Abstract

A syringe‐like type III secretion system (T3SS) plays essential roles in the pathogenicity of Ralstonia solanacearum, which is a causal agent of bacterial wilt disease on many plant species worldwide. Here, we characterized functional roles of a CysB regulator (RSc2427) in R. solanacearum OE1‐1 that was demonstrated to be responsible for cysteine synthesis, expression of the T3SS genes, and pathogenicity of R. solanacearum. The cysB mutants were cysteine auxotrophs that failed to grow in minimal medium but grew slightly in host plants. Supplementary cysteine substantially restored the impaired growth of cysB mutants both in minimal medium and inside host plants. Genes of cysU and cysI regulons have been annotated to function for R. solanacearum cysteine synthesis; CysB positively regulated expression of these genes. Moreover, CysB positively regulated expression of the T3SS genes both in vitro and in planta through the PrhG to HrpB pathway, whilst impaired expression of the T3SS genes in cysB mutants was independent of growth deficiency under nutrient‐limited conditions. CysB was also demonstrated to be required for exopolysaccharide production and swimming motility, which contribute jointly to the host colonization and infection process of R. solanacearum. Thus, CysB was identified here as a novel regulator on the T3SS expression in R. solanacearum. These results provide novel insights into understanding of various biological functions of CysB regulators and complex regulatory networks on the T3SS in R. solanacearum.

Keywords: CysB regulator, pathogenesis, Ralstonia solanacearum, type III secretion system

Ralstonia solanacearum CysB controls cysteine synthesis and positively regulates the type III secretion system (T3SS) expression through the PrhG to HrpB pathway. The cysB mutant is cysteine auxotroph, while its impact on the T3SS is independent of growth deficiency.

1. INTRODUCTION

Ralstonia solanacearum is a causal agent of bacterial wilt disease on many plant species and is currently ranked as one of the 10 most destructive plant‐pathogenic bacteria as it causes severe losses in many economically important plants worldwide (Jiang et al., 2017; Mansfield et al., 2012). R. solanacearum is a soilborne gram‐negative vascular plant‐pathogenic bacterium that generally invades host plants through root wounds or natural root openings, and subsequently invades xylem vessels (Genin, 2010; Vasse et al., 1995). R. solanacearum proliferates extensively and produces copious amounts of exopolysaccharide (EPS) slime in xylem vessels, which blocks sap flow in xylem vessels, causes quick stunting and wilting of host plants, and is proposed as one of the most important pathogenicity factors in R. solanacearum (Janse et al., 2004; Milling et al., 2011). In addition to the EPS, phenotypes such as biofilm formation and swimming motility contribute jointly to colonization and infection processes of R. solanacearum toward host plants (Corral et al., 2020; Mori et al., 2016; Tans‐Kersten et al., 2001; Yao & Allen, 2007).

Like in many other gram‐negative pathogenic bacteria of animals and plants, a syringe‐like type III secretion system (T3SS) is a pathogenicity determinant of R. solanacearum toward host plants (Genin & Denny, 2012). Bacteria use the T3SS to inject virulence proteins (called type III effectors, T3Es) into the host cytosol to subvert host defence (Cunnac et al., 2004; Jones & Dangl, 2006). The R. solanacearum T3SS is encoded by 22 genes arranged in a hrp regulon that is responsible for the hypersensitive response and pathogenicity (Arlat et al., 1992; Coll & Valls, 2013). To date, the R. solanacearum T3SS has been characterized to be globally regulated by a complex network (Hikichi et al., 2017; Valls et al., 2006). However, the detailed regulatory mechanism of the T3SS remains to be fully addressed in R. solanacearum. In general, expression of the T3SS and T3E genes is directly controlled by HrpB, an AraC‐family of transcriptional regulator that binds to the hrp II motif in promoters of many target genes and directly controls expression of the T3SS and T3E genes (Cunnac et al., 2004; Mukaihara et al., 2010). Expression of hrpB is positively regulated by two close paralogs HrpG and PrhG, which are two‐component system (TCS) response regulators and can respond to host signals by phosphorylation (Plener et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2013). Host signals or some mimic signals are presumed to be recognized by the outer membrane protein PrhA and transferred to HrpG via a signalling cascade of PrhA‐PrhI/R‐PrhJ or some unknown cascades (Genin & Denny, 2012; Valls et al., 2006; Yoshimochi, Zhang, et al., 2009b). Moreover, the complex regulation network integrates numerous regulators such as PhcA, PrhN, PrhO, and PrhP, which regulate the T3SS expression indirectly (Genin & Denny, 2012; Hikichi et al., 2017; Valls et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2018, 2019). For instance, a global virulence regulator PhcA, which is quorum sensing‐dependent, binds to the promoter of prhI/R and represses its expression, which in turn shuts down hrpG expression, while PhcA positively regulates prhG expression (Genin et al., 2005; Yoshimochi et al., 2009a; Zhang et al., 2013). It results in a dual regulation of PhcA on the T3SS expression; R. solanacearum might switch from using HrpG to PrhG for hrpB activation in a cell density‐dependent manner (Zhang et al., 2013).

To further elucidate complex regulation of the T3SS in R. solanacearum, we previously screened several T3SS‐regulating candidates with transposon mutagenesis, in which a popA‐lacZYA fusion was used to monitor expression profiles of the T3SS in R. solanacearum strain OE1‐1, which is pathogenic on tomato and tobacco plants (Kanda et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2013). The popA gene exists as part of an operon with popB and popC, which are three T3Es, mapped to the left‐side of the hrp regulon and directly controlled by HrpB. The popA‐lacZYA fusion exhibits similar expression profiles as the T3SS under different conditions and its construction does not change the infection process of OE1‐1 toward host plants (Yoshimochi, Hikichi, et al., 2009a; Yoshimochi, Zhang, et al., 2009b; Zhang et al., 2011). RSc2427 was identified among the transposon mutants of interest. It is a protein of 313 amino acids in R. solanacearum GMI1000, https://iant.toulouse.inra.fr/bacteria/annotation/cgi/ralso.cgi; Salanoubat et al., 2002), which is annotated as a LysR‐family of CysB‐like transcriptional regulator. Accumulated evidence has demonstrated CysB to be a key regulator that positively regulates expression of many cys regulon genes functioning for thiosulfate and sulphate transportation, sulphate reduction, and eventually controlling cysteine synthesis in many bacteria (Albanesi et al., 2005; Farrow et al., 2015; Hicks & Mullholland, 2018; Kouzuma et al., 2008). Another CysB‐like regulator Cbl shares about 41% sequence identity and 60% similarity to Escherichia coli CysB. Cbl seems to act as an accessory element with CysB to regulate expression of cys regulon genes for cysteine synthesis. Cbl is specific for utilization of sulphur from organosulphur sources (Gyaneshwar et al., 2005; van der Ploeg et al., 1997, 1999). In E. coli, sulphate and sulphonates are assimilated by some ATP‐binding cassette (ABC) transporters, that is, SbpCysUWA proteins, subsequently reduced by CysNCDH/CysGIJ proteins to sulphite and then to sulphide (Kertesz, 2000). Expression of these cys regulon genes is regulated by Cbl and CysB proteins (Pereira et al., 2015; Stec et al., 2006). Assimilation and subsequent utilization of sulphate and sulphonates is highly conserved in different bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an opportunistic human pathogen causing severe, acute, and chronic nosocomial infections in immunocompromised patients, and Xanthomonas citri, a phytopathogenic bacterium causing canker disease on different species of citrus plants (Pereira et al., 2015; Song et al., 2019). In Pseudomonas putida, CysB binds to the promoter region of sfnECR operon genes to directly regulate their expression, which is activated under sulphate starvation conditions and plays important roles on sulphate starvation (Kouzuma et al., 2008). X. citri harbours three distinct ABC systems for alkanesulphonate and sulphonate transport, while it lacks a proper taurine transporter, which is different from those in E. coli and Burkholderia cenocepacia (Iwanicka‐Nowicka & Hryniewicz, 1995; Iwanicka‐Nowicka et al., 2007; Pereira et al., 2015), indicating that regulation of cys operon genes might be different among different bacteria. With genome searching, RSc1348 (a protein of 327 amino acids in GMI1000) was annotated as another CysB‐like regulator sharing 53% global identity to RSc2427 on amino acids. Our subsequent phylogenetic analysis in the present study suggested that RSc2427 showed higher sequence similarity to E. coli CysB than RSc1348, and RSc1348 showed higher sequence similarity to E. coli Cbl. These two CysB regulators were therefore designated as CysB (RSc2427) and Cbl (RSc1348), respectively. Expression of popA‐lacZYA was substantially reduced in the cysB transposon mutant, indicating that CysB might be a novel regulator on the T3SS expression in R. solanacearum. CysB was recently reported to be required for expression of the T3SS and contributed to pathogenicity mediated through a sensor kinase RetS in P. aeruginosa PAO1 (Song et al., 2019). Although putative ABC transporters have been predicted for cysteine synthesis in X. citri using bioinformatics, it remains to be elucidated whether CysB regulators control expression of the T3SS and contribute to pathogenicity in phytopathogenic bacteria such as R. solanacearum, and whether R. solanacearum harbours a RetS homolog sensor kinase to mediate regulation of CysB on the T3SS expression. We therefore focused on CysB and Cbl to investigate their functional roles in cysteine synthesis, regulation of the T3SS expression, and contribution to pathogenicity of R. solanacearum.

