Abstract

This study of Medicare claims data examines the prescribing of antibiotics to older US patients who had outpatient visits for COVID-19 in an effort to address unnecessary antibiotic use for viral infections.

Antibiotics are ineffective treatment for viral syndromes, including COVID-19. We characterized antibiotic prescribing in older adults with outpatient COVID-19 visits to identify opportunities to improve prescribing practices.

Methods

We used 100% Medicare carrier claims and Part D event files to identify beneficiaries with a COVID-19 outpatient visit and associated antibiotic prescriptions. We included beneficiaries aged 65 years and older who had fee-for-service plus Part D coverage and a visit during April 2020 to April 2021. We identified telehealth visits with Current Procedural Terminology codes1 and in-person visits (office, urgent care, and emergency department [ED]) with place-of-service codes. To identify visits with a primary diagnosis of COVID-19, we first limited them to those with International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision diagnosis code U07.1. We then excluded visits with additional diagnosis codes for conditions for which antibiotics are always or sometimes appropriate based on clinical guidelines using a previously described tiered system.2 Visits were then linked to an antibiotic if prescribed within 7 days before or after the visit. We reported visits by setting and month, including antibiotic classes.

We performed 2-sided χ2 tests to compare the distribution of characteristics between beneficiaries with COVID-19 who were and were not prescribed an antibiotic by age, sex, race, and prescribers’ location. This study was deemed nonhuman subjects research by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and did not require institutional review board review. Analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4. P < .05 defined statistical significance.

Results

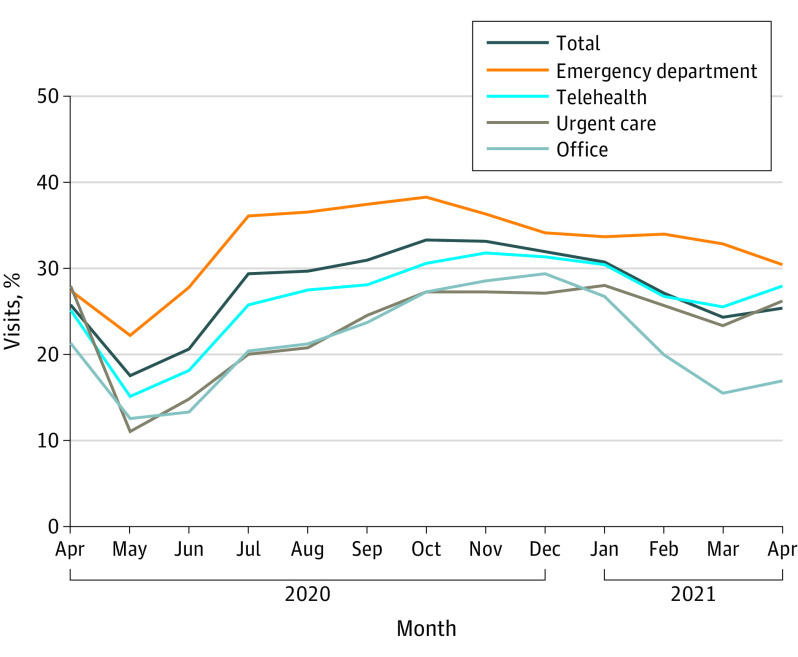

During April 2020 to April 2021, 346 204 (29.6%) of 1 169 120 COVID-19 outpatient visits were associated with an antibiotic prescription, which varied by month, with higher rates of antibiotic prescribing occurring during a wave of COVID-19 cases during the winter of 2020-2021 (range, 17.5% in May 2020 to 33.3% in October 2020) (Figure). Prescribing was highest in the ED (33.9%), followed by telehealth (28.4%), urgent care (25.8%), and office (23.9%) (Figure) visits. Azithromycin was the most frequently prescribed antibiotic (50.7%), followed by doxycycline (13.0%), amoxicillin (9.4%), and levofloxacin (6.7%). Urgent care had the highest percentage of azithromycin prescriptions (60.1%), followed by telehealth (55.7%), office (51.5%), and ED (47.4%). Differences were observed by age, sex, and location (Table). Non-Hispanic White beneficiaries received antibiotics for COVID-19 more frequently (30.6%) than other racial and ethnic groups: American Indian/Alaska Native (24.1%), Asian/Pacific Islander (26.5%), Black or African American (23.2%), and Hispanic (28.8%) (Table).

Figure. Outpatient Visits for COVID-19 and Associated Antibiotic Prescriptions Among Medicare Beneficiaries Aged 65 Years or Older, by Setting, US, April 2020 to April 2021.

The volume of COVID-19 visits differed by setting: emergency department, 525 608 (45.8% of all visits); office, 295 983 (25.3%); telehealth, 260 261 (22.3%); and urgent care, 77 268 (6.6%).

