Abstract

While the swift development and production of a COVID-19 vaccine has been a remarkable success, it is equally crucial to ensure that the vaccine is allocated and distributed in a timely and efficient manner. Prior research on pandemic supply chain has not fully incorporated the underlying factors and constraints in designing a vaccine allocation model. This study proposes an innovative vaccine allocation model to contain the spread of infectious diseases incorporating key contributing factors to the risk of uninoculated people including susceptibility rate and exposure risk. Analyses of the data collected from the state of Victoria in Australia show that a vaccine allocation model can deliver a superior performance in minimizing the risk of unvaccinated people when a multi-period approach is employed and augmenting operational mechanisms including transshipment between medical centers, capacity sharing, and mobile units being integrated into the vaccine allocation model.

Keywords: Vaccine supply chain, Allocation models, Multi-period decision making, COVID-19 pandemic, Capacity sharing, Mobile units

1. Introduction

An epidemic is defined as a widespread occurrence of an infectious disease within a population or a country, while a pandemic is an epidemic that spreads beyond a population and a country’s borders. In a pandemic the countries’ health systems become overloaded. Limited production, transport, and storage capacity of vaccines increase the complexity of the vaccine supply chain which may result in ineffective delivery of vaccines to the right place at the right time (Fineberg, 2014). As of August 2021, worldwide 200 million COVID-19 cases and 4.3 million deaths have been reported (WHO, 2021a). In addition to such as a dramatic loss of human lives, the pandemic has caused much economic devastation and social disruption as well (Ali and Alharbi, 2020, Lima et al., 2020, Ozili and Arun, 2020, Carlsson-Szlezak et al., 2020). According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2020), the COVID-19 pandemic is the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression.

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2021c) defines vaccination as a simple, safe, and effective way to protect people against harmful disease before they come into contact with them. However, the world is now suffering from a shortfall of vaccine production capacity and effective strategies for allocating and distributing vaccines. At the time of writing this article, less than 10 percent of the world’s population have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19 (WHO, 2021a). With limited capacity of vaccine production there will be a long way to go to inoculate the remaining 7.1 billion people. The above discussion emphasizes the vital role that supply chains will play to mitigate the devastating effects of such pandemics.

Studies have been conducted to design an effective and efficient vaccine allocation and distribution network (Buccieri and Gaetz, 2013, Abbasi et al., 2020, Chen et al., 2020, Goldstein et al., 2012, Mamani et al., 2013, Araz et al., 2012, Ramirez-Nafarrate et al., 2015, Emu et al., 2021, Enayati and Özaltın, 2020). In most studies, the underlying factors in allocation and distribution network are considered individually. For example, a vital decision in vaccine allocation is prioritization of who is to be inoculated. Past studies use aspects of susceptibility to infectious diseases such as age (Chen et al., 2020, Foy et al., 2021) and medical history (Rao and Brandeau, 2021, Govindan et al., 2020) to prioritize individuals to receive a vaccine. As well as susceptibility, it is also important to note that geographic characteristics play an important role in any vaccine allocation decision (Yarmand et al., 2014). For example, areas with high population density have high levels of exposure to infectious diseases. Hence, due to the important role of both susceptibility rate and exposure risk, they should be simultaneously integrated in any vaccine allocation modeling.

A significant amount of studies on vaccine allocation is based on a single-period model (Abbasi et al., 2020, Schulte and Pibernik, 2016, Rao and Brandeau, 2021, Ekici et al., 2014). In a single-period allocation model, at the end of each period the excess vaccines would be returned to the distribution centers (DCs) if there is no unmet demand in medical centers (MCs) or transshipment capacity between MCs is already full. Furthermore, in a single-period allocation model the optimization decisions are based on each individual period ignoring the demand and resource capacities in future periods. This would result in sub-optimal solutions. In multi-period allocation model there is an opportunity to use the oversupplied vaccine to meet the demand of other MCs and achieve a more effective resource utilization rate than simply return them to the DCs. As highlighted recently by Choi (2021), examining risk in a multiple-period setting is more realistic and at the same time help researchers deal better with the dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic. This would help the model to further reduce any residual risk of the unvaccinated population and significantly decrease the actual administrative horizon.

Another area which needs further research is the replenishment policy used in distribution centers as it can improve the vaccine administration process (Azadi et al., 2020). Abbasi et al. (2020) used a base-stock level policy in which a fixed level of vaccine supply became available in each period. Based on this policy, the returned vaccine units to DC are disregarded in each period, whereas we propose an allocation model in which the returned vaccines can be considered in future allocation decisions. In the single-period vaccine allocation, particularly when supply would be greater than total demand, it is quite possible to have significant amount of unmet demand in a number of medical centers while other MCs have excess vaccine supplies. Such a situation becomes more prevalent at the later stages of vaccine administration in which the likelihood of having MCs with zero or high demand would increase. This scenario leads to inefficiencies in the vaccine allocation model. To deal with such inefficiencies, cooperation and capacity sharing mechanism should be considered in a vaccine allocation model. Through such mechanisms under-utilized MCs would be able to offer their capacities to the MCs experiencing high demand. The mechanism provides the opportunity of redistributing the demand among eligible adjacent medical centers, which ultimately improves the allocation model’ overall efficiency.

The spread of infectious deceases is dynamic and nonlinear in nature, because the infection rate is simply a product of the number of infected and uninfected people in a region. Consequently, the demand for vaccines in each period changes rapidly and in such circumstances, health authorities aim to employ all possible means and strategies to enhance the efficiency of vaccination operations. Research shows that mobile vaccination facilities can effectively cover larger regions compared to stationary vaccination sites (Halper and Raghavan, 2011). The role of mobile vaccination units become more prominent in remote regions, dense urban areas, and regions with highly dispersed populations (Halper and Raghavan, 2011, Muckstadt et al., 2021). While the majority of research on vaccine distribution uses stationary vaccine distribution units, we argue that mobile units should be included in a vaccine allocation model to diminish bottlenecks caused by the capacity constraints.

In this paper, the lack of a holistic approach to the vaccine supply chain motivates us to propose a more comprehensive vaccine allocation model incorporating multi-period allocation, transshipment between MCs, capacity sharing and mobile units. We develop a mathematical model that minimizes the total risk of unvaccinated population taking into account both susceptibility rate and exposure risk to categorize the priority groups. Various parameters including the availability of vaccine packs and pack sizes, capacities of MCs, mobile units, and transshipment network are used for improving the allocation decisions.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of relevant analyses on vaccine allocation and distribution. Section 3 discusses how the proposed vaccine allocation systems work. Section 4 presents the mathematical model along with the solution approach which integrates a multi-period model with capacity sharing, cooperation and mobile units. The state of Victoria in Australia serves as the case study for this research in Section 5. Followed by the discussion of the findings in Section 6, Section 7 concludes the paper and addresses future research opportunities.

2. Literature review

While developing new vaccines in recent decades has been a significant achievement, vaccine supply chain-related issues such as shipping, storing and distributing vaccines effectively continue to be major challenges for health authorities (Yang et al., 2021, Emu et al., 2021). Pandemics are different from a typical disruption in supply chains in terms of the scope (global vs local) and in terms of dramatic shifts in demand and supply. Pandemic vaccine supply chains and typical vaccine supply chains share a number of features; however, the main difference between the two is the fact that in a pandemic vaccine supply chain, governments procure vaccines from manufacturers to ensure people have quick and equitable access to vaccines. As Duijzer et al. (2018) suggested, a vaccine supply chain has four main components and these are product, production, allocation, and distribution. These components hold true in a pandemic vaccine supply chain as well. In the product stage the important questions to ask are: firstly, which vaccine should be selected?; and secondly, what is the combination of virus strains in a vaccine? (Wu et al., 2005, Robbins et al., 2014). In production stage the quantity and the timing of the vaccine production are determined and this stage is also characterized by vaccine pricing strategies (Kazaz et al., 2016, Cho and Tang, 2013, Eskandarzadeh et al., 2016) and supplier selection decisions (Niu et al., 2020, Federgruen and Yang, 2008). The production stage is a long process and yield uncertainties are inevitable which is the main reason for insufficient vaccine supplies in the market.