2. RESULTS

2.1. Phylogenetic analysis of R. solanacearum CysB and Cbl based on amino acid sequences

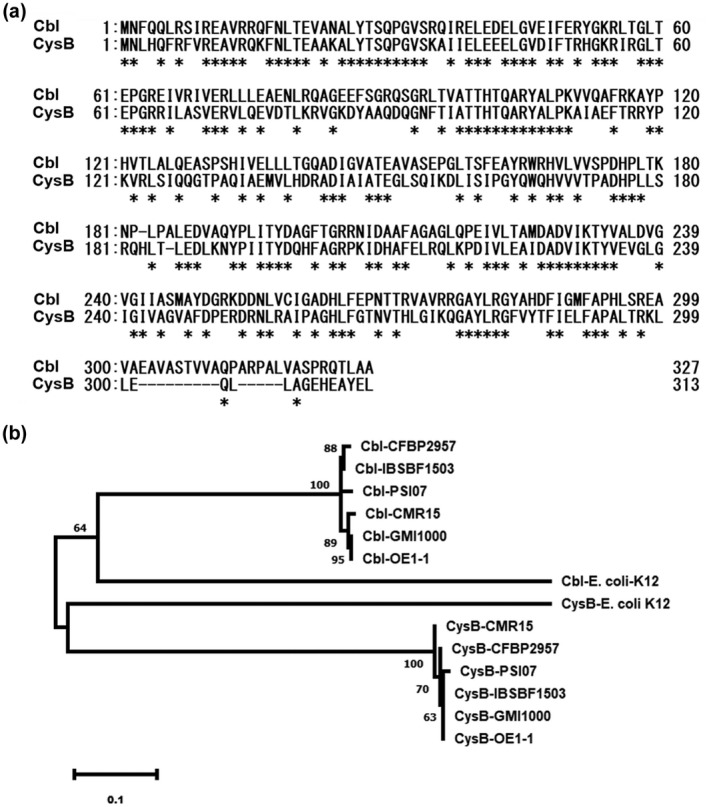

The R. solanacearum species complex (RSSC) is extremely heterogeneous and includes R. solanacearum and closely related species of Ralstonia syzygii, Ralstonia picketti, and the banana blood disease bacterium (Genin & Denny, 2012). Two CysB‐like regulators CysB and Cbl are annotated in the genome of GMI1000, a well‐studied strain of R. solanacearum (Salanoubat et al., 2002), which shares 53% global identity and 72% identity in the N‐terminal helix‐turn‐helix (HTH) domain based on amino acids (residues 1–60; Figure 1a). BLAST search analysis at the NCBI suggests that CysB and Cbl are highly conserved among different RSSC strains, exhibiting more than 90% identity of amino acids among different RSSC strains (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Alignment of amino acids of CysB (RSc2427 in Ralstonia solanacearum GMI1000) and Cbl (RSc1348 in GMI1000) from different R. solanacearum strains and Escherichia coli K12. (a) ClustalW alignment of CysB and Cbl from R. solanacearum OE1‐1. Asterisk indicates full conservation. (b) Phylogenetic analysis of amino acid sequences of CysB and Cbl of five R. solanacearum strains, representatives of five phylotypes, with CysB and Cbl of E. coli K12. GMI1000 and OE1‐1, phylotype I (ph‐I); CFBP2957, ph‐IIA; IBSBF1503, ph‐IIB; CMR15, ph‐III and PSI07, ph‐IV. Characters after the dash refer to CysB or Cbl from five R. solanacearum strains. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the neighbour‐joining method in MEGA 5

We further performed phylogenetic analysis of amino acid sequernces of CysB and Cbl in five R. solanacearum strains, representatives of five phylotypes (Genin & Denny, 2012), phylotype I (ph‐I), GMI1000 and OE1‐1; ph‐IIA, CFBP2957; ph‐IIB, IBSBF1503; ph‐III, CMR15 and ph‐IV, PSI07. We also compared them with CysB and Cbl of E. coli K12. Analysis of the phylogenetic relationship confirmed that CysB and Cbl are extremely conserved among different R. solanacearum strains, while they are clustered into two distinct groups. R. solanacearum RSc2427 clustered into one group with E. coli CysB, while RSc1348 clustered into the other group with E. coli Cbl (Figure 1b). These two CysB regulators are therefore designated as CysB (RSc2427) and Cbl (RSc1348). Because Cbl acts in association with CysB to regulate expression of cys genes for cysteine synthesis in many bacteria (Gyaneshwar et al., 2005), we hypothesized that CysB could display a master role similar to E. coli CysB regulators and be responsible for cysteine synthesis in R. solanacearum.

2.2. CysB, but not Cbl, is responsible for cysteine synthesis in R. solanacearum

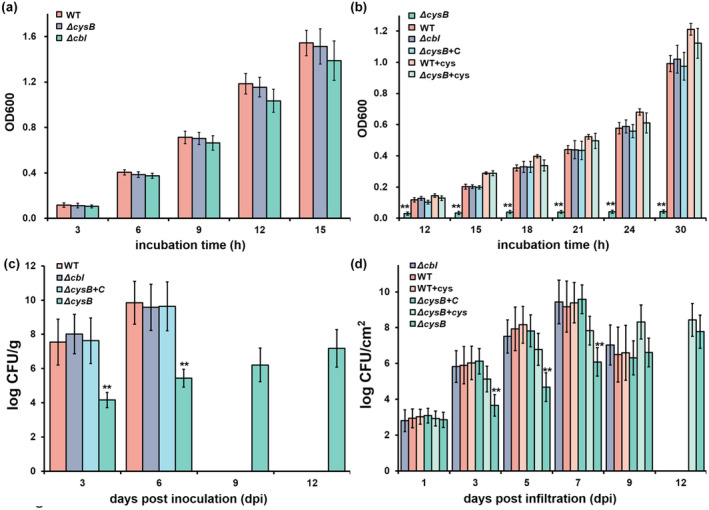

CysB regulators control cysteine synthesis in many bacteria (Hicks & Mullholland, 2018; Kouzuma et al., 2008). We first assessed whether CysB or Cbl is responsible for cysteine synthesis in R. solanacearum. We generated a cysB mutant (RQ5741) and a cbl mutant (RQ6198) from RK5050, and a popA‐lacZYA reporter strain from OE1‐1 and assessed their growth profiles in the nutrient‐rich (broth) medium and minimal medium (Hoagland medium with 2% sucrose, a hrp‐inducing medium; Yoshimochi et al., 2009b). The cysB mutants grew as well as the wild‐type strain, RK5050, in the nutrient‐rich (broth) medium (Figure 2a), but failed to grow in the minimal medium (Figure 2b). Complementation of cysB fully restored the diminished growth of cysB mutants in the minimal medium; supplementary cysteine at a final concentration of 20 mM also fully restored the diminished growth of cysB mutants in the minimal medium (Figure 2b). In contrast, cbl mutants exhibited similar growth profiles to RK5050 in both the nutrient‐rich (broth) medium and minimal medium (Figure 2a,b). These results confirm that CysB, but not Cbl, is responsible for cysteine synthesis in R. solanacearum.

FIGURE 2.

Involvement of CysB in growth of Ralstonia solanacearum OE1‐1 in (a) nutrient‐rich medium, (b) minimal medium, (c) tomato stems, and (d) tobacco leaves. RK5050 (OE1‐1, popA‐lacZYA), the wild‐type strain (WT); ΔcysB, RQ5741 (RK5050, ΔcysB); Δcbl, RQ6198 (RK5050, Δcbl); ΔcysB+C, RQC0703 (RQ5741 with complementation of cysB); +cys, cysteine supplemented into (a) minimal medium and (d) tobacco leaves. For the growth assay in media, a cell suspension (washed twice with distilled water) was adjusted to an OD600 of 1.0 and inoculated into fresh broth medium (nutrient‐rich medium) or minimal medium (Hoagland medium with 2% sucrose) with a proportion of 1%, and OD6 00 was measured periodically. For the growth assay in tomato stems, which is presented in log cfu/g, tomato plants were inoculated by the petiole‐inoculation method. Stem species were cut, weighed, and subjected to quantification of cell number by dilution plating. For the growth assay in tobacco leaves, which is presented in log cfu/cm2, a cell suspension at 104 cfu/ml was infiltrated into tobacco leaves and leaf disks (0.38 cm2) were punched for quantification of cell number by dilution plating. For cysteine supplementation, cysteine was added into the minimal medium or bacterial suspension at a final concentration of 20 mM for leaf infiltration into tobacco leaves. Each assay was repeated with three biological replicates, including three replicates per trial for the in vitro growth assay, and more than four biological replicates, including six plants per trial for the in planta growth assay. Mean values from all experiments were averaged and presented with SD (error bars). Statistical significance between cysB mutants and the WT strain was assessed using a post hoc Dunnett test following analysis of variance. **p < 0.01

2.3. CysB, but not Cbl, is important for the in planta proliferation of R. solanacearum

Plants produce abundant secondary metabolites and R. solanacearum can utilize some of the compounds as carbon sources for proliferation in xylem vessels (Lowe‐Power et al., 2018; Zuluaga et al., 2013). We assessed the proliferation of these two mutants inside host plants, including intercellular spaces of tobacco leaves and xylem vessels of tomato plants. For the growth assay in tomato stems, tomato plants were inoculated by the method of petiole‐inoculation, in which 2 μl of bacterial suspension at a density of 0.1 OD600 (108 cfu/ml) was dropped onto the fresh‐cut surface of petioles, and stem pieces were excised for quantification of cells densities. RK5050 proliferated extensively in tomato stems to about 106–107 cfu/g at 3 days postinoculation (dpi) and reached a maximum of about 1010 cfu/g at 6 dpi (Figure 2c). At this point, RK5050‐inoculated tomato plants wilted and died. The cysB mutant (RQ5741) grew slowly in tomato stems, and remained at about 103 to 104 cfu/g at 3 dpi, and reached a maximum of about 107–108 cfu/g at 12 dpi (Figure 2c). At this point, RQ5741‐infiltrated tomato plants stayed healthy. Complementation of cysB fully restored the impaired proliferation of the cysB mutant in tomato stems (Figure 2c). In contrast, cbl mutants exhibited similar growth profiles to RK5050 in tomato stems, which wilted tomato plants by about 6 dpi (Figure 2c).

