Abstract

COVID-19's long-term consequences on people's mental health include social isolation, job insecurity, illness and sorrow, physical separation, and disrupted access to normal health and mental treatment. Until recently, telepsychiatry has become increasingly mainstream in the delivery of mental health services under COVID-19 and have grown significantly in Western nations. However, telepsychiatry is not generally provided in Asian countries, particularly that of SouthEast countries. In this study, the reviewer made an integrative review of the available literature, in examining the benefits and challenges of telepsychiatry services of SouthEast Asian countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. This review utilized electronic resources such as PubMED, Google Scholar, Taylor and Francis, SAGE, IEEE, Springer, ScienceDirect, Wiley, and ACM. The review covered publications published from December 1, 2019, to December 1, 2021, as well as articles published in English and translated into English. Two (2) articles were included in this review. All the papers studied are classified as having a level of evidence VI. Both publications were based on research done in the Philippines. The total sample size for all papers analyzed was 149 respondents. The telepsychiatry platforms or systems employed in investigations vary. There was no continuous usage of a single telepsychiatry platform. Each research employed a different telepsychiatry service or system, depending on the technology available in the nation where the study was done. Findings in this review show that the concept or notion of telepsychiatry services within SouthEast Asian countries is exceptionally novel and needs further research in the medical and allied health discipline. For countries that are part of the SouthEast Asia, the critical issue today is how to sustain progress and how to increase and maintain care standards, at the same time utilizing telepsychiatry services in this aspect.

Keywords: Telepsychiatry, Telemedicine, Mental health, Southeast asia

1. Background

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has had enormous and severe repercussions across the world. COVID-19 and associated limitations are having a significant mental health impact, and the need for increased and targeted mental health treatment has been highlighted as critical since the epidemic began in late 2019 (Tandon, 2020). The longer-term effects of social isolation, employment and economic uncertainty, sickness and grief, physical separation, and interrupted access to regular health and mental healthcare will resonate throughout people, and the mental health effects of COVID-19 will become more obvious (Cullen et al., 2020, Pfefferbaum and North, 2020, Talevi et al., 2020). While the impacts of COVID-19 are felt worldwide, subpopulations may be at an increased risk of harmful mental health consequences and may face hurdles to treatment (Moreno et al., 2020, Usher et al., 2020, Kumar and Nayar, 2021). Understanding the needs of these groups and developing initiatives to increase equal access to mental health treatments is critical.

Many healthcare professionals have resorted to telehealth as an effective tool to overcome the physical barrier between patients and healthcare providers to give mental healthcare to those who need it most while also limiting COVID-19 exposure (Wosik et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2020). Telehealth is described as the use of technology through audio and video telecommunications to offer healthcare across long distances, to enable information sharing between healthcare practitioners, or to provide healthcare when face-to-face contact is not feasible (Monaghesh and Hajizadeh, 2020). Telepsychiatry, which encompasses teleconsultation, teletherapy, telepsychology, telepsychotherapy, or telemental health through videoconferencing, phone discussions, and real-time chat (Beidas and Wiltsey Stirman, 2021, Di Carlo et al., 2021), is the name given to these modalities when applied to mental health.

Telepsychiatry is not a novel idea, but it was a little-known technique prior to the pandemic. According to a population study in the United States, telemedicine visits increased from 0.02 per 1000 in 2005–6.57 per 1000 in 2017, with a 38% increase in primary health care and a 56% increase in telemental health, with the highest rate increases in areas without psychiatrists (Fisk et al., 2020). Prior to COVID-19, several organizations and governments throughout the globe had recognized the promise of virtual health's ability to alter healthcare delivery, particularly boosting accessibility (O’Brien and McNicholas, 2020, Ramalho et al., 2020). Many patients and health-care practitioners have been obliged to quickly embrace telepsychiatry as a reaction to these unusual challenges because of COVID-19's social distance and stay-at-home order as tactics to limit the virus's transmission (Di Carlo et al., 2021).

Until recently, telepsychiatry has become increasingly mainstream in the delivery of mental health services under COVID-19, and have grown significantly in Western nations, including England (Hewson et al., 2021), European nations (Provenzi et al., 2020), and the United States (Pierce et al., 2021). However, telepsychiatry is not generally provided in Asian nations, particularly that of SouthEast Asian nations. By all means necessary, this integrative review was provided to examine current evidence on the benefits and challenges of telepsychiatry services of SouthEast Asian nations, namely Brunei, Myanmar, Cambodia, Timor-Leste, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

2. PICOT question

The clinical question for this integrative review was, among patients and providers (P) in SouthEast Asian nations, what are their benefits and challenges (O) of telepsychiatry services (I) during the COVID-19 pandemic (T)?

