Abstract

Purpose

Our primary objective was to assess whether immediately undergoing a second stimulation in the same ovarian cycle (DuoStim) for advanced-maternal-age and/or poor-ovarian-reserve (AMA/POR) patients obtaining ≤ 3 blastocysts for preimplantation-genetic-testing-for-aneuploidies (PGT-A) is more efficient than the conventional-approach.

Methods

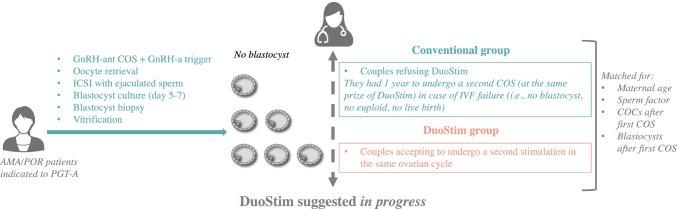

All AMA/POR patients obtaining ≤ 3 blastocysts after conventional-stimulation between 2017 and 2019 were proposed DuoStim, and 143 couples accepted (DuoStim-group) and were matched for the main confounders to 143 couples who did not accept (conventional-group). GnRH-antagonist protocol with recombinant-gonadotrophins and agonist trigger, intra-cytoplasmatic-sperm-injection (ICSI) with ejaculated sperm, PGT-A and vitrified-warmed euploid single-blastocyst-transfer(s) were performed. The primary outcome was the cumulative-live-birth-delivery-rate per intention-to-treat (CLBdR per ITT) within 1 year. If not delivering, the conventional-group had 1 year to undergo another conventional-stimulation. A cost-effectiveness analysis was also conducted.

Results

The CLBdR was 10.5% in the conventional-group after the first attempt. Only 12 of the 128 non-pregnant patients returned (165 ± 95 days later; drop-out = 116/128,90.6%), and 3 delivered. Thus, the 1-year CLBdR was 12.6% (N = 18/143). In the DuoStim-group, the CLBdR was 24.5% (N = 35/143; p = 0.01), 2 women delivered twice and 13 patients have other euploid blastocysts after a LB (0 and 2 in the conventional-group). DuoStim resulted in an incremental-cost-effectiveness-ratio of 23,303€. DuoStim was costlier and more effective in 98.7% of the 1000 pseudo-replicates generated through bootstrapping, and the cost-effectiveness acceptability curves unveiled that DuoStim would be more cost-effective than the conventional-approach at a willingness-to-pay threshold of 23,100€.

Conclusions

During PGT-A treatments in AMA/POR women, DuoStim can be suggested in progress to rescue poor blastocyst yields after conventional-stimulation. It might indeed prevent drop-out or further aging between attempts.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10815-022-02409-z.

Keywords: DuoStim, Double stimulation, Treatment personalization, Poor prognosis, Advanced maternal age

Introduction

Personalization is one of the most important keywords in modern in vitro fertilization (IVF). A personalized treatment aims at tailoring the strategies on each couple to improve treatment efficiency and efficacy. As a result of all the laboratory advances, such as intra-cytoplasmatic sperm injection (ICSI), vitrification, blastocyst culture and comprehensive chromosome testing, the concept of personalization is no more restricted to the choice of the sole controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) protocol and dosage, but it encompasses each and any decision the clinicians must take along the treatment. For instance, it is currently possible to personalize the choice for (i) pre-treatment therapies (e.g., estrogen, progesterone, oral contraceptive pill, gonadotropins releasing hormone [GnRH] antagonist), (ii) luteinizing hormone (LH) suppression regimens (antagonist protocol, agonist protocol or progesterone), (iii) additional LH activity during COS, (iv) adoption of adjuvant therapies (e.g., metformin, growth hormone, dehydroepiandrosterone, aspirin), (v) ovulation trigger, (vi) luteal phase support (e.g., different kinds and dose of progesterone, estradiol, low dose of human chorionic gonadotropin [hCG]). Clearly, also ICSI, vitrification, extended culture, and preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) themselves represent relevant tools that might be adopted or not, thereby personalizing each treatment. This is mirrored even in the Poseidon panel’s definition of a successful COS, i.e., “retrieve the number of oocytes necessary to obtain at least one euploid embryo for transfer in each single patient” [1–5]. These experts were the first to emphasize that the number of oocytes retrieved and of blastocysts obtained themselves do not define a successful COS if not adjusted for maternal age and its impact on reproduction (lower blastulation and euploidy rates) [6, 7].

More recently, then, the knowledge of the extreme dynamism of folliculogenesis opened also to the implementation of novel unconventional COS protocols for specific sub-groups of patients. These protocols are mainly three: (i) the random start protocol in oncologic patients, (ii) the luteal phase stimulation protocol in poor responders, and (iii) the double stimulation in one ovarian cycle (DuoStim) in poor prognosis patients (i.e., expected low response to COS and/or advanced maternal age) and/or in patients with limited time available [8]. Overall, these protocols represent the greatest level of personalization in modern IVF. Indeed, across the last decade independent groups adopted them in different populations of patients always reporting reassuring evidence [9, 10]. At first, double stimulation in a single ovarian cycle has been theorized in humans and published in two proof-of-concept papers [11, 12]. Then, evidence has been produced to highlight the equal developmental and reproductive competence of the oocytes (and then the embryos) collected after the first versus the second stimulation [13, 14]. At last, DuoStim has been tested as an approach to decrease the drop-out rate and improve IVF efficacy in challenging patients, such as the ones fulfilling the Bologna criteria [15].

All these promising results paved the way to this study, where a second stimulation in the same ovarian cycle was suggested in progress, based on the number of blastocysts obtained after the first retrieval. This new strategy to suggest DuoStim was conceived in view of a higher patient-centeredness and a full personalization of the IVF treatment [16]. All women accepting to start immediately a second stimulation were matched with similar couples, who instead preferred completing the ongoing treatment before undertaking other steps. The primary outcome was the cumulative-live-birth-delivery-rate per intention to treat (CLBdR per ITT) up to two ovarian stimulations within 1 year. Also, a cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted as main secondary outcome.