For the growth assay in tobacco leaves, tobacco leaves were infiltrated with a bacterial suspension of 104 cfu/ml and cell densities in leaves were quantified by dilution plating every other day. RK5050 proliferated extensively in tobacco leaves, starting at approximately 103 cfu/cm2 at 1 dpi and reaching a maximum of approximately 109 cfu/ cm2 by 7 dpi, then decreasing dramatically to approximately 106 cfu/cm2 at 9 dpi (Figure 2d). At this point, RK5050‐infiltrated leaves became withered and died. The cysB mutant (RQ5741) proliferated slowly in tobacco leaves, reaching a maximum of approximately 108 cfu/cm2 at 12 dpi (Figure 2d). At this point, no wilting symptoms were observed on the RQ5741‐infiltrated tobacco leaves. Complementation of cysB fully restored the impaired proliferation of cysB mutants in tobacco leaves (Figure 2d). In contrast, the cbl mutant (RQ6196) exhibited similar proliferation to RK5050 in tobacco leaves (Figure 2d). All of these results indicate that CysB, but not Cbl, is important for R. solanacearum growth in host plants.

Supplementary cysteine fully restored the diminished growth of cysB mutants in the minimal medium (Figure 2b). We assessed whether the impaired in planta proliferation of cysB mutants was due to insufficient cysteine in plants. Cysteine was supplemented into a bacterial suspension (104 cfu/ml) at a concentration of 20 mM and the bacterial suspension was infiltrated into tobacco leaves for the growth assay. Supplementary cysteine did not change the proliferation of RK5050 in tobacco leaves, whereas proliferation of cysB mutants in cysteine‐supplemented tobacco leaves was substantially increased, reaching a maximum of approximately 108–109 cfu/cm2 at 9–12 dpi (Figure 2d). This was about one to two orders of magnitude higher than the control without cysteine supplementation, but about one to two orders of magnitude less than that of RK5050 in cysteine‐infiltrated tobacco leaves (Figure 2d). All of these results indicate that the impaired in planta proliferation of cysB mutants is partially due to insufficient cysteine inside host plants.

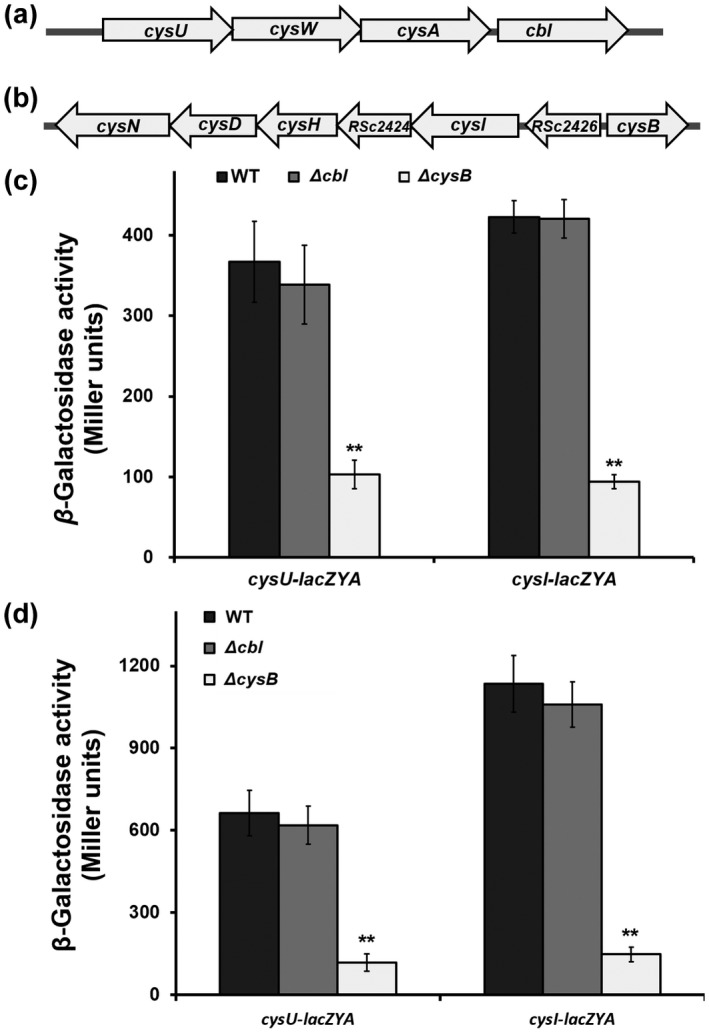

2.4. CysB positively regulates expression of cys genes for cysteine synthesis

In many bacteria, cysteine synthesis is controlled by multiple genes that form several cys regulons and function for the whole pathway of cysteine synthesis. Expression of cys genes is positively regulated by CysB regulators (Hicks & Mullholland, 2018). In GMI1000, the three genes of cysU (RSc1345), cysW (RSc1346), and cysA (RSc1347) are located together, possibly forming a cysU regulon to function for sulphate transportation (Figure 3a). A further five genes, cysI (RSc2425), RSc2424 (hypothetical protein), cysH (RSc2423), cysD (RSc2422), and cysN (RSc2422), are located together, possibly forming a cysI regulon to function for sulphate reduction (Figure 3b). The nucleotide sequences of cysU, cysI, and their upstream regions of about 500 bp (empirically harbouring their promoters) are identical in GMI1000 and OE1‐1 (data not shown). We fused promoterless lacZYA to the promoters of cysU and cysI to generate the reporter strains of cysU‐lacZYA and cysI‐lacZYA from OE1‐1 or its mutants to assess whether CysB or Cbl regulates expression of cysU and cysI. Expression of cysU‐lacZYA and cysI‐lacZYA was induced to higher levels in minimal medium than in rich medium, while the levels were substantially reduced in cysB deletion mutants in either rich or minimal medium (Figure 3c,d). Deletion of cbl did not change the expression of cysU‐lacZYA and cysI‐lacZYA in either rich or minimal medium (Figure 3c,d). All of these results indicate that CysB, but not Cbl, positively regulates expression of cys genes and therefore is responsible for cysteine synthesis in R. solanacearum.

FIGURE 3.

Regulation by CysB of expression of cys genes in Ralstonia solanacearum OE1‐1. (a, b), Schematic presentation of cysU and cysI operons. Promoterless lacZYA was fused to promoters of cysU and cysI at 54 bp after the start codon and reporter fusions were integrated into chromosomes of cysB or cbl mutants with the Tn7‐based chromosomal integration system. Enzyme activity is presented in Miller Units and the enzyme assay was carried out in nutrient‐rich medium (c) and minimal medium (d). Wild type (WT) refers to reporter strains of RQC721 (OE1‐1, cysU‐lacZYA) and RQC711 (OE1‐1, cysI‐lacZYA), ΔcysB and Δcbl refer to deletions of cysB or cbl from reporter strains of RQC721 and RQC711, respectively. Briefly, cells were grown in each medium to an OD600 of approximately 0.1 and subjected to the enzyme assay. Each assay was repeated with three biological replicates, including three replications per trial. Mean values of all experiments were averaged with SD. Statistical significance between cysB mutants and parental strain (WT) was assessed using a post hoc Dunnett test following analysis of variance. **p < 0.01

