Abstract

Cinnamic acid (CiA) and phenylpropanoid derivatives are widely distributed in plant foods. In this study, anti- and pro-oxidant properties of the derivatives and their roles in modulating cell growth were investigated. Ferulic acid, sinapinic acid, caffeic acid (CaA), and 3,4-dihydroxyhydrocinnamic acid (DHC) showed strong radical scavenging activities. They, except DHC, also performed considerable inhibitory effects on lipid peroxidation and reduced levels of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). CaA and DHC, however, produced substantial amount of H2O2 with oxidative degradation in culture conditions. CaA and DHC (> 400 μM) showed potent cytotoxic effects which were abolished by superoxide dismutase/catalase; they significantly enhanced cell growth ROS-dependently at low levels (~ 100 μM). CiA derivatives without bearing hydroxyl group did not show any appreciable antioxidant activities. The results indicate that CiA derivatives with ortho-dihydroxyl group had strong anti- and pro-oxidant properties, which also play an important role in modulating cell growth.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10068-022-01042-x.

Keywords: Cinnamic acid derivative, Phenylpropanoid, Antioxidant, Prooxidant, Reactive oxygen species, Cell growth

Introduction

Phenolic compounds in edible plants provide various beneficial health effects (Karakaya, 2004). A number of studies have demonstrated that these natural dietary phenolics have antioxidant, anti-microbial, anti-inflammatory as well as anti-carcinogenic effects (Costea et al., 2018; Mandal et al., 2017; Yahfoufi et al., 2018; Zheng and Wang, 2001). One of the most widespread structures is cinnamic acid (CiA) related phenylpropanoid compounds. Phenylpropanoids are synthesized from amino acids including phenylalanine and tyrosine in plants and have a structure with C6 phenyl and C3 propane groups (Vogt, 2010). Hydroxycinnamic acids, the simplest structure of phenylpropanoids converted by hydroxylation and/or methoxylation of phenylalanine include coumaric acid, ferulic acid (FeA), caffeic acid (CaA) as well as sinapinic acid (SiA) (Coman and Vodnar, 2020). CiA and its derivatives occur naturally in many crops and edible plant sources and have been used as a food additive and a natural antioxidant in beverages and cosmetics (Gunia-Krzyzak et al., 2018). FeA has an antioxidant potential showing scavenging activities against various types of free radicals (Graf, 1992; Kikuzaki et al., 2002). It also protects oxidative damage in diabetic rats by inhibiting formation of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) and hydroperoxides (Balasubashini et al., 2004). The other structurally-related phenylpropanoid compounds including CaA, SiA, and 3,4-dihydroxyhydrocinnamic acid (DHC) found in many dietary plant sources, have also shown a wide range of biological activities including inhibition of carcinogenic, inflammatory and atherosclerotic processes (Huang et al., 1988; Kampa et al., 2004; Nardini et al., 1995). The biological activities of CiA and its derivatives have been also reported in animal models; they have been known to prevent diabetic complications (Adisakwattana et al., 2008), and to enhance cognitive functions with reduction of amyloid plaque pathology (Chen et al., 2008; Chandra et al., 2019).

Whereas these phenolic compounds showed antioxidant properties (Graf, 1992; Kikuzaki et al., 2002; Zheng and Wang, 2001), several studies have also demonstrated that they have pro-oxidant potential (Bourne and Rice-Evans, 1997; Cao et al., 1997). It is reported that reactive oxygen species (ROS) can be generated from many types of phenolic compounds in food and body systems. Rapid formation of ROS from phenolic compounds is responsible for inducing apoptosis in several cultured cells (Hong et al., 2007; Mortezaee et al., 2019; Thayyullathil et al., 2008). Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), a major green tea polyphenol, induced apoptotic cell death through generation of ROS in cultured cells (Hwang et al., 2007). Conversely, it was also reported that ROS from EGCG played a crucial role in stimulating cell proliferation and survival in human keratinocytes (Chung et al., 2003). We also reported that garcinol and related compounds showed potent cytotoxic effects, whereas they also showed ROS-dependent stimulatory effects on the growth of the intestinal cells (Hwang et al., 2007). Accordingly, ROS generated from phenolic compounds could regulate the balance of death or growth of cells through modulating various intracellular signaling pathways.

Various bioactivities of CiA derivatives and its related phenylpropanoids have been investigated. There is, however, little research performed regarding understanding of their structure-related anti- and pro-oxidant properties and the consequent effects in modulating cell growth and death. In the present study, we compared anti- or pro-oxidant potentials of CiA derivatives and its related phenylpropanoids including trans- CiA, 3-methoxycinnamic acid (3MC), 3,4-dimethoxycinnamic acid (DMC), and 3,4,5-trimethoxycinnamic acid (TMC), FeA, SiA, CaA and DHC. We also investigated a relationship between their structures and cytotoxic activities derived from their properties of ROS generation.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and cell lines

