Abstract

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) suppress adaptive immunity and inflammation. Although they play a role in suppressing anti-tumor responses, development of therapeutics that target Tregs is limited by their low abundance, heterogeneity, and lack of specific cell surface markers. We isolated human PBMC-derived CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ Tregs and demonstrate they suppress stimulated CD4+ PBMCs in a cell contact-dependent manner. Because it is not possible to functionally characterize cells after intracellular Foxp3 staining, we identified a human T cell line, MoT, as a model of human Foxp3+ Tregs. Unlike Jurkat T cells, MoT cells share common surface markers consistent with human PBMC-derived Tregs such as: CD4, CD25, GITR, LAG-3, PD-L1, CCR4. PBMC-derived Tregs and MoT cells, but not Jurkat cells, inhibited proliferation of human CD4+ PBMCs in a ratio-dependent manner. Transwell membrane separation prevented suppression of stimulated CD4+ PBMC proliferation by MoT cells and Tregs, suggesting cell-cell contact is required for suppressive activity. Blocking antibodies against PD-L1, LAG-3, GITR, CCR4, HLA-DR, or CTLA-4 did not reverse the suppressive activity. We show that human PBMC-derived Tregs and MoT cells suppress stimulated CD4+ PBMCs in a cell contact-dependent manner, suggesting that a Foxp3+ Treg population suppresses immune responses by an uncharacterized cell contact-dependent mechanism.

Keywords: Regulatory T cells, CFSE T cell suppression assays, Contact-dependent suppression

Summary Sentence:

Human Foxp3+ Tregs and a Treg-like cell line suppress CD4+ PBMC proliferation by cell-to-cell contact, independent of known checkpoint inhibitors, suggesting an uncharacterized suppressive mechanism.

Introduction

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) play a critical role in maintaining immune tolerance to selfantigens and eliminating autoreactive cells in T cell development (natural/thymic Treg), in peripheral tissue after infection [1,2], during inflammation, and in cancer [3,4]. Tregs were first described as CD4+ cells that inhibited autoreactive T cells and expressed high levels of CD25 [5]. Although they play a role in autoimmunity and cancer immunosurveillance, the development of therapeutics that target human Tregs in vivo is limited by the low abundance, the heterogeneity of Tregs in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), and the lack of specific cell surface markers that readily allow identification or enrichment of live cells so that functional studies can be performed.

Characterization of Tregs that are thymic-derived or peripherally-induced is challenging due to mixed subpopulations upon isolation, lack of a classifiable cell surface marker, and differences in their specificity and secretion of cytokines/chemokines [6,7]. Tregs produce immunosuppressive cytokines including IL-10 [8], TGF-β [3], IL-35 [9] and are found circulating in peripheral blood and in multiple tissue types [10]. Tregs can be isolated from human peripheral blood and expanded in vitro with the addition of IL-2, TGF-β and/or the inhibition of mTOR and PI3K with single antigens, but mixed populations result [11-13]. Tregs are characterized by CD4+CD25high expression; most, but not all, express Foxp3. In addition, cells that express intermediate levels of CD25 can express low or high levels of Foxp3 [7]. Treg subpopulations are known to modulate TH1, TH2 and TH17 responses [10] via cell-to-cell contact mechanisms [14], and through the production of chemokines, cytokines, and metabolites [15]. Peripherally induced CD4+CD25high Foxp3+ Tregs appear to modulate peripheral immune tolerance by expressing high levels of cytokines IL-10, TGF-β, IFN-γ, IL-5, and low levels of IL-2 [16]. Helios, a transcription factor, is expressed in all CD4+CD8−Foxp3+ thymocytes, but is restricted to a subpopulation of peripheral Foxp3+ T cells [17]. Treg populations, like other immune cell populations, are highly heterogenous.

To address a clinical and basic science need to better characterize Tregs and to study the molecular interactions between Tregs and activated T cells, we purified, expanded and characterized CD4+CD25high Foxp3+ Tregs from human donor PBMCs and then identified a human T-lymphoblastoid cell line (MoT) that was previously derived from spleen cells from a patient with a T-cell variant of hairy-cell leukemia that is CD4+CD25high Foxp3+, and has Treg-like activity [18]. Phenotypically, MoT cells and human Tregs share common surface markers such as: CD4, CD25, glucocorticoid induced TNF receptor (GITR), lymphocyte activation gene (LAG-3), programmed death receptor ligand 1 (PD-L1), and C-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 4 (CCR4). We demonstrate that CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ MoT cells suppress CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+ T cell proliferation in a manner similar to CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ PBMC-derived Tregs. Tregs can suppress effector T cells in a cell-cell contact dependent manner [4] and perform cell-contact dependent killing of target cells [19]. Without the presence of APCs, cell-cell contact is required for suppression of CD4+ T cell proliferation by human CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ Tregs. Cell-cell contact is essential for MoT-mediated suppression; transwell membrane separation abrogates the suppressive activity of MoT cells. To further characterize MoT cells, we tested blocking antibodies against known immunomodulatory pathways: PD-L1, LAG-3, GITR, CCR4, HLA-DR, or CTLA-4. None of them inhibited the suppressive activity of MoT cells. Furthermore, neither MoT cells nor PBMC-derived CD4+ CD25high cells could be inhibited by standard antibodies suggesting that one or more uncharacterized cell surface suppressive molecules may exist.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

Tregs were isolated from whole PBMCs using EasySep Human CD4+CD127lowCD25+ Regulatory T Cell Isolation Kit (Catalog # 18063; Stemcell Technologies). Isolated Tregs were expanded up to four weeks. Tregs were stimulated every 7 days with the addition of soluble anti-CD3/CD28 at 1ug/ml and 2.5ug/ml, respectively, with the addition of 500 IU/ml rhuIL-2 every 2-3 days. PBMC-derived Tregs were used for staining and suppression assays 3-5 days after the 2nd or 3rd stimulations. MoT cells were a gift from the late David Golde and are also deposited in ATCC (ATCC CRL-8066; Manassas, VA, USA). They are a human T-lymphoblast cell line derived from spleen cells from a patient with a T-cell variant of hairy-cell leukemia [18]. Jurkat cells (ATCC TIB-152) are a human T-lymphocyte cell line from a patient with acute T cell leukemia. MoT and Jurkat cells were maintained in DMEM (Gibco; Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals; Norcross, GA, USA). Cell lines underwent short tandem repeat validation (Promega; Madison, WI, USA) to confirm their identities.