Material and methods

Study design

This is a proof-of-concept matched case–control study conducted between 2017 and 2019 at a private IVF clinic in Rome (Clinica Valle Giulia, GeneraLife IVF). The patients included fulfilled the following criteria: (i) they had an indication to PGT-A, (ii) they underwent a conventional-stimulation based on a GnRH-antagonist protocol with recombinant-gonadotrophins and agonist trigger, (iii) they obtained from 0 to 3 blastocysts in day 5–7 after ICSI with ejaculated sperm.

All patients underwent an extensive counseling based on their poor prognosis. In fact, even if obtaining 3 blastocysts, their mean maternal age of 41 years exposed them to high risk of all embryos being diagnosed aneuploid. During counseling, two alternatives were therefore proposed to improve their prognosis while complying with the local regulation (Italian Law 40/2004): (i) to complete the current treatment (i.e., wait for the diagnosis and transfer) and, in case of a negative outcome, subsequently evaluate whether to undergo a second attempt with the same protocol, or (ii) to start immediately a second stimulation in the same ovarian cycle without waiting further. Both the second attempt with a conventional approach and the second stimulation in the same ovarian cycle were provided with an equal discount (see the “Costs” section). Clearly, also alternative options like a treatment with donor oocytes or adoption were suggested but declined by the couples. Institutional Review Board approval for this study was obtained from Clinica Valle Giulia.

The 143 couples who accepted to undergo the second stimulation in the same ovarian cycle were matched for maternal age, sperm factor, cumulus-oocyte-complexes and blastocysts obtained after the first stimulation to 143 couples who did not accept in the same study period (Table 1 describes the study population). If several matching couples were identified, we chose the ones with the closest oocyte retrieval date. The matching variables were chosen because of their well-known association with our primary outcome under investigation [7, 17–24], i.e., CLBdR [25, 26] per ITT up to two ovarian stimulations. If not delivering, the patients in the control group had 1 year to return for a second conventional-stimulation (Fig. 1). All treatments were completed at the time of writing (i.e., no transferable blastocyst was obtained, a live birth [LB] was achieved or no euploid blastocyst were left to transfer). We also reported the drop-out rate as the number of women who did not return for a second stimulation in 1-year divided by the number of women who did not deliver after the first conventional approach. Among the women who instead returned for a second attempt, we reported also the days elapsed between the two retrievals. At last, we reported the number of patients delivering more than one baby in the two groups and the number of couples who still had euploid blastocysts to transfer at the time of writing. A sub-analysis was conducted to report the CLBdR and the drop-out rate among patients clustered according to the number of blastocysts obtained after the first retrieval in the two study groups, (i.e., 0, 1, or 2–3). In conclusion, a cost-effectiveness analysis was also conducted.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 286 patients included in the study

| Conventional approach N = 143 | DuoStim approach N = 143 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, mean ± SD | 41.0 ± 2.9 yr | Matching variable | |

| Sperm Factor | Matching variable | ||

| Normozoospermic, N, % | 176, 61.5% | ||

| 1–2 defects, N, % | 70, 24.5% | ||

| OAT, N, % | 40, 14.0% | ||

| Main cause of infertility | 0.8 | ||

| Idiopathic, N, % | 112, 78.3% | 109, 76.2% | |

| Endometriosis, N, % | 6, 4.2% | 10, 7.0% | |

| Tubal factor, N, % | 6, 4.2% | 5, 3.5% | |

| Male factor, N, % | 19, 13.3% | 19, 13.3% | |

| Previous live births | 0.2 | ||

| Yes, N, % | 106, 74.1% | 95, 66.4% | |

| Not, N, % | 37, 25.9% | 48, 33.6% | |

| Years of infertility, mean ± SD | 3.0 ± 1.9 yr | 2.9 ± 1.6 yr | 0.9 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 21.8 ± 2.7 | 21.6 ± 2.0 | 0.6 |

| FSH, mean ± SD | 11.2 ± 6.4 IU/l | 9.6 ± 4.7 IU/l | 0.2 |

| AMH, mean ± SD | 1.2 ± 1.5 ng/ml | 1.1 ± 0.8 ng/ml | 0.8 |

| COCs retrieved, mean ± SD | 4.9 ± 3.1 | Matching variable | |

| Blastocysts obtained, mean ± SD | 0.8 ± 0.9 | Matching variable | |

Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests were conducted to assess statistically significant differences among categorical variables. Mann–Whitney U tests were conducted to assess statistically significant differences among continuous variables

OAT, oligoasthenoteratozoospermic; BMI, body mass index; COC, cumulus oocyte complex

Fig. 1.

Study design. Advanced maternal age (AMA) and/or poor ovarian reserve (POR) patients indicated to preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies (PGT-A) underwent GnRH-antagonist controlled ovarian stimulation COS with GnRH-agonist trigger, oocyte retrieval, ICSI with ejaculated sperm, blastocyst culture to day 5–7, blastocyst biopsy and vitrification. In day 5–7, all patients obtaining 0–3 blastocysts were suggested undergoing a second stimulation in the same ovarian cycle (DuoStim). Some patients accepted and represented the DuoStim group (orange). Several other patients instead preferred completing the cycle and, eventually had 1 year to consider a second conventional COS (at the same prize of DuoStim) in case of IVF failure (no blastocyst, no euploid, no live birth) (Conventional group). The 143 patients in the DuoStim groups were matched for maternal age, sperm factor, number of cumulus-oocyte-complexes (COCs) retrieved, and number of blastocysts obtained after the first COS to 143 patients in the Conventional group