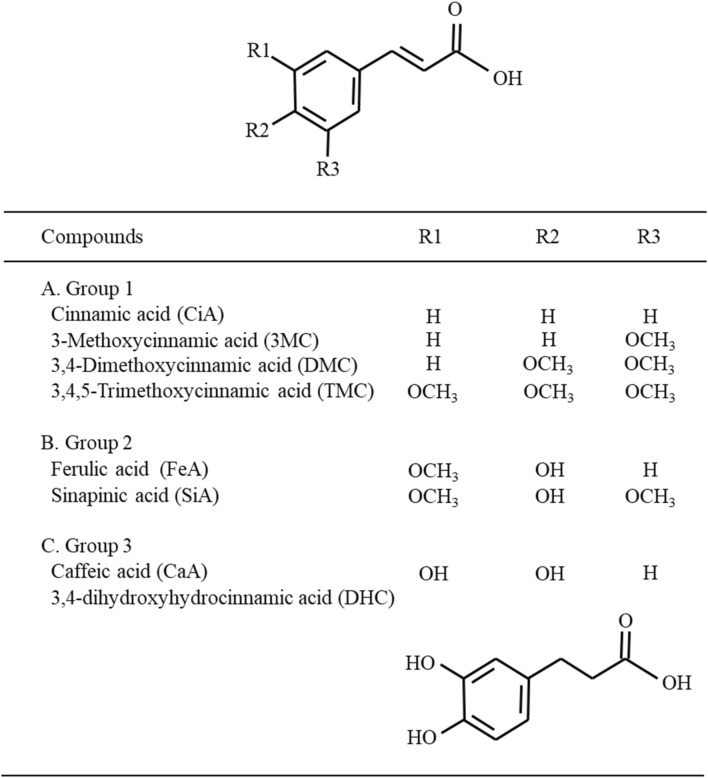

CiA derivatives and its structurally-related phenylpropanoids including CiA, 3MC, DMC, TMC, FeA, CaA, SiA, and DHC were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Their chemical structures and grouping according to structural similarity are shown in Fig. 1. The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) was purchased from Amresco Inc. (Solon, OH, USA). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. unless stated otherwise. HCT 116 human colon adenocarcinoma cells, INT 407 human immortalized intestinal cells and IEC-6 normal immortalized rat intestinal epithelial cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). HCT 116, IEC-6, and INT 407 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640, DMEM, and MEM, respectively, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 unit/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin. In MEM medium, 1% MEM non-essential amino acids were also added. The cells were kept at 37 °C in 95% humidity and 5% CO2.

Fig. 1.

Structures of CiA and phenylpropanoid derivatives used in this study

Assays for radical scavenging activity and inhibition of lipid peroxidation

Scavenging activity against 2,2-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical was evaluated by the method of Brand-Williams et al. (1995) with a slight modification. One hundred μL of DPPH (600 μM) dissolved in methanol was added to an equal volume of each compound in methanol or 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 8) and incubated for 30 min in a dark place at room temperature. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a microplate reader (Spectra Max 250, Molecular device, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The 2,2′-azinobis-(3-ethyl-benz-thiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) radical scavenging activity was done according to the method of Re et al. (1999). The ABTS·+ radical solution was generated with 10 mM ABTS and 10 mM potassium persulfate (74:26, v/v) at 37 °C in a dark place for overnight before use. The ABTS stock solution was diluted 5 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to an absorbance of 0.7–1.0 at 734 nm. The ABTS working solution was then added to samples and incubated for 30 min in a dark place. The absorbance was measured at 734 nm using a microplate reader (Spectra Max 250). Nitrite scavenging activity was measured by Griess reaction (Marcocci et al., 1994). Sodium nitrite (100 μM) was mixed with different concentrations of compounds, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C in a dark place. After 1 h, the Griess reagent (equal volume of 1% sulfanilamide dissolved in 5% H3PO4 and 0.1% N-1-naphthylenthylenediamine dihydrochloride) was added to each sample. After 10 min, the absorbance was measured at 540 nm (Spectra Max 250). Superoxide anion radical scavenging effect was performed according to the method of Wenli et al. (2001). Luminol (50 μM) dissolved in 10 mM carbonate buffer (pH 10.3) was added to sample solution. Pyrogallol (200 μM) was then added and the luminescence intensity was measured using a microplate reader (Triad LT, Dynex Technologies Inc., Chantilly, VA, USA).

Effects on lipid peroxidation of the derivatives were analyzed measuring the formation of TBARS from linoleic acid oxidation induced by ascorbic acid/FeSO4 (Liu and Ng, 2000). The 0.4% linoleic acid in 0.8% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 2 mM ascorbic acid, and 0.2 mM FeSO4 were added to different concentrations of each compound one after another. After incubation at 37 °C for 1 h, the reactant was added to 1 M trichloroacetic acid, followed by 0.8% TBA. The reaction was terminated by adding the 20 μL of 5% BHT. After heating at 100 °C for 5 min and cooled to room temperature. The absorbance was detected at 532 nm using a microplate reader (Spectra Max 250).

Measurement of intracellular ROS

Levels of intracellular ROS were determined using 2′,7′-dichloro-fluorescence diacetate (DCFH-DA) (Osseni et al., 1999). HCT 116 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 104 cells per well and replaced the next day by serum-free medium. After 24 h incubation, the cells were treated for each compound for 1.5 h. After removing the compound-containing medium, the cells were stained with DCFH-DA (20 μM) in PBS for 30 min. The fluorescence intensity was detected using a microplate reader (Spectra Max M3, Molecular device) with an excitation at 485 nm and an emission at 535 nm. To analyze protective effects of the CiA derivatives against H2O2-induced oxidative stress, the cells were treated with each compound for 1.5 h first, and then replaced with H2O2 (500 μM). After 30 min, the medium containing H2O2 was removed, the cells were incubated with DCFH-DA (20 μM) in PBS at 37 °C for 1 h. The fluorescence was detected using a microplate reader (Spectra Max M3).