The first two components of the vaccine supply chain proposed by Duijzer et al. (2018) are mainly the focus of health and manufacturing domains, respectively. Our paper sits at the intersection of allocation and distribution components at the operational level given the fact that the proposed model incorporates allocation component. This is characterized by allocating vaccines to medical centers and distribution component through capacity sharing and transshipment by mobile units. Due to the fact that many countries have already begun inoculating their citizens using approved vaccines, the need to optimally allocate and distribute the produced vaccines becomes an urgent necessity. Having said that, and due to the importance of these two components of the vaccines supply chain, they are discussed separately in the following sections.

ABS-AJG 2021 ranking was used to extract high quality and high relevant journal articles (Chartered Association of Business Schools, 2021). ABS-AJG provides researchers with access to high quality research. All journals with the rankings 3, 4, and 4* on the topics ‘Operations and Technology Management’ and ‘Operations Research and Management Science’ were identified. In addition to the above list, the transportation research journals (Parts A, B, D and E) were included. This guarantees the focus is on the top quality journals that cover logistics and transportation operations. In the next step, keywords, namely ‘vaccine’, ‘vaccination’, ‘pandemic’, and ’COVID-19’ were deployed to search relevant information in the title and article keywords for studies published in the last 20 years (2002–2021) in Scopus database. The final chosen articles appear in Table 1, Table 2.

Table 1.

Literature review on the allocation stage of the vaccine supply chain.

| Authors | Objectives | Research method |

Priority groups |

Variables | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buccieri and Gaetz (2013) | Using the utility principle and the equity principle to allocate the vaccine to certain people | Surveys and interviews | Homeless and Underhoused Individuals | Epidemiology of the spread of disease, demographic factors, fear of infection, lack of concern, access to community-based clinics, access to a regular doctor, promotional campaign | Prioritizing homeless individuals meets both utility and equity principals. Such prioritization can reduce the chance of infection to members of society. |

| Chen et al. (2020) | To find the optimal allocation of COVID-19 vaccines to multiple priority groups with limited resources | Use of SAPHIRE simulation model | Five priority groups | Number of susceptible and exposed individuals in each group, population size, transmission rate | Two allocation policies, namely static and dynamic were developed to minimize the number of infections or deaths. Static policies could achieve less infected cases (when younger groups are given priority) and deaths (when older groups are given priority). In dynamic policies, the priority should be given to older groups and then to younger ones. |

| Davila-Payan et al. (2014) | To investigate the factors which affect the pandemic vaccination coverage | Regression analysis | High-risk adults and children | State campaign information and state characteristics, preparedness funding, demographics, preventive behavior, surveillance data, and providers | Positive association between school clinics programs and two factors of a. children vaccine coverage and b. increased proportion of administered doses. Positive association between the coverage for high-risk adults and the shipments of vaccine to “general access” locations. |

| Goldstein et al. (2012) | To prioritize allocation of vaccine during a declining epidemic | Optimization model | Age and degree of vulnerability | Mortality risk, vaccine efficacy, medical conditions, | The analysis shows that in case of a pandemic and to minimize the total number of mortalities the school-age children should be given the highest priority. |

| Huang et al. (2017) | To allocate different types of vaccine while maximizing geographic equity across 189 Texas counties in the USA | Optimization model | Five priority groups (age, pregnant women, infant caregivers and adults at high risk) | Information about priority groups and geographical regions | The findings indicate that a proportionally fair allocation of discretionary cache would maximize the coverage of priority population in the countries hence, maximizing geographic equity. |

| Mamani et al. (2013) | Inefficiency in the vaccine allocation due to interdependencies between geographical regions | Mathematical model | none | Quantity of order and distribution in one country, the number of secondary infections in each country | The authors suggest contractual mechanism to reduce the inefficiencies in vaccine allocations |

| Teytelman and Larson (2013) | To allocate limited vaccine to the US states to contain an influenza outbreak | Heuristics | none | Consider pandemic status in geographical regions based on real-time data in order to allocate vaccine | Considering the latest status of regional pandemic waves can significantly reduce the number of infections in the whole country |

| Uribe-Sánchez et al. (2011) | To help strategies cope with influenza pandemic in four regions in Florida, USA | Simulation-based optimization model | none | Morbidity, social distancing, and mortality | The proposed model is able to re-allocate resources remaining from the previous allocations which means better resource utilization. |

| Yarmand et al. (2014) | To contain the epidemic in multiple locations | Two-stage stochastic linear program (2-SLP) | Geographical regions | Population of region, attack rate, doses of vaccine | The reduction of vaccines doses and the attack rate. Also, since stage II is based on the outcome of stage I vaccination it is possible to more efficiently redistribute vaccine doses after stage I. |

| Govindan et al. (2020) | To develop a decision support system to classify community members and mitigate the epidemic outbreaks | Fuzzy inference system (FIS) | Four groups based on age, pre-existing diseases, risk level of their immune system | Age, pre-existing diseases, fever, tiredness, and dry cough | The validation stage using data shows the effectiveness of the proposed decision support systems. |

| Li et al. (2018) | To compare vaccine allocation strategies based two sets of information | Agent-based simulation | none | Individuals with certain states such as being susceptible, exposed, hospitalized, etc. Three levels of populations: community, peer groups and household. | The attack rate wanes when both population and vaccine inventory information are used. This leads to a reduction in the amount of inventory left over. |

| Biggerstaff et al. (2015) | To assess the impact of different vaccine plan in influenza pandemic | Simulation-based scenarios | Priority is given to the individuals who received the first dose | Vaccination coverage, clinical attack rates, case hospitalization ratios, case fatality ratios, , various starts of vaccination programs, vaccine effectiveness, and dose administration rate | Among various variables, the start date of vaccination has the highest impact. The administration rate and the effectiveness of vaccine did not have impact same as the start time of vaccination. Also, the case hospitalization, case fatality ratios, and clinical attack rate had the highest influence |

| Foy et al. (2021) | To compare vaccine allocation strategies based on age priority groups and non-pharmaceutical interventions | Mathematical Simulation | Eight priority groups 0–10, 10–20, [ . . . ] 60–70, 70 years | Vaccine efficacy, target coverage, rollout speed, immunity types | Prioritizing older individual would lead to the highest reduction in deaths regardless of the variables in the model such as vaccine efficacy, target coverage etc. |

| Rao and Brandeau (2021) | To control infectious disease, and minimize deaths, new infections, life years lost or QALYs | SIR (Susceptible, Infectious, or Recovered) model | Two priority groups with high morbidity | Infection duration, infection severity, infected fatality ratio, death rate, expected life years lost | Prioritizing young individuals to minimize new infections and old individual to minimize death, life years lost or QALYs |

| Roy et al. (2021) | To disseminate vaccines among zones | linear optimization model | Geographical zones | Infection ratio, population density, susceptible count and infection ratio as well as transportation costs | The proposed model allocates vaccines efficiently and in the meantime prevents geographical zones experiencing resource starvation. |

Table 2.

