Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate knowledge of age-related fertility decline and oocyte cryopreservation among resident physicians in obstetrics and gynecology (ob-gyn) compared to residents in other specialties.

Methods

An online survey was sent to the US residency program directors for ob-gyn, internal medicine, emergency medicine, family medicine, general surgery, pediatrics, and psychiatry. They were asked to forward the survey to their respective residents. The survey consisted of three sections: fertility knowledge, oocyte cryopreservation knowledge, and attitudes toward family building and fertility preservation. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to compare outcomes between ob-gyn and non-ob-gyn residents.

Results

Of the 2,828 completed surveys, 450 (15.9%) were by ob-gyn residents and 2,378 (84.1%) were by residents in other specialties. 66.3% of respondents were female. The median number of correct answers was 2 out of 5 on the fertility knowledge section and 1 out of 3 on the oocyte cryopreservation knowledge section among both ob-gyn and non-ob-gyn residents. After adjusting for covariates, residents in ob-gyn were no more likely to answer these questions correctly than residents in other specialties (fertility knowledge, adjusted OR .97, 95% CI .88–1.08; oocyte cryopreservation knowledge, adjusted OR 1.05, 95% CI .92–1.19). Ob-gyn residents were significantly more likely than non-ob-gyn residents to feel “somewhat supported” or “very supported” by their program to pursue family building goals (83.5% vs. 75.8%, OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.23–2.14).

Conclusions

Resident physicians, regardless of specialty, have limited knowledge of natural fertility decline and the opportunity to cryopreserve oocytes. These data suggest need for improved fertility education.

Keywords: Fertility awareness, Oocyte cryopreservation, Resident physician, Family building

Introduction

Women in the USA are increasingly choosing to delay childbearing for reasons including career advancement, lack of a partner, and financial barriers [1]. This trend is accompanied by challenges associated with age-related increases in aneuploidy, spontaneous abortion, and infertility [2, 3]. Oocyte cryopreservation, or egg freezing, offers a possible means to preserve the reproductive potential associated with younger oocytes. Recent studies have demonstrated similar fertilization and pregnancy rates between patients who conceived with cryopreserved oocytes and those who underwent in vitro fertilization with fresh oocytes [4–7]. The probability of live birth, however, remains dependent on the age at which oocyte cryopreservation is performed [8]. In other words, a women’s age at the time of oocyte cryopreservation, rather than a women’s age when using cryopreserved oocytes, remains the primary determinant of success among women who attempt to conceive with cryopreserved oocytes.

As a group, resident physicians dedicate a substantial amount of time to their careers and are thus predisposed to postponing childbearing. In addition, residents are often part of a patient’s healthcare team. However, little is known about the fertility knowledge of resident physicians. One small study surveyed 238 obstetrics and gynecology (ob-gyn) residents; nearly one-third of whom overestimated the age at which female fertility declines [9]. These findings are consistent with data from the general population, even in well-educated individuals [1, 10–17]. For example, one study demonstrated that approximately one-third of university students overestimated the age at which female fertility declines [14], and in another study, almost half of medical student and resident physician participants vastly overestimated the likelihood of natural conception [17].

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate knowledge of age-related fertility decline and oocyte cryopreservation among resident physicians in ob-gyn compared to residents in other specialties. We hypothesized that ob-gyn residents have a more accurate comprehension of fertility and oocyte cryopreservation than non-ob-gyn residents. Our secondary objective was to examine attitudes toward family building among residents of different specialties.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional national online survey study was granted exempt status by the Institutional Review Board of Duke University because no identifiable private information was collected. A hyperlink to the online survey was sent to program directors of US residency programs accredited by the Accreditation Counsel for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) between January 29, 2019, and February 4, 2019. The seven largest specialties were included: ob-gyn, internal medicine, emergency medicine, family medicine, general surgery, pediatrics, and psychiatry. Program directors were asked to forward the survey link to their respective residents. In addition to the initial survey invitation, one reminder email was sent to the program directors between February 18, 2019, and February 27, 2019. The survey was made available between January 29, 2019, and March 15, 2019. Inclusion criteria were age 18 years or older and current status as a resident physician at an accredited program in the USA in one of the aforementioned specialties. Surveys were excluded if the specialty of the participant was missing or if none of the survey questions were answered.