Determination of H2O2 formation and oxidative compounds

H2O2 levels generated from the compounds were measured using ferrous oxidation-xylenol orange (FOX) assay (Jiang et al., 1990). Each compound was incubated in PBS or distilled water (DW) at 37 °C, and 40 μL of the sample was mixed with the 160 μL of FOX working solution containing 100 μM xylenol orange, 200 mM D-sorbitol, and 500 μM ammonium ferrous sulfate at indicated time point. After 40 min, the H2O2 levels were analyzed measuring absorbance at 550 nm using a microplate reader (Triad LT). For analyzing oxidative products from FeA, SiA, CaA, and DHC, each compound (400 μM) in PBS were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h and the absorbance at 405 nm was detected using a microplate reader (Triad LT).

Evaluation of cytotoxic properties

Cytotoxic effects on HCT 116, INT 407 and IEC-6 cells were determined using the MTT assay (Hong, 2007). The cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 104 cells per well and treated the next day with each compound. After 24 h, compound-containing medium was removed, and the fresh medium containing 0.5 mg/mL MTT was added. The cells were further incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The medium was then removed and replaced by DMSO, and the absorbance was measured at 550 nm using a microplate reader (Triad LT). For analyzing growth modulatory effects by ROS, each compound with or without superoxide dismutase (SOD) (15 unit/mL) and catalase (30 unit/mL) or 1 mM EDTA were applied to cells. For evaluating cytotoxic activity of the oxidation products from CaA and DHC, different concentrations of these compounds were incubated in cell and serum free medium for 24 h at 37 °C. The pre-incubated medium was then, added to cells in the absence or presence of SOD and catalase, and were incubated with cells for further 24 h.

Data analysis

All values represent the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). Statistical significance was evaluated by the two-tailed Student’s t-test. For comparing multiple samples, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s honestly significant difference test was used (SPSS, version 21.0, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results and discussion

Antioxidant properties of CiA and related phenylpropanoids

A total of eight compounds were categorized into three groups based on the number of hydroxyl group in the ring structure (Fig. 1). The compounds with no hydroxyl group such as CiA, 3MC, DMC, and TMC were included in group 1. The compounds bearing one (FeA and SiA) and double (CaA and DHC) hydroxyl group attached to the benzene ring belonged to group 2 and 3, respectively.

First, scavenging activities of these compounds against DPPH, ABTS, and superoxide anion radical as well as nitrite were measured. The compounds in group 1 did not show any significant scavenging effects on DPPH, ABTS, superoxide radicals, and nitrite up to 100 μM (Supplementary Fig. 1S), while compounds in groups 2 and 3 showed relatively strong scavenging activities. Their IC50 (concentration that causes 50% inhibition) values were calculated based on concentration-dependent activity (Table 1). The compounds in group 3 displayed strong radical scavenging action against DPPH and nitrite with generally lower IC50 values than the compounds in group 2.

Table 1.

The IC50 values (μM) of CiA derivatives for scavenging radicals and inhibitory effects on lipid peroxidation

| DPPH | ABTS | Superoxide | Nitrite | Lipid peroxidation2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeOH | pH 8 | Fold1 | |||||

| FeA | 70.7 ± 2.3d3 | 242.1 ± 32.1ab | 3.42 | 16.7 ± 0.9a | 13.7 ± 2.0b | 22.9 ± 1.2b | 228.0 ± 10.0b |

| SiA | 45.8 ± 0.3c | 188.3 ± 26.2ab | 4.11 | 43.1 ± 1.6c | 6.13 ± 0.7a | 37.2 ± 1.6c | 173.5 ± 2.5a |

| CaA | 27.7 ± 0.3b | 266.7 ± 31.5b | 9.63 | 25.4 ± 4.8b | 15.6 ± 1.6b | 14.7 ± 1.2a | 139.3 ± 12.8a |

| DHC | 15.3 ± 1.1a | 302.4 ± 22.8b | 19.8 | 14.6 ± 1.9a | 33.7 ± 4.2c | 16.2 ± 1.5a | 490.3 ± 45.3c |

1Fold difference in IC50 values between methanol and buffer conditions

2Inhibitory effects of CiA derivatives (80 μM) on oxidation of linoleic acid induced by ascorbic acid/FeSO4 were analyzed

3Different letters indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05) based on one-way ANOVA and the Tukey’s HSD test

DPPH radical scavenging activities of the compounds were analyzed in two different dilution solvent including methanol and pH 8 phosphate buffer. Since many phenolic compounds are not stable in alkaline conditions, changes in their antioxidant activity in pH 8 were measured. Interestingly, DPPH radical scavenging activities of all 4 compounds in group 2 and 3 were drastically reduced in pH 8; the decrease in activity was much more pronounced in group 3 compounds. The results indicate that compounds with double hydroxyl group are much less stable in alkaline conditions and lose their activities easily.

Together, the existence of hydroxyl group in a benzene ring is critical for performing the antioxidant potential. The structures with double hydroxyl groups in the benzene ring appear to have more potent reduction potential and play a better role for scavenging radicals, whereas they are easily docomposed in alkaline conditions.

