Abstract

The massive explosion by the January 15, 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano in Tonga triggered a trans-oceanic tsunami generated by coupled ocean and atmospheric shock waves during the explosion. The tsunami reached first the coast of Tonga, and later many coasts around the world. The shock wave went around the globe, causing sea perturbations as far as the Caribbean and the Mediterranean seas. We present the effects of the January 15, 2022 Tonga tsunami on the Mexican Pacific Coast, Gulf of Mexico, and Mexican Caribbean coast, and discuss the underrated hazard caused by great volcanic explosions, and the role of early tsunami warning systems, in particular in Mexico. The shock wave took about 7.5 h to reach the coast of Mexico, located about 9000 km away from the volcano, and the signal lasted several hours, about 133 h (5.13 days). The shock wave was the only cause for sea alterations on the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea, while at the Mexican Pacific coast both shock wave and the triggered tsunami by the volcano eruption and collapse affected this coast. The first tsunami waves recorded on the Mexican Pacific coast arrived around 12:35 on January 15, at the Lázaro Cárdenas, Michoacán tide gauge station. The maximum tsunami height exceeded 2 m at the Ensenada, Baja California, and Manzanillo, Colima, tide gauge stations. Most tsunami warning advisories, with two exceptions, reached communities via social media (Twitter and Facebook), but did not clearly state that people must stay away from the shore. We suggest that, although no casualties were reported in Mexico, tsunami warning advisories of far-field tsunamis and those triggered non-seismic sources, such as landslides and volcanic eruptions, should be included and improved to reach coastal communities timely, explaining the associated hazards on the coast.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00024-022-03017-9.

Keywords: Volcanic explosion, Far-field tsunami, Shock wave, Tsunami warning, Tonga, Mexico

Introduction

Volcanic eruptions are frequent and occur in different parts of the world. However, massive explosions by volcanoes can trigger other hazards such as tsunamis. Tsunamis triggered by volcanic eruptions are generated by submarine landslides and caldera collapses (e.g., Maeno & Imamura, 2011; Nagai et al., 2021; Nomanbhoy & Satake, 1995; Pararas-Carayannis, 1992), and by coupled ocean and atmospheric shock waves during explosions (Bryant, 2001; Pelinovzky et al., 2005; Simkin & Fiske, 1983; Choi, 2003; Yokoyama, 1981). To generate coupled sea-atmospheric waves, volcanic eruptions must be large, e.g., the 1883 Krakatau eruption (Yokoyama, 1981). The latest is the case of the massive explosion by the January 15, 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano in Tonga. This kind of massive explosions occur less often. Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano had a powerful explosion back in 1100 AD, and big eruptions occur every ca. 1000 years (Cronnin et al., 2017). The 2022 generated tsunami reached first the coast of Tonga, and later many coasts around the world, such as those in the Pacific Ocean, and produced a shock wave that went around the globe, as far as the Caribbean Sea, Mediterranean Sea, and other places (PTWC, 2022; NTWC, 2022). Here we present and discuss tsunami effects on the Mexican Pacific Coast, Gulf of Mexico, and Mexican Caribbean coast, the underrated hazard caused by great volcanic explosions, and the role of early tsunami warning systems.

Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai Volcano Eruption of January 15, 2022

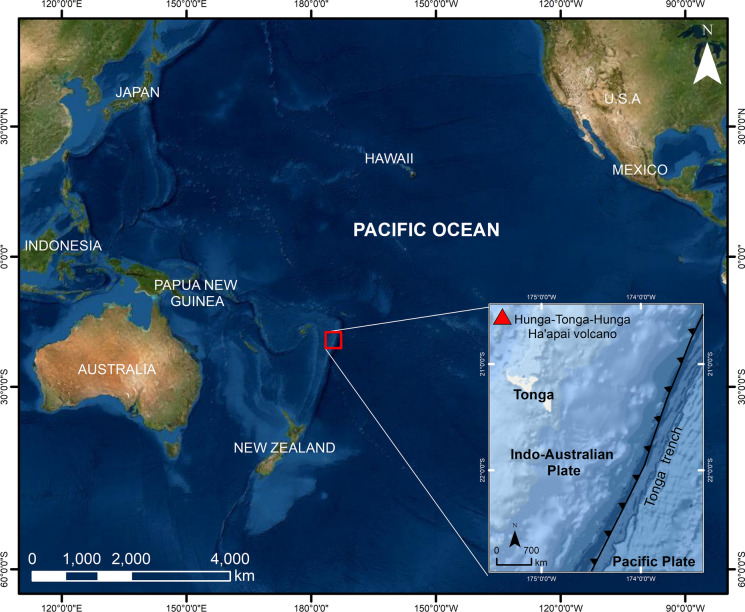

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano, located approximately 65 km north of Tongatapu, Nuku’alofa, in the South Pacific Ocean, produced a massive explosion on January 15, 2022, at 04:10 UTC time, sending a pressure wave around the globe, a huge volcanic plume more than 20 km high captured on satellite images, and triggering a tsunami that affected not only Tonga but my places across the Pacific (Fig. 1). The United States Geological Survey (USGS) reported the energy released by the eruption equivalent to a magnitude 5.8 earthquake (USGS, 2022).

Fig. 1.

Hunga-Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano tectonic setting

The Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai volcano is located along the Tonga-Kermedec Arc, where the Pacific plate subducts under the Indo-Australian plate, in the southwest Pacific. This volcano is largely underwater and is part of a chain of submarine volcanoes and has an approximately 6 km wide submerged caldera (Cronin, 2017). Recent volcanic eruptions in 2009, 2014, and 2015 (Cronin, 2017, 2022) showed the activity of this volcano, most recently initiated in December 2021 just before the January 15, 2022 massive explosion.

Shock Wave and Tsunami

The blast from the shock wave or pressure wave (produced by sudden change in pressure) generated by the volcanic explosion traveled large distances in the air at more than 1000 km per hour and was recorded globally, crossing Australia, Asia, UK, Europe, the Americas (Klein, 2022), and in Mexico it was captured at several weather stations (Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (SMN)—, 2022).

The tsunami triggered by the eruption of this submarine volcano inundated coastal areas and reached a height of 83 cm in Nuku’alofa, according to the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC, 2022), though the Nuku’alofa tide gauge recorded a tsunami wave of 1.19 m before it stopped recording (Watkins, 2022). This tsunami generated large waves that first hit the coast of Tonga, locally reporting waves as high as 15 m (Government of Tonga, 2022) reaching as far as Japan (1.1 m; PTWC, 2022) Chile, Peru (PTWC, 2022), California (1.1 m; NOAA, 2022), and Mexico among many others. This tsunami caused severe damage in Tonga, which is still assessed by local authorities, and damage has been reported on the Japan coast, California, and in Peru two people died (CNN, 2022) and an oil spill occurred on its coast impacting fauna and the environment (Taj, 2022).

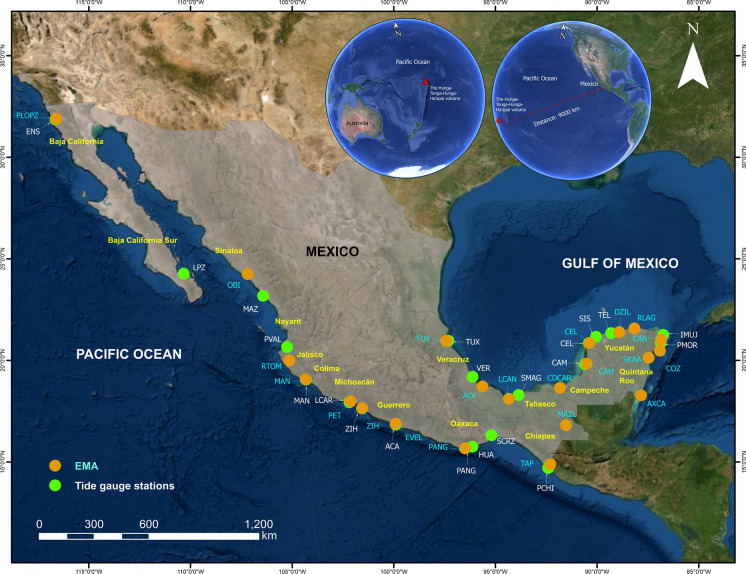

Data and Methods

Tsunami data was obtained from tide gauge stations from the National Tide Gauge Service (Servicio Mareográfico Nacional—SMN, for its acronym in Spanish) (SMN, 2022). Atmospheric pressure data were retrieved from the Automatic Weather Stations (Estaciones Meteorológicas Automáticas—"EMA" for its acronym in Spanish) from National Weather Service (Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (SMN)—Spanish acronym) at Comisión Nacional del Agua—CONAGUA (SMN-CONAGUA, 2022) (Fig. 2). Dates of sampling for weather stations and tide gauge stations were determined based on those days when perturbations were observed at the studied stations. Time is given in Coordinate Universal Time or UTC.