Literature review on the distribution stage of vaccine supply chain.

| Authors | Objectives | Research method |

Variables | Stationary or Mobile DC |

Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halper and Raghavan (2011) | To maximize the service provided by mobile facilities | Routing problem | Demand service by each route, cumulative rate of demand | Mobile | The proposed heuristics show optimal routes for mobile facilities especially when demand changes over time. |

| Ramirez-Nafarrate et al. (2015) | To minimize the waiting time and travel distance to optimize the vaccine distribution | Genetic algorithm | Arrival rate to the point-of-dispensing sites (PODs), number of servers and census track assigned to POD | Stationary | While the proposed model generates output comparable to other similar approaches it is also able to explore a range of alternatives in case the resources are not sufficient to meet the performance objectives. |

| Araz et al. (2012) | Geographic prioritization of distributing pandemic influenza vaccines | Mathematical model | Mortality rate, social contact, infectious and incubation periods, transmission probability and location | unknown | In case vaccines are unavailable at late stage of pandemic it is recommended to prioritize those areas that are expected to have the latest waves of transmission. |

| Lee et al. (2013) | To identify the vaccine optimal location for vaccine distribution centers using RealOpt tool | SEPAIR six-stage model | Use of six stage of SEPAIR model: susceptible; exposed; infectious; asymptomatic; symptomatic; recovered | Stationary | Challenges and the benefits of RealOpt tools are discussed. |

| Aaby et al. (2006) | To optimize the allocation of vaccine distribution centers | Simulation models, capacity-planning and queuing models | Arrival rate, time spent for vaccination, MC capacity, served residents, staff number | Stationary | The proposed models were validated using real data. |

| Rachaniotis et al. (2012) | To minimize the total; number of infections | Scheduling problem | Number of susceptible and infected individuals, processing time, size of subpopulation | Mobile | The optimal schedule using mobile facility could significantly outperforms random scheduling. |

| Emu et al. (2021) | To select optimal distribution centers considering two factors of priority and distance | Optimization model (PD-VDM) | Total population to be vaccinated, number of DCs, DC capacities, priority levels | Stationary | The efficiency of the proposed model was shown using real data. |

| Enayati and Özaltın (2020) | To optimally distribute the vaccine in heterogeneous population | Non-linear optimization problem | Contact rate, group size, infectiousness of infected individuals, infectiousness of exposed individuals, recovery rate, vaccine coverage | Stationary | The group-specific transmission dynamics such as geographic location and age play an important role in the optimal allocation of influenza vaccine. |

| Larson and Teytelman (2012) | To analyze the effect of timing on the vaccine distribution | Mathematical model | Susceptibility, infectivity, and activity levels | Stationary | Vaccines must be administered well before the pandemic reaches its peak. In allocating vaccine, factors such as stage of pandemic in geographical regions should be taken into account. |

| Dessouky et al. (2013) | To optimize the facility location and vehicle routing decisions in large-scale disaster relief | Mathematical modeling | Population size, distance, number of facilities and vehicle, vehicle capacity | Stationary | It is shown how the proposed model is considered in an anthrax emergency. |

| Matrajt et al. (2013) | To optimize vaccine distribution in a group of cities | Mathematical model | Illness attack rate, recovery rate, fraction of symptomatic, contact rates, vaccine efficacies, probability of transmission | unknown | The results indicate that the optimal allocation strategy changes depend on the status of the pandemic. They argue that children as a high transmission group should be given the highest priority during the early stages of the pandemic. This would help to break the transmission cycle early on. However, the priority group will shift to the high transmission group once too many people have already been infected. |

| Brown et al. (2014) | To explore redesigning the vaccine supply chain in Benin through adding freezer and refrigerators to the chain | HERMES simulation model | Labour, storage, transportation, and building costs | Stationary | Both capital and operating costs were reduced by eliminating redundancies in locations’ personnel, equipment, and routes. |

| Ceselli et al. (2014) | To optimize the distribution of vaccine | Mathematical problem: Generalized Location and Distribution Problem | Types and number of vehicles, distance between nodes, capacity and number of distribution center | Mixed | The proposed approach outperforms the existing methods with higher levels of flexibility |

| Gamchi et al. (2021) | To minimize the social cost and the cost of vehicles used in controlling the spread of infectious decease | vehicle routing problem | Number of susceptible, infected and recovered individuals, transmission fate, distance, vehicle capacity, vaccine doses | Stationary | Test problems served to assess the performance of the proposed model. |

| Goodarzian et al. (2021) | To design a sustainable-resilience health care network during the COVID-19 pandemic | Mathematical problem: MILP | Quantity of transported medicines, inventory level | Unknown | The impact of transportation cost on social responsibility of staff and total cost of the model. |

2.1. Vaccine allocation

An optimal allocation strategy for a scarce vaccine is an effective way to contain a pandemic (Longini et al., 2004). The main questions in the allocation stage are who should be vaccinated and how the allocation should be done. These are difficult questions to answer due to the inadequate and uncertain supply of vaccines especially in the case of an unexpected outbreak and the existence of various competing priority groups. Since the supply of the vaccine is limited, it is critical for governments to prioritize and allocate a vaccine based on the vulnerability of certain populations groups (Tavana et al., 2021). Brandeau et al. (2003) posit that a range of factors such as the infection prevalence and incidence, population size, and characteristics of prevention programs imposed by governments affect the optimal resource allocation in a pandemic. The allocation stage is quite unique in the vaccine supply chain. Unlike a typical supply chain, in an allocation stage of vaccine supply chain, end consumers do not pay for the product in most cases so they wield little or no power in allocation-related decisions (Duijzer et al., 2018).

Allocation decisions are usually made at higher levels and while such decisions at global levels are based on contracts between vaccine providers and governments or agreement between countries, allocation decisions within the countries’ borders are based on stage and severity of an epidemic (Emu et al., 2021). What makes the allocation stage in the pandemic vaccine supply chain more complicated is the conflicting goals of the ethical issues such as equity and the effectiveness of vaccine allocations (Enayati and Özaltın, 2020). This seems to be inevitable considering two widely accepted policies to allocate vaccine in a pandemic supply chain: pro-rata and prioritizing policies. In practice, the pro-rata policy is politically favorable because it is simple and minimizes any controversy (Araz et al., 2012). For example, the current allocation policy used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the US vaccine-dispensing body, during a flu epidemic is to use a pro-rata policy in which the vaccines are allocated based on the size of a region’s population. In effect, vaccines might be allocated to regions with no demand while regions in need do not receive a vaccine (Larson and Teytelman, 2012). Despite the importance of equity in the pandemic vaccine supply chain (Delamonica et al., 2005, Jean-Jacques and Bauchner, 2021), only very few studies which consider equity in a form of mathematical modeling. This might be due to the challenges in dealing with equity such as the lack of a consensus on how equity is defined (Mitchell et al., 2009), and how to measure it (Stone, 2002). In the second policy, state-level and/or local government prioritizes the vaccine allocation among population subgroups. Despite the benefits of the pro-rata policy, research shows that prioritizing subgroups can reduce the spread of the pandemic more effectively (Araz et al., 2012, Matrajt et al., 2013). Nowadays, prioritization becomes more important in particular at the early stages of a pandemic outbreak as vaccine supply is quite limited during this period. For a vaccine prioritization system, various criteria are used to define subgroups such as age, degree of susceptibility, occupation, and geographical location. For example, Lee et al. (2012) developed a mathematical model to evaluate age-specific vaccination strategies for the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in Mexico. The key parameters in their model were mortality and contact rates, age distribution of the population, age-specific vaccine efficacy, and hospitalization rates. According to their findings, the optimal strategy is to allocate vaccines to young adults (20–39 yrs.) followed by school-age children. In a similar study, Medlock and Galvani (2009) found that optimal vaccine allocation is based on five outcome measures of deaths, economic costs, years of life lost, infections, and contingent valuation. According to their results, the best strategy for vaccine allocation is to prioritize schoolchildren and adults (30 to 39 yrs.). Tanner et al. (2008) used household parameters such as size and age to define subgroups. They found that these parameters played an important role in developing optimal vaccination allocation strategies.

