Abstract

Background:

This scoping review aimed to investigate the status of breast cancer (BC) preventive behaviors and screening indicators among Iranian women in the past 15 years. BC, as the most common cancer in women, represents nearly a quarter (23%) of all cancers. Presenting the comprehensive view of preventive modalities of BC in the past 15 years in Iran may provide a useful perspective for future research to establish efficient services for timely diagnosis and control of the disease.

Materials and Methods:

The English and Persian articles about BC screening modalities and their indicators in Iran were included from 2005 to 2020. English electronic databases of Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus, and Persian databases of Scientific Information Database (SID) and IranMedex were used. The critical information of articles was extracted and classified into different categories according to the studied outcomes.

Results:

A total of 246 articles were assessed which 136 of them were excluded, and 110 studies were processed for further evaluation. Performing breast self-examination, clinical breast examination, and mammography in Iranian women reported 0%–79.4%, 4.1%–41.1%, and 1.3%-45%, respectively. All of the educational interventions had increased participants’ knowledge, attitude, and practice in performing the screening behaviors. The most essential screening indicators included participation rate (3.8% to 16.8%), detection rate (0.23–8.5/1000), abnormal call rate (28.77% to 33%), and recall rate (24.7%).

Conclusion:

This study demonstrated heterogeneity in population and design of research about BC early detection in Iran. The necessity of a cost-effective screening program, presenting a proper educational method for increasing women's awareness and estimating screening indices can be the priorities of future researches. Establishing extensive studies at the national level in a standard framework are advised

Keywords: Breast cancer, Iran, prevention, scoping review, screening

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common female cancer worldwide, representing nearly a quarter (23%) of all cancers in women.[1] In Iran, in 2015, the number of BC patients was 12802, and the age-standardized incidence rate was 32.63/100,000. Hence, the age distribution of BC compared to its counterparts is low because of its relatively young population. Almost 51% of patients were under 50 years old. It is estimated that about 10,000 women are diagnosed and treated for BC each year.[2,3]

Approaches to reducing cancer's global burden include two major strategies: Screening and early detection and active preventive intervention.[4] Screening, as one of the most critical early detection methods, has been performed in low- and middle-income countries in only 2.2% of women aged 40–49 years.[5] The findings confirmed that screening methods were less common in Iranian women,[2] and there is no systematic screening strategy for BC in Iran.[6]

Screening methods are mammography, breast self-examination (BSE), and clinical breast examination (CBE).[7] Although mammography screening was approved as an effective method, a study demonstrated that this method is not cost-effective in Iran.[6] BSE can enhance women's awareness, empowerment, and responsibility to their health.[8] The previous studies showed that almost 60% of females did not know how to perform BSE or did not have the necessary skills to do it.[9,10,11] CBE is considered a low-cost method with a broader implementation ability that requires no equipment.[5] Different factors such as demographic variables, awareness, literacy, social, and economic conditions can affect BC screening behaviors[12] which should be considered in planning a cost-effective strategy to control BC in Iranian women.

Presenting the comprehensive view of preventive modalities of BC in the past 15 years in Iran may provide a helpful perspective for future research to establish efficient services for timely diagnosis and control of the disease. Hence, this scoping review aims to present an overall demonstration of observational and interventional screening status in Iran. Introducing screening indicators in related articles may provide useful data for policy-makers to implement a proper strategy to control the disease.

Scoping review question

“What are the results of articles related to BC screening strategies and indicators in Iran in the past 15 years?”

Scoping review sub-questions

“What are the status of BC prevention behavior and influencing factors on screening behaviors?”

“Which educational interventions are effective in improvement of screening behavior?”

“What are the statistical indicators of BC screening?”

Inclusion criteria

All the published articles about BC prevention in Iran from January 2005 to January 2020 were included in the study. English online electronic databases of Web of Science, PubMed and Scopus, and Persian databases of SID and IranMedex were used.

METHODS

This study is part of a big project to study different aspects of BC in Iran. All of the published articles about BC in Iran within the defined time horizon were included in the study. They covered various aspects of epidemiology, genetics, prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and supportive care in BC. The prevention subgroup was categorized into two themes, screening modalities and indicators, prevention behaviors, and their barriers. The studies in the field of screening strategies and indicators were assessed in this scoping review.

Search strategy

Details of data sources and methodology of the big project between 2005 and 2015 time horizon have been presented in another article.[13] The same methodology was extended to articles published up to 2020. The current study consists of all articles published from January 2005 to 2020. English online electronic databases of Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus, and Persian databases of SID and IranMedex were used. English search formula was “BC” OR “breast carcinoma” OR “breast tumor” OR “breast neoplasm” AND Iran. Persian search formula was a combination of Iran with the words of  Breast tumor, BC, Breast carcinoma, and Breast neoplasm [Appendix 1].

Breast tumor, BC, Breast carcinoma, and Breast neoplasm [Appendix 1].

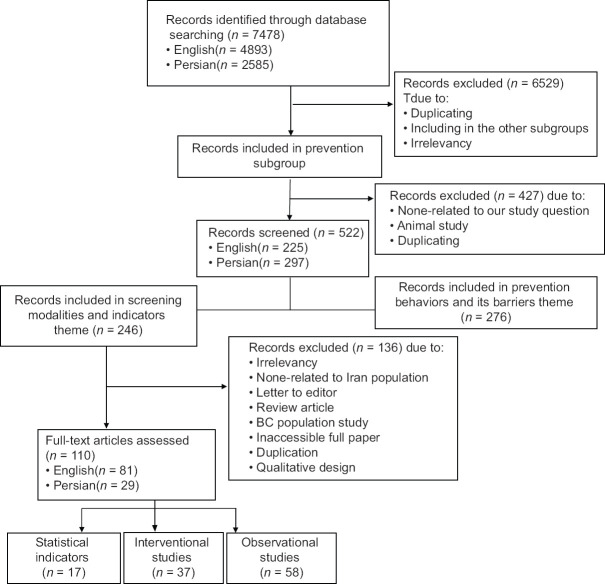

Source of evidence screening and selection

Screening of primary search and dividing to subgroups was achieved by three experienced reviewers in the field of BC; two surgeons and one epidemiologist. Totally 7478 studies consisting of 4893 English and 2585 Persian abstracts were included in the main project, of which 949 abstracts were located in the prevention subgroup. In this step, 522 items (225 English and 297 Persian) were included by deleting unrelated studies and duplicated titles, abstracts, and full text of articles. The results of 246 articles in the field of screening strategies and indicators were considered eligible for this review. After assessing full texts, 136 articles were excluded, and 110 studies consisting of 81 English and 29 Persian were evaluated.

It should be noted that the results of the two articles have been presented in two tables jointly. Reasons of exclusion were irrelevancy (53 articles), just abstract presentation (7 articles), no relation to the Iran population (8 articles), letter to editor (3 articles), review article (2 articles), BC population study (4 articles), inaccessible full paper (1 article), qualitative study (3 articles), and duplication (55 articles). In this phase, the reason for duplications was to publish an article in either Persian and English or two or more journals [Chart 1].

Chart 1.

PRISMA chart of recruitment of articles in the study

Studies reviewed were classified into three categories according to their main themes, including observational (58 articles), interventional (37 articles), and statistical indicators (17 articles).

Data extraction

The research team obtained the full texts of the abstracts. If it was not available, a letter was sent to the author to take the necessary information. Two reviewers critically evaluated the selected articles by a checklist. In case of disagreement, they discussed and decided about their eligibility.

Because of the wide variation in the methodology and results of the included studies, an Excel sheet was designed for data extraction. The first part of the datasheet was “general information” such as the title, the place and time of the study, and publication year. The second part included “methodological information” consisting of study design, sample size, studied population, intervention modality, and measurement tools. The third part was composed of “outcome measurements”, such as performance of the screening method, effect of interventions, different screening indicators such as recall rate, participation rate, response rate, and detection rate. All of the articles were extracted by two reviewers, and the research team manager organized the two extracted forms into one sheet.

Since the main objective of this scoping review was to demonstrate the distribution of BC prevention researches in Iran, no article was excluded from the study due to low quality. To show the limitations of studies, we assigned the incomplete data with “NA,” which stands for “Not Assigned.”

Analysis and presentation of results

Rate of screening behavior performance, affecting factors, the impact of different educational interventions and statistical indicators such as detection rate, recall rate, and participation rate were extracted from the included studies. Articles that more than one-third of the presented data pertained to the years before 2005 were excluded from the study. If an article was published in either Persian and English or two or more journals, just their English version and the first publication were included. The details of data in each subject were presented in a separate table.