Fig. 2.

National Tide Gauge Service (SMN) and Automatic Weather Stations (EMA) stations on the Mexican coast. Automatic Weather Stations “EMA”—orange points,

source: SMN-CONAGUA (2022), and tide gauge stations from the National Tide Gauge Service “SMN”—green points (SMN, 2022). EMA stations: PLOPZ (Presa López Zamora), OBI (Obispo), RTOM (Río Tomatlán), MAN (Manzanillo), PET (Petacalco), ZIH (Zihuatanejo), EVEL (El Veladero), PANG (Puerto Ángel), TAP (Tapachula), MAZL (Montes Azules), AXCA (Arrecife Xcalak), SKAA (Sian Kaan), COZ (Cozumel), CAN (Cancún), RLAG (Río Lagartos), DZIL (Dzilam), CEL (Celestún), CAM (Campeche), CDCAR (Ciudad del Carmen), LCAN (La Cangrejera), ALV (Alvarado) y TUX (Tuxpan). The tide gauge stations: ENS (Ensenada), LPZ (La Paz), MAZ (Mazatlán), PVAL (Puerto Vallarta), MAN (Manzanillo), LCAR (Lázaro Cárdenas), ZIH (Zihuatanejo), ACA (Acapulco), HUA (Huatulco), PANG (Puerto Ángel), PCHI (Puerto Chiapas), PMOR (Puerto Morelos), IMUJ (Isla Mujeres), SIS (Sisal), CEL (Celestún), CAM (Campeche), SMAG (Sánchez–Magallanes), VER (Veracruz) y TUX (Tuxpan). Inserts show the average distance between the Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha'apai Volcano and Mexico. Data source: CONAGUA and SMN

Data collection on Tsunami Warning advisories, effects, casualties, and other relevant information was taken from news online, from social media (Twitter, Facebook, YouTube) and official internet sites.

Effects in Mexico by the Eruption-Triggered Tsunami in Tonga

Tide Gauge and Pressure Wave Data

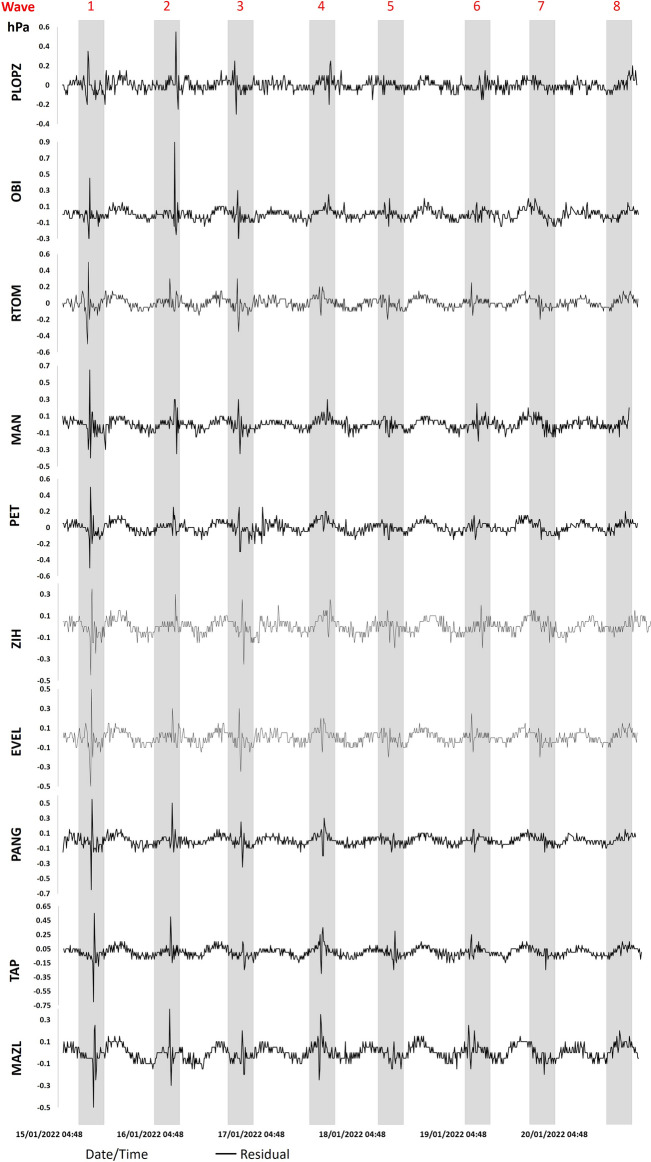

Shock Wave

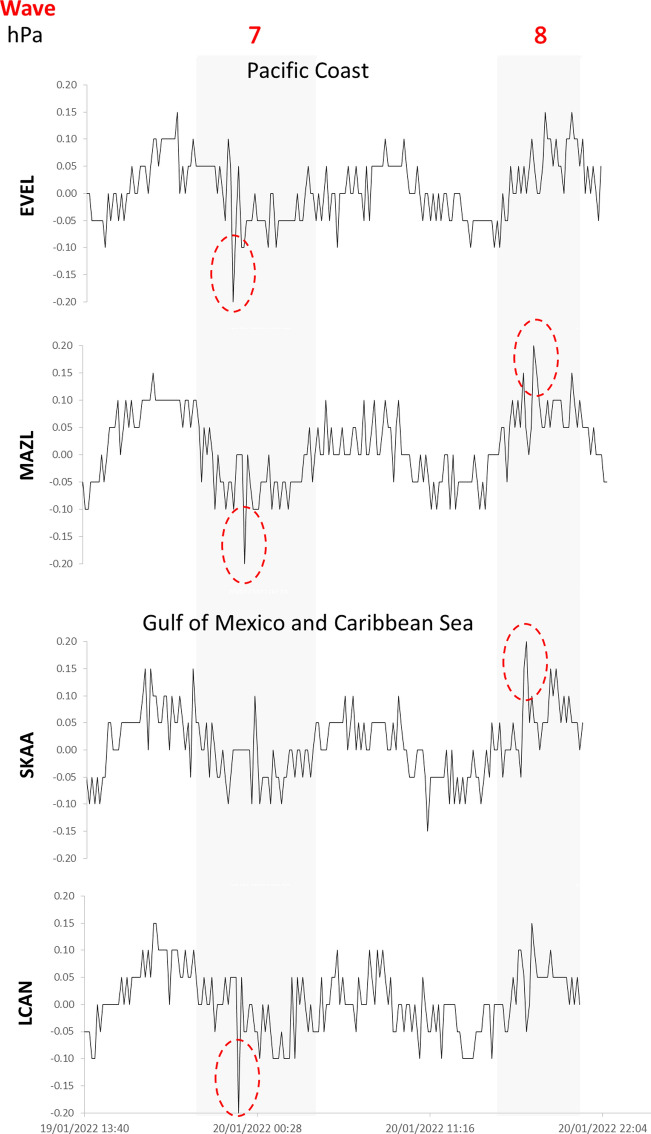

The shock wave generated by the eruption was recorded by several weather and infrasound stations around the globe. It took about 7.5 h to be recorded at weather stations in Mexico located about 9000 km away from the volcano eruption. The shock wave signal was captured by CONAGUA weather stations along the Pacific coast, at the Gulf of Mexico, and Caribbean Sea stations (Servicio Meteorológico Nacional—SMN, 2022). Since the shock wave traveled back and forth from the volcano eruption, and the signal from the shock wave caused by the volcanic explosion lasted several hours, the barometers recorded several peaks (up to 8) for about 133 h (5.13 days) (Fig. 3, 4 and 5, and Table 1). The zoom made on Figs. 3 and 4 shown on Fig. 5 on stations EVEL, MAZL, SKAA and LCAN, show up to 7 and 8 waves.

Fig. 3.

Shock waves recorded at the Mexican Pacific coast. Graphs show shock wave peaks generated by the Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha'apai Volcano explosion (8 peaks). Pacific stations.