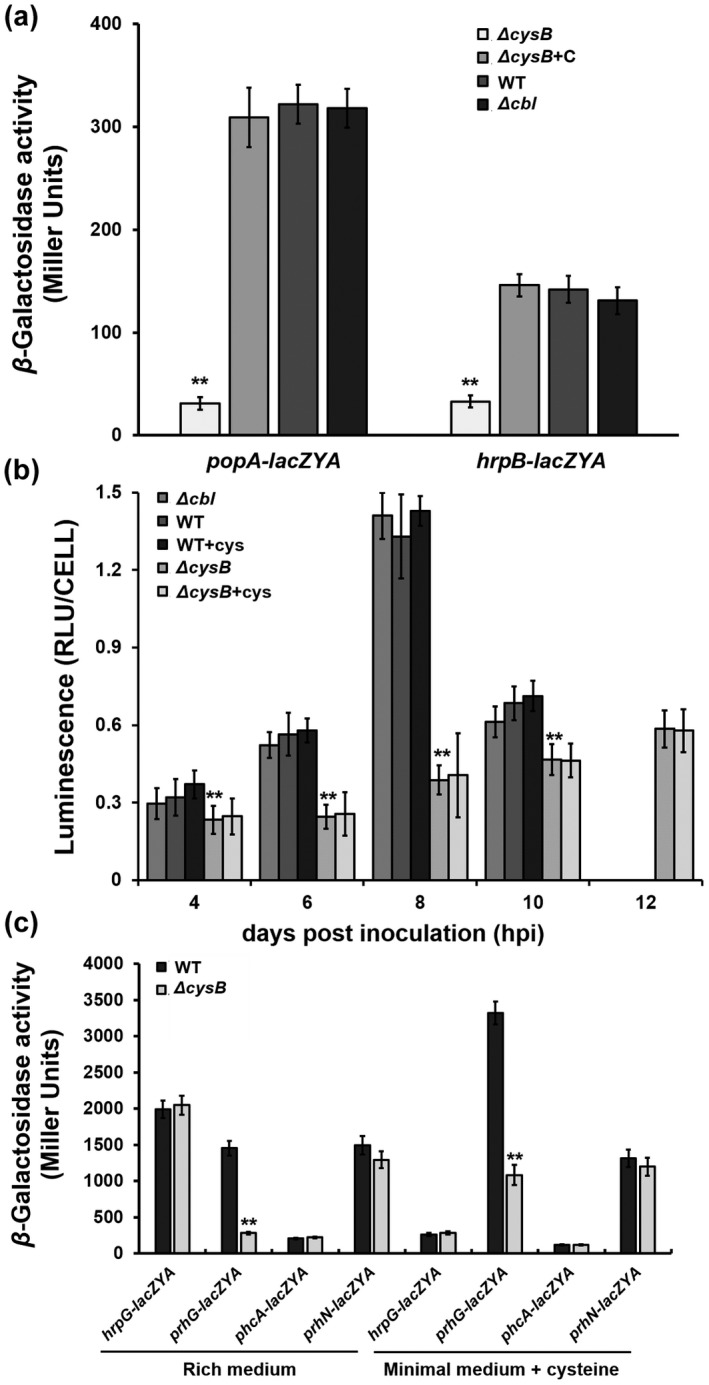

2.5. CysB is important for expression of the T3SS genes both in vitro and in planta via the PrhG‐HrpB pathway

CysB was originally identified as one of the T3SS‐regulating candidates in OE1‐1 by a transposon mutagenesis screen, in which expression profiles of the T3SS were monitored with a popA‐lacZYA fusion (Zhang et al., 2013). Expression of the T3SS is not activated in rich medium but is induced in the hrp‐inducing minimal medium ( Hoagland medium supplemented with 2% sucrose; Yoshimochi, Zhang, et al., 2009b). We assessed whether CysB or Cbl is required for popA expression in the hrp‐inducing medium. Because cysB mutants failed to grow in hrp‐inducing medium, cysteine was supplemented into this medium at a final concentration of 20 mM to support growth of cysB mutants. Supplementary cysteine did not alter popA expression of the wild‐type strain (RK5050) in the minimal medium, while cysB deletion substantially impaired popA expression in the cysteine‐supplemented minimal medium (Figure 4a). Complementation of cysB fully restored the impaired popA expression to that of RK5050 (Figure 4a). In contrast, cbl mutants exhibited similar expression levels of popA‐lacZYA as RK5050 (Figure 4a), confirming that CysB, but not Cbl, is a novel regulator of expression of the T3SS genes in the hrp‐inducing medium.

FIGURE 4.

Involvement of CysB in expression of type III secretion system (T3SS)‐regulating genes. (a) Expression of popA (the T3SS) and hrpB in cysteine‐supplemented hrp‐inducing medium (minimal medium), (b) expression of popA in tobacco leaves, and (c) expression of T3SS‐regulating genes, hrpG‐lacZYA, prhG‐lacZYA, phcA‐lacZYA, and prhN‐lacZYA in rich medium and the cysteine‐supplemented minimal medium. Wild type (WT) refers to each reporter strains of RK5050 (popA‐lacZYA), RK5046 (hrpB‐lacZYA), RK5120 (hrpG‐lacZAY), RK5212 (prhG‐lacZAY), RK5619 (prhN‐lacZAY), and RK5043 (phcA‐lacZAY). ΔcysB and Δcbl refer to deletion of cysB or cbl from each reporter strain. ΔcysB+C refers to RQC0730 (RQ5741 with complementation of cysB). +cys refers to cysteine supplementation in the minimal medium or tobacco leaves. For the in vitro enzyme assay, strains were grown in each medium to an OD600 of about 0.1 and subjected to the enzyme assay, enzymatic activities of which are presented in Miller Units. For the in planta enzyme assay, tobacco leaves were infiltrated with bacterial suspension or the cysteine‐supplemented bacterial suspension at OD600 of 0.1, and leaf disks were punched for the enzyme assay with the Galacto‐Light Plus kit, enzymatic activities of which are presented as RLU/cell (luminescence normalized by cell number). Luminescence was determined using the GloMax20 luminometer (Promega) and cell number was quantified by dilution plating. Each assay was repeated with three biological replicates, including three replicates per trial for the in vitro enzyme assay, and more than four biological replicates, including six plants per trial for the in planta enzyme assay. Mean values of all experiments were averaged with SD. Statistical significance between the WT and mutants was assessed using a post hoc Dunnett test following analysis of variance. **p < 0.01

We further assessed whether CysB is required for popA expression in host plants because the T3SS expression can be enhanced to high levels in host plants or by being in contact with host signals (Valls et al., 2006; Yoshimochi, Zhang, et al., 2009b). A bacterial suspension at 0.1 OD600 was infiltrated into tobacco leaves and bacterial cells were recovered for the in planta enzyme assay. We previously reported that R. solanacearum does not start substantial proliferation in tobacco leaves until about 10 h postinfiltration (hpi) (Zhang et al., 2019). The enzyme assay in tobacco leaves was therefore carried out at 4–10 hpi. Consistent with the above results in the hrp‐inducing medium, popA expression in tobacco leaves was significantly impaired with deletion of csyB, but not cbl (Figure 4b). The cysteine‐supplemented bacterial suspension (0.1 OD600, 20 mM cysteine) was also infiltrated into tobacco leaves for the in planta enzyme assay. Supplementary cysteine did not change popA expression of RK5050 in tobacco leaves, while cysB mutants exhibited significantly impaired popA expression compared to RK5050 in the cysteine‐supplemented tobacco leaves (Figure 4b), confirming that CysB is a novel regulator of expression of the T3SS both in vitro and in planta, and the impaired T3SS expression in cysB mutants is independent of growth deficiency or insufficient cysteine inside host plants.

In R. solanacearum, the T3SS is directly controlled by a master regulator, HrpB, and two close paralogs of HrpG and PrhG positively regulate expression of hrpB (Plener et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2013). Moreover, some regulators, such as PrhJ, PhcA, and PrhN, regulate expression of hrpG and prhG (Valls et al., 2006; Yoshimochi, Hikichi, et al., 2009a; Zhang et al., 2015). We evaluated whether CysB was involved in expression of these T3SS‐regulating genes. Deletion of cysB substantially impaired expression of hrpB and prhG in the cysteine‐supplemented minimal medium (Figure 4a,c). Moreover, deletion of cysB substantially impaired prhG expression in nutrient‐rich medium, in which cysB mutants grew normally (Figure 4c). In contrast, cysB mutants expressed hrpG, phcA, and prhN normally in both the rich and minimal media (Figure 4c), indicating that regulation by CysB of expression the T3SS genes is mediated through the PrhG‐HrpB pathway, but through some unknown pathway to PrhG.

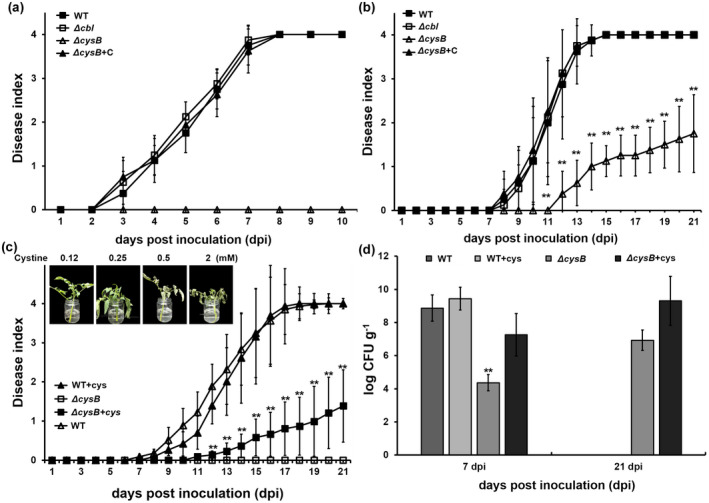

2.6. CysB is essential for pathogenicity of R. solanacearum

Both the in planta proliferation and the T3SS are essential for R. solanacearum to wilt host plants (Genin & Denny, 2012). We evaluated the contribution of CysB and Cbl to the pathogenicity of R. solanacearum. Tomato and tobacco plants were subjected to the virulence assay with petiole‐inoculation inoculation methods, which enables direct invasion into xylems vessels, and leaf‐infiltration, which enables direct invasion into intercellular spaces of leaves. The cysB mutants failed to wilt tomato plants but remained weakly virulent on tobacco plants; complementation of cysB fully restored the impaired virulence of cysB mutants to that of RK5050 on the tomato and tobacco plants (Figure 5a,b). In contrast, cbl mutants exhibited similar virulence to RK5050 on the two host plants (Figure 5a,b), confirming that CysB, but not Cbl, is important for pathogenicity of R. solanacearum toward different host plants.

FIGURE 5.