The effects of the phenylpropanoid derivatives on lipid peroxidation were also evaluated (Table 1). In this experiment, oxidation of linoleic acid was induced by ascorbic acid/FeSO4 through the Fenton reaction and the formation of oxidative products reacting with 2-thiobarbituric acid (TBARS) was detected. FeA, SiA, and CaA at 80 μM inhibited lipid peroxidation significantly by 22–33% (Supplementary Fig. 2S). The hydroxyl group in their ring structure appeared to be importantly involved in the inhibitory effects; it is consistent with their radical scavenging effects except DHC which did not show the inhibition. These three compounds, FeA, SiA, and CaA, also inhibited lipid peroxidation in a concentration-dependent manner, and CaA showed the most potent inhibitory effect (Table 1). Interestingly, DHC at 80 μM did not show a significant inhibitory effect on the lipid peroxidation, and its effect was much less pronounced in this system as compared to its scavenging effects on other radicals. CaA contains α, β-unsaturated group in the side chain, while DHC, a metabolite product of CaA, contains no α, β-unsaturated group (Fig. 1). Our results demonstrated that the hydroxyl group in the benzene ring is essential for radical scavenging effects. However, the role of α, β-unsaturated group has not been fully investigated. It is unlikely that α, β-unsaturated group has a role to scavenge DPPH, ABTS, and nitrite, since DHC showed comparable or higher radical scavenging effects than CaA (Table 1). It should also be noted that DHC was much less effective than other 3 compounds in scavenging superoxide (Table 1). Therefore, α,β-unsaturated group might play a crucial role in inhibition of superoxide radical and lipid peroxidation process in the current condition; the precise mechanism needs to be explored further. Metal chelating effect is also important for inhibiting lipid peroxidation induced by the Fenton reaction. There is no ferrous-ion chelating activity observed up to 200 μM of these compounds (Supplementary Fig. 2S). These results indicate that the inhibitory effects of the phenylpropanoid derivatives on lipid peroxidation are solely attributable to their radical scavenging or reducing effects rather than metal chelating activities (Andjelković et al., 2006).

Recent studies showed that these cinnamic acid derivatives modulate antioxidant molecules and their signalings to control intracellular radicals. Caffeic acid phenylester has been shown to upregulate antioxidant enzymes by promoting the translocation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), into nucleus (Yang et al., 2017). FeA supplementation was shown to increase protein and mRNA levels of antioxidant molecules such as catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione (GSH) (Wang et al., 2020). SiA improved cardiac function by activating Nrf2 signaling (Raish et al., 2021).

Effects on intracellular ROS levels

In order to know whether the antioxidant activities of the CiA and phenylpropanoid derivatives are also effective in cells, HCT 116 human colon cancer cells were incubated with the compounds, and changes in intracellular ROS levels were measured using a cell-permeable DCFH-DA fluorescence probe. Figure 2A showed that FeA, SiA, CaA, and DHC decreased the levels of intracellular ROS significantly at 400 μM; their effects except FeA were also significant even at 100 μM. Compounds in group 3 appeared to be more effective in decreasing intracellular ROS than group 2.

Fig. 2.

Effects of CiA and phenylpropanoid derivatives on intracellular ROS level. HCT 116 cells were treated with each compound for 90 min (A) or were incubated with each derivative first, and treatment was replaced with H2O2 (500 μM) for 30 min (B). Intracellular ROS levels were observed by measuring fluorescence from added DCFH-DA (20 μM) with excitation at 485 nm and an emission at 535 nm. Each value represents the mean ± SD (n = 8). *,** significantly different from the corresponding control according to Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05; **, ##p < 0.01)

The effects of these compounds on intracellular ROS levels under the condition of oxidative stress were also investigated (Fig. 2B). Treatment of 500 μM H2O2 for 30 min resulted in the increase of intracellular ROS levels by 40% than H2O2-untreated cells. Pre-treatment of FeA, SiA, CaA, and DHC for 90 min decreased the H2O2-induced intracellular ROS levels significantly by 10–40%. CiA without hydroxyl group in the bezene ring at both 100 and 400 μM had neither activity (Fig. 2A and B). Together, our results explain the compounds in group 2 and 3 bearing hydroxyl group able to suppress H2O2-induced oxidative stress in HCT 116 cells.

Generation of ROS from phenylpropanoids, their auto-oxidation and cytotoxic activity

