from 1 to 24 months postoperatively, based on the first day the authors of a given publication considered opioid use to be prolonged. The 130 studies provided a total of 150 definitions due to 14 studies that used two or more definitions. Of these 150 definitions, 22 did not define prolonged opioid use by means of a postoperative timepoint and were therefore excluded from quantitative analysis, leaving a total of 128 eligible definitions.

The most common timepoint after which opioid use was considered prolonged was 3 months, which accounted for 67.2% of eligible definitions. Following prolonged use after 3 months, the most frequent postoperative time points were 6 months in 8.59%, 12 months in 7.81%, and 1 month in 5.47% of eligible definitions (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Definitions of prolonged opioid use. *N = 150, of which 22 were ineligible for time-based analysis.

Prolonged opioid use, referring to the postoperative circumstance in which a patient used opioids for a duration in excess of what was clinically expected or appropriate, was described using several different terms. These terms included prolonged, chronic, persistent, long-term, sustained, extra-prolonged, and dependent.

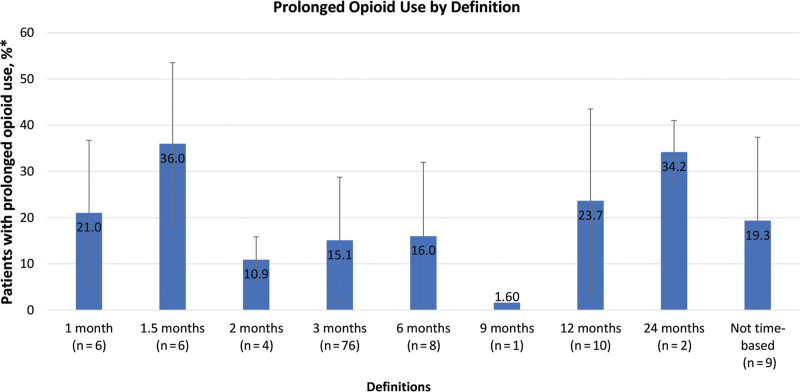

Postoperative Timeframe and Prevalence of Prolonged Opioid Use

For each of the timeframes mentioned in Figure 3, the mean prevalence of prolonged opioid use was calculated. The highest mean prevalence of prolonged opioid use was found in studies that used a cutoff of 1.5 months with 36.0% (SD 17.5) of patients, 24 months (34.2%, SD 6.83), and 12 months (23.7%, SD 19.9), respectively. The lowest mean prevalence, at 1.60%, was reported by the single study that utilized a cutoff of 9 months (Fig. 4). No significant association was found between the definition timeframes and the prevalence of prolonged opioid use (Spearman’s correlation, P = 0.56).

Fig. 4.

Prolonged opioid use by definition. *N = 122, due to eight studies not reporting a percentage of prolonged opioid use.

Relationship between Surgical Specialty and Prolonged Opioid Use

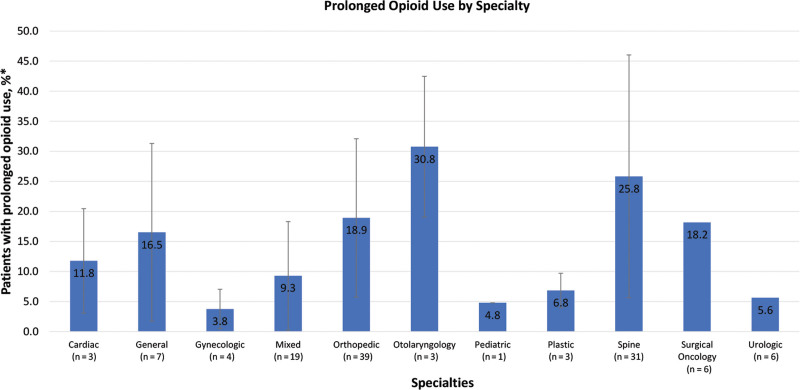

The included studies were categorized according to the procedures being performed and the scope of the journal in which the study was published. The most represented specialties in our analysis were orthopedic (n = 43), spine (n = 32), and mixed (n = 21), whereas the least represented specialty was pediatric surgery (n = 1) as shown in the footnote of Figure 5.