Virulence assay of cysB mutants on (a) tomato plants by the method of petiole inoculation, (b) tobacco plants by the method of leaf infiltration, and (c) tomato cutting seedlings. Pictures in (c) refer to preparation of tomato cutting seedlings in one‐quarter diluted minimal medium with supplementary cysteine. Addition of cysteine at 0.25 mM or higher was extremely pernicious, and withered and dried tomato cutting seedlings quickly, while that at 0.125 mM was competent for growth of tomato cutting seedlings. (d) Growth of cysB mutants in stems of tomato cutting seedlings. WT, RK5050 (OE1‐1, popA‐lacZYA); ΔcysB, RQ5741 (RK5050, ΔcysB); Δcbl, RQ6198 (RK5050, Δcbl); ΔcysB+C, RQC0730 (RQ5741 with complementation of cysB); +cys, supplementation with cysteine. For the petiole‐inoculation, 2 µl of bacterial suspension at 108 cfu/ml was dropped onto the freshly cut surface of tomato petioles. For leaf infiltration, about 50 µl of bacterial suspension at 108 cfu/ml was infiltrated into tobacco leaves with a blunt‐end syringe. For cysteine restoration, cysteine was added into one‐quarter diluted minimal medium at 0.1 mM and tomato cutting seedlings were soaked for 2 days and then inoculated by petiole‐inoculation. Wilt symptoms were inspected daily and scored on a disease index scale from 0 to 4 (0, no wilting; 1, 1%–25% wilting; 2, 26%–50% wilting; 3, 51%–75% wilting; 4, 76%–100% wilted or dead). Mean values of all experiments were averaged with SD (error bars). Growth in stems of tomato cutting seedlings is presented in log cfu/g. Cells were harvested from tomato stem pieces and quantified with dilution plating. Each assay was repeated with more than four biological replicates, including 12 plants per trial. Mean values of all experiments were averaged and presented with SD (error bars). Statistical significance between cysB mutant and the wild‐type strain (WT) was assessed using a post hoc Dunnett test following analysis of variance. **p < 0.01

The in planta proliferation of cysB mutants was substantially impaired, which was partially due to insufficient cysteine in host plants (Figure 3b). We thus assessed whether the diminished pathogenicity of cysB mutants on tomato plants was due to insufficient cysteine in tomato plants. Cysteine‐irrigated tomato plants were primarily subjected to cysteine restoration, while no restoration of virulence or in planta proliferation was observed in cysB mutants, which might be due to insufficient cysteine inside tomato plants (data not shown). We thus changed to prepare tomato cuttings by soaking them in one‐quarter diluted minimal medium supplemented with cysteine, which might enable tomato plants to accumulate more cysteine inside stems. Supplementary cysteine in the diluted medium at 0.25 mM or higher was extremely pernicious, and withered and dried tomato cuttings within 1–2 days, while that at 0.125 mM was competent for growth of tomato cuttings (Figure 5c). After treatment with supplementary cysteine (0.1 mM) for 2 days, tomato cuttings were subjected to inoculation by the petiole‐inoculation method. RK5050 wilted tomato cuttings by about 7 dpi and eventually killed all tomato cuttings by 17 dpi (Figure 5c). Supplementary cysteine did not change the infection process of RK5050 toward tomato cuttings (Figure 5c). In stems of tomato cuttings, RK5050 proliferated to a maximum of about 109–1010 cfu/g at 7 dpi and supplementary cysteine did not change its proliferation in tomato stems (Figure 5d). The cysB mutants began to wilt tomato cuttings at about 11 dpi and eventually killed about 20% of test tomato cuttings by 21 dpi (Figure 5c). Supplementary cysteine in the diluted medium substantially resorted proliferation of cysB mutants in stems of tomato cuttings to about 106–108 cfu/g at 7 dpi, which was two to four orders of magnitude higher than the control without cysteine supplementation, but was about one to two orders of magnitude less than that of the wild‐type strain in the cysteine‐treated tomato stems (Figure 5d). The cysB mutants eventually proliferated to about 109–1010 cfu/g1 in the cysteine‐treated tomato stems by 21 dpi (Figure 5d). This was about three orders of magnitude higher than that without cysteine supplementation, but was equal to the maximum densities of the wild‐type strain in the cysteine‐treated tomato stems, about 7 dpi (Figure 5d). All of these results indicate that insufficient cysteine inside host plants partially resulted in impaired pathogenicity of cysB mutants, but is not a key determinant of the diminished pathogenicity of cysB mutants toward tomato plants.

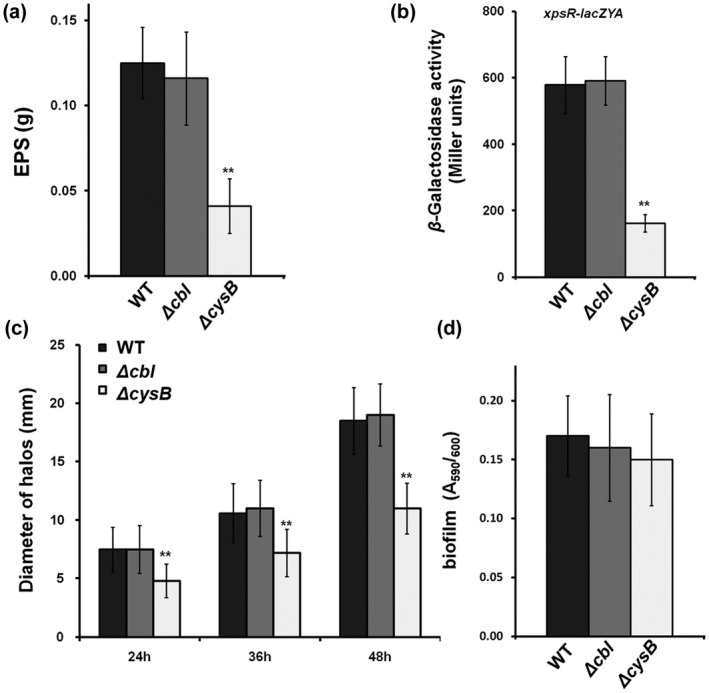

2.7. CysB is required for swimming motility and EPS production in R. solanacearum

In addition to the T3SS, the EPS production, swimming motility, and biofilm formation contribute jointly to the infection process of R. solanacearum (Mori et al., 2016; Tans‐Kersten et al., 2001). Expression of genes for EPS production is positively regulated by a transcription regulator, XpsR (Huang & Schell, 1995; Huang et al., 1998). We previously generated an xpsR‐lacZAY reporter fusion to monitor the expression level of xpsR and EPS production (Zhang et al., 2019). Expression of xpsR was significantly decreased in CysB mutants (Figure 6b). This was consistent with EPS quantification, which was performed with ethanol‐based precipitation, and was significantly decreased by cysB deletion (Figure 6a). The swimming motility was determined as swimming halos on semisolid agar plates; those produced by cysB mutants were significantly smaller than those produced by RK5050 (Figure 6c). Biofilm formation was assessed in polystyrene tubes; cysB mutants exhibited similar biofilm formation to RK5050 (Figure 6d). In contrast, deletion of cbl did not change EPS production, biofilm formation, or swimming motility in R. solanacearum (Figure 6a–d). All of these results confirmed that CysB is required for EPS production and swimming motility in R. solanacearum.

FIGURE 6.

Involvement of CysB in extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) production (a, b), swimming motility (c), and biofilm formation (d). The wild type (WT) in (a, c, d) refers to RK5050 (OE1‐1, popA‐lacZYA) and that in (b) refers to RK5138 (OE1‐1, xpsR‐lacZYA). ΔcysB and Δcbl refer to deleted cysB or cbl from each parental strain. Briefly, EPS was quantified with ethanol‐based precipitation. XpsR directly regulates EPS production; the reporter fusion ofxpsR‐lacZAY was used to monitor EPS production levels as assessed by an in vitro enzyme assay. Swimming motility was assessed on semisolid plates with 0.3% agar, and the diameters of swimming halos on semisolid medium were measured after 24, 36, and 48 h. Biofilm formation was assessed in polystyrene tubes, which was quantified with absorbance at 530 nm (A530) and normalized with OD600. Each assay was repeated with three biological replicates, including four replications per trial. Mean values of all experiments were averaged with SD. Statistical significance between cysB mutants and the WT strain was assessed using a post hoc Dunnett test following analysis of variance. **p < 0.01

3. DISCUSSION

In R. solanacearum, the T3SS is a key pathogenicity determinant. However, the regulatory mechanisms of the T3SS have not been yet fully addressed. We previously screened a subset of candidates that regulate expression of the T3SS with transposon mutagenesis and found that multiple regulators centralize to the master regulator HrpB, and in turn regulate expression of the T3SS through a complex regulatory network (Zhang et al., 2018, 2019). In the present study, we provided multiple lines of evidence to demonstrate that CysB positively regulates expression of the T3SS and is essential for virulence of R. solanacearum. We experimentally confirmed that CysB is responsible for cysteine synthesis in R. solanacearum. The cysB mutants were cysteine auxotrophs that failed to grow in minimal medium, and that supplementary cysteine fully restored the diminished growth. Moreover, CysB positively regulated expression of cysU and cysI, which are proposed to function in the sulphate and thiosulphate transportation, and sulphate reduction, respectively, and are essential for cysteine synthesis in R. solanacearum. This is consistent with the fact that CysB‐like regulators usually function as transcriptional activators of cys genes for sulphate assimilation, sulphate‐thiosulphate transportation, sulphate reduction, and cysteine synthesis (Hicks & Mullholland, 2018; Kouzuma et al., 2008). CysB binds to the promoter region of some cys operon genes and directly regulates their expression (Kertesz, 2000; Kouzuma et al., 2008). X. citri harbours three distinct ABC systems for alkanesulphonate and sulphonate transport, while it lacks a proper taurine transporter, which is different from those in E. coli and B. cenocepacia (Iwanicka‐Nowicka et al., 2007; Pereira et al., 2015), indicating that regulation of cys operon genes might be different among different bacteria. It remains to be further elucidated how R. solanacearum CysB regulates expression of cys operon genes.