IVF procedure

Luteal estradiol priming (4 mg/day of estradiol valerate; Progynova, Bayer) was performed in the previous menstrual cycle in both groups to better synchronize the cohort of growing follicles and improve the ovarian response to stimulation, thereby potentially reducing the risk of cancellation [27, 28]. After the scan and basal assessment of the ovaries, ovarian stimulation was started on day 2 of the menstrual cycle with a fixed dose of recombinant follicle stimulation hormone and recombinant luteinizing hormone (300 IU/day of Gonal-F, Merck KGaA or Puregon, MSD plus 150 IU/day of Luveris, Merck KGaA) for 4 days. Follicular growth was monitored on day 5 and then every 2–3 days. The gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonist (Cetrorelix, Cetrotide, Merck KGaA or Ganirelix, Orgalutran, MSD) was administered daily after the identification of a leading follicle with a diameter 13–14 mm and until the day of ovulation trigger. When at least one follicle reached 17–18 mm in diameter, final maturation of oocytes was induced with agonist trigger through a single subcutaneous bolus of buserelin at the dose of 0.5 ml (Suprefact 5.5 ml; Hoechst Marion Roussel, Germany) to reduce the time of luteolysis [29]. Oocyte retrieval was performed after 35 h, using a standard procedure. All follicles larger than 11–12 mm were punctured. In patients undergoing Duostim, 5–7 days after the first retrieval, second stimulation was initiated with the same protocol and daily dose, regardless of the number of antral follicles visible with the ultrasound scan in the anovulatory wave.

All cycles entailed ICSI with ejaculated sperm [18, 30], blastocyst culture conducted in single drops and in a controlled humidified atmosphere (37 °C, 6% CO2 and 5% O2), trophectoderm biopsy conducted without day3 hatching on all fully-expanded blastocysts, and vitrified-warmed euploid single embryo transfer(s) [31–33]. A freeze-all approach was adopted, and the biopsies collected after both stimulations were sent to an external laboratory (Igenomix, Italy) for aneuploidy testing. Only comprehensive chromosome testing techniques were adopted [34–36]. We did not report “embryos with a PGT-A result falling in the mosaic range” [37] since the risk for false positive calls [38–40] is deemed too high at present according to evidence produced from our clinic as well as from other groups [41–43]. Embryo transfer was performed in a following cycle with either a modified-natural or artificial protocol [20, 44].

Costs

First oocyte retrieval cost 4500 Euros and included ovulation monitoring, day hospital surgery, anesthesia, ICSI, embryo culture and vitrification. Second retrievals instead cost 2800 Euros in both study groups (≈40% discount). PGT-A was charged 1500 Euros for 1–2 blastocysts, 2200 Euros for 3–4 blastocysts, 3000 Euros for 5–6 blastocysts and 350 Euros for each additional blastocyst after the sixth, and included biopsy. In the DuoStim group, the PGT-A cost was calculated cumulating the blastocysts obtained from both retrievals. First vitrified-warmed euploid single blastocyst transfers were charged 500 Euros. Each additional transfer was charged 1000 Euros. We calculated the average expense for each procedure and for the whole treatment per patient in both groups. At last, we calculated the overall expense in the two groups, as well as the average cost per “patient with at least 1 LB”. Based on these data, we calculated the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) as [(Total cost of DuoStim – Total cost of the conventional approach) / (CLBdR with DuoStim – CLBdR with the conventional approach)].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and range. Shapiro–Wilk tests were conducted to assess a normal distribution of the data, and Mann–Whitney U tests were adopted to assess any statistically significant difference between continuous non-parametric data. Categorical variables were reported as rates with absolute numbers and 95% confidence interval (CI). Chi-squared of Fisher’s exact tests were conducted to assess statistically significant differences between categorical variables. A multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for the matching criteria was conducted to assess the association of the two strategies with the CLBdR from up to two stimulations in one year. The software SPSS (IBM, USA) was adopted for statistics. The level of significance was set as p-value < 0.05.

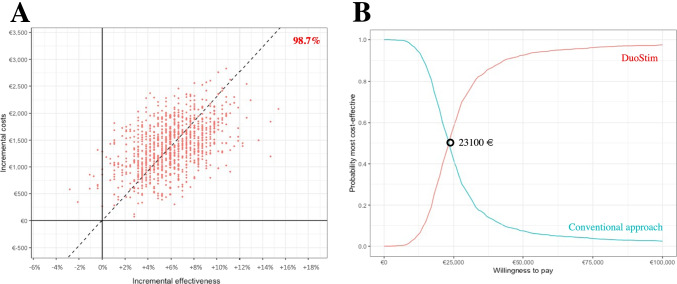

Cost-effectiveness analysis

A probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was conducted, which involved the generation of 1000 pseudo-replicates through the bootstrap method. Based on these pseudo-replicates, we drew a cost-effectiveness plane (C-E plane), that outline the incremental cost (mean differences in cost) per patient on the y-axis, and the incremental effectiveness (difference in CLBdR) on the x-axis. To summarize the information on uncertainty in the cost-effectiveness estimates, cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEAC) were also generated, expressed as the probability that one strategy is more cost-effective than the other in relation to willingness-to-pay thresholds. The software R version 4.1.1 was used to conduct these analyses.