Goldstein et al. (2012) use mixed factors of age and the degree of vulnerability to define priority groups. They investigate the optimal vaccine allocation in two groups. The first group includes adults with high risk of mortality while the second group includes school-age children due to their role in transmitting virus to their parent and consequently to the wider community. Their analysis shows that in case of a pandemic and in order to minimize the total number of mortalities, school-age children should be given the highest priority. In another study, Matrajt et al. (2010) use a mathematical model to allocate vaccine to two groups: one group with high transmission levels and the other group with high risk in two geographical regions of developed and developing countries. The results indicate that the optimal allocation strategy changes depending upon the status of a pandemic. They argue that children constituting a high transmission group should be given the highest priority at the early stage of a pandemic. This would help to break the likelihood of transmission at the initial stages of a pandemic. However, the priority group will shift to the high transmission group once too many people have already been affected. Buccieri and Gaetz (2013) combined the utility and equity principles in allocating vaccines. Utility principle states that resources should be utilized in order to provide the maximum health benefits to society; hence, emergency and health care workers should be given high priority because of their crucial role in ensuring that society functions as smoothly as possible. Based on age and pre-existing disease, Govindan et al. (2020) consider four priority groups with different risk levels of immune systems. A decision support system was proposed to manage the vaccine demand and reduce the number of infected people. Persad et al. (2020) argue that three groups of individuals should be given priority in vaccine allocations: people in high-risk occupations; health care workers; and people with high-risk conditions. They argue that the vaccine allocation needs to recognize ethical principles such as preventing harm and inoculating disadvantaged people. Deo et al. (2020) consider equity and fairness in allocating the COVID-19 vaccine. They propose a multi-parameters framework for vaccine distribution to prioritize vaccine allocation based on age, co-morbidities, profession, and income. McMorrow et al. (2019) use a range of risk factors to allocate influenza vaccine in low- and middle-income countries. The risk factors include morbidity and mortality rates, and prevalence of risk conditions for each country. According to their results, the highest rate of averted hospitalization per 100,000 belong to inoculated and the highest rate of averted deaths concerned adults with HIV, pregnant women, and individual with tuberculosis. The highest rate of averted death belonged to individuals who were 65 years of age or older.

Mamani et al. (2013) highlight the inefficiencies in the vaccine allocation and these are due to the interdependent risk of infection across borders. They argue that the vaccine decisions such as the quantity of order and distribution in one country influence the size of the outbreak in other countries. To reduce such inefficiencies, they suggest contractual mechanisms and their results confirm that the contract prevents millions of influenza cases. They also show that a lack of coordination would lead to excess vaccines in some regions but shortages in others. Using measures of mortality, morbidity, and social distancing, Uribe-Sánchez et al. (2011) develop a simulation-based optimization model to generate mitigation strategies for the influenza pandemic in four regions in Florida, USA. The proposed model is able to re-allocate resources remaining from the previous allocations which results in greater resource utilization. Teytelman and Larson (2013) developed several heuristics for allocating limited vaccine to states in the US to contain an influenza outbreak. Rather than relying on the traditional deployment of a vaccine based on the size of the resident population, they considered pandemic status in each region based on real-time data in order to allocate vaccine. Their findings show that considering the latest status of regional pandemic waves in emergency planning can significantly reduce the number of infections throughout the whole country. Based on a two-stage vaccination policy Yarmand et al. (2014) developed a two-stage stochastic linear program (2-SLP) for an allocation vaccine problem with an ultimate aim of containing the epidemic in multiple locations. The policy resulted in the reduction of vaccines doses and attack rate. Also, since stage II is based on the outcome of stage I vaccination, it is possible to more efficiently redistribute vaccine doses after stage I. Huang et al. (2017) developed a model to optimize the allocation of different types of vaccine to five priority groups (i.e., 0–3 year-old infants, people aged between 4–24, pregnant women, infant caregivers and adults at high risk) while maximizing geographic equity. This is referred to as the provision of the same proportions of each vaccine type across 189 counties in Texas. The findings indicate that a proportionally fair allocation of discretionary cache would maximize two things: the coverage of priority populations in the countries and geographic equity. Davila-Payan et al. (2014) investigate the factors which affect the pandemic vaccination coverage within two groups of high-risk adults and children. Using a multivariate linear regression, they found that the venue of vaccinations and providers have a positive association with the coverage rate in both groups.

With the aim to allocate the COVID-19 vaccine to different priority groups, Chen et al. (2020) used a SAPHIRE model with the epidemic data from New York City. They developed two allocation policies, namely static and dynamic and these minimize the number of infections or number of deaths. According to their findings, the static polices could achieve less infected cases (when younger groups are given priority) and death (when older groups are given priority). They recommend that in dynamic policies during the early days of a pandemic, the priority should be given to older groups and then to younger ones. Table 1 summarizes the literature on various allocation models for the vaccine supply chain.

2.2. Vaccine distribution

The distribution decisions determine how the vaccine should be delivered to the patient (end consumer) and revolve around the design of the supply chain and logistical decisions at the operational level. For example, this refers to the locations and capacities of medical centers, routing and scheduling for mobile facilities, staffing, and temperature-control logistics. However, a study by De Boeck et al. (2020) shows that research on vaccine distribution has been mainly done on strategic decisions. A vaccine supply chain is a multi-layered supply chain with many decision nodes and firms which makes the distribution in the vaccine supply chain more complicated (Duijzer et al., 2018). Reviewing the literature shows that reducing decision levels can curtail the overall costs and increase the availability of vaccines (Brown et al., 2014). For example, Assi et al. (2013) employed HERMES software (Highly Extensible Resource for Modeling Supply Chains) to model Niger’s vaccine supply chain to compare the existing four-tier (central, regional, district, and integrated health center levels) with a modified three-tier structure (removing the regional level). They showed that by removing the regional level vaccine availability increased quite significantly and reduced supply chain logistics costs. In another study, Goodarzian et al. (2021) proposed a COVID-19 MILP model for a sustainable and resilient health care network that could, under conditions of uncertainty, incorporate major components of a supply chain. Their emphasize the impact of transportation costs on social responsibility of staff and total cost of the model. Masoumi et al. (2012) developed a supply chain network model for a perishable product which yielded equilibrium product supply chain flows and equilibrium product demands. Saif and Elhedhli (2016) devised a cold supply chain model for vaccine to minimize the total cost of the cold supply chain and global warming impact which included refrigerant gas leakage and CO2 emissions. They discovered that the global warming effect could be significantly reduced with a small increase – and in some cases virtually no increase – in cost. Biggerstaff et al. (2015) put together a model to investigate the impact of various scenarios on the number of hospitalizations and deaths in an influenza pandemic. These scenarios include vaccination coverage, different vaccination programs, number of vaccine doses administered per week, and levels of vaccine effectiveness. Their results show that the start of vaccination program (before a pandemic) has the highest impact on both the number hospitalization and deaths. In a similar study, Enayati and Özaltın (2020) proposed a non-linear optimization problem and how an influenza vaccine should be distributed. They showed that the group-specific transmission dynamics such as geographic location and age play an important role in the optimal distribution of influenza vaccine units.

