Abstract

To further understand the role of penicillin-binding protein 2a (PBP 2a) of Streptococcus pneumoniae in penicillin resistance, we confirmed the identity of the protein as PBP 2a. The PBP 2a protein migrated electrophoretically to a position corresponding to that of PBP 2x, PBP 2a, and PBP 2b of S. pneumoniae and was absent in a pbp2a insertional mutant of S. pneumoniae. We found that the affinities of PBP 2a for penicillins were lower than for cephalosporins and a carbapenem. When compared with other S. pneumoniae PBPs, PBP 2a exhibited lower affinities for β-lactam antibiotics, especially penicillins. Therefore, PBP 2a is a low-affinity PBP for β-lactam antibiotics in S. pneumoniae.

Streptococcus pneumoniae, one of the major human pathogens of the upper respiratory tract, has developed resistance to many β-lactam antibiotics (2, 3, 6–9, 12–14) due to the formation of high-molecular-mass penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) with reduced affinity for these antibiotics (2, 3, 6–9, 12–14, 21, 25, 26). S. pneumoniae contains five detectable high-molecular-mass PBPs: PBP 1a, PBP 1b, PBP 2a, PBP 2x, and PBP 2b (7–9, 13–15, 21). The role of PBP 1a, PBP 2b, and PBP 2x in their resistance to β-lactam antibiotics is well understood (2, 3, 6–9, 12–14, 21, 25, 26). In contrast, the involvement of PBP 2a and in particular PBP 1b in penicillin resistance is not well characterized (13, 24–26). The genes encoding PBP 1b and PBP 2a have recently been sequenced (13, 15). Results of genetic and molecular analyses suggested that PBP 2a contributed to cefotaxime resistance in some clinical isolates and laboratory strains of S. pneumoniae (13, 24).

Results of the recent genetic studies have established that the pbp2a gene in combination with the pbp1b gene is essential for viability of S. pneumoniae (15, 22) and that the pbp2a-encoded transglycosylase may play a major role in peptidoglycan polymerization in the cell (15). In addition, an active form of PBP 2a lacking its transmembrane domain has been obtained and shown to contain two distinct transpeptidase and transglycosylase domains that could be physically separated (5, 28).

In this study, we report the biochemical identification and characterization of PBP 2a from S. pneumoniae. The results of this study suggest that PBP 2a, unlike other PBPs of S. pneumoniae, has a low affinity for β-lactam antibiotics.

The materials used in this study are as follows: cephalothin, penicillin G, and cephalexin (Eli Lilly); cefuroxime and ceftazidime (Glaxo); imipenem (Merck); methicillin, oxacillin, and cefotaxime (Sigma); piperacillin (American Cyanamid); BOCILLIN FL (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, Oreg.); thrombin (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology, Alameda, Calif.), and Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (Bio 101, Inc., La Jolla, Calif.). The remaining materials used were the same as those described previously (28).

To purify glutathione S-transferase (GST)-PBP 2a* that lacks its transmembrane domain, Escherichia coli cells harboring pGEX-2T/pbp2a* (28) were grown, induced, harvested, and disrupted as described previously (28). The inclusion bodies of GST-PBP 2a* were then purified, refolded, and stored at −70°C as described previously (28). Protein concentrations were determined, also as described (28).

The transpeptidase activity of PBP 2a was assayed by measuring its ability to hydrolyze S2d, an analog of the bacterial cell wall stem peptides (1, 16, 17, 30). For 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) determinations, reaction mixtures (1 ml each) contained 52 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7), 2.0 mM S2d, 0.5 mM 4,4′-dithiopyridine, 80 μg of GST-PBP 2a*, and various amounts of antibiotics (30). The increase in A325 was monitored at 37°C for 2 min with a double-beam BioSpec-1601 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Instruments, Inc.). For Ki determinations, reaction mixtures (1 ml each) contained 52 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0), 0.5 mM 4,4′-dithiodipyridine, various amounts of S2d (0.5 to 8.0 mM), 80 μg of GST-PBP 2a*, and fixed amounts of each antibiotic.