Source: SMN-CONAGUA (2022)

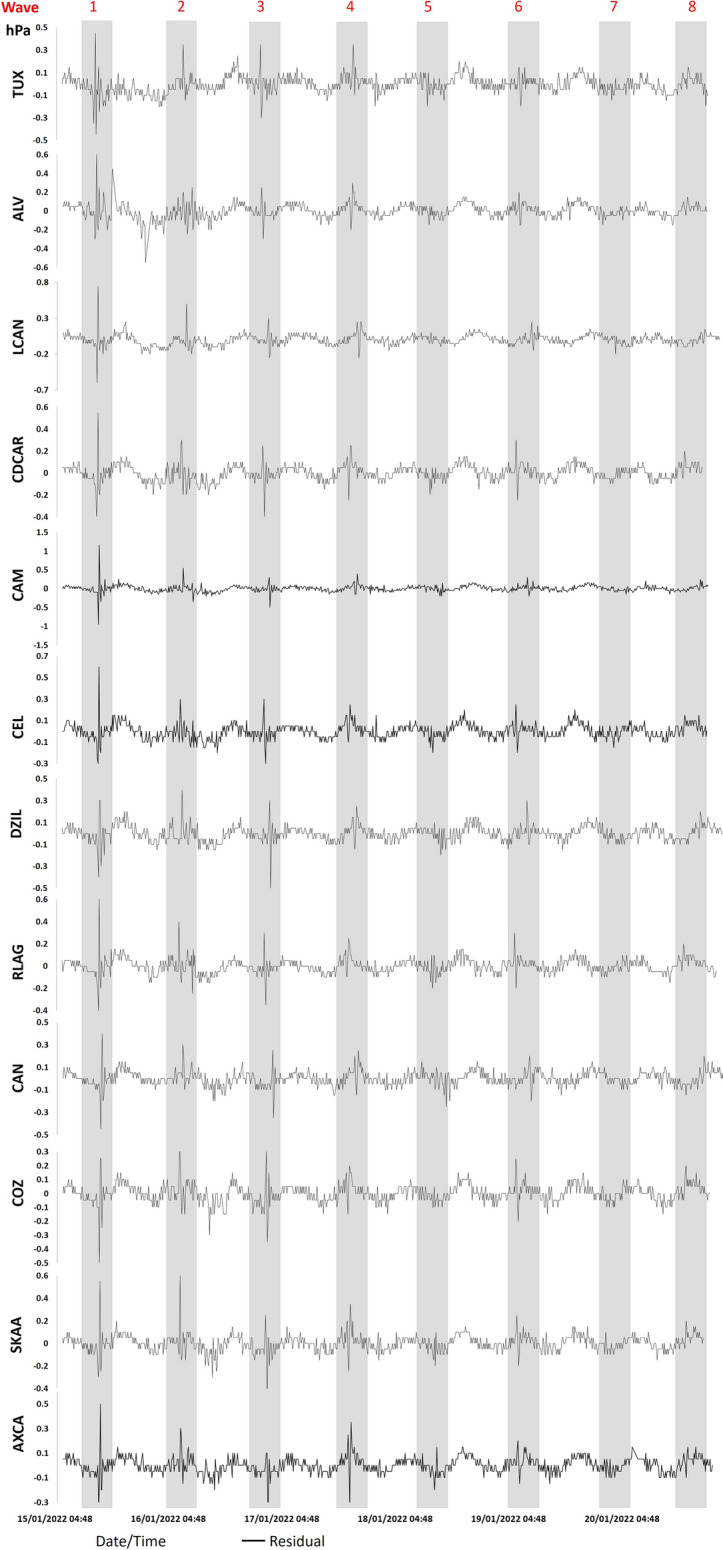

Fig. 4.

Shock wave peaks for the Gulf of Mexico and Mexican Caribbean Sea. Graphs show shock wave peaks generated by the Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha'apai Volcano explosion (8 peaks). Gulf of Mexico and Mexican Caribbean stations.

Source: SMN-CONAGUA (2022)

Fig. 5.

Shock wave peaks 7 and 8 (zoom) for the Pacific and Gulf of Mexico and Mexican Caribbean Sea.

Source: SMN-CONAGUA (2022)

Table 1.

Weather stations, shock wave arrival, and peak parameters.

Source: SMN-CONAGUA (2022)

| Station | Time/Day (P1) | Time/Day (P2) | Time/Day (P3) | Time/Day (P4) | Time/Day (P5) | Time/Day (P6) | Time/Day (P7) | Time/Day (P8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pacific | ||||||||

| PLOPZ | 12:00/15 | 09:00/16 | 22:40/16 | 20:50/17 | ||||

| OBI | 12:20/15 | 08:40/16 | 23:20/16 | 20:30/17 | 10:50/18 | 07:30/19 | ||

| RTOM | 12:20/15 | 08:40/16 | 23:30/16 | |||||

| MAN | 12:20/15 | 08:40/16 | 23:20/16 | 20:00/17 | 10:10/18 | 07:10/19 | ||

| PET | 12:30/15 | 08:30/16 | 23:40/16 | 20:00/17 | 10:30/18 | 07:10/19 | 22:40/19 | |

| ZIH | 12:30/15 | 08:30/16 | 23:50/16 | 20:00/17 | 10:40/18 | 07:10/19 | 22:40/19 | |

| EVEL | 12:40/15 | 08:30/16 | 23:50/16 | 20:00/17 | 10:50/18 | 07:00/19 | 22:50/19 | 18:20/20 |

| PANG | 12:50/15 | 08:00/16 | 00:10/17 | 19:20/17 | 11:10/18 | 06:40/19 | 23:10/19 | 18:00/20 |

| TAP | 13:10/15 | 07:40/16 | 00:30/17 | 19:10/17 | 11:10/18 | 06:10/19 | 23:30/19 | 17:30/20 |

| MAZL | 13:10/15 | 07:30/16 | 00:40/17 | 18:40/17 | 06:10/19 | 23:40/19 | 17:30/20 | |

| Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean | ||||||||

| TUX | 13:00/15 | 07:50/16 | 00:00/17 | 19:20/17 | 10:20/18 | 06:40/19 | ||

| ALV | 13:10/15 | 07:40/16 | 00:20/17 | 19:10/17 | 06:30/19 | 17:50/20 | ||

| LCAN | 13:10/15 | 07:40/16 | 00:20/17 | 19:10/17 | 06:30/19 | 23:20/19 | 17:50/20 | |

| CDCAR | 13:30/15 | 07:30/16 | 00:40/17 | 19:00/17 | 11:40/18 | 06:10/19 | 22:20/19 | 17:40/20 |

| CAM | 13:30/15 | 07:10/16 | 00:40/17 | 18:40/17 | 11:10/18 | 06:00/19 | 23:30/19 | 17:30/20 |

| CEL | 13:40/15 | 07:10/16 | 00:40/17 | 18:50/17 | 12:10/18 | 06:00/19 | ||

| DZIL | 13:40/15 | 07:00/16 | 00:50/17 | 18:40/17 | 11:50/18 | 05:50/19 | 22:10/19 | 17:20/20 |

| RLAG | 13:50/15 | 07:00/16 | 00:50/17 | 18:40/17 | 12:10/18 | 05:50/19 | 22:00/19 | 17:20/20 |

| CAN | 13:50/15 | 06:50/16 | 01:00/17 | 18:20/17 | 12:20/18 | 05:40/19 | 17:10/20 | |

| COZ | 13:50/15 | 06:50/16 | 01:00/17 | 18:30/17 | 05:40/19 | 17:10/20 | ||

| SKAA | 13:50/15 | 07:00/16 | 00:50/17 | 18:30/17 | 12:40/18 | 05:50/19 | 22:40/19 | 17:10/20 |

| AXCA | 13:50/15 | 07:00/16 | 01:00/17 | 18:30/17 | 12:10/18 | 05:50/19 | 17:10/20 | |

Time UTC; Dates: from January 15 to 20; PX shock wave peaks

Eight pressure wave peaks were recorded at weather stations in Mexico, however, peaks 7 and 8 were no longer recorded at some stations on January 19 and 20. The pressure or shock wave was first recorded on the Mexican coast at the Ensenada (Baja California) station at 12:00, and the last station to record it was Arrecife Xcalak (Quintana Roo) at 13:50 on January 15. Weather stations recorded the hour and day for each one of the peaks, allowing the identification of the shock wave oscillatory motion back and forth (Fig. 3, 4 and 5; and Table 1). We use different scales in Figs. 3 and 4 because this way it is easier to observe perturbations that do not have the same size in each station. However, we added figures S1 and S2 (see supplementary material) with graphs with the same scale for comparison.