Using a mixed-method of interviews and survey method, Privett and Gonsalvez (2014) show that the lack of coordination among different actors, layers, and functions of pandemic vaccine supply chain is the first challenge that senior managers of health pharmaceutical supply chain face. To a great extent, the issue is due to conflicting priorities of different actors (Yadav, 2010) and too many global health systems that are not well structured and informal alliances governed in health supply chain (Fidler, 2007, Sridhar and Batniji, 2008). Effective and real time communication between vaccine providers and health authorities plays an important role in improving coordination. Fitzgerald et al. (2016) emphasized good coordination between public health programs and pharmacies for successful vaccine distribution plans in 53 US jurisdictions. Though a significant proportion of all 53 jurisdictions (88.7%) included pharmacies in the pandemic vaccination programs, the authors argue that formalized agreement need to be established between public health departments and pharmacies to: firstly, enhance vaccine distribution plans; and secondly, maximize the utilization of pharmacies during a pandemic.

Arifoğlu and Tang (2021) proposed an incentive program to coordinate a pandemic vaccine supply chain for both sides of demand and supply. On the demand side, there exist individuals who behave on a self-interested basis to participate in vaccination programs. On the supply side, there are vaccine manufacturers who aim to maximize their profits with some levels of uncertainty. The authors show how on the demand side incentive programs create a negative incentive to control the demand in case of limited vaccine supply and vice versa. On the supply side, the incentive programs subsidize the manufacturers to supply vaccine in large amounts but penalizes them for failing to do so. Lydon et al. (2015) assess the coordination efforts in the vaccine supply chain at a higher level and propose outsourcing some logistics operations to the private sector. Their analysis shows the theoretical benefits of outsourcing. Using the mixed integer programming (MIP), Yang et al. (2021) suggested a new algorithm to formulate the distribution network design for childhood vaccines in four African countries. The proposed MIP-based disaggregation-and-merging algorithm is able to yield optimal solutions when the network is small and the minimum cost is verifiable. For large problems that cannot be solved by MIP commercial software, the algorithm yields a reasonable solution requiring only very short computation time. Matrajt et al. (2013) used a airline transportation network to optimally distribute limited doses of a vaccine within a network of 16 South Asian cities. They combined a mathematical model with a genetic algorithm to minimize the infection attack rate. Under their proposed vaccination strategy, the attack rate dropped significantly. Also, they found those strategies which involved cooperation among cities in distributing vaccines resulted in lower attack rate (17% lower) compared to the strategies solely based on equal distribution of vaccines in the cities.

Using two factors of priority and distance, Emu et al. (2021) propose a clustering-based solution to optimally distribute the available COVID-19 vaccines. They compare their proposed model with three different models which included either one or no optimization constraints. The model provides an optimal solution that has the flexibility to consider different demographic variables.

While vaccines are traditionally administered in medical centers, using mobile units for vaccination has been considered for two main reasons. The first is the geographical dispersion of the population to be vaccinated. Using mobile vaccination units play a vital role in geographically dispersed populations and especially in rural and remote areas (Muckstadt et al., 2021, Yang and Rajgopal, 2021). The second reason is the resource and capacity limitation (i.e., number of medical centers, vaccine supply) in vaccine allocation and distribution. We argue that using mobile units can enhance the capacity of vaccine administration. In fact, reviewing the literature shows that using mobile units for vaccination is favored mainly because it provides access to remote/rural areas and convenience for many people (Turcotte et al., 2021). For example, examining the factors relating to vaccine, Liao et al. (2020) found that using mobile units is a convenient alternative which can significantly increase the vaccination probability and promote vaccination uptake. Referring to extra supply, a medical center is able to serve a limited number of neighboring medical centers in proximity using mobile facilities. Halper and Raghavan (2011) employed a routing problem to meet the demand in nodes of a network using mobile facilities. Abbasi et al. (2020) reported the significant impact of medical centers’ capacity on the transmission of a virus in a community, and hence they proposed employing a mobile unit to provide more support for those medical centers where high demand was evident. Table 2 summarizes the extant literature on the distribution stage of the vaccine supply chain.

3. Operationalization and contributions

By August 2021, there were 110 vaccines in clinical development according to WHO (2021b). While countries around the world have already started inoculating their population, new cases of COVID-19 are rising globally as new variants circulate widely. Hence, there is an urgent need to optimally allocate and distribute the produced vaccines to curb the disease’s spread. To address this need, we propose the vaccine allocation system shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Vaccine allocation operational process.

The system commences by estimating the number of people willing to be vaccinated in the catchment area of each medical center. Individuals are required to complete a form on an online booking system (OBS) providing demographic information on their age, gender, occupation, and pre-existing health conditions. In the next step, a susceptibility rate is computed for each priority group based on the data collected through OBS. We define susceptibility rate as a state of physical well-being that is in danger of deteriorating due to an infectious disease. The susceptibility rate serves to categorize all eligible individuals into priority groups. In computing the susceptibility rate various parameters may be used including age, occupation, and pre-existing health condition (Chen et al., 2020, Goldstein et al., 2012, Huang et al., 2017, Govindan et al., 2020). This stage would lead to clustering the population into a number of priority groups ranging from the least susceptible group to extremely susceptible group. Categorization of priority groups forms the first input into the allocation decision stage. Meanwhile, the literature shows that geographical locations with higher population density are at higher risk of exposure to infectious diseases, hence, people who are living in these regions should be given greater priority to be vaccinated in order to contain the pandemic. As the second input to the allocation decision stage in the proposed allocation system, exposure risk is defined as the probability of community transmission. This is calculated as the ratio of demand in a catchment area to the total demand for the same priory group in all catchment areas. The characteristics of the supply chain also play important roles in any vaccine allocation modeling which form the third data input to the allocation decision stage. The procured vaccines are shipped and stored in distribution centers (source nodes) in capital cities. The available vaccine pack distributed to source nodes along with the size of the vaccine pack are important factors that can shape the optimal allocation decision. Research shows that the size of the vaccine packages wields a significant impact on the duration of vaccine administration and the number of transshipped vaccines (Abbasi et al., 2020). Then using specialized vehicles, cold storage boxes containing vaccines are sent to medical centers (sink nodes) to vaccinate individuals. Medical centers might be over- or under-supplied. For this reason, vaccine transshipment between medical centers is included in the proposed model to effectively meet the needs of all medical centers.

Using three data inputs discussed above and applying a mathematical model, the allocation decisions stage aims to simultaneously optimize three sets of mechanisms: (i) direct allocation of vaccines from DC; (ii) indirect allocation through transshipment among MCs; and (iii) mechanisms to return unused vaccines to the DC to ultimately minimize the total weighted risk of unvaccinated populations.

This study makes the following contributions within the domain of the pandemic supply chain.

Proposing a multi-period capacity allocation model: It is obvious that allocation decisions for an ideal vaccine allocation model should be made throughout the entire planning horizon. However, the current computational power is unable to cope with the complexity of a vaccine allocation model even for a short planning horizon (e.g., 60 days) of a mid-size city. At the other extreme, a single-period model is the most simplified approach to address the actual problem which results in an unsatisfactory solution because demand and resource capacities are ignored in future periods. As a theoretical contribution, this study proposes a multi-period vaccine allocation model as well as a novel solution approach which is flexible enough to be used with any computational power. This would help the model to further reduce the residual risk of unvaccinated people compared to the single-period approach. Furthermore, the actual administrating horizon is expected to be significantly decreased.

Replenishment policy: In a similar study, Abbasi et al. (2020) used a base-stock level policy in which a fixed level of vaccine supply became available in each period. The proposed model in this paper employs a (T,Q) inventory replenishment policy for DC. Such a policy is more realistic and suitable for Australia because its federal government considers a daily or weekly quantity of vaccine for all five states and territories regardless of the number of returned vaccines in the previous period. Moreover, the returned vaccine units are disregarded in the single-period model whereas they are added to the capacity of the next period in the proposed multi-period allocation model.