To express the full-length pbp2a gene of S. pneumoniae (hex) R6 in E. coli for Western blotting analysis, the gene was cloned and sequenced as previously described (15) (accession no. AF101780). PCR amplification of the pbp2a gene was carried out as described below. The 5′ PCR primer (5′-TGATGAAG ATGATAAGGATCCCATATGAAATTAGATAAATTA-3′) was designed to begin at the ATG start codon of pbp2a based upon our known sequence (15) (accession no. AF101780) and contains added BamHI and NdeI sites for cloning purposes. The 3′ PCR primer (5′-GCTTTGACAAGCTTCTTAGCGAAAT-3′) was designed to end at the stop codon of pbp2a and contains an added HindIII site after the stop codon for cloning into the vector. The PCR mixtures contained ∼100 ng of S. pneumoniae (hex) R6 genomic DNA (15), 10 μl of 10× ThermoPol buffer containing 20 mM Mg2SO4 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.), 10 μl of 1-mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 8 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (2.5 mM), 1 μl of each primer (40 pmol), 3 U of Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs), and 66.5 μl of water. The following PCR amplification conditions were used: 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 50°C for 30 s, and polymerization at 72°C for 3 min for a total of 30 cycles. Resulting PCR products were purified using a QIAquick spin column (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.), and 1 μg of product was subjected to DNA sequence analysis (15).

Three identical PCR products were generated using the conditions described above and then digested with BamHI. This fragment was cloned into an expression vector, pET-11b (Novagen, Madison, Wis.). To verify that no errors were introduced during the PCR process, the DNA sequence of the entire pbp2a gene was determined following its cloning into pET-11b.

To analyze PBP 2a in the cell, Western blotting analysis was performed by using polyclonal antibodies against sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-denatured PBP 2a* which were prepared by Harlan Bioproducts for Science, Inc. (Indianapolis, Ind.). A purified and refolded GST-PBP 2a* protein preparation was digested with thrombin according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pharmacia), SDS denatured, and subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (19). Protein bands containing PBP 2a* were visualized by incubating the gel in 0.5 M KCl and 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, and excised (30). Each protein band containing approximately 100 μg of PBP 2a* was injected into New Zealand White rabbits.

To prepare membrane fractions for Western blotting analysis, the following insertional mutants of S. pneumoniae (hex) R6 were constructed as described previously (15): nanA::Eryr, pbp1b::Eryr, pbp2a::Eryr, and pbp1a::Eryr and grown in brain heart infusion medium (Difco) without shaking at 37°C. The cultures were collected at an optical density at 660 nm of 0.4 by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 10 min and washed with 20 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0.

E. coli BL21(DE3) [F− dcm ompT hsdS (rB− mB−) gal λ (DE3) (Camr)] (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) containing pET-11b-pbp2a (a pbp2a expression plasmid) and pET-11 was grown overnight at 32°C with vigorous shaking in LB medium (Bio 101) supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin/ml. The overnight cultures were inoculated into LB medium (1:30) containing ampicillin and induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 to 0.6 for 2 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation and washed with 20 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.2.

The collected cells of E. coli and S. pneumoniae were resuspended in 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.5)–140 mM NaCl and disrupted by passing twice through a French pressure cell (Aminco Laboratories, Inc., Rochester, N.Y.). The resulting suspensions were centrifuged. Supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 45 min. Pellets (membrane fractions) were collected, washed with, and resuspended in the same phosphate buffer (1 ml each). The membrane fractions were denatured by SDS and subjected to Western blotting analysis as described previously (30). The polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were blocked in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (Gibco BRL) containing 5% dry milk at 4°C overnight, incubated with primary antibodies (1:500 dilutions) and secondary antibodies (1:2,000) for 2 to 3 h at room temperature.