Fig. 5.

Prolonged opioid use by specialty. *N = 122, due to eight studies not reporting a percentage of prolonged opioid use. Total numbers of studies per speciality are cardiac (3), general (8), gynecologic (4), mixed (21), orthopedic (43), otolaryngology (3), pediatric (1), plastic (3), spine (32), surgical oncology (6), and urologic (6).

The mean prevalence of prolonged opioid use was calculated for each surgical specialty. The specialties with the highest prevalence of prolonged opioid use were otolaryngology (30.8%, SD 11.7) and spine (25.8%, SD 20.2), whereas gynecologic (3.80%, SD 3.30) and pediatric (4.80%, n = 1) were the lowest (Fig. 5). There were eight studies that defined prolonged opioid use but unfortunately did not report the percentage of patients who met those criteria.

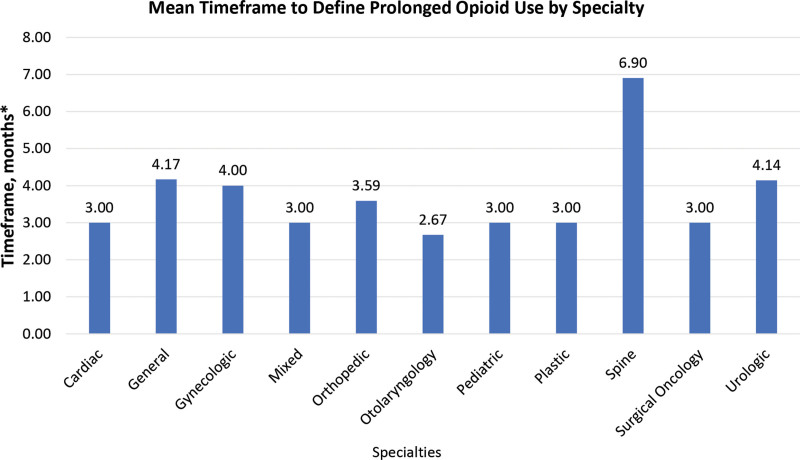

The mean time after which opioid use was considered prolonged was calculated for each specialty. As shown in Figure 6, the mean of 6.90 months in spine surgery is an outlier compared to the mean timeframes of the other specialties.

Fig. 6.

Mean timeframe to define prolonged opioid use by specialty. *N=128, due to 22 definitions not being time-based.

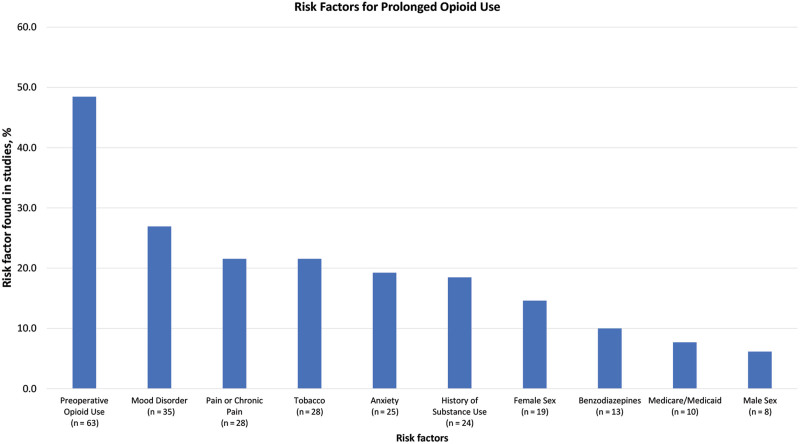

Risk Factors for Prolonged Opioid Use

A wide variety of risk factors were reported to be significantly associated with prolonged opioid use. Preoperative opioid use was the most common risk factor (48.5% of studies), followed by mood disorders in 26.9% of studies. Other notable risk factors included pain or chronic pain (21.5%), tobacco use (21.5%), anxiety disorders (19.2%), and history of substance use (18.5%), as shown in Figure 7. Furthermore, for patients from the United States, being treated outside of the Northeastern United States was reported as a risk factor in six (4.62%) studies.