Results

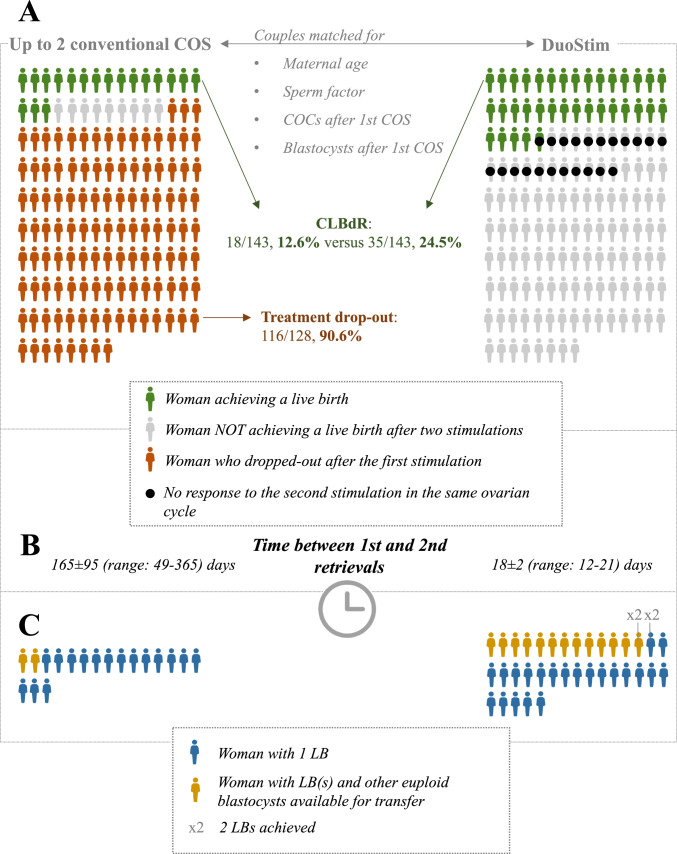

Among the 286 couples included (41.0 ± 2.9 yr; 4.9 ± 3.1 cumulus-oocyte complexes and 0.8 ± 0.9 blastocysts), 126 (63 per group), 98 (49 per group), 62 (31 per group) obtained 0, 1, and 2–3 blastocysts after the first stimulation, respectively. Supplementary Fig. 1 comprehensively displays the data for each matched couple for the first stimulation and the second stimulation eventually performed in terms of (i) number of COCs, (ii) aneuploid blastocysts obtained, (iii) euploid blastocysts obtained that did not implant after transfer, (iv) euploid blastocysts obtained that implanted after transfer, and (v) euploid blastocysts obtained that are still available for transfer. Supplementary Fig. 1 reports also the couples that dropped out in the conventional approach group, and the couples that did not respond to the second stimulation in the same ovarian cycle in the DuoStim group. Figure 2, instead, represents a summary of these data. In detail, the CLBdR in the conventional approach group was 10.5% after the first attempt (N = 15/143, 95%CI 6–17%). Among the 128 non-pregnant patients, only 12 returned within 1-year (165 ± 95 days later, range: 49–365), therefore involving a 90.6% drop-out rate (N = 116/128, 95%CI 84–95%). Three of the 12 couples returning for a second attempt delivered for a final 12.6% CLBdR from up to two stimulations (N = 18/143, 95%CI 8–19%). In the DuoStim group, 15.4% of the patients did not respond to the second stimulation in the same ovarian cycle (N = 22/143) and the final CLBdR from two stimulations was 24.5% (N = 35/143, 95%CI 18–33%; p-value versus the conventional approach group = 0.01). The univariate odds-ratio of obtaining a LB in the DuoStim group versus the standard approach group was 2.3, 95%CI 1.2–4.2, p-value = 0.01. Of note, 2 and 13 couples who already delivered in the conventional approach and DuoStim group, respectively, have other euploid blastocysts available for transfer. Two patients delivered 2 babies after DuoStim, none in the conventional approach group (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 1). Supplementary Fig. 2 represents a sub-analysis according to the number of blastocysts obtained after the first stimulation. Among patients obtaining no blastocyst (mean maternal age: 42 yr), the CLBdR from up to two stimulations was 0% (N = 0/63) and 10% (N = 6/63) in the conventional approach and DuoStim group, respectively. In the former group, in fact, the drop-out was 98% (N = 62/63). Among patients obtaining 1 blastocyst (mean maternal age: 40 yr), the CLBdR from up to two stimulations was 24% (N = 12/49) and 31% (N = 15/49) in the conventional approach and DuoStim group, respectively. In the former group, in fact, the drop-out was 78% (N = 31/40). Among patients obtaining 2–3 blastocysts (mean maternal age: 41 yr), the CLBdR from up to two stimulations was 19% (N = 6/31) and 45% (N = 14/31) in the conventional approach and DuoStim group, respectively. In the former group, in fact, the drop-out was 92% (N = 23/25). The multivariate odds-ratio of obtaining a live birth in the DuoStim group versus the standard approach group adjusted for all matching criteria was 2.8, 95%CI:1.4–5.6, p-value < 0.01.

Fig. 2.

Summary of the main outcomes in the conventional approach and DuoStim study matched* groups. The figure summarizes (A) the cumulative live birth delivery rate (CLBdR) from up to two stimulations in one year in the two matched study groups, and the treatment drop-out rate between the 1st and 2nd controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) in the conventional approach group, (B) the time elapsed between the two retrievals among women who completed both stimulations in the two groups, and (C) the number of women delivering two babies and/or having other euploid blastocysts available for transfer. *The couples were matched for maternal age, sperm factor, number of cumulus oocytes complexes (COCs) and blastocysts obtained after the first COS

Table 2 shows the expenses in the two groups. As expected, they were lower in the conventional approach with respect to DuoStim and resulted in an average treatment cost of 5916 ± 1846 Euros versus 8686 ± 1966 Euros, respectively (p < 0.01). Nevertheless, when the total expenses in the two groups (846,000 Euros and 1,242,150 Euros, respectively) were divided by the number of patients with ≥ 1 LB (N = 18 and N = 35, respectively), the conventional approach resulted in a higher average expense (47,000 Euros versus 35,490 Euros; p < 0.01). Based on these data, we have calculated the ICER of DuoStim versus the conventional approach, which resulted in 23,303 additional € invested to achieve a 11.9%-higher CLBdR. The C-E plane built on 1000 bootstrapped pseudo-replicates unveiled that in 98.7% of the cases DuoStim would be costlier and more effective than the conventional approach (Fig. 3A). The CEAC showed that beyond a 23,100 € willingness-to-pay threshold DuoStim becomes more cost-effective than the conventional approach (Fig. 3B). Clearly, these results depend on the 90.6% treatment discontinuation rate among non-pregnant women in the conventional approach group, which involved a lower overall expense in this group, but also a lower CLBdR per ITT, thereby favoring DuoStim.