Flow cytometry

MoT, Jurkat and PBMC-derived Tregs, at 5 × 105 cells per 12×75 mm flow tube were washed twice in PBS, blocked in flow cytometry staining buffer (5% FBS/PBS) for 1 hour at room temperature then incubated individually in staining buffer with each antibody specific to the following markers: Alexa Fluor 700-conjugated CD3 (eBioscience clone UCHT1), FITC-conjugated CD4 (eBioscience clone RPA-T4), PE-conjugated CD25 (eBioscience clone BC96), PE-conjugated GITR (eBioscience clone eBioAITR), Alexa Fluor 700-conjugated LAG-3 (eBioscience clone 3DS223H), PE-conjugated CTLA-4 (BD Biosciences clone BN13), PD-1 (Pembrolizumab), PD-L1 (Atezolizumab), Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated CCR4 (BioLegend clone L291H4), PE-conjugated TCR alpha/beta (eBioscience clone IP26), PE-conjugated TCR gamma/delta (eBioscience clone B1.1), Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated Foxp3 (BioLegend clone 259D), Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated Helios (BioLegend clone 22F6), Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated Granzyme A (BioLegend clone CB9) and FITC-conjugated Granzyme B (BioLegend clone GB11), each for 1 hour at room temperature protected from light. For Foxp3 staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized with the Foxp3 Transcription Factor Buffer Staining Set (eBioscience) then subsequently stained to detect intracellular Foxp3. For Helios staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized with True-Nuclear Transcription Factor Buffer Set (BioLegend) then stained to detect intracellular Helios. For Granzyme A and Granzyme B staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized with BD Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences) to detect intracellular Granzyme A and Granzyme B. Cells were washed three times in 5% FBS/PBS and analyzed on BD FACSCelesta (BD Biosciences). Fluorescence was quantified and expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI).

Co-culture suppression assays

After IRB approval at Arizona State University (protocol #0601000548), peripheral blood was collected from healthy donors. Ficoll-Paque Plus gradient separation of the buffy coat was performed from peripheral blood. CD4+ cells were purified using EasySep Human CD4+ T Cell Isolation Kit (Catalog # 17952; Stemcell Technologies). Cells were allowed to rest overnight in 10% FBS/DMEM at 37°C, 5% CO2. The following day, purified CD4+ T cells were counted, labeled with CFSE dye (Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester, Catalog #10009853; Cayman Chemical) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, washed 3 times in 10% FBS/DMEM, counted and then plated in 10% FBS/DMEM at 2x105 cells per well in a 48-well plate pre-coated with anti-CD3 clone OKT3 antibody at 5.0 ug/mL per well. Co-stimulatory anti-CD28 (eBioscience clone CD28.6) at 2.5 ug/mL final concentration was added at the time of CFSE-labeled cell addition. PBMC-derived Tregs were plated in X-VIVO 15 with 10% huAB serum at 2x105 cells per well (4x105 cells per well in some experiments).

Two-fold serial dilutions of MoT, Jurkat cells or human PBMC-derived Tregs were added to CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+ PBMC, starting at 1.5x105 MoT, Jurkat cells and PBMC-derived Tregs (figures show the ratio of stimulated CD4+ PBMC:Treg cells). Final volume per well was 1 mL. Cells were incubated together for 5 days at 37°C in 5% CO2. To prove that MoT cells did not consume all the nutrients, media was changed daily. On day 5 of culture, cells were collected into individual flow tubes, washed twice in 5% FBS/PBS and placed on ice prior to analysis by flow cytometry (BD FACSCelesta).

Antibody blocking experiments

In experiments to determine if IL-2 consumption by MoT cells or PBMC-derived Tregs was involved in suppression, anti-IL-2R Mab (R&D Systems; clone 22722) was pre-incubated with MoT cells or PBMC-derived Tregs for 30 minutes, washed three times to remove excess antibody, then added to CD4+ PBMCs.

In experiments to determine if anti-human IL-10R (R&D Systems; clone 37607), atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1), mogamulizumab (anti-CCR4), anti-LAG-3, anti-HLA-DR, anti-CTLA-4 or anti-GITR Mabs could attenuate the suppression of MoT cells or PBMC-derived Tregs, thereby restoring CD4+ PBMC proliferation, the Mabs were pre-incubated with MoT cells for 30 minutes, then they were added to CD4+ PBMCs. Note: IL-10R Mab was tested for function by neutralization of IL-1β inhibition by IL-10 (R&D Systems).

Results

Characterization of CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ Tregs from human PBMC in a co-culture suppression assay

Previous studies have identified functionally distinct subsets of human Foxp3+ Tregs cells in healthy donors. We purified CD4+ CD25high CD127lo T cells from 6 different human PBMC donors (age/gender: 25/M, 67/M, 68/F, 55/M, 52/F, 39/F) and expanded them with anti-CD3, anti-CD28, and 500 IU/ml recombinant human IL-2 (rhIL-2). Tregs make up approximately 10% of the CD4+ T cell population[4]. Starting with 1x108 PBMCs, on average, we isolated 1x106 cells or 1% of the starting population. We expanded the isolated Treg population to 2x107 cells by the end of the 3rd stimulation. Representative Foxp3 staining demonstrates that the majority of the pre-expansion cell population is Foxp3+, while some heterogeneity exists post expansion (Supplemental Figure 1).

A hallmark of Tregs is their ability to functionally suppress activated T cell proliferation. To confirm that the CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ T cells possess suppressive activity, we co-cultured these cells for 5 days with CFSE-labeled CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+ cells purified from healthy donor PBMCs. Stimulated CD4+ PBMC proliferation was monitored over the 5 day time-course (Supplemental Figure 2). CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ T cells inhibited proliferation of stimulated PBMCs in a PBMC:Treg ratio-dependent manner (Figure 1). Suppressive activity of CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ Tregs was lost as they were diluted out of the co-culture. Only one proliferative peak of stimulated, CFSE-labeled cells at a 1:2 ratio of stimulated PBMC:Tregs was observed compared to 7 proliferative peaks (cell doublings) in the absence of Tregs. Two-fold dilutions of human Tregs in the co-culture at 1:1 and 1:1/2 stimulated T cells:Tregs resulted in 3 and 4 proliferative peaks of CD3/CD28-stimulated T cells, respectively.

Figure 1.

