Abstract

The effects of treatment with azithromycin plus rifampin (A+R), amoxicillin (A), or placebo (P) on the chronic course of experimental Chlamydia pneumoniae pneumonitis in mice were assessed by culture, PCR, and immunocytochemistry as well as by degree of inflammation in lung tissue. Eradication of the pathogen was significantly more frequent and inflammation in tissue was significantly reduced after treatment with A+R compared to after treatment with A or P. Combination therapy with azithromycin plus rifampin showed favorable effects in the chronic course of C. pneumoniae pneumonitis.

Chlamydia pneumoniae is frequently the cause of respiratory tract infections (17). A chronic course of lung infection has been occasionally described, and more recently, chronic C. pneumoniae infection has been associated with cardiovascular disease, prompting intervention studies with antimicrobial treatment of patients with unstable angina or recovering from myocardial infarction (1, 10, 11). However, many crucial issues regarding the treatment of C. pneumoniae infection in humans remain unclear. First, little is known about the treatment of acute C. pneumoniae infection (12). Second, established chronic infection is almost impossible to determine in humans by current noninvasive diagnostic techniques. Third, whether and to what extent treatment of acute infection may alter the course of chronic infection is unknown. Fourth, treatment of established chronic infection is problematic, since chlamydiae may survive in a persistent, noncultivable form which may not be amenable to antimicrobial treatment (3). Eradication of C. pneumoniae, which can possibly cause long-term inflammatory sequelae, may thus be of great interest. This may be achieved by different means, e.g., by prolonged treatment with an antimicrobial agent alone, or by a combination of agents during a shorter period of time. We have recently shown in experimental C. pneumoniae pneumonitis that short-term treatment with the in vitro synergistic combination of azithromycin plus rifampin was clearly superior to azithromycin alone or placebo with regard to isolation rates of C. pneumoniae and to detection of pathogen DNA within 3 weeks after infection (22). In clinical practice, however, empirical treatment of longer duration (about 1 week) is recommended for acute pneumonitis. The major goal of this study was to examine the effects of treatment on eradication of C. pneumoniae and on suppression of the inflammatory process in the chronic course of pneumonitis.

C. pneumoniae strain AR-39 was grown in HL cells, partially purified by one cycle each of low- and high-speed centrifugation, resuspended in sucrose-phosphate-glutamic acid buffer, and frozen in 0.5-ml aliquots at −70°C. The inoculum preparation contained 109 inclusion-forming units (IFU) per ml.

Four-week-old male NMRI mice were inoculated by the intranasal route with 5 × 107 IFU/animal of strain AR-39/animal as previously described (18). Antibiotic treatment was started 2 days after inoculation. Groups of 24 animals were killed at different time points after infection, and lungs were removed in toto. One half of the lung was fixed with 4% formal saline and processed into wax blocks, and one half was partly processed for immediate culture and partly frozen at −70°C for DNA detection. Lungs were processed for culture and inclusion counting as previously described (18). DNA from a lung homogenate was isolated in extraction buffer containing 10 mM Tris (pH 8), 100 mM EDTA (pH 8), and 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate and treated with 100 μg of proteinase K per ml. Lysates were extracted with phenol–Tris-HCl–chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. PCR was done with C. pneumoniae-specific HL-1 and HR-1 primer sets, which results in an amplified product of 437 bp (7). Products were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis and confirmed by Southern hybridization as described previously (18). Extraction controls and tissue controls from uninfected animals were run in parallel. All specimens were run in duplicate.

Two days after inoculation, animals were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) either with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (twice a day [b.i.d.] for 7 consecutive days), with the combination of azithromycin dihydrate (10 mg/kg of body weight s.c. once daily for 5 consecutive days) plus rifampin (20 mg/kg s.c. b.i.d. for 7 consecutive days), or with amoxicillin (20 mg/kg s.c. b.i.d. for 7 consecutive days). This dosage of azithromycin produces concentrations similar to those achieved in humans after an oral dose of 500 mg, showing concentrations in pulmonary tissues of mice that were above the MIC for the organism for 48 to 72 h after injection (18). The dosage of rifampin produced concentrations in small rodents similar to those achieved in humans after an oral dose of 450 mg, providing concentrations in lung tissue that were above the MIC for 6 to 15 h after injection (9). The dosage of amoxicillin was based upon prior studies of mice with experimental C. trachomatis pneumonitis (2, 15). The dosage regimen of amoxicillin used in this study (b.i.d.) does not simulate the pharmacokinetics seen in humans.