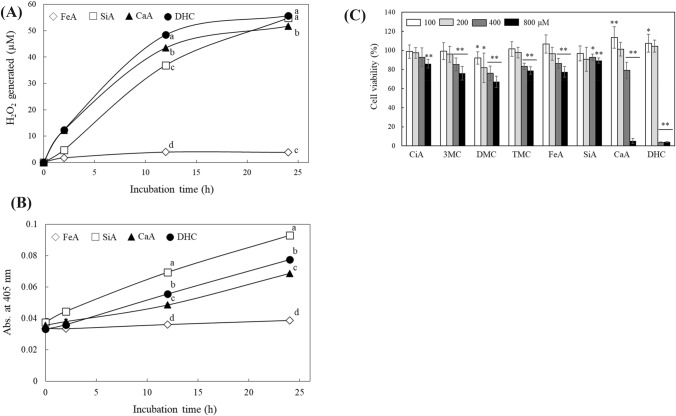

Previous reports have indicated that many polyphenol compounds have not only anti-oxidative but also pro-oxidative properties (Fukumoto and Mazza, 2000). Therefore, we measured the capacity of ROS generation from compounds in group 2 and 3. At a physiological pH 7.4, ROS detected as H2O2 was rapidly generated from group 3 compounds, CaA and DHC, and the levels were increased time-and concentration dependently (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Table 1S). The amount reached at 51.7 and 55.7 μM from 400 μM of CaA and DHC after 24 h-incubation, respectively. Group 2 compounds, SiA produced significantly less amount of H2O2 initially than group 3 compounds; it showed a delayed phase up to 12 h, and then the level of H2O2 rapidly reached at comparable amount of group 3 compounds after 24 h. Group 1 compounds without hydroxyl group did not show an ability of H2O2 production (Supplementary Table 1S).

Fig. 3.

H2O2 generation, formation of oxidative products from phenylpropanoid derivatives, and their cytotoxic properties. H2O2 levels (μM) from FeA, SiA, CaA, and DHC (each 400 μM) were detected at indicated time points (A). Formation of their oxidative products was also monitored at 405 nm (B). Cytotoxic effect of each compound on HCT 116 cells were also evaluated using the MTT assay (C). Each value represents the mean ± SD (n = 4 in A and B, n = 8–24 in C). Different letters indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05) based on one-way ANOVA and the Tukey’s HSD test (in A and B). *,** significantly different from its corresponding control according to Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 in c)

Generation of ROS from polyphenols concurrently occurs with auto-oxidation, which results in the formation of oxidation products with yellowish-brown color. We observed the formation of the oxidation products with a peak absorbance at around 400 nm from group 3 compounds that generate a significant amount of ROS (Supplementary Fig. 3S). FeA did not cause an obvious color change detected at 400–700 nm. DHC was converted to the pink-colored oxidation products showing a broad absorbance peak from 400 to 550 nm (Supplement Fig. 3S). Then we next detected the formation of the oxidation products of FeA, SiA, CaA, and DHC measuring absorbance at 405 nm (Fig. 3B). Absorbances of all compounds except FeA increased gradually during 24 h-incubation; SiA showed the highest increase. Even though the color development from the oxidation products was not exactly correlated to the amount of ROS levels, we were able to confirm that the generation of ROS was accompanied by oxidation of these phenylpropanoids.

The compounds incubated in DW showed no considerable changes in color during 24 h, and H2O2 generated from these compounds in DW did not reach detectable levels even at 24 h-incubation (Supplementary Table 1S). It has been reported that ROS generation from polyphenols is due to the direct reduction of oxygen molecules by them (Eghbaliferiz and Iranshahi, 2016). Therefore, compounds in group 3 having higher reduction potential could produce a higher amount of ROS. In the case of SiA, it is believed that it initially exists a single hydroxyl group, and as oxidation progresses, one or both methoxyl groups of its ring structure might be converted to hydroxyl group resulting in a rapid ROS generation similar to group 3 compounds. The phenylpropanoids are, however, relatively stable in acidic pH and DW; the oxidation and H2O2 generation of phenolic compounds did not proceed easily and initiated under alkaline conditions.

Many plant-derived polyphenolic compounds have reported that they could induce cell death and regulate cell growth in various types of cells including cancer cells (Khan et al., 2012). ROS generated from polyphenols have known to be an important regulatory factor for the action (Mileo and Miccadei, 2016). The HCT 116 human colon adenocarcinoma, INT 407 human embryonic intestinal, and IEC-6 normal immortalized rat intestinal cells were used for evaluating cytotoxic effects of the compounds. All compounds in groups 1 and 2 showed low cytotoxic activity (The IC50 of these six compounds was > 1000 μM in all 3 cell lines). CaA and DHC in group 3, however, showed stronger cytotoxic activities as compared to group 1 and 2 compounds. They reduced the cell viability dose-dependently in both cancer and normal cells (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Fig. 4S). DHC almost completely abolished the growth of all 3 cell lines at > 400 μM, while CaA caused 10–40% cell death at 400 μM depending on cells. The IC50 values of DHC against HCT 116, INT 407 and IEC-6 cells were 312, 232 and 273 μM, respectively. These findings demonstrate that the more ROS were generated, the higher cell toxicities of the compouds were presented.

Interestingly, although no ROS generation was detected from the compounds in group 1, their appreciable inhibitory effects on cell growth were observed (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Fig. 4S). These inhibitory effects were comparable with or stronger than those of group 2 compounds suggesting different underlying mechanisms other than regulation of ROS generation on inhibition of cell growth by phenylpropanoid derivatives. Previous studies have dealt with the effects of CiA and its derivatives (group 1 compound) as a histone deacetylase inhibitor which induces cancer cell cycle arrest and cell death (Anantharaju et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2016). This could be the reason the compounds in group 1 showed comparable inhibition effects on cell growth.