Embedding capacity sharing and cooperation mechanisms: It is quite likely that capacity of medical centers would be the most restrictive constraint in the administering process. Such situations become more prevalent at the later stages of vaccine administration in which the chance of having MCs with no or high demand would increase. This would lead to inefficiencies in the vaccine allocation model. To deal with such problems, as a practical contribution, a cooperation and capacity sharing mechanism is included in the proposed model. Through such mechanisms under-utilized MCs would be able to offer their capacities to the MCs with high demand. The mechanism provides the opportunity for demand to be redistributed among eligible adjacent medical centers, which ultimately improves the overall efficiency of the allocation model.

Embedding mobile units: Health authorities aim to employ all possible means and strategies to enhance the efficiency of vaccination operations. The role of mobile vaccination units becomes more prominent given the geographical distribution of the population (Muckstadt et al., 2021, Halper and Raghavan, 2011). However, as shown in Table 2, the majority of research on vaccine distribution uses stationary vaccine distribution units. As a practical contribution, mobile units are included in the proposed model here to diminish the bottlenecks caused by the capacity constraints.

4. Mathematical model and solution approach

In this section, to address the aforementioned requirements of a vaccine distribution network in a pandemic, we propose a vaccine allocation model in which the decisions are made over multiple periods. We also improve the efficiency of the proposed model by using the capacity sharing mechanism and employing the mobile units. Table 3 presents the notations which are used in the multi-period allocation model.

Table 3.

Notations and definitions.

| Notation | Definition |

|---|---|

| Sets and indices | |

| The set of priority groups, . | |

| The set of demand points (medical centers), . | |

| Parameters | |

| The number of vaccine units in each package (lot size). | |

| The number of unvaccinated people in priority group who are booked to receive the vaccine in medical center in period . | |

| The weight of a priority group . Priority groups with higher weight receive priority for getting the vaccine () . | |

| The capacity of a medical center to administer the vaccine per period of time. | |

| A big number. | |

| A very small number (e.g., 0.00001). | |

| The minimum difference between the weights of each pair of priority groups: . | |

| The travel time between medical centers and . . | |

| The total available travel time for vehicles to transship vaccines between medical centers per day assuming that each vehicle works 8 h per day. For example if there are 5 vehicles available in the transshipment network, . | |

| This binary variable becomes 1 for at most number of medical centers with non-zero demand which are at the closest distance from medical center and they are linked for transshipment of vaccines. is the index of those medical centers. | |

| Decision variables | |

| The number of vaccine packages allocated to demand points (i.e., medical centers) in period . | |

| The number of unvaccinated people in priority group in medical center in period . | |

| The number of vaccine packages which are available in each time period () in the DC given that DC receives the Q vaccine packs from the federal government in each period . | |

| The number of vaccine units administered to unvaccinated people at medical center who are in priority group at period . | |

| The number of vaccine units transshipped from medical center to medical center in period . | |

| The binary decision variables to define if a transshipment from medical center to medical has taken place in period . | |

| The number of unused vaccine units in medical center which are returned to the DC due to no capacity or demand in period . | |

| The binary decision variables to determine transshipment (in or out) in medical center in period . | |

In any pandemic, one of the important aims for health authorities is to vaccinate the whole populace within a target horizon. For the majority of countries dealing with a sudden pandemic outbreak, although the vaccine allocation policies may not be the same, having excellent operational efficiency and service levels (e.g., coverage) supersedes any attempts to minimizing cost inefficiencies regarding the vaccine distribution network. Therefore, the key objective of the proposed allocation model is to effectively distribute the vaccines, whereby the most vulnerable population categories with a higher susceptibility rate receive more attention. In addition to considering the higher priority for the high-risk groups, it is crucial to factor in the exposure risk as one of the underlying reasons that influences the degree of community transmission. In other words, for the same risk group, a larger population in an area leads to higher risk of exposure, so the system should give higher priority for allocating the vaccine to this category.

The schematic overview of a vaccine distribution network is presented in Fig. 2. In the single-period model designed by Abbasi et al. (2020), the distribution center (DC) is assumed to employ the base-stock policy whereby in each period the base-stock level of becomes available to be distributed among the vaccine administering sites. However, we assume a (T,Q) inventory replenishment policy for DC as it is more realistic for the vaccine allocation model. For example, the Australian federal government generally considers a daily/weekly fixed quantity of vaccine for each state. Therefore, irrespective of the number of vaccine units which may be returned from medical centers to the DC in the previous period (), DC still receives the same number of vaccine packs from the federal government on a timely basis.

Fig. 2.

Schematic overview of vaccine distribution network.

Depending on the government decision at the state level, hospitals, medical centers, or even general practitioners may be nominated to vaccinate individuals. In this study, we assume that number of medical centers are assigned to administer the vaccines. Note that each medical center has a limited capacity () to provide the administering services. For each medical center , the catchment area determines the assigned demand (). In the Case Study section, we delineate the mechanism that we consider to select the catchment area for each medical center.

Given that vaccines are distributed in packs with the pack size of , each medical center receives vaccine units in period . However, since this value () is not necessarily divisible by the demand of medical center , an effective allocation model should encapsulate a mechanism to re-distribute the remaining of vaccine units in each period to further decrease the total risk of unvaccinated population. As depicted in Fig. 2, the proposed allocation model includes a transshipment mechanism among medical centers to distribute the remaining vaccine units to other centers located in close vicinity and their demand has not been fully met in the same period. In this sense, if the travel time between the medical centers and would be , the number of transshipped vaccine units between these centers is denoted as .

Based on the stated requirements, we are now able to define the problem as how to develop an effective vaccine allocation mechanism whereby: (i) citizens receive the vaccine based on their exposure risk and susceptibility rating; (ii) the model supports distributing the vaccines in packs; (iii) transshipment strategy improves the operational efficiency of the distribution network, while not exceeding the transshipment capacity of the network; (iv) capacity of medical centers for administering the vaccines to residents living in a reasonable range of proximity from the medical centers is not exceeded; and (v) allocation decisions are made for a multi-period time window to deliver the highest operational efficiency. Next, the proposed mathematical model which is an extension of the study of Abbasi et al. (2020) is presented to address the aforementioned requirements.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

Objective Function: The objective function has three main components to manage the following three key operations of the allocation model:

Minimizing the weighted risk of unvaccinated population (:

In each period (), the term signifies the number of unvaccinated people. The core function of the objective function for the vaccine allocation model is to minimize this term by allocating the vaccine packs directly from the DC as much as possible. However, to design an equitable allocation model, the weighted risk of unvaccinated population should also be considered. The designed weighting factor has two key elements: (i) susceptibility (), and exposure risk (). As explained earlier, depending on a number of parameters including age, occupation, etc. a risk group with higher weight should get more priority to receive the vaccine. Therefore, signifies the susceptibility of each risk cluster and it refers to the weight of priority groups. In the Case Study section, a basic method to determine the values of is provided.

Also the term () is the probability of the community transmission. In a densely populated catchment area, it is more likely that people get exposed to infectious diseases. Therefore, the exposure risk of each priority group can be measured by the quotient of the demand of a particular catchment area and the total demand of all catchment areas for the same priority group. Given that the susceptibility factor of a risk priority group exerts a more significant influence in reducing the total risk of unvaccinated people compared to the exposure risk, we have incorporated a primacy coefficient () to ensure that priority groups with higher weight of susceptibility receive greater attention to get vaccinated, and then the weight of exposure risk is taken into consideration. Note that the whole term of is an indication of Residual Risk in the vaccine allocation model.