Lung sections cut at a nominal microtome setting of 3 μm and stained with hematoxylin-eosin were used for assessment of inflammation. Nodular mononuclear infiltrates, a striking pathologic feature of chronic C. pneumoniae pneumonitis observed previously (23), were identified in a semiquantitative fashion by counting all visible foci in one section from the entire embedded half lung. The numbers obtained were normalized to the area (1 cm2) of one section. The numbers of presumed diffuse infiltrates of inflammatory cells were determined by counting all nuclei in eight randomly chosen high-power fields (magnification, ×1,000) of alveolar parenchyma devoid of nodular infiltrates, and the results were averaged.

For immunocytochemical staining, 3-μm Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of mouse lung tissue were dewaxed, rehydrated, and boiled in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a pressure cooker for 5 min. Sections were then (and following all subsequent steps) washed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). A mix of a Chlamydia genus-specific antibody (clone CF-2) and a biotinylated rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) was prepared and incubated for 30 min on a shaker at room temperature to allow complex formation. The concentration of CF-2 was approximately 2 μg/ml (1:500), while the secondary antibody was used at a dilution of 1:600, corresponding to a 1.9-μg/ml concentration of specific IgGs. Antibodies were diluted in TBS containing 5% rabbit serum (Life Technologies, Paisley, Scotland) and 0.5% casein sodium salt (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Slides were incubated with this complex of primary and secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. Controls were either incubated with a mixture in which clone CF-2 was replaced with the same concentration of an irrelevant mouse monoclonal antibody against Aspergillus niger glucose oxidase (clone DAK-GO5; Dako) or with the secondary antibody alone. Slides were incubated with avidin-biotin–alkaline phosphatase (1:200 in TBS). Finally, sections were developed in a new fuchsin-naphtol AS-BI substrate (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), counterstained with haematoxylin, cleared, and mounted. The proportion of animals for whom C. pneumoniae infection was eradicated in the course of pneumonitis among the three treatment groups was analyzed by chi-square test. The degrees of inflammation in tissue as assessed by the total number of mononuclear cells and the number of accumulations of mononuclear cells were analyzed by Mann-Whitney test.

Ten days after infection, C. pneumoniae was isolated from the lungs of all control (PBS) animals, from the lungs of some animals after amoxicillin treatment but not from the lungs of animals after treatment with azithromycin plus rifampin (Table 1). After 30 and 60 days, all lungs in all treatment groups were culture negative. C. pneumoniae AR-39 DNA was studied in culture-negative lung tissues. In controls and in animals treated with amoxicillin, DNA was consistently detected at all time points. The detection rate of pathogen DNA over time clearly declined after treatment with azithromycin plus rifampin. Immunocytochemical staining showed that antigen was detected consistently in the control group and frequently in the group treated with amoxicillin, but that antigen detection rates declined after treatment with azithromycin plus rifampin. Eradication was defined as no detection of C. pneumoniae in lung tissues as assessed by culture, PCR, and immunocytochemistry (ICC) (Table 1). Eradication rates increased with time from infection, being lowest after 10 days and highest after 60 days of infection. When data from all three time points were considered, C. pneumoniae was eradicated from only 2 of 23 lungs of control animals and 4 of 24 lungs of animals treated with amoxicillin, but from 11 of 24 lungs of animals treated with azithromycin plus rifampin (P = 0.007).

TABLE 1.

Infection with C. pneumoniae and eradication of infection

| Day of sacrifice and treatment group | No. of samples in which infection was detected/no. tested by:

|

No. of samples in which infection was eradicated/no. testeda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture | PCR | ICC | ||

| 10 | ||||

| PBS | 8/8 | NDb | 7/8 | 0/8 |

| Amoxicillin | 3/8 | 4/5 | 7/8 | 0/8 |

| Azithromycin + rifampin | 0/8 | 6/8 | 7/8 | 1/8 |

| 30 | ||||

| PBS | 0/7 | 4/7 | 7/7 | 0/7 |

| Amoxicillin | 0/8 | 6/8 | 5/8 | 2/8 |

| Azithromycin + rifampin | 0/8 | 2/8 | 2/8 | 5/8 |

| 60 | ||||

| PBS | ND | 6/8 | 3/8 | 2/8 |

| Amoxicillin | ND | 6/8 | 0/8 | 2/8 |

| Azithromycin + rifampin | ND | 3/8 | 3/8 | 5/8 |

Eradication was defined as the absence of C. pneumoniae from lung tissue as assessed by culture, PCR, and ICC. P = 0.007 for comparison between treatment groups for all time points.

ND, not done.