Five-day CFSE-labeled cell proliferation assays demonstrate that CD4+CD25high Foxp3+ PBMC-derived Tregs and MoT cells suppress CD3/CD28 stimulated CD4+ PBMCs in a cell ratio-dependent manner. (A) PBMC-derived Tregs (top row), MoT (middle row) and Jurkat cells (bottom row) were two-fold serially diluted keeping the same number of CD4+ PBMC. This stimulation induces cell division such that with every cell division, half the cell-associated CFSE dye is divided between the parent and daughter cells. The dividing cells shift left in the flow cytometry histogram. Each peak to the left of the initial peak (far right) represents one cell division. Although we observed variations in the number of cell divisions from independent human PBMC donors (N=6; age/gender: 25/M, 52/F, 55/M, 39/F, 67/M, 68/F), we consistently observed suppression of proliferation by PBMC-derived Tregs and MoT cells that is not seen by Jurkat. Representative data is shown from 6 different donors. (Individual donors are depicted in Supplemental Figure 3).

(B) Average percent proliferation for all biological replicates (N=6) of stimulated, unstimulated CD4+ PBMC, and stimulated CD4+ PBMC co-cultured with PBMC-derived Tregs, MoT or Jurkat cells. Each donor is represented by a shape and the data is paired by donor. Statistical analysis run on the mean percent proliferation. Significance determined by one-way ANOVA; **, p<0.005; ***, p<0.0005; ****, p<0.0001; ns=not significant.

MoT cells suppress PBMC proliferation similar to CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ T cells

The majority of the PBMC-derived Treg populations from 6 different human donors were Foxp3+ (Supplemental Figure 1). Since the primary obstacle in functional characterization of human Tregs is that they need to be permeabilized to detect Foxp3 (or Helios) transcription factors to prove they are Tregs, we searched for, and identified a CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ T cell line and tested it in the suppression assay [20]. MoT cells (CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+) were compared with another CD4+ acute T cell leukemia cell line, Jurkat (CD4+ CD25− Foxp3−) [21], for the ability to suppress PBMC proliferation similar to PBMC-derived CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ T cells. To determine if MoT cells have suppressive activity, we co-cultured MoT or Jurkat cells with CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+ cells purified from healthy donor PBMCs. MoT cells, but not Jurkat cells, inhibited proliferation of stimulated CD4+ PBMCs (Figure 1). Like PBMC-derived Tregs, suppressive activity of MoT cells decreased as they were titrated out of the co-culture in a cell ratio-dependent manner. In contrast, Jurkat cells have no suppressive activity even at the highest ratio of 1:1. Preliminary experiments indicated that MoT cells as a monoclonal cell line are more suppressive than heterogenous PBMC-derived Tregs. Therefore, twice as many PBMC-derived Tregs (1:2) were required to obtain similar suppressive activity as the MoT cell line (1:1), keeping the number of CD4+ PBMC consistent.

MoT cells express known Treg cell surface markers

MoT cells were derived from a patient with a T-cell variant of hairy-cell leukemia [18]. As shown in Figure 2, MoT cells express surface markers consistent with human Tregs such as CD4, CD25, GITR, LAG-3, programmed death receptor ligand 1 (PD-L1), and C-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 4 (CCR4). MoT cells express Foxp3 and weakly express Helios, a transcription factor expressed in thymic-derived Tregs, that differentiates them from peripherally-induced Tregs [17]. They do not express PD-1 or CTLA-4, and despite being CD4+, they do not express CD3 or a T cell receptor (TCR). They also do not express granzymes A and B (Supplemental Figure 4).

Figure 2.

MoT, but not Jurkat cells, demonstrate a CD4+CD25high Foxp3+ Treg-like phenotype. MoT were assessed for cell surface and intracellular markers by flow cytometry and compared to Jurkat and PBMC-derived Tregs: CD4, CD25, Foxp3, Helios, GITR, CTLA-4, PD-1 PD-L1, LAG-3, and CCR4. For each histogram, mean fluorescence intensity of isotype controls is in gray on the left and specific Mab staining is shown on the right (blue histogram). MFI values are indicated on the graph.

Since MoT cells express the IL-2 receptor (CD25), we were concerned that they may act as an IL-2 sink and sequester the IL-2 produced by CD3/CD28 stimulated CD4+ PBMCs, thereby leading to suppression of CD3/CD28 stimulated CD4+ proliferation. Therefore, we pre-incubated an IL-2 receptor blocking antibody (anti-human-IL-2R alpha; R&D Systems MAB223 clone 22722) with PBMC-derived Tregs or MoT cells prior to adding them to the stimulated CD4+ PBMC. PBMC-derived Tregs and MoT cells were washed three times in PBS to ensure removal of excess receptor blocking antibody that would affect CD4+ PBMC proliferation. Figure 3A panel a shows 6 cell divisions in CD3/CD28 stimulated CD4+ cells. When PBMC-derived Tregs or MoT cells were co-cultured with CD3/CD28 stimulated CD4+ PBMCs, PBMC-derived Tregs and MoT cells suppressed cell division to two peaks (panels 3b and 5e). When IL-2 receptor was blocked on PBMC-derived Tregs or MoT cells (panels 3c and 3f), they remained predominately suppressive. Comparing panels, 3a (6 peaks) and 3f (3 peaks) indicate that MoT cells are not sequestering IL-2 from CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+ PBMC. If MoT cells were sequestering IL-2, blocking of the IL-2 receptor would lead to complete restoration of 6 cell divisions in CD3/CD28 stimulated CD4+ cell, as IL-2 would be available for PBMC to proliferate. This experiment suggests that MoT suppression is mainly independent of IL-2. To further convince ourselves that MoT cells were not stealing IL-2 from CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+ PBMC, we performed a separate experiment showing that addition of exogenous, supraphysiological doses of up to 1000 IU/ml of rhIL-2 to the CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+ PBMC:MoT mixture does not reverse MoT suppression (Figure 4). Physiological concentration of IL-2 in human peripheral blood is between 9.4-15.9 pg/ml[22]. Addition of up to 1000 units of rhIL-2 equates to a 10,000-fold excess of IL-2. We performed these experiments with PBMC-derived Tregs and found that neither blocking the endogenous IL-2 receptor (Figure 3) nor adding exogenous supraphysiological levels of rhIL-2 (Figure 4) reversed Treg-mediated suppression of CD4+ PBMC.

Figure 3.