RESULTS

Search results

The results of 246 articles in the field of screening strategies and indicators were considered eligible for this review. After assessing full texts, 136 articles were excluded, and 110 studies consisting of 81 English and 29 Persian were evaluated [Appendix 2].

Inclusion of sources of evidence

The included studies in this field were subcategorized in observational studies (58 articles), educational interventions (37 articles), and statistical indicators (17 articles). The essential data of those three objectives consisting of general information, methodological information, and outcome measurement indices were recorded in separated tables. More details have been presented in [Appendix 3].

Appendix 3.

Data extraction instrument

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

| Scoping review details | |

| Scoping review title | Status of breast cancer screening strategies and indicators in Iran: A scoping review |

| Review objective/s | Providing useful data for policy-makers to implement a proper strategy to control the disease |

| Review question/s | What are the results of articles related to breast cancer screening strategies and indicators in Iran in the past 15 years? |

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | |

| Population | Iranian females |

| Concept | Prevention of breast cancer |

| Context | Screening behaviors, educational interventions, statistical indicators |

| Types of evidence source | All of the published articles on the prevention of breast cancer in Iran |

| Evidence source details and characteristics | |

| Citation details (e.g., author/s, date, title, journal, volume, issue, pages) | They have been presented in tables |

| Country | Iran |

| Context | Screening behavior, educational interventions, statistical indicators |

| Participants (details e.g., age/sex and number) | They have been presented in tables |

| Details/results extracted from the source of evidence (in relation to the concept of the scoping review) | |

| Screening behaviors | Table 1 |

| Educational interventions | Table 2 |

| Statistical indicators | Table 3 |

Review finding

The finding results are presented in three following subheadings:

Observational studies of BC screening

Among 58 articles in Table 1, 56 items were cross-sectional, and 2 items were survey studies. Most of the studied populations were females referred to Healthcare centers (HCCs). Factors influencing screening behaviors consisted of health belief model (HBM) components, fear, proactive coping, state of mind and advocacy, educational level, positive family history of breast cancer, family support, awareness, physician recommendation, and age. Four articles had introduced “physicians and treatment staff” as the most important sources of information about screening behaviors.[14,15,16,17]

Table 1.

Observational studies of breast cancer screening

| First author/city/year of publication | Study design | Study population | Sample size | Mean age (SD) | Instrument | The most important findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valizadeh, Tabriz, 2006[19] | Cross-sectional | Nurses in 21 therapeutic centers | 420 | NA | QNR | BSE: 70.2% Frequency of BSE: 39% every 2 months and more |

| Aghababaii, Hamedan, 2006[20] | Cross-sectional | Female nursing and midwifery students | 68 | NA | QNR | BSE (total: 79.4%, regular: 29.4%) |

| Abbaszadeh, Kerman, 2007[21] | Cross-sectional | Females >35 years | 296 | NA | QNR | Total HBM scores in mammography group >the group without mammography |

| Heidari, Zahedan, 2008[22] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to Qouds maternity hospital in Zahedan | 384 | 28.8 (8.4) | INTVW with purposed QNR | BSE (regular: 4.5%, occasionally: 18.7%, never: 76.8%) CBE history: 4.1% Mammography history: 1.3% |

| Simi, Shiraz, 2009[10] | Cross-sectional | Females 25-54 years referred to Shiraz Oil company polyclinic | 300 | Median: 38.5 (14) | QNR | BSE (total: 53.3%, find an abnormal examination: 5.6%, positive finding: 3.8%, did not know how to do: 52.9%, do it incorrect method and time: 3%) |

| Khalili, Tabriz, 2009[23] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to HCCs | 400 | 30.1 (7.4) | QNR, C/L | BSE: 18.8% CBE: 19.1% Mammography: 3.3% |

| Salimi Pormehr, Ardebil, 2010[24] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to HCCs | 300 | 29 (8) | QNR | BSE: 4% CBE: 4.7% Mammography: 3.7% |

| Alavi, Mashhad, 2010[25] | Cross-sectional | Gynecologic specialists and residents | 124 | 43.1 | QNR | BSE: Normal group (regular: 33%, irregular: 44%, never: 23%) High-risk group (regular: 46.7%, irregular: 53.3%) Mammography (normal group: 11.8%, high risk group: 27.1%) |

| Sultan Ahmadi, Kerman, 2010[26] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to HCCs | 200 | 30.60 (7.89) | QNR | BSE: 22.5% CBE: 21.5% |

| Noroozi, Bushehr, 2011[27] | Cross-sectional | Females working in public places of Bushehr | 388 | 34.32 (10.66) | QNR | BSE (total: 37.1%, regular: 7.5%) Mammography: 14.3% CBE: 5.9% |

| Hasani, Bandarabas, 2011[28] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to HCCs | 240 | 37.2 (6.1) | QNR | BSE (total: 31.7%, regular: 7.1%) |

| Yadollahie, 11 cities of Iran, 2011[11] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to HCCs | 3030 | Median: 40 (14) | INTVW, QNR | BSE (total: 49.4%, incorrect method and time: 9.6%, did not know how to do: 30.9%) |

| Samah, Tehran, 2012[29] | Cross-sectional | Asymptomatic females 35-69 years | 400 | NA | QNR | Mammography: 21.5% |

| Harirchi, Semnan and Khorasan, 2012[30] | Cross-sectional | Females >30 years | 770 | 46.91 (13.3) | QNR | The risk of not performing BSE, CBE, mammography for illiterate females were respectively 4.56, 2.51, 3.14, times more than literate females |

| Aflakseir, Shiraz, 2012[31] | Cross-sectional | Female staff at SUMS and SU | 113 | 48 (8.02) | QNR | BSE: 51% Mammography: 21% |

| Moodi, Isfahan, 2012[32] | Survey | Females >40 years | 384 | 52.24 (8.2) | INTVW, QNR | Mammography history: 44.3% |

| Kadivar, Tehran, 2012[33] | Cross-sectional | Female physicians and female nonhealthcare personnel | 196 | Physicians: 46.06 (8.0) Nonhealthcare personnel: 36.97 (9.38) |

QNR | BSE (physicians: 37.6%, nonhealthcare personnel: 26.1%) CBE (physicians: 31.25%, nonhealthcare personnel: 27.59%) mammography (physicians: 18.75%, nonhealthcare personnel: 17.24%) |

| Fouladi, Ardabil, 2013[34] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to HCCs | 380 | 38.12 (6.7) | QNR | BSE: 27% Mammography: 6.8% |

| Pirasteh, Tehran, 2013[35] | Cross-sectional | Married females referring to HCCs | 302 | NA | QNR | BSE in females with high self-efficacy was 1.17 times more than other females |

| Asgharnia, Rasht, 2013[36] | Cross-sectional | Females referring to Al-Zahra hospital | 400 | 48.07 (6.44) | QNR | BSE: 43.8% Mammography: 23.2% |

| Akhtari-Zavare, Hamedan, 2014[37] | Cross-sectional | Females referring to HCCs | 384 | 30 (9.1) | INTVW, QNR | BSE (total: 26%, didn’t know how to do: 72.1%) |

| Hajian-Tilaki, Babol, 2014[38] | Cross-sectional | Females aged 18-64 years | 500 | 31.2 (9.4) | INTVW, QNR | BSE: 38.4% CBE: 25.2% Mammography: 12% |

| Mokhtary, Tabriz, 2014[39] | Cross-sectional | Female HCP of tabriz health centers | 196 | 37.01 (7.54) | QNR | BSE: 73.2% CBE: 10.7% Mammography: 26.9% |

| Nojomi, Tehran, 2014[40] | Cross-sectional | Females referring to HCCs | 1012 | 38.2 | QNR | CBE (history: 22%, intention for doing in future: 75.8%) Mammography (history: 7%, intention for doing in future: 72.1%) |

| Shiryazdi, Yazd, 2014[41] | Cross-sectional | Female health care workers | 441 | 34.7 (13.7) | QNR | BSE (total: 41.9%, regular: 14.9%) Mammography: 10.6% |

| Ghodsi, Hamedan, 2014[42] | Cross-sectional | Females >35 years | 358 | NA | QNR, C/L | Performance: BSE (14.8%, 9.4% regularly), mammography 25.84% |

| Taymoori, Sanandaj, 2014[43] | Cross-sectional | Females >40 years referring to HCCs | 593 | 56.84 (5.04) | QNR | Mammography: 10.5% Most effective factors on Mammography: Self-efficacy and perceived susceptibility |