Eligible participants reviewed and agreed to a standard consent form at the start of the survey. The survey consisted of three sections: (1) fertility knowledge, (2) oocyte cryopreservation knowledge, and (3) attitudes toward family building and fertility preservation. The knowledge portions of the survey included were adapted from an existing fertility questionnaire previously found to have good validity and reliability among medical, nursing, and undergraduate students [18]. Specifically, the questions regarding awareness of fertility issues were adapted for this study. The survey data was collected and stored through Duke Research Electronic Data Capture (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN), and responses were kept anonymous. At the end of the survey, participants were offered an opportunity to enter a raffle for one of five $100 Amazon gift cards (Amazon.com, Seattle, WA).

The primary outcomes were the number of correct answers on the fertility knowledge section and the oocyte cryopreservation knowledge section. The secondary outcomes were the proportion of respondents who had a child during residency or planned to have a child during residency, the perceived supportiveness of the residency program to pursue family building goals, the proportion of female residents who would consider oocyte cryopreservation, and the proportion of female residents who reported that their childbearing timeline would be impacted by the opportunity to cryopreserve oocytes. The response rate could not be calculated because the total number of people who received the survey was unknown.

All analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Continuous variables were compared between groups using Student’s t-tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests, while categorical variables were compared using Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests. The primary outcomes were modeled using multivariable logistic regression as the proportion of correct answers out of the total number of questions. These models were fit with and without adjustment for age, gender, race, post-graduate year, marital status, existing children, and history of infertility. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were generated from these models. Subset analyses were also performed to compare ob-gyn residents in post-graduate year 3 or 4 to ob-gyn in post-graduate year 1 or 2 and to compare ob-gyn residents in post-graduate year 3 or 4 to residents in other specialties.

Results

A total of 2,397 emails were sent to program directors. A total of 3,157 survey responses were received. After excluding 308 for blank survey responses and 21 for missing specialty, 2,828 surveys were included in the analysis. Survey participants represented 49 states as well as Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands. The resident training locations was distributed across different regions in the USA (21.9% from Northeast, 26.7% from Midwest, 34.9% from South, 14.9% from Western states).

Of the 2,828 included surveys, 450 (15.9%) surveys were from ob-gyn residents, and 2,378 (84.1%) surveys were from residents in other specialties (492 [17.4%] from emergency medicine, 514 [18.2%] from family medicine, 205 [7.2%] from general surgery, 454 [16.1%] from internal medicine, 411 [14.5%] from pediatrics, 302 [10.7%] from psychiatry) (Table 1). The mean age of respondents was similar between groups. Of the ob-gyn residents surveyed, 87.1% were female, compared to 62.3% of the non-ob-gyn residents. In both groups, respondents were predominantly Caucasian and from academic residency programs. Each year of residency was similarly represented. One-fifth of respondents reported having children, and 6.6% reported a history of infertility.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics among ob-gyn residents and residents in other specialties

| Demographic characteristic | Ob-gyn (N = 450) | Other specialties (N = 2,378) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD (range) | 29.4 ± 2.5 (25–46) | 30.1 ± 3.4 (24–60) |

| Female gender | 392 (87.1%) | 1,481 (62.3%) |

| Race | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 29 (7.0%) | 198 (9.0%) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 298 (71.6%) | 1,324 (59.9%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 22 (5.3%) | 102 (4.6%) |

| Other (Asian, Native American, Other, Mixed) | 67 (16.1%) | 587 (26.5%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 170 (40.9%) | 937 (42.8%) |