3. Method

3.1. Design

This is a comprehensive review of the available literature. During this integrative review, the researcher did the following: identifying the clinical subject of interest and findings are summarized by classifying medical and allied health implications.

3.2. Search strategy

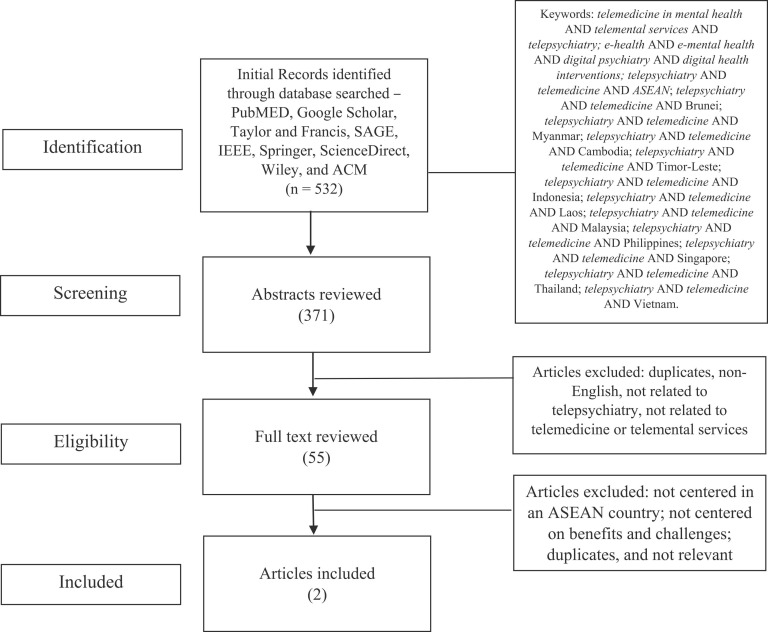

This review utilized electronic resources such as PubMED, Google Scholar, Taylor and Francis, SAGE, IEEE, Springer, ScienceDirect, Wiley, and ACM. The review covered publications published from December 1, 2019, to December 1, 2021, as well as articles published in English and translated into English. Abstracts, protocols, and opinions were eliminated, as were studies that were not centered in an SouthEast Asian country. Keywords used in the search were telemedicine in mental health AND telemental services AND telepsychiatry; e-health AND e-mental health AND digital psychiatry AND digital health interventions; telepsychiatry AND telemedicine AND SouthEast Asian; telepsychiatry AND telemedicine AND Brunei; telepsychiatry AND telemedicine AND Myanmar; telepsychiatry AND telemedicine AND Cambodia; telepsychiatry AND telemedicine AND Timor-Leste; telepsychiatry AND telemedicine AND Indonesia; telepsychiatry AND telemedicine AND Laos; telepsychiatry AND telemedicine AND Malaysia; telepsychiatry AND telemedicine AND Philippines; telepsychiatry AND telemedicine AND Singapore; telepsychiatry AND telemedicine AND Thailand; telepsychiatry AND telemedicine AND Vietnam.

3.3. Quality assessment

The researcher independently and manually assessed each article from the abovementioned electronic databases. All articles that fit the inclusion criteria were included in this integrative review. Each article must be written in basic, comprehensible English and published between December 2019 and December 2021. Further, each article must be on the telepsychiatry services and must discuss entirely its benefits and challenges. For the PICOT question, each paper must present a way in discussing the benefits and challenges of telepsychiatry services in SouthEast Asian nations amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.4. Data abstraction and data analysis

To gather data from the included articles, an assessment matrix was created. The publications were grouped and scored using an assessment matrix that includes the following information: authors and publication date, design approach, sample settings, variables and measures, research results, and degree of evidence. This review utilized the Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt (2015) Rating System for the Hierarchy of Evidence for Intervention and Treatment Questions to establish the level of evidence (LOE) for each study.