We constructed an isochrone diagram for the atmospheric shock wave front using several weather stations in Mexico (Fig. 6a). Figure 6a shows isochrones for the shockwave arrival time at several stations. Shock waves arrived first on the Pacific coast of Mexico, and later (+ 1.0 and 1.30 h.) reached the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean coast, respectively. Available data on atmospheric pressure allowed to estimate the average speed of the atmospheric waves, i.e., the mean sound speed in the atmosphere (Supplementary material Table S1). The highest speed, 322.79 m/s, was measured at Manzanillo (MAN station) on the Pacific coast, and the lowest, 305.08 m/s, at TUX station on the Gulf of Mexico.

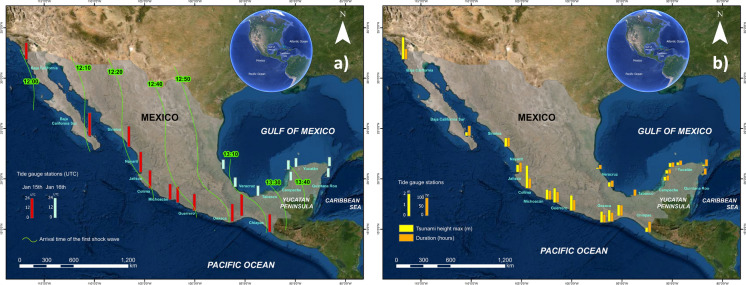

Fig. 6.

Tide gauge stations and tsunami parameters. a) Wave arrival time (24-h—UTC)—red bar for January 15th, and blue bar for January 16th. Isochrones—green lines, indicate the arrival time of shock wave 1; b) Tsunami maximum heights—yellow bar, and approximate time of recorded sea level disturbance—orange bar. Data

source: Servicio Meterológico Nacional (SMN) and Servicio Mareográfico Nacional (SMN)

Tide Gauge

The first tsunami waves recorded on the Mexican Pacific coast arrived around 12:35 on January 15, at the Lázaro Cárdenas station (Fig. 7 and Table 2). Because of the morphology of the Mexican Pacific shoreline, the arrival of the first wave occurred between 12:35 and 14:22; only La Paz-Baja California, Mazatlán and Puerto Vallarta stations registered the first wave arrival after 16:00, and in Salina Cruz, Oaxaca, at 17:30. The maximum tsunami height recorded exceeded 2 m at the Ensenada and Manzanillo tide gauge stations, while at Zihuatanejo, Puerto Ángel, Huatulco and Salina Cruz stations maximum tsunami heights were more than 1 m (Fig. 6b and Table 2). These maximum heights were observed in Ensenada and Manzanillo, and the tsunami wave arrived on January 15 at 13:29 and 17:55 h., respectively. At the other stations (LPZ, MAZ, PVAL, LCAR, ZIH, ACA, PANG, HUA, SCRZ and PCHI) the tsunami wave arrived between January 15 and 16. Another important factor is that, of the 12 stations, 8 showed heights greater than 1 m (ENS, MAN, ZIH, ACA, PANG, HUA, SCRZ and PCHI). Finally, the sea disturbance by the tsunami lasted until January 20, at the Ensenada, Zihuatanejo, Acapulco and Salina Cruz stations showing a decrease near to the 20th of January. We provide records of sea-level fluctuations for the main tide-gages on the Pacific coast Gulf of Mexico and Mexican Caribbean Sea on Figs. 6b, 7 and 8.

Fig. 7.

Pacific coast Tide gauge stations. Please see Fig. 2 for acronyms. Records for PANG are not complete. Data

source: Servicio Mareográfico Nacional (SMN)

Table 2.

Tide gauge stations and tsunami parameters. Data

source: Servicio Mareográfico Nacional (SMN)

| Station | Arrival time of the first disturbance | Tsunami height max (m) | Time tsunami height max (time/day) | Disturbance duration (hrs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pacific | ||||