| Married or domestic partnership | 238 (57.2%) | 1,223 (55.9%) |

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | 8 (1.9%) | 28 (1.3%) |

| Residency program | ||

| Academic | 311 (70.5%) | 1,477 (63.5%) |

| Community | 117 (26.5%) | 800 (34.4%) |

| Other | 13 (2.9%) | 48 (2.1%) |

| Post-graduate year | ||

| 1 | 116 (25.9%) | 783 (33.2%) |

| 2 | 130 (29.0%) | 692 (29.3%) |

| 3 | 103 (23.0%) | 649 (27.5%) |

| ≥ 4 | 99 (22.1%) | 236 (10.0%) |

| Existing children | 74 (16.5%) | 507 (21.4%) |

| History of infertility | 27 (6.0%) | 158 (6.7%) |

*Denominators exclude missing responses

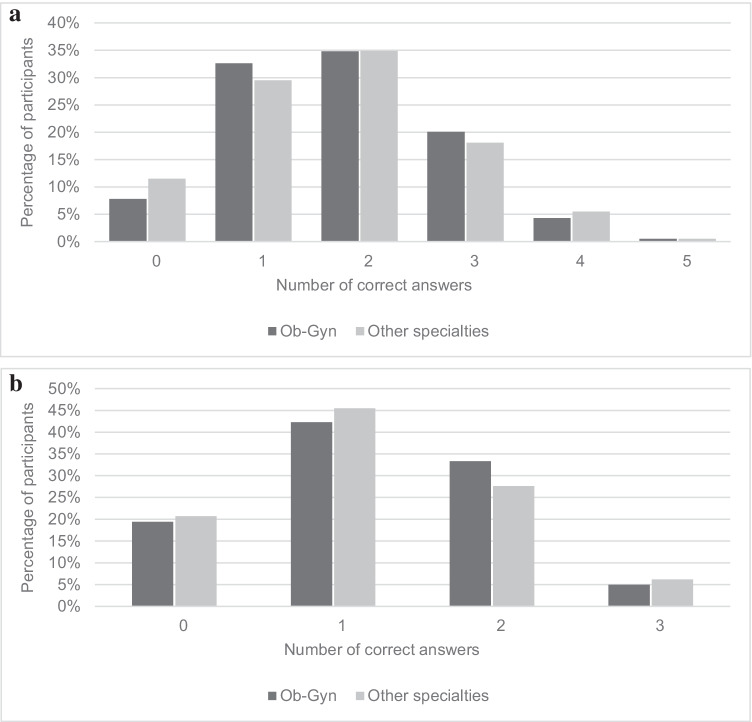

The median number of correct answers on the fertility knowledge section of the questionnaire was 2 out of 5 for both ob-gyn residents and non-ob-gyn residents (Fig. 1A, OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.94–1.14, P = 0.530). Less than 1% of the participants answered all the questions correctly. After controlling for age, gender, race, post-graduate year, marital status, existing children, and history of infertility, there remained no significant association between the number of correct answers and resident specialty (adjusted OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.88–1.08, P = 0.584). On the oocyte cryopreservation knowledge section of the questionnaire, the median number of correct answers was only 1 out of 3 regardless of specialty (Fig. 1B, OR 1.07, 95% CI 0.94–1.20, P = 0.305). After controlling for confounders, there was no significant association between the proportion of correct answers and resident specialty (adjusted OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.92–1.19, P = 0.479). Subset analyses categorizing ob-gyn residents by post-graduate year showed consistent findings; there were no significant differences in fertility knowledge or oocyte cryopreservation scores for ob-gyn residents in post-graduate year 3 or 4 compared with ob-gyn residents in post-graduate year 1 or 2 (fertility, adjusted OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.65–1.19, P = 0.393; cryopreservation, adjusted OR 1.30, 95% CI 0.89–1.90, P = 0.180). Similarly, there were no significant differences in fertility knowledge or oocyte cryopreservation scores for ob-gyn residents in post-graduate year 3 or 4 compared with residents in other specialties (fertility, adjusted OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.80–1.09, P = 0.368; cryopreservation, adjusted OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.82–1.20, P = 0.959).