Fig. 7.

Risk factors for prolonged opioid use.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review highlights similarities in defining prolonged opioid use within existing literature, which was relatively consistent across various surgical specialties but without overall consensus. A timeframe of 3 months after surgery was found in 67.2% (n = 86) of the 128 time-based definitions, with 11 of the 12 categories using a timeframe between 2.50 and 4.17 months. Only spine surgery used a considerably different timeframe, at a mean of 6.90 months. Despite the seeming similarity of prolonged opioid use for varying specialties, there are no procedure-specific definitions for prolonged opioid use, particularly in the field of hand surgery. These would be useful for the practicing surgeon, as postoperative requirements generally vary for different operations and prolonged opioid use rates for elective hand surgical procedures are high.12

Orthopedic (n = 43) and spine (n = 32) surgeries were the most represented categories in the literature while other categories, such as gynecologic (n = 4) surgery, were less represented. There was only one publication in hand surgery that reported rates of prolonged opioid use.12 Similarly, on average 25.8% of spine surgery patients and 18.9% of orthopedic surgery patients were identified as prolonged opioid users, compared to only 3.80% of patients in gynecologic surgery. One possible explanation for the variability in specialty representation is that the perceived extent of prolonged opioid use within each field guides the number of publications. Most notable is that the average timeframe used to define prolonged opioid use in spine surgery is rather long (6.90 months). If Spine surgery used a timeframe to define prolonged use that was in agreement with other fields (eg, 3 months), the proportion of patients with prolonged opioid use would likely increase. This emphasizes the need to reach a consensus within each surgical field on the definitions of prolonged opioid use, so that the results from research efforts correspond well with clinical experiences.

Although not all studies assessed risk factors for the development of prolonged opioid use, a selection of risk factors were commonly found. These included preoperative opioid use, a history of mood disorders, chronic pain, anxiety disorders, tobacco use, and a history of substance use disorder. Specific to the United States, six studies reported being treated outside of the Northeastern United States as a risk factor for prolonged opioid use. A possible explanation for the regional differences could be increasing efforts in the Northeastern United States to reduce opioid use after an initial surge, such as the implementation of statutory prescription limits.16,17

Consensus on definitions of prolonged opioid use will provide a benchmark for future research and a timeframe for clinicians to mitigate prolonged opioid use. Complete uniformity in the definition of prolonged opioid use may not contribute to achieving these aims. For example, both the studies by Steen et al18 and Zaveri et al19 used the timepoint of 3 months after surgery to define prolonged opioid use after major limb amputation and minor outpatient surgery, respectively. Clinically, using 3 months to define prolonged opioid use for both major limb amputations and less invasive procedures such as a carpal tunnel release fails to account for the expected differences in both the intensity and duration of pain.

In the absence of a procedure and specialty-specific consensus for postoperative prolonged opioid use within hand surgery, we propose criteria for four different categories of procedures within hand surgery along with example procedures for each of these categories (Table 1). These criteria represent a synthesisBof our clinical expertise and aim to provide a boundary after which opioid use can be considered prolonged following various hand surgical procedures, which can be applied in research settings. The aim of the study was not to dictate an optimal prescription regimen for individual patients, which is at their treating physicians’ discretion. However, although clinician judgement will remain fundamental to the tailoring of opioid prescriptions based on patients’ risk factors, behavior, and complications, the purpose of these criteria is to lay the foundation upon which future clinical research can define procedure-specific prolonged opioid use for clinical application. Future research efforts should be undertaken to reach a procedure-specific consensus on how to define prolonged opioid use and these studies should involve the public, perhaps by means of a Delphi process.