4. Results

4.1. Article/Sample characteristics

The first search for papers yielded 532 results, of which two (2) met the integrative review's inclusion and exclusion criteria (See Table 1). The researcher demonstrated the search approach via manual identification and screening (see Fig. 1). All the papers studied are classified as having a level of evidence VI. Both publications were based on research done in the Philippines. The total sample size for all papers analyzed was 149 respondents. The telepsychiatry platforms or systems employed in investigations vary. Table 2 summarizes the many benefits and challenges of telepsychiatry services. There was no continuous usage of a single telepsychiatry platform. Each research employed a different telepsychiatry service or system, depending on the technology available in the nation where the study was done.

Table 1.

Included Articles Characteristics.

| Primary author (yr.) Country | Design | Data range collection | Sample, sample size and setting | Method/instruments used | Level of Evidence (LOE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eguia and Capio (2021) Philippines | Mixed-methods triangulation design-convergence | Not clearly specified | 47 parents and 102 therapists of children with developmental disorders who were receiving teletherapy during the lockdown | Descriptive and non-parametric inferential tests; thematic analysis | LOE VII |

| Buenaventura et al. (2020) Philippines | Commentary | Not clearly specified | Older Filipinos | Narrative and descriptive | LOE VII |

Fig. 1.

Search strategy and selection of paper in benefits and challenges of telepsychiatry services in SouthEast Asian nations amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2.

Benefits and Challenges of Telepsychiatry services.

| Study | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| (Eguia and Capio, 2021) | Effective communication; flexibility of the therapist; effective preparation; family participation and preparation; reliable technology and literacy; professional preparation and support; availability of resources | Time constraints related to competing demands; limitations in resources; lack of confidence with implementing instructions; child’s disposition; difficulty with instruction and monitoring; limitations of technology; heightened physical and mental demands; limitation in understanding and participation by family members |

| (Buenaventura et al., 2020 | Can correct maladaptive behavior and negative thoughts of distress and hopelessness | Difficulty with using digital methods and videoconferencing technologies |

5. Discussion

Findings from this integrative review showed little to no evidence of telepsychiatry services within SouthEast Asian nations. It would be fair to say that the relationship of telepsychiatry services is not new in medical and allied health research, but it is relatively just developing in SouthEast Asian nations. As Eguia and Capio (2021) highlight, teletherapy in the Philippines emphasizes the need of professional growth and skill. Indeed, telehealth experts use their current professional knowledge and abilities to educate and evaluate patients. Therapists who offered teletherapy more regularly were also pleased with their communication, highlighting the value of professional expertize.

Among the benefits from the study of Eguia and Capio (2021), which tackled about teletherapy for children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Parents, more than therapists, were pleased with the teletherapy service. Parents who attended more sessions were more satisfied overall. Increasing exposure and engagement in teletherapy may have helped parents communicate more effectively. Despite this, therapists recognized unpredictable internet connections as a major teletherapy problem. The availability of equipment is also a worry since families without laptops or tablets may be unable to access telehealth services. These results show that present technical restrictions, largely tied to economic resources, may prevent greater use of teletherapy in the Philippines.

In a similar note, Buenaventura et al. (2020), looked at the mental health aspect of the older people in the Philippines during the pandemic. According to their findings, the elderly population has access to the Department of Health’s hotline for free telemedicine consultations on any medical problem. Local government units (LGUs) established a Barangay Health Emergency Response Team (BHERT) to function as a triage unit prior to referral to a hospital or an authorized COVID-19 medical facility for elderly Filipinos who are concerned about their physical health. These triage units are more accessible for elderly adults to use since they are located close to their homes. Additionally, the BHERT has the capability of dispatching a service car to help elderly patients in need.

6. Limitations

The present study included significant limitations. No ‘gray literature' or non-English publications were included. Moreover, only peer-reviewed papers from the last two (2) years were evaluated. A meta-analysis could not be conducted owing to differences in research conditions, sample sizes, and sample types. The studies’ generalizability was also restricted.

7. Conclusion

This integrative review presented additional support on the benefits and challenges of telepsychiatry services in SouthEast Asian nations during the COVID-19 pandemic. The current review’s overall results provide a hopeful image of telepsychiatry in SouthEast Asian health care settings. While research on telepsychiatry applications has proven beneficial, there is a dearth of high-quality studies, and generalizability is often confined to situations, in this review’s context – only the Philippine setting was investigated. With this, the concept or notion of telepsychiatry services (e.g. telemedicine in mental health, telemental services, e-health, e-mental health, digital psychiatry and digital health interventions) within SouthEast Asian nations is exceptionally novel and needs further research in the medical and allied health discipline. For nations that are part of the SouthEast Asian, the critical issue today is how to sustain progress and how to increase and maintain care standards, at the same time utilizing telepsychiatry services in this aspect.