(A) Blocking IL-2 receptor using anti-human-IL-2R alpha (R&D Systems clone 22722) does not restore CD3/CD28-activated CD4+ PBMC proliferation. (a) shows 6 proliferative peaks of CD4+ PBMC activated by anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation. (b) PBMC-derived Tregs co-incubated with anti-CD3/CD28 activated CD4+ PBMC (1:2). (c) shows 3 proliferative peaks when IL-2 receptor-blocked PBMC-derived Tregs are co-incubated with anti-CD3/CD28 activated CD4+ PBMC. (d) Unstimulated CD4+ PBMC. (e) MoT cells co-incubated with anti-CD3/CD28 activated CD4+ PBMC (1:1). (f) shows 3 proliferative peaks when IL-2 receptor-blocked MoT cells are co-incubated with anti-CD3/CD28 activated CD4+ PBMC. Representative data is shown (N=3).

(B) Average percent proliferation for all replicates (N=3) of stimulated, unstimulated CD4+ PBMC, and stimulated CD4+ PBMC co-cultured with PBMC-derived Tregs or MoT cells. Each donor is represented by a shape. Statistical analysis run on the mean percent proliferation, paired by donor. Significance determined by one-way ANOVA; *, p<0.05; **, p<0.005; ns=not significant.

Figure 4.

(A) Supraphysiological levels of exogenous rhIL-2 does not reverse MoT suppression of CD3/CD28-activated CD4+ PBMC proliferation. (a) shows ~7 proliferative peaks of CD4+ PBMC activated by anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation to the left of the farthest right peak. (b) CFSE-labeled CD4+ PBMC with no stimulation. (c) shows suppression of CD3/CD28 activated CD4+ PBMC proliferation when co-incubated with MoT cells (1:1). Panels d-f show suppression of stimulated CD4+ PBMC by MoT cells independent of increasing doses of rhIL-2 (100, 500 and 1000 IU/mL). (g) shows suppression of CD3/CD28 activated CD4+ PBMC proliferation when co-incubated with PBMC-derived Tregs (1:2). Panels h-i show suppression of stimulated CD4+ PBMC by PBMC-derived Tregs independent of increasing doses of rhIL-2. Representative data is shown (N=3).

(B) Average percent proliferation for all replicates (N=3) of stimulated, unstimulated CD4+ PBMC, and stimulated CD4+ PBMC co-cultured with PBMC-derived Tregs or MoT cells. Each donor is represented by a shape. Statistical analysis run on the mean percent proliferation, paired by donor. Significance determined by one-way ANOVA; **, p<0.005; ****, p<0.0001.

Although both MoT and Jurkat have a similar doubling time, we wanted to ensure that MoT cells were not depleting the co-culture of nutrients. An experiment was performed in which media in the co-culture was changed daily for 5 days (data not shown). No significant difference in suppression of CD4+ PBMC proliferation by MoT cells was observed between daily media change and no media change.

Cell to cell contact is required for both PBMC-derived Tregs and MoT Treg suppressive activity

To determine if suppressive cytokines or other soluble paracrine factors might be responsible for the inhibition of proliferation observed in the co-culture assay, we performed an experiment in which MoT cells were separated from CD3/CD28-stimulated T cells by a transwell membrane. Figure 5A shows 6 cell division peaks in CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+ PBMC, but when PBMC-derived Tregs or MoT cells were added, they suppressed the stimulated CD4+ PBMC (panels 5b and 5e). When PBMC-derived Tregs were separated from stimulated CD4+ PBMC by a Millipore 0.4 μm transwell membrane, they were unable to suppress as shown by at least 5 peaks of stimulated CD4+ PBMC in panel 5c. We observed similar cell contact-dependent suppression by MoT cells. In Figure 5 panel f, MoT cells were not suppressive when separated from stimulated CD4+ PBMC, similar to PBMC-derived Tregs. Although suppression is contact-dependent, we were still concerned that a soluble factor might be involved, so we performed a cytokine array to determine what suppressive cytokines were expressed and upregulated by MoT cells and PBMC-derived Tregs when co-cultured with CD4+ PBMCs (Supplemental Figure 5). However, we did not observe an increase in suppressive cytokines when MoT cells or PBMC-derived Tregs were co-cultured with responder cells. We observed expression of IL-10 but not TGF-β. Since IL-10 is highly expressed by both MoT cells and PBMC-derived Tregs, we blocked the IL-10 receptor on CD4+ PBMCs (anti-human-IL-10R alpha; R&D Systems MAB274 clone 37607). When IL-10R was blocked, suppression was not reversed (Figure 6). Our data demonstrates that cell-to-cell contact, not a soluble factor, is required for MoT and PBMC-derived Treg suppressive activity since suppression does not occur when MoT cells or PBMC-derived Tregs are separated from CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+ PBMCs by a transwell membrane or when IL-10 activity is blocked.

Figure 5.

(A) Cell-cell contact is required to functionally suppress proliferation of CD4+ PBMC. (a) Stimulated CD4+ PBMC. (b) Stimulated CD4+ PBMC + PBMC-derived Tregs (1:2). (c) Stimulated CD4+ PBMC + PBMC-derived Tregs separated by Millipore membrane. (d) Unstimulated CD4+ PBMC. (e) Stimulated CD4+ PBMC + MoT cells (1:1). (f) Stimulated CD4+ PBMC + MoT cells separated by Millipore membrane. Representative data is shown (N=3).

(B) Average percent proliferation for all replicates (N=3) of stimulated, unstimulated CD4+ PBMC, and stimulated CD4+ PBMC co-cultured with PBMC-derived Tregs or MoT cells. Each donor is represented by a shape. Statistical analysis run on the mean percent proliferation, paired by donor. Significance determined by one-way ANOVA. **, p<0.005; ****, p<0.0001; ns=not significant.

Figure 6.

(A) Blocking IL-10 receptor using anti-human-IL-10R alpha (R&D Systems clone 37607) does not restore CD3/CD28-activated CD4+ PBMC proliferation. (a) shows 7 proliferative peaks of CD4+ PBMC activated by anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation. (b) PBMC-derived Tregs co-incubated with anti-CD3/CD28 activated CD4+ PBMC (1:2). (c) shows 3 proliferative peaks when IL-10 receptor-blocked anti-CD3/CD28 activated CD4+ PBMC are co-incubated with PBMC-derived Tregs. (d) Unstimulated CD4+ PBMC. (e) MoT cells co-incubated with anti-CD3/CD28 activated CD4+ PBMC (1:1). (f) shows 1 proliferative peak when IL-10 receptor-blocked anti-CD3/CD28 activated CD4+ PBMC are co-incubated with MoT cells. Note: IL-10R Mab was tested for function by neutralization of IL-1β inhibition by IL-10 (R&D Systems). Representative data is shown (N=3).