To detect PBPs, we performed penicillin-binding assays (29) by using BOCILLIN FL, a fluorescent penicillin, as a labeling reagent (Molecular Probes). S. pneumoniae nanA (hex) R6 and pbp1a mutants, and E. coli BL21(DE3) strains carrying pET-11b and pET11b-pbp2a plasmids, were grown, collected, disrupted, and centrifuged as described above. For detection of PBPs, 75 μl of each membrane fraction was mixed with 25 μl of 100 μM BOCILLIN FL (final concentration, 25 μM), incubated at 35°C for 20 min, and denatured with 100 μl of SDS denaturing solution (19). The denatured reaction mixtures (5 to 10 μl each) were loaded onto a polyacrylamide gel (10%; Bio-Rad). The presence of PBPs was detected using a FluorImager 575 (excitation at 488 nm and emission at 530 nm) (Molecular Dynamics, Inc., Sunnyvale, Calif.) (29).

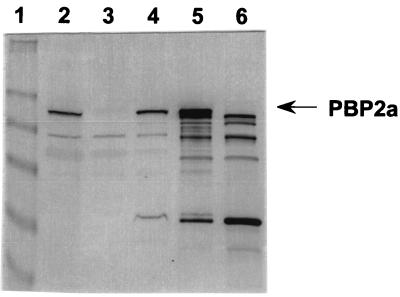

Western blotting and penicillin-binding assay analyses of PBP 2a in the cell.

As the pbp2a gene of S. pneumoniae was recently cloned and sequenced (13, 15), we wanted to confirm the identity of its gene product. Membrane preparations of S. pneumoniae (hex) R6, pbp1a and pbp2a mutants, and a pbp2a overexpresser strain of E. coli were subjected to Western blotting analysis (Fig. 1). A protein band with a molecular mass of approximately 82 kDa was detected in the membrane fractions of the nanA::Eryr and pbp1a::Eryr mutants of S. pneumoniae (lanes 2 and 4), but this protein band was absent in the membrane fraction of the pbp2a::Eryr mutant (lane 3). A protein with an identical molecular mass was also detected in the membrane fraction of E. coli BL21 (DE3) that contained multiple copies of the S. pneumoniae pbp2a expression plasmid (lane 5), but it was absent in the membrane fraction of E. coli control cells containing the vector only (lane 6). The results of our Western blotting analysis showed that the pbp2a gene was expressed in S. pneumoniae, that PBP 2a is a membrane protein consistent with the presence of a transmembrane domain at the N terminus of the protein (15), and that the pbp2a mutant is indeed missing PBP 2a.

FIG. 1.

Western blotting analysis of PBP 2a from S. pneumoniae (hex) R6. Lane 1, prestained molecular mass markers (from top to bottom: myosin, 250 kDa; BSA, 98 kDa; glutamic dehydrogenase, 64 kDa; alcohol dehydrogenase, 50 kDa; carbonic anhydrase, 36 kDa; and myoglobin, 30 kDa); lanes 2 through 4, membrane fractions of S. pneumoniae (nanA) (parent strain) and pbp2a and pbp1a insertional mutants, respectively; lanes 5 and 6, membrane fractions of E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-11b-pbp2a and E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-11b, respectively.

We also showed that PBP 2a was expressed in E. coli and was able to bind BOCILLIN FL, a fluorescent derivative of penicillin V (data not shown). Full-length PBP 2a expressed in E. coli migrated to the same positions as PBP 2x and PBP 2a of S. pneumoniae (data not shown), further confirming the identity of this protein as PBP 2a.

It is interesting that the predicted molecular mass of PBP 2a (89.4 kDa) is significantly larger than that of PBP 1b (80.8 kDa) (13, 15). Since S. pneumoniae PBP 1b migrates more slowly than PBP 2a when resolved by SDS-PAGE (13, 14), the unusual size difference between these two PBPs has made their assignment more difficult. However, our overexpression of PBP 2a in E. coli clearly established that PBP 2a did indeed migrate to a position very similar to those of PBP 2x, PBP 2a, and PBP 2b when separated by SDS-PAGE. Thus, the gene-encoded product was identified as the PBP 2a protein.