Involvement of ROS for inducing cell death and growth

The relationship between the cytotoxicity induced by group 2 and 3 compounds and ROS was investigated. The antioxidant enzymes, SOD/catalase, were added to the cell culture system, and changes in cytotoxicity were observed to test whether SOD/catalase alleviates the phenylpropanoid derivatives-induced cell toxicity. Group 3 compounds, CaA and DHC, showed potent cytotoxic effects on HCT 116 cells compared to group 2 compounds, FeA and SiA, in the absence of SOD/catalase at both 400 and 800 μM (Fig. 4A), which were consistent to the results of Fig. 3C. The cytotoxic activities of CaA and DHC were almost completely abolished when co-incubated with SOD (15 unit/mL) and catalase (30 unit/mL) (Fig. 4A). Since SOD/catalase are involved in ROS detoxification, the generation of ROS is believed to be a major factor to induce cell death.

Fig. 4.

Modulatory effects on cell death and growth of phenylpropanoid derivatives by SOD/catalase, EDTA and their oxidation status. HCT 116 cells were incubated with FeA, SiA, CaA, and DHC (400 and 800 μM) in the presence or absence of SOD (15 unit/mL)/catalase (30 units/mL) (A) or of 1 mM EDTA (B) for 24 h. Each value represents the mean ± S.D. (n = 8). Cell growth modulation of CaA and DHC (C) up to 200 μM and their oxidation products (pre-incubation at 37 °C for 24 h) (D) in the absence or presence of SOD/catalase was also analyzed. Each value represents the mean ± S.D. (n = 8). *,**Significantly different from its corresponding control according to Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01)

Modulation of cell viability by group 2 compounds in the presence of SOD/catalase was presented somewhat differently. The toxicity of SiA (800 μM) was reduced by SOD/catalase, but it was rather enhanced at 400 μM. Similar changes in cell viability were also observed in FeA despite no statistical significance. It should be noted that ROS generation from polyphenols was accompanied by their structural degradation. In addition to removing superoxide anion, SOD could exert its role for chemical stabilization of polyphenols by blocking radical chain reaction (Perron and Brumaghim, 2009). Enhancement of SiA activity at 400 μM in the presence of SOD/catalase might be because sinapinic aicd was stabilized by SOD, and its structure-related cytotoxic mechanisms were presented. At 800 μM, it is believed that ROS-dependent mechanism plays an important role for inducing cytotoxicity.

ROS in biological systems can be converted to various forms including superoxide, hydroxyl radical (·OH) as well as H2O2. Especially, highly reactive hydroxyl radical is produced by the reduction of H2O2 in the presence of metal ion through the Fenton reaction (Lloyd et al., 1997). In the present study, ROS-induced cytotoxic properties by CaA and DHC were measured using ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), a known metal chelator (Fig. 4B). DHC-induced cytotoxic activity was significantly reduced in the presence of EDTA. The effect of EDTA was much less pronounced in modulating the activity of CaA. The results suggest that ROS generated from DHC is ultimately converted to hydroxyl radical which is mainly involved in cell death. DHC was involved not only in ROS generation but also in the recycle of metal ions that play an important role in the formation of hydroxyl radicals through the Fenton reaction. It is likely that CaA inhibits the lipid peroxidation by scavenging ·OH radical from the Fenton reaction and showed the strongest activity in inhibiting lipid peroxidation shown in Table 1. DHC might stimulate the ·OH formation through regeneration of metal ion in the Fenton reaction due to its reduction property; it can be a reason why DHC, a strong reducing agent, showed little inhibitory activity on lipid peroxidation induced by the Fenton reaction shown in Table 1 and supplementary Fig. 2S.

Significant growth stimulation was observed in cells treated with certain phenylpropanoid derivatives, especially group 3 compounds at 100 μM (Fig. 3C). To understand this phenomenon in detail, effects of CaA and DHC were investigated on growth of HCT 116 cells up to 200 μM. The growth stimulation of cells by CaA and DHC was significantly pronounced by 20–30% especially in a range of 80–100 μM. The stimulating effects were, however, abolished in the presence of SOD/catalase (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that the amount of ROS generated from lower concentrations of CaA and DHC could stimulate cell growth rather than cell death. A previous study demonstrated that a low concentration of ROS may increase cell growth and activate cell division-related signaling as a secondary messenger (Davies, 1999). It has also indicated that ROS plays dual roles for cell growth, either stimulation of cell proliferation or induction of growth arrest and cell death depending on the concentration (Valko et al., 2006). Together, our results suggest that a low amount of ROS generated from a low concentration of phenylpropanoids may stimulate cell growth; a high amount of ROS, however, induces cell death.

Rapid generation of ROS by CaA and DHC should be accompanied by their rapid oxidative degradation. A question was raised whether their oxidative products might be involved in stimulating cell growth. To answer this question, CaA and DHC were pre-incubated in cell-free media at 37 °C for 24 h, and the media containing their oxidative products were treated to HCT 116 cells. The pre-incubated CaA and DHC showed potent cytotoxic effects without stimulating cell growth even at low concentrations (Fig. 4D). The effect shown by the pre-incubated compounds was stronger than those of the fresh compounds inducing 70–80% of cell death even at 200 μM. These strong cytotoxic effects were, however, almost completely abolished by concomitant treatment of SOD/catalase. It is believed that ROS from CaA and DHC were accumulated during pre-incubation, and the high concentrations of ROS caused cell death directly. The oxidative degradation products of CaA and DHC were, however, not involved in either growth stimulation or cell death.