Table 2.

Costs in the two study groups (in Euros). Costs are expressed as mean per intention to treat in 1 year ± SD, min–max

| Conventional approach | DuoStim approach | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First OPU | 4500 ± 0 | 4500 ± 0 | |

| Second OPU |

235 ± 779 (0–2800) |

2369 ± 1014 (0–2800) |

p < 0.01 |

| First PGT-A analysis |

864 ± 780 (0–2200) |

- | |

| Second PGT-A analysis |

104 ± 447 (0–3000) |

- | |

| Overall PGT-A analysis |

968 ± 970 (0–4500) |

1478 ± 944 (0–3500) |

p < 0.01 |

| Vitrified-warmed transfer(s) |

213 ± 454 (0–2500) |

339 ± 580 (0–2500) |

p = 0.04 |

| Total treatment cost per patient |

5916 ± 1846 (4500–14300) |

8686 ± 1966 (4500–13050) |

p < 0.01 |

| Total cost | 846000 | 1242150 | |

| Patients with ≥ 1 LB | 18 | 35 | |

| Total cost per “patient with ≥ 1 LB” | 47000 | 35490 | |

| 1-year CLBdR | 12.6% | 24.5% | p = 0.01 |

| ICER | 23303 |

OPU, oocyte pick-up; PGT-A, preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies; CLBdR, cumulative live birth delivery rate; ICER, incremental cost effectiveness ratio calculated as [(total cost of Duostim – total cost of the conventional approach) / (CLBdR with DuoStim – CLBdR with conventional approach)]

Fig. 3.

Cost-effectiveness (C–E) analysis. (A) and (B) plane built on 1000 pseudo-replicates generated through the bootstrap method. The y-axis reports incremental cost (mean difference of cost in the DuoStim versus conventional approach) and the x-axis reports the incremental effectiveness (mean difference in the cumulative live birth delivery rate per intention to treat in the DuoStim versus conventional approach). In 98.7% of cases DuoStim would be costlier and more effective than the conventional approach. (B) C–E acceptability curves (CEAC). The y-axis reports the probability that one strategy is more cost-effective than the other (DuoStim in red and conventional approach in blue) and the x-axis reports the willingness-to-pay thresholds. Beyond a willingness-to-pay threshold of 23,100 € DuoStim is more cost-effective than the conventional approach

Discussion

The personalization of IVF treatment is key in a modern clinic to maximize both efficacy and efficiency. In this context, we should move from evaluating each cycle per se to a more comprehensive vision of the whole treatment. From this perspective, efficiency involves even reducing the burden represented by complications, such as absence of transferable embryos, implantation failure, miscarriage and increasing time loss. In fact, all these factors might in turn increase patient drop-out [16]. Here we adopted a clinical scheme that encompassing blastocyst culture, aneuploidy testing and cycle segmentation in AMA patients left room for them to choose whether starting a second stimulation in the same ovarian cycle or not.

Previous internal evidence highlighted that a second stimulation in the same ovarian cycle is effective when addressed to candidate patients based on well-defined criteria (antimüllerian hormone [AMH] < 1.5 ng/ml, antral follicle count [AFC] < 6 follicles, and/or < 5 oocytes, candidate to PGT-A) [12, 13, 15]. Grounded on this, we gradually started re-thinking DuoStim as a strategy that can be suggested in progress (i) to prevent treatment drop-out in patients obtaining no blastocyst and with limited residual time to conceive with their own eggs (mean age 42 yr), or (ii) to improve the prognosis of AMA patients obtaining 1–3 blastocysts but with very high risk they would be aneuploid. In fact, several groups across the literature suggest that, although low, the chance to conceive keeps increasing with increasing cumulative number of oocytes retrieved, also in AMA [21, 45–47]. Moreover, treatment drop-out, especially in this category of patients, is very high and the reason is not just their prognosis, but includes also financial, psychological and logistic aspects [48]. Starting immediately with a second stimulation at the same cost of any second attempt at our center (i) improved the CLBdR in 143 couples (2–3 times higher), (ii) prevented their drop-out (90.6% in matched control group), (iii) led them retrieving a second cohort of oocytes in about 18 days (rather than about 165 days in the control), (iv) resulted in 13 patients having other transferable blastocysts after delivering a baby, (v) resulted in 2 patients delivering twice, and (vi) resulted in a lower cost per “patient with at least one LB” with an ICER of 23,303€. Based on these data, DuoStim can be conceived as a strategy in line with the “one-and-done” concept (i.e., the completion of an average-sized family [≥ 2 LBs] after a single complete IVF cycle) [49], whose cost is reasonably higher than the conventional-approach.

In summary, in freeze-all cycles, DuoStim represents a sound alternative to oocyte accumulation [50], which can be even proposed in progress. Of note, the choice to start immediately a second stimulation shall follow a careful counseling focused on patients’ chance to find at least one euploid embryo on account of their age and of the number of blastocysts obtained after conventional stimulation.

The sample size in this study was limited to assess the real prognostic value of the number of blastocysts obtained after conventional stimulation on the outcome of the second treatment, yet an increasing trend was shown. Future randomized-controlled-trials including cost-effectiveness analyses are required to confirm this proof-of-concept study in a larger population of patients. In particular, 75% of the patients recruited here were older than 39 yr and 44% obtained no blastocyst after the first stimulation. Therefore, studies among younger women and/or more women obtaining ≥ 1 blastocyst are advisable to outline adequate cut-off values for the application of this strategy. At present, our data shall be carefully contextualized: they apply to a population of AMA/POR patients undergoing PGT-A at a private IVF center, whose peculiar policy and costs per procedure have been clearly detailed in the Material and Methods and Results sections. Our evidence must be confirmed at other centers, with different settings and costs before they can be generalized.