Affinities of GST-PBP 2a* for different β-lactam antibiotics.

To examine the affinities of GST-PBP 2a* for different β-lactam antibiotics, first we analyzed its kinetic parameters using standard steady-state methods with S2d as a substrate. The apparent Km and Vmax (kcat) values obtained for the GST-PBP 2a* enzyme were 3 mM and 210 nmol/min/mg (0.35 s−1), respectively. Similar results were obtained for PBP 2a* (data not shown). Thus, the kcat/Km value for GST-PBP 2a* was determined to be 120 M−1 s−1, which is in agreement with the value (220 M−1 s−1) obtained for PBP 2a* that was purified and refolded by using different methods (5). In light of these results, our kinetic analyses were performed with GST-PBP 2a* rather than with PBP 2a*, because both proteins appeared to exhibit similar kinetic properties, optimal activities at pH 6.0 and 50°C, and similar levels of binding activities to BOCILLIN FL, a derivative of penicillin V (28, 29).

The IC50s and Ki values of the enzyme determined for various β-lactam antibiotics are in good agreement with each other (Table 1). Using the IC50s obtained and the k2/K value (acylation efficiency) of the enzyme for cefotaxime (5), we derived the k2/K values of the enzyme for other antibiotics tested (10, 11) (Table 1). When compared with other PBPs in S. pneumoniae (4, 16, 17, 29), clearly, the k2/K values obtained indicate that GST-PBP 2a* had lower affinities for all β-lactam antibiotics tested, in particular for penicillins (Table 1). In addition, the affinities of GST-PBP 2a* for penicillins were, in general, lower than for cephalosporins (except ceftazidime) and imipenem (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Affinities of S. pneumoniae GST-PBP 2a* for different β-lactam antibioticsa

| Antibiotics | Ki (μM) | IC50 (μM) | k2/K (M−1 s−1)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillin | |||

| Penicillin G | 21 | 30 | 640 |

| Piperacillin | 55 | 85 | 230 |

| Oxacillin | 63 | 95 | 200 |

| Methicillin | 143 | 200 | 100 |

| Carbapenem | |||

| Imipenem | 1 | 1.4 | 13,800 |

| Cephalosporin | |||

| Cefuroxime | 0.9 | 1.6 | 12,000 |

| Cefotaxime | 1.9 | 2.5 | 7,700c |

| Cephalothin | 3.3 | 6 | 3,200 |

| Cephalexin | 9.3 | 14 | 1,400 |

| Ceftazidime | 227 | 380 | 50 |

The GST-PBP 2a* protein of S. pneumoniae was purified and refolded as previously described (28). The IC50s and Ki values were determined under the conditions as described in the text.

The k2/K values derived from the IC50s based on the k2/K value of PBP 2a for cefotaxime (5).

The k2/K value was taken from reference 5.