| ENS | 13:29 | 2.0177 | 13:29/15 | 109.36 |

| LPZ | 18:14 | 0.334 | 20:15/15 | 102.01 |

| MAZ | 16:24 | 0.0.475 | 17:06/15 | 95.08 |

| PVAL | 16:16 | 0.678 | 18:20/15 | 99.18 |

| MAN | 14:22 | 2.047 | 17:55/15 | 102.03 |

| LCAR | 12:35 | 0.449 | 18:10/15 | 92.55 |

| ZIH | 12:56 | 1.208 | 18:29/15 | 111.1 |

| ACA | 13:32 | 1.330 | 04:31/16 | 111 |

| PANG | – | – | – | – |

| HUA | 14:03 | 1.056 | 06:04/16 | 93.18 |

| SCRZ | 17:30 | 1.555 | 19:31/15 | 110.26 |

| PCHI | 14:17 | 1.355 | 02:52/16 | 108.4 |

| Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea | ||||

| TUX | 07:47 + 1d | 0.152 | 09:39/16 | 42.23 |

| VER | 07:54 + 1d | 0.334 | 07:55/16 | 65.11 |

| SMAG | 08:11 + 1d | 0.062 | 16:19/16 | 65.49 |

| CAM | 07:24 + 1d | 0.362 | 09:16/16 | 54.11 |

| CEL | 07:33 + 1d | 0.319 | 08:12/16 | 46.28 |

| SIS | 07:20 + 1d | 0.377 | 08:14/16 | 48.25 |

| IMUJ | 07:20 + 1d | 0.151 | 13:52/16 | 69.15 |

| PMOR | 07:22 + 1d | 0.088 | 07:22/16 | 62.43 |

Time UTC; Arrival time January 15; Dates: from January 15 to 20

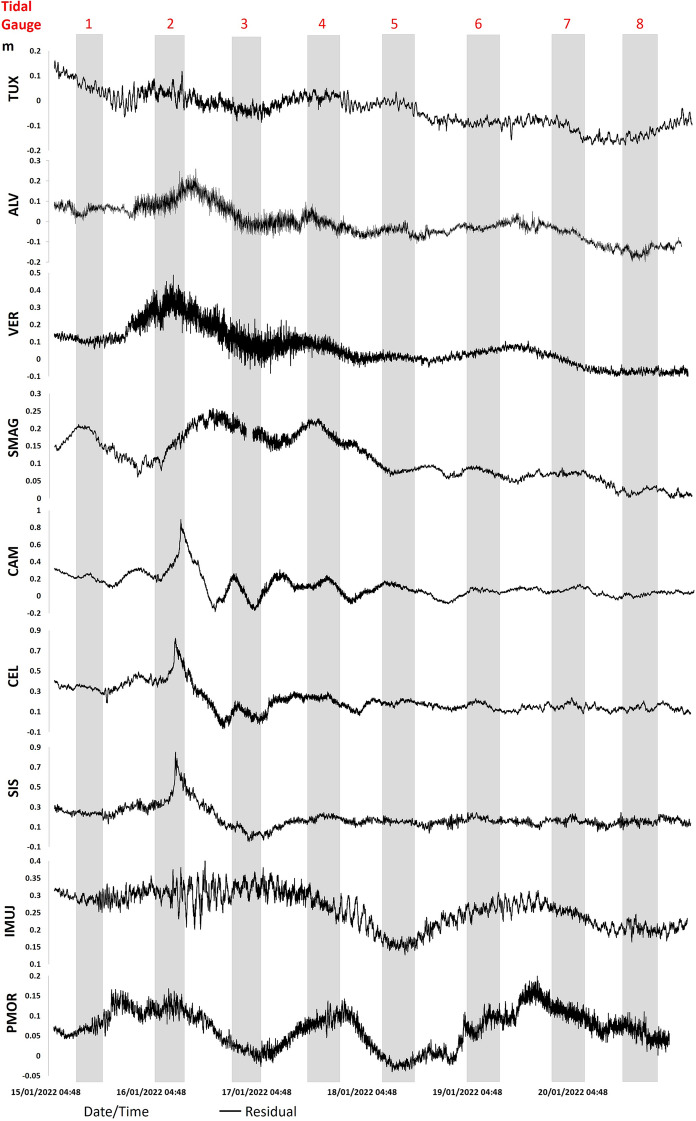

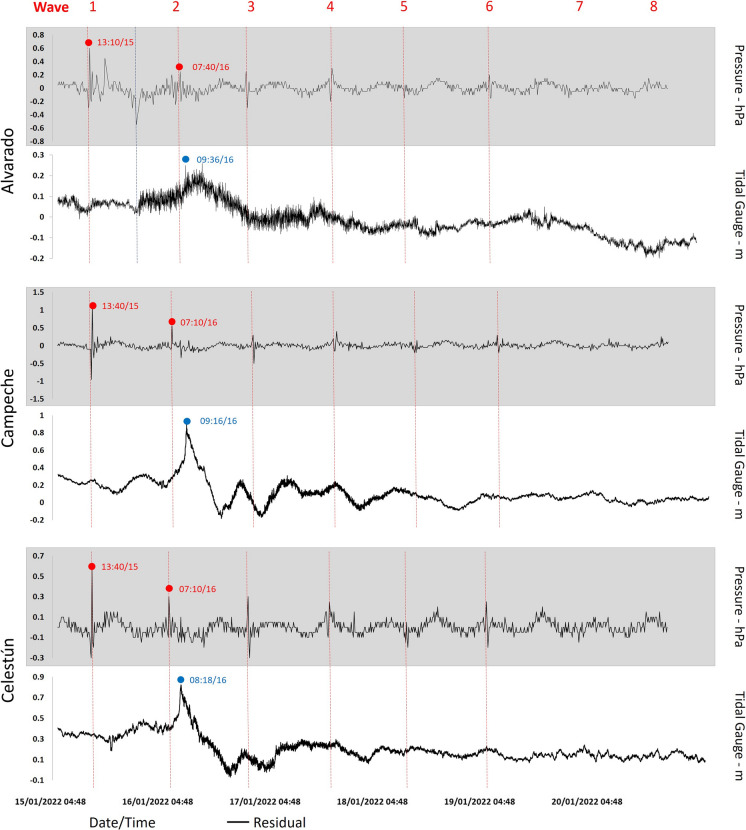

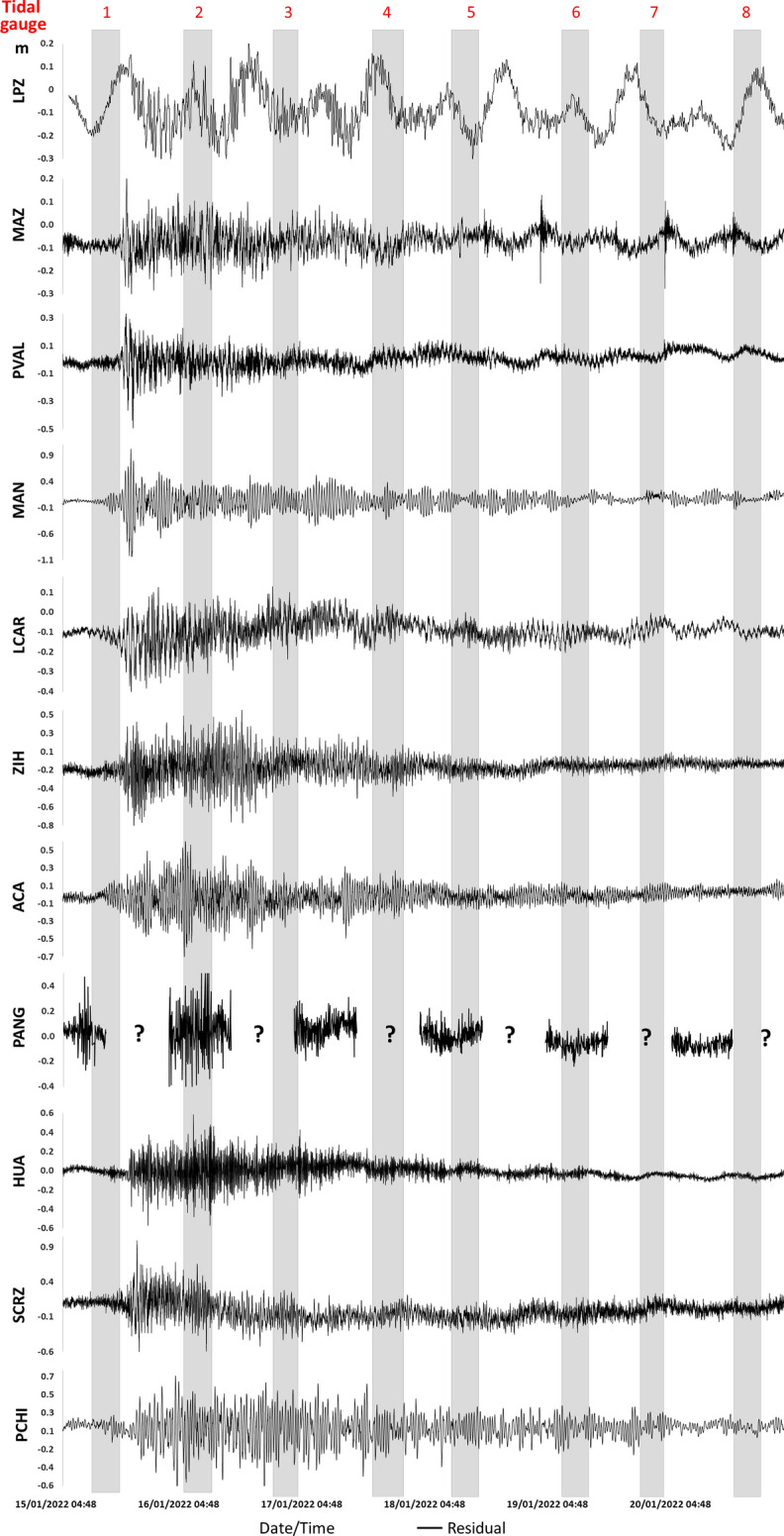

Fig. 8.

Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea Tide gauge stations. Please see Fig. 2 for acronyms. Data

source: Servicio Mareográfico Nacional (SMN)

Tide gauges also recorded disturbances in the Gulf of Mexico and the Mexican Caribbean. Sea disturbance was first observed in the Gulf of Mexico at the Tuxpan station, around 07:47, and the maximum height of the recorded wave was 0.377 m at Sisal station (Fig. 8 and Table 2).

The Gulf of Mexico tide gauge stations at Tuxpan, Veracruz, and Sánchez-Magallanes, show sea disturbances on January 16 at 07:47 h, 07:54 and 08:11, respectively. The maximum height in Tuxpan was 0.152 m at 09:39 h., in Veracruz 0.334 m at 07:55 h, and in Sanchez-Magallanes 0.062 m at 16:19 h. The duration of major sea disturbance occurred at the Isla Mujeres station (69.15 h).

On January 16 at the Caribbean Sea, initial changes in sea waves were observed at 07:20 at the Sisal station (see Fig. 8 and Table 2), and the maximum heights of 0.377 m were observed first in Sisal at 08:17 h., (Fig. 8 and Table 2).