| Momenyan, Qom, 2014[44] | Cross-sectional | Nursing and midwifery students | 113 | 22.5 (3.7) | QNR | BSE: 63.2% Increasing perceived susceptibility and self-efficacy scores increases the likelihood of BSE |

| Bahrami, Sanandaj, 2015[14] | Cross-sectional | Females >20 years referring to the HCCs | 250 | 36 | QNR | BSE: 13.6% CBE: 4.8% Mammography: 9.6% Main information resources (physician: 62.4%, healthcare team: 16%) |

| Ahmadipour, Kerman, 2016[45] | Cross-sectional | Females referring to urban HCCs | 240 | 31.7 (7) | QNR | BSE (monthly: 25.6%, irregular: 21.8%, never: 52.6%) CBE (every year: 8.5%, irregular: 24.8%, never: 66.7%) Mammography (every year: 5.4%, irregular: 21.6%, never: 73%) |

| Vahedian Shahroodi, Mashhad, 2015[17] | Cross-sectional | Females health volunteer | 410 | 34.7 (9.4) | QNR | Sig relationship between the stages of the change model and BSE (P<0.001) Main information resource: physician and health care staff |

| Tavakoliyan, Kazeroon, 2015[16] | Cross-sectional | Females 20-65 years referring to HCCs | 300 | 39.55 (11.08) | QNR | BSE (regular: 12.7%, never: 48.3%) CBE (more than 5 times: 1.3%, never: 56.3%) Mammography (more than 5 times: 3%, never: 82.3%) Main information resource: Healthcare team and TV |

| Jouybari, Kermanshah, 2016[46] | Cross-sectional | Females referring to urban HCCs | 116 | NA | QNR | Mammography: 12.1% Predicators to undergoing Mammography: Educational level, positive BC_FH, family support, self-efficacy |

| Tahmasebi, Bushehr, 2016[47] | Cross-sectional | Females 20-50 years referred to HCCs | 400 | 27.3 (8.08) | QNR | BSE: 10.9% Predictive factors for BSE: Self-efficacy directly, awareness |

| Moshki, Tehran, 2016[48] | Cross-sectional | Females >50 years referred to mammography centers | 601 | 58.9 (6.4) | QNR | BSE (regular: 15%, irregular: 69.4%, never: 15.6%) CBE (regular: 29.5%, irregular: 54.5%, never: 20%) Mammography (repeated one time: 38%) Effective factors in repeat Mammography: Physician recommendation and BSE |

| Mirzaei-Alavijeh, Abadan, 2016[49] | Cross-sectional | Females 35-50 years referred to HCCs | 385 | 39.12 | QNR | BSE: 19.1% Mammography: 7.5% Predictive factors BC screening: Age, education, BC_FH, perceived severity, self-efficacy |

| Naghibi, Kermanshah, 2016[50] | Cross-sectional | Female high school teachers | 258 | 38.9 (8) | QNR | BSE: 48.1% CBE: 24.8% Mammography: 9.3% |

| Ghahramanian, Tabriz, 2016[51] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to HCCs | 370 | NA | QNR | BSE: 43% CBE: 23% Mammography: 38.2% |

| Aminisani, Baneh, 2016[52] | Cross-sectional | Females >40 years referred to HCCs | 561 | 43.64 (5.17) | QNR | Mammography: 22% |

| Farajzadegan, Isfahan, 2016[53] | Cross-sectional | Females with a BC_FH | 162 | 37.6 (11.16) | QNR | One-third of the participants were in the action/maintenance stages of TTM |

| Shirzadi, Tabriz, 2017[54] | Cross-sectional | Females from three Iranian cities | 1131 | 50.28 (7.93) | QNR | Mammography history: 28% Mammography adoption: 5.6% Predictors for mammography adoption: Perceived barriers, perceived benefits |

| Anbari, khoramabad, 2017[55] | Cross-sectional | Females 20-65 years referred to HCCs | 457 | 35.9 (9.7) | QNR | BSE: 10.3% CBE: 6% Mammography: 2.4% |

| Saadat, Tehran, 2017[56] | Survey | Female academics of TUMS | 99 | 47.79 (8.19) | QNR | BSE: 47.5% Mammography (regular: 7%, once in 2 past years: 24.4%) |

| Neinavae, Karaj, 2017[57] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to Karaj HCCs | 200 | 35.5 (9.7) | QNR | BSE (aware and performed correctly: 48.5%) |

| Farzaneh, Ardabil, 2017[58] | Cross-sectional | Females aged 20-60 years | 1134 | NA | QNR | BSE: 36.7% CBE: 5.6% Mammography: 16.5% |

| Miri, Birjand, 2017[59] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to HCCs | 450 | 30.7 (5.2) | QNR | BSE (preaction: 75.8%, precontemplation: 32.9%, contemplation: 19.6%, preparation: 23.3%, no experience of BSE) |

| Monfared, Rasht, 2017[60] | Cross-sectional | Females residing in Rasht | 1000 | 49.43 (10.18) | QNR | Mammography history: 45% Cause of screening: 68.4% checking health status Cause of not doing screening: 65.3% had no problem, and 3.4% had not enough information |

| Mirzaei-Alavijeh, Kermanshah, 2018[61] | Cross-sectional | Females who referred to HCCs | 408 | 39.61 (8.28) | QNR | Mammography history: 13% |

| Moghaddam Tabrizi, Urmia, 2018[15] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to HCCs | 348 | 43.25 (5.36) | QNR, C/L | Mammography history (never: 12%, at least one: 88%) Main source of information: Doctors |

| Pirzadeh, Isfahan, 2018[9] | Cross-sectional | Female medical students of MUI | 384 | 20.92 (1.26) | QNR | BSE (precontemplation: 42.8%, contemplation: 22%, preparation: 12.8%, action: 13.2%, maintenance: 19%) Didn’t have skills for BSE: 60% |

| Darvishpour, Guilan, 2018[62] | Cross-sectional | Females 20-65 years living in East Guilan cities | 304 | NA | QNR | BSE predictors: perceived benefits, self-efficacy, and perceived barriers Mammography predictors: perceived benefits and perceived barriers |

| Hayati, Abadan, 2018[63] | Cross-sectional | Females >35 years employees of Abadan School of Medical Sciences | 90 | 42.9 (5.8) | QNR | Mammography) total: 24.4%, once: 17.7%, twice or more: 6.7%) |

| Mahmoudabadi, Kerman, 2018[64] | Cross-sectional | Female nurses from Kerman educational hospitals | 209 | 35.53 (8.01) | QNR | BSE: 9.1% CBE: 26.3% Mammography: 15.8% |

| Izanloo, Mashhad, 2018[65] | Cross-sectional | Patients referred to outpatient clinics and people >14 years in public urban areas | 1469 | 38.8 (11.69) | QNR | Main screening methods (self-assessment: 41.6%, ultrasound: 46.4%) |

| Kardan-Souraki, Mazandaran, 2019[66] | Cross-sectional | Females participating in BC screening programs | 1165 | 37.15 (8.84) | QNR | BSE: 62% CBE: 41.1% Mammography: 21.7% |

| Khazir, Khorramabad, 2019[67] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to HCCs | 262 | 49.62 (7.79) | QNR | Mammography: 30.85% Significant relationship between HBM component and mammography behavior |

| Naimi, Kermanshah, 2019[68] | Cross-sectional | Married females clients of eight HCCs | 334 | 39.75 (7.73) | QNR | BC screening adoption (precontemplation: 58.4%, contemplation: 26.9%, preparation: 3%, action: 9.6%, maintenance: 2.1%) |

| Nikpour, Babol, 2019[18] | Cross-sectional | Urban population under the coverage of HCCs | 800 | 47.63 (10.46) | QNR | BSE: 17.5% CBE: 15.3% Mammography: 21.6% Mean 5-year and lifetime risk: 0.89±0.89 and 8.87±3.84 Predicting mammography performance: The high 5-year calculated risk |

HCC=Health Care Center; BC=Breast cancer; MUI=Isfahan University of Medical sciences; TUMS=Tehran University of Medical Sciences; BC_FH=Family history of breast cancer; SUMS=Shiraz University of Medical sciences; HCP=Health care provider; SU=Shiraz University; NA=Not available; QNR=Questionnaire; INTVW=Interview; C/ L=Checklist; BSE=Breast self-examination; CBE=Clinical breast examination; HBM=Health belief model; TTM=Transtheoretical model; SD=Standard deviation; TV=Television

Achievement of BSE by the best estimate varied from no experience to 79.4%. As well as, regular BSE was 4.5% to 47.5%. Performing annual CBE was reported in 4.1%-41.1% of participants, and mammography had been performed in 1.3%-45% of females. The results of three studies showed 52.9%, 30.9%, and 60% of females did not know how to perform BSE or did not have the necessary skills to do it.[9,10,11] The 5-year and lifetime risk perception of BC was subjectively assessed by the visual analog scale (VAS) from 0 to 100. The mean of 5-year BC risk perception was 0.89 ± 0.89, and its lifetime risk perception was 8.87 ± 3.84.[18] Higher 5-year risk perception was demonstrated to have more predictive power for performing mammography while not predicting achieving BSE or CBE.