Deletion of cysB resulted in substantially impaired expression of hrpB and the T3SS genes both in the hrp‐inducing medium and inside host plants. This is consistent with the fact that the master regulator HrpB directly controls transcriptional expression of genes of the T3SS and many T3Es (Cunnac et al., 2004; Mukaihara et al., 2010; Valls et al., 2006). Expression levels of the T3SS genes were substantially impaired with cysB deletion in the minimal medium, even in the presence of supplementary cysteine, which supported growth of cysB mutant in the minimal medium, confirming that impaired expression of the T3SS in cysB mutants was independent of growth deficiency under nutrient‐limited conditions. The impaired T3SS expression caused by cysB deletion was also confirmed inside host plants. Supplementary cysteine substantially restored the impaired in planta proliferation of cysB mutants, while no restoration was observed to the impaired expression of the T3SS genes inside host plants. It confirms that regulation of CysB on expression of the T3SS is independent of growth deficiency under nutrient‐limited conditions. Expression of hrpB is positively regulated by two close paralogs, HrpG and PrhG, in a parallel way (Plener et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2013). Deletion of cysB significantly impaired prhG expression in both nutrient‐rich and cysteine‐supplemented minimal media, in which R. solanacearum grew normally. In contrast, expression of hrpG was not changed by deletion of cysB, indicating that regulation of CysB on the T3SS expression is mediated through the pathway of PrhG to HrpB. The prhG expression was positively regulated by PhcA and PrhN (Zhang et al., 2013, 2015), while cysB deletion did not change the expression of phcA and prhN, indicating that CysB possibly regulates prhG expression through some novel pathway. It was recently reported that CysB regulates the T3SS expression indirectly through a sensor kinase RetS in P. aeruginosa PAO1 (Song et al., 2019). With the NCBI BLAST search, only RSc3079 (a protein of 994 amino acids in GMI1000) was identified as a homolog of RetS in P. aeruginosa (a protein of 942 amino acids in PAO1), which is a putative TCS sensor kinase and shares 31% global identity with RetS based on amino acids (data not shown). We previously generated some TCS mutants lacking TCS sensor kinases, including RK6003 (RK5050, ΔRSc3079); no change in expression levels of the T3SS (popA‐lacZYA) was detected in this RSc3079 mutant (unpublished data), indicating that RSc3079 might be not a target for CysB to exhibit its regulation on expression of the T3SS genes in R. solanacearum. Further experiments are planned to identify direct targets of CysB using ChIP‐sequencing and to ascertain how CysB regulates expression of prhG and the T3SS in R. solanacearum.

Plants synthesize abundant secondary metabolites and nutrients in xylem vessels are more abundant than that in the minimal medium, which uses sucrose as the sole carbon source (Yoshimochi et al., 2009b). R. solanacearum could utilize some compounds as carbon sources to fulfil growth in host xylem vessels (Lowe‐Power et al., 2018). The cysB mutants were cysteine auxotrophs that failed to grow in the minimal medium, while they can utilize some plant‐synthesized secondary metabolites and hence grow slowly in host plants. Proliferation of cysB mutants in the cysteine‐supplemented tomato cuttings was substantially restored and was equal to the maximum density of the wild‐type strain even though it was much slower than the wild‐type strain. In consideration of full restoration by supplementary cysteine on growth of cysB mutants in the minimal medium, impaired proliferation of cysB mutants in the cysteine‐supplemented tomato cuttings might not be a key determinant of impaired pathogenicity of CysB mutants toward host tomato plants. It might be partially due to impaired expression of the T3SS in host plants because some hrp mutants exhibit substantially impaired in planta proliferation (Genin & Denny, 2012; Zhang et al., 2018). Extensive proliferation in host plants is one of the most important pathogenicity determinants of R. solanacearum (Denny, 1995; Roberts et al., 1988). It was not unexpected that cysB mutants failed to wilt tomato plants. On the contrary, cysB mutants remained slightly virulent on tobacco plants, which was not a special case because different plants display different symptoms, depending on infecting strains (Lin et al., 2008). We previously reported that a R. solanacearum prhK mutant completely lost virulence toward tomato plants but was slightly virulent on tobacco plants (Zhang et al., 2011). In addition to the T3SS, EPS production, swimming motility, and biofilm formation contribute jointly to the colonization and infection process of R. solanacearum toward host plants (Mori et al., 2016; Tans‐Kersten et al., 2001). EPS production and swimming motility were significantly impaired in cysB mutants, indicating that CysB functions on several infection behaviours and hence plays essential roles in pathogenicity in R. solanacearum.

It is intriguing that only CysB was confirmed to be responsible for cysteine synthesis, expression of T3SS genes, and pathogenicity of R. solanacearum, even though CysB and Cbl exhibit 53% global identity and 72% partial identity in the N‐terminal HTH domain on amino acids. Like many other LTTR members, CysB is composed of two functional domains joined by a linker helix involved in oligomerization: an N‐terminal HTH domain, which is responsible for the DNA‐binding specificity, and a C‐terminal substrate‐binding domain, which is structurally homologous to the type 2 periplasmic binding proteins (Lochowska et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2020). Regulation of transcription of genes in response to a sulphur source is attributed to two transcriptional regulators of CysB and Cbl, which are homologous and function together for utilization of taurine as sulphur source for growth in E. coli (Gyaneshwar et al., 2005; Javaux et al., 2007; van der Ploeg et al., 1997, 1999, 2001). The periplasmic binding proteins are responsible for uptake of a variety of substrates such as phosphate, sulphate, polysaccharides, lysine, arginine, ornithine, and histidine (Lu et al., 2020; Maddocks & Oyston, 2008; van der Ploeg et al., 1999, 2001). Two CysB regulators, CysB and Cbl, are annotated in R. solanacearum and analysis of the phylogenetic relationship suggests that R. solanacearum CysB is more homologous to E. coli CysB regulator than Cbl. In consideration of the relatively low similarity between the C‐terminal domains of CysB and Cbl, the functional difference between these two CysB‐like regulators might be due to structural differences of the C‐terminal substrate‐binding domains.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that CysB is a novel CysB regulator that positively regulates expression of cys genes and is responsible for cysteine synthesis in R. solanacearum. In addition to the regulation of cysteine synthesis, CysB functions on multiple infection behaviours, including T3SS expression, in planta proliferation, EPS production, and swimming motility. CysB plays essential roles in the pathogenicity of R. solanacearum toward different host plants. All of these results provide novel insight into understanding various biological functions of CysB regulators and the complex regulation of the T3SS in R. solanacearum.

4. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

4.1. Bacterial strains and growth conditions

R. solanacearum strains used in this study were derivatives of R. solanacearum OE1‐1 (Table 1). OE 1‐1 is a R. solanacearum strain that is virulent on tomato and tobacco plants (Kanda et al., 2003). R. solanacearum strains were grown at 28°C in nutrient‐rich medium and a minimal medium (Hoagland medium with 2% of sucrose, a hrp‐inducing medium) (Yoshimochi, Hikichi, et al., 2009a; Yoshimochi, Zhang, et al., 2009b). E. coli DH12S and S17‐1 were grown at 37°C in Luria‐Bertani (LB) medium, and used for plasmid construction and conjugational transfer, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Relative characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|

| OE1‐1 | Wild‐type, race 1, biovar 3 | Kanda et al. (2003) |

| RK5043 | OE1‐1, phcA‐lacZYA | Yoshimochi, Zhang, et al. (2009b) |

| RK5046 | OE1‐1, hrpB‐lacZYA | Yoshimochi, Zhang, et al. (2009b) |

| RK5050 | OE1‐1, popA‐lacZYA | Yoshimochi, Zhang, et al. (2009b) |

| RK5120 | OE1‐1, hrpG‐lacZYA | Yoshimochi, Zhang, et al. (2009b) |

| RK5124 | OE1‐1, prhJ‐lacZYA | Yoshimochi, Zhang, et al. (2009b) |

| RK5212 | OE1‐1, prhG‐lacZYA | Zhang et al. (2013) |

| RK5619 | OE1‐1, prhN‐lacZYA | Zhang et al. (2015) |

| RK5138 | OE1‐1, xpsR‐lacZYA | Yoshimochi, Zhang, et al. (2009b) |

| RQ6198 | popA‐lacZYA, Δcbl | This study |

| RQ5741 | popA‐lacZYA, ΔcysB | This study |

| RQ5753 | hrpB‐lacZYA, ΔcysB | This study |

| RQ6016 | hrpG‐lacZYA, ΔcysB | This study |

| RQ6019 | prhG‐lacZYA, ΔcysB | This study |

| RQ6093 | prhJ‐lacZYA, ΔcysB | This study |

| RQ6096 | prhN‐lacZYA, ΔcysB | This study |

| RQ6119 | phcA‐lacZYA, ΔcysB | This study |

| RQC703 | RK5050, ΔcysB2+ cysB2 | This study |

| RQ6196 | OE1‐1, Δcbl | This study |

| RQ6193 | OE1‐1, ΔcysB2 | This study |

| RQC721 | OE1‐1, cysU‐lacZYA | This study |

| RQC711 | OE1‐1, cysI‐lacZYA | This study |

| RQC725 | OE1‐1, ΔcysB1, cysU‐lacZYA | This study |

| RQC723 | OE1‐1, ΔcysB2, cysU‐lacZYA | This study |

| RQC729 | OE1‐1, ΔcysB1, cysI‐lacZYA | This study |

| RQC727 | OE1‐1, ΔcysB2, cysI‐lacZYA | This study |

4.2. Mutant generation with in‐frame deletion of cysB and cbl

Mutants with in‐frame deletion of target genes were generated with the pK18mobsacB‐based homologous recombination as described previously (Zhang et al., 2015). In brief, two DNA fragments flanking target genes were conjugated with joint PCR and subcloned into pK18mobsacB. After validating sequences, the plasmid was transferred into R. solanacearum strains by conjugation with E. coli S17‐1. Mutants with in‐frame deletion of target genes were generated (Table 1) and confirmed by colony PCR with respective primer pairs (Table S1).

4.3. Complementation assay

In the present study, the genetic complementation was performed with the Tn7‐based site‐specific chromosomal integration system as described previously (Zhang et al., 2011, 2021). In brief, a DNA fragment containing the coding sequence and native promoter (upstream region of about 500 bp, empirically harbouring the native promoter) was PCR amplified and cloned into pUC18‐mini‐Tn7T‐Gm (Choi et al., 2005). After validating the sequence, the target DNA fragment was integrated into a chromosome of the corresponding mutants at 25 bp of glmS downstream with the Tn7‐based site‐specific chromosomal integration system as the monocopy (Zhang et al., 2021). Complementary strains were confirmed by colony PCR with a primer pair of glmsdown and Tn7R (Zhang et al., 2011).