Fig. 1.

a Fertility knowledge among residents in ob-gyn compared with residents in other specialties. b Oocyte cryopreservation knowledge among residents in ob-gyn compared with residents in other specialties

On the fertility knowledge section of the questionnaire, participants were most knowledgeable about the age at which women were the most fertile (Table 2, 72.7% correct responses among ob-gyn residents and 65.2% correction responses among residents in other specialties, OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.13–1.79, P = 0.003). Approximately half of respondents correctly identified 35–39 years as the age at which women experienced a marked decrease in the ability to become pregnant. Less than one-quarter of participants correctly answered questions on the probability of pregnancy among women in various age brackets. On the oocyte cryopreservation section of the questionnaire, fewer than half of respondents correctly estimated the cost of oocyte cryopreservation or the cost of egg storage. Additionally, residents greatly overestimated the probability of pregnancy for each cryopreserved oocyte, with only 23.9% of ob-gyn residents and 37.8% of residents in other specialties providing the correct answer of 5–15% (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.41–0.66, P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Correctly answered knowledge questions among residents in ob-gyn compared with residents in other specialties

| Outcomes | Ob-Gyn (N = 450) |

Other specialties (N = 2,378) |

OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| At what age are women the most fertile? | 306 (72.7%)a | 1447 (65.2%) | 1.42 (1.13–1.79) |

| At what age is there a slight decrease in a woman’s ability to become pregnant? | 61 (14.5%) | 425 (19.2%) | .71 (.53–.95) |

| At what age is there a marked decrease in a woman’s ability to become pregnant? | 228 (54.3%) | 1072 (48.9%) | 1.24 (1.02–1.53) |

| If a woman and a man regularly have unprotected intercourse during a period of 1 year, how large is the chance that she will become pregnant if she is 25–30 years old? | 84 (19.9%) | 574 (25.9%) | .71 (.55–.92) |

| If a woman and a man regularly have unprotected intercourse during a period of 1 year, how large is the chance that she will become pregnant if she is 35–40 years old? | 90 (21.3%) | 455 (20.5%) | 1.05 (.81–1.36) |

| When using frozen eggs, what is the chance of pregnancy per thawed egg? | 101 (23.9%) | 833 (37.8%) | .52 (.41–.66) |

| On average, what do you think the cost is to undergo one cycle of IVF to obtain and freeze eggs (including medications)? | 198 (46.8%) | 864 (38.9%) | 1.38 (1.12–1.71) |

| On average, how much do you think it costs to store frozen eggs for 1 year? | 225 (53.2%) | 957 (43.3%) | 1.49 (1.21–1.83) |

aValues represent the number of residents (% of residents) who answered the question correctly

With regard to secondary outcomes, approximately one-third of residents had a child during residency or planned to have a child during residency, regardless of specialty (Table 3). Concerns about financial barriers (30.3%) and career advancement (25.5%) were identified as the main challenges to childbearing during residency. Residents in ob-gyn were significantly more likely to feel “somewhat supported” or “very supported” by their programs to pursue family building goals (83.5% compared with 75.8%, OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.23–2.14, P < 0.001). More than half of all female residents would consider oocyte cryopreservation, and over one-quarter of all residents reported that the option to cryopreserve oocytes would have an impact on their personal childbearing timeline. When comparing responses of male and female residents, female residents were less likely to have a child in residency or plan to have a child in residency (32.2% compared with 41.3%, OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.57–0.79, P < 0.001). Female residents were also less likely to feel supported by their programs to pursue family building goals (75.7% compared with 79.7%, OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.65–0.96, P = 0.020).

Table 3.

Personal family building by ob-gyn vs other specialties

| Outcomes | Ob-gyn (N = 450) |

Other specialties (N = 2,378) |

OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Had a child during residency or are planning to have a child during residency | 152 (33.9%) | 841 (35.5%) | .93 (.75–1.15) |

| Feels supported by your program to pursue your family building goals | 350 (83.5%) | 1,676 (75.8%) | 1.62 (1.23–2.14) |

| Female residents who have not undergone egg freezing and would consider egg freezing for fertility preservation | 197 (55.5%) | 782 (57.8%) | .91 (.72–1.15) |

| Female residents who reported that the option of egg freezing would impact their childbearing timeline | 82 (22.5%) | 392 (28.6%) | .72 (.55–.95) |

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, a national survey of resident physicians demonstrated poor understanding of age-related fertility decline and oocyte cryopreservation. Fertility knowledge was no better among ob-gyn residents than residents of other specialties, regardless of post-graduate year. Family building goals were similar among residents in different specialties, but ob-gyn residents were more likely to report feeling supported by their program to pursue those goals.