(B) Average percent proliferation for all replicates (N=3) of stimulated, unstimulated CD4+ PBMC, and stimulated CD4+ PBMC co-cultured with PBMC-derived Tregs or MoT cells. Each donor is represented by a shape. Statistical analysis run on the mean percent proliferation, paired by donor. Significance determined by one-way ANOVA; *, p<0.05; **, p<0.005.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors do not attenuate MoT suppressive activity

To determine if FDA approved and research grade immune checkpoint inhibitors attenuate the MoT Treg suppressive activity, we tested clinical grade anti-PD-L1 (atezolizumab), clinical grade anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), anti-CCR4 (mogamulizumab), anti-GITR agonist, antiLAG-3, and anti-HLA DR monoclonal antibodies (Mabs) for the ability to reverse MoT suppression (Figure 7). Since MoT cells are strong suppressive cells, we used a ratio of 1:1/2 to provide a better opportunity for the blocking antibodies to reverse the suppression. CCR4 was previously reported to be present in Tregs [23]. Although CTLA-4 is not expressed on MoT cells, ipilimumab was tested in case of expression on stimulated CD4+ PBMCs. Since Treg suppression is thought to be mediated via the TCR, MHC II was blocked. None of the Mabs including anti-GITR, anti-CCR4, anti-PD-L1, anti-CTLA-4 or anti-HLA DR reversed MoT cell-mediated suppression of CD4+ PBMC. The same blocking Mabs did not interfere with PBMC-derived Treg-mediated suppression (Supplemental Figure 6). Additionally, a suppression assay was performed with an antibody blocking Fas-FasL interaction, and reversal of suppression was not observed (data not shown). These results suggest, but do not completely prove that the mechanism of MoT cell suppression is not mediated via the PD-1/PD-L1 axis, CCR4, GITR or Fas-FasL mechanisms. Despite expressing CD4, MoT cells do not express CD3 or a TCR (Supplemental Figure 4), further supporting that suppressive activity is independent of TCR-peptide-MHC interactions. Note: antibodies were incubated with CD4+ stimulated cells alone and did not inhibit proliferation (data not shown).

Figure 7.

(A) Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 axis, GITR, CCR4 and TCR-MHC interactions are not involved in suppression of CD4+ PBMC proliferation by MoT cells. (A) Anti-GITR, anti-CCR4 (mogamulizumab), anti-PD-L1 (atezolizumab), anti-HLA-class II, anti-LAG-3 blocking, and ipilimumab was used as an anti-CTLA-4 blocking Mab. CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+ PBMC were co-incubated with MoT cells at a 1:1/2 ratio. Blocking antibodies were used at 10 μg/ml final concentration. Representative data is shown (N=3).

(B) Average percent proliferation for all replicates (N=3) of stimulated, unstimulated CD4+ PBMC, and stimulated CD4+ PBMC co-cultured with MoT cells. Each donor is represented by a shape. Statistical analysis run on the mean percent proliferation, paired by donor. Significance determined by one-way ANOVA *, p<0.05; **, p<0.005; ***, p<0.0005; ****, p<0.0001.

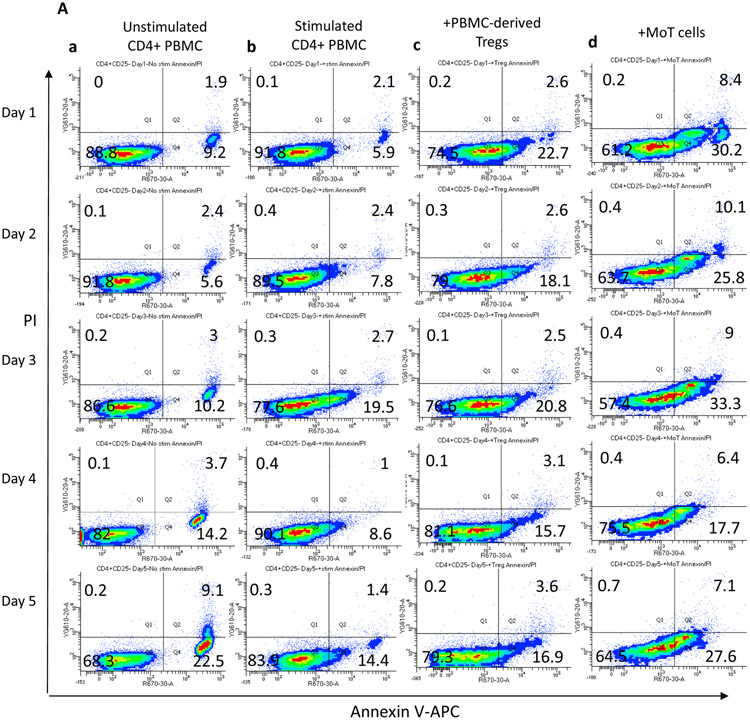

MoT cells induce apoptosis of CD4+ PBMCs

To begin to determine a mechanism of suppression of CD3/CD28-activated CD4+ PBMC proliferation by MoT cells and PBMC-derived Tregs, we performed an annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) experiment and evaluated the results by flow cytometry (Figure 8). This experiment allows for visualization of early and late apoptosis, as well as dead cells. Progression through the apoptotic pathway was assessed over the course of the five-day assay. In Figure 8A, viable CD4+ PBMCs are Annexin V/PI negative (lower left quadrant), Annexin V single positive cells (lower right quadrant) indicate cells undergoing early apoptosis, and Annexin V and PI double positive cells indicate cells in late apoptosis (upper right quadrant). The presence of these 3 distinct phenotypes within the CD4+ PBMC population suggests apoptosis is being induced in activated CD4+ PBMC when stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28.

Figure 8.

(A) MoT cells induce apoptosis (lower right quadrant representing CD4+, Annexin V+ population) early in the co-incubation. CD4+ PBMC were labeled with CFSE prior to stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28. Contour plots show Annexin V/PI staining of CFSE-gated CD4+ PBMC over the five-day assay. (a) Unstimulated CD4+ PBMC. (b) anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+ PBMC. (c) CD4+ PBMC co-incubated with PBMC-derived Tregs (1:2). (d) CD4+ PBMC co-incubated with MoT cells (1:1). Representative data is shown (N=3).