4.4. Construction of lacZYA‐fused reporter strains for the promoter activity assay

Strains with reporter fusions of cysU‐laZYA and cysI‐lacZYA were generated with the above Tn7‐based chromosomal integration system (Zhang et al., 2015). In brief, promoterless lacZYA was fused to cysU and cysI at 54 bp after the start codon, in which 6 bp of nucleotide acids were mutated into KpnI for insertion of lacZYA. A DNA fragment containing the whole promoter region was first cloned into pUC18‐mini‐Tn7T‐Gm and promoterless lacZYA was subsequently inserted. After validating the sequence, fusions of cysU‐laZYA and cysI‐lacZYA were integrated into R. solanacearum chromosomes to generate reporter strains, which were confirmed by colony PCR with a primer pair of glmsdown and Tn7R (Zhang et al., 2011).

4.5. Bacterial growth assay

Bacterial growth assay was performed both in medium and in planta (tobacco leaves and tomato stems). Growth in medium was assessed with optical density at 600 nm (OD600). The in planta growth was represented in log10 cfu/cm2 in tobacco leaves and log10 cfu/g in tomato stems, which was quantified by the dilution plating. For growth restoration, cysteine, purchased from Sango Biotech, was supplemented into the minimal medium at a final concentration of 20 mM for the in vitro growth restoration assay, or supplemented into a bacterial suspension at a final concentration of 20 mM for the leaf infiltration, and then for growth restoration assay in tobacco leaves. Tomato cutting seedlings were soaked into one‐quarter diluted minimal medium supplemented with 0.1 mM cysteine and subjected to the growth restoration assay in tomato stems. Each assay was performed with three biological replicates, including three replicates per trial for the in vitro growth assay and more than four biological replicates, including six plants per trial for the in planta growth assay. Mean values of all experiments were averaged with SD and statistical significance was assessed using a post hoc Dunnett test following analysis of variance (ANOVA).

4.6. β‐galactosidase assay

Expression of genes, which were fused with promoterless lacZYA, was assessed with the β‐galactosidase assay as described previously (Zhang et al., 2013). Enzyme activities in medium (in vitro) were expressed in Miller Units (Miller, 1992), and those in tobacco leaves were expressed in RLU/cell, luminescence divided by cell number (Zhang et al., 2013). The enzyme assay was carried out with three biological replicates, including three replicates per trial for the in vitro enzyme assay, and more than four biological replicates, including six plants per trial for the in planta enzyme assay. Mean values of all experiments were averaged with SD and statistical significance was assessed using a post hoc Dunnett test following ANOVA.

4.7. Virulence assay

The virulence assay was carried out on wilt‐susceptible tomato plants (cv. Ailsa Craig) and tobacco plants (Nicotiana tabacum ‘Bright Yellow’). Plants were grown at 25°C for about 3–4 weeks and subjected to the virulence test. Tomato plants were inoculated by the petiole‐inoculation method, which enables direct invasion into xylem vessels, and tobacco plants were inoculated by the method of leaf infiltration, which enables direct invasion into intercellular spaces of leaves (Zhang et al., 2013). For assay with cysteine restoration, tomato plants were prepared with cutting seedlings, which were soaked in one‐quarter diluted minimal medium or supplemented with 0.2 mM cysteine, and inoculated by petiole‐inoculation. Each assay was carried out with four biological replicates, including 12 plants per trial. Wilt symptoms of plants were assessed using a 1–4 disease index and mean values of all experiments were averaged. The statistical significance was assessed using a post hoc Dunnett test following ANOVA.

4.8. EPS quantification, biofilm formation, and swimming motility assay

The EPS quantification was performed as described previously (Shen et al., 2020). In brief, R. solanacearum was cultured in sucrose‐peptone medium to an OD600 of about 3.0. Supernatant of a 100‐ml aliquot of culture was mixed with four volumes of ethanol and kept at 4°C overnight. Precipitated EPS was collected by centrifugation, dried overnight at 55°C, and weighed.

Biofilm formation was assessed in polystyrene tubes as described previously (Mori et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2019). In brief, the bacteria were incubated at 28°C for 48 h without shaking. After staining with crystal violet, the biofilm was washed twice and quantified by measuring absorbance at 590 nm (A590) and normalized by cell number (OD600).

The swimming motility assay was carried out on semisolid plates with 0.3% agar as described previously (Kelman & Hruschka, 1973). The diameters of the swimming halos on semisolid agar plates (28°C for 24–48 h) were measured. Each assay was repeated with three biological replicates, including four replications per trial. The mean values of all experiments were averaged with SD and statistical significance was assessed using a post hoc Dunnett test following ANOVA.

Supporting information

TABLE S1. Primers used in this study

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We express our thanks for funding support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32170180) and the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (cstc2021jcyj‐msxmX0254) to Y. Z.

Chen, M. , Zhang, W. , Han, L. , Ru, X. , Cao, Y. , Hikichi, Y. et al. (2022) A CysB regulator positively regulates cysteine synthesis, expression of type III secretion system genes and pathogenicity in Ralstonia solanacearum . Molecular Plant Pathology, 23, 679–692. 10.1111/mpp.13189

Min Chen, Weiqi Zhang, and Liangliang Han contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Guanghui Pan, Email: 514849199@qq.com.

Yong Zhang, Email: bioyongzhang@swu.edu.cn.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Albanesi, D. , Mansilla, M.C. , Schujman, G.E. & de Mendoza, D. (2005) Bacillus subtilis cysteine synthetase is a global regulator of the expression of genes involved in sulfur assimilation. Journal of Bacteriology, 187, 7631–7638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlat, M. , Gough, C.L. , Zischek, C. , Barberis, P.A. , Trigalet, A. & Boucher, C.A. (1992) Transcriptional organization and expression of the large hrp gene cluster of Pseudomonas solanacearum . Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, 5, 187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.H. , Gaynor, J.B. , White, K.G. , Lopez, C. , Bosio, C.M. , Karkhoff‐Chweizer, R.R. et al. (2005) A Tn7‐based broad range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nature Methods, 2, 443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll, N.S. & Valls, M. (2013) Current knowledge on the Ralstonia solanacearum type III secretion system. Microbial Biotechnology, 6, 614–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corral, J. , Sebastià, P. , Coll, N.S. , Barbé, J. , Aranda, J. & Valls, M. (2020) Twitching and swimming motility play a role in Ralstonia solanacearum pathogenicity. mSphere, 4, e00740‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnac, S. , Occhialini, A. , Barberis, P. , Boucher, C. & Genin, S. (2004) Inventory and functional analysis of the large Hrp regulon in Ralstonia solanacearum: identification of novel effector proteins translocated to plant host cells through the type III secretion system. Molecular Microbiology, 53, 115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny, T.P. (1995) Involvement of bacterial polysaccharides in plant pathogenesis. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 33, 173–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow, J.M. , Hudson, L.L. , Wells, G. , Coleman, J.P. & Pesci, E.C. (2015) CysB negatively affects the transcription of pqsR and Pseudomonas quinolone signal production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Journal of Bacteriology, 197, 1988–2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genin, S. (2010) Molecular traits controlling host range and adaptation to plants in Ralstonia solanacearum . New Phytologist, 187, 920–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genin, S. , Brito, B. , Denny, T.P. & Boucher, C. (2005) Control of the Ralstonia solanacearum Type III secretion system (Hrp) genes by the global virulence regulator PhcA. FEBS Letters, 579, 2077–2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genin, S. & Denny, T.P. (2012) Pathogenomics of the Ralstonia solanacearum species complex. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 50, 67–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyaneshwar, P. , Paliy, O. , McAuliffe, J. , Popham, D.L. , Jordan, M.I. & Kustu, S. (2005) Sulfur and nitrogen limitation in Escherichia coli K‐12: specific homeostatic responses. Journal of Bacteriology, 187, 1074–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, J.L. & Mullholland, C.V. (2018) Cysteine biosynthesis in Neisseria species. Microbiology, 164, 1471–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikichi, Y. , Mori, Y. , Ishikawa, S. , Hayashi, K. , Ohnishi, K. , Kiba, A. et al. (2017) Regulation involved in colonization of intercellular spaces of host plants in Ralstonia solanacearum . Frontiers in Plant Science, 8, 967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J. & Schell, M. (1995) Molecular characterization of the eps gene cluster of Pseudomonas solanacearum and its transcriptional regulation at a single promoter. Molecular Microbiology, 16, 977–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J. , Yindeeyoungyeon, W. , Garg, R.P. , Denny, T.P. & Schell, M.A. (1998) Joint transcriptional control of xpsR, the unusual signal integrator of the Ralstonia solanacearum virulence gene regulatory network, by a response regulator and a LysR‐type transcriptional activator. Journal of Bacteriology, 180, 2736–2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwanicka‐Nowicka, R. & Hryniewicz, M. (1995) A new gene, cbl, encoding a member of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators belongs to Escherichia coli cys regulon. Gene, 166, 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwanicka‐Nowicka, R. , Zielak, A. , Cook, A.M. , Thomas, M.S. & Hryniewicz, M. (2007) Regulation of sulfur assimilation pathways in Burkholderia cenocepacia: identification of transcription factors CysB and SsuR and their role in control of target genes. Journal of Bacteriology, 189, 1675–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janse, J.D. , Beld, H.E.V.D. , Elphinstone, J. , Simpkins, S. , Tjou‐Tam‐Sin, N.N.A. & Vaerenbergh, J.V. (2004) Introduction to Europe of Ralstonia solanacearum biovar 2 race 3 in Pelargonium zonale cuttings. Journal of Plant Pathology, 86, 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Javaux, C. , Joris, B. & De Witte, P. (2007) Functional characteristics of TauA binding protein from TauABC Escherichia coli system. Protein Journal, 26, 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, G. , Wei, Z. , Xu, J. , Chen, H. , Zhang, Y. , She, X. et al. (2017) Bacterial wilt in China: history, current status, and future perspectives. Frontiers in Plant Science, 8, 1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.D.G. & Dangl, J.L. (2006) The plant immune system. Nature, 444, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, A. , Ohnishi, S. , Tomiyama, H. , Hasegawa, H. , Yasukohchi, M. , Kiba, A. et al. (2003) Type III secretion machinery‐deficient mutants of Ralstonia solanacearum lose their ability to colonize resulting in loss of pathogenicity. Journal of General Plant Pathology, 69, 250–257. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, A. & Hruschka, J. (1973) The role of motility and aerotaxis in the selective increase of avirulent bacteria in still broth cultures of Pseudomonas solanacearum . Journal of General Microbiology, 76, 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz, M.A. (2000) Riding the sulfur cycle‐metabolism of sulfonates and sulfate esters in gram‐negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 24, 135–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzuma, A. , Endoh, T. , Omori, T. , Nojiri, H. , Yamane, H. & Habe, H. (2008) Transcription factors CysB and SfnR constitute the hierarchical regulatory system for the sulfate starvation response in Pseudomonas putida . Journal of Bacteriology, 190, 4521–4531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.M. , Chou, I.C. , Wang, J.F. , Ho, F.I. , Chu, Y.J. , Huang, P.C. et al. (2008) Transposon mutagenesis reveals differential pathogenesis of Ralstonia solanacearum on tomato and Arabidopsis . Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, 21, 1261–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochowska, A. , Iwanicka‐Nowicka, R. , Plochocka, D. & Hryniewicz, M. (2001) Functional dissection of the LysR‐type CysB transcriptional regulator: regions important for DNA binding, inducer response, oligomerization, and positive control. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 276, 2098–2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe‐Power, T.M. , Hendrich, C.G. , Von Roepenack‐Lahaye, E. , Li, B. , Wu, D. , Mitra, R. et al. (2018) Metabolomics of tomato xylem sap during bacterial wilt reveals Ralstonia solanacearum produces abundant putrescine, a metabolite that accelerates wilt disease. Environmental Microbiology, 20, 1330–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S. , Wang, J. , Chitsaz, F. , Derbyshire, M.K. , Geer, R.C. , Gonzales, N.R. et al. (2020) CDD/SPARCLE: the conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Research, 8, D265–D268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddocks, S.E. & Oyston, P.C.F. (2008) Structure and function of the LysR‐type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family proteins. Microbiology, 154, 3609–3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, J. , Genin, S. , Magori, S. , Citovsky, V. , Sriariyanum, M. , Ronald, P. et al. (2012) Top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria in molecular plant pathology. Molecular Plant Pathology, 13, 614–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.H. (1992) The lac system. In: Miller, J.H. (Ed.) A short course in bacterial genetics. A laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, pp. 43–80. [Google Scholar]