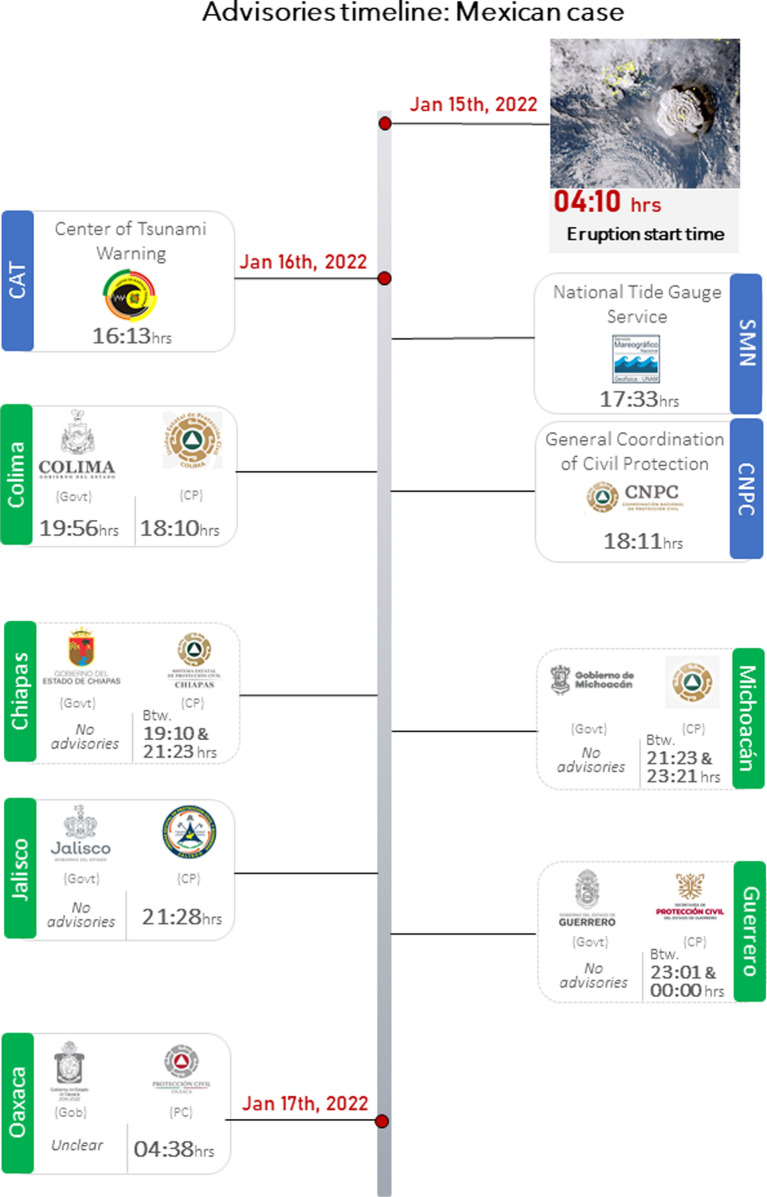

Tsunami Warning, Social Media, and People’s Response in Mexico

Tsunami warning bulletins are delivered by the Center of Tsunami Warning (CAT—Centro de Alerta de Tsunamis in Spanish, ascribed to the Mexican Navy (SEMAR). The first bulletin issued by CAT after the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano eruption on January 15, 2022 at 04:10, was on January 16, 2022, at 16:13. The first advisory by CAT was that “no significant sea level changes were expected on the Mexican coasts. However, some currents might be observed on ports of the Pacific coast”. The original source of the “earthquake” information was from the National Data Buoy Center (NOAA, 2022) and the US Tsunami Warning (NOAA/National Weather Service, 2022). Another bulletin was issued later by CAT at 17:30, addressed to all civil and military authorities. In this bulletin (number 005) by CAT a line indicates to disregard seismic data since it is a volcanic event. The update indicates that tide gauge data from ports show a decrease in elevation in all Mexican Pacific ports (Table 3), all indicate a height in the range of 0.1 m up to 0.3 m, however the time of observations is not indicated. Here the suggestions are to “take care of boats, population and activities at the ports on the coastal zone, due to potential strong currents at national ports. And to follow the instructions by local authorities from Civil Protection (Protección Civil)”. The source of information for this bulletin is from the tide gauge SINAT system (Sistema Nacional de Trámites, Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales). Tsunami bulletins by CAT are given directly to the government authorities and anybody can read them in an app “Tsunami MX” (Secretaría de Marina—CAT, 2022).

Table 3.

Tsunami warning advisories on social networks (Twitter, Facebook and Website) in Mexico

| Institutions | Dissemination medium | Issued time, UTC (January 16th) |

Link |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Jalisco (govt.) CP Jalisco |

Government website Facebook |

No warnings/advisories No warnings/advisories No warnings/advisories 21:28 21:28 |

– – – https://www.facebook.com/PCJalisco19/posts/4826040197461700 https://twitter.com/PCJalisco/status/1482464763011637255?s=20 |

|

Colima (govt.) CP Colima |

Government website Facebook |

Unknow 19:56 19:57 18:10 18:51 |

https://www.col.gob.mx/Portal/detalle_noticia/NDk3NjY = https://www.facebook.com/gobiernocolima/posts/4984934244905234 https://twitter.com/gobiernocolima/status/1482441852007575553?s=20 https://www.facebook.com/pccolima/posts/3204712863148927 https://twitter.com/PC_Colima/status/1482425328785969154?s=20 |

|

Michoacán (govt.) CP Michoacán |

Government website Facebook |

No warnings/advisories No warnings/advisories No warnings/advisories No warnings/advisories Unclear |

– – – |

|

Guerrero (govt.) CP Guerrero |

Government website Facebook |

No warnings/advisories No warnings/advisories No warnings/advisories 23:50 Unclear |

– – – |

|

Chiapas (govt.) CP Chiapas |

Government website Facebook |

No warnings/advisories No warnings/advisories No warnings/advisories 21:52 Unclear |

– – – https://www.facebook.com/pcivilchiapas.chiapas/posts/4922935257727602 |

|

Oaxaca (govt.) CP Oaxaca |

Government website Facebook |

No warnings/advisories No warnings/advisories No warnings/advisories No warnings/advisories 04:38 (+ 1d) |

– – – https://twitter.com/CEPCO_GobOax/status/1482572916143411206?s=20 |

| General Coordination of Civil Protection (CNPC) |

Official website Facebook |

No warnings/advisories 18:20 18:11 |

– |

| National Tide Gauge Service (SMN) |

Official website |

17:33 17:33 |

http://www.mareografico.unam.mx/portal/index.php?page=Estaciones https://twitter.com/SMareograficoN/status/1482405602135580680?s=20 |

| Center of Tsunami Warning (CAT) | Official website | 16:13 | https://digaohm.semar.gob.mx/cat/boletinesCAT.html |

The role of Civil Protection (CP) in Mexico is to organize and coordinate local government offices, people, actions and resources by municipalities; it is responsible for disaster relief, based on risk identification, availability of material and human resources, community preparedness and local response capacity. After the first bulletin by CAT, the Mexican CP published on its Twitter account on January 16 at 18:11, the same information by CAT, that a volcanic eruption occurred by a submarine volcano near Tonga and that based on the event characteristics and location, “NO” significant sea level changes were expected on the Mexican Coast (Protección Civil México, 2022). Most of the advisories from Mexican authorities were issued on social media networks (as Facebook pages or Twitter profiles), and some of them were published on Government’s official websites. A database with the advisories given on social media sites and official websites from local governments and civil protection authorities is shown on Table 3.

All communications and bulletins were given on Twitter or Facebook by the state offices of Protección Civil in Jalisco, Colima, Michoacán, Guerrero, Chiapas, and Oaxaca, the latest also put online a report (Table 3). Only the CP from Colima and Guerrero explicitly indicate caution and to avoid going to the sea or near the sea until further notice. It is worth mentioning that the Oaxaca office of CP published on Twitter that “it is recommended to ignore parameters of tsunamis generated by earthquake since it was a volcanic event” (Protección Civil Oax, 2022) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Timeline of Advisories dissemination time. TimeLine of Advisories dissemination time by local governments (govt.), Local Civil Protection (CP), the General Coordination of Civil Protection (CNPC), the National Tide Gauge Service (SMN) and the Center of Tsunami Warning (CAT). Dashed figures indicate that an advisory was given but the publication time is not clear (it was issued between a period of time indicated with the abbreviation “btw.”). UTC time

How did People Learn and React to this Tsunami in Mexico?

Media and social media (mainly Twitter and Facebook) reported the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano eruption and tsunami as well as the potential implications in Mexico. Most Media, social media, News on TV and online repeated what the CAT reported in their bulletins; however, some reports unfortunately minimize the hazard by comparing the tsunami heights on the Pacific coast of Mexico with “high tides'', “high sea level”, and “sea waves” (Tapia, 2022; Televisa, 2022a; etc.). Even the Civil Protection from Baja California, indicated in its Facebook site that “there were no threats to the Baja coast because the event occurred far away from this coast” (Protección Civil Baja California, 2022). However, on the Manzanillo coast, tide gauges registered sea level as high as 2 m above normal, also in Ensenada, Baja California (Fig. 7).

Overall, in Mexico tsunami evacuation warning was not delivered, instead a tsunami warning indicated caution due to higher sea waves and strong currents by CP. Colima´s CP warned people of “no normal” sea situation and clearly advised them to stay away from the sea (Olvera, 2022).

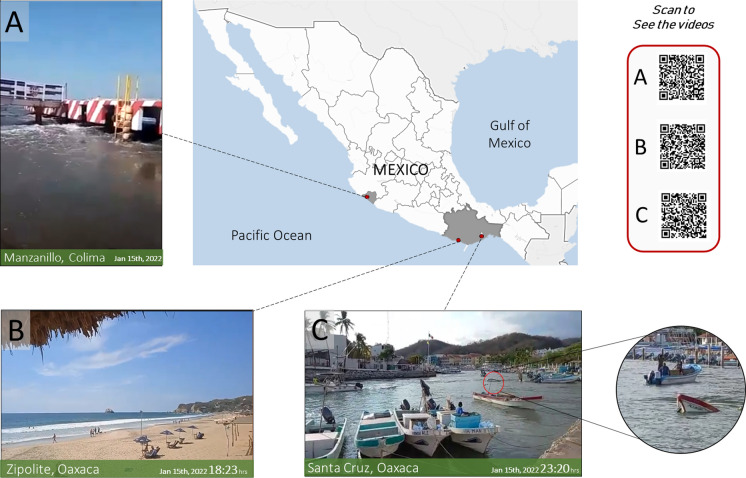

Some people went to the coast and shared videos on their personal Twitter and Facebook accounts that showed the effects on the coast at the time. In Rosarito, Baja California, despite the strong waves and tsunami alert, surfers headed to the sea (Velazquez, 2022). On the Manzanillo, Colima coast, the sea retreated, and fishes were observed onshore by January 15 at 19:12 local time (Diario Vigía, 2022). Also, strong currents hit the port of Manzanillo with no casualties since people were alerted of a potential tsunami (Radar Sonora, 2022). A video taken in Zihuatanejo at the time of the tsunami arrival about 12:56, strong currents were observed by locals (Televisa, 2022b; Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Photos and QR codes of videos of the tsunami effects on the Pacific coast

By 23:26 Civil Protection in Huatulco had no tsunami warning for locals in Huatulco, Oaxaca, according to the local Firemen (Hamblet Torrija, personal communication) and a video interview, in which the head of the local Civil Protection indicated that the sea was calm and there was no tsunami threat, encouraging tourist to stay calm (Video shared by Fireman Hamblet Torrija). However, earlier on, strong currents hit the Santa Cruz dock in Oaxaca and a boat sank at about 23:20 local time (Video shared by Fireman Hamblet Torrija; (Fig. 10)).