(B) Percent of cells in each quadrant per day for all samples (N=3) of stimulated, unstimulated CD4+ PBMC, and stimulated CD4+ PBMC co-cultured with PBMC-derived Tregs or MoT cells. Statistical analysis run on mean percent calculated for viable (Annexin V− PI−), early apoptotic (Annexin V+ PI−), and late apoptotic (Annexin V+ PI+) cells over the 5 day time-course. Significance determined by two-way ANOVA; *, p<0.05; ****, p<0.0001; ns=not significant.

Although stimulated responder cells undergo apoptosis, co-incubation with MoT cells and PBMC-derived Tregs hastens apoptosis over the course of the five-day assay. Figure 8 suggests that MoT cells not only inhibit CD4+ PBMC proliferation but also induce apoptosis. By 24 hours of co-culture with MoT cells, the mean CD4+ PBMC population (32.6%) is Annexin V (+), and by day 5 almost half of the mean total population is undergoing early (36%) or late apoptosis (11.1%) compared to stimulated cells alone (21.1% and 2.2%, respectively). This result suggests that MoT cells ultimately induce CD4+ PBMC cell death and clearly enter into an Annexin V-positive and PI-negative state (early apoptosis) prior to cell death at an earlier timepoint in the co-incubation compared to stimulated cells alone. A population of stimulated CD4+ PBMC also undergo apoptosis when co-incubated with PBMC-derived Tregs.

Reverse transcriptase inhibitor AZT does not reverse the suppression of MoT cells

ATCC indicates that MoT cells carry three copies of HTLV-II genome, one replication competent and two defective. To address the possibility that MoT cells suppress CD4+ CD3/CD28-simulated T cells by transferring and/or infecting activated CD4+ PBMCs with HTLV-II, the suppression assay was performed in the presence of azidothymidine (AZT). Even if HTLV-II virus entered CD4+ T cells, AZT inhibits reverse transcriptase and prevents viral RNA from being reverse transcribed into DNA and integrating into T cell genomes. Treatment of MoT cells with AZT, however, does not cure them of infection because reverse transcriptase has already integrated the pro-viral DNA into the genome of MoT cells. It is possible, however, that an HTLV-II gene such as Tax could be driving the expression of either an HTLV-II protein or another cellular protein capable of mediating Treg-like activity (Supplemental Figure 7).

Discussion

The study of regulatory T cells is limited by the low prevalence of Tregs in peripheral blood, their heterogeneity upon isolation and characterization, and primarily by the lack of a cell surface molecule that would allow purification of Tregs for functional characterization alone and in the presence of other purified cell populations. Therapies that boost Treg function could inhibit pathologic immune cell function in autoimmune disease [24], decrease graft rejection in solid organ transplants [25], and decrease graft-vs-host disease in allogeneic bone marrow transplants [26]. Conversely, suppression of Tregs may also enhance the anti-tumor response with immune checkpoint therapies and has been shown to increase the anti-tumor activity of CD8+ CTL [27]. However, no FDA approved therapies exist that specifically either enhance or suppress Treg activity, although a phase II clinical trial is recruiting to expand Tregs to treat type 1 diabetes [28].

These challenges hinder development of therapies that specifically target Tregs. We observed that the majority of PBMC-derived Tregs, expanded from human PBMC are CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+. Since it is not possible to sort and functionally characterize T cells that have been permeabilized for Foxp3 staining, we studied a CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ MoT cell line in a co-culture suppression assay which demonstrates MoT cells, like PBMC-derived Tregs, inhibits proliferation of stimulated CD4+ PBMCs. Mechanisms of Treg-mediated suppression include the production of soluble suppressive factors and indirect suppression of CD4+ T cells via targeting APCs, while a subset of CD4+CD25high Tregs suppress CD4+CD25− responder cell activation via cell-cell contact [20]. In our in vitro suppression assays, we assessed MoT and Treg cell-contact dependent suppression. Separation of MoT cells and PBMC-derived Tregs from stimulated CD4+ PBMC by a transwell insert did reverse suppression; this strongly suggests a cell-to-cell contact mechanism of MoT suppression. As CD4+CD25high Foxp3+ PBMC-derived Tregs or MoT cells were titrated out of the co-culture, CD4+ PBMCs regained the ability to proliferate as shown in Figures 2 and 3. Daily media changes ensured MoT cells and PBMC-derived Tregs were not depleting the co-culture of nutrients (data not shown).

Since MoT cells and PBMC-derived Tregs have an IL-2 receptor, we were initially concerned they were “sponging up” any IL-2 produced by activated CD4+ T cells, having the effect of suppressing their proliferation. To address this possibility, we pre-incubated MoT cells and PBMC-derived Tregs with an IL-2 receptor blocking antibody prior to washing away excess blocking Mab and adding the IL-2 receptor-blocked cells to activated CD4+ PBMC. If MoT cells and PBMC-derived Tregs were scavenging IL-2 produced from activated CD4+ T cells, blocking the IL-2 receptor would have restored the proliferative capacity of CD4+ T cells such that the number of cell divisions would look similar to activated CD4+ T cells alone. We did not observe this. MoT cells and PBMC-derived Tregs suppressed activated CD4+ PBMCs even in the presence of an IL-2 receptor blocking antibody. To further demonstrate that MoT and PBMC-derived Treg suppression is not dependent on a lack of IL-2 for CD4+ T cell proliferation, we added exogenous rhIL-2 to the suppression assay (Figure 6). In the absence of MoT cells or PBMC-derived Tregs, CD4+ T cells from the donor used in this experiment divided at least 7 times over 5 days. Addition of 100, 500, and 1000 IU/ml of rhIL-2 did not overcome MoT or PBMC-derived Treg suppression of CD4+ T cell division.

Several limitations should be considered when evaluating our study. First, we did not identify a cell surface protein on MoT cells or PBMC-derived Tregs responsible for the suppressive Treg-like activity. Our data indicates that the suppressive properties of MoT cells and PBMC-derived Tregs do not appear to be due to soluble factors like cytokines. Despite our data showing a cell-to-cell contact dependence for Treg suppression, we evaluated a prominent suppressive cytokine, IL-10, secreted by both MoT cells and PBMC-derived Tregs. We did not observe reversal of suppression when IL-10 receptor was blocked, indicating that IL-10 is not responsible for suppression. Since PBMC-derived Tregs are a polyclonal population, compared to monoclonal, there are likely multiple other soluble suppressive molecules. The suppression we observed does not require known pathways such as PD-L1 or CTLA-4 axes since neither atezolizumab nor ipilimumab reversed suppression mediated by MoT cells or PBMC-derived Tregs on CD4+ T cells. Both atezolizumab and ipilimumab used in our study were from clinical grade stocks of antibodies used for the therapeutic treatment of patients. Since MoT cells are infected with HTLV-II, a suppressive molecule could be due to HTLV-II, but since PBMC-derived Tregs appear to mediate the same type of suppression, the suppressive molecule could also be lineage-specific and/or expressed at a certain stage of lymphocyte development. Alternatively, HTLV-II genes could be driving the expression of either an HTLV-II protein or another cellular protein capable of mediating Treg-like activity.