In conclusion, the novelty of this study was suggesting DuoStim in progress after conventional stimulation, as a valuable strategy in view of an increasing patient-centeredness and full-personalization of IVF treatments. This is essential especially in a scenario that comprehensively defines an IVF treatment as the sum of all cycles and procedures a couple must go through in the attempt of obtaining a LB. Clearly, an extensive counseling on the pros and cons of DuoStim is crucial, but this unconventional ovarian stimulation protocol, even when suggested in progress, holds potential to improving treatment success in AMA/POR patients with scarce blastocyst yield and willing to conceive with their own oocytes.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Figure 1. Results from the couples in the conventional approach (COS 1 + COS 2) group and their matched* couples in the DuoStim (Stim I + Stim II in the same ovarian cycle) group. Each circle represents a cumulus oocyte complex (COC) retrieved. If green, it developed as an euploid blastocyst and resulted in a live birth after transfer; if purple, it developed as an euploid blastocyst but did NOT result in a live birth after transfer; if orange, it developed as an euploid blastocyst which is still available for transfer; if red, it developed as an aneuploid blastocyst; if grey, it did not reach the blastocyst stage. In the conventional approach group, we highlighted the couples who dropped-out from the treatment after a failed first attempt. In the DuoStim group, we highlighted the patients who did not respond to the second stimulation in the same ovarian cycle. *The couples were matched for maternal age, sperm factor, number of cumulus oocytes complexes (COCs) and blastocysts obtained after the first COS.

Supplementary file1 (PDF 264 kb)

Supplementary Figure 2. Sub-analysis of the cumulative live birth delivery rates (CLBdR) in the conventional approach and the matched* DuoStim groups according to the number of blastocysts obtained after the first controlled ovarian stimulation (COS). The treatment drop-out rate among couples who failed the first attempt has been reported also for the former group. Below each cluster we reported also the mean maternal age. *Besides maternal age and number of blastocysts obtained after the first COS, the couples were matched also for sperm factor and number of cumulus oocyte complexes retrieved after first COS.

Supplementary file2 (PDF 77 kb)

Author contribution

AV, DC, LR and FMU designed the study. AV, SC, CA, MG, and FMU recruited the patients. AV and DC analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. DC, VC and ADA designed and performed the cost-effectiveness analyses. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional Review Board approval for this study was obtained from Clinica Valle Giulia.