Transshipment mechanism ():

Although reducing the residual risk of unvaccinated people through the direct shipment of vaccine units from the DC seems to be the most effective method, embedding the transshipment mechanism in the allocation model can assist to further minimize the residual risk. This mechanism is triggered by two events. First, if there is no demand for what remains of a vaccine pack in a particular medical center, the excess vaccine units can be re-distributed to centers in close proximity to further minimize the total residual risk of unvaccinated people. Second, if in a medical center there are unvaccinated people belonging to the higher priority groups, vaccine units can be shipped from other medical centers when no demand exists for these groups. Given that is the travel time between medical centers, the model seeks transshipment opportunities where the least travel time is possible.

As direct shipping of the vaccine packs from the DC to medical centers and also transshipping the vaccines among medical centers are both included in the objective function, there is a need for another primacy coefficient to ensure that the direct shipping of vaccine packs receives higher priority compared to the transshipment mechanism. This coefficient ( where ) is adopted from Abbasi et al. (2020). Any given value for the which satisfies this condition causes the first component of the objective function (direct shipping) to receive higher priority compared to the second component (transshipment).

Return mechanism ():

For a small portion of vaccine units in a given period, it is possible that no viable option would be available to administer the vaccine. For example, assume that there are remaining vaccines in a medical center and there is no other medical center located in close vicinity with unmet demand. Another example would be the situation in which the capacity of medical centers is full and no transshipment capacity is available in the network. For these situations, we need a complementary mechanism to return the unused vaccines to the DC at the end of each period.

For each period , a medical center may return number of vaccine units to the DC. Note that the returning mechanism should be triggered when there is no opportunity to further decrease the residual risk through the direct shipping vaccine packs from the DC or transshipping the vaccines among the medical centers. Therefore, the primacy coefficient of ensures that the vaccines are returned to the DC if none of the developed allocation mechanisms can be used.

Constraints: Constraints (2) guarantee that in each period, the total number of vaccine units that can be administered in a medical center equals the number of vaccines received from the DC, plus the balance of the transshipped vaccines to/from all other medical centers, plus the difference between the number of returning vaccines to DC in periods and . This is one of the benefits of the multi-period design of a vaccine allocation model because the decision on number of returning vaccines are made over multiple period. Thus, it is likely that the model will be able to identify an opportunity to allocate a vaccine unit rather than returning it to the DC. Constraints (3) ensure that the actual demand of each period () for each priority group in a medical center includes the estimated demand of the current period and the accumulated unmet demand of previous periods.

Constraints (4) limit the total available vaccine units in the DC for each period to be the number of vaccine units that the DC receives from the federal government in period plus the accumulated total number of returning vaccine units from all medical centers over the previous periods. Constraints (5) ensure that no more than the available vaccine packs in the DC can be allocated to the medical centers. Constraints (6) limit the number of vaccine units administered in each period in a medical center to the capacity of the same medical center. Constraints (7) prevent the total capacity of transshipment network to be exceeded, taking to account the total available vehicles and the travel time between the medical centers.

Constraints (8), (9), (10) ensure that each medical center acts as either a sender or receiver in the transshipment network. Constraints (11) limit the transshipment mechanism so that it is available for at most number of medical centers with non-zero demand which are at the closest distance from a particular medical center. Constraints (12) guarantee that for each period, no more than a medical center’s demand can be allocated from the DC. Constraints (13) specify that transshipment of vaccines only takes place when the corresponding route is available for transshipment. Constraints (14), (15), (16), (17) define the domain of variables where the set of non-negative integers is denoted as . Constraints (18), (19), (20) specify the initial value of , , and .

4.1. Solution approach

In a single-period setting, allocation decisions in each period are made in isolation from other periods. Although the single-period model provides a basis for a vaccines allocation model during a pandemic, we have identified a number of opportunities for improvement which result in a superior response plan. Details of the identified initiatives are explained in the following sections.

4.1.1. Solving a multi-period model

It would be more realistic to make the allocation decisions for each time period by considering the demand and available capacities of future periods. Therefore, we have developed a multi-period allocation model to address the myopic issues of the single-period model which leads to sub-optimal results. The issue in designing and implementing a multi-period allocation model is related to limitations in computational power. To clarify this issue, let us assume that the time needed to administer vaccines to a population is 60 days which is called Planning Horizon (PH). The current available computational power is unable to solve such a multi-period model for the entire planning horizon of a mid-size state such as Victoria. To address this issue, we have consulted a number of leading consulting companies which are active in providing solutions for large problems in the supply chain area. This led us to the following solution approach for the multi-period vaccine allocation model.

As depicted in Fig. 3, by conducting a pilot test, first, we need to establish the maximum Multi-Period Window (MPW) which can be solved using the available computational power. For example, in our case study, we have noted that MPW is 14 which means that our computational power (Intel Xeon CPU E5-2680 V3 @2.5 GHz and 64 GB RAM) is able to solve the multi-period problem with a maximum MPW of 14 days within a reasonable solution time. To strike a balance between myopic and hyperopic policies, we consider the following procedure. For one half of the MPW (e.g., 7 days), allocation decisions are made on a daily basis. Subsequently, to ensure that the profile of future demand is not ignored, mean of demand for the subsequent periods is considered for the period . This process continues until estimated demands for the second half of MPW are obtained. Using this method enables the model to consider both current and future demand profiles in allocation decisions for the current period. When allocations are made for the entire MPW period, we retain the results for the first and discard those of the second period. Then, the algorithm restarts for the next periods. When the algorithm progresses, if there are not enough number of periods available to the end of PH, the algorithm adjusts the second part of MPW for the remaining periods.

Fig. 3.

Schematic overview of solution approach for solving the multi-period vaccine allocation problem with MPW.

Since PH is not necessarily divisible by the , having a number of remaining days at the end of phase (I) is possible. Note that allocations may not be completed at the end of PH and it may be extended for a number of periods to ensure that the entire population is indeed vaccinated. In this case, to make a decision as to whether a single-period or a multi-period model should be employed, the algorithm considers two crucial factors: (a) the remaining number of periods, and (b) the magnitude of unmet demand. In phase (II), if there is still an opportunity to solve the model in the multi-period mode, the algorithm continues in the multi-period setting. This process continues until phase (III) in which the algorithm shifts to the single-period setting and completes the allocation process until the value of unmet demand becomes zero.

4.1.2. Augmented multi-period model (capacity sharing and cooperation)

For the majority of vaccine allocation models, demand is generally higher than supply for the first stage of administering vaccines where many people book to receive the vaccine as soon as possible. However, this trend is reversed at a turning point during the administering horizon. From the turning point onward, in particular during the last third of the administering process, there are many medical centers with no demand whereas others are overwhelmingly busy with high capacity utilization rates. To improve the efficiency of the proposed multi-period model, we incorporate a capacity sharing and cooperation mechanism whereby medical centers with low utilization rates share their under-utilized capacities to the other medical centers which are struggling to cope with the demand. The details of the capacity sharing algorithm are provided in Algorithm 1.

Based on the capacity sharing algorithm, first we identify all medical centers with demand higher than their capacity. Assume that medical center is one of them. In the local transshipment network (i.e., ) of medical center , the algorithm searches for all medical centers in that network where not more than 50% of their capacity is utilized. The capacity sharing mechanism is one of the main contributions of this study. The proposed percentage is simply an assumption used to determine whether a medical center is deemed to be under-utilized or over-utilized. Depending on if a medical center is considered over-utilized or under-utilized the sharing capacity mechanism might or might not be triggered. It remains at the discretion of the health care authority to determine the percentage based on circumstances they may face. The proposed model is capable of solving the problem using any other percentages. After identifying the under and over-utilized medical centers, the excess demand of the medical center is randomly redistributed to these medical centers. The random selection process is a non-uniform random sampling where the probability of using a particular medical center for the capacity sharing with medical center is computed based on the extent that its capacity is under-utilized.