Effect of educational interventions on screening behavior

Table 2 demonstrates 37 studies related to educational interventions and their impact on BC screening promotion. The design of studies was clinical trial (6 articles), randomized clinical trial (29 articles), and randomized field trial (2 articles). Females who referred to HCCs consisted majority of participants. The number of the sample ranged from 43 to 600 subjects. The educational methods mostly were in-person, except for two studies which were telephone counseling. Most educational models were HBM (13 studies), extended parallel process model (1 study), BASNEF (1 study), theory of planned behavior (TPB) (2 studies), systematic comprehensive health education and promotion (1 study), and HBM + TPB (1 study). The in-person education was achieved by methods like group discussion, role-playing, or peer education. Different instruments such as short messages, PowerPoint, media, lecture, mobile phone were applied. The result of the studies showed that educational interventions increased the knowledge, attitude, and practice of participants in performing the screening behaviors such as mammography, CBE, and BSE. It led to improved health belief, self-efficacy, the behavioral intention of screening, and perceived susceptibility/severity/benefits/barriers.

Table 2.

Effect of educational interventions on screening behavior

| First author/city/year of publication | Study design | Intervention | Study population | Sample size | Mean age (SD) | Instrument | The most important findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HajiKazemi, Tehran, 2006[69] | CT | Health counselling | Females attending premarital health counselling program | 600 | 21.82 (3.94) | QNR | After/before: Significant_difference in mean_score of awareness |

| Yeke Fallah, Ghazvin, 2007[70] | CT | Video and verbal training | Nursing and midwifery students of QUMS | 43 | 18 | QNR | After/before: Significant increase in mean K |

| Saatsaz, Amol, 2009[71] | CT | In-person education | Females high school teachers | 48 | NA | QNR | After/before: Significant improvement of P. about BSE, CBE, mammography |

| Hatefnia, Tehran, 2010[72] | RCT | HBM-based education | Females>35 years | 220 | NA | QNR | Intervention/control: Significant improvement in mean_score of K., HBM structures and mammography behavior |

| Moshfeghi, Arak, 2011[73] | RCT | Media and powerpoint | Physicians | 128 | NA | QNR | Significant_difference in mean_score of KAP after intervention in each group No significant_difference in KAP between two methods |

| Hajian, Tehran, 2011[74] | RCT | Health counseling | Females with BC_FH | 100 | 37.8 (11.7) | QNR | After/before: Significant_difference in mean K., HBM structures, BSE in intervention group Intervention/control (BSE: 82%/62%, P=0.021, CBE: 40%/18%, P=0.014, Mammography: 36%/30%, P=0.52) |

| Rahmati Najar Kolaie, Tehran, 2012[75] | CT | HBM-based education | Students living in the dormitory of TU | 99 | 21 (1.11) | QNR | After/before: Significant improvement of HBM structures |

| Farma, Zahedan, 2013[76] | CT | In-person education | Females guidance school teachers | 240 | 39.4 (7.4) | QNR | Intervention/control: Significant_difference in mean-score of KAP |

| Ghasemi, Shahrekord, 2014[77] | RCT | In-person education | Employee females in universities of Shahrekord | 50 | 33.5 (18) | QNR, C/L | After/before: Significant_difference in mean-scores of KAP, performing BSE |

| Khalili, Lavizan, 2014[78] | CT | HBM-based education | Females referred to HCCs | 144 | 34 (8.23) | QNR | After/before: Significant increase in mean K., HBM structures Intervention/control: Enhance the mean of K., HBM structures (P<0.001) |

| Torbaghan, Zahedan, 2014[79] | RCT | HBM-based education | Female employees of ZAUMS | 130 | Intervention 35.38 (8.01) Control 34.39 (8.98) |

QNR | Intervention/control: Significant_difference in mean-scores of awareness, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, P |

| Rezaeian, Isfahan, 2014[80] | RCT | Health counselling | Females>40 years | 290 | 50.48 (6.81) | QNR | After/before: Significant. improvement means K., HBM structures Intervention/control: Significant_difference in HBM structures, health beliefs about BC and mammography Sc_Behavour |

| Sargazi, Zahedan, 2014[81] | RCT | TPB-based education | Females referred to the clinics | 140 | Intervention 31.6 (0.9) Control 32.6 (1.1) |

QNR | After/before: Significant increase scores of K., A., control of perceived behavior, behavioral intention, adopting Sc_Behavior in the intervention group |

| Haghighi, Birjand, 2015[82] | RCT | In-person education | Employee females of BU | 89 | 39.2 (7.3) | QNR | After/before: Significant increase in mean K., A. toward BSE and number of females who performed BSE |

| Absavaran, Zabol, 2015[83] | RCT | Lecture method/cell phone method | Nurses in Zabol hospitals | 105 | Intervention 29.3 (4.4) Intervention 28.3 (4.4) Controll 29.1 (4.7) |

QNR | After/before: Significant_difference in mean_score KAP in both intervention groups. Increase in A., P in mobile phone group was significantly more than in the lecture group |

| Taymoori, Sanandaj, 2015[84] | RCT | Health counselling | Females>50 years | 184 | 55.93 (7.80) | QNR | Intervention/control: Significant_difference in mean HBM and TPB structures and percent mammography |

| Sadeghi, Sirjan, 2015[85] | RCT | BASNEF model-based education | Females 20–40 years attending to HCCs | 200 | Intervention 35.86 (2.53) Control 36.12 (2.24) |

QNR | After/before: K. significantly increased in both groups. A., P., enabling factors increased in Intervention Intervention/control: Significant_difference in mean_scores of KAP, subjective norms, and enabling factors |

| Ghahremani, Shiraz, 2016[86] | RCT | Self-care education | Females referred to HCCs | 168 | Intervention 35.3 (7.5) Control 36.6 (8.5) |

QNR | Intervention/control: Significant_difference in mean_scores of TTM structures and BSE behavior (P<0.001) |

| Mirzaii, Mashhad, 2016[87] | RCT | SHEP-model-based education | All the health volunteers and females covered by two urban health centers | 120 | NA | QNR, C/L | Intervention/control: Significant_difference in mean_scores of A. and BSE (P<0.001) |

| Parsa, Hamedan, 2016[88] | RCT | Educational counselling | Females referred to HCCs | 150 | Intervention 47.64 (7.03) Control 46.6 (8.68) |

QNR, C/L | Intervention/control: Significant_difference in mean_scores of perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, health motivations, K. and BSE practice |

| Khiyali, Fasa, 2017[89] | RCT | HBM-based education | Healthy females | 92 | Intervention 30.39 (8.19) Control 28.23 (7.3) |

QNR | Intervention/control: Significant_difference in mean_scores of K., HBM structures and BSE behavior (P<0.001) |

| Nahidi, Abadeh, 2017[90] | RCT | HBM-based education | Females 30–39 years referred to HCCs | 144 | Intervention 38.5 Control 39.44 |

QNR | Intervention/control: Significant_difference in mean_scores of awareness., perceived susceptibility and performance Significant_difference in mean_score of performance in BSE (P<0.001) |

| Nasiriani, Yazd, 2017[91] | Randomized field-trial | Telephone counseling and education | Females with BC_FH | 90 | Intervention 45.8 (7.51) Control 46.77 (8) |