Our findings are consistent with prior studies evaluating fertility knowledge in both the general population [1, 10–17] and ob-gyn resident population [9], all of which have shown these populations to have a poor understanding of age-related fertility decline and oocyte cryopreservation. We present novel data demonstrating that the fertility knowledge of ob-gyn residents is no better than that of residents in other specialties.

Although this survey did not investigate factors contributing to overestimation of natural fertility, one possibility for the continued and pervasive lack of fertility knowledge among physicians is limited infertility education. Even in ob-gyn residencies where reproductive endocrinology and infertility is a required subspecialty rotation, training is often short and disrupted by coverage duties [19]. In our study, almost half of ob-gyn residents overestimated the age at which fertility decline becomes more rapid. This is particularly surprising, given that the correct answer of 35–39 years corresponds with the commonly used obstetric terminology “advanced maternal age,” defined as 35 years or older.

Another possibility for the knowledge deficit surrounding natural fertility is frequent exposure to pregnant patients at advanced maternal age in residency, especially among ob-gyn residents. In 2018, the mean age at which a woman gave birth to her first child in the USA was at a record high of 26.9 years, predominantly due to rise in women postponing pregnancy until her 30s and 40s [20]. The media has also perpetuated a falsely optimistic perception of fertility at advanced maternal age. Both of these may distort the perception of fertility especially during residency, when many trainees often encounter outlier cases.

The overestimation of oocyte cryopreservation pregnancy rates was unexpected and likely reflects common misconceptions about the yield at each step between oocyte cryopreservation and clinical pregnancy. Existing data suggest that although 90–97% of oocytes survive warming and 71–79% are fertilized, implantation rates range from 17 to 41%, and clinical pregnancy rates range from 36 to 61%. This yields a clinical pregnancy rate per thawed oocyte of only 4.5–12% [4–7]. This knowledge deficit may lead to unrealistic optimism about outcomes for both patients and providers, particularly since the existing literature has been restricted to good-prognosis patients [21–24].

It is critical to address these knowledge gaps as both ob-gyn residents and patients identify healthcare providers as the primary source of information for natural fertility and oocyte cryopreservation [9, 25]. Unfortunately, many women do not recall having fertility discussions, and half of ob-gyn residents feel uncomfortable counseling patients on oocyte cryopreservation [25, 26]. As women increasingly postpone childbearing, it is especially important for physicians to initiate conversations about family building and fertility preservation. Ideally, ob-gyn providers should consider introducing these discussions with patients in their 20s and early 30s, an age that still affords women flexibility in their reproductive decision making. Providing unrealistic expectations about natural fertility and delaying timely referral to fertility specialists are both detrimental to a patient’s family planning goals. Additional studies are needed to evaluate how best to initiate these discussions with patients about fertility. Further studies are also needed to evaluate how fertility information can be accurately conveyed to both resident physicians as well as patients.

This study also revealed interesting findings regarding the residents’ personal childbearing plans. Resident physicians dedicate a large part of their optimal reproductive years to medical training, yet 6.6% of study respondents still reported a history of infertility. Since most residents are not actively trying to conceive during residency, this likely represents an underestimate of the proportion of residents who will ultimately receive infertility diagnoses. Indeed, it is estimated that approximately 1 in 4 female physicians are diagnosed with infertility, one-fifth of whom are ultimately unable to conceive [27]. In comparison, the estimated prevalence of infertility in the general population is between 7 and 15% [28]. Given the physical, mental, and financial toll that infertility can have on a physician’s well-being, the high prevalence of infertility among female physicians should be addressed throughout medical training, starting in medical school or even earlier during undergraduate medical education. It is also important that physicians have access to reproductive counseling and fertility testing as well as psychological support. Insurance coverage for these services could also help ease the financial burdens.