In conclusion, CiA and phenylpropanoid derivatives bearing hydroxyl groups have both anti- and pro-oxidant potentials. The activities were more pronounced in compounds with double hydroxyl groups. CaA and DHC, however, produced a substantial amount of ROS which was mainly responsible for their cytotoxic activities. A lower amount of ROS generated from these compounds, however, induced growth stimulatory effects on cells. The present study indicates that phenylpropanoid derivatives with an ortho-dihydroxyl group show both strong anti- and pro-oxidant properties, which are also involved in modulating cell growth and death.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant (NRF-2019R1A2C1089617 and 2021R1F1A1051466) funded by the Korea government (MSIT).

Abbreviations

- ABTS

2,2′-Azinobis-(3-ethyl-benz-thiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)

- CiA

trans-Cinnamic acid

- DCFH-DA

2′,7′-Dichloro-fluorescence diacetate

- DHC

3,4-Dihydroxyhydrocinnamic acid

- DMC

3,4-Dimethoxycinnamic acid

- DPPH

2,2-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl

- DW

Distilled water

- EDTA

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- H2O2

Hydrogen peroxide

- MTT

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- TBARS

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

- TMC

3,4,5-Trimethoxycinnamic acid

- FOX

Ferrous oxidation-xylenol orange

- 3MC

3-Methoxycinnamic acid

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hyeon-Son Choi, Email: hsc1970@smu.ac.kr.

Jungil Hong, Email: hjil@swu.ac.kr.