Discussion and Conclusion

Although far field tsunamis produced by volcanic eruptions occur seldom, the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano event reminds us of the importance of submarine volcanoes monitoring and inclusion of this type of events in the tsunami early warning systems. It is the very first eruption-generated tsunami to trigger the Pacific Ocean alert systems that have been in place since 1949.

This tsunami reached the coast of most countries around the Pacific Ocean basin, some of them had a rapid tsunami warning (e.g., Japan, US and Chile), but some didn’t such as Peru where two people died and a devastating oil spill occurred on coastal protected areas, where the fauna and vegetation have been badly damaged (DW Español, 2022).

Our results summarized here the effects of the tsunami triggered by the volcano explosion on the coast of Mexico. Direct effects of the tsunami were observed along the Pacific coast of Mexico, and the largest tsunami heights (2 m) were measured by tide gauges on the Manzanillo-Colima and Ensenada-Baja California coast, where strong currents were also observed. Although no damage was reported, the Santa Cruz dock at the Huatulco-Oaxaca coast had a boat sunk.

The effects by the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano explosion went beyond the eruption and tsunami expected locally, and the shock wave produced by the explosion caused sea perturbations that went beyond the Pacific Ocean basin, reaching the coasts on the Mexican Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico. Meteorological stations reported several peaks measured on barometers and sea perturbations at tide gauges on the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico that lasted from January 15 to the 20. However, sea perturbations observed on the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea were generated only by the shock waves, i.e., air pressure pulse observed at meteorological stations. The first shock wave is more remarkable on the Pacific, while shock wave 2 is more noticeable on the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea (Figs. 11 and 12). Another interesting feature is that at the Pacific stations shock wave 1 coincides with minor alterations in the sea (alteration is low, that is, the height of the wave is smaller). We speculate that larger sea disturbances in the Pacific coast relate with the volcano collapse producing a tsunami with a larger disturbance (larger wave height); and or it might be the effect of the sum of the two phenomena, i.e., atmospheric -air pressure pulse and volcano eruption and collapse triggered tsunami (Figs. 11 and 12).

Fig. 11.

Tide gauge and shock wave records of the Pacific coast. Data

source: Servicio Mareográfico Nacional (SMN) and Source: SMN-CONAGUA (2022)

Fig. 12.

Tide gauge and shock wave records of the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea coasts. Data

source: Servicio Mareográfico Nacional (SMN) and Source: SMN-CONAGUA (2022)

Another interesting fact is that the morphology of the coast also influenced the wave heights registered on tide gauge stations at the Pacific coast. Wave heights were higher at enclosed bays and ports (e.g., Ensenada, Manzanillo, El Veladero -Guerrero, Huatulco, Puerto Ángel y Salina Cruz).

In summary, while the Pacific coast of Mexico was hit by both waves triggered by the shock wave in the atmosphere and a tsunami wave triggered by the explosion of the Tonga volcano causing its collapse; the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea only experienced the effects of the shock wave (air pressure pulse in the atmosphere) in the sea. The passage of the waves kept the oceans altered for around 4.5 days.

Tsunami Warning

Around the globe the news of the volcano eruption spread quickly, and there was a rapid response by the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) and NOAA, IOC, ITIC, and many other scientific organizations in the world, e.g. US, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand, to name some of them. In Mexico, CAT followed initially information provided by the PTWC (Bulletin 005, 1432 UTC SAT JAN 15 2022) and NOAA, since this was an extraordinary tsunami event not produced by an earthquake, adjustments had to be made to understand the threat at several coasts around the Pacific Ocean. CAT in Mexico produces the tsunami warning bulletin, but is not responsible but reaching out communities, and this is where the Civil Protection of Mexico acts to warn and inform people of potential tsunami threats and the actions that people should take.

Although it is not our aim to assess the response by CAT nor by CP Mexico, tsunami warning in Mexico, with one exception, directed people to take caution, but did not clearly state that people must stay away from the shore. Most tsunami warnings reached communities via social media such as Twitter and Facebook. We wonder if this is the most effective way to warn coastal communities in Mexico. Fortunately, no casualties, apart from damage to boats on ports and ducks were reported.

Many lessons can be learned from this event, both scientific and social. It was devastating for the people of Tonga, a combination of volcanic eruption, ashes, and a tsunami on Tonga people, though their quick reaction and tsunami warning helped in decreasing human losses, at a time when most communications (internet, TV) failed, the radio continued warning people of the tsunami threat (Testimony by Tevita Tai Fukofuka) (Fukofuka, 2022). The people of Tonga have shown that they are resilient, despite these cascading series of events in the middle of a pandemia by COVID-19. Now that we are writing this manuscript, Tonga people are still working to recover and rise back.

We suggest that although no casualties were reported in Mexico, tsunami warning by far field tsunamis and those from non-seismic sources, i.e., triggered by landslaides and volcanic eruptions should be included, secondly, it is important to improve and to reach out people and coastal communities timely and explain the associated hazards, such as strong currents, on the coast, not only in Mexico but worldwide. This is a call to other nations to pay attention and we suggest changes in their Tsunami Warning system to include non-seismic source tsunamis such as landslides, volcanoes, “meteotsunamis” (e.g., NOAA, 2021). People should be warned to stay away from the sea till further notice is given on none further hazard. We also suggest that international efforts must be made to monitor submarine volcanoes and collaborate with the local scientists and organizations, such as Tonga, working by their side in such an effort.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Figure S1. Shock wave same scale of Pacific coast. Data source: SMN-CONAGUA (2022)

Figure S2. Shock wave same scale of Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea coast. Data source: SMN-CONAGUA (2022)

Figure S3. Tide gauge same of scale of Pacific coast. Data source: Servicio Mareográfico Nacional (SMN)

Figure S4. Tide gauge same of scale of Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea coast. Data source: Servicio Mareográfico Nacional (SMN)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Servicio Mareográfico Nacional (SMN) and Octavio Gómez Ramos for sharing detailed tide gauge data for the Pacific, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. We thank Hamblet Torija and Nésctor Corona for sharing videos of the Tonga tsunami at the Mexican coastal zone. Thanks to José A. Hernández R., Librarian at Institute of Geography (UNAM), for sharing newspaper information on the event. Thanks to scientists from all over the world, who quickly published information on social media. Ramírez-Herrera acknowledges research grants by CONACYT number 284365 and PAPIIT-UNAM IN107721.Oswaldo Coca thanks the UNAM-CONAcyT doctoral scholarship and Victor Vargas the UNAM-CONAcyT master scholarship.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to research and writing of this manuscript. MTRH worked on conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, and funding acquisition by PAPIIT-107721 and CONACYT grant number 284365; the methodology was developed by the three authors MTRH, OC, and VVE; formal analysis and investigation was performed by MTRH, OC, and VVE.

Funding

Ramírez-Herrera Acknowledges Funding by Unam- Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica (Papiit) PAPIIT-UNAM grant number IN107721; and CONACYT grant number 284365.