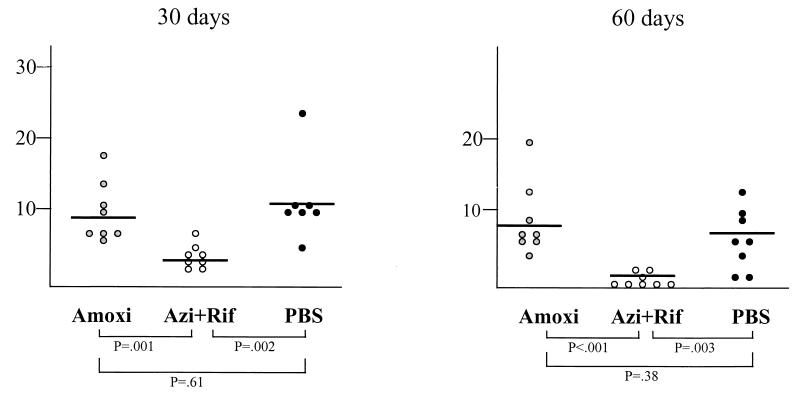

The number of mononuclear cell infiltrates decreased with time in all three treatment groups (data not shown). The number of mononuclear cells was not significantly different in the control and amoxicillin groups at all three time points. In contrast, the number mononuclear cell infiltrates was significantly reduced in animals treated with azithromycin plus rifampin compared with the number in either controls (P < 0.03) or amoxicillin-treated animals (P < 0.003) at all three time points. Nodular accumulations of mononuclear cells were observed only 30 and 60 days after infection in all treatment groups (Fig. 1). Their numbers declined from day 30 to day 60 in all but the amoxicillin-treated group. The number of lesions was not significantly different at both time points in controls and in animals treated with amoxicillin. In contrast, there were significantly lower accumulations of mononuclear cells after treatment with azithromycin plus rifampin compared to after treatment with PBS (controls) or amoxicillin.

FIG. 1.

Number of nodular mononuclear infiltrates in sections of lung tissue 30 and 60 days after infection. Each dot represents data from one animal. Three treatment regimens were studied, as follows: amoxicillin (Amoxi) (20 mg/kg s.c. b.i.d. for 7 days), azithromycin (10 mg/kg s.c. daily for 5 days) plus rifampin (20 mg/kg s.c. bid for 7 days) (Azi + Rif), and PBS (b.i.d. for 7 days). Statistical comparisons were done by Mann-Whitney test.

In this study, we induced C. pneumoniae pneumonitis in mice and observed a chronic course for 2 months after infection. Experimental studies addressing treatment issues in C. pneumoniae pneumonitis have focused on the acute course of pneumonitis, either in immunosuppressed or immunocompetent mice (18, 20, 21). We have previously shown that short-term treatment of C. pneumoniae pneumonitis in immunocompetent mice suppressed chlamydial replication (18). However, the inflammatory process in lung parenchyma appeared not to be affected by antimicrobial treatment, and C. pneumoniae DNA could frequently be found in culture-negative lungs within 2 weeks after treatment. Reactivation experiments with cortisone acetate strongly suggested that C. pneumoniae DNA was representative of noncultivable but viable organisms (19). Most recently, we have performed in vitro susceptibility tests showing a synergistic activity of azithromycin plus rifampin, and this treatment regimen led to a higher rate of eradication of the organism from lung tissue than did treatment with azithromycin alone within 3 weeks after infection (22). Since C. pneumoniae can cause chronic inflammation in lung tissue, it was important to investigate treatment effects on the chronic course of pneumonitis. Our results show that combined treatment with azithromycin plus rifampin was clearly superior to no treatment or treatment with amoxicillin alone for eradication of C. pneumoniae. This higher eradication rate of the pathogen was accompanied by suppression of the inflammatory process in lung tissue.

Amoxicillin is not a treatment of choice for chlamydial infection. However, in vitro experiments have shown that ampicillin and amoxicillin each have a definite, but incomplete, inhibitory effect on C. trachomatis and C. pneumoniae at concentrations attainable in vivo (4, 5, 8, 15, 16). Masson et al. (20) have shown some activity of amoxicillin-clavulanate in reducing isolation rates of C. pneumoniae from lungs in experimental mouse pneumonitis 1 day after cessation of treatment. Based upon these observations, one cannot dismiss that amoxicillin might eventually induce more chlamydial persistence with long-term sequelae. Finally, aminopenicillins are frequently used for the empirical treatment of community-acquired pneumonia, and C. pneumoniae may account for 6 to 12% of these cases, leaving the long-term effects of such treatment unclear. In our study, amoxicillin was not statistically different from the placebo with regard to eradication of the organism and suppression of the inflammatory process. The mechanisms by which azithromycin combined with rifampin favored eradication early as well as late in the course of pneumonitis and suppressed chronic inflammation were not investigated. Rifampin has excellent antichlamydial activity in vitro (13, 22), but rapid emergence of chlamydial resistance in vitro after exposure to the drug alone has been described (14). A hypothetical mechanism by which the addition of rifampin may be responsible for the favorable effects in combination was provided recently by the observation that rifampin is a glucocorticoid receptor ligand with the ability to transactivate the receptor (6). Following this hypothesis, rifampin could act as an immunosuppressive agent, reactivating persistent infection and thus allowing azithromycin to act on replicating pathogens, eventually suppressing the chronic inflammatory process. Strategies to eradicate C. pneumoniae from tissue should be further investigated.