References

- Adisakwattana S, Moonsan P, Yibchok-Anun S. Insulin-releasing properties of a series of cinnamic acid derivatives in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry. 2008;56:7838–7844. doi: 10.1021/jf801208t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharaju PG, Reddy DB, Padukudru MA, Chitturi CMK, Vimalambike MG, Madhunapantula SV. Induction of colon and cervical cancer cell death by cinnamic acid derivatives is mediated through the inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDAC) PloS One. 2017;12:0186208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andjelković M, Van Camp J, De Meulenaer B, Depaemelaere G, Socaciu C, Verloo M, Verhe R. Iron-chelation properties of phenolic acids bearing catechol and galloyl groups. Food Chemistry. 2006;98:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.05.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubashini MS, Rukkumani R, Viswanathan P, Menon VP. Ferulic acid alleviates lipid peroxidation in diabetic rats. Phytotherapy Research. 2004;18:310–314. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne LC, Rice-Evans CA. The effect of the phenolic antioxidant ferulic acid on the oxidation of low density lipoprotein depends on the pro-oxidant used. Free Radical Research. 1997;27:337–344. doi: 10.3109/10715769709065771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier ME, Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 1995;28:25–30. doi: 10.1016/S0023-6438(95)80008-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G, Sofic E, Prior RL. Antioxidant and prooxidant behavior of flavonoids: Structure-activity relationships. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1997;22:749–760. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(96)00351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Roy A, Jana M, Pahan K. Cinnamic acid activates PPARto stimulate lysosomal biogenesis and lower amyloid plaque pathology in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Neurobiology of Disease. 2019;124:379–395. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Zhu J, Mo J, Yang H, Jiang X, Lin H, Gu K, Pei Y, Wu L, Tan R. Synthesis and bioevaluation of new tacrine-cinnamic acid hybrids as cholinesterase inhibitors against Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;33:290–302. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2017.1412314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung JH, Han JH, Hwang EJ, Seo JY, Cho KH, Kim KH, Youn JI, Eun HC. Dual mechanisms of green tea extract (EGCG)-induced cell survival in human epidermal keratinocytes. FASEB Journal. 2003;17:1913–1915. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0914fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coman V, Vodnar DC. Hydroxycinnamic acids and human health: recent advances. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2020;100:483–499. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.10010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costea T, Hudita A, Ciolac OA, Galateanu B, Ginghina O, Costache M, Ganea C, Mocanu MM. Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer by dietary compounds. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19:3787. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies KJ. The broad spectrum of responses to oxidants in proliferating cells: a new paradigm for oxidative stress. IUBMB Life. 1999;48:41–47. doi: 10.1080/713803463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eghbaliferiz S, Iranshahi M. Prooxidant activity of polyphenols, flavonoids, anthocyanins and carotenoids: updated review of mechanisms and catalyzing metals. Phytotherapy Research. 2016;30:1379–1391. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto LR, Mazza G. Assessing antioxidant and prooxidant activities of phenolic compounds. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2000;48:3597–3604. doi: 10.1021/jf000220w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf E. Antioxidant potential of ferulic acid. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1992;13:435–448. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90184-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunia-Krzyzak A, Sloczynska K, Popiol J, Koczurkiewicz P, Marona H, Pekala E. Cinnamic acid derivatives in cosmetics: current use and future prospects. International Journal of Cosmetic Science. 2018;40:356–366. doi: 10.1111/ics.12471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J. Curcumin-induced growth inhibitory effects on HeLa cells altered by antioxidant modulators. Food Science and Biotechnology. 2007;16:1029–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Hong J, Kwon SJ, Sang S, Ju J, Zhou JN, Ho CT, Huang MT, Yang CS. Effects of garcinol and its derivatives on intestinal cell growth: Inhibitory effects and autoxidation-dependent growth-stimulatory effects. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2007;42:1211–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang MT, Smart RC, Wong CQ, Conney AH. Inhibitory effect of curcumin, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, and ferulic acid on tumor promotion in mouse skin by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. Cancer Research. 1988;48:5941–5946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JT, Ha J, Park IJ, Lee SK, Baik HW, Kim YM, Park OJ. Apoptotic effect of EGCG in HT-29 colon cancer cells via AMPK signal pathway. Cancer Letters. 2007;247:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang ZY, Woollard AC, Wolff SP. Hydrogen peroxide production during experimental protein glycation. FEBS Letters. 1990;268:69–71. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80974-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampa M, Alexaki VI, Notas G, Nifli AP, Nistikaki A, Hatzoglou A, Bakogeorgou E, Kouimtzoglou E, Blekas G, Boskou D, Gravanis A, Castanas E. Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of selective phenolic acids on T47D human breast cancer cells: potential mechanisms of action. Breast Cancer Research. 2004;6:R63–74. doi: 10.1186/bcr752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakaya S. Bioavailability of phenolic compounds. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2004;44:453–464. doi: 10.1080/10408690490886683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan HY, Zubair H, Ullah MF, Ahmad A, Hadi SM. A prooxidant mechanism for the anticancer and chemopreventive properties of plant polyphenols. Current Drug Targets. 2012;13:1738–1749. doi: 10.2174/138945012804545560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuzaki H, Hisamoto M, Hirose K, Akiyama K, Taniguchi H. Antioxidant properties of ferulic acid and its related compounds. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002;50:2161–2168. doi: 10.1021/jf011348w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Ng TB. Antioxidative and free radical scavenging activities of selected medicinal herbs. Life Sciences. 2000;66:725–735. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00643-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd RV, Hanna PM, Mason RP. The origin of the hydroxyl radical oxygen in the Fenton reaction. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1997;22:885–888. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(96)00432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal SM, Dias RO, Franco OL. Phenolic compounds in antimicrobial therapy. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2017;20:1031–1038. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2017.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcocci L, Maguire JJ, Droy-Lefaix MT, Packer L. The nitric oxide-scavenging properties of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1994;201:748–755. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mileo AM, Miccadei S. Polyphenols as modulator of oxidative stress in cancer disease: New therapeutic strategies. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2016;2016:6475624. doi: 10.1155/2016/6475624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortezaee K, Salehi E, Mirtavoos-Mahyari H, Motevaseli E, Najafi M, Farhood B, Rosengren RJ, Sahebkar A. Mechanisms of apoptosis modulation by curcumin: Implications for cancer therapy. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2019;234:12537–12550. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardini M, D'Aquino M, Tomassi G, Gentili V, Di Felice M, Scaccini C. Inhibition of human low-density lipoprotein oxidation by caffeic acid and other hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1995;19:541–552. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)00052-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osseni RA, Debbasch C, Christen MO, Rat P, Warnet JM. Tacrine-induced reactive oxygen species in a human liver cell Line: the role of anethole dithiolethione as a scavenger. Toxicology in Vitro. 1999;13:683–688. doi: 10.1016/S0887-2333(99)00050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron NR, Brumaghim JL. A review of the antioxidant mechanisms of polyphenol compounds related to iron binding. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2009;53(2):75–100. doi: 10.1007/s12013-009-9043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raish M, Ahmad A, Jardan YAB, Shahid M, Alkharfy KM, Ahad A, Ansari MA, Abdelrahman IA, Al-Jenoobi FI. Sinapic acid ameliorates cardiac dysfunction and cardiomyopathy by modulating NF-κB and Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathways in streptozocin induced diabetic rats. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 2021;145:112412. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M, Rice-Evans C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1999;26:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayyullathil F, Chathoth S, Hago A, Patel M, Galadari S. Rapid reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation induced by curcumin leads to caspase-dependent and -independent apoptosis in L929 cells. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2008;45:1403–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M, Rhodes CJ, Moncol J, Izakovic M, Mazur M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2006;160:1–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt T. Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Molecular Plant. 2010;1:2–20. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chen X, Huang Z, Chen D, Yu B, Yu J, Chen H, He J, Luo Y, Zheng P. Dietary ferulic acid supplementation improves antioxidant capacity and lipid metabolism in weaned piglets. Nutrients. 2020;12:3811. doi: 10.3390/nu12123811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenli YYZ, Zhen X, Hui J, Dapu W. The antioxidant properties of lycopene concentrate extracted from tomato paste. JAOCS, Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 2001;78:697–701. doi: 10.1007/s11746-001-0328-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yahfoufi N, Alsadi N, Jambi M, Matar C. The immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory role of polyphenols. Nutrients. 2018;10:1618. doi: 10.3390/nu10111618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Shi JJ, Wu FP, Li M, Zhang X, Li YP, Zhai S, Jia XL, Dang SS. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester up-regulates antioxidant levels in hepatic stellate cell line T6 via an Nrf2-mediated mitogen activated protein kinases pathway. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2017;23:1203–1214. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i7.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W, Wang SY. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in selected herbs. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2001;49:5165–5170. doi: 10.1021/jf010697n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B, Shang B, Li Y, Zhen Y. Inhibition of histone deacetylases by trans-cinnamic acid and its antitumor effect against colon cancer xenografts in athymic mice. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2016;13:4159–4166. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.