The PBP 2a protein is known to be involved in cefotaxime-resistance in some clinical isolates and laboratory strains of S. pneumoniae (13, 24). GST-PBP 2a* appeared to have a relatively good affinity for cefotaxime compared with other antibiotics tested (Table 1). The k2/K values of the GST-PBP 2a* protein for cefotaxime was 7,700 M−1 s−1 as determined by a fluorescence-quenching method (5). Using this fluorescence-quenching method, Di Guilmi et al. (5) failed to obtain a k2/K value of PBP 2a* for penicillin G due to its poor affinity for the enzyme. This observation is consistent with our finding that the affinity of this enzyme for penicillin G is significantly (approximately 12-fold) lower than for cefotaxime (Table 1). Furthermore, the k2/K values of the GST-PBP 2a* protein for penicillins (Table 1) were significantly lower than the values (58,000, 53,000, 21,000, and 4,900 M−1 s−1, respectively) obtained for the penicillin-sensitive PBP 2x of S. pneumoniae (17, 29), which is known as a primary penicillin-resistance determinant in the cell (12–18, 20, 23, 25, 26). The k2/K values of GST-PBP 2a* for penicillin G and cefotaxime were also significantly lower than the values (34,200 to 70,100 and 11,900 to 25,800 M−1 s−1, respectively) obtained for PBP 1a (4). Finally, the k2/K values of GST-PBP 2a* for imipenem, a carbapenem, and cefotaxime, a cephalosporin (Table 1), were also lower than the values (107,000 and 162,000 M−1 s−1) obtained for the penicillin-sensitive PBP 2x (17, 29). The k2/K value of PBP 2a for cephalexin was similar to that (1,600 M−1 s−1) of PBP 2x (17). Together, the results of this study suggest that PBP 2a is a low-affinity PBP compared with other PBPs in S. pneumoniae. These results also suggest that PBP 2a is a naturally resistant form of PBP and therefore probably is not a principal target of β-lactam antibiotics. It is also possible that PBP 2a might be able to take over the activity of other PBPs in the presence of clinically relevant concentrations of β-lactam antibiotics, which may therefore have accounted for its role in resistance to β-lactam antibiotics.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Treadway for providing S. pneumoniae cells used in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam M, Damblon C, Plaitin B, Christiaens L, Frere J-M. Chromogenic depsipeptide substrates for β-lactamases and penicillin-sensitive DD-peptidases. Biochem J. 1990;270:525–529. doi: 10.1042/bj2700525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barcus V A, Ghanekar K, Yeo M, Coffey T J, Dowson C G. Genetics of high level penicillin resistance in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;126:299–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coffey T J, Daniels M, McDougal L K, Dowson C G, Tenover F C, Spratt B G. Genetic analysis of clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae with high-level resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1306–1313. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Guilmi A M, Mouz N, Andrieu J-P, Hoskins J, Jaskunas S R, Gagnon J, Dideberg O, Vernet T. Identification, purification, and characterization of transpeptidase and glycosyltransferase domains of Streptococcus pneumoniae penicillin-binding protein 1a. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5652–5659. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5652-5659.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Guilmi A M, Mouz N, Martin L, Hoskins J, Jaskunas S R, Dideberg O, Vernet T. Glycosyltransferase domain of penicillin-binding protein 2a from Streptococcus pneumoniae is membrane associated. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2773–2781. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.9.2773-2781.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowson C G, Coffey T J, Spratt B G. Origin and molecular epidemiology of penicillin-binding protein-mediated resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:361–366. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90612-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowson C G, Hutchison A, Brannigan J A, George R C, Hansman D, Linares J, Tomasz A, Maynard Smith J, Spratt B G. Horizontal transfer of penicillin-binding protein genes in penicillin resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8842–8846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowson C G, Hutchison A, Spratt B G. Extensive remodeling of the transpeptidase domain of penicillin-binding protein 2B of a penicillin-resistant South African isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:95–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowson C G, Hutchison A, Woodford N, Johnson A P, George R C, Spratt B G. Penicillin-resistant viridans streptococci have obtained altered penicillin-binding protein genes from penicillin-resistant strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5858–5862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frere J-M, Nguyen-Disteche M, Coyette J, Joris B. Mode of action: interaction with the penicillin-binding proteins. In: Page M I, editor. The chemistry of β-lactams. Glasgow, Scotland: Chapman and Hall; 1992. pp. 148–197. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Granier B, Jamin M, Adam M, Galleni M, Lakaye B, Zorzi W, Grandchamps J, Wilkin J-M, Fraipont C, Joris B, Duez C, Nguyen-Disteche M, Coyette J, Leyh-Bouille M, Dusart J, Christiaens L, Frere J-M, Ghuysen J-M. Serine-type D-ala-D-ala peptidases and penicillin-binding proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1994;244:249–265. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)44021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grebe T, Hakenbeck R. Penicillin-binding proteins 2b and 2x of Streptococcus pneumoniae are primary resistance determinants for different classes of β-lactam antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:829–834. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.4.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hakenbeck R, König A, Kern I, van der Linden M, Keck W, Billot-Klein D, Legrand R, Schoot B, Gutmann L. Acquisition of five high-Mr penicillin-binding protein variants during transfer of high-level β-lactam resistance from Streptococcus mitis to Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1831–1840. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1831-1840.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hakenbeck R, Tarpay M, Tomasz A. Multiple changes of penicillin-binding proteins in penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;17:364–371. doi: 10.1128/aac.17.3.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoskins J, Matsushima P, Mullen D L, Tang J, Zhao G, Meier T I, Nicas T I, Jaskunas S R. Gene disruption studies of penicillin-binding proteins 1a, 1b, and 2a in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6552–6555. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6552-6555.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamin M, Damblon C, Millier S, Hakenbeck R, Frere J-M. Penicillin-binding protein 2x of Streptococcus pneumoniae: enzymic activities and interactions with β-lactams. Biochem J. 1993;292:735–741. doi: 10.1042/bj2920735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jamin M, Hakenbeck R, Frere J-M. Penicillin-binding protein 2x as a major contributor to intrinsic β-lactam resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEBS Lett. 1993;331:101–104. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80305-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kell C M, Sharma U K, Dowson C G, Town C, Balganesh T S, Spratt B G. Deletion analysis of the essentiality of penicillin-binding proteins 1A, 2B and 2X of Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;106:171–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb05954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laible G, Hakenbeck R, Sicard M A, Joris B, Ghuysen J-M. Nucleotide sequences of the pbpx genes encoding the penicillin-binding proteins 2x from Streptococcus pneumoniae R6 and a cefotaxime-resistant mutant, C506. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1337–1348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laible G, Spratt B G, Hakenbeck R. Interspecies recombinational events during the evolution of altered PBP 2x genes in penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1993–2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paik J, Kern I, Lurz R, Hakenbeck R. Mutational analysis of the Streptococcus pneumoniae bimodular class A penicillin-binding proteins. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3852–3856. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3852-3856.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pares S, Mouz N, Petillot Y, Hakenbeck R, Dideberg O. X-ray structure of Streptococcus pneumoniae PBP2x, a primary penicillin target enzyme. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:284–289. doi: 10.1038/nsb0396-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reichmann P, Konig A, Marton A, Hakenbeck R. Penicillin-binding proteins as resistance determinants in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb Drug Resist. 1996;2:177–181. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spratt B G. Resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. In: Ghuysen J-M, Hakenbeck R, editors. Bacterial cell wall. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science B.V.; 1994. pp. 517–534. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomasz A, Munoz R. β-Lactam antibiotic resistance in Gram-positive bacterial pathogens of the upper respiratory tract: a brief overview of mechanisms. Microb Drug Resist. 1995;1:103–109. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1995.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Heijenoort J. Murein synthesis. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W C, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1025–1034. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao G, Meier T I, Hoskins J, Jaskunas S R. Penicillin-binding protein 2a of Streptococcus pneumoniae: expression in Escherichia coli, and purification and refolding of inclusion bodies into a soluble and enzymatically active enzyme. Protein Expr Purif. 1999;16:331–339. doi: 10.1006/prep.1999.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao G, Meier T I, Kahl S D, Gee K R, Blaszczak L C. BOCILLIN FL, a sensitive and commercially available reagent for detection of penicillin-binding proteins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1124–1128. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao G, Yeh W-K, Carnahan R H, Flokowitsch J, Meier T I, Alborn W E, Jr, Becker G W, Jaskunas S R. Biochemical characterization of penicillin-resistant and -sensitive penicillin-binding protein 2x transpeptidase activities of Streptococcus pneumoniae and mechanistic implications in bacterial resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4901–4908. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4901-4908.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]