Declarations

Competing Interest

No competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bryant T. Tsunamis. Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Choi BH, Pelinovsky E, Kim KO, Lee JS. Simulation of the trans-oceanic tsunami propagation due to the 1983 Krakatau volcanic eruption. Natural Hazards and Earth System SciencEs. 2003;3:321–332. doi: 10.5194/nhess-3-321-2003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CNN. (2022). Perú: Oleaje anómalo afectó al litoral peruano a pesar que la Armada había descartado un tsunami en las costas del país. CNN Chile. Accessed date: January 15, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.cnnchile.com/mundo/peru-oleaje-litoral-marina-descarto-tsunami-costas_20220115/

- Cronin SJ, Brenna M, Smith IEM, Barker SJ, Tost M, Ford M, Tonga’onevai S, Kula T, Vaiomounga R. New volcanic island unveils explosive past. Eos. 2017 doi: 10.1029/2017EO076589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, S. J. (2022). Why the volcanic eruption in Tonga was so violent, and what to expect next. The Conversation. The Conversation. Accessed date: January 15, 2022 Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/why-the-volcanic-eruption-in-tonga-was-so-violent-and-what-to-expect-next-175035

- Diario Vigía. (2022). Video tomado Hoy por la mañana, el mar se está recorriendo y muchos peces se quedan a la orilla, esto en la zona de #Salahua. [Video - Facebook Watch]. Facebook. Accessed date: January 15, 2022 Retrieved from https://fb.watch/ayT1VDUa0E/

- DW Español. (2022). Gobierno de Perú pide explicaciones a Marina de Guerra. [Video]. Retrieved from YouTube Accessed date: January 18, 2022. https://youtu.be/_gHV00kOLAQ

- Fukofuka, T. T. [Tevita Tai Fukofuka] (2022). Wrote this Sunday 16 Jan 2022 the day after the explosions. It’s long but it’s for those who were fortunate enough not to be in the country and want a glimpse of what happened [Post]. Facebook. Accessed date: January 21, 2022. Retrieved from https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=7206228949417857&id=100000924717160

- Government of Tonga. (2022). First Official Update Following the Volcanic Eruption. Media Release 18th January, 2022.

- Klein, L. (2022). Volcano eruption in Tonga was a once-in-a-millennium event. New Scientist, 17 January 2022. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2304822-volcano-eruption-in-tonga-was-a-once-in-a-millennium-event/ Accessed date: January 17th, 2022.

- Maeno F, Imamura F. Tsunami generation by a rapid entrance of pyroclastic flow into the sea during the 1883 Krakatau eruption. Indonesia Journal Geophysics Research. 2011;116:B09205. doi: 10.1029/2011JB008253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai K, Muhari A, Pakoksung K, Watanabe M, Suppasri A, Arikawa T, Imamura F. Consideration of submarine landslide induced by 2018 Sulawesi earthquake and tsunami within Palu Bay. Coastal Engineering Journal. 2021;63(4):446–466. doi: 10.1080/21664250.2021.1933749. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s—NOAA/National Weather Service. (2022). U.S. Tsunami Warning System. Retrieved from https://www.tsunami.gov/

- National Tsunami Warning Center (NTWC). (2022). ITIC Tsunami Bulletin Board Tsunami Information Statement Number 1, NWS National Tsunami Warning Center Palmer AK, 300 AM PST Sat Jan 15 2022, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s—NOAA. (2021). Report and Recommendations Concerning Tsunami Science and Technology Issues for the United States. October 2021. Accessed date: January 19, 2022. Retrieved from https://sab.noaa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/TSTAP-Report_Oct2021_Final_withCoverandLetter.pdf

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s—NOAA. (2022). National Data Buoy Center. Accessed date: January 16, 2022 Retrieved from https://www.ndbc.noaa.gov/

- Nomanbhoy N, Satake K. Generation mechanism of tsunamis from the 1883 Krakatau eruption. Geophysical Research Letters. 1995;22–4:509–512. doi: 10.1029/94GL03219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noticieros Televisa. (2022a). Aumenta nivel del mar en México por erupción en Tonga—Sábados de Foro. [Video]. YouTube. Accessed date: January 15, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5W3-LzcibiY

- Noticieros Televisa. (2022b). Guerrero resiente efectos de erupción del volcán en Tonga—Las Noticias. [Video]. YouTube. Accessed date: January 18, 2022 Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZriTf-nKEA0

- Olvera, E. (2022). Tonga: Colima alerta por daños en costa tras Tsunami por erupción de volcán. Informador.Mx. Retrieved from https://www.informador.mx/mexico/TONGA-Colima-alerta-por-danos-en-costa-tras-Tsunami-por-erupcion-de-volcan-20220115-0070.html

- Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC). (2022). Tsunami Information statement 001–005, Sat Jan 15 2022, ITIC Tsunami Bulletin Board. Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, UNESCO.

- Pararas-Carayannis G. The tsunami generated from the eruption of the volcano of Santorin in the bronze age. Natural Hazards. 1992;5:115–123. doi: 10.1007/BF00127000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pelinovsky E, Choi B, Stromkov A, Didenkulova I, Kim H. Analysis of tide-gauge records of the 1883 Krakatau tsunami. In: Satake K, editor. Tsunamis: case studies and recent developments. Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Protección Civil Baja California. (2022). AVISO Importante. Derivado de la Alerta de Tsunami emitida esta mañana por la NOAA se informa que: Este fenómeno no representa un riesgo para las Costas de Baja California ya que el fenómeno de origen se encuentra muy lejos de nuestro territorio. No es necesaria ninguna evacuación. [Publicación de estado]. Facebook. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/login/?next=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2Fproteccivilbc%2Fposts%2F6892977410775863

- Protección Civil México [@CNPC_MX]. (2022). Debido a la erupción de un #volcán submarino cercano a #Tonga en el #Pacífico, el Centro de Alerta de #Tsunamis de @SEMAR_mx, informa que: Con base en las características y ubicación del evento, NO se esperan variaciones significativas en el nivel del mar en costas de #México. [Tweet]. Twitter. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/CNPC_MX/status/1482415110207545345?s=20

- Protección Civil Oax [@CEPCO_GobOax]. (2022). La #CEPCO informa: debido al evento generado por la erupción del volcán en la isla de Toga, se recomienda ignorar parámetros de tsunamis generados por sismo ya que fue un evento volcánico. El monitoreo se continúa realizando con ayuda de las estaciones mareográficas,. [Attached image]. [Tweet]. Twitter. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/CEPCO_GobOax/status/1482572916143411206?s=20

- Radar Sonara. (2022.). #NACIONAL Así en Manzanillo, Colima, con efectos de la erupción del volcán submarino en la isla de Tonga, Japón, al sureste del Océano. [Video - Facebook Watch]. Facebook. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/RadarSonoraNoticias/videos/251866520355818/?extid=NS-UNK-UNK-UNK-IOS_GK0T-GK1C

- Secretaría de Marina—CAT. (2022). Último Boletín, Centro de Alerta de Tsunamis. Retrieved from https://digaohm.semar.gob.mx/cat/centroAlertasTsunamis.html

- Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (SMN)—CONAGUA. (2022). Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, Gobierno de México, México. Retrieved from https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/es/

- Servicio Mareográfico Nacional—SMN (2022). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Geofísica, México. Retrieved from http://www.mareografico.unam.mx

- Simkin, T., & Fiske, R.S., (1983). Krakatau 1883—the volcanic eruption and its effects. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

- Taj, M. (2022). Oil Spill Triggered by Tsunami Devastates Coast of Peru. The New York Times. Accessed date: January 21, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/21/world/americas/peru-oil-spill-tonga-tsunami.html

- Tapia, M. (2022). Descartan en Baja California afectación por alerta de tsunami en EU. El Sol de México. Accessed date: January 15, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.elsoldemexico.com.mx/republica/sociedad/baja-california-descartan-afectacion-por-alerta-de-tsunami-en-eu-7735212.html

- USGS. (2022). M 5.8 Volcanic Eruption—68 km NNW of Nuku‘alofa, Tonga. USGS, Earthquake Hazard Program, Latest Earthquakes, Accessed date: January 15, 2022. Retrieved from https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us7000gc8r/executive

- Velázquez, L. [Lidy Velázquez Vlogs]. (2022). Grandes olas en Rosarito por el tsunami Tonga Surfistas salen. [Video]. YouTube. Accessed date: January 15, 2022. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/V5YtRRNHz_8

- Watkins A.B. (2022). Tonga tide gauge before it stopped reporting. January 15, 2022. Accessed date: January 15, 2022. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/windjunky/status/1482335120401248256s?s=20

- Yokoyama I. A geophysical interpretation of the 1883 Krakatau eruption. Journal Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 1981;9:359–378. doi: 10.1016/0377-0273(81)90044-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Shock wave same scale of Pacific coast. Data source: SMN-CONAGUA (2022)

Figure S2. Shock wave same scale of Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea coast. Data source: SMN-CONAGUA (2022)

Figure S3. Tide gauge same of scale of Pacific coast. Data source: Servicio Mareográfico Nacional (SMN)

Figure S4. Tide gauge same of scale of Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea coast. Data source: Servicio Mareográfico Nacional (SMN)