Table. Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries With COVID-19 Outpatient Visits, April 2020 to April 2021a.

| No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 visits (n = 1 169 120) | Antibiotic prescription within 7 d (n = 346 204) | |

| Age, y | ||

| 65-74 | 596 240 | 183 877 (30.8) |

| 75-84 | 392 532 | 116 927 (29.8) |

| 85-94 | 160 294 | 40 889 (25.5) |

| ≥95 | 20 054 | 4511 (22.5) |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 525 533 | 152 443 (29.0) |

| Women | 643 587 | 193 761 (30.1) |

| Race and ethnicityb | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 8680 | 2093 (24.1) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 32 380 | 8581 (26.5) |

| Black or African American | 94 833 | 22 025 (23.2) |

| Hispanic | 100 096 | 28 866 (28.8) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 903 052 | 276 257 (30.6) |

| Other | 8131 | 2182 (26.8) |

| Unknown | 21 948 | 6200 (28.2) |

| Region | ||

| South | 485 932 | 177 226 (36.5) |

| Northeast | 263 194 | 57 797 (22.0) |

| Midwest | 249 640 | 67 803 (27.2) |

| West | 170 354 | 43 378 (25.5) |

A χ2 test comparing COVID-19 visits with an antibiotic prescription within 7 days to those without an antibiotic prescription within 7 days was significantly different for all characteristics (P < .001).

Race and ethnicity were determined with the Research Triangle Institute (RTI) race code from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). This variable uses race and ethnicity as self-identified by individuals on Social Security Administration records, and then CMS classifies an additional group of beneficiaries with missing information as Hispanic or Asian to reduce the number of beneficiaries with missing race, using the RTI algorithm. “Other” was not further defined in the database. Race and ethnicity were included in this study to assess disparities in antibiotic prescribing.

Discussion

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, 30% of outpatient visits for COVID-19 among Medicare beneficiaries were linked to an antibiotic prescription, 50.7% of which were for azithromycin. Randomized clinical trials demonstrated no benefit of azithromycin in treating COVID-19,3,4 and its use for the disease has been linked to antimicrobial resistance.5 The largest number of visits and highest rates of antibiotic prescribing were observed in the ED, perhaps reflecting acuity of care, and urgent care centers had the highest rate of azithromycin prescribing. Telehealth visits had the second highest antibiotic prescribing rate and were close in volume to office visits, emphasizing the importance of optimizing antibiotic prescribing practices in this setting. Antibiotic prescribing occurred at a higher rate for non-Hispanic White beneficiaries than for those from other racial and ethnic groups. Although described in pediatrics, this racial difference has not been well characterized in older adults and warrants further evaluation because it may indicate more services are being provided to White beneficiaries, even if not indicated.6

Study limitations include that, although only visits for which COVID-19 was the primary diagnosis were included and visits with a diagnosis code that putatively justified an antibiotic were excluded, misclassification was possible. Underlying chronic medical conditions or severity of illness and subsequent hospital admission were not controlled for. These data may not be representative of the entire US population nor adults aged 65 years and older without Medicare prescription drug coverage. Data since April 2021 were not available, and strong evidence against azithromycin use was not published until the end of the observation period.

These observations reinforce the importance of improving appropriate antibiotic prescribing in outpatient settings and avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use for viral infections such as COVID-19 in older adult populations.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Associate Editor.

References

- 1.Bosworth A, Ruhter J, Samson LW, et al. Medicare beneficiary use of telehealth visits: early data from the start of COVID-19 pandemic. Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Published July 28, 2020. Accessed January 31, 2022. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//198331/hp-issue-brief-medicare-telehealth.pdf

- 2.King L, Tsay S, Hicks L, Bizune D, Hersh A, Fleming-Dutra K. Changes in outpatient antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory illness, 2011 to 2018. Antimicrob Stewardship Healthcare Epidemiol. 2021;1(1):E66. doi: 10.1017/ash.2021.230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler CC, Dorward J, Yu L, et al. ; PRINCIPLE Trial Collaborative Group . Azithromycin for community treatment of suspected COVID-19 in people at increased risk of an adverse clinical course in the UK (PRINCIPLE): a randomised, controlled, open-label, adaptive platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10279):1063-1074. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00461-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oldenburg CE, Pinsky BA, Brogdon J, et al. Effect of oral azithromycin vs placebo on COVID-19 symptoms in outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326(6):490-498. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kow CS, Hasan SS. Use of azithromycin in COVID-19: a cautionary tale. Clin Drug Investig. 2020;40(10):989-990. doi: 10.1007/s40261-020-00961-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Localio AR, et al. Racial differences in antibiotic prescribing by primary care pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):677-684. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]