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflict of Interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Beidas R.S., Wiltsey Stirman S. Realizing the promise of learning organizations to transform mental health care: telepsychiatry care as an exemplar. Psychiatr. Serv. 2021;72(1):86–88. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buenaventura R.D., Ho J.B., Lapid M.I. COVID-19 and mental health of older adults in the Philippines: a perspective from a developing country. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020;32(10):1129–1133. doi: 10.1017/S1041610220000757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen W., Gulati G., Kelly B.D. Mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM Int. J. Med. 2020;113(5):311–312. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Carlo F., Sociali A., Picutti E., Pettorruso M., Vellante F., Verrastro V., Martinotti G., di Giannantonio M. Telepsychiatry and other cutting‐edge technologies in COVID‐19 pandemic: bridging the distance in mental health assistance. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021;75(1):ijcp.13716. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguia K.F., Capio C.M. Teletherapy for children with developmental disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines: a mixed-methods evaluation from the perspectives of parents and therapists. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1111/cch.12965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk M., Livingstone A., Pit S.W. Telehealth in the context of COVID-19: changing perspectives in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(6) doi: 10.2196/19264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewson T., Robinson L., Khalifa N., Hard J., Shaw J. Remote consultations in prison mental healthcare in England: impacts of COVID-19. BJPsych Open. 2021;7(2) doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Nayar K.R. COVID 19 and its mental health consequences. J. Ment. Health. 2021;30(1):1–2. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2020.1757052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk, B.M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2015). Box 1.3: Rating system for the hierarchy of evidence for intervention/treatment questions. Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice, 11. https://library-cuanschutz.libguides.com/Evidence.

- Monaghesh E., Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during COVID-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno C., Wykes T., Galderisi S., Nordentoft M., Crossley N., Jones N., Cannon M., Correll C.U., Byrne L., Carr S., Chen E.Y.H., Gorwood P., Johnson S., Kärkkäinen H., Krystal J.H., Lee J., Lieberman J., López-Jaramillo C., Männikkö M., Phillips M.R., Uchida H., Vieta E., Vita A., Arango C. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:813–824. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien M., McNicholas F. The use of telepsychiatry during COVID-19 and beyond. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020;37(4):250–255. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B., North C.S. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383(6):510–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzi L., Grumi S., Gardani A., Aramini V., Dargenio E., Naboni C., Borgatti R. Acta Paediatrica (Oslo, Norway: 1992) 2020. Italian parents welcomed a telehealth family-centred rehabilitation programme for children with disability during COVID-19 lockdown. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho R., Adiukwu F., Gashi Bytyçi D., El Hayek S., Gonzalez-Diaz J.M., Larnaout A., Grandinetti P., Kundadak G.K., Nofal M., Pereira-Sanchez V., Pinto da Costa M., Ransing R., Schuh Teixeira A.L., Shalbafan M., Soler-Vidal J., Syarif Z., Orsolini L. Telepsychiatry and healthcare access inequities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;53 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talevi D., Socci V., Carai M., Carnaghi G., Faleri S., Trebbi E., di Bernardo A., Capelli F., Pacitti F. Mental health outcomes of the CoViD-19 pandemic. Riv. di Psichiatr. 2020;55(3):137–144. doi: 10.1708/3382.33569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon R. COVID-19 and mental health: preserving humanity, maintaining sanity, and promoting health. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;51 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usher K., Durkin J., Bhullar N. The COVID‐19 pandemic and mental health impacts. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020;29(3):315–318. doi: 10.1111/inm.12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wosik J., Fudim M., Cameron B., Gellad Z.F., Cho A., Phinney D., Curtis S., Roman M., Poon E.G., Ferranti J., Katz J.N., Tcheng J. Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020;27(6):957–962. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Snoswell C.L., Harding L.E., Bambling M., Edirippulige S., Bai X., Smith A.C. The role of telehealth in reducing the mental health burden from COVID-19. Telemed. e-Health. 2020;26(4):377–379. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]