QNR | Intervention/control: Significant_difference in mammography performing (77.8%/24.4%) After/before: Significant_difference in mammography performing in the intervention group. No significant_difference in mammography performing in the control group |

| Savabi-Esfahani, Baharestan, 2017[92] | RCT | Role-playing, lecture | Females enrolled in community cultural centers | 314 | 45.53 (10.99) | QNR | After/before: Significant_difference in mean_scores of K. about BC and screening in both educational groups Role playgroup/lecture group: Mean_score of K. (94.5/88.8) |

| Shahbazi, Borujen, 2017[93] | RCT | Direct and indirect education | Nursing and midwifery personnel in Valiasr Hospital | 89 | 31.95 (6.57) | QNR | After/before: Significant. increase scores of K., in both groups, A. increased only indirect group Direct training versus indirect training: Significant_difference in K. and A. about BSE |

| Matlabi, Gonabad, 2018[94] | Randomized field-trial | In-person education | Married Females 20–49 years | 140 | 37.27 (6.69) | QNR | Intervention/control (immediately after: Action 21.4% versus 22.9%, P=0.001, maintenance 40% versus 24.3%, P=0.001, 3 months after: Action 25.7% versus 24.3%, P=0.001, maintenance 57.1% versus 24.3%, P=0.001) |

| Ghaffari, Isfahan, 2019[95] | RCT | HBM-based education | Health volunteers of HCCs | 480 | NA | QNR, C/L | Intervention/control: Immediately and two months after: Significant_difference in means of K., HBM structures related to BSE and mammography, BSE skill. No significant_difference in BSE behavior and mammography |

| Ghaffari, Karaj, 2018[96] | RCT | Education based on the integrated behavioral model | Females who were attended to HCCs | 138 | NA | QNR | Intervention/control: Immediately and two months after: Significant_difference in mean_score of K. and all structures except the perceived benefits of mammography and mammography behavior (P<0.001) |

| Masoudiyekta, Dezful, 2018[97] | RCT | HBM-based education | Females 20–59 years referred to HCCs | 226 | 39.75 (9.05) | QNR | Intervention/control: Significant increase rate of BSE and mammography, mean_scores of K. and HBM structures three months after (P<0.001). No significant_difference in the score of CBE |

| Mirmoammadi, Hamadan, 2018[98] | RCT | HBM-based consultation | Females>40 years attending Hamadan HCCs | 150 | Intervention 64.47 (7.3) Control 60.46 (8.8) |

QNR | Intervention/control (significant_difference in mammography: 49.3%/20%, CBE: 52%/28%, mean_scores of K., HBM constructs except for susceptibility and severity) |

| Naserian, Mahshahr, 2018[99] | RCT | Short messages and group training | Females 40–60 years referred to HCCs | 210 | Intervention 48.1 (5.8) Intervention 48.7 (5.8) |

QNR | After/before: Significant. increase in mean_score K. In each group (P=0.001), no significant increase between groups (P=0.061) Group training was better in BSE (P<0.001) SMS group was better in CBE (P=0.02) |

| Mashhod, Tehran, 2018[100] | RCT | HBM-based education | Females referred to HCCs | 94 | Intervention 35 Control 32.5 |

QNR | After/before: Significant_difference in mean_scores of HBM structures except for perceived benefits in the experimental group Intervention/control: Significant_difference in mean_scores o K., HBM structures except for perceived benefits, BSE performance |

| Fathollahi-Dehkordi, Isfahan, 2018[101] | RCT | Health counselling | Females>20 years with BC_FH | 107 | Intervention 36.04 (10.90) Control 35.58 (10.22) |

QNR | Intervention/control: Significant_differencein screening practice. Time factor and time-group interaction affected K.and HBM structures significantly Most females in the action stage of CBE vesrsus in the contemplation stage (P<0.001) |

| Alizadeh Sabeg, Abish Ahmad, 2019[102] | RCT | Health counselling | Females 40–69 years | 60 | Intervention 47.6 (5.7) Control 48.2 (5.8) |

QNR | Intervention/control: Significant_difference in mean_scores of total K. and K. about symptoms, risk factors, age-related and lifetime risk, BC screening, frequency of BSE 2 months after |

| Termeh Zonouzy, Tehran, 2019[103] | RCT | Intervention based on fear appeals using the EPPM model | Females>40 years with no BC_FH | 600 | 53.2 (9.45) | QNR | After/before: Significant_difference in mean_scores of A., behavioral intention in the intervention group Intervention/control: Significant_difference in mean_scores of A., behavioral intention |

| Rokhforouz, Rafsanjan, 2019[104] | RCT | In-person education | Health volunteers working in HCCs in Rafsanjan | 92 | 46.84 (10.67) | QNR, C/L | Intervention/control: Significant_differencef in movement in the stages of change, mean scores of HBM structures except for perceived barriers |

| Molaei-Zardanjani, Isfahan, 2019[105] | RCT | Individual and peer education | Females referred to selected HCCs | 100 | NA | QNR | After/before: Significant improvement in A. toward behavior, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, intention behavior in both groups Mean_score of A. in the individual education group was higher (P<0.05) Mean_score of subjective norms in the peer education group was higher (P<0.05) No significant_difference in mean_scores of perceived behavioral control constructs and behavioral intention between groups (P>0.05) |

CT=Computed tomography; RCT=Randomised clinical trial; HBM=Health belief model; TPB=Theory of planned behavior; BASNEF=Beliefs, attitudes, subjective norms, and enabling factors; SHEP=Systematic comprehensive health education and promotion; EPPM=Extended parallel process model; HCC=Health Care Center; BU=Birjand University; BC_FH=Family history of breast cancer; ZAUMS=Zahedan University of Medical Sciences; TU=Tehran University; QUMS=Qazvin University of Medical Sciences; NA=Not available; QNR=Questionnaire; C/L=Checklist; BSE=Breast self-examination; CBE=Clinical breast examination; KAP=Knowledge/attitude/practice; BC=Breast cancer; TTM=Transtheoretical model; SMS=Short Message Service

The statistical indicators of BC screening

This category includes the results of statistical studies in the field of BC prevention Table 3. Seventeen studies with different designs consisting of cross-sectional (13 articles), clinical trial (1 article), field trial (1 article), longitudinal (1 article), and cost-effectiveness (1 article) were included in this subgroup. The majority of participants were females referred to HCCs. Some studies had presented the psychometric assessment of the Persian version of BSE Behavior Predicting Scale, BC awareness measure, and Champion HBM Scale. The development of some tools in BC prevention strategies consisted of MSS (Mammography Social Support scale in Iran), BC screening chart, and ASSISTS instrument and model. In two studies, the response rate to BSE and CBE ranged from 81% to 100%.[100,106] The participation rate in the screening program was reported from 3.8% to 16.8% in two studies.[52,107] BC detection rate has been reported in some studies with different designs. In a cross-sectional study on females admitted to the mammography center in a hospital, BC was detected in 2.3% of 526 screened patients.[107] BC detection rate of non-diagnostic mammography in 9395 subjects was 8.5 per 1000 mammography.[108] In BC screening of 26606 females, the detection rate of 24 per100000 was reported in CBE and mammography evaluation; the false-positive detection rate of mammography was 7.5% in this screening program.[109] Sehhati Shafaie conducted a project on 5,000 females referred to BC hospital for screening. They recorded 996 sonography and 636 mammography reports with 40 and 183 abnormal cases, respectively, and found one BC by performing 14 fine needle aspiration (FNA).[110] The screening mammography, diagnostic sonography, biopsy, and abnormality rates were 27.4%, 26%, 1.4%, and 33% in a screening project, respectively.[107] Results of a study indicated that the mean scores of females’ BC screening belief and multidimensional health locus of control were 40.72 ± 10.41 and 67.78 ± 17.67, respectively.[111]

Table 3.

The statistical indicators of breast cancer screening

| First author/city/year of publication | Study design | Study population | Sample size | Mean age (SD) | Reported index | The most important findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taymoori, Sanandaj, 2009[112] | Cross-sectional | Employed females in governmental institutes and departments | 606 | 37.08 (9.81) | Instrument | Developing and validating CHBMS to assess Iranian females’ beliefs related to BC and screening |

| Barfar, 10 cities of Iran, 2014[109] | Cost-effectiveness | Females >35 years | 26,606 | NA | Detection rate | Detection rate: 24 per 100,000 The cost per cancer detected:$15,742 False-positive detection rate: 7.5% |

| Miller, Yazd, 2015[106] | Field-trial | Females residing in urban areas | 12,602 | NA | Response rate to BSE + CBE screening of BC | Response rate: Data collection at patients’ homes in both groups: 100% Visiting HCC in the intervention group: 84.5% |

| Jafari, Kerman, 2015[106] | Cross-sectional | Females 35-69 years | 15,794 | NA | Participation rate | Participation rate: Urban region 3.8%, villages and towns 16.34% |

| Saghatchi, Zanjan, 2015[107] | Cross-sectional | Females admitted to the mammography center of Mousavi Hospital | 526 | 44.3 | Detection rate Abnormality rate |