Table 1.

Proposed Criteria for Defining Prolonged Opioid Use in Hand Surgery Based on Clinical Expertise of Authors

| Type of Surgery | Example Procedures | Proposed Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Minor soft-tissue procedures | · Carpal tunnel release | Opioid use beyond 2 wks (14 d) should be considered abnormal |

| · Trigger finger release | ||

| · Dupuytren fasciectomy | ||

| · First compartment release for de Quervain tenosynovitis | ||

| · Flexor tendon repair or tenolysis | ||

| · Extensor tendon repair or tenolysis | ||

| · Minor excisions (eg, mucoid cyst) | ||

| Major soft-tissue procedures | · Extensive debridement and soft-tissue coverage with local tissue rearrangement or advancement | Opioid use beyond 1 mo (30 d) should be considered abnormal |

| · Flap coverage for soft-tissue defect | ||

| · Skin grafting for significant burn injuries or soft-tissue defect | ||

| Minor bone procedures | · ORIF or closed reduction and pinning of fractures from the metacarpal level and distal | Opioid use beyond 1 mo (30 d) should be considered abnormal |

| · Amputation of digit | ||

| · CMC arthroplasty | ||

| · PIP joint arthroplasty | ||

| Major bone procedures | · ORIF of radius, ulna, or humerus | Opioid use beyond 6 wks (42 d) should be considered abnormal |

| · Total shoulder arthroplasty | ||

| · Major limb amputation | ||

| · Corrective osteotomy |

CMC, carpometacarpal; ORIF, open reduction internal fixation; PIP, proximal interphalangeal.

In addition to the proposed criteria, the reported risk factors should be considered to counsel at-risk patients. Additionally, opioids should be given in conjunction with acetaminophen or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs since this has been demonstrated to reduce postoperative opioid dependence.20 Furthermore, the authors suggest that the evaluation of OMEs may be helpful in critically reviewing the amount of opioids prescribed to individual patients, and should be standard practice in research on this topic. Last, dose tapering strategies have been demonstrated to be effective in weaning patients off their opioid therapies.10

The results of this review should be interpreted in the light of its limitations. While the populations studied were cohorts of patients with postoperative opioid use, we were unable to analyze surgical outcomes and their effect on prolonged opioid use as this information was not included in the studies we analyzed. During full-text review the authors found that a vast majority of the included studies evaluated representative populations for their respective surgical procedures, to avoid introducing bias by specifically selecting patients with better or worse surgical outcomes. A second limitation is the limited number of studies for some of the surgical specialties. Still, this also suggests that some surgical fields may benefit from further research on prolonged opioid use to evaluate the extent of this problem in that field. Last, even though gray literature was not analyzed, our data provide a focused report on what the primary literature considers prolonged opioid use.

Several findings of this review may inspire future research efforts. The first of these findings is that only four papers studied a patient population with a mean or median age below 30 years, indicating that younger patients may be underrepresented in research on this topic.21–24 Therefore, it is not well understood whether the extent of this problem is different in patients of this age, and whether risk factors for prolonged use may be different. Since only one paper (0.8%) focused solely on a nonnaive cohort, the authors hypothesize that research efforts specifically in nonnaive patients may aid in identifying additional risk factors in this already at-risk population.6 Furthermore, the authors suggest that future research efforts may benefit from standardization of terminology and methods to report the amount of opioid use. Last, although the proposed categorizations of procedures within hand surgery are based on both literature review and clinical experience, a prospective evaluation is warranted to determine their validity. The authors encourage academic discussion of the criteria to identify potential shortcomings and to expand the list of procedures.