Acknowledgments

Grant support was received from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 3200-04066.94).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson J L, Muhlestein J B, Carlquist J, Allen A, Trehan S, Nielson C, Hall S, Brady J, Egger M, Horne B, Lim T. Randomized secondary prevention trial of azithromycin in patients with coronary artery disease and serological evidence for Chlamydia pneumoniae infection. Circulation. 1999;99:1540–1547. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.12.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beale A S, Faulds E, Hurn S E, Tyler J, Slocombe B. Comparative activities of amoxycillin, amoxycillin/clavulanic acid and tetracycline against Chlamydia trachomatis in cell culture and in an experimental mouse pneumonitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991;27:627–638. doi: 10.1093/jac/27.5.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beatty W L, Morrison R P, Byrne G I. Persistent chlamydiae: from cell culture to a paradigm of chlamydial pathogenesis. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:686–699. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.4.686-699.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowie W R, Lee C K, Alexander E R. Prediction of efficacy of antimicrobial agents in treatment of infections due to Chlamydia trachomatis. J Infect Dis. 1978;138:655–659. doi: 10.1093/infdis/138.5.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowie W R. In vitro activity of clavulanic acid, amoxicillin, and ticarcillin against Chlamydia trachomatis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;29:713–715. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.4.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calleja C, Pascussi J M, Mani J C, Maurel P, Vilarem M J. The antibiotic rifampicin is a nonsteroidal ligand and activator of the human glucocorticoid receptor. Nat Med. 1998;4:92–96. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell L A, Perez Melgosa M, Hamilton D J, Kuo C-C, Grayston J T. Detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:434–439. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.2.434-439.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehret J M, Judson F N. Susceptibility testing of Chlamydia trachomatis: from eggs to monoclonal antibodies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1295–1299. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.9.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furesz S. Chemical and biological properties of rifampicin. Antibiot Chemother. 1970;16:316–351. doi: 10.1159/000386837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta S, Leatham E W, Carrington D, Mendall M A, Kaski J C, Camm A J. Elevated Chlamydia pneumoniae antibodies, cardiovascular events, and azithromycin in male survivors of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1997;96:404–407. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.2.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurfinkel E, Bozovich G, Daroca A, Beck E, Mautner B. Randomized trial of roxithromycin in non-Q-wave coronary syndromes: ROXIS pilot study. Lancet. 1997;350:404–407. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammerschlag M R. Antimicrobial susceptibility and therapy of infections caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1873–1878. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones R B, Ridgway G L, Boulding S, Hunley K L. In vitro activity of rifamycins alone and in combination with other antibiotics against Chlamydia trachomatis. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5(Suppl. 3):556–561. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.supplement_3.s556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keshishyan H, Hanna L, Jawetz E. Emergence of rifampin-resistance in Chlamydia trachomatis. Nature. 1973;244:173–174. doi: 10.1038/244173a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kramer M J, Cleeland R, Grunberg E. Activity of oral amoxicillin, ampicillin, and oxytetracycline against infection with Chlamydia trachomatis in mice. J Infect Dis. 1979;139:717–719. doi: 10.1093/infdis/139.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuo C C, Grayston J T. In vitro drug susceptibility of Chlamydia sp. strain TWAR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:257–258. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.2.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuo C C, Jackson L A, Campbell L A, Grayston J T. Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR) Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:451–461. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malinverni R, Kuo C C, Campbell L A, Lee A, Grayston J T. Effects of two antibiotic regimens on the course and persistence of experimental Chlamydia pneumoniae TWAR pneumonitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:45–49. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malinverni R, Kuo C C, Campbell L A, Grayston J T. Reactivation of Chlamydia pneumoniae lung infection in mice by cortisone. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:593–594. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.2.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masson N, Nigel Toseland C D, Beale A S. Relevance of Chlamydia pneumoniae murine pneumonitis model to evaluation of antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1959–1964. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.9.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakata K, Okazaki Y, Hattori H, Nakamura S. Protective effects of sparfloxacin in experimental pneumonia caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae in leukopenic mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1757–1762. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.8.1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf K, Malinverni R. Effect of azithromycin plus rifampin versus that of azithromycin alone on the eradication of Chlamydia pneumoniae from lung tissue in experimental pneumonitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1491–1493. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Z P, Kuo C C, Grayston J T. A mouse model of Chlamydia pneumoniae strain TWAR pneumonitis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2037–2040. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2037-2040.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]