Consent for publication

All authors consented to the publication of the present study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alviggi C, Andersen CY, Buehler K, Conforti A, De Placido G, Esteves SC, et al. Poseidon Group. A new more detailed stratification of low responders to ovarian stimulation: from a poor ovarian response to a low prognosis concept. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(6):1452–3. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.02.005. PubMed PMID: 26921622. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Esteves SC, Alviggi C, Humaidan P, Fischer R, Andersen CY, Conforti A, et al. The POSEIDON criteria and its measure of success through the eyes of clinicians and embryologists. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:814. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00814.PubMedPMID:31824427;PubMedCentralPMCID:PMCPMC6880663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conforti A, Esteves SC, Cimadomo D, Vaiarelli A, Di Rella F, Ubaldi FM, et al. Management of women with an unexpected low ovarian response to gonadotropin. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:387. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00387.PubMedPMID:31316461;PubMedCentralPMCID:PMCPMC6610322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esteves SC, Yarali H, Ubaldi FM, Carvalho JF, Bento FC, Vaiarelli A, et al. Validation of ART Calculator for Predicting the Number of Metaphase II Oocytes Required for Obtaining at Least One Euploid Blastocyst for Transfer in Couples Undergoing in vitro Fertilization/Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:917. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00917.PubMedPMID:32038484;PubMedCentralPMCID:PMCPMC6992582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaiarelli A, Cimadomo D, Ubaldi N, Rienzi L, Ubaldi FM. What is new in the management of poor ovarian response in IVF? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;30(3):155–162. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ubaldi FM, Cimadomo D, Vaiarelli A, Fabozzi G, Venturella R, Maggiulli R, et al. Advanced Maternal Age in IVF: Still a Challenge? The Present and the Future of Its Treatment. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:94. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00094.PubMedPMID:30842755;PubMedCentralPMCID:PMCPMC6391863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cimadomo D, Fabozzi G, Vaiarelli A, Ubaldi N, Ubaldi FM, Rienzi L. Impact of Maternal Age on Oocyte and Embryo Competence. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:327. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00327.PubMedPMID:30008696;PubMedCentralPMCID:PMCPMC6033961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venturella R, Vaiarelli A, Lico D, Ubaldi FM, Zullo F, C DIC. A modern approach to the management of candidates for assisted reproductive technology procedures. Minerva Ginecol. 2018;70(1):69–83. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4784.17.04138-7. PubMed PMID: 28895679. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Vaiarelli A, Cimadomo D, Petriglia C, Conforti A, Alviggi C, Ubaldi N, et al. DuoStim - a reproducible strategy to obtain more oocytes and competent embryos in a short time-frame aimed at fertility preservation and IVF purposes. A systematic review. Ups J Med Sci. 2020:1–10. 10.1080/03009734.2020.1734694. PubMed PMID: 32338123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Sfakianoudis K, Pantos K, Grigoriadis S, Rapani A, Maziotis E, Tsioulou P, et al. What is the true place of a double stimulation and double oocyte retrieval in the same cycle for patients diagnosed with poor ovarian reserve? A systematic review including a meta-analytical approach. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37(1):181–204. doi: 10.1007/s10815-019-01638-z.PubMedPMID:31797242;PubMedCentralPMCID:PMCPMC7000611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuang Y, Chen Q, Hong Q, Lyu Q, Ai A, Fu Y, et al. Double stimulations during the follicular and luteal phases of poor responders in IVF/ICSI programmes (Shanghai protocol) Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;29(6):684–691. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ubaldi FM, Capalbo A, Vaiarelli A, Cimadomo D, Colamaria S, Alviggi C, et al. Follicular versus luteal phase ovarian stimulation during the same menstrual cycle (DuoStim) in a reduced ovarian reserve population results in a similar euploid blastocyst formation rate: new insight in ovarian reserve exploitation. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(6):1488–95 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.03.002. PubMed PMID: 27020168. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Cimadomo D, Vaiarelli A, Colamaria S, Trabucco E, Alviggi C, Venturella R, et al. Luteal phase anovulatory follicles result in the production of competent oocytes: intra-patient paired case-control study comparing follicular versus luteal phase stimulations in the same ovarian cycle. Hum Reprod. 2018 doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaiarelli A, Cimadomo D, Alviggi E, Sansone A, Trabucco E, Dusi L, et al. The euploid blastocysts obtained after luteal phase stimulation show the same clinical, obstetric and perinatal outcomes as follicular phase stimulation-derived ones: a multicenter study. Hum Reprod. 2020;35(11):2598–2608. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaiarelli A, Cimadomo D, Conforti A, Schimberni M, Giuliani M, D'Alessandro P, et al. Luteal phase after conventional stimulation in the same ovarian cycle might improve the management of poor responder patients fulfilling the Bologna criteria: a case series. Fertil Steril. 2020;113(1):121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rienzi L, Cimadomo D, Vaiarelli A, Gennarelli G, Holte J, Livi C, et al. Measuring success in IVF is a complex multidisciplinary task: time for a consensus? Reprod Biomed Online. 2021. Epub 2021/09/09. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2021.08.012. PubMed PMID: 34493463. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Mazzilli R, Cimadomo D, Vaiarelli A, Capalbo A, Dovere L, Alviggi E, et al. Effect of the male factor on the clinical outcome of intracytoplasmic sperm injection combined with preimplantation aneuploidy testing: observational longitudinal cohort study of 1,219 consecutive cycles. Fertil Steril. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maggiulli R, Cimadomo D, Fabozzi G, Papini L, Dovere L, Ubaldi FM, et al. The effect of ICSI-related procedural timings and operators on the outcome. Hum Reprod. 2020;35(1):32–43. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cimadomo D, Vaiarelli A, Petriglia C, Fabozzi G, Ferrero S, Schimberni M, et al. Oocyte competence is independent of the ovulation trigger adopted: a large observational study in a setting that entails vitrified-warmed single euploid blastocyst transfer. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10815-021-02124-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cimadomo D, Capalbo A, Dovere L, Tacconi L, Soscia D, Giancani A, et al. Leave the past behind: women's reproductive history shows no association with blastocysts' euploidy and limited association with live birth rates after euploid embryo transfers. Hum Reprod. 2021 doi: 10.1093/humrep/deab014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drakopoulos P, Blockeel C, Stoop D, Camus M, de Vos M, Tournaye H, et al. Conventional ovarian stimulation and single embryo transfer for IVF/ICSI. How many oocytes do we need to maximize cumulative live birth rates after utilization of all fresh and frozen embryos? Hum Reprod. 2016;31(2):370–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev316. PubMed PMID: 26724797. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Polyzos NP, Drakopoulos P, Parra J, Pellicer A, Santos-Ribeiro S, Tournaye H, et al. Cumulative live birth rates according to the number of oocytes retrieved after the first ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a multicenter multinational analysis including approximately 15,000 women. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(4):661–70 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.04.039. PubMed PMID: 30196963. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Magnusson A, Kallen K, Thurin-Kjellberg A, Bergh C. The number of oocytes retrieved during IVF: a balance between efficacy and safety. Hum Reprod. 2017:1–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex334. PubMed PMID: 29136154. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Nelson SM, Lawlor DA. Predicting live birth, preterm delivery, and low birth weight in infants born from in vitro fertilisation: a prospective study of 144,018 treatment cycles. PLoS Med. 2011;8(1):e1000386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000386.PubMedPMID:21245905;PubMedCentralPMCID:PMCPMC3014925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, Racowsky C, de Mouzon J, Sokol R, et al. The International Glossary on Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(3):393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, Racowsky C, de Mouzon J, Sokol R, et al. The International Glossary on Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(9):1786–1801. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex234.PubMedPMID:29117321;PubMedCentralPMCID:PMCPMC5850297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reynolds KA, Omurtag KR, Jimenez PT, Rhee JS, Tuuli MG, Jungheim ES. Cycle cancellation and pregnancy after luteal estradiol priming in women defined as poor responders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(11):2981–2989. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det306.PubMedPMID:23887073;PubMedCentralPMCID:PMCPMC3795468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang X, Wu J. Effects of luteal estradiol pre-treatment on the outcome of IVF in poor ovarian responders. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(3):196–200. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2012.736558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawrenz B, Ruiz F, Engelmann N, Fatemi HM. Individual luteolysis post GnRH-agonist-trigger in GnRH-antagonist protocols. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2017;33(4):261–264. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2016.1266325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rienzi L, Ubaldi F, Anniballo R, Cerulo G, Greco E. Preincubation of human oocytes may improve fertilization and embryo quality after intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(4):1014–1019. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.4.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Capalbo A, Rienzi L, Cimadomo D, Maggiulli R, Elliott T, Wright G, et al. Correlation between standard blastocyst morphology, euploidy and implantation: an observational study in two centers involving 956 screened blastocysts. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(6):1173–1181. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maggiulli R, Giancani A, Cimadomo D, Ubaldi FM, Rienzi L. Human Blastocyst Biopsy and Vitrification. J Vis Exp. 2019;(149). 10.3791/59625. PubMed PMID: 31403619. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Cimadomo D, Capalbo A, Levi-Setti PE, Soscia D, Orlando G, Albani E, et al. Associations of blastocyst features, trophectoderm biopsy and other laboratory practice with post-warming behavior and implantation. Hum Reprod. 2018;33(11):1992–2001. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Treff NR, Tao X, Ferry KM, Su J, Taylor D, Scott RT., Jr Development and validation of an accurate quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction-based assay for human blastocyst comprehensive chromosomal aneuploidy screening. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(4):819–824. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.01.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Capalbo A, Treff NR, Cimadomo D, Tao X, Upham K, Ubaldi FM, et al. Comparison of array comparative genomic hybridization and quantitative real-time PCR-based aneuploidy screening of blastocyst biopsies. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(7):901–906. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.222.PubMedPMID:25351780;PubMedCentralPMCID:PMCPMC4463508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia-Pascual CM, Navarro-Sanchez L, Navarro R, Martinez L, Jimenez J, Rodrigo L, et al. Optimized NGS Approach for Detection of Aneuploidies and Mosaicism in PGT-A and Imbalances in PGT-SR. Genes (Basel). 2020;11(7). doi: 10.3390/genes11070724. PubMed PMID: 32610655; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7397276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Forman EJ. Demystifying "mosaic" outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2019;111(2):253. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodrich D, Tao X, Bohrer C, Lonczak A, Xing T, Zimmerman R, et al. A randomized and blinded comparison of qPCR and NGS-based detection of aneuploidy in a cell line mixture model of blastocyst biopsy mosaicism. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33(11):1473–1480. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0784-3.PubMedPMID:27497716;PubMedCentralPMCID:PMCPMC5125146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Girardi L, Patassini C, Fabiani M, Caroselli S, Serdarogullari M, Coban O, et al. The application of more stringent parameters for mosaic classification in blastocyst-stage preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies reduces false positive mosaic rates without comprising true detection. Human Reproduction. 2020;35(Suppl July 2020):i35-i6.