- Milling, A. , Babujee, L. & Allen, C. (2011) Ralstonia solanacearum extracellular polysaccharide is a specific elicitor of defense responses in wilt‐resistant tomato plants. PLoS One, 6, e15853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Y. , Inoue, K. , Ikeda, K. Nakayashiki, H. , Higashimoto, C. , Ohnishi, K. et al. (2016) The vascular plant pathogenic bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum produces biofilms required for its virulence on the surfaces of tomato cells adjacent to intercellular spaces. Molecular Plant Pathology, 17, 890–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukaihara, T. , Tamura, N. & Iwabuchi, M. (2010) Genome‐wide identification of a large repertoire of Ralstonia solanacearum type III effector proteins by a new functional screen. Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, 23, 251–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, C.T. , Moutran, A. , Fessel, M. & Balan, A. (2015) The sulfur/sulfonates transport systems in Xanthomonas citri pv. citri. BMC Genomics, 16, 524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plener, L. , Manfredi, P. , Valls, M. & Genin, S. (2010) PrhG, a transcriptional regulator responding to growth conditions, is involved in the control of the type III secretion system regulon in Ralstonia solanacearum . Journal of Bacteriology, 192, 1011–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Ploeg, J.R. , Eichhorn, E. & Leisinger, T. (2001) Sulfonate‐sulfur metabolism and its regulation in Escherichia coli . Archives of Microbiology, 176, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Ploeg, J.R. , Iwanicka‐Nowicka, R. , Bykowski, T. , Hryniewicz, M.M. & Leisinger, T. (1999) The Escherichia coli ssuEADCB gene cluster is required for the utilization of sulfur from aliphatic sulfonates and is regulated by the transcriptional activator Cbl. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 274, 29358–29365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Ploeg, J.R. , Iwanicka‐Nowicka, R. , Kertesz, M.A. , Leisinger, T. & Hryniewicz, M.M. (1997) Involvement of CysB and Cbl regulatory proteins in expression of the tauABCD operon and other sulfate starvation‐inducible genes in Escherichia coli . Journal of Bacteriology, 179, 7671–7678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, D.P. , Denny, T.P. & Schell, M.A. (1988) Cloning of the egl gene of Pseudomonas solanacearum and analysis of its role in phytopathogenicity. Journal of Bacteriology, 170, 1445–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salanoubat, M. , Genin, S. , Artiguenave, F. , Gouzy, J. , Mangenot, S. , Arlat, M. et al. (2002) Genome sequence of the plantpathogen Ralstonia solanacearum . Nature, 415, 497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, F. , Yin, W. , Song, S. , Zhang, Z. , Ye, P. , Zhang, Y. et al. (2020) Ralstonia solanacearum promotes pathogenicity by utilizing L‐glutamic acid from host plants. Molecular Plant Pathology, 21, 1099–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y. , Yang, C. , Chen, G. , Zhang, Y. , Seng, Z. , Cai, Z. et al. (2019) Molecular insights into the master regulator CysB‐mediated bacterial virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Molecular Microbiology, 111, 1195–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stec, E. , Witkowska‐Zimny, M. , Hryniewicz, M.M. , Neumann, P. , Wilkinson, A.J. , Brzozowski, A.M. et al. (2006) Structural basis of the sulphate starvation response in E. coli: crystal structure and mutational analysis of the cofactor‐binding domain of the Cbl transcriptional regulator. Journal of Molecular Biology, 364, 309–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tans‐Kersten, J. , Huang, H. & Allen, C. (2001) Ralstonia solanacearum needs motility for invasive virulence on tomato. Journal of Bacteriology, 183, 3597–3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valls, M. , Genin, S. & Boucher, C. (2006) Integrated regulation of the type III secretion system and other virulence determinants in Ralstonia solanacearum . PLoS Pathogens, 2, e82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasse, J. , Frey, P. & Trigalet, A. (1995) Microscopic studies of intercellular infection and protoxylem invasion of tomato roots by Pseudomonas solanacearum . Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, 8, 241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, J. & Allen, C. (2007) The plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum needs aerotaxis for normal biofilm formation and interactions with its tomato host. Journal of Bacteriology, 189, 6415–6424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimochi, T. , Hikichi, Y. , Kiba, A. & Ohnishi, K. (2009a) The global virulence regulator PhcA negatively controls the Ralstonia solanacearum hrp regulatory cascade by repressing expression of the PrhIR signaling proteins. Journal of Bacteriology, 191, 3424–3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimochi, T. , Zhang, Y. , Kiba, A. , Hikichi, Y. & Ohnishi, K. (2009b) Expression of hrpG and activation of response regulator HrpG are controlled by distinct signal cascades in Ralstonia solanacearum . Journal of General Plant Pathology, 75, 196–204. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Cao, Y. , Zhang, L. , Hikichi, Y. & Ohnishi, K. (2021) The Tn7‐based genomic integration is dependent on an attTn7 box in the glms gene and is site‐specific with monocopy in Ralstonia solanacearum species complex. Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, 34, 720–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Chen, L. , Takehi, Y. , Kiba, A. , Hikichi, Y. & Ohnishi, K. (2013) Functional analysis of Ralstonia solanacearum PrhG regulating the hrp regulon in host plants. Microbiology, 159, 1695–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Kiba, A. , Hikichi, Y. & Ohnishi, K. (2011) prhKLM genes of Ralstonia solanacearum encode novel activators of hrp regulon and are required for pathogenesis in tomato. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 317, 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Li, J. , Zhang, W. , Shi, H. , Luo, F. , Hikichi, Y. et al. (2018) A putative LysR‐type transcriptional regulator PrhO positively regulates the type III secretion system and contributes to the virulence of Ralstonia solanacearum . Molecular Plant Pathology, 19, 1808–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Luo, F. , Wu, D. , Hikichi, Y. , Kiba, A. , Igarashi, Y. et al. (2015) PrhN, a putative MarR family transcriptional regulator, is involved in positive regulation of type III secretion system and full virulence of Ralstonia solanacearum . Frontiers in Microbiology, 6, 357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Zhang, W. , Han, L. , Li, J. , Shi, X. , Hikichi, Y. et al. (2019) Involvement of a PadR regulator PrhP on virulence of Ralstonia solanacearum by controlling detoxification of phenolic acids and type III secretion system. Molecular Plant Pathology, 20, 1477–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuluaga, A.P. , Puigvert, M. & Valls, M. (2013) Novel plant inputs influencing Ralstonia solanacearum during infection. Frontiers in Microbiology, 4, 349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

TABLE S1. Primers used in this study

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.