Second, since MoT cells are allogeneic to all PBMC donors used in this study it is possible that some T cell receptor recognition by stimulated CD4+ PBMC of allo-MHC on MoT cells influenced their suppressive activity. However, we performed allogeneic suppression assays with PBMC-derived Tregs and observed the same suppressive effect as MoT-mediated suppression and autologous Treg suppression (data not shown, available upon request). Therefore, suppressive capacity of MoT cells and PBMC-derived Tregs overcomes any potential allogeneic stimulation.

Third, CD3/CD28 stimulation is variable among human donors. Six different PBMC donors were used in this study. The proliferative capacity after CD3/CD28 activation of each donor is slightly different. Some T cells double 8 times in 5 days while others double 5 or 6 times. Additionally, some donor PBMC are more easily suppressed by MoT cells, while some are less easily suppressed. However, activated CD4+ PBMCs from 6 different PBMC donors were all suppressed by MoT cells (Supplemental Figure 2).

Fourth, we did not detect TCR or CD3 expression on MoT cells. This suggests that the suppression observed is not a trogocytosis-mediated phenomenon [19]. MHC II blockade had no impact on suppression, further supporting that the suppressive activity is independent of TCR-peptide-MHC interactions. One possibility is that MoT are of NK origin that kill allogeneic cells. We think this is unlikely because MoT cells do not express granzymes and suppression is not reversed by blocking Fas-FasL interaction. Although MoT cells are leukemia cells, they could still represent an uncharacterized sub-population of suppressive/regulatory lymphocytes. We are currently interrogating PBMC-derived CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ T cells to determine if there is a population of Foxp3+ cells that lacks TCR/CD3.

Tregs can limit antitumor responses and the presence of Tregs in solid tumors can impact clinical prognosis. Although current cancer therapies such as cyclophosphamide, sunitinib, idelalisib [29], and sorafenib can modulate Treg suppressive activity, these therapies are not Treg specific and likely impact anti-tumor T cells. Thus, there is a growing clinical need to selectively target Tregs in tumors while preserving anti-tumor T cell activity and peripheral immune homeostasis.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti-PD-L1, -CCR4, -LAG-3, -CTLA-4, or -GITR did not attenuate MoT Treg suppressive activity. Herein, we demonstrated that human PBMC-derived CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ Tregs and MoT cells suppress CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+ PBMCs in a cell contact-dependent manner, suggesting that a CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ Treg population in peripheral blood may play a role in suppressing CD4+ T cell-mediated immune responses by an unknown cell contact-dependent mechanism. Although MoT cells and PBMC-derived Tregs induce apoptosis, they may do so by different mechanisms. Both are driving stimulated CD4+ PBMC toward apoptosis but it is unclear if induction of apoptosis is the major mechanism of suppression. Other mechanisms may involve T cell fratricide, autophagy, and other caspase-dependent cell death. Further studies are required to identify the cell surface marker(s) that suppresses CD4+ T cell proliferation. Transcriptional and epigenetic profiling of Treg and MoT should be performed in future studies to investigate the suitability of MoT cells as a model of Tregs. At this point, it is unclear if the mechanisms of suppression by MoT cells and PBMC-derived Tregs are the same. We are actively investigating potential cell surface molecules and pathways. Characterization of a novel suppressive marker on Tregs and related cell types could lead to functional cellular and molecular studies of Tregs with the goal of harnessing them for therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by Gloria A. and Thomas J. Dutson Jr. Kidney Research Endowment, Novartis, and an ASU-Mayo Seed grant to THH and DFL. THH is supported by the Gerstner Family Career Development Award and the National Cancer Institute (R01CA224917). Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the funding agencies. The funding agencies had no role in the study design.

Abbreviations

- AZT

azidothymidine

- CCR4

C-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 4

- CFSE

Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester

- GITR

glucocorticoid induced TNF receptor

- LAG-3

lymphocyte activation gene

- Mabs

monoclonal antibodies

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PD-L1

programmed death receptor ligand 1

- PI

propidium iodide

- rhIL-2

recombinant human IL-2

- Tregs

regulatory T cells

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

THH has received research funding from Novartis and has served on advisory boards for Exelixis, Genentech, EMD-Serono, Ipsen, Cardinal Health, Surface Therapeutics, and Pfizer. GJW is an employee of SOTIO and former employee of Unum Therapeutics-both outside of submitted work, reports personal fees from MiRanostics Consulting, Paradigm, Angiex, IBEX Medical Analytics, Spring Bank Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, IDEA Pharma, GLG Council, Guidepoint Global, Ignyta, Circulogene, Genomic Health-all outside this submitted work; has received travel reimbursement from Cambridge HealthTech Institute, GlaxoSmith Kline, and Tesaro-outside of this submitted work; had ownership interest in MiRanostics Consulting, Unum Therapeutics, Exact Sciences, and Circulogene-outside the submitted work; and has a patent for methods and kits to predict prognostic and therapeutic outcome in small cell lung cancer issued, outside the submitted work. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Bibliography