Screening mammography rate: 27.4% Diagnostic sonography rate: 26% Biopsy rate: 1.4% Detection rate: 2.3% Abnormality rate: 33% |

| Khazaee_Pool, Tehran, 2016[113] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to TUMS HCCs | 585 | 41.25 (6.34) | Instrument | Developing and validating an instrument to identify factors affecting females’ BC prevention behaviors named ASSISTS |

| Aminisani, Baneh, 2016[52] | Cross-sectional | Females >40 years referred to HCCs | 561 | 43.64 (5.17) | Participation rate | Participation rate in mammography program: 16.8% The lowest level of participation: Females >60 years, illiterate, postmenopausal |

| Shafaie, Tabriz, 2016[110] | Cross-sectional | Females referred for screening to BC clinic of Behbood Hospital | 5000 | 37.45 (10.81) | Abnormal finding rate | After CBE: 759 abnormal cases After 996 sonography: 40 abnormal cases After 636 mammography: 183 abnormal cases After 14 FNA: One cancer case (7.1%) |

| Moshki, Sanandaj, 2017[114] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to HCCs in Sanandaj | 482 | 47.35 (9.8) | Instrument | A valid instrument for mammography self-efficacy and fear of BC scales in Iranian women |

| Alikhassi, Tehran, 2017[108] | Longitudinal | Females referred to a university hospital | 9395 | 49.84 (9.19) | Recall rate, detection rate of opportunistic screening mammography | Recall rate: total: 24.7%, first mammography: 29%, subsequent Mammography: 22%, micro-calcification: 21.1%, mass: 49.3%, distortion: 34.8%, asymmetry: 48.1% Cancer detection rate: 8.5 per 1000 mammography |

| Poorolajal, Tehran, 2018[115] | Cross-sectional | Native Iranian women | 1422 | Intervention 48.37 (10.79) Control 42.37 (9.84) |

Instrument | Age alone is not a strong predictor of BC The chart: facilitates making decisions on the threshold for recommending screening mammography, detects high-risk individuals |

| Khazaee_Pool, Sanandaj, 2018[116] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to HCCs in Sanandaj | 434 | 48.12 (8.91) | Instrument | Response rate: 91% A valid instrument: MSS |

| Pourhaji, Tehran, 2018[117] | Cross-sectional | Females >40 years referred to HCCs of SBMU | 200 | Median (45.6) | Model | A valid instrument: BSEBPS |

| Heidari, Isfahan, 2018[118] | Cross-sectional | Persian language females | 1078 | 36.5 (11.65) | Instrument | Transcultural adaptation and validation of an instrument: BCAM |

| Fathollahi_Dehkord, Isfahan, 2018[101] | Clinical-trial | Females with a BC_FH | 98 | Intervention 36.04 (10.90) Control 35.58 (10.22) |

Response rate to CBE screening | Response rate: 81% |

| Khazaee-Pool, Tehran, 2018[119] | Cross-sectional | Females 30-75 years referred to HCCs of TUMS | 260 | 45.12 (5.92) | Model | Seven constructs of model: Perceived social support, attitude, motivation, self-efficacy, information seeking, stress management, self-care A, motivation, self-efficacy, information seeking, social support influence self-care behavior and stress management |

| Saei Ghare Naz, Tehran, 2019[111] | Cross-sectional | Females referred to HCCs of SBMU | 325 | 34.82 (11.73) | BCSB and MHLC score | BCSB: 40.72±10.41 MHLC: 67.78±17.67 |

SD=Standard deviation; TUMS=Tehran University of Medical Sciences; HCC=Health Care Center; BC=Breast cancer; SBMU=Shahid Beheshti Medical University; BC_FH=Family history of breast cancer; BSE=Breast self-examination; CBE=Clinical breast examination; NA=Not available; BCSB=Breast cancer screening belief; MHLC=Multidimensional health locus of control; CHBMS=Champion Health Belief Model Scale; FNA=Fine-needle aspiration; MSS=Mammography social support; BSEBPS=Breast Self-Examination Behavior Predicting Scale; BCAM=Breast cancer awareness measure

DISCUSSION

This paper reviewed the status of BC screening strategies and indicators in Iran. The studies were assessed and discussed in three themes of observational studies, interventional studies, and statistic indicators as follows:

Observational studies of BC screening

At this time, mammography is the gold standard of the BC early detection method. Hence, it is necessary to specify the status of mammography performance in Iran. In the current study, the range of performing of mammography between 2005 and 2020 was 1.3%–45%, while in a systematic review assessing Persian language articles of two databases between 2001 and 2010, 3%–26% of Iranian females had done mammography screening.[12] Although a study showed that the rate of screening mammography in Iran was lower than in developed countries such as the USA and the UK,[52] the results of a screening program in Saudi Arabia resulted in 27.7% of mammography achievement.[120] One of the reasons for this difference may be the lack of a BC screening program in Iran; hence, the results reported were extracted from various limited studies with high heterogeneity regarding the study population, sample size, and design. On the other hand, some research has revealed that mammography is an expensive modality and not a cost-effective method for BC screening in Iran.[6,109] Further, studies focusing on other screen methods are suggested.

BSE and CBE are considered as more available, low-cost, and low-technical requirement screening strategies. This study showed that the performance of BSE and CBE ranged between 0%–79.4% and 4.1%–41.1%, respectively, and 30.9%–60% of females did not have appropriate skills to do BSE. Similar to our results, a study on Arab females demonstrated that 69% of subjects did not know how to do BSE.[121] According to the current review, the low self-efficacy of females in applying screening behaviors may affect BSE achievement.[44] Self-efficacy is one of the most important predictors of screening behaviors,[43,44,46,47] and the performance of BSE in females with higher self-efficacy is 1.17 times more than others.[35] Therefore, it can be concluded that by improving females’ self-efficacy, their skills in screening behaviors will also improve. Hence, education about BC screening methods is worthy of being insisted on by the health system. It may be a more logical strategy for low- and middle-income countries in which breast awareness is more beneficial, too. In conclusion, since there is no national study to demonstrate accurate indicators, most of the current results have been reported from small and limited studies, which cause a wide range of affectivity. It seems that more accurate epidemiologic studies are necessary to indicate the frequency of BSE and CBE achievement in Iranian women.

Effect of educational interventions on screening behavior

The effect of various educational modalities on screening behaviors has been studied in different Iranian researches. The in-person method was used by most studies, except for two studies that used telephone counseling. Most of them showed that education effectively enhanced females’ knowledge, attitude, practice of screening behaviors. Still, no study compared in-person with virtual education to reveal which method is more effective in Iran. Given the growth of using the Internet, novel technologies such s online social networks, smartphone applications, and virtual learning can be cost-effective. Some features of this technology, such as more availability, low_price, and offering a more attractive platform, make it a helpful modality for future research studies.

In this scoping review, most educational interventions resulted in satisfied effects.[70,73,76,77] It may show that the health system's educational modalities for BC prevention are more important than the training methods. Selecting a suitable educational method facilitates access to defined objectives, and it depends on many factors, such as socioeconomic status, health priorities, and cancer preventive policies.[122] If early detection of BC is a priority of the health system of Iran, indeed, education programs should be organized as one of the essential correlated factors. On the other hand, promoting the population's awareness induces some diagnostic and treatment demands for BC detection. If we do not provide needed requirements, our health policy goal won’t be reached. Related studies in Iran have focused on identifying the educational needs of the specified Iranian population with different races, cultures, incomes, etc.[77,79,82,84,95,96] Hence, they cannot be generalized to the total population of Iran. Thus, implementing national research with a more potent methodology and stratified demographic characteristics is suggested.

The statistical indicators of BC screening

The statistical indicators are one of the most important principles for health policymaking to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of an intervention. They include abnormal rate, detection rate, recall rate, participation rate, etc.[123] The BC detection rate in three studies was reported with a different study population. In one of the studies achieved in Zanjan, a city of Iran, 526 women admitted to the mammography center were assessed. The detection rate had been reported by 2.3% of 526 screened patients.[107] Another research was conducted at a tertiary referral university hospital, and 9395 digital mammographies were performed, and they detected 8.5 cancer patients in 1000 women who underwent nondiagnostic mammography.[108] The third study was conducted in ten cities of Iran in which over 26,000 women aged 35 and higher with low socioeconomic status were evaluated. The results showed a detection rate of 24 per 100000 females.[109] Although all three studies have reported a detection rate, differences in methodology make them non-integral. The detection rates of invasive BC based on accurate population screening are targeted at >0.5, ≥2.7, and ≥5 per 1000 screens in Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia, respectively. Also, the detection rates for in situ BC in the United Kingdom and Australia are considered ≥0.4 and ≥1.2 per 1000 screens, respectively.[123] The detection rate in Iran has been reported higher than in European countries and even higher than 2.7 in Asian counterpart countries.[124] One of the reasons for this difference is how females were evaluated, which means the reported statistics indicators in Iran were not extracted from a national study and some of them are just the result of limited research in a specific population. The studied population, the recruited sample size, or study design can affect these indices. On the other hand, the limitation of detection rates estimation factors like workforce skill, sensitivity or specificity of equipment, and essential resources have not been appropriately assessed in Iranian studies. Hence, it seems that the evaluation of screening effectiveness in randomized controlled clinical trials at the national level is necessary to reach more accurate information.