- 40.Girardi L, Serdarogullari M, Patassini C, Poli M, Fabiani M, Caroselli S, et al. Incidence, Origin, and Predictive Model for the Detection and Clinical Management of Segmental Aneuploidies in Human Embryos. Am J Hum Genet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Popovic M, Dhaenens L, Taelman J, Dheedene A, Bialecka M, De Sutter P, et al. Extended in vitro culture of human embryos demonstrates the complex nature of diagnosing chromosomal mosaicism from a single trophectoderm biopsy. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(4):758–769. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Popovic M, Dhaenens L, Boel A, Menten B, Heindryckx B. Chromosomal mosaicism in human blastocysts: the ultimate diagnostic dilemma. Hum Reprod Update. 2020 doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmz050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Capalbo A, Poli M, Cimadomo D, Benini F, Patassini C, Rubio C, et al. Low-degree mosaicism profiles do not provide clinically useful predictive values: interim results from the first multicenter prospective non-selection study on the transfer of mosaic embryos. Human Reproduction. 2020;35(Suppl July 2020):i368.

- 44.Vaiarelli A, Cimadomo D, Patrizio P, Venturella R, Orlando G, Soscia D, et al. Biochemical pregnancy loss after frozen embryo transfer seems independent of embryo developmental stage and chromosomal status. Reprod Biomed Online. 2018;37(3):349–357. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malizia BA, Hacker MR, Penzias AS. Cumulative live-birth rates after in vitro fertilization. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(3):236–243. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ubaldi FM, Cimadomo D, Capalbo A, Vaiarelli A, Buffo L, Trabucco E, et al. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis for aneuploidy testing in women older than 44 years: a multicenter experience. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(5):1173–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Modest AM, Wise LA, Fox MP, Weuve J, Penzias AS, Hacker MR. IVF success corrected for drop-out: use of inverse probability weighting. Hum Reprod. 2018;33(12):2295–2301. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey309.PubMedPMID:30325421;PubMedCentralPMCID:PMCPMC6238364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gameiro S, Boivin J, Peronace L, Verhaak CM. Why do patients discontinue fertility treatment? A systematic review of reasons and predictors of discontinuation in fertility treatment. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18(6):652–669. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms031.PubMedPMID:22869759;PubMedCentralPMCID:PMCPMC3461967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaughan DA, Leung A, Resetkova N, Ruthazer R, Penzias AS, Sakkas D, et al. How many oocytes are optimal to achieve multiple live births with one stimulation cycle? The one-and-done approach. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(2):397–404 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.10.037. PubMed PMID: 27916206. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Cobo A, Garrido N, Crespo J, Jose R, Pellicer A. Accumulation of oocytes: a new strategy for managing low-responder patients. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;24(4):424–432. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Results from the couples in the conventional approach (COS 1 + COS 2) group and their matched* couples in the DuoStim (Stim I + Stim II in the same ovarian cycle) group. Each circle represents a cumulus oocyte complex (COC) retrieved. If green, it developed as an euploid blastocyst and resulted in a live birth after transfer; if purple, it developed as an euploid blastocyst but did NOT result in a live birth after transfer; if orange, it developed as an euploid blastocyst which is still available for transfer; if red, it developed as an aneuploid blastocyst; if grey, it did not reach the blastocyst stage. In the conventional approach group, we highlighted the couples who dropped-out from the treatment after a failed first attempt. In the DuoStim group, we highlighted the patients who did not respond to the second stimulation in the same ovarian cycle. *The couples were matched for maternal age, sperm factor, number of cumulus oocytes complexes (COCs) and blastocysts obtained after the first COS.

Supplementary file1 (PDF 264 kb)

Supplementary Figure 2. Sub-analysis of the cumulative live birth delivery rates (CLBdR) in the conventional approach and the matched* DuoStim groups according to the number of blastocysts obtained after the first controlled ovarian stimulation (COS). The treatment drop-out rate among couples who failed the first attempt has been reported also for the former group. Below each cluster we reported also the mean maternal age. *Besides maternal age and number of blastocysts obtained after the first COS, the couples were matched also for sperm factor and number of cumulus oocyte complexes retrieved after first COS.

Supplementary file2 (PDF 77 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.