CONCLUSIONS

Although there are similarities in the definitions of postoperative prolonged opioid use, there is poor consensus about procedure-specific definitions of prolonged opioid use after surgery. The authors therefore emphasize the need for consensus building about the definition of prolonged opioid use following hand surgery, so that future research efforts may accurately estimate the extent of this problem and that clinicians may specifically counsel at-risk patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Presented at Plastic Surgery the Meeting 2021; the American Society for Surgery of the Hand 2021; the New England Hand Society Annual Meeting 2021; and the American Association for Hand Surgery 2022.

Disclosure: Dr. Eberlin is a consultant for AxoGen, Integra, and Checkpoint. Dr. Lans is a consultant for AxoGen. Dr. Chen is a consultant for Biedermann Motech. The other authors have no financial interest to declare.

‘This study was in part supported by the Jesse B. Jupiter/Wyss Medical Foundation Endowment.

Related Digital Media are available in the full-text version of the article on www.PRSGlobalOpen.com.

This study was exempt from the requirement of ethical approval due to being based on de-identified, publicly available data.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Government Accounting Office. OxyContin abuse and diversion and efforts to address the problem: highlights of a government report. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother; 2004;18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ladha KS, Neuman MD, Broms G, et al. Opioid prescribing after surgery in the United States, Canada, and Sweden. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1910734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dayer LE, Painter JT, McCain K, et al. A recent history of opioid use in the US: Three decades of change. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54:331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thiels CA, Ubl DS, Yost KJ, et al. Results of a prospective, multicenter initiative aimed at developing opioid-prescribing guidelines after surgery. Ann Surg. 2018;268:457–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Overton HN, Hanna MN, Bruhn WE, et al. ; Opioids After Surgery Workgroup. Opioid-prescribing guidelines for common surgical procedures: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;227:411–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pagé MG, Kudrina I, Zomahoun HTV, et al. A systematic review of the relative frequency and risk factors for prolonged opioid prescription following surgery and trauma among adults. Ann Surg. 2020;271:845–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross BJ, Wu VJ, Mansour AA, III, et al. Opioid claims prior to elective total joint arthroplasty and risk of prolonged postoperative opioid claims. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29:e1254–e1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katzman C, Harker EC, Ahmed R, et al. The association between preoperative opioid exposure and prolonged postoperative use. Ann Surg. 2021;274:e410–e416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Characteristics of Initial prescription episodes and likelihood of long-term opioid use-United States, 2006-2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:266–269.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodgers J, Cunningham K, Fitzgerald K, et al. Opioid consumption following outpatient upper extremity surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson SP, Chung KC, Zhong L, et al. Risk of prolonged opioid use among opioid-naïve patients following common hand surgery procedures. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41:947.e3–957.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, et al. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reid DBC, Shah KN, Ruddell JH, et al. Effect of narcotic prescription limiting legislation on opioid utilization following lumbar spine surgery. Spine J. 2019;19:717–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vance A, Schuster L. Opioid addiction is a national crisis. and it is twice as bad in Massachusetts. 2018. Available at https://www.bostonindicators.org/-/media/indicators/boston-indicators-reports/report-files/opioids-2018.pdf?la=en&hash=82606AB8DC4B6AC57B5E462A43E008B63EDBF903. Accessed January 24, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steen T, Lirk PB, Sigurdsson MI. The demographics of persistent opioid consumption following limb amputation. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2020;64:361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaveri S, Nobel TB, Khetan P, et al. Risk of chronic opioid use in opioid-naïve and non-naïve patients after ambulatory surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:688–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17:131–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett KG, Harbaugh CM, Hu HM, et al. Persistent opioid use among children, adolescents, and young adults after common cleft operations. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29:1697–1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harbaugh CM, Lee JS, Hu HM, et al. Persistent opioid use among pediatric patients after surgery. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20172439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson AB, Grazal CF, Balazs GC, et al. Can predictive modeling tools identify patients at high risk of prolonged opioid use after ACL reconstruction? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478:0–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khazi ZM, Shamrock AG, Hajewski C, et al. Preoperative opioid use is associated with inferior outcomes after patellofemoral stabilization surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28:599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]