For many residents choosing to delay family building, infertility diagnoses will be delayed until later reproductive years, when fertility treatment success rates are lower. Oocyte cryopreservation could be a way for residents to preserve reproductive potential. Over half of the female residents in the study would consider egg freezing as an option for fertility preservation, and for over a quarter, egg freezing would impact their childbearing timeline. Potential barriers to pursuing oocyte cryopreservation during residency include time and cost.

The main limitation of this study is survey distribution through program directors rather than directly to residents, possibly resulting in selection bias and limiting generalizability. The study was also subject to nonresponse bias due to the subject matter, reflected in a larger female representation in survey responses. Nonresponse bias may also contribute to greater participation from residents who potentially have more knowledge and experience in fertility, which makes our study’s findings regarding limited knowledge of natural fertility and oocyte cryopreservation even more striking. Another limitation was the survey itself, which was chosen for its validity and reliability but utilized vague terminology like “slight” and “marked” that could be interpreted differently by participants. The survey also used heteronormative terminology and should be updated to address all possible relationship and family structures. Lastly, varying insurance statuses and state mandates on infertility coverage could potentially affect how resident physicians approach family building and oocyte cryopreservation.

Conclusion

This online survey of resident physicians demonstrated limited knowledge about fertility and oocyte cryopreservation. Although ob-gyn residents reported feeling supported in their own family building goals, they were no more knowledgeable about fertility than their peers in other specialties, and their knowledge did not improve throughout training. It is critical to address these knowledge gaps as resident physicians ascend to the front lines of providing reproductive healthcare.

Acknowledgements

The Duke Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Research Design Methods Core’s support of this project was made possible in part by CTSA Grant (UL1TR002553) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCATS or NIH.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Shelun Tsai and Jennifer Eaton. The statistical analysis was performed by Tracy Truong. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Shelun Tsai, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by the Charles B. Hammond Research Fund, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study was granted exempt status by the Institutional Review Board of Duke University because no identifiable private information was collected.

Informed consent

Eligible participants reviewed and agreed to a standard consent form at the start of the survey.