Another statistic indicator is the abnormal call rate, which is vital to assessing mammography image quality and interoperation. It is defined as a percentage of abnormal mammography per number of screens.[123] In Iran, it has been reported 28.77% and 33%.[107,110] The abnormal call rate for the initial screen in Europe is considered <7, and in all of the countries like Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand are considered <10.[123] This indicator is related to the recall rate. Recall rate indicates if screening mammography resulted in a recommendation for further imaging or surgical/clinical visit because of an abnormality on the screening exam.[125] The European Guidelines and the American College of Radiology considered recall rates <7% and <10%, respectively, as acceptable recall rates.[125] A high abnormal rate induces a high recall rate and increases unnecessary tests and false positives results.[123] According to our result, the recall rate in Iran was 24.7% in total, and for the first and subsequent mammography was 29% and 22%, respectively.[113] Similar to the previously reported indices, the abnormal call rate and recall rate in Iran has not been extracted from a national screening study. As a result, to determine whether our country needs a BC screening program or not, these indicators must be estimated in the standard and targeted studies, and it is beneficial to be considered as a research priority in the health policy system of Iran.

The participation rate represents the percentage of people who participate in a screening program and can be affected by acceptability, accessibility, promotion of screening, and the capacity of the plan.[123] This index showed 16.8%, 20% in urban areas, and 10% in rural areas of Iran.[52,107] The participation rate in screening mammography in Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand is estimated at ≥70%. The comparison between statistics shows a low participation rate among Iranian women, which can have consequences such as reducing the cost-effectiveness of screening programs. It may be due to the low level of awareness in Iranian females, which impacts their attitude toward the importance of BC prevention. Females’ attitudes can be reformed by cooperating with mass media such as radio, television, or social networks with the health system.

On the other hand, most of the screening costs are paid by patients themselves and may affect their acceptability of some screening strategies and lowers this index compared to the other countries. Some studies have shown that mammography screening is not a cost-effective intervention in Iran.[6,109] Hence, most insurances support the cost of diagnostic modalities, and the screening tests should be paid out of pocket. Proving more insurance coverage or accessibility facilities by the health system of Iran can improve the participation rate index.

In this review, we did not find any study for evaluating the BSE or CBE cost-effectiveness in the Iranian population. Considering the importance of those screening methods in limited resources countries, establishing a comparative analysis will provide helpful evidence for policy-makers for early detection of BC in Iran.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This scoping review demonstrated that we have many unknown facts about BC early detection in Iran. It is not clear which strategy is the best. Establishing the national level studies with a standard framework may present screening indices more accurately.

Implications of the findings for research

The necessity of a national screening program in a country with a low incidence of BC, presenting a proper educational method for increasing women's awareness, and estimating screening indices can be the priorities of future Iranian researches.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was a part of a comprehensive project to review the different aspects of breast cancer in Iran. A grant from Roche Company funded the leading research.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The researchers at the Breast Cancer Research Center appreciate the financial support of Roche Company for the development of this valuable breast cancer road map which facilitates future researches in Iran. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

APPENDIX 1: SEARCH STRATEGY

Details of data sources and methodology of the big project between 2005-2015 time horizon have been presented in another article (13). The same methodology was extended to articles published up to 2020. The current study consists of all articles published from January 2005 to 2020. English online electronic databases of Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus, and Persian databases of SID and IranMedex were used. English search formula was “BC” OR “breast carcinoma” OR “breast tumor” OR “breast neoplasm” AND Iran. Persian search formula was a combination of Iran with the words of  Breast tumor, BC, Breast carcinoma, and Breast neoplasm.

Breast tumor, BC, Breast carcinoma, and Breast neoplasm.

APPENDIX 2

After reviewing the title, 522 items (225 English and 297 Persian) were included by deleting unrelated studies and duplicated titles, abstracts, and full text of articles. The results of 246 articles in the field of screening strategies and indicators were considered eligible for this review. After assessing full texts, 136 articles were excluded, and 110 studies consisting of 81 English and 29 Persian were evaluated.

Reasons of exclusion were irrelevancy (53 articles), just abstract presentation (7 articles), no relation to Iran population (8 articles), letter to editor (3 articles), review article (2 articles), BC population study (4 articles), inaccessible full paper (1 article), qualitative study (3 articles), and duplication (55 articles).

| Prisma Checklist | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Section | Item | Prisma-ScR checklist item | Reported on page# |

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review | 1 |

| Abstract | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): Background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives | 1 |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach | 2 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives | 3 |

| Methods | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number | NA |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale | 3 |

| Information sources* | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed | 4 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated | 4 |

| Selection of sources of evidence† | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review | 4 |

| Data charting process‡ | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators | 7 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made | 5 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence¦ | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate) | NA |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted | 5,6 |

| Results | |||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram | 8 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations | 8 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12) | NA |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives | 10–22 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives | 10–22 |

| Discussion | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups | 23–27 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process | NA |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps | 28 |