- [1].Belkaid Y, Blank RB, Suffia I, Natural regulatory T cells and parasites: A common quest for host homeostasis, Immunol. Rev (2006). 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lanteri MC, O’Brien KM, Purtha WE, Cameron MJ, Lund JM, Owen RE, Heitman JW, Custer B, Hirschkorn DF, Tobler LH, Kiely N, Prince HE, Ndhlovu LC, Nixon DF, Kamel HT, Kelvin DJ, Busch MP, Rudensky AY, Diamond MS, Norris PJ, Tregs control the development of symptomatic West Nile virus infection in humans and mice, J. Clin. Invest (2009). 10.1172/JCI39387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Roychoudhuri R, Eil RL, Restifo NP, The interplay of effector and regulatory T cells in cancer, Curr. Opin. Immunol (2015). 10.1016/j.coi.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Nishikawa H, Sakaguchi S, Regulatory T cells in tumor immunity, Int. J. Cancer 127 (2010) 759–767. 10.1002/ijc.25429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Suri-Payer E, Amar AZ, Thornton AM, Shevach EM, CD4+CD25+ T cells inhibit both the induction and effector function of autoreactive T cells and represent a unique lineage of immunoregulatory cells., J. Immunol (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hill JA, Feuerer M, Tash K, Haxhinasto S, Perez J, Melamed R, Mathis D, Benoist C, Foxp3 Transcription-Factor-Dependent and -Independent Regulation of the Regulatory T Cell Transcriptional Signature, Immunity. (2007). 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Shevach EM, From Vanilla to 28 Flavors: Multiple Varieties of T Regulatory Cells, Immunity. (2006). 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Asseman C, Mauze S, Leach MW, Coffman RL, Powrie F, An essential role for interleukin 10 in the function of regulatory T cells that inhibit intestinal inflammation, J. Exp. Med (1999). 10.1084/jem.190.7.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Collison LW, Workman CJ, Kuo TT, Boyd K, Wang Y, Vignali KM, Cross R, Sehy D, Blumberg RS, Vignali DAA, The inhibitory cytokine IL-35 contributes to regulatory T-cell function, Nature. (2007). 10.1038/nature06306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Campbell DJ, Koch MA, Phenotypical and functional specialization of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells, Nat. Rev. Immunol (2011). 10.1038/nri2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Battaglia M, Stabilini A, Roncarolo MG, Rapamycin selectively expands CD4+CD25+FoxP3 + regulatory T cells, Blood. (2005). 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sauer S, Bruno L, Hertweck A, Finlay D, Leleu M, Spivakov M, Knight ZA, Cobb BS, Cantrell D, O’Connor E, Shokat KM, Fisher AG, Merkenschlager M, T cell receptor signaling controls Foxp3 expression via PI3K, Akt, and mTOR, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A (2008). 10.1073/pnas.0800928105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Strainic MG, Shevach EM, An F, Lin F, Medof ME, Absence of signaling into CD4 + cells via C3aR and C5aR enables autoinductive TGF-β1 signaling and induction of Foxp3 + regulatory T cells, Nat. Immunol (2013). 10.1038/ni.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wing K, Onishi Y, Prieto-Martin P, Yamaguchi T, Miyara M, Fehervari Z, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S, CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function, Science (80-.). (2008). 10.1126/science.1160062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fallarino F, Grohmann U, Hwang KW, Orabona C, Vacca C, Bianchi R, Belladonna ML, Fioretti MC, Alegre ML, Puccetti P, Modulation of tryptophan catabolism by regulatory T cells, Nat. Immunol (2003). 10.1038/ni1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zeng H, Zhang R, Jin B, Chen L, Type 1 regulatory T cells: A new mechanism of peripheral immune tolerance, Cell. Mol. Immunol (2015). 10.1038/cmi.2015.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Thornton AM, Korty PE, Tran DQ, Wohlfert EA, Murray PE, Belkaid Y, Shevach EM, Expression of Helios, an Ikaros Transcription Factor Family Member, Differentiates Thymic-Derived from Peripherally Induced Foxp3 + T Regulatory Cells, J. Immunol (2010). 10.4049/jimmunol.0904028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Saxon A, Stevens RH, Quan SG, Golde DW, Immunologic characterization of hairy cell leukemias in continuous culture, J. Immunol 120 (1978) 777–782. http://www.jimmunol.org/content/120/3/777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Akkaya B, Oya Y, Akkaya M, Al Souz J, Holstein AH, Kamenyeva O, Kabat J, Matsumura R, Dorward DW, Glass DD, Shevach EM, Regulatory T cells mediate specific suppression by depleting peptide–MHC class II from dendritic cells, Nat. Immunol (2019). 10.1038/s41590-018-0280-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hamano R, Wu X, Wang Y, Oppenheim JJ, Chen X, Characterization of MT-2 cells as a human regulatory T cell-like cell line, Cell. Mol. Immunol 12 (2015) 780–782. 10.1038/cmi.2014.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schneider U, Schwenk H-U, Bornkamm G, Characterization of EBV-genome negative “null” and “T” cell lines derived from children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and leukemic transformed non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Int. J. Cancer (1977). 10.1002/ijc.2910190505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kleiner G, Marcuzzi A, Zanin V, Monasta L, Zauli G, Cytokine levels in the serum of healthy subjects, Mediators Inflamm 2013 (2013). 10.1155/2013/434010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Plitas G, Wu K, Carlson J, Cimaglia N, Morrow M, Rudensky AY, Wolchok JD, Phase I/II study of mogamulizumab, an anti-CCR4 antibody targeting regulatory T cells in advanced cancer patients., J. Clin. Oncol (2016). 10.1200/jco.2016.34.15_suppl.tps3098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bluestone JA, Buckner JH, Fitch M, Gitelman SE, Gupta S, Hellerstein MK, Herold KC, Lares A, Lee MR, Li K, Liu W, Long SA, Masiello LM, Nguyen V, Putnam AL, Rieck M, Sayre PH, Tang Q, Type 1 diabetes immunotherapy using polyclonal regulatory T cells, Sci. Transl. Med (2015). 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad4134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ezzelarab MB, Thomson AW, Adoptive Cell Therapy with Tregs to Improve Transplant Outcomes: the Promise and the Stumbling Blocks, Curr. Transplant. Reports (2016). 10.1007/s40472-016-0114-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fisher SA, Lamikanra A, Dorée C, Gration B, Tsang P, Danby RD, Roberts DJ, Increased regulatory T cell graft content is associated with improved outcome in haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a systematic review, Br. J. Haematol (2017). 10.1111/bjh.14433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wang W, Lau R, Yu D, Zhu W, Korman A, Weber J, PD1 blockade reverses the suppression of melanoma antigen-specific CTL by CD4+CD25Hi regulatory T cells, Int. Immunol (2009). 10.1093/intimm/dxp072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].NCT02691247, Safety and Efficacy of CLBS03 in Adolescents With Recent Onset Type 1 Diabetes (The Sanford Project T-Rex Study), https://Clinicaltrials.Gov/Show/Nct02691247. (2016).

- [29].Chellappa S, Kushekhar K, Munthe LA, Tjønnfjord GE, Aandahl EM, Okkenhaug K, Taskén K, The PI3K 9110δ Isoform Inhibitor Idelalisib Preferentially Inhibits Human Regulatory T Cell Function, J. Immunol (2019). 10.4049/jimmunol.1701703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.