4.1.3. Mobile units

In managing the emergency operations, as highlighted in the Literature Review section, using mobile units may assist to improve the supply network’s efficiency. During a pandemic, any delay in vaccinating the entire population results in endangering public health as well as postponing the full recovery of the economy. Therefore, all methods which may expedite the vaccine administering process should be taken into consideration. We integrate a mobile unit network into the current multi-period allocation model to decrease the daily unmet demand and residual risk of unvaccinated population. We assume that number of mobile units are available, each with capacity. In each period, based on the demand and capacity of each medical center, the utilization rate is computed. Medical centers are sorted according to their capacity utilization rate and then mobile units are assigned to the number of medical centers with the highest utilization rate. This dynamic capacity adjusting algorithm tries to improve the optimization model by alleviating the bottlenecks which are caused by the capacity constraints.

5. A case study: State of Victoria, Australia

Though scholars have researched various impacts of COVID-19 on the supply chain, most published articles are opinion-based and lack an empirical focus (Chowdhury et al., 2021). In this study, the proposed model for COVID-19 vaccine allocation is applied to the state of Victoria in order to evaluate the effectiveness of the model. Victoria is a state in the south-east of Australia with an estimated population of 7 million by 2022 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020). The majority of Victoria’s population concentrated in the central south part of the state, particularly the metropolitan region of Greater Melbourne. Melbourne has more than three-quarters of the Victorian population and is the second largest city in Australia. This study assumes that the target horizon of vaccinating the population by the Victorian government is approximately two months. The most updated information regarding the number and location of medical centers in the state has been extracted from the Department of Health, Victoria (Department of Health and Human Services, 2020). Fig. 4 shows the spatial distribution of 325 medical centers (i.e., demand points) in Victoria.

Fig. 4.

Spatial distribution of the 325 medical centers in Victoria and their assigned demand.

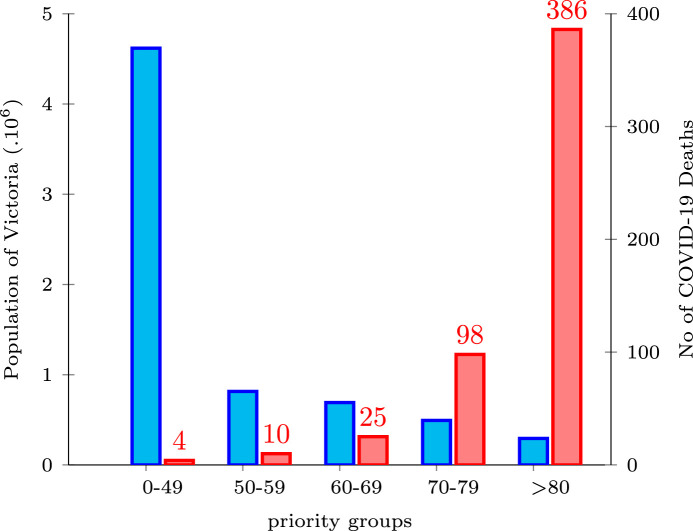

As explained in the Mathematical Model and Solution Approach section, by estimating the susceptibility rate of people during a pandemic, the risk clusters (priority groups) are defined. These clusters facilitate the process of assigning the eligible population into appropriate priority groups. Since forming the priority groups by using any multiple-criteria decision-making is a trivial task, in the current study we consider the age of applicants as a single criterion. Consequently, to estimate the susceptibility rate of Victoria’s population, we use the number of deaths in each priority group and the population of the corresponding priority group. Therefore, the Victorian populace is categorized into five priority groups () using the age as the clustering criterion. Fig. 5 depicts a comparison between the population of the state in 2021 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020) and the number of COVID-19-related deaths based on the priority groups until June 2021 in Victoria (Department of Health Australia, 2021) which indicates the susceptibility rate in each priority group.

Fig. 5.

Victoria’s population and number of COVID-19-related deaths by priority group in 2021.

In the next stage, the following parameters are determined: an estimation of the number of registered applicants to receive the vaccine () in medical center for the priority group ; and also, the geospatial information of medical centers (Department of Health and Human Services, 2020) to estimate the travel time between medical centers (). To estimate these parameters we use the Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016). ASGS comprises the following main levels: Mesh Block () which is designed as building blocks and as the smallest defined geographical area; Statistical Area Level 1 () with the population of between 200 and 800 people; Statistical Area Level 2 () which reflects functional areas as the representative of communities with both social and economic interactions together and with the population of between 3000 and 25,000 people; Statistical Area Level 3 () which focuses on regional areas with similar regional characteristics, labor markets, and administrative boundaries, and with the population of between 30,000 and 130,000 people; Statistical Area Level 4 () with a population above 100,000 persons; and finally, State and Territory (), and Australia (). Each level directly aggregates to its immediate higher level.

Note that the spatial distribution of the population of each priority group is determined based on the geospatial information of Mesh Blocks of Victoria (Barbieri and Jorm, 2019), Lat and Long of s, population of each by priority groups (Victoria State Government Planning, 2019). To assign the population of s to medical centers as an estimation of demand, the following parameters are considered: set of s (), Lat and Long of , Lat and Long of medical centers, and population of each by age group, as the distance between the centroid of each () and each medical center (), and as the total population of each which is aggregated by age groups (). The outputs are ’s and ’s.

This process includes two key sub-processes. In the first sub-process, to estimate , first, Lats and Longs of centroid of s are obtained using the mean of Lats and Longs of MBs. Second, is estimated by measuring the travel time between the centroid of each and each medical center. Third, is computed as the total population of each which is aggregated from all priority groups located in the same area. In the second sub-process, the estimated and are considered to be the inputs of an assignment model so that the values of can be obtained. This determines the population of all s assigned to each medical center. The assignment model identifies the values of by summing the population of all s assigned to medical center for each priority group .

Details of the assignment model are as follows: the total travel time between s and medical centers is minimized in the objective function (Eq. (5.1)); Constraints 5.2 ensure that only one medical center is assigned to each ; Constraints 5.3 state that at least one should be assigned to a medical center; and Constraints 5.4 impede assigning of only one with zero population to a medical center.

The final step is to randomly distribute the demand () for a vaccine over the planning horizon of 60 days. We use Dirichlet distribution to randomly generate 60 weights between 0 and 1 given that the sum of these weights is equal to 1. It is expected that the likelihood of having more bookings at the earlier stages of the planning horizon is higher than the later stages of administering period. Hence, multiplying 60 Dirichlet random values which are sorted in descending order by results the daily number of unvaccinated people in risk cluster who registered to receive the vaccine in medical center .

| (5.1) |

| (5.2) |

| (5.3) |

| (5.4) |

| (5.5) |

To compare results of this study in terms of risk of unvaccinated population with the single-period allocation model (Abbasi et al., 2020), the following identical settings are employed:

Since state of Victoria serves as the case study, identical sets of medical centers () and priority groups () are considered. Similarly, as the total demand for unvaccinated people in priority group who are booked to receive the vaccine in medical center is estimated using the method explained earlier. Moreover, by having the Lat and Long of each medical center extracted from the Geo-location API of the Google Cloud platform (Department of Health and Human Services, 2020), duration of travel time between each pair of medical centers () is estimated for Victoria. With respect to as a big number, considering the values of other parameters, value of is selected.