| Funding | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review | 30 |

NA=Not available

REFERENCES

- 1.Gupta A, Shridhar K, Dhillon PK. A review of breast cancer awareness among women in India: Cancer literate or awareness deficit? Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:2058–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Office, CDC of Iran Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Cancer Registration Report. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mousavi SM, Montazeri A, Mohagheghi MA, Jarrahi AM, Harirchi I, Najafi M, et al. Breast cancer in Iran: An epidemiological review. Breast J. 2007;13:383–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2007.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyskens FL, Jr, Mukhtar H, Rock CL, Cuzick J, Kensler TW, Yang CS, et al. Cancer prevention: Obstacles, challenges and the road ahead. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108:djv309. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutnik LA, Matanje-Mwagomba B, Msosa V, Mzumara S, Khondowe B, Moses A, et al. Breast cancer screening in low- and middle-income countries: A perspective from Malawi. J Glob Oncol. 2016;2:4–8. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2015.000430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haghighat S, Akbari ME, Yavari P, Javanbakht M, Ghaffari S. Cost-effectiveness of three rounds of mammography breast cancer screening in Iranian women. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2016;9:e5443. doi: 10.17795/ijcp-5443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bashirian S, Mohammadi Y, Barati M, Moaddabshoar L, Dogonchi M. Effectiveness of the theory-based educational interventions on screening of breast cancer in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2020;40:219–36. doi: 10.1177/0272684X19862148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dewi TK, Massar K, Ruiter RA, Leonardi T. Determinants of breast self-examination practice among women in Surabaya, Indonesia: an application of the health belief model. BMC public health. 2019;19:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7951-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pirzadeh A. Application of the health belief model in breast self-examination by Iranian female university students. Int J Cancer Manage. 2018;11:e7706. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simi A, Yadollahie M, Habibzadeh F. Knowledge and attitudes of breast self examination in a group of women in Shiraz, Southern Iran. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:283–7. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.072678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yadollahie M, Simi A, Habibzadeh F, Ghashghaiee RT, Karimi S, Behzadi P, et al. Knowledge of and attitudes toward breast self-examination in Iranian women: A multi-center study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1917–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naghibi SA, Shojaizadeh D, Yazdani Cherati J, Montazeri A. Breast cancer preventive behaviors among Iranian women: A systematic review. Payesh. 2015;14:181–91. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khosravi N, Nazeri N, Farajivafa V, Olfatbakhsh A, Atashi A, Koosha M, et al. Supportive care of breast cancer patients in Iran: A systematic review. Int J Cancer Manage. 2019;12:e83255. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bahrami M, Taymoori P, Bahrami A, Farazi E, Farhadifar F. The prevalence of breast and cervical cancer screening and related factors in woman who refereeing to health center of Sanandaj city in 2014. Zanko J Med Sci. 2015;16:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moghaddam Tabrizi F, Vahdati S, Khanahmadi S, Barjasteh S. Determinants of breast cancer screening by mammography in women referred to health centers of Urmia, Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19:997. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.4.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tavakoliyan L, Bonyadi F, Malekkzadeh E. The investigation of factors associated with breast cancer screening among Kazeroon women aged 20-65 in 2013. Nurs Vulnerable J. 2015;1:17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vahedian Shahroodi M, Pourhaje F, Esmaily H, Pourhaje F. The relationship between breast self-examination and stages of change model in health volunteers. J Res Health. 2015;5:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nikpour M, Hajian-Tilaki K, Bakhtiari A. Risk assessment for breast cancer development and its clinical impact on screening performance in Iranian women. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:10073–82. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S229585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valizadeh S, Akbari N, Seyyed Rasuli A. Health beliefs of nurses about breast self examination. J Med Sci. 2006;6:743–50. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aghababaii S, Bashirian S. Nursing and midwifery students breast shelf examination knowledge and practice. Int J Cancer Res. 2006;2:98–101. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbaszadeh A, Haghdoost AA, Taebi M, Kohan S. The relationship between women's health beliefs and their participation in screening mammography. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8:471–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heidari Z, Mahmoudzadeh-Sagheb HR, Sakhavar N. Breast cancer screening knowledge and practice among women in southeast of Iran. Acta Med Iran. 2008;46:321–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khalili AF, Shahnazi M. Breast cancer screening (breast self-examination, clinical breast exam, and mammography) in women referred to health centers in Tabriz, Iran. Indian J Med Sci. 2010;64:149–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salimi Pormehr S, Kariman N, Sheykhan Z, Alavi Majd H. Investigation of breast cancer screening tests performance and affecting factors in women referred to Ardebil's health and medical centers, 2009. J Ardabil Univ Med Sci. 2010;10:310–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alavi G, Hoseininejad J, Masoom AS, Shakeri MT. Evaluation of prevalence of cervical and breast cancer screening programs between gynecologists. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2010;13:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sultan Ahmadi J, Abbas Zadeh A, Tirgari B. A survey on the rate and causes of women's participation or nonparticipation in breast and cervical cancers screening programs. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2010;13:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noroozi A, Tahmasebi R. Factors influencing breast cancer screening behavior among Iranian women. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1239–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasani L, Aghamolaei T, Tavafian SS, Zare S. Constructs of the health belief model as predicting factors in breast self-examination. Hayat. 2011;17:62–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samah AA, Ahmadian M. Socio-demographic correlates of participation in mammography: A survey among women aged between 35-69 in Tehran, Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:2717–20. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.6.2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harirchi I, Azary S, Montazeri A, Mousavi SM, Sedighi Z, Keshtmand G, et al. Literacy and breast cancer prevention: A population-based study from Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:3927–30. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.8.3927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aflakseir A, Abbasi P. Health beliefs as predictors of breast cancer screening behaviour in a group of female employees in Shiraz. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2012;5:124–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moodi M, Rezaeian M, Mostafavi F, Sharifirad GR. Determinants of mammography screening behavior in Iranian women: A population-based study. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:750–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadivar M, Joolaee S, Joulaee A, Bahrani N, Hosseini N. Breast cancer knowledge, attitudes and screening behaviors in two groups of Iranian women: Physicians and non-health care personnel. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27:770–3. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fouladi N, Pourfarzi F, Mazaheri E, Asl HA, Rezaie M, Amani F, et al. Beliefs and behaviors of breast cancer screening in women referring to health care centers in northwest Iran according to the champion health belief model scale. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:6857–62. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.11.6857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pirasteh A, Khajavi Shojaie K, Kholdi N, Davati A. Stages of change and predicting of self efficacy construct in breast self examination behavior among women attending at tehran health centers, Iran, 2011. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2013;16:16–23. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asgharnia M, Faraji R, Zahiri Z, Salamat F, Mosavi Chahardah SM, Sefati S. A study of knowledge and practice of woman about breast cancer and its screening, in the case of women who referred to Alzahra hospital in Rasht during 2010-2011. Iran J Surg. 2013;21 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akhtari-Zavare M, Ghanbari-Baghestan A, Latiff LA, Matinnia N, Hoseini M. Knowledge of breast cancer and breast self-examination practice among Iranian women in Hamedan, Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:6531–4. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.16.6531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hajian-Tilaki K, Auladi S. Health belief model and practice of breast self-examination and breast cancer screening in Iranian women. Breast Cancer. 2014;21:429–34. doi: 10.1007/s12282-012-0409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mokhtary L, Khorami Markani A. Health beliefs and breast cancer early detection behaviors among health care providers in Tabriz Healthcare Centers, Iran. Basic and Clinical Cancer Research. 2014;6:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nojomi M, Namiranian N, Myers RE, Razavi-Ratki SK, Alborzi F. Factors associated with breast cancer screening decision stage among women in Tehran, Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:196–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shiryazdi SM, Kholasehzadeh G, Neamatzadeh H, Kargar S. Health beliefs and breast cancer screening behaviors among Iranian female health workers. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:9817–22. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.22.9817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghodsi Z, Hojjatoleslami S. Breast self examination and mammography in cancer screening: Women health protective behavior. J Prev Med Hyg. 2014;55:46–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taymoori P, Habibi S. Application of a health belief model for explaining mammography behavior by using structural equation model in women in Sanandaj. Sci J Kurdistan Univ Med Sci. 2014;19:103–15. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Momenyan S, Rangraz Jedi M, Sanei Irani F, Adibi Garakhani Z, Sarvi F. Prediction of breast self-examination in a sample of nursing and midwifery students Qom city using health belief model, Iran. Qom Univ Med Sci J. 2014;8:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahmadipour H, Sheikhizade S. Breast and cervical cancer screening in women referred to urban healthcare centers in Kerman, Iran, 2015. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:143–7. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.s3.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jouybari TA, Mahboubi M, Barati M, Aghaei A, Negintaji A, Karami-Matin B. Mammography among Iranian women's: The role of social support and general self-efficacy. Int J Trop Med. 2016;11:50–4. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tahmasebi R, Noroozi A. Is health locus of control a modifying factor in the health belief model for prediction of breast self-examination? Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:2229–33. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.4.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moshki M, Taymoori P, Khodamoradi S, Roshani D. Relationship between perceived risk and physician recommendation and repeat mammography in the female population in Tehran, Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:161–6. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.s3.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mirzaei-Alavijeh M, Heydari ST, Ahmadi-Jouybari T, Jalilian F, Gharibnavaz H, Mahboubi M. Socio-demographic and cognitive determinants of breast cancer screening. Int J Adv Biotechnol Res. 2016;7:1684–90. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naghibi A, Jamshidi P, Yazdani J, Rostami F. Identification of factors associated with breast cancer screening based on the PEN-3 model among female school teachers in Kermanshah. Iran J Health Educ Health Promot. 2016;4:58–64. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ghahramanian A, Rahmani A, Aghazadeh AM, Mehr LE. Relationships of fear of breast cancer and Fatalism with screening behavior in women referred to health centers of Tabriz in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:4427–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aminisani N, Fattahpour R, Dastgiri S, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Allahverdipour H. Determinants of breast cancer screening uptake in Kurdish women of Iran. Health Promot Perspect. 2016;6:42–6. doi: 10.15171/hpp.2016.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Farajzadegan Z, Fathollahi-Dehkordi F, Hematti S, Sirous R, Tavakoli N, Rouzbahani R. The transtheoretical model, health belief model, and breast cancer screening among Iranian women with a family history of breast cancer. J Res Med Sci. 2016;21:122. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.193513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shirzadi S, Nadrian H, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Allahverdipour H, Hassankhani H. Determinants of mammography adoption among Iranian women: What are the differences in the cognitive factors by the stages of test adoption? Health Care Women Int. 2017;38:956–70. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2017.1338705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anbari K, Ahmadi SA, Baharvand P, Sahraei N. Investigation of breast cancer screening among the women of Khorramabad (west of Iran): A cross-sectional study. Epidemiol Biostat Public Health. 2017;14:e12099–1. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saadat M, Ghalehtaki R, Baikpour M, Sadeghian D, Meysamie A, Kaviani A. The participation rate and contributing factors of screening mammography among (capitalize) female faculty physicians in Tehran, Iran. Int J Cancer Manage. 2017;10:e8016. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neinavae M, Soltani HR, Soltani N. The relationship between breast self-examination (BSE) awareness and demographic factors in women health management. The Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility. 2017;20:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farzaneh E, Heydari H, Shekarchi AA, Kamran A. Breast and cervical cancer-screening uptake among females in Ardabil, Northwest Iran: A community-based study. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:985–92. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S125344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miri M, Moodi M, Miri MR, Sharifzadeh G, Eshaghi S. Breast self-examination stages of change and related factors among Iranian housewives women. J Health Sci Technol. 2017;1:41–8. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Monfared A, Ghanbari A, Jansar Hosseini L, Norozi N. Status of screening by mammography and its related factors in the general population of women in Rasht. Iran J Nurs. 2017;30:32–41. [Google Scholar]