Consent to participate

Eligible participants reviewed and agreed to a standard consent form at the start of the survey. No identifiable private information was collected.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hodes-Wertz B, Druckenmiller S, Smith M, Noyes N. What do reproductive-age women who undergo oocyte cryopreservation think about the process as a means to preserve fertility? Fertil Steril. 2013;100(5):1343–1349.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.07.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassold T, Chiu D. Maternal age-specific rates of numerical chromosome abnormalities with special reference to trisomy. Hum Genet. 1985;70(1):11–17. doi: 10.1007/BF00389450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gosden RG. Maternal age: a major factor affecting the prospects and outcome of pregnancy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1985;442:45–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb37504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobo A, Kuwayama M, Perez S, Ruiz A, Pellicer A, Remohi J. Comparison of concomitant outcome achieved with fresh and cryopreserved donor oocytes vitrified by the Cryotop method. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(6):1657–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cobo A, Meseguer M, Remohí J, Pellicer A. Use of cryo-banked oocytes in an ovum donation programme: a prospective, randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(9):2239–2246. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rienzi L, Romano S, Albricci L, Maggiulli R, Capalbo A, Baroni E, et al. Embryo development of fresh “versus” vitrified metaphase II oocytes after ICSI : a prospective randomized sibling-oocyte study. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(1):66–73. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parmegiani L, Cognigni GE, Bernardi S, Cuomo S, Ciampaglia W, Infante FE, et al. Efficiency of aseptic open vitrification and hermetical cryostorage of human oocytes. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;23(4):505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang CC, Elliott TA, Wright G, Shapiro DB, Toledo AA, Nagy ZP. Prospective controlled study to evaluate laboratory and clinical outcomes of oocyte vitrification obtained in in vitro fertilization patients aged 30 to 39 years. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1891–1897. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu L, Peterson B, Inhorn MC, Boehm JK, Patrizio P. Knowledge, attitudes, and intentions toward fertility awareness and oocyte cryopreservation among obstetrics and gynecology resident physicians. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(2):403–411. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milman LW, Senapati S, Sammel MD, Cameron KD, Gracia C. Assessing reproductive choices of women and the likelihood of oocyte cryopreservation in the era of elective oocyte freezing. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(5):1214–1222.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniluk JC, Koert E. Childless women’s beliefs and knowledge about oocyte freezing for social and medical reasons. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(10):2313–2320. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoop D, Cobo A, Silber S. Fertility preservation for age-related fertility decline. Lancet. 2014;384(9950):1311–1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson BD, Pirritano M, Tucker L, Lampic C. Fertility awareness and parenting attitudes among American male and female undergraduate university students. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(5):1375–1382. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meissner C, Schippert C, von Versen-Höynck F. Awareness, knowledge, and perceptions of infertility, fertility assessment, and assisted reproductive technologies in the era of oocyte freezing among female and male university students. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33(6):719–729. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0717-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hurley EG, Ressler IB, Young S, Batcheller A, Thomas MA, DiPaola KB, et al. Postponing childbearing and fertility preservation in young professional women. South Med J. 2018;111(4):187–191. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikhena-Abel DE, Confino R, Shah NJ, Lawson AK, Klock SC, Robins JC, et al. Is employer coverage of elective egg freezing coercive?: a survey of medical students’ knowledge, intentions, and attitudes towards elective egg freezing and employer coverage. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34(8):1035–1041. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-0956-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Will EA, Maslow BS, Kaye L, Nulsen J. Increasing awareness of age-related fertility and elective fertility preservation among medical students and house staff: a pre- and post-intervention analysis. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(5):1200–1205.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lampic C, Svanberg AS, Karlström P, Tydén T. Fertility awareness, intentions concerning childbearing, and attitudes towards parenthood among female and male academics. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(2):558–564. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steiner AZ, Fritz M, Sites CK, Coutifaris C, Carr BR, Barnhart K. Resident experience on reproductive endocrinology and infertility rotations and perceived knowledge. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2):324–330. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182056457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK. Births: final data for 2018. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(13):1–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rienzi L, Cobo A, Paffoni A, Scarduelli C, Capalbo A, Vajta G, et al. Consistent and predictable delivery rates after oocyte vitrification: an observational longitudinal cohort multicentric study. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(6):1606–1612. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ubaldi F, Anniballo R, Romano S, Baroni E, Albricci L, Colamaria S, et al. Cumulative ongoing pregnancy rate achieved with oocyte vitrification and cleavage stage transfer without embryo selection in a standard infertility program. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(5):1199–1205. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cobo A, García-Velasco JA, Coello A, Domingo J, Pellicer A, Remohí J. Oocyte vitrification as an efficient option for elective fertility preservation. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(3):755–764.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cobo A, García-Velasco J, Domingo J, Pellicer A, Remohí J. Elective and Onco-fertility preservation: factors related to IVF outcomes. Hum Reprod. 2018;33(12):1–10. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lundsberg LS, Pal L, Gariepy AM, Xu X, Chu MC, Illuzzi JL. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding conception and fertility: a population-based survey among reproductive-age United States women. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(3):767–774.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esfandiari N, Litzky J, Sayler J, Zagadailov P, George K, DeMars L. Egg freezing for fertility preservation and family planning: a nationwide survey of US Obstetrics and Gynecology residents. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2019;17(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12958-019-0459-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stentz NC, Griffith KA, Perkins E, Jones RD, Jagsi R. Fertility and childbearing among American female physicians. J Womens Health. 2016;25(10):1059–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Thoma ME, McLain AC, Louis JF, King RB, Trumble AC, Sundaram R, et al. Prevalence of infertility in the United States as estimated by the current duration approach and a traditional constructed approach. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1324–1331.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Not applicable.